1. Introduction

Depression, anxiety, and stress are some of the most significant factors that can impede sports achievement. It is perhaps unsurprising, therefore, that athletes with less tension have been found to exhibit superior performance [

1]. Morgan showed that athletes who achieved the best outcomes were distinguished by lower levels of negative emotions (tension, confusion, depression, anger, and fatigue) and elevated positive emotions compared to those with lower athletic accomplishments [

2]. Negative emotion affects perception in sports competitions; most athletes consider anxiety to be detrimental to performance, a belief that can, itself, result in a decrease in performance [

3]. Kremer described somatic anxiety as physiological responses of the human body such as heart palpitations, breathing, and muscle tension. These physical signs are the consequence of psychological tension, which can generates pre-event unease in the athlete and result in unsatisfactory achievement [

4].

Given the significant psychological component of athletic competition, self-talk (ST), or statements individuals make to themselves for specific purposes such as increasing motivation or improving technical execution [

5], may boost athletic and sports performance [

6], including in sports demanding power-based skills [

7]. Theodorakis suggested that ST can help by improving attentional focus, increasing confidence, regulating effort, managing cognitive and emotional reactions, and stimulating automatic execution [

8]. Additionally, motivational ST intends to enhance performance by prompting self-confidence, effort, and energy output and contributing to a positive environment [

9]. Motivational ST is thought to have a larger effect on outcomes related to motivation such as effort, self-confidence, and belief in one’s abilities; initial evidence supporting this idea was offered by Hatzigeorgiadis’s experimental study, which found that motivational ST increased effort more than other types of ST [

10].

The use of ST to organize and manage an athlete’s thoughts has been promoted as an essential factor for successful sports performance, and ST is often included as a key component of psychological skills training [

11]. Preliminary evidence for the effects of ST has been provided through studies examining the effects of ST on various tasks and settings, as well as the post-event reports of athletes using ST. Van Raalte asked novice tennis players to report how they believed ST had affected their performance after a match. Participants reported that positive ST helped them target and improve their motivation, feel more confident, and focus their attention more effectively [

12]. Perkos conducted a 12-week ST training program for young basketball players and found that using ST enhanced the players’ dribbling and passing skills [

13]. Thelwell conducted a psychological skills training program for four amateur athletes participating in a laboratory-based triathlon task and found that the participants’ performance improved over time [

14]. Johnson tested the efficacy of an ST intervention program among female soccer players using a single-subject multiple baseline design, measuring performance in the low drive shot over a three-month period; they found the shooting performance of two of the three participants improved, and all three participants reported increased self-confidence compared to baseline [

15].

This study examined whether positive ST (i.e., statements such as “I can jump far,” “I can do it,” or “I’m a powerful jumper”) could improve standing long jump performance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

