1. Introduction

Sustainable fisheries practices are crucial for maintaining healthy marine ecosystems, ensuring long-term economic viability for fishing communities, and contributing to global food security (FAO, 2020). Unsustainable practices, however, can lead to overfishing, habitat destruction, and declining fish stocks, jeopardizing food security and livelihoods (Worm et al., 2009). Sustainable fisheries management offers a solution by balancing resource utilization with ecosystem health (Pikitch et al., 2004). The Gulf of Mannar, an inlet of the Indian Ocean, is situated between southeastern India and western Sri Lanka. This gulf is bordered to the northeast by Rameswaram Island, Adam’s (Rama’s) Bridge—a chain of shoals—and Mannar Island. The Indian port city of Tuticorin is located along the Gulf's coastline. Notably, the Gulf of Mannar is famous for its pearl banks and the presence of the sacred chank, a species of gastropod mollusks Gulf of Mannar, a UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve harbors rich coral reefs, seagrass meadows, and mangroves, providing critical habitat for fish populations and supporting coastal communities (CMFRI, 2019). However, it faces challenges like overfishing and habitat degradation. Understanding the social dimensions of sustainable fisheries is vital for effective management. Ecosystem health and fishing communities' well-being are closely related (Bennett et al., 2019). By examining these social dimensions, including gender dynamics and community-based management strategies, we can develop policies that balance ecological sustainability with socio-economic development (McClanahan et al., 2015).

1.1. Problem Statement

Fishing communities in Ramanathapuram and Thoothukudi face multiple challenges. Overfishing (Srinivasan et al., 2012), habitat degradation (Vivekanandan et al., 2005), and climate change (Hernández et al., 2015) threaten fish stocks, the mainstay of their livelihoods. Limited resources and socioeconomic factors, such as inadequate access to capital, education, and health services, as well as market limitations and policy constraints (Bavinck et al., 2014) further exacerbate these issues. Gender disparities, where women often have less access to resources and decision-making power, add another layer of complexity (Salagrama, 2015). Understanding the social dimensions of sustainable fisheries is crucial. Ecosystem services (MEA, 2005) like fish stocks and coastal protection are vital for these communities. However, the link between these services and well-being aspects like income and social cohesion remains underexplored. This research aims to quantify these interactions using econometric models (Barbier, 2017) to inform policy and sustainable management practices. Sustainable fisheries management requires a comprehensive approach. While fish stocks are critical, the social dimension is equally important. Fishing communities are linked to the ecosystem, and their well-being and knowledge are essential for effective resource management (Jentoft, 1998). Studying the social dimensions involves examining economic, social, and health well-being, understanding gender dynamics, and analyzing community-based management strategies (McCay, 2002). This holistic approach ensures both ecological and social sustainability are prioritized.

1.2. Research Objectives

This research aims to bridge the knowledge gap by investigating two primary questions: How do ecosystem services, impacted by ecosystem health, influence the livelihoods of local communities in the Gulf of Mannar? and what are the interactions between ecosystem services and human well-being in these regions, considering factors such as economic security, health, and social cohesion? This study will quantify the dependence of these communities on various services, such as fish stocks and coastal protection, for their livelihoods and basic needs (Costanza et al., 1997). Furthermore, we explored the intricate relationships between these services and different aspects of well-being, including economic security, health, and social cohesion (MEA, 2005). By employing a quantitative approach, this research will shed light on the socio-ecological dynamics of the Gulf of Mannar fisheries. The research delves deeper by examining gender roles within these communities, specifically how gender influences access to resources and decision-making processes. Additionally, the effectiveness of community-based management strategies will be assessed, a crucial factor for the long-term sustainability of the ecosystem and local livelihoods (Berkes et al., 2001; Ostrom, 1990). This comprehensive understanding of the social and ecological dynamics will provide a foundation for informed policy and sustainable management practices in the Gulf of Mannar.

