Submitted:

14 August 2024

Posted:

15 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

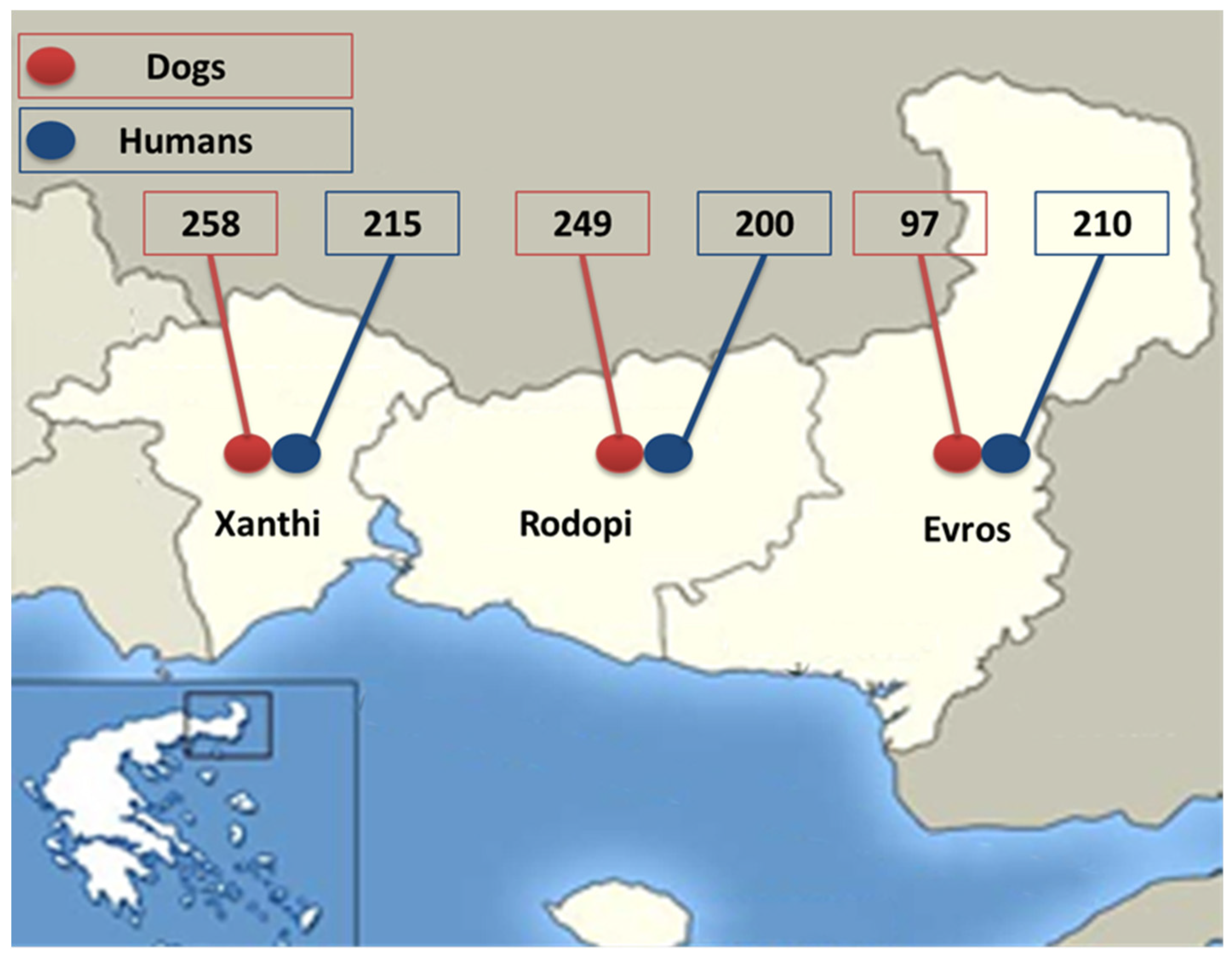

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Dog Samples

2.3. Human Samples

2.4. Sample Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Institutional Review Board Statement

3. Results

3.1. Dog Samples

3.2. Human Samples

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Simón, F.; Siles-Lucas, M.; Morchón, R.; González-Miguel, J.; Mellado, I.; Carretón, E.; Montoya-Alonso, J. A. Human and animal dirofilariasis: The emergence of a zoonotic mosaic. Clin Microbiol Rev 2012, 25, 507–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, J.W.; Genchi, C.; Kramer, L.H.; Guerrero, J.; Venco, L. Heartworm disease in animals and humans. Adv Parasitol 2008, 66, 193–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón, F.; Diosdado, A.; Siles-Lucas, M.; Kartashev, V.; González-Miguel, J. Human dirofilariosis in the 21st century: A scoping review of clinical cases reported in the literature. Transbound Emerg Dis 2022 69, 2424–2439. [CrossRef]

