1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, green municipal bonds have experienced remarkable growth, emerging as a pivotal instrument for financing green and climate-related projects and infrastructure. By 2020, the green bond market had expanded to approximately

$1 trillion. Despite this growth, GMBs

1 represent only a small fraction of the overall finance market, primarily due to their appeal among green- aligned investors.

Current green bond issuances indicate that while GMBs are gaining traction among green-focused investors, they often come with higher costs compared to traditional municipal bonds. Although the interest rates may be similar, GMBs typically incur increased costs due to additional certification requirements and the need for comprehensive reporting standards. These bonds are evaluated based on their use of proceeds and adherence to environmental standards set by organizations like the CBI

2, which align with the Paris Climate Agreement goals.

This situation highlights a significant research gap: the need to understand the balance between the benefits of GMBs and their financial implications compared to traditional bonds. Specifically, there is a need to assess how the higher costs associated with green bonds impact their long-term viability and effectiveness in promoting sustainable development, as well as how SNGs

3 can optimize their financing strategies for green projects.

Addressing this gap is crucial for informing SNGs’ financing decisions. By exploring the cost-benefit dynamics of green municipal bonds and their role in achieving sustainable growth goals, this study aims to provide insights that will assist SNGs in navigating the complexities of green finance. The objectives of this research are to evaluate the financial and environmental performance of GMBs, understand their impact on sustainable growth, and offer recommendations for aligning green financing strategies with long-term economic development and environmental goals.

2. Sources of Capital for SNGs

Before delving into municipal bonds, it's essential to explore the array of the sources of capital that SNGs rely on to fund their development initiatives, each offering unique benefits and challenges.

2.1. Public Sources of Funding

Several national and international public sources are potentially available for SNGs to finance their climate action projects and they include:

2.1.1. SNG’s Own Resources

For most SNGs, budgets are the primary source of finance for climate action, funded through intergovernmental transfers, subsidies, tax revenues, user fees, and property income. SNG

4 budgets vary but typically account for about 9% of GDP and 23.9% of public spending on average.

An effective approach is ‘climate smart’ budgeting, integrating climate action into broader SNG activities. Despite its complexity and the need for cross-departmental collaboration, only a few cities like Kampala (Uganda), Arusha and Dar es Salaam (Tanzania), Durban/eThekwini (South Africa), Mumbai (India), and Rio de Janeiro have attempted it.

As tools and techniques for climate smart budgeting become more available and affordable, more SNGs are likely to adopt this approach. However, SNGs in developing countries often lack the capacity or financial resources, making implementation challenging.

2.1.2. National Government Transfer

In most developing countries, national government funding comprises over 50% of revenue for SNGs. Since 2008, with World Bank support, the Government of Ethiopia has been using performance-based fiscal transfers to 117 SNGs to improve institutional performance and achieve climate and sustainable urban development objectives. This program incentivizes SNGs to enhance their capacity and efforts in these areas in exchange for additional funds and resources. A similar program in Kenya, supporting the Kenya Devolution Support Program, is co-funded by the Kenyan Government and the World Bank.

2.1.3. DFIs

A Development Finance Institution (DFI) is a specialized financial organization set up to develop the private sector. They are often owned and funded by national and international governments. DFIs are increasingly supporting SNGs in developing countries by providing concessional loans, credit enhancements, and assistance in structuring investments, with a growing focus on climate-smart and sustainable infrastructure.

In 2023, the UK's DFI, British International Investment (BII), invested 20 million EUR in The Urban Resilience Fund (TURF) in partnership with the private sector infrastructure investor Meridiam for decarbonization projects in SNGs in sub-Saharan Africa.

DFIs

5 play a critical role in financing climate action initiatives for SNGs, focusing primarily on private sector development as a catalyst for economic development and sustainability. While DFIs do seek projects with commercial viability, their investment criteria extend beyond financial returns, aiming for broader developmental impacts, such as social, environmental, and economic benefits. They often channel their support to projects associated with SNGs rather than directly funding the SNGs, to ensure effective utilization of funds and achievement of developmental outcomes.

However, SNG projects frequently face challenges in attracting DFI financing due to issues like underdevelopment and lack of investment readiness, which can overshadow their potential to meet stringent investment criteria. Despite these challenges, DFIs invest in projects that may not yield direct commercial returns but are essential for economic development, such as infrastructure projects critical for private sector growth. This approach underscores the DFIs’ commitment to balancing financial viability with broader developmental goals, effectively contributing to climate action and sustainable growth initiatives.

2.1.4. Aid Agencies

Aid agencies, such as the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), play a role in supporting SNGs through technical assistance, capital facilitation (grants and other viability gap funding), and credit guarantees. These agencies primarily offer technical support to SNGs, helping them build capacity and improve project readiness. In certain cases, aid agencies also make investments in projects that align with their goals or mandate.

Aid agencies typically require detailed project proposals and may prioritize projects based on their alignment with the agency’s objectives. While the support from aid agencies is valuable, it often comes with conditions and requirements that SNGs must meet. This can include demonstrating the project’s potential impact, sustainability, and alignment with broader development goals. The availability of funds and the specific criteria for support can vary, making it essential for SNGs to carefully navigate the application process.

2.2. Private Sources of Funding

In addition, SNGs also have access to private sources to meet their investment needs, fostering economic development. These sources include:

2.2.1. Commercial Banks

Commercial banks continue to be major investors in SNGs, particularly in infrastructure, and have access to considerable capital, with an increasing focus on sustainable development

For many SNGs, commercial banks are the first-choice option for securing loans and investments. However, commercial banks are driven by business considerations, so their willingness to lend depends on several factors:

The SNG's creditworthiness and track record of managing and repaying loans.

The commercial viability of the project, including its risk profile and return on investment.

The SNG's ability to take on additional debt.

Adequate financial management of the SNG, including budgeting, financial controls, and reporting mechanisms.

2.2.2. Institutional Investors

An institutional investor is an entity that invests funds on behalf of others, seeking long-term investments with minimal risk and stable returns. Examples include pension funds, insurance companies, and mutual funds. Municipal bonds are a common method for SNGs to secure financing from institutional investors for their projects due to their long tenor, stable returns, and minimal risk profile. While the largest municipal bond markets are currently in the USA, China, and Japan, municipal bonds are becoming increasingly utilized in developing countries.

