1. Introduction

Today, social isolation is a problem for many older

adults. Social isolation can occur due to retirement or the death of a partner

or friend [

1,

2], and can sometimes lead to

cognitive decline and poor mental and physical health [

3,

4], and in severe cases, can increase the risk of

death, including suicide [

5]. One technology

that may solve these problems is information and communication technology

(ICT). Previous studies have shown that the use of ICT, such as smartphones,

has a positive effect on the cognitive function of older adults [

6] and reduces the risk of depression [

7,

8,

9]. Relatedly, smartphones have been shown to

play a beneficial role in disease management including cares of diabetes [

10] and Alzheimer's disease [

11]. Furthermore, incorporating smartphone use into

the lives of older adults may facilitate activities such as internet-based

banking [

12] and shopping [

13], enriching the daily lives of older adults with

mobility issues. In this review, we review recent intervention studies aimed at

popularizing smartphone use among older adults, point out the limitations of

these studies, and propose new intervention studies.

2. Factors That Hinder or Promote Smartphone Use among the Elderly

Despite these benefits, it is not easy to spread

ICT to the elderly. According to the "2022 Communication Usage Trend

Survey" by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications in Japan [

14], the smartphone ownership rate in Japan is

77.3%, while it is low at 27.3% for those aged 80 and over. In addition, even

if some elderly people have smartphones, they mainly use them for phone and

email functions and do not utilize other functions. In the "Public Opinion

Survey on the Use of Information and Communication Devices in 2020" by the

Cabinet Office in Japan [

15], the reasons why

elderly people aged 70 and over do not use smartphones included "I don't

think it's necessary for my life," "I don't know how to use it,"

and "I think I can leave it to my family if necessary." On the other

hand, the number of situations in which smartphones are necessary has increased

significantly compared to before, and is expected to increase further in the

future. In addition, as shown in the 2023 White Paper on the Aging Society [

16], more than half of elderly households are

single-person or couple-only, and it is assumed that many elderly people do not

have children or grandchildren nearby to ask them how to use smartphones.

The most common argument for why elderly people

avoid ICT is related to their physical decline. Age-related physical changes

make it difficult to understand and use technology [

17].

For example, cognitive decline is associated with poorer performance in daily

activities and may negatively affect the acceptance of new technologies by

elderly people [

18,

19]. In addition,

depression, which is common among elderly people, may increase negative

emotions and inhibit adaptation to new technologies [

20].

When these conditions are combined, elderly people are unable to use ICT well,

feel embarrassed about it, experience lower confidence, and increase anxiety,

which may lead to them avoiding ICT even more [

21].

Results from a recent cross-sectional study also show low ICT use, especially

among older adults with multimorbidity [

22].

However, physical decline due to aging is not the

only barrier to ICT use among older adults. Rather, previous studies have

argued that the main factors that negatively affect ICT use are lack of

self-efficacy and social capital [

23,

24]. For

older adults, those with existing social support are more likely to receive

assistance with ICT maintenance and troubleshooting, and therefore tend to use

ICT more [

23,

25,

26]. ICT helps older adults

maintain connections with family, friends, former colleagues, acquaintances,

and new contacts with common interests and needs [

27].

ICT also allows older adults to find new hobbies, improve their abilities, and

participate in enjoyable activities without time constraints. In addition,

advising others with acquired knowledge has a significant positive impact on

older adults' self-confidence. The gained confidence translates into

self-efficacy, which encourages further ICT use [

27].

3. Healthy Aging and ICT

However, it is not enough to simply increase the

Internet use of older adults. When older adults feel that the end of their life

is approaching, they try to actively engage in relationships that they perceive

as meaningful in their lives [

28]. Therefore,

excessive or compulsive ICT use can lead to a decrease in well-being [

29]. In addition, ICT use is potentially addictive,

which may weaken social connections in daily life and reduce social and

psychological well-being [

30]. Furthermore,

passive ICT use may lead to feelings of inferiority and jealousy, which may

reduce well-being [

31]. Previous studies have

shown that the main reasons why older adults drop out of the Internet are a

lack of meaningful content, nothing worth reading or watching, and a lack of

time to use it [

32]. Fears of privacy

violations and reduced security, for example, worries about internet fraud and

technology malfunctions, are also major reasons why older people avoid ICT [

33,

34]. Therefore, it is necessary to give older

people what they want and encourage them to learn it, rather than forcing them

to use ICT that they do not need.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has proposed

