1. Introduction

Recently, machine learning (ML) has been applied to various fields, and its classification algorithms have demonstrated high performance. ML has been actively used in the medical industry, particularly in medical imaging [

1,

2], and in health metric analyses and predictions [

3].

There is a wide range of methods available for assessing muscle function in rehabilitation patients. However, traditional techniques such as Manual Muscle Testing (MMT) provide limited detailed information about muscle function and fail to identify the underlying factors contributing to muscle dysfunction. Additionally, treatment approaches for patients with impaired muscle function are often generalized and not tailored to individual needs. This lack of specificity in both assessment and intervention highlights a significant gap in personalized rehabilitation strategies, underscoring the need for more comprehensive and precise methods to evaluate and address muscle function deficits.

We aimed to develop a classification method that can replace various assessment methods for patients undergoing rehabilitation and performed analysis based on the results obtained from a classification method to establish patient treatment plans. To this end, we formulated the following research questions:

How can we handle the imbalance between data from normal and abnormal cases? One challenge in applying ML to healthcare is the imbalance between data from normal and abnormal cases. It is easier to obtain data from normal individuals than from patients presenting specific health conditions, and not all patient data are abnormal. Consequently, accurately labeling abnormality may be challenging.

How can we use patient treatment plans considering classification results? In addition to achieving a high classification performance, developing an interpretable classifier is crucial for applying the results to support patient treatment planning. The classifier interpretability may increase trust and usability, thus facilitating the development of treatment plans based on classification results.

To address the first research question, we adopted a one-class classification method. Several methods have been developed to perform this task [

4,

5], from which we used a one-class support vector machine (SVM) [

6]. This type of SVM is well-suited for anomaly detection, which identifies datapoints that differ substantially from most of the data. It captures the data distribution and identifies outliers. Another advantage of the one-class SVM is its ability to handle imbalanced datasets, where one class is represented by drastically fewer samples than another one. The one-class SVM can handle situations in which only positive samples are available and negative samples are unknown or difficult to obtain. Hence, it is adequate for medical assessments, especially when collecting data from patients with rare conditions is challenging.

To address the second research question, we devised the nearest boundary point (NBP) to solve for the shortest Mahalanobis distance. Specifically, based on the decision function of the one-class SVM formulated as a mixture of normal distributions, we standardized and analytically derived a series of steps to obtain and reconstruct the NBP.

To validate the feasibility and applicability of the proposed method, we first performed simulations using artificially generated two-dimensional (2D) nonlinear data. We chose 2D data because they allow for easy visualization and understanding of intermediate steps in addition to verification. After analyzing the simulation results, we tested the proposed interpretable SVM on real data. We trained the one-class classification model on biosensing measurements from normal individuals and classified patient data to solve the NBP problem for identified abnormal data. We analyzed the major factors causing abnormal classifications and investigated feasible treatment methods.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we introduce an interpretable one-class SVM with Gaussian kernels.

Section 3 presents the simulation results, and

Section 4 reports the analysis of an application to rehabilitation based on the proposed method, including the identification of the main factors and corresponding treatment options for patients classified as abnormal. The simulation and application results validate the effectiveness and interpretability of the proposed SVM. Finally,

Section 5 presents our concluding remarks.

2. Interpretable One-Class SVM

2.1. One-Class Classification of Normally Distributed Data

We address one-class classification as a research question. One-class classification detects anomalies by defining the boundary that encloses normal data. In this subsection, we discuss the case of normal data that follow a normal distribution.

The probability density function of data that following a normal distribution is expressed as

where

,

, and

d denote the mean, covariance, and dimension of

, respectively.

When data follow a normal distribution, an appropriate boundary can be determined by fitting the data to a normal distribution with a certain mean and covariance and then obtaining the contour of the probability density function, which can be determined by a desired acceptance rate or other approaches.

