1. The Angst of Duration

As Herbert Spencer reminds us, we may attempt to ‘kill time’ but ultimately it is more likely that time will kill us [

1]. Time might arguably be described as our most precious personal resource. As we age, we increasingly mourn its passing as a harbinger of our own eventual disappearance. Yet, even an everyday level, anyone familiar with running late for an important event or sitting in a boring meeting can attest to the fact that to be over-aware of passing time is actually unpleasant.

Durations have extension, but they are also finite, and we seem to have a problem with both. On the one hand, knowing that every pleasant experience we have will eventually end is tinged with pathos, but on the other, uninteresting events that seem endless are also sources of discomfort. The two meanings of the word ‘endure,’ ‘to last over time’ and ‘to suffer, are not coincidental. Simply being aware of time, whether or not it is passing too quickly or too slowly for our liking, actually seems to make us uncomfortable. In a subtle reversal of the well-known saying that “time flies when we are having fun,” Aaron Sackett and his colleagues argue, for example, that we enjoy many activities primarily because they distract us from awareness of passing time. In other words, we actually have fun when time flies, and not the other way around [

2].

As Matthew Killingsworth and Daniel Gilbert explain, we also pay a psychological price for our ability to look forward and backwards in time, in the form of regret over past events that we cannot change and anxiety over things that may never happen [

3]. Little wonder, then, that time has been described both a ‘trauma’ and a ‘terror’ [

4,

5], or that humans have long sought to try and escape its relentless march through the notion of the timeless present.

There is good reason for this. Aristotle famously argued that ‘Time is only made up of the past and the future ... Now is not part of time at all’ [

6], and eight centuries later, St. Augustine went even further, insisting that the present is actually all there really is:

We live from that which is no more toward that which is not yet through a slender, fragile boundary called now that is too fugitive ever really to be laid hold of. Where, then, is time? .... The present alone exists, located in the mind, and having three foci: a present memory of past events, a present attention to present events, and a present anticipation of future events [

7].

If the experience of time is frequently uncomfortable to us, and the present somehow lies outside the temporal, then it would make sense that we would appreciate being immersed in events that keep us in the moment. How that objective may be achieved through the medium of architecture is the focus of this essay.

For Adrian Snodgrass, Augustine’s emphasis on the present as the only reality ‘is one variation on a theme shared by all the traditions: time is illusory; reality abides in the punctual present, standing at the junction of the past and future. What the dimensionless point is to spatial extension the timeless is to temporal duration and succession, just as the dimensionless point equates the Infinite, so the atemporal instant equates the Eternal’ [

8].

The ‘punctual present’ referred to here is a theoretical moment without duration that can be seen as representing the infinitely thin interface between the past and the future. Because such a fleeting moment cannot be experienced, however, for many this representation of the present fails to reflect what we know in everyday life as ‘now.’ The late nineteenth-century psychologist William James, for example, famously challenged the scientific notion of the present as a duration-less instant, arguing that what we experience subjectively as now can actually last several seconds [

9].

In the early 1960s, the Dutch modernist architect Aldo Van Eyck insisted similarly that ‘the present should never be understood as the shifting a-dimensional instant between past and future or as a closed shifting frontier between what is no longer and not yet is, but as a temporal span experience’ [

10,

11]. A decade later, the American urbanist Kevin Lynch made the same point more precisely, explaining that ‘the psychological present is not the philosopher’s dimensionless moment but a space of real duration, up to five seconds in length, but more usually less than two’[

12].

The writer Daniel Stern later expanded on this topic, suggesting that ‘common experience—our subjective sense of life as lived at the second-by-second local level—does not sit well with the idea that the present has no thickness. The experience of listening to music, watching dance, or interacting with someone requires a present with a duration’[

13, pp. 5, 6]. For Stern, these contrasting models of the present were far from new, however, and he found both expressed in ancient Greek thought:

Chronos is the objective view of time …. In the world of chronos, the present instant is a moving point in time headed only toward the future. . . . It is an almost infinitesimally thin slice of time during which very little could take place without immediately becoming the past. Effectively, there is no present.

