Submitted:

14 August 2024

Posted:

16 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Zebrafish Husbandry

2.2. Vibrio cholerae Infection

2.3. Behavioral Assays

2.4. Light/Dark Trial

2.5. Single-Tap Trial

2.6. Zebrafish Euthanization and Homogenization

2.7. DNA Isolation and Sequencing

3. Results

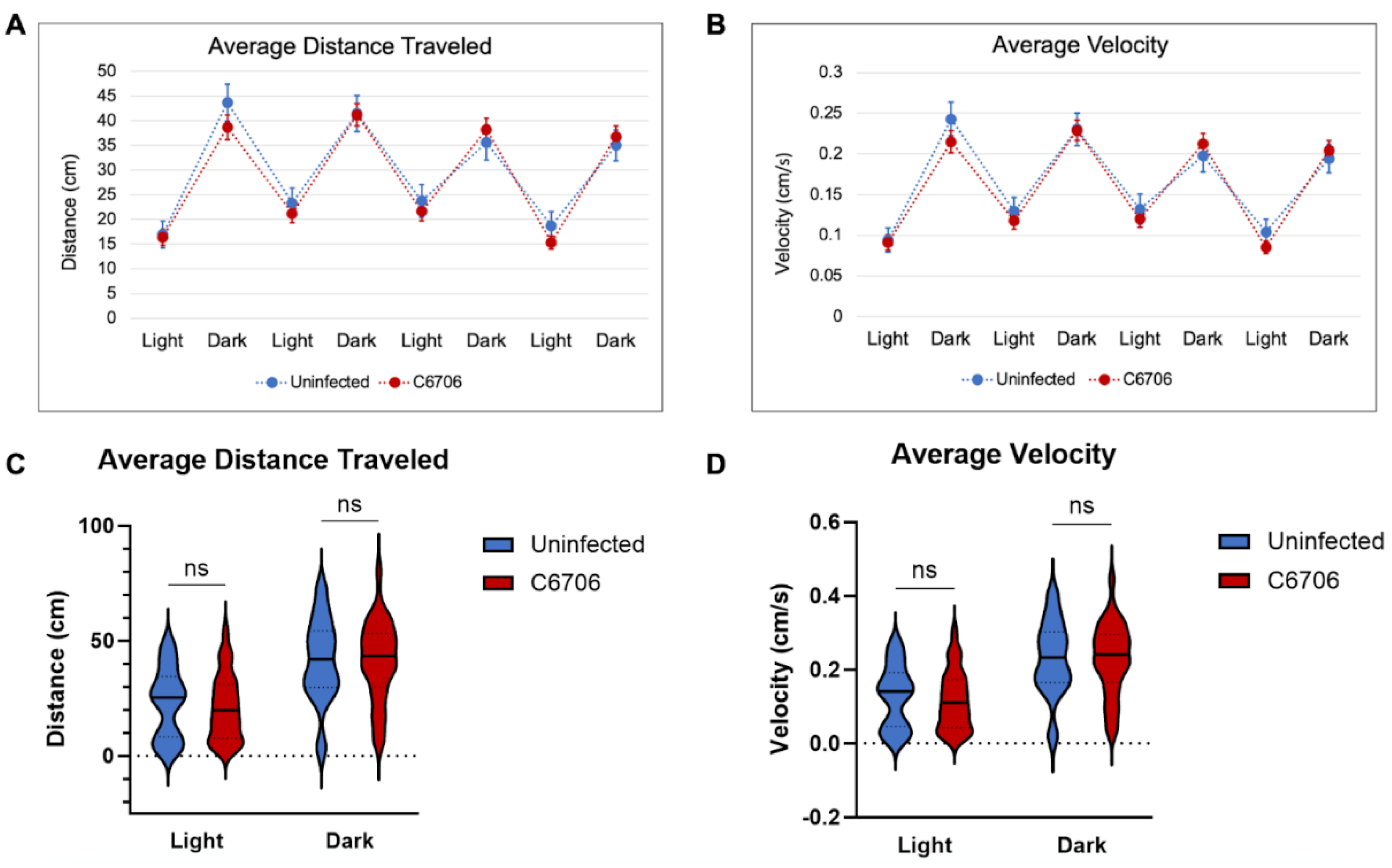

