1. Introduction and Literature Review

1.1. Introduction and General Notes on the State of Play of Research

Tourism is currently fundamental for social progress due to its cultural, environmental and socio-economic impact. Conventional tourism models question the sustainability of territories because of their high consumption of energy and natural resources and because they often generate social inequalities [

1].

Tourism employs 200 million people and accounts for 4.4% of global gross domestic product. The sector can support sustainable management at the community level as a market-focused alternative and the provision of services to a growing number of travellers seeking to discover, understand and enjoy a natural environment through the enjoyment of sustainable agrotourism in the context of protected areas [

2], which becomes more relevant in the post-Covid-19 pandemic period.

With backward and poorly remunerated agricultural production systems, Latin America is experiencing a socio-economic depression with a high level of social marginalisation. The search for alternative socio-economic solutions that allow for increased income from non-agricultural activities such as agro-tourism is essential [

3].

There is a need for tourism models that are respectful of the environment and humanity, that avoid excessive consumption of natural resources and that put an end to the excessive production of pollutants in the soil, air and watersheds [

4].

The researcher Baños Castiñeira analyses that it is necessary to appeal to the so-called complementary tourism offer and within this, agrotourism in protected natural spaces (ENP) is of interest as an appropriate way of achieving the diversification of destinations linked to new leisure formulas [

5].

Tourism is an activity that can incorporate territorial policies aimed at achieving the socio-economic balance of regional spaces, based on the complementarity of tourism offers developed from local endogenous potential [

5].

In tourism, there is a progressive diversification of tourism products and destinations, with an increase in demand for nature tourism, ecotourism activities, visits to national and natural parks, rural tourism, agro-tourism and community tourism, among others. For the travel experience to be meaningful, tourists are looking for direct contact with the indigenous, cultural authenticity, connection with local communities and direct contact with flora, fauna, exceptional ecosystems, nature in general and its preservation [

2].

Shaping tourism activity in terms of innovation and continuous improvement is necessary to achieve adaptation to climate change, as well as the transformations occurring in the socio-economic scenario, especially agrotourism activities carried out in the rural environment of protected areas. The situation implies the continuous change of old practices for attractive and successful tourism policies, with the capacity to offer new products and services adapted to the rural situation to benefit less favoured areas [

6,

7].

Given the nature and impact of agrotourism for the socio-economic development of rural areas located in protected areas, it constitutes a critical component to be taken into account in the management of social life in rural Ecuador [

8].

In rural areas that are considered protected, the relationships that arise from tourism activities are always complicated and sometimes conflictive, however, it is feasible to regulate them in an environment in which there is an adequate balance between agro-tourism management and the interests of protection for the benefit of society. The sustainable use of natural resources and the valorisation of natural resources with environmentally friendly criteria must be part of the modelling of agrotourism in protected areas [

3,

8].

Based on criteria such as environmental preservation, social equity, quality of life and respect for cultural identity, agro-tourism is becoming increasingly important in the sustainable development paradigm [

9,

10,

11].

Agro-tourism in the context of protected areas must consider a group of dimensions, which are key for tourism activity to be sustainable. The promotion of innovation and social responsibility in tourism processes, the incorporation of sustainability in all its dimensions, the prioritisation of the demand for inclusive and accessible tourism, the creation of trust and security, the protection of employment, the creation of protocols and procedures that respond to the use of space and resources in a sustainable manner [

12,

13].

Based on the above analysis, the research problem is: what is the significance of agro-tourism for the sustainable development of rural communities located in the context of protected areas?

Based on the problem posed, the objective of the research is: to assess the relevance of the agrotourism model in protected areas as a sustainable development alternative for less favoured rural areas, which guarantees alternative economic income to improve the living conditions of rural society.

It is based on the premise that agrotourism activity is compatible with sustainable development in the context of protected areas. It does not require large investments in tourism infrastructure and is based on the satisfaction of resources through the perspective of endogenism, the protection of natural resources and the preservation of nature, to induce visitors in the development of activities and the consumption of rural resources that are attractive, rewarding and unique life experiences for tourists.

1.2. Definitions of Agro-Tourism and Its Specificities

Sustainable agrotourism is seen as a development strategy that uses agricultural heritage and biodiversity for the promotion of responsible tourism [

14]. It focuses on rural and agricultural activities. Tourists have the opportunity to experience life on a farm, participate in agricultural activities, learn about farming and animal husbandry practices. It can include activities such as fruit and vegetable picking, creation of handicrafts, horseback riding and tasting of local products [

15].

Agrotourism is a relatively new concept that in recent years has become popular with tourists. In Spain, 1,888,639 Spanish residents and 181,998 foreign visitors decided to stay in rural tourism establishments, despite the crisis generated by COVID 19 [

16].

Agrotourism has the potential to promote sustainable development and generate additional income for rural communities, as well as providing an educational and recreational experience for tourists [

17]. It can be affirmed that sustainable agrotourism constitutes an integral strategy aimed at achieving a balance between the economic, social, environmental and cultural dimensions, allowing the promotion of sustainable development in rural areas [

18].

The materialisation of environmental protection measures in protected areas can be achieved through the financial resources generated by agrotourism. The financing of education, interpretation and information programmes for visitors and residents, related to the planning, administration and supervision of agrotourism in protected areas is crucial [

19].

Agro-tourism can be an economic alternative for the rural family in the context of protected areas as a solution for sustainable development, improving social conditions and favouring the decrease of migration to the cities by generating new jobs within the farming family, especially women become direct generators of economic benefits [

3,

20,

21,

22].

Agro-tourism in protected areas is considered as part of the wellbeing policies developed for the Millennium Assessment [

23], which relates to the need for freedom of choice and action, good social relations and the satisfaction of life needs.

Agrotourism in the rural context of protected areas promotes the exercise of a healthy life in society to contribute to individual subjective wellbeing, active participation in social life [

24], the strengthening of subjective wellbeing [

25], the increase of quality of life based on values [

26] and the strengthening of the notion of wellbeing based on needs [

27].

The World Tourism Organisation (UN Tourism) created the Sustainable Tourism Network (Redturs), which supports the strengthening of agro-tourism modalities in the rural context of protected areas [

28].

The administrative and institutional management of protected areas must take into account that human interaction within the communities is fundamental for their adequate management, which is why it should not be limited to environmental protection alone [

19,

29].

The success of agro-tourism requires the active participation of the community in environmental protection, providing concrete benefits such as community participation and the enjoyment of the benefits of sustainable tourism in the life of the community [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

An important issue for the development of protection strategies based on sustainable development is the understanding of society's attitudes and perceptions of agro-tourism activity in protected areas. Policies aimed at achieving community support through increased benefit-sharing opportunities should be promoted [

35,

36,

37,

38].

In the context of protected areas researchers Shibia, Tilahun, Caviedes-Rubio, Diego, Olaya-Amaya, Macura, Zorondo, Grau, Kathryn, Laval, Claude, Garcia, Reyes, Fox, Molina and Swearingen [

31,

38,

39,

40,

41] conducted studies showing community approval for tourism development, highlighting the importance of research that seeks to re-signify the relevance of sustainable agrotourism in protected areas. The analysis of such elements is beneficial for the promotion of agro-tourism in protected areas, with the support and active participation of the resident community.

1.3. Definition and Background of Protected Areas

A protected area is a land or sea territory that is dedicated in particular to the preservation and protection of biological diversity and related natural and cultural resources. It is generally managed through legal means and other effective territorial, national and international regulations. Some protected areas share the context of a rural area [

42].

Protected areas are a cultural artifice with a long history. In India they emerged two millennia ago to identify particular areas dedicated to the preservation of natural resources [

43]. A millennium ago, they were used in Europe to protect the hunting grounds of the rich and powerful. In other regions they are used to protect places with special characteristics such as traditional Tapu areas in Pacific communities and in Africa for the protection of sacred forests [

44].

During the European Renaissance kings and other leaders decreed the first protected areas. With the aim of establishing the basis for tourism and community participation, the public gradually began to visit places declared as protected areas [

2].

In 1832, the United States of America proposed the creation of a state park for environmental conservation in the east of the country, but it was not until 1872 that Yellowstone Park was created as a public space or recreational area for the benefit and enjoyment of the population [

2,

45].

In Australia, in 1866, a 2,000-ha environmental reserve was decreed for protection and tourism [

46]. In 1885 Canada decreed the protection of hot springs in the Rockies and later became Banff National Park, where the railway companies appreciated the opportunity for the creation of a park to stimulate the growth of traveller numbers and tourism. At the end of the 19th century in South Africa, several forest reserves were decreed. In 1894 in New Zealand, the Tongariro National Park was created [

47].

A common denominator of all protected areas is that they were created through government initiative, with large areas of natural environment set aside for public enjoyment, and the promotion of tourism was a key element in the creation of protected areas [

47].

Linking people, their customs and culture to the land and natural resources as part of the concept of protected areas is a key element in achieving the proposed environmental protection objectives [

48].

In the 20th century, the declaration of protected areas spread globally. Almost all countries published laws and determined the protection of certain areas. At the beginning of the 21st century about 44,000 areas were designated as protected areas with a space representing approximately 10% of the earth's surface [

48].

The evolution of the concept and significance of protected areas is influenced by the development of ecology, which allows for a better understanding of resource planning and management with a systematic and systemic approach, which enables an appropriate classification of protected areas, which redefines biodiversity protection as a starting point and which recognises the importance of agro-tourism as a key element for the promotion of social culture [

49].

In Ecuador, protected areas are enshrined in article 24, section 7 of the Organic Environmental Code, which declares the integration of protected areas into the subsystems of the National System of Protected Areas and defines the categories, guidelines, tools and mechanisms for their management and administration [

50].

The relevance of protected areas is favoured by the introduction of agro-tourism, which by its endogenous nature could be understood as part of the park tourism system. The economic importance of protected areas is increasingly valued in terms of their environmental performance, which includes controlling the effects of climate change and providing clean water [

51,

52].