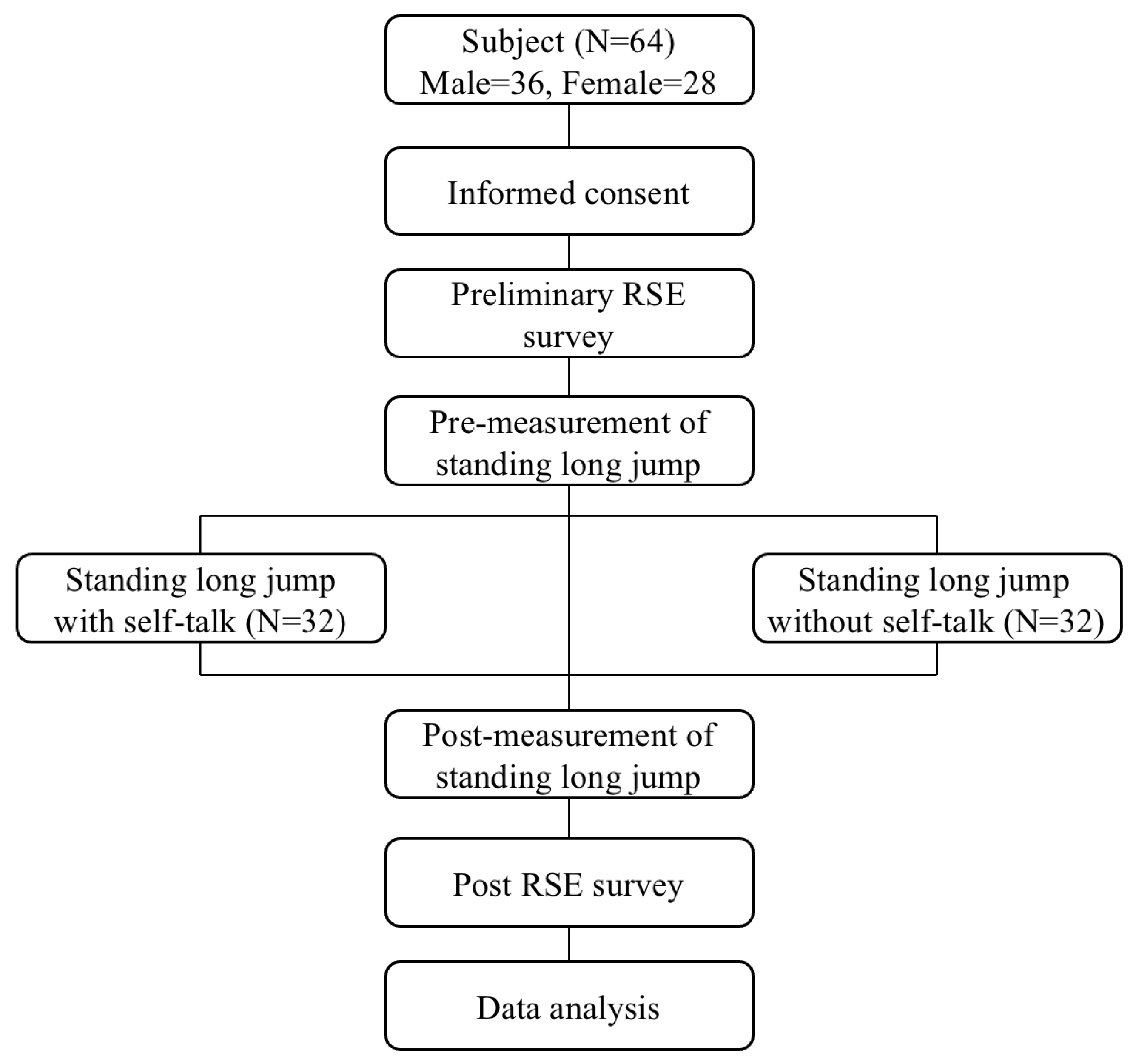

This study was conducted with 64 healthy adults at S University in Asan, Chungcheongnam-do. Participants had no injuries, history of injury, or abnormalities in general health; the following conditions were used as exclusion criteria: deformity of the foot, including flat feet or cavus foot; genu varum or genu valgum; spinal deformity such as scoliosis or kyphosis; wore or had recently worn orthosis that could affect walking or running. Participants were divided into an experimental group and a control group.

This study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of SUNMOON University. All subjects were recruited after IRB approval. Before the study commenced, a full explanation of the purpose and method of the study was provided to all participants, who provided written consent. Participants’ information is shown in

Table 1.