3.1. Light/Dark Trials

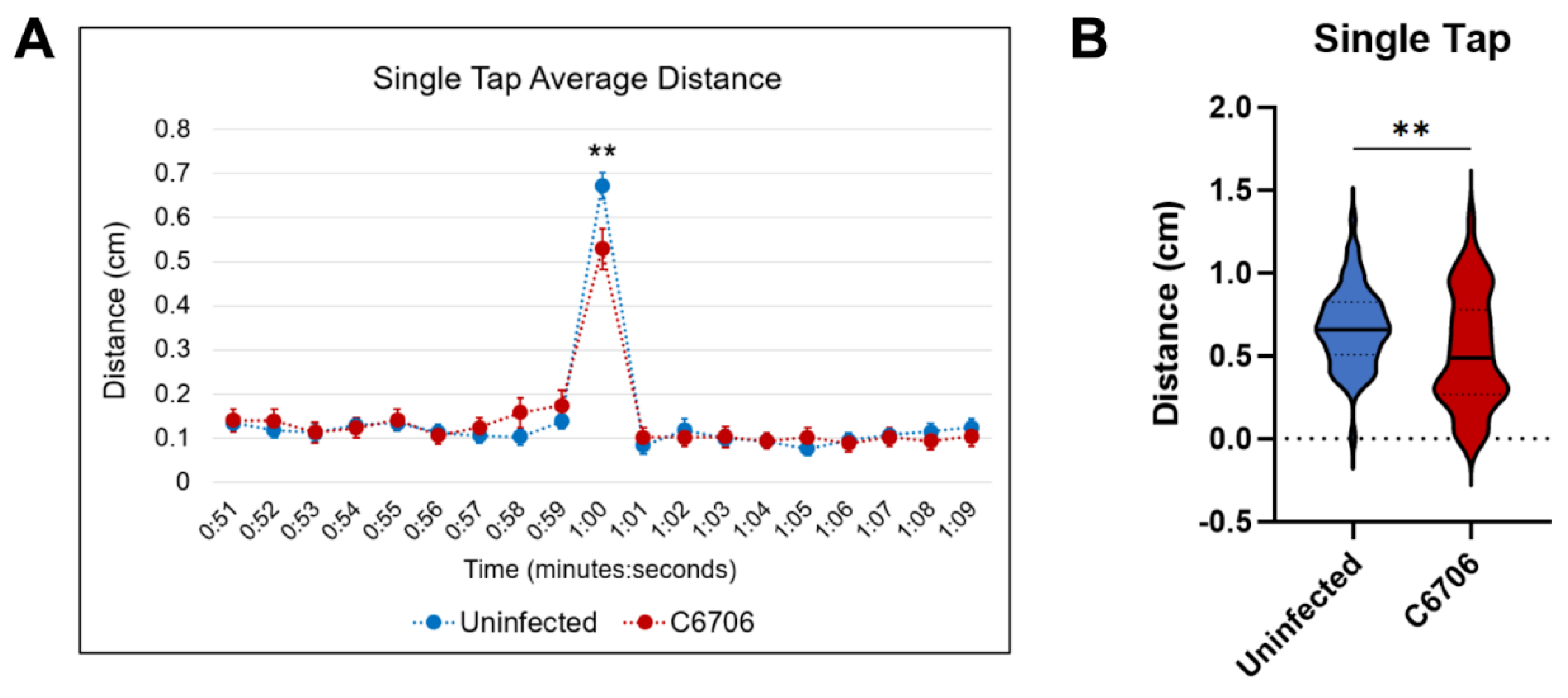

3.2. Single-Tap Trials

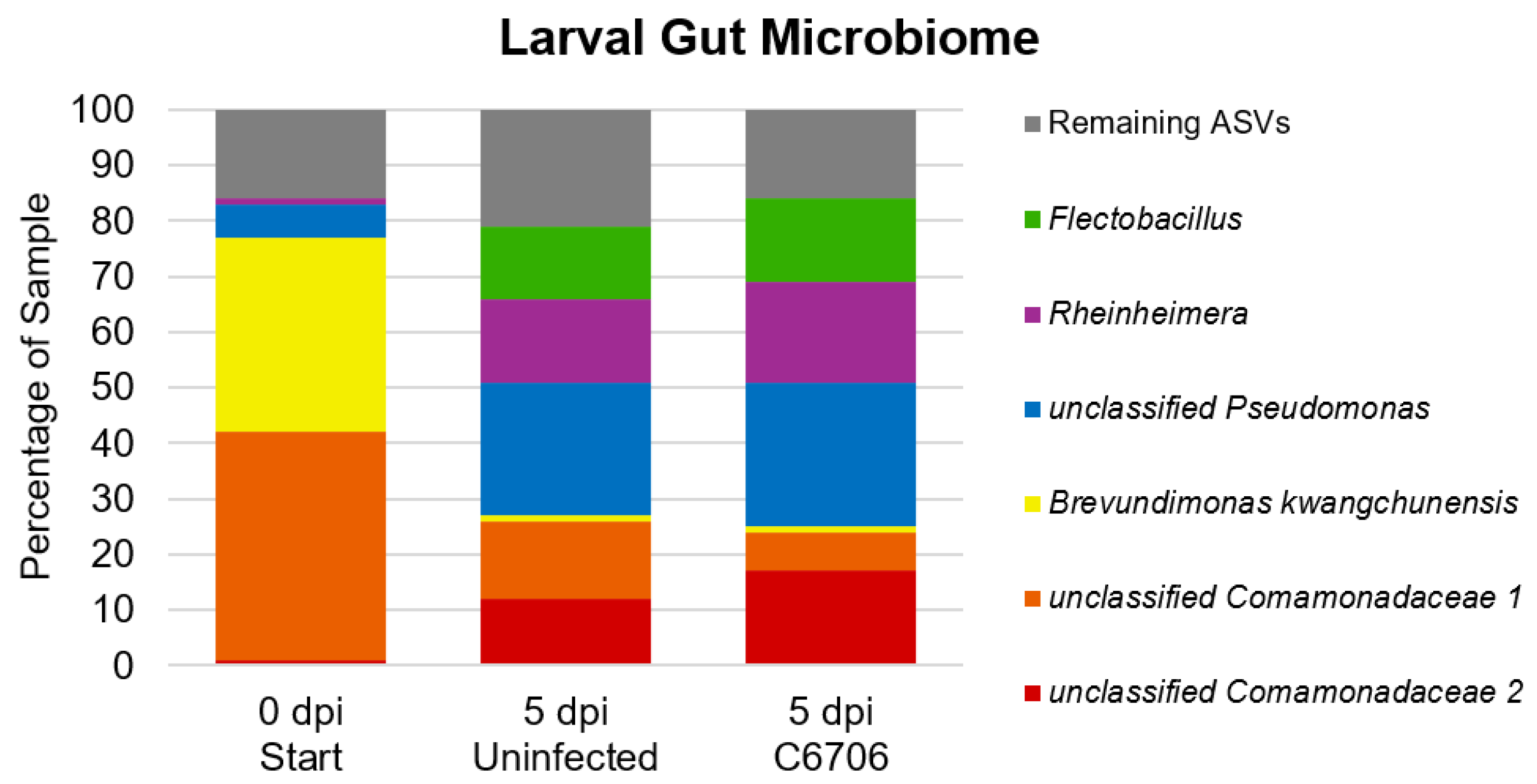

3.3. Larval Gut Microbiome

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaper, J.B., J.G. Morris, Jr., and M.M. Levine, Cholera. Clin Microbiol Rev, 1995. 8(1): p. 48-86.

- Sack, D.A., et al., Cholera. The Lancet, 2004. 363(9404): p. 223-233.

- WHO. Number of reported cholera cases. 2017 September 18, 2017 [cited 2020 December 1]; Available from: https://www.who.int/gho/epidemic_diseases/cholera/cases_text/en/.

- Organization, W.H., Cholera Annual Report 2020 Weekly Epidemiological Record 37. 2021. 96: p. 445-460.

- Organization, W.H., Cholera – Global situation. 2023. Disease Outbreak News.

