1. Introduction

Since 1990, a decrease in the global prevalence of tobacco smoking has been reported; however, due to population growth, the number of smokers has increased in many countries; it is estimated that more than 1 in 7 adults are current smokers, that is, more than one billion [

1]. The age-standardised prevalence of current tobacco smoking (<30 days) for 15 years and older was 6.6% among females and 32.7% among males; in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), 17.5% of males were current smokers and 2.9% of females. According to WHO [

2], the prevalence rates for smoking cigarettes among individuals 15 years and older are estimated to decrease in the period 2000 to 2025 in most parts of the world, while no change is projected in the WHO African and East Mediterranean regions with associated health implications for the smokers and the society at large.

Tobacco (smoked, second-hand, and chewing) is estimated to have killed about 8.7 million people in 2019 [

3]. Tobacco use is a significant risk factor for attributable morbidity for both sexes; tobacco ranked first as an attributable risk factor for the death of males and fourth for females. Lifelong nondaily smokers have higher mortality risks than never smokers, while daily smokers have a significantly increased risk of death from all causes [

4,

5,

6]. Many of these deaths were caused by non-communicable diseases (NCDs), such as cancers, cardiovascular diseases, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes. In low-income countries, NCDs are responsible for more than 2 in 3 deaths [

7]. In addition to the risk of increasing NCD prevalence, cigarette smoking contributes to the progression of communicable diseases, including HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis [

4,

8].

Interventions to reduce the number of deaths caused by NCD, as aimed for in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3.4, need to be context-specific and include tobacco control measures [

9]. The WHO introduced the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) in 2003, which supports countries in building anti-tobacco legislation [

10]. In total, 43 out of 46 countries in SSA have signed, ratified or acceded to the framework [

11]. Nonetheless, good intentions have not been followed by practical implementation, often hampered by actions of the tobacco industry targeting key policymakers, e.g., with financial incentives, and implementing the FCTC has been slow and fragmented [

11]. Guinea-Bissau ratified the FCTC in 2008 and signed the Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products (PEITTP) in 2014 [

11]. Nonetheless, the WHO has little data about smoking habits in Guinea-Bissau [

7]. Further, it belongs to West African countries that apply minimal taxation on tobacco [

12], legislation aiming to restrict tobacco use is lacking [

13,

14], and no national anti-tobacco health communication campaign has been reported in the period 2010–2020 [

15].

Here, we aimed to analyse the prevalence of lifetime, current and daily smoking among in-school adolescents in Bissau, the capital of Guinea-Bissau, and identify determinants for smoking cigarettes in the setting. We raise the following questions: How do the prevalence rates and determinants for smoking cigarettes compare to other settings in SSA and elsewhere? What difference, if any, is there between determinants for lifetime and daily smoking? Finally, what preventive actions are feasible for Guinea-Bissau based on our findings?

1.1. Prevalence of Cigarette Smoking in Africa

Prevalence rates of cigarette smoking vary across continents, within world regions and countries, and among population groups [

1,

7,

16]. According to the most recent data from the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS), including 143 countries, out of which 30 belong to the WHO African region, the global prevalence rate of cigarette smoking for in-school adolescents (13–15 years) at least once within the last 30 days (current users) was 11.3% for boys and 6.1% for girls [

17]. Based on at least one survey in 2010–2018, comparable prevalence rates for the African region were 8.6% and 3.7% for boys and girls, respectively, and in Europe, 10.6% for boys and 9,0% for girls. Among the world regions, the African region had the lowest prevalence rates of cigarette smoking for both girls and boys.

GYTS provide information about the prevalence of cigarette smoking among in-school adolescents aged 13-15 in the WHO African region. Analysis of GYTS data from 2003 in Addis Ababa found that 4.5% of males and 1% of females were current smokers, and boys had more than a four-fold increase in odds of being current smokers compared to girls [

18]. A study using GYTS data from 2006–2009 in nine West African countries found that the prevalence of adolescents’ lifetime smoking ranged from 5% in Ghana to 24% in the Ivory Coast [

19]. In another study using data from GYTS 2014–2017 from nine sub-Saharan countries, the current cigarette use of adolescents ranged from 1.0% in Tanzania to 15.4% in Seychelles [

20]. In all the countries, cigarette smoking prevalence was greater among males than females; among ever smokers in Tanzania, Ghana, and Sierra Leone, more than 20% initiated smoking at eight years, and in all countries, more than 75% had initiated smoking before 15 years.

Irrespective of the great inter-country variations in prevalence rates for adolescents smoking cigarettes, studies from SSA show consistently higher prevalence rates for boys than girls. Also, an analysis of the 2006-2011 GYTS data from 29 African countries reported that those exposed to second-hand smoking at home were more prone to cigarette smoking, and their susceptibility to start cigarette smoking was higher than for those exposed in public places [

21]. Further, a systemic review and meta-analysis found that among school-going adolescents in East Africa, the pooled prevalence of current smoking was 9.0%; factors contributing to adolescent cigarette smoking included being a male, higher age, peer influence, perception of risks, access to anti-smoking messages and marketing issues [

22].

1.2. Background to the Study

Information on prevalence rates for cigarette smoking among adults and adolescents in Guinea-Bissau is limited. Due to a lack of data, Guinea-Bissau was not included in calculations for the WHO Global Report on Trends in Prevalence of Tobacco Smoking 2000-2025 [

2]. In the Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD) 2019, the age-standardised prevalence rates of current smoking of tobacco in the country (all forms included) for 15 years and older was estimated to be 8.46% for males and 1.07% for females; no data source was provided [

1]. The most recent data come from the Unicef Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) 2018/2019 on current cigarette smoking among individuals aged 15-49, with prevalence rates that are higher for males than those reported from the GBD study (10.4%) but lower for females (0.2%) [

23]. The only available data on adolescents smoking cigarettes for Guinea-Bissau that we identified stem from the 2008 GYTS. The lifetime prevalence rate of cigarette smoking among in-school adolescents aged 13–15 was 5.4% (7.7% for boys and 3,0% for girls), while 5.1% were current smokers of cigarettes (7.2% and 3.0%, respectively) [

24].

The theoretical perspective of the research is guided by the Planet Youth model and the assumption that the social conditions contributing to adolescent substance use originate from multifaceted and intricate sources [

25]. Further, context-based evidence on protective and risk factors related to the peer group, family, school and leisure time lays a foundation for community-based preventive actions [

26,

27]. The model effectively reduces consumption by addressing various factors contributing to adolescent substance use [

28,

29,

30].

1.3. Aims of the Study

Here, in line with the approach of Planet Youth, we intended to lay the foundation for data-driven preventive actions against cigarette smoking in Guinea-Bissau, which lacks data and legislation on tobacco use, a situation linked to political instability [

31,

32,

33]. In recent years, Guinea-Bissau has been plagued by being a transit hub for the trafficking of drugs, coups and frequent changes of government [

34,

35,

36].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study was conducted in Bissau, the capital of the Republic of Guinea-Bissau. The country covers 36,125 km

2 on the west coast of Africa on a latitude of 12° North, with neighbouring Senegal and The Gambia to the north and the Republic of Guinea (Conakry) to the south. The Human Development Index 2021/2022 ranks Guinea-Bissau 177 out of 191 countries [

37]. Poverty is pervasive, with about 70% of the population living on less than US

$2 a day [

38].

