1. Introduction

Grounding resistance is one of the most important parameters determining the suitability of a protection installation. Its determination is an important issue and many studies have focused on it. Although it is possible to theoretically calculate its value provided the physical configuration and burial parameters are known [

1,

2,

3,

4], field measurement is a mandatory task. Among the various methods of measuring the earthing resistance of an operating electrode [

5], the well-known fall-of-potential method (FOPM) is one of the simplest and most effective. This method involves externally connecting the electrode to be measured to a current source and another auxiliary electrode located far away at a distance D, forming a circuit that closes as current passes through the ground from the electrode being measured to the distant auxiliary electrode, that is, a three-pin arrangement. The procedure is completed by measuring the potential difference between the electrode and an auxiliary probe driven into the ground at an appropriate distance

x from it. For a very specific value of this distance, around 0.618D, the ratio between the measured potential difference and the injected current provides the value of the grounding resistance of the electrode. This is known as the 62% rule [

6]. This is always satisfied provided that the electrode to be measured is small, D is very large, and

x is large enough so that from distance

x the electrode behaves like a point source of current at ground level [

7].

To measure extensive electrodes associated with large installations, the size of the electrodes presents a problem since it would be necessary to place the auxiliary potential probe at a considerable distance to meet the requirements of the 62% rule. Not to mention the auxiliary current electrode, which must be placed even farther away from the electrode, severely compromising the proper functioning of the circuit that closes through the ground loop. This would require a more intense current injection for the measurement method to work properly. Several attempts have been made to avoid the limitations of FOPM when it is not possible to move the auxiliary current electrode far enough away [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Some modifications of the FOPM have been proposed [

12,

13] and the effect of surrounding electrodes and other conductors on FOPM measurements have been studied [

14].

Currently, in the European context, the measurement of grounding resistance for large electrodes in electrical installations with alternating current voltages above 1 kV connected to transmission lines is carried out in accordance with the EN 50522 standard [

15]. According to this standard, it is necessary to inject current through the grounding system of a transmission line tower at the substation. The tower must be sufficiently distant so that both electrodes can be considered isolated. This will create a measurable potential rise in the ground at the electrode being tested, which can be used to evaluate the grounding resistance. Despite the apparent simplicity described, the procedure is complex and costly to execute, as it requires handling the transmission line used.

