Preprint

Article

Preparing the Future Public Health Workforce: Integrating Relational Employability to Foster Critical Global Citizenship

Altmetrics

Downloads

120

Views

80

Comments

0

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

This version is not peer-reviewed

Submitted:

19 August 2024

Posted:

20 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

A well-prepared public health workforce is essential for reducing disease burdens and improving population health, requiring an education that addresses global and complex challenges. This paper examines the integration of the relational employability framework in public health education to cultivate critical global citizenship among students and graduates. Our research, conducted at Edith Cowan University in Perth, Western Australia, involved two case studies using qualitative interviews. Case Study 1, drawn from Cook’s doctoral research, explored student experiences with the relational employability framework within an undergraduate capstone unit. Case Study 2, a school-funded project, gathered graduate perspectives to inform ongoing curriculum development. The findings indicate that the relational employability framework enhances global competencies among students and graduates, through research skills development and critical reflective practice. Students reported improved awareness of their learning needs, self-confidence, and an increased ability to engage with diverse perspectives and societal challenges. Graduates highlighted the framework’s role in understanding ethical standards, conducting rigorous research and applying evidence-based practices in professional settings. Additionally, the framework supported the development of a reflective mindset, enabling graduates to make informed, value-based career decisions and advance their professional growth. The study suggests that adopting a relational employability approach can effectively prepare globally competent and reflective public health professionals. We advocate for the broader implementation of this framework in health education and higher education, offering practical recommendations for curriculum transformation. Such an approach will equip future professionals to contribute meaningfully to public health debates and embody the principles of global citizenship in their practice.

Keywords:

Subject: Public Health and Healthcare - Other

Introduction

This paper highlights the importance of integrating global citizenship, through the development of research skills and critical reflective practice, into public health education. By demonstrating how relational employability can foster the development of critical global citizenship among students and graduates, this paper responds to calls for research into the nature and outcomes of undergraduate public health education to shape a “stronger, more well-educated workforce that can face the increasingly complex challenges of better promoting and protecting the health of the public”, both locally and globally [1] (p. 206). Such a workforce is essential for reducing the burden of disease and enhancing the health of populations. We believe this requires the development of critical global citizenship or competency among students/graduates, facilitated through reflective practice and a relational awareness that extends beyond human elements alone, aligning with the work of Cook [2,3]. We, therefore, show how Cook’s [4] relational employability framework can be a valuable approach within university teaching-learning, particularly for the public health discipline, to encourage critical global citizenship thoughts, behaviours and actions. The ultimate goal of this research was to enhance student and graduate career readiness for the future public health workforce.

To demonstrate how this outcome might be achieved, we present findings from our scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) research conducted at Edith Cowan University (ECU) in Perth, Western Australia. Using data from two qualitative studies, we explore whether and how the relational employability framework might support the development of critical global citizenship among students and graduates. Specifically, we examined student and graduate perspectives and experiences regarding a research unit within the Bachelor of Health Science degree, which incorporated relational employability into teaching-learning and assessment.

In the next section, we provide background information on the public health workforce, university curriculum and the need for global citizenship education. We then explain the importance of research skills development and critical reflective practice in public health education before introducing the conceptual framework of relational employability.

Public Health Workforce, University Curriculum and the Need for Global Citizenship Education

Public health aims to support and improve the health of populations through various strategies, including the prevention of communicable and non-communicable disease, health promotion, screening and treatment, and the monitoring and modification of environmental, social, economic and political factors that impact public health [5]. These strategies target the well-documented social determinants of health, which contribute to unjust and preventable health inequities, leading to poorer health outcomes and premature mortality [6]. Baum [7] argues that public health should strive for a society where health is equitably distributed, the environment is sustainable, and policies are proactively used to promote health and equity. In such a society, there would be strong commitment to equity and abundant opportunities for lifelong personal, intellectual, social and emotional development.

While these principles are fundamental to the Bachelor of Health Science degree at ECU, there is an increasing recognition that global citizenship competency should be an integral part of any university’s core curriculum [8]. However, the concept of critical global citizenship could be more prominently featured across the Health Science course; and, as such, this recognition serves as the impetus for this research.

Global citizenship encompasses the social, political, environmental and economic actions taken by globally conscious individuals and communities on a worldwide scale [9]. It acknowledges that individuals are not isolated actors but members of diverse local and global networks [9]. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) suggests that, by encouraging a worldwide sense of belonging and responsibility in the context of sustainable progress, humanity can be motivated to take actions that benefit all communities globally, rather than focusing solely on their own lives, societies and environments [10].

Educators and students are uniquely positioned to embrace and promote global citizenship [2]. The OECD [10] recommends that global competence – a measure of global citizenship – should be taught and assessed in educational settings across four key dimensions:

- Using critical thinking skills to examine local, global and culturally significant issues.

- Engaging with different perspectives and worldviews.

- Engaging in open, appropriate and effective interactions across cultures.

- Helping to build a more just, peaceful, inclusive and environmentally sustainable world.

To achieve global competence, students need support to develop communication skills, perspective-taking, conflict resolution skills and adaptability [10]. They must also learn to reason with information from multiple sources, identify their informational needs and select sources based on relevance and reliability [10]. In the context of public health, the development of strong research skills is particularly crucial for attaining global competence.

Importance of Research Skills

The global need for public health workforce development is well-established, encompassing aspects such as standards, curricula, accreditation, capacity building, and comprehensive teaching and training [11]. Hamelin and Paradis [12] emphasise that bridging the gap between academic and public health practice and policies requires strong research training and transdisciplinary approaches. In Australia, research skills are essential for any public health graduate seeking employment, with the Council of Academic Public Health Institutions Australia [13] identifying key competencies to guide the development of public health and health science curricula. These competencies include:

- Evidence-based data collection

- Knowledge of the social, commercial, environmental and political determinants of health

- Advocacy

- Understanding appropriate research methodologies

- Evaluation skills

- Ethical conduct

However, the current CAPHIA Foundation Competencies do not specifically address global competency or global citizenship. Notably, the CAPHIA Foundation Competencies are under review, and we anticipate that future iterations will incorporate global competency/citizenship, along with critical reflective practice. As public health professionals, it is crucial to be relational and reflective practitioners [14,15,16], extending care beyond individuals to include broader considerations, such as populations, societies, technologies and environments [17,18,19].

