Submitted:

07 August 2024

Posted:

08 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Details of Computational Methods

2.1. Supercells for Misfit Layer Compound (SnS)1+xNbS2 Approximants

2.2. First-Principles Code and Settings

3. Results

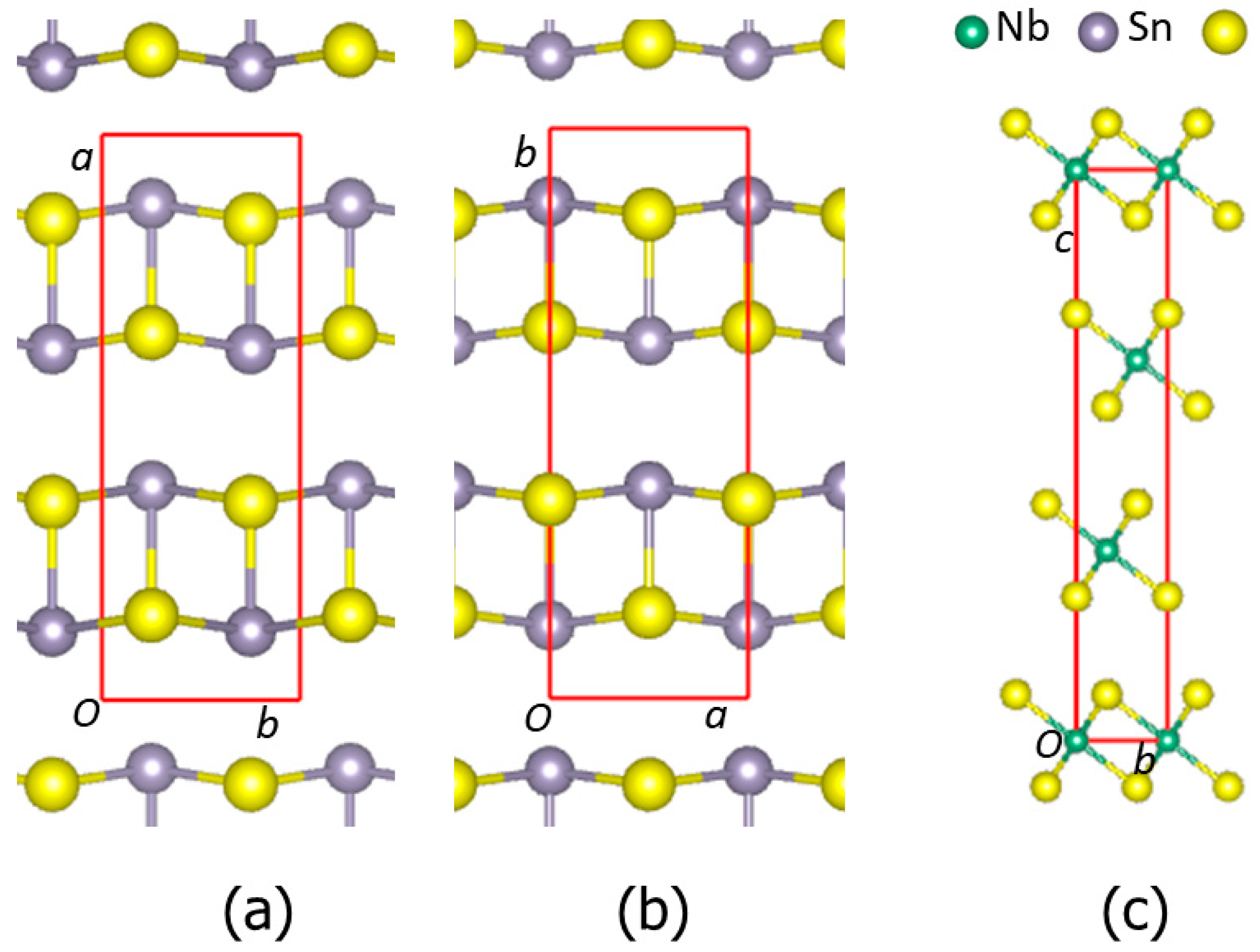