For example, to determine the boundary of 2D data

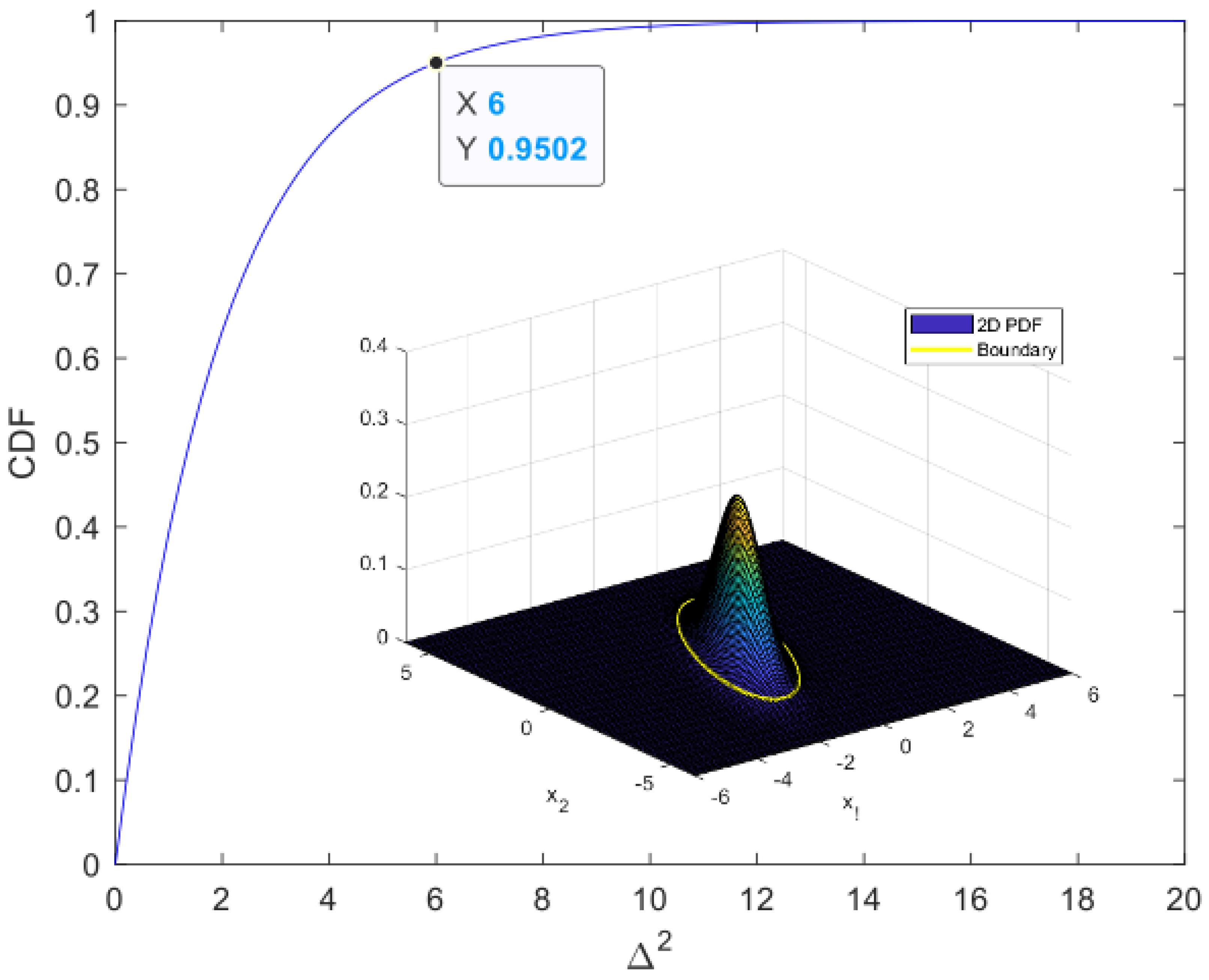

that follow a normal distribution with an acceptance rate of approximately 0.9502, we can determine the distance at which the cumulative distribution function of the normal distribution is 0.9502, as shown in

Figure 1, and draw a contour with the same distance to obtain the boundary.

The obtained boundary serves as a criterion for detecting anomalies, and new data can be classified as normal if they fall within the boundary or abnormal if they fall outside the boundary.

2.2. Classification Interpretability Using NBP

We obtain the boundary for normally distributed data, thereby being able to distinguish between normal and abnormal data based on whether they fall within or outside the boundary. If the data are classified as abnormal because they fall outside the boundary, we analyze the interpretability of classification and the changes that would be necessary for them to be classified as normal.

To ensure interpretability, we aim to solve the NBP problem by finding the boundary point closest to a datapoint

that falls outside the boundary. To determine the concept of nearest point, we must first define a distance, which we take to be the Mahalanobis distance. Given a probability distribution with mean

and positive-definite covariance

, Mahalanobis distance

is defined as

The Mahalanobis distance is an effective multivariate metric of the distance between a point (vector) and a data distribution. It is suitable for multivariate anomaly detection, classification of highly imbalanced datasets, one-class classification, and untapped use cases. In particular, when Mahalanobis distance

of point

from the distribution in (

1) is constant, the point lies on the same contour as the normal probability density function. Therefore, the boundary of normal data can be expressed as

where

R is a real-valued constant.

If the dataset follows normal distribution

and the boundary is determined by (

3), the optimization problem can be solved to find the NBP of

observed outside the boundary. Given

,

, and

, we have

where

denotes the NBP. To solve (4), we obtain the following Laplacian:

The partial derivatives of the Laplacian are given by

From (7), we obtain the NBP as follows:

By substituting (8) into (6), we obtain

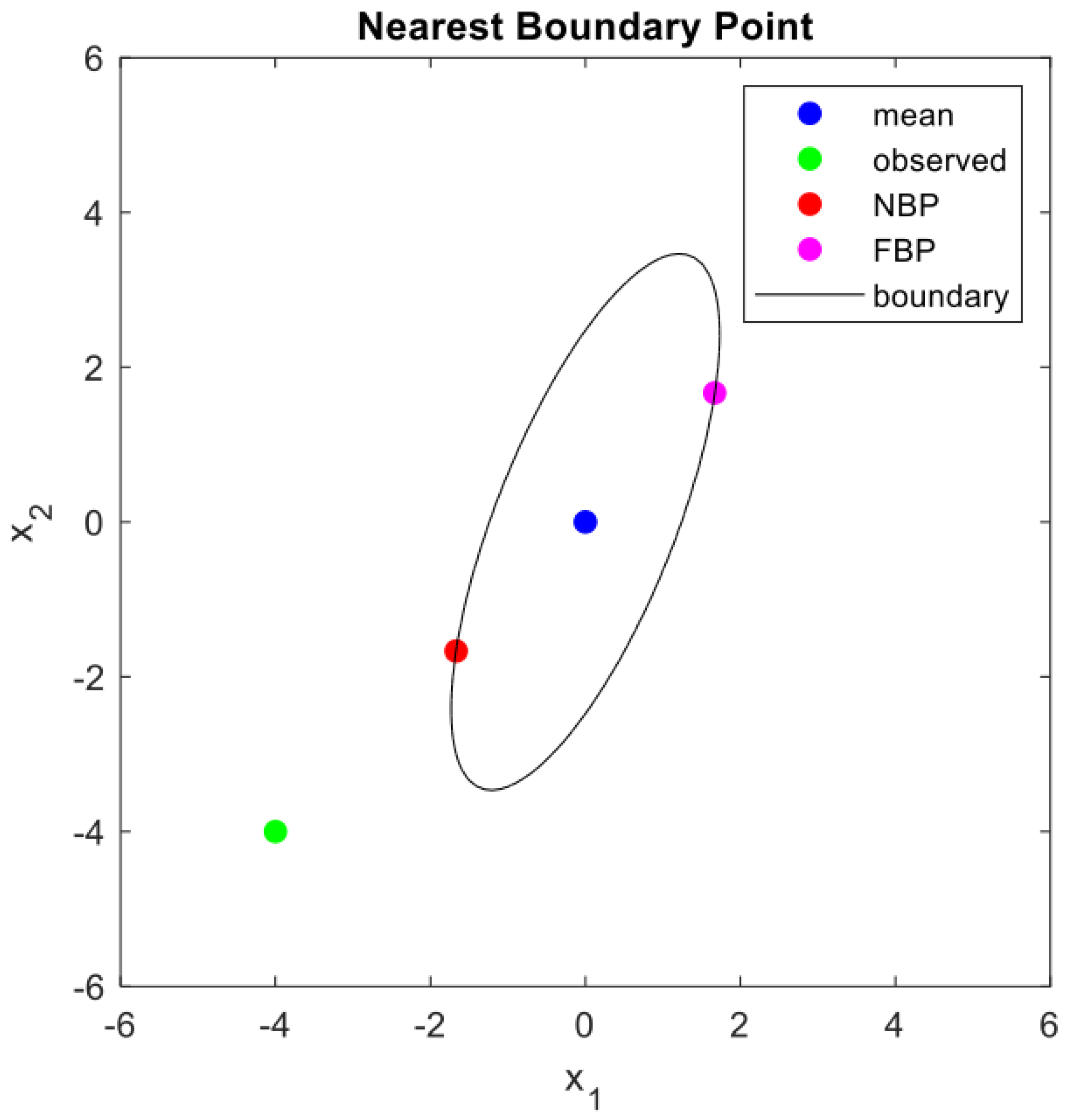

If the sign of the square root term in (9) is positive, boundary point

is the nearest one, and if the sign is negative,

is the farthest boundary point, as shown in

Figure 2.