Importance of Critical Reflective Practice

Critical reflection is widely recognised across various sectors as a key method for developing analytical and thoughtful approaches to practice, and public health is no exception [20]. In the context of public health and health promotion, critical reflection has been defined as “a continual process of assessing and challenging the underlying beliefs, values, assumptions, discourses and approaches to health promotion practice from the individual to the population level” with the goal of promoting greater empowerment, equity, self-efficacy and access for marginalised and vulnerable populations, while also challenging structural health inequities [21] (p. 217). More recently, self-learning and critical reflective practice are also noted by the World Health Organization [22] as key competencies contributing to global competence among those employed in the public health workforce.

SoTL research has shown how students’ reflective learning can evolve from surface-level reflections to deeper engagement when guided by structured prompts [16,19]. This progression can lead to transformative experiences, highlighting the value of reflective frameworks that push students to move beyond basic descriptions, connect theory with personal experience and challenge their assumptions. Teng et al. [16] suggest that such an approach is especially beneficial for undergraduates with limited work experience, as it fosters higher order thinking and establishes a strong foundation for future professional engagement.

In a study that identified key themes in students’ reflections, McKay and Dunn [23] observed that, by combining field visits with classroom content (i.e., learning then applying content through practical activities) students began to understand potential career paths and how they could achieve their goals. So, while their initial reflections lacked depth, positive outcomes were still possible through reflection and prompting.

However, despite these positive findings, it is common for students to overlook the importance of reflective practice for future employment or career development [24,25]. In our recent practitioner reflection [19], we observed that students often provided shallow reflections lacking holistic framing and scholarly support. To address this, we drew on Strampel’s [26] framework, which emphasises the necessity of reasoning, reconstruction through multiple viewpoints, and forward action planning to achieve transformative outcomes, and used visual media with the relational employability framework to encourage engagement with critical reflection and career concepts [19].

In this way, we have witnessed the value of framing critical reflection in student assessments as both a learning activity and a lifelong skill [19,27]. Developing critical reflection as a competency is particularly crucial in public health, as it contributes to global competency and citizenship [8]. In this paper, we further explore how the relational employability framework, integrated into an undergraduate research unit through critical reflective practice, can support the development of critical global citizenship among students and graduates of the Bachelor of Health Science degree at ECU.

Conceptual Framework

The relational employability framework [4], developed and validated by Cook [2,3], building on the work of Lacković [28], is underpinned by two interconnected concepts. The first is relational higher education [29], which emphasises cultivating relational awareness, relational agency and identity+ (or multimodal identity, as an expansion of professional identity). Relational higher education highlights the connections that shape education and its impact through three dimensions of knowledge in the curriculum: human society; the environment/more-than-humans; and digitalisation [29].

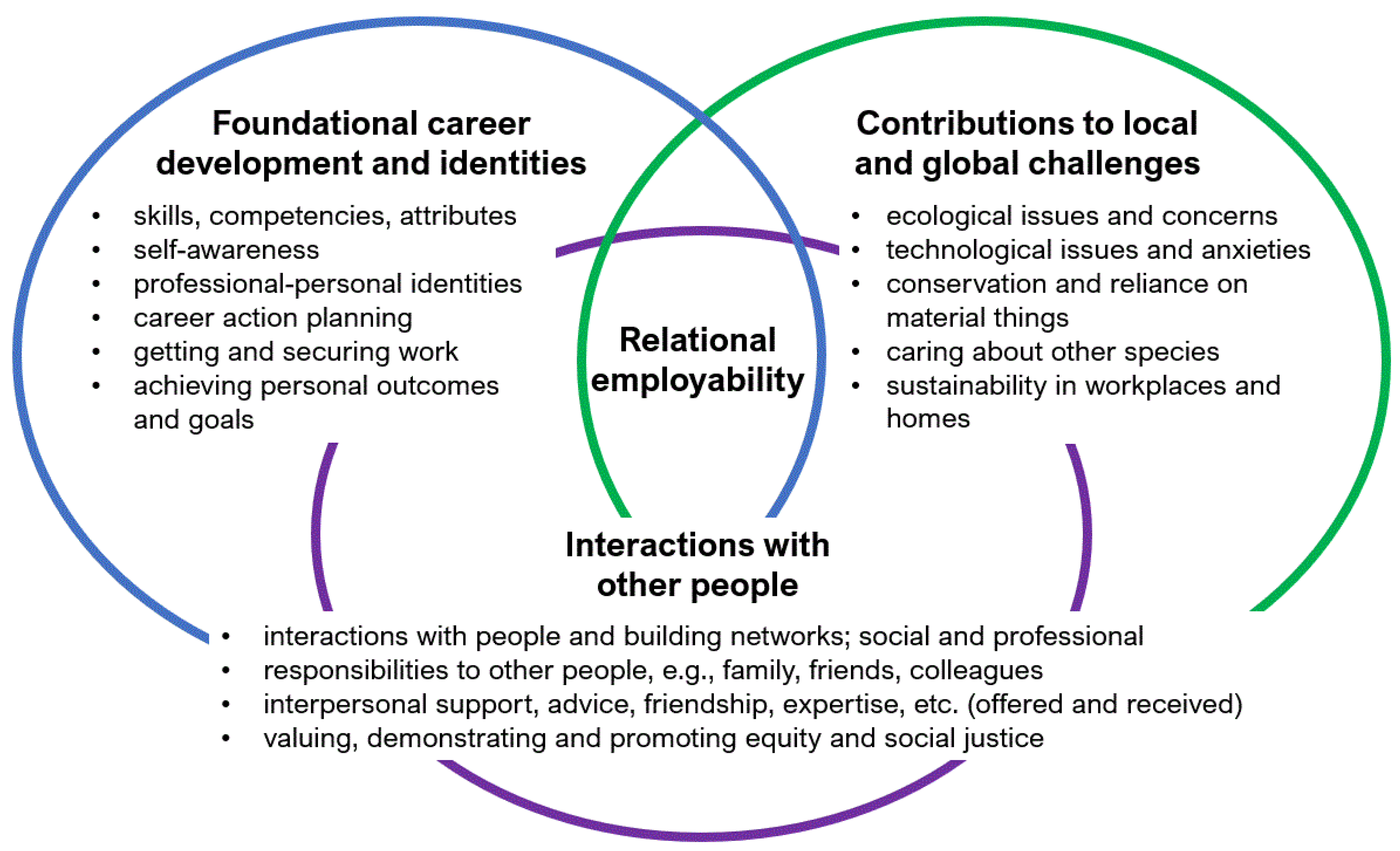

The second concept underpinning relational employability is a relational graduate employability paradigm [28], which comprises three integrated meta-layers: relational recruitability; socio-emotional relationality; and eco-technological relationality. In her doctoral thesis project, Cook [2] merged, developed and simplified these two concepts to form relational employability (Figure 1), which was subsequently tested with academics and students at ECU. Wallace et al. [19] have reflected on the benefits of relational employability for educators and students, particularly when used to encourage critical reflective practice. They and Cook [2,3] posit that the framework offers a meaningful and arguably future-proof expansion of traditional employability ideas and practices through a shift toward relationality.