2.2. Measurement Questionnaire

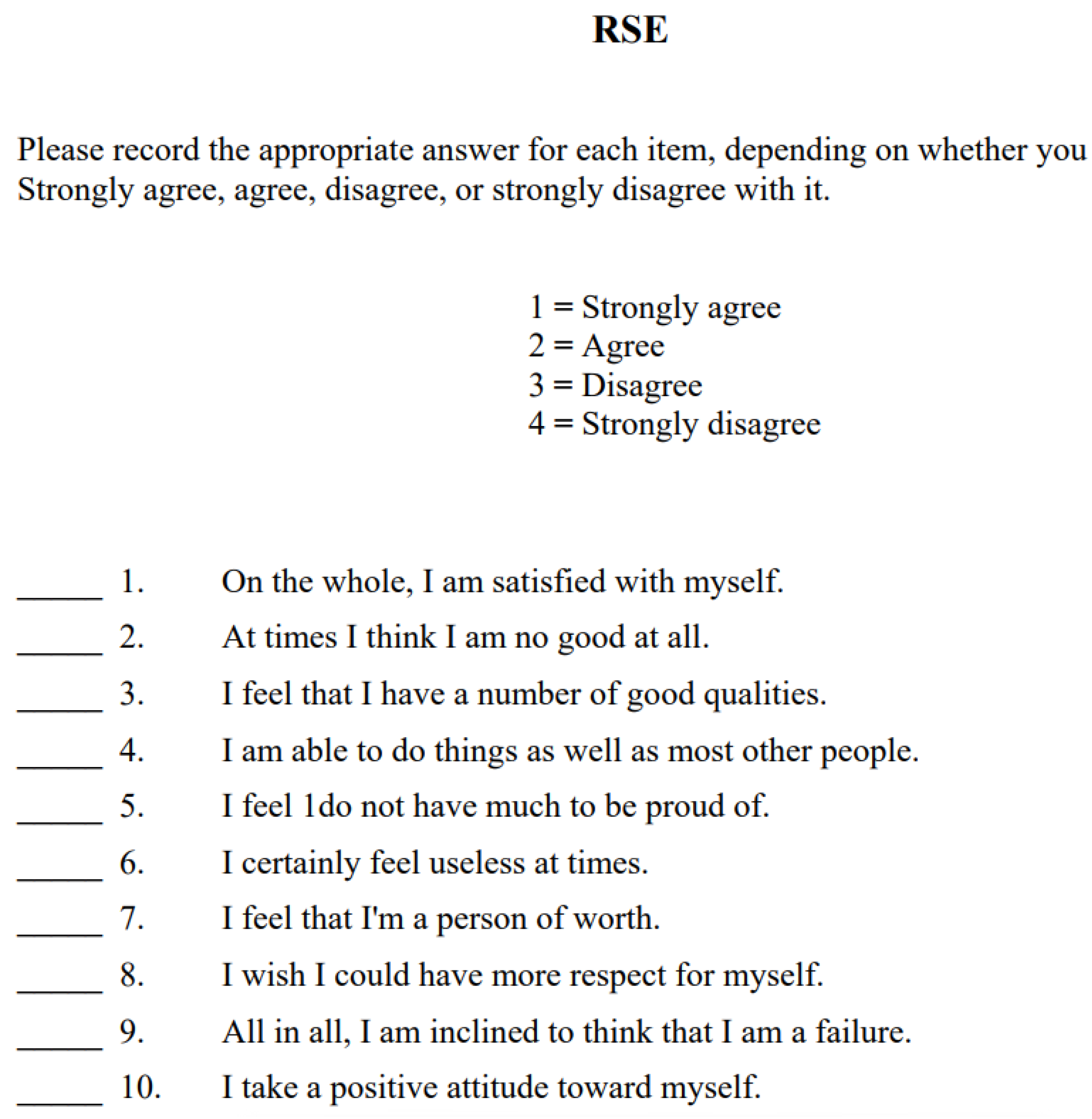

Before commencing the intervention, participants completed the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE) to provide a self-esteem baseline [

Table 2] [

16].

2.1.1. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE)

This RSE consists of 10 items and was originally designed to measure high school students’ self-esteem; it has since been used with various groups, including adults, and there are norms that can be used for many groups.

The RSE is a Guttman scale, and scoring uses combined ratings. Low self-esteem responses are “disagree” or “completely disagree” on items 1, 3, 4, 7, and 10, and “completely agree” or “agree” on items 2, 5, 6, 8, and 9. Two or three out of three positive answers to items 3, 7, and 9 are scored as one item. One or two out of the two appropriate answers to items 4 and 5 are considered as a single item. Items 1, 8, and 10 are graded as individual items. The combined appropriate answers (one or two out of two) for items 2 and 6 are a single item [

16]. The scale can also be scored by reverse-scoring the negatively worded items and then totaling individual four-point items.