The problem with chronos is that if there is no now long enough that something can unfold in it, there can be no direct experience. That is not intuitively acceptable. Also, life-as-lived is not experienced as an inexorably continuous flow. Rather, it is felt to be discontinuous, made of incidents and events separated in time

The Greeks’ subjective conception of time, kairos, may be of use here. Kairos is the passing moment in which something happens. . . . It is the coming into being of a new state of things, and it happens in a moment of awareness. . . . It is a small window of becoming and opportunity [[

13], p.7].

Stern explained that the findings of modern psychology are consistent with an experienced present of ‘three to four seconds.’ He suggested that there are three main reasons for this: ‘it is the time needed to make meaningful groupings of perceptual stimuli…, to compose functional units of our behavioral performances, and to permit consciousness to arise’[[

13], p. 41].

2. Lost in Fascination

These two seemingly contradictory attitudes to duration, as an essentially discomforting experience, and as something we require in order to sense the moment, can actually be reconciled if the observer’s viewpoint is taken into account. To someone engrossed in something, several seconds may well simply feel like ‘now,’ but to a person observing them same period would have a clearly perceptible duration. Henry David Thoreau left us a memorable account of the experience of being lost in an extended present:

There were times when I could not afford to sacrifice the bloom of the present moment to any work, whether of the head or hand. Sometimes, in a summer morning, having taken my accustomed bath, I sat in my sunny doorway from sunrise till noon, rapt in a revelry, amidst the pines and hickories and sumacs, in undiluted solitude and stillness, while the birds sang around or flitted noiseless through the house, until by the sun falling in at my west window, or the noise of some traveler’s wagon on the distant highway, I was reminded of the lapse of time. I grew in those seasons like corn in the night and they were far better than any work of the hands would have been. They were not time subtracted from my life, but so much over and above my usual allowance. I realized what the Orientals mean by contemplation and the forsaking of works [

14].

While Thoreau was transfixed, the scene around him was far from it. It would have been full of perceptible change, including the movements and sounds of birds and insects, the swaying of tree branches and the rustling of leaves. These natural phenomena were so familiar, however, that they were stimulating without demanding any deliberate attention on Thoreau’s part. Psychologists Rachel and Stephen Kaplan have since described this affect as ‘soft fascination,’ and in their Attention Restoration Theory they argue aids in replenishing our capacity for concentration [

15].

