Submitted:

12 August 2024

Posted:

12 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Analyses

3. Results

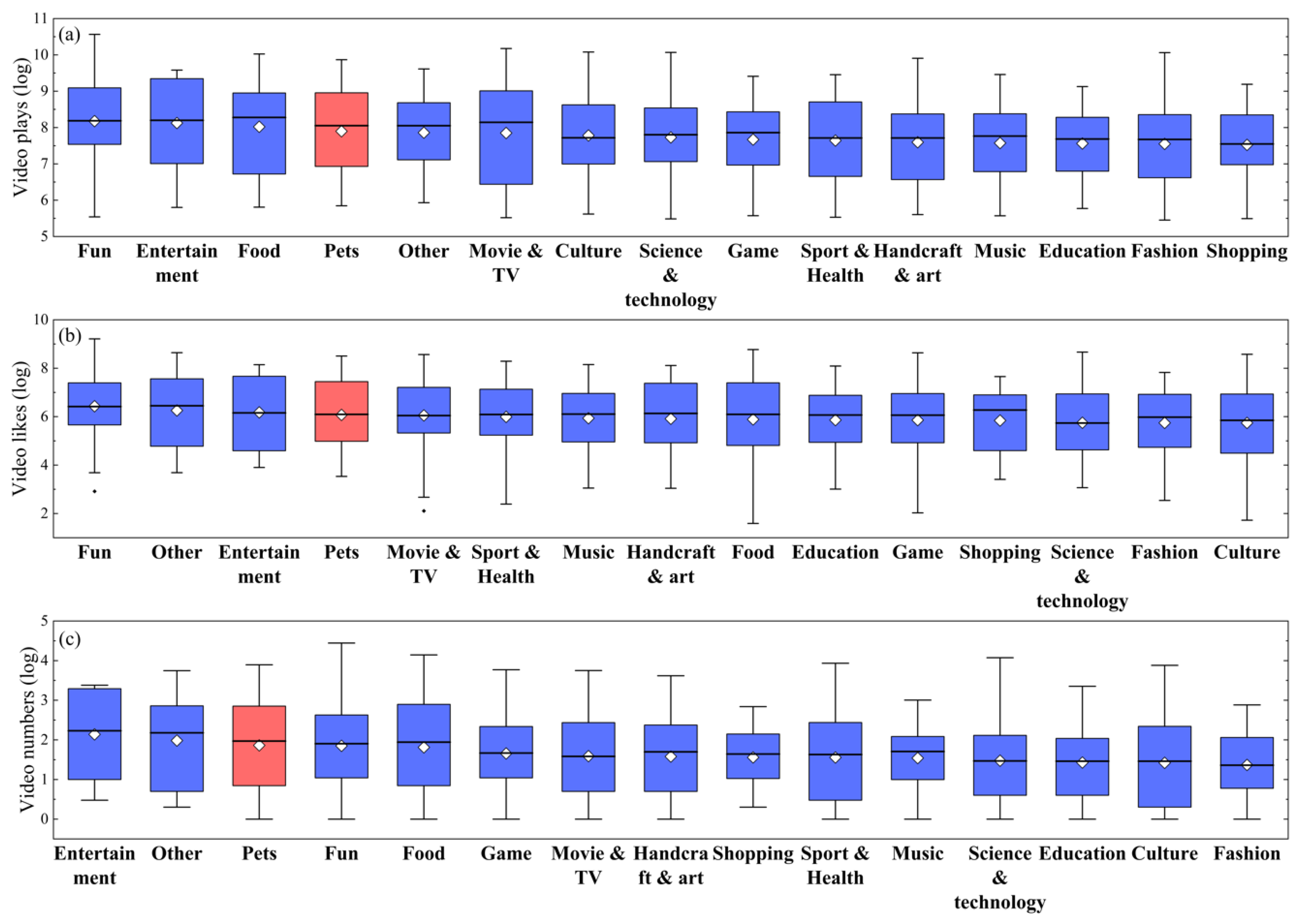

3.1. The Current Situation of Human Preferences for Dogs and Cats

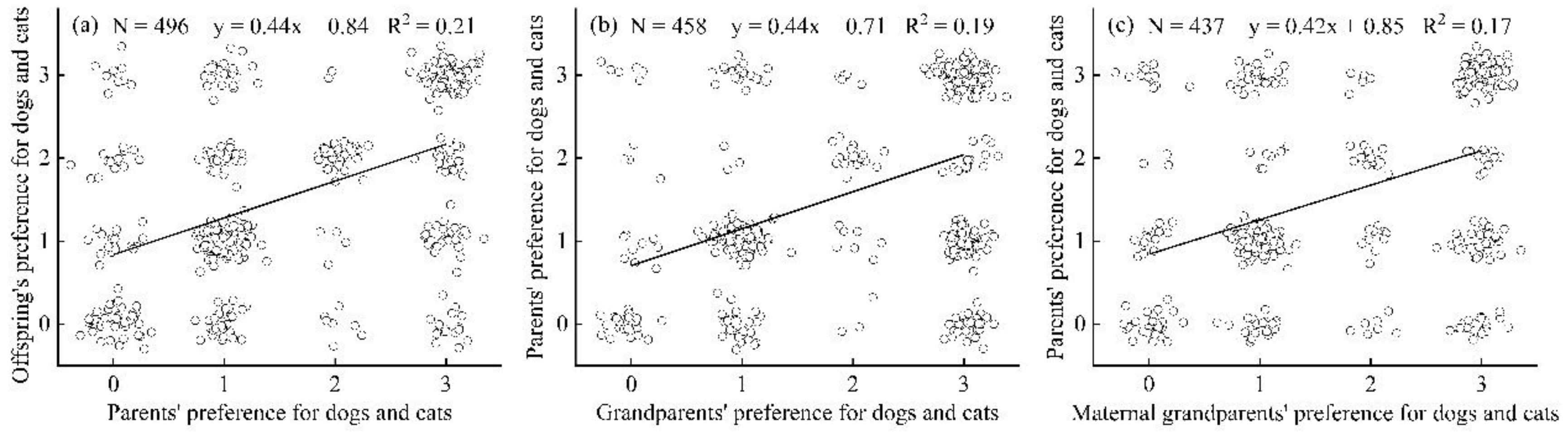

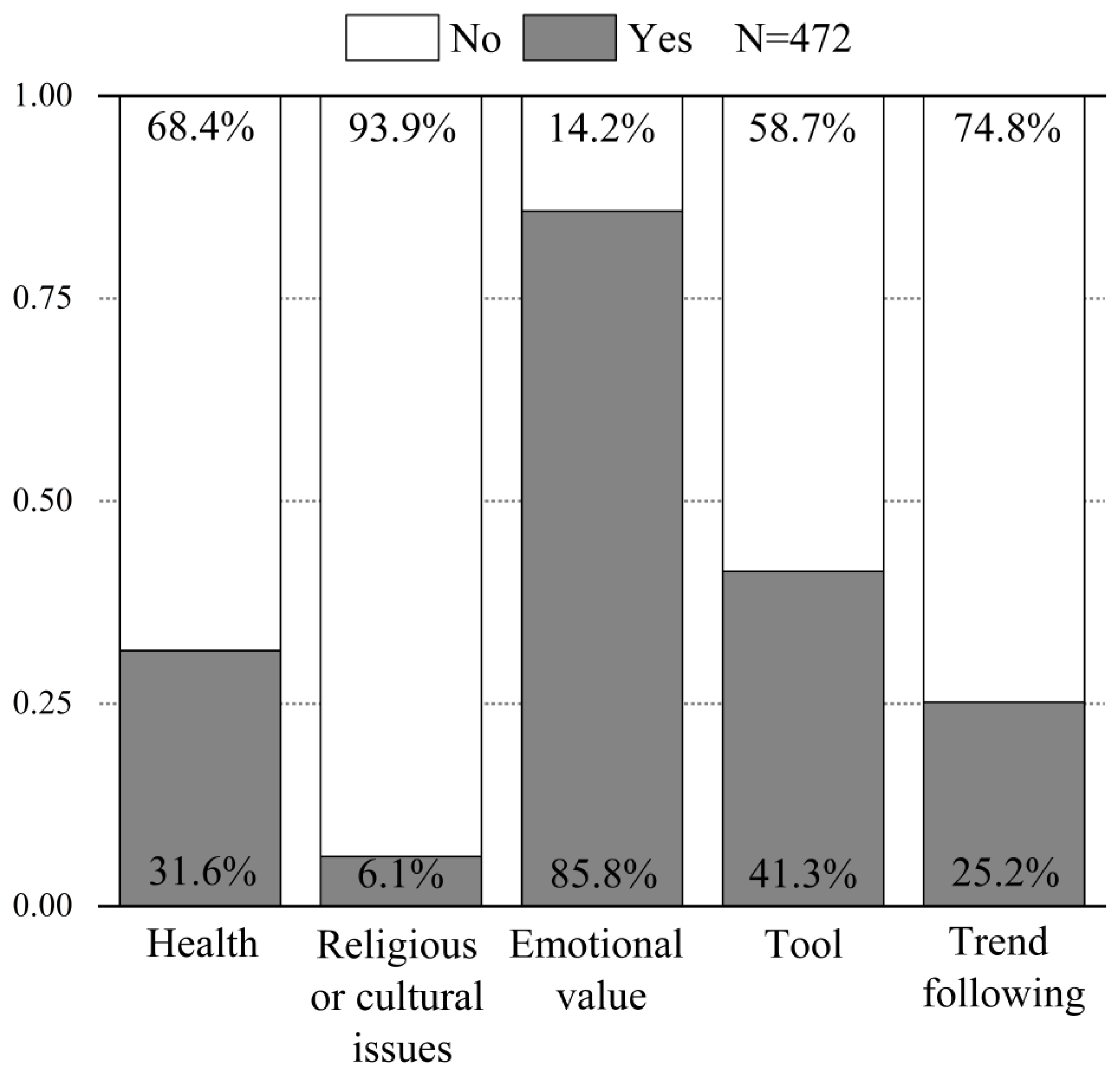

3.2. Heritability and Causes of Dog and Cat Ownership

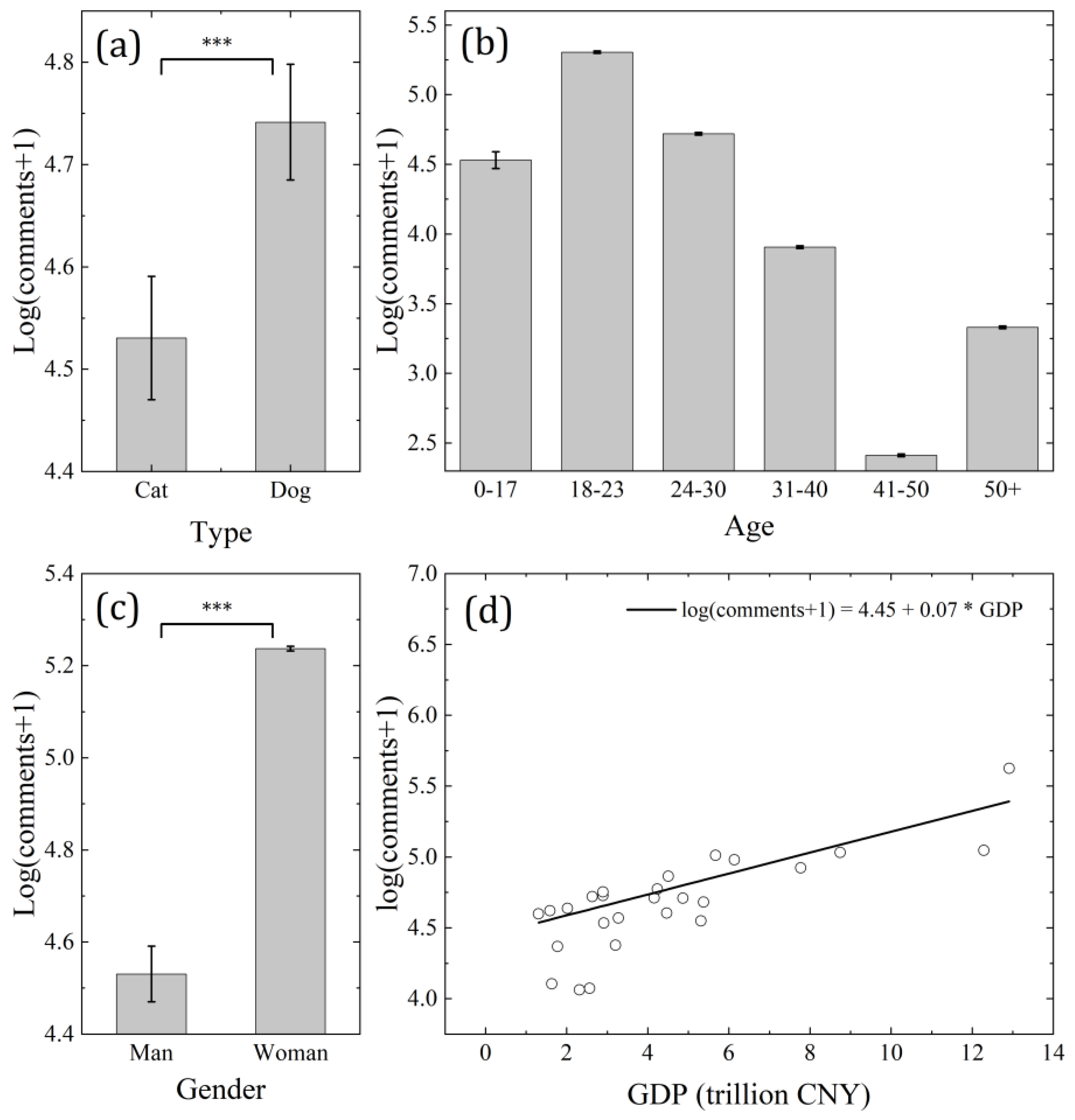

3.3. Factors That Influence the Preferences for Dogs and Cats

