Introduction

All ancient writing systems can be classified into three main types of signs or characters: word signs, syllabic signs, and alphabetic characters. Word signs, also known as logograms, originated from pictographic writing and consisted of three types of signs: ideograms, rebus writing, and phonograms (Schmandt, 1979).

A significant breakthrough in the history of writing was the use of signs to represent sounds without conveying specific meanings. This breakthrough led to the development of syllabic signs by creating phonetic syllables from word signs.

The Egyptian Script played a crucial role in the early development of writing. It introduced "alphabetic" or uniliteral consonantal signs by disregarding the vowels present in the corresponding syllabic words. However, Egyptian writing remained predominantly ideographic until its conclusion. True alphabetic writing emerged with the Semitic consonantal scripts around 1500 BC (Hawkins, 1979; Wansbrough, 1983; Driver, 1976). The Greeks later added vowels in 800 BC, completing the evolution of alphabetic writing.

Ancient Oriental scripts can be classified into three types based on the signs they employed: logographic scripts, syllabaries, and alphabets. Each type consists of distinct components: logograms, syllabic signs, or alphabetic characters (Mahadevan, 1989).

The classification of the Indus script has been a central topic of debate among scholars. The determination of the total number of signs in the Indus script is a crucial factor that influences various opinions. It poses a paradox for the writing system of the Indus Valley. Despite the existence of a significant number of compound signs, the possibility of considering it as an alphabet has not received much attention from scholars. This lack of attention can be attributed to established premises regarding the evolution of epigraphy. Prominent scholars such as Mahadevan and Parpola consider the script as logo-syllabic, consisting of word signs and phonetic syllables, while other scholars support the same proposition (Mahadevan, 1988; Parpola, 1994; Wells, 2015; Zvelebil, 1970). Rao is the only scholar who deciphered the script as an alphabet (Rao, 1982), and Kak also supports the possibility of it being alphabetic (Kak, 1994). Some scholars suggest the presence of partial pictographic signs (Clauson, Chadwick, 1969; Robinson, 2015; Fairservis, 1983). All the Indus texts exclusively consist of sequences of numbers (Subbarayappa, 1996) even in some scholarly walks the script has not been accepted as a writing system and Indus civilization as a literate civilization. (Witzel et.al, 2004).

Numerous claims of decipherment have been made regarding the Indus writing system, leading scholars from around the world to conduct extensive examinations. Posselh provides a historical perspective on these scholarly endeavors and presents a comprehensive account of the contributions made by researchers from diverse regions. His assessments demonstrate a balanced approach, refraining from endorsing any decipherment claim unequivocally due to the lack of conclusive evidence (Posselh, 1996).

‘The image of a literate Indus Valley has been considered an incontrovertible historical fact by most specialists. If this image were true, the vast geographical extent of archaeological ruins in the Harappan civilization would make it the largest literate society of the early ancient world, underscoring the importance of the Indus script for ancient Indian history and human history as a whole’ (Witzel et al., 2004).