By obtaining the NBP, , for a new observation, , outside the boundary, we can gain insights into interpretation, such as why is outside the boundary, how far it is from the boundary, and which element values must be increased or decreased to classify it as a normal point.

2.3. Standardization of Non-Normally Distributed Data

In practice, data may not be normally distributed. To address this issue, we model data as a mixture of multiple normal distributions. When data that do not follow a normal distribution are represented as a mixture of multiple normal distributions, we can apply a normalization method.

Let

be a

d-dimensional random variable generated by a mixture of multiple normal distributions as follows:

where

,

,

represents the probability density function of a

d-dimensional normal distribution with mean

and covariance

, and

N is the number of components in the mixture. We introduce membership weight (or posterior probability)

of class

i for

by using Bayesâ theorem as follows:

where

. By applying the soft assignment proposed in [

7], we obtain the following standardization formula:

where

is the standardized

d-dimensional random vector transformed from

for

being a

identity matrix.

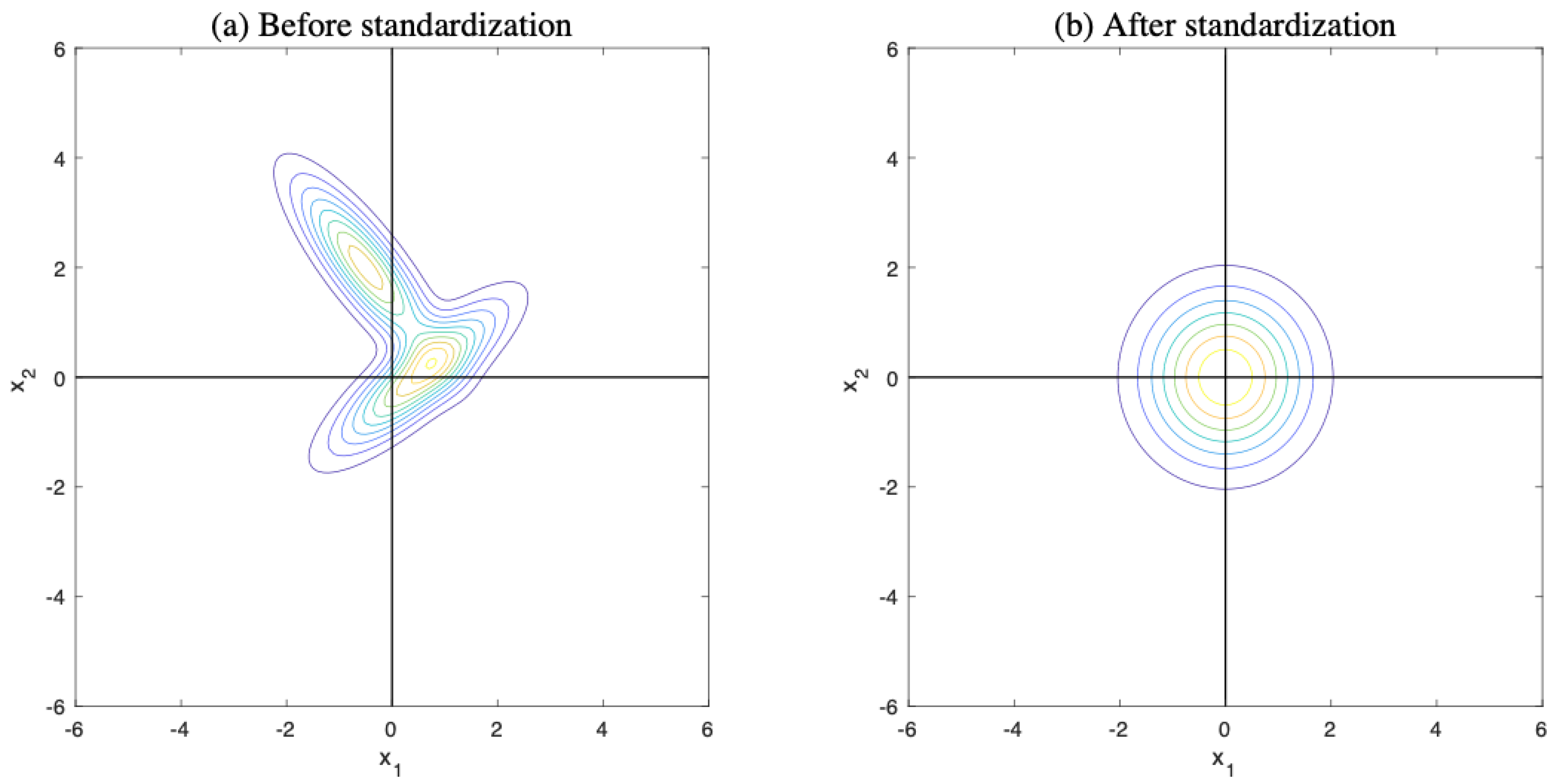

Figure 3 illustrates the standardization of a mixture of two normal distributions.

2.4. NBP of One-Class SVM

The one-class SVM belongs to a family of ML algorithms known as kernel methods that use kernel functions to represent input features into a new, often higher-dimensional, space. Thus, it facilitates distinguishing between different classes, and the resulting decision boundary is often simpler and more interpretable than that in the original feature space. This approach avoids the need for explicit feature transformations, which can be computationally expensive, and is often referred to as the kernel trick.

A Gaussian kernel is commonly used to perform the kernel trick and is universal, meaning that it can uniformly approximate any arbitrary continuous target function. Gaussian kernels offer a valuable advantage by transferring data from the original plane into a hyperplane for analysis. This capability can resolve a significant limitation of the Mahalanobis distance which is known to perform inadequately for datasets characterized by linearity and heteroscedasticity. By utilizing Gaussian kernels, the shortcomings associated with Mahalanobis distance in these contexts can be effectively mitigated.

After training, the decision function of the SVM for observation

can be obtained as follows:

where

denotes the

i-th support vector,

b is the bias term,

N is the number of support vectors, and

is a Gaussian kernel with width

and given by

Because the decision function in (

13) is a linear sum of Gaussian functions, we have the following relationship between

in (

13) and

in (

10):

where

,

,

, and

for all

.

As shown in (

15),

takes the form of multiple mixtures with normal distributions. As

K and

b are constants, we can transform the distribution of an

space into a standardized normal distribution of another

space using (

11) and (

12). The posterior probability can be derived as

As

and

, we have

As

follows a normal distribution, that is,

, we obtain

from (

9) as follows:

By numerically computing

from training data, we calculate

using (

17) and derive the Mahalanobis distance of the boundary as

. Substituting

into (

8), we obtain the following NBP in the

space:

and reconstructing

into the

space, we obtain the NBP of the new observation,

.

As

cannot be computed explicitly, we use

instead of

and calculate (

17) by letting

and applying (

19) and (

20) repeatedly until

converges.

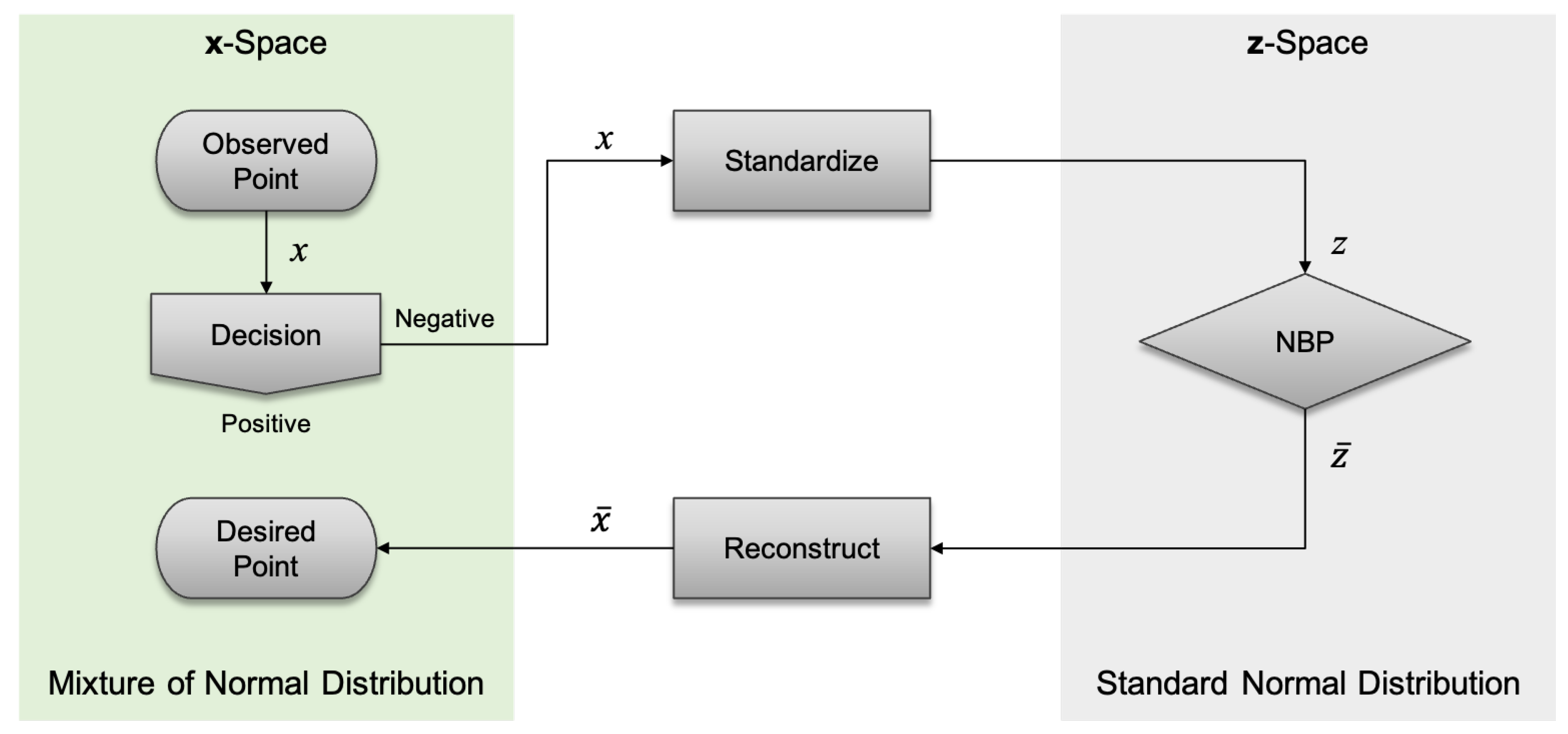

Figure 4 illustrates the proposed process for determining the desired point (that is, NBP) from the SVM decision function.

