1. Introduction

Nitrogen (N) is an essential nutrient for living organisms as it constitutes a vast range of fundamental biomolecules such as proteins and nucleic acids [

1]. In plants, N serves to build amino acids, proteins, enzymes, chlorophyll, and other related important chemicals. Plants can assimilate inorganic N from the soil in the form of nitrate and seldom ammonium. On the other hand, atmospheric N is abundant but inert and needs to be converted into usable forms through biological fixation. Some major cereals like maize, wheat, and rice rely substantially on N for growth and productivity. Unlike legume plants, cereals lack stable symbiotic relationship with the N-fixing bacteria. Hence, cereals lack the ability to fix N from the atmosphere by themselves, although they can establish associations with various N-fixing microorganisms [

2,

3,

4,

5].

In recent decades, there has been a decreasing trend in soil organic matter, leading to a decline in nitrogen content in the soil. This decline is predominantly due to intensive cultivation cycles since the 1960s, which has promoted the development of nitrogen fertilizers to remedy the deficits of this plant nutrient.

The Haber-Bosch process developed in 1909 by Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch, devised an artificial nitrogen-fixing process, which enabled the large-scale industrial production of ammonia [

6]. According to the International Fertilizer Association's "World Ammonia Capacities 2023," global production capacity in 2023 reached about 192.3 million tonnes of nitrogen corresponding to ~233.9 million tonnes of ammonia [

7]. However, this is a highly energy-demanding process, it uses fossil fuels, and it is currently considered one of the largest greenhouse gas emitters, responsible for 1.2 % of CO

2 emissions globally [

8].

Excessive nitrogen fertiliser usage leads to significant environmental losses, such as nitrate leaching into water bodies, and greenhouse gas emissions [

9]. In the European Union, N losses are estimated to cost at least 70 billion euros per year [

10].

In response to these challenges, the European Commission presented the European Green Deal in December 2019, with the goal of making Europe the first continent to achieve a zero-climate footprint by 2050. From this standpoint, the EU aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030, compared to 1990 levels [

11]. Worldwide there is a clear need to find alternatives to the use of synthetic fertilizers, due to their negative impact on the environment.

Recent advancements have highlighted the potential of Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria (PGPB) as a sustainable alternative to chemical fertilizers. Inoculation with the associative N-fixing bacteria

Azospirillum has shown some promise in promoting growth and N fixation in cereals. Under microaerobic conditions,

Azospirillum allows the conversion of atmospheric N into ammonium by the action of a nitrogenase enzyme complex, although this bacterium fixes N at a lower rate than

Rhizobium bacteria in legume plants. Nitrogen metabolism molecular mechanisms in plants are imperative to understand, and the link with N-fixing bacteria should be exploited for the progress of sustainable means to enhance nitrogen use efficiency in agriculture [

12,

13,

14,

15].

Microbial inoculants containing isolated beneficial microorganisms from natural environments are an emerging approach to both increasing food production and minimizing harm to human health and the environment; it is therefore a possible alternative to major synthetic chemicals in modern agriculture [

16,

17]. The application of specific PGPB strains has demonstrated improved plant growth and stress tolerance, with examples provided by recent studies showcasing their effectiveness in enhancing crop productivity and resilience. These bacteria not only boost nutrient uptake but also help plants tolerate abiotic stresses such as drought and salinity, improve soil health, and reduce dependency on chemical pesticides [

18,

19,

20].

PGPB have been proven to enhance soil health by sustaining organic matter decomposition and nutrient cycling, which can lead to long-term increases in soil fertility and structure. Certain PGPB strains, such as

Azospirillum, can also release phytohormones that stimulate root growth and boost nutrient uptake efficiency, and develop systemic resistance against plant diseases, which improves plant defence systems and reduces dependency on chemical pesticides [

21,

22].

As a recent definition from the European regulation no. 1009/2019, biostimulants are products containing substances and/or micro-organisms which, when applied to the plant or rhizosphere, stimulate natural processes that improve nutrient uptake and assimilation efficiency, tolerance to abiotic stresses and/or product quality, independently of their nutrient content. In recent years, the market for biostimulant products has been continuously expanding, with the European market leading the way, showing the largest volumes, i.e., ~50% of the world market. The growth potential of this market has attracted significant interest from the major companies in the sector, leading to a surge of biostimulant product launches on the market and an exponential increase in scientific publications [

23].

Among PGPB, the strains of

Methylobacterium have been researched extensively for their plant growth-promoting activities, thereby positively impacting the growth of numerous plant species [

24,

25,

26,

27]. These bacteria are gram-negative, rod-shaped, strictly aerobic and are a part of the

Alphaproteobacteria class. They are characterized by pinkish pigmentation due to the synthesis of carotenoids [

28]. For growth,

Methylobacterium can utilize organic compounds containing only one carbon (C1), such as methanol or methylamine [

29]. It can be found in various habitats such as soil, leaf surfaces and air [

30]. These pink-pigmented facultative methylotrophic bacteria (PPFMs) have been observed to form relationships with over 70 plant species [

31]. The epiphytic

Methylobacterium species often cross the leaf surface and penetrate leaf stomatal openings, establishing endophytic bacterial communities [

32].

Methylobacterium spp. can fix atmospheric nitrogen in plant leaves [

33], representing a significant advantage for plants hosting these bacteria, that can convert atmospheric nitrogen N

2 into ammonium (NH

4+) through the nitrogenase enzyme [

29].

Methylobacterium symbioticum is a novel species recently isolated from spores of the symbiotic fungus

Glomus iranicum var.

tenuihypharum [

34], demonstrating the potential to reduce nitrogen chemical fertilization in maize, rice and wine grape following its application, without affecting their growth and yield, but seldom obtaining even higher yield than controls.

Given this background, this study aims to evaluate the effect of a biostimulant containing Methylobacterium symbioticum on the growth and yield of a common wheat variety under decreasing doses of synthetic nitrogen fertilization. Specifically, it was investigated the effects of the application of a commercial product BlueN® containing the strain SB23 of such bacterium at late tillering stage, to potentially reduce the mineral nitrogen fertilization, while trying to maintain or enhance the performance of the crop. This study investigated the effects of Methylobacterium symbioticum application on i) shoot and root growth of wheat; ii) dynamics of leaf chlorophyll content and canopy greenness; iii) photosynthesis response; iv) grain yield and quality, the latter referred to as gluten content and composition, and consequences on flour rheological properties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Trial Set-Up

The field trial was conducted at the AGRITAB farm, located in the municipality of Legnago, Verona, Italy, 15 m above sea level, during the 2022-23 growing season. The trial was conducted over a single growing season. The soil was sandy loam with a pH of 8.4, 1.56% organic matter, a CEC of 11.6 cmol (+) kg-1 and a total N content before sowing of 0.97 g kg-1. Climatic data were obtained from a meteorological station in Legnago-Vangadizza and managed by the ARPAV regional weather service centre.