2.2. Study Population

The population of Guinea-Bissau is estimated at 1.9 million; 42% are between 0–14 years, and 32% are young people aged 10–24 [

39]. At the time of the survey, the population in Bissau was estimated to be just less than half a million, with adolescents aged 14–19 being about one-quarter [

40]. About twenty ethnic languages are spoken in the country, while 11–14% speak the official language, Portuguese, the language of education, most of whom belong to Bissau’s educated elite [

41]. Portuguese-based Kriol is a language for interethnic communication. Almost half of the population adheres to the Islamic religion, about one-fifth to Christianity, and one-third to African religions.

2.3. Study Setting

Among Bissau-Guinean 6–11-year-old children, about 44% are out of school, and slightly less than one-third begin school at the correct age [

42]. For young, 41% of females and 55% of males have completed primary school [

43]. Repeated and extended teacher strikes have affected public schools badly in recent years. For instance, in 2016–2017, the academic year of data collection for this study, 46% of teaching time was lost in public schools; in 2015–2016, the loss was 65% [

44]. Further, parental education influences attendance at public or private schools, and overage attendance is common [

45].

2.4. Data Source

Planet Youth is an evidence-based international programme initiated by the Icelandic Centre for Social Research and Analysis (ICSRA) to decrease the likelihood of substance use among young people in Iceland [

25]. The questions and survey build on the approach used by other extensive surveys among adolescents on their substance usage, such as the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs [

46], Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children [

47], and Monitoring the Future in the United States [

48]. A multidisciplinary team of professionals within ICSRA and Planet Youth collaboration has developed and refined the survey questionnaire over the years, currently implemented in hundreds of communities on five continents [

49]. While aiming to improve preventive work for adolescents, focusing on tobacco, alcohol and other drugs, the survey includes questions on participants’ socioeconomic background, health and wellbeing, family, peers, school and leisure activities [

25,

50].

The survey questionnaire was translated into Portuguese and pilot-tested in three classes in one public school, targeting in-class students aged 15–16. The aim was to adapt the questionnaire to the context of adolescents in Bissau, assess their degree of difficulty in giving a response, and evaluate how long time it would take them to complete it. Subsequently, the wording of some of the survey questions was revised, and those judged to be of least relevance for Bissau-Guinean adolescents were excluded to give the participants more time to complete the survey within the allocated 90 minutes (two classroom sessions) in each of the participating schools. The final questionnaire included 312 questions divided into 77 main themes.

2.5. Data Collection

The data collection was conducted in Bissau from 7 to 29 June 2017 and followed a distinct and well-established methodology by ICSRA [

51]. The sample size was calculated with a power of 95% and a 0.05 margin of error to detect differences between two equal-sized populations; the minimum sample size was 385 participants. As most schools lacked electronic class registers, the research team created one in Excel that included classes in 17 schools (12 public and five private) in which at least one-third of the students were within the target age group of 15–16 years. The specially compiled Excel file included 4,470 students enrolled in 116 classes in grades 7-10, or about 20% of the approximately 24,000 students who were projected to have been enrolled in Bissau at the time. Each class in the Excel file was assigned a computer-generated random number, sorted in ascending order to select which classes should be invited to participate, aiming to reach at least a cumulative number of 2,000 survey participants. When the data collection had started, one private school decided not to participate for practical reasons. From this specially designed Excel file, 2,110 (47.2%) students participated in the survey. As classes are characterised by mixed age groups and many over-age students, the final sample included students aged 14–19.

The randomly selected classes were organised by school and teaching session (morning or afternoon) to implement the survey simultaneously in each school and cause minimal disruption. The date of survey implementation was agreed upon with the head teacher, the two contact persons in each school, and the teachers in those classes who had been randomly selected to participate. At the beginning of each class session, the research team introduced the survey to the students together with head teachers and teachers. Examples of how to fill in responses in the different question formats were given on the blackboard; in case of difficulties, the authors/instructors advised the students as requested while taking care not to influence them or observe their final response. Afterwards, the students said they had enjoyed the experience and found it easy to fill in their answers. After completing the survey, within 60–90 minutes, the students put the anonymous questionnaire into a provided envelope without any personal identifier, sealed it, and delivered it to the attending teachers and the authors.

2.6. Measures for Dependent Variables

The questionnaire used in Bissau included two questions on participant’s usage of cigarettes. The first was “How often have you smoked cigarettes in your lifetime?” with seven response alternatives from never to gradually increasing the number from once or twice to 40 times or more. Lifetime smoking experience was defined as having smoked at least 1-2 times and recoded to 1; those with no experience were recoded to 0. The second question addressed the current and daily usage of cigarettes: “How much have you smoked, on average, during the last 30 days?” It had seven response alternatives, from none to gradually increasing the number of weekly or daily cigarettes. Current smoking was defined as at least one cigarette <30 days and daily smoking reporting at least 1-5 cigarettes daily; the two variables, respectively, were recoded to 1 for those with the experience and 0 for those with no experience.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

ICSRA at Reykjavík University scanned the forms and digitised the data for statistical analysis in JMP Pro 16.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Out of 2,110 questionnaires handed in by participants, 2,039 (96.7%) were successfully digitised and made up the total number of adolescents who participated in the survey; reasons for exclusion included, for instance, forms without usable information, non-adherence to the questionnaire format and incompatible answers. Initially, descriptive statistics were conducted on all the study variables and widely disseminated to participating schools and national policymakers [

52]. Missing values were excluded in the calculations for descriptive statistics and bivariate analysis. Both the dependent and explanatory variables were then recoded to a nominal variable (exposed to the experience=1; not exposed to the experience=0) for contingency analysis (log-likelihood function) to identify significant explanatory variables for the dependent variables “lifetime cigarette smoking” and “daily cigarette smoking”. The Chi-square test was used (p<0.05) to find significant associations, and odds ratios (OR) were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI) to evaluate the quantity of that association. Potential explanatory variables for the dependent variables were then introduced into a multinomial logistic regression model that creates a coding system that accommodates missing values in effects [

53]. Non-significant variables (p-value 0.05 or higher) were gradually removed from the model, and RSquare (R

2) was calculated for the final model. To graphically evaluate the effect sizes for significant explanatory variables with very small p-values, these were transformed to the LogWorth (–log10(p-value)) scale. The larger the LogWorth value, the stronger the effect of the variable in the model [

53,

54].

2.8. Ethics

Most participants were aged 14–17 and classified as children per the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) [

55]. CRC highlights children’s right to express an opinion on their situation (Art. 12) and participate as appropriate for their age (Art. 3, 5, and 12). Scholars have highlighted the risk that parental consent requirements in research with children might contribute to biased data and low response rates [

56,

57]. Others have called for socio-culturally responsive ethics reviews [

58,

59]. Considering the students’ mature age as children and the study’s setting, pre-parental approval was not sought; the adolescents decided to participate in the survey without any personal identifiers.

The Minister of Education approved the study (No/Ref 250/MEES/GM/2017). Each headteacher also approved participation in the schools. At the time of implementation, it was emphasised to the students that their participation was voluntary, that filling out the questionnaire was not an examination, and that they could leave to answer some or all the questions.

3. Results

The total number of participants was 2,039, aged 14–19, thereof 1,024 (51,7%) girls. There was no statistically significant difference in the average age for girls (16.3 years, SD 1,2) and boys (16.4 years, SD 1.2). In total, 1,617 (85,2%) of study participants had never smoked a cigarette; of those 280 with lifetime smoking experience, 132 (7.0%) had only smoked once or twice, while 49 (2.6%) had smoked cigarettes at least 40 times or more. In total, 119 (6.5%) were current smokers: 77 (8,8%) of the boys and 37 (4,1%) of the girls. Out of 45 daily smokers (2.2%, 35 boys), 28 (62%) smoked 1–5 cigarettes daily and nine more than 20 cigarettes daily. The socioeconomic characteristics of the study group are found in

Table 1 with associated p-values.