- Fuehrer, H.P.; Morelli, S.; Unterköfler, M.S.; Bajer, A.; Bakran-Lebl, K.; Dwużnik-Szarek, D.; et al. Dirofilaria spp. and Angiostrongylus vasorum: current risk of spreading in Central and Northern Europe. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakou, A.; Kapantaidakis, E.; Tamvakis, A.; Giannakis, V.; Strus, N. Dirofilaria infections in dogs in different areas of Greece. Parasit Vectors 2016, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakou, A.; Soubasis, N.; Chochlios, T.; Oikonomidis, I.L.; Tselekis, D.; Koutinas, C.; Karaiosif, R.; Psaralexi, E.; Tsouloufi, T.K.; Brellou, G.; Kritsepi-Konstantinou, M.; Rallis, T. Canine and feline dirofilariosis in a highly enzootic area: first report of feline dirofilariosis in Greece. Parasitol Res 2019, 118, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diakou, A. The prevalence of canine dirofilariosis in the region of Attiki. J Hel Vet Med Soc 2001, 52, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelou, A.; Gelasakis, A.I.; Verde, N.; Pantchev, N.; Schaper, R.; Chandrashekar, R.; Papadopoulos, E. Prevalence and risk factors for selected canine vector-borne diseases in Greece. Parasit Vectors, 2019; 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeonidou, I.; Sioutas, G.; Gelasakis, A.I.; Bitchava, D.; Kanaki, E.; Papadopoulos, E. Beyond borders: Dirofilaria immitis infection in dogs spreads to previously non-enzootic areas in Greece—a serological survey. Vet Sc. 2024, 11, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, W.; Newcomb, K. Prevalence of feline heartworm disease-a global review. In Proceedings of the Heartworm Symposium ‘95, American Heartworm Society. Auburn, Alabama, USA, 31 March-2nd April 1995; pp. 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Venco, L.; Genchi, M.; Genchi, C.; Gatti, D.; Kramer, L. Can heartworm prevalence in dogs be used as provisional data for assessing the prevalence of the infection in cats? Vet Parasitol 2011, 176, 300–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodis, N.; Kalouda Tsapadikou, V.; Zacharis, G.; Zacharis, N.; Potsios, Ch.; Krikoni, E.; Xaplanteri, P. Dirofilariasis and related traumas in Greek patients: Mini Review. J SurgTrauma 2021, 9, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pampiglione, S.; Canestri Trotti, G.; Rivasi, F.; Vakalis, N. Human dirofilariasis in Greece: A review of reported cases and a description of a new, subcutaneous case. An Trop Med Parasitol 1996, 90, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelli, S.; Diakou, A.; Frangipane di Regalbono, A.; Colombo, M.; Simonato, G.; Di Cesare, A.; Passarelli, A.; Pezzuto, C.; Tzitzoudi, Z.; Barlaam, A.; et al. Use of in-clinic diagnostic kits for the detection of seropositivity to Leishmania infantum and other major vector-borne pathogens in healthy dogs. Pathogens 2023, 12, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsar Sites Information Service. Available online: https://rsis.ramsar.org/ (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Eco Thraki. Available online: https://www.ecothraki.gr/ (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Boch, J.; Supperer, R. Veterinärmedizinische Parasitologie Verlag Paul Parey, Berlin, Germany. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey, L.R. Identification of canine microfilariae. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1965, 146, 1106–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Ciuca, L.; Simòn, F.; Rinaldi, L.; Kramer, L.; Genchi, M.; Cringoli, G.; Acatrinei, D.; Miron, L.; Morchon, R. Seroepidemiological survey of human exposure to Dirofilaria spp. in Romania and Moldova. Acta Trop 2018, 187, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savić, S.; Stosic, M.Z.; Marcic, D.; Hernández, I.; Potkonjak, A.; Otasevic, S.; Ruzic, M.; Morchón, R. Seroepidemiological study of canine and human dirofilariasis in the endemic region of Northern Serbia. Front Vet Sci 2020, 7, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eng, J. Sample size estimation: how many individuals should be studied? Radiol 2003, 227, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zar, J.H. Biostatistical analysis, 4th ed.; New Jersey: Prentice-Hall US. 1998. [Google Scholar]

