Submitted:

11 August 2024

Posted:

14 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Aims and Objectives

3. Literature Review

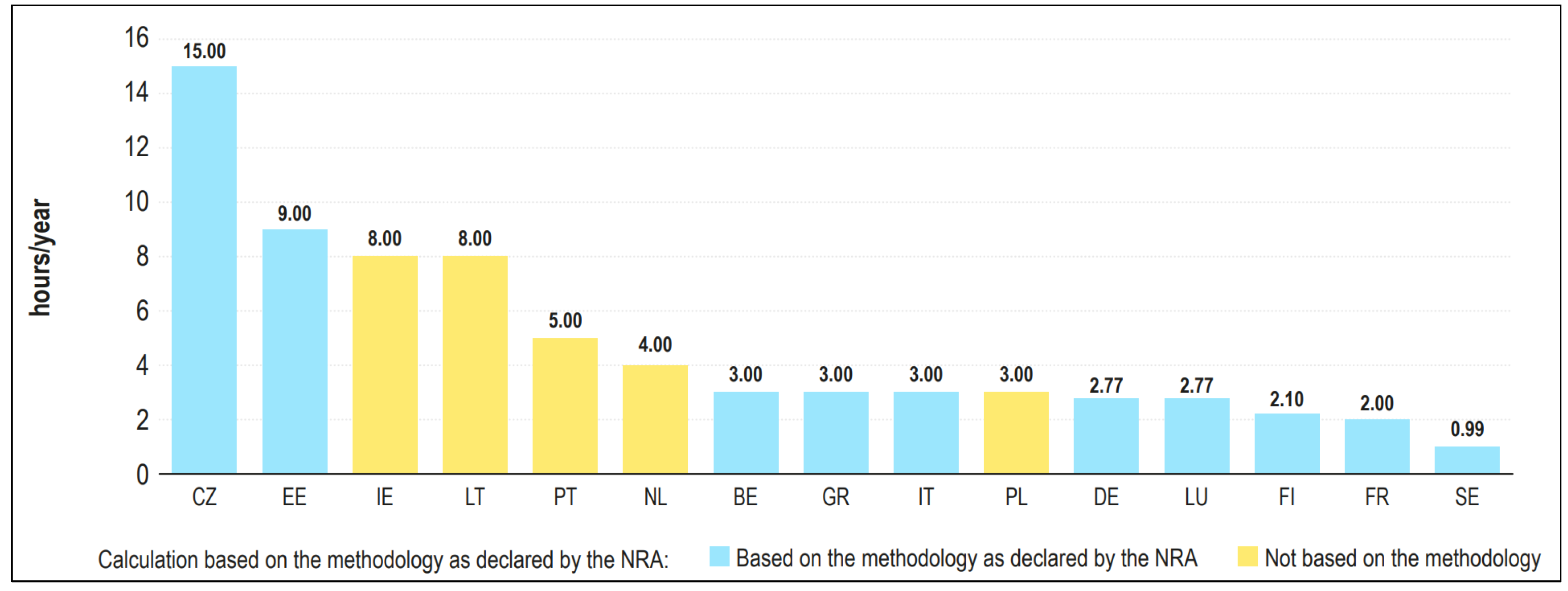

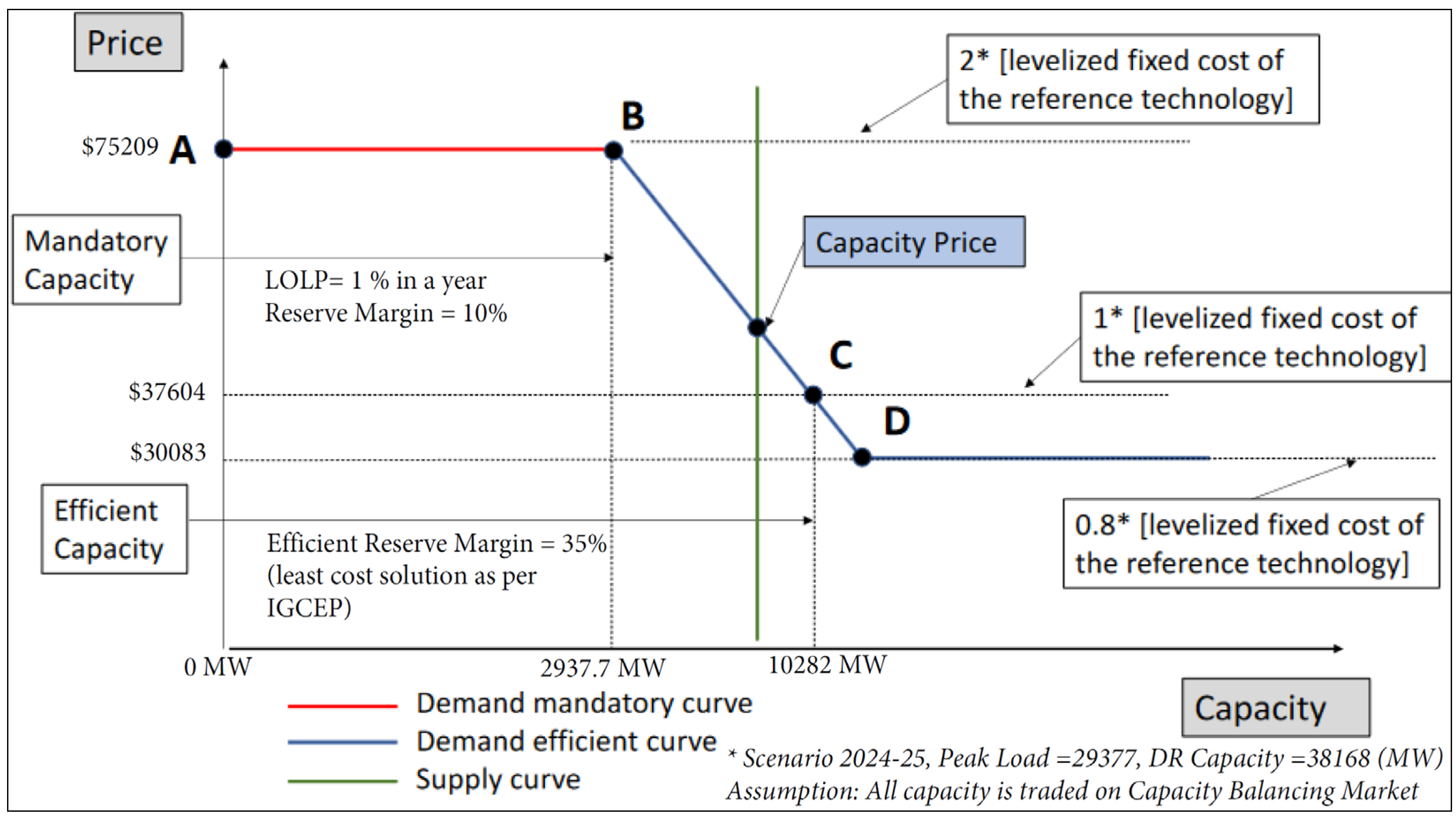

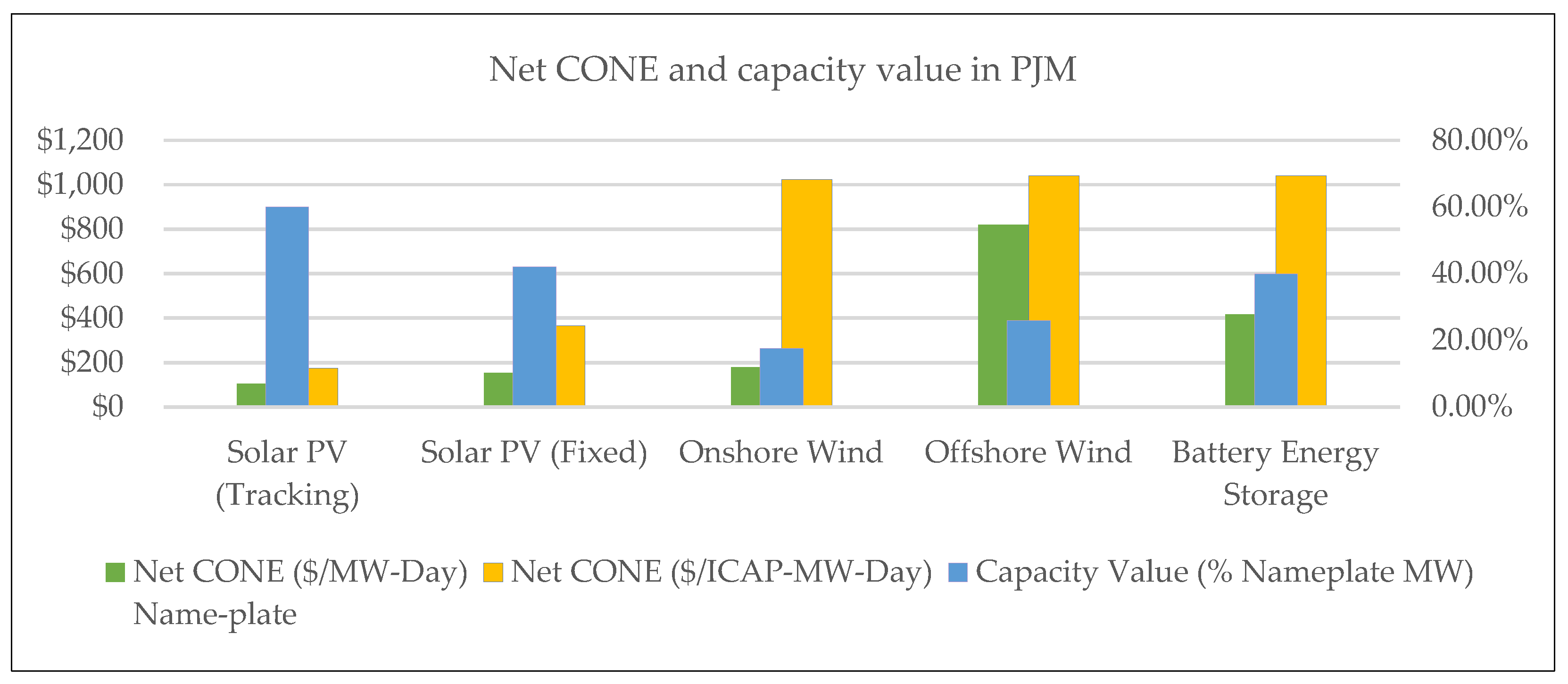

4. Estimating Resource Adequacy

- LOLERT: The Loss of Load Expectation threshold for the reference new entry, measured in hours. Threshold represents the point where the cost of adding new capacity (both fixed and variable costs) is equal to the value of avoiding an hour of lost load.

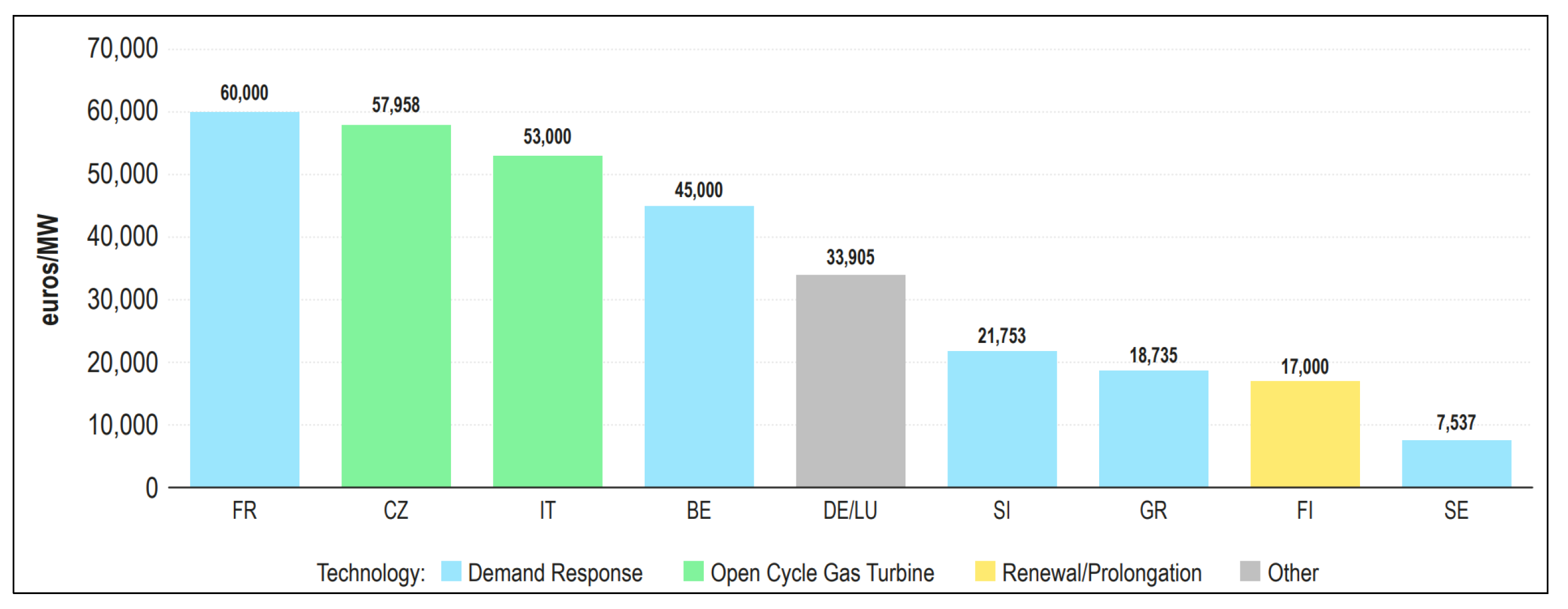

- CONEfixed: The best estimate of the fixed Cost of New Entry, expressed in local currency per MW, according to established guidelines.

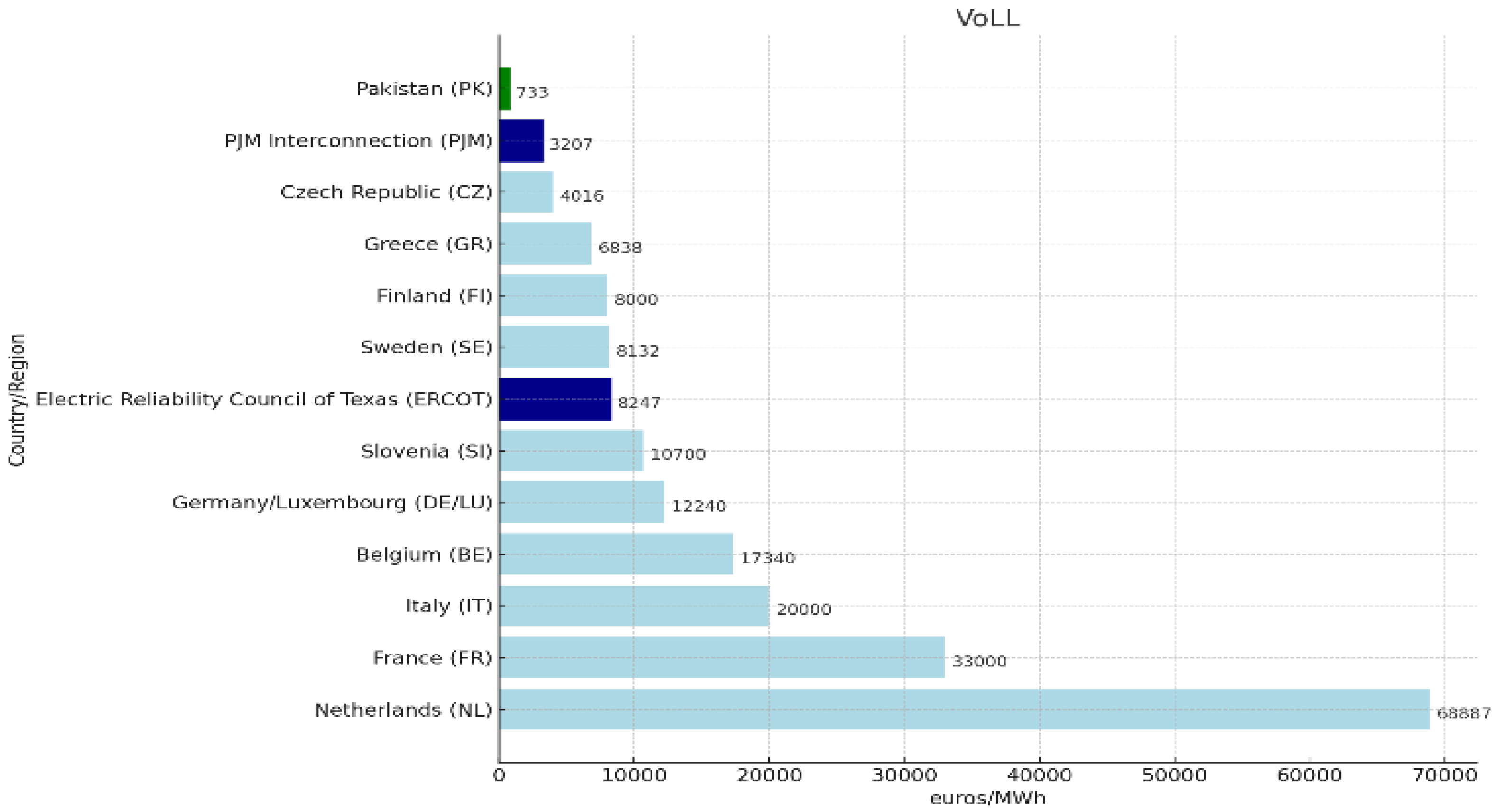

- VOLLRS: The best estimate of the single Value of Lost Load for reliability standards, measured in local currency per MWh, as per established guidelines.

- CONEvar: The best estimate of the variable Cost of New Entry, expressed in local currency per MWh. If the CONEvar is negligible compared to VOLLRS, it can be disregarded.