3. Simulation Results

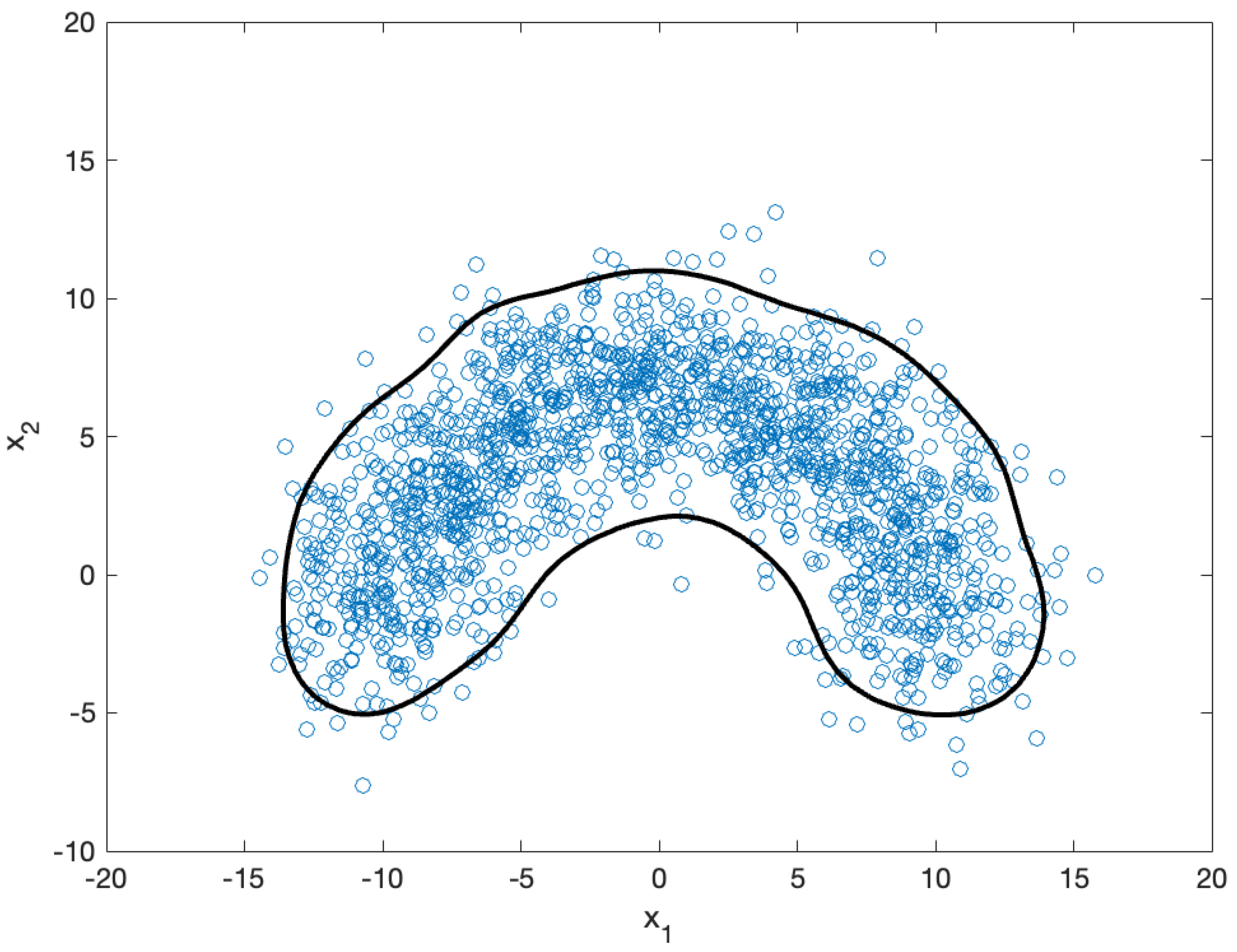

This section presents simulation results used to validate the proposed method for solving the NBP in the one-class SVM. The results are reported stepwise, and the final outcomes are provided. For the simulation, we used 2D nonlinear data. As shown in

Figure 5, we randomly sampled 1571 datapoints (blue circles) from a normal distribution with mean

and covariance

, where

and

is a 2D identity matrix. We then applied the one-class SVM to extract a region bounded by a decision function (black contour in the figure).

Figure 6 shows the standardized datapoints (red circles) and the boundary in the

space, which correspond to the original datapoints in the

space in

Figure 5. After transformation, the data were normally distributed and centered at the origin of the

plane.

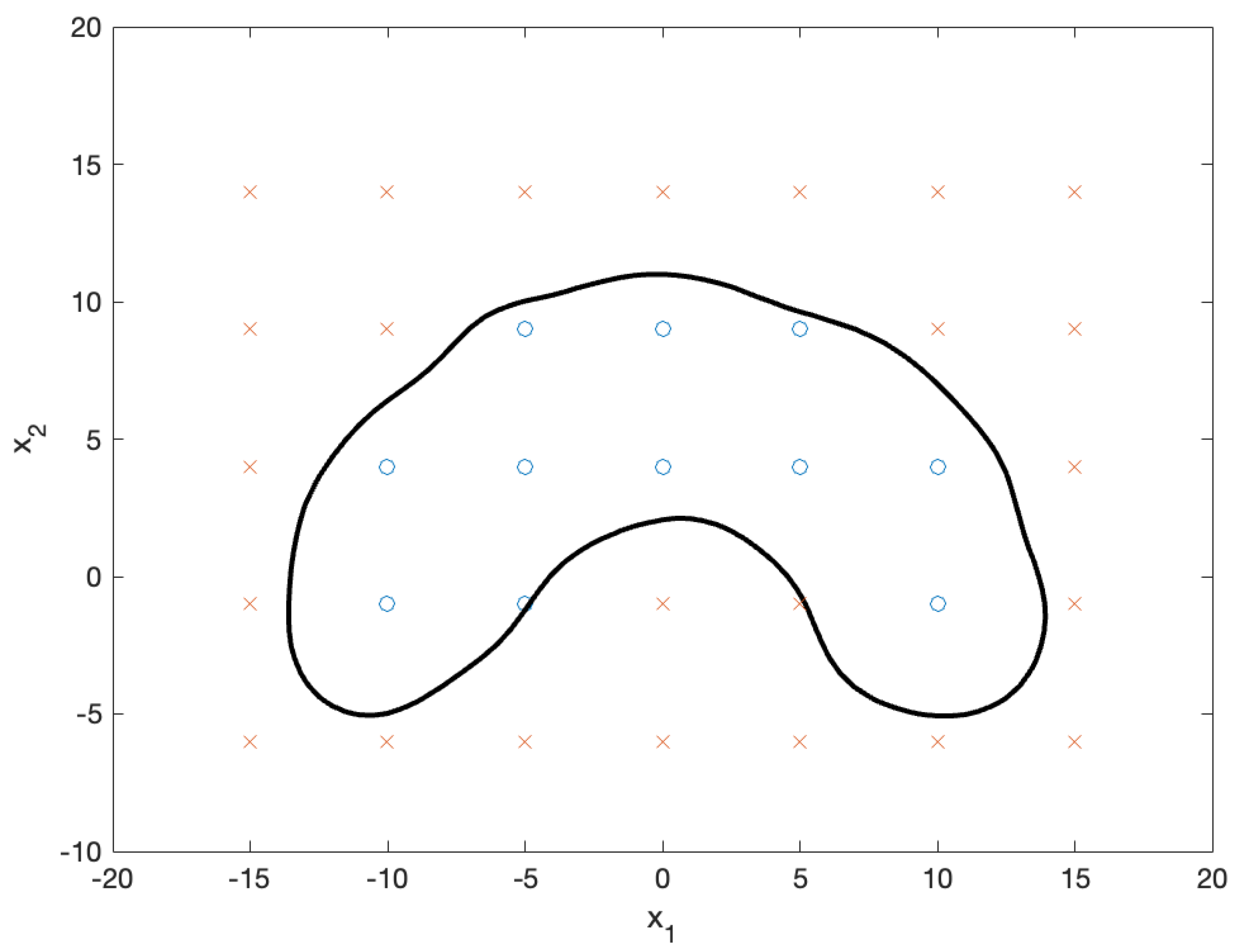

The decision function for the SVM was obtained through training.

