1. Introduction

The imperative for sustainable waste management has become increasingly critical in the contemporary world, driven by the growing awareness of environmental degradation and the pressing need to mitigate the adverse impacts of waste on ecosystems. Within this context, the European Union (EU) has been a global leader in implementing stringent policies and innovative practices aimed at enhancing recycling rates and promoting the circular economy. This paper delves into the intricate relationship among recycling rates, technological innovation, and waste management practices across various European countries, offering a comprehensive analysis of the current state and future prospects of recycling in the region. The aim of the study is to explore the multifaceted dynamics that influence recycling rates in European countries, particularly focusing on the interplay between technological advancements and waste management strategies. By examining the recycling performance of different nations within the EU, this research seeks to identify key drivers and barriers that shape recycling practices, thereby providing valuable insights for policymakers, industry stakeholders, and researchers dedicated to fostering sustainable waste management solutions. Recycling has emerged as a pivotal component of sustainable waste management, offering a viable solution to reduce landfill use, conserve natural resources, and lower greenhouse gas emissions. In Europe, the push towards higher recycling rates has been underscored by the EU's ambitious waste management directives, such as the Waste Framework Directive and the Circular Economy Action Plan (Araya, 2018; Aldieri et al., 2019).

These policies set stringent recycling targets and promote the adoption of practices that prioritize waste reduction, reuse, and recycling. Technological innovation plays a crucial role in enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of recycling processes. Advanced technologies, including automated sorting systems, smart waste bins, and data analytics, have revolutionized waste management, enabling more accurate and efficient collection, sorting, and processing of recyclable materials. Countries that have successfully integrated these technologies into their waste management systems have achieved higher recycling rates, demonstrating the positive impact of innovation on recycling performance. The primary objective of this study is to analyze the factors contributing to the varying recycling rates across European countries. Specifically, the research aims to assess the impact of technological advancements on recycling rates by examining how adopting innovative technologies in waste management systems influences the efficiency and effectiveness of recycling processes. Additionally, it seeks to identify key drivers and barriers to recycling by exploring the economic, social, and policy-related factors that affect recycling rates, aiming to uncover the critical elements that drive or hinder the success of recycling initiatives. The study also compares the recycling performance of different European countries through a comparative analysis, highlighting best practices and providing benchmarks that can guide other nations in improving their recycling systems. Furthermore, it evaluates the role of policy frameworks in shaping recycling outcomes by analyzing the impact of EU regulations and national policies on recycling rates, and identifying how legislative measures can support or impede recycling efforts (Tallentire and Steubing, 2020; Larrain et al., 2021).

This study employs a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative data analysis with qualitative case studies to provide a holistic understanding of the factors influencing European recycling rates. The quantitative analysis uses statistical methods to examine the relationship between technological innovation, policy frameworks, and recycling rates across different countries. Data is sourced from reputable databases, including Eurostat and the Global Innovation Index, ensuring the reliability and validity of the findings. The qualitative component includes case studies of selected European countries that exemplify high, moderate, and low recycling rates. These case studies offer in-depth insights into the specific practices, challenges, and successes experienced by each country, providing valuable contextual information that complements the quantitative analysis. Preliminary findings indicate a positive correlation between the adoption of advanced waste management technologies and higher recycling rates. Countries such as Germany, Sweden, and the Netherlands, which have invested heavily in innovative recycling technologies, exhibit some of the highest recycling rates in Europe (Ghaffar et al., 2020; Noll et al., 2021).

These nations have implemented comprehensive waste management systems that leverage technology to optimize the collection, sorting, and processing of recyclable materials. Conversely, countries with lower recycling rates, such as Bulgaria and Romania, face significant challenges, including inadequate infrastructure, limited public awareness, and insufficient policy support. These barriers hinder the effective implementation of recycling programs, highlighting the need for targeted interventions to enhance recycling performance. The study also underscores the critical role of policy frameworks in driving recycling outcomes. EU directives have been instrumental in setting high standards for waste management, compelling member states to adopt stringent recycling targets and practices. However, the effectiveness of these policies varies across countries, influenced by factors such as governance, economic conditions, and public engagement. The relationship between recycling rates, technological innovation, and waste management practices in Europe is complex and multifaceted. While technological advancements have significantly improved recycling performance in several countries, achieving high recycling rates requires a holistic approach that integrates policy support, public awareness, and robust infrastructure. This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the factors influencing recycling rates in European countries, offering valuable insights for stakeholders committed to advancing sustainable waste management practices. By addressing the identified barriers and leveraging the drivers of recycling success, Europe can enhance its recycling performance, contributing to environmental sustainability and resource conservation (Ibănescu et al., 2017; Bassi et al., 2017).

The article continues as follows:

Section 2 presents the literature review,

Section 3 shows the metric characteristics of the dataset used and contains the description of the variables,

Section 4 shows the clustering with the k-Means algorithm,

Section 5 analyses the econometric model,

Section 6 presents the policy implications, and

Section 7 concludes.

2. Literature Review

Below, a literature review is discussed to introduce the topic within the EU context.

Circular Economy and Waste Management. Zhang et al. (2022) provide an insightful overview of the waste hierarchy framework, focusing on the circularity in construction and demolition waste management in Europe. Zorpas (2020) discusses strategic developments within the waste management framework, highlighting essential policy implications. Ranjbari et al. (2021) analyze two decades of research on waste management in the circular economy, utilizing bibliometric, text mining, and content analyses to identify key trends and gaps. Li et al. (2020) explore the application of information technologies in managing construction and demolition waste, underscoring emerging trends and innovations. Salmenperä et al. (2021) identify critical factors for enhancing the circular economy in waste management, emphasizing the need for integrated policy frameworks. Spooren et al. (2020) review near-zero-waste processing of low-grade, complex primary ores and secondary raw materials in Europe, pointing out technology development trends. Tsai et al. (2020) use a data-driven bibliometric analysis to assess municipal solid waste management within a circular economy context. Kurniawan et al. (2022) investigate the role of digital technologies in transforming waste recycling within Industry 4.0 towards a digitalization-based circular economy in Indonesia. Bao and Lu (2020) draw lessons from Shenzhen, China, to develop efficient circularity in construction and demolition waste management in rapidly emerging economies. Marino and Pariso (2020) compare European countries' performances in transitioning towards the circular economy, providing valuable benchmarks. Mhatre et al. (2021) conducted a systematic literature review on circular economy initiatives in the EU, identifying key drivers and barriers. Razzaq et al. (2021) explore the dynamic and causality interrelationships between municipal solid waste recycling, economic growth, carbon emissions, and energy efficiency using a novel bootstrapping autoregressive distributed lag approach. Giorgi et al. (2022) analyze the drivers and barriers to circular economy practices in the building sector through stakeholder interviews in five European countries. Mak et al. (2020) review sustainable food waste management policies towards a circular bioeconomy, identifying limitations and opportunities. Farrell et al. (2020) discuss the technical challenges and opportunities in realizing a circular economy for waste photovoltaic modules. Aslam et al. (2020) compare construction and demolition waste management practices between China and the USA. Bui et al. (2020) use the fuzzy Delphi method to identify barriers to sustainable solid waste management in practice. Kabirifar et al. (2020) review contributing factors to effective waste management strategies focused on reduce, reuse, and recycle principles. Duque-Acevedo et al. (2020) review the evolution and alternative uses of agricultural waste, providing a global perspective. Kovacic et al. (2020) critically analyze circular economy policies and imaginaries in Europe, offering a theoretical framework. Massaro et al. (2021) explore academic and practitioner perspectives on integrating Industry 4.0 with the circular economy. Ciccullo et al. (2021) examine the implementation of circular economy paradigms in the agri-food supply chain, highlighting food waste prevention technologies. Donner et al. (2021) identify critical success and risk factors for circular business models valorizing agricultural waste and by-products. Xiao et al. (2020) analyze policy impacts on municipal solid waste management in Shanghai using a system dynamics model. Esparza et al. (2020) review conventional and emerging approaches to fruit and vegetable waste management. Lastly, Fatimah et al. (2020) present a case study from Indonesia on using Industry 4.0-based sustainable circular economy approaches for smart waste management systems to achieve sustainable development goals. The selected articles provide a comprehensive overview of various aspects of waste management, highlighting the importance of sustainable practices and the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Andreichenko et al. (2021) emphasize the critical need for balanced biosphere management in agricultural waste, pointing out the necessity for integrated approaches to ensure environmental sustainability. Awasthi et al. (2021) discuss the zero-waste approach, advocating for sustainable waste management systems that prioritize reducing, reusing, and recycling materials to minimize environmental impact. Istrate et al. (2020) review the life-cycle environmental consequences of waste-to-energy solutions, underscoring the potential benefits and drawbacks of these systems in managing municipal solid waste. Kulkarni and Anantharama (2020) and Van Fan et al. (2021) both address the significant disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic on waste management practices, identifying new challenges and opportunities for improving waste management resilience in the face of global crises. Finally, Pardini et al. (2020) explore innovative solutions for smart waste management, demonstrating how citizen engagement and advanced technologies can enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of waste management systems. Magazzino et al. (2021b) provide a timely and critical examination of the relationship between waste generation, economic wealth, and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in Denmark. As nations worldwide strive to transition towards more sustainable and circular economies, this study addresses a pivotal concern: whether wealthier nations like Denmark are effectively managing their waste in ways that minimize environmental impact.

E-Waste and Technological Perspectives. Parajuly et al. (2020) focus on behavioral changes necessary for the circular economy, specifically targeting electronic waste management in the EU, highlighting the importance of public engagement and policy initiatives. Shittu et al. (2021) review global e-waste management trends, legislation, contemporary issues, and future challenges, emphasizing the critical role of legislation in shaping effective e-waste management practices. Rene et al. (2021) discuss the generation, recycling, and resource recovery of electronic waste, providing a technological perspective on current trends and advancements in this field. Arya and Kumar (2020) examine e-waste management in India, detailing current trends, regulations, challenges, and strategies, and underscore the regulatory framework necessary to tackle the e-waste problem in developing countries. Ahirwar and Tripathi (2021) review recycling processes, environmental and occupational health hazards, and potential solutions in e-waste management, drawing attention to the health risks associated with improper e-waste handling. Patil and Ramakrishna (2020) provide a comprehensive analysis of global e-waste legislation, comparing regulatory approaches across different countries and their effectiveness in managing e-waste. Chidepatil et al. (2020) explore how blockchain and multi-sensor-driven artificial intelligence can transform the circular economy of plastic waste, presenting innovative technological solutions to waste management. Mahrad et al. (2020) review the application of remote sensing technologies in coastal and marine environmental management, demonstrating how advanced technologies can support holistic environmental management practices. Jain et al. (2022) discuss bioenergy and bio-products from bio-waste within the context of the modern circular economy, highlighting current research trends and future outlooks. Awan and Sroufe (2022) analyze the design of circular business models for sustainability in the circular economy, offering insights into the dynamics of sustainable business practices. Lv and Li (2021) examine the impact of financial development on CO2 emissions using a spatial econometric analysis, illustrating the interplay between economic development and environmental sustainability. Levidow and Raman (2020) critically assess the sociotechnical imaginaries of low-carbon waste-energy futures in the UK, questioning the accountability of techno-market solutions. Sala et al. (2021) trace the evolution of life cycle assessment in European policies over three decades, showing the increasing integration of life cycle thinking into policy frameworks. Finally, Knickmeyer (2020) reviews social factors influencing household waste separation, identifying good practices to improve recycling performance in urban areas. Delcea et al. (2020) analyze the determinants influencing individuals' decisions to recycle e-waste in Romania, providing insights into behavioral factors that can enhance recycling rates. Li et al. (2022) discuss the chemical aspects, current status, and challenges of expanding plastic recycling technologies, highlighting the need for advancements in chemical recycling to tackle plastic waste. Solis and Silveira (2020) provide a technical review and Technology Readiness Level (TRL) assessment of technologies for chemical recycling of household plastics, stressing the potential and limitations of these technologies in managing plastic waste. Vollmer et al. (2020) explore beyond mechanical recycling, proposing new methods to give plastic waste a second life, thereby emphasizing the importance of innovative recycling techniques. Azzaz et al. (2020) review the production, characterization, and application of hydro chars for wastewater treatment, showcasing the potential of hydro char as a sustainable material in environmental management. RameshKumar et al. (2020) delve into bio-based and biodegradable polymers, discussing the state-of-the-art, challenges, and emerging trends in developing sustainable polymer alternatives. Yao et al. (2020) focus on the anaerobic digestion of livestock manure in cold regions, examining technological advancements and their global impacts, which are crucial for sustainable waste management in agriculture. The article by Imran et al. (2024) investigates the impact of environmental technology, taxes, and carbon emissions on incineration practices in EU countries, highlighting the significant role of regulatory and technological advancements in shaping waste management. Mele et al. (2022) employ Spectral Granger Causality Analysis and Artificial Neural Networks to explore the relationship between innovation, income, and waste disposal operations in Korea, offering a sophisticated methodological approach and unique insights into the influence of economic and technological factors on waste management. Magazzino et al. (2021c) examine the nexus between information technology and environmental pollution in OECD countries through a novel machine-learning algorithm, emphasizing the potential of IT to mitigate environmental impacts and providing a forward-looking perspective on leveraging technological advancements to address pollution challenges in developed economies.

Environmental Impacts and Policies. Khan et al. (2022) examine the current status, challenges, and future perspectives of technologies for municipal solid waste management, highlighting the technological advancements and their implications. Ding et al. (2021) provide a comparative analysis of China’s municipal solid waste management and technologies with international regions, focusing on treatment and resource utilization. Sauve and Van Acker (2020) conduct a life cycle assessment of municipal solid waste landfills in Europe, emphasizing the environmental impacts and supporting decision-making processes. Pham et al. (2020) explore the environmental consequences of population, affluence, and technological progress in European countries from a Malthusian perspective, addressing the implications of economic growth on waste generation. Guo et al. (2021) analyze the policy and driving factors of solid waste management in China from 2004 to 2019, providing insights into the effectiveness of policy interventions. Hainsch et al. (2022) discuss energy transition scenarios in the EU Green Deal context, focusing on the required policies, societal attitudes, and technological developments. Hoang et al. (2022) review the characteristics, management strategy, and role of municipal solid waste-to-energy routes in the circular economy, identifying the benefits and limitations of waste-to-energy technologies. Chen et al. (2020) discuss global trends and impacts of municipal solid waste, highlighting the growing waste generation and its environmental implications. Kehrein et al. (2020) provide a critical review of resource recovery from municipal wastewater treatment plants, identifying market supply potentials, technologies, and bottlenecks. Nanda and Berruti (2021) review municipal solid waste management and landfilling technologies, discussing current practices and future advancements. Zhu et al. (2021) examine the fate and removal of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes using biological wastewater treatment technologies, addressing public health concerns. Abbasi et al. (2022) explore the role of financial development and technological innovation towards sustainable development in Pakistan, highlighting the interaction between economic factors and environmental sustainability. Khan and Kabir (2020) analyze waste-to-energy generation technologies in developing economies, using a multi-criteria analysis for sustainability assessment. Chowdhury et al. (2020) review end-of-life material recycling for solar photovoltaic panels, emphasizing the need for sustainable recycling technologies. Durán-Romero et al. (2020) discuss bridging the gap between circular economy and climate change mitigation policies through eco-innovations and the Quintuple Helix Model. Tan et al. (2021) provide a bibliometric study on the global evolution of research on green energy and environmental technologies, identifying key research trends. Altıntaş and Kassouri (2020) investigate the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) in Europe, examining the relationship between per-capita ecological footprint and CO2 emissions. Freeman et al. (2020) discuss the role of wastewater treatment in reducing marine microplastics, addressing a critical environmental issue. Doğan et al. (2020) analyze the European commitment to COP21 and the role of energy consumption, FDI, trade, and economic complexity in sustaining economic growth. Moustakas et al. (2020) review recent developments in renewable and sustainable energy systems, highlighting key challenges and future perspectives. Cainelli et al. (2020) examine resource-efficient eco-innovations for a circular economy, presenting evidence from EU firms. Klemeš et al. (2020) discuss strategies to minimize plastic waste, energy, and environmental footprints related to COVID-19. Bertello et al. (2022) provide insights from the Pan-European hackathon ‘EUvsVirus’ on open innovation in the face of the COVID-19 grand challenge. Söderholm (2020) addresses the challenges of technological change for sustainability in the green economy transition. Sulich and Rutkowska (2020) analyze definitional issues and the employment of young people in green jobs across three EU countries. Ojha et al. (2020) discuss food waste valorization and circular economy concepts in insect production and processing. Alhawari et al. (2021) review circular economy literature, unraveling paths to future research. Finally, Zhang et al. (2021) review state-of-the-art technologies and future perspectives for the treatment of municipal solid waste incineration fly ash, addressing critical environmental concerns. Balsalobre-Lorente et al. (2021) investigate the carbon dioxide-neutralizing effects of energy innovation on international tourism in EU-5 countries, applying the EKC hypothesis to demonstrate how technological advancements can mitigate environmental impacts in the tourism sector. Ferreira et al. (2020) compare European countries, focusing on the relationship between technology transfer, climate change mitigation, and environmental patents, highlighting their positive impact on sustainability and economic growth. Jiang et al. (2021) examine the significant effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on energy demand and consumption, discussing both challenges and emerging opportunities for improving energy efficiency and resilience. Ortega-Gras et al. (2021) analyze the twin transition towards industry 4.0 technologies, providing desk-research analysis and practical use cases in Europe to illustrate how these technologies can drive sustainability and industrial innovation. Streimikiene et al. (2021) conduct a systematic literature review on sustainable tourism development and competitiveness, offering insights into the factors that influence the sustainable growth of tourism industries while maintaining competitiveness. Magazzino and Falcone (2022) assess the intricate relationship between waste generation, economic wealth, and GHG emissions in Switzerland, proposing policy recommendations to optimize municipal solid waste management within a circular economy framework. Their insights provide valuable guidance for enhancing sustainability practices. Magazzino, et al. (2020) examine the link between municipal solid waste and greenhouse gas emissions in Switzerland, offering empirical evidence that underscores the environmental impact of waste management practices.

A summary of the relevant literature by macro-theme is shown in

Table 1 below.

3. Materials

The following section presents the variables and descriptive statistics (see

Table 2).

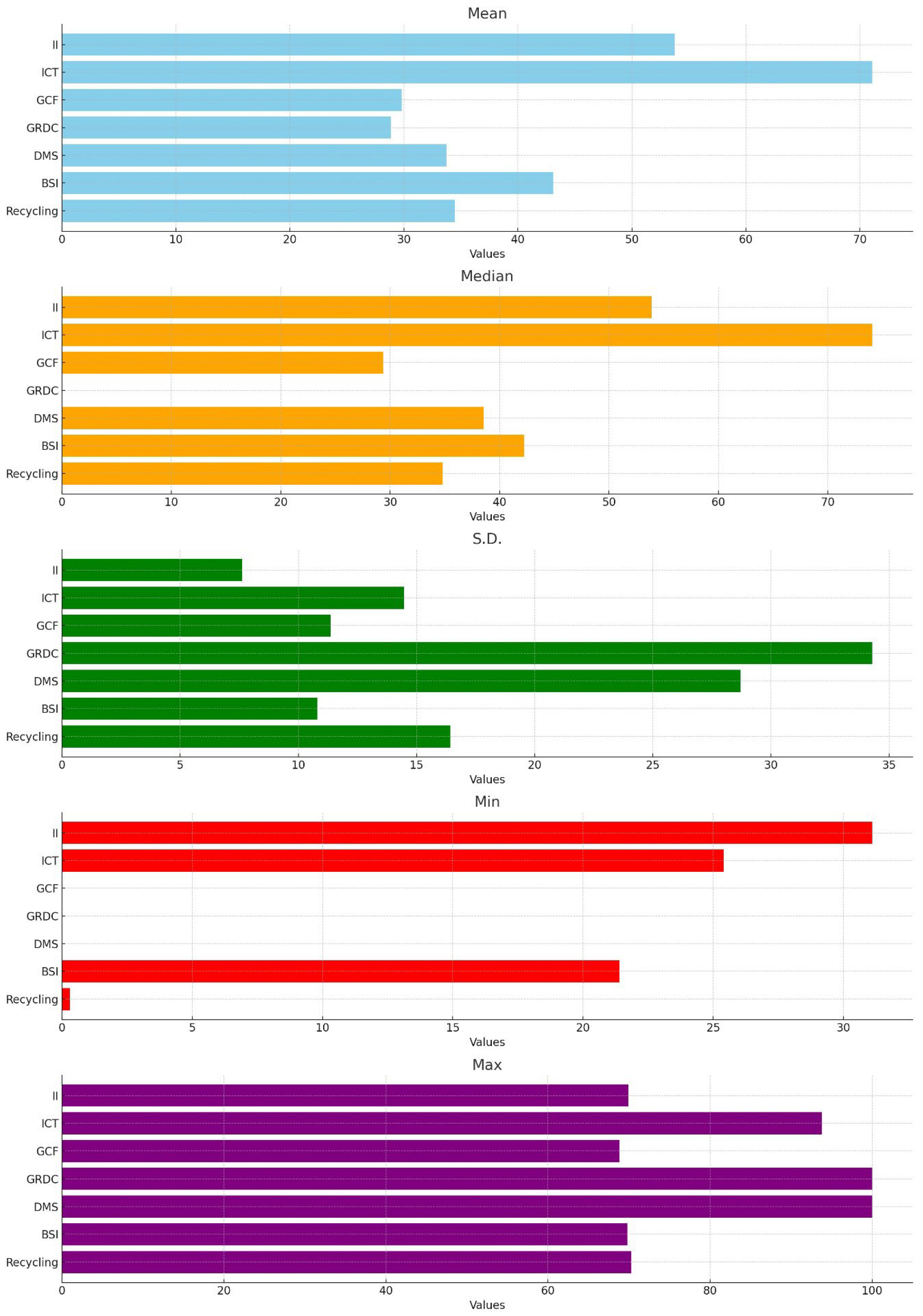

Descriptive Statistics. The dataset consists of seven relevant variables: Recycling, BSI, DMS, GRDC, GCF, ICT, and II. Mean values indicate that ICT (71.08) has the highest average score, followed by II (53.77) and BSI (43.10). Conversely, GRDC (28.86) and Recycling (34.48) have the lowest averages. Standard Deviation values reveal the variability within each category. GRDC exhibits the highest variability (34.28), indicating significant fluctuations in its data points. In contrast, II (7.632) and GCF (11.37) show the lowest variability, suggesting more consistent data. Moreover, variables like DMS and GRDC show a maximum value of 100.0, reflecting exceptional performance at their best instances, whereas categories like Recycling (70.30) and II (69.90) have more moderate maximum values. The high variability in GRDC suggests that this category could benefit from targeted interventions to improve consistency. ICT, with its high mean and median, represents a strong performer, but attention to maintaining this performance is crucial. The zero medians and minimum values in variables like GRDC and GCF indicate potential issues that need addressing to avoid underperformance (see

Figure 1).

4. Cluster Analysis

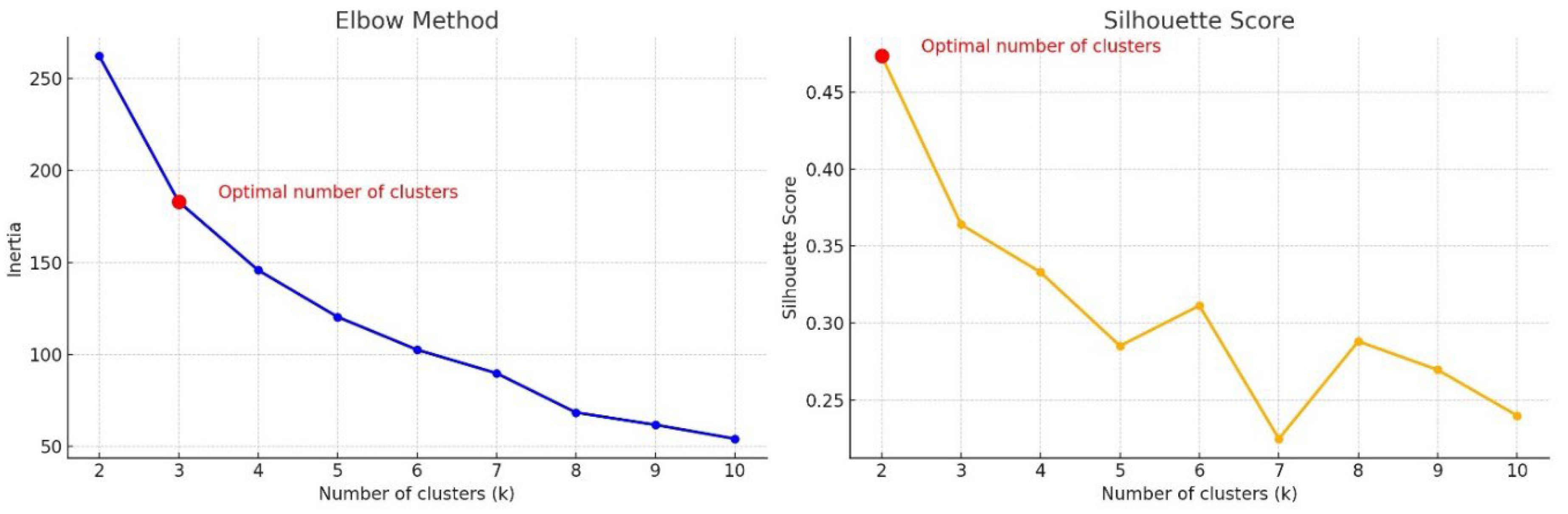

In this section, a clustering with the k-Means algorithm is proposed. Since the k-Means algorithm is unsupervised, it is necessary to identify tools capable of optimizing the number of clusters. In this case, we compare two methods, namely the Silhouette Coefficient and the Elbow Method. The Silhouette Coefficient identifies the number of Clusters in k=2. While, with the Elbow method, the optimal number of clusters is k=3. The choice of k=3 seems more appropriate as it allows us to better represent the differences between several different countries (

Figure 2).

From the cluster analysis, we have obtained three distinct clusters, each with its unique characteristics. These clusters are described in detail in what follows.

Cluster 0: Countries with moderate recycling rates. It includes Finland, Slovenia, Ireland, Norway, Spain, France, and Italy. These nations are characterized by their moderate recycling rates of municipal waste. This cluster represents countries that have made significant strides in recycling but still have room for improvement to reach the levels of the highest-performing nations. Finland has a well-established recycling system, particularly in urban areas. The country has implemented policies to reduce waste generation and promote recycling. However, Finland still faces challenges in rural areas where recycling infrastructure may not be as developed. The Finnish government continues to work towards improving recycling rates through public awareness campaigns and investing in recycling technologies. Slovenia has shown considerable progress in recent years, transitioning from a low recycling rate to becoming one of the better performers in its region. The implementation of robust waste management policies and community engagement initiatives has been pivotal. Despite these advances, Slovenia's recycling rates are moderate when compared to the top performers in Europe, indicating potential for further enhancement. Ireland's recycling efforts have grown significantly, particularly after the introduction of the Waste Management Act and the National Waste Prevention Programme. The country has improved its recycling infrastructure and public participation in recycling programs. Nevertheless, Ireland faces ongoing challenges such as the need for better waste segregation at the source and the reduction of landfill dependency. Norway is known for its environmental consciousness and has implemented various measures to boost recycling. The country has a deposit return system for bottles and cans, which has been highly successful. However, municipal waste recycling in Norway is moderate, partly due to high levels of waste incineration. Efforts are ongoing to enhance recycling rates and reduce incineration. Spain has made improvements in recycling, driven by EU regulations and national policies. There is significant variation in recycling rates across different regions of Spain, with some areas performing better than others. Overall, Spain's recycling rate is moderate, and there is potential to increase it further by harmonizing practices across all regions. France has implemented several initiatives to improve recycling rates, including extended producer responsibility (EPR) schemes and nationwide recycling programs. The country has seen gradual improvements in recycling performance. However, challenges remain in achieving higher recycling rates, particularly in densely populated urban areas where waste generation is high. Italy's recycling rates vary widely between regions, with the northern parts of the country performing much better than the southern regions. National efforts to standardize recycling practices and enhance public awareness are underway. Despite these efforts, Italy's overall recycling rate remains moderate, with significant potential for improvement. Cluster 0 represents countries with moderate recycling rates. These countries have established waste management systems and are making progress, but they still have areas that require attention to reach higher recycling performance levels. The countries in this cluster demonstrate a commitment to improving recycling but face specific challenges that need to be addressed through targeted policies, infrastructure investments, and public education campaigns. By continuing to focus on these areas, the countries in Cluster 0 can enhance their recycling rates and contribute more effectively to environmental sustainability and resource conservation (Kipperberg, 2007; Byrne and O’Regan, 2014; Kalčíková and Žgajnar Gotvajn, 2019; Qureshi et al., 2020).

Cluster 1: Leading countries with high recycling rates. It includes Belgium, Sweden, Austria, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Denmark, and Germany. These nations are characterized by their high recycling rates of municipal waste. This cluster represents countries that have achieved significant success in recycling, often setting benchmarks for others to follow. These countries are leaders in municipal waste recycling, with advanced waste management systems and robust policies that support high recycling rates. Belgium has one of the highest recycling rates in Europe, largely due to its efficient waste management policies and public participation. The country has implemented an EPR scheme, which places the onus on producers to manage the disposal of their products. Belgium also benefits from a well-organized curbside collection system and advanced sorting facilities. Public awareness campaigns and strict regulations have further bolstered recycling efforts, making Belgium a model for other countries. Sweden is renowned for its comprehensive waste management system, which includes an extensive recycling infrastructure and a strong focus on waste-to-energy conversion. The country's deposit-return scheme for beverage containers has been particularly successful. Sweden's approach to recycling includes a high level of public engagement, with citizens actively participating in waste separation at the source. The government continuously invests in new technologies to improve recycling efficiency and reduce environmental impact. Austria consistently ranks among the top countries in Europe for recycling rates. The country's success can be attributed to its stringent waste management laws, efficient recycling programs, and high public awareness. Austria has an effective collection system for various types of waste, including organic waste, which is composted or used for biogas production. The government's commitment to environmental sustainability has fostered a culture of recycling that permeates all levels of society. The Netherlands is a pioneer in waste management, with an impressive recycling rate supported by a well-developed infrastructure. The country has adopted a circular economy approach, focusing on reducing waste and promoting the reuse of materials. The Dutch government has implemented policies that encourage recycling and discourage landfill use through high landfill taxes. Advanced waste sorting facilities and innovative recycling technologies have helped the Netherlands maintain its position as a leader in municipal waste recycling. Luxembourg, despite its small size, has achieved remarkable success in recycling. The country has implemented comprehensive waste management strategies that include recycling, composting, and waste-to-energy processes. Public participation is high, thanks to effective awareness campaigns and convenient recycling facilities. Luxembourg's government continues to invest in improving recycling infrastructure and promoting sustainable waste management practices. Switzerland boasts one of the highest recycling rates globally, with a well-organized waste management system that includes recycling, composting, and incineration with energy recovery. The Swiss government has implemented strict regulations that mandate recycling for various materials, supported by a strong public awareness campaign. The country's efficient collection systems and state-of-the-art sorting facilities ensure high recycling performance. Denmark is another top performer in waste recycling, with a comprehensive waste management system that emphasizes recycling and energy recovery. The country has invested heavily in waste-to-energy plants, which convert non-recyclable waste into energy. Denmark's recycling programs are supported by strong public participation and government policies that promote sustainability. The country continuously seeks to innovate and improve its waste management practices. Germany is often considered a global leader in recycling, with one of the highest recycling rates in the world. The country's success is built on its strict waste management regulations, advanced recycling technologies, and robust public participation. Germany's dual system for packaging waste, which separates the collection and recycling processes, has been particularly effective. The government's commitment to a circular economy has driven continuous improvements in recycling practices. Cluster 1 represents countries with high recycling rates. These countries are leaders in municipal waste recycling, characterized by advanced waste management systems, robust policies, and high levels of public participation. The nations in this cluster have implemented comprehensive waste management strategies that include recycling, composting, and waste-to-energy processes. Their success serves as a benchmark for other countries striving to improve their recycling rates. The continued investment in recycling infrastructure, innovation in waste management technologies, and effective public awareness campaigns have ensured that these countries remain at the forefront of global recycling efforts. By maintaining their commitment to sustainability and continuously improving their practices, the countries in Cluster 1 set a high standard for environmental stewardship and resource conservation (Dijkgraaf and Gradus, 2017; Van Eygen et al., 2018; Warrings and Fellner, 2021; Picuno et al., 2021).

Cluster 2: Countries with lower recycling rates. It includes Iceland, Bulgaria, Czechia, Slovakia, Romania, Latvia, Poland, Estonia, Malta, Hungary, Greece, Lithuania, Cyprus, and Portugal. These nations might be facing significant challenges in waste management and consequently have lower performance in recycling municipal waste compared to their peers. Iceland, despite its commitment to environmental sustainability, faces unique challenges in waste management due to its geographic isolation and small population. Recycling rates in Iceland are relatively low, partly because the country has to export most recyclable materials, which incurs high costs. Additionally, the infrastructure for waste sorting and recycling is still developing, although there is a strong national commitment to improve these systems. Bulgaria has struggled with low recycling rates, primarily due to inadequate infrastructure and a lack of public awareness. The country is working to align its waste management practices with EU standards, but progress has been slow. Efforts to increase recycling rates include implementing new waste management policies and investing in recycling facilities, but substantial improvements are still needed. Czechia has made some progress in recent years, but its recycling rates remain lower than the EU average. The country faces challenges such as insufficient recycling infrastructure and limited public participation in recycling programs. Initiatives to improve waste management practices are underway, focusing on increasing recycling capacity and enhancing public education about the importance of recycling. Slovakia’s recycling rates are relatively low, and the country faces challenges similar to those of other Eastern European nations. Limited infrastructure, lack of incentives for recycling, and insufficient public awareness contribute to these low rates. Slovakia is working on improving its waste management system through various reforms and investments, aiming to boost recycling rates and reduce landfill dependency. Romania is one of the countries with the lowest recycling rates in the EU. Challenges include inadequate infrastructure, lack of effective waste management policies, and low public awareness. The Romanian government has been taking steps to improve the situation by introducing new regulations and investing in recycling facilities, but significant progress is still required to achieve higher recycling rates. Latvia faces several obstacles in improving its recycling rates, including limited infrastructure and public participation. The country has been focusing on enhancing its waste management practices by implementing new policies and increasing investments in recycling technologies. However, these efforts are still in the early stages, and much work remains to be done. Poland has a relatively low recycling rate, facing challenges such as inadequate infrastructure and insufficient public awareness. The country is working to improve its waste management system through legislative reforms and investments in recycling facilities. Poland aims to align its practices with EU standards, but achieving significant improvements will take time and sustained effort. Estonia’s recycling rates are low, primarily due to limited infrastructure and public engagement in recycling programs. The government is focusing on improving waste management practices and increasing public awareness about recycling. Investments in recycling facilities and new policies are expected to boost recycling rates in the coming years. Malta faces unique challenges in waste management due to its small size and high population density. Recycling rates are relatively low, and the country struggles with limited space for waste processing facilities. Malta is working on improving its waste management system by investing in new technologies and promoting public awareness campaigns. Hungary has made some progress in waste management, but its recycling rates remain low compared to other EU countries. Challenges include insufficient infrastructure and public participation in recycling programs. The Hungarian government is implementing new policies and investing in recycling facilities to improve recycling rates. Greece has relatively low recycling rates, facing challenges such as inadequate infrastructure and limited public engagement in recycling programs. The country is working on improving its waste management system through legislative reforms and investments in recycling technologies. Public awareness campaigns are also being conducted to encourage more participation in recycling. Lithuania’s recycling rates are low, with challenges including limited infrastructure and public awareness. The country is focusing on enhancing its waste management practices through new policies and investments in recycling facilities. Public education campaigns are also being conducted to increase participation in recycling programs. Cyprus faces challenges in improving its recycling rates, including inadequate infrastructure and low public awareness. The government is working on implementing new waste management policies and investing in recycling technologies. Public awareness campaigns are also being conducted to encourage more participation in recycling. Portugal’s recycling rates are relatively low, with challenges including insufficient infrastructure and public engagement. The country is working on improving its waste management system through legislative reforms and investments in recycling facilities. Public education campaigns are also being conducted to increase participation in recycling programs. Cluster 2 represents countries with lower recycling rates. These countries face significant challenges in waste management, including inadequate infrastructure, lack of effective policies, and low public awareness. Efforts are being made to improve recycling rates in these nations through new policies, investments in recycling facilities, and public education campaigns. However, substantial progress is still required to achieve higher recycling rates and align with the performance of leading countries. By addressing these challenges and continuing to invest in waste management improvements, the countries in Cluster 2 can enhance their recycling rates and contribute to environmental sustainability (Stoeva and Alriksson, 2017; Rybova, 2019; Mager et al., 2022; Šimková and Bednárová, 2022).

In summary, while the countries in Cluster 1 serve as exemplars of excellence and set a benchmark for others to aspire to, the countries in Cluster 0 and Cluster 2 reveal that there is still significant room for improvement. Cluster 1 nations, such as Belgium, Sweden, and Germany, have established themselves as leaders in municipal waste recycling through advanced waste management systems, robust policies, and high levels of public participation. These countries not only demonstrate the feasibility of achieving high recycling rates but also provide valuable insights and best practices that can guide other nations in their efforts to enhance recycling performance. On the other hand, countries in Cluster 0, including Finland, Slovenia, and Ireland, have made considerable progress but still face specific challenges that need to be addressed. For instance, while Finland boasts a well-established recycling system in urban areas, it struggles with underdeveloped infrastructure in rural regions. Similarly, Ireland and Slovenia have improved their recycling rates through effective waste management policies and community engagement, yet they need to enhance waste segregation at the source and reduce their dependency on landfills. Countries in Cluster 2, such as Iceland, Bulgaria, and Romania, are at the beginning of their journey towards effective waste management and face more significant obstacles. These include inadequate infrastructure, limited public awareness, and less effective waste management policies. However, these countries are actively working towards aligning their practices with EU standards by implementing new regulations, investing in recycling facilities, and conducting public education campaigns. Continuous investments in recycling infrastructure, targeted policies, and comprehensive public awareness campaigns are crucial for all countries to improve their recycling rates. By focusing on these areas, nations can significantly enhance their waste management systems. This, in turn, will contribute more effectively to environmental sustainability and resource conservation, ultimately fostering a more sustainable future for all. Through collective efforts and shared knowledge, countries can bridge the gap between current practices and the desired state of high recycling performance, ensuring that environmental stewardship becomes a global priority.

5. Panel Data Estimates

This section reports the results of panel data models to estimate the level of recycling of municipal waste with respect to the characteristics of innovation systems in the European context. The econometric analysis is conducted through the application of the Fixed Effects (FE) and Random Effects (RE) models. The following equation was estimated:

where i = 34 and t = 2013,…, 2022.

Positive relationship between Recycling and DMS. In Europe, the positive relationship between the recycling rate of municipal waste and the domestic market scale, measured in billion purchasing power parity dollars (PPP$), is clearly evident. This relationship can be analyzed through the intertwined economic, environmental, and social dimensions that contribute to the continent’s sustainable development and economic prosperity. Economically, Europe’s large domestic markets, characterized by high consumption levels, have significantly benefited from robust recycling practices. The EU has set ambitious targets for waste management, leading to substantial investments in recycling infrastructure. Countries like Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden, which have some of the highest recycling rates globally, also possess strong domestic markets. These nations have invested in advanced recycling technologies, creating efficient systems that convert waste into valuable resources. This not only reduces the need for raw material imports but also stabilizes supply chains, ensuring a steady supply of materials for industries. By fostering a circular economy, these countries enhance their economic resilience and competitiveness, reducing production costs and driving economic growth. Environmentally, Europe’s commitment to recycling has yielded significant benefits, reinforcing the positive relationship with market scale. High recycling rates reduce landfill usage and lower greenhouse gas emissions, contributing to the EU’s goals for climate neutrality. The environmental benefits of high recycling rates contribute to healthier ecosystems, which are crucial for sustainable economic activities. A cleaner environment supports tourism, agriculture, and other industries dependent on natural resources, thus expanding the domestic market scale. Furthermore, the EU’s emphasis on sustainability attracts global investors and consumers who prioritize environmental responsibility, boosting Europe’s market attractiveness. Socially, Europe’s high recycling rates have positively impacted public health and community well-being, further strengthening the domestic market. Effective waste management reduces pollution, leading to cleaner air and water, which in turn lowers healthcare costs and enhances the quality of life. This creates a more productive and stable workforce, essential for economic growth. Public awareness campaigns and education on recycling have fostered a culture of sustainability across Europe. Citizens are more conscious of their consumption patterns, supporting local markets and sustainable products. This societal shift not only drives demand for green products but also encourages businesses to adopt eco-friendly practices, promoting innovation and economic development. Moreover, European policies and regulations play a crucial role in reinforcing the positive relationship between recycling rates and market scale. The EU’s legislative framework incentivizes businesses to engage in recycling and use recycled materials, providing financial benefits such as tax breaks and subsidies. These policies stimulate economic activity by reducing operational costs for businesses and encouraging innovation in recycling technologies. For example, the European Green Deal aims to transform the EU into a modern, resource-efficient economy with no net emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050. Such initiatives attract investments in green technologies and sustainable industries, further expanding the domestic market (Pomberger et al., 2017; Sastre et al., 2018; Abis et al., 2020).