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Driscoll, C.A.; Macdonald, D.W.; O’Brien, S.J. From Wild Animals to Domestic Pets, an Evolutionary View of Domestication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009, 106, 9971–9978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blouin, D.D. Understanding Relations between People and Their Pets. Sociology Compass 2012, 6, 856–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, L.A. Dogs as Human Companions: A Review of the Relationship. The domestic dog: Its evolution, behaviour and interactions with people 1995, 161–178.

- Wang, G.; Zhai, W.; Yang, H.; Fan, R.; Cao, X.; Zhong, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, F.; Wu, H.; Cheng, L.; et al. The Genomics of Selection in Dogs and the Parallel Evolution between Dogs and Humans. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergström, A.; Frantz, L.; Schmidt, R.; Ersmark, E.; Lebrasseur, O.; Girdland-Flink, L.; Lin, A.T.; Storå, J.; Sjögren, K.-G.; Anthony, D.; et al. Origins and Genetic Legacy of Prehistoric Dogs. Science 2020, 370, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, J.-F.; Kluetsch, C.; Zou, X.-J.; Zhang, A. -b.; Luo, L.-Y.; Angleby, H.; Ardalan, A.; Ekstrom, C.; Skollermo, A.; Lundeberg, J.; et al. mtDNA Data Indicate a Single Origin for Dogs South of Yangtze River, Less Than 16,300 Years Ago, from Numerous Wolves. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2009, 26, 2849–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour, and Interactions with People; Serpell, J., Ed.; 1. publ.; Cambridge Univ. Press: Cambridge, 1995; ISBN 978-0-521-42537-7.