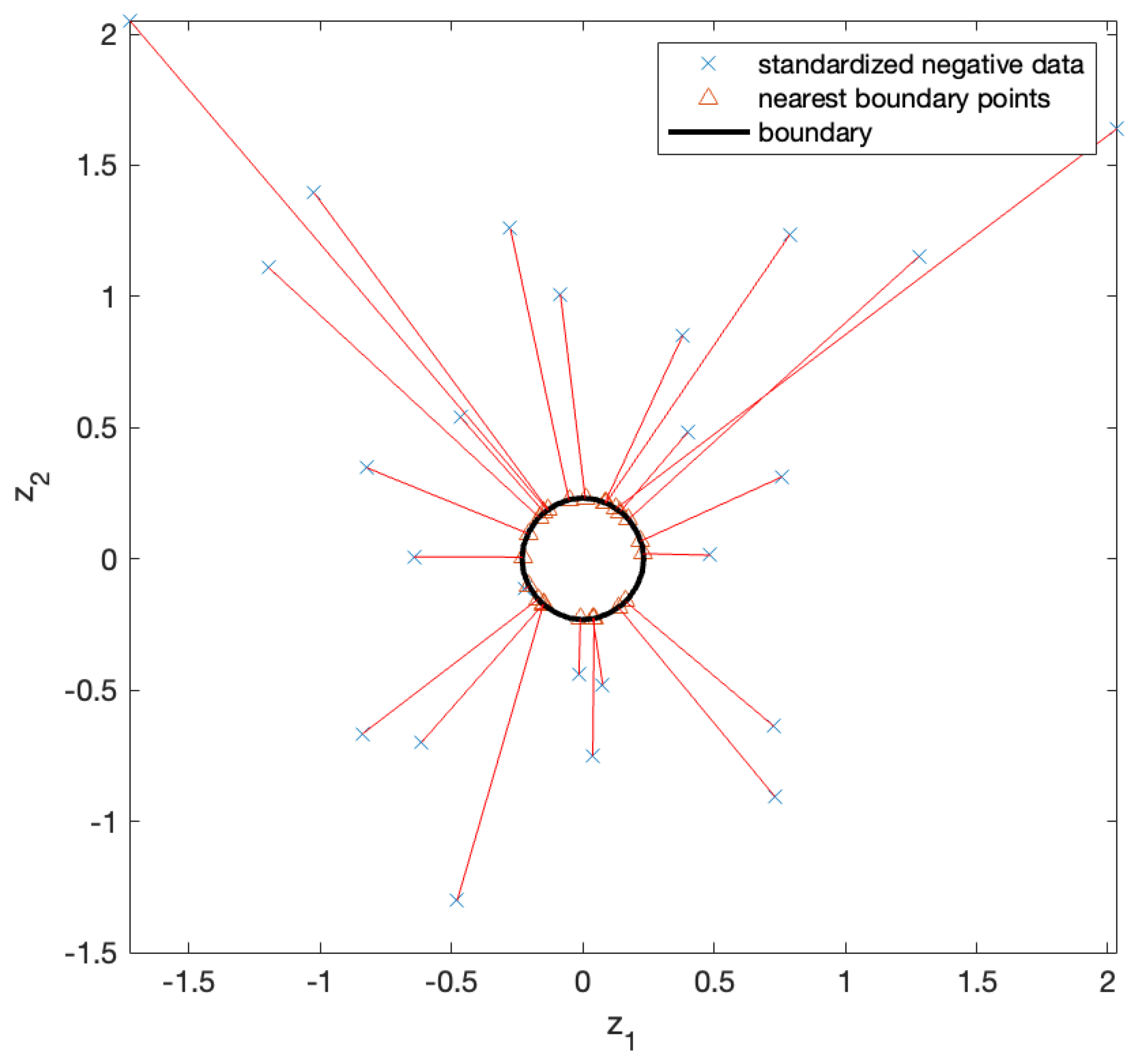

Figure 7 shows the test data used to evaluate the decision function. A positive classification was assigned to the test data that fell within the decision boundary, whereas a negative classification was assigned to the test data outside the boundary. As we focused on negative samples, we solved the NBP problem for negative test samples. First, we standardized the negative test samples and computed their NBPs, as shown in

Figure 8. The x marks in the figure represent the standardized negative test samples, and the triangular marks represent their NBPs. The NBPs lay on the black contour that represents the decision boundary.