The statistically most significant influential factors for smoking cigarettes were sex, school type, education of parents and experience of social media (

Table 1).

3.1. Parental Support

Five survey questions enquired about parental support in the participants’ daily lives (

Table 2).

For respondents reporting lifetime smoking experience, results for four out of five questions were statistically significant and in three out of five for daily smokers (

Table 2). The results indicate that adolescents with parents monitoring their behaviour and whereabouts smoke less. When evaluated across all five variables as one composite variable, “parental monitoring”, the results were statistically significant for lifetime smoking experience but not daily smoking with OR 2.46 (95% CI 1.39-4.33 and 2.05 (0.61-6.84), respectively.

Two survey questions enquired about the smoking behaviour and attitudes towards smoking within the participant’s family. Those who were exposed to second-hand smoking within the family (father, mother and/or sibling smoked tobacco daily) were 1.90 times (95% CI 1.42–2.55) more likely to have a lifetime experience of smoking and 5.10 times (95% CI 2.62–9.94) more likely to be daily smokers compared to those not exposed to indirect smoking.

3.2. Peer Group

Nine survey questions addressed the attitudes of friends to substance usage and violent behaviour (

Table 3). Experience of smoking, either lifetime or daily, was significantly related to friends’ attitudes to and usage of substances, e.g., tobacco, alcohol and cannabis and violent behaviour within the group in all nine questions, with the highest odds for daily smokers.

3.3. Violence and Smoking Behaviour

3.3.1. Domestic Violence

The survey included five questions on participants’ experience of domestic violence as an influential factor for smoking cigarettes (

Table 4). All five experiences were significantly related to lifetime experience of smoking cigarettes, but not for daily smokers. The odds for lifetime experience of domestic violence across the five questions for those with lifetime experience of smoking was 1.79 (95% CI 1.36–2.38) and 1.81 (95% CI 0.91–3.58) for daily smokers.

3.3.2. Sexual Abuse

Seven survey questions enquired about participants’ experience of sexual abuse, and all were significantly related to a lifetime and daily smoking (

Table 5a–g). The odds were exceptionally high for daily smokers who reported they had exerted sexual violence against another person (

Table 5 e-g).

A lifetime experience of having been a victim of sexual violence across the four questions (

Table 5 a-d) was recoded into one composite variable, “victim of sexual violence”; the odds were 1.88 (95% CI 1.42–2.49) for lifetime experience of smoking cigarettes and 2.51 (95% CI 1.30-4.83) for daily smokers. Similarly, the odds for lifetime experience of smoking and daily smoking among participants who reported they had forced someone to have sexual relations (

Table 5 e-g) were 4.05 (95% CI 2.89-5.68) and 11.46 (95% CI 5.88-22.35), respectively.

About two-thirds of the participants (68.1%) out of 1,740 reported no experience of sexual relations. Of 555 participants who reported having had sexual relations, 96 (17.3%) were 11 years or less for the first time, and 20 (21%) were girls. Participants who reported their first sexual relation when they were 11 years or younger were significantly likelier to have a lifetime experience of smoking cigarettes and being daily smokers than those without that experience (

Table 5h).

3.3.3. Relational Problems

Four survey questions enquired about relational problems with peers and in school (

Table 6 a-d). All were significantly related to a lifetime experience of smoking, and four out of five for daily smokers.

3.3.4. Stealing and Vandalising

Five survey questions asked about participants’ experience of stealing and vandalising during the last 12 months (

Table 7). All five were statistically significant for lifetime experience of smoking cigarettes and daily smoking; the odds were exceptionally high for daily smokers.

A lifetime experience of stealing and vandalising across the five questions was then recoded into one composite variable, “stealing and vandalising”; the odds for lifetime experience of smoking cigarettes and daily smoking were 2.80 (95% CI 2.11–3.72) and 4.09 (95% CI 2.21–7.59), respectively.

Five survey questions enquired about participants’ violent behaviour, that is, if they had punched, knocked, kicked, hit/slapped and helped to beat somebody once or more times during the last 12 months. The odds were 2.88 (95% CI 2.16–3.84) for participants with any experience of physical violence across the five questions to have a lifetime experience of smoking cigarettes and 3.01 (95% CI 1.46–6.20) for daily smoking compared to those without the experience.

3.3.5. Other Uses of Tobacco

Three additional survey questions enquired about the experience of waterpipe smoking, chewing tobacco and using snuff. Out of 1,884 participants, 333 (17.7%) reported lifetime experience of smoking with waterpipes; the odds for those with lifetime usage of waterpipe were 3.53 (95% CI 2.65–4.72) to be more likely to have a lifetime experience of smoking cigarettes than those without the experience; for daily smokers, the odds were 3.28 (95% CI 1.69-6.26). Out of 1,889 participants, 54 (2.9%) had experience of chewing tobacco. Compared to those who did not report having chewed tobacco, the odds were 8.61 (95% CI 4.84–15.31) to be more likely than those not chewing tobacco to have a lifetime cigarette smoking experience. For snuff, out of 1,736 participants, 79 (4.6%) had a lifetime experience of snuff usage. The odds for those with a lifetime experience of using snuff were 3.81 (95% CI 2.18–6.66) for also having a lifetime experience of smoking cigarettes.