While the concern about the literate Indus Valley is valid, the pursuit of this idea in the research history of the Indus civilization has been limited. However, the truth reveals its significant impact on human history as a whole. The obstacle lies in the premises of research. Alternatively, if the search had focused solely on continuity, decipherment would not have taken such a long time. The comprehensive examination of writing systems in Mesopotamia and Egypt was made possible through the discovery of bilingual and trilingual tablets. These invaluable artifacts provided researchers with insights into the earliest forms of writing, such as the appearance of cuneiform on clay tablets around 3200-3000 B.C. (Michalowski 1996), and the use of hieroglyphics on ivory plaques dating back to 3100 B.C. (Ritner 1996). The earliest evidence of writing, found in the form of graffiti from the late 4th millennium BC, presents a compelling case. When comparing the inception of Sumerian cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs to their eventual evolution into alphabets, it becomes evident that the Indus Valley civilization had already developed an alphabetic system during its mature phase. In contrast, the journey of cuneiform and hieroglyphs towards an alphabetic writing system was significantly longer. This fact qualifies the Indus Valley civilization as the largest literate civilization and demonstrates its superiority over other contemporary civilizations. Thus, it is reasonable to consider the roots of the ancient alphabetic system to be found in the Indus Valley, as this approach aligns with the truth. In the recent study Convolutional neural networks were employed to examine the proximity of Phoenician alphabet letters and Brahmi symbols to the symbols found in the Indus Valley script. Remarkably, analysis revealed that, overall, the Phoenician alphabet exhibits a significantly closer resemblance to the symbols of the Indus Valley script compared to the Brahmi script (Daggumati, et.al, 2018). After a period of five years, the same cautious traditional assumption remains prevalent in the study. The analysis has yielded three distinct groups arranged in chronological order. The first group includes Sumerian pictograms, the Indus Valley script, and the proto-Elamite script. These scripts are thought to have originated in Mesopotamia during the early Bronze Age. The second group consists of Cretan hieroglyphs and Linear B, which emerged in Europe during the middle Bronze Age. Lastly, the third group comprises the Phoenician, Greek, and Brahmi alphabets, which likely originated from the Sinai Peninsula during the late Bronze Age. The classification of these groups is based on their geographical locations and estimated periods of origin. (Daggumati, et.al, 2023). The prevalent use of a particular sign, known as P-311 or M-342 (Kenoyer, 2006), adorned with diacritical marks. Based on this evidence, it can be inferred that this fully developed writing system emerged at its inception, suggesting a divine origin in other words, the script was invented at once according to the Parpola’s opinion during the final phase of the early Harappan period between 2800 to 2500 BC (Parpola, 2010). Its primary users were common people, including potters, artisans, and individuals of earlier doctrinal seminaries. Thus, perfection should not be expected in its nascent stages. However, the development of doctrinal seminaries and the flourishing of civilization led to the continuous refinement, maturation, and establishment of a standardized script. It reached its peak around 2600 to 2500 BC (Parpola, 1996), coinciding with the zenith of the civilization itself. Minor graphic variations exist for many signs in these scripts, but the script remained in a standardized form without significant changes throughout its existence (Mahadevan, 1989). The extraction principles of alphabetical characters remained unaltered, with only minor adjustments made to the format. Noteworthy modifications or substitutions may have occurred only in the representation of avian and animal motifs. Hence, the theories of the evolution of writing systems, such as pictographs, ideographs, logographs, or syllables, do not find application in the Indus writing system. The temporal context of the Indus writing system predates the establishment of organized doctrinal seminaries. Therefore, the nascent or formative state of both the doctrinal seminaries and the writing system in the Indus Valley predates the development and maturation of the valley itself, potentially tracing back to approximately 1000 BC.

Embracing a broadminded and imaginative approach is crucial, as the idea of deciphering the Indus script as an alphabet has the potential to challenge existing premises in epigraphy, linguistics, archaeology, genetics, and anthropology. By adopting this broader viewpoint, researchers may overcome limitations imposed by conventional assumptions and gain new insights into the ancient civilization that has fascinated scholars for generations.

Why and how is the Indus Script an Alphabet?

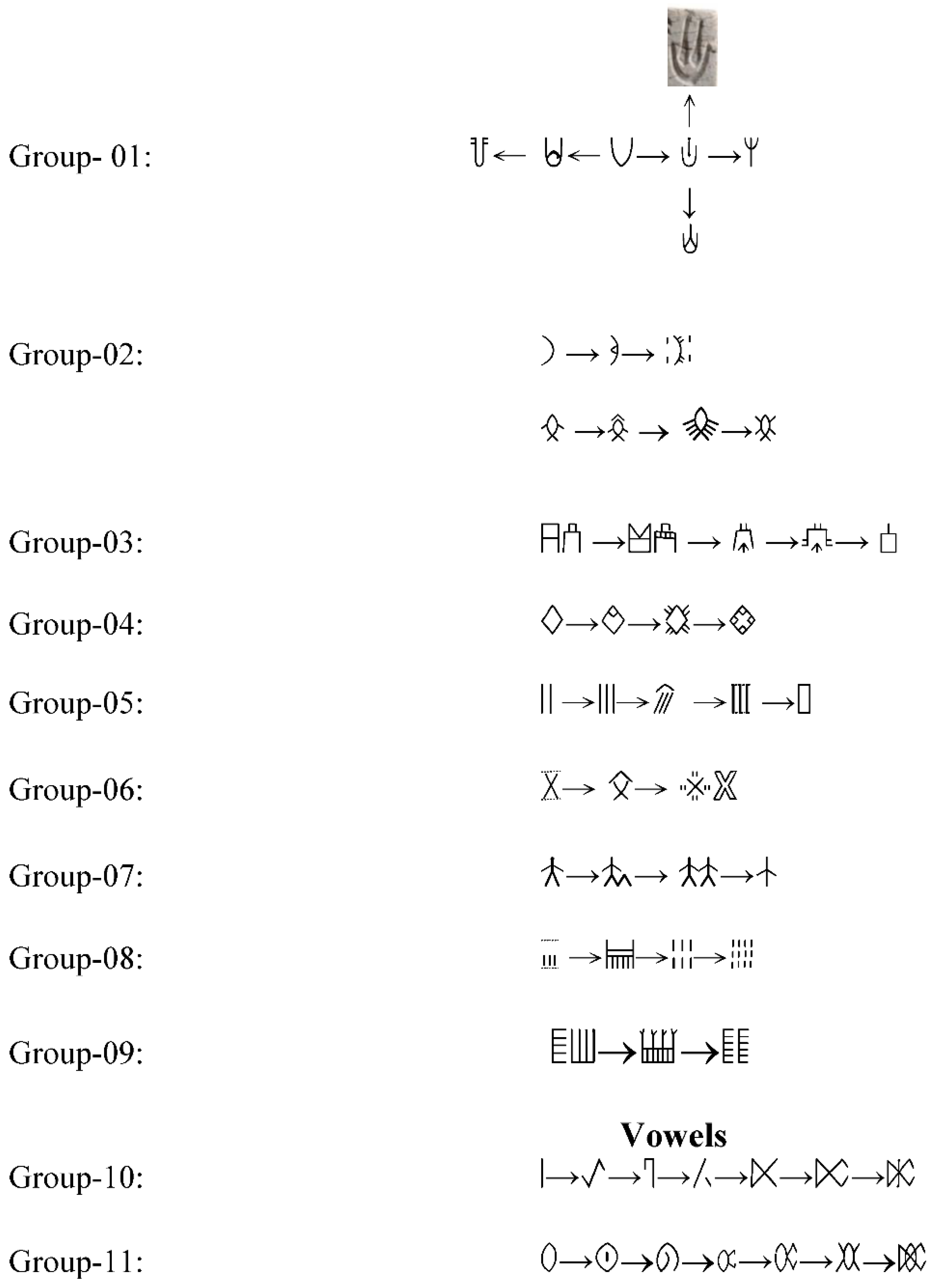

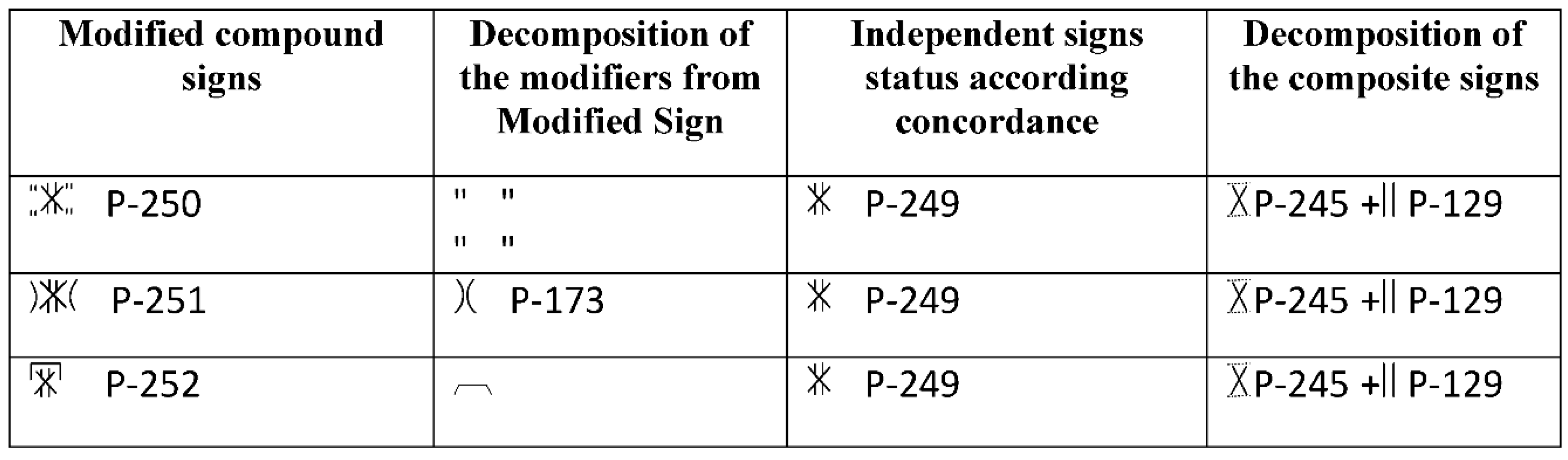

By decomposing compound signs, modifiers, potential diacritical marks, and single basic signs can be isolated from the ligatures. This process allows us to determine the actual number of primary or basic signs, which provides reasonable evidence in support of an alphabetic system.

