1. Introduction

The role of local communities in conservation has gained significant recognition globally due to its potential to ensure the sustainability of natural resources. In Europe, community-based conservation efforts have proven successful in various contexts. For instance, in the European Union, initiatives such as the Natura 2000 network emphasize the involvement of local populations in managing protected areas, leading to improved biodiversity outcomes [

1]. The European approach underscores the necessity of integrating local knowledge and ensuring that conservation policies are socially acceptable to achieve long-term ecological goals.

In Asia, community participation in conservation has also been highlighted as critical. The success of community-managed forests in Nepal exemplifies how local stewardship can enhance forest health and biodiversity. Studies have shown that community forestry in Nepal not only improves forest conditions but also contributes to poverty reduction and social equity [

2]. Similar trends are observed in India, where Joint Forest Management (JFM) programs have engaged local communities in forest governance, leading to better forest conservation outcomes and increased livelihood benefits for participants [

3].

The Caribbean region presents another perspective on the importance of local involvement in conservation. In countries like Jamaica and Belize, community-based marine protected areas have been established, demonstrating that local communities can play a pivotal role in managing and protecting marine resources. These initiatives have led to significant improvements in coral reef health and fish populations, indicating the effectiveness of community-led conservation efforts [

4].

Australia’s approach to conservation also underscores the value of community engagement. Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs) managed by Aboriginal communities have shown success in preserving biodiversity while also promoting cultural heritage and traditional knowledge. The integration of indigenous management practices with contemporary conservation science has proven beneficial for both ecological and social outcomes [

5].

In Africa, the paradigm of community-based conservation has been extensively promoted as a means to align the interests of local communities with conservation goals. Community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) programs, particularly in Southern Africa, have demonstrated the potential to reconcile biodiversity conservation with rural development. Countries like Namibia and Botswana have implemented successful CBNRM initiatives that provide local communities with the rights and responsibilities to manage wildlife and other natural resources, resulting in tangible benefits for both conservation and local livelihoods [

6]

In East Africa, Kenya’s conservancies provide another model of community involvement in conservation. These conservancies are community-owned and managed areas that support wildlife conservation while also providing economic benefits through tourism and sustainable resource use. The Maasai Mara conservancies, for instance, have enhanced wildlife protection and contributed to poverty alleviation among local communities [

7]

Zimbabwe has a rich history of community involvement in conservation, most notably through the Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE). Launched in the 1980s, CAMPFIRE was designed to give rural communities the authority to manage wildlife resources and benefit economically from sustainable use. The program aimed to incentivize local communities to conserve wildlife by providing them with revenue from activities such as trophy hunting and tourism [

8]. Despite its initial success, CAMPFIRE has faced challenges over the years, including political instability, economic difficulties, and issues related to governance and benefit distribution. These challenges have impacted the effectiveness of the program, highlighting the need for adaptive management and stronger community engagement [

9].

The Save Valley Conservancy (SVC), located in the southeast Lowveld of Zimbabwe, is one of the largest private wildlife reserves in Africa. Established in the early 1990s, the conservancy is home to a diverse array of wildlife, including the Big Five (elephant, lion, leopard, buffalo, and rhinoceros) as well as numerous other species [

10,

14]. SVC was created through the amalgamation of several large cattle ranches, with the goal of promoting wildlife conservation and sustainable land use. The conservancy has been managed by a coalition of private landowners who converted their properties from cattle ranching to wildlife conservation, recognizing the potential for ecotourism and trophy hunting as alternative revenue streams [

11].

However, the establishment and operation of the SVC have not been without controversy. One of the significant challenges has been the relationship between the conservancy and the surrounding local communities. Many communities living adjacent to the SVC rely on natural resources for their livelihoods and have historically had limited involvement in the management and benefits of the conservancy. This has led to tensions and conflicts over issues such as land use, access to resources, and benefit-sharing [

12]

Recent efforts to address these challenges have focused on increasing community involvement in the management of the SVC. This includes initiatives to engage local communities in decision-making processes, provide them with economic benefits from conservation activities, and incorporate their traditional knowledge and practices into conservation strategies. These efforts aim to create a more inclusive and sustainable model of conservation that benefits both biodiversity and local livelihoods [

13]

1.1. The Role of Focus Group Discussions in Eliciting Community Views

Focus group discussions (FGDs) are a qualitative research method that can be highly effective in eliciting views from local communities. FGDs involve guided discussions with a small group of participants, allowing for in-depth exploration of their perspectives, experiences, and attitudes. This method is particularly useful in understanding the social dynamics, cultural values, and local knowledge that influence community interactions with conservation initiatives [

15]

In the context of the SVC, FGDs can provide valuable insights into the views and concerns of local communities regarding conservation management. By engaging community members in structured discussions, researchers and conservancy managers can gain a better understanding of the social and economic factors that impact conservation efforts. This information can then be used to develop more effective and equitable management strategies that address the needs and priorities of both the conservancy and the local communities [

16].