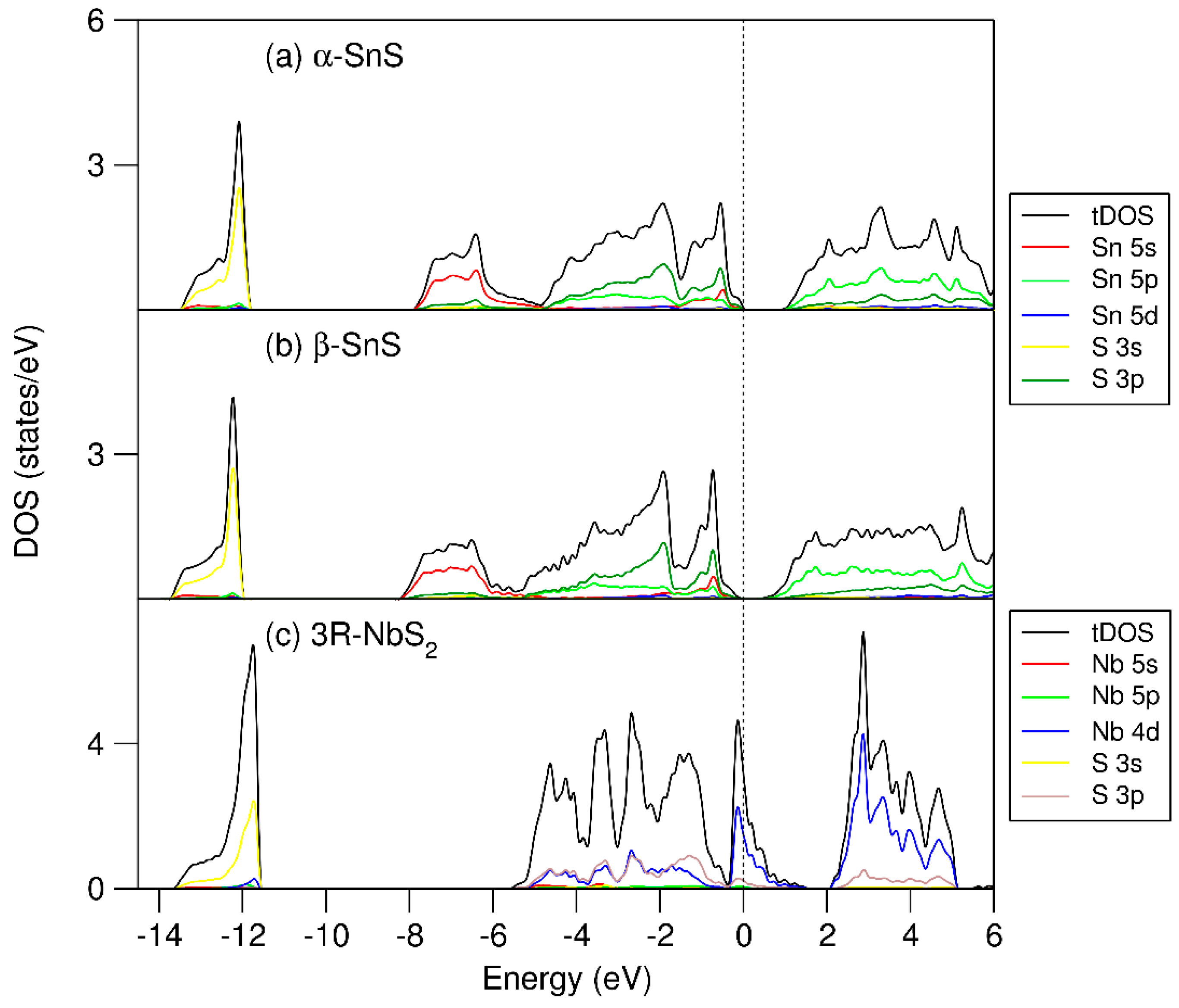

3.1. The Parental SnS and NbS2 Phases

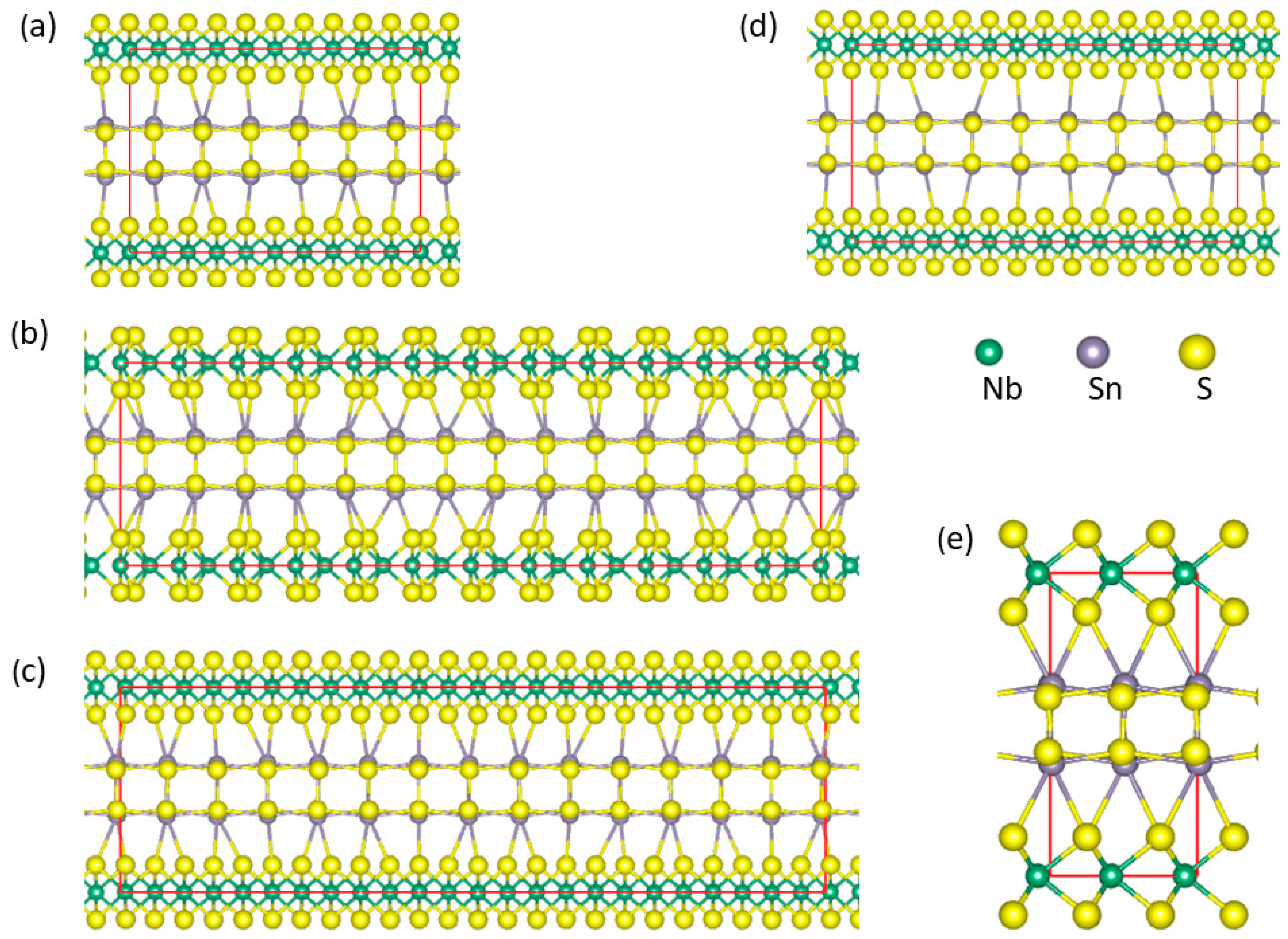

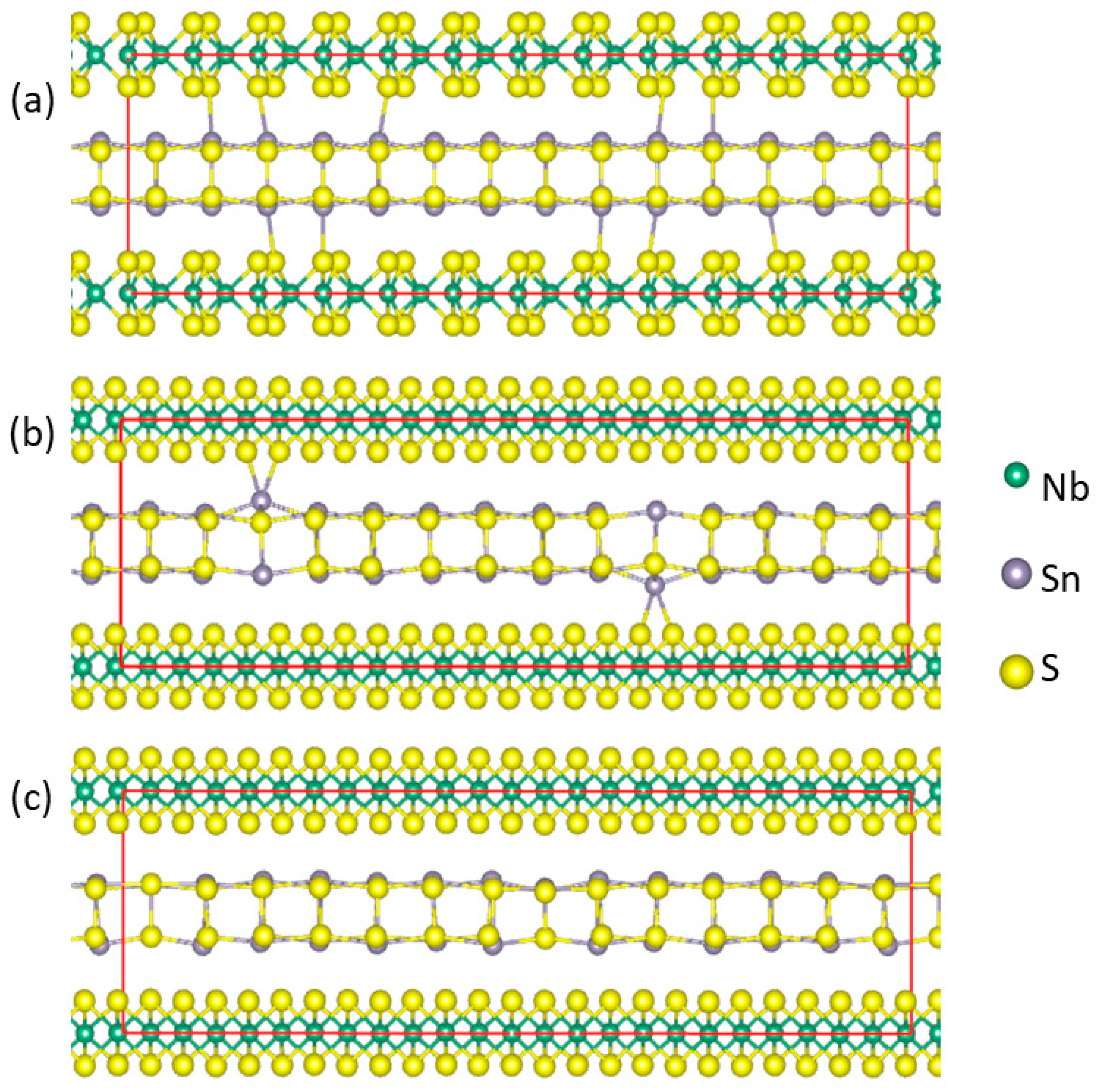

3.2. Stability and Crystal Structure of (SnS)1+xNbS2 Approximants

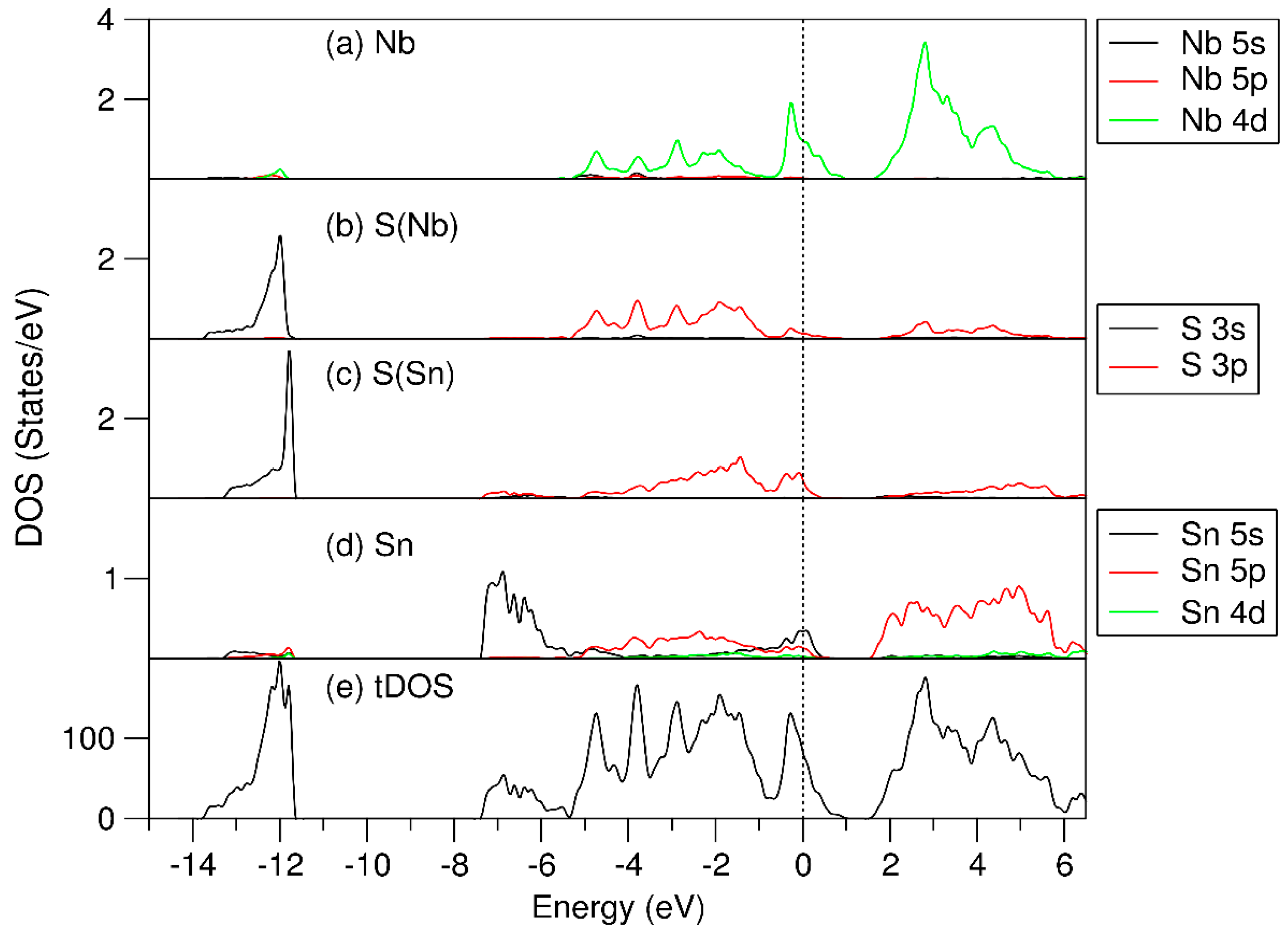

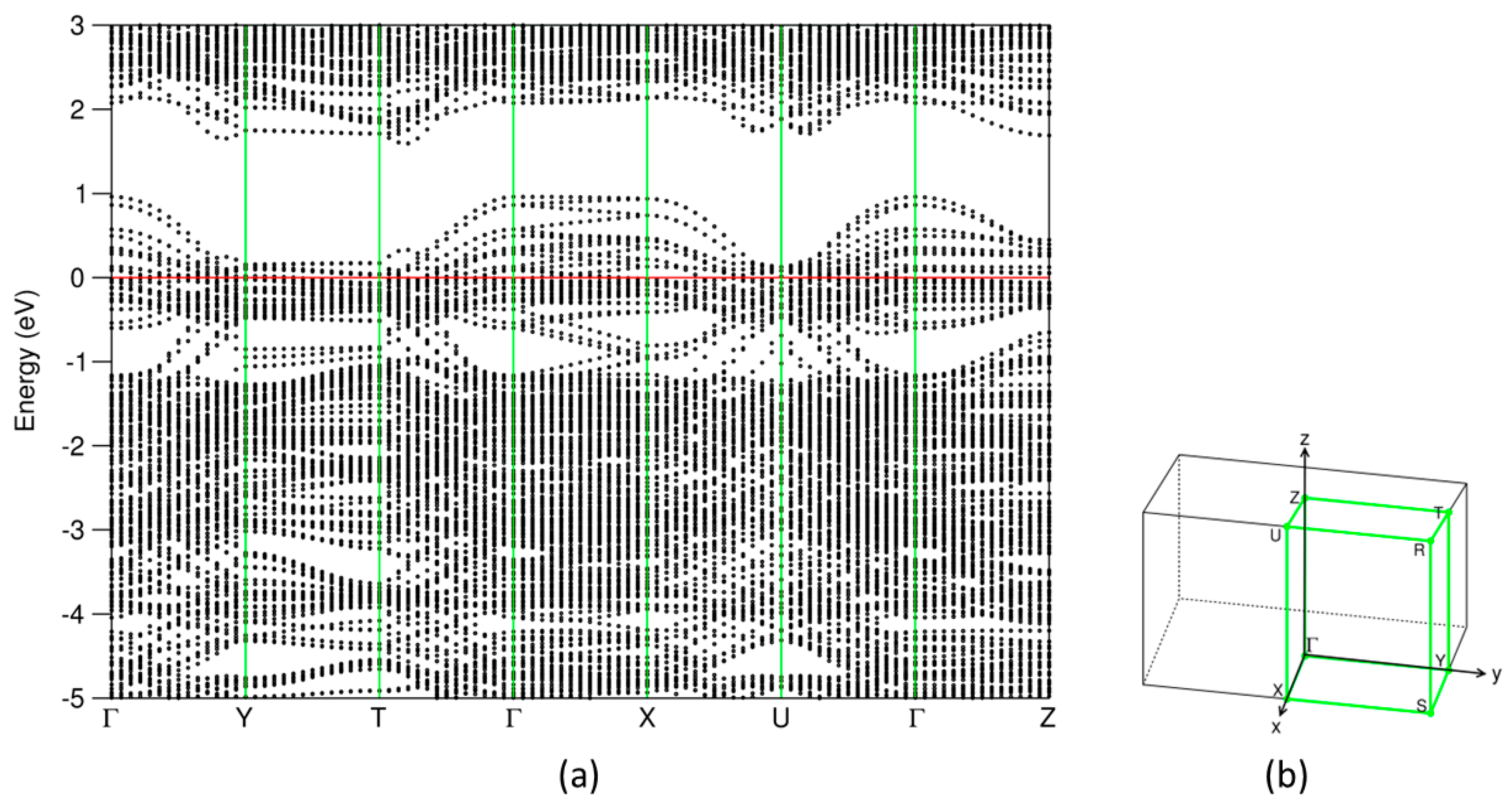

