Introduction

The chicken business is one of the world’s largest and fastest expanding agro-based productions; demand for eggs and meat grows year after year due to its high energy and protein content. Phosphorus (P) is the third most expensive component of poultry feed and an essential macro-mineral required to mediate major metabolic pathways in the body. It also serves a variety of functions such as bone development, skeletal mineralization, regulation of key enzymes in metabolism, and several genomic and physiological processes (Abbasi et al., 2019). Previously, it was assumed that just 30% of the P in plants was available to birds. The main components of poultry diets are plant-based feedstuffs. However, most plant-based meals contain anti-nutritional elements like as phytic acid.

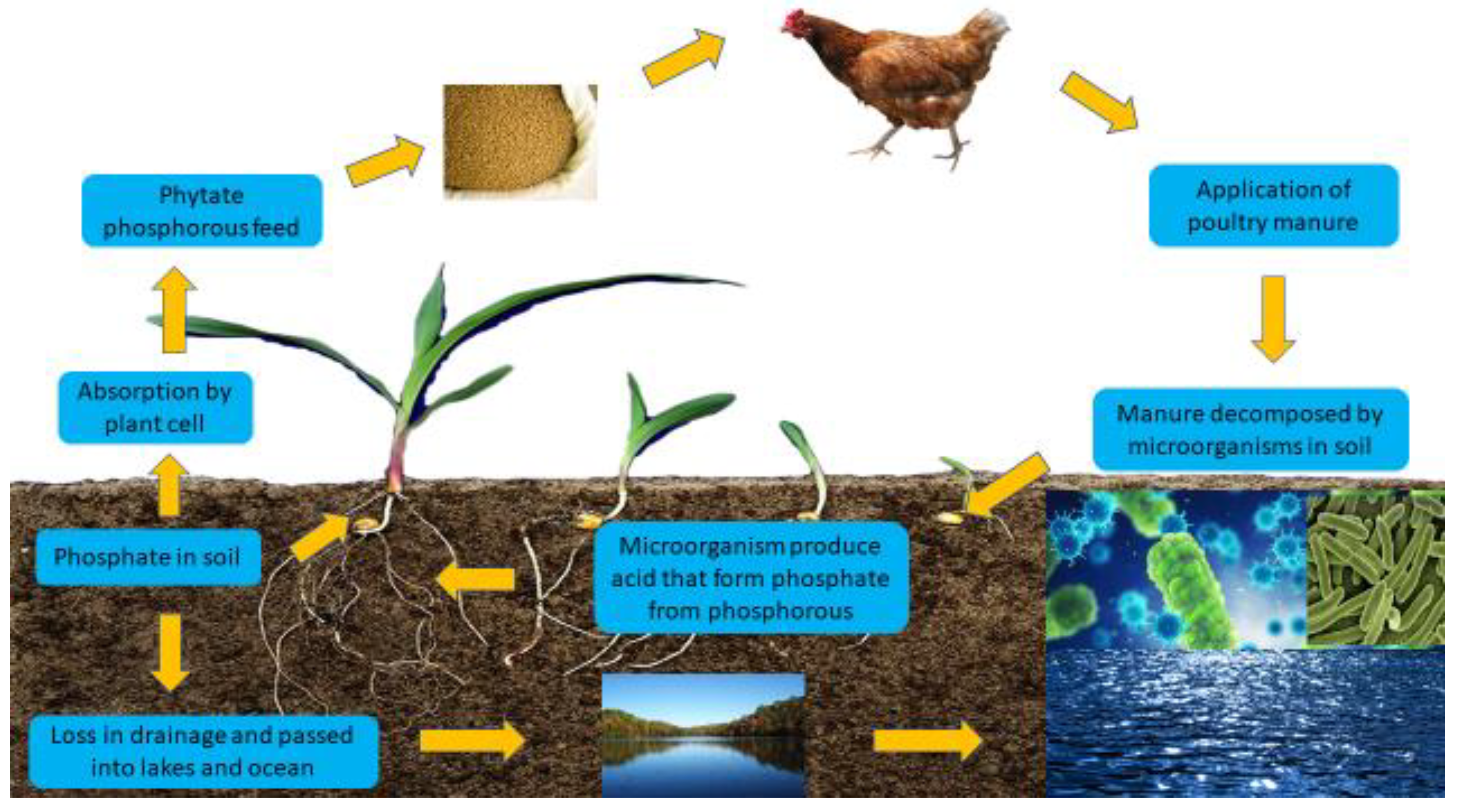

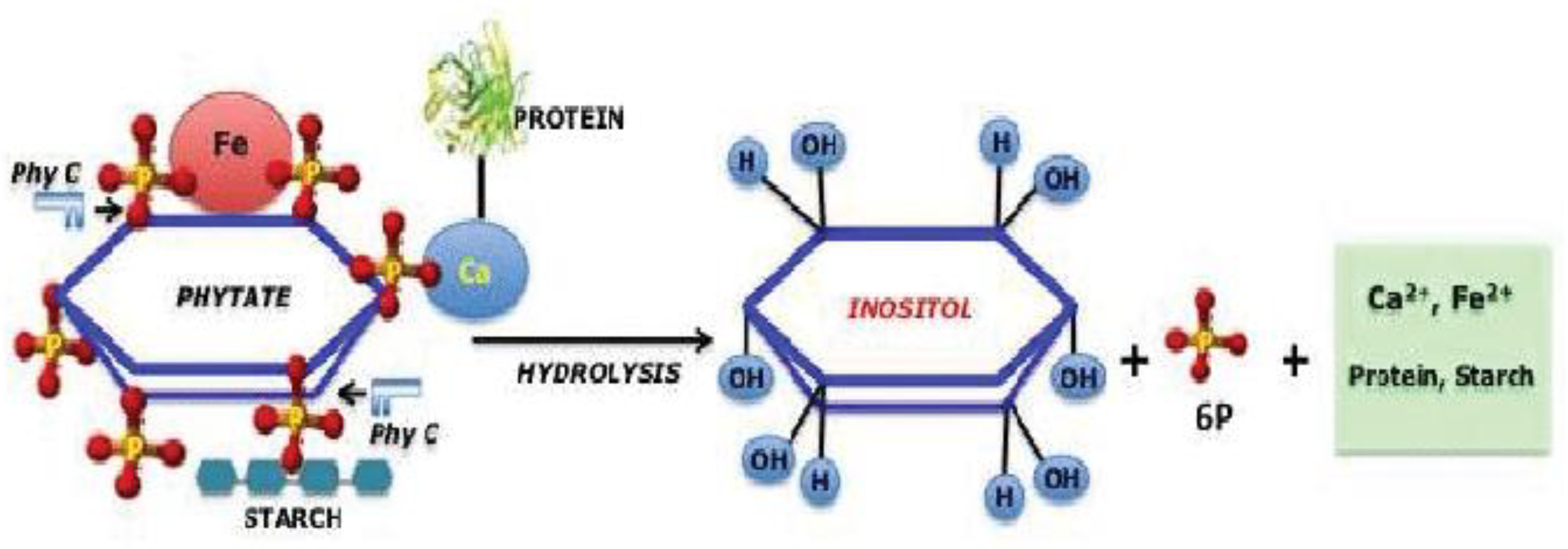

Phytic acid is the primary source of bound or inaccessible phosphorus in plants, particularly seeds, grains, and vegetables. Phytic acid (C6H18O24P6), also known as myo-inositol 1,2,3,4,5,6-hexakisphosphate (PA or IP6), has a molecular weight of 660 g mol−1. The six reactive P groups in PA chelate positive cations such as Fe, Ca, and Zn, all of which are essential micronutrients for human and animal growth and function. PA is classified as an anti-nutritional factor due to its capacity to chelate critical micronutrients and store P, making P unavailable. Despite its presence in soil, PA is either inaccessible for breakdown by soil microorganisms or is significantly less bioavailable (Gupta, Gangoliya, Singh, & technology, 2015). Ruminants can utilize PA, whereas humans and other monogastric animals have limited ability to hydrolyze phytate. As a result, PA lowers P bioavailability while also chelating minerals and micronutrients necessary for cellular metabolism, maintenance, and tissue function.5 Pigs and poultry lack phytase, therefore their gastrointestinal tracts are unable to metabolise PA, which has two major deleterious consequences. First and foremost, these animals are unable to adequately absorb PA (Urbano et al., 2000). Second, the release of unabsorbed inorganic P to the environment causes difficulties such as eutrophication of water bodies and the creation of greenhouse gases such as nitrous.

The environmental impact of phytate, a common organic phosphorus molecule, is enormous. It can provide nutrients for algal blooms in lakes, thereby aggravating eutrophication. Phytate’s stability in complexation with metal ions can impede enzymatic hydrolysis, influencing its destiny in agricultural soils (Zhou, Erdman Jr, & Nutrition, 1995). Thus, biotechnological and microbiological methods must be used to improve the quality and bioavailability of P in animal feed while lowering the PA level.

