Submitted:

10 August 2024

Posted:

12 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

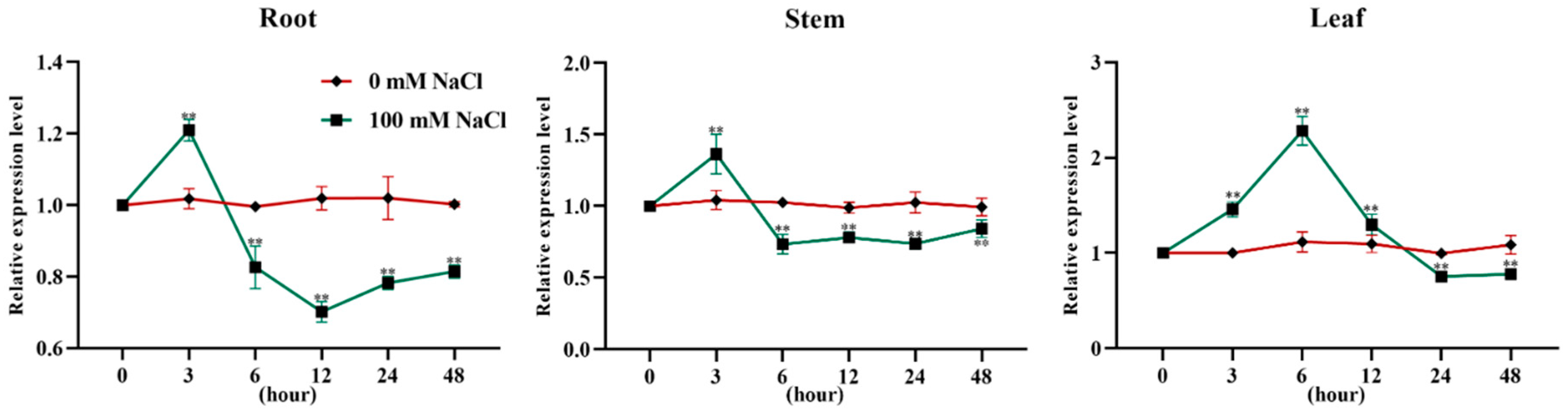

2.1. Expression of PtEXPA6 in Root and Shoot of Populus trichocarpa

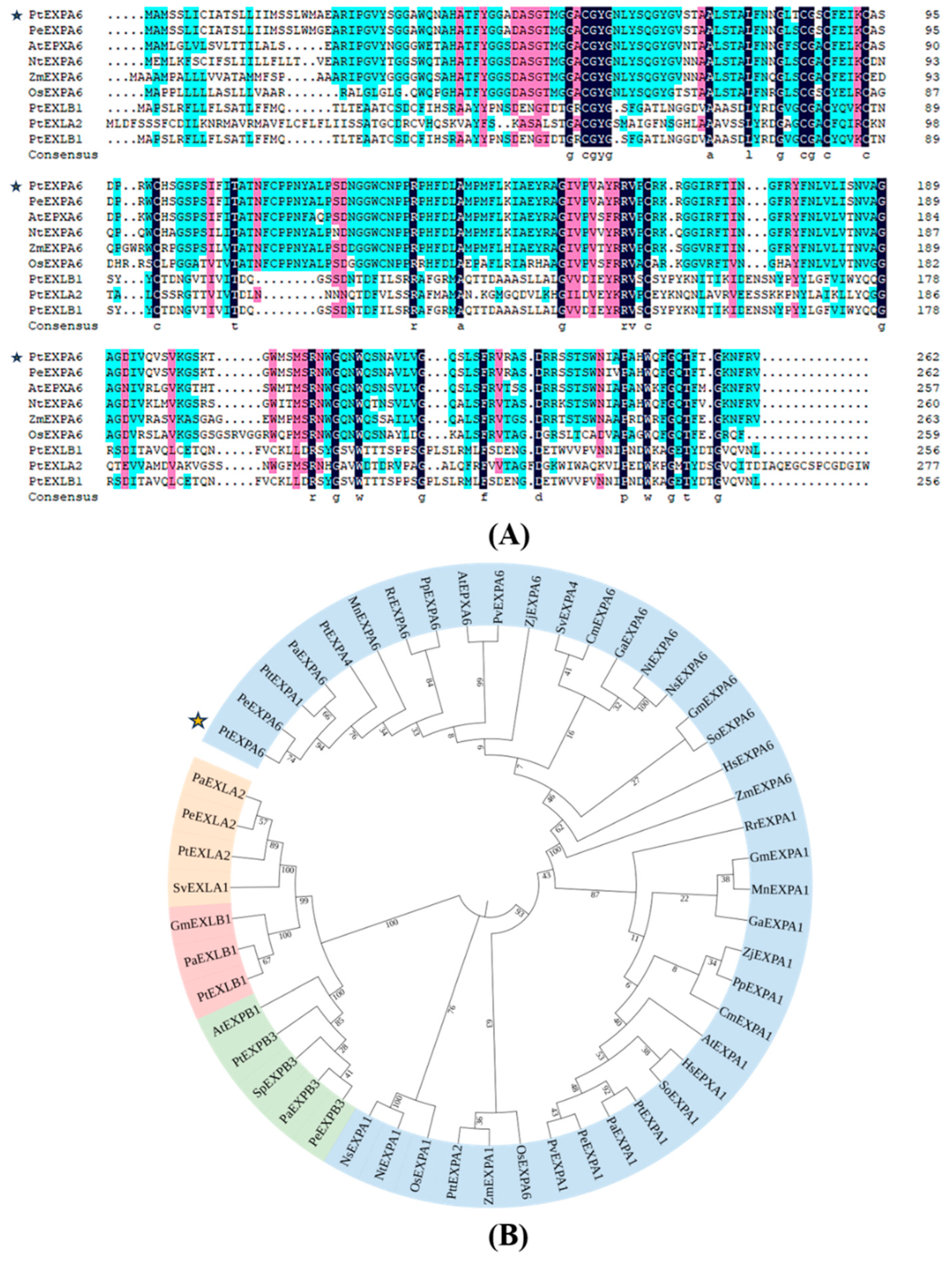

2.2. Homologous Sequence Analysis of PtEXPA6

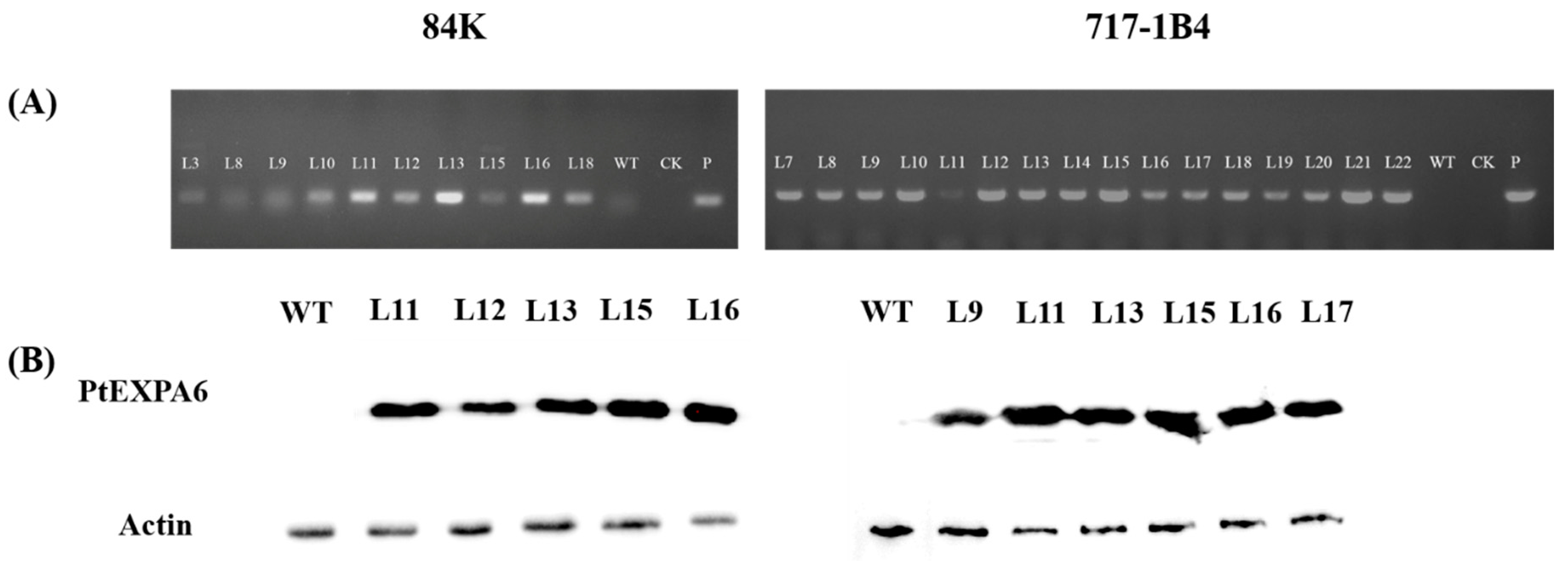