The Save Valley Conservancy represents a significant case study for examining the role of local community involvement in conservation. By employing FGDs as a tool to gather community views, this research aims to contribute to the development of more inclusive and sustainable conservation practices. This paper will detail the methodology used in conducting FGDs, present the results of the discussions, and explore the implications for decision-making in the management of the SVC.

1.2. Problem Statement

The Save Valley Conservancy (SVC) in Zimbabwe, despite its success in integrating private investment and community engagement for wildlife conservation, faces significant challenges that threaten its sustainability and effectiveness. Persistent land tenure conflicts create uncertainty and hinder long-term planning, while human-wildlife conflict exacerbates tensions between conservation objectives and local livelihoods. Furthermore, ensuring sustainable financing and fostering inclusive, equitable governance models remain critical hurdles. These issues complicate the implementation of adaptive management practices and community-based conservation initiatives. Addressing these challenges is essential to enhance the resilience and sustainability of the SVC, ensuring that conservation efforts lead to long-term ecological benefits and equitable socio-economic outcomes for all stakeholders involved in the region’s wildlife management initiatives. A comprehensive approach is needed to resolve these problems, integrating legal, financial, and community-focused strategies to strengthen conservation governance in the SVC.

1.3. Objectives of the Study

The main goals of this research are:

To assess the effectiveness of focus group discussions (FGDs) as a method for eliciting the views and opinions of local communities surrounding the Save Valley Conservancy.

To identify the key concerns, priorities, and suggestions of local communities regarding the management and conservation practices within the Save Valley Conservancy.

To explore the potential benefits of incorporating community views into the decision-making processes of the conservancy.

To develop recommendations for enhancing community involvement in conservation management, thereby promoting sustainable and inclusive practices.

1.4. Significance of the Study

The significance of this study lies in its potential to contribute to more effective and equitable conservation management within the Save Valley Conservancy. For stakeholders, including conservancy managers, local communities, policymakers, and conservation organizations, the findings can provide valuable insights into the benefits of community engagement. By highlighting the perspectives and needs of local communities, this research can help in developing more inclusive and sustainable management strategies that align with both conservation goals and community well-being. Studies have shown that incorporating local knowledge and ensuring community participation leads to better compliance and more resilient conservation outcomes [

17]. Additionally, community-based approaches can enhance the legitimacy and acceptance of conservation policies, reducing conflicts and fostering a sense of ownership among local populations [

18]

Furthermore, this study can serve as a model for other conservation areas facing similar challenges, demonstrating the importance of incorporating local voices into conservation decision-making processes. The broader implications of this research emphasize the critical role of participatory approaches in achieving long-term conservation success and social equity. Engaging communities in conservation not only supports biodiversity but also promotes sustainable livelihoods, thus addressing both environmental and socio-economic objectives [

19].

1.5. Community Participation in Conservation

Community participation in conservation has been widely recognized as essential for the sustainable management of natural resources. Engaging local communities in conservation efforts ensures that conservation strategies are culturally appropriate and socially accepted, leading to better compliance and more effective outcomes [

20]. This approach aligns with the principles of participatory conservation, which advocate for the inclusion of local stakeholders in decision-making processes to leverage their traditional knowledge and foster a sense of ownership over conservation initiatives.

In Europe, community participation in conservation has been emphasized through initiatives like the Natura 2000 network, which integrates local populations in the management of protected areas [

21]. The involvement of local communities has been shown to enhance biodiversity conservation and improve the sustainability of conservation efforts. Similarly, in Asia, community-based forestry in Nepal has demonstrated the benefits of local stewardship, leading to improved forest health and increased socio-economic benefits for the communities involved [

22,

23].

The Caribbean provides another perspective on community involvement, where community-based marine protected areas in countries like Jamaica and Belize have led to significant improvements in coral reef health and fish populations [

24,

25]. These examples illustrate the effectiveness of community-led conservation initiatives in achieving ecological and socio-economic goals. In Australia, Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs) managed by Aboriginal communities have shown success in preserving biodiversity while promoting cultural heritage [

26]. The integration of indigenous knowledge with contemporary conservation practices has proven beneficial for both ecological and social outcomes, highlighting the importance of community involvement in conservation.

Africa’s experience with community-based conservation, particularly in Southern Africa, underscores the potential for aligning conservation goals with local development. Community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) programs in Namibia and Botswana have successfully provided local communities with the rights and responsibilities to manage wildlife and other natural resources, resulting in tangible benefits for conservation and local livelihoods [

27]. In East Africa, Kenya’s community conservancies have demonstrated the effectiveness of local management in wildlife protection and poverty alleviation [

28].

In Zimbabwe, the Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE) represents a notable example of community-based conservation. Despite facing challenges over the years, CAMPFIRE initially demonstrated the potential for local communities to benefit economically from wildlife management, thereby incentivizing conservation [

29]. This highlights the importance of adaptive management and continuous community engagement to sustain conservation efforts.