- Vezzulli, L.; Grande, C.; Reid, P.C.; Hélaouët, P.; Edwards, M.; Höfle, M.G.; Brettar, I.; Colwell, R.R.; Pruzzo, C. Climate influence on Vibrio and associated human diseases during the past half-century in the coastal North Atlantic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, E5062–E5071. [CrossRef]

- Sack, D.A., et al., Cholera. Lancet, 2004. 363(9404): p. 223-33.

- Kirn, T.J.; Taylor, R.K. TcpF Is a Soluble Colonization Factor and Protective Antigen Secreted by El Tor and Classical O1 and O139 Vibrio cholerae Serogroups. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 4461–4470. [CrossRef]

- Faruque, S.M., M.J. Albert, and J.J. Mekalanos, Epidemiology, genetics, and ecology of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev, 1998. 62(4): p. 1301-14.

- A Herrington, D.; Hall, R.H.; Losonsky, G.; Mekalanos, J.J.; Taylor, R.K.; Levine, M.M. Toxin, toxin-coregulated pili, and the toxR regulon are essential for Vibrio cholerae pathogenesis in humans.. J. Exp. Med. 1988, 168, 1487–1492. [CrossRef]

- Thelin, K.H.; Taylor, R.K. Toxin-coregulated pilus, but not mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin, is required for colonization by Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor biotype and O139 strains. Infect. Immun. 1996, 64, 2853–2856. [CrossRef]

- Torgersen, M.L.; Skretting, G.; van Deurs, B.; Sandvig, K. Internalization of cholera toxin by different endocytic mechanisms. J. Cell Sci. 2001, 114, 3737–3747. [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.B., et al., Cholera. Lancet, 2012. 379(9835): p. 2466-2476.

- Smirnova, N.I., et al., Molecular-genetic peculiarities of classical biotype Vibrio cholerae, the etiological agent of the last outbreak Asiatic cholera in Russia. Microb Pathog, 2004. 36(3): p. 131-9.

- Ghosh, P.; Sinha, R.; Samanta, P.; Saha, D.R.; Koley, H.; Dutta, S.; Okamoto, K.; Ghosh, A.; Ramamurthy, T.; Mukhopadhyay, A.K. Haitian Variant Vibrio cholerae O1 Strains Manifest Higher Virulence in Animal Models. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 111. [CrossRef]

- Satchell, K.J.F.; Jones, C.J.; Wong, J.; Queen, J.; Agarwal, S.; Yildiz, F.H. Phenotypic Analysis Reveals that the 2010 Haiti Cholera Epidemic Is Linked to a Hypervirulent Strain. Infect. Immun. 2016, 84, 2473–2481. [CrossRef]

- Samanta, P.; Saha, R.N.; Chowdhury, G.; Naha, A.; Sarkar, S.; Dutta, S.; Nandy, R.K.; Okamoto, K.; Mukhopadhyay, A.K. Dissemination of newly emerged polymyxin B sensitive Vibrio cholerae O1 containing Haitian-like genetic traits in different parts of India. J. Med Microbiol. 2018, 67, 1326–1333. [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Li, R.; Raes, J.; Arumugam, M.; Burgdorf, K.S.; Manichanh, C.; Nielsen, T.; Pons, N.; Levenez, F.; Yamada, T.; et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 2010, 464, 59–65. [CrossRef]

- Sender, R.; Fuchs, S.; Milo, R. Are We Really Vastly Outnumbered? Revisiting the Ratio of Bacterial to Host Cells in Humans. Cell 2016, 164, 337–340, Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26824647/ (accessed on).