2.3. Overexpression of PtEXPA6 in Poplars

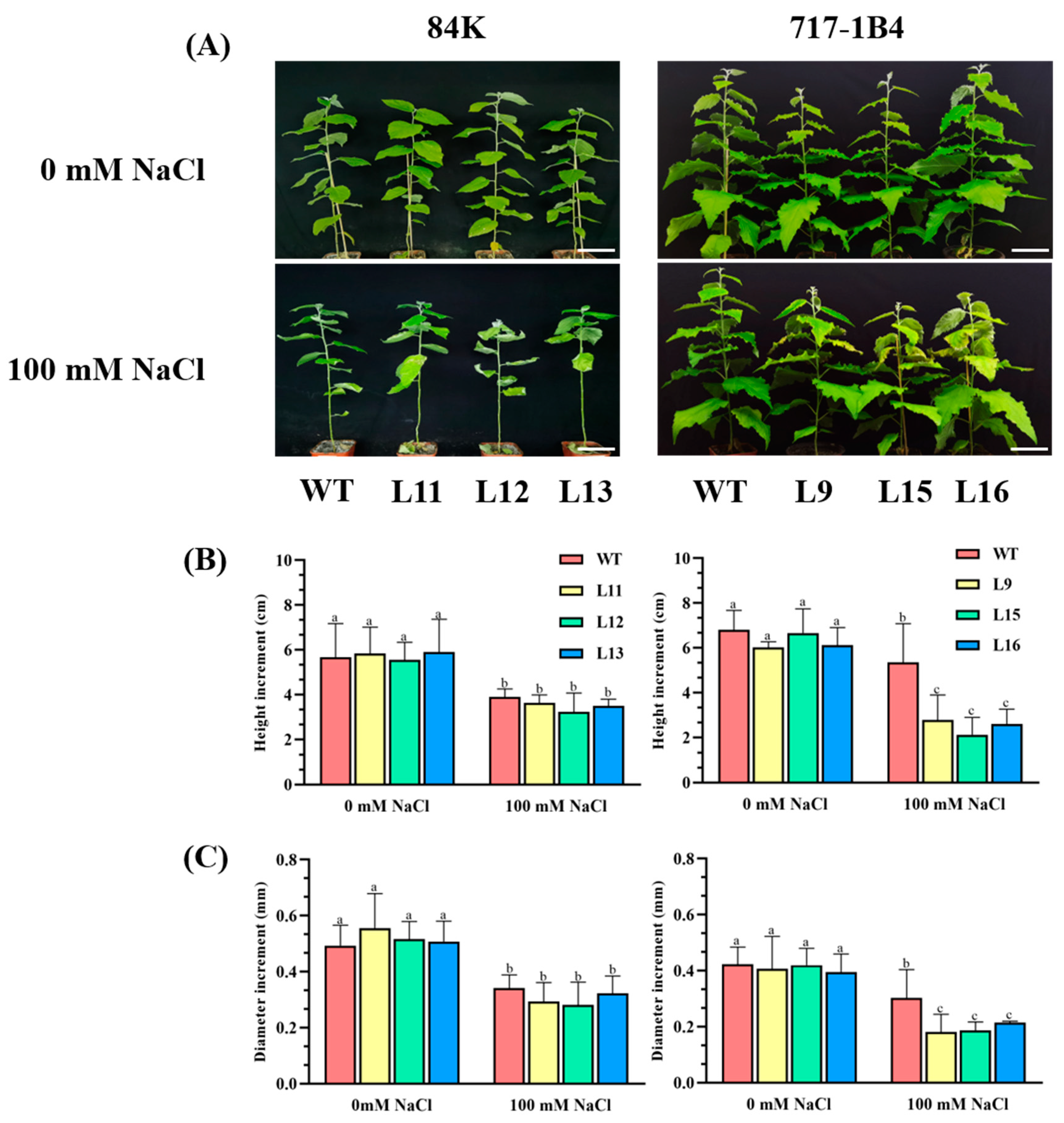

2.4. Effect of Salinity on Shoot Growth of PtEXPA6-Overexpressed Poplars

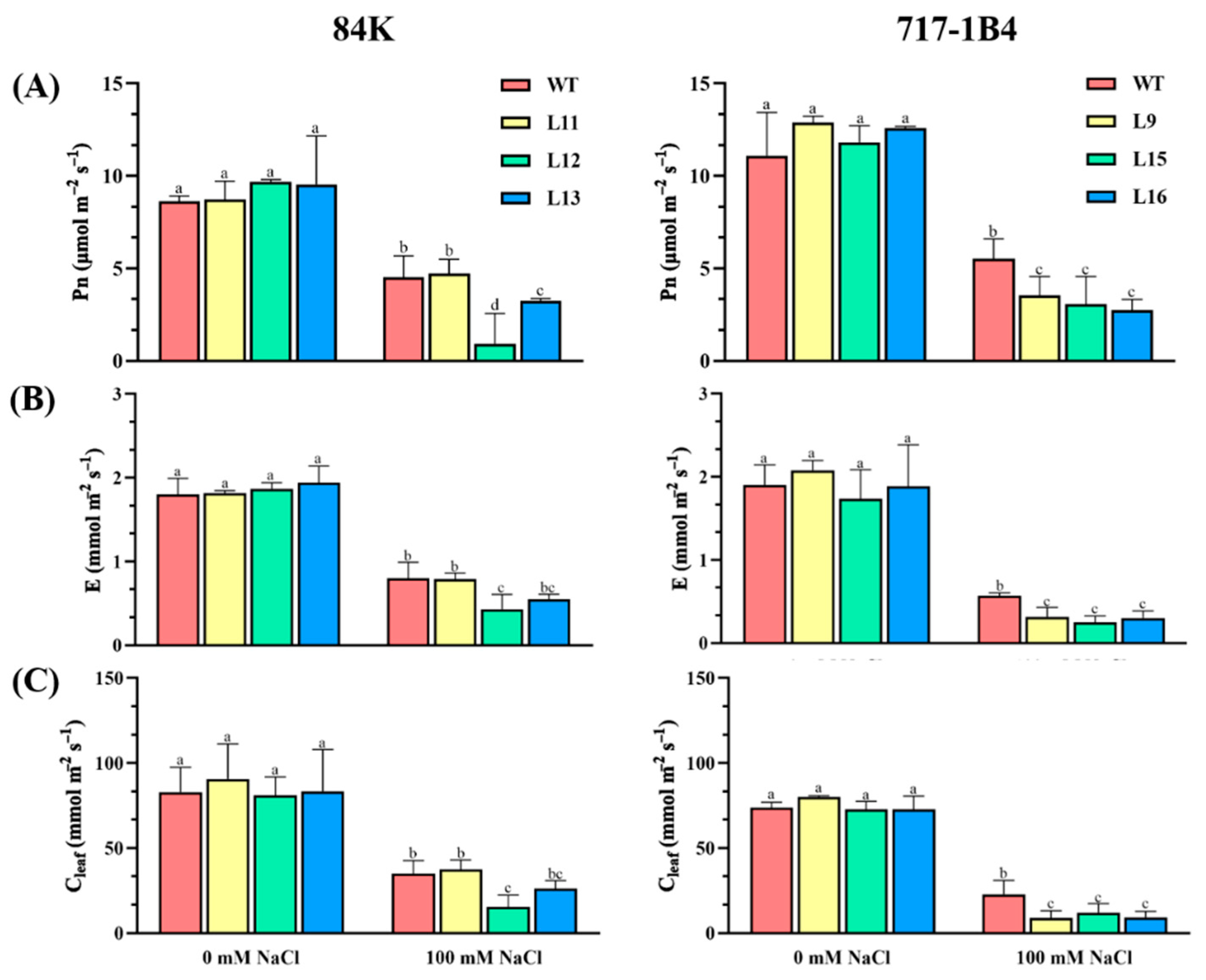

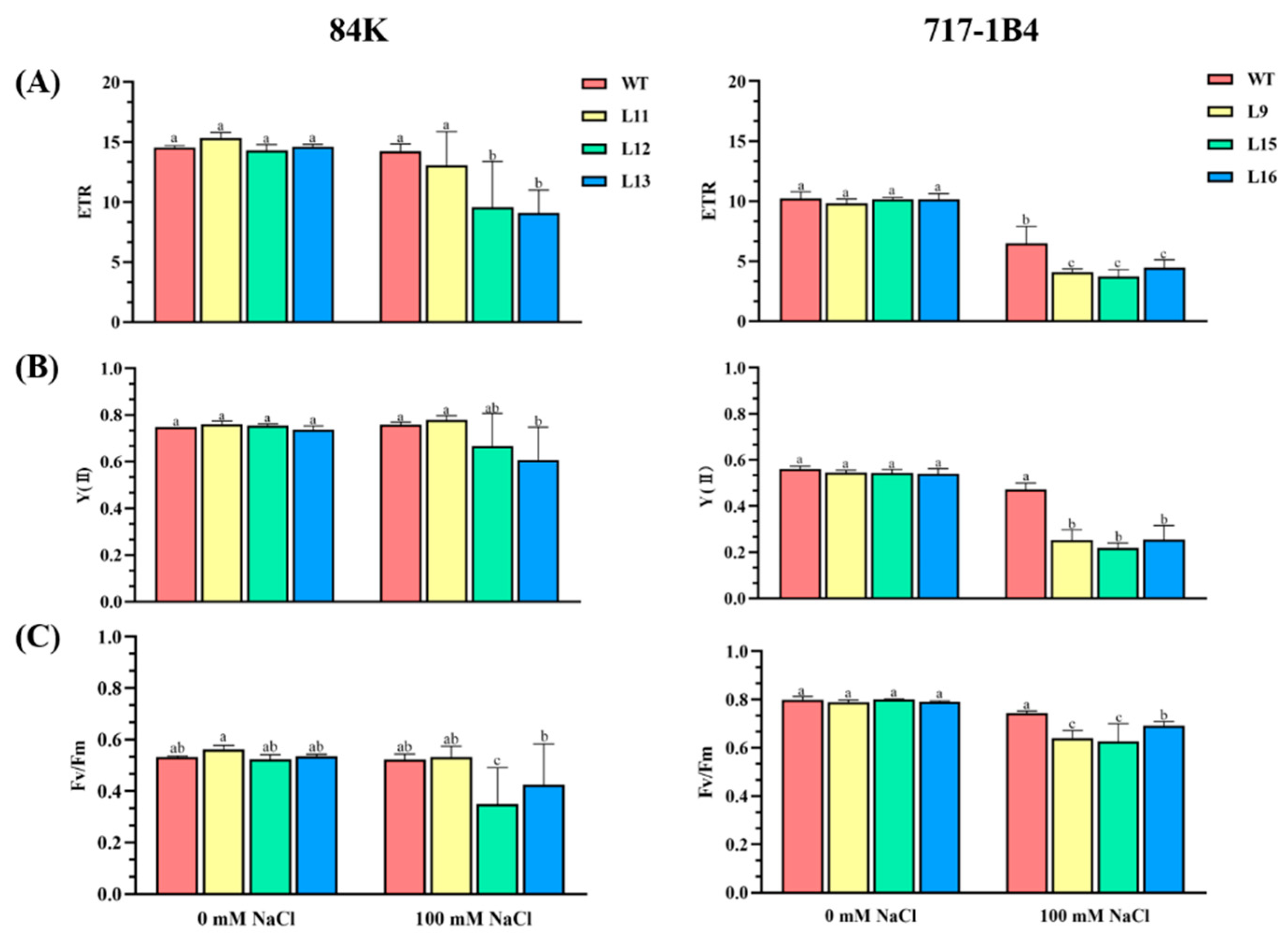

2.5. Effect of Salinity on Photosynthesis of PtEXPA6-Overexpressing Poplars

