1. Introduction

Social, cultural, and traditional forces are constantly housed in urban forms, and these forces ultimately define the basic spatial characteristics of the city. Historic cities are those that preserve their memories with minimal effort. These cities, which developed from natural settings, also include specific physical surroundings made up of manufactured artefacts. The privacy of the adjacent users determines the internal spaces whereas the public life ambivalently defines the outdoor regions such as streets and the periphery. Since these elements do not exist in isolation, their comprehension is frequently overlooked. The distinct nature of these places emerges spontaneously with the appearance of a group of architectural components: the thresholds (1).

The phrase “threshold” refers to the ambiguity between opening and closure. "Space" refers to architectural dimensions as determined by a person’s physical experience in motion and perception. “Threshold space” is a compound noun that depicts a spatial or temporal transitory state that is utilized in a variety of professions. In architectural designs they serve as access to adjacent rooms; in many situations, they also serve as the entryway (2). It is a point at which one space transitions into another. Threshold spaces live on signaling the impending spatial experience; in other words, such a space thrives in anticipation of progress.

From the beginning of time, a space for shelter was considered inside and a natural environment outside (3). The threshold space is a transition place that can be located between inside and outside, between multiple interior spaces, or fully outside (4). The threshold, forming a permeable boundary along the street edge, bridged the public realm with the private home. The constant street activity would flow into this space and vice versa, turning the threshold space into a catalyst for public engagement while keeping the lively street just a step away from the sheltered interiors. The sounds and smells of people’s movements were shared between the public and semi-public areas. Pritzker laureate B.V. Doshi described verandas as “the meeting place between the sacred and profane; the house and the street.” The mysticism of the in-between is a recurring theme in Indian philosophy. The threshold space receives special attention every morning through worship and decoration, especially during festivities. It was also a space to extend hospitality, where neighbors and passers-by could stop for spontaneous conversation. The threshold formed an integral part of traditional houses, celebrating the culture of generosity and community. Legally, this area belonged to the owner of the dwelling. Socially, it was seen as an extension of the street, a public space for the community to work, gather, and gossip. (5).

1.2. Aims and Objectives

This paper delves into the nature of transitional spaces, focusing on the specific role and quality of threshold spaces, particularly porches, within traditional dwelling settlements. It aims to understand how these spaces function as crucial connectors between the neighborhood, street, and dwelling units. By examining porches, the study seeks to uncover their character, social significance, and morphological features, highlighting how they serve as mediators between public and private realms. The threshold spaces are integral to the cultural fabric, reflecting the interaction between sacred and profane, and fostering community engagement through their multifunctional use.

Furthermore, this research investigates the historical and climatic influences that have shaped these threshold spaces. In India, the veranda, or porch, emerged as a response to the need for cooler outdoor areas, becoming a vital part of daily life where people conducted morning chores, socialized, and held community activities. The threshold space is not just a physical extension of the house but also a cultural symbol of hospitality and social interaction, decorated and revered during festivities. The porch, therefore, encapsulates the essence of vernacular architecture, embodying the community’s adaptation to environmental conditions, social customs, and evolving needs over time.

By analyzing these aspects, the study underscores the significance of threshold spaces in maintaining the cultural and functional integrity of traditional settlements, offering insights into how these spaces foster a sense of community and continuity amidst changing times.

2. Methodology

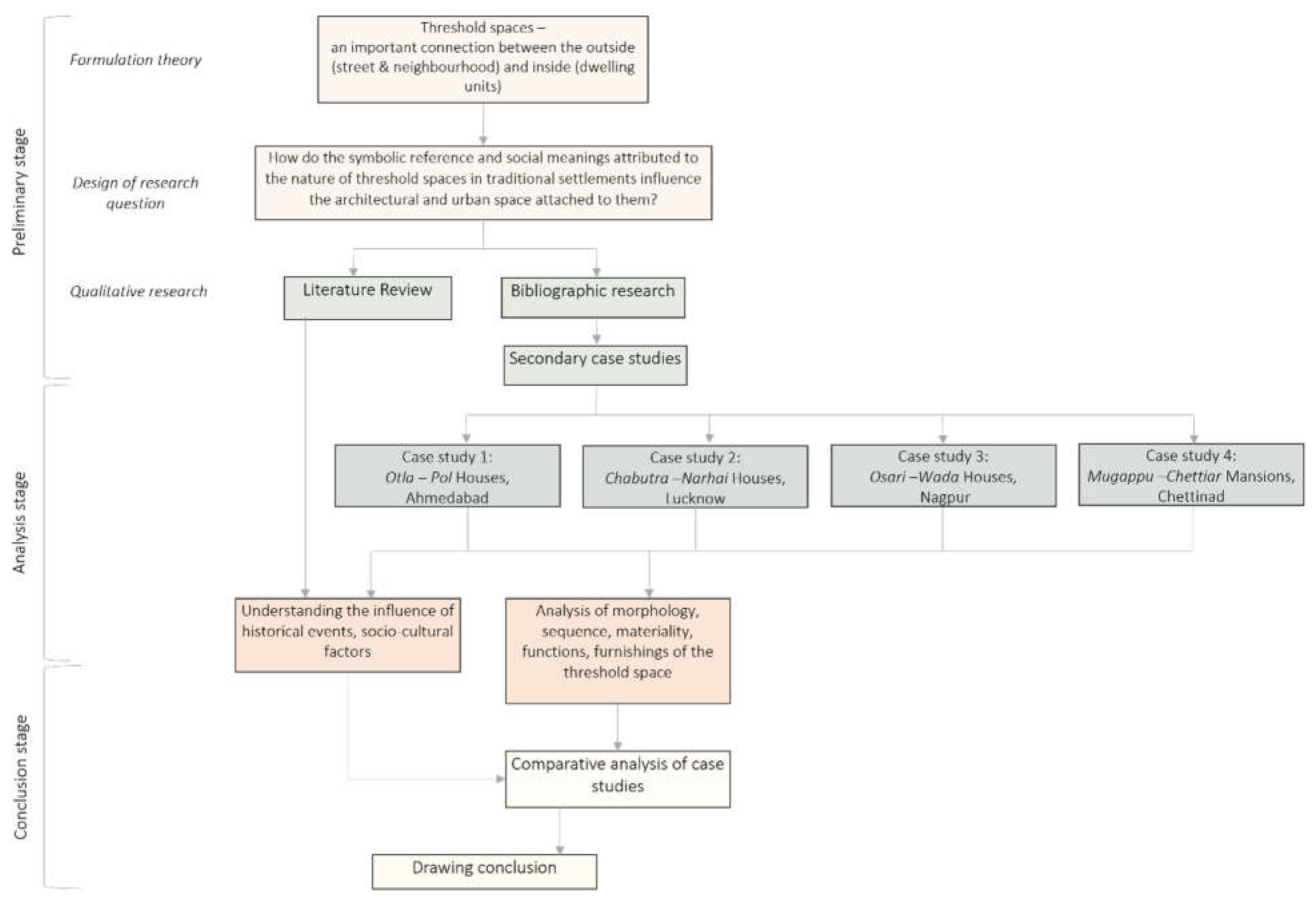

The methodology (figure 1) for studying the symbolic reference and social meanings attributed to threshold spaces in traditional settlements, and their influence on the architectural and urban spaces attached to them, is structured through a detailed flowchart. The research begins with an emphasis on threshold spaces, which serve as crucial connections between the outside (street and neighborhood) and inside (dwelling units). The central question guiding this study is: "How do the symbolic reference and social meanings attributed to the nature of threshold spaces in traditional settlements influence the architectural and urban space attached to them?"

To address this question, the methodology incorporates two primary activities: a literature review and bibliographic research. Additionally, secondary case studies are utilized to gather relevant data. Four specific case studies are selected to represent different regions and housing typologies: Otla – Pol Houses in Ahmedabad, Chabutra – Narhai Houses in Lucknow, Osari – Wada Houses in Nagpur, and Mugappu – Chettiar Mansions in Chettinad.

For each case study, the research focuses on understanding the influence of historical events and socio-cultural factors on the threshold spaces. This involves a detailed analysis of the morphology, sequence, materiality, functions, and furnishings of these spaces. The insights gained from the individual case studies are then compared to identify common patterns and unique differences.

The final step in the methodology involves drawing conclusions based on the comparative analysis of the case studies. This synthesis of findings aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of how the symbolic and social meanings of threshold spaces in traditional settlements influence their architectural and urban contexts. This approach allows for an in-depth examination of both the cultural significance and functional attributes of threshold spaces in vernacular architecture.

Figure 1.

Research Methodology Framework for the Study of Threshold Spaces in Vernacular Settlements of India.

Figure 1.

Research Methodology Framework for the Study of Threshold Spaces in Vernacular Settlements of India.

3. Literature Review

3.1. Traditional Cluster Dwellings

India is a complex country because of the diverse climatic conditions and topography and heterogeneity of its race, culture, religion, beliefs and ethnicity. Both these physical and socio-cultural aspects have a distinctive impact on the urban and rural fabric of cities and villages. The evolutionary pattern and time-tested qualities of the built environment of every town or city have a traditional core. The traditionality of the housing forms is determined by the peculiarities of the architecture in terms of the elements used, spatial characters, structural systems, construction technologies, use of locally available materials, climatic responsiveness and behavioral patterns; are the tangible representation of people’s goals and give a place ’identity.’ (6).

Architecture is said to be a true representation of society and is created at a certain moment for a specific location and population. These elements make up the built environment’s setting, conditions, and surroundings; in other words, they provide the built form with context. Since the beginning of civilization and the advent of safe havens, humanity has reacted to such situations by creating better living areas (6). Ancient civilizations like Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Japanese or Indus Valley are characterized by deep, long houses that are densely packed, with three edges shared with neighboring residences (7). The compactness of the settlement is attributed to the sense of security, economic considerations and the need for shading for climatic reasons (8).

These settlements, built in harmony with the community, reflect a shared way of life and value system, emphasizing affordability, sustainability, and adaptability. They result from the interaction between nature and culture, addressing both the tangible and intangible needs of ethnic groups. These cultural forms are products of continuous evolution, leading to advancements, improvisations, and modifications over time in response to changing needs. Consequently, the cultural forms exhibit aspects of both continuity and change, encompassing tangible and intangible elements. Interactions with other cultures have led to cultural amalgamations, facilitating the exchange of ideas, values, and cultural forms. The transmission of knowledge traditions from one generation to the next has ensured the continuity of these cultural practices (9).

The notion of identity, culture, and tradition tied to a settlement’s location is intrinsically linked to the concept of vernacular architecture. Glassie defines vernacular architecture as the local, traditional, or indigenous style of buildings and constructions that reflect the cultural, environmental, and historical contexts of a specific region or community (10). Built heritage is distinctive to various communities and contexts, showcasing how each community adapts to its climate, traditions, lifestyle, materials, and socio-economic conditions. This adaptation is expressed through the planning and organization of their open, semi-open, and enclosed spaces (11). This concept is vividly illustrated by traditional dwelling clusters, which embody the local, culturally specific architectural practices that respond to environmental contexts. These clusters, as practical examples of vernacular architecture, demonstrate how communities have historically adapted their living environments to align with their social structures, climatic conditions, and available materials. Vernacular architecture is also valued for its eco-sensitivity and community-oriented nature. Consequently, traditional dwelling clusters are not only reflections of vernacular architecture but also exemplify its environmentally conscious and culturally integrated approach in real-world settings (12).

3.2. Threshold Spaces

Transition is the foundation of architecture. Multiple spatial boundaries are traversed in day-to-day life. These spatial boundaries are crossed by thresholds to allow passage from one area to another. Spatial ambivalence is essential for the threshold phenomenon to exist. Thresholds define boundaries and organize transitions. They are read as part of the boundary and can be perceived as a barrier at the same time. The actual working rooms must be accessed through threshold gaps. They serve as the introduction to an impression of architectural space (2).

Till Boettger in his study of threshold spaces states:

“Threshold space can be described and defined from various perspectives. In the following text the term is seen from the point of view of the user, the space, and the architecture:

• A threshold space defines the opening of spatial delimiters during the act of crossing them.

• A threshold space is a transition that separates spaces from and connects them to one another.

• Threshold spaces are transitional spaces that provide a spatial preface to the functional spaces that follow” (2).