Figure 1.

Cycle of phytic acid.

Figure 1.

Cycle of phytic acid.

Digestion and Utilization Problems

Nutritional management strives to improve or sustain production performance (Abbasi et al. 2014) while reducing pollution load in soil, water, and air, boosting feed efficiency and poultry health to lower the environmental pollution burden (Nahm 2002). Monogastric poultry birds are unable to use the phytate P of plant feedstuffs because a large amount of P is present in the form of phytate, which chickens only partially digest (Dozier et al. 2015; Abbasi et al., 2018a, b). The ability of chickens to use phytate P is an issue of debate (Marounek et al. 2008); the low digestibility of phytate P means that the inorganic phosphate (defluorinated), calcium phosphate (monobasic and dibasic form), sodium phosphate (monobasic and dibasic), magnesium phosphate, potassium phosphate, and phosphate rock are often added to meet the requirements. Camden et al. (2001). Phosphorus is present in plants in 50 to 70% concentrations and is decomposed in a stepwise way, producing numerous intermediate products and free phosphates (Kemme et al. 2006). To reduce phytate P low availability in the diet, inorganic sources of P and exogenous phytase were supplemented, whereas dietary non-phytate phosphorus (NPP) was decreased in combination with additional phytase, resulting in a 29 to 45% reduction in P excreta (Angel et al. 2006). Furthermore, the feed ingredients contain phytase in intrinsic phytases, which can affect phytate breakdown and utilisation in poultry. Phytase supplementation with corn-soy diets, on the other hand, increases P digestibility by 10 to 24% (Rutherfurd et al. 2002), and microbial phytase supplementation with corn-soy diets significantly enhances phytate P utilisation (Lei et al. 1994). Furthermore, the introduction of phytase in the diet was found to diminish water-soluble phosphorus absorption in excreta (McGrath et al. 2005). Furthermore, various studies have shown that reducing total P excreta in poultry improves phosphorus utilisation (Rutherfurd et al. 2002). To promote P utilisation and reduce P excretion in manure, phytase inclusion in diet can minimise environmental pollution and feed expense because P is the most expensive ingredient of chicken feed and excess manure P application in land might produce P runoff and infect the surface and groundwater (Dankowiakowska et al. 2013).

Effect on Nutrient Uptake and Micronutrient Digestibility

Hidden hunger is a type of undernutrition that arises when the intake and absorption of vitamins and minerals are insufficient to support healthy health and development. One example is when malnutrition overlaps with obesity.11 A person may not be famished due to a lack of calories, but rather a lack of critical micronutrients. Hidden hunger is mostly concerned with dietary inadequacies of key food components such as vitamin A, zinc, iron, and iodine. I, Fe, and Zn are the most frequent micronutrient deficits at all ages. Pregnant women and children under the age of five are particularly vulnerable to concealed hunger, which worsens their health throughout their lives and raises their mortality rate.

Fe, Ca, and Zinc are critical minerals for pregnant women. However, pregnant women in underdeveloped countries are frequently lacking in these micronutrients since staple crops and plant-based diets provide the majority of their nutritional energy. Because the foods ingested are often high in PA, the bioavailability of critical micronutrients is lowered by PA acting as an inhibitor or chelating agent.

Zinc:

Human zinc insufficiency occurs worldwide, however it is more common in areas where the diet is plant- or cereal-based and less animal-based goods are consumed. PA is the primary dietary component that reduces Zn bioavailability by inhibiting absorption in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) (Hambidge, Miller, Krebs, & research, 2011). The availability of zinc for GIT absorption is determined by the combined influence of PA, proteins, and other mineral ions in the body. Under certain conditions, increasing the dose of Fe reduces Zn absorption significantly (Lönnerdal, 2000). This inhibitory impact only occurs when a high Fe to Zn ratio is delivered apart from meals, but protein in the diet increases Zn absorption by the GIT. Zn absorption is primarily impeded by the presence of PA when the phytate:Zn molar ratio is 18:1. According to the World Health Organisation, the ideal molar ratio of phytate to zinc is 15:1.(Ma et al., 2007) However, Davidsson et al. found that Fe has no deleterious effect on Zn absorption (Davidson, Almgren, Sandström, & Hurrell, 1995). Because of its high density of negatively charged phosphate groups, PA forms insoluble salts containing positively charged divalent cations. Allen et al. discovered that the presence of Ca ions reduces Zn bioavailability by producing insoluble Ca-Zn-PA complexes. To boost Zn bioavailability, the diet’s Zn concentration must be raised while reducing the quantity of absorption inhibitors such as PA (FORTIFICATION; Hunt & Beiseigel, 2009).