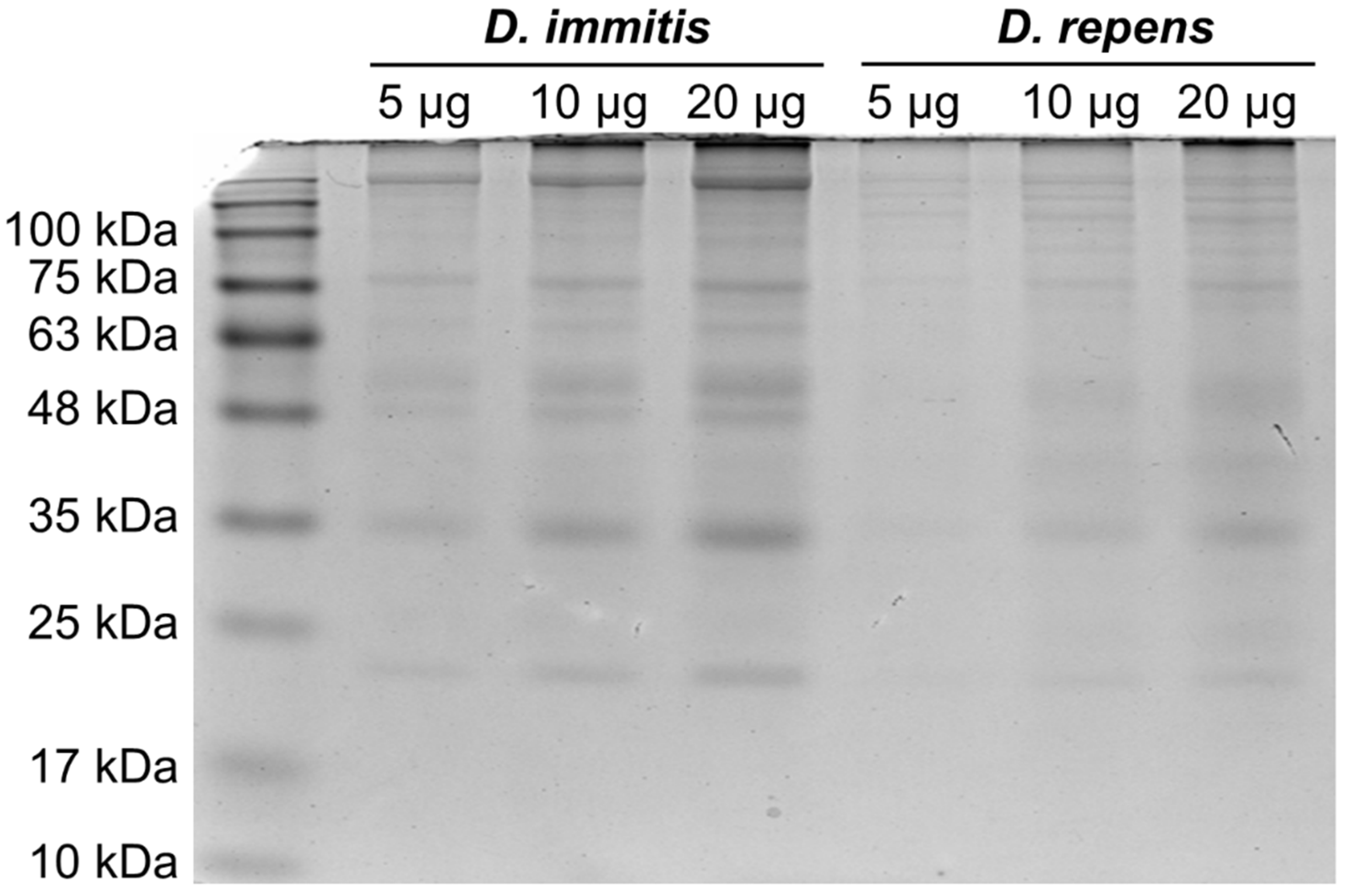

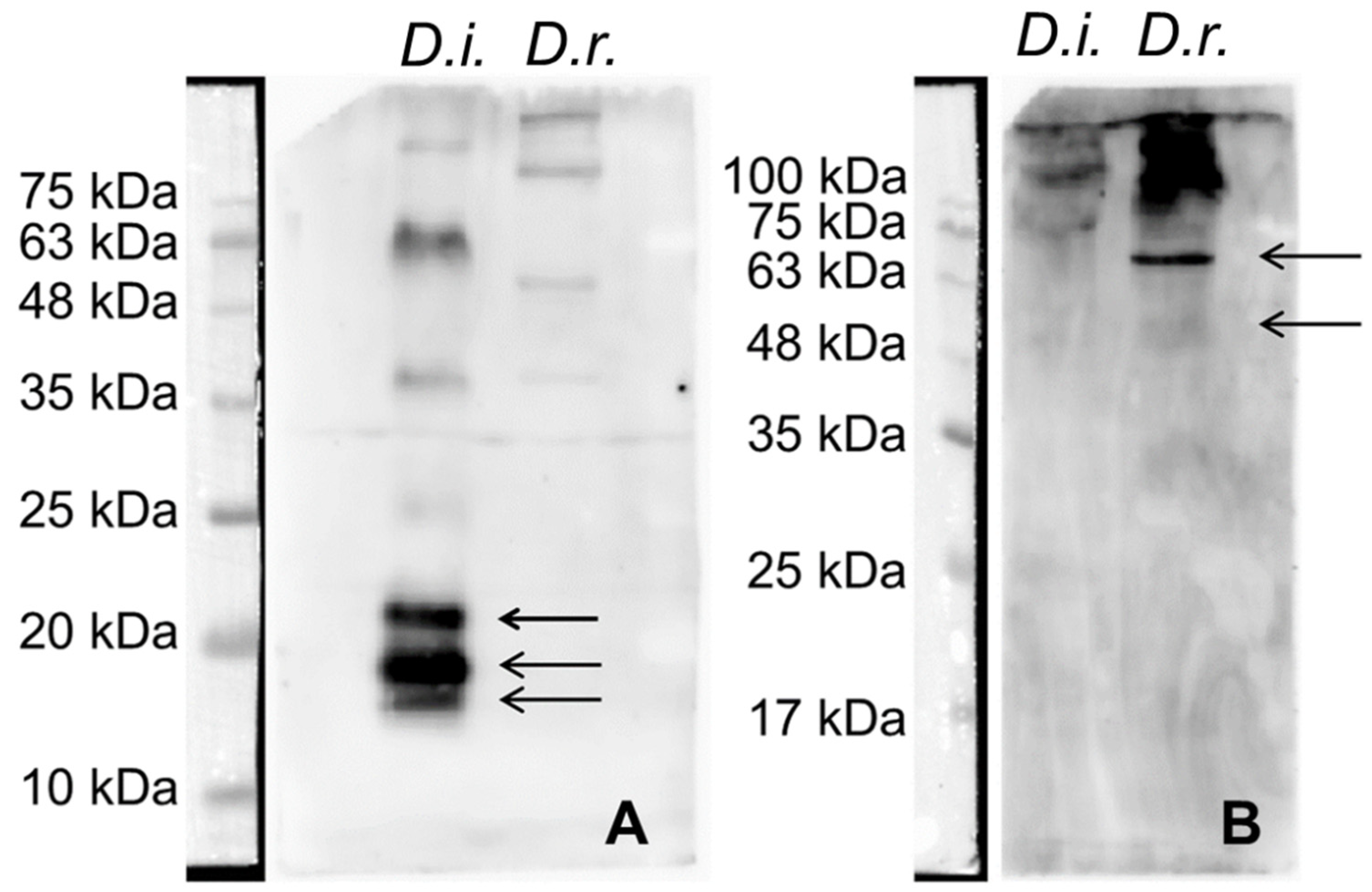

- Torres-Chable, O.M.; Brito-Argaez, L.G.; Islas-Flores, I.R.; Zaragoza-Vera, C.V.; Zaragoza-Vera, M.; Arjona-Jimenez, G.; Baak-Baak, C.M.; Cigarroa-Toledo, N.; Gonzalez-Garduño, R.; Machain-Williams, C.I.; Garcia-Rejon, J.E. Dirofilaria immitis proteins recognized by antibodies from individuals living with microfilaremic dogs. Infect Dev Ctries 2020, 14, 1442–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papazahariadou, M.G.; Koutinas, A.F.; Rallis, T.S.; Haralabidis, S.T. Prevalence of microfilaraemia in episodic weakness and clinically normal dogs belonging to hunting breeds. J Helminthol 1994, 68, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Founta, A.; Theodoridis, Y.; Frydas, S.; Chliounakis, S. The presence of filarial parasites of dogs in Serrae Province. J Hell Vet Med Soc 1999, 50, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefkaditis, M.; Koukeri, S.; Cozma, V. An endemic area of Dirofilaria immitis seropositive dogs at the eastern foothills of Mt Olympus, Northern Greece. Helminthol 2010, 47, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiou, L.V. , Kontos, V.I., Kritsepi Konstantinou, M., Polizopoulou, Z.S., Rousou, X.A., Christodoulopoulos, G. Cross-sectional serosurvey and factors associated with exposure of dogs to vector-borne pathogens in Greece. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis, 2019; 19, 923–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsochatzis, D.E. Development of analytical methods for the determination of residues of pesticides used in rice cultures: application for the assessment of their environmental implications, PhD Thesis, School of Chemical Engineering, Department of Chemistry. Thessaloniki: Aristotle University of Thessaloniki; 2012. p. 201.