2. Description of Study Area

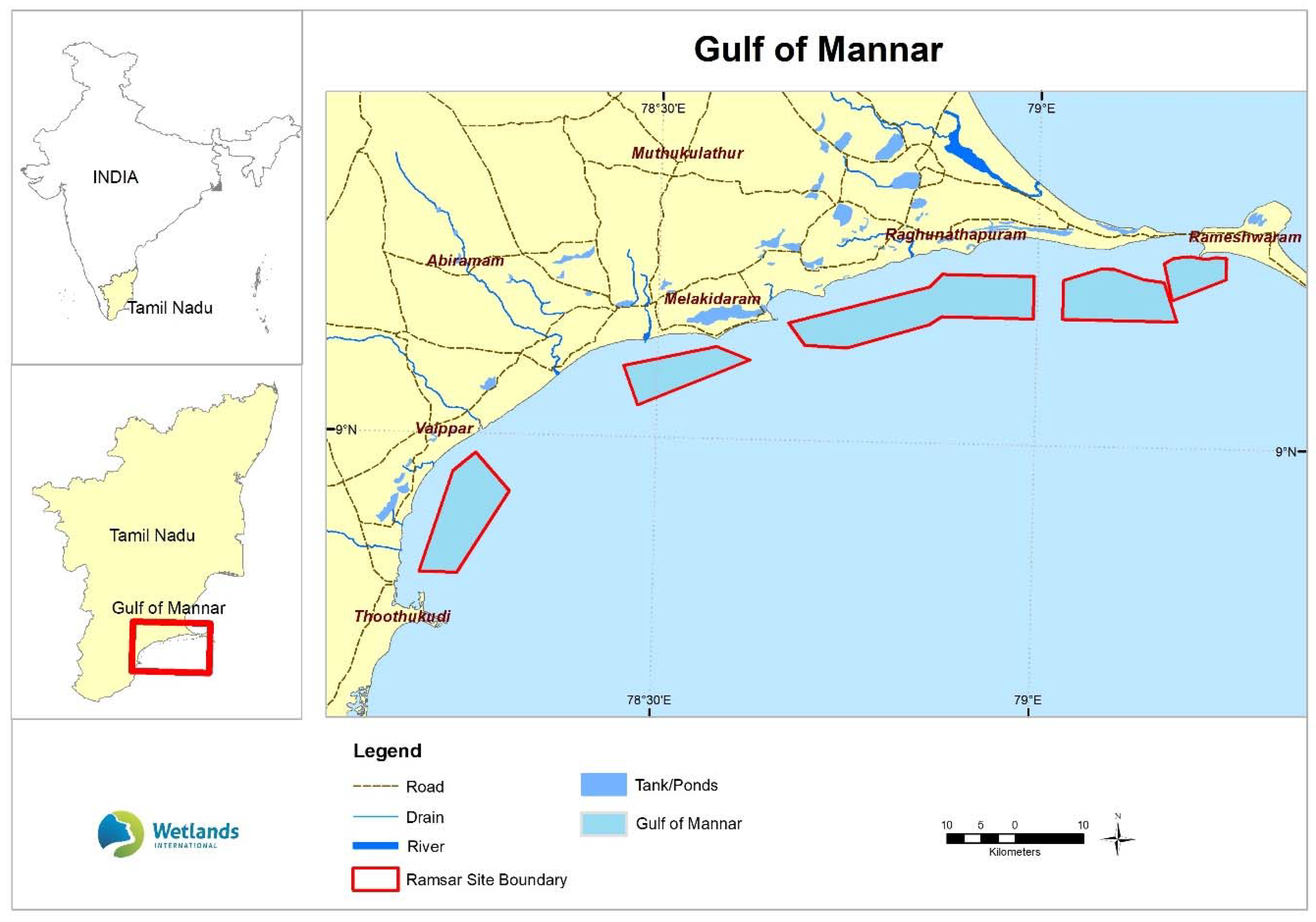

The Gulf of Mannar, situated between the southeastern tip of India and the west coast of Sri Lanka, is a shallow bay forming part of the Laccadive Sea in the Indian Ocean, covering an area of about 10,500 square kilometers (Nammalwar et al., 2002). This unique marine ecosystem, designated as a UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve, includes island, mangrove, seagrass, and coral reef ecosystems. It supports a rich biodiversity, hosting over 4,000 species of flora and fauna (UNESCO, 2023; Venkataraman et al., 2015). The Gulf of Mannar Marine National Park spans 560 square kilometers. It comprises 21 small islands along the Tamil Nadu coast, extending from Rameswaram Island to Tuticorin, with the islands ranging from 0.95 to 130 hectares in size (UNESCO, 2023). These islands, surrounded by highly productive fringing and patchy coral reefs, serve as critical habitats for a variety of marine species, including sea cows that feed on the seagrass beds (Venkataraman et al., 2015). The Gulf of Mannar is a shared ecosystem between Sri Lanka and India, with the International Maritime Boundary Line (IMBL) cutting across it. This research focuses solely on the Indian side of the Gulf of Mannar, specifically examining the fishing communities in Ramanathapuram and Thoothukudi districts.

Figure 1.

Detailed Map of the Gulf of Mannar Islands (Tamil Nadu, India). Source: Ramsar Sites Information Service.

Figure 1.

Detailed Map of the Gulf of Mannar Islands (Tamil Nadu, India). Source: Ramsar Sites Information Service.

The socio-economic aspects of the Gulf of Mannar region are heavily influenced by these ecosystems. Ramanathapuram and Thoothukudi districts, located on the southeastern coast of Tamil Nadu, rely on the Gulf's marine resources for their livelihoods (Seal et al., 2023). Ramanathapuram's small-scale fisheries, facing declining fish stocks and limited access to modern technology (sonar, better vessels, storage) for efficient fishing (catches, safety, time), struggle against larger-scale competition and market limitations (quality, access), (Bavinck & Karunaharan, 2006). In contrast, Thoothukudi, an industrial hub and major port city, has a more mechanized fishing sector that is pressured by pollution and overfishing (Edward et al., 2021). The intricate connection between the health of marine ecosystems and the socio-economic conditions of these coastal communities underscores the importance of sustainable fisheries management. Fishing communities in Ramanathapuram and Thoothukudi rely on ecosystem services for food security, economic stability, and cultural practices (Salim et al., 2013). Understanding the interactions between ecosystem services and human well-being in these districts is essential for developing strategies that support both ecological conservation and community livelihoods (Vivekanandan et al., 2005).

2.1. Demographic Profile

Fishing is the primary economic activity, with Ramanathapuram characterized by small-scale fisheries and trawlers and Thoothukudi featuring a more industrialized sector, supported by a major port. While both districts benefit from aquaculture, concerns about sustainability and social equity arise. Traditional gender roles persist, with men mainly engaged in fishing and women in post-harvest activities, yet women's contributions are often undervalued. Social structures, including caste dynamics, influence access to resources and economic opportunities, though Thoothukudi's urbanization presents slightly different dynamics. Understanding these socio-economic complexities is crucial for sustainable management strategies. Access to education and healthcare services varies across the districts, with coastal communities often facing challenges. In Ramanathapuram, lower literacy rates and limited educational facilities hinder socio-economic development, particularly among fishing families. Thoothukudi fares better in terms of educational infrastructure, but disparities remain, especially in rural and coastal areas.