Notable examples of municipal bonds include:

Mexico City Green Bond issued for $50 million in 2016

In India, from 2016-2017 to 2020-2021, nine municipal bodies raised 38.4 billion rupees through bonds.

Institutional investors tend to finance projects directly, with public entities (such as DFIs or government agencies) stepping in to ‘de-risk’ the projects to a suitable level. As a result, they do not tend to finance SNGs directly, except through bonds.

SNGs will require:

Suitable investment projects with low-risk profiles and stable anticipated returns.

An investment-grade credit rating.

However, many SNGs are forbidden from issuing debt by their central governments due to the risk of default and in many cases do not have the capacity or creditworthiness to do so anyway.

2.2.3. Corporate Buyers

Many companies worldwide are increasingly purchasing carbon credits to fulfil their corporate climate targets and commitments through global carbon markets, estimated at 865 billion EURs in 2022.

6 Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) in Vietnam has initiated a pilot Carbon Credit Exchange & Clearing House to sell carbon credits generated from local projects like rooftop solar in domestic and international markets. The revenue generated is intended to fund additional climate-related initiatives. Carbon credits can serve as a valuable revenue source for SNGs, but projects must be sufficiently large or pooled to cover transaction costs.

The revenue generated from selling these credits on voluntary carbon markets (VCMs) can offset investment costs for projects such as urban reforestation or rooftop solar, making these initiatives more economically viable. However, carbon credits have drawn criticism for potentially allowing affluent entities to continue emissions by offsetting rather than transitioning to sustainable practices, which could undermine emission reduction goals.

2.2.4. Private Companies

Private companies play a significant role in financing projects for SNGs through mechanisms such as project finance and balance sheet financing. Although these companies may not have the licensing to provide loans directly, they can partner with SNGs on various projects. This collaboration often takes the form of PPPs

7 and contributions through CSR

8 initiatives. Such partnerships and initiatives support the financial and developmental needs of SNGs, providing essential resources and expertise. The risk appetite of private companies in these ventures typically ranges from low to medium, depending on the project’s nature and potential returns.

2.2.5. Households

In addition, households/citizens also contribute to the financing landscape through direct investments, such as consumer loans, and crowd-based financing. This type of financing is particularly relevant for smaller projects, typically requiring funding between $1-3 million. While households and citizens may not have the capacity to raise funds for larger projects, their contributions can be significant for smaller-scale initiatives. The risk appetite in this context can vary widely, ranging from low to high, depending on the specific circumstances and the perceived risks and benefits of the investment.

3. Sources of Funding in Developed Countries

In developed countries, a range of financial institutions play vital roles in financing sustainable growth initiatives, leveraging a combination of public and private funding sources and they include:

3.1. United States

3.1.1. Green Banks

Green banks are public or quasi-public financial institutions dedicated to financing clean energy and sustainable projects. They provide low-cost financing, incentives, and technical assistance to accelerate the adoption of renewable energy, energy efficiency improvements, and green infrastructure.