- Arumugam, M.; Raes, J.; Pelletier, E.; Le Paslier, D.; Yamada, T.; Mende, D.R.; Fernandes, G.R.; Tap, J.; Bruls, T.; Batto, J.M.; et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature 2011, 473, 174–180. [CrossRef]

- Faith, J.J.; McNulty, N.P.; Rey, F.E.; Gordon, J.I. Predicting a Human Gut Microbiota’s Response to Diet in Gnotobiotic Mice. Science 2011, 333, 101–104. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, T.S.B.; Raes, J.; Bork, P. The Human Gut Microbiome: From Association to Modulation. Cell 2018, 172, 1198–1215. [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, P.C.; Marcobal, A.; Ursell, L.K.; Smits, S.A.; Sonnenburg, E.D.; Costello, E.K.; Higginbottom, S.K.; Domino, S.E.; Holmes, S.P.; Relman, D.A.; et al. Genetically dictated change in host mucus carbohydrate landscape exerts a diet-dependent effect on the gut microbiota. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013, 110, 17059–17064. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Limenitakis, J.P.; Fuhrer, T.; Geuking, M.B.; Lawson, M.A.; Wyss, M.; Brugiroux, S.; Keller, I.; Macpherson, J.A.; Rupp, S.; et al. The outer mucus layer hosts a distinct intestinal microbial niche. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8292. [CrossRef]

- Sicard, J.-F.; Le Bihan, G.; Vogeleer, P.; Jacques, M.; Harel, J. Interactions of Intestinal Bacteria with Components of the Intestinal Mucus. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 387. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.U.; Eeckels, R.; Alam, A.; Rahman, N. Cholera, rotavirus and ETEC diarrhoea: some clinico-epidemiological features. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1988, 82, 485–488. [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, A.; Ahmed, A.M.S.; Subramanian, S.; Griffin, N.W.; Drewry, L.L.; Petri, W.A.; Haque, R.; Ahmed, T.; Gordon, J.I. Members of the human gut microbiota involved in recovery from Vibrio cholerae infection. Nature 2014, 515, 423–426. [CrossRef]

- David, L.A.; Weil, A.; Ryan, E.T.; Calderwood, S.B.; Harris, J.B.; Chowdhury, F.; Begum, Y.; Qadri, F.; LaRocque, R.C.; Turnbaugh, P.J. Gut Microbial Succession Follows Acute Secretory Diarrhea in Humans. mBio 2015, 6, e00381-15–15. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., J. Xu, and Y. Chen, Regulation of Neurotransmitters by the Gut Microbiota and Effects on Cognition in Neurological Disorders. Nutrients, 2021. 13(6).

- Silva, Y.P.; Bernardi, A.; Frozza, R.L. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids From Gut Microbiota in Gut-Brain Communication. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2020, 11, 25. [CrossRef]

- Breit, S.; Kupferberg, A.; Rogler, G.; Hasler, G. Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain–Gut Axis in Psychiatric and Inflammatory Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 44. [CrossRef]

- Heijtz, R.D.; Wang, S.; Anuar, F.; Qian, Y.; Björkholm, B.; Samuelsson, A.; Hibberd, M.L.; Forssberg, H.; Pettersson, S. Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 3047–3052. [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, K.M.; Kang, N.; Bienenstock, J.; Foster, J.A. Reduced anxiety-like behavior and central neurochemical change in germ-free mice. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2011, 23, 255–e119. [CrossRef]

- Spira, W.M.; Sack, R.B.; Froehlich, J.L. Simple adult rabbit model for Vibrio cholerae and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli diarrhea. Infect. Immun. 1981, 32, 739–747. [CrossRef]

- Burrows, W.; Musteikis, G.M. Cholera Infection and Toxin in the Rabbit Ileal Loop. J. Infect. Dis. 1966, 116, 183–190. [CrossRef]

- Withey, J.H.; Nag, D.; Plecha, S.C.; Sinha, R.; Koley, H. Conjugated Linoleic Acid Reduces Cholera Toxin Production In Vitro and In Vivo by Inhibiting Vibrio cholerae ToxT Activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 7471–7476. [CrossRef]

- Matson, J.S., Infant Mouse Model of Vibrio cholerae Infection and Colonization, in Vibrio Cholerae: Methods and Protocols, A.E. Sikora, Editor. 2018, Springer New York: New York, NY. p. 147-152.