healthy aging as an important concept that aims to create an environment and

opportunities to maintain a functional state and ultimately achieve universal

well-being [

35]. Healthy aging refers to the

process of developing and maintaining "functional capabilities" to

enable well-being in older people. According to WHO, functional capabilities

are a concept that includes various capabilities necessary for an individual to

engage in valued and meaningful activities, and are composed of internal

capabilities, which are a composite of physical and mental capabilities,

environmental factors, and the interaction between these two elements [

35]. The WHO suggests that countries monitor

functional capacity, internal capacity, and environmental factors as indicators

of the progress of healthy aging [

36].

It is possible to promote the healthy aging by

making good use of ICT. For example, health is a major concern for older

people, so promoting digital health technologies is an effective way to

popularize ICT to older people [

37]. However,

considering the above discussion that it is not only physical and mental health

that inhibits ICT use among older people, promoting healthy aging does not

necessarily promote the spread of ICT. If what many older people want from ICT

is health, then one effective way to popularize ICT to them is to use health as

an opportunity, but conversely, it is not surprising that healthier older

people do not need health information as much and therefore do not become more

interested in ICT. Consistent with this speculation, previous research has

shown that older adults with better self-care have lower preference attitudes

toward smart health services [

38]. However, if

the aim is to popularize ICT through the circulation of self-efficacy and

social capital, it is significant to have healthy older people enter the ICT

circulation.

4. Review of Previous Intervention Studies and Future Study Perspectives

Compared to the studies highlighting the benefits

of ICT, there is less evidence that ICT training improves ICT proficiency among

older adults. However, there is evidence that group-based ICT training is

effective in promoting skills and digital literacy [

39,

40,

41].

In one study by Zhao et al. [

41], 344 older

participants were assigned to either an intervention group or a wait-list

control group in a randomized controlled trial. The authors believe that

previous studies had high dropout rates because the training was not systematic

and therefore participants did not feel the benefits. Therefore, this

intervention study was the first to help participants acquire smartphone

functions under a systematic program. The intervention group, who received a

smartphone training program once a week for 20 weeks, was shown to improve

smartphone competency and quality of life. However, even if the training in

these studies was effective for some older adults, it is unlikely that it was

as effective for many other older adults. This is because, as mentioned above,

older adults have individual differences in what they want from ICT, and a

uniform approach that ignores their autonomy and preferences would discourage

them. This is also reflected in the low effect sizes of some indicators shown

in this study.

Therefore, recent studies have argued for a move

away from a one-size-fits-all approach to individualized approaches to

education and learning [

42,

43,

44]. In one of

these studies, a qualitative study conducted by Betts et al. [

42] with 17 older adults revealed that older adults

are interested in acquiring more skills and, at the same time, want to acquire

knowledge through personalized, one-on-one learning sessions. Arthanat et al. [

43] conducted a two-year randomized controlled

trial in which 83 older adults were divided into an intervention group and a

control group, followed by one-on-one ICT training between coaches and

participants at six-month intervals to promote access to and use of digital

resources. As a result, older adults in the intervention group were more

engaged in various leisure, health management, and daily activities than older

adults in the control group. They also showed a significant increase in

technology acceptance and maintained a sense of independence. Meanwhile, in a

study of older adults living alone by Fields et al. [

44],

83 participants were randomly assigned to an intervention group or a waiting

list group, with the intervention group provided with tablets, broadband, and

one-on-one training. Volunteer coaches provided iPad lessons in participants'

homes for a total of eight sessions each week, and assessed self-reported

loneliness, social support, technology use, and confidence at baseline and

follow-up. As a result, while there was no change in loneliness in the

intervention group, there was a slight significant improvement in social

support and confidence in technology, and a significant increase in technology

use. Furthermore, in interviews, many participants stated that their confidence

in technology had increased. These results indicate that one-on-one, careful instruction

over time is more effective than uniform instruction.

Considering these trends, future intervention

studies on ICT training should not be uniform, such as gathering participants

in a large classroom and conducting lectures, but should be individualized with

one-on-one instruction according to the participants' needs if researchers want

maximum results from an intervention. However, if social implementation is

taken into consideration, it must naturally be feasible in terms of

cost-effectiveness or time-of-day effectiveness. If training is designed to be

too costly and time-consuming to meet individual needs, it will be that much

more difficult to continue the business. It seems that existing research has

not seriously addressed this issue. It is necessary to be able to perform

adequately in terms of cost and time while taking advantage of the benefits of

individual education. Therefore, we propose incorporating into the research

model the improvement in self-efficacy and knowledge about ICT functions that

comes from advising others on acquired knowledge, as confirmed in the review

paper by Chen and Schlz [

27].

Self-determination theory asserts that

self-efficacy is a determining factor for intrinsically motivating people [

45]. In addition, previous cross-sectional analyses

have shown that intrinsic motivation may affect ICT use and life satisfaction

among older adults [

46,

47]. Among these, Wang

et al. [

46] analyzed the influencing factors

of technology adoption using questionnaire response data administered to 286

participants aged 46 years or older, and found that physiological limitations

and anxiety of aging had a significantly negative effect, while knowledge,

intrinsic motivation, and usage expectancy had a significant positive effect on

behavioral intention. On the other hand, many studies have confirmed that

helping others increases self-efficacy. For example, Barlow & Hainsworth [

48] conducted semi-structured telephone interviews

at two time points, before and after training, to explore the motivations of 22

older volunteers when they undertook training to become lay leaders in an

arthritis self-management program. The results revealed that volunteering was

motivated by three primary needs: to fill the void in life left by retirement,

to feel useful members of society by helping others, and to find a peer group.

The results suggest that volunteering among older adults helps to offset the

losses associated with retirement and declining health.

Cognitive scientists offer a different explanation

for the learning effect of teaching: they argue that learning is enhanced when

people are placed in a situation where they must understand information and

make it understandable to others [

49,

50]. For

example, in an experiment by Nestojko et al. [

49],

56 university students were randomly divided into two groups and asked to read

and memorize a text about a war. Prior to the experiment, the two groups were

instructed to either study as if they had a test coming up (Group 1) or study

as if they were going to teach other students (Group 2). As a result of the

experiment, Group 2 was able to recall the content more accurately than Group

1. The authors of the paper argue that the difference in results may be because

people naturally try to summarize the main points of things when they think

they must teach others. Similar results were obtained in a study by Koh et al. [

50] involving 124 university student participants,

with the authors arguing that recalling previously memorized information in a

form that others can understand may help strengthen memories.

There is already a substantial body of research

showing the effects of the spread of ICT. However, there is still insufficient

research on how to popularize ICT among the elderly. Considering the existence

of publication bias, which means that experiments that produce significant

results are more likely to be published as papers, it can be assumed that it

will be more difficult to change the elderly's attitude toward ICT and

popularize it. This suggests the limitations of the method used in previous research,

in which a coach teaches a student unilaterally (even if it is one-on-one

instruction). Therefore, the author recommend that future research verify the

hypothesis that the experience of teaching other participants the smartphone

functions they have acquired will increase their interest and knowledge in

smartphones, and as a result, their own proficiency will also improve.

5. A Proposal for New Intervention Study Design

For example, we will design the study as follows.

The study will be a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Assuming that two

measurements will be taken in total for the intervention and control groups,

the effect size (partial eta squared value) will be a moderate 0.06, and the

significance level will be 5% with a power of 80%. The sample size required to

test interactions using repeated measures ANOVA will be calculated as 68 people

(34 people in each group) using G*Power 3.1.9.7. Considering the possibility of

dropouts, 80 people (40 people in each group) will be planned as study

subjects. Participants must be healthy men and women aged 65 or older who have

never used a smartphone or have only used the calling function. First, both the

intervention and control groups will gather at a designated venue and answer a

common questionnaire asking about smartphone knowledge, usage, and well-being

defined as physical and mental health. The questionnaire will be created with

reference to the indicators of Zhao et al. [

41], Arthanat et al. [

43], and Fields et al. [

44].

After that, both the intervention and control groups will undergo training

aimed at acquiring various smartphone functions (communication with family,

health management, household finances, schedule management, online seminars,

entertainment, flashlight function, emergency call function, etc.). The

instructors will be professional instructors who are familiar with smartphone

functions. In this case, participants will be asked in advance about their

preferences and will be taught in order of their interest in the functions they

are most interested in. This measure is based on the findings of previous

research that older people are less interested in ICT functions [

32] and the intrinsic motivation theory that says

that the more you are interested in something, the higher your mastery will be [

45]. In addition, participants in the intervention

group will continue to take the course from the second time onwards and will

also serve as coaches for participants in the control group. Specifically, they

will train other participants as primary coaches under the supervision of a

professional instructor. The intervention group coach will also answer

questions from participants in the control group. During this time, the

professional coach does not interfere, but instead provide feedback to both the

intervention and control group participants after the primary coaching was

completed, such as making up for shortcomings. This is to prevent the primary

coach from losing motivation to learn other smartphone functions by instilling

a sense of shame in them for not being able to coach well. Both the

intervention and control groups are allowed to use smartphones freely after the

training, and every three months (i.e. 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after the

training), they gather at a designated venue to answer the same questionnaire

and receive training. It is expected that the act of teaching other

participants increases self-efficacy for participants in the intervention group

compared to participants in the control group, and they become proficient more

quickly.

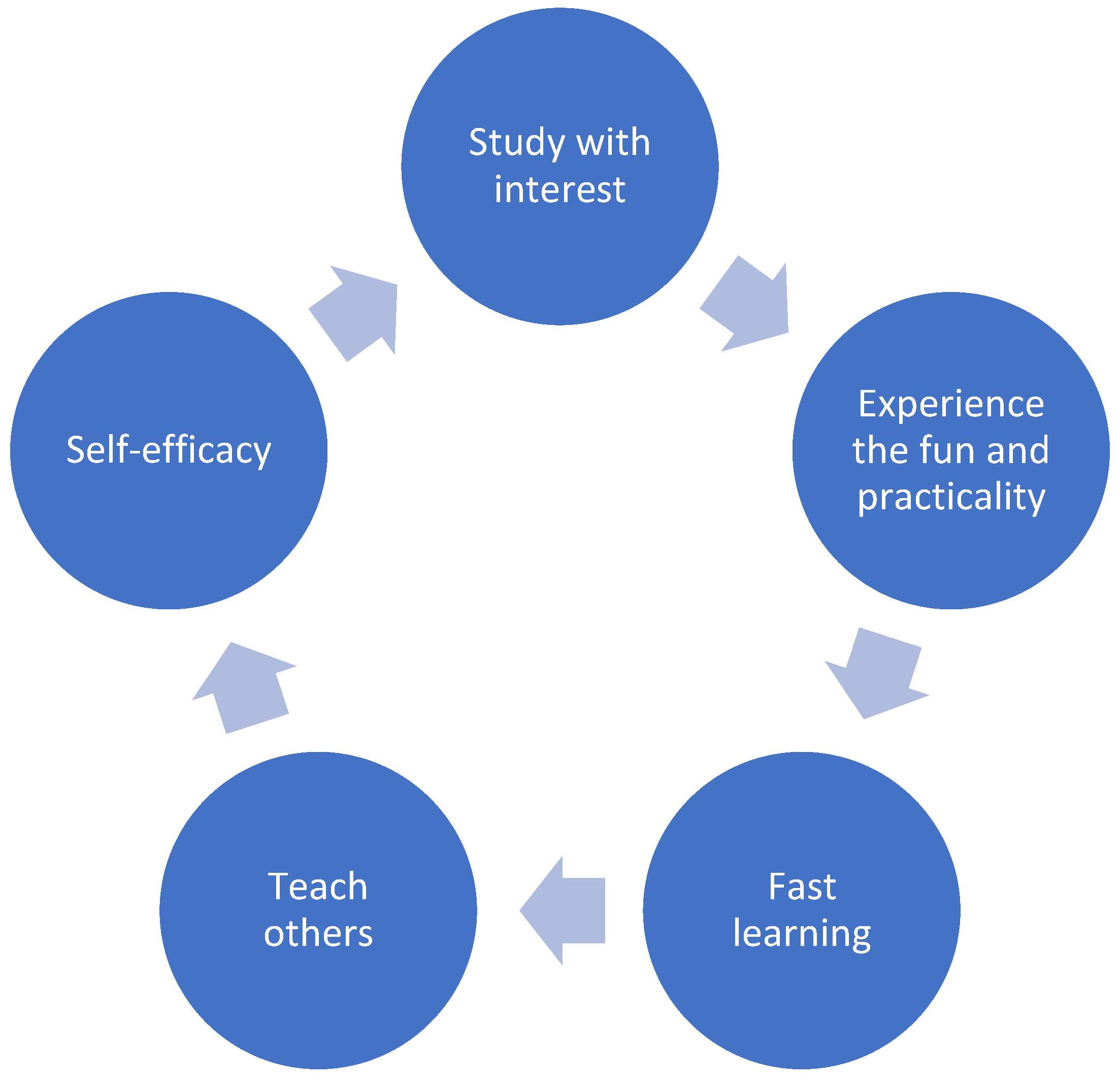

The advantage of this method is that the participants themselves can take on some of the role of coach, saving on the costs and time required for one-on-one instruction. If it is proven that the act of teaching elderly people creates a spiral of mutual help among elderly people through increased self-efficacy, it will become easier for organizations that have been hesitant to enter the market in the past because it was not cost-benefit-based to do so, and it will likely become easier to provide ICT education to the elderly. See

Table 1 and

Figure 1.

6. Discussion

In this paper, we reviewed the advantages and disadvantages of ICT adoption by the elderly, the promoting and inhibiting factors in ICT adoption, and recent intervention studies, and made suggestions for future intervention studies. While research on ICT use by the elderly is accumulating, there are few studies that clarify how to encourage ICT use by the elderly, and the effectiveness has not been fully verified. Previous research suggests that one-on-one instruction is more effective than a uniform method, but at the same time, it also suggests that there are limitations to the effectiveness if participants simply passively receive training. In this study, we discussed the possibility that elderly people can become more effectively familiar with smartphone functions by increasing their self-efficacy through the act of learning smartphone functions and teaching them to other participants in an environment where they can obtain rich social capital, such as one-on-one instruction, and proposed future research.

Of course, there are several other barriers that must be overcome to implement this in society. The positive spiral of elderly people teaching each other, as proposed in this study, is not only more effective but also less costly than traditional one-on-one instruction. However, even so, the role that ordinary elderly people can play is only a supporting role, and it is unlikely that personnel who can provide one-on-one guidance in a more specialized position will be completely unnecessary. In addition, in situations where elderly people teach each other, a person in charge is needed to guarantee their identity and accept complaints so that they do not become anxious. Issues that need to be considered include who should take on such roles and who should provide resources such as operating capital, equipment, and personnel. Currently, governments and non-profit organizations (NPOs) introduce and match senior volunteers, either paid or unpaid, but they only play a passive role of introducing elderly people who are willing to volunteer to those who need them, and there is no training with an awareness of the positive spiral proposed in this study. Despite this, the number of people who want to provide volunteer work is small compared to the number of people who want to receive volunteer work, and as a result, NPO management is not only unable to match them well, but is also forced to sacrifice budgets for other projects to cover operating costs (from an interview survey conducted by the author at a certain NPO). Despite these limitations, demonstrating that a positive spiral consisting of social capital and self-efficacy promotes the mastery of ICT functions among the elderly should be of great significance as a first step toward social implementation.

7. Conclusions

In this review, we considered the advantages and disadvantages of promoting smartphones to the elderly, and looked back at recent intervention studies to confirm that individualized instruction is more effective in helping elderly people acquire skills than uniform education, and that the challenges of the former are cost and time, but previous research has not seriously addressed this issue. Therefore, this review proposed future research to clarify how to promote the widespread use of smartphones effectively, and at low cost by involving elderly people in teaching other elderly people, creating a positive spiral that combines self-efficacy and social capital among the elderly.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. We used anonymous information that is open to the public.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. We used anonymous information that is open to the public.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study (available upon request).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Savikko, N.; Routasalo, P.; Tilvis, R.S.; Strandberg, T.E.; Pitkälä, K.H. Predictors and subjective causes of loneliness in an aged population. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2005, 41(3), 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freak-Poli, R.; Kung, C.S.; Ryan, J.; Shields, M.A. Social isolation, social support, and loneliness profiles before and after spousal death and the buffering role of financial resources. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2022, 77(5), 956–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacioppo, J. T.; Cacioppo, S. Social relationships and health: The toxic effects of perceived social isolation. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 2014, 8, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, B.; Steptoe, A.; Chen, Y.; Jia, X. Social isolation, rather than loneliness, is associated with cognitive decline in older adults: the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51(14), 2414–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J. The major health implications of social connection. Curr. Dir. Psychol. 2021, 30(3), 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamin, S.T.; Lang, F.R. Internet use and cognitive functioning in late adulthood: Longitudinal findings from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2020, 75(3), 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, A.; Osma, J. Using information and communication technologies (ICT) for mental health prevention and treatment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18(2), 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, H.Y.; Won, C.R.; Barr, T.; Merighi, J.R. Older adults’ technology use and its association with health and depressive symptoms: Findings from the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study. Nurs. Outlook 2020, 68(5), 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.A.; Ferraro, K.F.; Kim, G. Digital technology use and depressive symptoms among older adults in Korea: beneficial for those who have fewer social interactions? Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25(10), 1839–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonoto, B.C.; de Araújo, V.E.; Godói, I.P.; de Lemos, L.L.P.; Godman, B.; Bennie, M.; Diniz, L.M.; Junior, A.A.G. Efficacy of mobile apps to support the care of patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017, 5(3), e6309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Wiese, L.A.K.; Holt, J. Online chair Yoga and digital learning for rural underserved older adults at risk for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Clin. Gerontol. 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peral-Peral, B.; Villarejo-Ramos, Á.F.; Arenas-Gaitán, J. Self-efficacy and anxiety as determinants of older adults’ use of Internet Banking Services. Univers Access Inf Soc. 2020, 19(4), 825–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, P.Y.; Heng, H.B.; Selvachandran, G.; Anh, L.Q.; Chau, H.T.M.; Son, L.H.; Abdel-Baset, M.; Manogaran, G.; Varatharajan, R. Perception, acceptance and willingness of older adults in Malaysia towards online shopping: a study using the UTAUT and IRT models. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications in Japan. Survey on Trends in Telecommunications Usage in 2022, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications: Tokyo, Japan, 2023.

- Cabinet Office in Japan. Public Opinion Survey on the Use of Information and Communications Devices in 2020, Cabinet Office: Tokyo, Japan, 2021.

- Cabinet Office in Japan. 2023 White Paper on Aging Society, Cabinet Office: Tokyo, Japan, 2024.