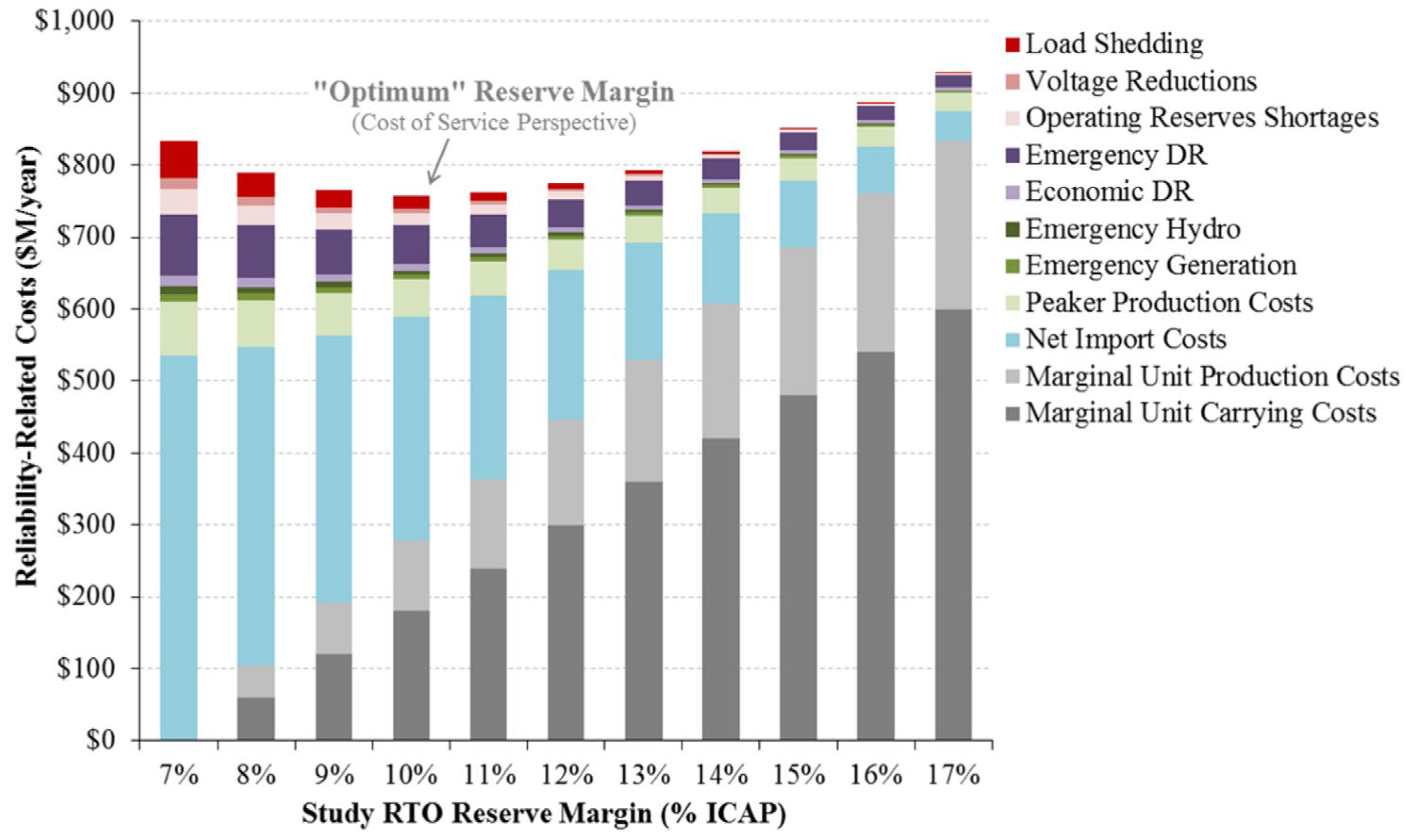

5. Estimating Reserve Margin

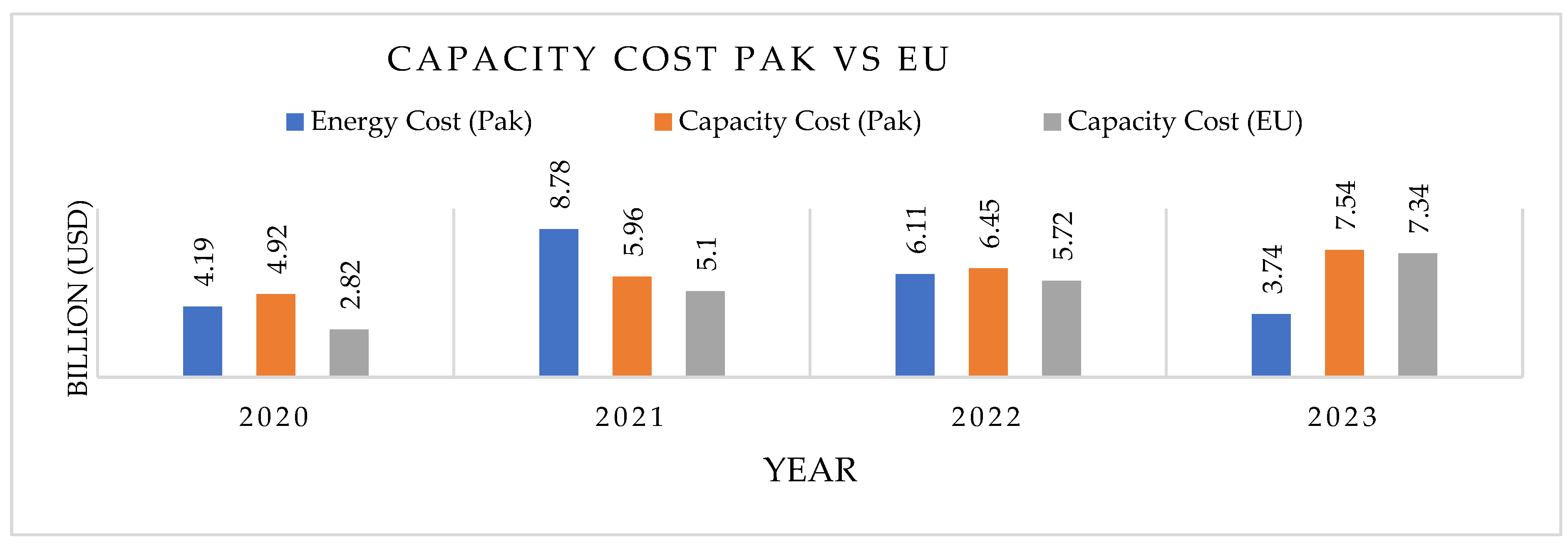

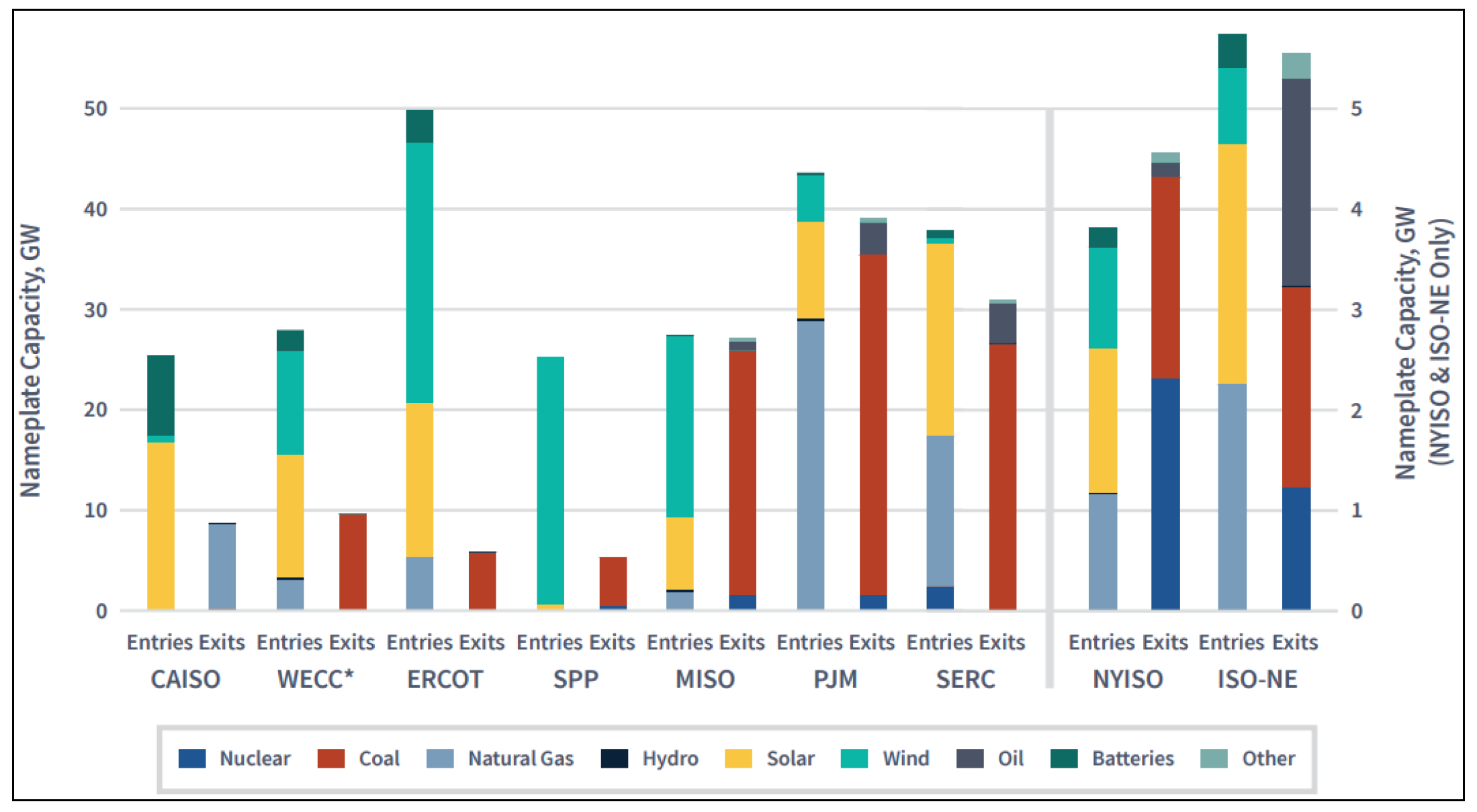

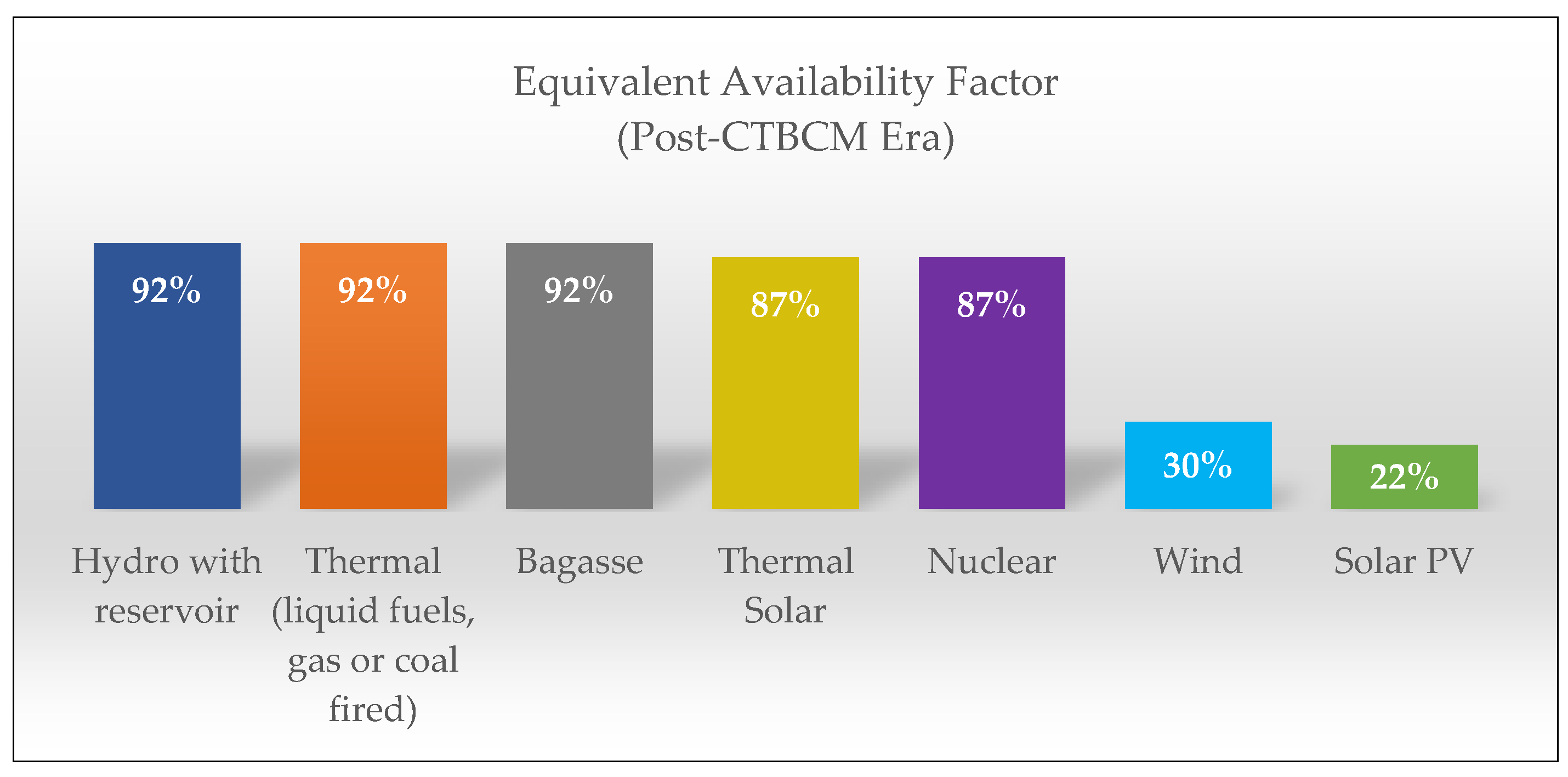

6. Resource Adequacy Framework in US, EU and Pakistan

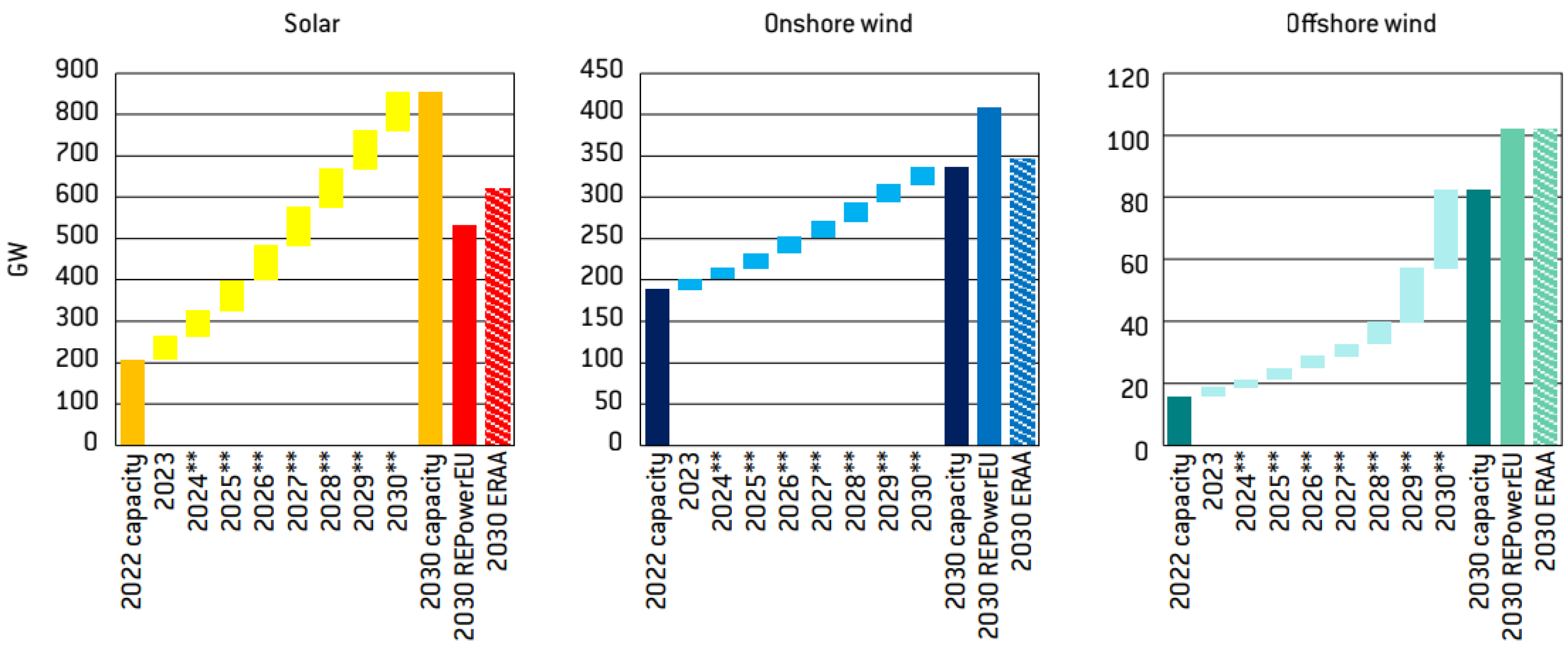

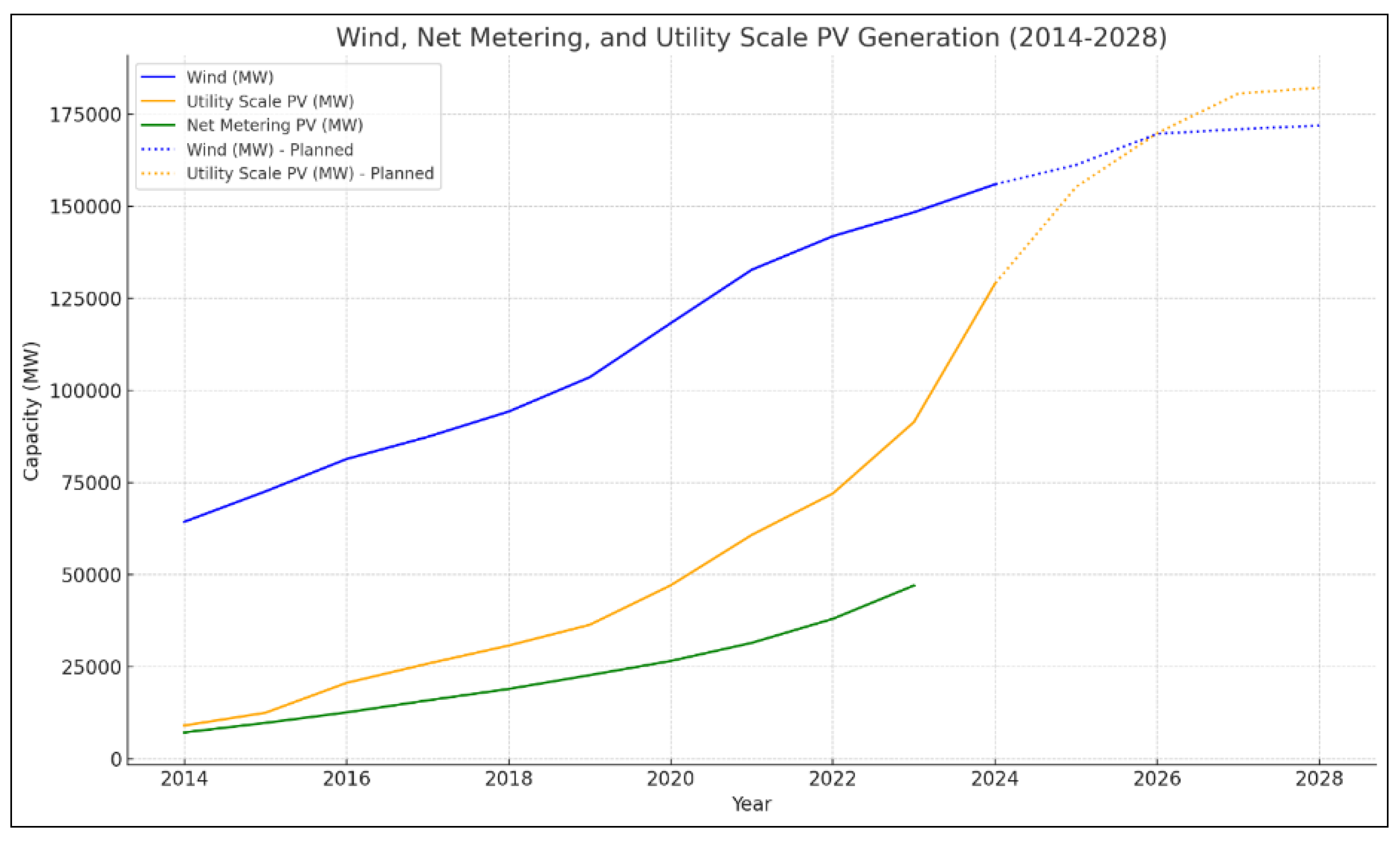

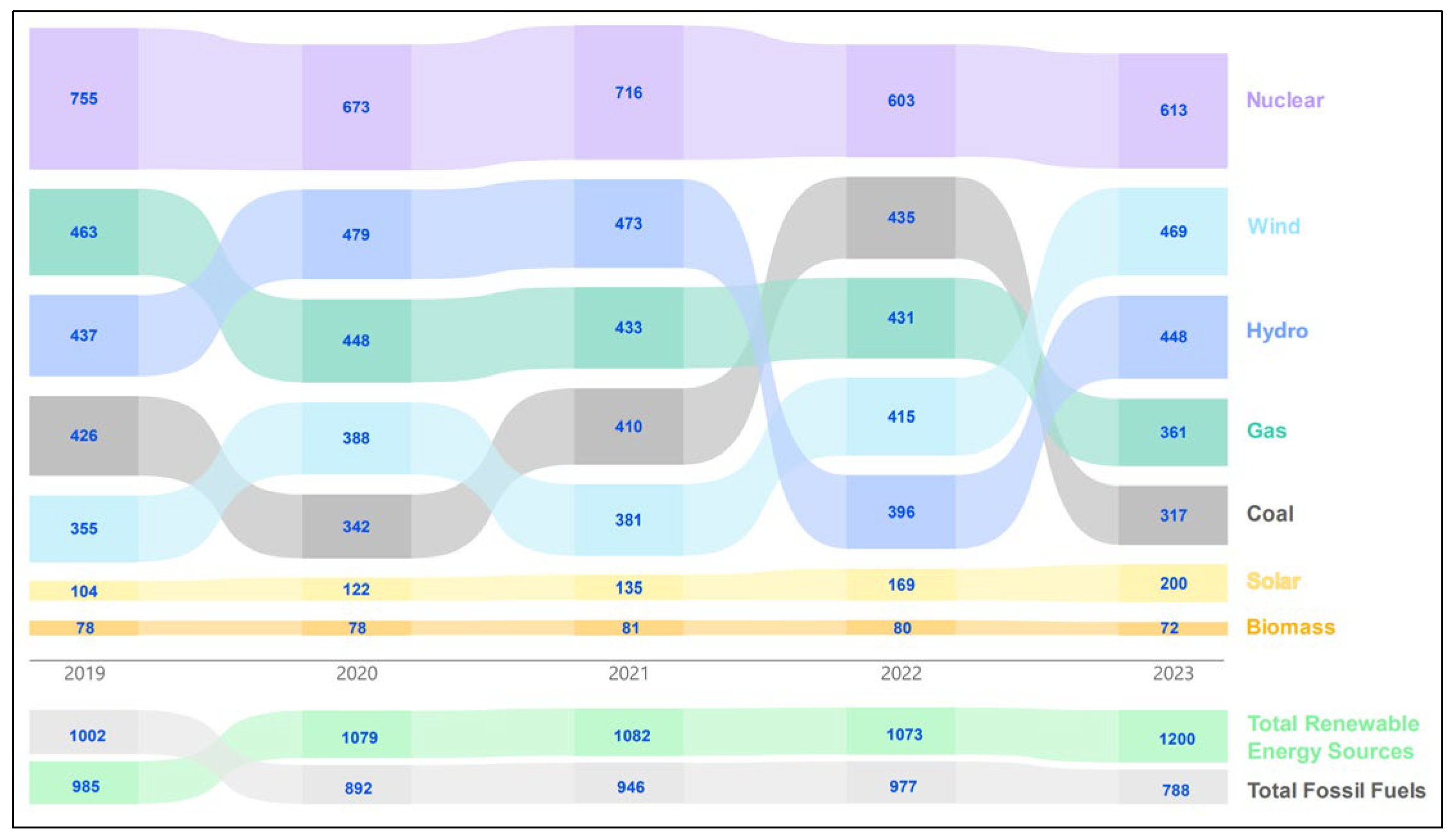

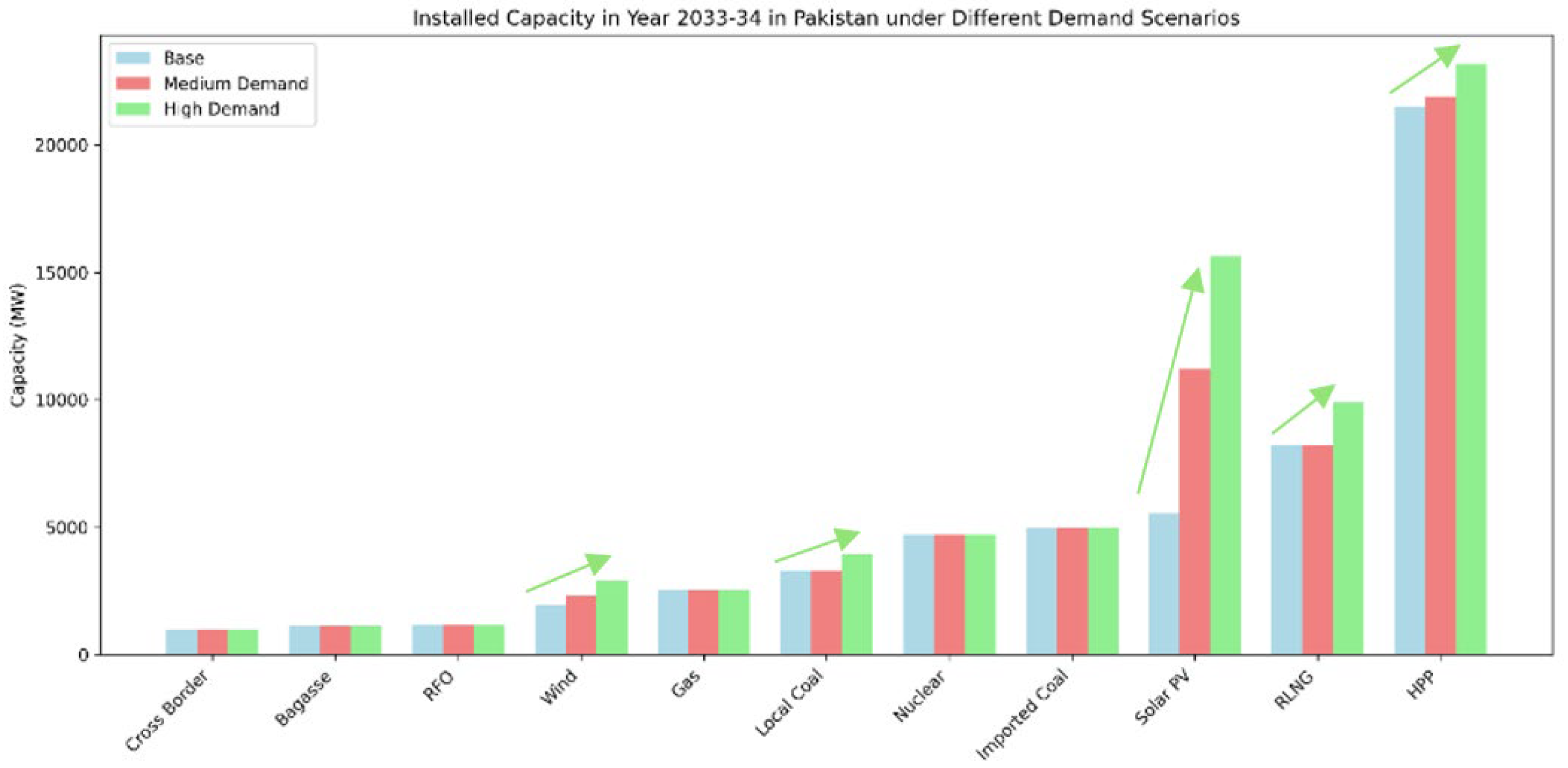

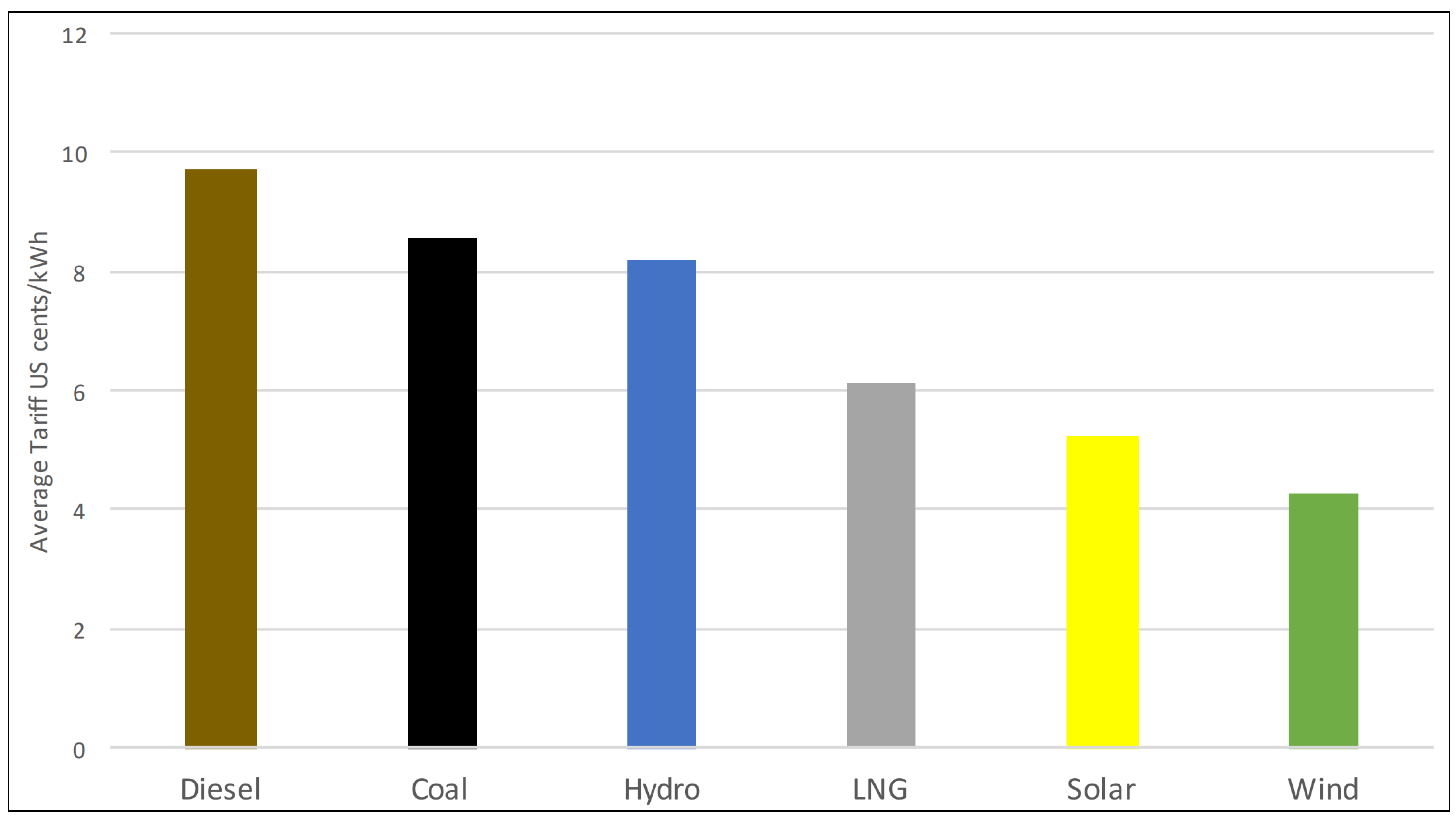