2.3. Experimental Procedures

This study was measured with four criteria for exclusion of subjects. 1) a person with deformity of the foot including flat feet or cavus foot 2) a person with genu varum or genu valgum 3) a person with spinal deformity such as scoliosis or kyphosis 4) a person who has worn or recently worn orthosis that can affect walking or running.

For the SLJ procedure, a pre-measurement consisting of four SLJs was conducted after the RSE scale survey. Before the SLJ, the participants were given 5 to 10 minutes to warm up, and they had 2 minutes of rest following each attempt. During the four weeks of the intervention, the experimental group performed two or three SLJs each week after engaging in positive ST, while the control group performed two or three SLJs without engaging in positive ST. The post-measurement was conducted using the same method as the pre-measurement; all subjects completed the RSE and then were given four SLJ attempts [

Figure 1]

2.3.1. Self-Talk (ST)

During the four weeks of the intervention, the experimental group conducted an SLJ after engaging in positive ST, and the control group conducted an SLJ without engaging in positive ST. The subjects in the experimental group shouted “I can do it!” three times; the positive ST was designed to be shouted in the middle of the intervention. Subjects in the experimental group were cheered from the sidelines as they shouted and as they jumped to boost confidence, effort, and energy consumption and to create a positive atmosphere to enhance performance. Neither group shouted positive ST during the pre-measurement and post-measurement, all subjects were prevented from shouting positive ST.

2.3.2. Standing Long Jump(SLJ)

Participants were given five to ten minutes to warm up, then asked to perform four SLJs. In the pre-measurement, intervention, and post-intervention, two minutes of rest were given per SLJ attempt. Once the participant jumped, the attempt was measured using a tape measure, and the distance between the starting line and the heel closest to the starting line was recorded [

Figure 2]. Each of the subject’s jumps was measured in inches, and the units were converted to centimeters. The highest value and average value were recorded out of the 4 SLJ measurements.

2.4. Data Analysis

SPSS version 29.0 was used for analysis. Descriptive statistical values such as average and standard deviation were obtained for participant demographics such as age, gender, height, and weight. Participants’ prior homogeneity of categorical variables was analyzed using the chi-squared test, and the difference test before and after treatment for continuous variables was analyzed as a paired t-test. The test for the difference between groups among continuous variables was analyzed as a “student’s t-test.” The prior homogeneity was verified by cross-analysis. All statistical tests were conducted as one-sided tests, and the significance was evaluated as valid when the probability was p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Standing Long Jump (SLJ)

The change in SLJ distance depending on the presence or absence of ST is as follows. The experimental group’s pre-intervention mean distance was 204.29 ± 44.39, and the post-intervention mean was 219.34 ± 42.38 a statistically significant difference of 14.85 ± 10.57. The control group’s pre-test mean was 192.10 ± 40.24 and post-test mean was 192.03 ± 36.61, and the difference was not statistically significant -0.07 ± 13.01 [

Table 3].

3.2. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE)

We used the RSE scale to determine the correlation between ST and self-esteem. Between the two groups, only the experimental group showed a difference, with the experimental group’s pre-survey result being 32.31 ± 4.53 and the post-survey result being 36.97 ± 2.95. The change within the experimental group 3.31 ± 3.25 showed a significant difference. The pre-survey result of the control group was 32.25 ± 4.84 and the post-survey result was 32.03 ± 5.72, and the difference of -0.13 was not significant [

Table 4].

4. Discussion

In the context of sports, while numerous studies have suggested that the regulation of positive emotions can impact performance [

17], research on these methods and among diverse participants has been limited. Typically, such studies have been confined to professional athletes [

18,

19] and have primarily focused on internal ST methods [

20,

21]. Therefore, there is a need for a deeper understanding of the precise impact of positive emotions on the well-being and performance of athletes [

22]. To investigate this, we explored the relationship between participants’ psychology and athletic performance through ST. The ST intervention involved participants verbalizing phrases such as “I can do this” and “I will jump far,” allowing both internal and external expressions, and the effect was evaluated through repeated SLJ tests.