- Campbell, R.J.; Nolfi, D.A. Teaching elderly adults to use the Internet to access health care information: before-after study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2005, 7(2), e128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, M.H.; Kim, S.; Lee, E. Understanding the factors affecting online elderly user’s participation in video UCC services. Comput. Human Behav. 2009, 25(3), 619–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitzner, T.L.; Savla, J.; Boot, W.R.; Sharit, J.; Charness, N.; Czaja, S.J.; Rogers, W.A. Technology adoption by older adults: findings from the PRISM trial. Gerontol. 2019, 59, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotten, S.R.; Ford, G.; Ford, S.; Hale, T.M. Internet use and depression among older adults. Comput Human Behav. 2012, 28(2), 496–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, E.J. Maximizing computer use among the elderly in rural senior centers. Educ. Gerontol. 2004, 30(7), 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotteler, M.L.; Kocar, T.D.; Dallmeier, D.; Kohn, B.; Mayer, S.; Waibel, A.K.; Swoboda, W.; Denkinger, M. Use and benefit of information, communication, and assistive technology among community-dwelling older adults–a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2023, 23(1), 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.Y.S.; Shillair, R.; Cotten, S.R.; Winstead, V.; Yost, E. Getting grandma online: are tablets the answer for increasing digital inclusion for older adults in the US? Educ. Gerontol. 2015, 41(10), 695–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, R.; Tentori, M.; Favela, J. Enriching in-person encounters through social media: A study on family connectedness for the elderly. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2013, 71(9), 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eronen, J.; Portegijs, E.; Rantanen, T. Health-related resources and social support as enablers of digital device use among older Finns. J. Public Health. 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friemel, T.N. The digital divide has grown old: Determinants of a digital divide among seniors. New Media Soc. 2016, 18(2), 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.R.R.; Schulz, P.J. The effect of information communication technology interventions on reducing social isolation in the elderly: a systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18(1), e4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carstensen, L.L.; Isaacowitz, D.M.; Charles, S.T. Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54(3), 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muusses, L.D.; Finkenauer, C.; Kerkhof, P.; Billedo, C.J. A longitudinal study of the association between compulsive internet use and wellbeing. Comput. Human Behav. 2014, 36, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marttila, E.; Koivula, A.; Räsänen, P. Does excessive social media use decrease subjective well-being? A longitudinal analysis of the relationship between problematic use, loneliness and life satisfaction. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 59, 101556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Wu, Y.C.; Su, C.H.; Lin, P.C.; Ko, C.H.; Yen, J.Y. Association between Internet gaming disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. J. Behav. Addict. 2017, 6(4), 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.J.; Liu, C.W. Understanding older adult's technology adoption and withdrawal for elderly care and education: mixed method analysis from national survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19(11), e374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, M.T. Obstacles to social networking website use among older adults. Comput Human Behav. 2013, 29(3), 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Coughlin, J.F. PERSPECTIVE: Older adults' adoption of technology: an integrated approach to identifying determinants and barriers. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2015, 32(5), 747–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health. Geneva: WHO Press, 2015. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565042 (accessed: 14 August 2024).

- World Health Organization. (2020). Decade of Healthy Ageing: Baseline Report. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. Retrieved from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/338677/9789240017900-eng.pdf (accessed: 14 August 2024).

- Sun, X.; Yan, W.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Huang, S.; Li, L. Internet use and need for digital health technology among the elderly: a cross-sectional survey in China. BMC public health 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rama Murthy, S.; Mani, M. Discerning rejection of technology. Sage Open 2013, 3(2), 2158244013485248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bert, F.; Giacometti, M.; Gualano, M.R.; Siliquini, R. Smartphones and health promotion: a review of the evidence. J. Med. Syst. 2014, 38, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, S.J.; Jessel, S.; Richardson, J.E.; Reid, M.C. Older adults are mobile too! Identifying the barriers and facilitators to older adults’ use of mHealth for pain management. BMC geriatrics 2013, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, L.; Ge, C.; Zhen, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y. Smartphone application training program improves smartphone usage competency and quality of life among the elderly in an elder university in China: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2020, 133, 104010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betts, L.R.; Hill, R.; Gardner, S.E. “There’s not enough knowledge out there”: Examining older adults’ perceptions of digital technology use and digital inclusion classes. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2019, 38(8), 1147–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthanat, S. Promoting information communication technology adoption and acceptance for aging-in-place: a randomized controlled trial. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2021, 40(5), 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fields, J.; Cemballi, A.G.; Michalec, C.; Uchida, D.; Griffiths, K.; Cardes, H.; Cuellar, J.; Chodos, A.H.; Lyles, C.R. In-home technology training among socially isolated older adults: findings from the tech allies program. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2021, 40(5), 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25(1), 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.H.; Chen, G.; Chen, H.G. A model of technology adoption by older adults. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2017, 45(4), 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Guo, X.; Vogel, D. Information and communication technology use for life satisfaction among the elderly: a motivation perspective. Am. J. Health Behav. 2021, 45(4), 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlow, J.; Hainsworth, J. Volunteerism among older people with arthritis. Ageing Soc. 2001, 21(2), 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestojko, J.F.; Bui, D.C.; Kornell, N.; Bjork, E.L. Expecting to teach enhances learning and organization of knowledge in free recall of text passages. Mem. Cogn. 2014, 42(7), 1038–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.W.L.; Lee, S.C.; Lim, S.W.H. The learning benefits of teaching: A retrieval practice hypothesis. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2018, 32(3), 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).