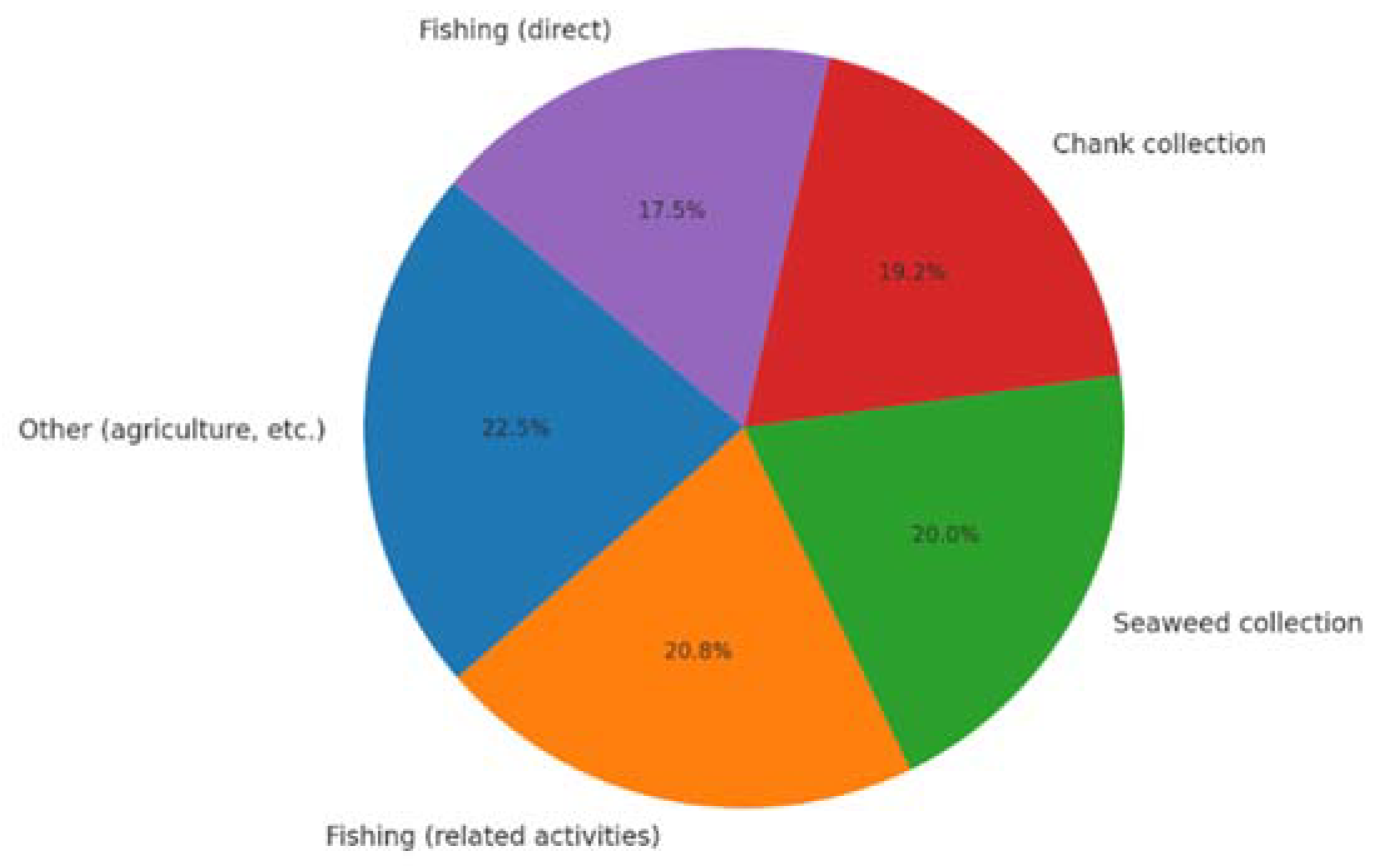

The Gulf of Mannar region relies heavily on a variety of livelihood activities, with fishing being the dominant force. Ramanathapuram is characterized by small-scale fisheries using traditional methods and trawlers, while Thoothukudi boasts a more industrialized sector supported by a major port. Direct fishing is the primary activity for men, but women play a crucial role in post-harvest activities like sorting, drying, and selling the catch. Aquaculture, or fish farming, also contributes to the economy in both districts, though concerns exist about its long-term sustainability and equitable distribution of benefits. Seaweed collection is another source of income, particularly for women. Traditional gender roles persist, with social structures and caste dynamics influencing access to resources and economic opportunities. Educational disparities exist, particularly in Ramanathapuram's coastal communities, highlighting the need for sustainable management strategies that consider these socio-economic complexities.

Figure 2.

Different livelihood activities pursued by fishing communities in Ramanathapuram and Thoothukudi. Source: Primary survey data

Figure 2.