The preceding crop was grain maize, fertilized with approximately 240 kg N ha-1.

The trial was conducted in a 3.80-ha field area, on the soft wheat var. “LG Auriga” (LG seeds, Parma - Italy). The field was divided into four sections/treatments, each comprising three plots/replicates (n = 3), following a split-plot experimental design. Each plot, extending 4 m in length and thirty-three wheat rows in breadth, was positioned centrally within the treated zone and at least 10 m apart. Treatments were 100% of N dose, as from local recommendation (i.e., 180 kg N ha

-1), with and without

Methylobacterium symbioticum inoculation, and a reduced N dose (130 kg N ha

-1), again with and without the bacterial inoculum (

Table 1).

During October 2022, the soil was ploughed to a depth of 0.35 m and then fertilized with 250 kg ha-1 of an N-P fertilizer (9% N, 20% P2O5), equivalent to 22.5 kg N ha-1. The seedbed was then prepared by refining the soil with a rotary harrow to facilitate sowing, which took place on 3 November 2022. Seeds treated with fungicides (a.i. Sedaxane + Fludioxonil + Difenconazole), were distributed with a sowing density of 210 kg ha-1, (~530 seeds m-2;) with a 12 cm interrow.

A first dressing N fertilization was done at the end of February before stem elongation on all the experimental area, regardless of the treatment, with 370 kg ha-1 of N-S fertilizer (30% N, 15% SO3), corresponding to an additional 111 kg N ha-1 to the soil. A second fertilization was carried out at the end of April, approximately at ear emergence, by applying 175 kg ha-1 of ammonium nitrate (27% N), equivalent to 47.3 kg N ha-1, only in the 100%N and 100%N + Methylobacterium symbioticum SB23 treatments (hereafter referred to as “bact”).

The crop was protected against weeds, pests, and diseases following local recommendations and weather conditions. On 20 March a chemical weed control was applied with a post-emergence treatment with a.i. Tritosulfuron + Florasulam, together with a.i. Pinoxaden + Clodinafop. Weeding was associated with a fungicide treatment with a.i. Mefentrifluconazole + Pyraclostrobin. The application of 333 g ha-1 of the biostimulant BlueN® containing Methylobacterium symbioticum strain SB23 at a concentration of 3×107 CFU g-1, as a wettable powder, in the 100%N + bact and 75%N + bact treatments occurred on 25 March.

A second fungicide treatment containing the a.i. Metconazole was applied at the beginning of May 2023, in combination with an insecticide treatment based on a.i. Tau-Fluvalinate.

All herbicide and fungicide treatments and the distribution of BlueN® were conducted with 350 L ha-1 of water. The harvesting took place on 28 June 2023.

2.2. Environmental Scanning Electron Microscope (ESEM) Imaging of Bacteria-Leaf Interactions

ESEM was used to assess the ability of

Methylobacterium symbioticum SB23-based inoculum to colonize wheat leaves. This method facilitates the examination of biological specimens without the need for histological processing of samples, enabling the direct visualization of bacterial colonization both externally and internally within plant cells and tissues, providing a true depiction of the interaction [

35].

A suspension of Methylobacterium symbioticum SB23 was plated in Luria-Bertani (LB) solid medium at different dilutions and incubated at 28°C for 72 hrs. After obtaining single isolates, single colonies were cultured in 100 mL of LB medium on a rotary shaker at 28°C for 48 hrs. After centrifugation, bacterial cells were re-suspended in sterile water to attain a final inoculum density of 3 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU) per mL.

The bacterial suspension was spread on the first leaf of 7-day-old wheat plantlets grown in sterile conditions on ½ MS agar medium [

36], 1% sucrose, and inoculated plants were allowed to grow for another 7 days. Uninoculated plants were used as controls.

At the end of the incubation period 5-mm large fresh leaves sections were excised with a sterile lancet and morphological analysis was performed using ESEM instrument Quanta™ 250 FEG (FEI, Hillsboro, OR) in wet mode as previously described by Visioli et al., 2014 [

37].

2.3. Shoot Growth Analysis

Monitoring of vegetational indexes was carried out during the vegetative growth of wheat, from the beginning of stem elongation to almost maturity. The leaf chlorophyll content was indirectly assessed through SPAD (Soil and Plant Analysis Development) values. Measurements were taken on 12 plants for each plot/replicate of all the treatments by using a SPAD 502 chlorophyll meter (Konica-Minolta, Hong Kong): each plot was divided into 3 sub-plots of approximately 4 m x 1.30 m size and SPAD readings were taken on 4 representative plants randomly distributed in the sub-plot. For each plant, the SPAD value was derived from the average of two readings taken at about one-third and two-thirds of the leaf blade of the last completely developed leaf, and the flag leaf when emerged. SPAD measurements were taken weekly from 15 April to 11 June 2023.

Concurrently with the SPAD measurements and until 18

th June 2023, the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) of the canopy of each plot was monitored with an active handheld Greenseeker spectrometer (NTech Industries, Ukiah, CA, USA). The sensor detects canopy reflectance at wavelengths of 590 nm (refRED) and 880 nm (refNIR) and provides a ratio value as follows:

The measurement was made by advancing longitudinally along the plots, keeping the sensor approximately 30 cm above the crop.

On 13 May 2023, during milk development, 0.12-m2 wheat samples (1-m long row) within each plot were collected to measure some morphological parameters and shoot biomass. Plant height and the uppermost internode length were measured in 3 plants randomly selected within each sample. Leaves, culms and spikes of each 0.12-m2 area were assessed for fresh and dry weights (DW) of each component. DW was measured following oven-drying at 65°C for 48 h, allowing the leaf-to-culm DW ratio to be also calculated.

Before drying, the photosynthesizing/green surface of leaves and culms was assessed using the LI-3100C Area Meter (Li-Cor instruments), allowing the Leaf Area Index (LAI), the Culm Area Index (CAI) as well as the LAI-to-CAI ratio to be calculated.

On May 29, 2023, during dough development, the leaf photosynthetic activity was measured using an infrared gas analyzer LI-6800 (Li-COR Inc., Lincoln, Nebraska, USA). PSII Photosynthetic Efficiency (

Fv′/Fm′), stomatal conductance (gsw), transpiration rate (Emm) and CO

2 Net Assimilation (A) were determined following the methods described by Murchie and Lawson [

38].

The Fv′/Fm′ ratio was measured as an index of efficiency in energy harvesting by the oxidized (open) reaction centres of photosystem II (PSII) of the flag leaf, where Fv′ and Fm’ represent variable and maximal fluorescence, respectively. As Fm′ includes minimal fluorescence (F0′) of a dark-adapted leaf, Fv′ is calculated as difference Fm′ – F0′. Dark adaptation of the measured leaf was obtained using the far-red light to excite photosystem I (PSI), thus forcing electrons to drain from PSII. Only a few seconds of far-red light are needed to obtain this effect. The fluorimeter provides a “dark pulse” routine used to determine F0′. Eight Fv′/Fm′ records were registered on one leaf for each replicate.