Since the adoption of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 1992, protected areas have received increased attention as a means of biodiversity conservation and other purposes [

53].

Some protected areas are part of international networks, which may be global or regional in scope. There are calls for recognition of the role of indigenous peoples in relation to protected areas [

54], as well as the promotion of international cooperation in transboundary protected areas [

55].

Figure 1 shows the categorical classification of protected areas.

Recreation and tourism management are among the purposes of the protected area categories, except for category Ia, which corresponds to the strict nature reserve managed for scientific purposes. Biodiversity protection is not the sole purpose, although a special policy to protect and maintain biodiversity is required [

56].

Marine protected areas have gained increased recognition in recent years. There are more than 2,000 marine protected areas, representing approximately 2.5 million km2 . These include terrestrial sites, reefs, seagrass beds, shipwrecks, archaeological sites, brackish coastal lagoons, mud flats, salt marshes, mangroves and rock shelves [

57].

The complexity of protected area management indicates that much remains to be done to improve the effectiveness of protected area management [

58]. Of key importance is the consideration that when agro-tourism is undertaken, precise management frameworks and strategies are put in place to ensure that the natural and cultural values of protected areas are maintained.

Regardless of the agro-tourism activities that take place in the context of protected areas, access to other areas for tourism activities must be carefully observed, which is a relevant challenge involving complex judgements about the trade-offs between agro-tourism development, resource value protection and local community interests [

58].

Agro-tourism in protected areas is revived from the tourists' conception. The need for a close encounter with others in order to exchange with exotic populations and landscapes, and the search for a return to nature as a source of physical and mental health, are ideological conceptions that favour the choice of agrotourism based on the environment of protected areas [

59].

Sustainable agrotourism in the context of protected areas seeks to offer spaces and an interesting leisure practice, which emerges from unique living experiences based on the exchange of diverse cultures and the enjoyment of natural landscapes, which satisfy the preferences of tourists and a return to nature Hiernaux-Nicolas, D, 2002.

In the management of agro-tourism in the context of protected areas, in addition to the activities themselves, which allow direct contact with agricultural functions and resources, cultural exchange is also important, as it provides an incursion into the knowledge of manifestations rooted in ancestral culture and which form an inseparable part of the identity of the people. Visits to museums play an important role in education and the preservation of local, regional and national identity [

60,

61]. Visits to archaeological sites and areas are a special attraction for visitors who prefer to enjoy the historical and cultural values of the community [

62].

1.3.1. Protected Areas in Ecuador

In Ecuador, tourism in protected areas emerged in the 1980s as a result of the influx and boom in rural tourism and indigenous tourism, which emerged as a response of indigenous peoples and Montubio nationalities to the exploitation of natural resources by large oil companies and agricultural enterprises, which sowed poverty and environmental pollution at the cost of depredating the country's natural resources [

63].

The first manifestation of tourism in protected areas in Ecuador took place in 1979 in the community of Agua Blanca, located in the Machalilla National Park in the province of Manabí [

62,

64], but the weak promotion works for this type of tourism prevented the experiences from being known, as well as not considering agro-tourism, which could represent an interesting offer for the demand profile related to nature tourism and indigenous tourism.

The current focus is on promoting sustainable agro-tourism in the context of Ecuador's protected areas. The adoption of environmental protection protocols capable of filling the gaps and inadequacies of other tourism models and creating a management environment based on innovation and endogenism to face the challenges imposed by the changing situation of today's world through compliance with the institutional regulatory framework, self-regulation linked to protection, high environmental awareness that guarantee the success of agro-tourism activity in the context of protected areas [

65].

The experiences of the research carried out in the Bigodi community on the African continent may be useful for opening up Ecuadorian agrotourism. The results showed that residents considered agrotourism to be capable of creating community social development, improving agricultural markets and generating income and good fortune [

66].

Another experience that can be useful for the development of agrotourism in Ecuador is the research carried out in Turkey in 2011, which served to determine the limitations related to tourism due to the lack of identification and classification of nature tourism resources, which allowed the identification and classification of a group of natural resources and determined their tourism value. The results showed that the level of environmental degradation in the studied area was very low, which required an approach that unveiled a high potential for tourism development [

67]. Other studies with similar objectives were developed in the Latin American area in Belize [

68], Dominica [

69], Peru [

70] and Brazil [

71].

1.4. Sustainability Dimensions and Indicators

Loor-Bravo, Plaza-Macías and Medina-Valdés reflect on the challenges facing tourism and consider that the sustainability of the sector cannot be sustained by unrealistic project discourses that deviate from the dimensions and fulfilment of sustainability indicators [

72].

Sustainable agrotourism aims to balance the economic, social, environmental and cultural dimensions of education to ensure long-term benefits for the local community and visitors.

Figure 2 shows the dimensions of sustainable agrotourism [

73].

Agrotourism sustainability indicators are metrics used for the evaluation and measurement of the economic, social and environmental impact of tourism activities in rural and agricultural areas. They are essential to ensure that agritourism practices are sustainable in the long term, to benefit local communities, the environment and meet visitor expectations [

74].

The model of sustainable agro-tourism in the context of protected areas is based on the fulfilment of a group of indicators that determine the sustainability of agro-tourism management in the conditions of protected areas, which will allow for a process of evaluation and continuous improvement, making it possible to evaluate and improve agro-tourism activity based on the real situation in which it is carried out [

75].

The importance of sustainability indicators for agrotourism is that they are tools that serve to ensure that agrotourism activity is not only a source of income and development for rural communities, but also serves as an environmentally friendly and socially responsible activity [

76].

Agrotourism sustainability indicators enable the identification of areas for continuous improvement and the implementation of more sustainable and efficient practices. They foster transparency and accountability in agrotourism management, improve trust and support from the community and visitors. Provide essential information for informed decision-making by agrotourism stakeholders, governments and non-governmental organisations. Enable the identification of areas for improvement and the implementation of sustainable and efficient practices. They help to promote and disseminate good practices and serve as a reference for other agrotourism projects [

76].

There are three basic types of indicators for sustainable agrotourism, as shown in

Figure 3.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The development of tourism in Ecuador as an economic activity began in 1930 with the enactment of the Tourism Promotion Law. At the end of the first half of the 20th century, operations began with the creation of the first travel agency called Ecuadorian Tours, which began to develop variants of mass tourism. In later years, other variants of alternative tourism emerged as an important socio-economic factor in economically and socially vulnerable areas, especially those in rural environments [

77].

Ecuador's National System of Protected Areas comprises 26,208,785.38 hectares, representing 19.42% of the country's territory. Due to the country's geographical location, there is a high level of biodiversity. It has 14 national parks: Machalilla, Cayambe, Coca, Cotacachi-Cayapas, Cotopaxi, Llanganates, Sangay, El Cajas, Podocarpus, Yacuri, Antisana, Sumaco-Napo-Galeras, Río Negro Sopladora and Yasuní T/T [

78].

The research was carried out in the Machalilla National Park (PNM), which is a natural protected area (NPA) located in the Ecuadorian coastal territory, specifically in the south of the province of Manabí. It occupies part of the municipal territories of Puerto López and Jipijapa, in the parishes of Puerto Cayo, Machalilla, Julcuy and Puerto López [

78]. In 1979 it was founded in the Agua Blanca community, which is a community tourism establishment located within the boundaries of the Machalilla National Park [

62].

The MNP was created on 26 July 1979 and is part of Ecuador's national system of protected areas. It is named after one of the primitive cultures that inhabited the Pacific coast between 1800 and 1000 BC. It encompasses a wide terrestrial and maritime area where there is an important biodiversity of flora and fauna, due to the presence of the last tropical dry forest in the country, with more than 150 endemic species, and the marine area is the nesting area for the four species of turtles registered in Ecuador and the mating area for humpback whales [

78].

Figure 4 shows the map of the province of Manabí where Machalilla National Park is located.

Tourist attractions in the MNP include Los Frailes beach, Isla de la Plata and the community of Agua Blanca. There are important archaeological sites that document human occupation dating back 5,000 years and constitute a special attraction for the visit of the archaeological museum that exists in Agua Blanca.

The families living within the boundaries of the MNP are engaged in agricultural activities, small livestock breeding, artisanal fishing, and the women spend their time making handicrafts. The social situation is not satisfactory; it is common to find small localities with a high degree of vulnerability. The communities Salaite and Pueblo Nuevo are located on the coast and their main economic activity is artisanal fishing; the rest are surrounded by mountainous terrain with a subsistence based on small farms, as is the case of San Isidro, Cerro Mero, Julcuy, Platanales and El Pital. The site known as Guale, where the Agua Blanca tourist facility is located, stands out, as it manages to achieve a certain level of sustainable development with respect to the enhancement of its natural and cultural resources from a community organisational base that is closely linked to the environment in a sustainable manner [

62,

78,

79].

Hence the importance of addressing agro-tourism as a key element for the sustainability of the socio-economic development of families and localities, which is one of the determining factors of the MNP as an agro-tourism destination, which can represent a demand profile for visitors interested in this type of tourism that guarantees security and unique and unrepeatable experiences.

2.2. Research Methods

The research was conducted from 15 March to 30 November 2023. It offers a mixed approach combining qualitative and quantitative research, which made it possible to analyse the problem starting from a premise, in order to reach precise conclusions on the studied topic. Consultations with specialists in the field of tourism and the formation of focus groups with the actors involved in rural tourism were considered.

In the discussion groups, some institutions of the territory participated, such as: Ministry of Tourism, Ministry of Agriculture and Ministry of Environment, for the identification and evaluation of the conceptual elements and practical experiences related to the research.