SLJ requires explosive strength and coordination of the arms and legs; it requires little skill, but relies heavily on the muscular functions of strength and power. Explosive power can be appropriately measured through jumping, and research has demonstrated a correlation between lower-body explosive strength and upper-body strength [

23].

SLJ is an effective measure of both lower and upper body strength [

24]. Arsyad (2018) suggested that physical explosiveness has a direct impact on reaction time, with confidence having a direct positive influence on reaction time. This implies that confidence positively affects bodily explosiveness [

25]. Hence, SLJ which requires explosive strength and simultaneous coordination of the upper and lower body, was chosen for this study to examine the relationship between psychological effects and athletic performance.

In this study, participants performed SLJ over a span of four weeks, with measurements taken 2-3 times a week. First, the results of pre- and post- measurements in the experimental group showed a significant difference, while no significant difference was observed in the control group. In addition, a pre- and post- survey using the RSE scale was conducted to measure changes in self-esteem; the experimental group showed a significant change, while the control group did not. These results indicate that ST also has an impact on self-esteem. These results align with previous research; Adeyeye (2013) conducted an experiment with injured athletes who engaged in positive ST in conjunction with exercise therapy over six weeks, while a control group only underwent exercise therapy. Significant differences were observed only in the experimental group [

26]. Additionally, Harbalis (2008) divided wheelchair basketball players into an experimental group that engaged in ST during testing and a control group that did not. The research results showed that the use of ST strategies facilitates the learning and performance enhancement of healthy athletes [

27]. It can be concluded that ST has a positive psychological impact, enhancing one’s physical abilities and performance.

4.1. Negative Psychology Affects Sports Performance

The main thrust of sports emotion research has focused on anxiety because of its effect on cognitive functioning and physical performance [

22]. Negative affect such as depression, frustration, anxiety, and stress can have a negative effect on performance But every athlete has a certain stress level that is needed to optimize his or her performance and that bar depends on factors such as past experience, coping responses, and genetics. Bali (2015) indicated that appropriate pressure and stress can lead to peak performance [

28]. However, this effect may be limited to elite athletes who can control and manage stress. Similar studies of negative among non-elite athletes have shown that it can have adverse effects on the body, including suppression of immune function, increased risk of autoimmune diseases and allergies, increased incidence, severity, or duration of illness, asthma, and potential reactivation of viruses [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. In addition, Parnabas (2015) found that high levels of cognitive anxiety worry, negative thoughts, and fear of failure interfere with high performance in sports [

34]. Englert (2012) also found that when anxiety was high, performance was more likely to suffer due to ego depletion [

35]. Taken together, this research may suggests that various negative psychological factors have a negative impact on physical and athletic performance.

4.2. Positive Psychology Influences

Stress is often accompanied by physical symptoms [

36], and performance levels increase when stress management is effective [

28]. This can be observed in a variety of sports activities. For instance, Lee (2022) suggested that mental skills training can not only improve sports performance but also promote positive psychological development [

18]. Also, Hamilton (2007) reported that participants engaging in positive ST performed significantly better than those using negative ST on a variety of sporting tasks [

37]. That is why, in sports training, coaches and managers conduct training to strengthen athletes’ psychological skills and reduce stress through relaxation techniques such as positive ST and deep breathing [

36]. Hatzigeorgiadis (2008) examined the effects of motivational ST on young athletes’ self-efficacy and motivational ST can be an effective strategy for building self-efficacy [

38], providing additional support for the link between ST and self-efficacy [

39]. ST interventions have been shown to be effective in enhancing sport task performance, including in the complex environment of competition [

40].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our research demonstrated that positive ST had a positive effects on SLJ performance. Participants who performed positive ST and then engaged in SLJ exhibited improvement than those who did not. In addition, the group who engaged in positive ST showed an increase in self esteem scores compared to the group that did not. Through this, this study provides additional evidence supporting the effectiveness of positive ST on athletic performance. The results of this study demonstrate the importance of a positive attitude in sports performance, rehabilitation, and the effectiveness of pre-performance positive. Such training, incorporating positive psychological approaches, can be widely applied to various sports training and therapeutic methods, including neurological and musculoskeletal rehabilitation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.-Y.J., S.-H.K., and Y.-G.N.; methodology, E.-Y.J. and S.-H.K.; software, S.-H.K. and S.-Y.O.; formal analysis, E.-Y.J. and S.-Y.O.; investigation, E.-Y.J. and S.-H.K.; writing—original draft preparation, E.-Y.J.; writing—review and editing, E.-Y.J., S.-H.K., and Y.-G.N.; supervision, Y.-G.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Sun Moon University Research Grant of 2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sun Moon University (ID: SM-202309-027-3; approval date: 15 November 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study, and written informed consent was obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Bagheri, R.; Pourahmadi, M.R.; Hedayati, R.; Safavi-Farokhi, Z.; Aminian-Far, A.; Tavakoli, S.; Bagheri, J. Relationships between Hoffman reflex parameters, trait stress, and athletic performance. Percept.Mot.Skills 2018, 125, 749–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, W.P. Test of champions: The iceberg profile. 1980, 92, 108.

- Raglin, J.S.; Hanin, Y.L. Competitive anxiety. 2000.

- Lavallee, D.; Kremer, J.; Moran, A. Sport psychology: Contemporary themes; Bloomsbury Publishing: 2012.

- Tod, D.A.; Thatcher, R.; McGuigan, M.; Thatcher, J. Effects of instructional and motivational self-talk on the vertical jump. 2009, 23, 196-202. [CrossRef]

- Zinsser, N.; Bunker, L.; Williams, J.M. Cognitive techniques for building confidence and enhancing performance. 2006, 5, 349-381.

- Hardy, J. Speaking clearly: A critical review of the self-talk literature. Psychol.Sport Exerc. 2006, 7, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorakis, Y.; Hatzigeorgiadis, A.; Chroni, S. Self-talk: It works, but how? Development and preliminary validation of the functions of self-talk questionnaire. 2008, 12, 10-30. [CrossRef]

- Theodorakis, Y.; Weinberg, R.; Natsis, P.; Douma, I.; Kazakas, P. The effects of motivational versus instructional self-talk on improving motor performance. 2000, 14, 253-271. [CrossRef]

- Hatzigeorgiadis, A. Instructional and motivational self-talk: An investigation on perceived self-talk functions. 2006, 3, 164-175.

- Hardy, L.; Jones, G.; Gould, D. Understanding psychological preparation for sport: Theory and practice of elite performers; John Wiley & Sons: 2018.

- Van Raalte, J.L.; Brewer, B.W.; Rivera, P.M.; Petitpas, A.J. The relationship between observable self-talk and competitive junior tennis players’ match performances. 1994, 16, 400-415. [CrossRef]

- Perkos, S.; Theodorakis, Y.; Chroni, S. Enhancing performance and skill acquisition in novice basketball players with instructional self-talk. 2002, 16, 368-383. [CrossRef]

- Thelwell, R.C.; Greenlees, I.A. Developing competitive endurance performance using mental skills training. 2003, 17, 318-337. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.J.; Hrycaiko, D.W.; Johnson, G.V.; Halas, J.M. Self-talk and female youth soccer performance. 2004, 18, 44-59. [CrossRef]

- Ciarrochi, J.; Bilich, L. Acceptance and commitment therapy. Measures package. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, I.; Ahmad, M.; Fatima, R. The Impact of Sports Optimism on Sports Performance. 2023, 4, 16-26. [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Wang, M.; Huang, B.; Hsu, C.; Chien, C. Effects of psychological capital and sport anxiety on sport performance in collegiate judo athletes. Am.J.Health Behav. 2022, 46, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tjiptorini, S.; Oktaviani, A.E. In The Influence of Self Talk on Badminton Athletes Anxiety Before Competitions; Proceedings of International Conference on Psychological Studies (ICPSYCHE); 2022; Vol. 3, pp 245-251.

- Amado, D.; Maestre, M.; Montero-Carretero, C.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A.; Cervelló, E. Associations between self-determined motivation, team potency, and self-talk in team sports. 2019, 70, 245-259.