Methylobacterium symbioticum strain was assessed for ACC (1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate) deaminase activity through a qualitative test; the growth of the bacterial strain was compared on two types of substrates, one containing ACC as the sole nitrogen source and the other with no nitrogen source. The bacterium was grown overnight in 10 mL of Luria and Bertani's liquid medium by shaking (130 rpm) at 28 °C. After measuring the optical density (OD) at 600 nm with a spectrophotometer (Varian Cary 50 UV-Visible), the bacterial suspension was diluted to 10

8 cells mL

-1 with sterile double-distilled water and plated on Luria Bertani agar medium. Following 24 h of incubation at 28°C, a bacterial colony was streaked to a Petri plate containing modified DF [

39], minimal salts medium (glucose, 4.0 g/L; citric acid, 2.0 g/L; KH

2PO

4, 4.0 g/L; Na

2HPO

4, 6.0 g/L; MgSO

4 .7H2O, 0.2 g/L; micro-nutrient solution (FeSO

4, 100mg/100ml; H

3BO

3, 10 mg /100ml; ZnSO

4 .7H2O, 124.6 mg /100ml; Na

2MoO

4, 10 mg /100ml; CuSO

4, 78.22 mg /100ml; MnSO

4, 11.19 mg /100ml)) and 3 mM 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) as the sole nitrogen source. For the negative control, DF minimal medium without ACC was used. Growth of isolates on DF medium supplemented with ACC was assessed after incubation for 72 h at 28°C and compared to controls. Additionally,

Bosea robiniae and

Pseudomonas umsongensis were used as negative and positive ACC deaminase producers, respectively [

40].

2.4. Root Growth Analysis

The root system was investigated down to a depth of 1 m on 11 June 2023, roughly at the end of dough development, by soil coring. A probe was placed along the seed row to extract a 1 m long soil core for each plot/replicate, which was then divided into 10 sub-samples, each 10 cm long. Samples were kept at a temperature of -18 °C until washing. To separate the roots from the soil, a hydraulic sieving-centrifugation device on a 500-µm mesh sieve was used, and roots were stored in a 15% v/v ethanol solution at 4 °C until digitalization.

An EPSON Expression 11000XL PRO scanner was used to digitize the root images. Each sample was taken from the preservative solution and washed with demineralized water, and the roots were placed on a plexiglass tray with the help of a thin film of water (~3 mm). The scanner resolution for image acquisition was set to 400 DPI, in binary (1 bit) format in order to save computer memory resources.

Images were processed using KS 300 Rel. 3.0 software (Carl Zeiss Vision GmbH, Munich, Germany), with a minimum area of 40 pixels and elongation index E.I. (perimeter2 / area) >40 for thresholding background noise. Objects with a round shape (E.I.< 40) were considered extraneous objects and thus not detected by the software.

Root length and area were calculated using the skeletonization/thinning algorithm. The area of skeletons (1-pixel width root objects) was multiplied by a correction factor of 1.12 [

41,

42] to account for all the possible angles of the roots arranged on the tray. The mean root diameter was calculated as the area-to-length ratio of root objects for each 10-cm long root sub-sample. Successively, Root Area Density (RAD) and Root Length Density (RLD) were determined and expressed as cm of roots per cm

3 of soil and cm

2 of roots per cm

3 of soil, respectively. Lastly, root dry weight was calculated after oven-drying for 2 days at 105 °C.

2.5. Yield Parameters and Grain Quality

At maturity, 1-m2 sample of wheat plants was taken from the central part of each plot/replicate. Threshing was conducted using a stationary combine harvester to determine yield and yield parameters. The harvest index HI (grain-to-total shoot DW ratio) was measured after oven drying (65°C for 48 h), while the thousand seed weight (TSW) by averaging the weights of three subsamples of 1,000 seeds from each plot/replicate.

The nitrogen content in straw and grain was determined using the Kjeldahl method [

43], following the determination of nitrogen content, the total grain protein content (GPC) was obtained by multiplying the percentage of N by the coefficient 5.7.

Gluten composition was assessed by quantifying gliadins, high-molecular-weight glutenins (HMW-GS) and low-molecular-weight glutenins subunits (LMW-GS) extracted from refined flour following the procedure of Visioli et al. [

44].

Rheological properties of dough produced from milled grains of the different treatments were investigated with the Chopin Alveograph Alveo PC model (Buhler, Leobendorf - Austria) to determine dough strength (W), tenacity-to-extensibility ratio (P/L index) and protein degradation index (PDI). The latter is expressed as the percentage of strength (W) loss of the dough remaining for 180 minutes in the alveograph compared to the normally calculated W at 28 minutes from dough preparation. Additionally, Brabender Farinograph was used for the determination of other parameters, such as dough stability. The grain samples of the 3 replicates were pooled together to have sufficient sample size for rheological analyses, so these have one replicate only.

The total content of macro and micronutrients (Ca, Fe, K, Mg, P, Zn, Na and Mn) in the grain and straw of the harvested plants was determined after sample mineralization with a Milestone Ethos 900 microwave mineralizer (EPA Method No. 3052, USEPA, 1995). Mineralized samples were analyzed by ICP-OES (Inductively Coupled Plasma - Optical Emission Spectroscopy) using a Spectro Ciros Vision EOP instrument (Spectro Italia S.r.l., Lainate, Milan).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The data from all the assessed parameters were subjected to ANOVA (

Table S1) and the separation of homogenous groups of means was done with the Tukey test using R Studio software (P ≤ 0.05).

4. Discussion

The development of ecological practices to increase productivity and decrease dependence on chemical fertilizers in cereal production is a current challenge for agriculture. In recent years, an emerging approach has involved applying foliar biostimulant products, given their ease of application and low cost, especially when coupled with other agricultural practices such as herbicides, fungicides, and nutrient sprayings. Several studies have focused on the efficacy of these products, which often contain stimulating substances such as amino acids, humic acids, or beneficial microorganisms such as PGP bacteria [

45,

46], investigating the potential for reducing chemical fertilization while preserving yield and quality standards. However, the new strain

Methylobacterium symbioticum, isolated by Pascual et al. in 2020 [

34], lacks an extensive bibliography and the effects of an inoculum based on this bacterium in common wheat have not been tested yet.