- Larson, G.; Karlsson, E.K.; Perri, A.; Webster, M.T.; Ho, S.Y.W.; Peters, J.; Stahl, P.W.; Piper, P.J.; Lingaas, F.; Fredholm, M.; et al. Rethinking Dog Domestication by Integrating Genetics, Archeology, and Biogeography. PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 2012, 109, 8878–8883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frantz, L.A.F.; Mullin, V.E.; Pionnier-Capitan, M.; Lebrasseur, O.; Ollivier, M.; Perri, A.; Linderholm, A.; Mattiangeli, V.; Teasdale, M.D.; Dimopoulos, E.A.; et al. Genomic and Archaeological Evidence Suggest a Dual Origin of Domestic Dogs. Science 2016, 352, 1228–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Z.-L.; Oskarsson, M.; Ardalan, A.; Angleby, H.; Dahlgren, L.-G.; Tepeli, C.; Kirkness, E.; Savolainen, P.; Zhang, Y.-P. Origins of Domestic Dog in Southern East Asia Is Supported by Analysis of Y-Chromosome DNA. Heredity 2012, 108, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driscoll, C.A.; Menotti-Raymond, M.; Roca, A.L.; Hupe, K.; Johnson, W.E.; Geffen, E.; Harley, E.H.; Delibes, M.; Pontier, D.; Kitchener, A.C.; et al. The Near Eastern Origin of Cat Domestication. Science 2007, 317, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons, L. Cat Domestication and Breed Development. In Proceedings of the 10th World Congress on Genetics Applied to Livestock Production. Canada; 2014.

- Archer, J. Why Do People Love Their Pets? Evolution and Human behavior 1997, 18, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bir, C.; Ortez, M.; Olynk Widmar, N.J.; Wolf, C.A.; Hansen, C.; Ouedraogo, F.B. Familiarity and Use of Veterinary Services by US Resident Dog and Cat Owners. Animals 2020, 10, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalenkoski, C.M.; Korankye, T. Enriching Lives: How Spending Time with Pets Is Related to the Experiential Well-Being of Older Americans. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2022, 17, 489–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodsworth, W.; Coleman, G.J. Child–Companion Animal Attachment Bonds in Single and Two-Parent Families. Anthrozoös 2001, 14, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, N. ‘Animals Just Love You as You Are’: Experiencing Kinship across the Species Barrier. Sociology 2014, 48, 715–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouma, E.M.C.; Reijgwart, M.L.; Dijkstra, A. Family Member, Best Friend, Child or ‘Just’ a Pet, Owners’ Relationship Perceptions and Consequences for Their Cats. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 19, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, F. Human-Animal Bonds I: The Relational Significance of Companion Animals. Fam. Process 2009, 48, 462–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans-Wilday, A.S.; Hall, S.S.; Hogue, T.E.; Mills, D.S. Self-Disclosure with Dogs: Dog Owners’ and Non-Dog Owners’ Willingness to Disclose Emotional Topics. Anthrozoös 2018, 31, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenebaum, J. It’s a Dog’s Life: Elevating Status from Pet to “Fur Baby” at Yappy Hour. Soc. Anim. 2004, 12, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritvo, H. Pride and Pedigree: The Evolution of the Victorian Dog Fancy. Victorian Stud. 1986, 29, 227–253. [Google Scholar]

- Linseele, V.; Van Neer, W.; Hendrickx, S. Evidence for Early Cat Taming in Egypt. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2007, 34, 2081–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auster, C.J.; Auster-Gussman, L.J.; Carlson, E.C. Lancaster Pet Cemetery Memorial Plaques 1951–2018: An Analysis of Inscriptions. Anthrozoös 2020, 33, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, E.; Gee, N.R.; Simonsick, E.M.; Barr, E.; Resnick, B.; Werthman, E.; Adesanya, I. Pet Ownership and Maintenance of Physical Function in Older Adults—Evidence from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA). Innovation in Aging 2023, 7, igac080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogata, N.; Weng, H.-Y.; L. McV. Messam, L. Temporal Patterns of Owner-Pet Relationship, Stress, and Loneliness during the COVID-19 Pandemic, and the Effect of Pet Ownership on Mental Health: A Longitudinal Survey. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0284101.