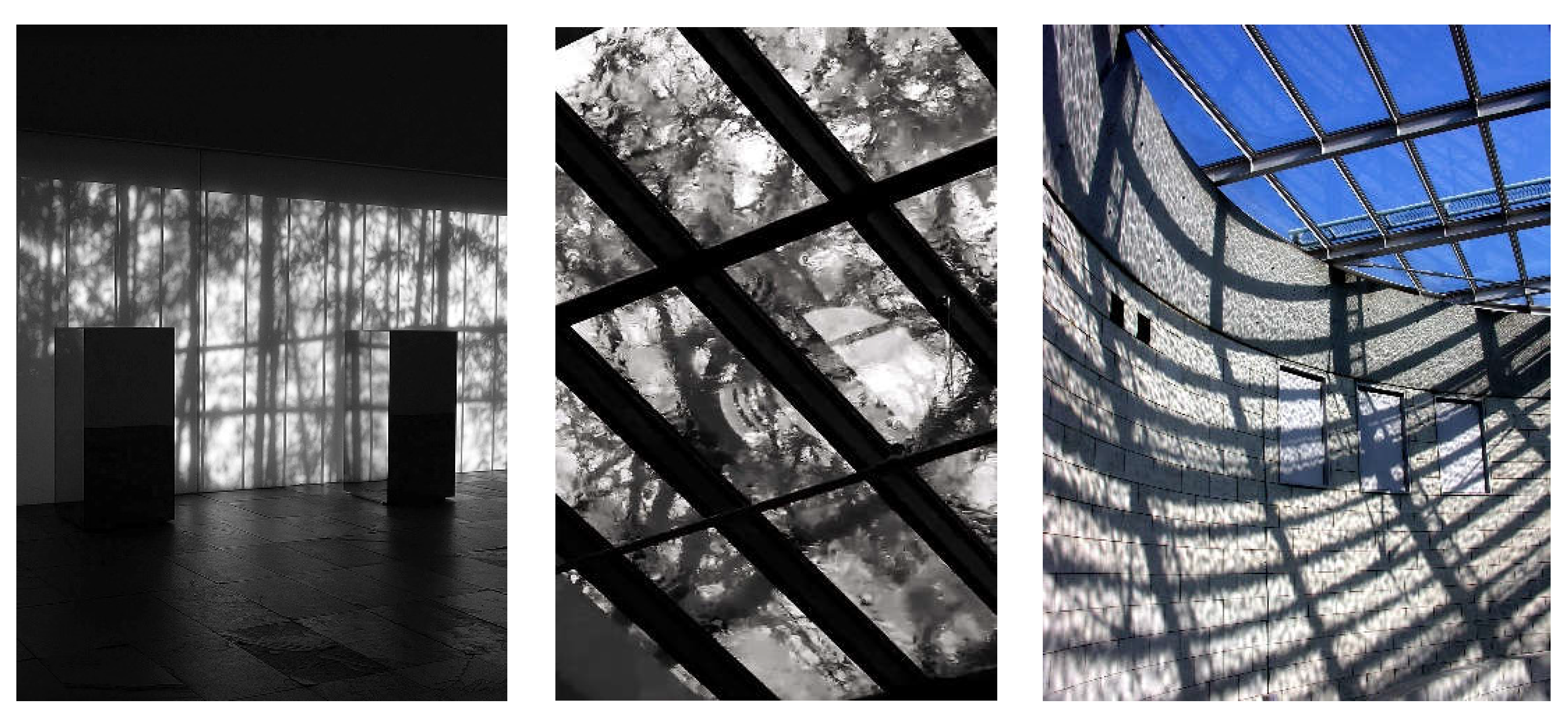

Including natural change in the indoor spaces where we now spend most of our lives would seem, then, to be a potentially valuable means of helping to sustain the attention of building occupants without distracting them from other activities. The book

Naturally Animated Architecture makes the case for doing just that, arguing that that weather-generated movement is a freely available source of natural indoor change that can help to reduce stress and sustain alertness by keeping us in the present (

Figure 1–3) [

16].