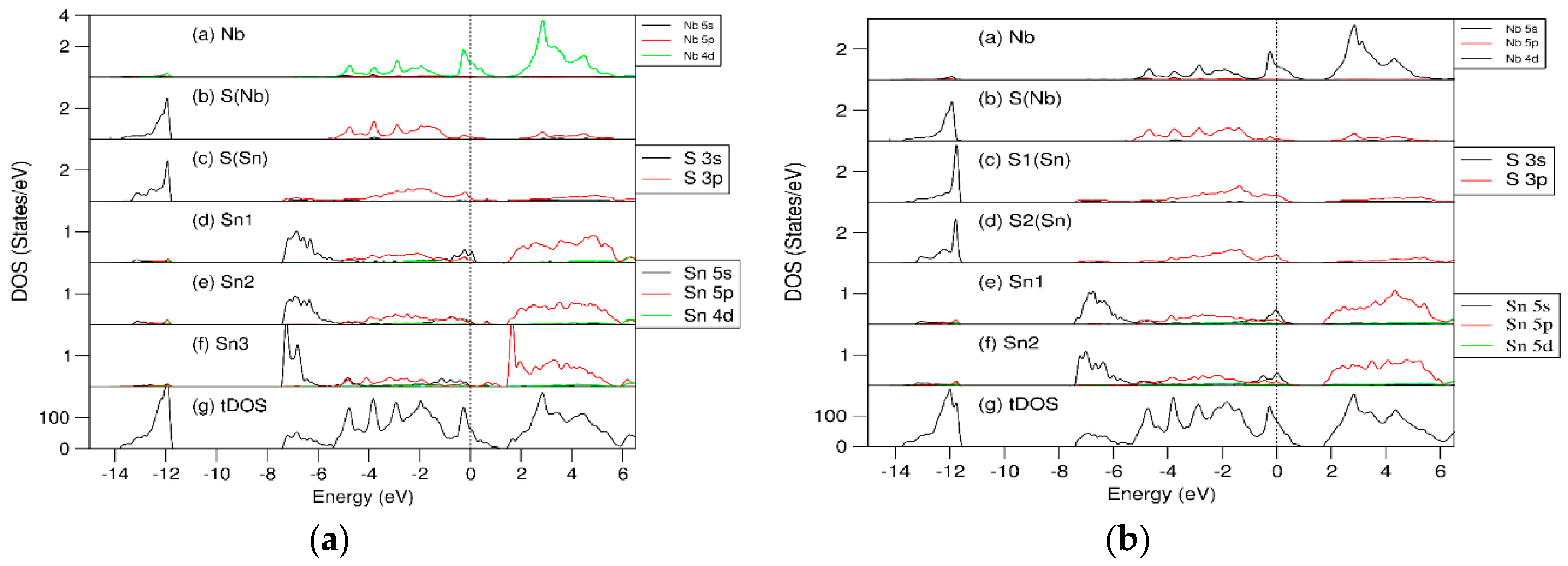

3.3. Electronic Structure of (SnS)1.167NbS2

3.4. Effects of Sn or S Vacancy on the Local Bonding in (SnS)1.67NbS2

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement:

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wiegers, G.A.; Meetsma, A.; van Smaalen, S.; Hannge, R. J.; Wulff, J.; Zeinstra, T.; de Boer, J. L.; Kuypers, S.; van Tendeloo, G.; van Landuyt, J.; Amelinckx, S.; Meerschaut, A.; Rabu, P.; Rouxel, J. Misfit layer compounds (MS)nTS2 (M = Sn, Pb, Bi, rare earth elements; T = Nb, Ta; n = 1.08 – 1.19), a new class of layer compounds, Solid State Commun. 1989, 70, 409-413. [CrossRef]

- Meerschaut, A. Misfit layer compounds, Curr. Op. Solid State Mater. Sci. 1996, 1, 250-259. [CrossRef]

- Rouxel, J.; Meerschaut, A.; Wiegers, G. A. Chalcogenid misfit layer compounds, J. Alloys Compds. 1995, 229, 144-157. [CrossRef]