- Nygren, E.; Li, B.-L.; Holmgren, J.; Attridge, S.R. Establishment of an Adult Mouse Model for Direct Evaluation of the Efficacy of Vaccines against Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 2009, 77, 3475–3484. [CrossRef]

- Sawasvirojwong, S.; Srimanote, P.; Chatsudthipong, V.; Muanprasat, C. An Adult Mouse Model of Vibrio cholerae-induced Diarrhea for Studying Pathogenesis and Potential Therapy of Cholera. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2293. [CrossRef]

- Runft, D.L.; Mitchell, K.C.; Abuaita, B.H.; Allen, J.P.; Bajer, S.; Ginsburg, K.; Neely, M.N.; Withey, J.H. Zebrafish as a Natural Host Model for Vibrio cholerae Colonization and Transmission. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 1710–1717. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.C. and J.H. Withey, Danio rerio as a Native Host Model for Understanding Pathophysiology of Vibrio cholerae, in Vibrio Cholerae: Methods and Protocols, A.E. Sikora, Editor. 2018, Humana Press Inc: Totowa. p. 97-102.

- Nag, D., et al., Quantifying Vibrio cholerae Colonization and Diarrhea in the Adult Zebrafish Model. J Vis Exp, 2018(137).

- Stephens, W.Z.; Burns, A.R.; Stagaman, K.; Wong, S.; Rawls, J.F.; Guillemin, K.; Bohannan, B.J.M. The composition of the zebrafish intestinal microbial community varies across development. ISME J. 2016, 10, 644–654. [CrossRef]

- Senderovich, Y.; Izhaki, I.; Halpern, M. Fish as Reservoirs and Vectors of Vibrio cholerae. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e8607–e8607. [CrossRef]

- Breen, P.; Winters, A.D.; Theis, K.R.; Withey, J.H. Vibrio cholerae Infection Induces Strain-Specific Modulation of the Zebrafish Intestinal Microbiome. Infect. Immun. 2021, 89, e0015721. [CrossRef]

- Kuil, L.E.; Chauhan, R.K.; Cheng, W.W.; Hofstra, R.M.W.; Alves, M.M. Zebrafish: A Model Organism for Studying Enteric Nervous System Development and Disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- Roeselers, G.; Mittge, E.K.; Stephens, W.Z.; Parichy, D.M.; Cavanaugh, C.M.; Guillemin, K.; Rawls, J.F. Evidence for a core gut microbiota in the zebrafish. ISME J. 2011, 5, 1595–1608. [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.J.; Bryda, E.C.; Gillespie, C.H.; Ericsson, A.C. Microbial modulation of behavior and stress responses in zebrafish larvae. Behav. Brain Res. 2016, 311, 219–227. [CrossRef]

- Phelps, D.; Brinkman, N.E.; Keely, S.P.; Anneken, E.M.; Catron, T.R.; Betancourt, D.; Wood, C.E.; Espenschied, S.T.; Rawls, J.F.; Tal, T. Microbial colonization is required for normal neurobehavioral development in zebrafish. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11244–11244. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Ranspach, L.E.; Luo, X.; Cianciolo, L.T.; Fogerty, J.; Perkins, B.D.; Thummel, R. Vision and sensorimotor defects associated with loss of Vps11 function in a zebrafish model of genetic leukoencephalopathy. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Breen, P.; Winters, A.D.; Nag, D.; Ahmad, M.M.; Theis, K.R.; Withey, J.H. Internal Versus External Pressures: Effect of Housing Systems on the Zebrafish Microbiome. Zebrafish 2019, 16, 388–400. [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Walters, W.A.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Huntley, J.; Fierer, N.; Owens, S.M.; Betley, J.; Fraser, L.; Bauer, M.; et al. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1621–1624. [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, D.J.; Gerlach, N.M.; Slowinski, S.P.; Corcoran, K.P.; Winters, A.D.; Soini, H.A.; Novotny, M.V.; Ketterson, E.D.; Theis, K.R. Social Environment Has a Primary Influence on the Microbial and Odor Profiles of a Chemically Signaling Songbird. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 4. [CrossRef]

- Quast, C., et al., The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res, 2013. 41(Database issue): p. D590-6.