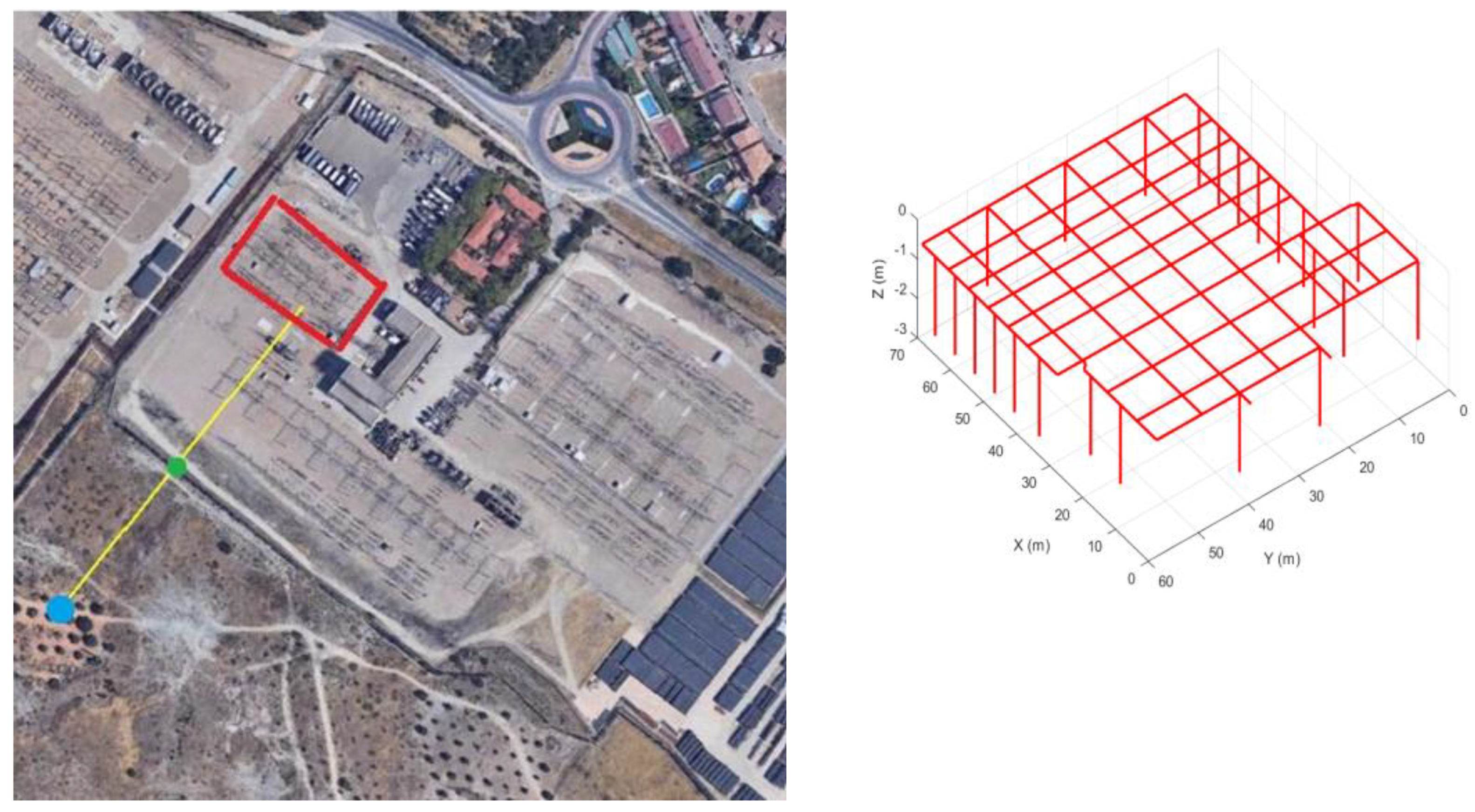

In this paper, a new modification of the classic FOPM is proposed, which is applicable to situations like those described above without requiring the potential probe to be placed far from the edge of an extensive grounding mesh. The only requirement to maintain is that the auxiliary current electrode remains as far away from the mesh as possible. Moreover, the farther this electrode is from the mesh, the better the measurements obtained. This is achieved by defining a correction factor that must be multiplied by the field measurement result of the resistance to obtain the correct grounding resistance value of the mesh. The correction factor depends on the nature of the grounding electrode and the theoretical potentials it generates around it through current injection. It can be considered a factory parameter of the electrode and can therefore be calculated theoretically. In the following sections, the correction factor will be defined and calculated through some simulated examples and applied to the determination of the grounding resistance of extensive electrodes. Some real cases will be presented and analyzed. Finally, the conclusions and recommendations will be detailed in the final section of this paper.

2. Theoretical Background

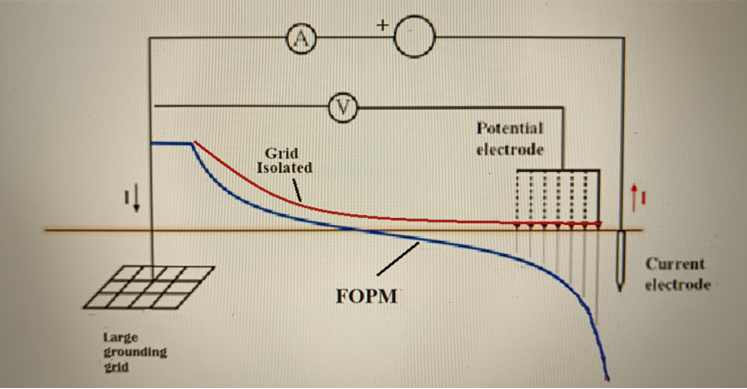

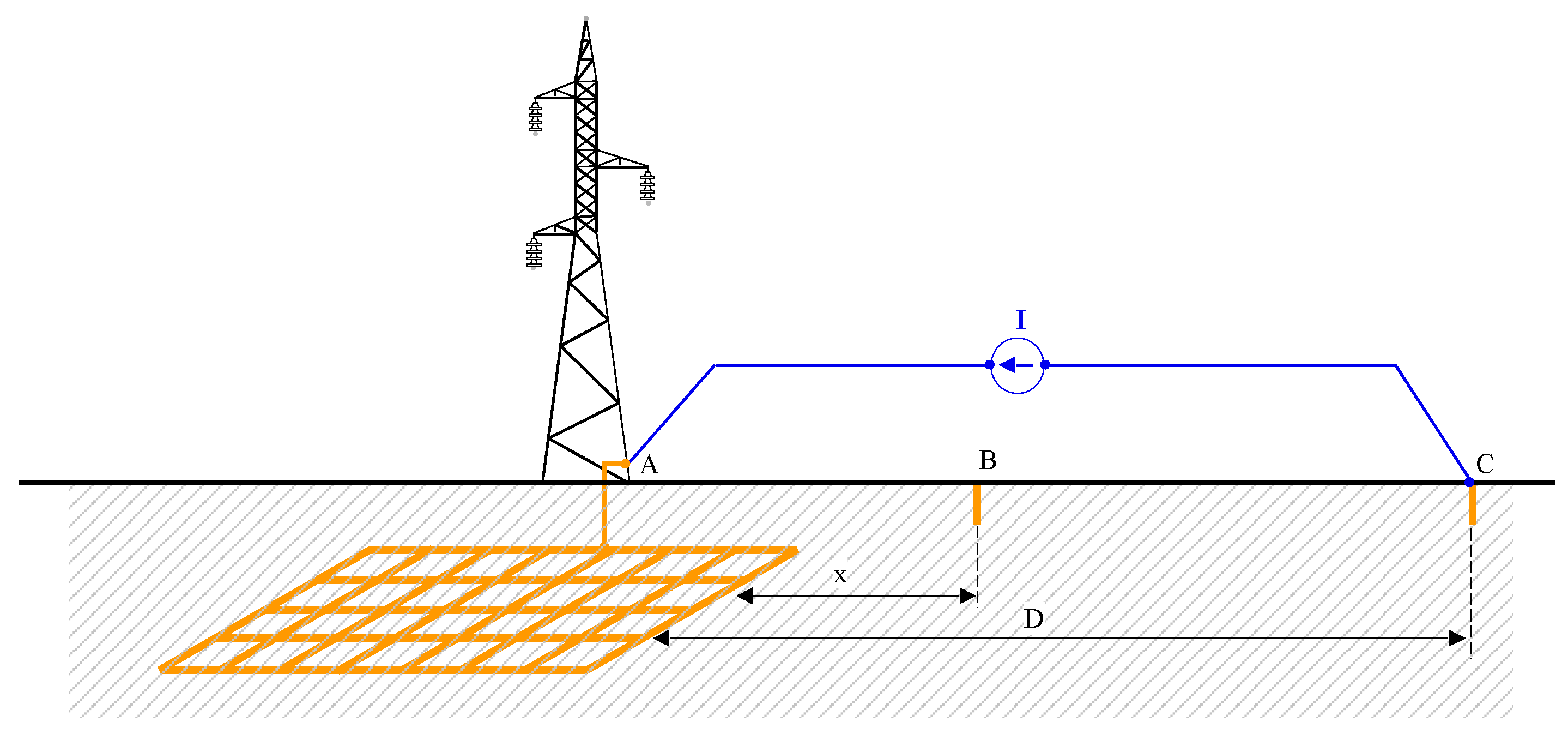

The three-pin method is represented in

Figure 1. The electrode to be measured is connected to a distant auxiliary electrode through a current source with intensity I.

The circuit is completed through the ground. The potential difference between points A and B is

In expression (1), is the potential of the electrode when it is isolated, i.e., the grounding potential. Additionally, it is implicitly assumed that at point x, both the grounding electrode and the auxiliary current electrode behave as point sources of current at ground level. The same applies to the auxiliary electrode with respect to point A. This question should be discussed in the case of long electrodes or not very large distances D.

Based on expression (1), the measured grounding resistance

is defined as

where

is the true grounding resistance. It is clear that

for any given value of x, provided that the quantity in brackets in (2)

is zero. Thus, solving for the value of x, it gives

, known as the 62% rule, provided that the assumptions mentioned above are satisfied. In summary, by placing the auxiliary electrode at a sufficiently distant location D from the grounding point, this rule can be applied to obtain values that are very close to the true grounding resistance.

It is evident that the analysis presented here cannot be applied when measuring an extensive electrode or also when the distance D is not large enough to ensure that the potential generated by the auxiliary current electrode on the electrode to be measured is

as the implicit assumptions described above are no longer valid. An extensive mesh cannot behave like a point source of current unless viewed from an immensely large distance. It also cannot be applied if there is not enough space to place the auxiliary electrode sufficiently far away, even if the grounding system is not very extensive. Since the electrode can no longer be assimilated to a current point,

where

is the potential created by the electrode at point x, considered as isolated and the distance D is not well defined since it must correspond to the distance at which

VA coincides with the true potential of the electrode. Dividing by the injected current I,

Note that from expression (4),

, if and only if

for some value of x, otherwise will be above or below

RG depending on the value of x. This condition is equivalent to the 62% rule when it is not possible to assume that the electrode to be measured behaves as a current point. Next, the so-called correction factor

will be introduced. It is defined as the ratio between the true grounding resistance and the resistance measured in the field

. According to (4), it can be written as

where the coefficients

and

have been introduced. These coefficients

,

turn out to be parameters of the electrodes and can be calculated for single-layered soils of resistivity

.

Therefore, the proposed method requires precise knowledge of the nature, geometry, and placement of the electrode, information that is presumably available, with which to evaluate and . Once is obtained for a specific position of the potential probe, the electrode resistance is measured, and the grounding resistance is found using . Since these expressions have been derived from a drastic simplification, such as considering an extensive electrode as a point source at short distances, it is expected that will depend on x and actually represent an upper bound to the true grounding resistance value. It should be noted that in the three-pin method, the measured resistance is always lower than the real value.

As a comment, the denominator of (5) contains actually the touch potential of the electrode at distance x per unit of current and soil resistivity, known as

and defined by

, so (5) can also be expressed as

The magnitude

can be evaluated theoretically, just like

, given the nature, geometry, and positioning of the electrode in the soil. When dealing with extensive electrodes or with auxiliary current electrodes close to the electrode being measured, it becomes necessary to determine the appropriate value of D to use. It might be useful to rewrite (6) by introducing two distances,

where

D1 represents the distance between the auxiliary current electrode and the coordinate origin used to define the electrode being measured and

D2 is the optimal distance from the auxiliary electrode to the electrode being measured to obtain the potential

VA according to the first equation in (3). In critical situations, that is, when

D1 is not very large, we propose averaging

RG evaluated with two different values of

D2, corresponding to the nearest and farthest distances from the auxiliary electrode to the extensive electrode being measured. It is easy to see that

if both are large compared to the size of the electrode being measured so the point current approximation for the grounding electrode becomes quite accurate.

In the proposed method, we start with a known "theoretical" electrode for which it is possible to calculate

,

and therefore

according to (6). However, the electrode to be measured may not exactly correspond to the "theoretical" electrode. It may be altered for various reasons, so its resistance will not match the theoretical resistance. If we measure

, then applying the correction factor

will not result in

. The main causes include oxidation or deterioration of the conductors that make up the electrode. Besides, the measurement can also be altered because the electrode is interconnected with other external grounds. This is a common practice that significantly reduces the resistance of the joint ground. With electrode deterioration the measure typically leads to grounding resistances

somewhat higher than those of the unaltered electrode, which, when multiplied by the correction factor, results in an overestimation of

. Thus, generally the result will be

. However, for interconnected electrodes, the measurement will give an underestimation of

RG. In either case, the proposed method will give the correct reading that corresponds to the case, and it is the task of the technical staff to determine the usefulness of the measurements. This hypothesis will be verified with the help of a numerical example in which a flat square electrode with a side length of 4 meters, made of conductive rods with a radius of 9mm, is buried at a depth of 0.5 meters. The soil is considered homogeneous with unitary resistivity. We are going to simulate the measurement of the grounding resistance by placing an auxiliary current rod 200 meters away from the electrode using the fall-of-potential method. For the same type of electrode, two situations will be addressed. In one case, the electrode has no issues, while in the other, it is assumed that part of the electrode is damaged and inactive in releasing current to the ground.

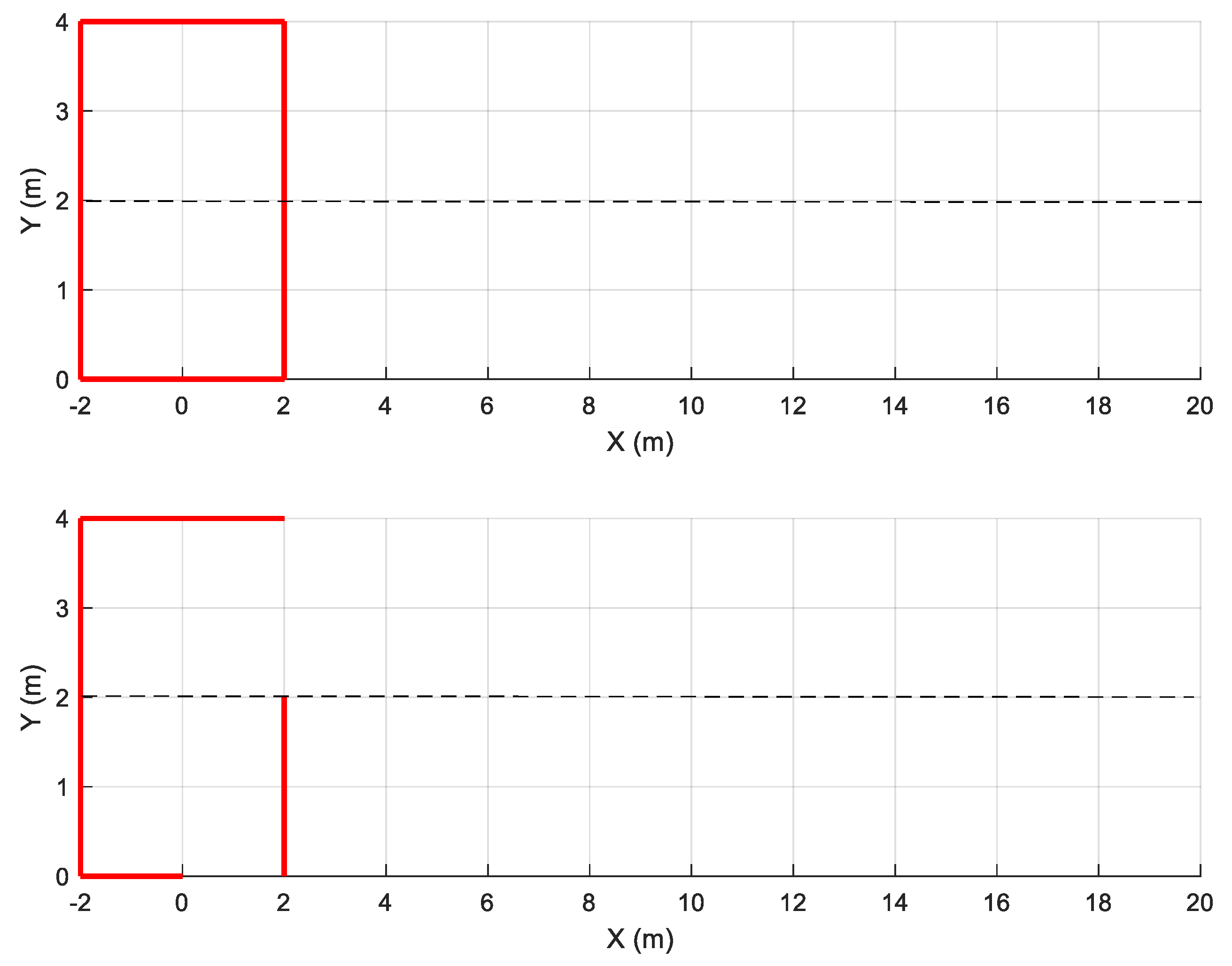

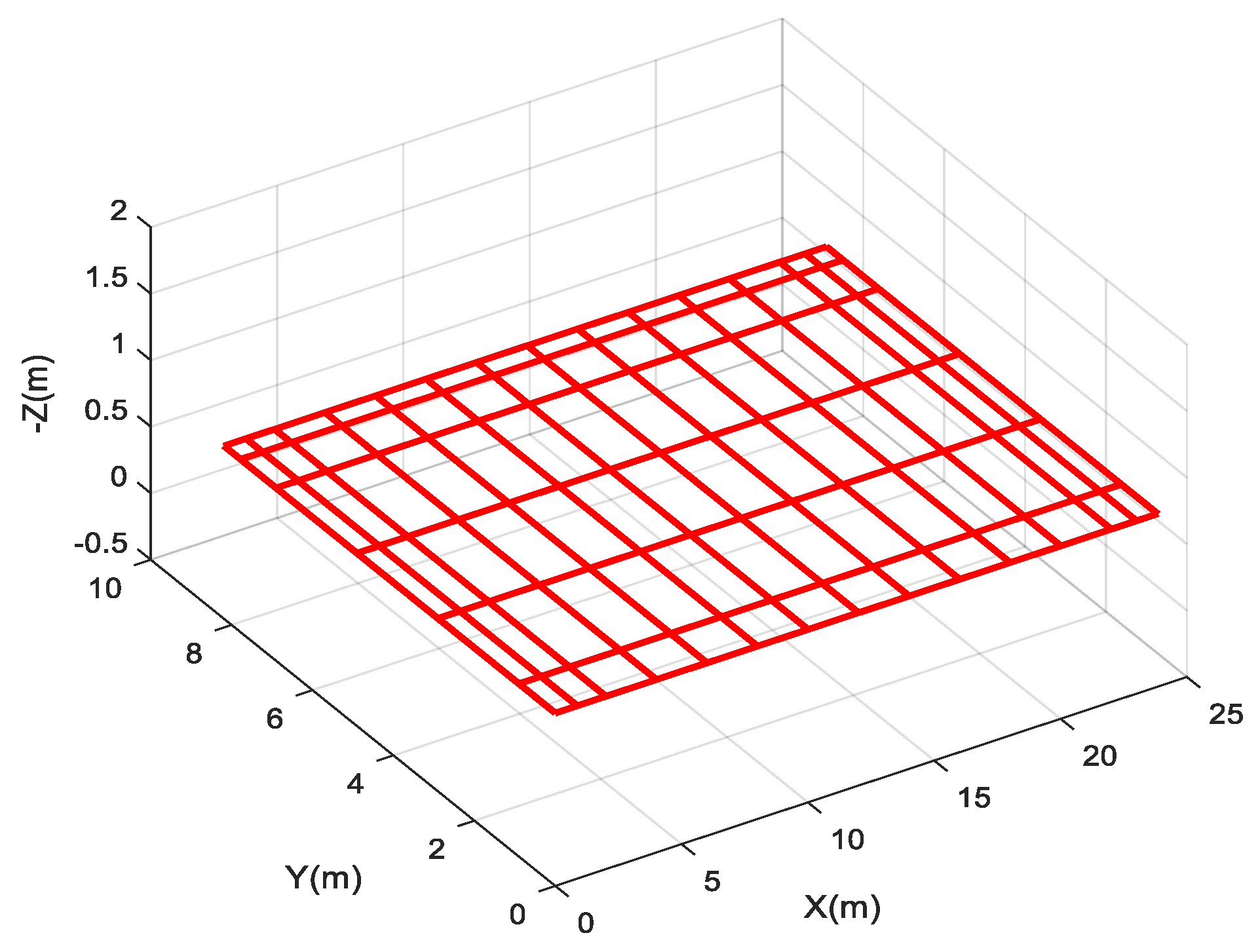

Figure 2 shows the profiles of the electrode, and the dotted line represents the path traced to evaluate the potentials on the ground.