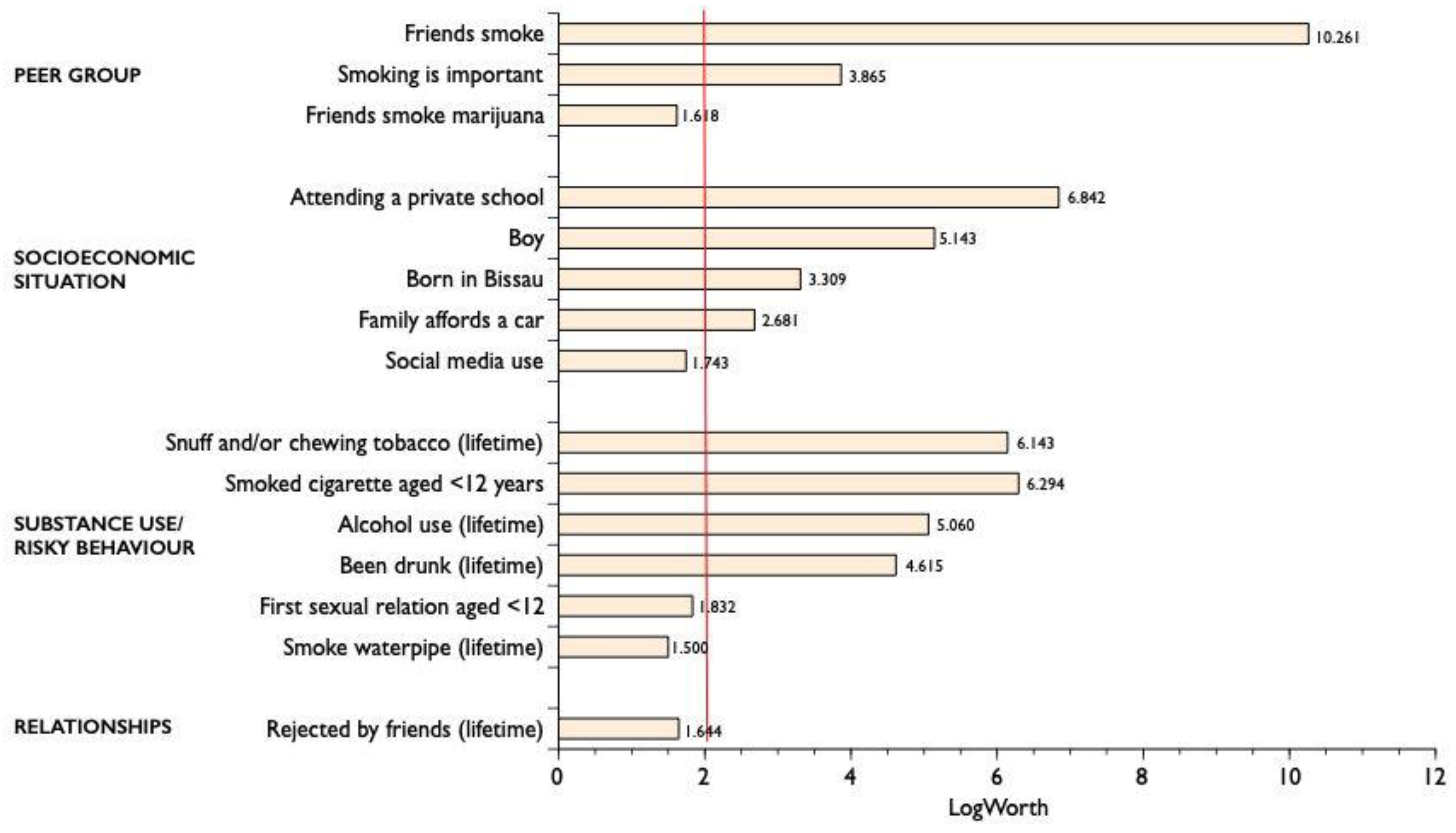

3.4. Multinomial Logistic Regression

Following the bivariate contingency analysis, 48 variables were introduced into a multinomial logistic regression model to identify explanatory variables for the dependent variables “lifetime smoking” and “daily smoking” of cigarettes. For lifetime experience of smoking cigarettes, the final model (R

2=0.3726), p=0.000) included 15 statistically significant variables (

Figure 1).

The most significant variable was having friends who smoked, but other highly significant variables included diverse substance use, attending a private school and being a boy.

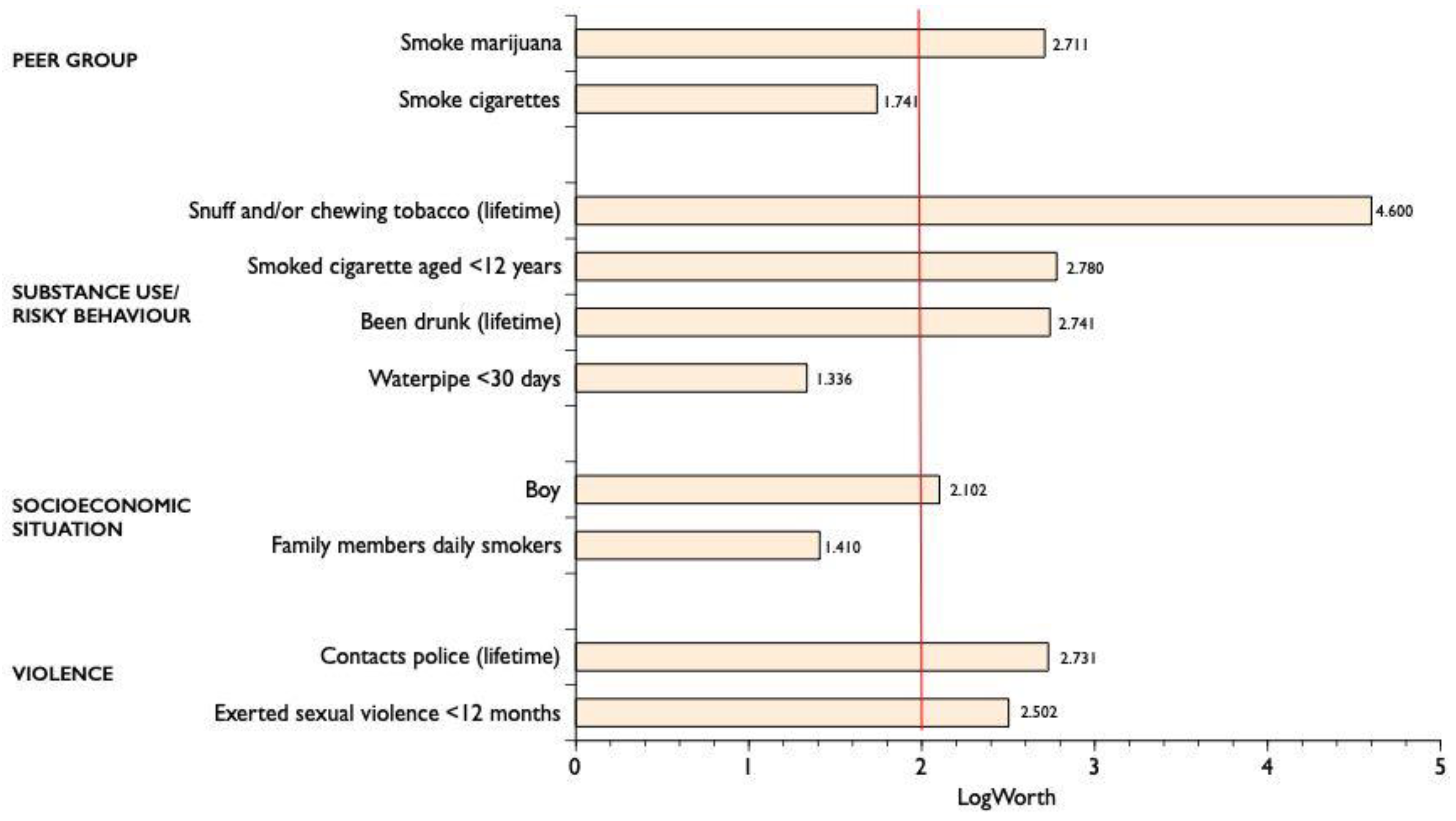

For daily smokers, the final model (R

2=0.5194), p=0.000) included 13 statistically significant explanatory variables (

Figure 2).

Both models included the variables “Been drunk (lifetime)”, “Boy”, Smoked cigarettes aged <12 years”, and “Snuff and/or chewing tobacco (lifetime)”.

4. Discussion

Here, we present results from a survey among randomly selected school-attending adolescents aged 14–19 in Bissau, the capital city of Guinea-Bissau. To address the existing gap in knowledge in the setting, the study aimed to analyse the prevalence rates for lifetime experience, current use and daily smoking of cigarettes, and determinants for smoking in the setting. Overall, compared to other countries, both within the continent and elsewhere, the prevalence rates of smoking cigarettes are at the lower end, with 14.8% lifetime smoking while 6.5% were current and 2.2% daily smokers. As elsewhere on the continent, boys were more frequent cigarette smokers than girls. Further, the importance of the peer group was evident in both groups of lifetime and daily smokers. Multinomial logistic regression analysis identified distinct determinants for these two groups. Most importantly, smoking experience was significantly linked to peer behaviour, socioeconomic background, experimenting with diverse substance use and violent behaviour.

4.1. Prevalence Rates

Comparison of prevalence rates is prone to difficulties because the timing of implementation of the study, age of adolescents and sampling strategies may vary. According to the most recent GYTS studies implemented in 2010–2018, in the WHO African region, the prevalence rate of current smoking of tobacco was 11.3% for boys and 6.1% for girls [

17]; our prevalence rates for current smoking of cigarettes from 2017 are lower than those, or 8.8%% for boys and 4.1 for girls. Here, the differences in time of implementation and age are minimal. Our adolescents were slightly older; however, we did not find age to be an influential factor, probably modified by the mixed age groups in class and peer influence on smoking behaviour. While GYTS used national sampling, ours was limited to the capital. In the most recent MICS conducted in Guinea-Bissau in 2018/2019, the prevalence rates for current smoking of cigarettes among individuals aged 15-49 were 10.4% for males and 0.2% for females; for males, the rates were higher in rural areas than in urban ones while the reverse was the case for females [

23].