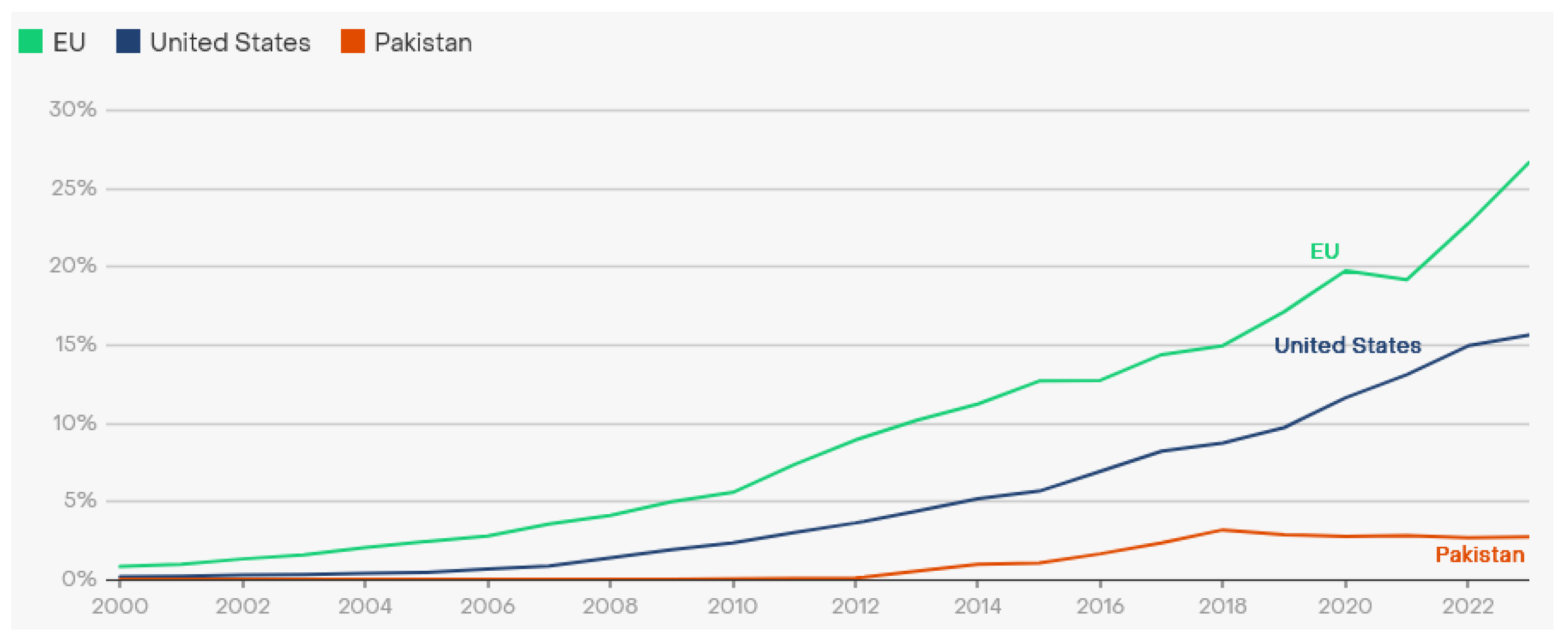

7. Rise of Renewables

7.1. Background

7.2. Stages of Renewable Integration

8. Renewable induced Resource Adequacy Challenges

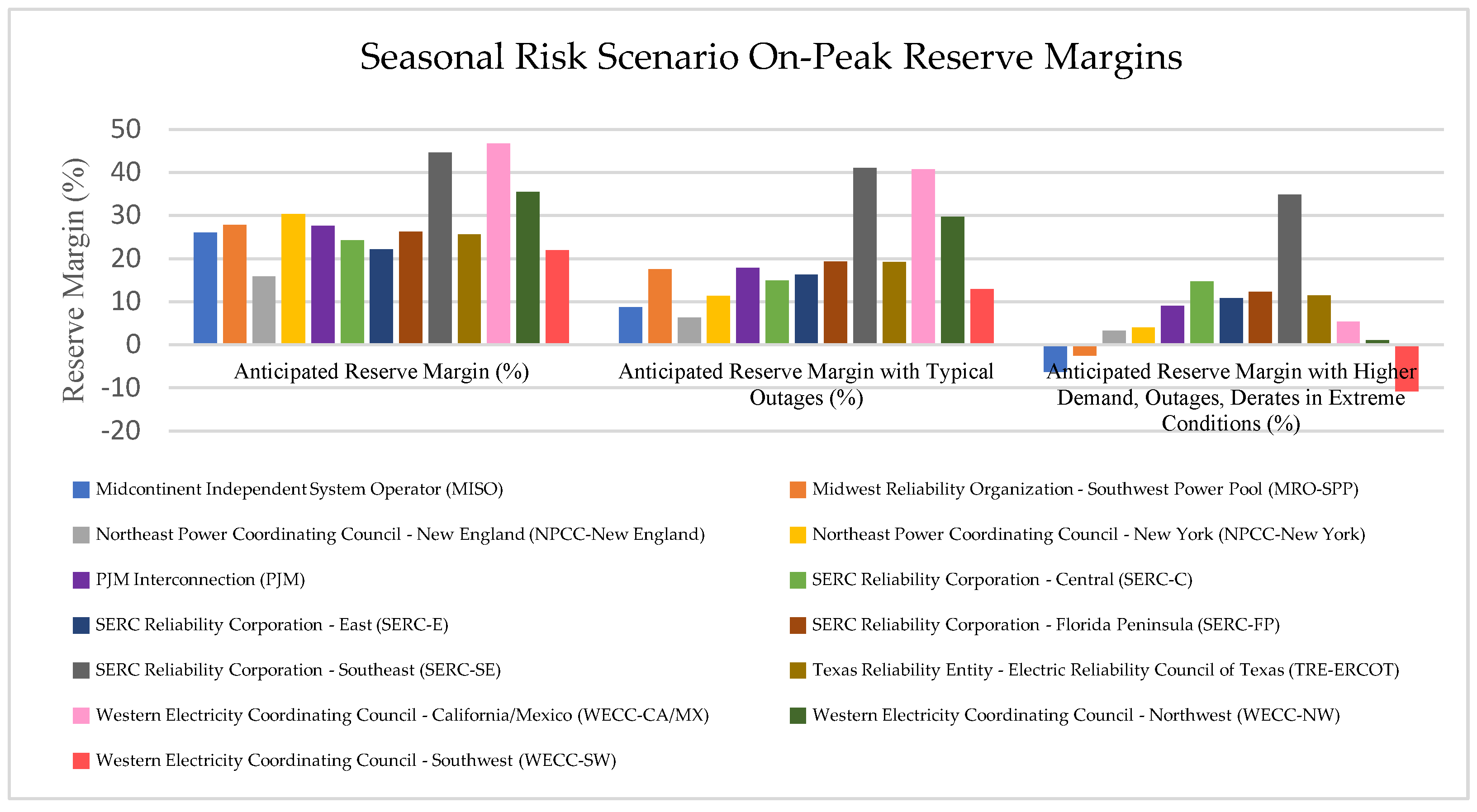

8.1. Diminished Reserve Margins

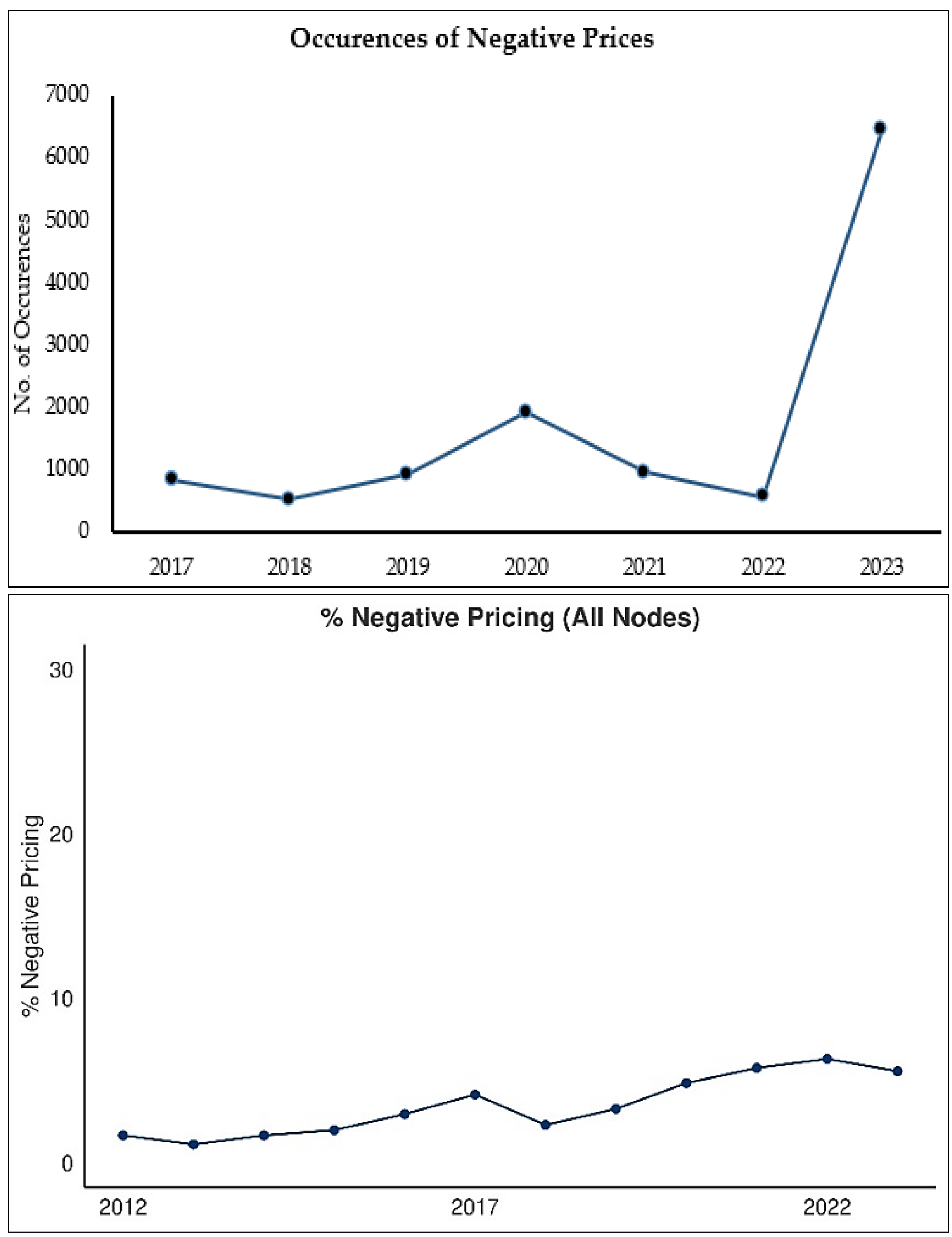

8.2. Negative Pricing

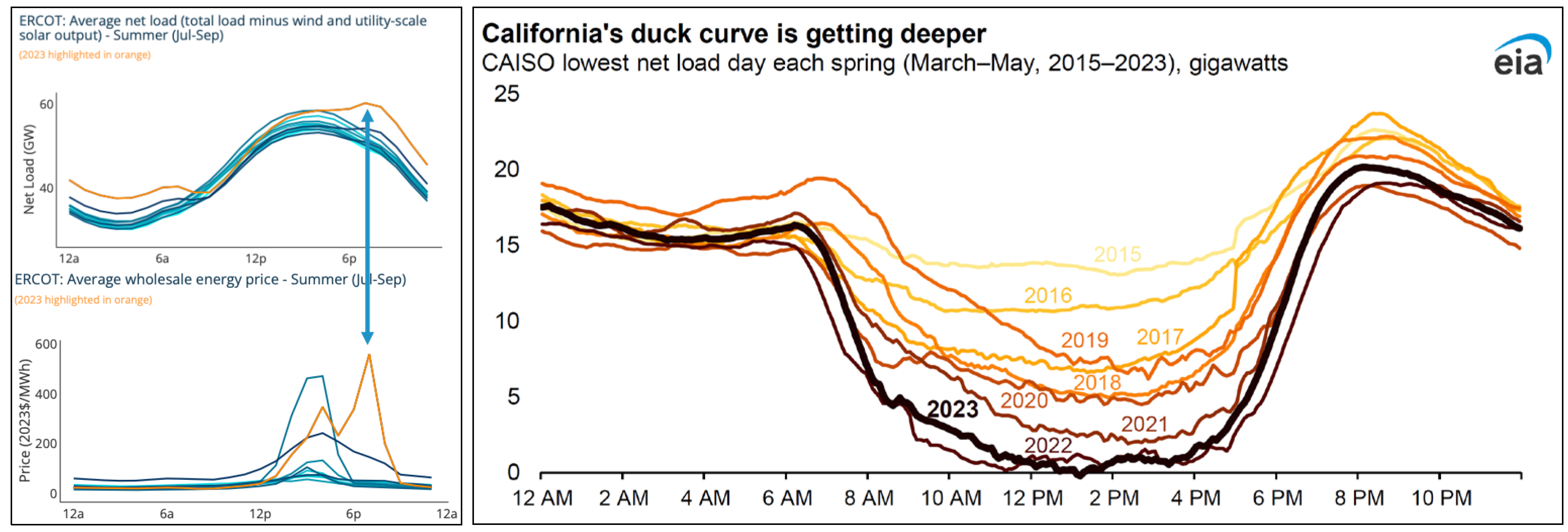

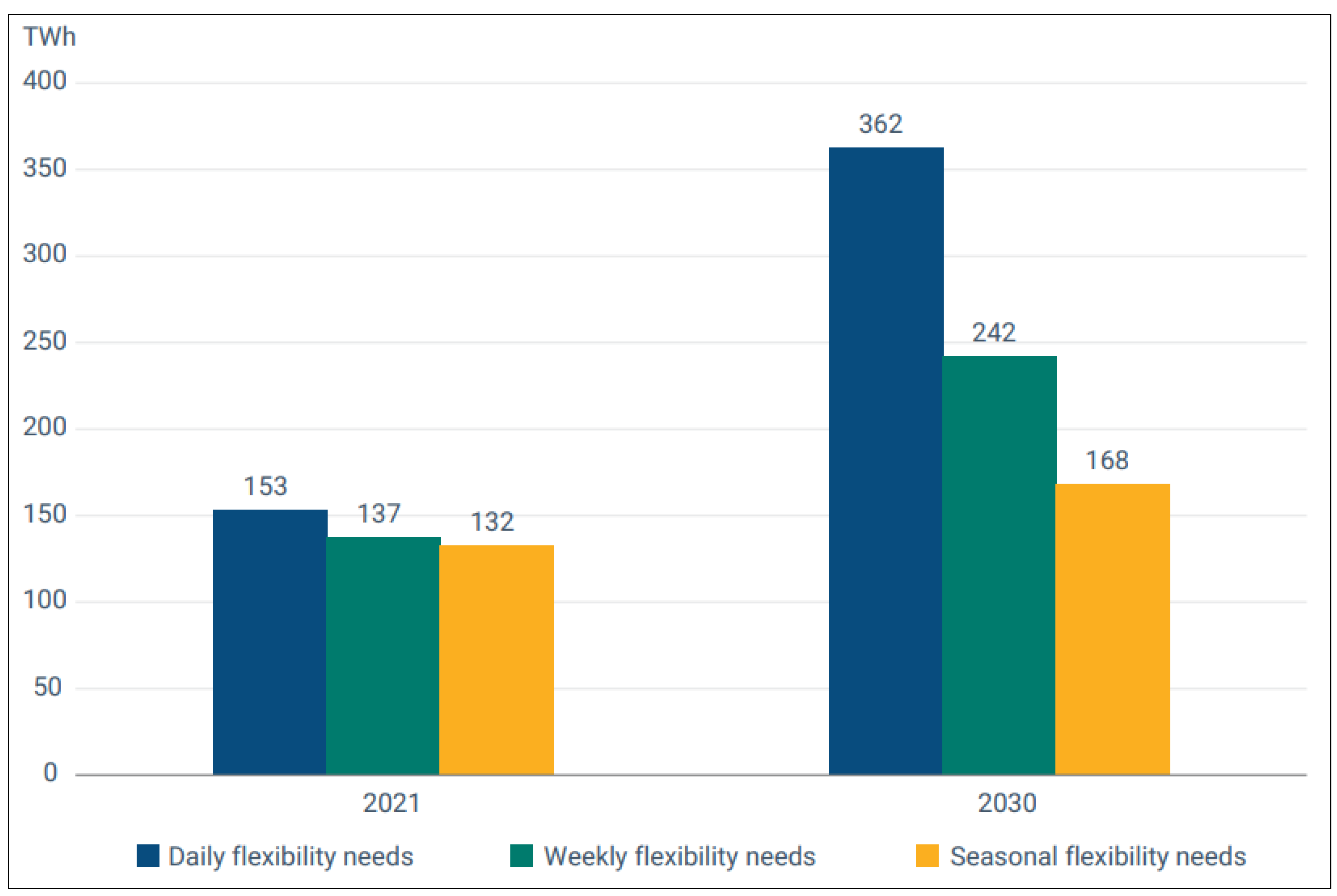

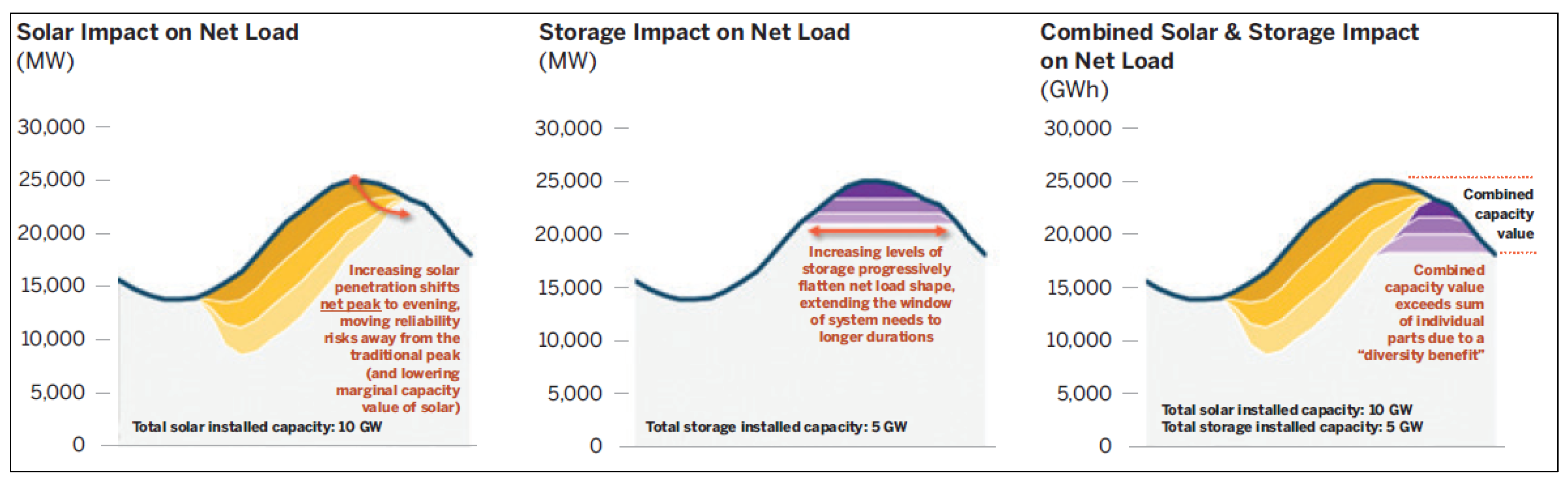

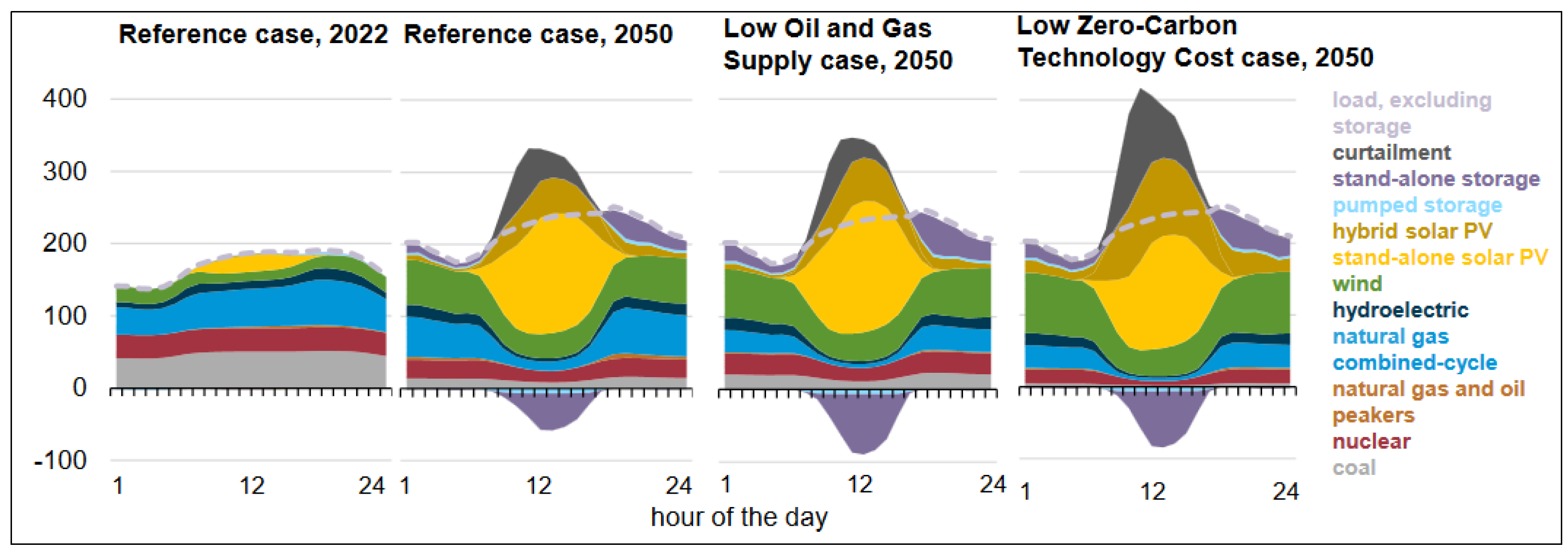