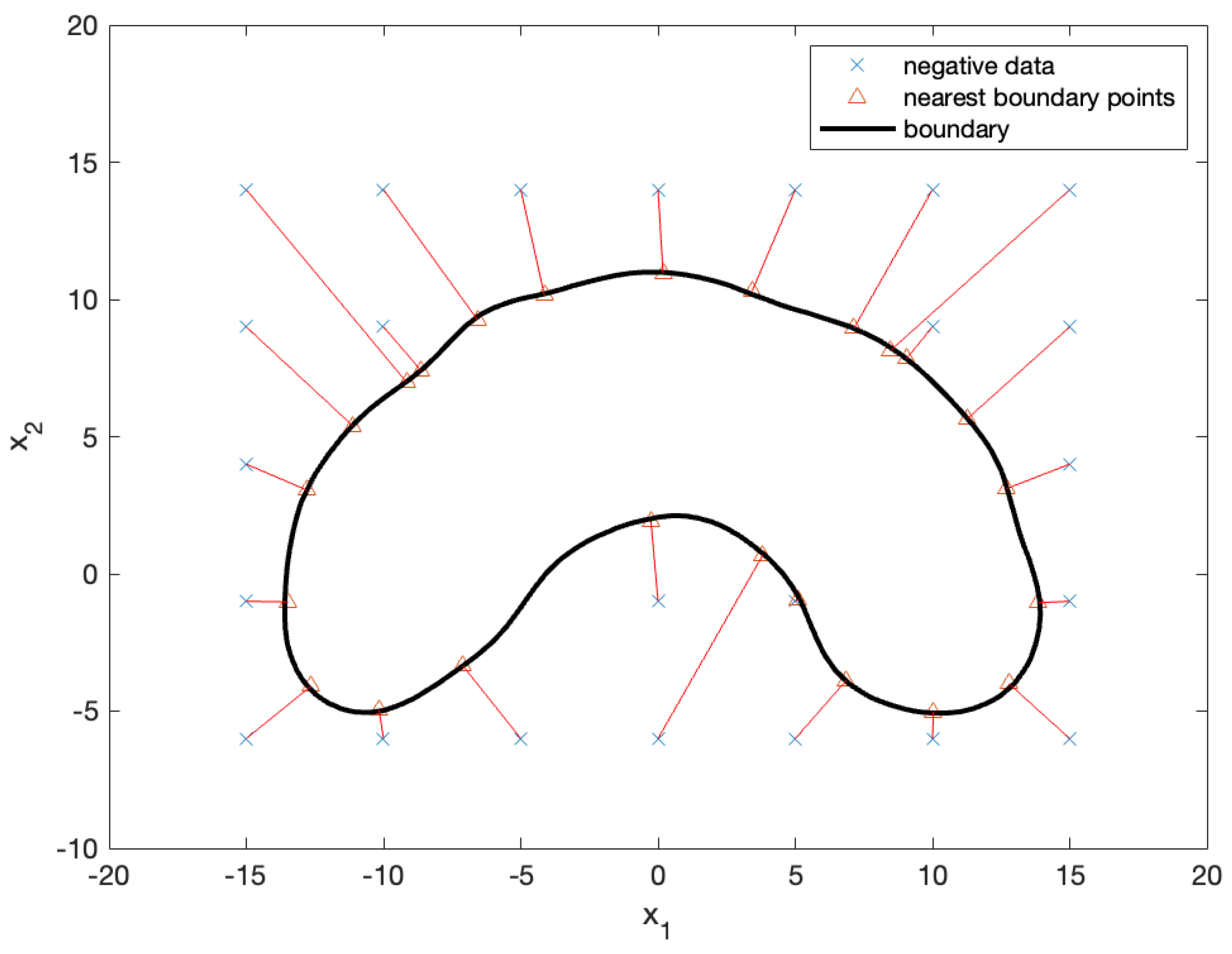

By mapping the datapoints and NBPs from the

plane, as shown in

Figure 8, onto the

plane, we obtained the final solution (that is, desired points), as illustrated in

Figure 9. The x marks in the figure represent negative test samples, whereas the triangular marks represent their NBPs. The NBPs lay on the black contour that represents the decision boundary.

4. Applications

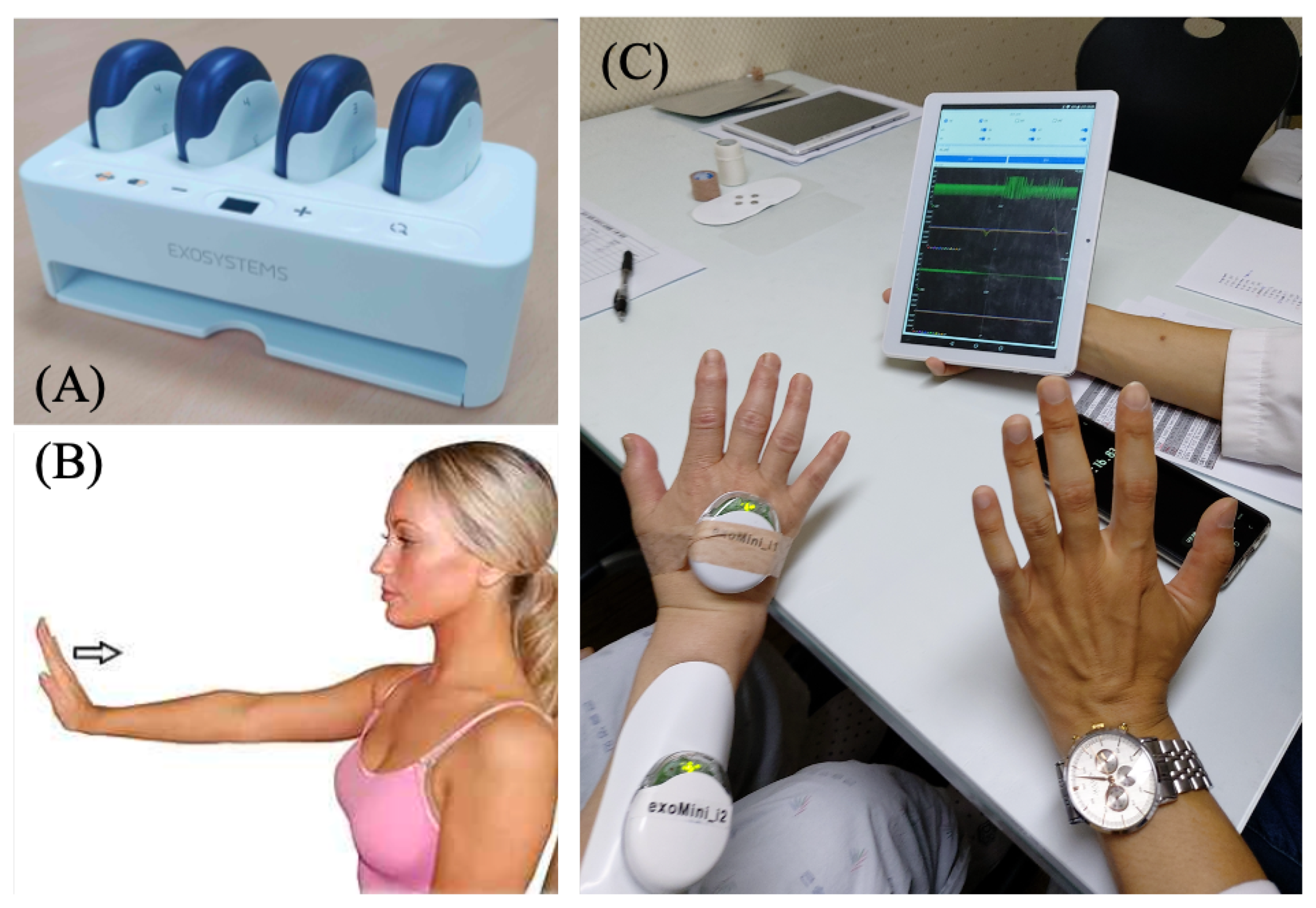

We present a practical application of the proposed interpretable SVM to rehabilitation assessment along with experimental results obtained from analysis and testing. Our aims were to evaluate the forearm muscle function of patients undergoing rehabilitation through measurements of surface electromyography (sEMG) and an inertial measurement unit (IMU) as well as to determine appropriate countermeasures for functional electric stimulation (FES) and physical therapy using a robot. Specifically, we employed the exoPill sensor [

8], which is a modular device developed by ExoSystems. It integrates sEMG electrodes and an IMU, as depicted in

Figure 10A. We considered wrist extension as the evaluated rehabilitation movement, as illustrated in

Figure 10B, by attaching the sEMG electrodes to the extensor carpi radialis muscles and the IMU to the back of the hand, as shown in

Figure 10C.