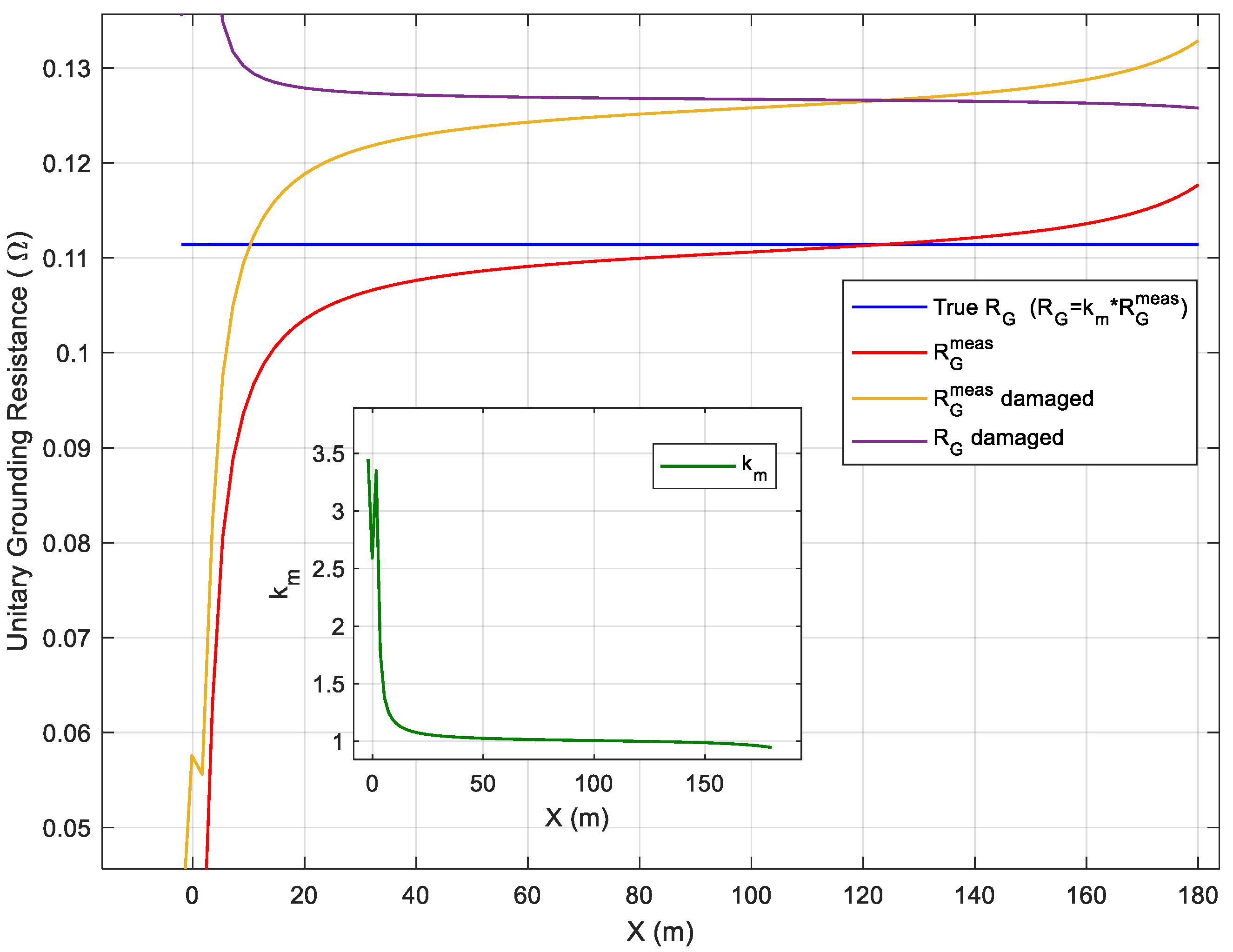

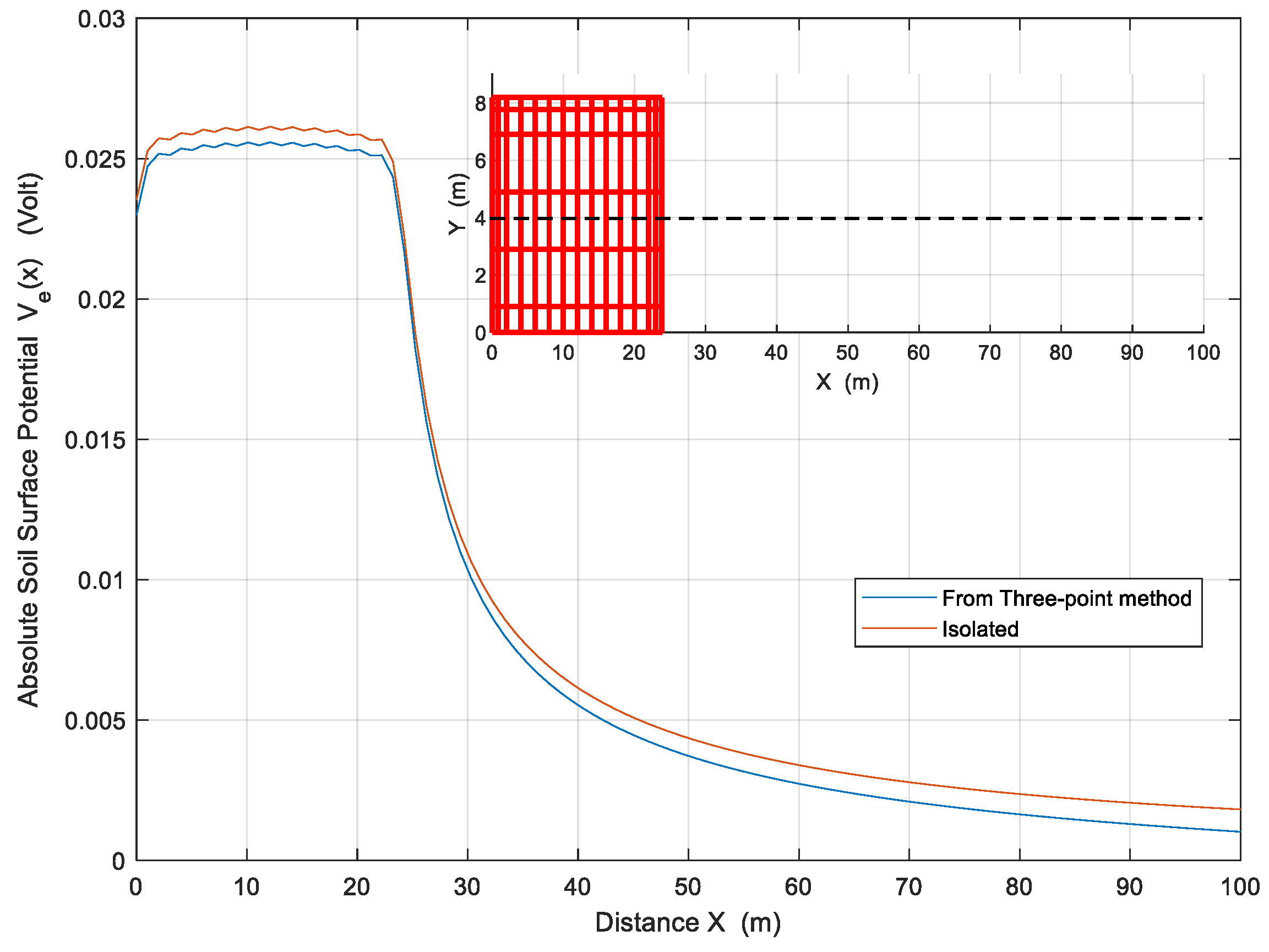

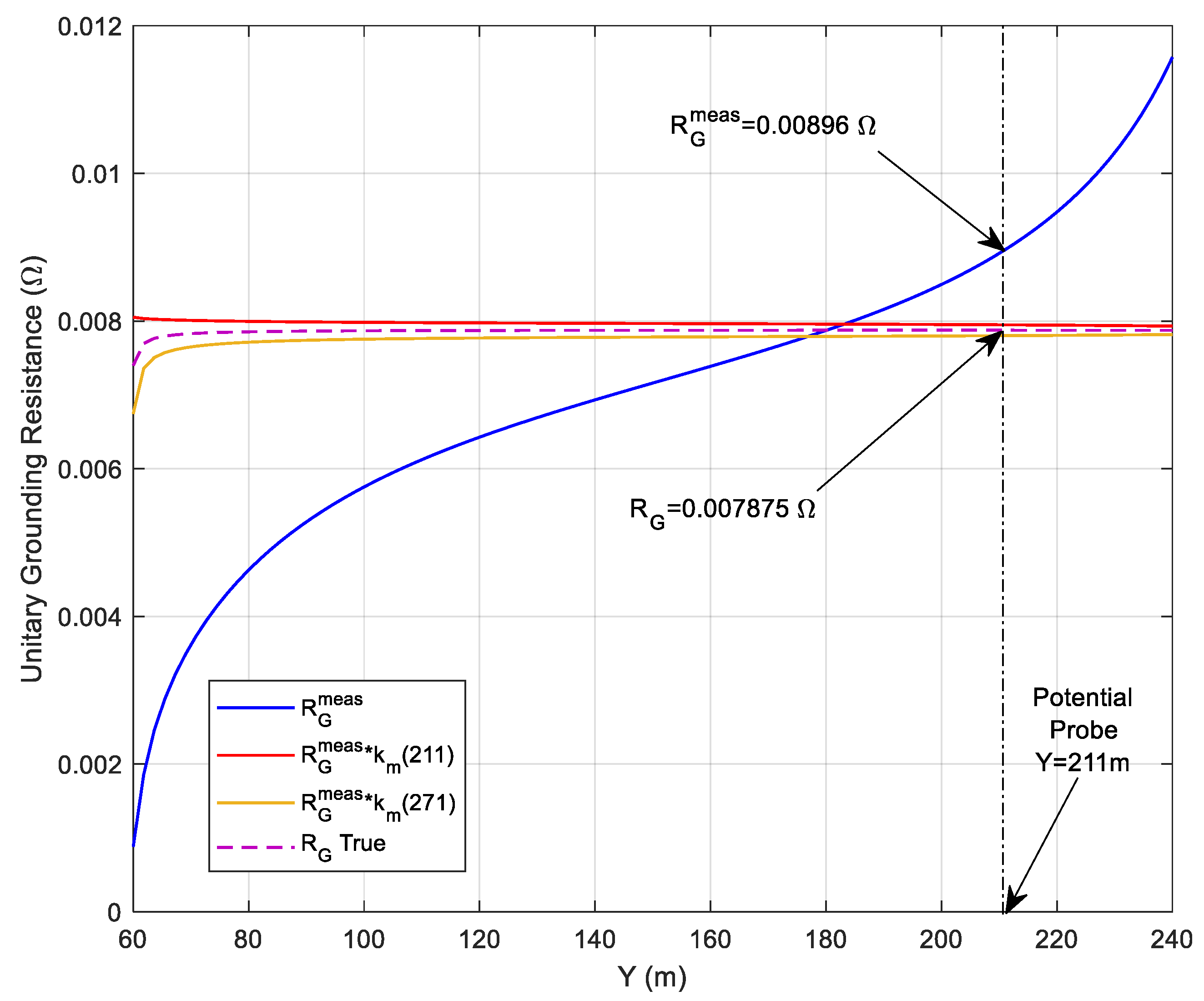

The difference of potential profile at points on the ground (z=0) along a straight line from the left side of the electrode at x=-2m to x=180m when the y-coordinate is fixed at y=2m, will be measured for both electrodes. Since the soil has a unit resistivity and the injected current is 1A, this potential difference represents the unit grounding resistance as a function of the distance x at which the potential probe is located, measured by the three-pin method, when the auxiliary electrode is, as previously mentioned, 200 meters from the electrode being measured.