3. The House of the Perpetual Now

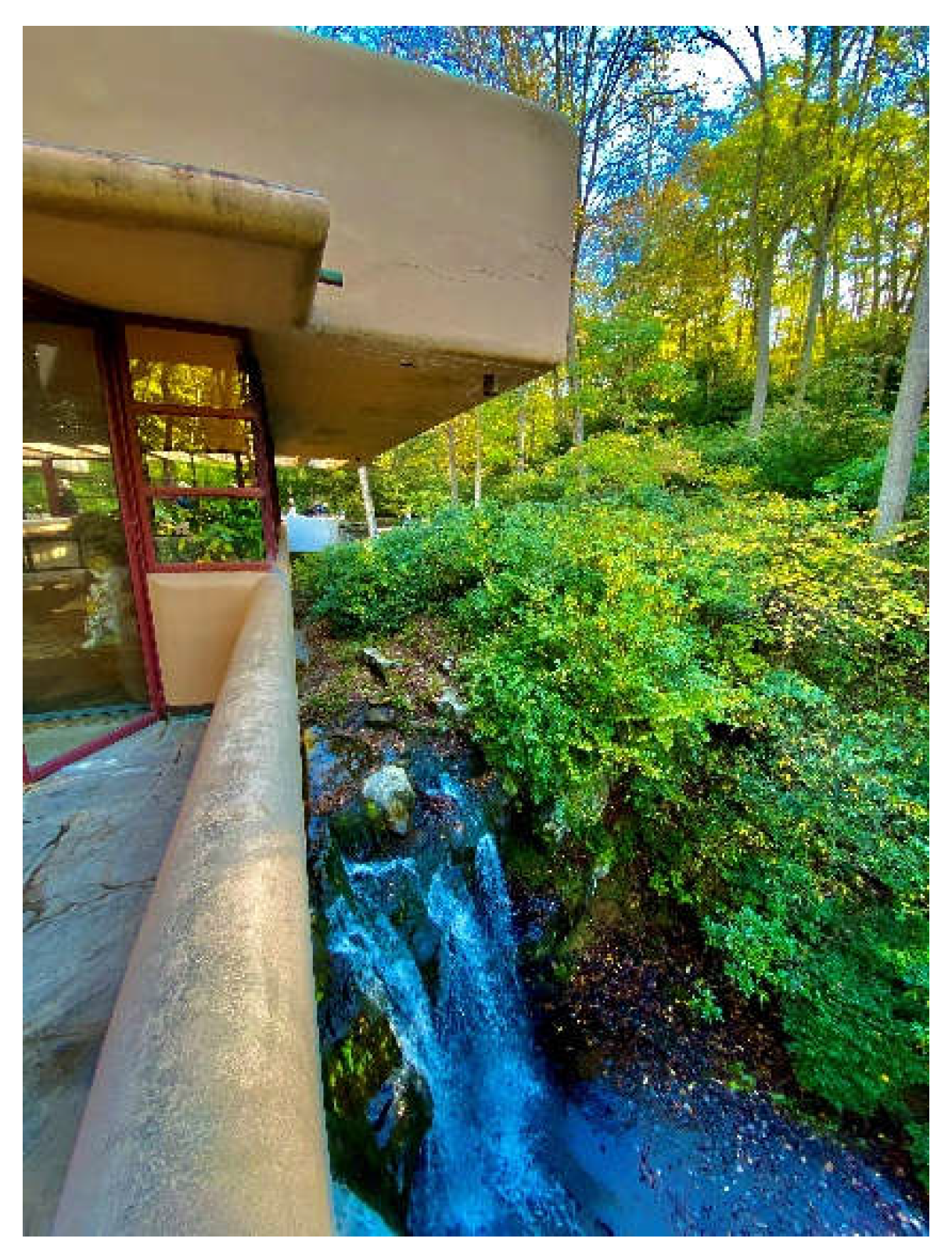

We may move through space, but it has often been suggested that time moves through us. The latter is certainly true of what is arguably the world’s most famous modern house, Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic Fallingwater. The temporal qualities of the Kaufmann residence in rural Western Pennsylvania have been described by several authors [

17,

18]. The house evokes powerful recollections of the past and anticipations of the future [

19], but it also manifests characteristics that are seemingly beyond time.

The passing moment is most obviously manifested in the presence of the waterfall immediately below the house. The terrace overhanging the falls spans a small part of the past in the form of water that has already gone over the falls, and of the future, in the water that is about to do so. In this it effectively manifests Husserl’s description of the present as the sensing of what is happening now combined with the recollection of what has just happened (retention), and the anticipation of what is about to happen (protention) [

20] (

Figure 4).

The lip of the rock ledge over which the stream falls sharply divides the future from the past. Water that at one moment was still on its way to the falls in the next instant has passed over it. The falling of the water, then, is such a brief moment that it can hardly be perceived, yet the experience of watching the falls is far from the theoretically ‘punctual present’ of science. On the contrary, because the falling of the water is continuous, it seems to stand still, drawing us into an extended now that makes us temporarily unaware of passing time.

4. Timeless Forms

Before people began using written records, they shared oral descriptions as a means of passing on important knowledge [

21,

22]. Historian Mircea Eliade points out the ‘ahistorical’ nature of this kind of shared memory and its ‘inability to retain historical events and individuals except as it transforms them into archetypes’ [

23]. Carl Jung famously described these shared models as the basis of a common human unconscious that transcends time and culture:

This collective unconscious does not develop individually but is inherited. It consists of pre-existent forms, the archetypes.

[instincts] form very close analogies to the archetypes, so close, in fact, that there is good reason for supposing that the archetypes are the unconscious images of the instincts themselves, in other words, that they are patterns of instinctual behaviour [

24].