The only prevalence rates in Guinea-Bissau for adolescents aged 13–15 stem from the GYTS, conducted in 2008 [

24]. Compared to our data on adolescents aged 14–19 indicate an increased prevalence of current smoking of cigarettes; the overall prevalence rate was 5.1% in 2008 compared to 6.4% in our study conducted in 2017. While GYTS is a national sample of in-school adolescents, our sample is entirely from Bissau. These results and our findings call for a study on cigarette smoking in a national random sample of adolescents.

Globally, GYTS data on adolescents aged 13–15 indicate varied gender differences among world regions, with higher prevalence rates among boys than girls, with the highest differences in the African region and the lowest in Europe [

17]. In our sample, the prevalence of smoking cigarettes among boys, lifetime and current, was 19.1% and 8.8%, compared to 10.6% and 4.1% among girls, respectively. Most importantly, in our sample, 4.0% of boys and 1.0% of girls report smoking at least 1-5 cigarettes daily (

Table 1), a habit that is associated with the most severe long-term health consequences [

6].

In contrast to gender differences in smoking cigarettes, no significant gender difference was found for waterpipe smoking in the same sample of in-school adolescents [

60]. In some settings, social and cultural factors discourage women from smoking cigarettes, while the marketing of waterpipe smoking focuses on young women [

61,

62]. Further, the high prevalence of waterpipe smoking in Bissau reflects an ongoing global trend of decreased cigarette smoking in the period 1999–2018 while other tobacco use is on the increase [

17]; for example, in Bissau, 15.0% reported waterpipe use within the last 30 days [

60].

4.2. Determinants for Tobacco Smoking

Our results highlight the importance of peers for adolescents’ smoking, both for lifetime and daily smoking status (

Table 3); in the multinomial logistic regression model, the effect size of peers was huge compared to all other significant influential factors for lifetime and daily smoking (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The peer influence is also reflected in adolescents’ use of alcohol and cannabis, a finding consistent with their susceptibility to alcohol and other drug use [

63] and waterpipe smoking [

60]. These results align with studies conducted in diverse settings globally [

22,

64,

65].

Parental oversight and support to their children have been identified as protective factors for the health and wellbeing of adolescents [

25,

66], and their education is linked to anticipated greater expectations of university attendance [

67]. In our study, participants who reported less parental monitoring of their activities and whereabouts at night and less contact with their friends’ parents were significantly more likely to have a lifetime experience of smoking and being daily smokers (

Table 2). Further, our results highlight how family members’ smoking of cigarettes daily influence the smoking behaviour of their children, in line with results elsewhere from West Africa [

19].

In our study, attending a private school, one proxy indicator of wealth [

45], was an important determinant for a lifetime and daily smoking experience (

Table 1 and

Figure 1). Further, bivariate analysis indicates that adolescents with better-educated parents were significantly more likely to have a lifetime experience of smoking and be daily smokers than those with less educated parents (

Table 1). Smoking has been identified as a modifiable determinant to address inequalities in health across Europe, as measured by socioeconomic status [

68]. Indicators of interest include low parental education while being modified by race and ethnicity [

64] and the level of educational differentiation within countries [

69]. In a study in Ghana, most smokers came from high-income families [

19]; in Zimbabwe, students in private schools had a higher prevalence of smoking than those in public schools [

70].

Access to digital technology indicates financial resources; in our study group, less than half had access to a laptop or a computer in the last 12 months, and one-third had never used digital media [

71]. Despite this limited use in our sample, access to social media was significantly associated with the experience of smoking cigarettes and being a daily smoker compared to those who did not have such access (

Table 1). In a multinomial logistic regression model, social media usage was a statistically significant explanatory variable for lifetime smoking experience (

Figure 1). Considering the relatively limited visibility of tobacco advertisements in the urban landscape of Bissau, exposure to them is most likely through social media, and these media have been linked to the increased prevalence of smoking [

64]; our results from Bissau might indicate this to be the case for smoking adolescents in our sample, as noted elsewhere in the African region [

19,

20].

In our study, participants with a lifetime smoking experience reported more exposure to domestic violence than non-smokers (

Table 4a–e). This finding is in line with results from the United States that indicate that an experience of child physical abuse was significantly related to a higher intensity of smoking among adolescents [

72].

In our study, an experience of sexual abuse was significantly related to a lifetime experience of smoking and daily smoking (

Table 5a). The results were also significant irrespective of the setting of the sexual abuse, with the perpetrator either being an adult within the family or an outsider (

Table 5b-c). Interestingly, the odds for daily smokers were high for the composite variable “exerted sexual violence” during the last 12 months (

Table 5 e-g). Similarly, in multinomial logistic regression analysis, daily smoking of cigarettes was significantly related to lifetime experience of having exerted sexual violence against another person (

Figure 2). Likewise, having the first sexual relation at an age younger than 12 years of age is also one form of sexual abuse; in our study, the prevalence rates for those who reported such experience were significantly higher for both lifetime and daily smoking (

Table 5h). In line with these results, experience of sexual abuse has been identified as a risk factor for substance abuse, including smoking cigarettes [

73].

Multivariate analysis identified shared significant determinants for lifetime and daily smoking, that is, male gender, age at initiation of smoking, peer influence and other substance use (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). For those with a lifetime experience, the impact of peer relations is particularly significant (

Figure 1). For daily smokers, in addition to peers and diverse substance use, contacts with the police and exerting sexual violence against another person stand out as influential factors (

Figure 2).

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

The study has several strengths. First, it is the first of its kind in a setting with limited data on adolescents’ smoking of cigarettes and its determinants. Second, the random sample was drawn from a specially designed class-based register targeting school-attending adolescents in the capital city, either in public or private schools; further, it is much larger than the required sample size of 385 to detect significant differences between two equal-sized populations. Third, within the two groups of students with lifetime experience and daily cigarette use, the study identified several explanatory determinants for smoking that these students share with peers in other settings (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). Finally, the survey applied a questionnaire developed and designed by an interdisciplinary group of professionals within Planet Youth [

25].

Our research has some limitations. First, the study participants are school-attending adolescents residing in the capital city, where two out of five peers do not attend school [

45]. Our study provides no information on this demographic, such as those residing in rural areas or those out of school. Second, the low number of participants who smoke daily calls for caution when analysing potential determinants, yet the number is sufficiently large when analysing subgroups in a well-defined random population sample such as ours [

74]. Finally, the data collection was in June 2017; thus, it may not accurately reflect the current situation.

4.4. Implications for Practice and Policy

This research has identified a small group of school-attending adolescents in Guinea-Bissau who were daily cigarette smokers, mainly boys, and a larger male-dominated group of experimental smokers. As cessation of smoking support for adolescents who already are daily smokers is fraught with challenges [

75], it is imperative to plan for and carry out primary preventive actions that target both in- and out-of-school children and young people in the setting. The significant influence of peers on smoking behaviour within the study sample implies the need for policymakers in Guinea-Bissau to engage with young people in designing and developing strategies to prevent the initiation of tobacco use in this demographic [

15]. Preventive actions need to build on evidence, first on a diagnosis of the current situation, as our study, followed by appropriate interventions developed in collaboration with adolescents and young people [

29,

30,

50].