We recruited 40 participants for our study, including 20 healthy individuals and 20 patients who recovered from stroke. Each participant wore a measuring device and alternated resting and wrist extensions 10 times at 5 s intervals. For the stroke patients, the measuring device was worn on the side affected by hemiplegia, and an upper-extremity Fugl–Meyer assessment (FMA) was conducted by a clinical staff member. The maximum score for the FMA was 14.

From the sEMG signal, features such as power (PWR), median frequency (MDF), mean frequency (MNF), and root mean square (RMS) were extracted. From the IMU signal, the velocity (VEL) and range of movement (ROM) were extracted. Using these features from normal individuals as positive samples, we trained the one-class SVM and obtained a decision function by fine-tuning. To improve the training results, we performed data augmentation through a boosting technique.

The one-class SVM decision function trained using the features extracted from normal individuals was applied to the features of stroke patients to classify the muscle function of each patient. For patients classified as abnormal, the NBP was solved to analyze the causes of such classification and possible countermeasures for improving rehabilitation. This process was performed considering the 14 patients whose data were excluded owing to sensor signal omission or mismeasurement.

The evaluation results are listed in

Table 1. Out of the 14 patients, 10 were classified as abnormal. For each of these 10 patients, we analyzed the differences between the measurements and NBPs per feature.

A higher difference indicated that more effort was required for patients to be classified as normal. To identify the main factors contributing to patient’s abnormalities, we used the standard deviation of the measurements from normal individuals. The corresponding results are listed in

Table 2, where + and − indicate normal and abnormal, respectively.

By applying the interpretable SVM proposed in this paper, it is possible to classify the muscle function of patients as either normal or abnormal based on sEMG and IMU measurements. In cases where the function is classified as abnormal, the method can identify the main factors responsible for the abnormality. Depending on these factors, such as whether the abnormal muscle function is due to issues with muscle recruitment or physical problems like muscle contractures, appropriate treatments can be prescribed. These treatments may include FES for muscle recruitment issues, or robotics approach (e.g., exoskeleton) for physical problems.

As indicated in

Table 2, the SVM decision function classified patients with FMA scores of 14 (that is, the highest score) as normal and those with lower scores as abnormal. In the abnormal group, the main abnormality factors were identified by solving the NBP problem, and different factors were identified per patient. Once the main abnormality factors for each patient were determined, PWR, MDF, MNF, and RMS derived from sEMG signals were used to define countermeasures for FES treatment. On the other hand, VEL and ROM provided guidelines for using robotic therapy as physical assistance. For example, for patient 3, PWR and MDF were the main abnormal factors, indicating the need for physical therapy using FES to address muscle recruitment issues. Patients 6, 10, 11, and 18 required FES treatment and additional physical therapy using robotic assistance to address movement dynamic issues.

5. Conclusions

We propose an interpretable SVM that enables the derivation of the causes of data classified as abnormal by one-class classification and the analysis of countermeasures for rehabilitation. The proposed method is based on the Mahalanobis distance and involves obtaining the NBP of abnormal data. The NBP indicates the shortest path from the abnormal data to the normal boundary and allows to identify features that contribute to anomaly along with their contribution extent.

The proposed method for obtaining the NBP of abnormal data involves standardizing the SVM decision function. Given that this function with a Gaussian kernel can be expressed as a mixture of normal distributions in the space, we can approximate the decision function to a normal distribution in the space. After standardization, we obtain the NBP in the space and reconstruct it back to the space.

We used a 2D nonlinear dataset to simulate and test the proposed method, validating its feasibility and applicability through simulations. Moreover, we applied the proposed method to rehabilitation. Using sEMG and IMU measurements, we classified the status of the patient’s muscle function and analyzed the underlying causes of anomalies and possible therapeutic countermeasures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Kim, W. and Yoon, D.; methodology, Kim, W.; software, Kim, W.; validation, Kim, W., Kim, H. and Joe, H.; formal analysis, Kim, H.; investigation, Kim, W.; resources, Kim, W.; data curation, Kim, W.; writing—original draft preparation, Kim, W.; writing—review and editing, Kim, W.; visualization, Kim, W.; supervision, Yoon, D.; project administration, Yoon, D.; funding acquisition, Kim, W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Institute of Information and Communications Technology Planning and Evaluation (IITP) under grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (2022-0-00501).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Pusan National University Hospital (approval no. 2107-027-105).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to patients’ privacy issue.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at Pusan National University Hospital for collecting data of muscle function from rehabilitation patients [

9].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest and the funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SVM |

Support Vector Machine |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| NBP |

Nearest Boundary Problem |

| sEMG |

Surface Electromyography |

| IMU |

Inertial Measurement Unit |

| FES |

Functional Electric Stimulation |

| FMA |

Fugl-Meyer Assessment |

| PWR |

Power |

| MDF |

Median Frequency |

| MNF |

Mean Frequency |

| RMS |

Root Mean Square |

| VEL |

Velocity |

| ROM |

Range of Movement |

References

- M. L. Giger, Machine learning in medical imaging, J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 15 (2018), 512–520.

- G. Currie, K. E. Hawk, E. Rohren, A. Vial, and R. Klein, Machine learning and deep learning in medical imaging: Intelligent imaging, J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Sci. 50 (2019), 477–487.

- A. Massaro, G. Ricci, S. Selicato, S. Raminelli, and A. Galiano, Decisional support system with artificial intelligence oriented on health prediction using a wearable device and big data, (2020 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Industry 4.0 and IoT, Roma, Italy), 2020, pp. 718–723.

- Y.-H. Liu and H.-P. Huang, Towards a high-stability EMG recognition system for prosthesis control: A one-class classification based non-target EMG pattern filtering scheme, (2009 IEEE International Conf. Systems, Man and Cybernetics, San Antonio, TX, USA), 2009, pp. 4752–4757.

- Y. Faula, V. Eglin, and S. Bres, One-class detection and classification of defects on concrete surfaces, (2021 IEEE International Conf. Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Melbourne, Australia), 2021, pp. 826–831.

- B. Schölkopf, R. C. Williamson, A. Smola, J. Shawe-Taylor, and J. Platt, Support vector method for novelty detection, Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 12 (1999), 582–588.

- M. Li and A. Schwartzman, Standardization of multivariate Gaussian mixture models and background adjustment of PET images in brain oncology, Ann. Appl. Stat. 12 (2018), 2197–2227.

- exoPill: AI-based wearable healthcare solution, Available from: https://www.exosystems.io/exopill?lang=en [last accessed August 2023].

- Ethical approval, Pusan National University Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB; approval no. 2107-027-105).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).