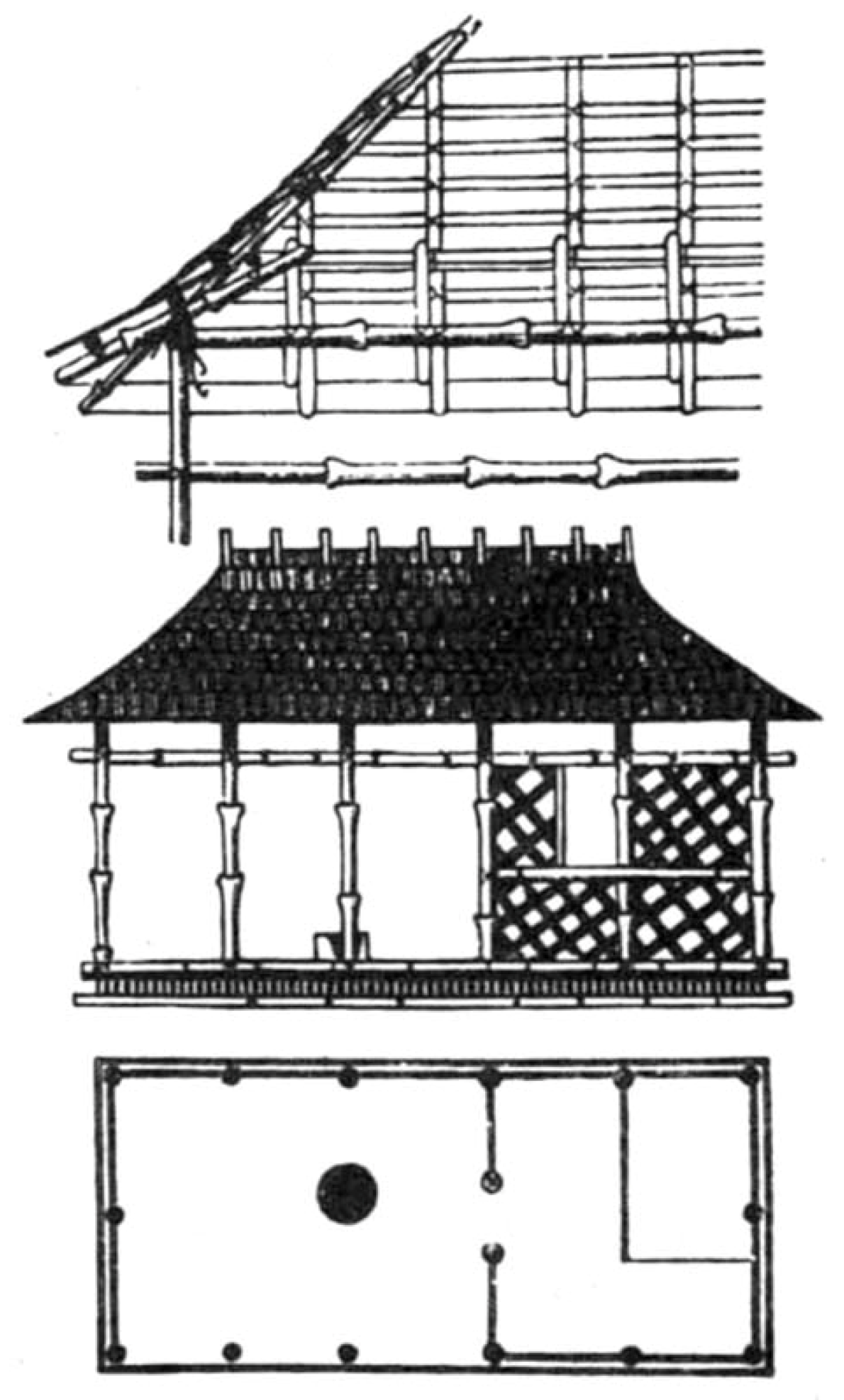

These established types included ideal environments for people to live, which both accommodated and reinforced preferred human behaviors. Those patterns of being are constantly being remanifested in slightly modified forms, but their essence effectively transcends the passage of time. Like Jung’s archetypal characters, then, the earth mother, the wise old man and the hero etc., Gottfried Semper’s architectural archetypes—the hearth, platform, canopy, and screen, for example, are similarly time

less [

25] (

Figure 5).

