1. Introduction

The recent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to major challenges in healthcare management [

1,

2,

3]. The increased and fluctuating demand for emergency and intensive care over many months and seasons was in contrast to limited staff, equipment and infrastructure, counteracting capacity building and expansion. Surge capacities in hospitals could only be created by reducing elective care, lower inflow of other emergency patients, and structural reorganizations of wards and personnel. Substantial disruptions to primary care and public health interventions such as lockdowns, stay-at-home orders, school closures, and travel restrictions, added further extraordinary constraints on healthcare services and coordination between primary and secondary care. In addition, in the early stages of the pandemic there have been slow flow of information and much uncertainty about the resources, type of healthcare and knowledge needed for adequate COVID-19 management. In this context, concern was expressed about possible overtreatment of patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 and pulmonary infiltrates and about the risk of nosocomial transmission of potential pathogens with subsequent further increase of antimicrobial treatment [

4,

5,

6]. The published data on these topics, however, have been conflicting and show that the impact of the pandemic on antimicrobial drug use has been highly variable.

In European countries, monitoring antimicrobial consumption by the ECDC has shown a consistent decrease in community prescribing of antibiotics during the COVID-19 pandemic [

7,

8]. Twenty-six out of 27 EU/EEA countries reporting data for the period 2019 through 2022 have observed a decreasing antibiotic use in 2020 compared with 2019, and most reported a similar decrease persisting in 2021 and a rebound in 2022. Patterns of in-hospital prescribing of antibiotics in Europe, in contrast, have been less clear and more varying [

8]. In 2020, only 17 out of 26 countries reporting hospital consumption of antibiotics showed a decrease compared with 2019. This number increased to 21 for 2021 and decreased again to 17 in 2022, with relative changes of roughly -2% and -8% in the population-weighted mean (hospital) consumption in 2020 and 2021 compared to 2019, respectively.

We were interested to assess the pandemic-associated changes in hospital consumption of antibacterial and antifungal drugs in German acute care hospitals. So far, this data has not been included in the ECDC annual report. Due to the large population in Germany the data add relevant information in assessing the overall trends in population-weighted community versus inpatient antibiotic prescribing associated with the pandemic in Europe. They also provide evidence for inpatient prescribing of antifungal drugs that was dissimilar to trends in hospital antibacterial drug consumption.

2. Results

A total of 279 acute care hospitals were included.

Table 1 shows that most of the hospitals were small-sized and more often located in Western Germany than in the East or South. They represented 18% of all general hospitals in Germany and 23% of nationally reported patient days for general hospitals. Very small hospitals were underrepresented in the sample. Seven hospitals were excluded from the analysis of antifungal drugs because of incomplete data.