9

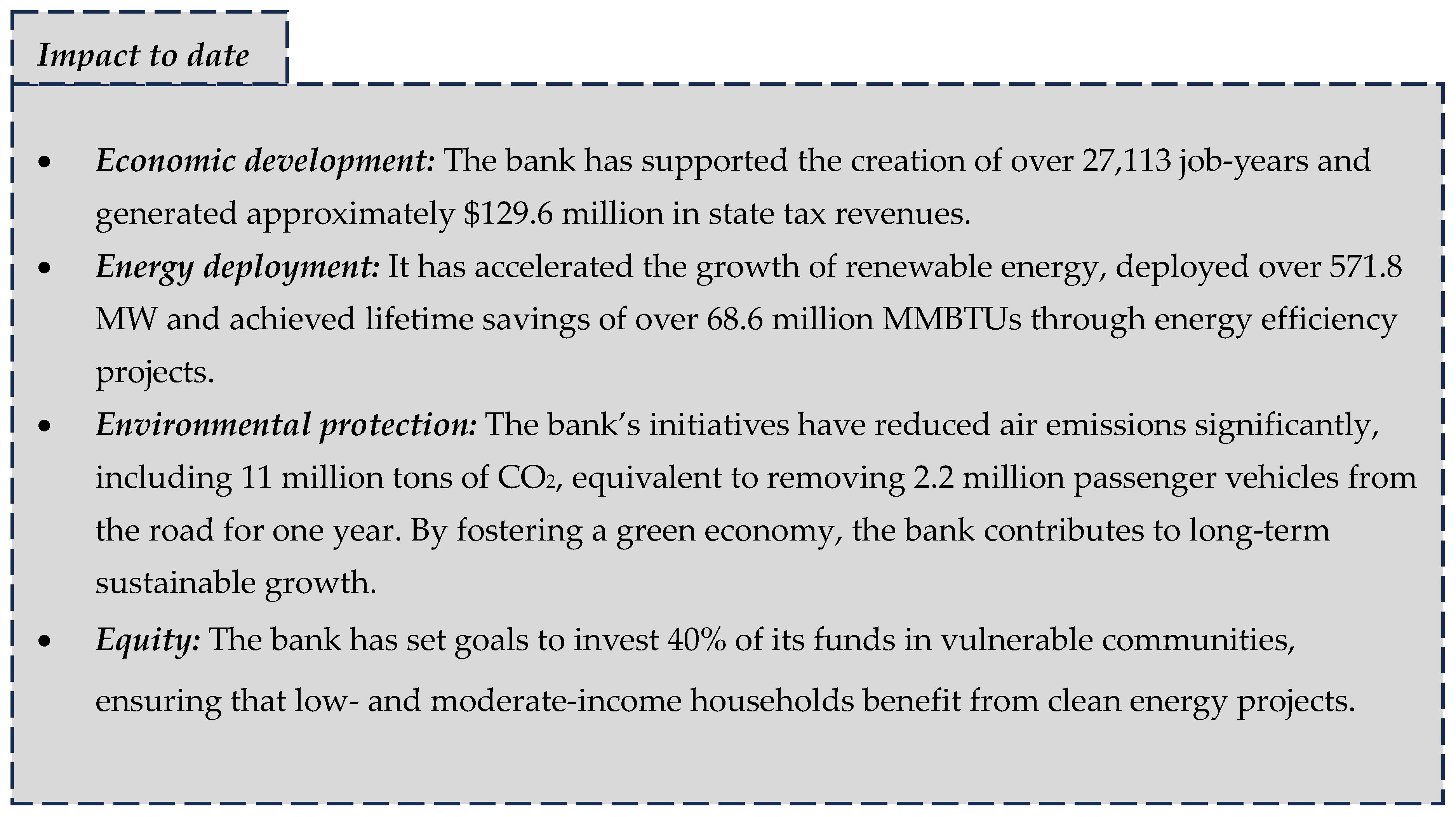

3.1.1.1. Connecticut Green Bank

The Connecticut Green Bank, established in 2011, is the first green bank in the United States. It was capitalized through a combination of public funds and private investments. Initially, the bank leveraged $362.7 million in public funds to attract $2.06 billion in private investment, achieving a leverage ratio of $6.70 for every $1 of public funds.

Notably, Connecticut Green Bank financed the Solar for All program, which aims to make solar energy accessible to low- and moderate-income households.

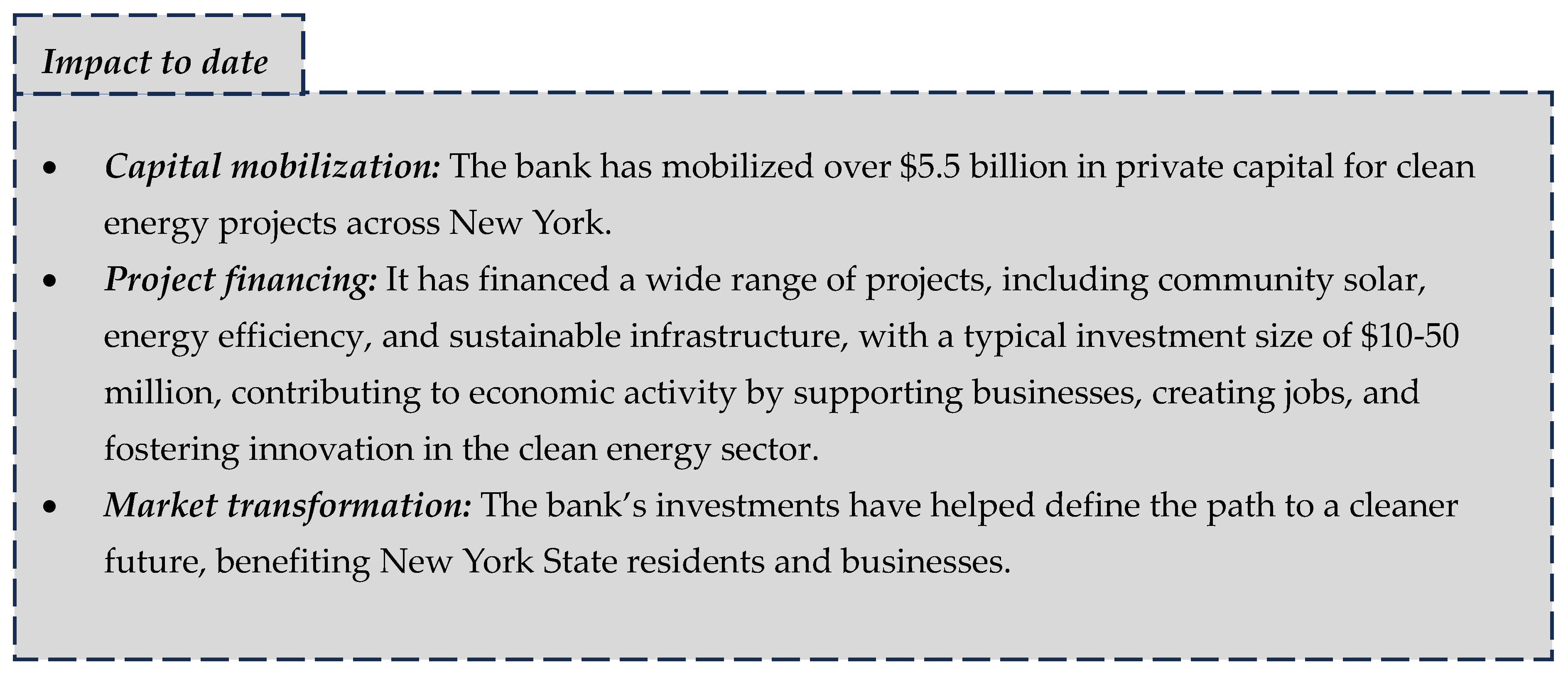

3.1.1.2. New York Green Bank

The New York Green Bank, launched in 2014, was initially capitalized with $1 billion from the state of New York. It has since reinvested its initial capitalization to result in over $2 billion of capital commitments.

The New York Green Bank provided funding for the Community Solar NY initiative, which supports the development of community solar projects across the state.

The bank has placed a strong emphasis on ensuring that all New Yorkers, including those in historically marginalized communities, benefit from the clean energy transition. This focus on inclusivity not only addresses social and economic disparities but also supports sustainable growth by enhancing community resilience and engagement in the green economy.

3.2. United Kingdom

3.2.1. Public Works Loan Board (PWLB)

The PWLB provides low-cost loans to UK local authorities and certain other bodies for capital projects, including infrastructure and green initiatives.

10

The PWLB provided funding for the Greater Manchester Combined Authority to invest in energy efficiency projects across public buildings, reducing carbon emissions and energy costs.