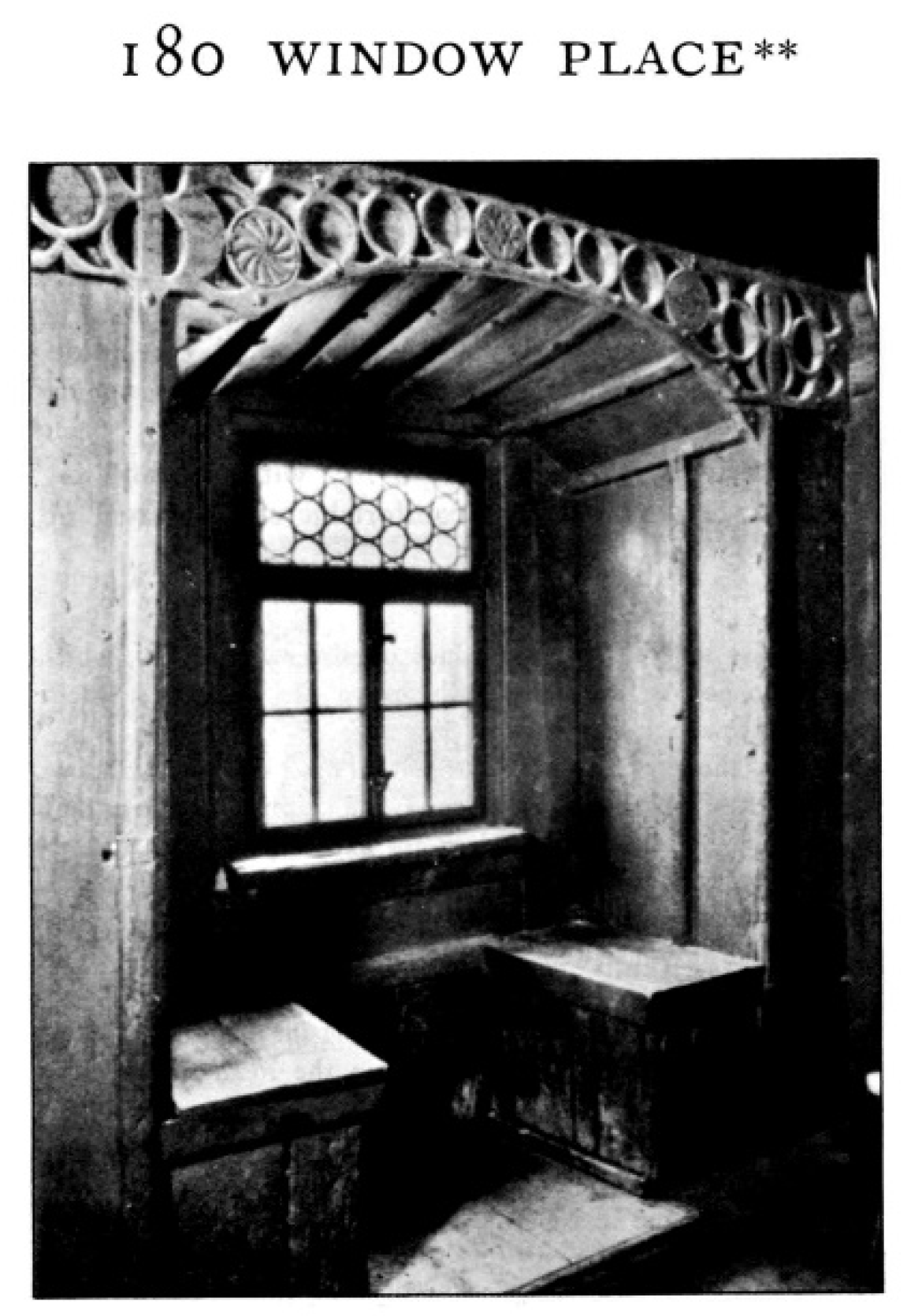

The title of Christopher Alexander’s book

The Timeless Way of Building (1979) referred to the process by which buildings were created before there were any professional architects [

26]. The implication of the book was that the spatial configurations he had presented previously in

A Pattern Language (1977) accommodated patterns of human behavior that transcended time [

27] (

Figure 6).

5. Space without Time

Eliade argued that such archetypal forms return us, not to the past, but rather to an eternal present [[