- Geotechnical Chamber of Greece. Greek cattle milk production. 2011. Available online: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.geotee.gr/lnkfiles/20120101_OLH_H_MELETH_GALA_13122011.pdf (accessed on 20.07.2024).

- Mwalugelo, Y.A.; Mponzi, W.P.; Muyaga, L.L.; Mahenge, H.H.; Katusi, G.C.; Muhonja, F.; Omondi, D.; Ochieng, A.O.; Kaindoa, E.W.; Amimo, F.A. Livestock keeping, mosquitoes and community viewpoints: a mixed methods assessment of relationships between livestock management, malaria vector biting risk and community perspectives in rural Tanzania. Malar J 2024, 23, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alho, A.M.; Landum, M.; Ferreira, C.; Meireles, J.; Goncalves, L.; de Carvalho, L.M.; Belo, S. Prevalence and seasonal variations of canine dirofilariosis in Portugal. Vet Parasitol 2014, 206, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diakou, A.; Gewehr, S.; Kapantaidakis, E.; Mourelatos, S. Can mosquito population dynamics predict Dirofilaria hyperendemic foci? In Proceeding of 19th E-SOVE, Thessaloniki, Greece, 13-17 October 2014 p. 76.

- Shcherbakov, O.V.; Aghayan, S.A.; Gevorgyan, H.S.; Burlak, V.A.; Fedorova, V.S.; Artemov, G.N. An updated list of mosquito species in Armenia and Transcaucasian region responsible for Dirofilaria transmission: A review. J Vector Borne Dis 2023, 60, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fotakis, E.A.; Chaskopoulou, A.; Grigoraki, L.; Tsiamantas, A.; Kounadi, S.; Georgiou, L.; Vontas, J. Analysis