8.3. Shifting of Net-Peak Demand and Enhanced Flexibility Requirements

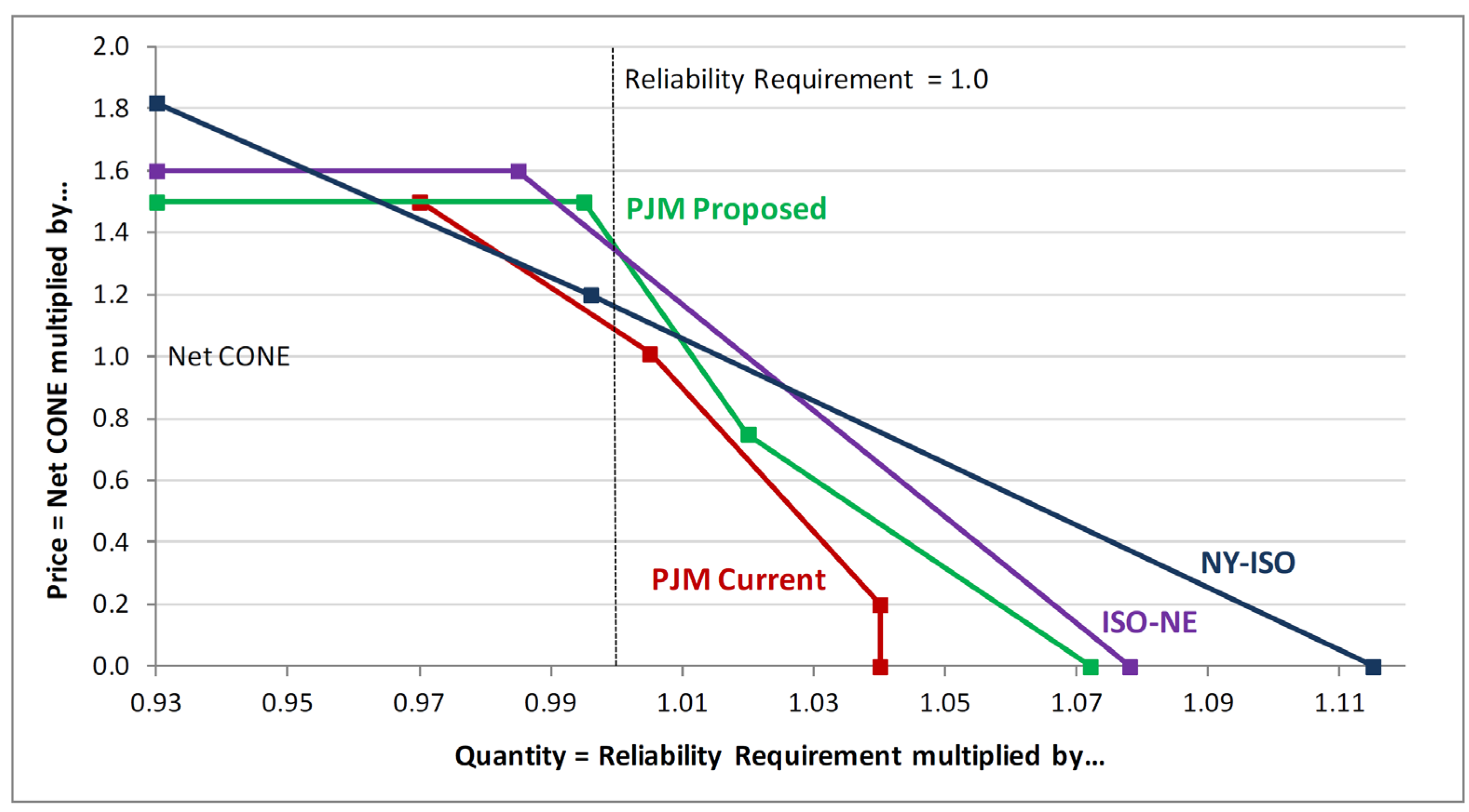

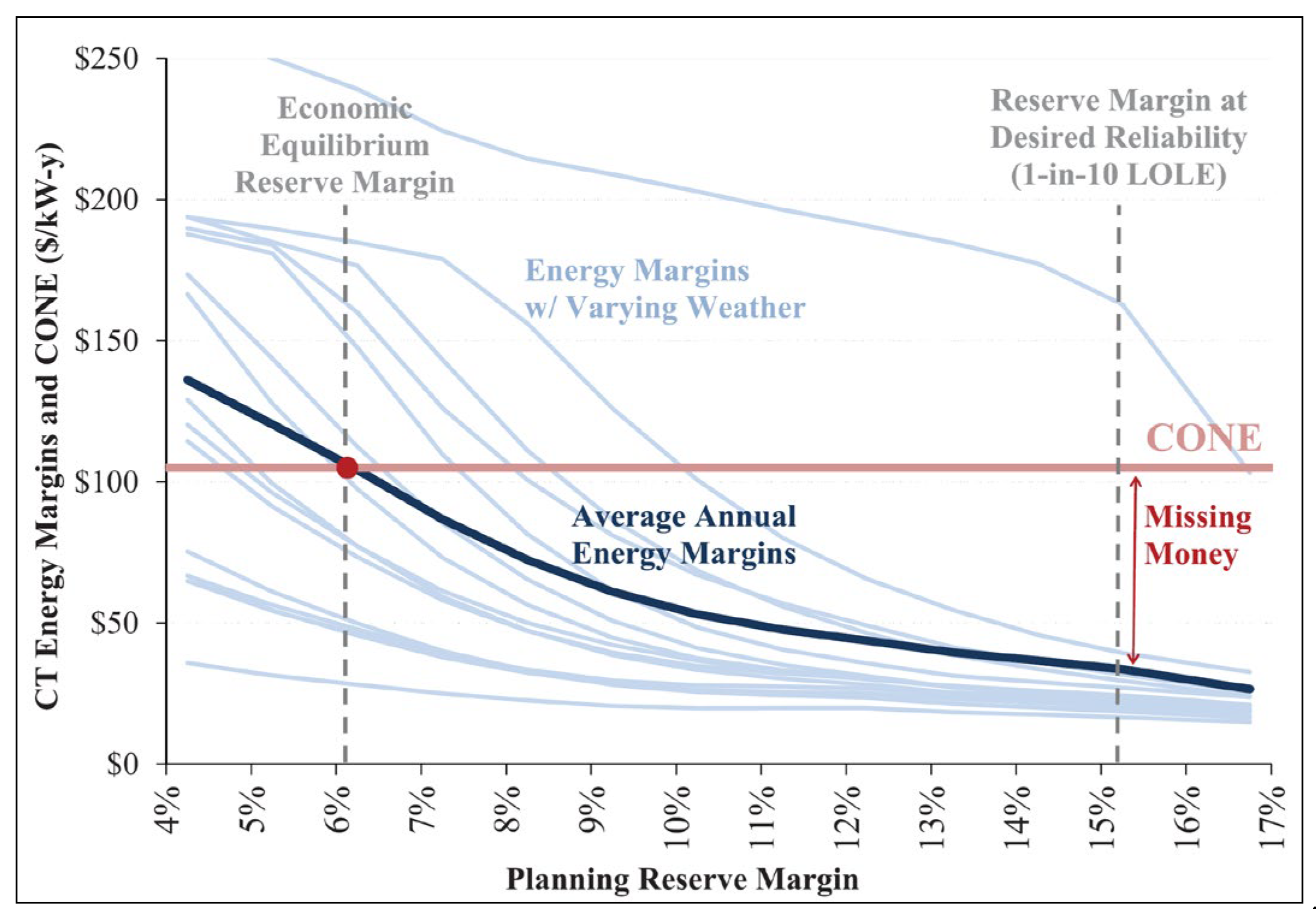

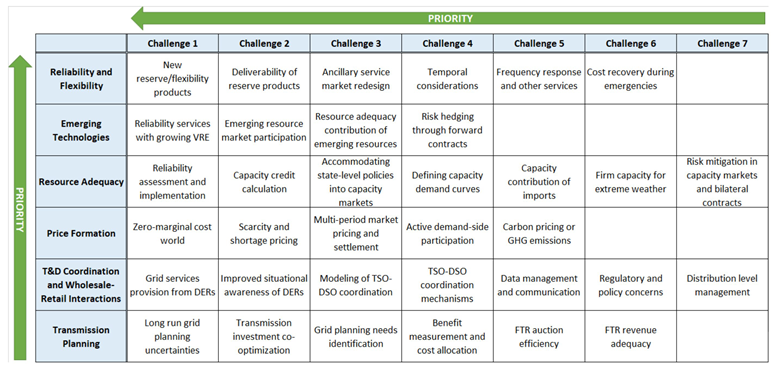

8.3. Market Design

- Market regulations that cap prices below the Value of Lost Load (VoLL), restricting revenue needed to cover fixed costs.

- Overly stringent reliability criteria, leading to excess generation capacity and lower market clearing prices, which can deter new investment.