The framework (Figure 1) comprises three equally important and interconnected components, with the idea being that individuals work toward developing each component as each is crucial in our relational world and, thus, throughout careers. The first component of the relational employability framework pertains to the skills and outcomes one develops throughout their career. These are the decisions and actions taken to benefit the present and future self. This component encompasses self-reflection, career planning, taking steps to understand and strengthen personal and professional identities, and developing skills, such as teamwork, career management and strategies to secure and maintain employment.

The second component concerns how we interact, behave and contribute to the needs of other people, and how we demonstrate and promote equity and social justice to support and empower others by being global citizens.

The third component focuses on the interactions and contributions we can make, both collectively and individually, toward local and global challenges through two key aspects: environments and other species (ecologies); and technologies (sociomaterial and digital). These aspects are important in any learning and employability development as they help raise awareness of humanity’s reliance of ecologies and technologies throughout careers, now and into the future. Humans rely on a healthy ecosystem and technologies, in addition to their own health and wellbeing. Without being aware of these aspects throughout our careers (lives and workforce), we will not flourish, nor assure our ongoing employability in a changing world.

As explained by Cook [2,3], relational employability supports a paradigm shift in higher education toward relationality [28,29], challenging narrow and individualistic ideas, thoughts, behaviours and actions. In doing so, it supports the principles of global citizenship education [30] (see Target 4.7 of the Sustainable Development Goals) [31]. Global citizenship emphasises skills such as critical thinking, justice-oriented agency, ethical reasoning and social responsibility in addressing complex challenges within our interconnected and digitised world [32]. Also known as critical global citizenship, the concept highlights the importance of nurturing one’s capacity to navigate and contribute meaningfully to society and more-than-human elements [2]. Thus, critical global citizenship can be considered as an outcome of embodying relational employability.

According to Hill et al. [32], critical global citizenship can be achieved through transformative learning and reflection. Lilley et al. [33] contend that global citizen learning (the process of becoming a global citizen) occurs when students are encouraged to step out of their comfort zone, think differently, engage beyond their immediate social environment, and consider “self, life, others, and career, and the world beyond narrow expectations” (p. 241). Relational employability does this by challenging individuals to consider their wider interactions, contributions and possibilities with other humans and more-than-humans throughout their careers.

Used as a teaching-learning and assessment tool, the relational employability framework can enable educators and encourage students to consider their interactions, contributions and potentials in partnership with other humans and more-than-human entities (i.e., other non-human species, environments, materials and technologies) throughout learning and career experiences [2]. This encourages students to reflect on their interconnectedness and relational becoming as critical global citizens [2]. More specifically, relational employability can help students to identify and understand the connections between their developing disciplinary knowledge, skills, employability and professional identities through activities such as critical reflection and dialogue. Such learning can enable students to practice critiquing their (and others’) assumptions, behaviours and actions, which, as future public health professionals, they will hopefully embody and promote throughout their careers [34]. According to Cook [2], by engaging with the triadic dimensions of relational employability, practitioners (including graduates and educators) can enhance their ability to address challenges from diverse perspectives. This engagement fosters the development of creative thinking and problem-solving skills [2], which are among the six essential employability skills identified by Dickerson et al. [35] as crucial for success in the workforce, both historically and in the future.

Having established the theoretical foundation and the significance of relational employability in fostering critical global citizenship, we now turn to the empirical aspects of our research. The following section outlines the materials and methods employed to explore how the relational employability framework supports the development of critical global citizenship among students and graduates of the Bachelor of Health Science degree at ECU.

Materials and Methods

This research employs a qualitative interview research methodology, utilising the findings from two case studies conducted over two consecutive years. Both case studies examined data from a unit of study taught at ECU in Perth, Western Australia, called Health Research Project, which serves as a capstone unit in the undergraduate Bachelor of Health Science degree. Most students undertake the unit in their final semester before graduation, then seek employment or continue onto postgraduate study. The unit includes assessments that ask students to critically reflect on the research process and their employability skills development in the unit.

Case Studies Overview

Studies Overview (Table 1), case Study 1 was part of Cook’s [2] doctoral thesis project and provided student perspectives on the use of the relational employability framework in the unit. Case Study 2, a School-funded teaching-learning project, aimed to capture graduate perspectives regarding the unit to inform its continual improvement and development. Notably, the focus of Case Study 2 was not relational employability, but the concept was mentioned by graduates, without prompting by the interviewer.

Reflective Practice and Framework Introduction

Prior to the introduction of the relational employability framework in 2022, students completed a reflective assessment based on Rolfe’s model of ‘what’, ‘so what’, and ‘now what’ [36]. Typically, these reflections were superficial, with students demonstrating limited critical reflection and a lack of engagement with peer-reviewed literature [18]. Given the critical role of reflective practice in contemporary workplaces [26], the teaching team aimed to enhance student engagement and deepen reflective practice by introducing the relational employability framework and associated learning activities (Table 2). For our reflections on the unit redesign, see Wallace et al. [18].

ECU Context and Unit Demographics

At ECU, approximately 6% of the university’s domestic undergraduates are from low socioeconomic status postcodes, 14% are from regional or remote locations, 47% are the first in their family to attend university and 24% study part-time. Of the total undergraduate student population, 13% are international, 44% mature aged and 56% study at least one unit online. In the Health Research Project unit, the typical student is female (82%), mature-aged (55%) and domestic (95%).

Case Study 1 Participant Demographics

In Case Study 1, out of a class of 56 students, two mature-aged students studying online were interviewed from the unit. These students, who had experienced relational employability in the unit, were aged 45 (male, domestic) and 29 (female, international onshore). The female student was later interviewed, as a graduate (no. 6), in Case Study 2.