The progressive movement through spaces has been prioritized at both the housing cluster and dwelling unit levels. The journey from outside to semi-covered and finally enclosed places allows the human body to gradually acclimatize itself from a harsh climate outdoors to a comfortable one indoors (13). The space serves as an intermediary, a point of overlap between the interior and outside, and it serves to connect this relationship in the gradation of spaces from public to private (14).

“Transitions that mediate between public and private space are by far the most complex. They carry strong social and territorial implications. Whether space is public or private is always relative. It depends upon implicit cultural assumptions; how territorial control is physically asserted; and relationships between individuals, between spaces and/or between observer and observed.” (15)

The concept of the entrance space as a transitional zone is crucial in the cultural study of any traditional house form. In the Indian context, a threshold space, whether open or semi-enclosed, serves as a key component of the dwelling. This space should be understood in its multifaceted nature. Architecturally, it addresses the challenge of linking the house to the street. Socially, it is imbued with meanings that symbolize welcome, auspiciousness, and status (16). The semi-covered threshold spaces facing the street receive ample daylight, making them primary areas for sitting and socializing. These spaces, situated outside the house, naturally become public areas where neighborhood residents gather for various activities. The dense urban fabric and narrow streets foster a sense of security among the residents within the pol. This secure environment enables people to keep their main doors open from morning until night, allowing light to penetrate the interior of their homes (16).

Threshold architectural spaces have long held significant cultural value for the people of India. These in-between spaces, such as courtyards, stairways, and verandas, are integral to daily life. Entrances are especially revered by Indians across all social strata. Across the diverse landscapes of the country, transitional entry spaces are characterized by unique front verandas that seamlessly connect the street with the home. In India, the vernacular entrance threshold developed from the necessity for a cooler outdoor space. To escape the indoor heat, people spent much of their day in these areas. These in-between spaces accommodated activities ranging from early morning chores to evening lessons for community children. Urban liminal spaces are brought to life by the daily hustle and bustle. (5).

4. Study Areas

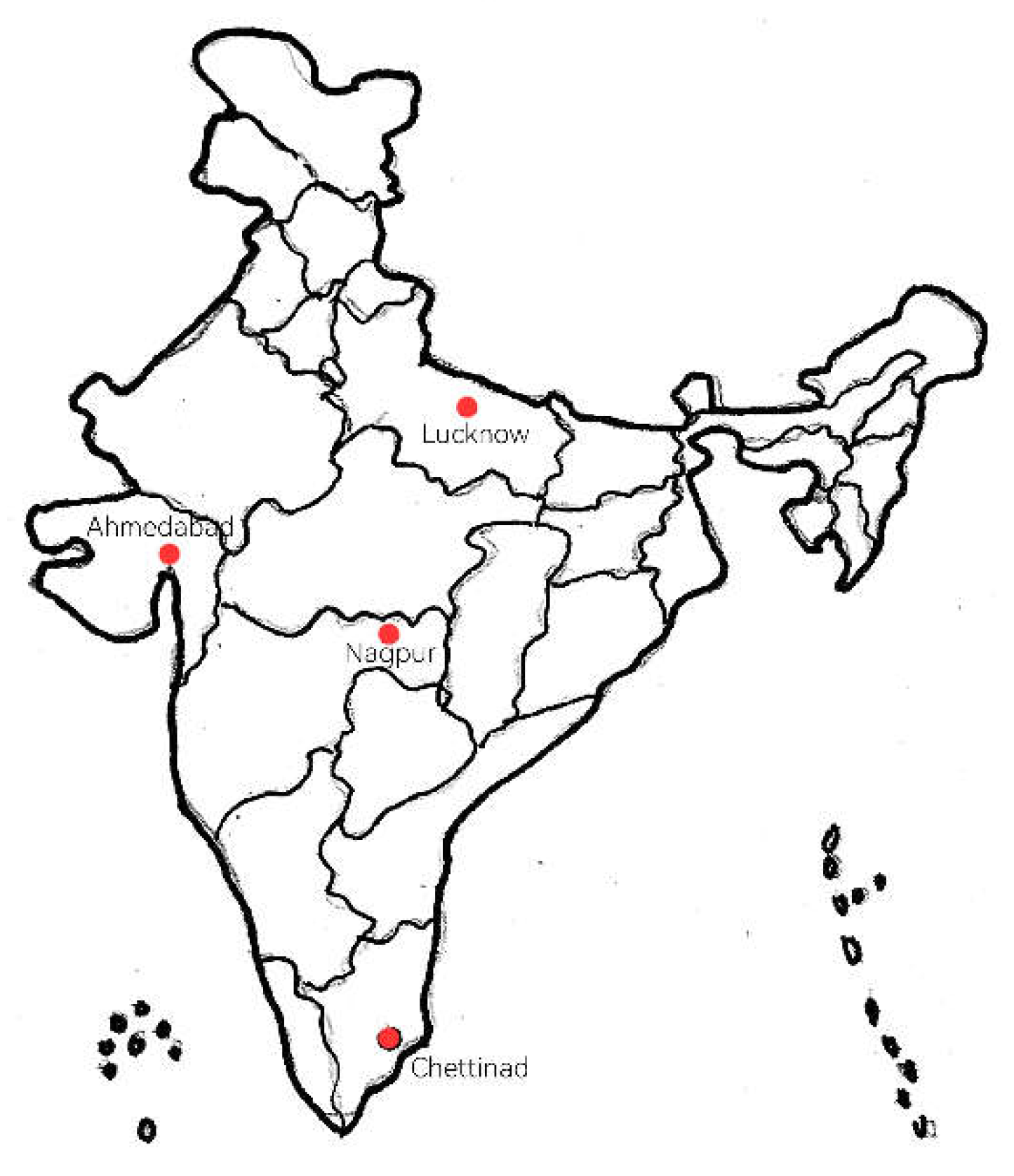

The threshold spaces within the residential buildings of cluster settlements exhibit overlapping concepts and complexities in their architectural and urban implementations. This research delves into the threshold spaces of four traditional dwelling clusters (

Figure 2) situated in urban contexts facing extreme climatic conditions. Specifically, the study examines the

Otlas of Pol houses in Ahmedabad, Gujarat; the

Chabutra of Narhai dwellings in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh; the

Mugappu of Chettiar palaces in Chettinad, Tamil Nadu; and the

Osari of Wadas in Nagpur, Maharashtra. These regions were chosen due to their diverse climatic challenges, ranging from the hot and arid conditions of Gujarat to the humid and tropical climates of Tamil Nadu and the seasonal extremes experienced in Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh.

4.1. Otla – Pol House, Ahmedabad

The Walled City of Ahmedabad was established in the 14

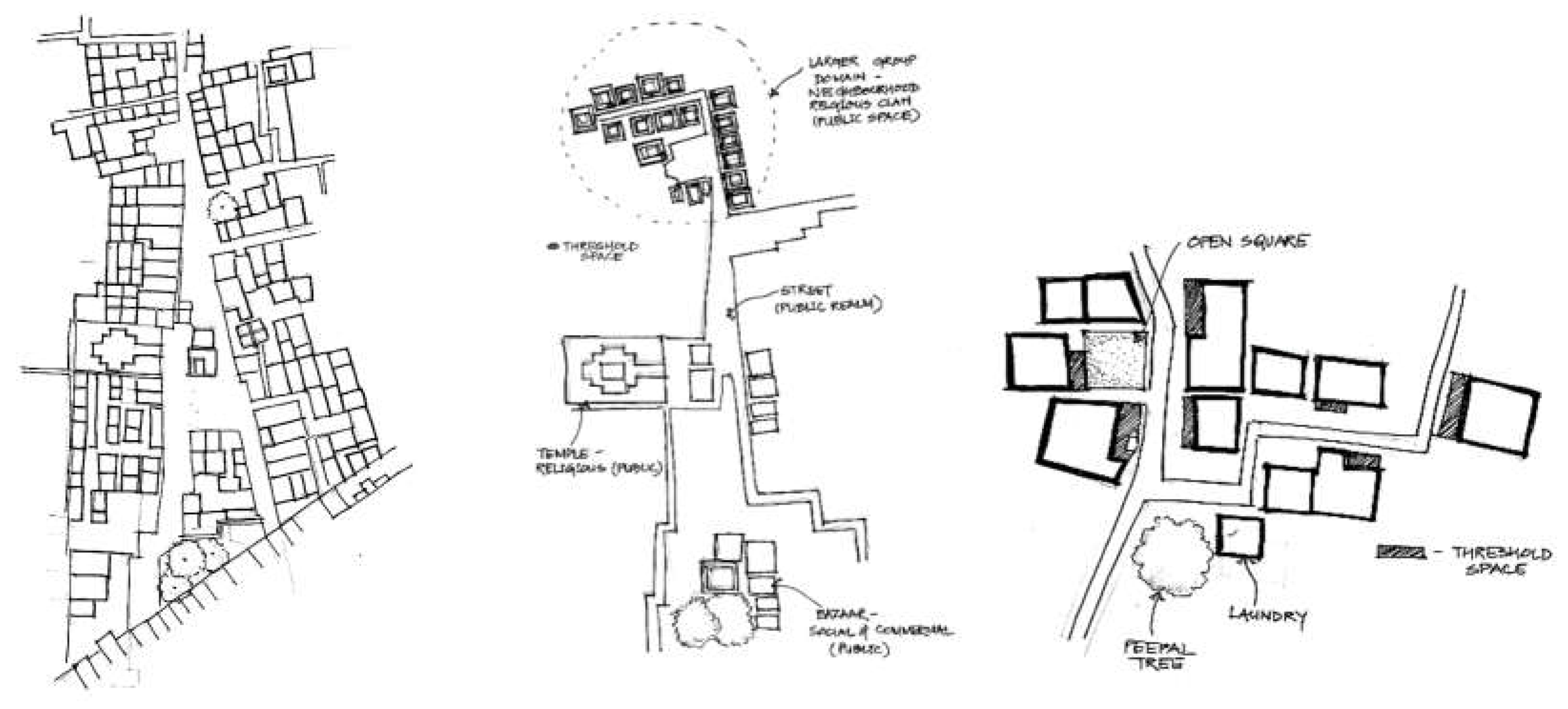

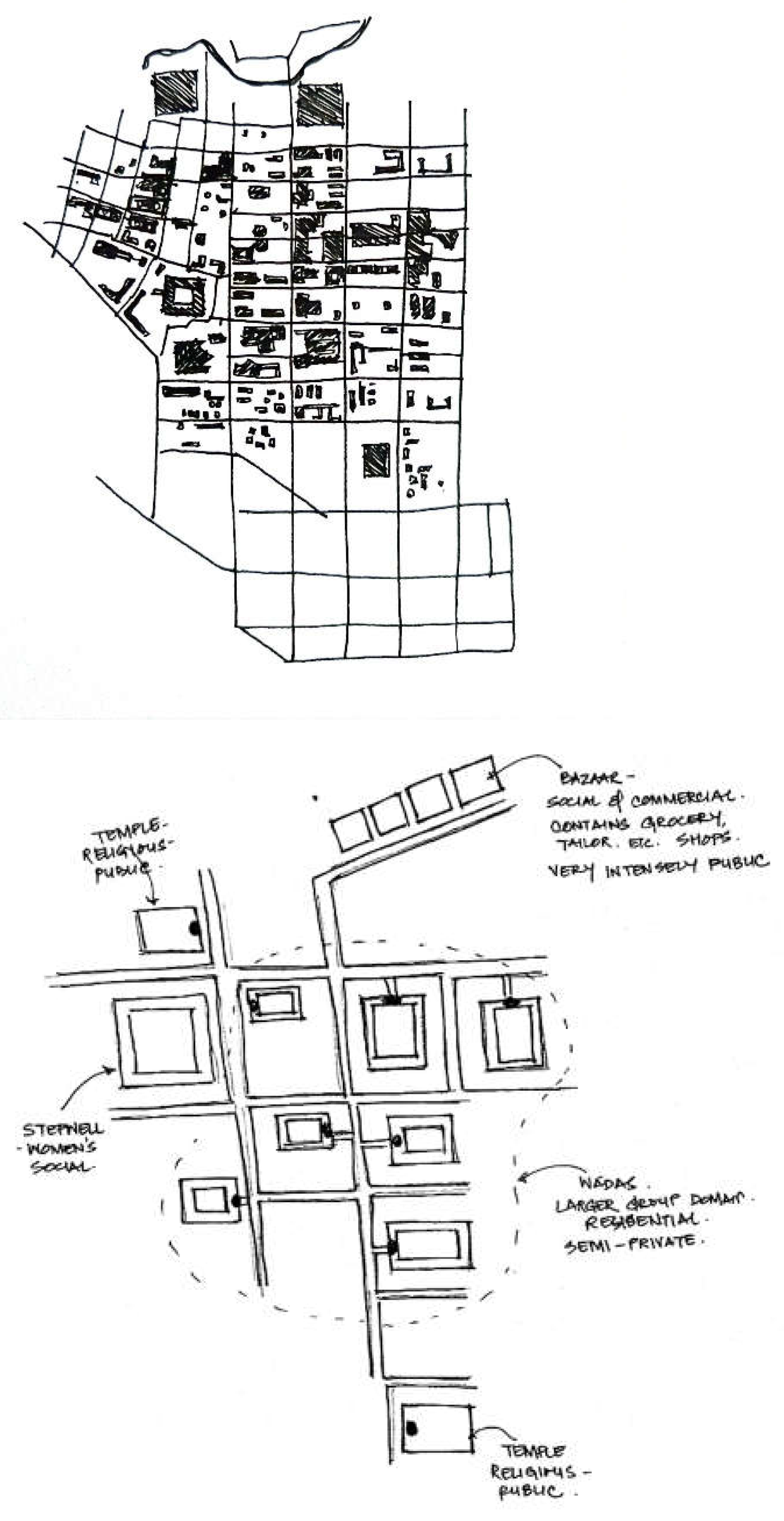

th Century A.D. and is the oldest part of Ahmedabad, situated on the banks of the river Sabarmati. Since medieval times, the town was densely built, in response to security concerns to protect people from the battles and also to tackle hot and dry climatic conditions (17). The layout of the town is organic with a hierarchal pattern of streets. The dense housing cluster of more than 300 traditional dwelling units was constructed within the boundaries of the wall (

Figure 3(i)). The major public spaces are comprised of bazaars, main roads and secondary streets (

Figure 2(ii)). Due to the harsh climatic conditions, small organic squares became open spaces (7).

The neighborhoods (

Pol) formed a cohesive unit and the grouping of the houses (

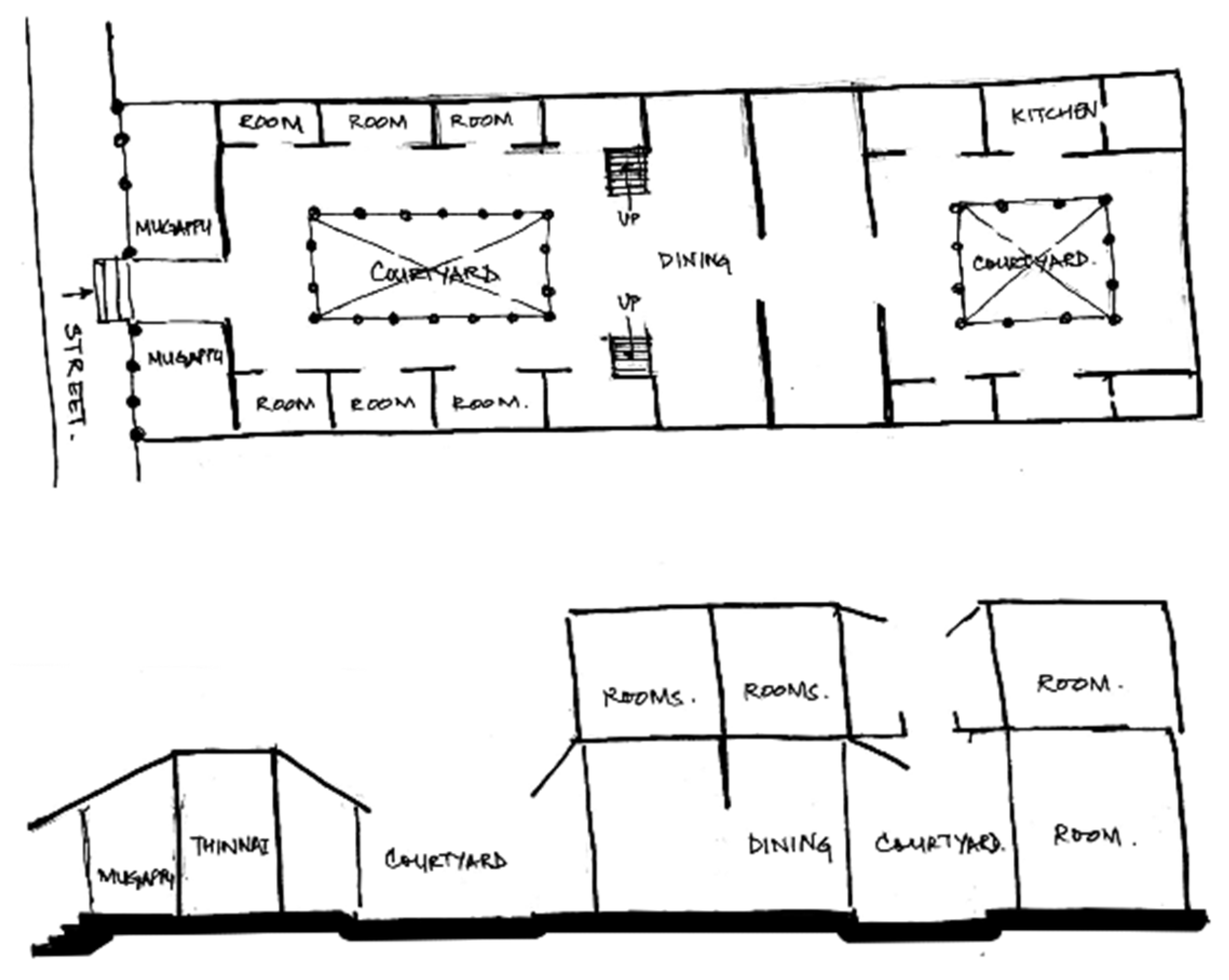

Pol houses) is homogeneous, forming a contiguous row of dwelling units (6). The typical

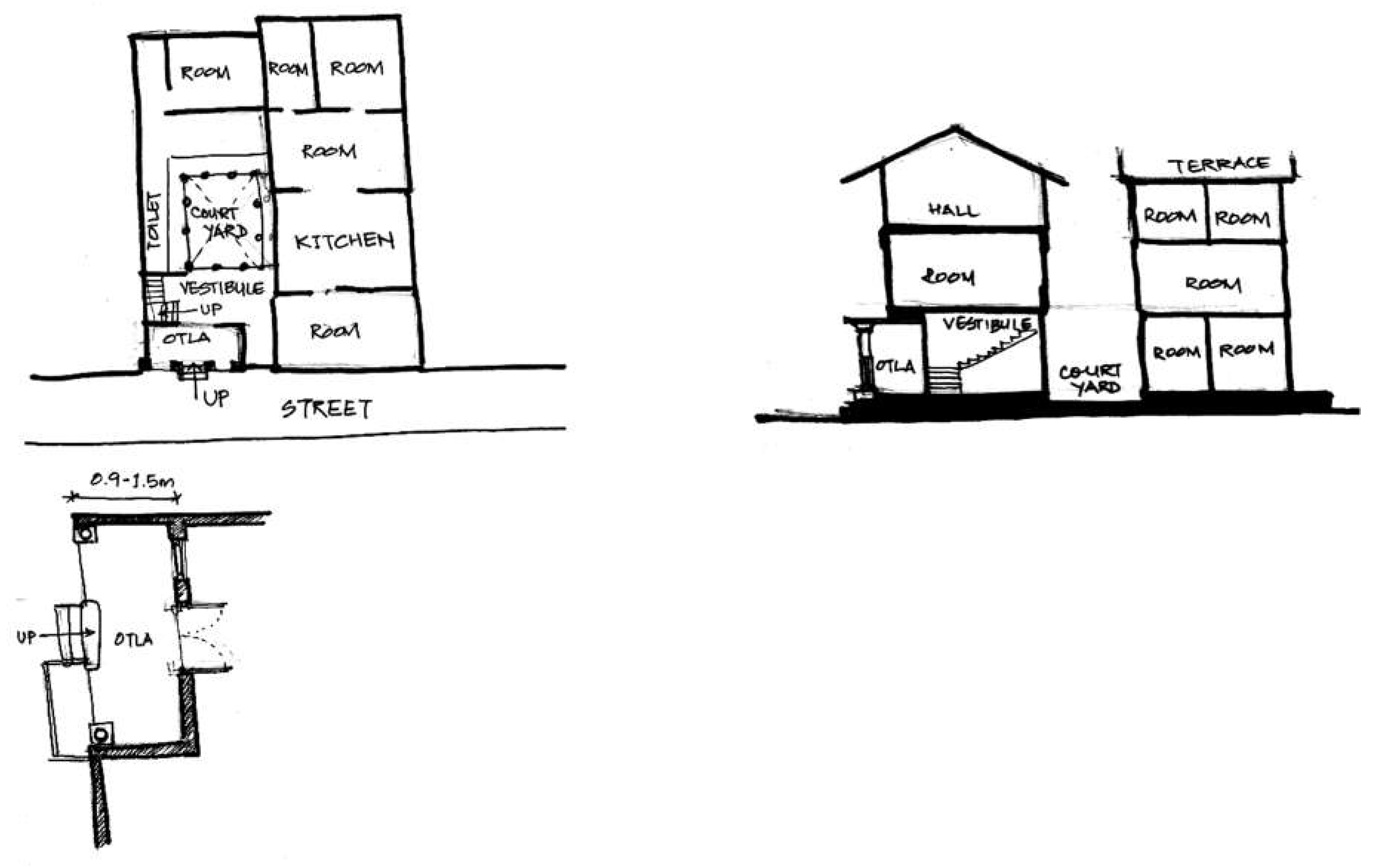

Pol dwellings are deep houses that commonly share a wall and have a narrow opening onto the streets (

Figure 3). In plan, they are organized into asymmetrically shaped plots and have varying internal levels (18).

The housing typology is generally organized according to the social group or community, having different yet related occupations. Individual residences have a significant gender disparity. Privacy was also maintained.