3.2.2. London Green Finance Fund (LGFF)

The London Green Fund was launched in the summer of 2023 during London Climate Action Week. It aims to support London Councils and anchor institutions in financing their climate projects by making £500 million available. The fund offers concessional financing, which is cheaper than the Public Works Loan Board (PWLB) rates, achieved by using the Greater London Authority’s (GLA) balance sheet funding to subsidise PWLB funding. In its initial phase, the LGFF

11 is fully capitalised using public funding from the GLA

12 balance sheet and PWLB

13. However, as the fund demonstrates proof of concept, there is an ambition to attract private investment in later stages, potentially unlocking several billions of pounds for investment into local climate solutions.

The LGFF provides loans with flexible terms at interest rates agreed on a project-by-project basis, at or below PWLB prevailing rates. Eligible organisations include the GLA Group, local authorities, social housing providers, NHS bodies, universities, colleges, and accredited museums. Projects must deliver benefits in energy efficiency, clean transportation, or renewable energy and meet specific carbon savings and climate impact criteria. This fund is part of a broader strategy to mobilize both public and private capital to achieve London’s ambitious net-zero targets by 2030. The LGFF is designed to accelerate decarbonisation by lowering the cost of borrowing for eligible organisations, thereby making it easier for them to invest in sustainable growth initiatives/infrastructure.

This strategy is expected to play a crucial role in addressing the triple challenges of toxic air pollution, climate change, and congestion, enhancing London’s economic resilience. Additionally, the LGFF is complemented by other programs such as the Mayor’s Energy Efficiency Fund (MEEF) and the Retrofit Accelerator, which provide technical support and additional funding for energy efficiency projects. It also aims to build on London’s existing financing capabilities to secure investment and strengthen its competitiveness as a global leader in green finance.

3.2.3. UK Infrastructure Bank (UKIB)

The UK Infrastructure Bank is a government-backed institution established in June 2021. Its primary mission is to support infrastructure projects across the UK, with a strong emphasis on tackling climate change and promoting economic development in regional and local sectors. Owned by HM Treasury but operating independently, UKIB aims to help the UK achieve its net-zero carbon emissions target by 2050.

It provides financing to both the private sector and local governments for various infrastructure initiatives, including renewable energy projects like the development of offshore wind farms. UKIB has £4 billion available for local authority lending. This funding is intended to support local governments in implementing sustainable and climate-resilient infrastructure projects.

14 Notably, it has funded the Tees Valley Combined Authority with funding for renewable energy projects, including the development of offshore wind farms.

4. Financial Instruments

The public and private funders, discussed above offer investments through various financial instruments, such as:

4.1. CONCESSIONARY loans

Concessional finance, provided by institutions like development banks and multilateral funds, offers below-market rate loans to developing countries to support economic development goals. While typically available to sovereign governments, some SNGs are now also eligible.

The primary benefit of concessional loans is their affordability, enabled by public funding from Development Finance Institutions (DFIs). Although concessional loans alone do not attract private investment, blended finance facilities that use public funding to reduce the cost of private finance can.

Concessional finance is increasingly being used to drive climate action at the sub-national level, but there are often barriers to SNGs accessing it:

Need for fiscal autonomy and strong financial management systems.

Permission and guarantee provided by sovereign government.

Eligibility and restrictions set by provider e.g. creditworthiness of borrower.

The fiscal capacity of the SNG, whether it has reached its debt ceiling, which can limit its ability to take on additional debt.

4.2. Market Rate Loans

Market rate loans, provided by the private sector, are crucial for financing climate projects with clear financial returns, such as renewable energy and building retrofits. Though more expensive than concessional loans, they are more readily available, with commercial lenders increasingly interested in climate-focused investments due to rising investor commitments to climate goals.

Many SNGs struggle to attract private finance due to inadequate risk-reward profiles and creditworthiness.

Market rate loans are pivotal for climate finance, especially for larger, creditworthy SNGs, especially in developed countries, frequently use these loans, but smaller SNGs in developing countries face barriers such as:

Lack of creditworthiness, fiscal autonomy, and fiscal capacity.

Need for sovereign debt guarantees.

Requirement for revenue-generating projects to service debt.

Risk of default due to underdeveloped projects and other factors, such as lack of political championing, corruption, etc.

Insufficiently large ticket sizes, due to small projects, which are unattractive to investors.

4.3. Carbon Credit

Carbon credits are generated by certified mitigation projects like renewable energy or tree planting, which can be sold in international carbon markets. These credits can offset project costs and provide future revenue streams, though upfront investment is required. By providing a steady revenue stream for decarbonization projects, carbon credits not only help to offset their costs but also contribute to economic development by fostering innovation, and attracting investment in sustainable infrastructure. However, they require large enough projects to offset transaction costs, certified third-party monitoring and verification, and upfront investment.

In 2021, compliance carbon markets reached

$850 billion, and voluntary markets

$2 billion, with rapid growth expected. These markets could be a significant revenue source for local governments developing credit-generating projects.

15

5. Municipal Bonds

Over the years, various SNGs across the world have issued bonds to finance key projects, particularly infrastructure, with investors benefiting from stable yields and limited risk.

As discussed earlier, SNGs require some constitutional authority or legal authorization to issue such bonds, and therefore must fulfil these requirements, as failure to do so could render the issuance invalid.

Figure 1.

Municipal bond issuance and utilization process.

Figure 1.

Municipal bond issuance and utilization process.

5.1. Constitutional Issues

Constitutional issues influencing SNG’s issuance of municipal bonds include:

Table 1.

Legal framework governing SNG bond issuance.

Table 1.

Legal framework governing SNG bond issuance.

| Legal authority |

SNGs derive their power to issue bonds from laws and statutes, which must be strictly followed to ensure the bonds’ legality. This authority is often outlined in state constitutions or legislative acts, providing a clear mandate for bond issuance and the specific purposes for which these funds can be raised |

| Adherence to debt limits |

Constitutional debt limits are set to prevent excessive borrowing that could jeopardize the financial stability of the SNG. Bonds issued in contravention of these limits face legal challenges and may be deemed invalid, leading to disputes that can undermine the credibility of the SNG and its future endeavours to raise capital |

| Ultra vires doctrine |

The principle of ‘ultra vires’ acts as a safeguard against SNGs exceeding their authority. If bonds are issued beyond the scope of the legal power granted to the SNG, they can be declared void. This doctrine emphasizes the importance of operating within the legal confines to maintain the enforceability of bond obligations |

5.2. Case Study: Dakar’s Municipal Bond Issue

While SNGs globally utilize bond issuances for financing, Dakar’s case presents a unique set of challenges and learnings. Dakar aimed to issue a $40 million bond to fund infrastructure for informal traders, marking a significant step for urban development in Senegal. This bond was set to be the first in the WAEMU region, potentially setting a precedent for municipal financing in West Africa.

Dakar received technical assistance from international partners, including the World Bank’s PPIAF

16/SNTA

17 program, to strengthen its fiscal management and creditworthiness. The initiative was part of a broader strategy to enhance Dakar’s financial autonomy and reduce reliance on central government transfers. Despite meeting the technical requirements and improving fiscal management, the bond issuance was abruptly halted by the central government, citing debt sustainability concerns. The Dakar municipal bond case brought to light the intricate balance between local governance initiatives and national fiscal oversight, challenging the autonomy of city authorities in the face of central government intervention.

5.2.1. Key Insights from Dakar’s Bond Issuance

Legal frameworks for fiscal decentralization: The Dakar case highlights the imperative for clear legal frameworks that empower local governments to finance their initiatives autonomously. Well-defined laws must facilitate local borrowing while ensuring alignment with national fiscal policies to prevent conflicts and ensure smooth bond issuance processes.

Financial management and transparency: This includes clear accounting, consistent reporting practices, and a solid plan for revenue generation. Demonstrating creditworthiness is a key aspect of financial transparency, as it assures investors of the city’s ability to manage debt and fulfil financial obligations.

Market confidence: Cultivating market confidence validates a city’s track record of fiscal responsibility and viable project planning. This helps in attracting investment and securing favourable terms for municipal bonds.

Inter-governmental collaboration: It is important to foster collaboration between local and central governments. Establishing a cooperative approach can facilitate the understanding and support needed for municipal bond initiatives, ensuring that local development goals are not hindered by national-level constraints.

6. Green Municipal Bonds (GMBs)

Alternatively, SNGs can issue GMBs, which are a specialized subset of munis

18 that finance projects which promote environmental sustainability. These projects may include renewable energy installations, pollution control measures, and sustainable water management systems, all of which play a critical role in advancing economic sustainability and development.

Over the past two decades, there has been a huge growth in the development of green bonds

19, specifically aimed at financing green/climate-related projects and infrastructure, with the market growing to

$1 trillion in size in 2020. This growth reflects a growing recognition of the importance of integrating environmental considerations into financial decision-making and highlights the increasing demand for investments that support sustainable development goals.

6.1. Comparative Analysis Between Traditional Municipal Bonds and GMBs

As opposed to traditional municipal bonds, GMBs finance eco-friendly projects with added transparency and impact reporting.

However, across different attributes, they share much in common, as seen in the table below:

Table 2.

Comparison of vanilla and Green Municipal Bonds.

Table 2.

Comparison of vanilla and Green Municipal Bonds.

| Attribute |

Vanilla municipal bonds |

Green municipal bonds |

| Purpose |

Finances a broad spectrum of municipal projects, including some with environmental benefits |

Exclusively earmarked for projects with environmental benefits, like renewable energy or efficient waste management |

| Investor base |

Attracts a diverse range of investors, including institutional and individual bondholders |

Draws a similar investor base, with a notable appeal to those prioritizing environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria |

| Risk |

Credit risk is tied to the financial health of the issuing SNG |

Shares a similar credit risk profile, with additional scrutiny related to ESG risk. The risk profile, however, is not inherently higher or lower than traditional municipal bonds |

| Return profile |

Offers returns based on market conditions and the issuer’s creditworthiness |

May offer slightly lower yields, reflecting premium investors are willing to pay for contributing to environmental sustainability |

| Certification & standards |

Standard municipal bonds without specific environmental certifications |

Often come with green certifications, ensuring the funds are utilized for qualifying environmental projects |

| Tax treatment |

Generally, enjoy tax-exempt status, making them attractive to tax-sensitive investors |

Typically share the same tax benefits, aligning with the tax treatment of traditional municipal bonds |

| Bond structure |

Can be general obligation or revenue bonds, with terms and repayment structured according to the project’s needs and the issuer’s capabilities |

Structured similarly to vanilla bonds, but with the stipulation that funded projects must meet environmental criteria, which may influence terms and repayment options |

6.2. Eligibility on GMBs

Eligibility is determined by their use of proceeds, reporting standards, and impact measurement:

Table 3.

Key requirements for GMBs.

Table 3.

Key requirements for GMBs.

| Use of proceeds |

The funds raised by green municipal bonds must be allocated to projects with clear environmental benefits, such as renewable energy, pollution prevention, sustainable water management, and climate change adaptation |

| Reporting standards |

Issuers of green municipal bonds are required to adhere to internationally recognized reporting standards, such as the Green Bond Principles (GBP), which promote transparency and disclosure of how the bond proceeds are used |

| Impact measurement |

The impact of the financed projects must be measured and reported to demonstrate the environmental benefits achieved. This often involves quantifying outcomes such as reduced carbon emissions or improved energy efficiency |