2.1. Changes in Patient Days and Drug Volumes

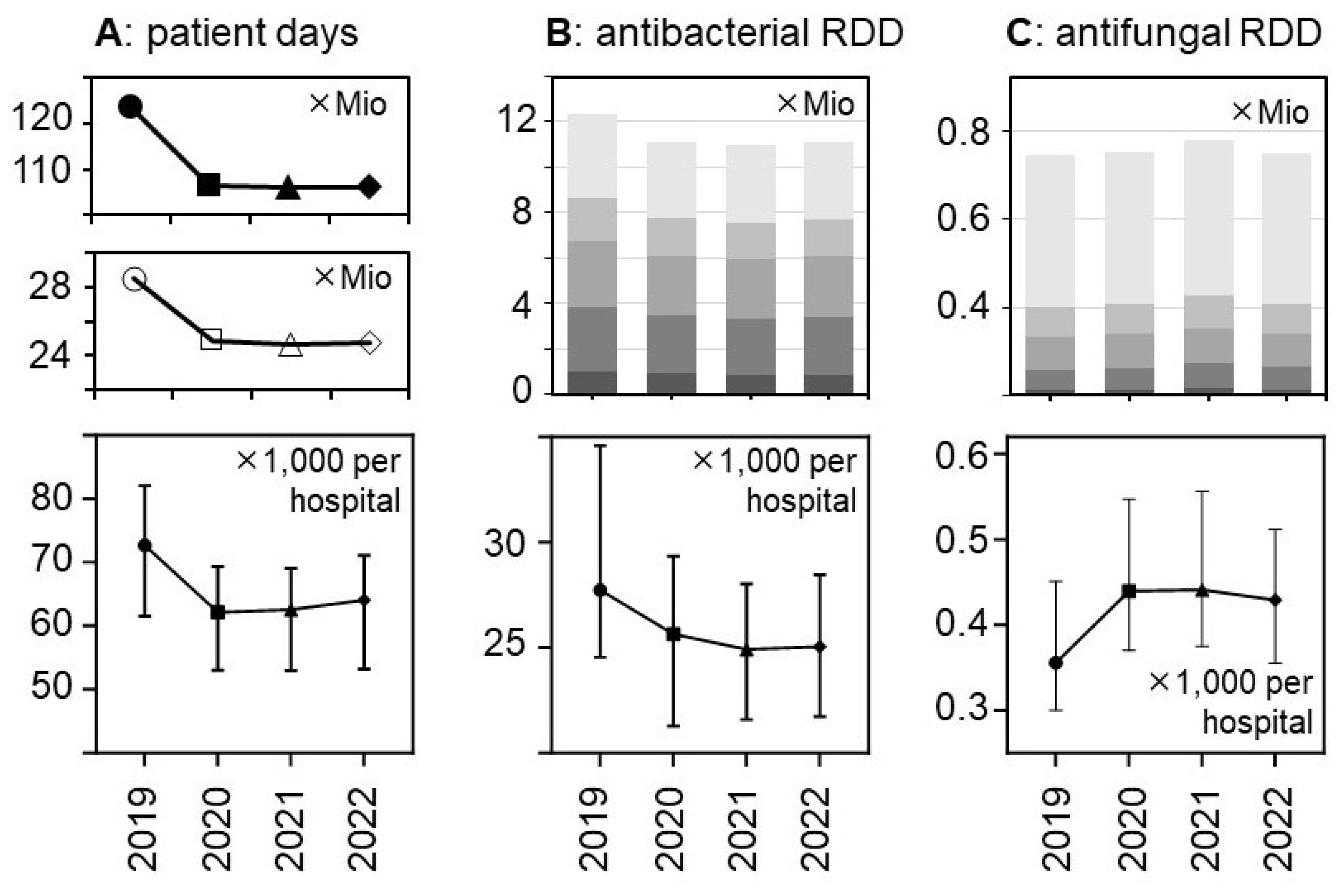

There was a major reduction in hospital bed occupancy in 2020 that persisted in 2021 and 2022 and resulted in substantial decreases in the total number of patient days from 28.5 mio in 2019 to <25 mio in the subsequent years (

Figure 1 and Suppl.

Table S1). The relative decreases were similar in the different hospital strata and consistent with the national decrease. They were statistically significant in a hospital-level analysis (

Figure 1), with median numbers of patient days (✕1,000) per hospital (± 95%CI) changing from 72.68 (91.7-112.9) in 2019 to 62.16 (79.7-98.7), 62.54 (78,82 98,08), and 64.06 (79.1-98.2) in the following years 2020, 2021, and 2022, respectively (p<0.0001 for each comparison).

The total volumes of dispensed antibacterial drugs (in RDD) also decreased by roughly 10% while the volume of antifungal drugs increased, in particular in 2021 (+6.4% versus +1.4% in 2020 and +0.4% in 2022, respectively) (

Figure 1 and

Table 2). These trends appeared to be consistent across the hospital size/type strata (

Table 2, Suppl.

Table S1) and were statistically significant (

Figure 1).