- Krause-Parello, C.A.; Gulick, E.E.; Basin, B. Loneliness, Depression, and Physical Activity in Older Adults: The Therapeutic Role of Human–Animal Interactions. Anthrozoös 2019, 32, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mičková, E.; Machová, K.; Daďová, K.; Svobodová, I. Does Dog Ownership Affect Physical Activity, Sleep, and Self-Reported Health in Older Adults? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, K.; Blascovich, J.; Mendes, W.B. Cardiovascular Reactivity and the Presence of Pets, Friends, and Spouses: The Truth about Cats and Dogs. Psychosomatic medicine 2002, 64, 727–739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Friedmann, E.; Thomas, S.A. Pet Ownership, Social Support, and One-Year Survival after Acute Myocardial Infarction in the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST). The American journal of cardiology 1995, 76, 1213–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fall, T.; Kuja-Halkola, R.; Dobney, K.; Westgarth, C.; Magnusson, P.K. Evidence of Large Genetic Influences on Dog Ownership in the Swedish Twin Registry Has Implications for Understanding Domestication and Health Associations. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 7554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.E.; Govind, T.; Ramsey, M.; Wu, T.C.; Daly, R.; Liu, J.; Tu, X.M.; Paulus, M.P.; Thomas, M.L.; Jeste, D.V. Compassion toward Others and Self-Compassion Predict Mental and Physical Well-Being: A 5-Year Longitudinal Study of 1090 Community-Dwelling Adults across the Lifespan. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prato-Previde, E.; Fallani, G.; Valsecchi, P. Gender Differences in Owners Interacting with Pet Dogs: An Observational Study. Ethology 2006, 112, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beadle, J.N.; de la Vega, C.E. Impact of Aging on Empathy: Review of Psychological and Neural Mechanisms. Frontiers in psychiatry 2019, 10, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, M.; McDonald, S.; Wallis, K. Empathy across the Ages:“I May Be Older but I’m Still Feeling It”. Neuropsychology 2022, 36, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using Lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2022.