- Randlett, O.; Wee, C.L.; A Naumann, E.; Nnaemeka, O.; Schoppik, D.; E Fitzgerald, J.; Portugues, R.; Lacoste, A.M.B.; Riegler, C.; Engert, F.; et al. Whole-brain activity mapping onto a zebrafish brain atlas. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 1039–1046. [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.C.; Haehnel, M.; Levi, R.; Akanyeti, O.; Ballo, A.; Haehnel-Taguchi, M. Physiology of afferent neurons in larval zebrafish provides a functional framework for lateral line somatotopy. J. Neurophysiol. 2012, 107, 2615–2623. [CrossRef]

- Vanwalleghem, G.; Heap, L.A.; Scott, E.K. A profile of auditory-responsive neurons in the larval zebrafish brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 2017, 525, 3031–3043. [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, R.E., et al., Broad frequency sensitivity and complex neural coding in the larval zebrafish auditory system. Curr Biol, 2021. 31(9): p. 1977-1987.e4.

- Basnet, R.M.; Zizioli, D.; Taweedet, S.; Finazzi, D.; Memo, M. Zebrafish Larvae as a Behavioral Model in Neuropharmacology. Biomedicines 2019, 7, 23. [CrossRef]

- Perathoner, S.; Cordero-Maldonado, M.L.; Crawford, A.D. Potential of zebrafish as a model for exploring the role of the amygdala in emotional memory and motivational behavior. J. Neurosci. Res. 2016, 94, 445–462. [CrossRef]

- Lucini, C.; D’angelo, L.; Cacialli, P.; Palladino, A.; De Girolamo, P. BDNF, Brain, and Regeneration: Insights from Zebrafish. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3155. [CrossRef]

- Beppi, C.; Straumann, D.; Bögli, S.Y. Author Correction: A model-based quantification of startle reflex habituation in larval zebrafish. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–2. [CrossRef]

- Rihel, J.; Prober, D.A.; Arvanites, A.; Lam, K.; Zimmerman, S.; Jang, S.; Haggarty, S.J.; Kokel, D.; Rubin, L.L.; Peterson, R.T.; et al. Zebrafish Behavioral Profiling Links Drugs to Biological Targets and Rest/Wake Regulation. Science 2010, 327, 348–351. [CrossRef]

- Borla, M.A.; Palecek, B.; Budick, S.; O’malley, D.M. Prey Capture by Larval Zebrafish: Evidence for Fine Axial Motor Control. Brain, Behav. Evol. 2002, 60, 207–229. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Bongu, S.; Hughes, S.P.; Gaboury, E.K.; Carver, C.E.; Luo, X.; Bessert, D.A.; Thummel, R. Hypomyelinated vps16 Mutant Zebrafish Exhibit Systemic and Neurodevelopmental Pathologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7260. [CrossRef]

- Kalueff, A.V.; Gebhardt, M.; Stewart, A.M.; Cachat, J.M.; Brimmer, M.; Chawla, J.S.; Craddock, C.; Kyzar, E.J.; Roth, A.; Landsman, S.; et al. Towards a Comprehensive Catalog of Zebrafish Behavior 1.0 and Beyond. Zebrafish 2013, 10, 70–86. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.M.; Braubach, O.; Spitsbergen, J.; Gerlai, R.; Kalueff, A.V. Zebrafish models for translational neuroscience research: from tank to bedside. Trends Neurosci. 2014, 37, 264–278. [CrossRef]

- Moon, K.; Kang, I.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.-J.; Cho, J.-C. Genomic and ecological study of two distinctive freshwater bacteriophages infecting a Comamonadaceae bacterium. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Sheu, S.-Y., et al., Rheinheimera coerulea sp. nov., isolated from a freshwater creek, and emended description of genus Rheinheimera Brettar et al. 2002. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2018. 68(7): p. 2340-2347.

- Chen, W.-M., et al., Flectobacillus fontis sp. nov., isolated from a freshwater spring. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2017. 67(2): p. 336-342.

- Yoon, J.-H.; Kang, S.-J.; Oh, H.W.; Lee, J.-S.; Oh, T.-K. Brevundimonas kwangchunensis sp. nov., isolated from an alkaline soil in Korea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2006, 56, 613–617. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.P.; Pembroke, J.T. Brevundimonas spp: Emerging global opportunistic pathogens. Virulence 2018, 9, 480–493. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).