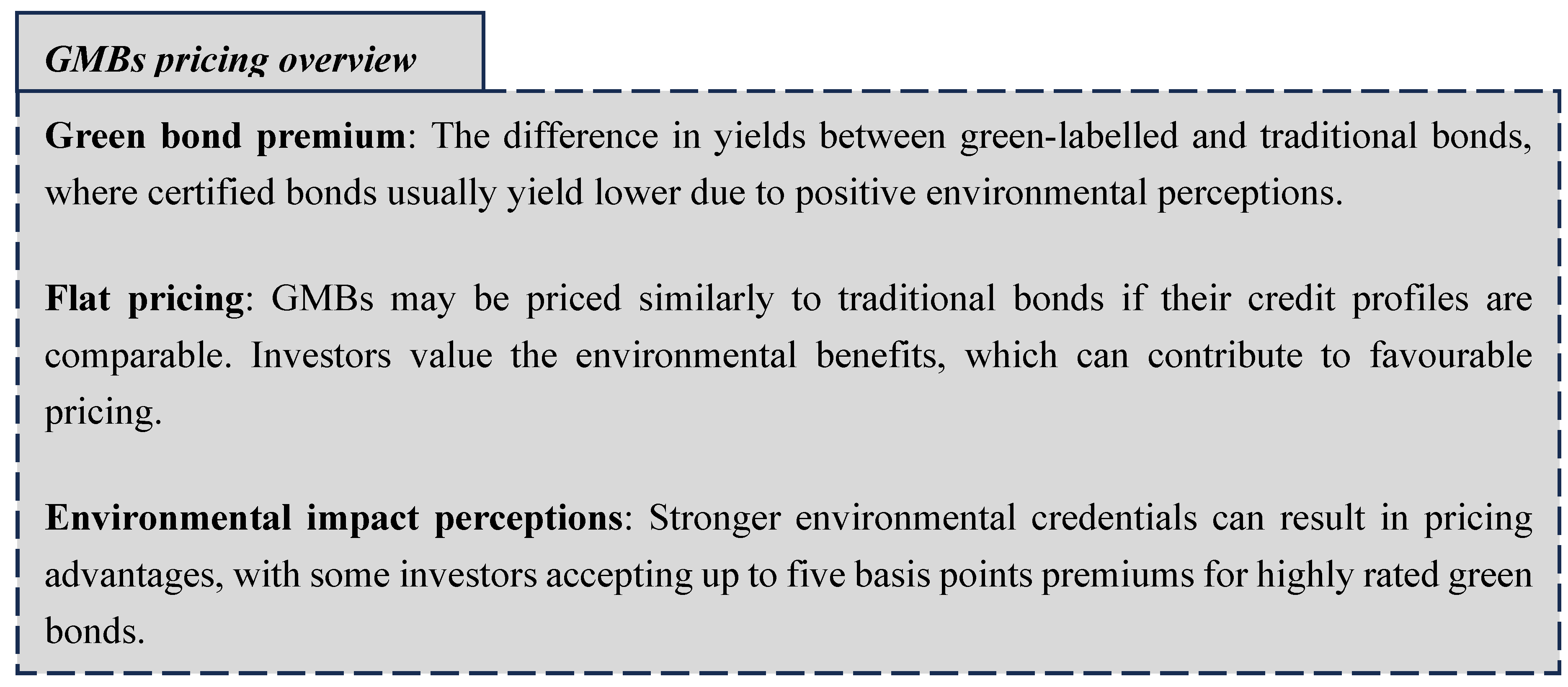

6.4. Certification and Pricing Overview of GMBs

GMBs can be certified by independent bodies like the CBI

20, which ensures they meet strict environmental standards and align with the Paris Climate Agreement goals. Certification increases investor confidence by preventing greenwashing and assuring the funds’ genuine environmental impact. Certified bonds typically have more favourable pricing, often yielding 24–36 basis points lower than uncertified bonds due to this added assurance.

Cape Town’s green bonds have received accreditation from the CBI, ensuring they meet stringent environmental standards. Africa’s first municipal green bond was issued by Cape Town in 2017. Initial guidance indicated a spread of 140-160 basis points over comparable local-currency government bonds.

Johannesburg’s green bonds lack formal certification by independent bodies like the CBI. However, Johannesburg also issued green bonds in 2014, contributing to South Africa’s total green bond issuances. Non-certified bonds may face different pricing dynamics due to investor confidence and certification status.

7. Case Studies

Experiences with launching municipal bonds across sub-Saharan Africa have shown varying outcomes, underscoring significant challenges that provide valuable insights for other SNGs considering GMBs. This article delves deeper into these issues, with a specific focus on Cape Town and Mexico, offering lessons learned and strategic considerations for future issuances.

7.1. Case Study 1: Cape Town

7.1.1. Context

Cape Town’s issuance of green bonds was driven by its commitment to environmental sustainability and climate change mitigation. The city’s strategic climate action plans (Cape Town’s Climate Change Strategy and Resilience Strategy) aimed to align financial strategies with these environmental objectives, directing funds towards projects that enhance climate resilience and sustainable development. Prior to green bonds, Cape Town had a history of issuing traditional bonds for municipal projects. The shift to green bonds was motivated by the growing sustainable finance market and the city’s intent to attract environmentally conscious investors.

The funds from Cape Town’s green bonds were allocated to projects, such as water infrastructure enhancement and climate resilience measures, including water treatment facility upgrades and water supply security. Cape Town adhered to the Climate Bonds standard for impact reporting, providing transparency and accountability through annual reports detailing the environmental impact of funded projects. The city implemented a robust reporting framework to track the environmental benefits of the funded projects. This involved annual reporting on various metrics, including expected carbon reduction and improvements in water management. These reports were incorporated into the city’s financial statements, ensuring transparency and accountability in the use of green bond proceeds.

The market reception for Cape Town’s green bond was positive, with significant oversubscription indicating strong investor interest. However, it's important to note that the actual financial benefit of issuing the green bond was questioned, as the city did not observe a substantial difference in investor behaviour compared to traditional bonds. While competitively priced, the green bond’s issuance costs were higher due to the rigorous pre-issuance assessments and compliance with green bond standards. The city leveraged the expertise of firms like KPMG to ensure compliance with necessary certifications and criteria, which, although resource-intensive, helped secure a competitive rate for the bond.

7.1.2. Challenges

Table 4.

Challenges faced in the green municipal bond issuance.

Table 4.

Challenges faced in the green municipal bond issuance.

| Challenge |

Description |

| High costs |

The issuance process incurred substantial costs for certifications and compliance with reporting standards, which, coupled with the lack of observed financial benefits, presented a challenge, particularly given the questionable financial benefits derived from the green bond compared to traditional bonds |

| Lack of financial incentive |

Investors showed interest in the green bond for its propaganda (PR) value but were not willing to accept lower returns for the sake of environmental benefits. This lack of financial incentive made the green bond less attractive from a purely financial perspective, leading to scepticism about its overall benefit |

| No subsequent issuances |

The absence of further bond issuances following the green bond suggests that the experience did not fully meet the city’s expectations, highlighting the need for careful evaluation of future issuances |

7.1.3. Outcome: How Does the Future Look Like?

Cape Town continues to explore sustainable finance options, but the experience with the green bond has led to a more cautious approach. The city is likely to weigh the benefits of green bonds against the practical considerations of cost and administrative burden. Future bond issuances will be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, with a focus on achieving the lowest cost of finance to support green projects.