The research aims to provide theoretical assessments on the relevance of sustainable agrotourism within the boundaries of the PNM as an environmental option for participatory governance, which represents a development alternative called to become a key economic activity based on the use of endogenous resources, capable of replacing the variants of extractivist economy polluting the environment, to reduce the poverty gap and social precariousness in the localities that are located within the boundaries of the park.

The research is based on the deductive method that made it possible to appreciate the research problem, contextualise and reinforce the general theories linked to sustainable agro-tourism in the conditions of protected areas, operationalise the variables, their dimensions and indicators, carry out a statistical analysis of the data and reach precise conclusions on the significance of sustainable agro-tourism for environmental development and the governance of the local communities located within the boundaries of the MNP.

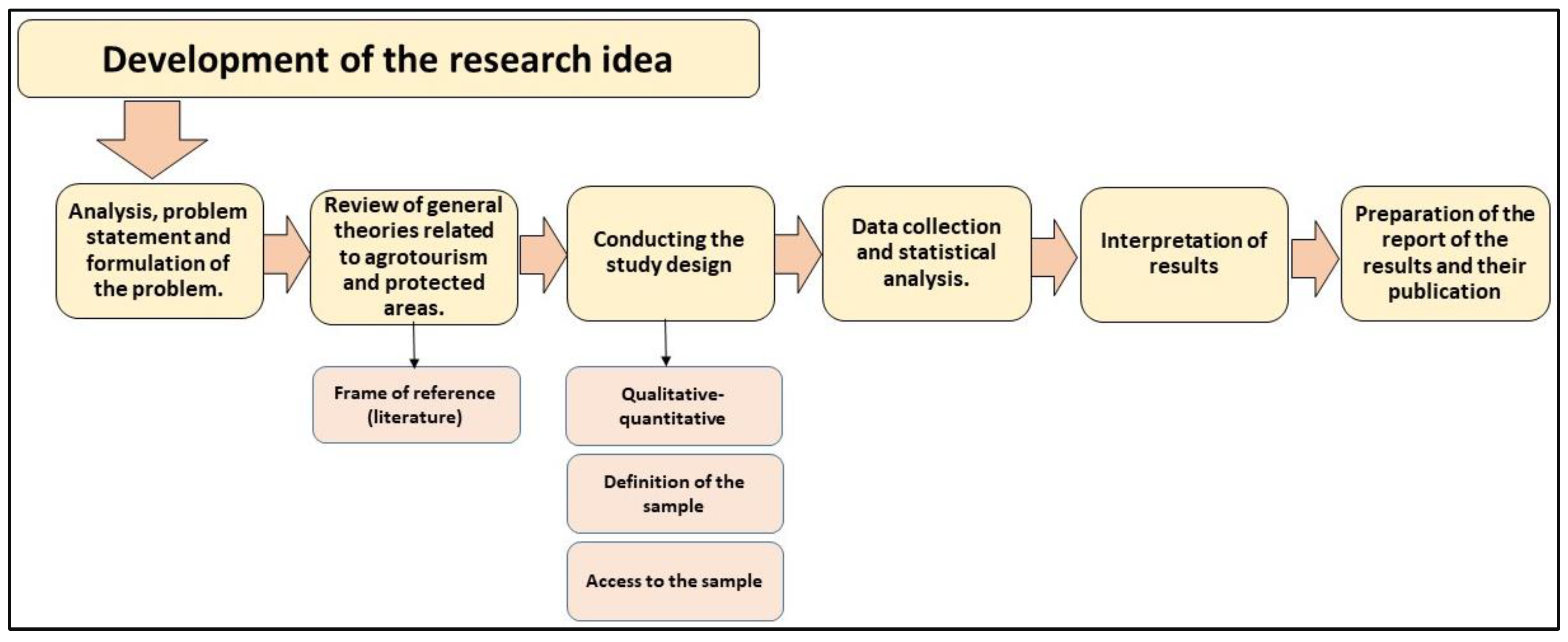

Figure 5 presents the diagram of the methodology applied for the research.

The research is deductive, analytical, descriptive and explanatory, which allowed the analysis of the literature consulted to discover the significance of sustainable agro-tourism in the context of protected areas. This made it possible to integrate the contributions of qualitative and quantitative analyses in the treatment and processing of the results of the surveys carried out with families living within the boundaries of the PNM.

Among the techniques applied was the historical-logical analysis that allowed the examination of tourism development in Ecuador from its beginnings as an economic activity and the emergence of agro-tourism as an alternative for less favoured rural communities.

The systematic review of literature and primary source documents allowed for the analysis of scientific articles, theses, books and primary source documents related to the topic of study from its different conceptual denominations. The selection of documents included a rigorous review of the related literature, with a special focus on publications from 2018 to 2022. Descriptive statistical analysis using the statistical package for social sciences SPSS version 22 was used in the study.

A structured survey was applied to a non-probabilistic sample of 30 volunteers linked to tourism management in the territory, of which 10 correspond to the tourism sector of the MNP and 20 tourism stakeholders in the territory of the province of Manabí, as well as 20 tourists enjoying the tourism products of Agua Blanca and Los Frailes beach, with the aim of verifying the significance of sustainable agro-tourism activity for community development, poverty reduction and the precariousness of families in the specific conditions of protected areas. The instruments were applied throughout the year 2023.

The survey for tourists consisted of a semantic differential related to the indicators of sustainable agrotourism and was elaborated in Spanish, English and French, in order to facilitate its application and processing.

The structured survey for the actors of the tourism sector in the territory consisted of a Likert scalogram on the indicators of sustainable agrotourism in the specific conditions of the MNP where: 1 meant the highest degree of disagreement and 5 meant the highest degree of agreement on the indicators to be evaluated.

A mixed research approach relevant to the nature of the object of study was used and the strengths of the qualitative and quantitative approach were integrated [

80].

3. Results

3.1. Profile of the Participants

All respondents selected for the sample participated actively. 57% of the participants are male and 43% are female. 32% had completed higher education, 55% had basic general education and baccalaureate and 13% had basic education. In terms of age, 86.5% were aged between 21 and 35.

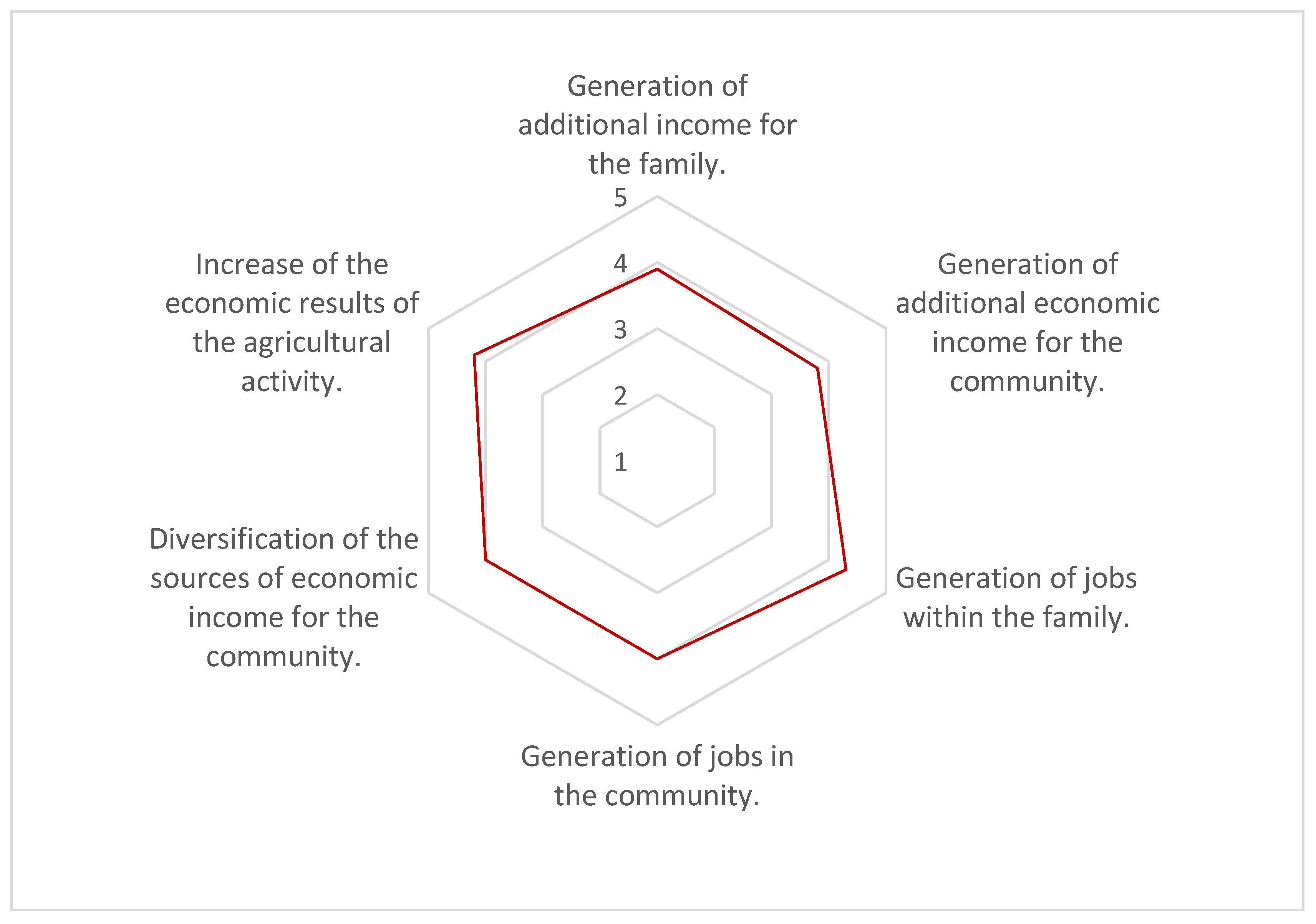

Table 1 shows the results of the survey carried out among the tourism actors in the territory, on the valuation of the economic indicators of sustainable agro-tourism in the conditions of the protected area (PNM).