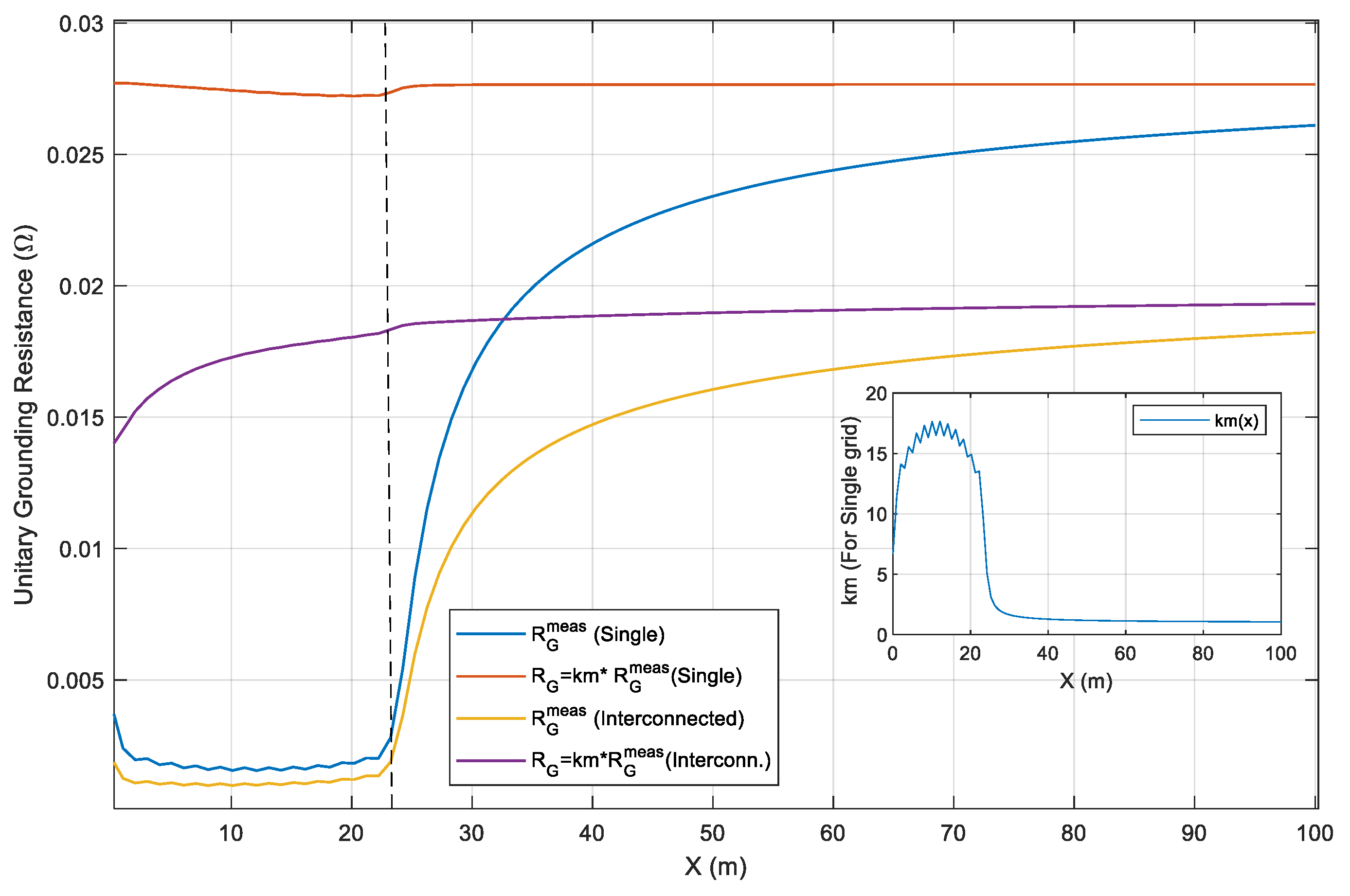

Figure 3 shows the grounding resistance measured using the three-pin method, placing the potential electrode at distance

x. The figure shows this measured resistance for both the original (red line) and the damaged electrode (beige line). The figure also shows the resistance corrected by the correction factor

km, which is shown in the subfigure. The blue line is the result of this correction for the original electrode. As seen, the value

RG = 0.1114 Ω corresponding to the true resistance of the original electrode is obtained. In contrast, for the damaged electrode, applying the correction factor results in an

RG value above the true resistance value, which is 0.1266 Ω. Note that the correction factor is derived from the original electrode parameters and is applied to all situations, whether the electrode is damaged or not.

Author Contributions

Jorge Moreno (JM), Eduardo Faleiro (EF), Daniel Gracia (DG), Pascual Simon (PS), Gregorio Denche (GD) and Gabriel Asensio (GA). Conceptualization, JM, EF and PS.; methodology, JM, EF,DG and PS.; software, DG, GD and GA.; validation, JM,EF,PS and DG; formal analysis, JM,EF,DG and PS.; investigation, JM, EF and PS; resources, DG, PS, GD and GA; data curation, PS, GD and GA; writing—original draft preparation, JM, EF, PS, GD and GA; writing—review and editing, JM, EF, GD and GA; visualization, JM and EF.; supervision, JM and EF.; project administration, JM and EF. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.