Case Study 2 Participant Demographics

Table 3 details the demographic characteristics of the 13 graduates interviewed in Case Study 2. The rows shaded in grey indicate those who had experienced relational employability in the unit, as students.

Data Collection and Analysis Procedure

Interviews from both case studies were conducted by a research assistant using Microsoft Teams, which provides a transcript. The transcripts were deidentified and prepared for analysis by the research assistant. Data from both case studies were analysed in NVivo14 by Cook and Wallace using the process of codebook thematic analysis [37]. Each case study had its own codebook for coding the data as guided by the interview questions. Cook and Wallace collaborated to develop the codebooks for this research. The analysis procedure also involved a rigorous quality check conducted by Doherty to ensure consistency and reliability across the studies, with the team paying close attention to Ahmed’s [38] strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research. The final stage of analysis involved the integration of the data from both studies into the themes global citizenship, research skills development and critical thinking; the results of which are provided next.

Results

Global Citizenship

In Case Study 1, the concept of global citizenship was a focal point in the interviews, with students reflecting on their roles and responsibilities within a global context. The female student articulated the necessity of having a purpose beyond mere academic and professional achievements:

“I think when I [was] faced with this model, I just thought most of the students or most of the humans are lost in this world. They lost between what is their goals and they are not familiar with these concepts that they should have purpose for their study and their life.”

Both students emphasised the importance of understanding and addressing global issues. The female student highlighted the need to recognise and respond to broader societal challenges, such as mental health issues exacerbated by cultural and social pressures:

“In Australia, I can see high levels of depression and mental health issues because people can’t really; people are not in touch with their emotions and what they think, and emotions of others even.”

The male student acknowledged the value of engaging with diverse perspectives, suggesting that earlier exposure to global competency frameworks, like relational employability, could significantly benefit students: “I think maybe what might be helpful is if you introduce it earlier to some newer students ... You can see how that helps. Because I think the theory behind it is really special.”

These reflections underscore the importance of integrating global citizenship education into the curriculum to foster a deeper understanding of and engagement with both local and global issues.

In Case Study 2, graduates demonstrated an understanding of the value of global citizenship, particularly in fostering connections where people learn from each other, share knowledge and resources, and contribute to a community. Graduates also discussed empowerment and how global competency can impact individuals and communities by building capacity and helping people to ‘help themselves’. They highlighted that values such as being non-judgmental, inclusive, environmentally conscious, open and respectful are essential aspects of global citizenship. One graduate emphasised the importance of seeing the ‘big picture’ and contributing to ‘meaningful work’:

“It’s very valuable, I think. You need to be able to see the bigger picture. I think some people get on a topic and they stick to that topic and it might be really good, but if it’s not transferable or relatable to…the communities great or good, then it’s not really any benefit to anyone.” (G7)

Graduates addressed specific constructs of global citizenship, such as using critical thinking skills, to examine local, global and culturally significant or sensitive issues. They presented differing perspectives, from understanding the ‘big picture’ to starting globally and ‘funnelling down’ this broad knowledge to apply it at a local level:

“Overall, with the project…we do wanna improve food systems across WA, but we are gonna be using what has been learnt and done in other countries to do that. So that interlinks the global and the local perspective and trying to include everyone because we understand that, although they’re local, contextualised issues, everyone’s affected by food system problems.” (G1)

Graduates demonstrated a strong connection with the construct of ‘engaging with different perspectives and worldviews’, reporting that it supports growth and knowledge, and adds ‘massive value’ in terms of learning from each other. They also stressed the importance of engaging with diverse individuals, teams, communities and partners without judgement. One participant noted: “our workforce is very diverse and come from different backgrounds…it’s been like respecting their cultures and being curious and learning about…them and their culture.” (G12)

Inclusivity in the present was deemed essential to “right the wrongs of the past” that have led to the injustices and inequities experienced by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of Australia. One graduate noted the benefits and importance of professional learning in cultural competence and inclusivity to foster positive change.

Regarding respectful dialogue, graduates emphasised the need to “build trust”, especially with marginalised groups, before engaging with them. Open and effective interactions are necessary when discussing sensitive topics such as food insecurity. One participant in a supervisory role talked of engaging in respectful dialogue through “coaching” rather than “policing”:

“I don’t think that I’d be a very effective safety advisor if I was quick to judge people or was very closed and did not have effective interactions and that if I wasn’t inclusive or environmentally conscious like I just feel like, without those values or being a global citizen, I would be bad at my job essentially.” (G5)

Finally, the idea of ‘helping to build a more just, peaceful, inclusive and environmentally sustainable workplace/world’ resonated with these graduates. They discussed broad outcomes, such as improving food systems in Western Australia through empowerment – helping people and communities to strengthen and build on what they are already doing – and implementing and evaluating environmentally sustainable practices in their workplaces. Graduates noted their motivation for studying health science was to help achieve basic human rights, such as food security:

“I think I did this particular degree [health science] because I’ve just always wanted to help people. I wanted to do any kind of degree that meant that I was like having an immediate impact on someone’s life, for the better. So, I guess, for me, it’s fulfilling what I want to do as a career, as a job. But it’s kind of on just the slightly larger scale cause it’s more for community versus an individual.” (G1)

Using evidence to inform practice was a strong theme among graduates, both during the unit and in their professional roles. One graduate working in Occupational Health and Safety described:

“I am able to analyse information properly and that kind of thing, especially, which I do for work now, often read different journal articles and things that people come up with.” (G8)

Other graduates, working for non-government agencies supporting women’s health noted:

“I just have a very systematic and scientific approach to [developing resources, presentations and other materials], by observing this situation, observing the case and designing [an] intervention in a sustainable way.” (G6)

“I constantly have to know the latest research. Latest stats. Latest name changes ... knowing the latest information around women’s health all the time. So, if, for every presentation, I go out, I would check the latest stuff to make sure I’m telling … the best, giving back to practice the best latest evidence.” (G11)

Research Skills Development

In Case Study 1, the development of research skills was a critical focus in the students’ experiences. The female student discussed how the relational employability framework helped her to identify and address gaps in her digital literacy for research:

“One of my weakest areas was digital literacy. It is always a source of stress for me. But when I studied this model online, OK, this is the gap! So, I need to take action, and fill the gap, and it was really interesting, and it helped me.”