Nonetheless, interventions to reduce adolescent smoking of tobacco give heterogeneous results, depending on methodologies, cultural aspects, and unevenly effective implementation [

76,

77,

78,

79,

80]. It highlights the need for well-designed studies that allow impact evaluation to guide evidence-based preventive practice in the setting with potential implications elsewhere. Further, such research could also focus on the longitudinal workings of peer social networks and how these influence choices of health-related behaviour [

81].

While any form of tobacco usage is unsafe with potential adverse health consequences, its use in the SSA region is projected to rise with the tobacco companies targeting this emerging market [

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87]. However, the companies increasingly market other products, and their use is on the rise [

17]; in Bissau, this is exemplified by a high prevalence of waterpipe smoking among adolescents with no discernible gender difference, unlike daily cigarette smoking [

60]. Policymakers could focus their tobacco control efforts on a less-stigmatised singular substance, such as waterpipe usage compared to cigarette smoking, to achieve the desired preventive impact on overall substance usage in the setting.

Comprehensive tobacco control, in line with the FCTC, is widely recommended for preventing various tobacco use [

76,

88]. Guinea-Bissau ratified the FCTC in 2008 and signed the PEITTP in 2014 [

11]. Mitigation efforts should include adopting laws and developing strategies to limit the promotion, sale and use of tobacco and new and emerging products, as well as national monitoring guided by the FCTC [

7]. Increased taxation is also a strategy that lowers the prevalence rates of tobacco use among adolescents [

89].

5. Conclusions

At the outset, we aimed to answer three research questions regarding adolescents’ smoking of cigarettes in Guinea-Bissau. Our data indicate that the prevalence rates of current and daily smokers are lower compared to many neighbouring countries but, as found elsewhere, show significantly more smoking of cigarettes among boys than girls. Further, despite limited data on the smoking of cigarettes in the country, we discern a trend of increasing use, including that of other tobacco products, particularly waterpipe smoking. On determinants for smoking tobacco, as seen around the globe, our data highlight the strong impact of peers and parental monitoring on adolescents’ health-related behaviour, such as smoking cigarettes and links to their use of other substances. Of particular interest in our study is the significant impact of domestic and sexual violence on smoking behaviour. Finally, regarding feasible preventive actions in Guinea-Bissau, our findings show that the government and general populace need to do much preventive work. Children and young people should be engaged in such activities coupled with enforcement of the FCTC. These interventions need to be gender-sensitive in schools and other settings popular among the young populace with the overall aim of reducing lifetime experience of smoking and the future burden and deaths from NCD as part of a national strategy to achieve SDG 3.4.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, G.G., A.B., Z.J., H.B. and J.E.; Data curation, G.G.; Formal analysis, G.G.; Funding acquisition, G.G. and J.E.; Investigation, G.G, A.B., Z.J., H.B. and J.E.; Methodology, G.G., A.B., Z.J., H.B. and J.E.; Project administration, G.G., A.B., Z.J., H.B. and J.E.; Resources, G.G. and J.E.; Supervision, G.G. and J.E.; Validation, G.G. and J.E.; Writing—original draft, G.G.; Writing—review and editing, G.G., A.B., Z.J., H.B. and J.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The implementation of the survey received minor funding from The Research Fund of the University of Iceland and the School of Social Sciences, the University of Iceland, the Icelandic Centre for Social Research and Analysis (ICSRA), and Erasmus+ staff mobility grants.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ministry of Education in Guinea-Bissau (No/Ref 250/MEES/GM/2017). The date of approval was 6 June 2017.

Informed Consent Statement

Due to the students’ mature age as children (aged 14–19) and the study’s setting, pre-parental approval was not sought; the adolescents decided on their participation in the survey without any personal identifiers.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The research is a collaborative effort of many. We are grateful to the students, teachers and headteachers in the participating schools; the Minister of Education, who gave the authorisation to conduct the study; Dr João Ribeiro Butiam Có, who contributed to the translation and preparation of the questionnaire and facilitated the creation of the research group; Professor Inga Dóra Sigfúsdóttir, Assistant Professor Álfgeir Logi Kristjánsson, Hrefna Pálsdóttir and Director Jón Sigfússon of ICSRA for the support for electronic data transformation of questionnaires for data analysis, and encouragement to implement the survey under the umbrella of Planet Youth; Stefán Þór Gunnarsson for statistical advice; and Thomas Andrew Whitehead who assisted with literature review on smoking tobacco.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- GBD 2019 Tobacco Collaborators. Spatial, Temporal, and Demographic Patterns in Prevalence of Smoking Tobacco Use and Attributable Disease Burden in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2019: A Systematic Analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 2021, 397, 2337–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Global Report on Trends in Prevalence of Tobacco Smoking 2000-2025, 2nd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2018; ISBN 978-92-4-151417-0. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Aravkin, A.Y.; Zheng, P.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; Abdollahi, M.; Abdollahpour, I.; et al. Global Burden of 87 Risk Factors in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 2020, 396, 1223–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcavi, L.; Benowitz, N.L. Cigarette Smoking and Infection. Arch. Intern. Med. 2004, 164, 2206–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjartveit, K.; Tverdal, A. Health Consequences of Smoking 1–4 Cigarettes per Day. Tob. Control 2005, 14, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue-Choi, M.; Christensen, C.H.; Rostron, B.L.; Cosgrove, C.M.; Reyes-Guzman, C.; Apelberg, B.; Freedman, N.D. Dose-Response Association of Low-Intensity and Nondaily Smoking with Mortality in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e206436–e206436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2021. Addressing New and Emerging Products; World Health Organization, Geneva: World Health Organization. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.: Geneva, 2021; p. 212. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, J.D.; Liu, B.; Parascandola, M. Smoking and HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa: A 25-Country Analysis of the Demographic Health Surveys. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2018, 21, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, J.E.; Kontis, V.; Mathers, C.D.; Guillot, M.; Rehm, J.; Chalkidou, K.; Kengne, A.P.; Carrillo-Larco, R.M.; Bawah, A.A.; Dain, K.; et al. NCD Countdown 2030: Pathways to Achieving Sustainable Development Goal Target 3.4. The Lancet 2020, 396, 918–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; World Health Organisation: Geneva, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Egbe, C.O.; Magati, P.; Wanyonyi, E.; Sessou, L.; Owusu-Dabo, E.; Ayo-Yusuf, O.A. Landscape of Tobacco Control in Sub-Saharan Africa. Tob. Control 2022, 31, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ane, M. Evaluation of the New ECOWAS Directive on Tobacco Taxation. Res. Sq. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2023: Country Profile Guinea-Bissau; World Health Organization, 2023.

- WHO. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2023: Protect People from Tobacco Smoke; World Health Organization, 2023.