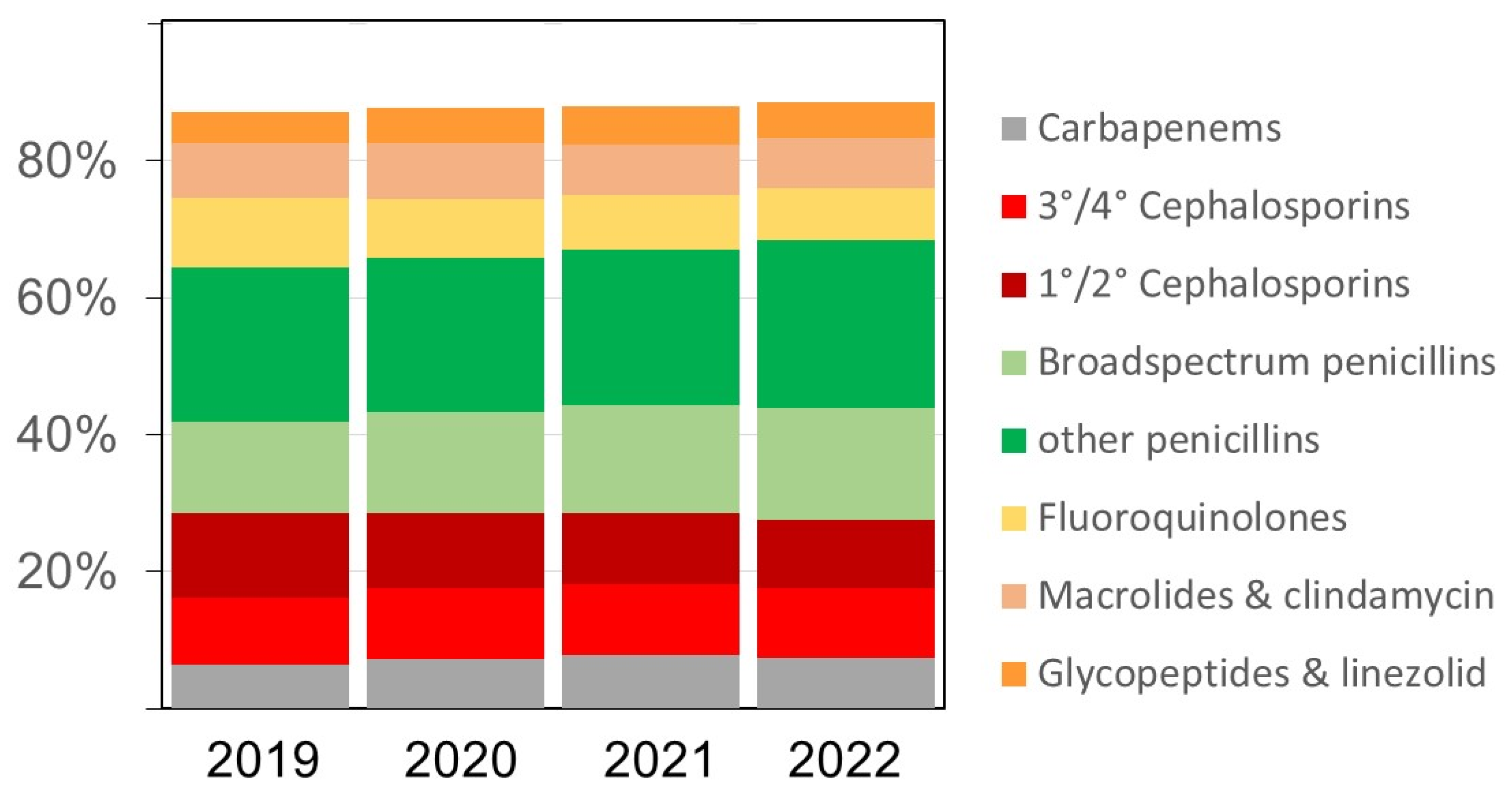

The overall pattern of antibacterial drugs/drug classes over time remained similar (

Figure 2), but we observed several relevant changes. The proportion of carbapenems among all antibiotics, for example, increased from 6.4% in 2019 to 7.2% in 2020, 7.7% in 2021, and 7.4%, respectively. The proportion of broad-spectrum penicillins (essentially piperacillin-tazobactam) doses also increased in the same time from 13.5% in 2019 to 14.7%, 15.8%, and 16.2% (in 2020, 2021, and 2022), respectively. Substantial relative (and absolute) decreases were observed for fluoroquinolones and first/second generation cephalosporins while there were no major changes over time in the volumes of macrolides (

Figure 2 and Suppl.

Table S2). The increases in antifungal drug prescribing primarily affected echinocandins and azoles other than fluconazole (data not shown).