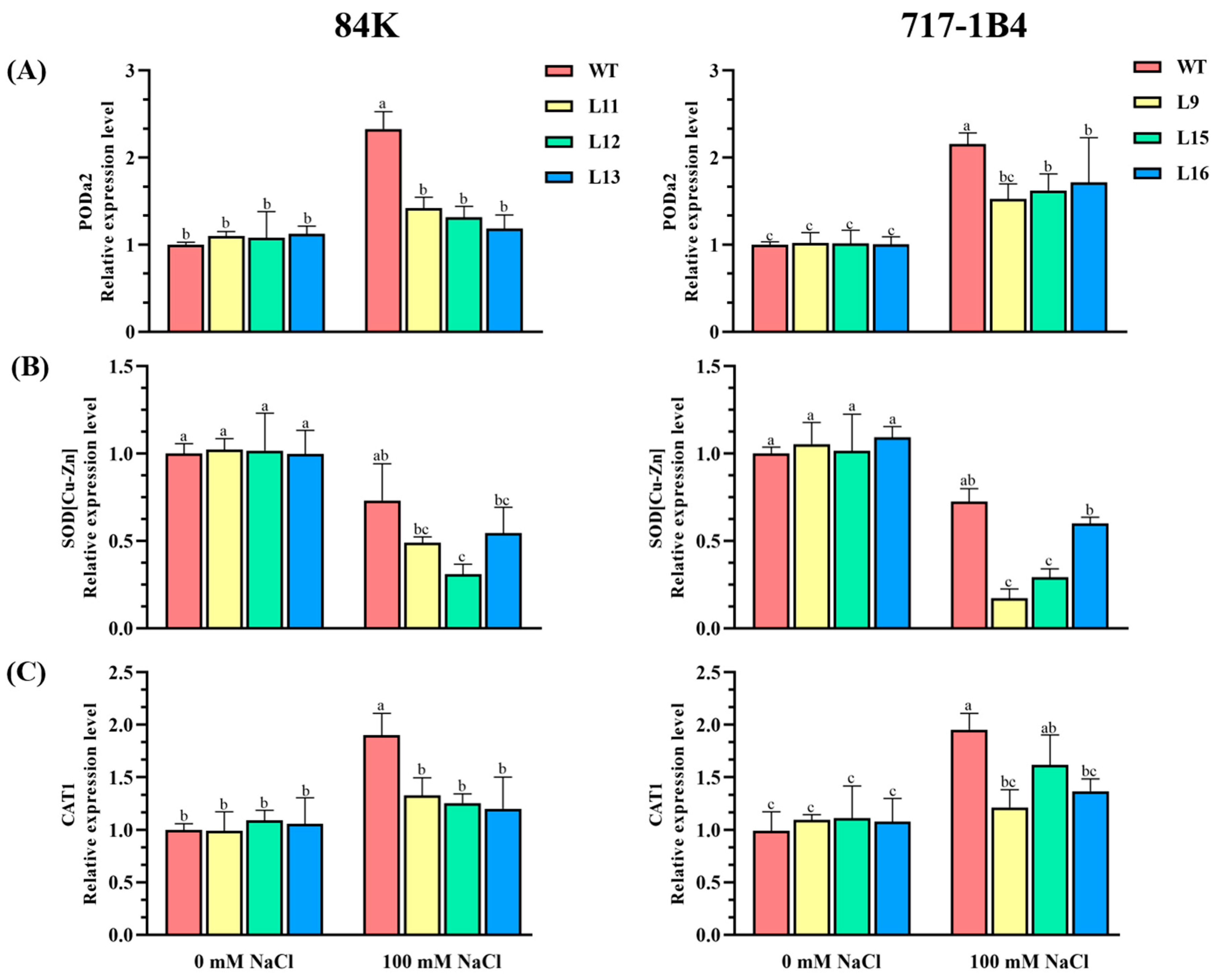

2.6. The Activity and Transcription of Antioxidant Enzymes

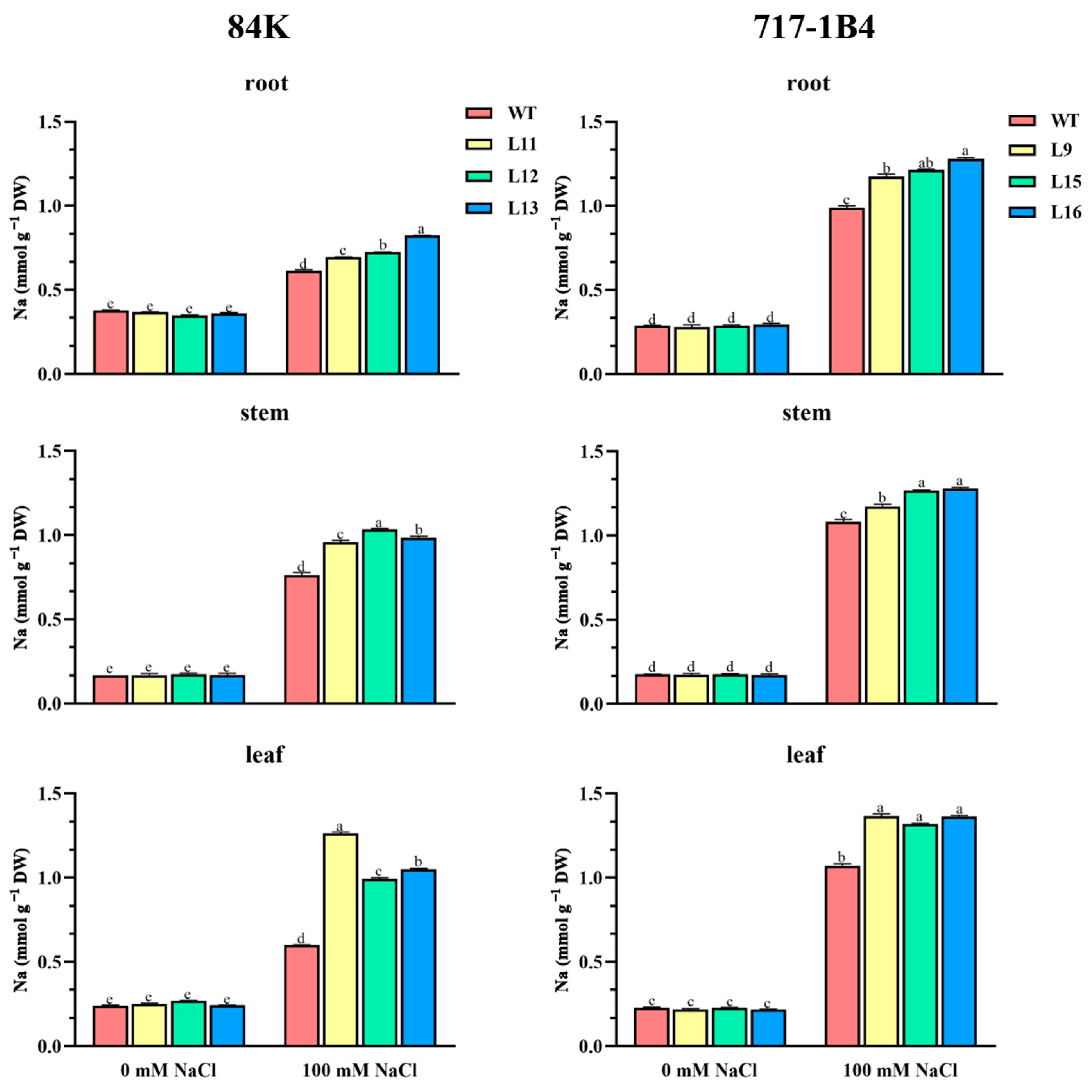

2.7. Na+ Content in Roots, Stems and Leaves of Transgenic Poplars

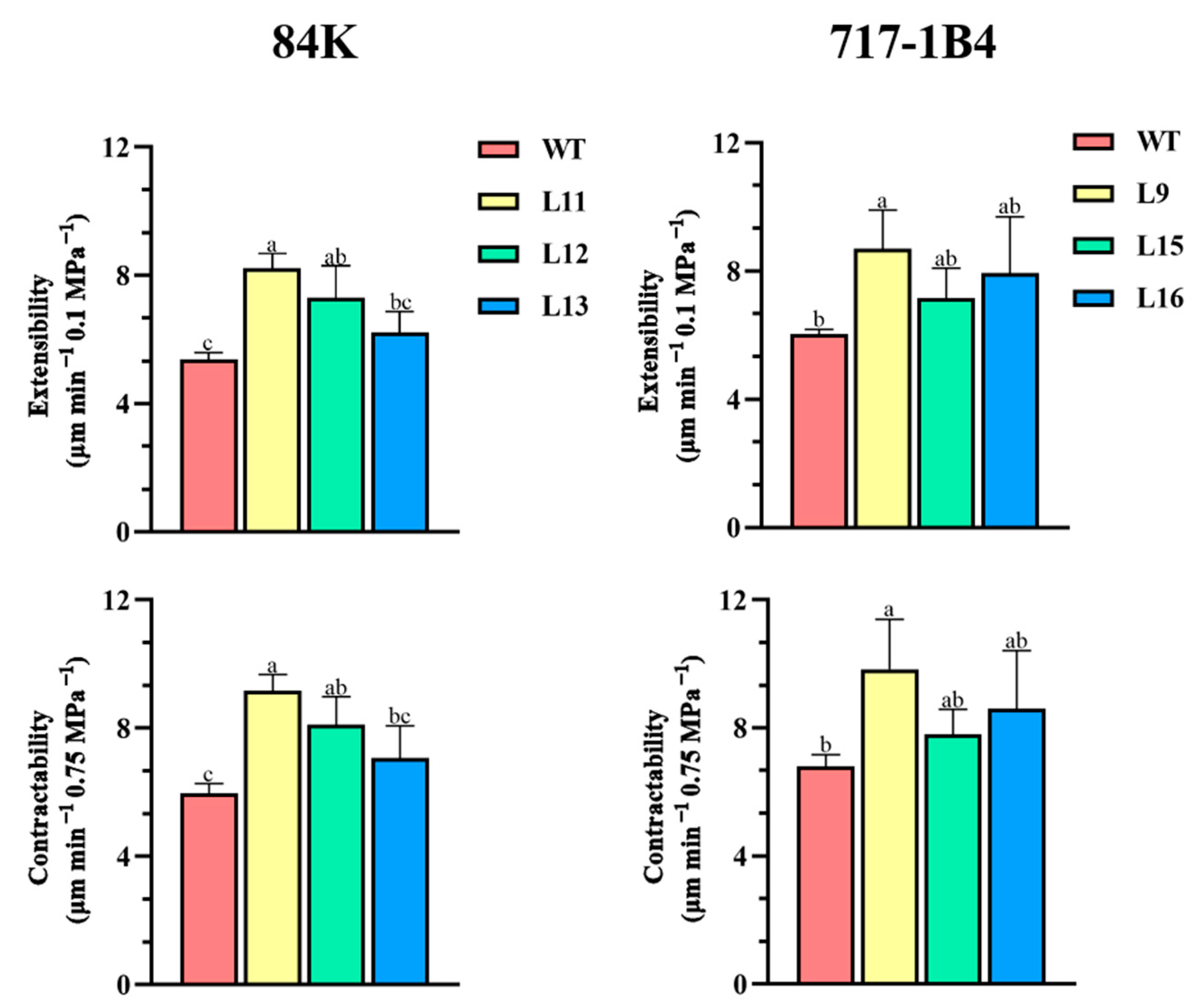

2.8. Comparative Contractability and Comparative Extensibility of Root Cell Walls