Iron:

PA, because to its numerous negative charges, quickly complexes with Fe, rendering it ineffective for absorption.(Abbaspour, Hurrell, & Kelishadi, 2014) Fe deficiency occurs when there is no free or mobilizable Fe available for absorption by the body, which can result in either anaemia or nonanaemia. Non-haem Fe and PA levels are inversely linked. Notably, excessive Fe consumption but nonabsorption increases the risk of colon cancer, as unabsorbed Fe in the intestine causes GIT illness (Lopez, Leenhardt, Coudray, Remesy, & technology, 2002). Fe deficiency in pregnant women raises the risk of sepsis, maternal or perinatal death, and morbidity. In youngsters under the age of five, Fe deficiency impairs learning ability. Infants, teenagers, and pregnant women are especially vulnerable to iron deficiency.

Calcium:

Calcium shortage in the diet can cause bone loss and weakness, leading to osteoporosis in adults and rickets in children under 5. Bone formation requires approximately 99% of the total calcium consumed. Although dairy products are the primary source of calcium in the diet, other foods also contribute to total Ca intake. Those adopting a vegan diet or living in underdeveloped nations must consume an adequate number of non-dairy sources of calcium, such as cereals and legumes, to meet their calcium requirements. In humans, PA and Ca absorption have opposite effects: PA reduces Ca absorption, while PA degradation increases Ca availability, mostly through the production of insoluble Ca phytate complexes. Furthermore, consuming Ca with phytate rich food is recommended, as the consumption of a diet rich in Ca but deficient in whole goods such as bran may cause kidney stones and crystallisation inhibition (Grases, Prieto, Simonet, & March, 2000).

Protein:

PA, like divalent cations, is capable of chelating proteins. Human and animal nutritionists have noticed that when PA levels are high, both amino acids and P are used less efficiently. PA, a polyanionic molecule capable of transporting up to twelve dissociable protons, produces binary protein-phytate complexes. For negatively charged proteins, phytate is linked to the protein via a cationic bridge (typically calcium)(Selle, Cowieson, Cowieson, & Ravindran, 2012) Furthermore, phytate can interact with proteins as a Hofmeister anion, or kosmotrope. The Hofmeister or lyotropic series classifies cations and anions according to their ability to stabilise or destabilise proteins. Protein solubility can be lowered by stabilising the protein with hydrogen bonds in water (Baldwin, 1996). Alpha amino acids, basic terminal amino acids, the epsilon amino group of lysine, the imidazole group of histidine, and the guanidine group of arginine are all implicated in protein-PA interactions, which rely on the protein’s unimpeded cationic groups binding to PA.

Soil health:

Phytate, a major source of organic phosphorus in soils, can have both good and negative environmental effects. On the one hand, phytate buildup in soils might limit phosphorus availability due to its strong binding capabilities, thus reducing agricultural production and demanding increased phosphate fertilizer use. Microbial phytases, on the other hand, have been identified as potent bioinoculants capable of solubilizing phytate, increasing plant growth and reducing the need for inorganic phosphates, hence improving soil sustainability. Furthermore, phytates can bind important minerals such as calcium, iron, and zinc, reducing their bioavailability and thus compromising soil health and plant nutrition (Liu et al., 2022). Understanding the dynamics of phytate in soil and developing biotechnological solutions to increase its utilization by plants are critical for avoiding environmental concerns and fostering sustainability.

Eutrophication Problem

Eutrophication is a global issue that is expected to worsen in the next decades due to increases in human population, food consumption, land conversion, the use of rich P manure as fertilizer, and the deposition of excessive N. Eutrophication, caused by the growth of undesired algae, typically limits water use for drinking, industrial purposes, and fishery restoration. Excess phosphorus litter inputs, industrial discharges, and runoff agricultural phosphorus to lakes are typically caused by sewage, which is a significant eutrophication source. The input of P into coastal regions has increased, and nutrient accumulation is damaging to the aquatic ecology(Howarth, 2008). Phosphorus from poultry manure in soil and runoff into waterways promotes eutrophication and has an impact on aquatic plant growth. It causes excessive growth, degradation of aquatic plants, and hazardous conditions in aquatic ecosystems (Council & Nutrition, 1994). Phosphorus-rich soils wash into lakes, where some P dissolves and promotes the growth of aquatic plants and phytoplankton.