of population structure and insecticide resistance in mosquitoes of the genus Culex, Anopheles and Aedes from different environments of Greece with a history of mosquito borne disease transmission. Acta Trop 2017, 174, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spanoudis, C.G.; Pappas, C.S.; Savopoulou-Soultani, M.; Andreadis, S.S. Composition, seasonal abundance, and public health importance of mosquito species in the regional unit of Thessaloniki, Northern Greece. Parasitol Res 2021, 120, 3083–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ESDA, European Society of Dirofilariosis and Angiostrongylosis. Guidelines for clinical management of canine heartworm disease. Available online: https://www.esda.vet/wp-content/up loads/2017/11/GUIDELINES-FOR-CLINICAL-MANAGEMENT-OFCANINE-HEARTWORM-DISEASE.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- AHS, American Heartworm Society. Current canine guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, and management of heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) infection in dogs. Available online: https://d3ft8sckhnqim2.cloudfront.net/images/pdf/AHS_Canine _Guidelines_11_13_20.pdf?1605556516 (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Morchón, R.; Montoya-Alonso, J.A.; Rodríguez-Escolar, I.; Carretón, E. What has happened to heartworm disease in Europe in the last 10 years? Pathogens 2022, 11, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrić, D., Bellini, R., Scholte, E. J., Rakotoarivony, L. M., & Schaffner, F. (2014). Monitoring population and environmental parameters of invasive mosquito species in Europe. Parasites & vectors, 7, 187. [CrossRef]