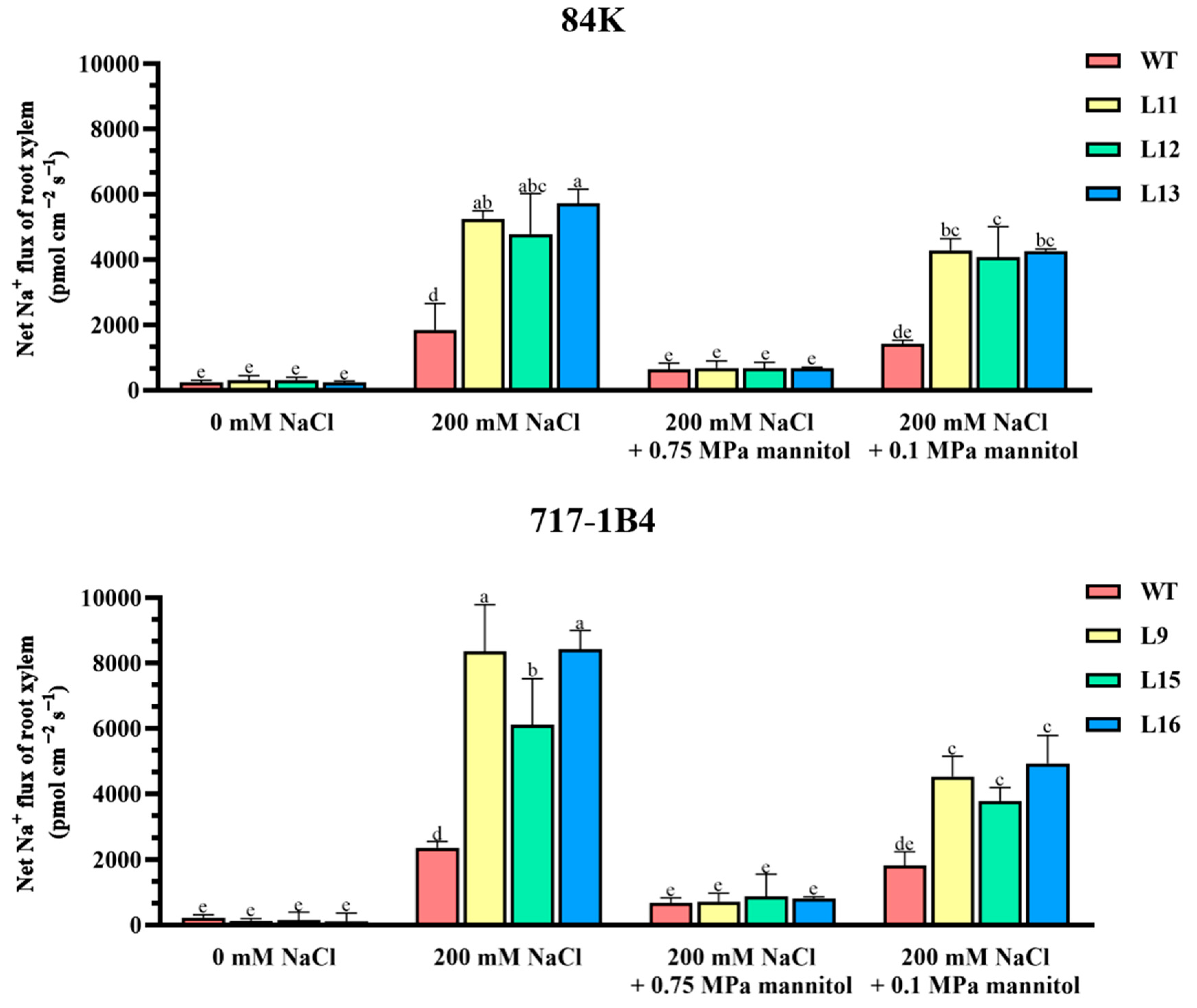

2.9. Na+ Flux of Root Xylem and the Response to Osmotic Jump

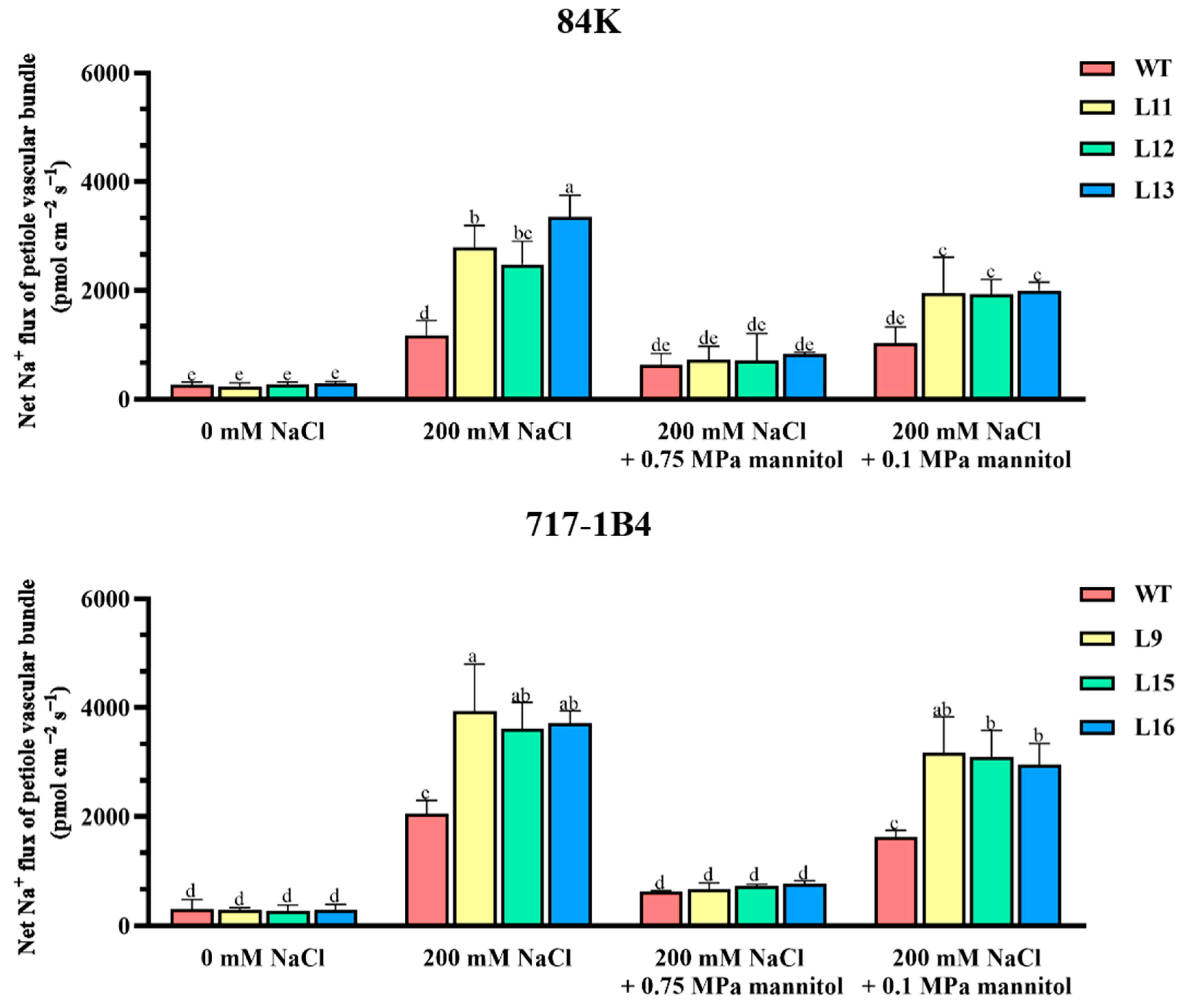

2.10. Na+ Flux of Leaf Petiole Vascular Bundles and the Response to Osmotic Jump

3. Discussion

3.1. PtEXPA6 Negatively Regulates Salt Tolerance in Transgenic Poplars

3.2. PtEXPA6 Increases Na+ Transport from Root to Shoot under Salt Stress

3.3. PtEXPA6 Influences ROS Scavenging Capacity under Salt Stress

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Total RNA Isolation, PtEXPA6 Cloning and Sequence Analysis

4.2. Western Blotting

4.3. Comparative Extensibility and Contractility of Root Tips

4.4. Phenotype Test of Salt Tolerance

4.4.1. Measurement of Growth

4.4.2. Measurement of the Relative Electrolyte Leakage (REL)

4.4.3. Measurement of Leaf Gas Exchange and Chlorophyll Fluorescence

4.5. Determination of Antioxidant Enzyme Activity

4.6. Na+ Concentration in the Roots, Leaves and Stems

4.7. Flux Records of Na+ in the Root Xylem and Leaf Petiole Vascular Bundle

4.8. RT-qPCR Analysis

4.9. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McQueen-Mason, S.J.; Durachko, D.M.; Cosgrove, D.J. Two endogenous proteins that induce cell wall extension in plants. Plant Cell 1992, 4, 1425–1433. [Google Scholar]