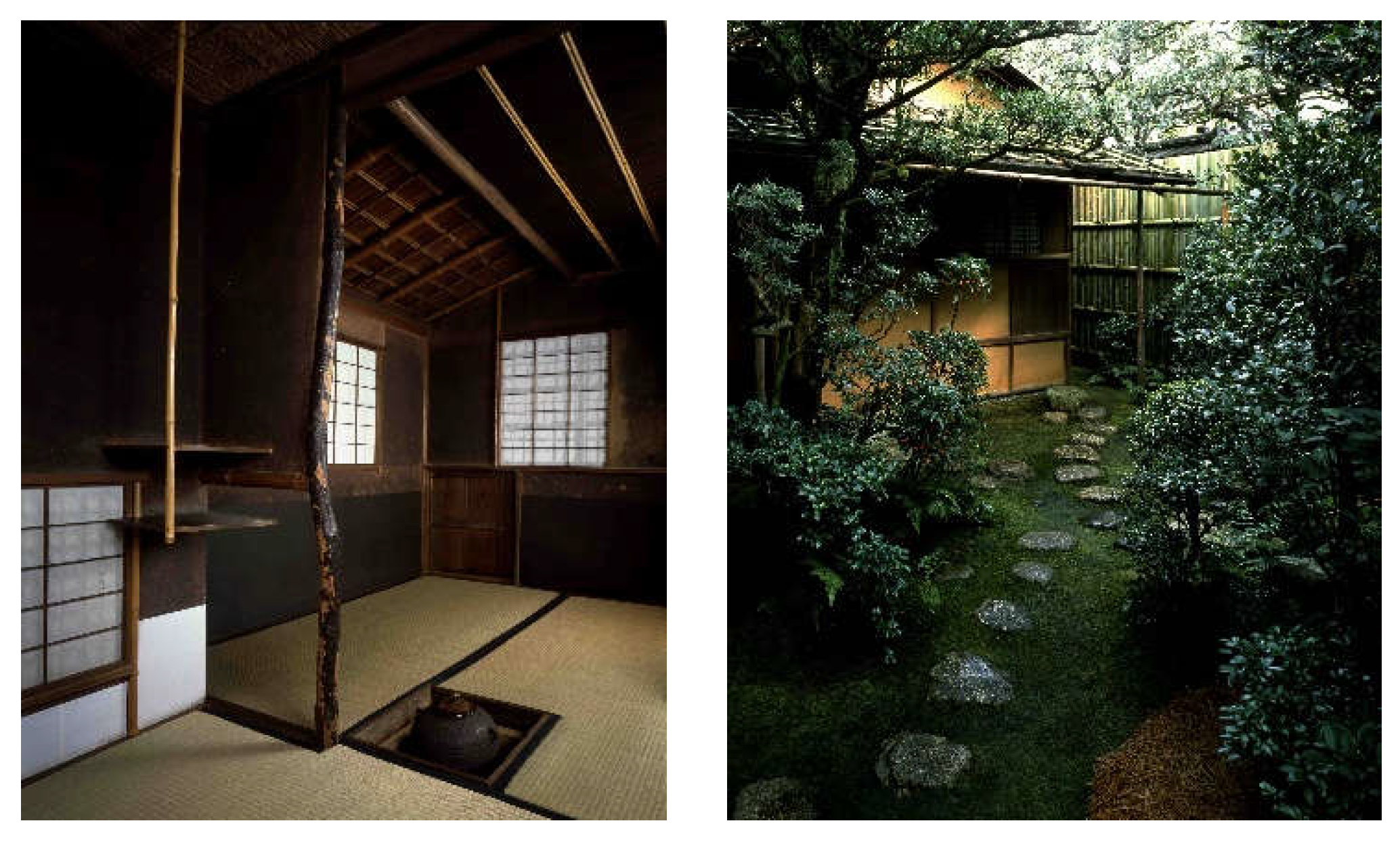

23], pp. 85, 86] For him, this was especially true of rituals. The Japanese tea ceremony is a perfect case in point. The

wabi form of Japanese tearoom was a Zen-inspired appreciation of the transience of being that developed during the fifteenth century largely in response to the precariousness of life during the nation’s Warring States Period. Its intent was summed up in the famous Zen saying

ichi go ichi e (一期一会), which can be roughly translated as ‘on this one occasion.’

In keeping with this philosophy, the tea ritual was intended to focus attention on the uniqueness of the here and now. To this day for example, measures of time such as watches or phones are excluded from the tearoom on the grounds that awareness of regular time is antithetical to the central goal of the tea ritual of celebrating the present.

In the case of the tearoom, as distinct from the ceremony it housed, this objective was achieved primarily through spatial isolation. The path to the room, for example, was deliberately convoluted in order to increase the psychological distance one had traveled from everyday life, and the room itself was cut off from the outside world and devoid of anything unrelated to the here and now. Its interior, then, was the equivalent of a break in the continuity of time, and the ritual was effectively an expanded ‘now’ that could last several hours (

Figure 10, 11).