The male student also reflected on how engaging with the framework reinforced his research interests and skills: “It made me think more about ... working with organisational psychologists ... [to inform my practice].”

These insights highlight the framework’s role in enhancing students’ research skills, making them more adept at identifying areas for improvement and applying research methodologies effectively.

In Case Study 2, graduates reported on the key skills they believed they learned whilst completing the unit and those they perceived to have ‘honed on the job’ once employed. Strong themes included understanding the ethics application process and its importance, an appreciation of the research process from start to finish, and the importance of using evidence to inform practice.

Graduates noted that learning about the ethics application process was beneficial in their employment and for future study:

“We went through the whole ethics application. So, when I recently did my ethics application [at work], I already had an understanding. And then we got it back with like two comments, which was so good … So, it was good having that background knowledge.” (G7)

Others referred to the ethics approval document as a useful ‘roadmap’ for the research they were working on in their employment, noting the importance of ethics amendments for variations in the project:

“I feel like the opportunity to do the ethics application was massive for me because that had already been done on the project before I came into the team and just understanding how research has to always align with ethics was so helpful because…when you’re working on a project, you could take it in different ways…when we were questioning things like ‘what approach do we take for this’? We always had to come back to what is stipulated in the ethics. There’s been some variations [to ethics] … when we’ve wanted to … include stakeholders that we hadn’t originally wanted in the focus groups, there’s had to be ethics amendments.” (G1)

Graduates also found value in conducting a research project from start to finish, appreciating the lessons they learned. G4, who went on to complete an Honours degree and work as a research assistant, noted:

“It provided that sort of foundation … a good starting point for understanding research and … the concept of sort of framing up a project from the idea to then thinking about how you're gonna collect the data and analyse the data”.

Other graduates honed these skills further, gaining a deeper appreciation of the process and potential outputs once engaged in a research position:

“Understanding of the importance of research. And then also the start to finish … like how long it takes from the initial idea, to getting the EOI, to getting the ethics, actually running it, then collecting the data and then analysing it. And I’ve been on a paper since, so I got to see that side of it as well.” (G7)

This appreciation of the research process extended beyond graduates working or studying in research. G6, now employed as a nutrition/health promotion educator for a community organisation supporting migrant women, stated: “It gives me discipline, a structure and knowing the essence of research”. G5 concurred, noting:

“Applying the knowledge that I’ve learned through my degree, but then also the research skills that are within that. So, being able to take a body of information and then use that [to] create what it needs to look like for the business and then deliver it” [in relation to policy/procedures in a Work Health and Safety setting].

Critical Reflection

In Case Study 1, critical reflective practice was a recurring theme, with students recognising its significance in both personal and professional development. The male student emphasised the necessity of reflection in understanding and improving oneself, stating:

“For me initially it took a little bit of reflection to work out what it was ... But when I started to look into it and the engagement that you had with each session, I was like, OK, well from a learning point of view, there’s always something to improve on.”

The female student echoed this sentiment, describing how reflective practice helped her understand and navigate her emotions and those of others: “It gave what it’s really like in practice [with respect to] emotional awareness.” She highlighted the role of images in deepening the reflective process, noting that “being visual is one of the best ways to present [your thoughts].” This student elaborated on how the use of images in the unit facilitated her critical reflection, allowing her to express and explore complex emotions and ideas more vividly. She remarked that the visual component of the assignment was integral to her reflection process, stating, “The visual part to this assignment was actually part of what reflects us as a human being. When you shared your artwork [image-reflections], it gave us the idea that we could have our own images like this.”

Moreover, she described how these images allowed her to externalise and communicate internal thoughts and feelings that might otherwise remain unexpressed:

“I always have the picture of [a mountain] in front of me for each unit, each assignment ... When you share the photos, I said, ‘Oh, it is the first time I can share what I see in front of my eyes [that] other people can’t see!’” This reflection demonstrates the power of visual elements in fostering a more profound connection between internal experiences and external expression.

The female student further reflected on the innovative nature of integrating art into reflective practice, comparing the visual tools to a camera lens that brought her thoughts into sharper focus: “It was like a camera lens. So first I saw it in the beginning of the semester but when I immersed myself, it was like it took a picture and brought it [into focus] to look at the details.” She highlighted the importance of art in education, advocating for its broader application in learning processes: “Art is most important to improve the students ... [It] should be part of our life every day.”

These reflections illustrate how critical reflective practice, supported by visual and artistic elements, can lead to a deeper understanding of oneself and enhance interpersonal skills—crucial components for professional growth, particularly in the field of public health. The integration of images into reflective practice not only facilitated the students’ engagement with the material but also helped them to articulate and navigate their complex emotional and intellectual landscapes.

In Case Study 2, graduates who undertook the unit in 2020 or 2021 completed an assessment task whereby they reflected on their employability skills in relation to the research process, using Rolfe’s [36] reflective model of ‘what, so what and now what’. Those who completed the unit in 2022 or 2023 used the relational employability framework for this assessment, with the addition of innovative visual and multimodal teaching practices to facilitate creative exploration and reflection on relational employability and identities beyond themselves.

Some graduates who used Rolfe’s [36] reflective framework reported they had never practiced reflective practice in their professional roles since graduating, did not understand what the assessment required of them and found it to be “one of the hardest things I’ve actually had to do” (G4) because it was a change from the academic writing style they were accustomed to. In contrast, graduates who engaged with the relational employability framework using images reported using the skills they had learned to reflect on some focus groups they had facilitated, to build a resume and to focus on relationship building: “We’ve had to reflect on previous and current implementation of safety [policies and procedures] so we can continue to improve and establish good relationships.” (G5)

Other graduates suggested alternative ways of presenting reflections, such as using audio or a series of images to represent a ‘reflective journey’. Those graduates who engaged with the relational employability framework using images saw its relevance and applicability to their professional lives, especially when considering value-based decisions:

“I think the unit helped [me] understand that, while you need to fit a job, that the job also has to fit you. I think we lose sight of that a lot … if you don’t know yourself, or if you don’t have a look at the skills and what the job is requiring. As much as that you can try and fit the job to yourself, it might not fit you, and that it’s okay to turn down a job based on the value aspect. I think it’s a really important thing. Cause if it doesn’t align with your values, it’s not gonna make you wanna do your job well.” (G5)

Through reflection, the relational employability framework also seemed to improve the students’ and graduates’ confidence. For example, in Case Study 1, the female student described how the framework helped her recognise and build on her strengths:

“This model showed the dynamism of the complexity of the skills required for employability. When I say dynamics then of the skills for me it means that as a student or future employee or citizen of the world, we need constantly to learn and progress and there is no destination. It is the path or journey that sometimes we take rest.”