Investor sentiment towards green bonds remains generally positive, driven by the growing emphasis on ESG criteria in investment decisions. This shapes the city’s approach to future issuances, ensuring that any green bonds offered must also meet stringent financial criteria to attract investment.

While the green bond issuance positioned the city as a leader in sustainable finance, it also highlighted the significant costs and questionable financial benefits associated with such instruments. As Cape Town navigates the evolving landscape of municipal finance, its commitment to economic sustainability and fiscal responsibility will guide its approach to future bond issuances, ensuring that the chosen financial strategies are both environmentally and economically sound.

7.2. Case Study 2: Mexico City

7.2.1. Context

In 2016, Mexico City issued its first municipal green bond which aimed to finance sustainable urban development projects, aligning with the city’s climate action strategy to reduce carbon emissions and enhance resilience against climate change.

21 The issuance was driven by Mexico City’s commitment to sustainable growth and the need to address pressing environmental challenges, such as air pollution and water management. The green bond was seen as a tool to fund projects that would contribute to the city’s decarbonization goals and improve the quality of life for its residents.

The city raised $50 million through the green bond, which was oversubscribed by 2.5 times, indicating strong investor interest. The funds were allocated to projects focusing on sustainable transport, water and wastewater management, and energy efficiency. Proceeds from the green bond were directed towards the development of bus rapid transit lines, modernization of the water distribution network, and installation of LED streetlights, among other initiatives.

7.2.2. Challenges and Outcome

The green bond issuance process revealed higher costs due to the need for certifications and compliance with green bond standards. Additionally, the bond faced criticism for not adequately addressing socio-economic disparities and climate injustices within the city’s infrastructure.

Mexico City’s experience with green municipal bonds has been a learning curve, highlighting the need for a balanced approach to environmental and financial objectives. While green bonds have the potential to support climate action initiatives, traditional bonds remain a practical alternative for funding sustainable projects, especially when considering the administrative burden and costs associated with green labelling.

8. Conclusions

8.1. Debunking Myths Surrounding GMBs

In our analysis, we've identified several misconceptions that drive the apparent shift to GMBs. However, our findings reveal key insights that challenge these common myths:

Myth 1: Green bonds always offer better financial terms - While green bonds attract investors with their environmental appeal, they do not necessarily offer better financial terms than traditional bonds. The financial attractiveness of green bonds can be similar or even less favourable due to the additional costs involved in certification and reporting.

Myth 2: Green bonds guarantee environmental impact - The environmental impact of green bonds can vary significantly. Without proper certification and diligent reporting, there is a risk of "greenwashing," where projects may not be as environmentally beneficial as claimed.

Myth 3: Green bonds are the only option for eco-friendly projects - Traditional bonds can also effectively finance green projects. Sometimes, traditional bonds come with lower issuance costs and less complexity compared to green bonds, making them a viable option for sustainable initiatives.

Myth 4: Green bonds are tax-exempt - While municipal bonds, including green bonds, often offer tax advantages such as exemption from federal income tax, they are not universally tax-exempt. The interest from some green bonds, particularly private activity bonds, may be subject to the alternative minimum tax (AMT).

22

8.2. Key Takeaway & Recommendations for SNGs

Conclusively, GMBs often entail higher costs and complexities, leading many SNGs to revert to traditional bonds for financing green initiatives. However, despite these challenges, GMBs play a crucial role in supporting economic development and sustainable growth. It is essential to reassess the value proposition of GMBs in the context of these considerations:

Cost considerations: Contrary to popular belief, green municipal bonds have proven to be more expensive due to the costs associated with certification, monitoring, and reporting.

Effort and complexity: The additional effort required for green bond issuance is substantial, posing a significant challenge for replication after the first transaction.

Investor demand: Initial enthusiasm has not translated into sustained investor demand. Most traditional investors prioritize financial returns over green labels, often resulting in less favourable terms for green bonds compared to traditional bonds.

To navigate the complexities of financing green projects, SNGs should consider the following strategies:

Strategic use of traditional bonds Leveraging traditional bonds for financing green projects can offer a simpler and more cost-effective approach.

Policy reforms Advocating for policy reforms that reduce the administrative burden and costs associated with green bonds, making them more accessible and appealing.

Market education Educating the market on the realities of green bond financing to set realistic expectations and foster a more informed investor base.

Diversification of funding sources Encouraging SNGs to diversify their funding sources, including exploring public-private partnerships and grants for green projects.

Conflict of Interest

All authors certify that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Abbreviations

| SNGs |

Sub-National Governments |

| GMBs |

Green Municipal Bonds |

| DFI |

Development Finance Institution |

| TURF |

The Urban Resilience Fund |

| NDBs |

National Development Banks |

| LGFF |

London Green Finance Fund |

| PPIAF |

Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility |

| SNTA |

Sub-National Technical Assistance |

| GBP |

Green Bond Principles |

| CBI |

Climate Bonds Initiative |

| AMT |

Alternative Minimum Tax |

| 1 |

Green Municipal Bonds |

| 2 |

Climate Bonds Initiative |

| 3 |

Sub-national governments |

| 4 |

Sub-national government |

| 5 |

Development Finance Institutions |

| 6 |

Value of carbon market worldwide from 2018-2022 |

| 7 |

Public-private partnerships |

| 8 |

Corporate Social Responsibility |

| 9 |

United States Environmental Protection Agency, Green Banks |

| 10 |

United Kingdom Debt Management Office, about PWLB |

| 11 |

London Green Finance Fund |

| 12 |

Greater London Authority |

| 13 |

Public Works Loan Board |

| 14 |

UK Infrastructure Bank; “About us” overview |

| 15 |

Value of carbon market worldwide from 2018-2022 |

| 16 |

Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility |

| 17 |

Sub-National Technical Assistance |

| 18 |

Municipal bonds ‘munis’ |

| 19 |

Green Municipal Bonds |

| 20 |

Climate Bonds Initiative |

| 21 |

Mexico Green Bonds for Climate Action |

| 22 |

CPA Advisor; tax pros and cons |

References

- Allison, B., & Vince, B. (2021, June). Harvard Law School, Bankruptcy Roundtable. https://bankruptcyroundtable.law.harvard.edu/2021/06/01/the-municipal-bond-cases-revisited/.