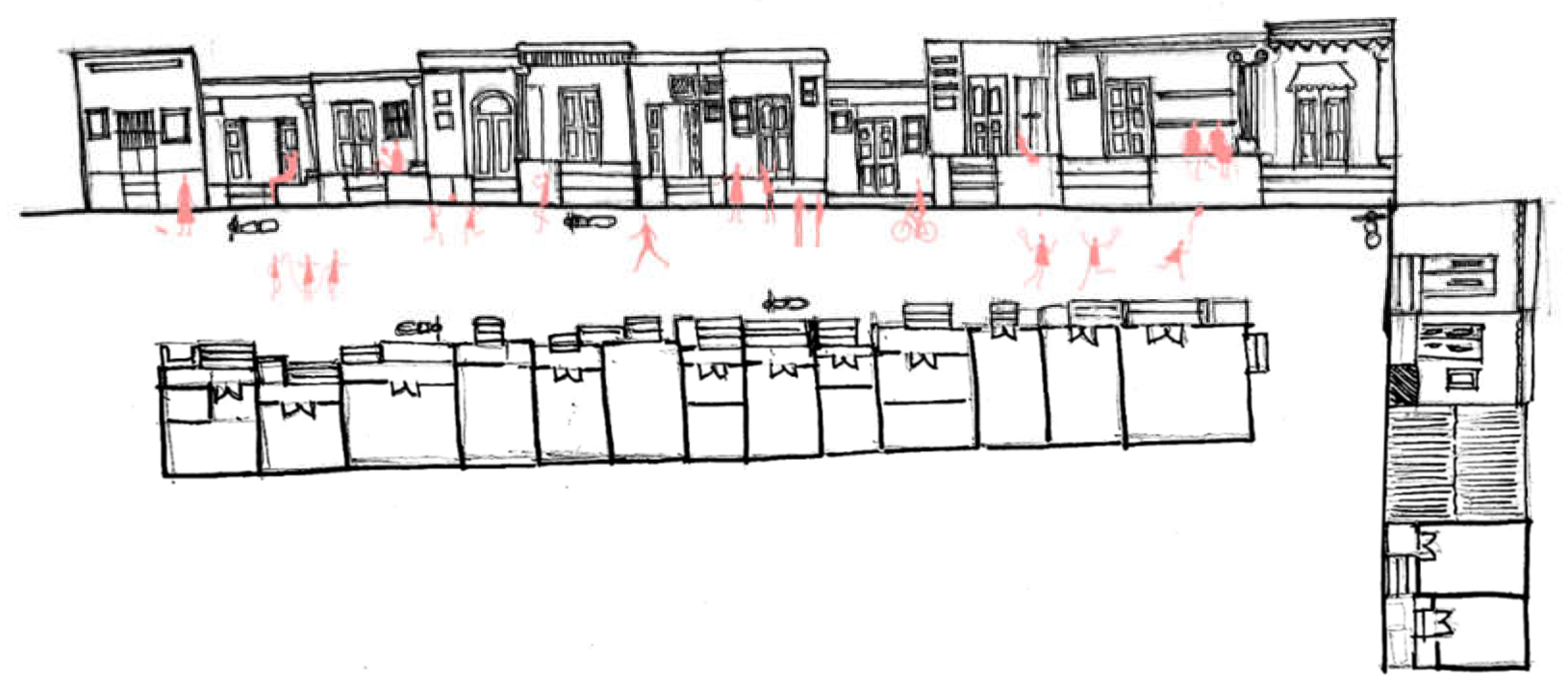

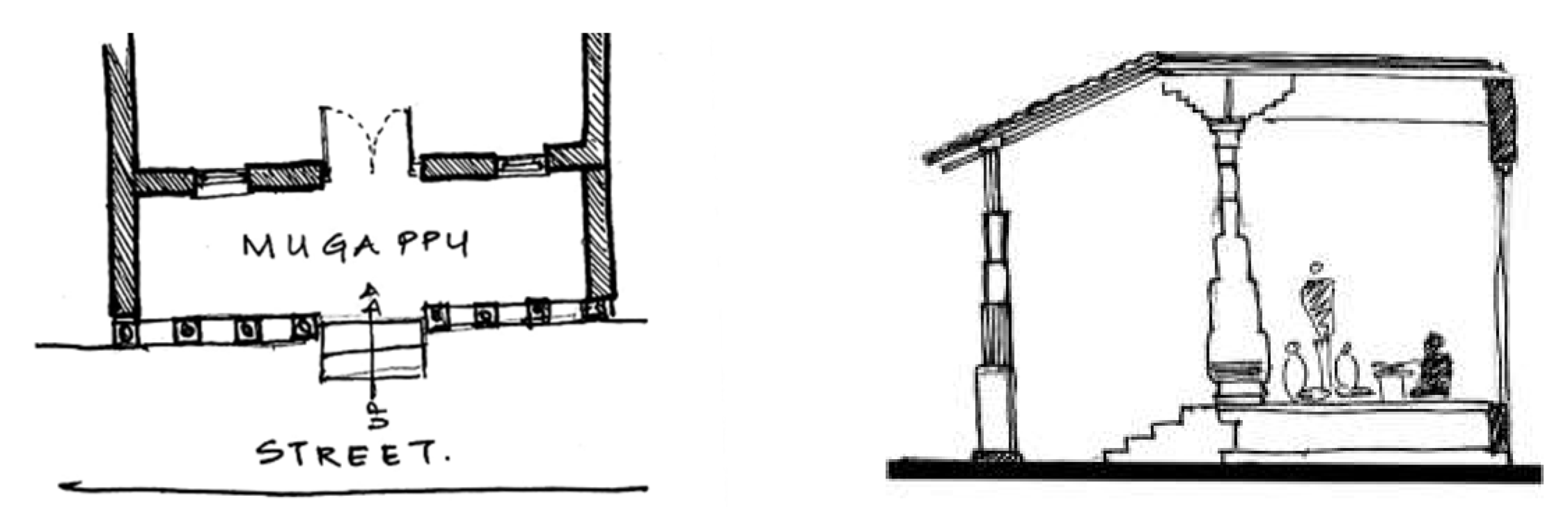

Otla which is the outermost part of the house draws a bridge between the public realm of the street and the privacy of the interior space (

Figure 5(i)).

Otla is usually a rectangular-shaped verandah that serves as the house’s entrance. The

otla opens into a

khadki, a semi-private place for interaction between men (7). The approach from the street to the threshold space is through the steps or ramps. It is usually 300-450 mm higher than the street level, consequently becoming more strongly established as a semi-public space of the house. The width and the depth of

otla vary from house to house (

Figure 5(iii)). The transition from the street to the

khadki is more extended and gradual if the

otla is deep. The walls are made of brick plastered on both sides. Flanking the steps are timber columns made of mango, neem or teak wood, heavily decorated with carved wooden elements (

Figure 6(ii)). The use of color, the pattern on tiles and doors and the decorations on the walls and floor of the

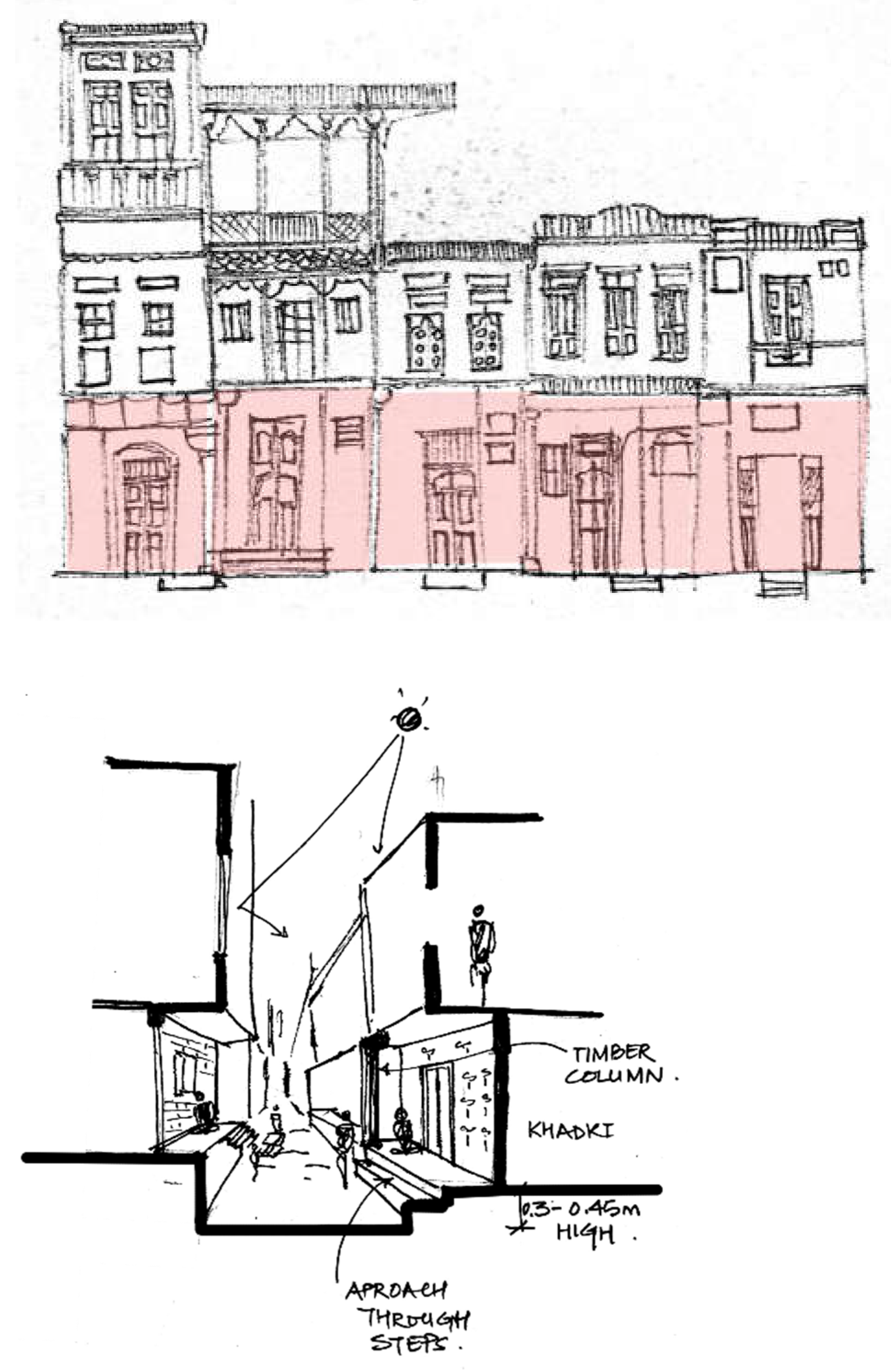

otla are unique to individual houses and strengthen their identity (19).

It is extensively used for social interaction, mitigating harsh climatic conditions, religious activities and symbolic decorations during festivals, thus making the neighborhood morphology and house form inseparable from each other (7). These activities spill over onto the streets, thus during festivities and celebrations streets become an extension of the house. In her study of Muslim Bohra dwellings, Madhavi Desai highlights a distinct use of the otla compared to its Hindu counterpart. Desai notes that, unlike the Hindu otla, which extends the physical space of the house into the street and serves as a site for various activities and interactions, the otla in Bohra dwellings is seldom used for such purposes. Instead, the relatively higher plinth of the Bohra otla signifies the resident’s social status and reinforces the strong notion of privacy essential within the Islamic community. Despite its limited use as an activity space, Desai underscores the otla’s role in conveying social meanings of welcome and emphasizes that it remains an aesthetic and symbolic part of the house, reflecting the social activities of Bohra families (20).

The otla serves as the primary reception area for pol houses, linking the street to the home. This semi-covered space, supported by columns at the edges and sometimes in the center, functions as a transitional zone between the exterior and interior. Social life in the pol revolves around the otlas, which are often highly ornamented with wooden carvings, contributing to the house’s front facade. Key structural elements include wooden columns, beams, brackets, lintels, and clerestory windows, all of which enhance the facade’s magnificence. Despite the narrow streets, otlas receive ample natural light while remaining shaded for various activities. Throughout the day, the otla hosts a range of activities: morning routines might include reading the newspaper, having tea, children studying and playing, and women braiding hair; midday activities might involve chopping vegetables and weaving; and evenings see residents socializing, having tea, and children playing. The otla, as the most public part of the house, allows neighbors to gather and engage in communal activities, such as women working together during festivals like Diwali. This communal use of the otla fosters a sense of mutual dependency and transforms the neighborhood into a cohesive, family-like community (16).