The male student similarly found that the framework encouraged him to reassess his skills and goals, thereby boosting his confidence: “For me, it actually reinvented the reason why I was doing the degree in the first place.”

These narratives demonstrate that the framework not only aids in skill development but also fosters a sense of confidence and purpose among students, preparing them for future challenges.

Confidence is also an important part of one’s professional identity development. In Case Study 2, many graduates talked of their increased confidence in delivering presentations, communicating with diverse groups, working comfortably with others at higher levels of authority and engaging with graduates and partners due to having completed the unit and then continuing to practice those skills at work. G11 explained:

“Being in the workforce is just … it increases your confidence daily, it increases your… you’ve got the skills. You don’t always have to use the skills, but you’ve got the skills. You understand how you know”.

In the next section, we synthesise the results to articulate how the student becomes the graduate who is globally competent through engagement with the relational employability framework.

Discussion

This paper aimed to demonstrate the benefits of utilising the relational employability framework with public health undergraduate students, particularly to foster critical global citizenship. The following discussion section explores how critical global citizenship is cultivated through the framework, emphasising the transition from student to graduate and the embodiment of relational employability in public health practice.

Relational Employability and Global Competence

The relational employability framework [4] integrates three key components: foundational career development and identities; interactions with other people; and contributions to local and global challenges. Our study revealed that engaging with this framework, through critical reflection and using images, helped students and graduates to develop a deeper sense of global competence. Students reported enhanced understandings of their learning needs and empathy, both of which are essential competencies in public health practice [8]. For instance, in Case Study 1, the male student’s reflection on the importance of understanding and improving oneself through continual learning – “There’s always something to improve on” – highlights the framework’s emphasis on self-reflection for personal and professional growth, aligning with the work of Teng et al. [16].

Graduates’ perspectives further illustrate how the relational employability framework fosters global competence. The notion of ‘coaching not policing’ in a professional context highlights the importance of respectful and effective cross-cultural interactions, which are crucial in public health practice [39]. This approach, emphasised by a graduate, shows the practical application of global competence in the workplace, where inclusivity and cultural sensitivity are paramount [8]. Graduates’ desires to help people and make a difference in society reflects the framework’s focus on contributing to local and global challenges and aligns with Stoner et al.’s [8] argument that “one must place themselves within the broader/global context to begin to truly understand the health implications of personal choices” (p. 126). For example, one graduate noted, “I did this particular degree because I’ve just always wanted to help people”. Such altruistic motivation is a fundamental aspect of critical global citizenship, where the goal extends beyond personal success toward societal impact.

Research Skills Development

Although field visits were not part of the unit as in McKay and Dunn [23], our study engaged students in conducting real research, providing them with valuable insights into the research process and the role of a researcher, thus supporting their career development.

We showed that integrating research skills within the relational employability framework (as a key employability skill) was not only possible but worked well and encouraged students to identify and address their knowledge gaps, which is important in public health practice [12]. For example, the female student in Case Study 1 realising she needed to improve her digital literacy highlights the framework’s role in fostering a research-oriented mindset and a proactive approach to learning. Graduates reported benefits from learning about the ethics application process and conducting comprehensive research projects, which provided a solid foundation for their professional roles. They could see how the integration of research skills development in the unit enabled them to contribute good workplace practices.

Continuous engagement with research methodologies and evidence-based practices, as facilitated by the relational employability framework, can enhance analytical and critical thinking skills, which are vital for addressing complex health issues [1,13,20,21]. As students and graduates navigate careers, their ability to apply rigorous research methods and critique information positions them as effective and informed public health professionals.

Critical Reflective Practice

Critical reflective practice is integral to the relational employability framework, enabling students and graduates to develop self-awareness, adaptability and a deeper understanding of their multiple identities. For example, the female student’s insight into her emotional awareness emphasises the value of reflective practice for developing interpersonal skills. Graduates who learned about the relational employability framework using images and then reflected in the assessment reported applying critical reflection in various professional contexts, from facilitating focus groups to building effective relationships. These findings demonstrate that the relational employability framework, supported by visual imagery, enabled students to critically reflect during their studies and apply this skill as professionals. Therefore, building on Tretheway et al.’s [21] recommendation for critical reflection to be embedded in CAPHIA’s Competencies [13], and the WHO’s [22] global competency framework calling for critical reflective practice as a key competency for the public health workforce, our study suggests the relational employability framework could be used to support the achievement of this competency to assure ethical and responsible practices throughout the public health sector.

The framework’s emphasis on reflection aids key competency development and builds confidence. Both students and graduates noted increased confidence in their abilities, attributing this to the structured approach to self-assessment and continuous improvement they experienced during the unit through our relational employability approach. This confidence is crucial for public health professionals who must navigate complex and dynamic environments to deliver effective solutions in social and community settings [40]. By fostering a reflective mindset, the relational employability framework prepares students and graduates to critically evaluate their experiences and make informed, value-based decisions in their professional practice. In line with Teng et al. [16], our study highlights the value of integrating structured reflective learning components, such as the relational employability framework, early in the curriculum to support students’ development of critical thinking and facilitate a deeper understanding of their practical experiences, thus better preparing them for future professional challenges.

Implications for Teaching, Research, and Professional Practice

The findings of this study have significant implications for teaching, research and professional practice. Integrating the relational employability framework into public health curricula can enhance global competence, research skills and reflective practice, preparing students for the multifaceted challenges of public health [1,5]. Educators should consider adopting the relational employability framework to foster holistic and interdisciplinary learning and reflective practices among future public health professionals.

For research, the relational employability framework emphasises the importance of ethical standards and evidence-based practice, reinforcing the need for comprehensive research training in public health programs [1]. Professional practice benefits from graduates who are not only skilled researchers but also empathetic and reflective practitioners, capable of making meaningful contributions to local and global health. Thus, the relational employability framework effectively cultivates critical global citizenship by bridging the gap between academic learning and professional practice [12]. Through integrated self-reflection activities that support the development of global competency and research skills, the framework prepares students and graduates to become informed, reflective and impactful public health professionals.