- Aienobe-Asekharen, C.; Norris, E.; Martin, W. A Scoping Review of Tobacco Control Health Communication in Africa: Moving towards Involving Young People. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2024, 21, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreeramareddy, C.T.; Pradhan, P.M.; Sin, S. Prevalence, Distribution, and Social Determinants of Tobacco Use in 30 Sub-Saharan African Countries. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Xi, B.; Li, Z.; Wu, H.; Zhao, M.; Liang, Y.; Bovet, P. Prevalence and Trends in Tobacco Use among Adolescents Aged 13–15 Years in 143 Countries, 1999–2018: Findings from the Global Youth Tobacco Surveys. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2021, 5, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudatsikira, E.; Abdo, A.; Muula, A.S. Prevalence and Determinants of Adolescent Tobacco Smoking in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2007, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veeranki, S.P.; John, R.M.; Ibrahim, A.; Pillendla, D.; Thrasher, J.F.; Owusu, D.; Ouma, A.E.O.; Mamudu, H.M. Age of Smoking Initiation among Adolescents in Africa. Int. J. Public Health 2017, 62, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chido-Amajuoyi, O.G.; Fueta, P.; Mantey, D. Age at Smoking Initiation and Prevalence of Cigarette Use Among Youths in Sub-Saharan Africa, 2014-2017. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e218060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.A.; Palipudi, K.M.; English, L.M.; Ramanandraibe, N.; Asma, S.; Group, G.C. Second-hand Smoke Exposure and Susceptibility to Initiating Cigarette Smoking among Never-Smoking Students in Selected African Countries: Findings from the Global Youth Tobacco Survey. Prev. Med. 2016, 91, S2–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tezera, N.; Endalamaw, A. Current Cigarette Smoking and Its Predictors among School-Going Adolescents in East Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Pediatr. 2019, 2019, 4769820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministério da Economia, do Plano e Integração Regional; UNICEF. Inquérito aos Indicadores Múltiplos 2018-2019 [Monitoring of the Situation of Women and Children. 2018-19 MICS Survey Findings Report Guinea-Bissau].; Ministério da Economia, do Plano e Integração Regional and Unicef: Bissau, 2020; p. 859. [Google Scholar]

- Global Youth Tobacco Survey. Guinée-Bissau (Bissau) (Ages 13-15). Fact Sheet; Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS); World Health Organization: Geneva, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kristjansson, A.L.; Mann, M.J.; Sigfusson, J.; Thorisdottir, I.E.; Allegrante, J.P.; Sigfusdottir, I.D. Development and Guiding Principles of the Icelandic Model for Preventing Adolescent Substance Use. Health Promot. Pract. 2020, 21, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigfúsdóttir, I.D.; Thorlindsson, T.; Kristjánsson, A.L.; Roe, K.M.; Allegrante, J.P. Substance Use Prevention for Adolescents: The Icelandic Model. Health Promot. Int. 2009, 24, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristjansson, A.L.; Sigfusdottir, I.D.; Thorlindsson, T.; Mann, M.J.; Sigfusson, J.; Allegrante, J.P. Population Trends in Smoking, Alcohol Use and Primary Prevention Variables among Adolescents in Iceland, 1997–2014. Addiction 2016, 111, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, H.; McCulloch, P.; Parkes, T. How Might the ‘Icelandic Model’ for Preventing Substance Use among Young People Be Developed and Adapted for Use in Scotland? Utilising the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research in a Qualitative Exploratory Study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyers, C.C.A.; Mann, M.J.; Thorisdottir, I.E.; Ros Garcia, P.; Sigfusson, J.; Sigfusdottir, I.D.; Kristjansson, A.L. Preliminary Impact of the Adoption of the Icelandic Prevention Model in Tarragona City, 2015–2019: A Repeated Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinner, L.; Kelly, C.; Caldwell, D.; Campbell, R. Community Mobilisation Approaches to Preventing Adolescent Multiple Risk Behaviour: A Realist Review. Syst. Rev. 2024, 13, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremichael, M.; Mesfin, E.; Kidane, A. Guinea Bissau Conflict Insight; Institute for Peace and Security Studies, Addis Ababa University: Addis Ababa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Einarsdóttir, J. Partnership and Post-War Guinea-Bissau. Afr. J. Int. Aff. 2007, 10, 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- Mendy, P.K. Portugal’s Civilizing Mission in Colonial Guinea-Bissau: Rhetoric and Reality. Int. J. Afr. Hist. Stud. 2003, 36, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaló, S. Guinea-Bissau: 30 Years of Militarized Democratization (1991–2021). Front. Polit. Sci. 2023, 5, 1078771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M. Drug Trafficking in Guinea-Bissau, 1998–2014: The Evolution of an Elite Protection Network. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 2015, 53, 339–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M.; Gomes, A. Breaking the Vicious Cycle; Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime: Geneva, 2020; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP Human Development Report 2021/22. Uncertain Times, Unsettled Lives. Shaping Our Future in a Transforming World. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2021-22 (accessed on 2 July 2023).

- Merchant, C.M.; Demas, A.; Gardner, E.E.; Khan, M.M. Guinea-Bissau School Autonomy and Accountability: SABER Country Report 2017; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, 2017; p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- UNFPA. State of World Population 2020. Defying the Practices That Harm Women and Girls and Undermine Equality; United Nations Population Fund, 2020.

- da Costa, M.; da Silva, B.V.; Vieira, R.; Manafá, B.; Samedo, S.; Gomes, L. Terceiro recenseamento geral da população e habitação da população de 2009; Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE): Bissau, Guinea-Bissau, 2009; p. 115. [Google Scholar]

- Pariona, A. What Languages Are Spoken In Guinea-Bissau? Available online: https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/what-languages-are-spoken-in-guinea-bissau.html (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- UNESCO. Global Education Monitoring Report 2017/18. Accountability in Education: Meeting Our Commitments; UNESCO: Paris, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. World Inequality Database on Education (WIDE). Available online: https://www.education-inequalities.org/ (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- UNICEF. UNICEF Annual Report 2017. Republic of Guinea-Bissau; UNICEF, 2017.

- Gunnlaugsson, G.; Baboudóttir, F.N.; Baldé, A.; Jandi, Z.; Boiro, H.; Einarsdóttir, J. Public or Private School? Determinants for Enrolment of Adolescents in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 109, 101851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESPAD Purpose & Methodology. Available online: http://www.espad.org/purpose-methodology (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- Spotlight on Adolescent Health and Wellbeing. Findings from the 2017/2018 Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Survey in Europe and Canada International Report. Volume 1. Key Findings; Inchley, J., Currie, D., Budisavljevic, S., Torsheim, T., Jåstad, A., Cosma, A., Kelly, C., Arnarsson, Á.M., Eds.; WHO Regional Office for Europe. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.: Copenhagen, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- NIH Monitoring the Future. Available online: https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/trends-statistics/monitoring-future (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- Planet Youth Planet Youth. Available online: https://planetyouth.org/the-method/data-center/ (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- Kristjansson, A.L.; Mann, M.J.; Sigfusson, J.; Thorisdottir, I.E.; Allegrante, J.P.; Sigfusdottir, I.D. Implementing the Icelandic Model for Preventing Adolescent Substance Use. Health Promot. Pract. 2020, 21, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristjansson, A.L.; Sigfusson, J.; Sigfusdottir, I.D.; Allegrante, J.P. Data Collection Procedures for School-Based Surveys Among Adolescents: The Youth in Europe Study. J. Sch. Health 2013, 83, 662–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnlaugsson, G.; Baldé, A.; Boiro, H.; Butiam Có, J.R.; Einarsdóttir, J.; on behalf of Planet Youth Collaboration. Saúde e bem-estar da juventude em Bissau, Guiné-Bissau. Relatório do inquérito realizado em junho 2017 [Health and wellbeing of adolescents in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau. Report on a survey conducted in June 2017]; the University of Iceland, Jean Piaget University Guinea-Bissau, Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisa (INEP) and Icelandic Centre for Social Research and Analysis (ICSRA): Reykjavík and Bissau, 2018; 70p. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. JMP Pro 16. Predictive Analytics Software for Scientists and Engineers. Available online: https://www.jmp.com/en_gb/software/predictive-analytics-software.html (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Sall, J. Scaling-up Process Characterization. Qual. Eng. 2018, 30, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Convention on the Rights of the Child; 1990.