4.2. Chabutra – Narhai House, Lucknow

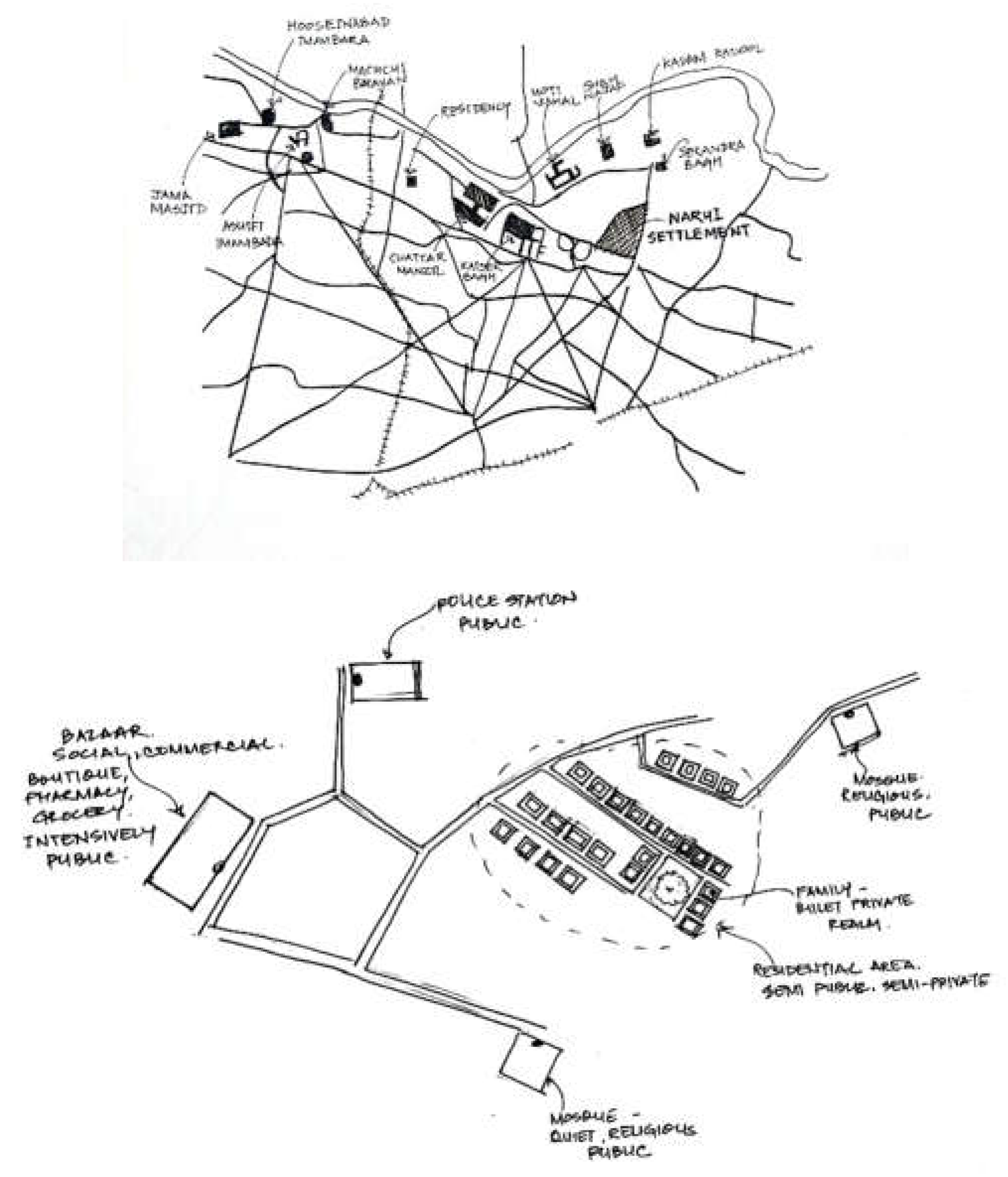

On the banks of the Gomti River, in the northern Indian plains, lies the city of Lucknow. It has been subjected to a variety of rulers, including Hindus, Mughals, and Nawabs, as well as British and post-independence developments, all of which have left an indelible stamp on the city’s culture and architecture in particular (21). The earliest vernacular settlements developed in the Southeastern part of the river Gomti. These settlements are characterized by pre-colonial structures and high-density fabric (22). Narhai settlement was a similar scenario, located relatively close to the major Hazratganj region (

Figure 7(i)), where a huge group of Hindu and Muslim families incrementally built their residences. The urban fabric of settlement can be characterized by crowded lanes, crossings, temples, mosques, shrines, bazaars, open public squares and a community park (

Figure 7(ii)).

The layout of the neighborhood is composed of row housing units arranged wall-to-wall placed along the street with a sizeable public green park located in the middle of the neighborhood. The dwelling units are geometrical in form and have courtyards to respond to the composite climate facing extreme conditions, harsh winters and hot summers and also addressed the need for social interactions. The residences are mostly facing East or West, with perpendicular streets running North to South. The corner houses face the park and have access from three sides, while the comparably smaller units have been located abutting the streets (

Figure 8), indicating an economical hierarchical grouping with the existing social order (21). The width of the streets abutting the dwelling units ranges from 3m – 5m. These streets act as linkages between the houses and serve as interaction spaces and various activities (22). The height of the buildings is greater than the width of the street, thus providing shade from the sun, making the streets an ideal place for engaging in social activities and shaded walkways for pedestrians.

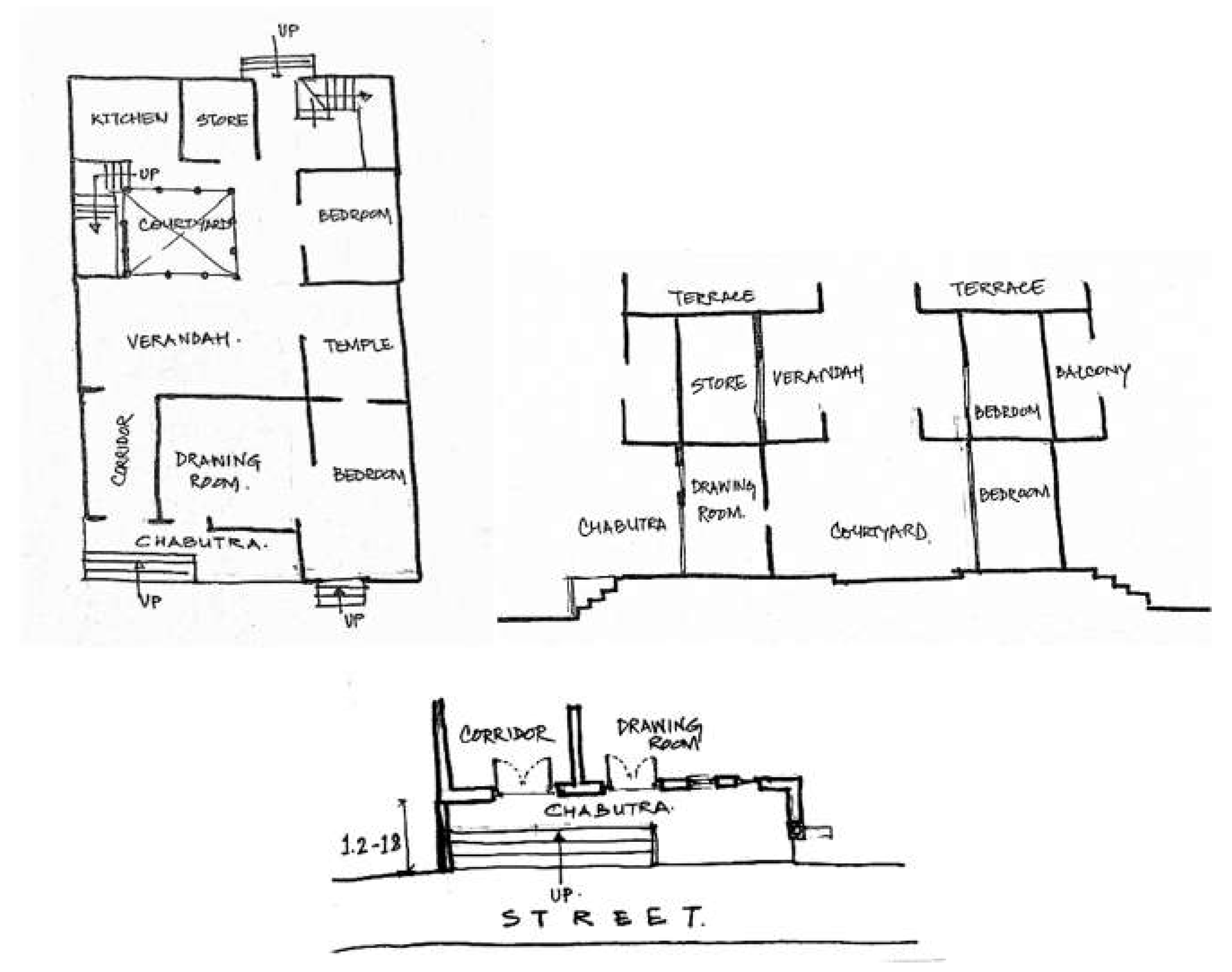

The pattern of incremental growth in the construction of individual dwelling units over the years of habitation has been noticed. The construction of two front rooms with

chabutras facing the street and a verandah extending to the back courtyard on the Ground Floor made up the first phase. The second stage involved the construction of additional rooms, including the staircase, on the ground floor (

Figure 9(i)). As the family grew, the first storey was built in a similar design to the ground floor (

Figure 9(ii)), preserving the verandah and courtyards while adding a balcony over the

chabutra facing the street (21).

The

chabutra, or the plinth platform, serves as an important transitional element from the street to the house, having both practical and social functions. Its average height from the street is 900 mm, but its average width is 1200 mm (

Figure 9(iii)), with a height to width ratio of 1:3. This raise in the height from the streetscape establishes a clear relationship between the

chabutra and the exterior side. The length varies, but the side facing the street is generally continuous. The construction is of bricks joined by lime-

surkhi plaster. The external finish is with lime stucco plaster painted in a bluish lime matt texture. It is mainly populated in the winter mornings and summer evenings when locals spend their free time watching street activities and conversing with neighbors and guests (

Figure 10(ii)). The façade is a coherent whole of

jharokhas, balconies, pilasters and windows with stucco embellishments, while the roof is flat with projecting terraces and balconies (

Figure 10(i)). The homemakers purchase vegetables or other necessities from hawkers while standing or sitting on chabutras and watching children play nearby while the elderly rock in their rocking chairs. Here is where most of the neighborly encounters take place (21).

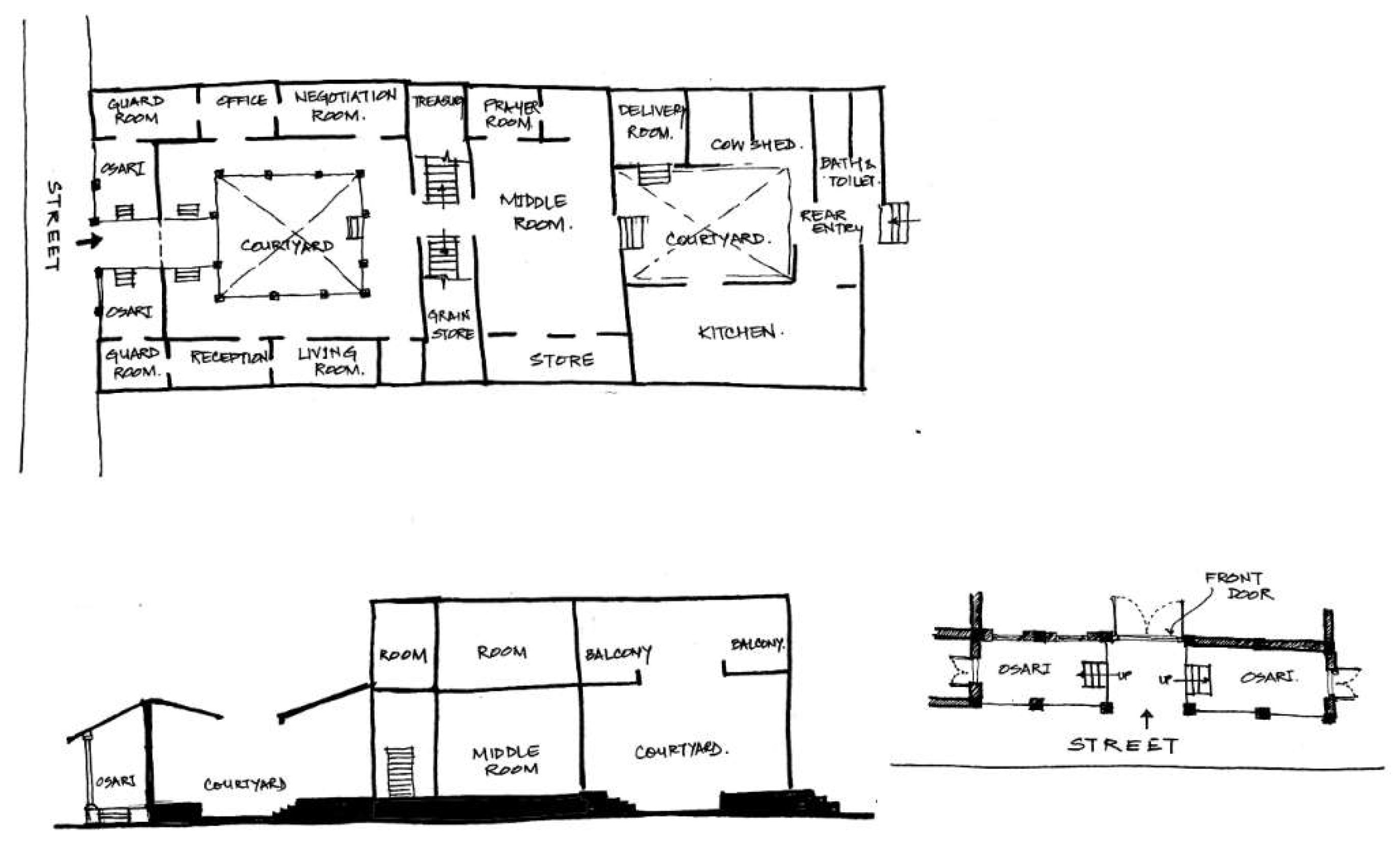

4.3. Osari – Wada Houses, Nagpur

Nagpur is the third-largest city in the state of Maharashtra and has a history dating back more than 300 years. Since its inception has undergone a constant transformation (23). Situated along the banks of river Nag, is located at almost the geographical center of the country. In the 17th century, under the renowned ruler Shivaji’s leadership, the Marathas scarcely had any resources or time to devote to pursuits other than battling for freedom from the British raj. Under the Peshwa rule from the early 18th century to the middle 19th century, the region achieved economic and political stability. This period witnessed socio-cultural progress (7). Nagpur was urbanized in the early half of the 18th century around the Gond Raja fort. The Wadas (traditional Nagpur dwellings) were developed by utilizing the wealth acquired by the Peshwas.

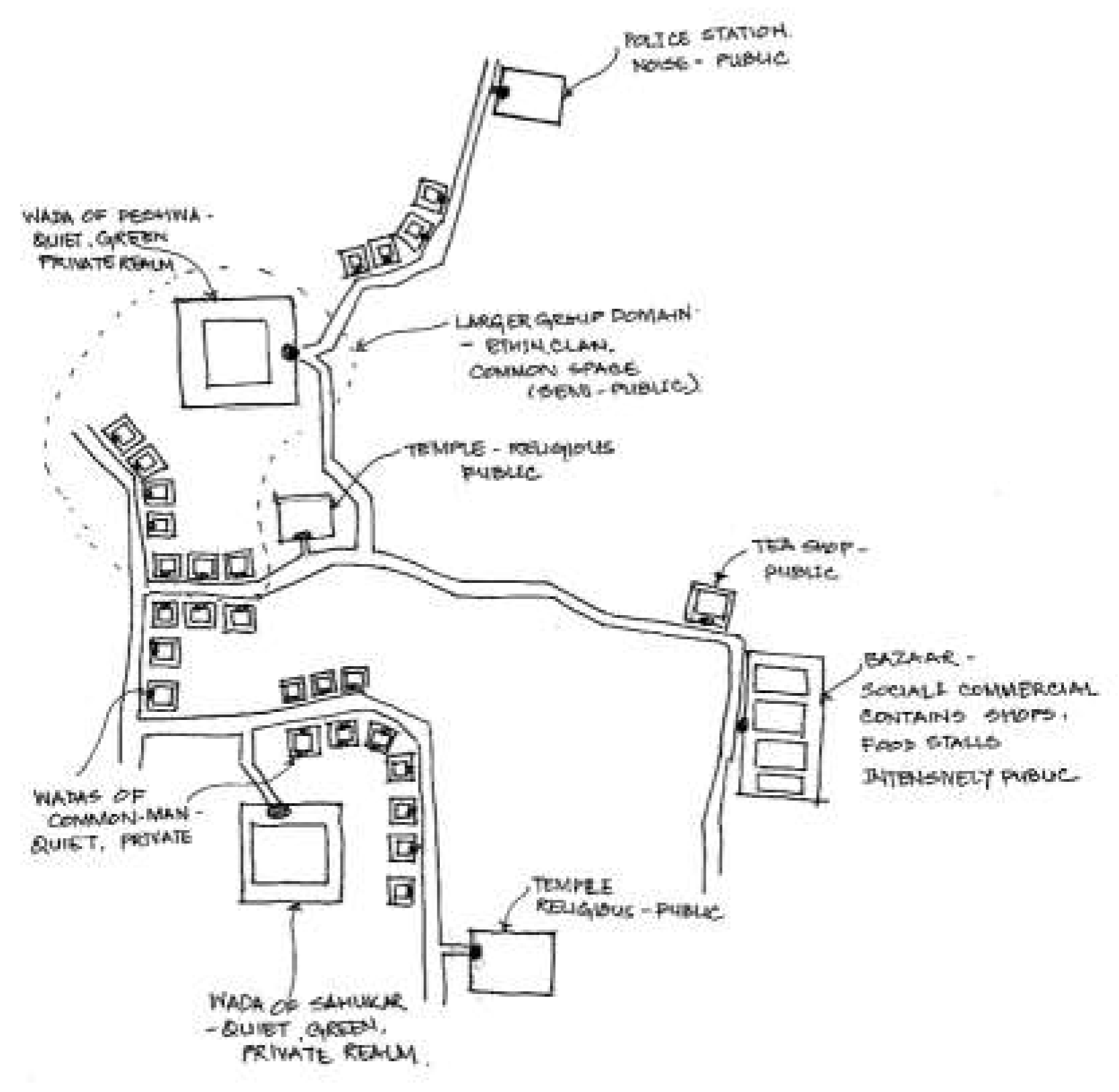

Nagpur’s walled traditional center (Mahal) has historically comprised clusters of neighborhoods (

Figure 11) with similar castes and occupations (23). Marathi society is close-knit and conservative in nature (7) thus fostering connectedness in the housing community. The residential units are closely packed with the adjoining

Wadas. This proved to be an economic and efficient way of utilizing the land for housing while at the same time ensuring the security of the locality. The neighborhood has a dense fabric and an organic intrinsic growth pattern. It has narrow lanes and streets which were not intended for motorized transportation. They serve as open areas for a range of political, social, commercial, recreational, religious and festive activities (24). The temples and shrines are spread throughout the settlement with markets running along the street (

Figure 12).

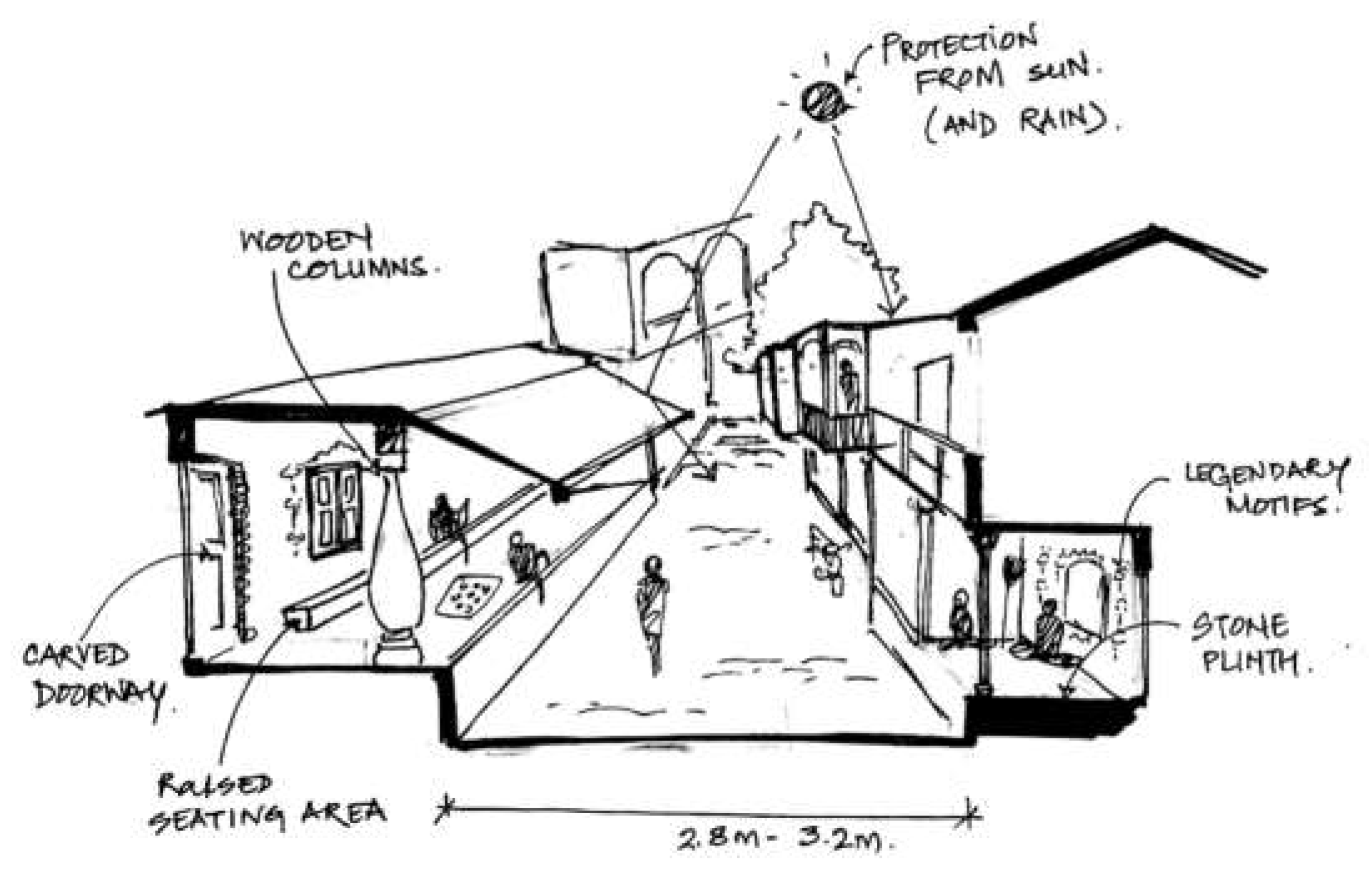

Architecturally speaking, the Maharashtrian house has been austere in design, robust in its fundamental architectural components, such as the unique configurations of courtyards, and modest in scale and size (25). The wadas are enormous. The units built by the Peshwas, bankers and treasurer (sahukars) were spacious manors and seven-storey high. The wadas of the common man also had the same architectural style built between two-four storeys. The home typology supports privacy by having an introverted spatial congregation for security and defense. Planning is grid-based and usually concentrated around the concept of the courtyard. The colonnaded verandah has been built around it, each with a different room behind it. The pooja room, kitchen, outside veranda platform (osari), and bedrooms with adjoining bathrooms make up the ground level (26).

The entrance to the house from the street is through the two semi-open raised platforms on each side of the door. It denotes the change from a public to a private space. It links open and enclosed spaces as well as internal and outdoor spaces (

Figure 14(i)). This spatial component, which brings together two opposing realities, has been linked to metaphysical concepts. Locals referred to it as "

osari”. This transitional place allows residents and onlookers to halt for conversation and assists Wada residents in socializing with the community, thus serving as an interactive space (

Figure 13). Wada threshold platforms are slightly elevated, acting as a means of transition between built form and land. The platforms are split into two parts by the main door, approached by a couple of steps (

Figure 14(iii)). A semi-enclosed space that offers protection from the rain and sun. The platform also becomes a drying area for the grains.

This space had a simple rectangular geometric form that gave rise to an architecture that was both basic in form and rich in available space (

Figure 15). Due to the quality of light the space received, the visual layers of spaces it generated, and the variety of uses

osari was put to, the space was rich (25). The craftsmen from different parts of the country adorned the entrance doorway with carvings. The plinth is made of stone. The wooden columns are usually square and have ornamented brackets that support the balcony on the first floor (26). The walls had a composite structure and were made of thick mud, stone or brick. In some cases, legendary motifs were painted on the walls, and the ceiling featured ornate woodwork (25).

4.4. Mugappu – Chettiar Mansions, Chettinad

Chettiars are a trading community that founded Chettinad settlements which comprise 75 villages. It is located hot and arid south-eastern part of Tamil Nadu and sprawls over 1554 km of barren hinterlands (7). Due to the lack of cultivable land, members of the community began to migrate to other regions of India and abroad to conduct trade and seek possibilities to develop the business. The affluent merchants obtained the pricey and exquisite materials from these excursions, which later became a crucial component of the distinctive Chettinad architectural homes (27).

Kanadukatham is a settlement near Karaikudi, the main town of Chettinad. This township typically follows the grid-iron pattern (

Figure 16(i)). Streets run north-south, with utility streets and main streets running parallel to one other. Long and narrow residences with multiple inner courtyards run the length of the site from the front street to the back (28). The depth of the plots on the palatial houses that span between the streets is around 7.5–10.0 m. A small distance of one meter separates the dwelling units in the north-south direction. The grid is designed in such a way that traders and their employees are given priority when distributing plots (

Figure 16(ii)). The integration of technologies such as drainage and rainwater harvesting is an important part of the town’s infrastructure (7). The temple is very important to the

Chettiars at all stages of their lives. The settlement grew in a way that made the temples and other religious sites its focal point (27).

Chettinad’s dwellings are oriented east-west because the house was considered a cosmos within a cosmos and all daily rituals were focused on the sun’s journey across the sky. This direction also allowed the wind to circulate freely within the house. The dwellings were organized longitudinally (

Figure 17(i)) based on the usage of space and the gender of the occupants (27). Typically, they are divided into zones that go from the most public to the most private sections (28). The interior portions were occupied by the women and servants whereas the exterior parts of the house were used by men. The outermost semi-open verandah space is called

Mugappu (

Figure 18 (i)).

Business meetings and money lending practices are carried out by the men of the family in

Mugappu. It also acts as a space to socialize (

Figure 18 (ii)). The

Mugappu area is entirely adorned with the most expensive materials. The ornate door links the

Mugappu area on the outside with

Valavu, a semi-open area used by the joint family. The threshold separates the public and private areas of the house. Columns are made of highly polished Burmese teak wood, satinwood, and polished granite. The walls are cladded with Japanese and Venetian tiles. The ceiling is covered with tiles, frescos, paintings and murals. The door, frame, frieze and cornice are highly carved and detailed with stained glass elements (27). European-style cast-iron benches are the furnishings placed to allow comfortable seating.

5. Results

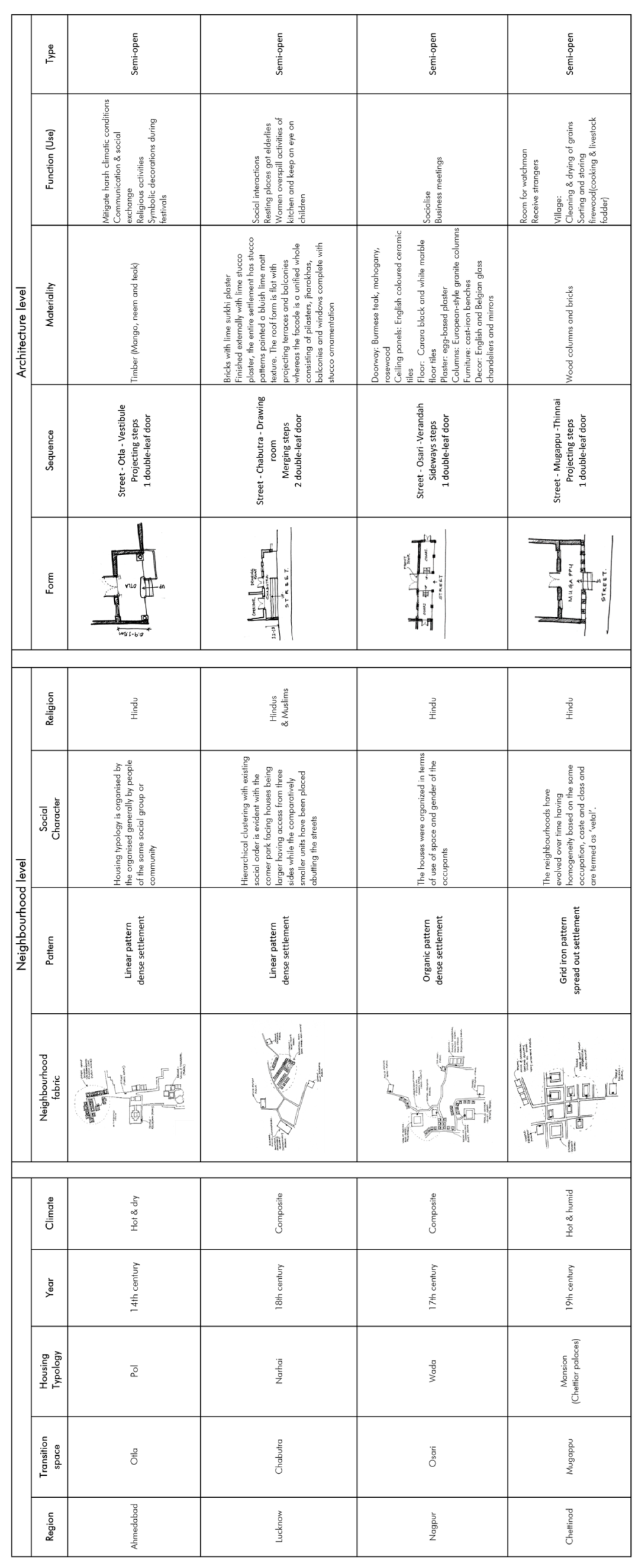

The provided table (

Table 1) provides a detailed comparison of threshold spaces in each case study and aims to understand the influence of historical events and socio-cultural factors on the threshold spaces, analyzing aspects such as morphology, sequence, materiality, functions, and furnishings.

For instance, the Otla in Pol Houses of Ahmedabad, dating back to the 14th century, reflects a dense, linear pattern organized by social groups, primarily Hindus, with timber materials mitigating harsh climatic conditions and serving social and religious functions. Comparatively, the Chabutra in Narhai Houses of Lucknow, from the 18th century, features a hierarchical clustering within a composite climate, accommodating both Hindus and Muslims with brick and lime materials supporting social interactions and resting places for the elderly. The Osari in Wada Houses of Nagpur, dating to the 17th century, showcases an organic pattern with rich materiality like Burmese teak and English ceramic tiles, facilitating social and business meetings. Lastly, the Mugappu in Chettiar Mansions of Chettinad, from the 19th century, within a grid-iron pattern, reflects homogeneity based on occupation and caste, using wood columns and bricks for multifunctional purposes like receiving strangers and sorting firewood. From this comparison, several results can be drawn:

1. Climatic adaption: Each threshold space is adapted to its specific climatic conditions. For example, the Otla in Ahmedabad’s Pol Houses mitigates harsh, hot, and dry conditions with materials like timber, while the Mugappu in Chettinad addresses hot and humid conditions with wood columns and bricks.

2. Social and Cultural Integration: The threshold spaces reflect the social and cultural practices of their respective communities. The Otla in Ahmedabad and the Chabutra in Lucknow show a strong integration of Hindu and Muslim social structures, respectively. Similarly, the Osari in Nagpur and the Mugappu in Chettinad indicate Hindu influences in their spatial organization and usage.

3. Neighborhood Fabric and Organization: The organization of houses within these clusters varies, reflecting the socio-cultural dynamics of each region. Ahmedabad and Lucknow show linear, dense patterns with hierarchical clustering, while Nagpur presents an organic pattern, and Chettinad follows a gridiron pattern with evolved homogeneity based on occupation and caste.

4. Materiality and Construction Techniques: The materials used for threshold spaces differ significantly, indicating local availability and historical preferences. Ahmedabad’s Otla uses timber (mango, neem, and teak), Lucknow’s Chabutri uses bricks with lime plaster, Nagpur’s Osari features a mix of Burmese teak and English tiles, and Chettinad’s Mugappu employs wood columns and bricks.

5. Functional Diversity: The threshold spaces serve various functions beyond mere entry points. In Ahmedabad, the Otla is used for social exchanges and religious activities. In Lucknow, the Chabutra serves as a social interaction space and resting place. Nagpur’s

Osari facilitates socializing and business meetings, while Chettinad’s Mugappu serves multifunctional purposes, including receiving strangers and sorting firewood.

6. Architectural Features and Sequences: The sequence of spaces from the street to the dwelling units varies across regions. For instance, Ahmedabad features a sequence from the street to Otla to the vestibule, while Lucknow has a sequence from the street to Chabutra to the drawing room. These sequences reflect the cultural and functional priorities of each region. Residents extravagantly decorated their verandas to express their cultural beliefs.

In summary, the table highlights how traditional dwelling clusters embody vernacular architectural principles through their adaptation to climate, integration of social and cultural practices, use of local materials, and multifunctional roles. These insights underscore the significance of threshold spaces in maintaining the cultural and functional integrity of traditional settlements.

6. Conclusions and Further Research

In this study, the nature of threshold spaces were explored in traditional dwelling settlements, focusing on their architectural, social, and cultural significance. The findings draw upon the works of scholars such as Boettgar (2014) and Gattupalli (2022), who emphasize the multifaceted nature of threshold spaces from the perspectives of the user, space, and architecture.. By comparing the Otlas of Pol houses in Ahmedabad, the Chabutra of Narhai dwellings in Lucknow, the Mugappu of Chettiar palaces in Chettinad, and the Osari of Wadas in Nagpur, diverse ways are highlighted in which these spaces respond to their respective climates and cultural settings. Pandya (2017) examined the densely packed, traditional vernacular houses and has highlighted the significance of threshold spaces in social interaction, the role of public spaces like bazaars and streets.

The research indicates that threshold spaces serve as vital connectors between the public and private realms, embodying social meanings and fostering community engagement. These spaces reflect a blend of continuity and change, evolving to meet the needs of their communities while retaining their cultural essence. This is consistent with international research on vernacular architecture, which underscores the importance of context-responsive design.

The implications of these findings extend beyond the specific cases studied. Threshold spaces, with their multifunctional roles and cultural significance, offer valuable lessons for contemporary architecture and urban planning. They demonstrate how design can harmonize with environmental and social imperatives, suggesting that similar approaches could be beneficial in other regions and contexts. However, while the findings provide important insights, it is essential to avoid overgeneralizing, as the unique cultural and climatic conditions of each region play a crucial role in shaping these spaces.

The strengths of this work lie in the detailed comparative analysis and the documentation of diverse threshold spaces. However, the study has its limitations, primarily due to its reliance on secondary sources and the qualitative nature of the findings. Future research could benefit from primary data collection and a broader range of case studies to enhance the generalizability of the results. Additionally, exploring the impact of modern interventions on these traditional spaces could provide further insights into their adaptability and resilience.

The work has several implications for architecture, planning, and policy. It highlights the need to preserve and integrate traditional design elements that promote social interaction and environmental sustainability. Policymakers and urban planners should consider these principles when designing new developments or upgrading existing ones, ensuring that they support community cohesion and respond effectively to local climatic conditions.

This research can be particularly useful to architects, urban planners, policymakers, and scholars interested in sustainable design, cultural heritage preservation, and community-focused urban development. By understanding the value and functionality of threshold spaces, professionals in these fields can develop more resilient and socially cohesive built environments that respect and integrate local traditions and climatic conditions.

In summary, the paper emphasizes the significance of threshold spaces in traditional dwelling settlements, showcasing their role in maintaining cultural continuity and fostering community interaction. These spaces not only bridge the public and private realms but also reflect the ingenuity of vernacular architecture in responding to environmental and social challenges. Future research should continue to explore these themes, building on these findings to further understand the potential of traditional design principles in contemporary practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.N.T., H.B.U. and M.S.L.; methodology, J.N.T., H.B.U. and M.S.L.; software, H.B.U.; validation, J.N.T., M.S.L. and O.O.; formal analysis, H.B.U.; investigation, H.B.U.; resources, H.B.U.; data curation, H.B.U.; writing—original draft preparation, H.B.U.; writing—review and editing, J.N.T., M.S.L. and O.O.; visualization, H.B.U.; supervision, J.N.T.; project administration, J.N.T.; funding acquisition, J.N.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by European Union’s Horizon Europe programme (Grant Agreement Number 101138449—MI-TRAP- MItigating TRansport-related Air Pollution in Europe).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available by authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- Mhatre, Sanket. Thresholds: A Vital Link between the Worlds. [book auth.] Marcello Balzani, Minakshi Jain and Luca Rossato. Between History and Memory, the Blue Jodhpur. Santarcangelo di Romagna : Maggioli Publisher, 2019, pp. 133-143.

- Boettger, Till. Threshold Spaces: Transitions in Architecture : Analysis and Design Tools. s.l. : Birkhäuser Basel, 2014.

- In-Between Space, Dialectic of Inside and Outside in Architecture. Shahlaei, Alireza and Mohajeri, Marzieh. 3, 2015, International Journal of Architecture and Urban Development, Vol. Vol. 5, pp. 73-80.

- Transition Spaces in an Indian Context. Sadanand, Anjali and Nagarajan, R.V. 3, 2020, Athens Journal of Architecture, Vol. Vol. 6, pp. 193-224.

- Gattupalli, Ankitha. The Veranda: A Disappearing Threshold Space in India. arch daily. [Online] July 15, 2022. https://www.archdaily.com/985402/the-veranda-a-disappearing-threshold-space-in-india.

- A shape grammar approach to contextual design: A case study of the Pol houses of Ahmedabad, India. Lambe, Neeta Rajesh and Dongre, Alpana R. 2019, Urban Analytics and City Science, Vol. 46(5), pp. 845-861. [CrossRef]

- Pandya, Yatin. Courtyard Houses of India. s.l. : Mapin Publishing Pvt. Limited, 2017.

- Rapoport, Amos. House Form and Culture. Milwaukee : Prentice Hall, 1969.

- Conserving continuously evolving cultural landscape case: Vernacular settlement of village Nirmand, Himachal Pradesh, India. Bhatt, Foram N. Bangkok: Faculty of Architecture, Silpakorn University, Bangkok Thailand, 2024. International Seminar on Vernacular Settlements. pp. 398-412.

- Glassie, Henry. Vernacular Architecture (Material Culture). s.l. : Indiana University Press, 2000.

- Critical evaluation of socio cultural and climatic aspects in a traditional community: A case study of Pillayarpalayam weavers’ cluster, Kanchipuram. Vijayalaxmi, J. and Arathy, K. C. Kalam. 2022, Built Heritage. [CrossRef]

- Planned Productions of Vernacularized Dwellings and Settings in India: A Settlement in Baroda Designed by Balkrishna Doshi. Ferruses, Ignacio Juan, Dols, Sergio Artola and Gago, Clara Cantó. 3, 2024, International Society for the Study of Vernacular Settlements, Vol. 11, pp. 44-59.

- Lessons From Traditional Indian Housing. Manjerkar, Shraddha Mahore. 2021, pp. 134-138.

- Transformation Types of Transitional Spaces in The Local Dwelling in Iraq. Alanbaki, J H and Almoqaram, A M. 2021, IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Habraken, N. John, Mignucci, Andrés and Teicher, Jonathan. Conversations With Form. Glasgow : Routledge, 2014.

- Pol’s houses in Ahmedabad: The evolution of architectural elements and their influence on community living. Jaglan, Amit Kumar, Korde, Neha and Patel, Prachi. s.l. : Faculty of Architecture, Silpakorn University, Bangkok Thailand, 2024. International Seminar on Vernacular Settlements. pp. 369-379.

- Mistry, Nilika Nipambhai. The Walled city of Ahmedabad: Proposing a new framework for the conservation and maintenance of pol houses through analysis of the roles of different stakeholders. Columbia : Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, Columbia University, 2018.

- Baradi, Kaninik. A Framework for Testing and Repair of Timber Members: Assessment of Traditional Pol Houses in Ahmedabad. Ahmedabad : CEPT, May 2019.

- Kaza, Krystina. The Otla: A ‘Free Space’ in Balkrishna Doshi’s Aranya Settlement. Moratuwa : Faculty of Architecture Research Unit(FARU), University of Moratuwa, 2010.

- Desai, Madhavi. Traditional Architecture: House Form of the Islamic Community of Bohras in Gujarat. Hyderabad : National Institute of Advanced Studies in Architecture, 2007.

- Architectural Spaces as Socio-Cultural Connectors: Lessons from the Vernacular Houses of Lucknow, India. Gulati, Ritu, et al. 4, 2019, International Society for the Study of Vernacular Settlements, Vol. Vol. 6, pp. 30-48.

- Assessment of Traditional Architecture of Lucknow with reference to the Climatic Responsiveness. Kamal, Mohammad Arif. 1, 2021, Architecture and Engineering, Vol. Vol. 6, pp. 19-31.

- A Comparative Study of Transformations in Traditional House Form: The Case of Nagpur Region, India. Kotharkar, Rajashree. 2, March 2012, International Society for the Study of Vernacular Settlements, Vol. Vol. 2, pp. 17-33.

- Transforming Lifestyles and Evolving Housing Patterns: A Comparative Case Study. Khan, Smita and Bele, Archana. 2, June 2016, Open House International, Vol. Vol. 41, pp. 76-86. [CrossRef]

- Dengle, Narendra. The Introvert and the Extrovert Aspects of the Marathi House. [ed.] I. P. Glushkova and Anne Feldhaus. House and Home in Maharashtra. s.l. : Oxford University Press, 1998, pp. 50-69.

- Traditional Approach towards Contemporary Design: A Case Study. Dhepe, Sushama S. and Valsson, Dr. Sheeba. 3, March 2017, Journal of Engineering Research and Application, Vol. Vol. 7, pp. 12-22.

- Architecture: An Heirloom in the Context of Chettinad, India. Patwardhan, Asmita. Athens : Athens Institute for Education and Research, 2018. ATINER’s Conference Paper Series ARC2017-2393.

- Ślączka, Anna A. Mansions of Chettinad, Aziatische Kunst. 2018. Vol. Vol. 47, 3, pp. 55-57.

Figure 2.

Map of India showing the four locations of the settlements. Drawing by author.

Figure 2.

Map of India showing the four locations of the settlements. Drawing by author.

Figure 3.

(i) Plan of Pol Settlement (ii) Diagram of Pol-settlement system (iii) Morphology of threshold spaces. Drawing by author after Lisa Periera, 2019 (18)

Figure 3.

(i) Plan of Pol Settlement (ii) Diagram of Pol-settlement system (iii) Morphology of threshold spaces. Drawing by author after Lisa Periera, 2019 (18)

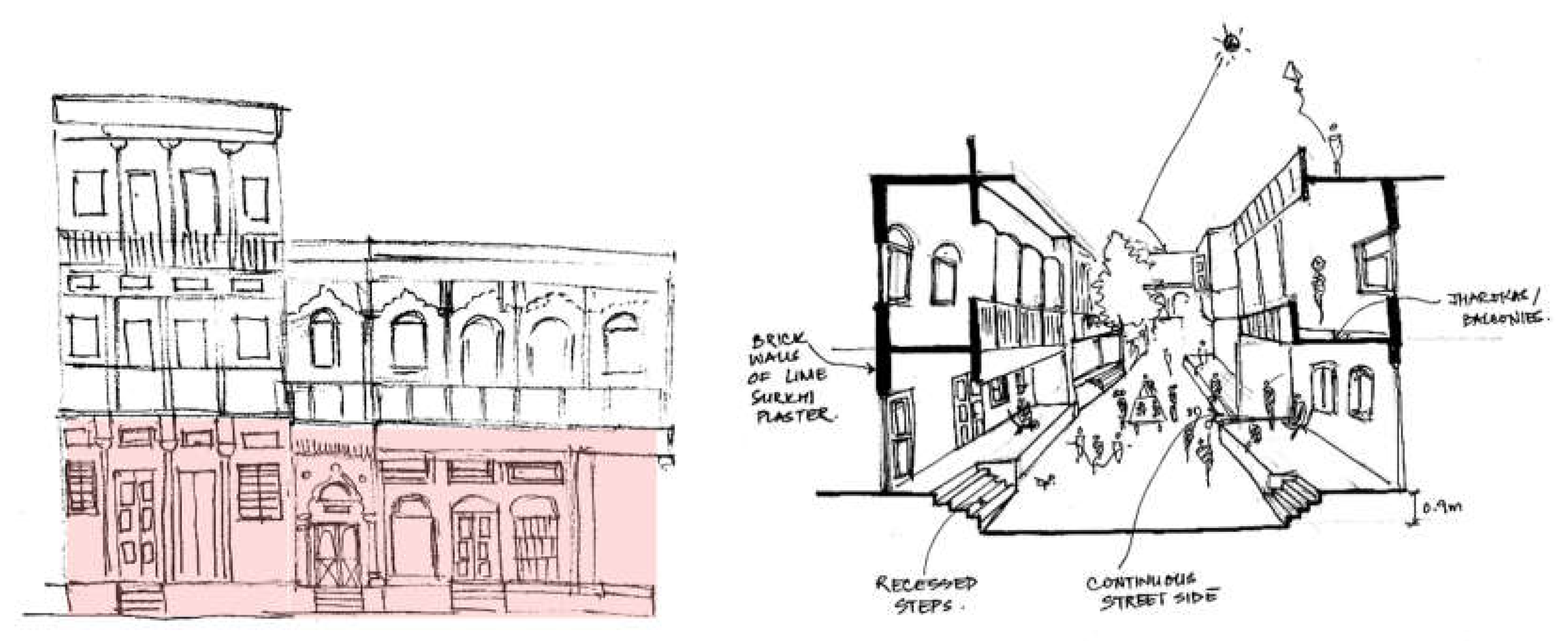

Figure 4.

Representation of activities in Pol settlement through ground floor elevation and street plan. Drawing by author.

Figure 4.

Representation of activities in Pol settlement through ground floor elevation and street plan. Drawing by author.

Figure 5.

(i) Plan & (ii) Section of typical Pol house (iii) Plan of Otla. Drawings by author.

Figure 5.

(i) Plan & (ii) Section of typical Pol house (iii) Plan of Otla. Drawings by author.

Figure 6.

(i) Facade of Pol houses highlighting otla & (ii) Perspective section through otla and street. Drawing by author.

Figure 6.

(i) Facade of Pol houses highlighting otla & (ii) Perspective section through otla and street. Drawing by author.

Figure 7.

(i) Location of the settlement studied with respect to major landmarks of the city (ii) Diagrammatic representation of Narhai settlement. Drawing by author after Gulati, 2019 (21).

Figure 7.

(i) Location of the settlement studied with respect to major landmarks of the city (ii) Diagrammatic representation of Narhai settlement. Drawing by author after Gulati, 2019 (21).

Figure 8.

Representation of activities in Narhai settlement through ground floor elevation and street plan. Drawing by author.

Figure 8.

Representation of activities in Narhai settlement through ground floor elevation and street plan. Drawing by author.

Figure 9.

: (i) Plan & (ii) Section of typical Narhai house (iii) Plan of Chabutra. Drawings by author

Figure 9.

: (i) Plan & (ii) Section of typical Narhai house (iii) Plan of Chabutra. Drawings by author

Figure 10.

(i) Facade of Narhai houses highlighting Chabutra & (ii) Perspective section through Chabutra and street. Drawings by author.

Figure 10.

(i) Facade of Narhai houses highlighting Chabutra & (ii) Perspective section through Chabutra and street. Drawings by author.

Figure 11.

Urban fabric of Mahal. Drawing by author after Kotharkar,2012 (23)

Figure 11.

Urban fabric of Mahal. Drawing by author after Kotharkar,2012 (23)

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic representation of Wadas. Drawing by author.

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic representation of Wadas. Drawing by author.

Figure 2.

Representation of activities in Wada settlement through elevation and street plan. Drawing by author.

Figure 2.

Representation of activities in Wada settlement through elevation and street plan. Drawing by author.

Figure 3.

(i) Plan & (ii) Section of typical Wada (iii) Plan of Osari. Drawings by author.

Figure 3.

(i) Plan & (ii) Section of typical Wada (iii) Plan of Osari. Drawings by author.

Figure 4.

Perspective section through Osari and the street. Drawing by author.

Figure 4.

Perspective section through Osari and the street. Drawing by author.

Figure 5.

(i) Settlement pattern of Kanadukatham. (ii) Schematic representation of settlement system showing some activities. Drawings by author.

Figure 5.

(i) Settlement pattern of Kanadukatham. (ii) Schematic representation of settlement system showing some activities. Drawings by author.

Figure 6.

(i) Plan & (ii) Section of typical Chettiar house. Drawings by author.

Figure 6.

(i) Plan & (ii) Section of typical Chettiar house. Drawings by author.

Figure 18.

(i) Plan & (ii) Section through Mugappu. Drawings by author.

Figure 18.

(i) Plan & (ii) Section through Mugappu. Drawings by author.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of the four threshold spaces.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of the four threshold spaces.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).