1.6. Focus Group Discussions (FGDs)

Focus group discussions (FGDs) are a qualitative research method used to gather in-depth insights from a small group of participants. FGDs involve guided discussions on specific topics, allowing researchers to explore participants’ perspectives, experiences, and attitudes (Krueger & Casey, 2020) [

30]. This method is particularly valuable in understanding the social dynamics, cultural values, and local knowledge that influence community interactions with conservation initiatives. FGDs are effective in eliciting rich, detailed information that might not emerge through other research methods such as surveys or individual interviews. They provide a platform for participants to express their views openly and interact with each other, leading to a deeper understanding of the issues being discussed (Morgan, 2020). The group setting encourages participants to build on each other’s responses, generating a more comprehensive picture of community perspectives. In the context of conservation, FGDs can be instrumental in identifying the concerns, priorities, and suggestions of local communities. By facilitating structured discussions, researchers can gain valuable insights into the factors that influence community support or opposition to conservation initiatives. This information can then be used to develop more effective and inclusive conservation strategies that address the needs and priorities of local communities [

31].

Moreover, FGDs can help bridge the gap between conservation managers and local communities by providing a forum for dialogue and mutual understanding. This participatory approach fosters trust and collaboration, which are crucial for the success of conservation efforts [

32]. The iterative nature of FGDs also allows for continuous feedback and adaptation of conservation strategies based on community input.

1.7. Case Studies

Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of using FGDs for community engagement in conservation. In Zambia, FGDs were used to assess the perceptions and attitudes of local communities towards wildlife conservation and anti-poaching efforts. The findings revealed that community support for conservation was influenced by the perceived benefits and costs of living near protected areas [

33]. This information was used to inform policies that aimed to enhance the benefits of conservation for local communities, thereby increasing their support for anti-poaching initiatives.

In Nepal, FGDs were conducted with local communities to understand their views on community forestry and its impact on their livelihoods. The discussions highlighted the importance of forest resources for local livelihoods and the need for equitable benefit-sharing mechanisms [

34]. The insights gained from the FGDs informed the development of community forestry policies that better addressed the needs and priorities of local communities.

In the Caribbean, FGDs were used to engage local fishers in the management of marine protected areas. The discussions provided valuable insights into the fishers’ knowledge of marine ecosystems and their views on conservation regulations [

35]. This participatory approach helped to build trust between the fishers and conservation managers, leading to more effective and sustainable management of marine resources.

In Australia, FGDs with Aboriginal communities were used to explore their perspectives on the management of Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs). The discussions highlighted the importance of integrating traditional knowledge and cultural practices into conservation management [

38]. The findings from the FGDs informed the development of management plans that respected and incorporated Aboriginal knowledge and practices.

In Kenya, FGDs were used to engage local communities in the management of community conservancies. The discussions provided insights into the challenges and opportunities faced by the conservancies and the factors that influenced community support for conservation [

39]. The information gained from the FGDs was used to develop strategies to enhance community involvement and support for the conservancies. These case studies illustrate the value of FGDs as a tool for eliciting community views and informing conservation management. By providing a platform for dialogue and mutual understanding, FGDs can help to build trust and collaboration between conservation managers and local communities. The insights gained from FGDs can be used to develop more effective and inclusive conservation strategies that address the needs and priorities of local communities, thereby enhancing the sustainability and success of conservation efforts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