- Anderman, C.; Cheadle, A.; Curry, S.; Diehr, P.; Shultz, L.; Wagner, E. Selection Bias Related to Parental Consent in School-Based Survey Research. Eval. Rev. 1995, 19, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cox, R.B.; Washburn, I.J.; Croff, J.M.; Crethar, H.C. The Effects of Requiring Parental Consent for Research on Adolescents’ Risk Behaviors: A Meta-Analysis. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 61, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abebe, T.; Bessell, S. Advancing Ethical Research with Children: Critical Reflections on Ethical Guidelines. Child. Geogr. 2014, 12, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okyere, S. ‘Like the Stranger at a Funeral Who Cries More than the Bereaved’: Ethical Dilemmas in Ethnographic Research with Children: Qual. Res. 2018, 18, 623–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsdóttir, J.; Baldé, A.; Jandi, Z.; Boiro, H.; Gunnlaugsson, G. Prevalence of and Influential Factors for Waterpipe Smoking among School-Attending Adolescents in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau. Adolescents 2024, 4, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afifi, R.; Khalil, J.; Fouad, F.; Hammal, F.; Jarallah, Y.; Farhat, H.A.; Ayad, M.; Nakkash, R. Social Norms and Attitudes Linked to Waterpipe Use in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 98, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maziak, W. The Global Epidemic of Waterpipe Smoking. Addict. Behav. 2011, 36, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollom, J.E.; Baldé, A.; Jandi, Z.; Boiro, H.; Einarsdóttir, J.; Gunnlaugsson, G. Social Determinants of Narcotics Use Susceptibility among School-Attending Adolescents in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Adolescents 2021, 1, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General; Reports of the Surgeon General; National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US): Atlanta (GA), 2012. [Google Scholar]

- HBSC. HBSC Data Visualisations: Tobacco Use. Available online: https://hbsc.org/data/ (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- Mills, R.; Mann, M.J.; Smith, M.L.; Kristjansson, A.L. Parental Support and Monitoring as Associated with Adolescent Alcohol and Tobacco Use by Gender and Age. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollom, J.E.; Baldé, A.; Jandi, Z.; Boiro, H.; Gunnlaugsson, G.; Einarsdóttir, J. Equality of Opportunity: Social Determinants of University Expectation amongst School Attending Adolescents in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 117, 102129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenbach, J.P.; Stirbu, I.; Roskam, A.-J.R.; Schaap, M.M.; Menvielle, G.; Leinsalu, M.; Kunst, A.E. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health in 22 European Countries. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathmann, K.; Moor, I.; Kunst, A.E.; Dragano, N.; Pförtner, T.-K.; Elgar, F.J.; Hurrelmann, K.; Kannas, L.; Baška, T.; Richter, M. Is Educational Differentiation Associated with Smoking and Smoking Inequalities in Adolescence? A Multilevel Analysis across 27 European and North American Countries. Sociol. Health Illn. 2016, 38, 1005–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.; Arnott, R. Substance Use among Rural Secondary Schools in Zimbabwe: Patterns and Prevalence. Cent. Afr. J. Med. 1996, 42, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gunnlaugsson, G.; Whitehead, T.A.; Baboudóttir, F.N.; Baldé, A.; Jandi, Z.; Boiro, H.; Einarsdóttir, J. Use of Digital Technology among Adolescents Attending Schools in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 8937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristman-Valente, A.N.; Brown, E.C.; Herrenkohl, T.I. Child Physical and Sexual Abuse and Cigarette Smoking in Adolescence and Adulthood. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 53, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, J.A.; Wang, W.; Testa, M.; Derrick, J.L.; Nickerson, A.B.; Miller, K.E.; Haas, J.L.; Espelage, D.L. Peer Sexual Harassment, Affect, and Substance Use: Daily Level Associations among Adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2022, 94, 955–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gujarati, D.N.; Porter, D.C. Basic Econometrics, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill Irwin: Boston, 2009; ISBN 978-0-07-337577-9. [Google Scholar]

- Batini, C.; Ahmed, T.; Ameer, S.; Kilonzo, G.; Ozoh, O.B.; van Zyl-Smit, R.N. Smoking Cessation on the African Continent: Challenges and Opportunities. Afr. J. Thorac. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bafunno, D.; Catino, A.; Lamorgese, V.; Del Bene, G.; Longo, V.; Montrone, M.; Pesola, F.; Pizzutilo, P.; Cassiano, S.; Mastrandrea, A. Impact of Tobacco Control Interventions on Smoking Initiation, Cessation, and Prevalence: A Systematic Review. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebirim, C.I.C.; Amadi, A.N.; Abanobi, O.C.; Iloh, G.U.P. The Prevalence of Cigarette Smoking and Knowledge of Its Health Implications among Adolescents in Owerri, South-Eastern Nigeria. Health (N. Y.) 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, P.; Leyton, A.; Meekers, D.; Stoecker, C.; Wood, F.; Murray, J.; Dodoo, N.D.; Biney, A. Evaluation of a Multimedia Youth Anti-Smoking and Girls’ Empowerment Campaign: SKY Girls Ghana. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, G.E.; Prokhorov, A.V. Friendship Influence Moderating the Effect of a Web-Based Smoking Prevention Program on Intention to Smoke and Knowledge among Adolescents. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2021, 13, 100335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakkash, R.; Lotfi, T.; Bteddini, D.; Haddad, P.; Najm, H.; Jbara, L.; Alaouie, H.; Al Aridi, L.; Al Mulla, A.; Mahfoud, Z. A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Theory-Informed School-Based Intervention to Prevent Waterpipe Tobacco Smoking: Changes in Knowledge, Attitude, and Behaviors in 6th and 7th Graders in Lebanon. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2018, 15, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, S.C.; Donnelly, M.; Bhatnagar, P.; Carlin, A.; Kee, F.; Hunter, R.F. Peer Social Network Processes and Adolescent Health Behaviors: A Systematic Review. Prev. Med. 2020, 130, 105900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isip, U.; Calvert, J. Analysing Big Tobacco’s Global Youth Marketing Strategies and Factors Influencing Smoking Initiation by Nigeria Youths Using the Theory of Triadic Influence. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chido-Amajuoyi, O.G.; Mantey, D.S.; Clendennen, S.L.; Pérez, A. Association of Tobacco Advertising, Promotion and Sponsorship (TAPS) Exposure and Cigarette Use among Nigerian Adolescents: Implications for Current Practices, Products and Policies. BMJ Glob. Health 2017, 2, e000357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Ling, P.M.; Glantz, S.A. The Vector of the Tobacco Epidemic: Tobacco Industry Practices in Low and Middle-Income Countries. Cancer Causes Control 2012, 23, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, P.; Okechukwu, C.A.; Collin, J.; Hughes, B. Bringing ‘Light, Life and Happiness’: British American Tobacco and Music Sponsorship in Sub-Saharan Africa. Third World Q. 2009, 30, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owusu-Dabo, E.; Lewis, S.; McNeill, A.; Anderson, S.; Gilmore, A.; Britton, J. Smoking in Ghana: A Review of Tobacco Industry Activity. Tob. Control 2009, 18, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madkour, A.S.; Ledford, E.C.; Andersen, L.; Johnson, C.C. Tobacco Advertising/Promotions and Adolescents’ Smoking Risk in Northern Africa. Tob. Control 2013, 23, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaie, J.; Ahmadi, A.; Abdollahi, G.; Doshmangir, L. Preventing and Controlling Water Pipe Smoking: A Systematic Review of Management Interventions. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filby, S.; van Walbeek, C. Cigarette Prices and Smoking Among Youth in 16 African Countries: Evidence From the Global Youth Tobacco Survey. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2022, 24, 1218–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).