Positive relationship between Recycling and GCF. The positive relationship between the recycling rate of municipal waste and GCF as a percentage of GDP in Europe is a compelling illustration of how environmental sustainability and economic growth can be mutually reinforcing. This relationship can be explored through the lenses of economic efficiency, resource utilization, and policy impacts. In Europe, the recycling rate of municipal waste is a critical indicator of the region's commitment to sustainable development. High recycling rates signify efficient waste management systems, which directly impact GCF. GCF, encompassing investments in infrastructure, machinery, and technology, benefits significantly from robust recycling practices. When municipal waste is effectively recycled, it reduces the need for raw materials, lowering production costs for businesses. This cost reduction can lead to increased profitability and, consequently, higher levels of reinvestment in capital goods. For instance, European countries with high recycling rates, such as Germany and Sweden, demonstrate significant investments in advanced recycling technologies and infrastructure, fueling further economic growth. Moreover, high recycling rates contribute to the circular economy, a model that emphasizes the reuse, refurbishment, and recycling of materials. This economic model aligns with the principles of GCF by promoting sustainable investments. In a circular economy, materials recovered from municipal waste are reintegrated into the production process, reducing dependency on finite natural resources. This not only conserves resources but also drives innovation and technological advancements, as businesses invest in new methods to recycle and reuse materials more efficiently. These innovations often require substantial capital investments, thereby boosting GCF. The environmental benefits of high recycling rates also support economic stability and growth, essential for sustained capital formation. By reducing landfill use and lowering greenhouse gas emissions, recycling mitigates environmental risks that can lead to economic disruptions. For example, climate change-induced weather events can damage infrastructure and disrupt supply chains, necessitating significant capital expenditure for repairs and adaptations. Effective recycling reduces these risks, creating a more stable economic environment conducive to long-term investments. Furthermore, European policies aimed at increasing recycling rates directly influence GCF. Compliance with these regulations often requires significant capital investments from both public and private sectors. Governments invest in waste management infrastructure, while businesses invest in technologies and processes to comply with regulations. These investments are reflected in GCF as a percentage of GDP, showcasing the direct link between recycling rates and capital formation. Additionally, the recycling industry itself is a substantial contributor to GCF. The development and expansion of recycling facilities, the creation of new technologies for waste processing, and the establishment of markets for recycled materials all require significant capital investment. In Europe, the recycling sector has grown considerably, driven by both policy incentives and market demand for sustainable products. This growth translates into increased capital formation as the industry invests in expanding its capabilities and improving efficiency. Social and economic benefits derived from high recycling rates also play a role in enhancing GCF. High recycling rates lead to job creation in the recycling and waste management sectors, improving employment rates and economic stability. Increased employment and economic stability boost consumer confidence and spending, further stimulating economic growth and encouraging businesses to invest in capital goods. In conclusion, the positive relationship between the recycling rate of municipal waste and GCF as a percentage of GDP in Europe is evident through multiple channels. Efficient recycling practices lower production costs, promote resource conservation, drive innovation, and foster a stable economic environment. European policies aimed at increasing recycling rates necessitate substantial capital investments, further boosting GCF. The recycling industry itself contributes significantly to capital formation, illustrating how sustainable practices can drive economic growth. Thus, high recycling rates are integral to fostering a sustainable and robust economy in Europe, exemplifying the synergy between environmental sustainability and economic development (Gardiner and Hajek, 2017; Šimková and Bednárová, 2022; Datsyuk et al., 2023, Azwardi et al., 2023; Traven et al., 2023).

Positive relationship between Recycling and ICT. The positive relationship between the recycling rate of municipal waste and ICTs in Europe is evident through various economic, environmental, and social dimensions. The integration of ICT into waste management practices has led to significant improvements in recycling rates across European countries, demonstrating a clear and beneficial connection between these two domains. Firstly, ICT enhances the efficiency and effectiveness of recycling programs. In Europe, advanced ICT systems are employed to manage and monitor waste collection, sorting, and processing. Smart bins equipped with sensors can detect when they are full and signal for collection, optimizing collection routes and reducing fuel consumption and emissions. This not only lowers operational costs but also ensures that recyclable materials are collected promptly, preventing contamination and improving the overall quality of recycled materials. For instance, cities like Amsterdam and Barcelona have implemented such smart waste management systems, leading to higher recycling rates and more efficient waste processing. Moreover, ICT facilitates better data collection and analysis, which is crucial for improving recycling rates. European municipalities leverage data analytics to track waste generation patterns, identify areas with low recycling participation, and develop targeted awareness campaigns. By analyzing data from various sources, including smart bins, collection trucks, and recycling facilities, authorities can make informed decisions to enhance recycling strategies. This data-driven approach has been instrumental in increasing recycling rates in many European countries, as it allows for more precise and effective waste management policies. ICT also plays a significant role in raising public awareness and engagement in recycling activities. Mobile apps and online platforms provide residents with information on how to recycle correctly, the location of recycling centers, and collection schedules. These tools make it easier for citizens to participate in recycling programs, thereby increasing recycling rates. In countries like Germany and Sweden, the use of digital platforms to educate and engage the public has contributed to their high recycling rates. Furthermore, social media campaigns and digital initiatives help spread awareness about the environmental benefits of recycling, fostering a culture of sustainability. The integration of ICT into recycling processes also encourages innovation in waste management technologies. European companies are at the forefront of developing cutting-edge recycling technologies, such as automated sorting systems that use artificial intelligence and machine learning to accurately separate different types of recyclable materials. These technologies increase the efficiency and accuracy of recycling operations, reducing the amount of waste sent to landfills and enhancing the recovery of valuable materials. This innovation is supported by a strong ICT infrastructure, which provides the necessary tools and platforms for research and development in the recycling industry. Additionally, ICT enables better coordination and collaboration among various stakeholders in the recycling ecosystem. Governments, waste management companies, and recyclers can share information and resources more effectively through digital platforms, leading to more cohesive and integrated recycling programs. This collaborative approach is evident in European countries where public-private partnerships and cross-border collaborations have been successful in improving recycling rates. The EU’s circular economy initiatives, supported by ICT, have fostered cooperation among member states, driving advancements in recycling technologies and practices across the continent (Malinauskaite et al., 2017; Castillo-Giménez, 2019; Magazzino et al., 2021a).