Strengths and Limitations of this Research

This research has been conducted with attention to trustworthiness and dependability, providing thick, contextualised descriptions and explicit documentation of our methodology [38]. Reflexivity, as demonstrated in our published paper [18], has also played a key role in ensuring the accuracy of our findings as “self-awareness contributes to minimizing potential distortions in the findings” [38] (p. 2). The triangulation of students’ and graduates’ perspectives across the two studies supports the credibility of this research [38]. Peer-debriefing strengthened the confirmability of the findings, increasing their objectivity and accuracy [38]. Additionally, potential power dynamics between students/gradates and teaching staff were mitigated by engaging a research assistant to conduct the interviews.

However, this research is limited by the inherent subjectivity and bias of qualitative methods, which included only those students and graduates who chose to participate. As a result, the views potentially disengaged or dissatisfied individuals were not captured, possibly skewing the findings.

Conclusions

This paper has demonstrated the benefits of using the relational employability framework in teaching-learning contexts for public health students and graduates, emphasising the development of critical global citizenship as a key competency. By integrating self-reflection, global competence and research skills, this framework supports smoother transitions from academia to professional practice.

We recommend the adoption of a relational employability approach as an essential strategy for preparing students and graduates for the workforce, particularly in public health education. This approach equips graduates with the research skills necessary to critique and apply knowledge while fostering a reflective and empathetic mindset crucial for addressing public health challenges.

We advocate for the wider adoption of relational employability across higher education. Practical recommendations for enabling curriculum transformation include incorporating structured reflective practices, using visual and multimodal media in teaching-learning, promoting interdisciplinary learning and embedding ethical research training in degrees.

Professionals, especially those in the medical and health sciences, must possess robust research skills and embody relational employability mindsets to contribute as global citizens, capable of making meaningful and impactful contributions to public health.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the undergraduate students and graduates from Health Research Project who freely gave their time in support of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Luu, X.; Dundas, K.; James, E.L. Opportunities and Challenges for Undergraduate Public Health Education in Australia and New Zealand. Pedag. Health Promot. 2019, 5(3), 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, E.J. "For Me It's Like Oxygen": Using Design Research to Develop and Test a Relational Employability Framework. Doctoral Thesis, Lancaster University, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Cook, E.J. A Narrative Review of Graduate Employability Models: Their Paradigms, and Relationships to Teaching and Curricula. J. Teach. Learn. Grad. Employab. 2022, 13(1), 37–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, E.J. Relational Employability Teaching-Learning Framework; Edith Cowan University: Perth, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edemekong, P.F.; Tenny, S. Public Health. StatPearls [Internet]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470250/ (accessed on August 11, 2024).

- Marmot, M.; Allen, J. Social Determinants of Health Equity. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104(S4), S517–S519. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4151898/.

- Baum, F. The New Public Health; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; ISBN 9780195588088. [Google Scholar]

- Stoner, L.; Perry, L.; Wadsworth, D.; Stoner, K.R.; Tarrant, M.A. Global Citizenship Is Key to Securing Global Health: The Role of Higher Education. Prev. Med. 2014, 64, 126–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Global Citizenship. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/academic-impact/global-citizenship (accessed on August 11, 2024).

- Directorate for Education and Skills, OECD. PISA: Preparing Our Youth for an Inclusive and Sustainable World: The OECD PISA Global Competence Framework; OECD: Paris, France, 2018. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/topics/policy-sub-issues/global-competence/Handbook-PISA-2018-Global-Competence.pdf (accessed on August 11, 2024).

- World Federation of Public Health Associations (WFPHA). The Global Charter for the Public's Health; WFPHA: Geneva, Switzerland, n.d. Available online: https://www.wfpha.org/document-upload/the-global-charter-for-the-public%E2%80%99s-health.pdf (accessed on August 11, 2024).

- Hamelin, A.M.; Paradis, G. Population Health Intervention Research Training: The Value of Public Health Internships and Mentorship. Public Health Rev. 2018, 39, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Council of Public Health Academic Institutions (CAPHIA). Foundation Competencies for Public Health Graduates in Australia; CAPHIA: Australia, 2016; Available online: https://caphia.com.au/competencies/ (accessed on August 11, 2024).

- Issitt, M. Reflecting on Reflective Practice for Professional Education and Development in Health Promotion. Health Educ. J. 2003, 62(2), 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, K.; Gordon, J.; MacLeod, A. Reflection and Reflective Practice in Health Professions Education: A Systematic Review. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2009, 14, 595–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.W.C.; Lim, R.B.T.; Tan, C.G.L. A Qualitative Analysis of Student Reflections on Public Health Internships. Educ. Train. 2024, 66(10), 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dove, E.S.; Kelly, S.E.; Lucivero, F.; Machirori, M.; Dheensa, S.; Prainsack, B. Beyond Individualism: Is There a Place for Relational Autonomy in Clinical Practice and Research? Clin. Ethics 2017, 12(3), 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickman, A.C.; Shelley, K.; Rutherford, Z.; Gardiner, P.A.; Buckley, L.; Lawler, S. Using Innovative Curriculum Design and Pedagogy to Create Reflective and Adaptive Health Promotion Practitioners Within the Context of a Master of Public Health Degree. In International Handbook of Teaching and Learning in Health Promotion; Akerman, M., Germani, A.C.C.G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 467–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, R.; Doherty, S.; Cook, E.J. Using Image-Reflections to Support Undergraduate Students’ Relational Employability: A Practitioner Reflection. J. Teach. Learn. Grad. Employab. 2024, in press.

- Morley, C. How Does Critical Reflection Develop Possibilities for Emancipatory Change? An Example from an Empirical Research Project. Br. J. Soc. Work 2012, 42, 1513–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tretheway, R.; Taylor, J.; O’Hara, L.; Percival, N. A Missing Ethical Competency? A Review of Critical Reflection in Health Promotion. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2015, 26, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2024). Global competency and outcomes framework for the essential public health functions. Redhawk Publications.