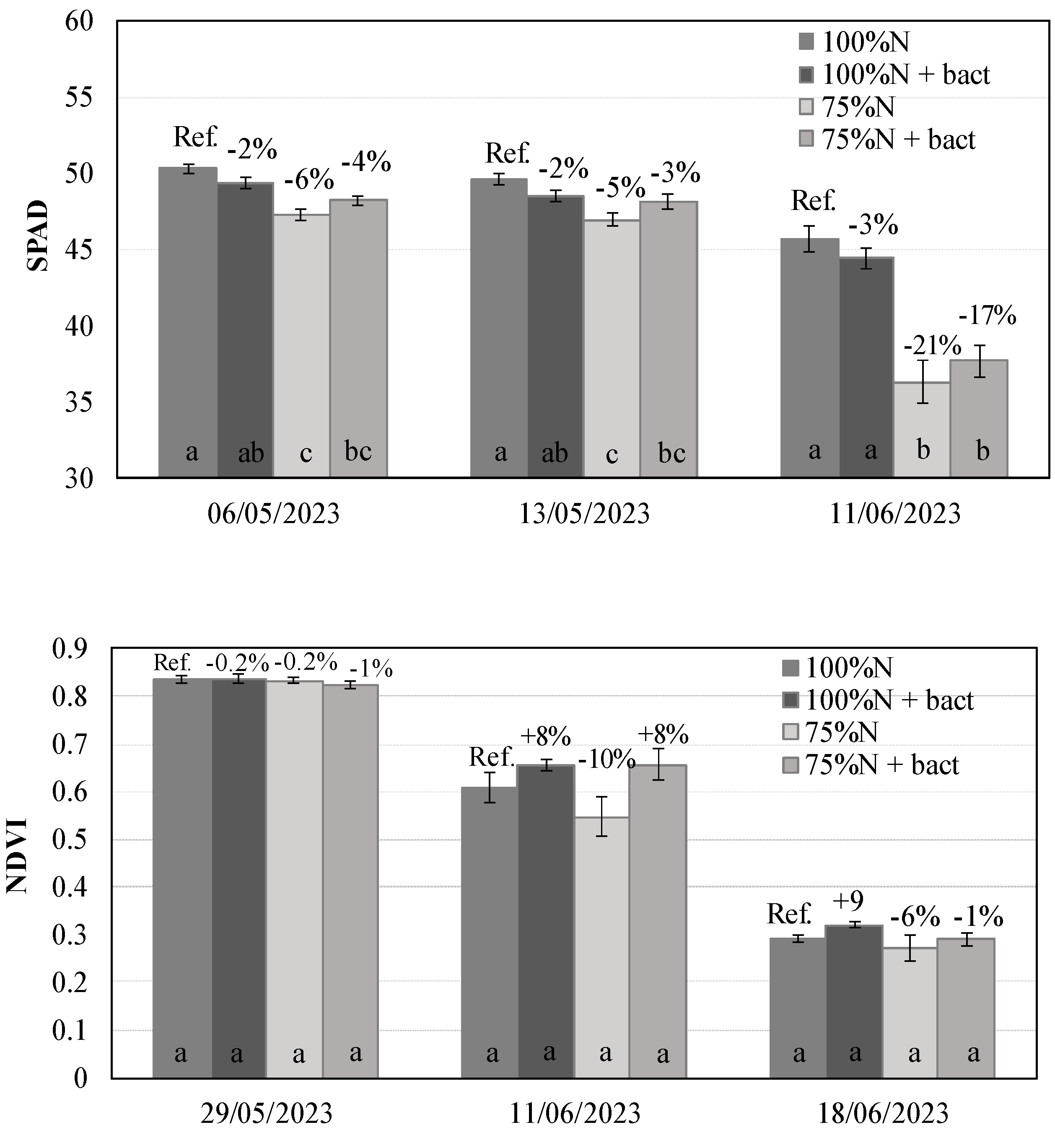

Consistently with findings by some authors in crops such as maize, strawberry and apple [

29,

34], this trial confirmed the positive effects on some vegetational parameters (SPAD and NDVI) following the inoculation with

Methylobacterium symbioticum. This inoculum allowed a more prolonged stay-green period of the crop, thereby extending the photosynthetic activity during the crop cycle. For biomass crops such as maize, this could represent an agronomic advantage by allowing the plant to continue photosynthesizing for longer, thereby being able to assimilate more CO

2, and increasing total biomass at harvest. This study on common wheat showed that SPAD, near harvesting, as expected, was significantly lower in plots fertilized with the reduced dose of nitrogen (75%N) with respect to the reference. However, the “75%N + bact” treatment reduced this difference, demonstrating that the bacterium is able to delay chlorophyll degradation close to the end of the crop cycle. Additionally, the tendency, albeit not significant, for the plots treated with the microbial biostimulant to show higher SPAD values, which is an index indirectly correlated to chlorophyll content, than untreated plots, especially at the lower N fertilization dose, highlights how in the case of low N fertilization level the bacterium is better able to express its effects. It is probable that a plant with a worse nitrogen nutritional status is more favourable to establishing and maintaining an endophytic relationship with these plant aiding bacteria. Similar evidence emerged in an in vitro test in maize [

29], in which at a reduced dose of 50%N, the application of the bacterium increased the SPAD values when compared to the full fertilized control, thus confirming a better establishment of the association if the plants are under nutritional deficit/stress.

The analysis also revealed that canopy NDVI at the end of the cycle was statistically similar across all treatments, but with better values in the “75%N + bact” plots than in the “75%N” ones. Previous experiments have shown that various strains of the genus

Methylobacterium exhibit ACC-deaminase activity [

47]. Under this assumption, the preliminary in-vitro test revealed that the strain tested here also possesses this enzyme activity capable of delaying plant senescence by the degradation of the ethylene precursor, thus resulting in an extension of the foliar stay-green. This enzyme breaks down ACC, the precursor of ethylene, lowering ethylene synthesis while increasing stress tolerance [