- Bonds & Loans. (2017, November). Case Study: Cape Town Wins Race to Issue Africa’s First Municipal Green Bond: https://bondsloans.com/news/case-study-cape-town-wins-race-to-issue-africas-first-municipal-green-bond.

- British International Investment. British International Investment Commits €20 Million to The Urban Resilience Fund. March 2023. https://www.bii.co.uk/en/news-insight/news/british-international-investment-commits-eur-20-million-to-the-urban-resilience-fund/.

- Chen, James. Municipal Bond: Definition, Types, Risks, and Tax Benefits. Investopedia, May 2024. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/m/municipalbond.asp.

- Clapp, Christa, and Kamleshan Pillay. Green Bonds and Climate Finance. In Climate Finance: Theory and Practice, edited by Anil Markandya, Ibon Galarraga, and Dirk Rübbelke, 543-562. London: Routledge, 2017.

- Climate Bonds. (2017). Cape Town Green Bond Framework: https://www.climatebonds.net/files/files/Cape%20Town%20Green%20Bond%20Framework.pdf.

- Climate Bonds Initiative. Certification. https://www.climatebonds.net/certification.

- Climate Policy Initiative. (2022, October). Global Landscape of Climate Finance: A Decade of Data: https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/global-landscape-of-climate-finance-a-decade-of-data/.

- Connecticut Green Bank. Strategy + Impact. https://www.ctgreenbank.com/strategy-impact/.

- Delbridge, V., Sarr, K. D., Harman, O., Haas, A., & Venables, T. (2021, November). Enhancing the financial position of cities: evidence from Dakar: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2021/11/fsud_report_case_studies_dakar.pdf.

- Dorfleitner, G., Utz, S., & Zhang, R. (2021, April). The pricing of green bonds: external reviews and the shades of green. Review of Managerial Science: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11846-021-00458-9. [CrossRef]

- Gabrielle Walker, B. G. (2022, July). How carbon credits could actually help fight climate change: https://time.com/6197651/carbon-credits-fight-climate-change/.

- Global Infrastructure Hub. (2021) Cape Town Green Bond: https://www.gihub.org/innovative-funding-and-financing/case-studies/cape-town-green-bond/.

- Infrastructure Canada. Canada Infrastructure Bank. https://www.infrastructure.gc.ca/CIB-BIC/index-eng.html.

- Lütkehermöller, K. (2023). The little book of city climate finance. Beijing: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH.

- Manoj Sharma, J. L. (2023). Mobilizing Resources through Municipal Bonds: Experiences from Developed and Developing Countries. ISSN 2789-0619 (print); 2789-0627 (electronic).

- Mayor of London. Mayor of London’s Green Finance Fund Guidance. London City Hall, June 2023. https://www.london.gov.uk/programmes-strategies/environment-and-climate-change/climate-change/zero-carbon-london/london-climate-finance-facility/green-finance-fund/mayor-londons-green-finance-fund-guidance.

- Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board. (2019). Green Municipal Bonds: https://www.msrb.org/sites/default/files/Green-Municipal-Bonds.pdf.

-

NY Green Bank 2022 – 2023 impact report: https://greenbank.ny.gov/Our-Impact/Impact-Report.

- OECD/UCLG. (2016). Subnational Governments around the world: Structure and finance. A first contribution to the Global Observatory on Local Finances. https://uclg-localfinance.org/node/256.

- Paise, E. (2016, May). Dakar’s municipal bond issue: A tale of two cities. Africa Research Institute. Retrieved from Africa Research Institute. https://www.africaresearchinstitute.org/newsite/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/ARI_Dakar_BN_final-final.pdf.

- Recessary. Ho Chi Minh City Carries Out Trial of Carbon Credit Trading. Recessary, July 2023. https://www.reccessary.com/en/news/carbon-finance/ho-chi-minh-city-carries-out-trial-of-carbon-credit-trading.

- Reuters. India’s NSE Unit Launches First Municipal Bond Index. Reuters, February 2023. https://www.reuters.com/markets/rates-bonds/indias-nse-unit-launches-first-municipal-bond-index-2023-02-24/.

- Robbins, H. Cape Town - Green Municipal Bond Case Study. Interview by J. Gorelick, June 2024.

- Robertsen, Catrin. Climate Budgeting at Local Level. Presentation at DG ECFIN, C40 Cities, June 15, 2023, Brussels. https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/document/download/dc5d517e-864b-454f-87d5-afec6a27f2ed_en?filename=4.%20C40%20Climate%20Budgeting.pdf.

- Schüle, Franziska, and David Wessel. Municipalities Could Benefit from Issuing More Green Bonds. The Brookings Institution, July 2018. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/municipalities-could-benefit-from-issuing-more-green-bonds/.

- Sharma, M., Lee, J., & Streete, W. (2023, August). Mobilizing Resources through Municipal Bonds: Experiences from Developed and Developing Countries: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/901921/sdwp-088-mobilizing-resources-municipal-bonds.pdf.

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. (2022, November). Mexico City focuses on solutions and scale: https://mcr2030.undrr.org/news/mexico-city-focuses-solutions-and-scale.

- World Bank Group. Strengthening Urban Management and Service Delivery through Performance-Based Fiscal Transfers. Urban Development, September 2022. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/brief/strengthening-urban-management-and-service-delivery-through-performance-based-fiscal-transfers.

- World Economic Forum. (2023, November). Here’s how 3 cities are using municipal green bonds to finance climate infrastructure: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/11/heres-how-3-cities-are-using-municipal-green-bonds-to-finance-climate-infrastructure/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).