- Jabbari, E.; Rouzbahani, M.; Dana, A. The effects of instructional and motivational self-talk on overt and covert levels of motor performance. 2013, 1, 1-10.

- McCarthy, P.J. Positive emotion in sport performance: Current status and future directions. 2011, 4, 50-69. [CrossRef]

- Das, D. Relationship between jump and reach test and standing broad jump as a measure of explosive power. 2018.

- Castro-Piñero, J.; Ortega, F.B.; Artero, E.G.; Girela-Rejón, M.J.; Mora, J.; Sjöström, M.; Ruiz, J.R. Assessing muscular strength in youth: Usefulness of standing long jump as a general index of muscular fitness. 2010, 24, 1810-1817. [CrossRef]

- Arsyad, P.; Hanif, A.S.; Tangkudung, J. The effect of explosive power leg muscle, foot-eye coordination, reaction speed and confidence in the ability of the crescent kick. 2018, 4, 141-150. [CrossRef]

- Adeyeye, F.M.; Vipene, J.B.; Afuye, A.A. Effect of progressive relaxation and positive self-talk techniques on coping with pain from sports injuries among students of University of Lagos, Nigeria. 2013.

- Harbalis, T.; Hatzigeorgiadis, A.; Theodorakis, Y. Self-talk in wheelchair basketball: The effects of an intervention program on dribbling and passing performance. 2008, 23, 62-69.

- Bali, A. Psychological factors affecting sports performance. 2015, 1, 92-95.

- Marshall, G.D. The adverse effects of psychological stress on immunoregulatory balance: applications to human inflammatory diseases. 2011, 31, 133-140. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.K.; Marshall Jr, G.D. Stress effects on immunity and its application to clinical immunology. 2001, 31, 25-31. [CrossRef]

- Roy-Byrne, P.P.; Davidson, K.W.; Kessler, R.C.; Asmundson, G.J.; Goodwin, R.D.; Kubzansky, L.; Lydiard, R.B.; Massie, M.J.; Katon, W.; Laden, S.K. Anxiety disorders and comorbid medical illness. Gen.Hosp.Psychiatry 2008, 30, 208–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, K.M.; Von Korff, M.; Ormel, J.; Zhang, M.; Bruffaerts, R.; Alonso, J.; Kessler, R.C.; Tachimori, H.; Karam, E.; Levinson, D. Mental disorders among adults with asthma: Results from the World Mental Health Survey. Gen.Hosp.Psychiatry 2007, 29, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godbout, J.P.; Glaser, R. Stress-induced immune dysregulation:Iimplications for wound healing, infectious disease and cancer. 2006, 1, 421-427.

- Parnabas, V.; Parnabas, J.; Parnabas, A.M. The influence of cognitive anxiety on sport performance among taekwondo athletes. 2015, 2, 56-63.

- Englert, C.; Bertrams, A. Anxiety, ego depletion, and sports performance. 2012, 34, 580-599. [CrossRef]

- Abou Elmagd, M. General psychological factors affecting physical performance and sports. 2016, 255, 255-264.

- Hamilton, R.A.; Scott, D.; MacDougall, M.P. Assessing the effectiveness of self-talk interventions on endurance performance. 2007, 19, 226-239. [CrossRef]

- Hatzigeorgiadis, A.; Zourbanos, N.; Goltsios, C.; Theodorakis, Y. Investigating the functions of self-talk: The effects of motivational self-talk on self-efficacy and performance in young tennis players. 2008, 22, 458-471. [CrossRef]

- Hardy, J.; Hall, C.R.; Gibbs, C.; Greenslade, C. Self-talk and gross motor skill performance: An experimental approach. 2005, 7, 1-13.

- Hatzigeorgiadis, A.; Galanis, E.; Zourbanos, N.; Theodorakis, Y. Self-talk and competitive sport performance. 2014, 26, 82-95. [CrossRef]

- Hoitz, F.; Mohr, M.; Asmussen, M.; Lam, W.; Nigg, S.; Nigg, B. The effects of systematically altered footwear features on biomechanics, injury, performance, and preference in runners of different skill level: A systematic review. 2020, 12, 193-215. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).