- Veronesi, F.; Deak, G.; Diakou, A. Wild Mesocarnivoresas reservoirs of endoparasites causing important zoonoses and emerging bridging infections cross Europe. Pathogens 2023, 12, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasić-Otasevic, S.; Golubović, M.; Trichei, S.; Zdravkovic, D.; Jordan, R.; Gabrielli, S. Microfilaremic Dirofilaria repens infection in patient from Serbia. Emerg Infect Dis 2023, 29, 2548–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pupić-Bakrač, A.; Pupić-Bakrač, J.; Beck, A.; Jurković, D.; Polkinghorne, A.; Beck, R. Dirofilaria repens microfilaremia in humans: Case description and literature review. One health 2021, 13, 100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebl, L.; Tappe, D.; Giese, M.; Mempel, S.; Tannich, E.; Kreuels, B.; Ramharter, M.; Veletzky, L.; Jochum, J. Recurrent swelling and microfilaremia caused by Dirofilaria repens infection after travel to India. Emerg Infect Dis 2021, 27(6), 1701–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, S.; Parameswaran, A.; Santosham, R.; Santosham, R. Human pulmonary dirofilariasis masquerading as a mass. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2016, 24, 722–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pampiglione, S.; Canestri Trotti, G.; Rivasi, F.; Vakalis, N. Human dirofilariasis in Greece: a review of reported cases and a description of a new, subcutaneous case. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 1996, 90, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampiglione, S.; Rivasi, F.; Gustinelli, A. Dirofilarial human cases in the Old World, attributed to Dirofilaria immitis: a critical analysis. Histopathol 2009, 54, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodis, N.; Kalouda Tsapadikou, V.; Zacharis, G.; Zacharis, N.; Potsios, Ch.; Krikoni, E.; Xaplanteri, P. Dirofilariasis and related traumas in Greek patients: Mini Review. J Surg Trauma 2021, 9, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bozidis, P.; Sakkas, H.; Pertsalis, A.; Christodoulou, A. ; Kalogeropoulo,s C.D., Papadopoulou, C. Molecular analysis of Dirofilaria repens isolates from eye-care patients in Greece. Acta Parasitol 2021, 66, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falidas, E.; Gourgiotis, S.; Ivopoulou, O.; Koutsogiannis, I.; Oikonomou, C.; Vlachos, K.; Villias, C. Human subcutaneous dirofilariasis caused by Dirofilaria immitis in a Greek adult. J Infect Public Health 2016, 9, 102–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón, F.; Prieto, G.; Morchón, R.; Bazzocchi, C.; Bandi, C.; Genchi, C. Immunoglobulin G antibodies against the endosymbionts of filarial nematodes (Wolbachia) in patients with pulmonary dirofilariasis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2003, 10, 180–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón, F.; Muro, A.; Cordero, M.; Martin, J. A seroepidemiologic survey of human dirofilariosis in Western Spain. Trop Med Parasitol 1991, 2, 106–108. [Google Scholar]

- Simón, F.; Prieto, G.; Muro, A.; Cancrini, G.; Cordero, M.; Genchi, C. Human humoral immune response to Dirofilaria species. Parassitologia 1997, 39, 397–400. [Google Scholar]

- Perera, L.; Muro, A.; Cordero, M.; Villar, E.; Simón, F. ; Evaluation of a 22 kDa Dirofilaria immitis antigen for the immunodiagnosis of human pulmonary dirofilariosis. Trop Med Parasitol 1994, 45, 249–252. [Google Scholar]

- Henke, K.; Ntovas, S.; Xourgia, E.; Exadaktylos, A.K.; Klukowska-Rötzler, J.; Ziaka, M. Who let the dogs out? unmasking the neglected: a semi-systematic review on the enduring impact of toxocariasis, a prevalent zoonotic infection. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20, 6972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera, E.D.; Carretón, E.; Morchón, R.; Falcón-Cordón, Y.; Falcón-Cordón, S.; Simón, F.; Montoya-Alonso, J.A. The Canary Islands as a model of risk of pulmonary dirofilariasis in a hyperendemic area. Parasitol Res 2018, 117, 933–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontes-Sousa, A.P.; Silvestre-Ferreira, A.C.; Carretón, E.; Esteves-Guimarães, J.; Maia-Rocha, C.; Oliveira, P.; Lobo, L.; Morchón, R.; Araújo, F.; Simón, F.; Montoya-Alonso, J.A. Exposure of humans to the zoonotic nematode Dirofilaria immitis in Northern Portugal. Epidemiol Infect 2019, 147, e282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muro, A.; Cordero, M.; Ramos, A.; Simón, F. Seasonal changes in the levels of anti-Dirofilaria immitis antibodies in an exposed human population. Trop Med Parasitol 1991, 42, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Diakou, A.; Prichard, R.K. Concern for Dirofilaria immitis and macrocyclic lactone loss of efficacy: current situation in the USA and Europe, and future scenarios. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traversa, D.; Diakou, A.; Colombo, M.; Kumar, S.; Long, T.; Chaintoutis, S.C.; Venco, L.; Betti Miller, G.; Prichard, R. First case of macrocyclic lactone-resistant Dirofilaria immitis in Europe - Cause for concern. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist. 2024, 25, 100549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartashev, V.; Afonin, A.; Gonzalez-Miguel, J.; Sepulveda, R.; Simon, L.; Morchon, R.; Simon, F. Regional warming and emerging vector borne zoonotic dirofilariosis in the Russian Federation, Ukraine, and other post-Soviet states from 1981 to 2011 and projection by 2030. BioMed Res Int 2014, 858936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Thrace (n = 604) | Xanthi (n = 258) | Rodopi (n = 249) | Evros (n = 97) | |||||

| Examination method | D. i. | D. r. | D. i. | D. r. | D. i. | D. r. | D. i. | D. r. |

| Knott | 86 (14.2%)* | 7 (1.3%)* | 45 (17.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 20 (8%) | 0 | 21 (21.6%)* | 6 (6.2%)* |

| Serology | 171 (28.3%) | - | 80 (31%) | - | 56 (22.5%) | - | 35 (36.1%) | - |

| Knott or/and Serology | 173 (28.6%)* | 7 (1,3%)* | 81 (31.4%) | 1 (0,4%) | 57 (22.9%) | 0 | 35 (36.1%)* | 6 (6.2%)* |

| Seropositive samples per parasite | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Regional unit | Dirofilaria spp. | D. immitis | D. repens |

| Thrace (n = 625) | 42 (6.7%) | 24 (3.8%) | 18 (2.9%) |

| Xanthi (n = 215) | 15 (7%) | 5 (2.3%) | 10 (4.7%) |

| Rodopi (n = 200) | 15 (7.5%) | 9 (4.5%) | 6 (3%) |

| Evros (n = 210) | 12 (5.7%) | 10 (4.7%) | 2 (1%) |

| Variable | Dirofilaria positive | Dirofilaria negative | χ2 test / Fisher test (p-value) Odds ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 70 (35.2%) | 129 (64.8%) | 5.21 (0.022) |

| Female | 90 (25.9%) | 257 (74.1%) | Odds ratio=1.55 |

| Age* | |||

| ≤ 3 | 67 (26.3%) | 188 (73.7%) | 4.92 (0.089) |

| 3−7 | 63 (29.3%) | 152 (70.7%) | |

| >7 | 30 (39.5%) | 46 (60.5%) | |

| R.U.** | |||

| Evros | 36 (37.1%) | 61 (62.9%) | 10.57 (0.005) |

| Rodopi | 56 (22.5%) | 193 (77.5%) | Odds ratio=2.03 |

| Xanthi | 68 (34.0%) | 132 (66.0%) | Odds ratio=1.15 |

| Lifestyle | |||

| Outside | 102 (37.5%) | 170 (62.5%) | 18.23 (<0.001) |

| Inside | 2 (20.0%) | 8 (80.0%) | Odds ratio=2.40 |

| In and out | 56 (21.2%) | 208 (78.8%) | Odds ratio=2.27 |

| Hair length | |||

| Short | 79 (32.5%) | 79 (32.5%) | 3.00 (0.223) |

| Medium | 57 (25.3%) | 57 (25.3%) | |

| Long | 24 (30.8%) | 24 (30.8%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).