Negative relationship between Recycling and BSI. In examining the relationship between the recycling rate of municipal waste and the Business Sophistication Index in Europe, one might argue that a negative correlation exists due to several underlying economic, infrastructural, and policy-related factors. Firstly, the Business Sophistication Index measures the quality of a country’s overall business networks and the quality of operations and strategies of companies within it. Higher levels of business sophistication often require substantial investment in innovation, technology, and efficient business practices. However, these investments might not always align with high recycling rates. For instance, in highly sophisticated business environments, companies might prioritize profitability and technological advancements that do not necessarily include sustainable waste management practices. High business sophistication can sometimes lead to greater production of complex and non-recyclable waste due to advanced manufacturing processes and the use of specialized materials that are challenging to recycle. Secondly, in many European countries with high business sophistication, the focus on rapid industrial and economic growth can overshadow environmental considerations like recycling. Businesses driven by innovation and competitiveness may prioritize cost reduction and efficiency over-investment in comprehensive recycling programs. This is especially relevant in highly competitive industries where margins are slim, and the emphasis is on rapid product turnover and consumption. Consequently, businesses might opt for cheaper disposal methods rather than investing in recycling, particularly if the regulatory framework does not mandate or incentivize high recycling rates. Furthermore, the negative relationship can also be attributed to the disparity in regulatory environments across Europe. In some countries with high business sophistication, regulations may not be stringent enough to enforce high recycling rates. Businesses operating in such environments might lack the necessary regulatory push to implement effective recycling practices. Additionally, sophisticated businesses might leverage their influence to lobby against stringent recycling regulations, viewing them as potential obstacles to their operational efficiency and profitability. Another contributing factor is the complexity of recycling advanced materials used in sophisticated industries. High-tech industries, prevalent in regions with high business sophistication, often use materials that are difficult to recycle due to their composite nature or hazardous components. For instance, electronic waste, which is prevalent in highly developed business environments, poses significant recycling challenges. The lack of suitable recycling technology for these materials can lead to lower overall recycling rates, despite the presence of sophisticated business operations. Moreover, high business sophistication often correlates with a consumer culture that favors frequent product upgrades and replacements, leading to higher waste generation. This consumer behavior, driven by marketing and innovation cycles, results in an increased volume of waste that is difficult to manage effectively through recycling alone. For example, the fashion and electronics industries, both highly sophisticated, generate substantial waste that is not easily recyclable due to the rapid turnover of products. In conclusion, the negative relationship between the recycling rate of municipal waste and the Business Sophistication Index in Europe can be attributed to several factors. These include a focus on profitability and innovation over sustainability, inadequate regulatory frameworks, the complexity of recycling advanced materials, and consumer behaviors driven by rapid product turnover. While business sophistication brings numerous economic benefits, it can also create challenges for achieving high recycling rates (Halkos and Petrou, 2019; Giannakitsidou et al., 2020; Sauve and Van Acker, 2020; Bayar et al., 2021; Valenćiková and Fandel, 2023).

The negative relationship between Recycling and GRDC. In the context of Europe, the relationship between the recycling rate of municipal waste and the average expenditure of the top three global R&D companies presents several negative aspects that warrant consideration. This negative relationship can be attributed to economic, strategic, and operational factors that influence both waste management policies and corporate R&D investment decisions. Economically, high recycling rates in Europe can lead to increased operational costs for global R&D companies. These companies often prioritize cost efficiency to maximize their research budgets and foster innovation. However, stringent recycling regulations in Europe can impose additional costs on businesses, particularly those in the manufacturing and technology sectors. Compliance with recycling mandates requires substantial investment in waste management systems, recycling technologies, and regulatory reporting. These expenses can divert funds away from R&D activities, reducing the overall expenditure available for innovation. Consequently, global R&D companies may perceive Europe’s high recycling rates as a financial burden, potentially discouraging them from expanding their operations or investing heavily in the region. Strategically, the focus on high recycling rates in Europe can shift corporate priorities away from R&D innovation. European governments often emphasize environmental sustainability and circular economy principles, leading to policies prioritizing waste reduction and recycling. While these policies are essential for environmental protection, they can inadvertently divert attention and resources from R&D initiatives. Companies may allocate more resources to meeting recycling targets and compliance requirements rather than investing in cutting-edge research and development. This shift in strategic focus can hinder the growth of R&D activities as companies prioritize regulatory compliance over innovation-driven projects. Operationally, the complexity of managing high recycling rates can pose challenges for global R&D companies in Europe. The intricate logistics of sorting, collecting, and processing recyclable materials require specialized infrastructure and expertise. Global R&D companies, especially those with extensive operations across multiple regions, may struggle to adapt to Europe’s stringent recycling standards. The operational burden of implementing comprehensive recycling programs can strain corporate resources, leading to inefficiencies and reduced productivity. As a result, companies may experience operational disruptions that negatively impact their R&D efforts, as resources are diverted to manage recycling logistics rather than research initiatives. Furthermore, the negative relationship between recycling rates and R&D expenditure is evident in the competitive landscape of the global market. Europe’s stringent recycling regulations can create a challenging business environment for global R&D companies, making it less attractive compared to regions with more lenient waste management policies. Companies may opt to relocate their R&D operations to regions with lower regulatory burdens, where they can allocate more resources to innovation rather than compliance. This relocation can lead to a decline in Europe’s attractiveness as a hub for R&D investment, further exacerbating the negative relationship between recycling rates and R&D expenditure. Additionally, the emphasis on high recycling rates in Europe can lead to regulatory uncertainties that deter R&D investment. Frequent changes in recycling policies, varying regulations across European countries, and the complexity of compliance can create an unpredictable business environment. Global R&D companies, which thrive on stability and predictability, may view these uncertainties as risks to their investment strategies. As a result, they may reduce their R&D expenditure in Europe, opting for regions with more stable regulatory frameworks. The negative relationship between the recycling rate of municipal waste and the average expenditure of the top three global R&D companies in Europe is driven by economic, strategic, and operational factors. The financial burden of compliance, the shift in corporate priorities, operational complexities, competitive disadvantages, and regulatory uncertainties all contribute to this negative dynamic (Troschinetz and Mihelcic, 2009; Bartolacci et al., 2018; Colangelo et al., 2020; Khomenko et al., 2023).

Negative relationship between Recycling and II. In Europe, the relationship between the recycling rate of municipal waste and the infrastructure index can be argued to be negative due to several factors. Despite the continent’s general reputation for environmental consciousness and advanced infrastructure, various nuances highlight a paradoxical scenario where higher recycling rates are sometimes inversely related to infrastructure quality. Firstly, high recycling rates in Europe often stem from stringent environmental policies and societal behaviors rather than the quality of physical infrastructure. Countries like Germany and Sweden boast high recycling rates due to strong governmental regulations and public adherence to recycling norms. However, these high recycling rates do not necessarily correlate with superior infrastructure. In some cases, older infrastructure systems are still in use but are supplemented by robust public participation and effective policy frameworks. Thus, the recycling success can be attributed more to regulatory and social factors than to the infrastructure index. Economically, the development of recycling infrastructure can sometimes divert resources from other critical infrastructural projects. European countries with limited budgets may prioritize recycling initiatives due to EU mandates and environmental goals, potentially neglecting broader infrastructure development like transportation, energy, or digital networks. This diversion can lead to an infrastructure index that does not fully reflect the country's recycling capabilities. For example, while Italy has made significant strides in increasing its recycling rates, its broader infrastructure, particularly in the southern regions, remains underdeveloped. The focus on meeting EU recycling targets can strain financial resources, leaving other infrastructural areas lagging. Moreover, the complexity and high costs associated with modern recycling facilities can present challenges. Advanced recycling plants require significant investment, specialized technology, and continuous maintenance. For countries with already strained infrastructure budgets, this can lead to a scenario where recycling rates improve at the expense of other infrastructure development. For instance, Eastern European countries like Bulgaria and Romania have made improvements in recycling rates due to EU funding and directives. However, their overall infrastructure indices remain low, reflecting broader infrastructural deficiencies that high recycling rates cannot mitigate. From an operational perspective, the efficiency of recycling programs can sometimes reveal underlying infrastructure issues. High recycling rates necessitate efficient collection, sorting, and processing systems. In some European countries, achieving high recycling rates involves compensating for infrastructural inefficiencies through increased labor or lower-tech solutions, which might not be reflected in the infrastructure index. For example, Greece has seen improvements in recycling rates through community-driven initiatives and informal recycling sectors rather than through modernized infrastructure, indicating a potential negative relationship between recycling success and overall infrastructure quality. Additionally, the focus on improving recycling rates can sometimes overshadow the need for comprehensive waste management infrastructure. High recycling rates may lead to the assumption that the waste management system is efficient, potentially masking deficiencies in other areas such as waste-to-energy facilities or landfill management. This can result in a skewed perception of infrastructure quality, where high recycling rates give a false sense of overall infrastructure robustness. Spain, for example, has improved its recycling rates significantly, but still faces challenges in waste management infrastructure that are not captured by recycling statistics alone. Lastly, the urban-rural divide in Europe can exacerbate the negative relationship between recycling rates and the infrastructure index. Urban areas with better waste management systems and higher recycling rates often contrast sharply with rural areas that lack such infrastructure. This disparity can lead to an overall infrastructure index that does not align with the recycling achievements of urban centers. Countries like Poland exhibit this divide, where metropolitan areas show high recycling rates while rural regions struggle with basic waste management infrastructure. While Europe showcases impressive recycling rates, the relationship between these rates and the infrastructure index is complex and often negative. Factors such as economic resource allocation, operational challenges, policy-driven successes, and urban-rural disparities contribute to this paradox. High recycling rates, driven by stringent regulations and societal behaviors, do not necessarily equate to superior infrastructure, highlighting the nuanced and sometimes contradictory nature of this relationship in Europe (Grazhdani, 2016; Soukiazis and Proença, 2020; Ríos and Picazo-Tadeo, 2021; Pantcheva and Mengov, 2022).