Different livelihood activities pursued by fishing communities in Ramanathapuram and Thoothukudi. Source: Primary survey data

2.2. Socio-Economic Profile

The Gulf of Mannar, renowned for its rich marine biodiversity, has faced significant ecological degradation due to human activities by local fishing communities, particularly in the past. Historically, practices like coral removal for lime production caused extensive damage to coral reefs. Today, regulations and awareness play a crucial role in protecting this fragile ecosystem. The coastal villages in Ramanathapuram and Thoothukudi districts rely predominantly on fishing, as agricultural activities remain unproductive. The economic conditions are dire, with many living below the poverty line, lacking adequate water supply, medical care, and reliable power (Magesh et al., 2019). These challenges contribute to low productivity, improper marketing systems, and a lack of additional vocations, resulting in a low standard of living and chronic debt among fishermen. Fishing remains the primary economic activity, with 47 fishing villages—38 in Ramanathapuram and 9 in Thoothukudi—depending solely on it for livelihood. Gulf of Mannar's fishing sector utilizes a mix of traditional and modern vessels. While mechanized FRP, Vallam, and Vathai boats dominate the small-scale sector, some artisanal fishers rely on innovative thermocol sheet boats for near-shore activities. However, traditional crafts like catamarans, masula boats, vatti, and vallam persist alongside nearly 500 mechanized boats, highlighting the need for regulations to address the potential damage certain gears used on these vessels can cause to coral reefs (Rajagopalan, 2008). However, destructive fishing methods, such as illegal pair trawling, increase seawater turbidity and damage breeding grounds, further depleting marine resources (Kumaraguru et al., 2000).

Seaweed collection, another vital economic activity, involves more than 1000 fishermen and 450 fisherwomen, primarily harvesting around the 21 islands in the Gulf of Mannar. The seaweeds are crucial for agar and algin industries and are also used for human consumption and as fertilizer (Kaliyaperumal, 2013). Despite their economic importance, over-exploitation of seaweeds affects coral reef ecosystems due to increased siltation. Agriculture is limited but includes coconut and other food crops. Areas like Thoothukudi, Keelakkarai, and Mandapam practice coconut and Palmyra plantation, while floriculture is noted in some northern regions. These activities, coupled with the socioeconomic conditions, significantly impact coastal ecosystems, particularly coral reefs.

3. Methodology

3.1. Survey and Data Collection

To investigate the social dimensions of fisheries and the role of ecosystem services in the Gulf of Mannar, a quantitative survey approach was employed. A stratified random sampling technique ensured representativeness across various fishing communities in Ramanathapuram and Thoothukudi districts. The population was stratified based on village size and type of fishing activity (traditional vs. modern). From each stratum, villages were randomly selected, and within these villages, households were randomly chosen for participation, resulting in a final sample size of 480 respondents. The primary data collection tool was a structured questionnaire, which was translated into the local language for better comprehension and pre-tested with a small sample to ensure clarity, validity, and reliability. Key sections of the questionnaire addressed demographics (age, gender, education level, household size), livelihood and well-being (income sources, food security, health status), fishing activities (participation levels of men and women, gear types used, catch composition), ecosystem services (dependence on fish stocks, coastal protection, other services), and community management (involvement in community-based management strategies, perceptions of effectiveness). Data collection occurred during the two months, of April and May 2024, covering approximately 60 villages. Trained field researchers administered the surveys to consenting participants, ensuring anonymity and confidentiality throughout the process. Ethical considerations were paramount; informed consent was obtained from all participants before data collection, detailing the study's purpose, the voluntary nature of participation, and assurances of confidentiality.

To identify and assess coastal ecosystem services (CES) in the Gulf of Mannar, we reviewed scientific literature and reports on the region's ecosystems. We adapted a CES assessment framework to the specific context and refined service definitions for clarity. Based on this review, we compiled a list of potential CES (fish capture, water purification, etc.) and assigned importance scores based on the gathered information. Finally, we analyzed the data to understand the relative importance and distribution of CES within the Gulf of Mannar

3.2. Statistical Techniques

In this research, Python was employed for data analysis and the creation of major visualizations, involving steps such as data preparation, descriptive analysis, and econometric modeling. During the data cleaning and organization phase, we checked for missing values and outliers to ensure data integrity, followed by the creation of a codebook detailing each variable, its type, and its scale of measurement. We identified dependent variables including well-being indicators (e.g., household income, health status, educational attainment, and access to services), gender dynamics (e.g., participation rates in fishing activities and income disparity), and community-based management outcomes (e.g., participation in decision-making and perceived benefits). Independent variables comprised demographic factors (e.g., age, education, household size), economic factors (e.g., income, occupation), social factors (e.g., community engagement, gender roles), and environmental factors (e.g., access to resources, ecological health indicators).

For descriptive analysis, we calculated summary statistics such as the mean, median, standard deviation, and range for continuous variables, and analyzed frequency distributions for categorical variables. Additionally, cross-tabulations were conducted to examine relationships between categorical variables, such as gender and participation in community management, providing insights into the socio-ecological dynamics within the study area. This comprehensive approach allowed us to effectively assess the interactions between ecosystem services and human well-being in the Gulf of Mannar.

3.2.1. Multiple Regression Analysis:

It is employed to understand the impact of various factors on well-being. The model used is

3.2.2. Logistic Regression:

It analyzes the interaction between ecosystem services and a specific aspect of well-being in the Gulf of Mannar:

4. Results and Discussion

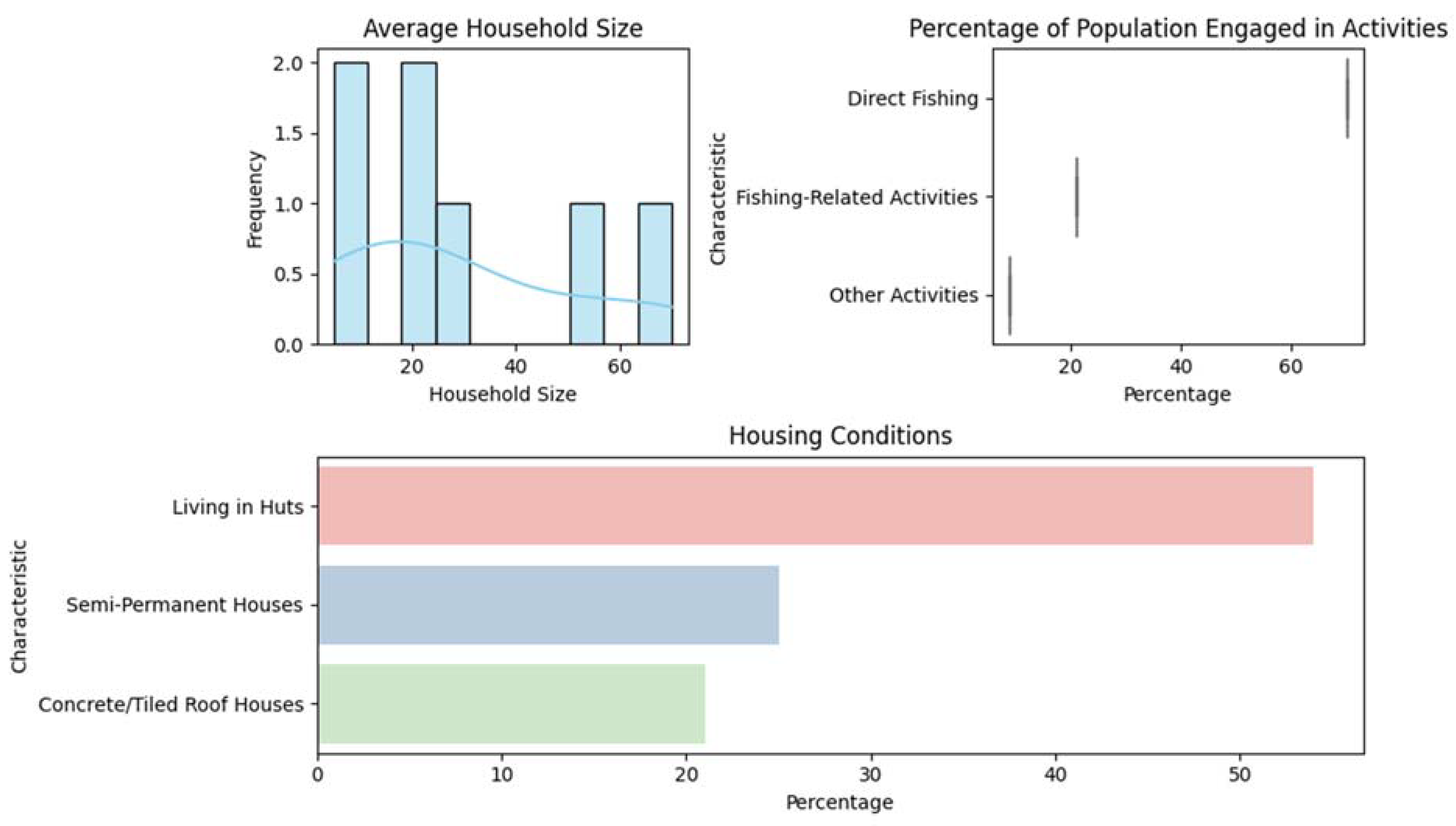

The Gulf of Mannar's coastal communities exhibit a profound reliance on the health of their surrounding ecosystem. Fishing dominates their economic landscape, directly employing around 65% of the workforce and encompassing a wider network of related activities (20%). Seaweed collection (2%) and even seemingly separate activities like agriculture (18.8%) and firewood collection further illustrate the intricate link between human well-being and the environment. However, this dependence presents a double-edged sword. While the ecosystem serves as a vital source of income through fishing, seaweed, and potentially other resources like chank collection, unsustainable practices can jeopardize these very resources. The precarious housing conditions faced by over half of the fisherfolk living in huts highlights existing vulnerabilities. This underscores the critical need for sustainable resource management. Striking a balance between ecological health and economic well-being is essential for ensuring the long-term prosperity of these coastal communities.

Figure 3.

Illustrations provide insight into the demographic, socioeconomic, and housing conditions of the coastal communities in the study area.

Figure 3.

Illustrations provide insight into the demographic, socioeconomic, and housing conditions of the coastal communities in the study area.

This research explores the livelihoods of coastal communities in the Gulf of Mannar, where fishing is the primary occupation for nearly 60% of the population. While men dominate fishing at sea, women play a vital but undervalued role in pre and post-harvest activities. Unequal access to resources and decision-making power limit women's economic potential and influence on policies impacting their lives. This gender disparity weakens household dynamics and community resilience, hindering sustainable fishing practices. Integrating women's perspectives is crucial for equitable policies and long-term environmental well-being. To assess well-being, the study employs standardized measures like household size, income, and dependence on fisheries and ecosystems. This ensures all factors contribute equally to the analysis despite differing units. Additionally, the research addresses potential biases in the data by removing redundant variables to achieve clear and meaningful results.

A multiple regression analysis was conducted on the Gulf of Mannar households' well-being using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression. The analysis revealed household size and assets as significant predictors. Larger households negatively impacted well-being scores (p-value = 0.026), while higher asset scores had a positive influence (p-value = 0.000), emphasizing the importance of material security. However, education, fishery dependency, mangrove dependency, seagrass dependency, fisheries harvest, income, and consumption showed no significant impacts on well-being, suggesting potential data or model limitations (Jones & Brown, 2019). The model explains about 20.4% of well-being score variation (R-squared = 0.204), indicating the need for additional relevant variables. Despite this, the overall model is statistically significant (F-statistic p-value = 7.82e-09).

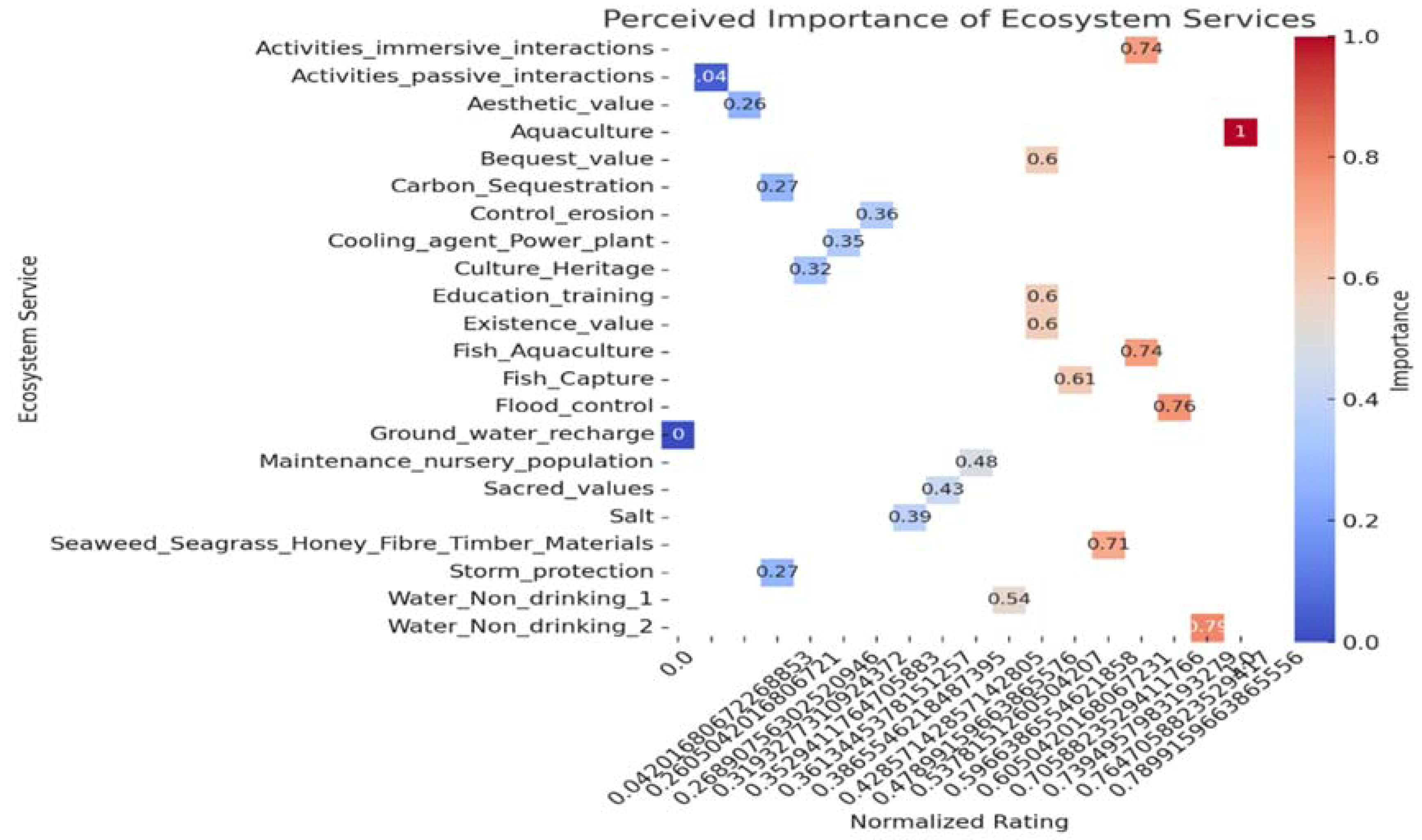

Analyzing valuations of Gulf of Mannar's ecosystem services (

Table 1) revealed its multifaceted importance. Economic activities like fish capture and aquaculture scored highly, reflecting dependence on the ecosystem. Likewise, high scores for water resources highlighted their crucial role. Interestingly, the data suggests an understanding of the ecosystem's contribution to public health (flood control, water quality) and social cohesion (cultural heritage, sacred values). Even non-monetary values like beauty and existence value were recognized. This data emphasizes the strong link between a healthy Gulf of Mannar and the well-being of local communities. Future research combining qualitative methods with economic models could offer a deeper understanding of these interdependencies, informing sustainable management strategies. To ensure accuracy, we employed model correction techniques to improve data representation and address potential biases. By analyzing model coefficients, we identified key factors influencing participation decisions in these communities. While this analysis provides valuable insights, further exploration and model optimization can lead to a more comprehensive understanding of these decision-making processes.

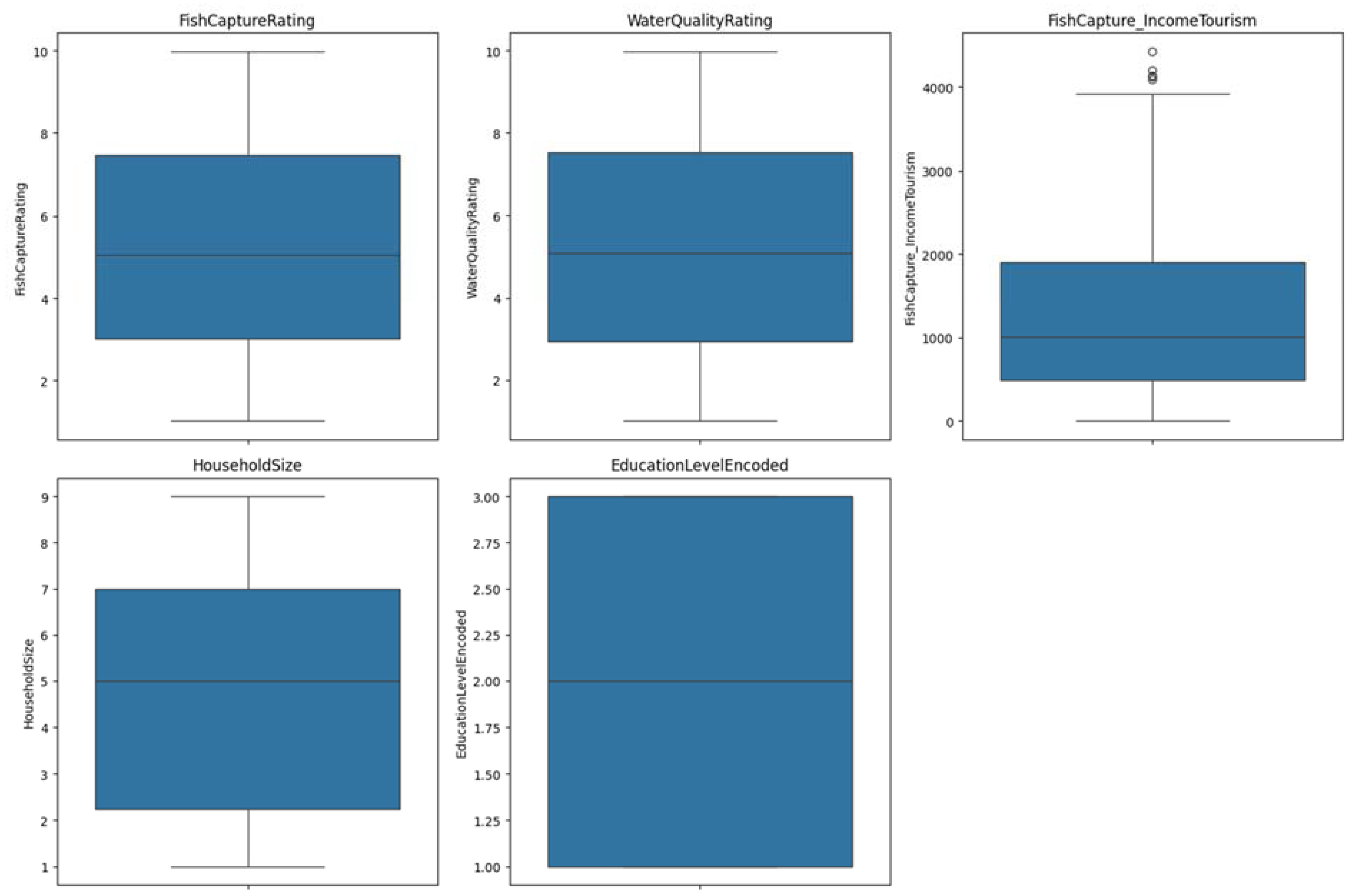

The logistic regression analysis aimed to predict food security status in the Gulf of Mannar region using several predictors: Fish Capture Rating, Water Quality Rating, an interaction term (Fish Capture * Income from Tourism), Household Size, and Education Level. However, the model's pseudo R-squared value of 0.008 suggests it explains little variability in food security. None of the predictors—including Household Size, which showed marginal significance—were statistically significant at the conventional 0.05 level, indicating they do not reliably predict food security status. Possible reasons for these findings include the complexity of socio-economic and environmental interactions not fully captured by the chosen predictors, potential data limitations, missing influential variables like income or health factors, and measurement issues in variable categorization.

Figure 4.

Scatter Plots of Fish Capture Rating, Water Quality Rating, Fish Capture Income and Tourism by Household Size and Education Level

Figure 4.

Scatter Plots of Fish Capture Rating, Water Quality Rating, Fish Capture Income and Tourism by Household Size and Education Level

Figure 5.

Community Perception of Ecosystem Services (based on primary survey).

Figure 5.

Community Perception of Ecosystem Services (based on primary survey).

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

The Gulf of Mannar communities rely heavily on the ecosystem for their well-being, with fishing being the dominant economic activity (65% employed directly, 20% in related activities). However, unsustainable practices threaten these resources. The well-being analysis highlights household size and assets as significant factors, with larger households having lower well-being scores. The model requires further refinement to incorporate additional relevant variables for a more comprehensive understanding. Sustainable management of the Gulf of Mannar's resources requires a multifaceted approach. Diversifying livelihoods (seaweed farming, ecotourism) can reduce pressure on fish stocks while promoting economic sustainability. Community-based Management (CBM) empowers local communities, fostering resource ownership and encouraging sustainable fishing practices. Capacity building through training and resources is crucial for effective community participation.

Future research should focus on expanding data collection, enhancing feature engineering to capture nuanced socio-ecological dynamics, employing multivariate techniques like SEM, and integrating qualitative insights to provide a more comprehensive understanding of food security determinants in the Gulf of Mannar region. Regulatory measures, including bans on deforestation, shell collection, coral mining, and stringent controls on trawl boat operations and industrial effluents, are necessary to mitigate environmental degradation. Promoting sustainable development through responsible tourism, population growth control, and urban planning, while adhering to Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) rules, ensures integrated development aligned with environmental protection goals. These integrated strategies aim to enhance social equity, conserve ecological integrity, and promote economic sustainability for the long-term well-being of Gulf of Mannar communities.

References

- Barbier, E. B. (2017). Marine ecosystem services. Current Biology, 27(11), R507-R510.

- Bavinck, M., Sowman, M., & Menon, A. (2014). Theorizing participatory governance in contexts of legal pluralism–a conceptual reconnaissance of fishing conflicts and their resolution. Conflicts over Natural Resources in the Global South–Conceptual Approaches, 147.

- Bavinck, J. M., & Karunaharan, K. (2006). Legal pluralism in the marine fisheries of Ramnad District, Tamil Nadu, India. Indian Institute of Social Science Research (ICSSR)..

- Berkes, F., Mahon, R., McConney, P., Pollnac, R., & Pomeroy, R. (2001). Managing small-scale fisheries. Alternative directions and methods. Ottawa: IDRC.

- Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge.

- CMFRI (Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute). (2019). Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve. Retrieved from https://www.cmfri.org.in/division/fishery-enviornment.

- Costanza, R., d'Arge, R., De Groot, R., Farber, S., Grasso, M., Hannon, B.,... & Van Den Belt, M. (1997). The value of the world's ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature, 387(6630), 253-260.

- Census of India. (2011). District Census Handbook: Ramanathapuram and Thoothukudi. Government of India.

- Edward, J. P., Jayanthi, M., Malleshappa, H., Jeyasanta, K. I., Laju, R. L., Patterson, J.,... & Grimsditch, G. (2021). COVID-19 lockdown improved the health of coastal environment and enhanced the population of reef-fish. Marine pollution bulletin, 165, 112124. [CrossRef]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). (2020). The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2020: Sustainability in action. https://doi.org/10.4060/ca9229en.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). (2022). The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2022. FAO, Rome. https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/a2090042-8cda-4f35-9881-16f6302ce757/content.

- Hernández-Delgado, E. A. (2015). The emerging threats of climate change on tropical coastal ecosystem services, public health, local economies and livelihood sustainability of small islands: Cumulative impacts and synergies. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 101(1), 5-28. [CrossRef]

- Jentoft, S., McCay, B. J., & Wilson, D. C. (1998). Social theory and fisheries co-management. Marine Policy, 22(4-5), 423-436. [CrossRef]

- Kumaraguru, A. K., Kannan, R., Sundaramahalingam, A., & Ramakritinan, C. M. (2000). Studies on socioeconomics of Coral Reef resource users in the Gulf of Mannar coast, South India. Final report, Centre for Marine and Coastal Studies, Madurai Kamaraj University, Madurai, 1-163.

- Magesh, N. S., & Krishnakumar, S. (2019). The Gulf of Mannar marine biosphere reserve, southern India. In World seas: an environmental evaluation (pp. 169-184). Academic Press.

- MEA (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment). (2005). Ecosystems and human well-being: Synthesis. Island Press.

- McCay, B. J. (2002). Emergence of institutions for the commons: Contexts, situations, and events. The drama of the commons, 361-402.

- McClanahan, T., Allison, E. H., & Cinner, J. E. (2015). Managing fisheries for human and food security. Fish and Fisheries, 16(1), 78-103. [CrossRef]

- Nammalwar, P., & Joseph, V. E. (2002). Bibliography of the Gulf of Mannar. CMFRI Special Publication, 74, 1-204.

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press.

- Pauly, D., & Zeller, D. (2016). Catch reconstructions reveal that global marine fisheries catches are higher than reported and declining. Nature Communications, 7, 10244. [CrossRef]

- Pikitch, E. K., Santora, C., Babcock, E. A., Bakun, A., Bonilla, R., Borja, A.,... & Sainsbury, K. J. (2004). Ecosystem-based fishery management. Science, 303(5657), 346-347.

- Salagrama, V. (2015). Climate change and fisheries: Perspectives from small-scale fishing communities in India on measures to protect life and livelihoods. International Collective in Support of Fishworkers (ICSF).

- Sampath, V. ALTERNATIVE LIVELIHOOD OPTIONS FOR COASTAL COMMUNITY IN THE GULF OF MANNAR BIOSPHERE RESERVE. p1y eV~~.

- Salim, S. S., Sathiadhas, R., Narayanakumar, R., Katiha, P. K., Krishnan, M., Biradar, R. S.,... & Kumar, B. G. (2013). Rural livelihood security: Assessment of fishers' social status in India.

- Seal, S., Iyer, S., Ghaneker, C., Prabakaran, N., & Johnson, J. A. (2023). Seagrass and Seaweed habitats in Gulf of Mannar and south Palk Bay region (p. 5). Final Technical Report, Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun. 17p.

- Srinivasan, U. T., Cheung, W. W., Watson, R., & Sumaila, U. R. (2012). Global fisheries losses at the exclusive economic zone level, 1950 to present. Marine Policy, 36(2), 544-549. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2023). Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve, India. UNESCO MAB Biosphere Reserves Directory. https://www.unesco.org/en/mab/gulf-mannar.

- Venkataraman, K., & Raghunathan, C. (2015). Coastal and marine biodiversity of India. In Marine faunal diversity in India (pp. 303-348). Academic Press.

- Vivekanandan, E., Srinath, M., & Kuriakose, S. (2005). Fishing the marine food web along the Indian coast. Fisheries research, 72(2-3), 241-252. 10.1016/j.fishres.2004.10.009.

- Worm, B., Barbier, E. B., Beaumont, N., Duffy, J. E., Folke, C., Halpern, B. S.,... & Watson, R. (2009). Rebuilding global fisheries. Science, 325(5940), 578-585.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).