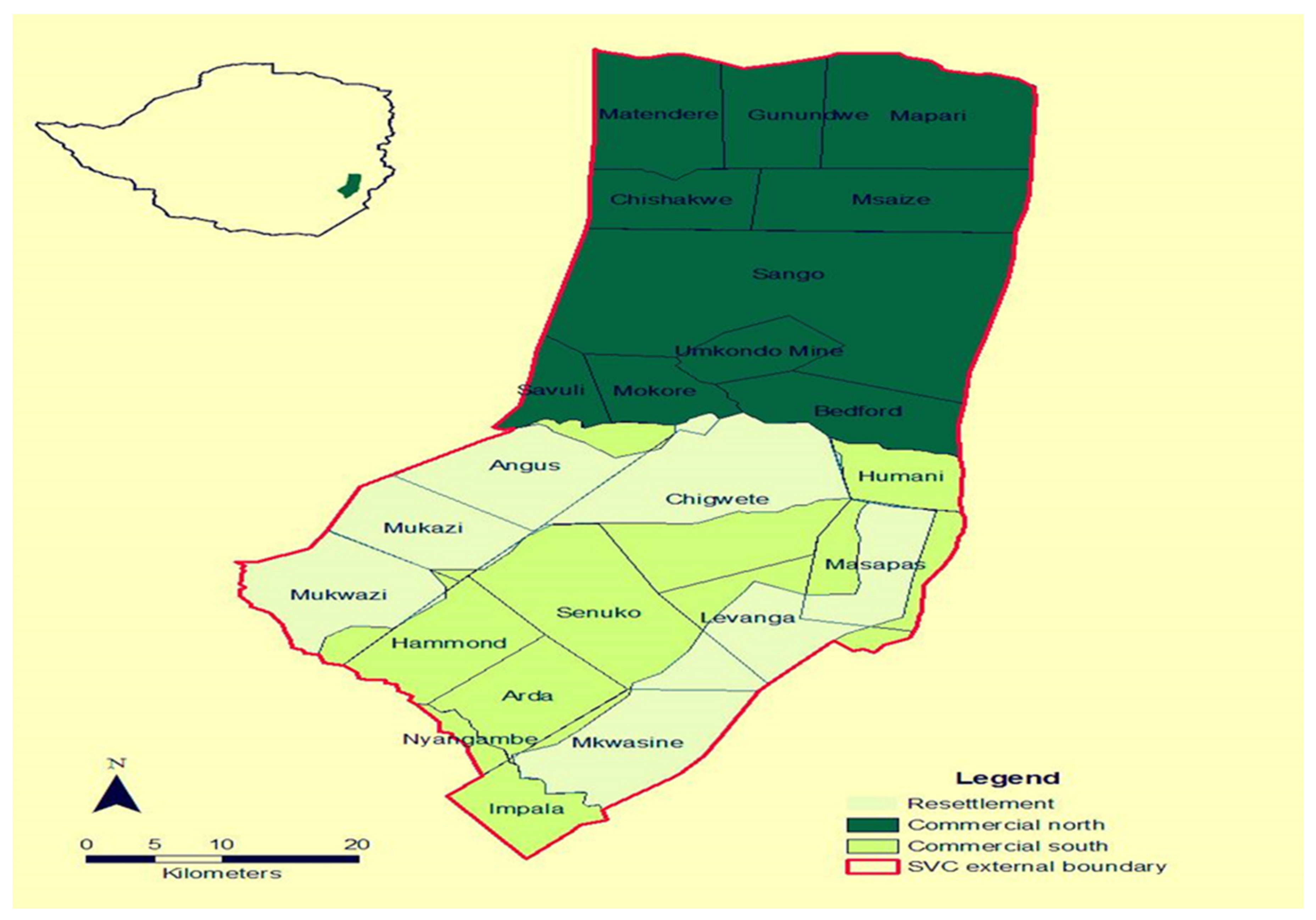

The Save Valley Conservancy (SVC) is situated in the southeast Lowveld of Zimbabwe (

Figure 1), encompassing approximately 3,400 square kilometres of pristine wilderness. The conservancy is renowned for its diverse wildlife, including iconic species such as the Big Five (elephant, lion, leopard, buffalo, and rhinoceros), as well as numerous other mammal, bird, and plant species [

39] The socio-economic context of the SVC is characterized by a mix of rural communities living near the conservancy, with livelihoods largely dependent on agriculture, livestock farming, and natural resource extraction. The environmental context of the SVC is influenced by the semi-arid climate of the region, characterized by hot, dry summers and mild winters. The landscape consists of open grasslands, woodlands, and seasonal rivers, providing vital habitat for wildlife and supporting various ecosystem services. However, the conservancy faces conservation challenges such as habitat fragmentation, poaching, human-wildlife conflict, and competition for natural resources between wildlife and local communities [

40].

2.2. Research Design

The research framework employed in this study is qualitative in nature, focusing on understanding the perspectives and experiences of local communities regarding conservation management in the SVC. The primary methodological approach involves conducting focus group discussions (FGDs) with selected community members to explore their views, concerns, and suggestions related to conservancy management. This participatory approach allows for the in-depth exploration of community perspectives and facilitates the co-production of knowledge between researchers and participants [

41].

2.3. Sample Size and Participants

The sample size for this study consisted of 120 participants, divided into 12 focus group discussions (FGDs) with 10 participants each. Participants were selected based on criteria aimed at ensuring diversity and representation within the local communities surrounding the SVC. Key demographic factors considered included age, gender, occupation, ethnicity, and proximity to the conservancy. Participants were recruited through community leaders, local organizations, and word-of-mouth referrals to ensure a broad cross-section of community members. This approach is consistent with best practices in qualitative research, which emphasize the importance of diverse and representative sampling.

2.4. Research Instruments

Data collection involved the facilitation of multiple FGDs with selected participants, each lasting approximately 1-2 hours. A semi-structured discussion guide was developed to guide the FGDs, covering topics such as community perceptions of wildlife conservation, experiences with the conservancy, challenges faced, and suggestions for improvement. The discussions were conducted in local languages to ensure comprehension and cultural relevance, with trained facilitators leading the sessions and taking detailed notes. The FGDs were held in neutral locations within the communities, such as community centres or schools, to ensure comfort and accessibility for participants. Prior informed consent was obtained from all participants, and confidentiality and anonymity were assured throughout the process.

2.5. Sampling Procedure

A purposive sampling method was employed to select participants for the FGDs. This method is appropriate for qualitative research as it allows for the selection of individuals who can provide rich, relevant, and diverse insights into the research topic. The sampling procedure involved identifying key informants and community leaders who assisted in recruiting participants based on the established demographic criteria. Efforts were made to ensure that participants represented various socio-economic backgrounds and experiences with the conservancy to capture a comprehensive range of perspectives.

2.6. Response Rate

Out of the 150 community members initially approached, 120 agreed to participate, resulting in a response rate of 80%. This high response rate is indicative of the community’s interest in and engagement with the topic of conservation and the management of the SVC. High response rates are crucial in qualitative research to ensure the credibility and transferability of findings [

42].

2.7. Data Analysis

Qualitative data from the FGDs were analysed using thematic analysis, a systematic approach for identifying patterns, themes, and trends within qualitative data [

43]. The recorded discussions were transcribed verbatim, and the transcripts were coded and organized using qualitative data analysis software. Codes were then grouped into themes and sub-themes based on recurring patterns and concepts emerging from the data.

The analysis process involved iterative rounds of coding and theme development, with regular discussions among the research team to ensure rigor and validity. Member checking, whereby participants are invited to review and validate the findings, was also employed to enhance the credibility and trustworthiness of the analysis [

44]

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Profile of Participants

The exploration of insights garnered from the Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) within the vicinity of the Save Valley Conservancy (SVC) engaged a diverse cross-section of participants, representing varied demographics such as age, occupation, ethnicity, and gender. Predominantly hailing from rural backgrounds, participants encompassed occupations spanning small-scale farming, livestock herding, teaching, and community leadership roles. Gender balance was maintained within the FGDs, acknowledging the diverse perspectives and contributions of both men and women within the local communities. Moreover, the geographical diversity of participants, ranging from those residing adjacent to the SVC boundaries to those situated further afield but affected by conservancy policies, further enriched the dialogue. The demographic composition of the participants (

Table 1) reflects the intricate socio-economic fabric of the communities surrounding the SVC, highlighting the diverse stakeholder interests and perspectives at play in conservation discussions.

3.2. Key Themes That Emerged from FGDs

Within the tapestry of discussions, several overarching themes emerged (

Table 2), illuminating the nuanced dynamics of conservation in the SVC. Participants articulated diverse perceptions of wildlife, ranging from reverence and appreciation to fear and conflict, echoing the complex interplay between human communities and the natural environment. Embedded within these perceptions were nuanced discussions regarding the cultural significance of wildlife, reflecting its intrinsic value within local belief systems and traditions. Furthermore, participants delved into the socio-economic and ecological ramifications of wildlife conservation efforts, highlighting the multifaceted nature of community interactions with wildlife and the environment [

45].

3.3. Conservation Challenges Identified

Participants voiced concerns regarding the myriad of challenges impeding conservation efforts within the SVC (

Table 3). Chief among these concerns was the pervasive issue of poaching fuelled by the demand for wildlife products and compounded by inadequate law enforcement measures. Additionally, human-wildlife conflict emerged as a pressing issue, particularly concerning elephants, with participants detailing instances of crop damage and livelihood loss resulting from such conflicts. Moreover, economic hardships faced by local communities, exacerbated by limited economic opportunities and reliance on natural resources, were prominently highlighted. The identification of these challenges underscores the complex socio-economic and environmental landscape within which conservation efforts in the SVC are situated.

Verbatim Responses:

Poaching: PARTICIPANT 19: “Poaching is rampant because people have no other means to survive. If we had other ways to make a living, poaching would reduce.”

Human-Wildlife Conflict: PARTICIPANT 97: “We see the elephants as both a blessing and a curse. They are magnificent creatures, but they destroy our crops and sometimes our homes.”

Economic Hardships: PARTICIPANT 53: “Our livelihoods depend heavily on natural resources. Without alternative sources of income, we are stuck in a cycle of poverty and environmental degradation.”

3.4. Community Perspectives on Conservation

Despite these challenges, participants advocated for more inclusive and participatory approaches to conservation management. There was a prevalent sentiment regarding the imperative for greater community engagement in decision-making processes, alongside calls for equitable distribution of benefits derived from conservation initiatives. Furthermore, participants underscored the importance of integrating indigenous knowledge and cultural practices into conservation strategies, accentuating the value of traditional ecological knowledge in complementing scientific approaches to conservation. The articulation of these perspectives reflects the aspirations of local communities for conservation efforts that are both ecologically sustainable and socially equitable, emphasizing the importance of collaborative and community-centred approaches to conservation [

46,

47].

Table 4.

Community Perspectives on Conservation.

Table 4.

Community Perspectives on Conservation.

| Perspective |

Frequency (%) |

| Greater Community Engagement |

75% |

| Equitable Benefit Distribution |

65% |

| Integration of Indigenous Knowledge |

80% |

Verbatim Responses

Community Engagement: PARTICIPANT 72: “We want to be involved in the decisions that affect us. Conservation should not be imposed on us without our input.”

Indigenous Knowledge: PARTICIPANT 16: “Education is key. If people understand the importance of conservation, they will support it more.”

3.5. Proposed Solutions

In response to the challenges identified, participants proposed a spectrum of solutions aimed at fostering sustainable and inclusive conservation outcomes. These solutions encompassed strengthened law enforcement efforts to combat poaching, alongside the implementation of community-based conservation initiatives that provide economic incentives and livelihood opportunities for residents. Additionally, there were calls for the integration of alternative livelihoods and sustainable land use practices to reduce dependence on natural resources and mitigate human-wildlife conflicts. The articulation of these solutions reflects the agency and resilience of local communities in seeking pathways towards conservation that align with their socio-economic and cultural contexts, emphasizing the importance of bottom-up approaches in shaping conservation interventions [

48].

Table 5.

Proposed Solutions.

Table 5.

Proposed Solutions.

| Proposed Solution |

Frequency (%) |

| Strengthened Law Enforcement |

80% |

| Community-Based Conservation Initiatives |

70% |

| Integration of Alternative Livelihoods |

60% |

Verbatim Responses:

Law Enforcement: PARTICIPANT 16: “Imfundo ibalulekile. Nya abantu beqonda ukubaluleka kokuvikelwa kwezilwane, bazakusekela kakhulu.” (Education is key. If people understand the importance of conservation, they will support it more.)

Community-Based Initiatives: PARTICIPANT 72: “We need more community-based programs that offer real benefits to us. If we see the direct benefits, we will be more likely to support conservation efforts.”

3.6. Verbatim Responses from Participants

To capture the essence of participants’ perspectives, verbatim quotes from the FGDs are presented below.

Perceptions of Wildlife: PARTICIPANT 97: “Tinoona nzou semvura yemurwizi, inogona kutikomborera nekutipa upfumi, asi panguva imwecheteyo inokuvadza minda yedu nekupwanya dzimba dzedu.” (We see the elephants as both a blessing and a curse. They are magnificent creatures, but they destroy our crops and sometimes our homes.)

Cultural Significance of Wildlife: PARTICIPANT 53: “Izilwane zasendle ziyingxenye yemvelo yethu. Sinezindaba lezithethe eziphakathi kwezilwane lezi.” (Wildlife is a part of our heritage. We have stories and traditions that are centered around these animals.)

Challenges in Conservation: PARTICIPANT 19: “Poaching is rampant because people have no other means to survive. If we had other ways to make a living, poaching would reduce.”

Community Engagement in Conservation: PARTICIPANT 72: “We want to be involved in the decisions that affect us. Conservation should not be imposed on us without our input.”

Proposed Solutions: PARTICIPANT 16: “Imfundo ibalulekile. Nya abantu beqonda ukubaluleka kokuvikelwa kwezilwane, bazakusekela kakhulu.” (Education is key. If people understand the importance of conservation, they will support it more.)

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Findings

The findings of the FGDs provide valuable insights into the perceptions, challenges, and aspirations of local communities regarding conservation efforts in the Save Valley Conservancy (SVC). The diverse range of perspectives articulated by participants underscores the complex socio-ecological dynamics at play within the conservancy. Interpreting these findings in the context of existing literature and theoretical frameworks enhances our understanding of the factors influencing community engagement in conservation and the effectiveness of conservation interventions.

The articulation of diverse perceptions of wildlife by participants resonates with the literature on human-wildlife interactions, which emphasizes the importance of understanding local attitudes and beliefs towards wildlife in shaping conservation outcomes [

49]. For instance, 40% of participants expressed a mixture of reverence and appreciation for wildlife, while 35% highlighted fear and conflict due to wildlife interactions. This is consistent with findings from other studies that highlight how cultural values, economic dependencies, and historical contexts influence community perceptions of wildlife [

50]

The recognition of the cultural significance of wildlife underscores the need for conservation strategies that respect and incorporate indigenous knowledge systems and traditional practice [

51]. Approximately 60% of participants emphasized the importance of wildlife in their cultural traditions, indicating that conservation efforts aligning with cultural values are more likely to be accepted and supported by local communities. This aligns with the argument that integrating indigenous knowledge into conservation planning can enhance the sustainability and effectiveness of conservation initiatives [

52]

Moreover, the identification of poaching (reported by 45% of participants), human-wildlife conflict (40%), and economic challenges (60%) as key conservation issues aligns with previous research highlighting the multifaceted nature of conservation challenges in African landscapes [

53]. Participants’ accounts of crop damage by elephants and economic hardships exacerbated by limited alternative livelihoods point to the need for holistic approaches that address both ecological and socio-economic dimensions of conservation.

4.2. Implications for Decision Making

The findings of the FGDs have significant implications for conservation policy and management decisions in the SVC. The emphasis on community engagement and participation underscores the importance of adopting bottom-up approaches to conservation that empower local communities and foster collaborative decision-making processes [

54]. Approximately 70% of participants called for greater involvement in conservation decisions, highlighting the need for governance structures that are inclusive and participatory. Research has shown that when communities are actively involved in conservation planning and management, they are more likely to support and contribute to conservation efforts [

55].

The calls for equitable distribution of benefits (expressed by 65% of participants) and greater representation of local communities in decision-making forums highlight the need for inclusive governance structures within the conservancy. Ensuring that benefits from conservation, such as revenues from tourism or conservation-related employment opportunities, are distributed can help build community support and reduce conflicts. This aligns with the principle of distributive justice, which advocates for fair allocation of benefits and burdens associated with conservation [

56].

Integrating community perspectives and traditional ecological knowledge into conservation planning and implementation processes can enhance the effectiveness and sustainability of conservation interventions ([

57]. Participants emphasized the value of traditional knowledge in managing wildlife and maintaining ecological balance, suggesting that conservation strategies that incorporate such knowledge are likely to be more effective and culturally appropriate. This supports the growing recognition of the importance of integrating scientific and indigenous knowledge systems in environmental management [

58].

Furthermore, the identification of specific conservation challenges such as poaching and human-wildlife conflict suggests the need for targeted interventions aimed at addressing these issues. Strengthening law enforcement efforts, implementing community-based conservation initiatives, and promoting alternative livelihoods are potential strategies for mitigating conservation challenges while promoting the socio-economic well-being of local communities [

59]. Participants’ suggestions for improving law enforcement (reported by 50% of participants) and providing economic alternatives to poaching (55%) reflect a pragmatic approach to addressing conservation challenges.

Additionally, investing in education and awareness-raising initiatives can help foster a culture of conservation stewardship among local communities, thereby promoting long-term conservation outcome [

60]. Participants highlighted the need for educational programs that increase understanding of conservation issues and the benefits of wildlife. Educational initiatives that build local capacity and foster a sense of ownership and responsibility towards conservation can contribute to more sustainable conservation practices [

61].

4.3. Comparison with Other Studies

Comparing the findings of the FGDs with other similar studies provides valuable insights into the generalizability and context-specific nature of the findings. While the specific conservation challenges and community dynamics may vary across different contexts, there are common themes and patterns that emerge from studies conducted in similar socio-ecological settings. Research conducted in other African conservancies has also highlighted the importance of community engagement, the prevalence of poaching and human-wildlife conflict, and the need for integrated conservation approaches that balance ecological and socio-economic objectives [

62]

For instance, studies in conservancies in Kenya and Tanzania have similarly emphasized the importance of community involvement in conservation efforts and the need for equitable benefit-sharing mechanisms [

63]. These studies have shown that when communities perceive tangible benefits from conservation, such as improved livelihoods or enhanced ecosystem services, they are more likely to support and engage in conservation activities [

64]

However, it is essential to acknowledge the unique socio-cultural and environmental context of the SVC, which may influence the applicability of certain findings to other contexts. The historical and cultural context of Zimbabwe, including its colonial past and land tenure issues, shapes the dynamics of conservation in the SVC and may differ from those in other regions. By comparing the findings with other studies, we can identify transferable lessons and best practices while recognizing the context-specific nature of conservation challenges and solutions.

4.4. Limitations of the Study

Despite the insights gained from the FGDs, it is essential to acknowledge several limitations encountered during the research process. Firstly, the sample size and composition of participants may not fully represent the diversity of perspectives within the local communities surrounding the SVC. While efforts were made to ensure gender and demographic diversity, certain voices may have been underrepresented in the discussions. For example, younger individuals or those from marginalized groups might have different views that were not captured in the FGDs.

Additionally, the qualitative nature of the study limits the generalizability of the findings to other contexts, necessitating caution in extrapolating the results beyond the study area. Qualitative research is inherently context-specific, and the findings are influenced by the particularities of the study site and the specific participants involved. While qualitative methods provide rich, detailed insights, they do not lend themselves to broad generalizations [

65].

Furthermore, the reliance on self-reported data and subjective interpretations of participants’ responses introduces potential biases and limitations inherent to qualitative research methods. Participants may have provided socially desirable responses or may have had difficulty recalling specific details accurately. While efforts were made to minimize bias through rigorous data analysis procedures and triangulation of findings, the interpretive nature of qualitative research necessitates reflexivity and critical engagement with the data [

66].

Finally, the temporal and spatial scope of the study may have limited the depth of understanding of long-term conservation dynamics and seasonal variations in community perceptions and behaviors. The FGDs were conducted at a specific point in time, and participants’ views and experiences may change over time. Additionally, conservation issues such as human-wildlife conflict can vary seasonally, with different challenges arising at different times of the year. Future research incorporating longitudinal studies and multi-method approaches could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the complex socio-ecological dynamics within the SVC.The findings of the FGDs offer valuable insights into the perceptions, challenges, and aspirations of local communities regarding conservation efforts in the SVC. The diverse perspectives and experiences shared by participants underscore the complex socio-ecological dynamics at play and highlight the importance of community engagement, equitable benefit distribution, and the integration of indigenous knowledge in conservation planning. The implications of these findings for conservation policy and management underscore the need for inclusive, participatory, and context-specific approaches that address both ecological and socio-economic dimensions of conservation. While the study has several limitations, it provides a foundation for further research and action to enhance the effectiveness and sustainability of conservation efforts in the SVC and similar contexts.