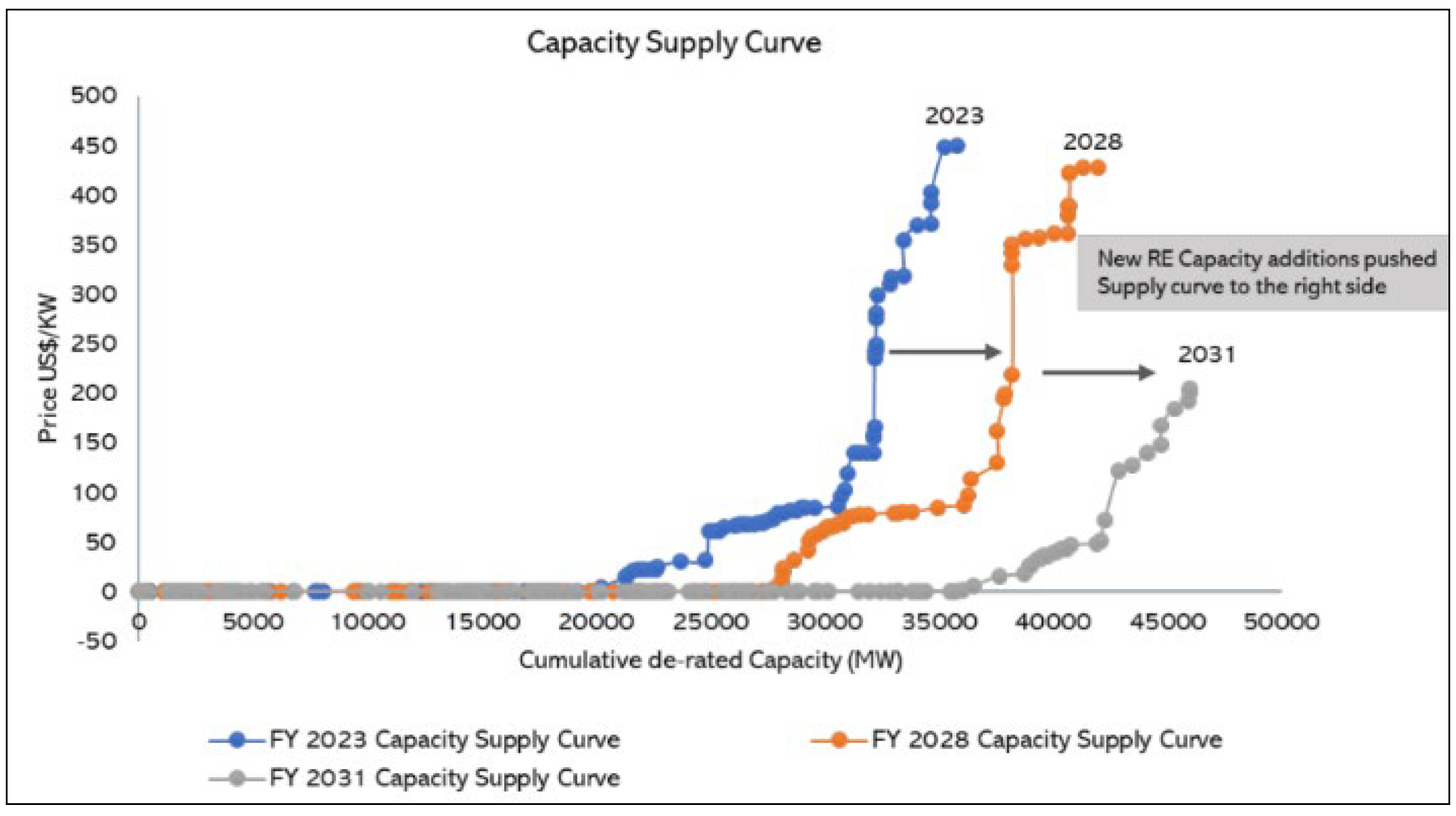

9. Enhancing Integration of Renewables

9.1. Tackling Intermittency

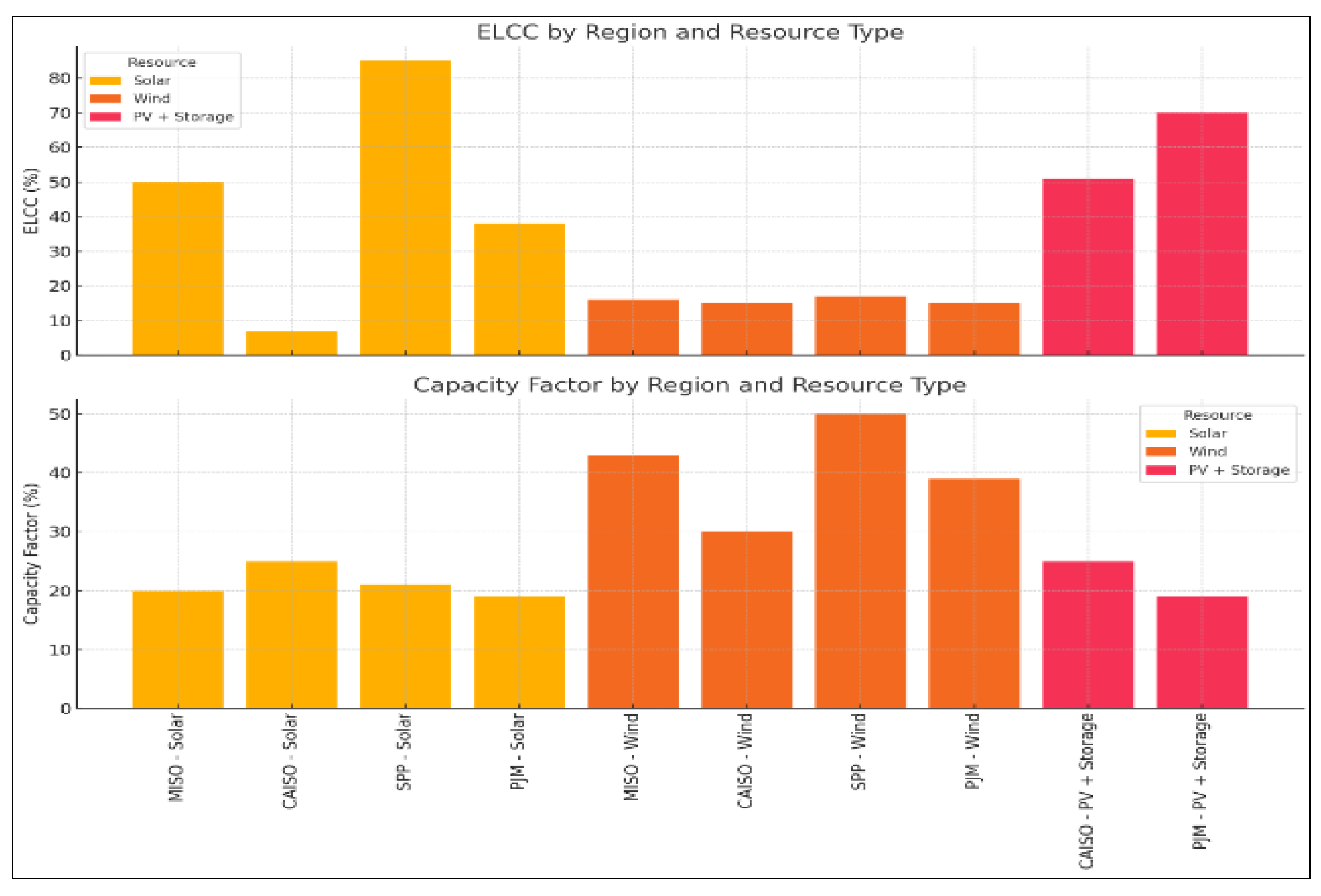

9.2. Improving Capacity Accreditation

9.3. Effective Forecasting

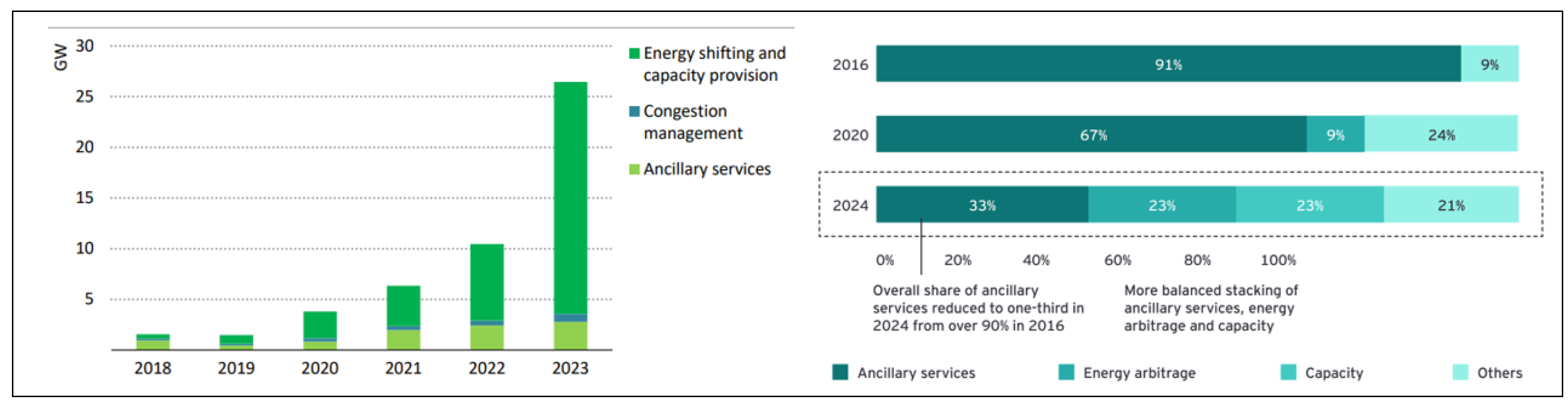

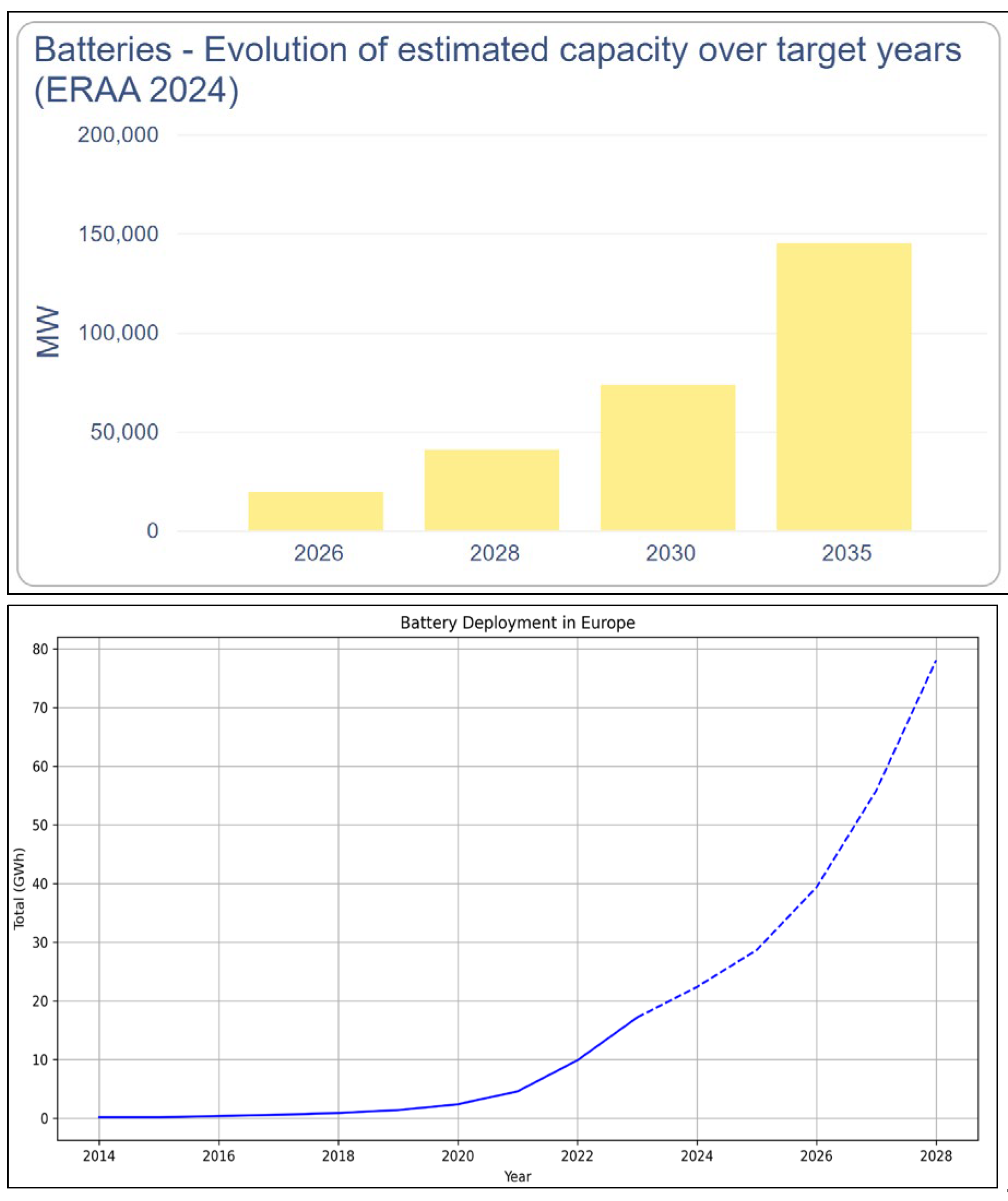

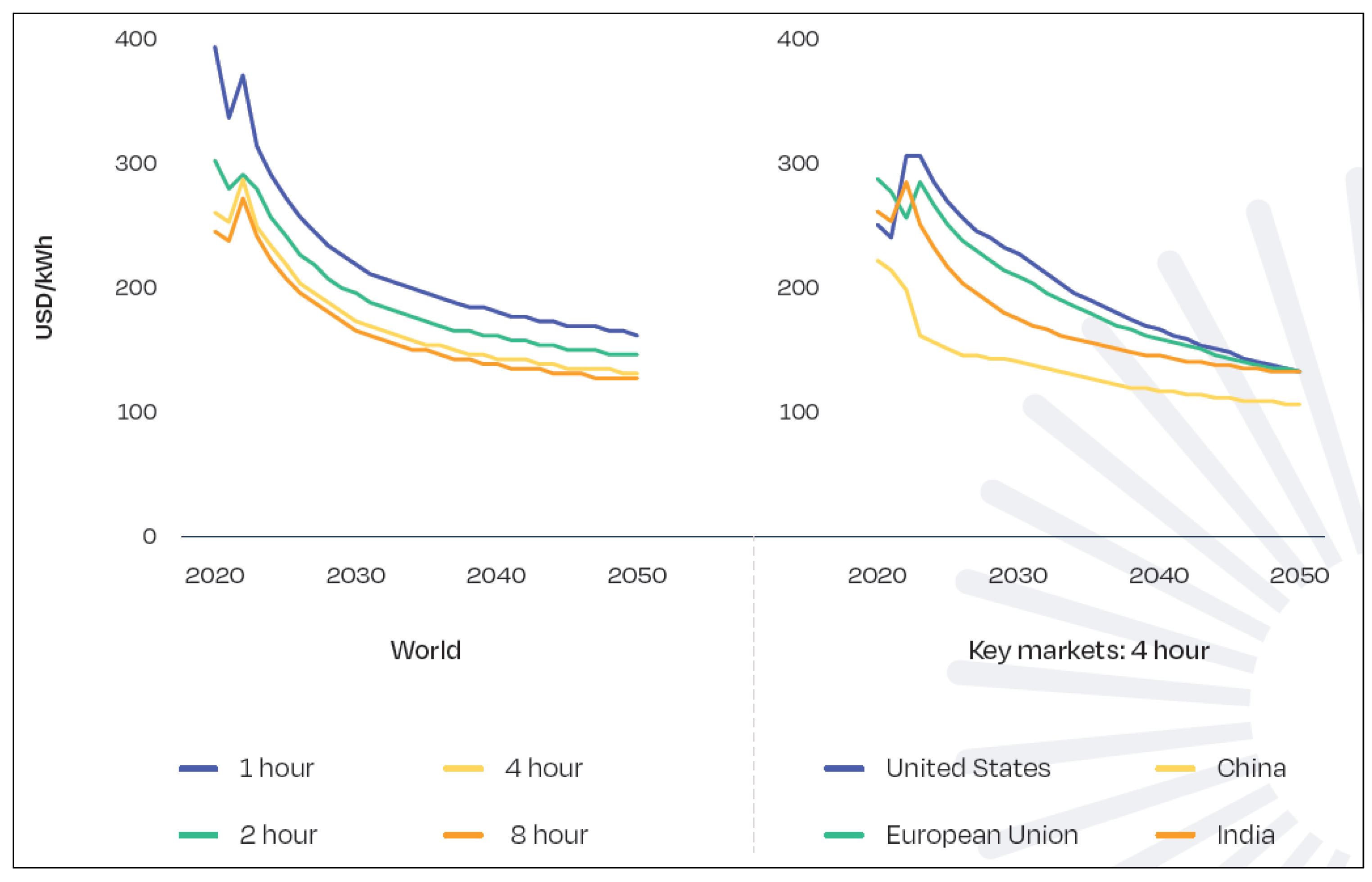

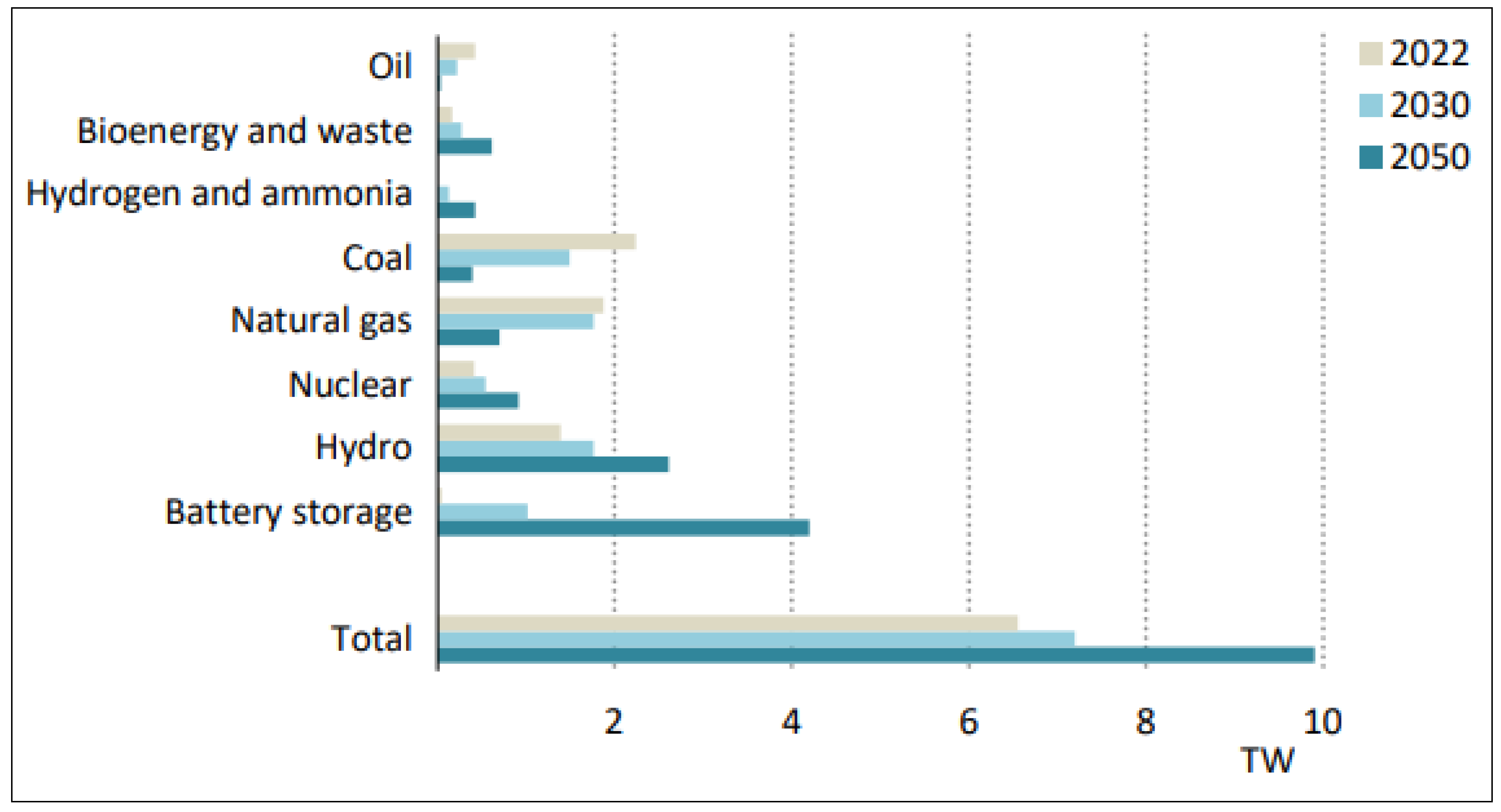

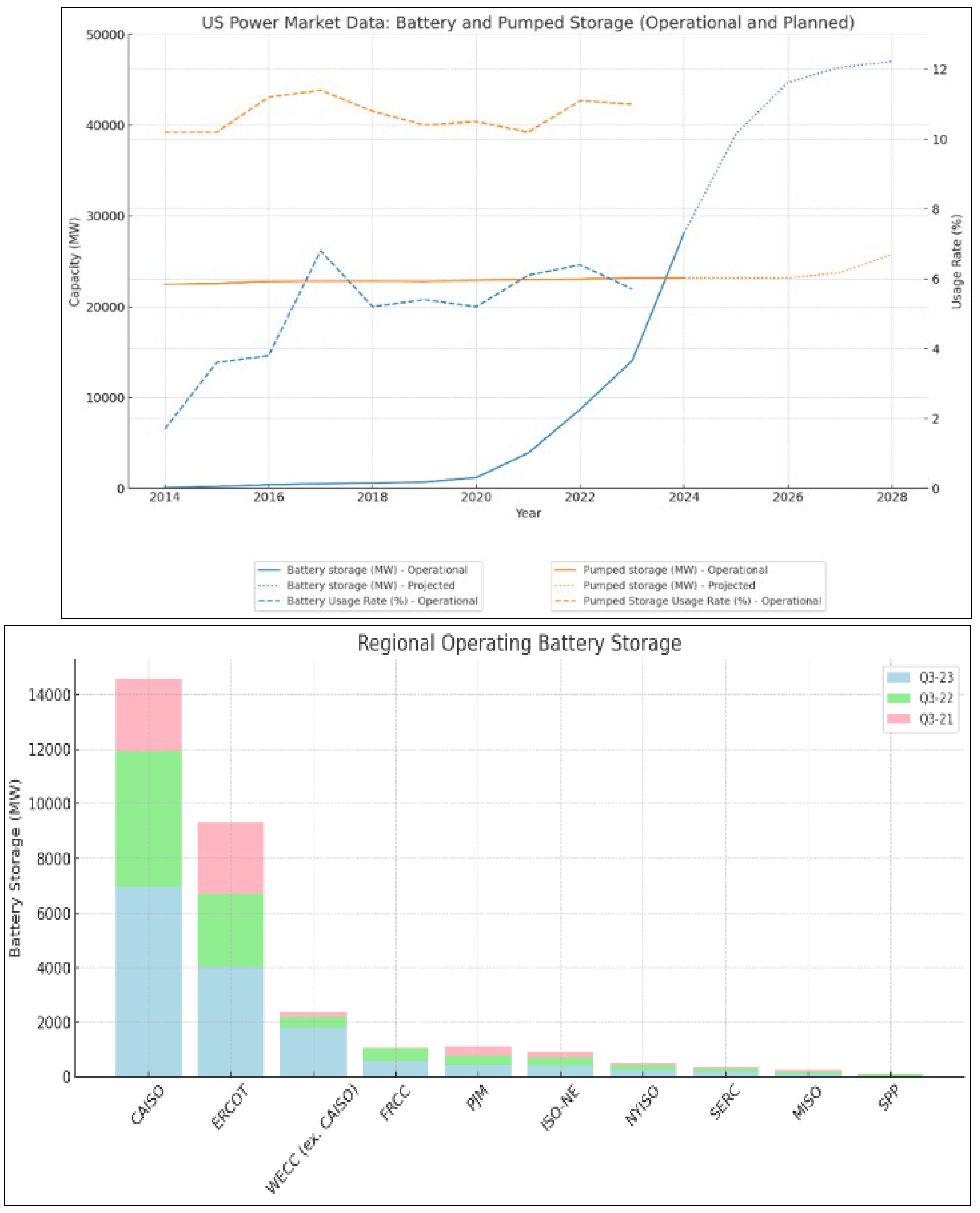

9.4. Battery Storage

- Ancillary services: Includes services such as frequency regulation, voltage control, reactive power support, and reserve capacity.

- Energy arbitrage: Trading electricity for profit from demand price discrepancies.

- Capacity market: Offers guaranteed power availability, boosting grid reliability.