2.2. Drug Use Density Trends

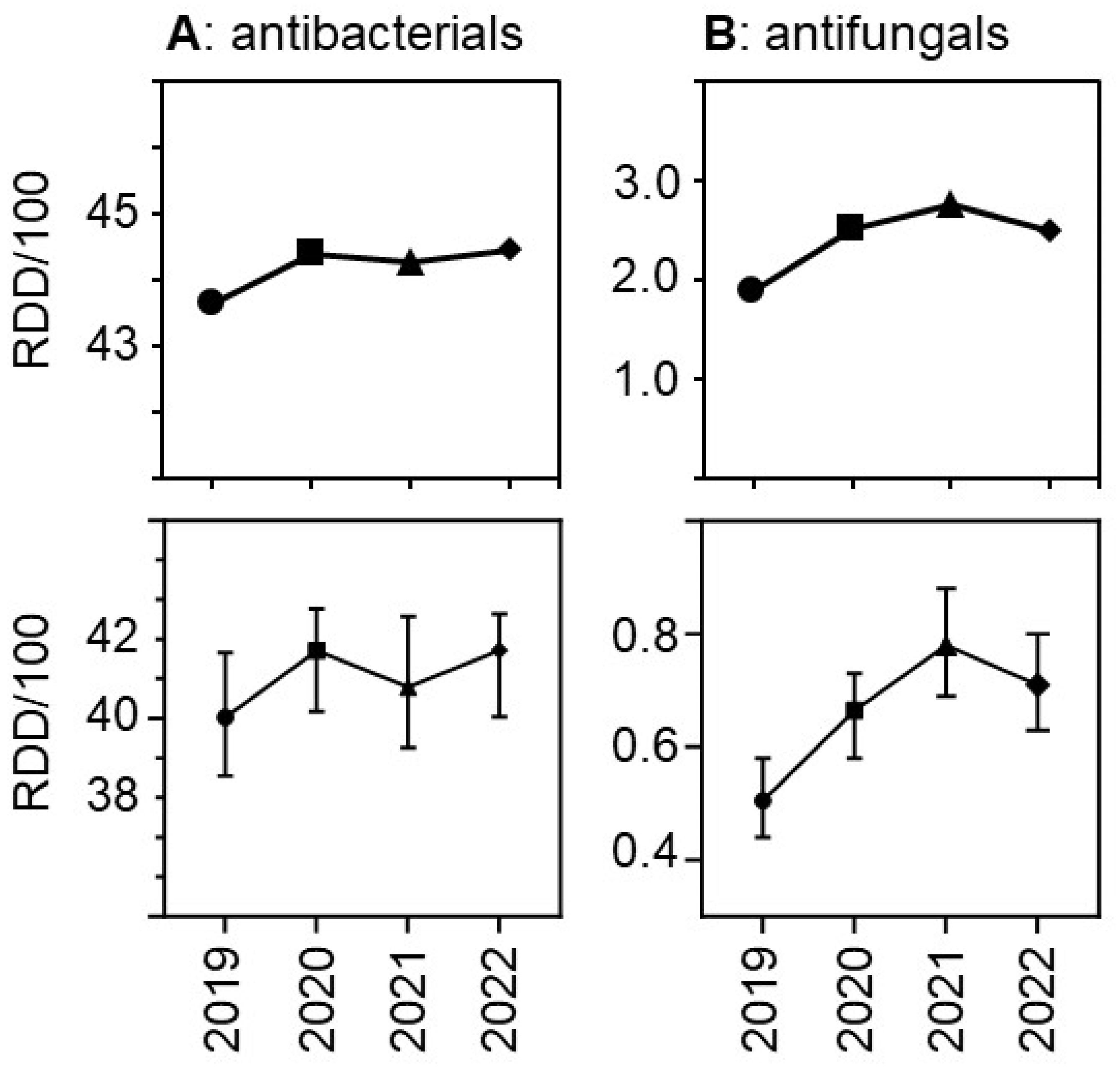

Due to the relatively greater reduction in patient days versus drug volumes the use density (in RDD per 100 patient days per hospital) increased.

Figure 3 shows the trends over time both for antibacterial and for antifungal drugs. The relative increase was greater for antifungal drugs than for antibacterial drugs, with a peak for antifungals observed in 2021. As expected, drug use density was much higher in university hospitals than in the other participant hospitals, but the trends over time in the different hospital strata were similar (Suppl.

Figure S1).

We confirmed some of the changes in the use density for different antibacterial drug classes that were expected based on the changes in the drug volumes. For example, increasing use density was observed for piperacillin-tazobactam (as the main broad-spectrum penicillin) and for carbapenems, but there was no increased inpatient prescribing of macrolides and clindamycin associated with the pandemic (Suppl.

Figure S2). Most of the trends appeared to be consistent across the different hospital strata (Suppl.

Figure S2). The use densities for fluoroquinolines and first- and second-generation cephalosporins clearly decreased during the study period, the latter most likely due to the reduced need for prophylaxis in elective surgery.

Antibacterial drug use density was consistently lower in the East than in the other regions (Suppl.

Figure S1), but the number of participant hospitals from the East was low. In addition, the proportion of very small and small hospitals was higher in the East and may account for these findings. The increase over time seemed to occur later in the East than in the other regions (Suppl.

Figure S1). Antifungal drug use density per hospital in the three regions, in contrast, showed similar levels over time, with peaks in 2021 (Suppl.

Figure S1).

2.3. Sensitivity Analyses Using Antibacterial DDD and Extrapolation to National Con-Sumption

The results for the antibacterial drugs were similar when DDD were used instead of RDD (Suppl.

Figure S3), but generally and as expected [

9,

10], the values were higher. Total volumes decreased (Suppl.

Table S1) and the drug use density increased slightly (Suppl.

Figure S3). These trends were significant in an hospital level analysis (data not shown). The total DDD volumes were extrapolated to the national general hospital system and population taking into account the hospital size. The resulting national estimates for total hospital consumption (suppl. table 3) normalised to the general population (per 1,000 population and day) changed from 2.07 in 2019 to 1.84 in 2020 and remained similar (1.81 and 1.80) in 2021 and 2022, respectively. Since these calculations did not include pediatric divisions, psychiatry/psychosomatics hospital services and other non-general (monospecialty) hospitals, the true values are likely to be somewhat higher.

3. Discussion

The major finding of this study was that the total volumes of antibacterial drugs, but not of antifungal drugs decreased with the reduced hospital bed occupancy in 2020 and thereafter in association with pandemic changes. The overall decrease of roughly 10% in hospital consumption of antibacterial drugs is relevant and noteworthy. In our opinion it was primarily driven by the constraints on healthcare services during the pandemic and the associated structural changes with the reorganization of wards, less elective care, more intensive care and increased emergency admission of elderly patients with complex and probably more advanced diseases [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

Reduced hospital consumption of antibiotics associated with the pandemic has been observed in a majority of, but not all European countries as reported by the ECDC [

8]. Interestingly, the reduced consumption appeared to be enhanced in 2021 and attenuated in 2022, a pattern that we did not observe in Germany. More in depth-analyses with additional information on use density values are available from several European countries, but some of these evaluations only cover the first or first two years of the pandemic. In Italy and France, for example, no increased use density was observed in 2020 compared with 2019 [