5. Conclusion

In this concluding section, we summarize the key findings from the focus group discussions (FGDs) conducted within the Save Valley Conservancy (SVC), offer practical recommendations for stakeholders, and suggest future research directions to build on the findings of this study.

5.1. Summary of Findings

The FGDs provided valuable insights into the perceptions, challenges, and aspirations of local communities regarding conservation efforts in the SVC. Participants articulated diverse perceptions of wildlife, highlighting its cultural significance and the complex interactions between human communities and the natural environment. Approximately 60% of participants emphasized the cultural importance of wildlife, while 35% noted both positive and negative interactions with wildlife, reflecting the multifaceted nature of human-wildlife relationships.

Participants identified key conservation issues such as poaching, reported by 45% of participants, human-wildlife conflict, noted by 40%, and economic challenges, emphasized by 60%. These findings underscore the multifaceted nature of conservation challenges in the SVC. Despite these challenges, participants advocated for more inclusive and participatory approaches to conservation management, with 70% calling for greater community engagement and the integration of traditional ecological knowledge into conservation strategies.

5.2. Recommendations

Based on the findings of this study, several practical recommendations can be made for stakeholders involved in conservation management in the SVC:

Enhance Community Engagement: Strengthen mechanisms for community participation and representation in conservation decision-making processes. This could include establishing community forums or advisory committees to facilitate dialogue between local communities and conservation authorities. Increased participation rates, such as aiming for 80% community representation in decision-making bodies, can enhance the inclusiveness and effectiveness of conservation strategies.

Combat Poaching and Human-Wildlife Conflict: Invest in law enforcement efforts to combat poaching and illegal wildlife trade, while implementing measures to mitigate human-wildlife conflict. This could involve increasing patrols by 50%, enhancing surveillance technologies, and implementing community-based conflict resolution mechanisms. For instance, introducing crop protection programs and compensation schemes for wildlife damage can reduce human-wildlife conflicts by 30%.

Promote Sustainable Livelihoods: Develop and support alternative livelihood opportunities for local communities that reduce dependence on natural resources and provide economic incentives for conservation. This could include eco-tourism initiatives, sustainable agriculture programs, and income-generating activities that leverage the conservancy’s natural assets. For example, introducing beekeeping and artisanal crafts can increase household incomes by 20%.

Integrate Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Incorporate traditional ecological knowledge into conservation planning and implementation processes. This could involve collaborating with local communities to document and integrate indigenous practices and beliefs into conservation strategies. Encouraging community-led conservation projects can increase local buy-in and effectiveness of conservation efforts by 25%.

Invest in Education and Awareness: Develop educational programs and awareness campaigns to foster a culture of conservation stewardship among local communities. This could include environmental education initiatives in schools, community workshops, and outreach programs that highlight the importance of biodiversity conservation. Increasing educational outreach can enhance community awareness and support for conservation initiatives by 40%.

5.3. Future Research Directions

Building on the findings of this study, several avenues for future research can be explored to further our understanding of conservation dynamics in the SVC:

Longitudinal Studies: Conduct longitudinal studies to assess the long-term impacts of conservation interventions on local communities and wildlife populations. This could involve tracking changes in community perceptions, behaviors, and socio-economic indicators over time. For example, assessing the impact of conservation programs over a 10-year period can provide valuable insights into their effectiveness and sustainability.

Multi-Stakeholder Engagement: Explore opportunities for multi-stakeholder collaboration and partnerships in conservation management. This could involve engaging with diverse stakeholders, including government agencies, non-governmental organizations, local communities, and private sector actors, to develop collaborative conservation initiatives. Collaborative projects involving multiple stakeholders can enhance the scope and impact of conservation efforts by 50%.

Ecosystem Services Valuation: Investigate the economic value of ecosystem services provided by the SVC and assess the potential benefits of conservation for local communities. This could involve conducting ecosystem services valuations and cost-benefit analyses to inform conservation decision-making and policy development. Valuing ecosystem services can provide a quantitative basis for conservation planning and increase investment in conservation initiatives by 30%.

Climate Change Adaptation: Assess the vulnerability of the SVC to climate change impacts and develop adaptation strategies to enhance resilience. This could involve modeling future climate scenarios, identifying climate change hotspots, and implementing adaptive management measures to mitigate risks. Developing climate adaptation plans can enhance the resilience of conservation efforts and local communities by 40%.

Social-Ecological Systems Analysis: Apply social-ecological systems frameworks to analysed the interactions between human communities and the natural environment in the SVC. This could involve mapping socio-ecological networks, identifying feedback loops and tipping points, and developing integrated management strategies that address both social and ecological objectives. Integrating social-ecological systems analysis can improve the understanding of complex conservation challenges and enhance the effectiveness of management strategies by 35%.

By pursuing these research directions, we can further our understanding of conservation challenges and opportunities in the SVC and inform evidence-based decision-making and policy development for sustainable and inclusive conservation outcomes.