- Others: Includes energy trading, power backup, firming, and ramp control.

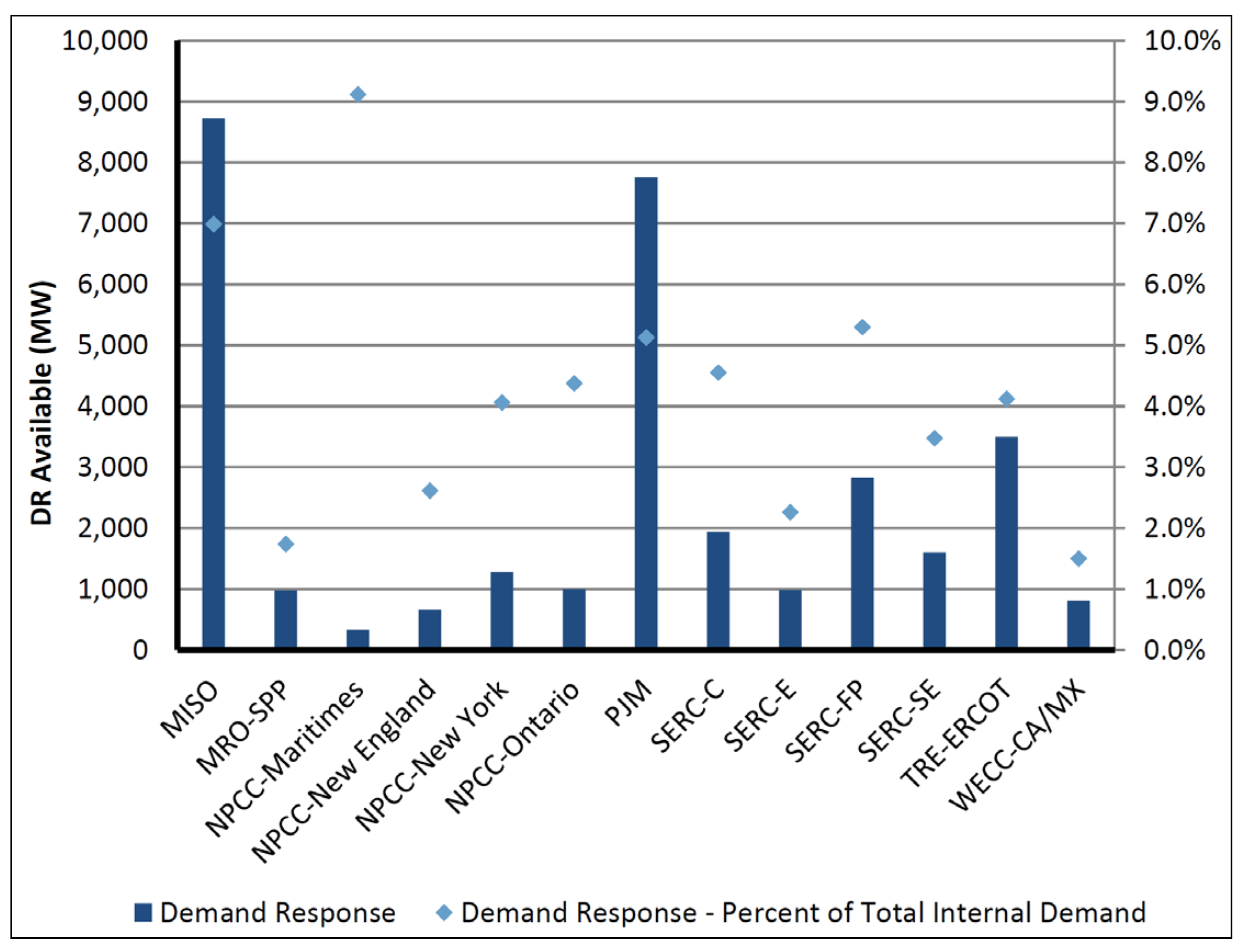

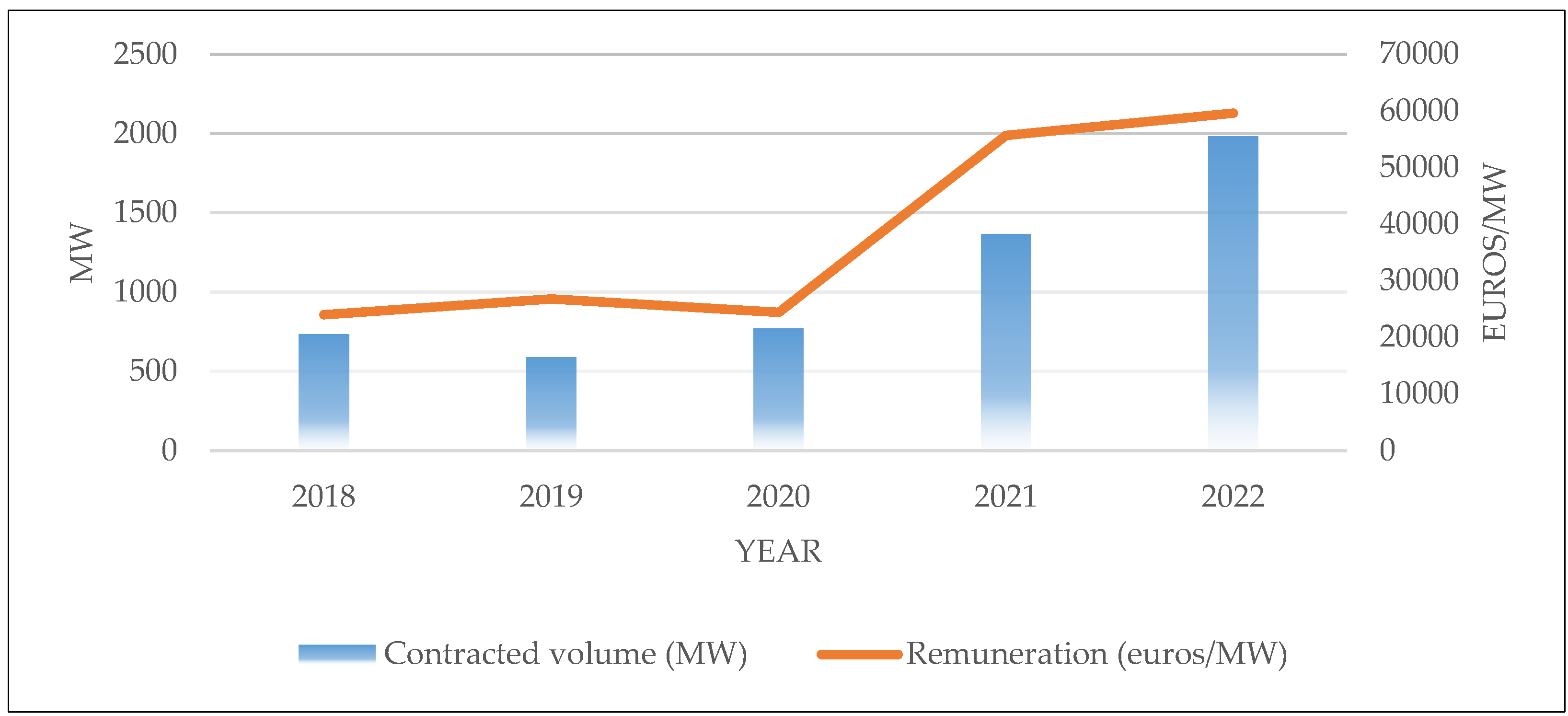

9.5. Demand Response

10. Recommendations

11. Study Limitation and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). Resource Adequacy. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/research/resource-adequacy.html (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Energy Systems Integration Group. Redefining Resource Adequacy for Modern Power Systems. December 2021. p. 1-4. Available online: https://www.esig.energy/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/ESIG-Redefining-Resource-Adequacy-2021-b.pdf. (Accessed July 15, 2024.).

- Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER). European Resource Adequacy Assessment: Executive Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.acer.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/en/Electricity/European_Resource_Adequacy_Assessment/ERAA_2023_Executive_Report.pdf (accessed on July 15 2024).

- Auer, H. Resource Adequacy with Increasing Shares of Wind and Solar Power: A Comparison of European and U.S. Electricity Market Designs. 2018. Available online: https://ceepr.mit.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/2018-008.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Chandler, H. Harnessing Variable Renewables: A Guide to the Balancing Challenge. Paris: International Energy Agency, 2011. Pages 18–19, 33. Available online:https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/2e0cb0c2-d392-4923-b092-ac633531db2b/Harnessing_Variable_Renewables2011.pdf (accessed on July 15 2024).

- Weitemeyer, S., Kleinhans, D., Vogt, T., & Agert, C. “Integration of Renewable Energy Sources in Future Power Systems: The Role of Storage.” Renewable Energy 75 (2015): 14–20. [CrossRef]

- Allard, S., Debusschere, V., Mima, S., Quoc, T. T., Hadjsaid, N., & Criqui, P. “Considering Distribution Grids and Local Flexibilities in the Prospective Development of the European Power System by 2050.” Applied Energy 270 (2020): 114958. [CrossRef]

- Das, P., Mathuria, P., Bhakar, R., Mathur, J., Kanudia, A., & Singh, A. “Flexibility Requirement for Large-Scale Renewable Energy Integration in Indian Power System: Technology, Policy and Modeling Options.” Energy Strategy Reviews 29 (2020): 100482. [CrossRef]

- Suman, S. “Hybrid Nuclear-Renewable Energy Systems: A Review.” Journal of Cleaner Production 181 (2018): 166–177. [CrossRef]

- Batalla-Bejerano, J., & Trujillo-Baute, E. “Impacts of Intermittent Renewable Generation on Electricity System Costs.” Energy Policy 94 (2016): 411–420. [CrossRef]

- Cailliau, M., Ogando, J. A., Egeland, H., Ferreira, R., Feuk, H., Figel, F., et al. Integrating Intermittent Renewable Sources into the EU Electricity System by 2020: Challenges and Solutions. Brussels: Union of the Electricity Industry [EURELECTRIC], 2010. Available online:https://www.eurelectric.org/media/2075/2020_integrating_intermittent_renewable_sources.pdf (accessed on July 15 2024).

- Liebensteiner, M., & Wrienz, M. “Do Intermittent Renewables Threaten the Electricity Supply Security?” Energy Economics 87 (2020): 104499. [CrossRef]

- Vidyanandan, K. V. Grid Integration of Renewables: Challenges and Solutions. P 157–158. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kv-Vidyanandan/publication/363484222_Grid_integration_of_renewables_challenges_and_solutions/links/63a7da44a03100368a282a74/Grid-integration-of-renewables-challenges-and-solutions.pdf.

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Energy, Lise, W., Ansarin, M., De Haas, V., et al. Study on Promoting Energy System Integration through the Increased Role of Renewable Electricity, Decentralised Assets and Hydrogen – Final Report. Publications Office of the European Union, 2024. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2833/560304 (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Hussain, I., and Malik, A. Ensuring Low-Cost Generation and Resource Adequacy: The Case of Pakistan’s New Competitive Trading Bilateral Contract Market (CTBCM) Model. 2023. Available online: https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/EL51-Ensuring-low-cost-generation-and-resource-adequacy.pdf (accessed on July 15 2024).

- National Transmission and Dispatch Company (NTDC). Indicative Generation Capacity Expansion Plan (IGCEP) 2024-34. 2024. Available online: https://nepra.org.pk/Admission%20Notices/2024/05%20May/IGCEP%202024-34%20Report.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Chantzis, Georgios, Effrosyni Giama, Sandro Nižetić, and Agis M. Papadopoulos. "The Potential of Demand Response as a Tool for Decarbonization in the Energy Transition." Energy and Buildings 296 (2023): 113255. P 1-3 . [CrossRef]

- Sun, Yinong and Guo, Nongchao and Frew, Bethany and Anwar, Muhammad Bashar, Impacts of Capacity Remuneration Mechanisms on Generation Investments and Resource Adequacy under Different Weather Conditions (June 26, 2024). P 22 Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4896921 or. [CrossRef]

- Sundar, S., Craig, M.T., Payne, A.E. et al. Meteorological drivers of resource adequacy failures in current and high renewable Western U.S. power systems. Nat Commun 14, 6379 (2023) P 6-11. [CrossRef]

- Ho, Clifford K., Erika L. Roesler, Tu Nguyen, and James Ellison. "Potential Impacts of Climate Change on Renewable Energy and Storage Requirements for Grid Reliability and Resource Adequacy." Journal of Energy Resources Technology 145, no. 10 (2023) P 9-10 . [CrossRef]

- Kozlova, Mariia, Kaisa Huhta, and Alena Lohrmann. "The interface between support schemes for renewable energy and security of supply: Reviewing capacity mechanisms and support schemes for renewable energy in Europe." Energy Policy 181 (2023): 113707. P 8 . [CrossRef]

- Larsen, Erik, and Ann van Ackere. "Importing from? Capacity adequacy in a European context." The Electricity Journal 36, no. 1 (2023): 107236. P 6-7 . [CrossRef]

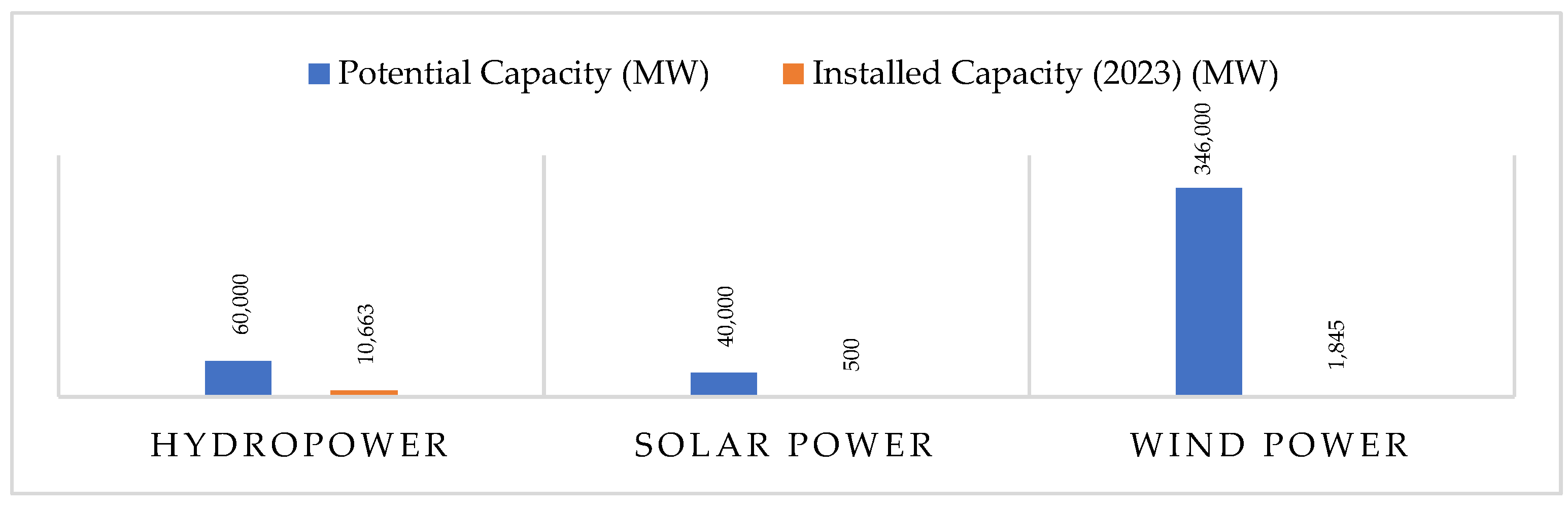

- Xin, Y.; Bin Dost, M.K.; Akram, H.; Watto, W.A. Analyzing Pakistan’s Renewable Energy Potential: A Review of the Country’s Energy Policy, Its Challenges, and Recommendations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16123. p. 15 . [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, S., Buckley, T.: Pakistan’s Power Future: Renewable Energy Pro-vides a More Diverse, Secure and Cost-effective Alternative, Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), Islamabad (2018) P 22-25,34 Available online: https://ieefa.org/resources/pakistans-power-future-renewable-energy-provides-more-diverse-secure-and-cost-effective (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Sadiqa, A., Gulagi, A., Bogdanov, D., Caldera, U., Breyer, C.: Renewable energy in Pakistan: Paving the way towards a fully renewables-based energy system across the power, heat, transport and desalination sectors by 2050. IET Renew. Power Gener. 16, 177–197 (2022). P 186-187 . [CrossRef]

- Yar, Muhammad Asfand, Dr. Aneel Salman, and Dr. Iftikhar Ahmed. "Pakistan’s Alternative and Renewable Energy Policy: Step Towards Energy Security." (2022). P 20, Available online: https://ipripak.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Renewable-Energy-Paper-AS.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Jamal, N. "A Renewable Electricity Supply System in Pakistan by 2050." Europa Universität, 2016. https://www.zhb-flensburg.de/fileadmin/content/spezial-einrichtungen/zhb/dokumente/dissertationen/jamal/phd-thesis.pdf. P-147-151.

- Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER). Methodology for Calculating the Value of Lost Load, the Cost of New Entry and the Reliability Standard. 2020. Available online: https://www.acer.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Individual%20Decisions_annex/ACER%20Decision%2023-2020%20on%20VOLL%20CONE%20RS%20-%20Annex%20I_1.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER). Security of EU Electricity Supply in 2021: Report on Member States Approaches to Assess and Ensure Adequacy. 2021. Available online: https://acer.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Publications/ACER_Security_of_EU_Electricity_Supply_2021.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- PJM Interconnection. Energy and Reserve Price Capping in Other ISOs. 2022. Available online: https://www.pjm.com/-/media/committees-groups/task-forces/epfstf/2022/20220420/20220420-item-04-energy-and-reserve-price-capping-in-other-isos.ashx (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- World Bank. Variable Renewable Energy Integration and Planning Study. 2021. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/884991601929294705/pdf/Variable-Renewable-Energy-Integration-and-Planning-Study.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Zafir, Siti & Muhamad Razali, Noor & Tengku, Juhana. (2016). Relationship between loss of load expectation and reserve margin for optimal generation planning. 2016. Jurnal Teknologi 78 (5-9). [CrossRef]

- Söder, Lennart, Egill Tómasson, Ana Estanqueiro, Damian Flynn, Bri-Mathias Hodge, Juha Kiviluoma, Magnus Korpås, Emmanuel Neau, António Couto, Danny Pudjianto, Goran Strbac, Daniel Burke, Tomás Gómez, Kaushik Das, Nicolaos A. Cutululis, Dirk Van Hertem, Hanspeter Höschle, Julia Matevosyan, Serafin von Roon, Enrico Maria Carlini, Mauro Caprabianca, and Laurens de Vries. “Review of Wind Generation within Adequacy Calculations and Capacity Markets for Different Power Systems.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 119 (2020): 2–3. [CrossRef]

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). Resource Adequacy Requirements: Reliability and Economic Implications. 2014. Available online: https://www.ferc.gov/sites/default/files/2020-05/02-07-14-consultant-report.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA). Grid Code 2023-7. 2023. Available online: https://nepra.org.pk/Legislation/6-Codes/6.2%20The%20Grid%20Code%202023/Grid%20Code%202023.PDF (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA). Market Commercial Code-8: Market Commercial Code (2022). 2022. Available online: https://nepra.org.pk/Legislation/6-Codes/6.5%20Market%20Commercial%20Code/Market%20Commercial%20Code%2003-06-2022.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Saeed, M. Electricity Resource Planning in Pakistan: Correcting the Fundamentals. 2021. Available online: https://www.pakistangulfeconomist.com/2021/07/26/electricity-resource-planning-in-pakistan-correcting-the-fundamentals/ (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Milligan, M.; Frew, B.; Bloom, A.; Clark, K.; Denholm, P.; O'Connell, M.; Levin, T. Capacity Payments in Restructured Markets under Low and High Penetration Levels of Renewable Energy. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy16osti/65491.pdf (accessed on July 15 2024).

- The European Parliament and The Council of the European Union. Electricity Regulation (EU/2019/943) of the European Parliament and of The Council of 5 June 2019 on the Internal Market for Electricity. 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019R0943&from=EN (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- The European Commission. Final Report of the Sector Inquiry on Capacity Mechanisms. 2016. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52016DC0752 (accessed on July 15 2024).

- European Commission. Capacity Mechanisms. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/markets-and-consumers/capacity-mechanisms_en#:~=Capacity%20mechanisms%20are%20temporary%20support,term%20security%20of%20electricity%20supply (accessed on July 15 2024).

- Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER). Security of EU Electricity Supply. Available online: https://acer.europa.eu/media/charts/security-eu-electricity-supply (accessed on July 15, 2024).