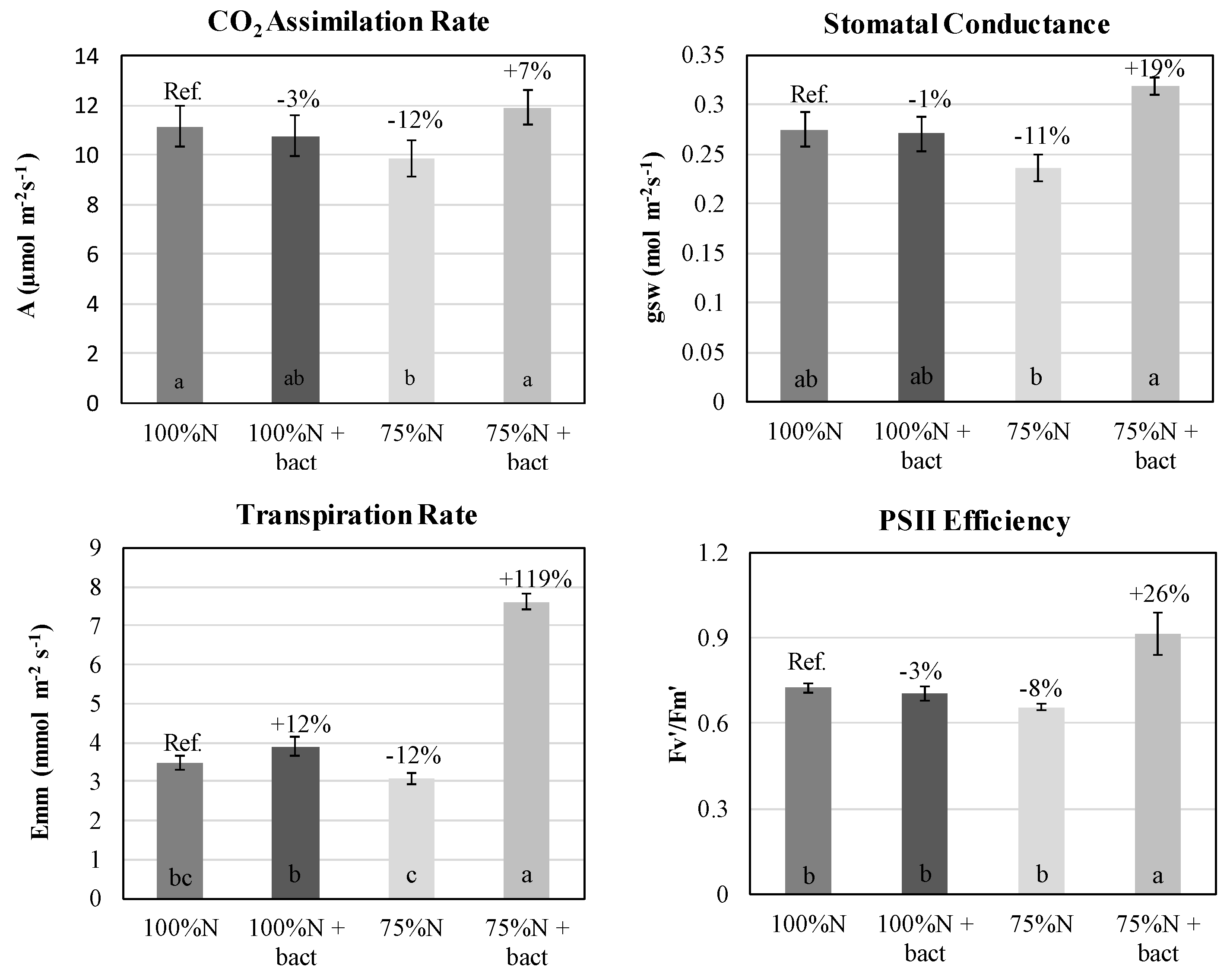

48]. This mechanism is consistent with the observations of longer canopy stay-green and increased photosynthetic efficiency. Indeed, while the bacterial treatment did not lead to substantial effects on morphological traits (e.g., plant height, uppermost internode length, LAI and shoot biomass), there were notable effects on photosynthetic parameters. The “75%N + bact” treatment had a positive effect on the wheat plants, increasing stomatal conductance and transpiration rate, compared to both “100%N” control and the corresponding N fertilization dose without the inoculum (75%N). Better CO

2 assimilation rate and PSII efficiency were also observed. This evidence aligns with the SPAD findings and demonstrates how plants seek a bond with microorganisms to compensate for a nutritional deficit. Conversely, at the higher dose of nitrogen fertilization, this does not seem to occur given the higher availability of nitrogen in the soil: it can be seen in vegetative parameters, in which there is a tendency for the “100%N + bact” treatment to be very similar to the reference. Therefore, it emerges that the bacterium has a physiological influence on the plant mostly in the case of reduced N fertilization.

Similar studies with other PGPB also indicated similar benefits. For example, Bhattacharyya and Jha [

21] reported that the association with

Azospirillum brasilense enhances the growth of various crops by fixing atmospheric N

2 and synthesizing growth-promoting substances. Egamberdieva and Lugtenberg [

22] observed that

Pseudomonas fluorescens enhanced the tolerance of plants to saline stress with the production of phytohormones and ACC deaminase, which ultimately decreases the level of ethylene and improved growth.

Methylobacterium symbioticum is claimed to be N-fixing in its endophytic life in plants [

33], and it is expected to increase the fixation ability under reduced N availability, as occurring in many N-fixing symbiosis. This would explain better success of inoculation under 75%N vs. 100%N. Nitrogen fixation was not investigated in this trial, but better N content in wheat grains and straw and enhanced photosynthetic parameters, especially at reduced N fertilizer dose, would corroborate the ability of

Methylobacterium symbioticum to fix atmospheric N

2. Surely, under reduced N fertilization, this bacterium retrieves some N at metabolic level by degrading the plant ethylene precursor ACC thanks to the ACC deaminase enzyme, in this way also delaying plant senescence.

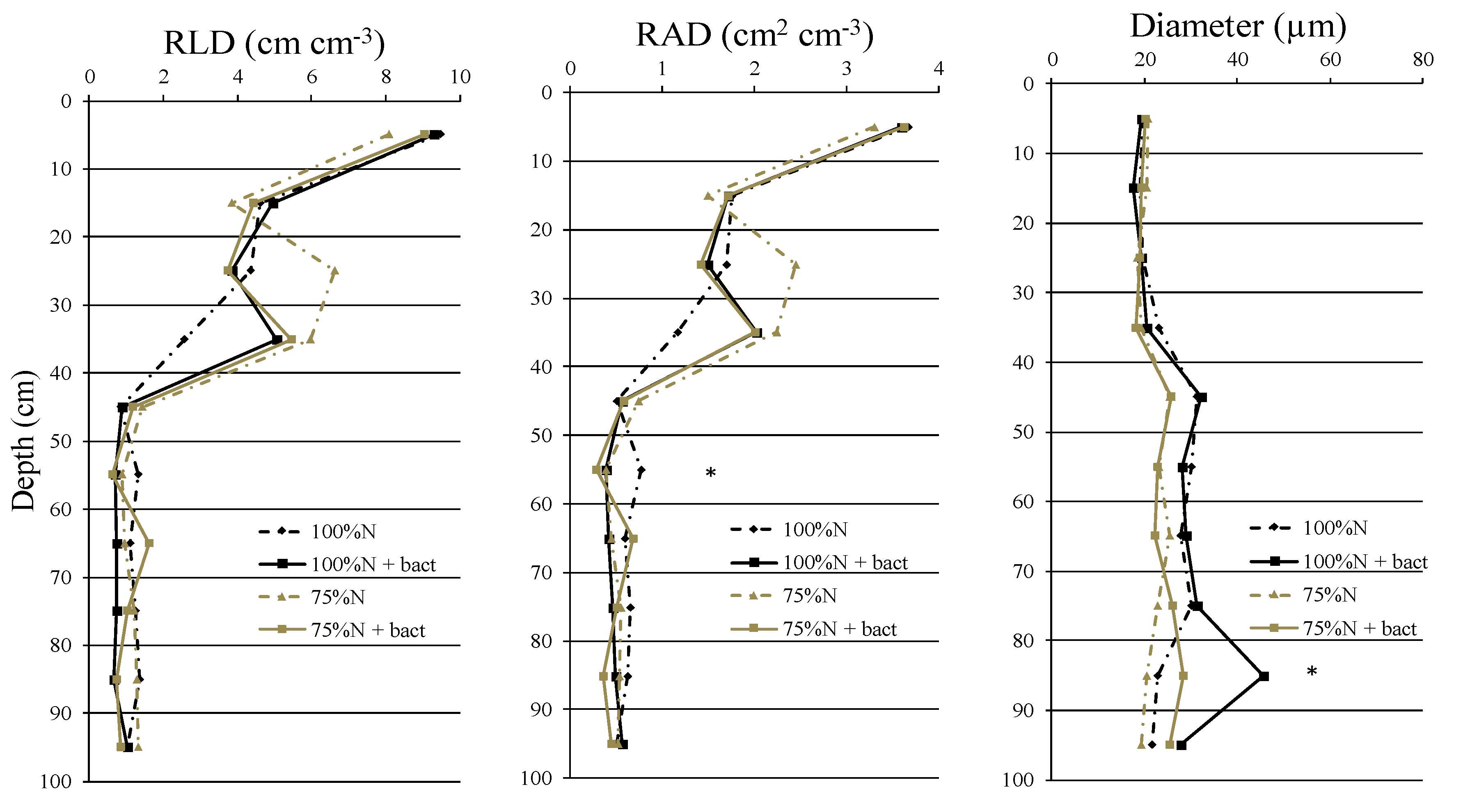

No studies can be currently found in the literature assessing the effect of the

Methylobacterium symbioticum strain on root growth, although some PGPBs including the genus

Methylobacterium, and particularly

Azospirillum, are known to create associations with plants that lead to an improvement in the root system [

49], probably due to the production and exchange of bioregulators such as auxins or auxin-like compounds. This study showed, in agreement with the literature, good RLD and RAD values in the 0-100 cm soil profile of wheat in all treatments, with an RLD greater than 2.8 cm cm

-3 and a RAD greater than 1.16 cm

2 cm

-3 [

50]. Here,

Methylobacterium symbioticum association with common wheat did not show significant effects on root growth, except for a certain increase in RLD and RAD in the arable layer. The "75%N" treatment, having reduced chemical N supply, exhibited higher root growth than “100%N”, aligning with the well-known plant response to nitrogen deficiency by encouraging root growth for better soil exploration [

51,

52]. The "75%N + bact" treatment showed root growth levels very similar to the reference “100%N”, probably due to nitrogen compensation from atmospheric N

2 fixation by the bacterium, thus decreasing the need for an extensive root system.

Yield and other production parameters remained stable across treatments, indicating that the bacterium does not have a significant influence on these parameters. In contrast, other studies show that the application of

Methylobacterium symbioticum increased yields in maize, grapevine, rice and strawberry, particularly at lower doses of N supplied [

29,

34]. These authors suggest that the enhanced crop performances might be attributed to the capability of microorganisms to assimilate ammonium through N fixation. Despite this being an energy-consuming process, it ultimately leads to the conservation of energy for the plant during the assimilation of nitrogen. This is because the plant can bypass the energy-intensive step of converting nitrate, deriving from root uptake, to ammonia, as it directly receives ammonium from the microorganisms. This would make the utilization of nitrogen more efficient, leading to an improved plant growth [

29].

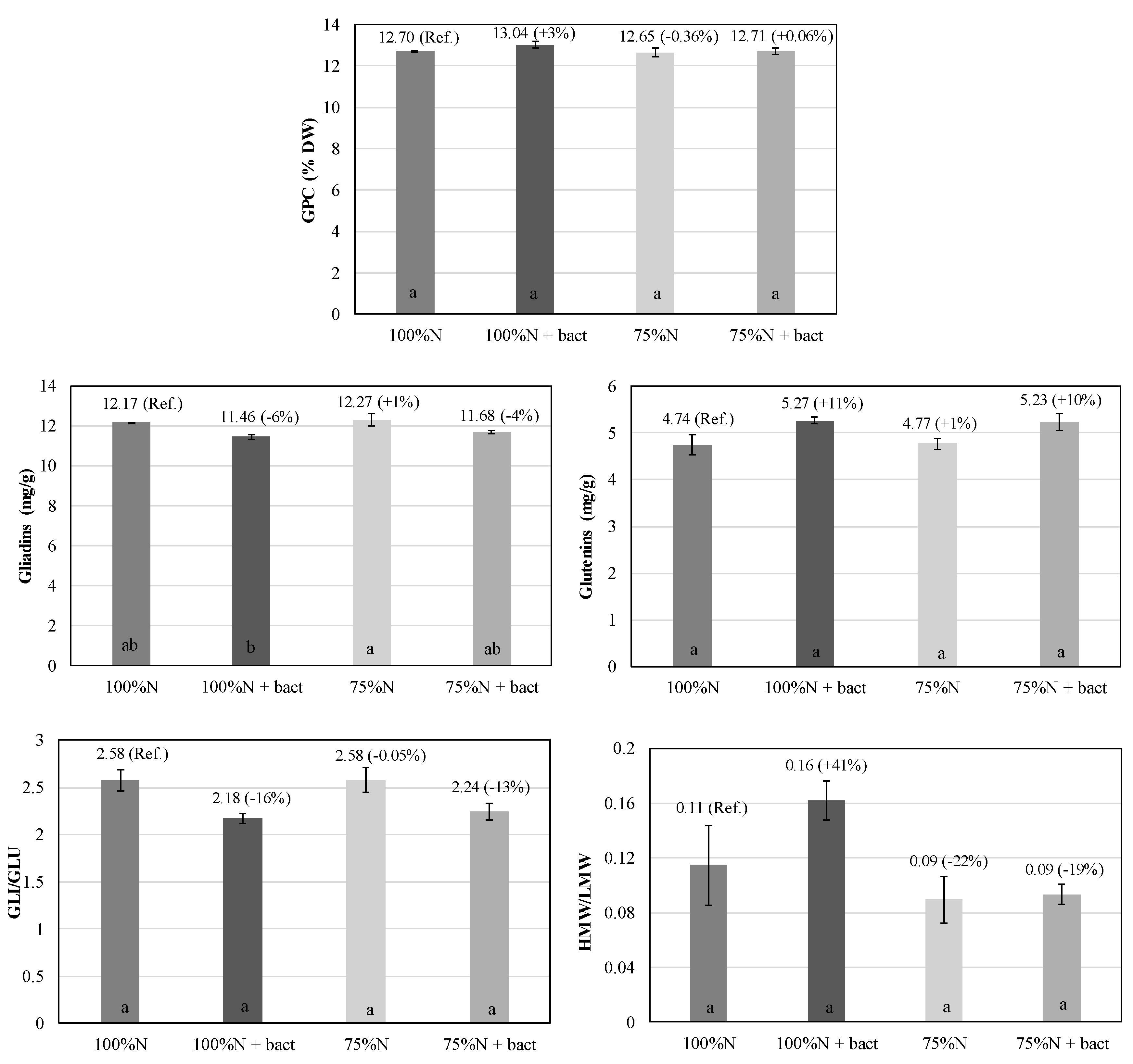

Regarding grain quality, the microbial biostimulant did not increase significantly the protein content (GPC), consistently with N content findings. However, it impacted protein quality, with an increase in glutenins over gliadins, and HMW over LMW. Therefore, it was associated to an increase in the high molecular weight protein component over the low molecular weight component, with the final effect of increasing dough tenacity and stability.

To assess the possible presence of proteases released by phytophagous bugs (e.g.,

Eurygaster,

Aelia, and particularly

Halyomorpha halys), which facilitate nutrient suction from the developing kernels by injecting protease-rich saliva [

53], the PDI measurement of the flours from the various treatments highlighted interesting effects. The bacterial treatment reduced protein degradation at both levels of nitrogen fertilization, a positive effect that deserves to be further investigated. Previous studies have shown that the degradation of durum wheat glutenins and gliadins have different dynamics concerning the flour incubation temperature, and that glutenins are probably also degraded by other substances released by bugs into grains [

54]. Our PDI results highlight lower protein degradation in bacteria-treated plots, probably due to the greater difficulty for protease enzymes to degrade larger protein subunits, and thus preserving the dough strength W.

Earlier studies on dough rheological properties and gluten quality demonstrated a significant correlation between dough extensibility and the gliadins/glutenins (GLI/GLU) ratio. In addition, HMW subunits have twice the effect on maximum dough resistance than LMW subunits [

55]. Based on this evidence, higher P/L was expected in treatments with the microbial biostimulant, given lower GLI/GLU and higher HMW/LMW ratios, with consequently lower dough extensibility and increased tenacity. This behavior was only observed at the reduced fertilization dose, with an increase in P/L in the "75%N + bact" treatment compared to the "75%N". According with this trend, the Brabender Farinograph analysis indicated an improved dough stability due to treatment with the bacterium, at both nitrogen levels.

From an economic perspective, the application of the inoculum does not require additional field machinery costs, as it could be applied along with the post-emergence weeding or fungicide treatments, in this way saving time and fuel costs. Although any possible interaction between the bacterium and pesticides requires to be preliminary investigated, at this time the cost-effectiveness would lie in the compensation point between the cost of the applied biostimulant with that of saved fertilizer following the inoculum application. This depends mainly on fertilizer prices, and recent raw material shortages have increased fertilizer prices, consequently making biostimulants more cost-effective. However, regardless of existing prices, the environmental benefits of decreased synthetic mineral fertilizer use, such as reduced nitrogen leaching following heavy rainfall, must be noted. In conditions of drought and difficulties for soil nutrient uptake, foliar spraying of effective microbial biostimulants should be considered as an additional agronomic benefit.

5. Conclusions

This study investigates the potential of Methylobacterium symbioticum under reduced nitrogen fertilization conditions to mitigate the environmental impacts of synthetic nitrogen use in wheat cultivation. It was observed improvements in certain physiological traits, notably under suboptimal nitrogen levels. This suggests that Methylobacterium symbioticum could partly substitute nitrogen fertilizers, potentially decreasing agriculture's reliance on synthetic inputs.

This monocyclic field trial indicates that foliar application of the microbial biostimulant product based on Methylobacterium symbioticum did not significantly impact the main agronomic parameters of wheat such as yield and grain protein content in a fertile soil of the Po plain in NE Italy. However, notable improvements were observed in the vegetational indices such as SPAD and NDVI, allowing for prolonged leaf greenness and stay green, especially under conditions of low nitrogen supply. These findings suggest a better nitrogen status in treated wheat, supported by improved physiological parameters related to plant photosynthesis and the ACC-deaminase activity of this bacterial strain.

Interestingly, this study indicates significant implications for wheat quality, with observed changes in gluten protein composition affecting dough rheological properties, although additional research is necessary to completely understand these effects and their implications for specific baked products requiring high dough tenacity and stability.

Given the specificity often observed in nature between the bacteria and plant host variety/species, future studies should examine the same strain on other wheat varieties and under varied environmental conditions. While this study did not assess nitrogen fixation, research should investigate this aspect under contrasting nitrogen regimes, which could reveal greater advantages with reduced fertilizer dosages, as documented in studies on maize and rice.

Considering the climate change and its associated plant stress, improved root colonization in the arable layer due to microbial inoculation may offer an additional benefit from plant inoculation with Methylobacterium symbioticum. Therefore, it is recommended to undertake trials under higher nitrogen deficiency and varied meteorological conditions to discover optimal inoculum-crop combinations, particularly in marginal areas or organic agriculture. The variability in the efficacy of PGPB treatments, particularly in nutrient-rich settings, underscores the necessity for tailored inoculum-crop combinations in various agricultural contexts.

In conclusion, while this study highlights the potential of Methylobacterium symbioticum as a sustainable agricultural technique, additional research and refinement are essential. Broadening research efforts to include a variety of environmental conditions and performing long-term studies over multiple seasons to evaluate the biostimulant's effectiveness and processes in agricultural settings is recommended. Detailed biochemical and molecular research is also required to elucidate the mechanisms underlying these effects, particularly concerning nitrogen metabolism.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.V. and Y.W.; methodology, F.B., A.P., G.B., F.V., S.P., V.B., G.V.; software, F.V.; validation, A.P., T.V. and F.V.; formal analysis, A.P., G.B., F.V.; investigation, F.V., A.P.; resources, T.V.; data curation, A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, F.V. and P.K.B.; writing—review and editing, T.V., Y.W. and A.P; visualization, F.V.; supervision, T.V.; project administration, T.V.; funding acquisition, T.V. and Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Leaf chlorophyll content (as SPAD values) and canopy greenness (NDVI) (mean ± S.E.; n = 3) in wheat under 100%N, 100%N + bact, 75%N and 75%N + bact treatments. Percentages: variation vs. reference treatment 100%N (Ref.). Letters: statistical comparison among treatments (Tukey test, P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 1.

Leaf chlorophyll content (as SPAD values) and canopy greenness (NDVI) (mean ± S.E.; n = 3) in wheat under 100%N, 100%N + bact, 75%N and 75%N + bact treatments. Percentages: variation vs. reference treatment 100%N (Ref.). Letters: statistical comparison among treatments (Tukey test, P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 2.

Photosynthetic parameters: CO2 assimilation rate (A), stomatal conductance (gsw), transpiration rate (Emm) and PSII efficiency (Fv'/Fm') (mean ± S.E.; n = 3) in wheat plants under 100%N, 100%N + bact, 75%N and 75%N + bact treatments. Percentages: variation vs. reference treatment 100%N (Ref.). Letters: statistical comparison among treatments (Tukey test, P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 2.

Photosynthetic parameters: CO2 assimilation rate (A), stomatal conductance (gsw), transpiration rate (Emm) and PSII efficiency (Fv'/Fm') (mean ± S.E.; n = 3) in wheat plants under 100%N, 100%N + bact, 75%N and 75%N + bact treatments. Percentages: variation vs. reference treatment 100%N (Ref.). Letters: statistical comparison among treatments (Tukey test, P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 3.

Root length density (RLD), root area density (RAD) and root diameter (mean; n = 3) in wheat plants under 100%N, 100%N + bact, 75%N and 75%N + bact treatments at various soil depths. Asterisk (*): statistically significant differences among treatments (Tukey test, P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 3.

Root length density (RLD), root area density (RAD) and root diameter (mean; n = 3) in wheat plants under 100%N, 100%N + bact, 75%N and 75%N + bact treatments at various soil depths. Asterisk (*): statistically significant differences among treatments (Tukey test, P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 4.

Qualitative characteristics of wheat grains: grain protein content (GPC), gliadins, glutenins, gliadins-to-glutenins ratio (GLI/GLU) and high-to-low molecular weight glutenin subunits ratio (HMW/LMW) (mean ± S.E.; n = 3) in wheat plants under 100%N, 100%N + bact, 75%N and 75%N + bact treatments. Percentages: variation vs. reference treatment 100%N (Ref.). Letters: statistical comparison among treatments (Tukey test, P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 4.

Qualitative characteristics of wheat grains: grain protein content (GPC), gliadins, glutenins, gliadins-to-glutenins ratio (GLI/GLU) and high-to-low molecular weight glutenin subunits ratio (HMW/LMW) (mean ± S.E.; n = 3) in wheat plants under 100%N, 100%N + bact, 75%N and 75%N + bact treatments. Percentages: variation vs. reference treatment 100%N (Ref.). Letters: statistical comparison among treatments (Tukey test, P ≤ 0.05).

Table 1.

Fertilization plan and distribution of biostimulant in each treatment.

Table 1.

Fertilization plan and distribution of biostimulant in each treatment.

| Treatment name |

N (kg ha-1) |

Bacterial inoculation |

| 100%N |

180 |

NO |

| 100%N + bact |

180 |

YES |

| 75%N |

130 |

NO |

| 75%N + bact |

130 |

YES |

Table 2.

Morphological parameters: plant height, uppermost internode length, LAI, LAI/CAI, shoot dry weight (DW) and leaf-to-culm dry weight ratio (DW) (mean ± S.E.; n = 3) in wheat plants under 100%N, 100%N + bact, 75%N and 75%N + bact treatments. In brackets: % variation vs. reference treatment 100%N. Letters: statistical comparison between the 4 different treatments (Tukey test, P ≤ 0.05).

Table 2.

Morphological parameters: plant height, uppermost internode length, LAI, LAI/CAI, shoot dry weight (DW) and leaf-to-culm dry weight ratio (DW) (mean ± S.E.; n = 3) in wheat plants under 100%N, 100%N + bact, 75%N and 75%N + bact treatments. In brackets: % variation vs. reference treatment 100%N. Letters: statistical comparison between the 4 different treatments (Tukey test, P ≤ 0.05).

| Treatment |

Plant height |

Uppermost internode length |

LAI |

LAI/CAI |

Shoot DW |

Leaf-to-Culm DW Ratio |

| cm |

%var/C |

cm |

%var/C |

m2 m-2

|

%var/C |

|

%var/C |

g m-2

|

%var/C |

|

%var/C |

| 100%N |

92.2 ± 1.8 |

a |

8.94 ± 0.65 |

a |

8.48 ± 1.00 |

a |

2.73 ± 0.10 |

a |

1,766.9 ± 194.4 |

a |

0.329 ± 0.016 |

a |

| 100%N + bact |

78.8 ± 1.2 |

c

(-15%) |

9.44 ± 0.61 |

a

(+6%) |

7.39 ± 0.52 |

a

(-13%) |

2.52 ± 0.04 |

a

(-8%) |

1,662.5 ± 124.1 |

a

(-6%) |

0.321 ± 0.004 |

ab

(-3%) |

| 75%N |

82.1 ± 1.7 |

bc

(-11%) |

9.66 ± 0.60 |

a

(+8%) |

7.98 ± 0.17 |

a

(-6%) |

2.53 ± 0.06 |

a

(-7%) |

1,770.2 ± 40.8 |

a

(+0.2%) |

0.289 ± 0.004 |

b

(-12%) |

| 75%N + bact |

86.5 ± 2.1 |

ab

(-6%) |

9.83 ± 0.68 |

a

(+10%) |

7.62 ± 0.96 |

a

(-10%) |

2.55 ± 0.10 |

a

(-6%) |

1,659.7 ± 176.1 |

a

(-6%) |

0.309 ± 0.005 |

ab

(-6%) |

Table 3.

Productivity parameters of wheat: grain yield, harvest index (HI), Thousand Seed Weight (TSW) and testing weight (mean ± S.E.; n = 3) in plants under 100%N, 100%N + bact, 75%N and 75%N + bact treatments. In brackets: % variation vs. reference treatment 100%N. Letters: statistical comparison among treatments (Tukey test, P ≤ 0.05).

Table 3.

Productivity parameters of wheat: grain yield, harvest index (HI), Thousand Seed Weight (TSW) and testing weight (mean ± S.E.; n = 3) in plants under 100%N, 100%N + bact, 75%N and 75%N + bact treatments. In brackets: % variation vs. reference treatment 100%N. Letters: statistical comparison among treatments (Tukey test, P ≤ 0.05).

| Treatments |

Grain yield |

HI |

TSW |

Testing weight |

| g m-2

|

%var/C |

% |

%var/C |

g |

%var/C |

kg hL-1

|

%var/C |

| 100%N |

1023.2 ± 40.9 |

a |

42.6 ± 0.55 |

a |

39.7 ± 0.44 |

a |

81.0 ± 0.29 |

a |

| 100%N + bact |

955.9 ± 43.0 |

a (-7%) |

42.0 ± 1.18 |

a (-2%) |

39.6 ± 0.88 |

a (-0.2%) |

80.7 ± 0.47 |

a (-0.4%) |

| 75%N |

946.5 ± 52.1 |

a (-8%) |

41.1 ± 1.00 |

a (-4%) |

39.6 ± 0.51 |

a (-0.4%) |

82.2 ± 0.52 |

a (+1%) |

| 75%N + bact |

958.9 ± 87.2 |

a (-6%) |

43.2 ± 0.81 |

a (+1%) |

39.0 ± 0.07 |

a (-2%) |

81.3 ± 0.41 |

a (+0.3%) |