- Downes, M.; Canty, M.J.; More, S.J. Demography of the Pet Dog and Cat Population on the Island of Ireland and Human Factors Influencing Pet Ownership. Prev. Vet. Med. 2009, 92, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toribio, J.-A.L.M.; Norris, J.M.; White, J.D.; Dhand, N.K.; Hamilton, S.A.; Malik, R. Demographics and Husbandry of Pet Cats Living in Sydney, Australia: Results of Cross-Sectional Survey of Pet Ownership. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2009, 11, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, J.K.; Browne, W.J.; Roberts, M.A.; Whitmarsh, A.; Gruffydd-Jones, T.J. Number and Ownership Profiles of Cats and Dogs in the UK. Vet. Rec. 2010, 166, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.K.; Gruffydd-Jones, T.J.; Roberts, M.A.; Browne, W.J. Assessing Changes in the UK Pet Cat and Dog Populations: Numbers and Household Ownership. Vet. Rec. 2015, 177, 259–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Applebaum, J.W.; Peek, C.W.; Zsembik, B.A. Examining U.S. Pet Ownership Using the General Social Survey. Soc. Sci. J. 2023, 60, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasloff, R.L. Measuring Attachment to Companion Animals: A Dog Is Not a Cat Is Not a Bird. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1996, 47, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, M.; Massavelli, B.; Pachana, N. Using Attachment Theory and Social Support Theory to Examine and Measure Pets as Sources of Social Support and Attachment Figures. Anthrozoös 2017, 30, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, K.C.; Hoffman, C.L.; Vasilopoulos, T.; Kremen, W.S.; Panizzon, M.S.; Grant, M.D.; Lyons, M.J.; Xian, H.; Franz, C.E. Genetic and Environmental Influences on Individual Differences in Frequency of Play with Pets among Middle-Aged Men: A Behavioral Genetic Analysis. Anthrozoös 2012, 25, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, K.; Virányi, Z.; Kis, A.; Turcsán, B.; Hudecz, Á.; Marmota, M.T.; Koller, D.; Rónai, Z.; Gácsi, M.; Topál, J. Dog-Owner Attachment Is Associated With Oxytocin Receptor Gene Polymorphisms in Both Parties. A Comparative Study on Austrian and Hungarian Border Collies. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McConnell, A.R.; Brown, C.M.; Shoda, T.M.; Stayton, L.E.; Martin, C.E. Friends with Benefits: On the Positive Consequences of Pet Ownership. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 101, 1239–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, R.; Lagerkvist, C.J.; Hagberg Gustavsson, M.; Holst, B.S. An Empirical Examination of the Conceptualization of Companion Animals. BMC Psychology 2018, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, E.E.; Otto, C.M.; Udell, M.A.; Hall, N.J.; Johnston, A.M.; MacLean, E.L. Enhancing the Selection and Performance of Working Dogs. Frontiers in veterinary science 2021, 8, 644431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobb, M.L.; Otto, C.M.; Fine, A.H. The Animal Welfare Science of Working Dogs: Current Perspectives on Recent Advances and Future Directions. Frontiers in veterinary science 2021, 8, 666898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, N.J.; Johnston, A.M.; Bray, E.E.; Otto, C.M.; MacLean, E.L.; Udell, M.A. Working Dog Training for the Twenty-First Century. Frontiers in veterinary science 2021, 8, 646022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupo, K.D. When and Where Do Dogs Improve Hunting Productivity? The Empirical Record and Some Implications for Early Upper Paleolithic Prey Acquisition. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2017, 47, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guagnin, M.; Perri, A.R.; Petraglia, M.D. Pre-Neolithic Evidence for Dog-Assisted Hunting Strategies in Arabia. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2018, 49, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Weyde, L.K.; Kokole, M.; Modise, C.; Mbinda, B.; Seele, P.; Klein, R. Reducing Livestock-Carnivore Conflict on Rural Farms Using Local Livestock Guarding Dogs. Journal of Vertebrate Biology 2020, 69, 20090–20091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marker, L.; Pfeiffer, L.; Siyaya, A.; Seitz, P.; Nikanor, G.; Fry, B.; O’flaherty, C.; Verschueren, S. Twenty-Five Years of Livestock Guarding Dog Use across Namibian Farmlands. Journal of Vertebrate Biology 2021, 69, 20115–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Cobos, L.; Winterhalder, B. Ethnographic Observations on the Role of Domestic Dogs in the Lowland Tropics of Belize with Emphasis on Crop Protection and Subsistence Hunting. Hum. Ecol. 2021, 49, 779–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, S.L.; Cecchetti, M.; McDonald, R.A. Our Wild Companions: Domestic Cats in the Anthropocene. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2020, 35, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecchetti, M.; Crowley, S.L.; McDonald, R.A. Drivers and Facilitators of Hunting Behaviour in Domestic Cats and Options for Management. Mammal Rev. 2021, 51, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udell, M.A.R.; Dorey, N.R.; Wynne, C.D.L. What Did Domestication Do to Dogs? A New Account of Dogs’ Sensitivity to Human Actions. Biol. Rev. 2010, 85, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, T.; Marston, L.C.; Bennett, P.C. Breeding Dogs for Beauty and Behaviour: Why Scientists Need to Do More to Develop Valid and Reliable Behaviour Assessments for Dogs Kept as Companions. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012, 137, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, G.; Huang, Y.; Robinson, K.; Wilson, M.S.; Bulbulia, J.; Sibley, C.G. New Zealand Pet Owners’ Demographic Characteristics, Personality, and Health and Wellbeing: More Than Just a Fluff Piece. Anthrozoös 2020, 33, 561–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschenhauser, K.; Meichel, Y.; Schmalzer, S.; Beetz, A.M. Children Love Their Pets: Do Relationships between Children and Pets Co-Vary with Taxonomic Order, Gender, and Age? Anthrozoös 2017, 30, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, P.; Hansart, C.; Su, B. Attitudes of Young Adults toward Animals—the Case of High School Students in Belgium and The Netherlands. Animals 2019, 9, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-A.; Kenyon, C.J.; Cheong, S.; Lee, J.; Hart, L.A. Attitudes and Practices toward Feral Cats of Male and Female Dog or Cat Owners and Non-Owners in Seoul, South Korea. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2023, 10, 1230067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.-H.; Min, K.-D.; Cho, S.; Cho, S. The Relationship between Dog-Related Factors and Owners’ Attitudes toward Pets: An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Study in Korea. Frontiers in veterinary science 2020, 7, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bick, A.; Fuchs-Schündeln, N.; Lagakos, D. How Do Hours Worked Vary with Income? Cross-Country Evidence and Implications. Amer. Econ. Rev. 2018, 108, 170–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, R.M.A.; Murphy, D.; Farnworth, M.J. Purchasing Popular Purebreds: Investigating the Influence of Breed-Type on the Pre-Purchase Motivations and Behaviour of Dog Owners. Animal welfare 2017, 26, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, K.E. Acquiring a Pet Dog: A Review of Factors Affecting the Decision-Making of Prospective Dog Owners. Animals 2019, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, E.; Miller, K.; Mohan-Gibbons, H.; Vela, C. Why Did You Choose This Pet?: Adopters and Pet Selection Preferences in Five Animal Shelters in the United States. Animals 2012, 2, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hecht, J.; Horowitz, A. Seeing Dogs: Human Preferences for Dog Physical Attributes. Anthrozoös 2015, 28, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, B.M.; Peirce, K.; Caeiro, C.C.; Scheider, L.; Burrows, A.M.; McCune, S.; Kaminski, J. Paedomorphic Facial Expressions Give Dogs a Selective Advantage. PLoS one 2013, 8, e82686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, W.P.; Davidson, J.P.; Zuefle, M.E. Effects of Phenotypic Characteristics on the Length of Stay of Dogs at Two No Kill Animal Shelters. J. Appl. Anim. Welfare Sci. 2013, 16, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, T.; Marston, L.C.; Bennett, P.C. Describing the Ideal Australian Companion Dog. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 120, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diverio, S.; Boccini, B.; Menchetti, L.; Bennett, P.C. The Italian Perception of the Ideal Companion Dog. Journal of Veterinary Behavior 2016, 12, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protopopova, A.; Wynne, C.D.L. Adopter-Dog Interactions at the Shelter: Behavioral and Contextual Predictors of Adoption. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 157, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, R.; Allan, G.; Howlett, C.; Thompson, D.; James, G.; McWHIRTER, C.; Kendall, K. Osteochondrodysplasia in Scottish Fold Cats. Aust. Vet. J. 1999, 77, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, D.G.; Packer, R.M.A.; Francis, P.; Church, D.B.; Brodbelt, D.C.; Pegram, C. French Bulldogs Differ to Other Dogs in the UK in Propensity for Many Common Disorders: A VetCompass Study. Canine Medicine and Genetics 2021, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Effects | Estimates ± SE | t value | P value |

| Random effects | |||

| Video ID (N = 1006) | 0.794 | ||

| Region (N = 26) | 0.015 | ||

| Residual | 0.798 | ||

| Fixed effects | |||

| Intercept | 4.527 ± 0.061 | ||

| Woman | 0.707 ± 0.005 | 137.4 | <0.001 |

| Dog | 0.211 ± 0.057 | 3.7 | <0.001 |

| GDP | 0.063 ± 0.008 | 7.6 | <0.001 |

| Age 18-23 | 0.775 ± 0.009 | 87.0 | <0.001 |

| Age 24-30 | 0.189 ± 0.009 | 21.2 | <0.001 |

| Age 31-40 | -0.625 ± 0.009 | -70.1 | <0.001 |

| Age 41-50 | -2.119 ± 0.009 | -237.8 | <0.001 |

| Age 50+ | -1.200 ± 0.009 | -134.7 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).