- Wiegers, G. A. Misfit layer compounds: structures and physical properties, Prog. Solid State Chem. 1996, 24, 1-139. [CrossRef]

- Ng, N.; McQueen, T. M. Misfit layered compounds: Unique, tunable heterostructured materials with untapped properties, APL Mater. 2022, 10, 100901. [CrossRef]

- Leriche, R. T.; Palacio-Morales, A.; Campetella, M.; Tresca, C.; Sasaki, S.; Brun, C.; Debontridder, F.; David, P.; Arfaoui, I.; Šofranko, O.; Samuely, T.; Kremer, G.; Monney, C.; Jouen, T.; Cario, L.; Calandra, M.; Cren, T. Misfit layer compounds: A platform for heavily doped 2D transition metal dichalcogenides, Adv. Func. Mater. 2020, 31, 2007706. [CrossRef]

- Zullo, L.; Marini, G.; Cren, T.; Calandra, M. Misfit layer compounds as ultratunable field effects transistors: From charge transfer control to emergent superconductivity, Nano Lett. 2023, 23, 6658-6663. [CrossRef]

- Nader, A.; Briggs, A.; Gotoh, Y. Superconductivity in the misfit layer compounds (BiSe)1.10(NbSe2) and (BiS)1.11(NbS2), Solid state Commun. 1997, 101, 149-153. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. T.; Bai, J. H.; Long, H. Y.; Yang S. C.; Chen, W. W.; Wang, Q. Y.; Sa, B. S.; Guo, Z. Y.; Zheng, J. Y.; Pei, J. J.; Du, K.-Z.; Zhan, H. B. Thermally activated photoluminescence induced by tunable interlayer interaction in naturally occurring van der Waals superlattice SnS/TiS2, Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 6061-6068. [CrossRef]

- Merrill, D. R.; Moore, D. B.; Bauers, S. R.; Falmbigl, M.; Johnson, D. C. Misfit layer compounds and ferecrystals: Model systems for thermoelectric nanocomposites, Materials, 2015, 8, 2000-2029. [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, T.; Joswig, J.-O.; Seifert, G. Two-dimensional and tubular structures of misfit compounds: structural and electronic properties, Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2014, 5, 2171-2178. [CrossRef]

- Serra, M.; Tenne, R. Nanotubes from misfit layered compounds, J. Coord. Chem. 2018, 71, 1669-1678. [CrossRef]

- Sreedhara, M. B.; Bukvišová, K.; Khadiev, A.; Citterberg, D.; Cohen, H.; Balema, V.; Pathak, A. K.; Novikov, D.; Leitus, G.; Kaplan-Ashiri, I.; Kolíbal, M.; Enyashin, A. N.; Houben, L.; Tenne, R. Nanotubes from the misfit layered compound (SmS)1.19TaS2: Atomic structure, charge transfer, and electric properties, Chem. Mater. 2022, 34, 1838-1853. [CrossRef]

- Lemon, M.; Harvel, F. G.; Gannon, R. N.; Lu, P.; Rudin, S. P.; Johnson, D. C. Targeted synthesis of predicted metastable compounds using modulated elemental reactants, J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2023, 41, 022203. [CrossRef]

- van Smaalen, S. A superspace group description of the misfit layer structure of (SnS)1.17(NbS2), J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 1989, 1, 2791-2800. [CrossRef]

- Jobst, A.; van Smaalen, S. Intersubsystem chemical bonds in the misfit layer compounds (LaS)1.13TaS2 and (LaS)1.14NbS2, Acta Cryst. B 2002, 58, 179-190. [CrossRef]

- Fan, H. F.; van Smaalen, S.; Lam, E. J. W.; Beurskens, P. T. Direct methods for incommensurate intergrowth compounds. I. determination of modulation, Acta Cryst. A 1993, 49, 704-708. [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Chen, D.; Zhao, H. F.; Yao, Y.; Liu, X. Y.; Yu, R. C. Misfit-layered compound PbTiS3 with incommensurate modulation: transmission electron microscopy analysis and transport properties, Chin. Phys. B 2013, 22, 116102. [CrossRef]

- Meerschaut, A.; Guemas, L.; Auriel, C.; Rouxel, J. Preparation, structure determination and transport properties of a new misfit layer compound: (PbS)114(NbS2)2. Eur. J. Solid State Inorg. Chem. 1990, 27, 557-570.

- Wiegers, G. A.; Haange, R. J. Electric transport and magnestic properties of the misfit layer compound (LaS)1.14NbS2, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter, 1990, 2, 455-463. [CrossRef]

- Sourisseau, C.; Cavagnat, R.; Tirodo, J. L. A Raman study of the misfit layer compounds, (SnS)1.17NbS2 and (PbS)1.18TiS2, J. Ramman Spec. 1992, 23, 647-651. [CrossRef]

- Fang, C. M.; Ettema, A. R. H.; Haas, C.; Wiegers, G. A.; van Leuken, H.; de Groot, R. A. Electronic structure of the misfit -layer compound (SnS)1.17NbS2 deduced from band-structure calculations and photoelectron spectra, Phys. Rev. B 1995, 52, 2336-2347.