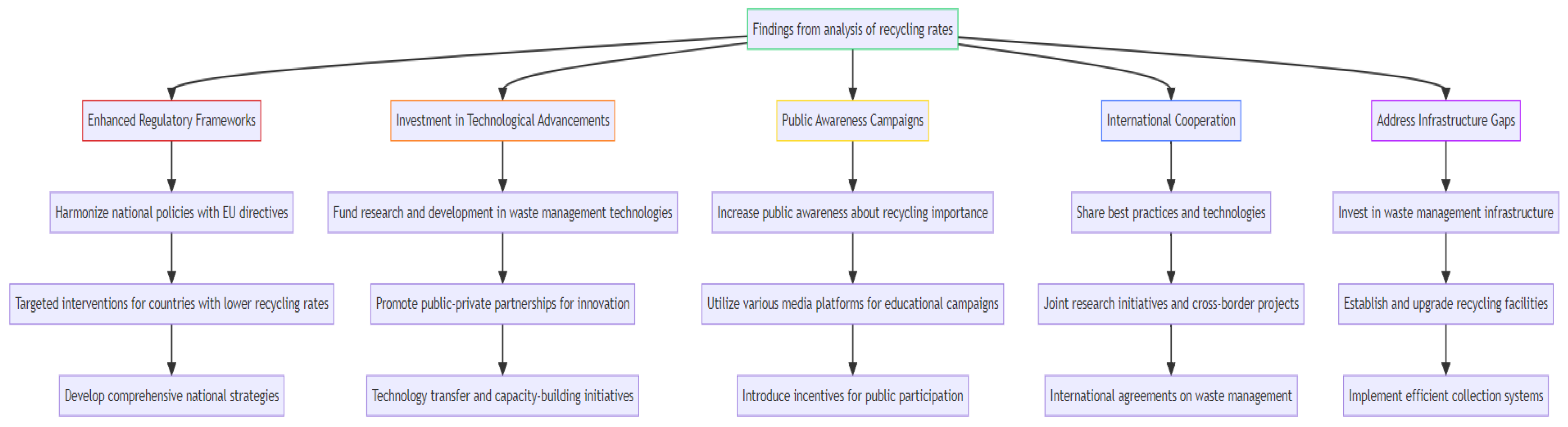

6. Policy Implications

Our findings highlight several critical policy implications. These implications address the need for enhanced regulatory frameworks, investment in technological advancements, public awareness campaigns, and international cooperation to improve recycling rates and waste management practices in Europe. However, the effectiveness of these policies varies significantly across member states. To bridge this gap, it is essential to harmonize national policies with EU directives, ensuring consistency and coherence in waste management practices. Countries with lower recycling rates, such as Bulgaria and Romania, need targeted interventions to align their waste management systems with EU standards. This can be achieved by developing comprehensive national strategies that include stringent recycling mandates, incentives for compliance, and penalties for non-compliance. Additionally, periodic review and adjustment of these policies will ensure they remain relevant and effective in addressing emerging waste management challenges (Banacu et al., 2019; Taušová et al., 2019).

Technological innovation is a critical driver of improved recycling rates. Countries with advanced waste management technologies, such as Germany, Sweden, and the Netherlands, exhibit higher recycling rates. Therefore, increasing investment in technology is imperative for enhancing recycling performance across Europe. Governments should allocate funds to R&D in waste management technologies. This includes the development of automated sorting systems, smart waste bins, and data analytics tools that optimize waste collection and processing. Public-private partnerships can play a relevant role in fostering innovation by combining governmental support with private sector expertise and resources. Moreover, countries with lower recycling rates can benefit from technology transfer and capacity-building initiatives. For instance, successful models from high-performing countries can be adapted and implemented in countries with underdeveloped waste management systems. This not only enhances recycling rates but also promotes technological parity across Europe (Sarc et al., 2019; Borchard et al, 2022).

Public awareness and participation are pivotal to the success of recycling programs. High recycling rates in countries like Germany and Sweden are partly attributed to strong public engagement and awareness campaigns. Therefore, increasing public awareness about the importance of recycling and how to participate effectively is crucial. Educational campaigns should be tailored to address specific local contexts and cultural attitudes towards waste. Utilizing various media platforms, including social media, television, and community outreach programs, can help disseminate information widely. Additionally, incorporating recycling education into school curricula can instill sustainable practices from a young age. Governments can also introduce incentives to encourage public participation. For example, deposit-return schemes for beverage containers have proven successful in several European countries. Similar initiatives can be expanded to other recyclable materials to motivate citizens to recycle more consistently (Stoeva and Alriksson, 2017; Mahapatra et al., 2021).

Infrastructural inadequacies are a significant barrier to effective waste management, particularly in countries with lower recycling rates. Ensuring that all regions, including rural and underserved areas, have access to adequate recycling infrastructure is essential. Investments in waste management infrastructure should focus on establishing and upgrading recycling facilities, collection centers, and sorting plants. Governments can provide financial assistance and subsidies to municipalities and private entities to build and maintain these facilities. Additionally, implementing efficient collection systems, such as curbside recycling and community drop-off points, can enhance accessibility and convenience for residents. The transition to a circular economy is integral to achieving sustainable waste management. This approach emphasizes reducing waste generation, reusing materials, and recycling resources to create a closed-loop system. Policies promoting circular economy practices can significantly enhance recycling rates and resource efficiency. Governments should encourage businesses to adopt circular economy models by providing incentives for sustainable practices and green innovation. This can include tax breaks, grants, and subsidies for companies that prioritize resource conservation and waste reduction in their operations. Additionally, implementing EPR schemes, where producers are accountable for the entire lifecycle of their products, can drive industry-wide changes towards sustainability (DiGiacomo et al., 2018; Hage et al., 2018).

Waste management is a global challenge that requires international cooperation and collaboration. European countries can benefit from sharing best practices, technologies, and policy approaches to improve recycling rates collectively. The EU can play a pivotal role in facilitating this cooperation by establishing platforms for dialogue and knowledge exchange among member states. Joint research initiatives and cross-border projects can help address common challenges and develop innovative solutions. For example, collaborative efforts to develop standardized recycling technologies and processes can ensure consistency and efficiency across Europe. Furthermore, international agreements and treaties on waste management can enhance regulatory alignment and prevent illegal waste exports and dumping. Continuous monitoring and evaluation of recycling policies and practices are essential to ensure their effectiveness and identify areas for improvement. Governments should establish comprehensive data collection and reporting systems to track recycling rates, waste generation, and the impact of various initiatives. Regular audits and assessments can provide valuable insights into the performance of waste management programs and highlight successful strategies that can be scaled up or replicated. Additionally, engaging independent bodies and experts in the evaluation process can ensure transparency and objectivity (Malinauskaite et al., 2017; Ziglio and Ribeiro, 2019).

The policy implications derived from the analysis of recycling rates and technological innovation in European waste management underscore the need for a multifaceted approach. Strengthening regulatory frameworks, investing in technological advancements, enhancing public awareness, addressing infrastructure gaps, promoting circular economy practices, facilitating international cooperation, and implementing robust monitoring and evaluation mechanisms are all crucial steps towards achieving higher recycling rates and sustainable waste management in Europe (see

Figure 3).

7. Conclusions