Figure 6 shows evidence of the above by reflecting the average ranges related to the valuations given by the tourism stakeholders of the territory on the economic indicators of sustainable agrotourism.

It can be seen that 79% of the tourism stakeholders surveyed agree that sustainable agro-tourism in the context of protected areas generates additional economic income and jobs for families and the community, as well as becoming an element that diversifies the sources of economic income at the local level, thus reducing poverty, improving living conditions and increasing the economic results of local agricultural activities. Despite this, 9.3% disagree and 12% are indifferent, which may be due to a lack of knowledge and preparation of some tourism actors about the economic impact of agro-tourism for families and the community.

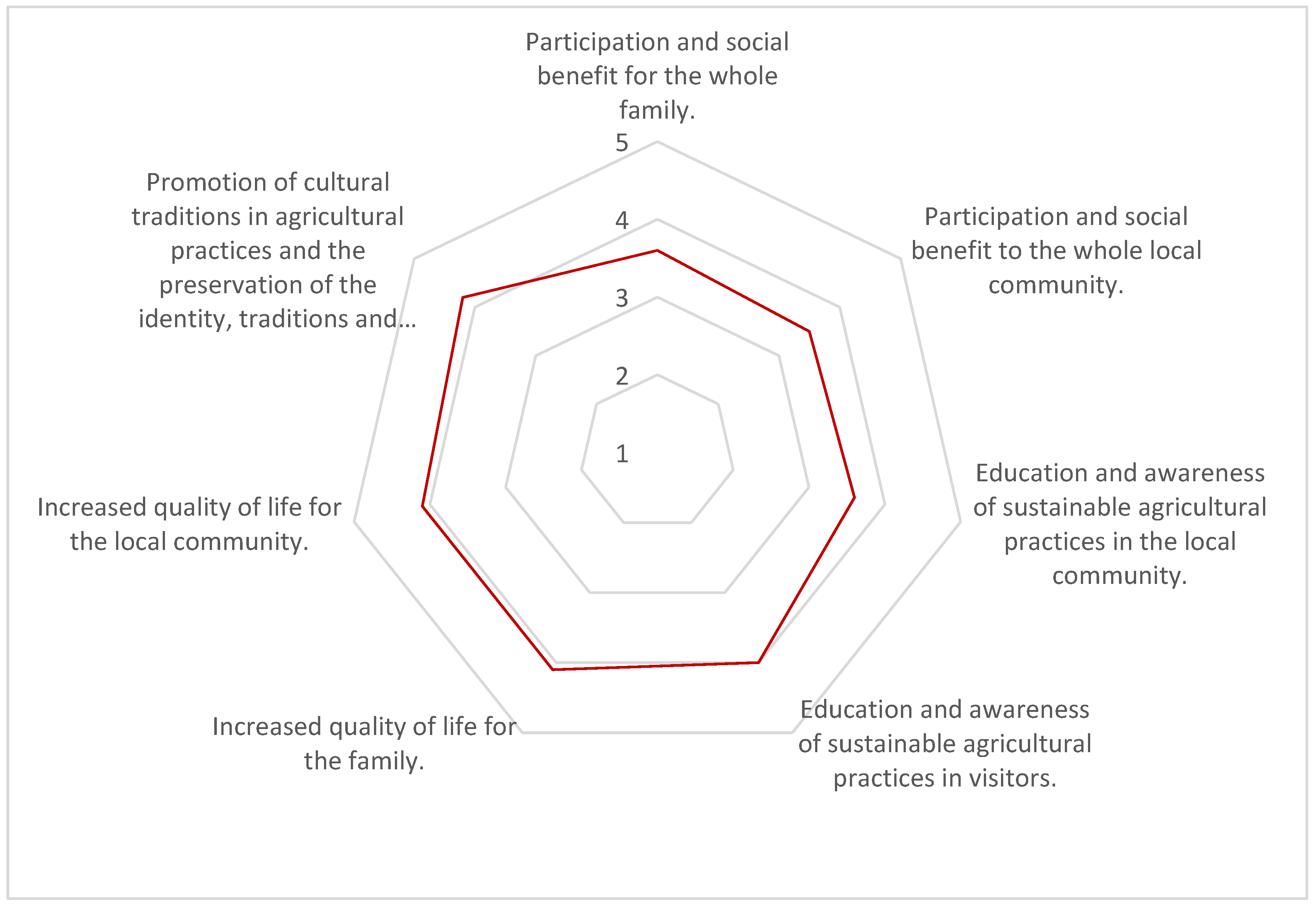

Table 2 shows the results of the survey of tourism actors in the territory, on the valuation of the social indicators of sustainable agrotourism in the conditions of the protected area (PNM).

Figure 7 shows a graphical analysis of the average ranges of the ratings given by tourism stakeholders in the territory on the social indicators of sustainable agrotourism.

The results of the survey of tourism stakeholders in the territory on the valuation of social indicators show that 68% of the surveyed tourism stakeholders agree with the criteria that agro-tourism involves participation and socially benefits the local family and society, that agro-tourism promotes education and awareness of sustainable agricultural practices in the local community and visitors, as well as that agro-tourism promotes the increase of the quality of life of the local family and the local community. However, 16.6% disagree and 15.6% are indifferent to this. This problem may be due to the low level of preparation of some tourism actors about the social impact of agro-tourism for the families, the community and the visitors themselves.

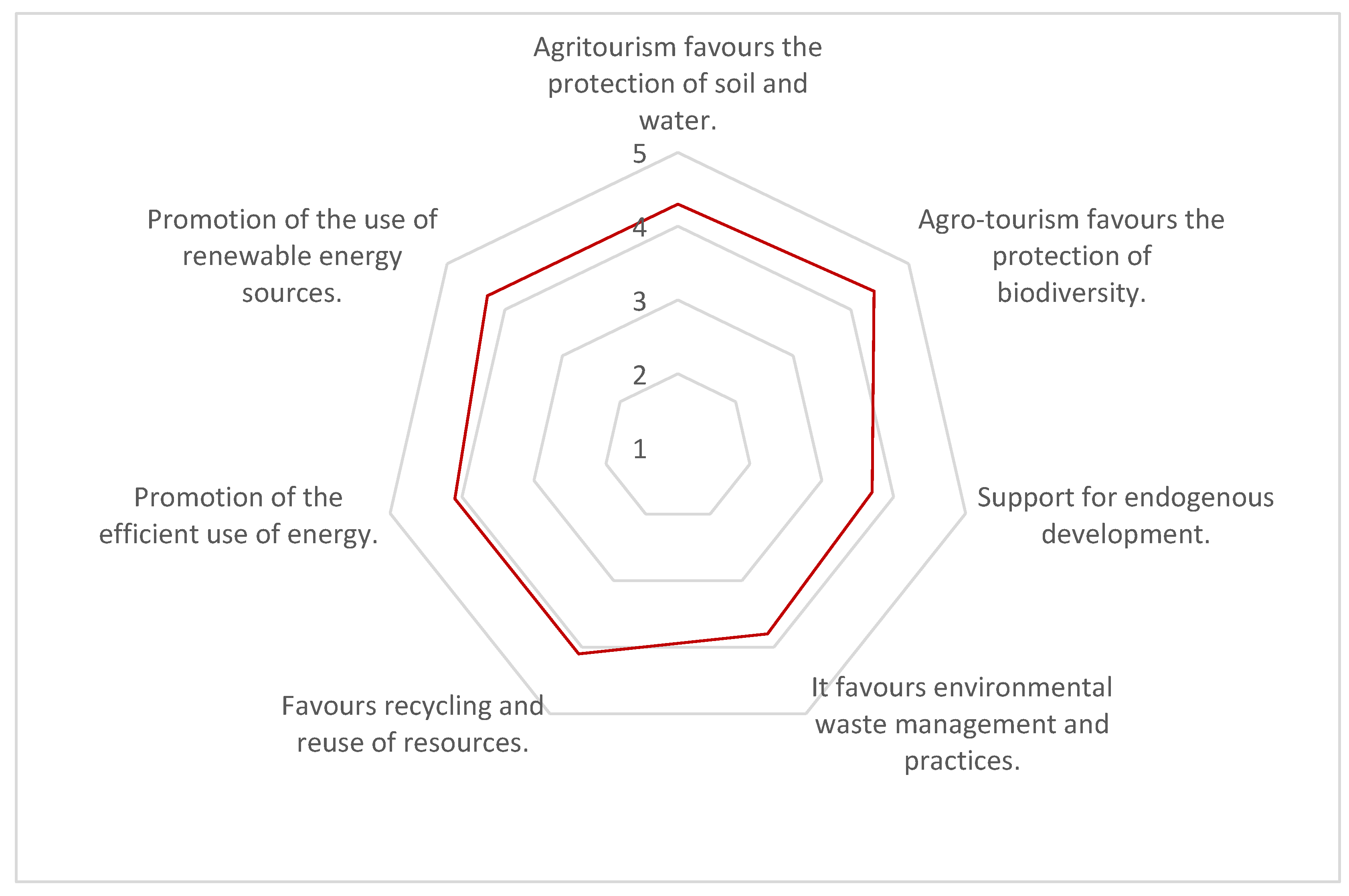

Table 3 shows the results of the analysis of the data from the survey of tourism actors in the territory, on the valuation of the environmental indicators of sustainable agro-tourism in the conditions of the protected area (PNM).

Figure 8 shows a graphical analysis related to the average ranges of the ratings given by the tourism stakeholders of the territory on the environmental indicators of sustainable agrotourism.

The results of the survey showed that 78.4% of the tourism stakeholders consider that agro-tourism favours the protection of soil, water and biodiversity, is based on the notion of endogenism, favours environmental practices and management of waste, recycling and reuse of resources, promotes the efficient use of energy and the use of renewable sources. However, 9.6% disagree and 12% are indifferent. This problem may be influenced by the deficient level of preparation that some tourism actors have regarding the environmental impact of sustainable agro-tourism in the territory.