- Krasovskki, E.E.; Tiedje, O.; Schottke, W.; Brandt, J.; Kanzow, J.; Rossnagel, K.; Kipp, L.; Skibowski, M.; Hytha, M.; Winkler, B. Electronic structure and UPS of the misfit chalcogenide (SnS)NbS2 and related compounds, J. Elec. Spec. related phenomena, 2001, 114-116, 1133-1138. [CrossRef]

- Göhler, F.; Mitechson, G.; Alemayehu, M. B.; Speck, F.; Wanke, M.; Johnson, D. C.; Seyller, T. Charge transfer in (PbSe)1+δ(NbSe2)2 and (SnSe)1+δ(NbSe2)2 ferecrystals investigated by photoelectron spectroscopy, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2018, 30, 055001.

- Fang, C. M.; van Smaalen, S.; Wiegers, G. A.; Haas, C.; de Groot, R. A. Electronic structure of the misfit layer compound (LaS)1.14NbS2: Band-structure calculations and photoelectron spectra, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 1996, 8, 5367-5382.

- Chikina, A.; Bhattacharyya, G.; Curcio, D.; Sanders, C. E.; Bianchi, M.; Lanatà, N.; Watson, M.; Cacho, C.; Breholm, M.; Hofmann, P. One-dimensional electronic states in a natural misfit structure, Phys. Rev. Mater. 2002, 6, L092001. [CrossRef]

- Fang, C. M.; Wiegers, G. A.; Haas, C. Charge transfer and photoemission spectra of some later rare earth misfit layer compounds, (LnS)1+xTS2 (Ln = Tb, Dy, Ho; T = Nb, Ta), Physica: Condens. Matter 1997, 233, 134-138.

- Beekman, M.; Heideman, C. L.; Johnson, D. C. Ferecrystals: non-epitaxial layered intergrowths, Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2014, 29, 064012. [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, G. R.; Richter, K. W. Review of vanadium-based layered compounds, J. Alloys Compds. 2021, 891, 161976. [CrossRef]

- Deudon, C.; Lafond, A.; Leynaud, O.; Moëlo, Y.; Meerschaut, A. Quantification of the interlayer charge transfer, via bond valence calculation, in a 2D misfit compounds: The case of (Pb(Mn,Nb)0.5S1.5)1.15NbS2, J. Solid State Chem. 2000, 155, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Gotoh, Y. Structural stability and charge transfer of (SnS0.93)1.17NbS2 by accurate modelling of incommensurate composite crystal structure using information criterion, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2021, 90, 094601.

- Brandt, J.; Kanzow, J.; Roßbagl, K.; Kipp, L.; Skibowski, M.; Krasovskii, E.; Schattke, W.; Traving, M.; Stettner, J.; Press, W.; Dieker, C.; Jäger, W. Band structure of the misfit compound (PbS)NbS2 compared to NbSe2: experiment and theory, J. Electron Spec. Related Phenomena, 2001, 114-116 555-561. [CrossRef]

- Kabliman, E.; Blaha, P.; Schwarz, K. Ab initio study of stabilization of the misfit layer compound (PbS)1.14TaS2, Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82, 125308.

- Abramov, S. P. Varieties of charge transfer and bonding between layers in misfit layer compounds (MX)xTX2, J. Alloys Compds. 1997, 259, 212-218.

- Fang, C. M.; de Groot, R. A.; Wiegers, G. A.; Haas, C. Band structure calculations and photoemission spectra of (SnS)1.20TiS2, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 1996, 8, 1663-1667.

- Fang, C. M.; de Groot, R. A.; Wiegers, G. A.; Haas, C. Electronic structure and evidence for La vacancies in the misfit layer compound (LaS)1.20CrS2, J. Phys. Chem. Solids, 1997, 58, 1103-1109. [CrossRef]

- Cario, L.; Johrendt, D.; Lafond, A.; Felser, C.; Meerschaut, A.; Rouxel, J. Stability and charge transfer in the misfit layer compound, (LaS)(SrS)0.2CrS2: Ab initio band-structure calculations, Phys. Rev. B 1997, 55, 9409-9414.

- Wiegers, G. A.; Meetsma, A.; Haange, R. J.; de Boer, J. Structure and physical properties of (SnS)1.18NbS2, ‘‘SnNbS3’’, a compound with misfit layer structure, Mat. Res. Bull. 1988, 23, 1551-1559. [CrossRef]

- Meetsma, A.; Wiegers, G. A.; Haange, R. J.; de Boer, J. L. The incommensurate misfit layer structure of (SnS)1.17NbS2, ‘SnNbS3’: I. A study by means of X-ray diffraction, Acta Cryst. A 1989, 45, 285-291. [CrossRef]

- Ohno, Y. Electronic structure of the misfit layer compounds PbTiS3 and SnSbS3, Phys. Rev. B 1991, 44, 1281-1291.

- Klimes, J.; Bowler, D. R.; Michelides, A. Chemical accuracy for the van der Waals density functional, J. Phys.: Cond. Matt. 2010, 22, 022201. [CrossRef]

- Klimes, J.; Bowler, D. R.; Michelides, A. Van der Waals density functionals applied to solids, Phys. Rev. B 2011, 83, 195131. [CrossRef]

- Cowley, J. M.; Ibers, J. A. The structures of some ferric chloride-graphite compounds, Acta Cryst. 1956, 9, 421-431. [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal-amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium, Phys. Rev. B 1994, 49; 14251–14269.

- Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method, Phys. Rev. B 1994, 50, 17953–17978. [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J. P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple, Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [CrossRef]

- Fang, C. M.; Mohammadi, V.; Nihtianov, S.; Sluiter, M. F. H. Stability, geometry and electronic properties of BHn (n= 0 to 3) radicals on the Si(001)3×1:H surface from first-principles, J. Phys. Cond. Matter 2020, 32, 235201.