16,

17]. Switzerland reported an overall decrease in hospital antibiotic consumption in 2020 compared with 2019, and a simultaneous (small) increase in antibiotic use density that primarily included broad-spectrum antibiotics [

18,

19]. Conversely, studies from Hungary and Croatia reported a massive increase in hospital antibiotic use density in 2020 with no decrease in overall consumption [

20,

21]. Similar to the findings in the present study, Denmark reported a large increase in antibiotic use density after 2019 that persisted (at least) until 2022 while the total consumption decreased [

22]. Decreasing overall antibiotic consumption in hospitals in 2020 and 2021 compared with 2019 was also seen in Sweden and the Netherlands [

23,

24]. In Dutch hospitals the inpatient antibiotic use density increased at the same time between 2019 and 2020. Together with reports from other European and non-European countries [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30], these investigations show varying trends although reports of increased hospital antibiotic use density prevail. An important factor for the variability likely was the differential pandemic dynamics across (European) countries and regions and the varying type and timing of public health interventions, structural changes in the hospital systems and primary care in response to these dynamics. It will be interesting to evaluate longer term trends in those countries for which the reports had focussed only on the immediate changes associated with the first or first and second pandemic surges.

A second important finding of this study was the impact on broad-spectrum antibiotic prescribing, notably carbapenems and piperacillin-tazobactam, and on antifungal prescribing which increased while most other drug classes (with the exception of glycopeptides/linezolid) decreased in total dispensed volumes and some decreased even in use density. Such a pandemic-associated shift towards broad-spectrum betalactams has been described by other investigators [

6,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35], but less is known about the trends in hospital prescribing of antifungals. Hospital-onset invasive Candida infection and, more rarely, mould infections have been associated with severe COVID-19 cases. Epidemiological studies documented increased incidences following pandemic waves [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. Predisposing factors in this context are immunosuppressants which were recommended as adjunctive therapies in severe COVID-19 patients as early as 2020 (dexamethasone) and 2021 (anti-IL-6) [

43,

44,

45,

46]. There has been some concern about the role of early invasive versus non-invasive ventilation and the frequent extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) therapies that have likely increased the risk for superinfection. Predisposing factor in this contextmay also have been the increased prescribing of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Both broad-spectrum antibiotics and antifungal agents may have also been (too) often empirically prescribed because of clinical and diagnostic uncertainties, in particular in long-stay intensive care patients [

47,

48].

Few studies have examined the impact these developments had on antifungal drug consumption. In Dutch and Spanish hospitals, antifungal use density increased by 10-12% in 2020 compared to 2019 [

24,

25]. Four French health centres observed an increase in voriconazole consumption in 2020 compared with 2019 which was particularly large in intensive care [

49]. In a study from the United Kingdom there was no change in inpatient antifungal prescribing [

50]. In the most recent ECDC report [

8], the total consumption (combining community and hospital sectors if data available) of systemic antifungals (excluding terbinafin) in the population decreased in 2020 in a majority of reporting countries, but this finding is difficult to interpret since hospital prescribing could not specifically be evaluated. We are not aware of other multicenter studies examining longer term trends of inpatient antifungal prescribing covering pandemic associated changes.

The strength of the present study is the relatively large number of hospitals with complete data over the four years of study with the option to perform stratified analysis according to hospital size and repeated measures analyses. A limitation may be the annual (instead of quarterly) data that may have not captured the shorter term dynamic trends associated with pandemic waves and responses which may vary even in the different regions of the same country. Another limitation is that the (pre-pandemic) baseline period covered only one year, not taking into account the previous variations in hospital drug use over time. Finally, the metrics we used – RDD and DDD instead of days of therapy, normalisation with patient days versus with admissions – have their inherent limitations that need to be considered when interpreting and comparing the results.

In summary, we show that in one of the largest EU countries the total volume of antibacterial drugs prescribed in acute care hospitals substantially decreased with the pandemic without a rebound phenomenon in 2022 which is relevant on the population level. Inpatient prescribing, particularly of broadspectrum antibiotics but also of systemic antifungal agents, however, increased, presumably related to the different case mix in the pandemic situation and more vulnerable and critically ill patients.

4. Materials and Methods

We used data collected by the so-called ADKA-if-DGI surveillance programme (

www.antiinfektiva-surveillance.de) which receives data from hospital pharmacies on dispensed antimicrobial drugs and patient days (occupied bed days) as denominator. The drug use volumes are converted into hospital-adapted “recommended” daily doses (RDD) and WHO-ATC defined daily doses (DDD, 2023 version) and usually expressed as RDD (DDD) per 100 patient days (RDD/100 or DDD/100). Comprehensive quarterly reports are compiled and made available to the antimicrobial stewardship teams of each participant hospital for feedback purposes. Acute care hospitals participating continuously in this (non-compulsory) programme in the years 2019 through 2022 and having reported complete data were included in the present analysis. The data comprised all drugs of the ATC groups J01 and J02, and J04AB02 (rifampicin, if not given as fixed combination), dispensed to all inpatient divisions of a given hospital except psychiatry/psychosomatics and pediatrics.

We calculated total volumes, pooled means and medians (with 95% confidence intervals) per hospital and per 100 patient days. Comparisons of absolute counts between the years are reported as relative differences (in percentages). The statistical significance of changes over time was assessed by the non-parametric Friedman test for repeated paired group measures and Dunn’s multiple pairwise comparison (2019 versus each of the following years) with a Bonferroni adjustment (as post-hoc test). Statistical tests were two-tailed and considered significant if the p value was <0.05, calculated with GraphPad Prism V.6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Additional exploration of the data included the influence of hospital location (East, West, South) and hospital size strata: very small hospitals (<200 beds), small hospitals (200-399 beds), medium-sized hospitals (400-800 beds) and large hospitals (>800 beds). Among the large hospitals, university hospitals were evaluated separately.

For the comparison with national data and an extrapolation of the DDD results we used the annual data published by the Federal Office of Statistics (

www.destatis.de) for general hospitals (with the corresponding hospital size/type strata) and the total population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1; Figure S2; Figure S3; Table S1; Table S2; Table S3.

Author Contributions

Winfried V. Kern: conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, resources, visualisation, formal analysis, supervision, writing the original draft, reviewing and editing the manuscript; Michaela Steib-Bauert: methodology, formal analysis, data curation and validation; Jürgen Baumann: resources, supervision, reviewing and editing the manuscript; Evelyn Kramme: reviewing and editing the manuscript; Gesche Först: reviewing and editing the manuscript; Katja de With: conceptualisation, supervision, reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors have seen and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was in part supported by the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF) (grant TTU 08.817) and the Akademie für Infektionsmedizin.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The ADKA-if-DGI surveillance system routinely collects anonymised surveillance data on antimicrobial drugs dispensed in acute care hospitals. Ethical consent was not required according to the German law for research on human beings.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared in aggregated form on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participating hospitals for providing their data.

Use of Artificial Intelligence Tools

Artificial intelligence was not used in this work.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

- Haldane V: de Foo C, Abdalla SM, Jung AS, Tan M, Wu S, et al. Health systems resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from 28 countries. Nat Med 2021; 27:964-80. [CrossRef]

- Moynihan R, Sanders S, Michaleff ZA, Scott AM, Clark J, To EJ, et al.. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on utilisation of healthcare services: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2021; 11:e045343. [CrossRef]

- Zhao L, Jin Y, Zhou L, Yang P, Qian Y, Huang X, Min M. Evaluation of health system resilience in 60 countries based on their responses to COVID-19. Front Public Health 2023; 10:1081068. [CrossRef]

- O'Toole RF. The interface between COVID-19 and bacterial healthcare-associated infections. Clin Microbiol Infect 2021; 27:1772-6. [CrossRef]

- Nandi A, Pecetta S, Bloom DE. Global antibiotic use during the COVID-19 pandemic: analysis of pharmaceutical sales data from 71 countries, 2020-2022. EClinicalMedicine 2023; 57:101848. [CrossRef]

- Langford BJ, Soucy JR, Leung V, So M, Kwan ATH, Portnoff JS, et al. Antibiotic resistance associated with the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2023; 29:302-9. [CrossRef]

- Ventura-Gabarró C, H Leung V, Vlahović-Palčevski V, Machowska A, Monnet DL, Diaz Högberg L, et al. Rebound in community antibiotic consumption after the observed decrease during the COVID-19 pandemic, EU/EEA, 2022. Euro Surveill 2023; 28:2300604. [CrossRef]

- Antimicrobial consumption in the EU/EEA (ESAC-Net) - Annual Epidemiological Report 2022. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), Stockholm 2023.

- Först G, de With K, Weber N, Borde J, Querbach C, Kleideiter J, et al. Validation of adapted daily dose definitions for hospital antibacterial drug use evaluation: a multicentre study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017; 72:2931-37. [CrossRef]

- Nunes PHC, Moreira JPL, Thompson AF, Machado TLDS, Cerbino-Neto J, Bozza FA. Antibiotic consumption and deviation of prescribed daily dose from the Defined Daily Dose in critical care patients: a point-prevalence study. Front Pharmacol 2022; 13:913568. [CrossRef]

- Jaehn P, Holmberg C, Uhlenbrock G, Pohl A, Finkenzeller T, Pawlik MT, et al. Differential trends of admissions in accident and emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. BMC Emerg Med 2021; 21:42. [CrossRef]

- Schranz M, Boender TS, Greiner T, Kocher T, Wagner B, Greiner F, et al. Changes in emergency department utilisation in Germany before and during different phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, using data from a national surveillance system up to June 2021. BMC Publ Health 2023; 23:799. [CrossRef]

- Oettinger V, Stachon P, Hilgendorf I, Heidenreich A, Zehender M, Westermann D, et al. COVID-19 pandemic affects STEMI numbers and in-hospital mortality: results of a nationwide analysis in Germany. Clin Res Cardiol 2023; 112:550-557. [CrossRef]

- Koch F, Hohenstein S, Bollmann A, Meier-Hellmann A, Kuhlen R, Ritz JP. Cholecystectomies in the COVID-19 pandemic during and after the first lockdown in Germany: an analysis of 8561 patients. J Gastrointest Surg 2022; 26:408-13. [CrossRef]

- Leiner J, Hohenstein S, Pellissier V, König S, Winklmair C, Nachtigall I, et al. COVID-19 and severe acute respiratory infections: monitoring trends in 421 German hospitals during the first four pandemic waves. Infect Drug Resist 2023; 16:2775-81. [CrossRef]

- Perrella A, Fortinguerra F, Pierantozzi A, Capoluongo N, Carannante N, Lo Vecchio A, et al. Hospital antibiotic use during COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Antibiotics 2023; 12:168. [CrossRef]

- Roger PM, Lesselingue D, Gérard A, Roghi J, Quint P, Un S, et al. Antibiotic consumption 2017-2022 in 30 private hospitals in France: impact of antimicrobial stewardship tools and COVID-19 pandemic. Antibiotics 2024; 13:180. [CrossRef]

- Swiss Antibiotic Resistance Report 2022 – Usage of Antibiotics and Occurrence of Antibiotic Resistance in Switzerland. Federal Office of Public Health and Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office, November 2022.

- Friedli O, Gasser M, Cusini A, Fulchini R, Vuichard-Gysin D, Tobler RH et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on inpatient antibiotic consumption in Switzerland. Antibiotics 2022; 11:792. [CrossRef]

- Ruzsa R, Benkő R, Hambalek H, Papfalvi E, Csupor D, Nacsa R, et al. Hospital antibiotic consumption before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Hungary. Antibiotics 2024; 13:102. [CrossRef]

- Vlahović-Palčevski V, Rubinić I, Payerl Pal M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital antimicrobial consumption in Croatia. J Antimicrob Chemother 2022; 77:2713-7. [CrossRef]

- DANMAP 2022 – Use of antimicrobial agents and occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria from food animals, food and humans in Denmark. National Food Institute & Statens Serum Institut, Lyngby/Copenhagen 2023.

- A report on Swedish Antibiotic Sales and Resistance in Human Medicine (SWEDRES) and Swedish Veterinary Antibiotic Resistance Monitoring (SVARM) 2022. Public Health Agency of Sweden & National Veterinary Institute, Solna/Uppsala 2023.

- NethMap 2022 – Consumption of antimicrobial agents and antimicrobial resistance among medically important bacteria in the Netherlands in 2021. SWAB – the Dutch Foundation of the Working Party on Antibiotic Policy & RIVM – the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment of the Netherlands, 2022.

- Grau S, Hernández S, Echeverría-Esnal D, Almendral A, Ferrer R, Limón E, et al. Antimicrobial consumption among 66 acute care hospitals in Catalonia: impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Antibiotics 2021; 10:943. [CrossRef]

- Aldeyab MA, Crowe W, Karasneh RA, Patterson L, Sartaj M, Ewing J, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on antibiotic consumption and prevalence of pathogens in primary and secondary healthcare settings in Northern Ireland. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2023; 89:2851-66. [CrossRef]

- Hussein RR, Rabie ASI, Bin Shaman M, Shaaban AH, Fahmy AM, Sofy MR, et al. Antibiotic consumption in hospitals during COVID-19 pandemic: a comparative study. J Infect Dev Ctries 2022; 16:1679-86. [CrossRef]

- O'Leary EN, Neuhauser MM, Srinivasan A, Dubendris H, Webb AK, Soe MM, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on inpatient antibiotic use in the United States, January 2019 through July 2022. Clin Infect Dis 2024; 78:24-6. [CrossRef]

- Patel TS, McGovern OL, Mahon G, Osuka H, Boszczowski I, Munita JM, et al. Trends in inpatient antibiotic use among adults hospitalized during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 pandemic in Argentina, Brazil, and Chile, 2018-2021. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 77(Suppl 1):S4-11. [CrossRef]

- Kim B, Hwang H, Chae J, Kim YS, Kim DS. Analysis of changes in antibiotic use patterns in Korean hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Antibiotics 2023; 12:198. [CrossRef]

- Russell CD, Fairfield CJ, Drake TM, Turtle L, Seaton RA, Wootton DG, et al. Co-infections, secondary infections, and antimicrobial use in patients hospitalised with COVID-19 during the first pandemic wave from the ISARIC WHO CCP-UK study: a multicentre, prospective cohort study. Lancet Microbe 2021; 2:e354-65. [CrossRef]

- Allel K, Peters A, Conejeros J, Martínez JRW, Spencer-Sandino M, Riquelme-Neira R, et al. Antibiotic Consumption During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic and Emergence of Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Lineages Among Inpatients in a Chilean Hospital: A Time-Series Study and Phylogenomic Analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 77(Suppl 1):S20-8. [CrossRef]

- Abubakar U, Al-Anazi M, Alanazi Z, Rodríguez-Baño J. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on multidrug resistant gram positive and gram negative pathogens: a systematic review. J Infect Public Health 2023; 16:320-31. [CrossRef]

- Sili U, Tekin A, Bilgin H, Khan SA, Domecq JP, Vadgaonkar G, et al. Early empiric antibiotic use in COVID-19 patients: results from the international VIRUS registry. Int J Infect Dis 2024; 140:39-48. [CrossRef]

- Durà-Miralles X, Abelenda-Alonso G, Bergas A, Laporte-Amargós J, Sastre-Escolà E, Padullés A, et al. An Ocean between the Waves: Trends in Antimicrobial Consumption in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. Antibiotics 2024; 13:55. [CrossRef]

- Hoenigl M, Seidel D, Sprute R, Cunha C, Oliverio M, Goldman GH, et al. COVID-19-associated fungal infections. Nat Microbiol 2022; 7:1127-40. [CrossRef]

- Bretagne S, Sitbon K, Botterel F, Dellière S, Letscher-Bru V, Chouaki T, et al. COVID-19-associated aspergillosis, fungemia, and pneumocystosis in the intensive care unit: a retrospective multicenter observational cohort during the first French pandemic wave. Microbiol Spectr 2021; 9:e0113821. [CrossRef]

- Elbaz M, Korem M, Ayalon O, Wiener-Well Y, Shachor-Meyouhas Y, Cohen R, et al. Invasive fungal diseases in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Israel: a multicenter cohort study. J Fungi 2022; 8:721. [CrossRef]

- Gangneux JP, Dannaoui E, Fekkar A, Luyt CE, Botterel F, et al. Fungal infections in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 during the first wave: the French multicentre MYCOVID study. Lancet Respir Med 2022; 10:180-90. [CrossRef]

- Koulenti D, Karvouniaris M, Paramythiotou E, Koliakos N, Markou N, Paranos P, et al. Severe Candida infections in critically ill patients with COVID-19. J Intensive Med 2023; 3:291-7. [CrossRef]

- Prigitano A, Blasi E, Calabrò M, Cavanna C, Cornetta M, Farina C, et al. Yeast bloodstream infections in the COVID-19 patient: a multicenter Italian study (FiCoV Study). J Fungi 2023; 9:277. [CrossRef]

- Zuniga-Moya JC, Papadopoulos B, Mansoor AE, Mazi PB, Rauseo AM, Spec A. Incidence and mortality of COVID-19-associated invasive fungal infections among critically ill intubated patients: a multicenter retrospective cohort analysis. Open Forum Infect Dis 2024; 11:ofae108. [CrossRef]

- Leistner R, Schroeter L, Adam T, Poddubnyy D, Stegemann M, Siegmund B, et al. Corticosteroids as risk factor for COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis in intensive care patients. Crit Care 2022; 26:30. [CrossRef]

- Prattes J, Wauters J, Giacobbe DR, Salmanton-García J, Maertens J, Bourgeois M, et al. Risk factors and outcome of pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill coronavirus disease 2019 patients-a multinational observational study by the European Confederation of Medical Mycology. Clin Microbiol Infect 2022; 28:580-7. [CrossRef]

- de Hesselle ML, Borgmann S, Rieg S, Vehreshild JJ, Spinner CD, Koll CEM, et al. Invasiveness of ventilation therapy is associated to prevalence of secondary bacterial and fungal infections in critically ill COVID-19 patients. J Clin Med. 2022 Sep 5;11(17):5239. [CrossRef]

- Timsit JF. After SARS-CoV-2 pandemics: new insights into ICU-acquired pneumonia. J Clin Med 2023; 12:2160. [CrossRef]

- Crook P, Logan C, Mazzella A, Wake RM, Cusinato M, Yau T, et al. The impact of immunosuppressive therapy on secondary infections and antimicrobial use in COVID-19 inpatients: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2023 Nov 17;23(1):808. [CrossRef]

- Prasad PJ, Poles J, Zacharioudakis IM, Dubrovskaya Y, Delpachitra D, Iturrate E, et al. Coinfections and antimicrobial use in patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) across a single healthcare system in New York City: a retrospective cohort study. Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol 2022; 2:e78. [CrossRef]

- Bienvenu AL, Bestion A, Pradat P, Richard JC, Argaud L, Guichon C, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on antifungal consumption: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Crit Care 2022; 26:384. [CrossRef]

- Khan S, Bond SE, Lee-Milner J, Conway BR, Lattyak WJ, Aldeyab MA. Antimicrobial consumption in an acute NHS Trust during the COVID-19 pandemic: intervention time series analysis. JAC Antimicrob Resist 2024; 6:dlae013. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).