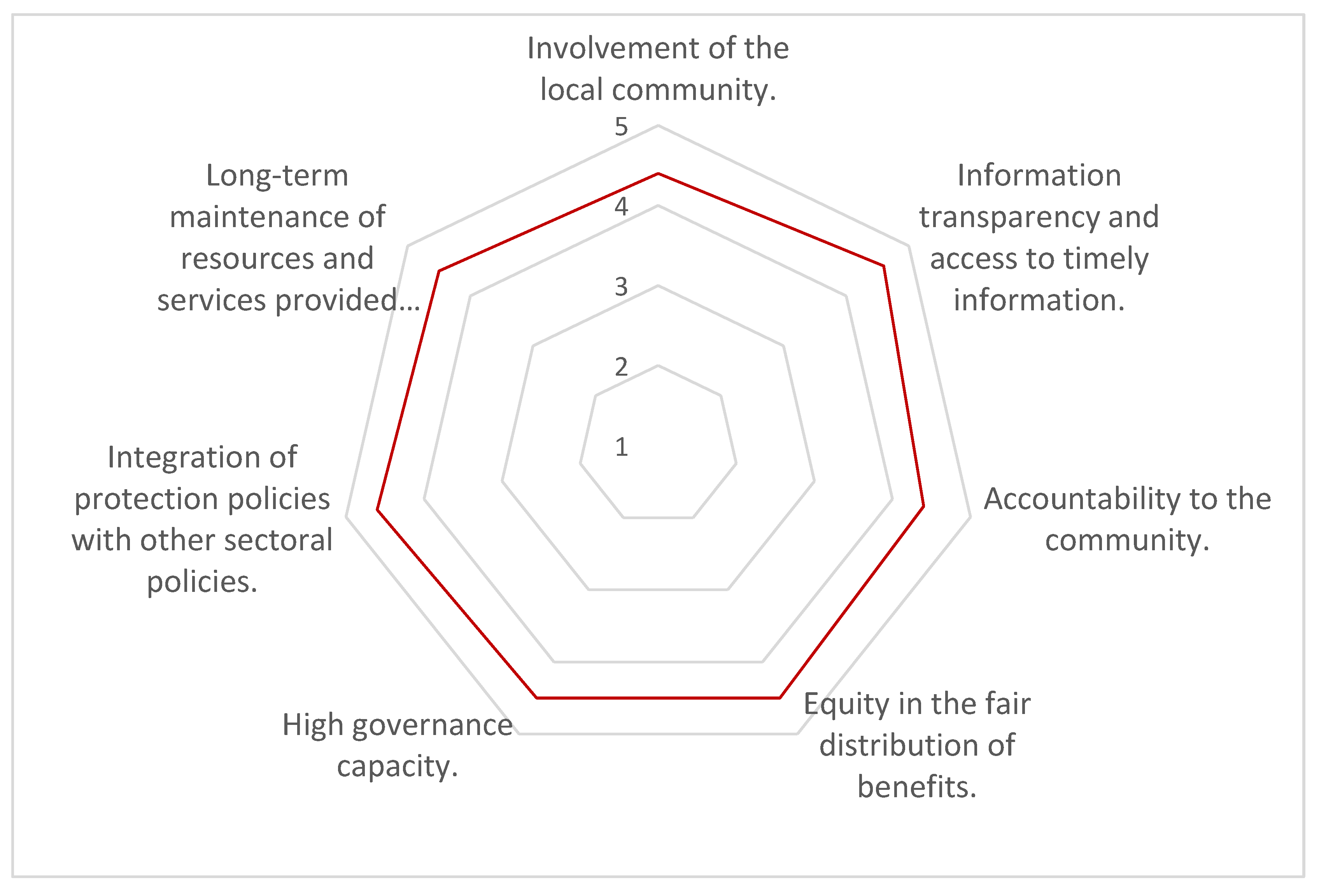

Table 4 shows the results of the analysis of the data from the survey of tourism stakeholders in the territory, on the evaluation of the governance indicators of sustainable agrotourism in the conditions of the protected area (PNM).

Figure 9 shows a graphical analysis of the average ranges of the ratings given by the tourism stakeholders of the territory on the governance indicators of sustainable agrotourism.

The results of the survey showed that 93% of the respondents consider that the involvement of the local community in the agro-tourism activity makes it feasible and favours appropriate decision-making. They point out that transparency and access to timely information facilitates the proper management of the enterprise. They see accountability to the community as a monitoring tool for continuous improvement. They appreciate the equitable and fair distribution of benefits as an element that enables the strengthening of performance in agrotourism. Governance as an expression of capacity for the fulfilment of environmental protection objectives. They consider of great importance the integration of protection policies with those of a sectoral nature to guarantee the adequate performance of sustainable agro-tourism management, as well as the long-term maintenance of the resources and services of the protected area in the interest of guaranteeing sustainable agro-tourism.

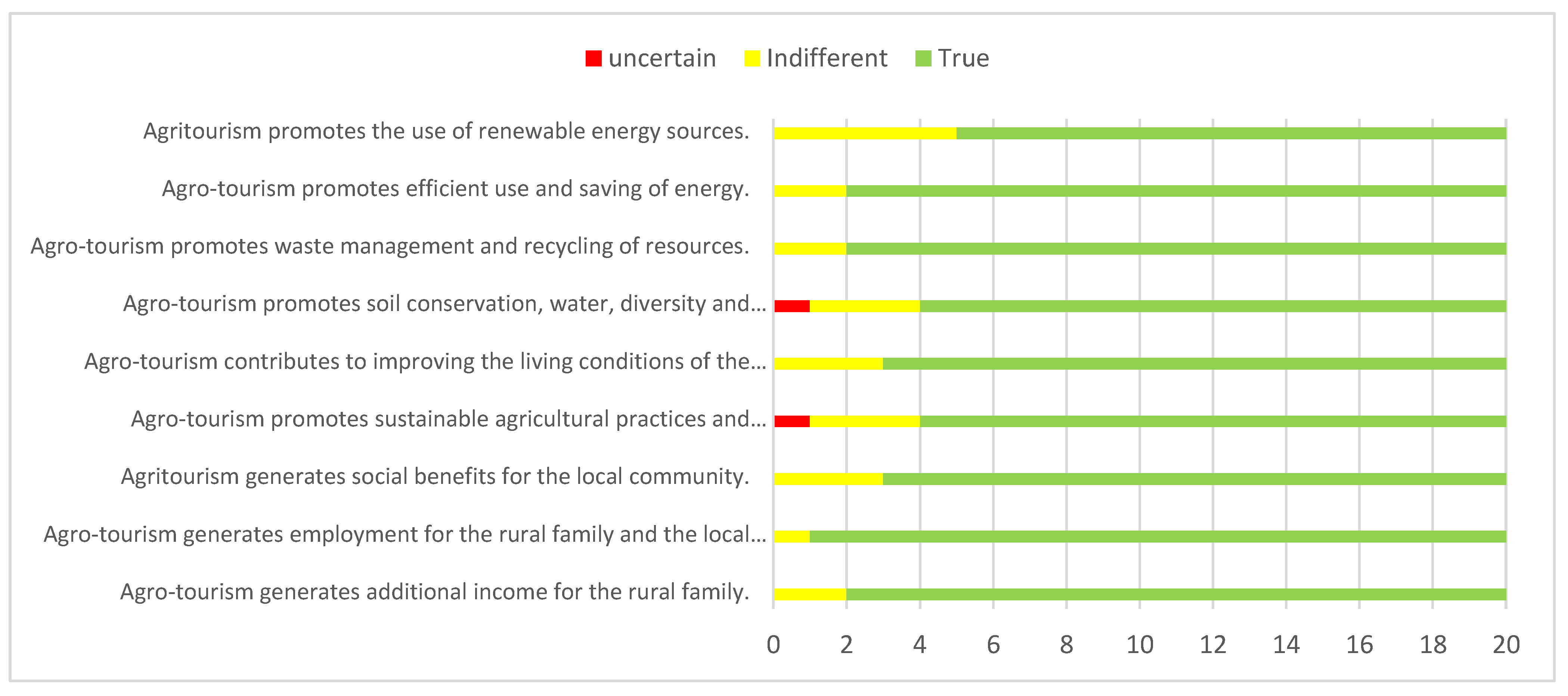

Table 5 shows the results of the semantic differential applied to the sample of tourists on the valuation of the indicators of sustainable agrotourism in the conditions of the protected area (PNM).

Figure 10 shows a graphical analysis related to the semantic differential on the valuation of the indicators of sustainable agrotourism by tourists.

The results of the survey showed that 85.6% of the surveyed tourists consider that sustainable agro-tourism in the context of protected areas is able to generate additional economic income to the rural family, generate jobs to the family and the community, to bring social benefits to the community, promote sustainable agricultural practices and environmental protection, contribute to improving the living conditions of the local community, promote the conservation of soil, water, diversity and endogenism, encourage proper waste management and recycling of resources, efficient use and saving of energy, as well as the use of renewable sources. However, 13.3% were indifferent and 1.1% disagreed.

4. Discussion

Hernández-Mogollón, Campón-Cerro, Leco-Berrocal, and Pérez-Diaz argue that agrotourism represents an important potential to boost the sustainable diversification of agricultural production, but faces challenges that must be overcome, such as income generation, landscape preservation and rural heritage conservation [

81]. Aspects that must be considered with particular importance when analysing agro-tourism in the context of protected areas.

Nature tourism and rural tourism have a close relationship with agrotourism, which can be clearly seen when it comes to tourism activities in protected areas. Both modalities operate in the context and experiences of the natural environment and rural life. They are preferred modes of tourism for visitors who want to get away from urban life and enjoy outdoor activities in a healthy natural environment. It includes trekking and participation in the economic support of rural life. Agro-tourism can be a powerful tool for sustainable rural development and the promotion of environmental conservation and local culture [

81]. In accordance with the protection objectives required in protected areas.

The complex and multifaceted relationship between agriculture, tourism, nature tourism, rural tourism and sustainable agro-tourism can be better understood through various studies that explore these issues from different perspectives. The integration of agriculture with tourism especially through agro-tourism promotes and encourages sustainable development of rural areas. Agritourism allows visitors to experience rural life first-hand in an unforgettable way and to participate in agricultural activities, thus diversifying sources of income for farmers and promoting the protection of the environment and local culture [

82]. In line with the objectives pursued in protected areas.

Agritourism promotes sustainable rural development by combining agriculture and tourism to promote economic sustainability, employment generation and the strengthening of local identity [

83]. Proper agrotourism management promotes sustainable agriculture and rural development to create economic opportunities that favour farmers, local communities and environmental preservation [

84].

Effective agrotourism management requires the exercise of effective stewardship of economic management and appropriate use of resources, equitable distribution of benefits and includes the reduction of environmental impact for the benefit of the community [

85]. Trade-offs between performance, profitability and social, human and environmental performance need to be considered [

86].

In countries such as Hungary, similar measures are applied to the agrotourism modality by modifying the National Tourism Development Strategy 2.0 with the aim of implementing a type of rural tourism, which is sustainable and of high quality, benefits the local population and promotes integrated rural development [

87]. To complete the initiative, the direct participation of tourists and visitors in agricultural work should be introduced, which is conducive to raising education, awareness of visitors and the community about sustainable agricultural practices and respect for the environment. These aspects should be considered with special attention when analysing agro-tourism in the context of protected areas.

The integration of agriculture with tourism through sustainable agro-tourism constitutes a promising way for socially responsible performance of sustainable rural development. The integration of agriculture and tourism allows the diversification of income sources for farmers and the socio-economic development of local communities, promotes environmental protection, local culture and contributes to the socio-economic development of rural areas. In Russia, its contribution to sustainable rural development is analysed by proposing a concept for its development based on the analysis of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats [

88]. This constitutes a contribution to the application of agro-tourism in the context of protected areas.

The development of agro-tourism represents a significant impact for the local community economy. Its application favours the diversification of agricultural production, increasing competitiveness and promoting the development of tourism infrastructures. It demonstrates that it is an important source of income for farmers and contributes to the socio-economic and environmental development of rural localities, especially those located within protected areas [

89].

5. Conclusions

Despite the need to promote the development of agricultural production and the socio-economic progress of rural areas in Ecuador, there is still no consolidated tourism product in the agro-tourism modality, which is due to the lack of knowledge and the weak institutional support for the activity, which is more accentuated in the rural context of protected areas.

Ecuador's protected areas are located in rural areas characterised by poverty, unemployment and precariousness, with low technological investment in agriculture, livestock and other activities such as artisanal fishing and the production of handicrafts.

Through the method of scientific observation and the surveys applied, the fieldwork revealed that most of the tourism actors surveyed recognise the potential of sustainable agro-tourism in the context of protected areas as a viable solution for the diversification of economic income that allows for the reduction of poverty and the improvement of the living conditions of the community. They agree that it socially benefits the family and the local community through education and awareness of sustainable agricultural practices, favours the conservation of soil, water and biodiversity, with the sustenance of resources in an endogenous communitarian and participatory notion, which favours an adequate management and recycling of resources, energy efficiency and the use of renewable sources.

The application of the semantic differential to tourists revealed that most of them consider sustainable agrotourism in the context of protected areas as a form of tourism that generates additional economic income for the rural family, promotes employment, provides social benefits for the community by promoting sustainable agricultural practices, environmental protection, the appropriate use of energy resources and the use of renewable energy sources.

Agro-tourism in the context of protected areas is characterised by the close linkage of tourism leisure with the practice of activities in rural environments and other rural work, as well as the notion of endogenous rural development to satisfy the demand for tourism resources, as conditions that allow sustainable tourism to be harmonised with the requirements established for protected areas, in the interest of achieving sustainable community development in the rural territory through the implementation of tourism activities, which implies the need to distinguish the type of sustainable agro-tourism, which pursues the satisfaction of visitors' expectations through rewarding experiences, the protection of the environment, the socio-economic benefit of the host communities and the respect of the culture and traditions of the territory, without leaving a negative footprint for future travellers.

Sustainable agrotourism in the context of protected areas is capable of imprinting an integral and holistic synergistic effect on tourism activity, by integrating agricultural work and the life experiences of the peasant family, which makes it possible to generate a novel result that is superior from a qualitative and quantitative point of view, allowing for the reduction of poverty, the precariousness of rural life, creating better conditions for the environmental preservation of the protected territory and contributing to the fulfilment of the Sustainable Development Goals and the 2030 Agenda.

The relevance of the research results lies in the nature of the results that allow the assessment of the relevance of sustainable agrotourism in the context of protected areas as an interesting alternative, which enables the diversification of economic income for producers, allows the reduction of poverty, guarantees a greater supply of jobs and reduces the precariousness of rural territory, with the creation of better conditions that favour compliance with the established environmental protection measures and regulations.

The research seeks to reopen the debate on the relevance of agrotourism in the context of protected areas, which due to environmental regulations are limited to undertake other forms of tourism that allow them to diversify sources of income, generate jobs, improve living conditions and contribute to the sustainable development of rural communities.

The main limitation of the study is that, despite the economic, social, cultural and environmental benefits that agrotourism offers, the reality is that it lacks adequate infrastructure, lack of preparation on the part of agrotourism operators and actors, which implies the need for education and training for farmers and the need to articulate government support policies that encourage the promotion and promotion of agrotourism as an effective tool for sustainable rural development. This is influenced by the lack of integration of actors in the ministries of agriculture, tourism, water and environment, as well as the participation of government bodies, articulation with communities and their involvement in endogenous development projects for sustainable agrotourism.

It is recommended that future studies continue to deepen the debate on agrotourism in the context of protected areas, based on new experiences that allow a more complete and specific analysis of the socio-economic, environmental and governance benefits and examples of good practices for achieving appropriate synergies between agriculture, tourism, environment, government and communities to enhance the endogenous development of sustainable agrotourism in host communities.

To develop future research that delves into innovation and the role of the technological revolution in sustainable agrotourism projects based on the development of Agriculture 4.0 and the use of the 4Rs in agriculture, a challenge that must be incorporated into sustainable agrotourism projects and its implication for moving towards smart tourism destinations in sustainable agrotourism.

Author Contributions

The manuscript has a single author who has made the following contributions. Conceptualisation, software, validation, formal analysis, research, resourcing, data curation, original writing, drafting, writing: revising and editing, visualisation, supervision, project management, securing funding. The author has read and accepted the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded from the author's own resources, for which he had his own budget of USD 4,000.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data can be provided by the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the authorities of the Universidad Estate del Sur de Manabí for their collaboration during the research that made this work possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that he has no conflicts of interest.

References

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Sustainable tourism: Sustaining tourism or something more? Tourism Management Perspectives, 25(1), 2018. 157-160. [CrossRef]

- Eagles Paul F. J., Stephen F. McCool y Christopher D. Haynes. Sustainable tourism in protected areas Planning and management guidelines. United Nations Environment Programmed, World Tourism Organization and IUCN – World Conservation Union. 2002. https://www.institutobrasilrural.org.br/download/20120219144738.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Pelegrín Entenza, Norberto, Antonio Vázquez Pérez, and Analién Pelegrín Naranjo. "Rural agrotourism development strategies in less favored areas: The case of Hacienda Guachinango de Trinidad." Agriculture 12.7 (2022): 1047. [CrossRef]

- Gauna Ruiz de León, Carlos. Percepción de la problemática asociada al turismo y el interés por participar de la población: caso Puerto Vallarta. El periplo sustentable 33, 2017: 251-290. https://rperiplo.uaemex.mx/article/view/4858 (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Castiñeira, Carlos Javier Baños. La oferta turística complementaria en los destinos turísticos alicantinos: implicaciones territoriales y opciones de diversificación. Investigaciones Geográficas (Esp) 19, 1998: 85-103. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/176/17654249005.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Baggio, R.; Scott, N.; Cooper, C. Improving tourism destination governance: A complexity science approach. Tour. Rev. 2010, 65, 51–60. [CrossRef]

- Brouder, P.; Teoh, S.; Salazar, N.B.; Mostafanezhad, M.; Pung, J.M.; Lapointe, D.; Higgins-Desbiolles, F.; Haywood, M.; Hall, C.M.; Clausen, H.B. Reflections and discussions: Tourism matters in the new normal post COVID-19. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 735–746. [CrossRef]

- Naranjo Llupart, M. R. Theoretical Model for the Analysis of Community-Based Tourism: Contribution to Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10635. [CrossRef]

- Vera-Rebollo, José Fernando.; Carlos Javier Baños Castiñeira. Turismo, territorio y medio ambiente. La necesaria sostenibilidad. Universidad de Alicante. 2004. https://rua.ua.es/dspace/bitstream/10045/132322/1/Vera_Banos_2004_PapEconEsp.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Chassang, L.; Hsieh, C.-J.; Li, T.-N.; Hsieh, C.-M. Feasibility Assessment of Stakeholder Benefits in Community-Based Agritourism through University Social Responsibility Practices. Agriculture 2024, 14, 602. [CrossRef]

- Gordan, M.-I.; Popescu, C.A.; C˘alina, J.; Adamov, T.C.; M˘anescu, C.M.; Iancu, T. Spatial Analysis of Seasonal and Trend Patterns in Romanian Agritourism Arrivals Using Seasonal-Trend Decomposition Using LOESS. Agriculture 2024, 14, 229. [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, G. El turismo sostenible comunitario en Puerto el Morro: Análisis de su aplicación e incidencia económica. Univ. Soc. 2019, 11, 289–294. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2218-36202019000100289 (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Tite, G.M.; Carrillo, D.M.; Ochoa, M.B. Turismo accesible: Estudio bibliométrico. Tur. Soc. 2021, 28, 115–132. [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, R., & Packer, J. Nature-based tourism and learning: a review of the literature. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 2002, 10(5), 399-418.

- Blanco, Marvin, & Hernando Riveros. El agroturismo como diversificación de la actividad agropecuaria y agroindustrial." Estudios agrarios 49 (2011): 117-128. https://www.academia.edu/download/32250010/el_agroturismo_como_-_Marvin_Blanco_M.pdf.

- Alcubilla Ferrer, Diego. Análisis estadístico de las viviendas de uso turístico en España. Tesis de grado. Universidad de Valladolid España. 2022. https://uvadoc.uva.es/handle/10324/54815 (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- Morales Zamorano, Luis A., et al. "Agroturismo y competitividad, como oferta diferenciadora: el caso de la ruta agrícola de San Quintín, Baja California." Revista mexicana de agronegocios 37. 2015, 185-196. https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/226159/?v=pdf (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Karampela, S., Andreopoulos, A. y Koutsouris, A. “Agro”, “Agri”, or “Rural”: The Different Viewpoints of Tourism Research Combined with Sustainability and Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2021, 13(17), 9550; [CrossRef]

- Barriga, Andrea Muñoz. Percepciones de la gestión del turismo en dos reservas de biosfera ecuatorianas: Galápagos y Sumaco. Investigaciones Geográficas, Boletín del Instituto de Geografía 2017. 93, 2017: 110-125. [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C., S. Xu, C. Gil-Arroyo and S.R. Rich. Agritourism, farm visit, or...? A branding assessment for recreation on farms. J. Travel Res. 55(8), 2015. 1094-1108. Terms and conditions | Taylor & Francis Online (tandfonline.com). [CrossRef]

- Che, D., Veeck, A. y Veeck, G. Sostener la producción y fortalecer el producto agroturístico: vínculos entre los destinos agroturísticos de Michigan. Agric Hum Values 22, 225–234. 2005. [CrossRef]

- Kizos, Tanasis., and Iosifides, Theodoros. The Contradictions of Agrotourism Development in South European. Society and Politics 12(1), 2007. 59-77. [CrossRef]

- Montes, Carlos.; Osvaldo Sala. La Evaluación de los Ecosistemas del Milenio. Las relaciones entre el funcionamiento de los ecosistemas y el bienestar humano. Ecosistemas 2007, 16, 3. http://revistaecosistemas.net/index.php/ecosistemas/article/view/120 (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68. [CrossRef]

- Cummins, R.A.; Nistico, H. Maintaining life satisfaction: The role of positive cognitive bias. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 37–69. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1015678915305 (accessed on 9 March 2024).

- Diener, E. A. Value based index for measuring national quality of life. Soc. Indic. Res. 1995, 36, 107–127. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF01079721(accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Tuula, H.; Tuuli, H. Wellbeing and sustainability: A relational approach. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 23, 167–175. [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, C. Fortaleciendo Redes de Turismo Comunitario. REDTURS Bolivia No 4. 2007. Available online: https://www.nacionmulticultural.unam.mx/empresasindigenas/docs/2053.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Frías, Margarita Capdepón. Las áreas protegidas privadas como escenarios para el turismo. Implicaciones y cuestiones clave. Cuadernos geográficos de la Universidad de Granada 60.2, 2021: 72-90. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=8001811 (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Murcia García, Cecilia, John Freddy Ramírez-Casallas, and Oscar Camilo Valderrama Riveros. "La participación ciudadana, factor asociado al desarrollo del turismo sostenible: caso ciudad de Ibagué (Colombia)." Anales de Geografía de la Universidad Complutense. Vol. 40. No. 1. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Shibia, Mohamed G. Determinants of attitudes and perceptions on resource use and management of Marsabit National Reserve, Kenya. Journal of Human Ecology 30.1. 2010: 55-62. [CrossRef]

- Chiedza, Ngonidzashe Mutanga.; Sebastián, Vengesayi.; Nunca Muboko.; Edson, Gandiwa. Towards harmonious conservation relationships: A framework for understanding protected area staff-local community relationships in developing countries. Journal for Nature Conservation 25. 2015: 8-16. [CrossRef]

- Mir, Zaffar Rais.; Athar, Noor.; Bilal, Habib.; Gopi, Govindan Veeraswami. Actitudes de la población local hacia la conservación de la vida silvestre: un estudio de caso del valle de Cachemira. Investigación y desarrollo de montañas 35.4, 2015: 392-400. [CrossRef]

- Perry, Elizabeth E., Mark D. Needham y Lori A. Cramer. Confianza, similitud, actitudes e intenciones de los residentes costeros con respecto a las nuevas reservas marinas en Oregón. Sociedad y recursos naturales 30.3, 2017: 315-330. [CrossRef]

- Mengesha, Girma.; Yosef, Mamo.; Kefyalew Sahle.; Chris Elphick.; and Afework Bekele. Effects of land-use on birds’ diversity in and around Lake Zeway, Ethiopia. Journal of Science & Development 2, 2014: 2. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mamo-Yosef/publication/293332579_Effects_of_land-use_on_birds'_diversity_in_and_around_Lake_Zeway_Ethiopia/links/56b75fb008aebbde1a7df0fa/Effects-of-land-use-on-birds-diversity-in-and-around-Lake-Zeway-Ethiopia.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Dafau Arjona, Ivonne Lizeth. Actitudes ambientales de la sociedad hacia el aprovechamiento turístico sustentable de la Laguna de Términos. MS thesis. Universidad de Quintana Roo, 2019. http://risisbi.uqroo.mx/handle/20.500.12249/3135(accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Ngonidzashe Mutanga, Chiedza; Sebastián, Vengesayi; Nunca, Muboko. Community perceptions of wildlife conservation and tourism: A case study of communities adjacent to four protected areas in Zimbabwe. Tropical Conservation Science 8.2, 2015: 564-582. [CrossRef]

- Tilahun, Belete.; Kassahun, Abie.; Asalfew, Feyisa.; Alemneh, Amare. Actitud y percepciones de las comunidades locales hacia el valor de conservación del parque nacional gibe Sheleko, suroeste de Etiopía. Economía agrícola y de recursos: Revista electrónica científica internacional 3.2, 2017: 65-77. DOI: . [CrossRef]

- Caviedes-Rubio, Diego Iván.; Alfredo Olaya-Amaya. Ecoturismo en áreas protegidas de Colombia: una revisión de impactos ambientales con énfasis en las normas de sostenibilidad ambiental." Revista Luna Azul 46, 2018: 311-330. [CrossRef]

- Macura, Biljana.; Francisco Zorondo Rodríguez.; Mar Grau Satorras.; Kathryn Demps.; María Laval.; Claude A.; García, Victoria Reyes García. Actitudes de la comunidad local hacia los bosques fuera de las áreas protegidas en la India. Impacto de la conciencia jurídica, la confianza y la participación". Ecología y sociedad 16.3, 2011. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26268928 (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Fox, H. K.; Molina, A. C.; Swearingen, T. C. An Interrupted Time Series Approach to Assessing the Impacts of Marine Protected Areas on Recreational Fishing License Sales, 32 (12), 2022. 1970-1982. [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, Brián G. Tras una definición de las áreas protegidas: Apuntes sobre la conservación de la naturaleza en Argentina. Revista Universitaria de Geografía 27.1, 2018: 99-117. http://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?pid=S1852-42652018000100006&script=sci_arttext (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Oli, Krishna Prasad, Sunita Chaudhary, and Uday Raj Sharma. "Are governance and management effective within protected areas of the Kanchenjunga landscape (Bhutan, India and Nepal)." Parks 19.1. 2013: 25-36. https://npshistory.com/newsletters/parks/parks-1901.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Holdgate, Martin. The green web: a union for world conservation. Routledge, 2014. https://www.routledge.com/The-Green-Web-A-Union-for-World-Conservation/Holdgate/p/book/9781853835957(accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Ceruti, María Constanza. "Yellowstone. Patrimonio y paisaje." Estudios del Patrimonio Cultural 15. 2016: 40-55. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5720561 (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- De Contreras, María Estella Quintero. Una mirada a los Parques Nacionales en el mundo. Caso: Parques nacionales en Venezuela y en el Estado Mérida. Visión Gerencial 2. 2011: 405-418. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/4655/465545891014.pdf (accessed on 1º June 2024).

- Eagles, Paul FJ, Stephen F. McCool, and Christopher D. Haynes. Turismo sostenible en áreas protegidas. Organización Mundial del Turismo, 2003. https://www.institutobrasilrural.org.br/download/20120219144738.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Kelleher, Graeme. Directrices para áreas marinas protegidas. Ed, Comisión Mundial de Áreas Protegidas (CMAP). 1999. [CrossRef]

- Dudley, Nigel. Directrices para la aplicación de las categorías de gestión de áreas protegidas. Ed. Iucn, 2008. https://books.google.es/books?hl=es&lr=&id=xLZKJE_bpzgC&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=proceso+evolutivo+del+concepto+y+significado+de+las+%C3%A1reas+protegidas+&ots=C27pSSy3f7&sig=fT7Nc-mm6loDsXjh1lINzkScn1s#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- Asamblea Nacional Legislativa. Código Orgánico del Ambiente. Registro Oficial Suplemento 983 de 12-abr.-2017 Estado: Vigente. https://www.emaseo.gob.ec/documentos/lotaip_2018/a/base_legal/Codigo_organico%20de%20ambiente_2017.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Cifuentes, Miguel.; Arturo, Izurieta.; Helder, Henrique de Faria. Medición de la efectividad del manejo de áreas protegidas. Vol. 2. 2000. WWF: IUCN: GTZ, 2000. 105 p., 22 cm. https://awsassets.panda.org/downloads/wwfca_measuring_es.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2024).

- Zambrano, R., and M. López. Breve historia y perspectivas para el futuro del Sistema Nacional de Áreas Protegidas del Ecuador (SNAP). VIII Jornadas Académicas Turismo y Patrimonio, Compartiendo lo nuestro con el mundo. Memorias Contribuciones Científicas. Memorias 42. 2015. https://www.academia.edu/download/43559540/Memorias_de_las_VIII_Jornadas_de_Patrimonio_yTurismo._ESPAM_MFL_Final_opt.pdf#page=42 (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- ONU. Convenio sobre la diversidad Biológica. Organización de las Naciones Unidas 1992. https://www.cbd.int/doc/legal/cbd-es.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Márquez Guerra, José Francisco. Reglamentos indígenas en áreas protegidas de Bolivia: el caso del Pilón Lajas. Revista de derecho 46, 2016: 71-110. [CrossRef]

- Sandwith, Trevor.; Lawrence, Hamilton.; David, Sheppard. Protected areas for peace and co-operation. Best practice protected area guidelines. Ed. Adrian Phillips, series 7 2001. http://web.bf.uni-lj.si/students/vnd/knjiznica/Skoberne_literatura/gradiva/zavarovana_obmocja/IUCN_TBPA.pdf (Accessed on 13 January 2024).

- Íñiguez Dávalos, Luis Ignacio.; Jiménez Sierra, Cecilia Leonor.; Sosa Ramírez, Joaquín.; Ortega-Rubio, Alfredo. Categorías de las áreas naturales protegidas en México y una propuesta para la evaluación de su efectividad. Investigación y ciencia 22.60, 2014: 65-70. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/674/67431160008.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Green, Michael J. B.; James Paine. State of the World's Protected Areas at the End of the Twentieth Century. Ed. UICN. 1997. https://aquadocs.org/handle/1834/867 (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Hockings, Marc.; Sue, Stolton.; Nigel Dudley. Evaluating effectiveness: a framework for assessing the management of protected areas. Ed. UICN, No. 6. 2000. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:162233 (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- Hiernaux-Nicolas, D.; Cordero, A.; Duynen-Montijn, L. Imaginarios Sociales y Turismo Sostenible. Cuaderno de Ciencias Sociales 123; Sede Académica, Costa Rica. Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales FLACSO: San José, Costa Rica, 2002. Available online: http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/Costa_Rica/flacso-cr/20120815033220/cuaderno123.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Light, D.; Cretan, R.; Dunca, A.-M. Museums and transitional justice: Assessing the impact of a memorial museum on young people in post-communist Romania. Societies 2021, 11, 43. [CrossRef]

- Popescu, L.; Albă, C. Museums as a means to (re)make regional identities: The Oltenia museum (Romania) as case study. Societies 2022, 12, 110. http://doi.org/10.3390/soc12040110.

- Ruiz Ballesteros, E.; Solís Carrión, D. Turismo Comunitario en Ecuador Desarrollo y Sostenibilidad Social, 1st ed.; Abya-Yala: Quito, Ecuador, 2007; p. 333. Available online: https://animacionsociocultural2013.files.wordpress.com/2013/05/turismo-comunitarioen-ecuador.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Mendoza Montesdeoca, Iván, Manuel Rivera Mateos, and Yamil Doumet Chilán. Políticas públicas ambientales y desarrollo turístico sostenible en las áreas protegidas de Ecuador. Revista de Estudios Andaluces, 43, 2022. 106-124. DOI: . [CrossRef]

- Prieto, M. Espacios en Disputa: El turismo en Ecuador, 1st ed.; Flacso Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2011; p. 232. Available online: http://190.57.147.202:90/xmlui/handle/123456789/1881(accessed on 6 February 2024).

- Hiwasaki, L. Community-based tourism: A pathway to sustainability for Japan’s protected areas. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2006, 19, 675–692. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08941920600801090 (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Lepp, A. Residents attitudes towards tourism in Bigodi village, Uganda. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 876–885. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0261517706000483 (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Alaeddinoglu, F.; Can, A. S. Identification and classification of nature-based tourism resources: Western Lake Van basin, Turkey. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 19, 198–207. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J.; Blanco, K. Community-based ecotourism development ion the periphery of Belize. Curr. Issues Tour. 1999, 2, 226–243. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, T.; Gulden, T.; Cousins, K.; KRAEV, E. Integrating environmental, social and economic systems: A dynamic model of tourism in Dominica. Ecol. Model. 2004, 175, 121–136. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Zorn, E.; Farthing, L.C. Communitarian tourism. Hosts and mediators in Peru. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 673–689. [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, E.M. O turismo como agente de desenvolvimento social e a comunida de Guaraninas Ruínas Jesuíticas de Sao Miguel das Missoes. PASOS: Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2007, 5, 343–352. [CrossRef]

- Loor-Bravo, L.; Plaza-Macías, N.; Medina-Valdés, Z. Turismo comunitario en Ecuador: Apuntes en tiempos de pandemia. Rev. De Cienc. Soc. 2021, 27, 265–277. [CrossRef]

- Portilla Martínez, José Vicente. Agroturismo, una alternativa sostenible para el sector rural en Floridablanca, Santander. Human Review, 2022, Vol 12, Issue 6, p1. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=26959623&AN=170907156&h=%2BKRdqzDM2nk4cQR1TKSJrjI5%2F%2FhIdQtE5xDAxbGvgCufMy6jWUKxHfUJZIIv5GOw01fPTME5YnjjTzhYbmt68g%3D%3D&crl=c (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- Fuentes, Freddy Garaicoa. Ruth Montero Muthre. Sandra Rodríguez Bejarano. Karen León García. Agroturismo: Una alternativa sostenible para el desarrollo local en San Francisco de Milagro, Guayas, Ecuador. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar 7.2, 2023: 4768-4789. DOI: . [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Ana del Carmen Segura, Rene Nazareno Ortiz, and Gisselle Antonella Sánchez Segura. Agroturismo para el Desarrollo Sostenible en fincas ecuatorianas. Un estudio documental. Dominio de las Ciencias 7.4, 2021: 183. [CrossRef]

- Haro H, Jeniffer Roxana. Agroturismo y Turismo Sostenible en la comunidad de Tolóntag, parroquia Píntag, cantón Quito, provincia de Pichincha. Tesis de grado. Riobamba: Universidad Nacional de Chimborazo Ecuador., 2023. http://dspace.unach.edu.ec/handle/51000/11873 (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Caiza, Roberto, and Edison Molina. Análisis histórico de la evolución del turismo en territorio ecuatoriano. RICIT: Revista Turismo, Desarrollo y Buen Vivir 4, 2012: 6-24. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4180961 (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Represa, F., y Macías-Zambrano, L. H. Sostenibilidad social en Áreas Naturales Protegidas. Estudio de caso en el Parque Nacional Machalilla (Manabí, Ecuador). Revista Científica Ciencia y Tecnología Vol 23. 2022. No 37 págs. 61- 81. http://cienciaytecnologia.uteg.edu.ec/revista/index.php/cienciaytecnologia/article/view/586 (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Reyes, Javier Escalera.; Esteban Ruiz Ballesteros. Resiliencia Socioecológica: aportaciones y retos desde la Antropología. Revista de antropología social 20. 2011: 109-135. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/838/83821273005.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Hernández, R., Fernández, C., and Baptista, L. Metodología de la Investigación. Sexta edición. McGRAW-HILL / Interamericana Editores, S.A. DE C.V. 2014. https://www.esup.edu.pe/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/2.%20Hernandez,%20Fernandez%20y%20Baptista-Metodolog%C3%ADa%20Investigacion%20Cientifica%206ta%20ed.pdf.

- Hernández-Mogollón, J., Campón-Cerro, A., Leco-Berrocal, F., & Pérez-Diaz, A. Diversificación agrícola y sostenibilidad de los sistemas agrícolas: posibilidades para el desarrollo del agroturismo. Revista de Ingeniería Ambiental y Gestión, 10, 2011. 1911-1921. [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, P., Galioto, F., Chiorri, M., y Vazzana, C. An integrated sustainability index based on agro-ecological and socio-economic indicators. A case study of organic agriculture without livestock in Italy. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 42, 2018. 859 - 884. [CrossRef]

- Apaza-Panca, C., Arévalo, J., & Apaza-Apaza, S. Agroturismo: Alternativa para el desarrollo rural sostenible. Dominio de las Ciencias, 6, 2020. 207-227. [CrossRef]

- Utama, I. (2023). Revisión de Estudios Elemento Clave de la Gestión del Agroturismo. Seminario Complementario Foro Nacional Manajemen Indonesia. Vol. 1. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Vacacela, A. Factores relevantes para la gestión de pequeñas empresas agroturísticas. Polo del Conocimiento. Vol 8, No 9. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Rigby, D., Woodhouse, P., and Young, T. (). Constructing a farm level indicator of sustainable agricultural practice. Ecological Economics, 39, 2001. 463-478. [CrossRef]

- Szabó, L., Balogh, A., Huszár, P., Tóth, A. y Bánhegyi, A. The possible development of the rural - agrotourism in Hungary. Екoнoміка І Управління Бізнесoм. Тoм 11, № 4. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Evgrafova, L., Ismailova, A. y Kalinichev, V. El agroturismo como factor de desarrollo rural sostenible. Serie de conferencias IOP: Ciencias de la Tierra y del Medio Ambiente, 421. 2020. Número 2. [CrossRef]

- Landeta-Bejarano, Nathalie, Brusela Vásquez-Farfán, and Narcisa Ullauri-Donoso. Turismo sensorial y agroturismo: Un acercamiento al mundo rural y sus saberes ancestrales." Revista Investigaciones Sociales 4.11. 2018: 46-58.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).