- Monkhorst, H. J.; Pack, J. P. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations, Phys. Rev. B 1976, 13, 5188–5192. [CrossRef]

- Wiedemeier, H.; von Schnering, H. G. Refinement of the structure of GeS, GeSe, SnS and SnSe, Z. Kristollogr. 1978, 148, 295-303.

- von Schnering, H. G.; Wiedemeier, H. The high temperature structure of β-SnS and β-SnSe and the B16 to B33 type λ-transition path, Z. Kristollogr. 1981, 156, 143-150.

- Ettema, A. R. H. F.; Groot, R. A.; Haas, C.; Turner, T. S. Electronic structure of SnS deduced from photoelectron spectra and band-structure calculations. Phys. Rev. B, 1992, 46, 7363-7373. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, W. G.;. Sienko, M. J. Stoichiometry, structure, and physical properties of niobium disulfide, Inorg. Chem. 1980, 19, 39-43.

- Morosin, B. Structure refinement on NbS2, Acta Cryst. B 1974, 30, 551-552.

- Jones, R. O. Density functional theory: Its origins, rise to prominence, and future, Rev. Mod. Phys. 2015, 87, 897-923. [CrossRef]

- Fang, C. M.; Wiegers, G. A.; Meetsma, A.; de Groot, R. A.; Haas, C. Crystal structure and band structure calculations of Pb1/3TaS2 and Sn1/3NbS2, Physica B 1996, 226, 259-267.

- Bader, R. F. W. A quantum-theory of molecular-structure and its applications. Chem. Rev. 1991, 91, 893–928. [CrossRef]

- Bader, R. F. W. A bonded path: A universal indicator of bonded interactions. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 7314–7323. [CrossRef]

| Compound | Latt., spacegroup |

Latt. Parameters (Å) a, b, c |

Energy (eV/f.u.) |

Gap (eV) |

Charge(e) | Remarks |

| α-SnS GGA+vdW Exp. |

orth. Pnma(no.62) |

11.404, 4.040, 4.363 11.200, 3.987, 4.334[49] |

-4.829 - |

0.88 1.11[51] |

Sn+0.45S-0.45 |

Each Sn has three S neighbors and two Sn neighbors |

| β-SnS GGA+vdW Exp. |

orth. Cmcm(no.63) |

4.108, 11.643, 4.124 4.148, 11.480, 4.177[50] |

-4.802 - |

0.32 - |

Sn+0.94S-0.94 |

Each Sn has five S neighbors and two Sn neighbors |

| NaCl-type GGA+vdW Exp. |

Cubic Fm-3m(no.225) |

5.845, 5.845, 5.845 - |

-4.760 - |

0.07 - |

Sn+1.10S-1.10 |

Each Sn has six S neighbors |

| 2Ha-NbS2 GGA+vdW 2Hb-NbS2 GGA+vdW Exp. 3R-NbS2 GGA+vdW Exp. |

Hex. P63/mmc(no.194) Hex. P63/mmc(no.194) Romh. R-3m(no.166) |

3.372, 3.372,12.877 3.374, 3.374, 12.024 3.324, 3.324, 11.95 [52] 3.345, 3.345, 18.258 3.330,3.330,17.918 [53] |

-15.195 - -15.627 - -15.711 - |

- - - - - - |

Nb+1.28(S-0.64)2 Nb+1.14(S-0.57)2 Nb+1.16(S-0.58)2 |

Nb in prismatic coordination Nb in antiprismatic coordination Nb in antiprismatic coordination |

| Structure | Symmetry | Latt.paras.(Å) and deviation (Δ) a, b, c Z |

ΔE (eV/NbS2) |

| (a) (SnS)1.200NbS2 | C2 (no. 5) | 16.871(1.6%), 5.770(0.5%), 12.112(3.0%) 10 | -0.16 |

| (b) (SnS)1.167NbS2_a | Pa (no.7) | 40.077(0.6%), 5.781(0.5%), 11.849(0.7%) 24 | -0.40 |

| (c) (SnS)1.167NbS2_b | Pa (no.7) | 40.081(0.6%), 5.778(0.5%), 11.874(1.0%) 24 | -0.40 |

| (d) (SnS)1.143NbS2 | C2 (no. 5) | 23.202(-0.2%),5.791(0.7%), 11.856(0.8%) 14 | -0.22 |

| (e) (SnS0.929)1.167NbS2_a | C2 (no. 5) | 40.001, 5.804, 12.081 24 | - |

| (f) (SnS0.929)1.167NbS2_b | P1 (no. 1) | 39.947, 5.811, 11.901 24 | - |

| (g) (Sn0.929S)1.167NbS2 | C2(no. 5) | 39.888, 5.773, 11.813 24 | - |

| Experimental (SnS)1.171NbS2 Composite [38,39] |

Cm2a C2m2 |

5.673, 5.751, 11.761 4 (SnS) 3.321, 5.751, 11.761 2(NbS2) |

- |

| Element | Bonds(Å) | Charge (e/atom) |

| Nb | Nb-S(Nb): 2.48 to 2.50 (×6) | +0.99 to 1.51 Av.: +1.24 |

| S(Nb) | S-Nb: 2.48 to 2.50 (×6) -Sn: 3.21 to 3.25 |

-0.50 to -0.90 Av.: -0.70 |

| S(Sn) | S-Sn: 2.64 to 3.00 (×5) | -0.55 to -0.93 Av: -0.74 |

| Sn | Sn-S(Sn): 2.64 to 3.00 (×5) -S(Nb): 3.21 to 3.25 |

+0.70 to +1.23 Av. +0.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).