Myoinositol-Release

Phytate decomposition and myo-inositol release can have a substantial environmental impact. Studies have demonstrated that phytate, a prevalent type of organic phosphorus, can pollute soil and water resources if not digested by nonruminant animals, potentially affecting environmental quality. The breakdown of phytate by phytases can result in the release of myo-inositol and other phosphorus molecules, influencing the bioavailability of nutrients in substrates such as malt and grains for fermentation processes. Furthermore, isotopic methods can be used to follow the distribution of phytate and its degradation products in various sources, providing insights into the pathways and mechanisms behind phytate breakdown in the environment. Understanding these processes is critical for controlling nutrient cycles and preventing eutrophication in ecosystems, emphasiszing the significance of researching phytate decomposition and myo-inositol release for sustainable environmental practices.

The breakdown of phytate produces myo-inositol and phosphorus. While myo-inositol is not toxic, the concomitant increase in bioavailable phosphorus can contribute to the eutrophication issue if not controlled effectively (Sommerfeld et al., 2020).

Figure 2.

Phytate Degradation and Myo-inositol Release.

Figure 2.

Phytate Degradation and Myo-inositol Release.

Ecological Effects

Phytate, a commonly found organic phosphorus molecule in the environment, has a substantial impact on ecological equilibrium. Studies have revealed that phytate can form stable complexes with various metal ions, preventing its hydrolysis by enzymes and influencing its solubility (Li et al., 2022). Furthermore, the presence of phytate can cause eutrophication in water bodies, favouring algal blooms because of its bioavailability as a phosphorus source for algae (Sun, He, & Jaisi, 2021). In agricultural settings, the low digestion of phytate phosphorus in poultry diets can result in excess phosphorus excretion, contributing to environmental pollution and disturbing ecosystems (Zhu et al., 2021). In addition, the saturation of accessible phosphorus binding sites in terrestrial and sediment systems owing to long-term land application of phytate-rich manure might worsen eutrophication through the passage of soluble or particle-associated phosphorus into streams (Abbasi et al., 2019).

Strategies to Reduce PA Content

Various strategies can be applied to enhance the micronutrient content of food, either pre- or postharvest or during food processing.

Biofortification

Crop biofortification is one of the preharvest techniques, and it can be accomplished by a variety of agronomic procedures such as the use of plant growth-promoting microbes, mineral fertilisers, genetic engineering, or plant breeding. These agronomic treatments combine inorganic and organic fertilisers to improve the soil’s micronutrient content or status, resulting in improved plant quality.34 These methods increase soil fertility but do not ensure the solubility or mobility, and thus bioavailability, of specific micronutrients in the edible sections of the plant.35,36 As such, genetic biofortification is the approach used to ensure that minerals are bioavailable for human consumption. Genetic biofortification is the process of developing mineral-rich crops through genetics, including breeding and transgenic techniques.

In this method, cultivars with low PA or antinutrient content and high or improved micronutrient content are chosen for breeding. Because PA levels are adversely connected with the availability of important micronutrients, biofortification has been used to improve cereal crops such as wheat, maize, rice, and pulses by lowering antinutrient levels while increasing mineral profile.

Genetic Engineering and Breeding

Developing crop varieties with reduced phytate content or higher phytase activity can help reduce the quantity of phytate entering the environment via agricultural activities.

Manure Management

Improved manure management strategies, such as precise application time and methods, can help reduce phosphorus runoff. Composting, anaerobic digestion, and the utilisation of artificial wetlands.

Dietary Adjustments

Adjusting animal diets to optimize the balance of phosphorus and employing alternative feed ingredients can help reduce the environmental impact of phytate.

Conclusion

Phytate, a major phosphorus storage molecule in plants, has both positive and negative environmental effects. Positively, it promotes nutrient recycling and soil health by increasing soil organic matter and microbial activity. This promotes sustainable agriculture by minimizing dependency on synthetic phosphorus fertilizers. However, phytate poses an environmental risk, particularly through phosphorus contamination. Undigested phytate in animal dung can cause phosphorus discharge, which contributes to eutrophication and the destruction of aquatic ecosystems. Non-ruminant animals’ inability to digest phytate demands additional phosphorus in their diets, worsening the problem. Mitigation methods are critical for balancing phytate’s benefits and negatives. Phytase enzyme addition in animal feed increases phytate digestibility and reduces phosphorus waste. Additionally, breeding and genetic engineering can develop crops with lower or higher phytase concentration. activity. Improving manure management and dietary changes in animal husbandry can also help to reduce environmental phosphorus contamination.To summarize, while phytate is essential for plant and soil health, its environmental impact requires careful management. Implementing efficient mitigation techniques in agricultural and animal husbandry can leverage the benefits of phytate while limiting its potential environmental hazards, particularly phosphorus pollution.