- McQueen-Mason, S.J.; Cosgrove, D.J. Disruption of hydrogen- bonding between plant cell wall polymers by proteins that induce wall extension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 6574–6578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenhaken, R. Cell wall remodeling under abiotic stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 5, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Z.S.; Liu, Y.L.; Deng, X.; Liu, D.M.; Hu, Y.K.; Yan, Y.M. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of expansin gene family incommon wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Genomics 2019, 20, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.J.; Zou, W.S.; Fei, C.Y.; Wu, G.; Li, X.Y.; Lin, H.H.; Xi, D.H. α-Expansin EXPA4 positively regulates abiotic stress tolerance but negatively regulates pathogen resistance in Nicotiana tabacum. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 2317–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, Q.; Xu, X.; Liu, H.B.; Zhi, J.K.; Xu, J.C. Transgenic tobacco plants expressing grass AstEXPA1 gene show improved performance to several stresses. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2017, 11, 331–337. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, A.; Wu, M.J.; Yan, L.M.; Hu, R.; Ali, I.; Gan, Y.B. AtEXP2 is involved in seed germination and abiotic stress response in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.X.; Yang, L.H.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.K.; Xu, J.C. Over-expression of the Salix matsudana expansin gene SmEXPA23 enhances plant salt tolerance. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2023, 152, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, H.B.; Yang, R.X.; Xu, X.; Liu, X.; Xu, J.C. Over-expression of PttEXPA8 gene showed various resistances to diverse stresses. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 130, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marowa, P.; Ding, A.M.; Xu, Z.C.; Kong, Y.Z. Overexpression of NtEXPA11 modulates plant growth and development and enhances stress tolerance in tobacco. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 151, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, P.T.; Kang, M.; Jiang, X.Q.; Dai, F.W.; Gao, J.P.; Zhang, C.Q. RhEXPA4, a rose expansin gene, modulates leaf growth and confers drought and salt tolerance to Arabidopsis. Planta 2013, 237, 1547–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadamba, C.; Kang, K.; Paek, N.C.; Lee, S.I.; Yoo, S.C. Overexpression of rice expansin7 (OsEXPA7) confers enhanced tolerance to salt stress in rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.Y.; Li, A.X.; Li, F.; Zhao, M.R.; Wang, W. Characterization of a wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) expansin gene, TaEXPB23, involved in the abiotic stress response and phytohormone regulation. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2012, 54, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.H.; Han, Y.Y.; Kong, X.Z.; Kang, H.H.; Ren, Y.Q.; Wang, W. Ectopic expression of wheat expansin gene TaEXPA2 improved the salt tolerance of transgenic tobacco by regulating Na+/K+ and antioxidant competence. Physiol. Plant. 2017, 159, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.J.; Yao, M.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhan, J.Y.; Yan, J.; Jiang, S.Q.; Jian, S.S.; Chen, H.; Bu, T.L.; et al. Involvement of auxin-mediated CqEXPA50 contributes to salt tolerance in Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) by interaction with auxin pathway genes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.R.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, K.H.; Hong, S.W.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, H. Ectopic expression of Expansin3 or Expansinβ1 causes enhanced hormone and salt stress sensitivity in Arabidopsis. Biotechnol. Lett. 2008, 30, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Liu, K.; Lu, Y.T. Specific roles of AtEXPA1 in plant growth and stress adaptation. Russ J Plant Physl. 2010, 57, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Burgess, P.; Xu, J.C.; Meyer, W.; Huang, B.R. Osmotic stress- and salt stress-inhibition and gibberellin-mitigation of leaf elongation associated with up-regulation of genes controlling cell expansion. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016, 131, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.L.; Polle, A. On the salty side of life: Molecular, physiological and anatomical adaptation and acclimation of trees to extreme habitats. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 1794–1816. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, P.M.; Leon, D. Physical restraints underlying short-term inhibition by auxin of root elongation in intact maize seedlings. J. Plant Growth Regul. 1992, 11, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, P.; Azaizeh, H.; Leon, D. Hardening of root cell walls: A growth inhibitory response to salinity stress. Plant Cell Environ. 1994, 17, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.L.; Polle, A. Salinity tolerance of Populus. Plant Biol. 2010, 12, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Li, J.; Wang, S.; Hüttermann, A.; Altman, A. Salt, nutrient uptake and transport, and ABA of Populus euphratica; a hybrid in response to increasing soil NaCl. Trees. 2001, 15, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.L.; Li, J.K.; Fritz, E.; Wang, S.S.; Hüttermann, A. Sodium and chloride distribution in roots and transport in three poplar genotypes under increasing NaCl stress. For. Ecol. Manage 2002, 168, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.L.; Li, J.K.; Wang, S.S.; Fritz, E.; Hüttermann, A.; Altman, A. Effects of NaCl on shoot growth, transpiration, ion compartmentation, and transport in regenerated plants of Populus euphratica and Populus tomentosa. Can. J. For. Res. 2003, 33, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmanoff, K.M.; Evans, M.L. Kinetics of adaptation of osmotic stress in lentil (Lens culinaris Med.) roots. Plant Physiol. 1981, 68, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsaio, T.C.; Jing, J. Leaf and root expansive growth in response to water deficits. Physiology of cell expansion during plant growth 1987, 180–192. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Wang, R.G.; Liu, Z.Q.; Ding, Y.Z.; Li, T.Q. Non-invasive microelectrode cadmium flux measurements reveal the spatial characteristics and real-time kinetics of cadmium transport in hyperaccumulator and nonhyperaccumulator ecotypes of Sedum alfredii. J. Plant Physiol. 2013, 170, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronzucker, H.J.; Britto, D.T. Sodium transport in plants: A critical review. New phytol. 2011, 189, 54–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Flowers, T.J.; Gong, H. Silicon decreases chloride transport in rice (Oryza sativa L.) in saline conditions. J. Plant Physiol. 2013, 170, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meychik, N.R.; Yermakov, I.P.; Khonarmand, S.D.; Nikolaeva, Y.I. Ion-exchange properties of cell walls in chickpea cultivars with different sensitivities to salinity. Russ J Plant Physl. 2010, 57, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meychik, N.; Nikolaeva, Y.; Kushunina, M. The significance of ion-exchange properties of plant root cell walls for nutrient and water uptake by plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 166, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.G.; Chen, S.L.; Zhou, X.Y.; Shen, X.; Deng, L.; Zhu, H.J.; Shao, J.; Shi, Y.; Dai, S.X.; Fritz, E.; et al. Ionic homeostasis and reactive oxygen species control in leaves and xylem sap of two poplars subjected to NaCl stress. Tree Physiol. 2008, 28, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.G.; Chen, S.L.; Deng, L.; Fritz, E.; Hüttermann, A.; Polle, A. Leaf photosynthesis, fluorescence response to salinity and the relevance to chloroplast salt compartmentation and anti-oxidative stress in two poplars. Trees 2007, 21, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.Y.; Chen, S.L.; Zhou, X.Y.; Li, C.Y.; Shao, J.; Wang, R.G.; Fritz, E.; Hüttermann, A.; Polle, A. Effect of NaCl on photosynthesis, salt accumulation and ion compartmentation in two mangrove species, Kandelia candel and Bruguiera gymnorhiza. Aquat. Bot. 2008, 88, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.Y.; Zhou, X.Y.; Wang, R.G.; Li, J.K.; Lu, C.F.; Chen, S.L. Salt compartmentation and antioxidant defense in roots and leaves of two non-salt secretor mangroves under salt stress. In Mangrove Ecosystem Ecology and Function 2018, 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.L.; Deng, C.; Wu, X.; Yao, J.; Zhang, Y.L.; Zhang, Y.N.; Deng, S.R.; Zhao, N.; Zhao, R.; Zhou, X.Y. Populus euphratica remorin 6.5 activates plasma membrane H+-ATPases to mediate salt tolerance. Tree Physiol. 2020, 40, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhao, R.; Liu, J.; Yao, J.; Ma, S.; Yin, K.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yan, C.; Zhao, N.; et al. Populus euphratica GRP2 interacts with target mRNAs to negatively regulate salt tolerance by interfering with photosynthesis, Na+, and ROS homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Dai, S.X.; Wang, R.G.; Chen, S.L.; Li, N.Y.; Zhou, X.Y.; Lu, C.F.; Shen, X.; Zheng, X.J.; Hu, Z.M.; et al. Calcium mediates root K+/Na+ homeostasis in poplar species differing in salt tolerance. Tree Physiol. 2009, 29, 1175–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.D.; Sun, J.; Yao, J.; Wang, S.J.; Ding, M.Q.; Zhang, H.L.; Qian, Z.Y.; Zhao, N.; Sa, G.; Zhao, R.; et al. High rates of virus-induced gene silencing by tobacco rattle virus in Populus. Tree Physiol. 2015, 35, 1016–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).