- McKay, F.H.; Dunn, M. Student Reflections in a First Year Public Health and Health Promotion Unit. Reflective Pract. 2015, 16(2), 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffey, L.J.; de Leeuw, E.J.J.; Finnigan, G.A. Facilitating Students’ Reflective Practice in a Medical Course: Literature Review. Educ. Health 2012, 25(3), 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, A.E.; Joseph, A.S.; Umland, E.M. Student Perceptions of the Impact and Value of Incorporation of Reflective Writing Across a Pharmacy Curriculum. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2017, 9(5), 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strampel, K. Using Web 2.0 Technologies to Enhance Learning in Higher Education; Doctoral Thesis, Edith Cowan University: Perth, Australia, 2010; https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/2094/. [Google Scholar]

- Veine, S.; Kalvig Anderson, M.; Haugland Andersen, N.; Espenes, T.C.; Bredesen Søyland, T.; Wallin, P.; Reams, J. Reflection as a Core Student Learning Activity in Higher Education – Insights from Nearly Two Decades of Academic Development. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 2020, 25(2), 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacković, N. Graduate employability (GE) paradigm shift: Towards Greater Socioemotional and Eco-technological Relationalities of Graduates’ Futures. In Education and technological unemployment; Peters, M., Jandrić, P., Means A., Eds.; Springer, 2019; pp. 193–212. [CrossRef]

- Lacković, N.; Olteanu, A. Relational and Multimodal Higher Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Global Citizenship Education; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://en.unesco.org/themes/gced (accessed on August 11, 2024).

- UNESCO. Leading SDG 4 – Education 2030; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/education2030-sdg4 (accessed on August 11, 2024).

- Hill, A.; Salter, P.; Halbert, K. The Critical Global Citizen. In The Globalisation of Higher Education: Developing Internationalised Education Research and Practice; Hall, T., Gray, T., Downey, G., Singh, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilley, K.; Barker, M.; Harris, N. Exploring the Process of Global Citizen Learning and the Student Mind-Set. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2015, 19(3), 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, E.J. Relational Employability Stages of Development; Edith Cowan University: Perth, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, A.; Rossi, G.; Bocock, L.; Hillary, J.; Simcock, D. An Analysis of the Demand for Skills in the Labour Market in 2035; Working Paper, No. 3; National Foundation for Educational Research: Slough, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.nfer.ac.uk/an-analysis-of-the-demand-for-skills-in-the-labour-market-in-2035/ (accessed on August 11, 2024).

- Rolfe, G.; Freshwater, D.; Jasper, M. (Eds.) Critical Reflection for Nursing and the Helping Professions: A User’s Guide; Palgrave: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One Size Fits All? What Counts as Quality Practice in (Reflexive) Thematic Analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18(3), 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; The Pillars of Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2024. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2949916X24000045 (accessed on August 11, 2024).

- Coombe, L.; Severinsen, C.; Robinson, P. Practical Competencies for Public Health Education: A Global Analysis. Int. J. Public Health 2020, 65, 1159–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, K.M.; Keller, S. Exploring Workforce Confidence and Patient Experiences: A Quantitative Analysis. Patient Exp. J. 2018, 5(1), 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Cook’s Relational Employability Framework [4].

Figure 1.

Cook’s Relational Employability Framework [4].

Table 1.

Case Studies Overview.

| Case Study | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Broader research | PhD thesis project | Teaching-learning grant project |

| Ethics approval | Lancaster University Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee, executive review by ECU’s Research Ethics Team and written approval from key members of ECU leadership. | ECU Human Ethics Research Committee |

| Research focus | Student experiences and perspectives on the relational employability framework in the unit. | Graduate work experiences and perspectives on the unit, with a focus on global citizenship, research skills and critical reflection. |

| Types of questions asked in interviews |

|

|

| Years data collected | 2022 | 2020-2023 |

| No. of participants (whose views are included in this paper) | 2 | 13 |

| Data collection by | Cook | Cook |

| Data analysis by | Cook | Wallace |

| Quality check by | Doherty | |

Table 2.

Unit Activities for 2022 and 2023.

| Week | Activity |

|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction to the unit: Students reflect on their knowledge of research and employability in preparation for Week 2. |

| 2 | Relational employability presentation – introduction to the framework and associated learning activities. Explanatory slides provided to students. |

| 3 | Assessment three tipsheet introduced. |

| 4 | Educators’ image-reflections shared. |

| 5 | Preparation for the image-reflections activity. |

| 6 | Image-reflections activity: Students bring in/post a visual artefact with a short-written description representing their relational employability identity at that point in time. |

| 7-11 | Weekly reminders to reflect and make notes on the research process and employability. |

| 12 | Presentation – looking back through the unit – considering relational employability and the research process. |

| 13 | Assessment three reflections due. |

Table 3.

Case Study 2 Participant Demographics.

| Graduate No. | Age | Mode | Gender | Unit Year | Year Degree Completed | Major 1 | Major 2 | Job at the Time of the Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 37 | Online | Female | 2022 | 2023 | Nutrition | Health Promotion | Research Project Officer |

| 2 | 24 | On campus | Female | 2020 | 2021 | Nutrition | Health Promotion | Research Project Officer |

| 3 | 23 | On campus | Female | 2020 | 2020 | Nutrition Bioscience | Not Applicable | Research Assistant |

| 4 | 26 | On campus | Female | 2020 | 2020 | Nutrition | Health Promotion | Project Officer, Government |

| 5 | 22 | Online | Female | 2022 | 2023 | Occupational and Environmental Health and Safety | Not Applicable | Safety Advisor, Industry |

| 6 | 49 | Online | Female | 2022 | 2022 | Nutrition Bioscience | Not Applicable | Health Promotion Officer, Not for Profit |

| 7 | 26 | On campus | Female | 2021 | 2022 | Health Promotion | Not Applicable | Master by Research student |

| 8 | 22 | Online | Female | 2022 | 2022 | Health Promotion | Occupational Safety and Health | Education Assistant |

| 9 | 25 | On campus | Male | 2022 | 2022 | Health Promotion | Environmental Management | Health Promotion Officer, Government |

| 10 | 38 | On campus | Female | 2021 | 2021 | Nutrition | Health Promotion | Fitness Instructor |

| 11 | 50-55 | On campus | Female | 2020 | 2020 | Addiction Studies | Health Promotion | Program Support Officer |

| 12 | 31 | Online | Female | 2021 | 2021 | Nutrition | Occupational Safety and Health | Safety and Wellbeing Partner, Industry |

| 13 | 60 | Online | Male | 2021 | 2021 | Occupational Safety and Health | Not Applicable | Fire Station Officer, Government |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated