1. Introduction

Patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) commonly experience electrolyte disturbances, which can present as abnormalities in sodium, potassium, chloride and calcium levels, among others. Changes in serum sodium levels are the most common and critical electrolyte abnormality, with both hyponatremia and hypernatremia being possible manifestations [

1]. Hypernatremia, affecting 16% to 40% of TBI patients, typically manifests within the initial days post-injury due to factors like diabetes insipidus, hyperosmolar therapy, dehydration, and iatrogenic causes, and is associated with higher mortality and longer hospital stays [

2,

3,

4]. Hyponatremia, affecting about 13.2% of TBI patients, often arises from the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, or cerebral salt-wasting syndrome within the first week, with higher risk linked to severe injury, low Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores, cerebral edema, or basal skull fractures [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

Hyperkalemia affects 17.77% of TBI patients and often arises during the initial resuscitative period, with a period prevalence of 29% within the first 12 hours after admission in patients with non-crush trauma [

1,

10]. This condition may follow an initial phase of hypokalemia and primarily results from catecholamine release, blood product transfusions, pharmacological agents such as succinylcholine, acidosis, and tissue ischemia [

11,

12,

13]. Hypokalemia usually appears immediately after injury and peaks within the first few days, primarily resulting from catecholamine-induced potassium shifts, renal potassium loss, fluid deficits, and hypothermia. Younger patients and those with severe injuries are especially vulnerable, facing additional complications and increased mortality [

11,

13,

14,

15,

16].

Calcium and chloride disturbances are also significant in TBI. Hypercalcemia can result from prolonged immobility or worsen with underlying hyperparathyroidism [

17,

18]. Hypocalcemia, common early post-injury and exacerbated by transfusions, is linked to severe coagulopathy and higher mortality, requiring careful management [

19,

20,

21]. Hyperchloremia can develop acutely within the initial days post-TBI, coinciding with the hyperemia phase (days 1-3) marked by increased cerebral blood flow and decreased arterio-jugular venous oxygen differences [

22,

23]. Hypochloremia has also been proved to occur in severe TBI cases and appears to be associated with increased mortality [

24].

Electrolyte changes are crucial when treating patients with TBI. Although some studies have focused on these changes and the mechanisms through which they occur, there is a notable lack of data regarding changes within the first 24 hours post-injury. Our study aims to provide essential information on this aspect, contributing to the scientific knowledge that can enhance the treatment and outcomes for these patients.

2. Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study involved 50 patients admitted for TBI at the Emergency Hospital “Prof. Dr. Nicolae Oblu” in Iași. Patients with a history of diabetes mellitus, thyroid or adrenal dysfunctions, recent trauma (within the last six months), or disorders/injuries of the hypothalamus or pituitary gland were excluded. Exclusion criteria further encompassed underage, pregnant patients, and those with severe anemia defined by hemoglobin levels under 8 g/dL.

Data on electrolyte levels (sodium, potassium, ionized calcium, chloride) within the first 24 hours post-admission were collected from medical charts. All blood samples were processed identically in the laboratory of the Emergency Hospital “Prof. Dr. Nicolae Oblu” using standard procedures. Normal electrolyte levels, as defined by the hospital’s laboratory, are 136–145 mmol/L for sodium, 3.5–5.1 mmol/L for potassium, 1.15–1.33 mmol/L for ionized calcium, and 98–107 mmol/L for chloride. Additional data, including demographic details, trauma mechanism, GCS scores, imaging results, and surgical needs, were extracted from medical records. Trauma mechanisms were categorized as unknown, falls from the same level, falls from a height, traffic accidents, aggression, and others. Imaging findings were assessed for basal skull fractures, other skull fractures, subdural hematomas, epidural hematomas, subarachnoid hemorrhages, cerebral hemorrhages, and diffuse axonal injury. TBI severity was categorized by GCS scores: mild (GCS 13-15), moderate (GCS 9-12), and severe (GCS 3-8).

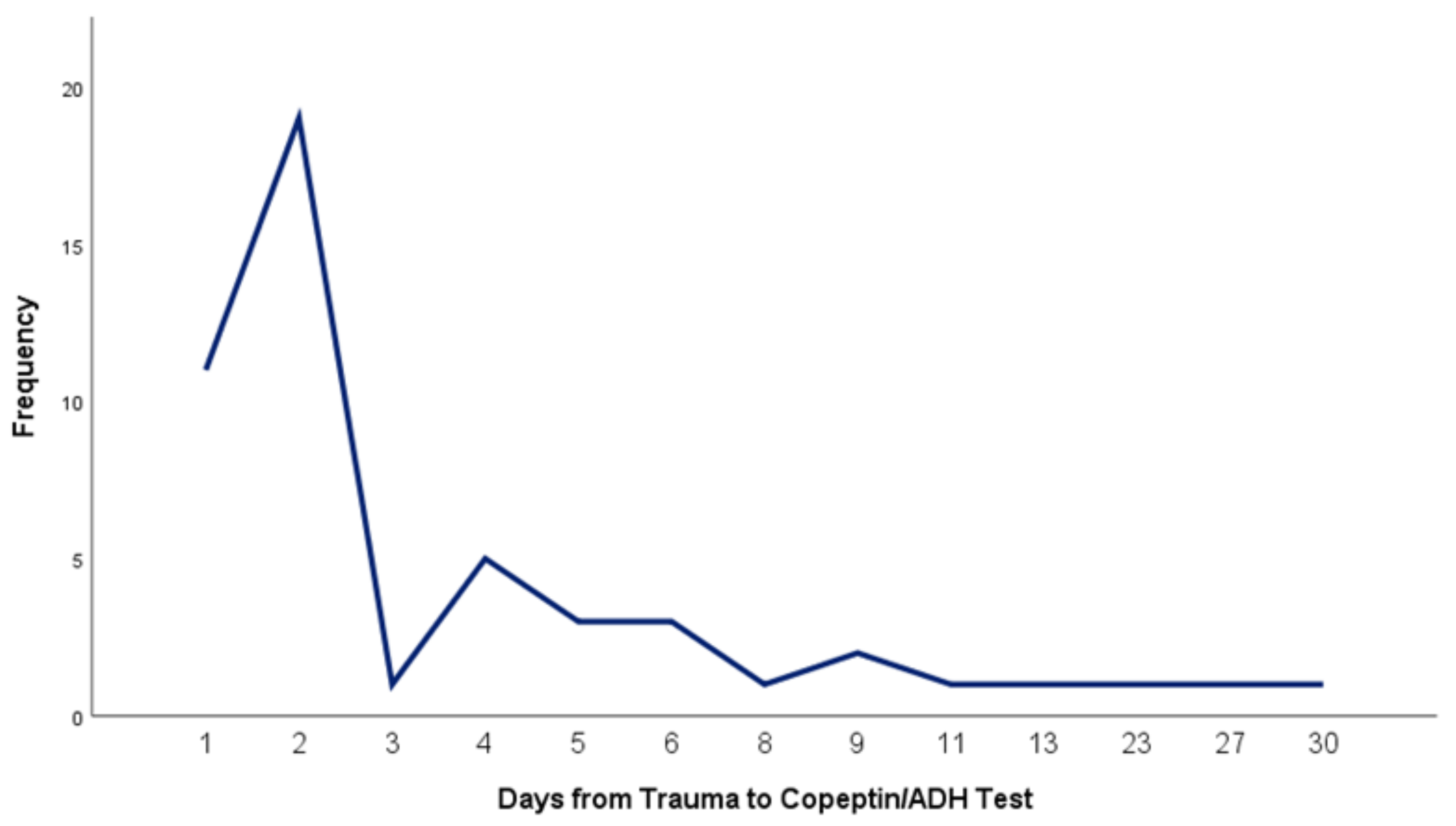

Copeptin and antidiuretic hormone (ADH) levels were measured once for each patient at varying intervals from the time of injury up to 30 days post-trauma (

Figure 1). Blood samples were collected using BD Vacutainer® CAT tubes and processed at Praxis Medical Laboratory Iași. Samples were centrifuged (1,000 x g for 20 minutes) and stored according to protocol until all participants were enrolled, after which assays were performed. ADH and copeptin levels in serum were measured using sandwich enzyme immunoassay kits.

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). To identify associations between variables, Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients, One-Way ANOVA, Mann-Whitney U test, Q-Q Plot, and Shapiro-Wilk test were utilized, with significance set at p < 0.05. The study received ethical approval from the local committees of the Emergency Hospital “Prof. Dr. Nicolae Oblu” Iași (4281/10.03.2020) and “Grigore T. Popa” University of Medicine and Pharmacy Iași (14/5.10.2020).

3. Results

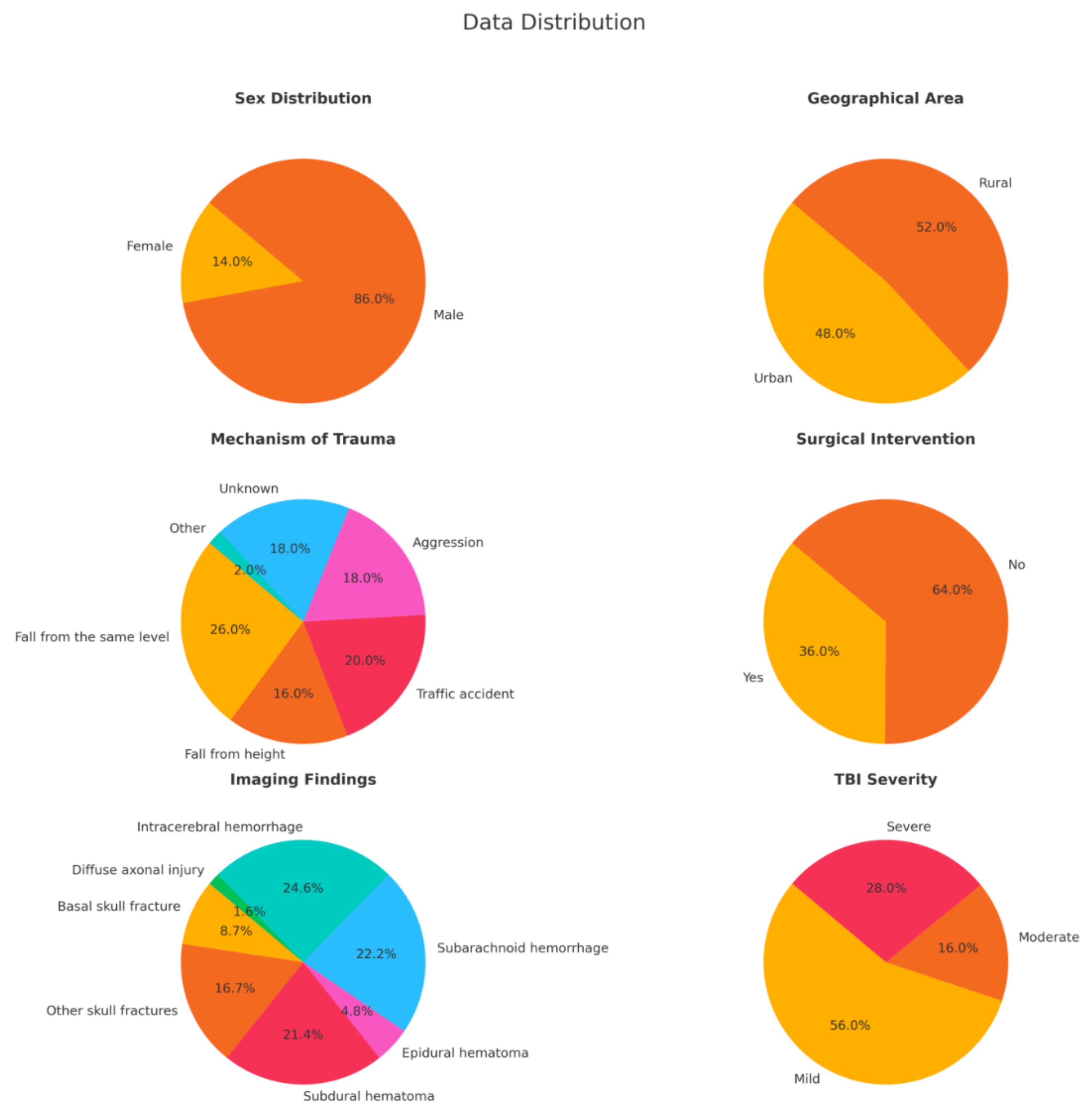

Among the 50 patients included in the study, 43 (86%) were male and 7 (14%) were female, with a mean age of 51.48 years, ranging from 18 to 86 years.

Figure 2 provides a summary of the key characteristics of the study population.

The mean levels of electrolytes were as follows: sodium was 138.5 mmol/L (median = 139.6 mmol/L, range = 113.6 – 145.7 mmol/L), potassium was 3.90 mmol/L (median = 3.88 mmol/L, range = 2.90 – 5.10 mmol/L), ionized calcium was 1.03 mmol/L (median = 1.04 mmol/L, range = 0.84 – 1.21 mmol/L), and chloride was 104.53 mmol/L (median = 105.4 mmol/L, range = 80.3 – 114.5 mmol/L). The Shapiro-Wilk test and Q-Q Plots confirmed a normal distribution for all these electrolytes (

Figure 3). The median values show that, except for chloride, the electrolyte levels tended to be at the lower end of the normal range. Pearson correlation analysis revealed no significant correlation between electrolyte levels and geographic area for sodium (p = 0.675; urban mean = 138.1 mmol/L, rural mean = 138.8 mmol/L), potassium (p = 0.910; urban mean = 3.91 mmol/L, rural mean = 3.90 mmol/L), ionized calcium (p = 0.914; urban mean = 1.04 mmol/L, rural mean = 1.03 mmol/L), and chloride (p = 0.170; urban mean = 103.10 mmol/L, rural mean = 106.06 mmol/L).

No significant association was found between sex and sodium levels (p = 0.675, mean for males = 138.52 mmol/L, mean for females = 138.54 mmol/L), ionized calcium levels (p = 0.914, mean for males = 1.03 mmol/L, mean for females = 1.04 mmol/L), or chloride levels (p = 0.407, mean for males = 104.15 mmol/L, mean for females = 106.65 mmol/L). However, Pearson analysis showed a possible correlation between sex and potassium levels in our study group (p= 0.016, mean for males = 3.985, mean for females = 3.511 mmol/L). One-Way ANOVA revealed no significant association between the mechanism of trauma and electrolyte levels for sodium (F = 1.267, p = 0.343), potassium (F = 0.291, p = 0.915), ionized calcium (F = 0.275, p = 0.924), and chloride (F = 1.356, p = 0.272). Possible correlations between electrolyte levels and GCS scores were analyzed using the Spearman test, which showed no significant results for sodium (p = 0.054), potassium (p = 0.985), and ionized calcium (p = 0.738), whereas a correlation was found for chloride levels (ρ = -0.515; p = 0.002). No correlation was found between copeptin or ADH levels and sodium (p = 0.565 and 0.966), potassium (p = 0.210 and 0.520), calcium (p = 0.177 and 0.055), or chloride (p = 0.311 and 0.622).

Electrolyte levels were also not significantly associated with the need for surgery (p = 0.126 for sodium, p = 0.075 for potassium, p = 0.732 for ionized calcium, and p = 0.087 for chloride). Furthermore, Pearson analysis indicated no significant correlation between electrolyte levels and the presence of isolated head trauma (p = 0.322 for sodium, p = 0.507 for potassium, p = 0.998 for ionized calcium, and p = 0.205 for chloride).

Regarding imaging findings, the Mann-Whitney U test identified correlations between potassium levels and the presence of subdural hematoma (p = 0.032) and subarachnoid hemorrhage (p = 0.043) (

Figure 4). No other significant correlations were found between potassium levels and other imaging findings, nor were the associations between the levels of other electrolytes and the imaging findings analyzed in the study (

Table 1).

4. Discussion

Our study presents significant findings on the relationship between electrolyte disturbances and TBI within the first 24 hours of admission. Specifically, we discovered an inverse association between chloride levels and GCS scores (ρ = -0.515; p = 0.002). This is a notable discovery, as chloride levels have not previously been a primary focus in TBI research and may offer new insights into patient management. Historically, chloride levels have not been emphasized in TBI studies. However, our findings suggest that they may serve as a critical biomarker. Elevated chloride levels could indicate a more severe neurological status in TBI patients, thereby requiring close monitoring and possibly influencing therapeutic strategies. For instance, a study by Lee et al. found that hyperchloremia is linked to poor outcomes and increased mortality in major trauma patients, with hyperchloremia 48 hours post-admission correlating with 30-day mortality [

25]. In contrast, Jahanipour et al. reported no association between admission chloride levels and hospital mortality 24 hours later [

26].

Our research suggests that higher chloride levels correlate with lower GCS scores, potentially highlighting the importance of early chloride level monitoring. Several factors may contribute to elevated chloride levels in patients with severe TBI. Hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis can result from renal tubular acidosis, gastrointestinal losses, or iatrogenic causes [

27]. Intravenous fluid therapy, particularly the use of normal saline which has a high chloride concentration, is often used in large volumes for initial resuscitation in severely injured patients [

28]. Acute kidney injury, common in severely ill or injured patients, can impair chloride excretion, leading to accumulation [

29]. Additionally, certain medications, such as carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, can cause hyperchloremia by reducing bicarbonate reabsorption in the kidneys [

30].

Our findings advocate for the routine monitoring of chloride levels in TBI patients from the time of admission. Early detection of hyperchloremia could enable timely interventions to address underlying causes and prevent potential complications. Careful consideration of fluid types and volumes could prove essential in the resuscitation of TBI patients. Alternatives to normal saline or strategies to mitigate hyperchloremia should be explored to optimize patient outcomes. Additional studies are necessary to explore the precise impact of chloride levels on TBI outcomes and to establish evidence-based guidelines for the management of electrolyte disturbances in these patients.

Our study found significant correlations between potassium levels and the presence of subdural hematoma and subarachnoid hemorrhage, suggesting that potassium imbalances could be indicative of more severe brain injuries. However, no significant correlations were found between imaging findings and sodium, ionized calcium, or chloride levels. This could indicate that while potassium levels may serve as a marker for certain types of brain injury, other electrolytes do not appear to have the same predictive value. Patients with subdural hematoma and subarachnoid hemorrhage had lower potassium levels compared to those without these conditions. This association has not been documented in existing literature. However, lower potassium levels are frequently observed in severely traumatized patients. One explanation is that severely injured patients release higher quantities of adrenaline and cortisol, which increase renal potassium excretion and result in hypokalemia [

11]. These patients often require aggressive fluid resuscitation to maintain blood pressure and cerebral perfusion. Administering large volumes of potassium-free intravenous fluids can dilute serum potassium levels. Additionally, diuretics, such as furosemide or mannitol, commonly used to reduce intracranial pressure, can lead to increased renal potassium loss [

31,

32].

Brain injuries can also cause renal dysfunction or inappropriate antidiuretic hormone release, resulting in cerebral salt wasting where the kidneys excrete excessive amounts of sodium and potassium. Furthermore, associated gastrointestinal disturbances like vomiting or diarrhea in brain injury patients can cause significant potassium loss [

31,

33]. Finally, potassium deficiency is often observed in cases of metabolic alkalosis, a condition common in severely injured patients. This deficiency can exacerbate the situation by promoting renal hydrogen ion secretion and increasing renal ammonium production and excretion [

34].

Potassium and potassium-channels have been shown to play an important role in subarachnoid hemorrhage and subdural hematoma. An animal study conducted by Chen et al. on rats demonstrated that activating large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels in cerebral arteries could help alleviate spastic constriction [

35]. Other studies have shown that subarachnoid hemorrhage -induced membrane potential depolarization, involving disrupted potassium homeostasis, leads to increased activity of voltage-dependent calcium channels, elevated smooth muscle cytosolic calcium levels, and subsequent parenchymal arteriolar constriction [

36]. Experiments on small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels have shown that blockers of KCa3.1 can reduce infarct volume in a rat subdural hematoma model. These findings suggest that potassium channels could become therapeutic targets for treating traumatic and potentially ischemic brain injury [

37]. Additionally, there is significant evidence indicating that the mitochondrial ATP-dependent potassium channel plays a crucial role in the neuroprotective effects of cerebral preconditioning in a rat model of acute subdural hematoma [

38]. These insights underscore the importance of potassium and maintaining its normal levels. They also highlight the intricate molecular mechanisms at play and the necessity of further investigation to understand why subdural hematoma and subarachnoid hemorrhage are associated with lower potassium levels, unlike other types of brain injuries.

Our study revealed no significant association between sex and sodium, ionized calcium, or chloride levels in patients with TBI. However, a significant correlation was found between sex and potassium levels, with males exhibiting higher levels compared to females (p=0.016, mean for males = 3.985 mmol/L, mean for females = 3.511 mmol/L). This finding may be influenced by several physiological factors. Firstly, differences in sex hormones, such as testosterone and estrogen, play a crucial role in potassium regulation, with testosterone potentially contributing to higher potassium levels in males. Additionally, males generally have greater muscle mass, which serves as a primary reservoir for potassium, thereby explaining the elevated levels observed. Furthermore, lipid peroxidation, which is more prominent in males following severe TBI, may also contribute to these differences by affecting cell membrane integrity and potassium homeostasis [

39]. Our study's limited female representation reflects the historical view of TBI as predominantly affecting males, due to their higher participation in high-risk activities. This male bias is also prevalent in preclinical research, where male animals are often the subjects of basic and translational studies. However, with an aging population and increasing female involvement in high-risk activities, the incidence of TBI is becoming more sex-independent. Therefore, the importance of recognizing and addressing sex differences in TBI responses and outcomes is paramount. Future research should focus on increasing female representation in studies and exploring sex-specific mechanisms in TBI to enhance the design of clinical trials and treatment strategies [

40].

One of the strengths of this study is its focus on the first 24 hours post-injury, providing a critical time frame for understanding electrolyte changes. The study is limited by its relatively small sample size and single-center design, which may limit the generalizability of the result. Future research should aim to include larger, multi-center studies to validate our findings and provide a more comprehensive understanding of electrolyte imbalances in TBI patients. Longitudinal studies with longer follow-up periods would help determine the long-term effects of these imbalances and the efficacy of different treatment protocols.

5. Conclusions

Our study highlights the importance of monitoring electrolyte levels in TBI patients within the first 24 hours post-injury. Elevated chloride levels were inversely related to GCS scores, suggesting that chloride could serve as a biomarker for severe neurological impairment. Additionally, lower potassium levels were associated with subdural hematoma and subarachnoid hemorrhage, indicating the potential severity of these injuries. Routine early monitoring of chloride and potassium levels can improve patient management and outcomes. Further research with larger, multi-center studies is necessary to validate these findings and develop evidence-based guidelines for managing electrolyte imbalances in TBI patients. Understanding the role of electrolytes in TBI will help enhance patient care and improve outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and M.-D.T.; methodology, A.S.; investigation, A.S. and M.-D.T.; data curation, A.S.; formal analysis, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, M.-D.T.; supervision, M.-D.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Social Fund – the Human Capital Operational Programme, Grant No: POCU/993/6/13/154722.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committees of Emergency Hospital “Prof. Dr. Nicolae Oblu” Iași (4281/10.03.2020) and “Grigore T. Popa” University of Medicine and Pharmacy Iași (14/5.10.2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Saurabh, S.; Neeraj, K.; Singh, Y.; Kumar, Ghanshyam, S.Y.; Gupta, B.K.; EYa, R.; Ey, S. Evaluation of Serum Electrolytes in Traumatic Brain Injury Patients: Prospective Randomized Observational Study. J. Anesth. Crit. Care Open Access 2016, 5.

- Kolmodin, L.; Sekhon, M.S.; Henderson, W.R.; Turgeon, A.F.; Griesdale, D.E. Hypernatremia in Patients with Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review. Ann. Intensive Care 2013, 3, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tudor, R.; Thompson, C. Posterior Pituitary Dysfunction Following Traumatic Brain Injury: Review. Pituitary 2018, 22, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deveduthras, N.; Balakrishna, Y.; Muckart, D.; Harrichandparsad, R.; Hardcastle, T. The Prevalence of Sodium Abnormalities in Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury Patients in a Level 1 Trauma Unit in Durban. S. Afr. J. Surg. 2019, 57, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petra, C.M.D.-G.; Jean-Michel, M.; Maurice, D.; Eric, G.; Peter, C.R. Acute Symptomatic Hyponatremia and Cerebral Salt Wasting after Head Injury: An Important Clinical Entity. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2001, 36, 1094–1097. [Google Scholar]

- Ergul, A.; Alper, O.; Baş, V.; Humeyra, A.; Kurtoğlu, S.; Torun, Y.; Koç, A. A Rare Cause of Refractory Hyponatremia after Traumatic Brain Injury: Acute Post-Traumatic Hypopituitarism due to Pituitary Stalk Transection. J. Acute Med. 2016, 6, 102–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, R.; Ganesh, S.; Shalini, N.; Joseph, M. Hyponatremia in Traumatic Brain Injury: A Practical Management Protocol. World Neurosurg. 2017, 108, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannon, M.; Thompson, C. Neurosurgical Hyponatremia. J. Clin. Med. 2014, 3, 1084–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiaofeng, M.; Baozhong, S. Traumatic Brain Injury Patients with a Glasgow Coma Scale Score of ≤8, Cerebral Edema, and/or a Basal Skull Fracture Are More Susceptible to Developing Hyponatremia. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 2016, 28, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, R.; Aboudara, M.; Abbott, K.; Holcomb, J. Resuscitative Hyperkalemia in Non-Crush Trauma: A Prospective, Observational Study. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 2, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, M.; Link, J.; Hannemann, L.; Rudolph, K. Excessive Hypokalemia and Hyperkalemia Following Head Injury. Intensive Care Med. 1995, 21, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayach, T.; Nappo, R.; Jennifer, L.P.-M.; Ross, E. Postoperative Hyperkalemia. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2015, 26, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, G.; Goldner, F. Hypernatremia, Azotemia, and Acidosis after Cerebral Injury. Am. J. Med. 1957, 23, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beal, A.; Scheltema, K.; Beilman, G.; Deuser, W. Hypokalemia Following Trauma. Shock 2002, 18, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Xin, L.; Xiangqiong, L.; Jian, Y.; Yirui, S.; Zhuoying, D.; Xuehai, W.; Mao, Y.; Liangfu, Z.; Sirong, W.; et al. Prevalence of Severe Hypokalemia in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury. Injury 2015, 46, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesel, O.; Szold, O.; Itai, B.; Sorkin, P.; Nimrod, A.; Biderman, P. Dyskalemia Following Head Trauma: Case Report and Review of the Literature. J. Trauma 2009, 67, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, I.; Jauhar, N. Hypercalcemia Due to Immobilization. J. Endocr. Soc. 2021, 5 (Suppl_1), A196.

- Canivet, J.; Damas, P.; Lamy, M. Posttraumatic Parathyroid Crisis and Severe Hypercalcemia Treated with Intravenous Bisphosphonate (APD). Case Report. Acta Anaesthesiol. Belg. 1990, 41, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Emily, J.M.; Stubna, M.D.; Holena, D.; Reilly, P.; Seamon, M.; Brian, P.S.; Kaplan, L.; Jeremy, W.C. Abnormal Calcium Levels During Trauma Resuscitation Are Associated With Increased Mortality, Increased Blood Product Use, and Greater Hospital Resource Consumption: A Pilot Investigation. Anesth. Analg. 2017, 125, 895. [Google Scholar]

- Jessica, M.; Jonas, R.; Lauren, B.; Shane, U.; Cheng, A.; Aden, J.; Bynum, J.; Andrew, D.F.; Shackelford, S.; Jenkins, D.; et al. Clinical Assessment of Low Calcium In traUMa (CALCIUM). Med. J. 2023, 23, 74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Byerly, S.; Inaba, K.; Biswas, S.; Wang, E.; Wong, M.D.; Shulman, I.; Benjamin, E.; Lam, L.; Demetriades, D. Transfusion-Related Hypocalcemia After Trauma. World J. Surg. 2020, 44, 3743–3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neil, A.M.; Patwardhan, R.; Alexander, M.; Africk, C.; Lee, J.H.; Shalmon, E.; Hovda, D.; Becker, D. Characterization of Cerebral Hemodynamic Phases Following Severe Head Trauma: Hypoperfusion, Hyperemia, and Vasospasm. J. Neurosurg. 1997, 87, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Obrist, W.; Langfitt, T.; Jaggi, J.; Cruz, J.; Gennarelli, T. Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism in Comatose Patients with Acute Head Injury. Relationship to Intracranial Hypertension. J. Neurosurg. 1984, 61, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Triviño, C.Y.; Torres Castro, I.; Dueñas, Z. Hypochloremia in Patients with Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Possible Risk Factor for Increased Mortality. World Neurosurg. 2019, 124, e783–e788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Hong, T.H.; Lee, K.W.; Jung, M.J.; Lee, J.G.; Lee, S.H. Hyperchloremia is Associated with 30-Day Mortality in Major Trauma Patients: A Retrospective Observational Study. 2016, 24, 117.

- Jahanipour, A.; Asadabadi, L.; Torabi, M.; Mirzaee, M.; Jafari, E. The Correlation of Serum Chloride Level and Hospital Mortality in Multiple Trauma Patients. Adv. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 4, e4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yunos, N.M.; Bellomo, R.; Hegarty, C.; Story, D.; Ho, L.; Bailey, M. Association Between a Chloride-Liberal vs Chloride-Restrictive Intravenous Fluid Administration Strategy and Kidney Injury in Critically Ill Adults. Jama 2012, 308, 1566–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghunathan, K.; Shaw, A.D.; Bagshaw, S.M. Fluids are Drugs: Type, Dose, and Toxicity. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2013, 19, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellum, J.A. Disorders of Acid-Base Balance. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 35, 2630–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, S.K.; Halperin, M.L.; Goldstein, M.B. Fluid, Electrolyte and Acid-Base Physiology: A Problem-Based Approach, 4th ed.; Elsevier Health Sciences: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Viera, A.J.; Wouk, N. Potassium Disorders: Hypokalemia and Hyperkalemia. Am. Fam. Physician 2015, 92, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jensen, H.K.; Brabrand, M.; Vinholt, P.J.; Hallas, J.; Lassen, A.T. Hypokalemia in Acute Medical Patients: Risk Factors and Prognosis. Am. J. Med. 2015, 128, 60–67.e61.

- Kim, M.J.; Valerio, C.; Knobloch, G.K. Potassium Disorders: Hypokalemia and Hyperkalemia. Am. Fam. Physician 2023, 107, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Do, C.; Vasquez, P.C.; Soleimani, M. Metabolic Alkalosis Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment: Core Curriculum 2022. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2022, 80, 536–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.Y.; Cheng, K.I.; Tsai, Y.L.; Hong, Y.R.; Howng, S.L.; Kwan, A.L.; Chen, I.J.; Wu, B.N. Potassium-Channel Openers KMUP-1 and Pinacidil Prevent Subarachnoid Hemorrhage-Induced Vasospasm by Restoring the BKCa-Channel Activity. Shock 2012, 38, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellman, G.C.; Koide, M. Impact of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage on Parenchymal Arteriolar Function. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 2013, 115, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wulff, H.; Kolski-Andreaco, A.; Sankaranarayanan, A.; Sabatier, J.M.; Shakkottai, V. Modulators of Small- and Intermediate-Conductance Calcium-Activated Potassium Channels and Their Therapeutic Indications. Curr. Med. Chem. 2007, 14, 1437–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, I.; Wajima, D.; Tamura, K.; Nishimura, F.; Park, Y.S.; Nakase, H. The Neuroprotective Effect of Diazoxide is Mediated by Mitochondrial ATP-Dependent Potassium Channels in a Rat Model of Acute Subdural Hematoma. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 20, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Späni, C.; Braun, D.; Eldik, L. Sex-Related Responses After Traumatic Brain Injury: Considerations for Preclinical Modeling. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2018, 50, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayır, H.; Marion, D.; Puccio, A.; Wisniewski, S.; Janesko, K.; Clark, R.; Kochanek, P. Marked Gender Effect on Lipid Peroxidation after Severe Traumatic Brain Injury in Adult Patients. J. Neurotrauma 2004, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).