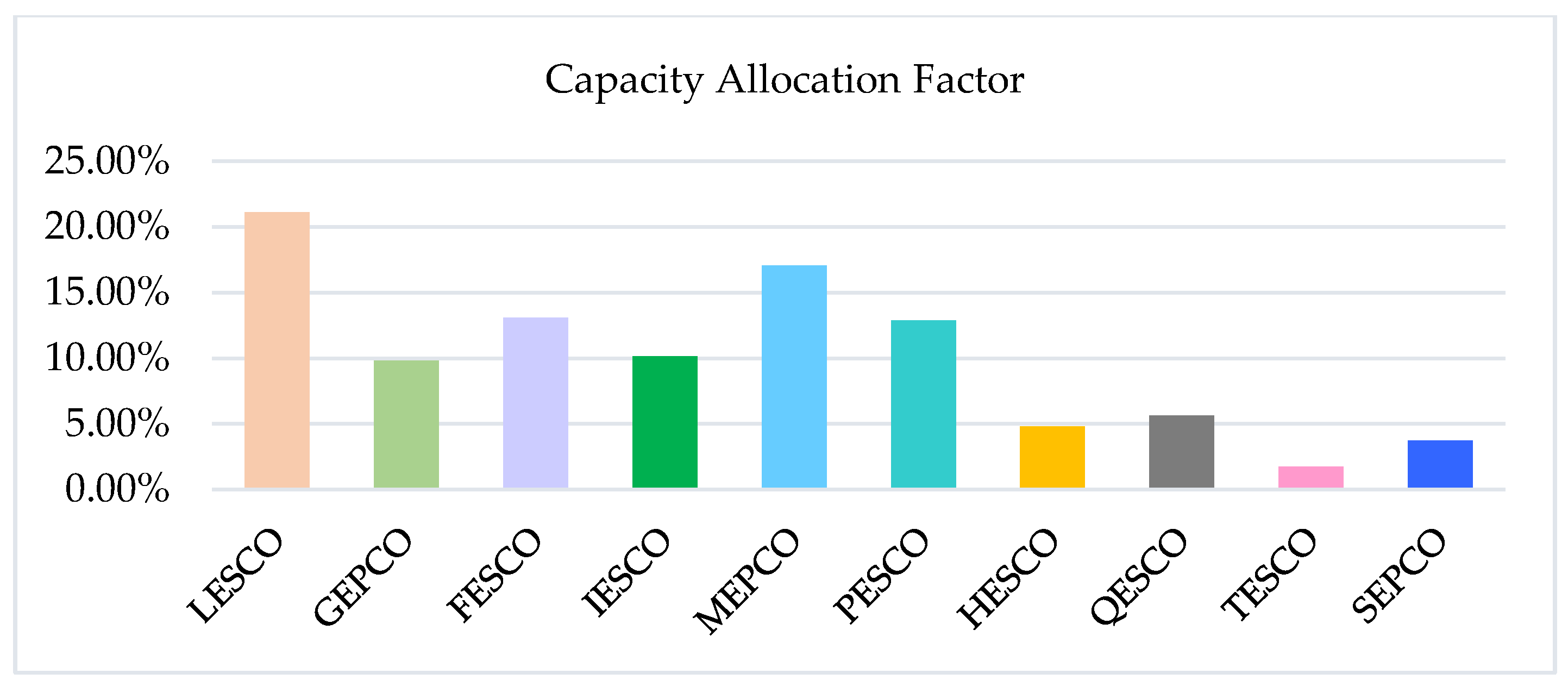

- National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA). State of Industry Report 2023. Available online: https://www.nepra.org.pk/publications/State%20of%20Industry%20Reports/State%20of%20Industry%20Report%202023.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Papandreou, V. Resource Adequacy Framework and Capacity Mechanisms. Available online: https://www.energy-community.org/dam/jcr:0d0e3fb7-4e57-4bd4-9bfa-832ab57105eb/TAIEX_WS_Mr_Vasilis_PAPANDREOU_Resource%20adequacy%20framework%20and%20Capacity%20Mechanisms.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- PACIFIC Exchange Rate Service. Available online: https://fx.sauder.ubc.ca/etc/USDpages.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Riaa Barker Gillette. Alternate Energy and Power 2023. Available online: https://riaabarkergillette.com/pk/assets/uploads/2023/11/2.-Chambers-Alternative-Energy-and-Power-2023.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA). CTBCM Detail Design Report. Available online: https://nepra.org.pk/Admission%20Notices/2020/03%20Mar/Detailed%20Design%20of%20CTBCM.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Asian Development Bank (ADB). TA-9672 PAK: Developing Electricity Market in Pakistan (52323-001) CTBCM Detail Design Report. Available online: https://www.nepra.org.pk/Admission%20Notices/2020/03%20Mar/Detailed%20Design%20of%20CTBCM.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). U.S. Electricity Generation by Major Energy Source, 1950-2019. Available online: https://int.nyt.com/data/documenttools/generation-major-source-1950-2020/ed4a9abd89b178cd/full.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- World Economic Forum. Where does Europe's electricity come from? Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/02/europe-electricity-renewable-energy-transition/ (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- UNFCCC-United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: Adoption of The Paris Agreement - Paris Agreement text English, Paris (2015). Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- USAID. Stages of Renewable Energy Auctions. Available online: https://www.usaid.gov/energy/auctions/stages-of-auctions (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- European Parliament. Renewable Energy: Setting Ambitious Targets for Europe. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20171124STO88813/renewable-energy-setting-ambitious-targets-for-europe (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- European Commission. Commission Proposes Reform of the EU Electricity Market Design to Boost Renewables, Better Protect Consumers and Enhance Industrial Competitiveness. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/api/files/document/print/en/ip_23_1591/IP_23_1591_EN.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- European Commission. The European Green Deal: A Growth Strategy that Protects the Climate. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/stories/european-green-deal/ (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Database of State Incentives for Renewables & Efficiency (DSIRE). Renewable & Clean Energy Standards. November 2022. Available online: https://ncsolarcen-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/RPS-CES-Nov2022.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). Improvements to Generator Interconnection Procedures and Agreements (Issued July 28, 2023). Available online: https://www.ferc.gov/media/order-no-2023 (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). FERC Order No. 2222 Explainer: Facilitating Participation in Electricity Markets by Distributed Energy Resources. Available online: https://www.ferc.gov/ferc-order-no-2222-explainer-facilitating-participation-electricity-markets-distributed-energy (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Government of Pakistan. National Electricity Plan 2023-2027. Available online: https://power.gov.pk/SiteImage/Policy/National%20Electricity%20Plan%202023-27.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Government of Pakistan. Fast Track Solar PV Initiatives 2022. Available online: https://power.gov.pk/SiteImage/Policy/Framework_Guidelines___Fast_Track_Solar_PV_Initiatives_2022.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA). National Electric Power Regulatory Authority Licensing (Microgrid) Regulations, 2022. Available online: https://nepra.org.pk/Legislation/3-Reg/3.29%20NEPRA%20Microgrid%202022%20Regulations/S.R.O%20994%20(I)-2022%20dated%2006-07-2022.PDF (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Form EIA-860, 'Annual Electric Generator Report' and Form EIA-860M, 'Monthly Update to the Annual Electric Generator Report. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/electricity/data/eia860m/ (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Table 4.10. Net Metering Customers and Capacity by Technology Type, by End Use Sector, 2012 through 2022. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/electricity/annual/xls/epa_04_10.xlsx (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). 2023 State of the Markets Report. Available online: https://www.ferc.gov/sites/default/files/2024-03/24_State-of-the-market_0320_1715.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER). ACER Market Monitoring Report-2024. Available online: https://www.acer.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Publications/ACER_2024_MMR_Key_developments_electricity.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Heussaff, C. and G. Zachmann (2024) ‘The changing dynamics of European electricity markets and the supply-demand mismatch risk’, Policy Brief 14/2024, Bruegel. Available online:https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/2024-07/PB%2014%202024_0.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Abbas, Y.; Aslam, R.A. Potential of Untapped Renewable Energy Resources in Pakistan: Current Status and Future Prospects. Eng. Proc. 2023, 56, 108. [CrossRef]

- Aaj News. Punjab to Provide Solar Panels to Consumers Using up to 500 Units of Electricity. Available online: https://english.aaj.tv/news/330368861/punjab-to-provide-solar-panels-to-consumers-using-up-to-500-units-of-electricity (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Private Power and Infrastructure Board (PPIB). Net-Metering. Available online: https://www.ppib.gov.pk/brief-on-net-metering/#:~=As%20of%20June%202023%2C%20the,cumulative%20capacity%20of%201055.03%20MW (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Ernst & Young (EY). RECAI Renewable Energy Country Attractiveness Index November 2018, Issue 52. Available online: https://assets.ey.com/content/dam/ey-sites/ey-com/en_gl/topics/power-and-utilities/ey-recai-52-nov-2018.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Ernst & Young (EY). RECAI Renewable Energy Country Attractiveness Index May 2019, Issue 53. Available online: https://assets.ey.com/content/dam/ey-sites/ey-com/es_mx/topics/power-and-utilities/ey-recai-index-53-scores-ladder.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Ernst & Young (EY). RECAI Renewable Energy Country Attractiveness Index November 2019, Issue 54. Available online: https://assets.ey.com/content/dam/ey-sites/ey-com/en_gl/topics/power-and-utilities/ey-recai-54-nov-2019.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Ember. Electricity Data Explorer. Available online: https://ember-climate.org/data/data-tools/data-explorer/ (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Solar Power Europe. Global Market Outlook for Solar Power 2024. Available online: https://api.solarpowereurope.org/uploads/Global_Market_Outlook_for_Solar_Power_2024_a083b6dcd5.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Millstein, D.; Cappers, P.; Barbose, G.; Bird, L.; Callaway, D.; Elmallah, E.; Golden, M.; Kazachkov, I.; Malin, B.; Matross, R.; Mills, A.; Wang, J. Research Priorities and Opportunities in United States Competitive Wholesale Electricity Markets. National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy21osti/77521.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

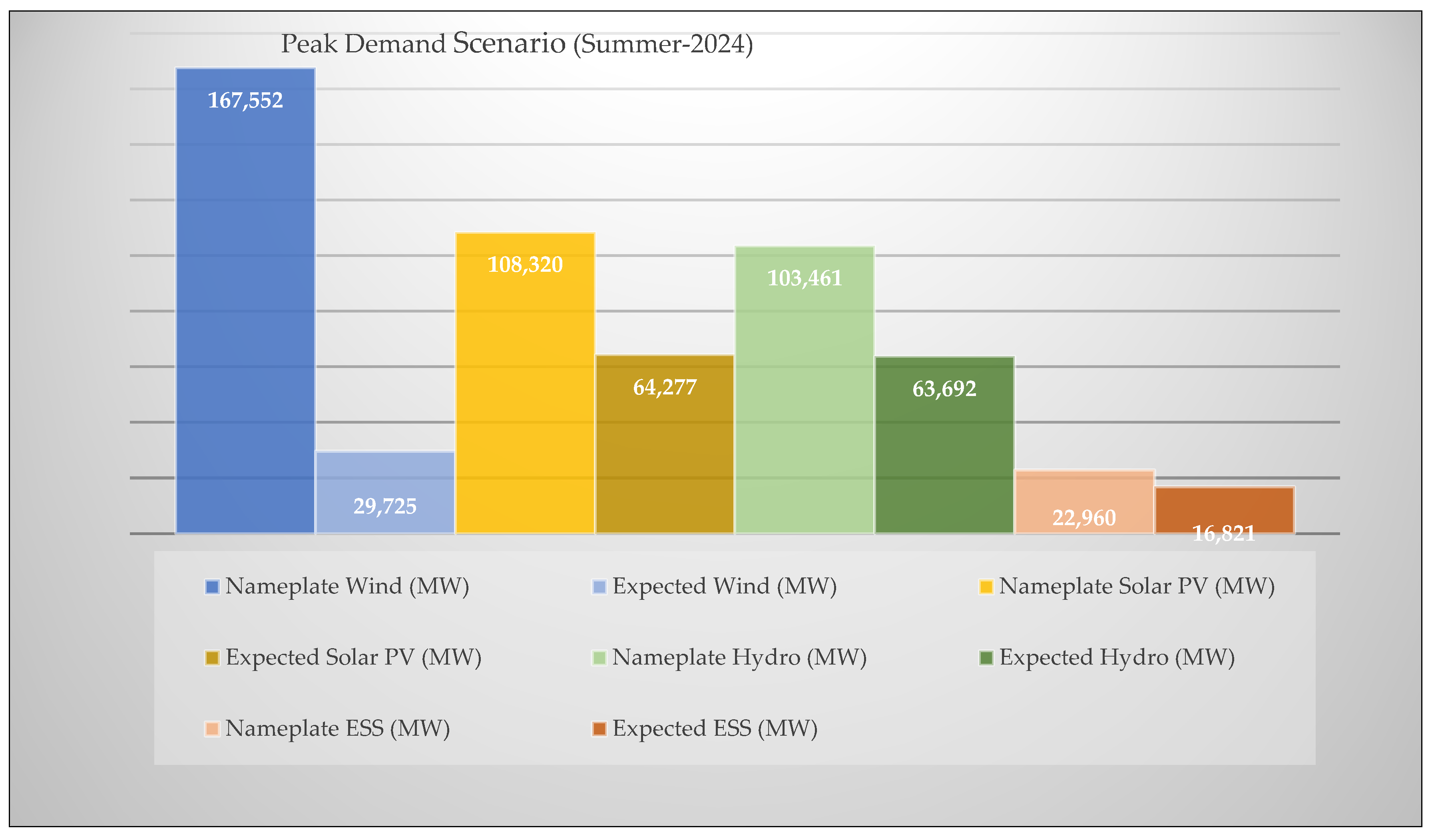

- North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC). 2024 Summer Reliability Assessment. Available online: https://www.nerc.com/pa/RAPA/ra/Reliability%20Assessments%20DL/NERC_SRA_2024.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI). Evaluation of Negative Prices in U.S. Electricity Markets. Available online: https://www.epri.com/research/products/000000003002011828 (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Millstein, D.; O'Shaughnessy, E.; Wiser, R. 2024. Renewables and Wholesale Electricity Prices (ReWEP) Tool. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Version 2024.1. Available online: https://emp.lbl.gov/renewables-and-wholesale-electricity-prices-rewep (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER). Key Developments in EU Electricity Wholesale Markets: 2024 Market Monitoring Report. Available online: https://www.acer.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Publications/ACER_2024_MMR_Key_developments_electricity.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- PJM Interconnection. Reliability in PJM: Today and Tomorrow. Available online: https://www.pjm.com/-/media/library/reports-notices/special-reports/2021/20210311-reliability-in-pjm-today-and-tomorrow.ashx (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- California Independent System Operator (CAISO). What the Duck Curve Tells Us About Managing a Green Grid. Available online: https://www.caiso.com/Documents/FlexibleResourcesHelpRenewables_FastFacts.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Millstein, D.; O'Shaughnessy, E.; Wiser, R. Exploring Wholesale Energy Price Trends, The Renewables and Wholesale Electricity Prices (ReWEP) Tool, Version 2024.1. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Available online: https://live-etabiblio.pantheonsite.io/sites/default/files/rewep-2024update_tech-brief_20240429.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). As Solar Capacity Grows, Duck Curves Are Getting Deeper in California. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=56880# (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER). Demand Response and Other Distributed Energy Resources: What Barriers Are Holding Them Back? 2023 ACER Market Monitoring Report. Available online: https://www.acer.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/en/The_agency/Documents/Presentation_TTE_Council_lunch_Barriers_to_DR.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Philippe Vassilopoulos & Elies Lahmar, 2022. "The Trading of Electricity," Springer Books, in: Manfred Hafner & Giacomo Luciani (ed.), The Palgrave Handbook of International Energy Economics, chapter 0, pages 407-437, Springer. Available online: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/978-3-030-86884-0.pdf.

- SPEES, KATHLEEN, SAMUEL A. NEWELL, and JOHANNES P. PFEIFENBERGER. “Capacity Markets—Lessons Learned from the First Decade.” Economics of Energy & Environmental Policy 2, no. 2 (2013): 1–26. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26189454.

- European Commission. Identification of Appropriate Generation and System Adequacy Standards for the Internal Electricity Market. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2016-07/Generation%2520adequacy%2520Final%2520Report_for%2520publication_0.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Energy Systems Integration Group. Ensuring Efficient Reliability: New Design Principles for Capacity Accreditation. A Report of the Redefining Resource Adequacy Task Force. Reston, VA. 2023. Available online: https://www.esig.energy/new-design-principles-for-capacity-accreditation (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- European Environment Agency (EEA) and Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER). Flexibility Solutions to Support a Decarbonized and Secure EU Electricity System. Available online: https://www.acer.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Publications/EEA-ACER_Flexibility_solutions_support_decarbonised_secure_EU_electricity_system.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- PJM Interconnection. Periodic Review of Default CONE and ACR Values. Available online: https://www.pjm.com/-/media/committees-groups/committees/mic/2022/20221006/item-13a---periodic-review-of-default-cone-and-acr-values.ashx (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Lazard. Lazard’s Levelized Cost. Available online: https://www.lazard.com/media/2ozoovyg/lazards-lcoeplus-april-2023.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- García-Navarro, J.; Dominguez, I.; Brutti, S.; Afanasyev, V.; & Jossen, A. The Critical Role of Electricity Storage for a Clean and Renewable European Economy. Energy & Environmental Science. 2023. Available online: https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2023/ee/d3ee02768f (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Solar Power Europe. European Market Outlook for Battery Storage 2024-2028. Available online: https://www.solarpowereurope.org/insights/thematic-reports/european-market-outlook-for-battery-storage-2024-2028 (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Batteries and Secure Energy Transitions. Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/cb39c1bf-d2b3-446d-8c35-aae6b1f3a4a0/BatteriesandSecureEnergyTransitions.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- EY. Four Factors to Guide Investment in Battery Storage. Available online: https://www.ey.com/en_uk/recai/four-factors-to-guide-investment-in-battery-storage (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- S&P Global. Capacity Surpasses 14.6 GW in Q3, 3.5 GW Planned in Q4. Available online: https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/electric-power/111423-us-battery-storage-capacity-surpasses-146-gw-in-q3-35-gw-planned-in-q4 (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. Annual Energy Outlook 2023 (AEO2023). Available online: https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/ (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- European Commission. Commission Recommendation of 14 March 2023 on Energy Storage – Underpinning a decarbonized and secure EU energy system 2023/C 103/01. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32023H0320(01) (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- European Commission. Energy storage. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/research-and-technology/energy-storage_en#eu-initiatives-on-batteries (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- EASE. EMMES 8.0 - March 2024. Available online: https://ease-storage.eu/publication/emmes-8-0-march-2024/ (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- ACER. Explore the Datasets Behind the European Resource Adequacy Assessment. Available online: https://acer.europa.eu/media/charts/explore-datasets-behind-european-resource-adequacy-assessment (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Dawn. A Case for Solar with Battery Storage. Available online: https://www.dawn.com/news/1782973 (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- Dawn. Batteries with Renewables Can Cut Power Costs: Study. Available online: https://www.dawn.com/news/1832126 (accessed on July 15, 2024).

- ENTSO-E. Network Code on Demand Response. Available online: https://eepublicdownloads.blob.core.windows.net/public-cdn-container/clean-documents/Network%20codes%20documents/NC%20DR/NCDR_DSO%20ENTITY_ENTSO-E.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2024).

| Capacity Remuneration Mechanism (CRM) | Country |

| Capacity Market | Bulgaria, France, Greece, Ireland, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Slovakia, Belgium |

| Strategic Reserve | Croatia, Finland, Germany, Netherlands, Lithuania |

| No CRM | Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, Luxembourg |

| Mostly countries in EU have a unified auction for both new and existing capacities, but differentiating through contract lengths i.e., 15 years for new capacity and 1 years for existing capacity generation. | |

| Type | State | Year | Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Renewable Portfolio Standard | Delaware | 2026 | 25% |

| Connecticut | 2030 | 40% | |

| 2040 | 100% | ||

| New Jersey | 2030 | 50% | |

| 2050 | 100% | ||

| Maryland | 2030 | 50% | |

| Illinois | 2040 | 50% | |

| Washington, D.C. | 2032 | 100% | |

| Rhode Island | 2033 | 100% | |

| Virginia | 2045 | 100% | |

| Massachusetts | 2030 | 40% | |

| 2050 | 80% | ||

| Clean Energy Standard | New York | 2030 | 70% |

| 2040 | 100% | ||

| Oregon | 2040 | 50% | |

| California | 2030 | 60% | |

| 2045 | 100% | ||

| New Mexico | 2040 | 80% | |

| 2045 | 100% | ||

| Washington | 2045 | 100% | |

| Clean Energy Goal | Colorado | 2050 | 100% |

| Nevada | 2030 | 50% | |

| 2050 | 100% | ||

| Wisconsin | 2050 | 100% |

| SCENARIO | TOTAL COSTS (w/o Emission Costs) (NPV) bn USD |

TOTAL COSTS (with Emission Costs) (NPV) bn USD |

Total Emissions (2019 - 2040) Gt CO2 |

Wind Share (2025, %) | Solar Share (2025, %) | Wind Share (2030, %) | Solar Share (2030, %) | Rank (VRE Share-2025) | RANK (Average Cost w/o Emission Costs) | RANK (Emissions) |

| PLEXOS Optimum | 84.3 | 106.5 | 1,184.5 | 10.0 | 17.3 | 7.7 | 25.3 | 8 | 7 | 10 |

| Government RE Policy Targets | +0.6% | +3.3% | +20.6% | 8.8 | 11.2 | 9 | 21 | 17 | 8 | 16 |

| Low Demand | -11.9% | -11.8% | -18.0% | 9.2 | 13.9 | 7.2 | 24.1 | 14 | 2 | 3 |

| Nuclear Flexible | 0.0% | -0.1% | -0.5% | 9.9 | 18.0 | 7.8 | 25.4 | 5 | 6 | 9 |

| Delays Hydropower | +6.3% | +8.3% | +17.6% | 9.5 | 21.9 | 11.5 | 28.8 | 2 | 16 | 14 |

| Distributed PV | +2.5% | +3.5% | +8.2% | 10.6 | 9.5 | 10.9 | 16.8 | 16 | 12 | 12 |

| Battery | -0.4% | -1.9% | -11.2% | 9.8 | 19.6 | 10.8 | 26.0 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1= Best 18=Worst | ||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).