References

- Abbasi, F.; Fakhur-Un-Nisa, T.; Liu, J.; Luo, X.; Abbasi, I.H.R. Low digestibility of phytate phosphorus, their impacts on the environment, and phytase opportunity in the poultry industry. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 9469–9479. [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour, N.; Hurrell, R.; Kelishadi, R. Review on iron and its importance for human health. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2014, 19, 164–174.

- Baldwin, R. How Hofmeister ion interactions affect protein stability. Biophys. J. 1996, 71, 2056–2063. [CrossRef]

- Council, N. R., & Nutrition, S. o. P. (1994). Nutrient requirements of poultry: 1994: National Academies Press.

- Davidson, L.; Almgren, A.; Sandström, B.; Hurrell, R.F. Zinc absorption in adult humans: the effect of iron fortification. Br. J. Nutr. 1995, 74, 417–425. [CrossRef]

- FORTIFICATION, F. GUIDELINES ON FOOD FORTIFICATION WITH MICRONUTRIENTS.

- Grases, F.; Prieto, R.M.; Simonet, B.M.; March, J.G. Phytate prevents tissue calcifications in female rats. BioFactors 2000, 11, 171–177. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.K.; Gangoliya, S.S.; Singh, N.K. Reduction of phytic acid and enhancement of bioavailable micronutrients in food grains. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 52, 676–684. [CrossRef]

- Hambidge, K.M.; Miller, L.V.; Krebs, N.F. Physiological Requirements for Zinc. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2011, 81, 72–78. [CrossRef]

- Howarth, R.W. Coastal nitrogen pollution: A review of sources and trends globally and regionally. Harmful Algae 2008, 8, 14–20. [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.R.; Beiseigel, J.M. Dietary calcium does not exacerbate phytate inhibition of zinc absorption by women from conventional diets. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 839–843. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, K.; Lin, X.; Li, L.; Lin, S. Phytate as a Phosphorus Nutrient with Impacts on Iron Stress-Related Gene Expression for Phytoplankton: Insights from the Diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e0209721. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Han, R.; Cao, Y.; Turner, B.L.; Ma, L.Q. Enhancing Phytate Availability in Soils and Phytate-P Acquisition by Plants: A Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 9196–9219. [CrossRef]

- Lönnerdal, B. Dietary Factors Influencing Zinc Absorption. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 1378S–1383S. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, H.W.; Leenhardt, F.; Coudray, C.; Remesy, C. Minerals and phytic acid interactions: is it a real problem for human nutrition?. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2002, 37, 727–739. [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Li, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zhai, F.; Kok, F.J.; Yang, X. Phytate intake and molar ratios of phytate to zinc, iron and calcium in the diets of people in China. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 61, 368–374. [CrossRef]

- Selle, P.H.; Cowieson, A.J.; Cowieson, N.P.; Ravindran, V. Protein–phytate interactions in pig and poultry nutrition: a reappraisal. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2012, 25, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Sommerfeld, V.; Huber, K.; Bennewitz, J.; Camarinha-Silva, A.; Hasselmann, M.; Ponsuksili, S.; Seifert, J.; Stefanski, V.; Wimmers, K.; Rodehutscord, M. Phytate degradation, myo-inositol release, and utilization of phosphorus and calcium by two strains of laying hens in five production periods. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 6797–6808. [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; He, Z.; Jaisi, D.P. Role of metal complexation on the solubility and enzymatic hydrolysis of phytate. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0255787. [CrossRef]

- Urbano, G., Lopez-Jurado, M., Aranda, P., Vidal-Valverde, C., Tenorio, E., Porres, J. J. J. o. p., & biochemistry. (2000). The role of phytic acid in legumes: antinutrient or beneficial function? , 56(3), 283-294.

- Zhou, J. R., Erdman Jr, J. W. J. C. R. i. F. S., & Nutrition. (1995). Phytic acid in health and disease. 35(6), 495-508.

- Zhu, Y., Liu, Z., Luo, K., Xie, F., He, Z., Liao, H., . . . Technology. (2021). The adsorption of phytate onto an Fe–Al–La trimetal composite adsorbent: Kinetics, isotherms, mechanism and implication. 7(11), 1971-1984.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).