Determining the accurate number of primary signs in the Indus script has long posed a challenge, yet it holds the key to unlocking a deeper understanding of this ancient writing system. A crucial aspect of research involves decomposing signs to identify and isolate fundamental or primary signs. This enables us to examine how their combinations result in new designs or formats.

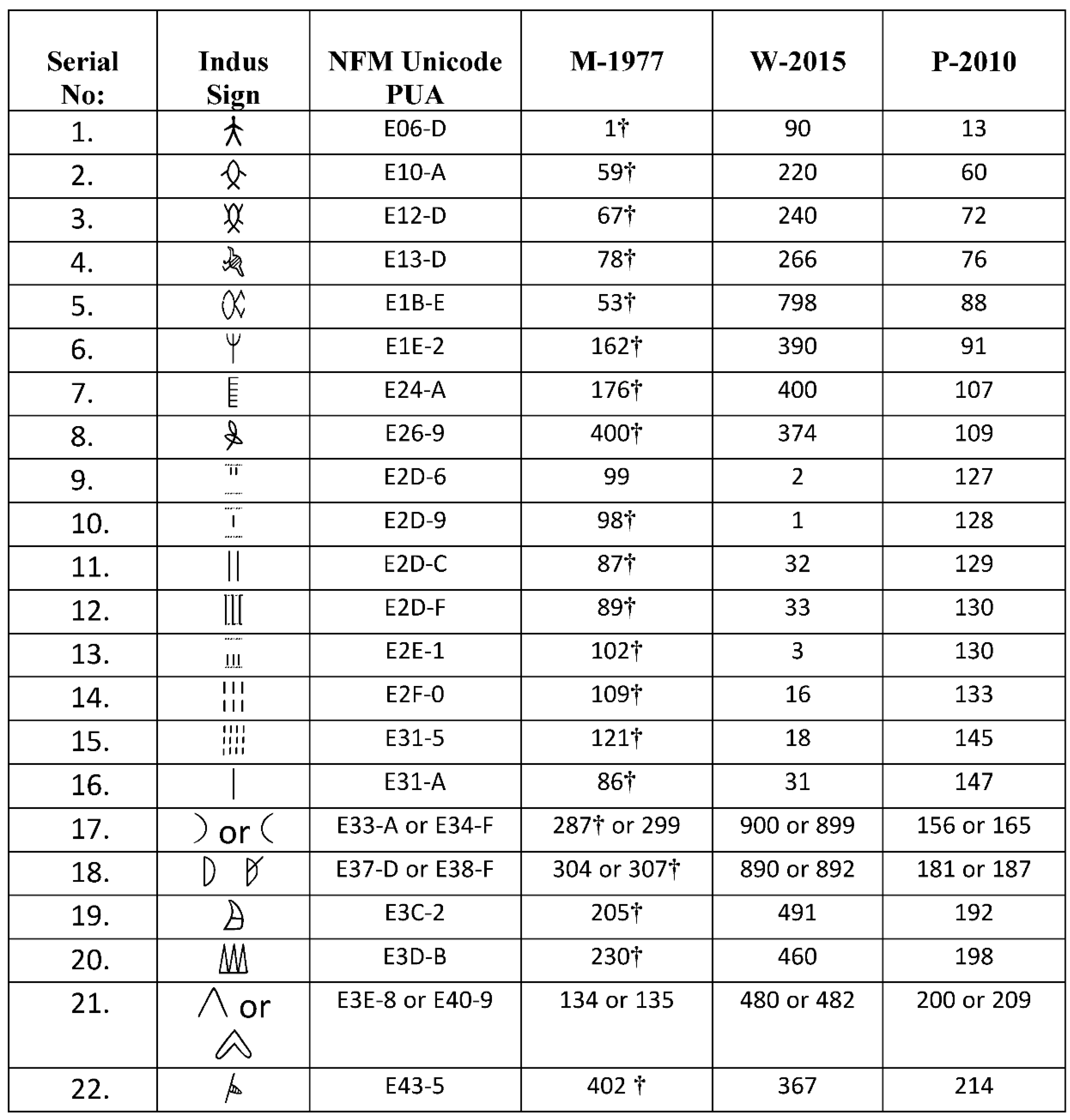

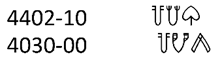

In a study conducted by Yadav et al. (2010), Indus signs were categorized into basic signs (154), provisional basic signs (10), and modifiers (21). Wells, in his extensive collection of signs, classifies them into different categories: simple signs totaling 127, complex signs totaling 175, compound signs totaling 135, and 146 signs marked with additional markings, along with 18 sets of markings (Wells, 1998). On the other hand, Mahadevan categorizes the signs into ideograms, phonograms, conventional signs, numeral signs, and phonetic signs (Mahadevan, 1989), while Fairservis categorizes them into different groups: some from ancient origins, some from local origins, compounds derived from the same local origin, and rare affixes (Fairservis, 1992). In contrast, Rao's conclusion suggests the existence of only 62 signs and proposes the evolution of graphic variants. However, Mahadevan does not seem to agree with Rao's perspective on this matter (Rao, 1982). It is important to note that previous studies by different scholars have yielded varying concepts of what constitutes a basic sign, resulting in different counts of Indus basic signs. However, this particular study identifies only 40 basic signs.

In the Indus writing system, primary or fundamental signs are commonly and independently utilized, while the remaining signs are compounds that can be broken down based on the typology of their allographs. Typically, compound signs consist of two or three composite signs, although some instances may be considered illegible. By decomposing these compound signs, a significant number of primary signs or basic phonemes can be identified. This observation provides evidence supporting the notion of considering the Indus writing system as alphabetic.

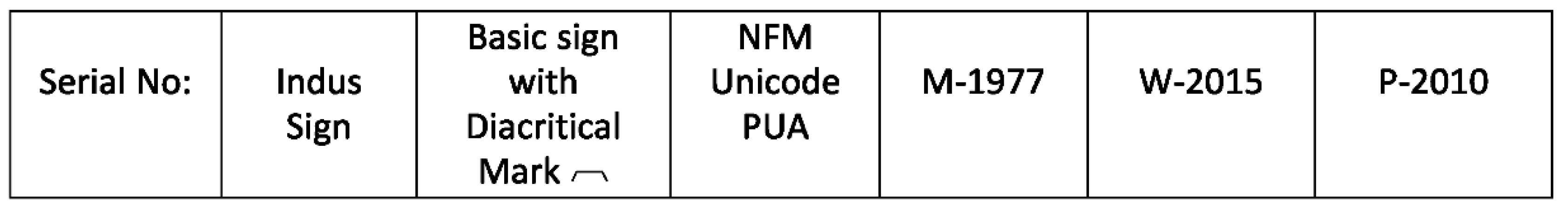

In order to gain a more comprehensive understanding of primary signs and thoroughly analyze their behavior, it is crucial to focus on potential vowel diacritical marks and principal modifiers. These elements are commonly used in conjunction with multiple signs. While many diacritical marks and the wedge symbol modifier can also be employed independently with the signs, their combined usage introduces variations in allographic position and modifies the sign in distinct allographs and graphic variants.

Likewise, the combination of two or three composite signs results in different sign variants, highlighting the distinct writing styles that emerge through their arrangement. By studying these variations and combinations, we can delve deeper into the Indus writing system, gaining insights into its complexity and the nuanced ways in which it can be expressed.

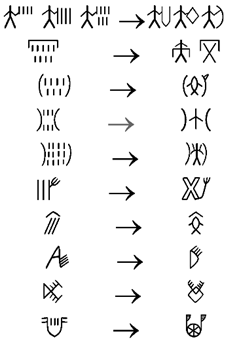

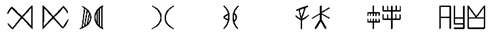

When examining the primary signs, excluding compound signs, we observe a consistent pattern in their modification, leading to the creation of new graphemes. The process of altering the allography of the fundamental signs is evident, resulting in the formation of different phonemes within the same class. The following section provides a detailed exploration of the variations in the allographic design of the primary sign.

The specific concept of the classification and extraction of the sign as a phonemic variations and typological design from the fundamental allographic form of the signs:

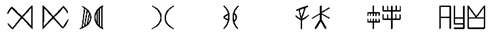

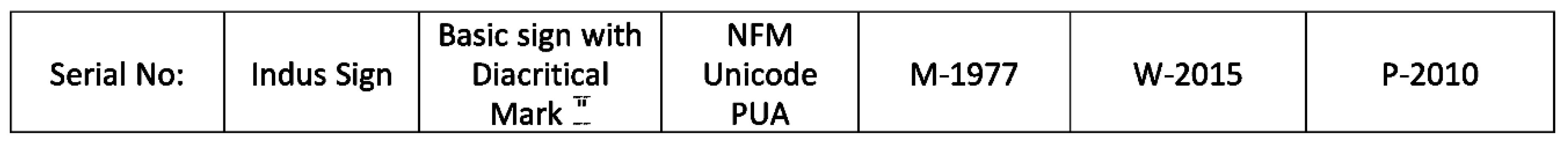

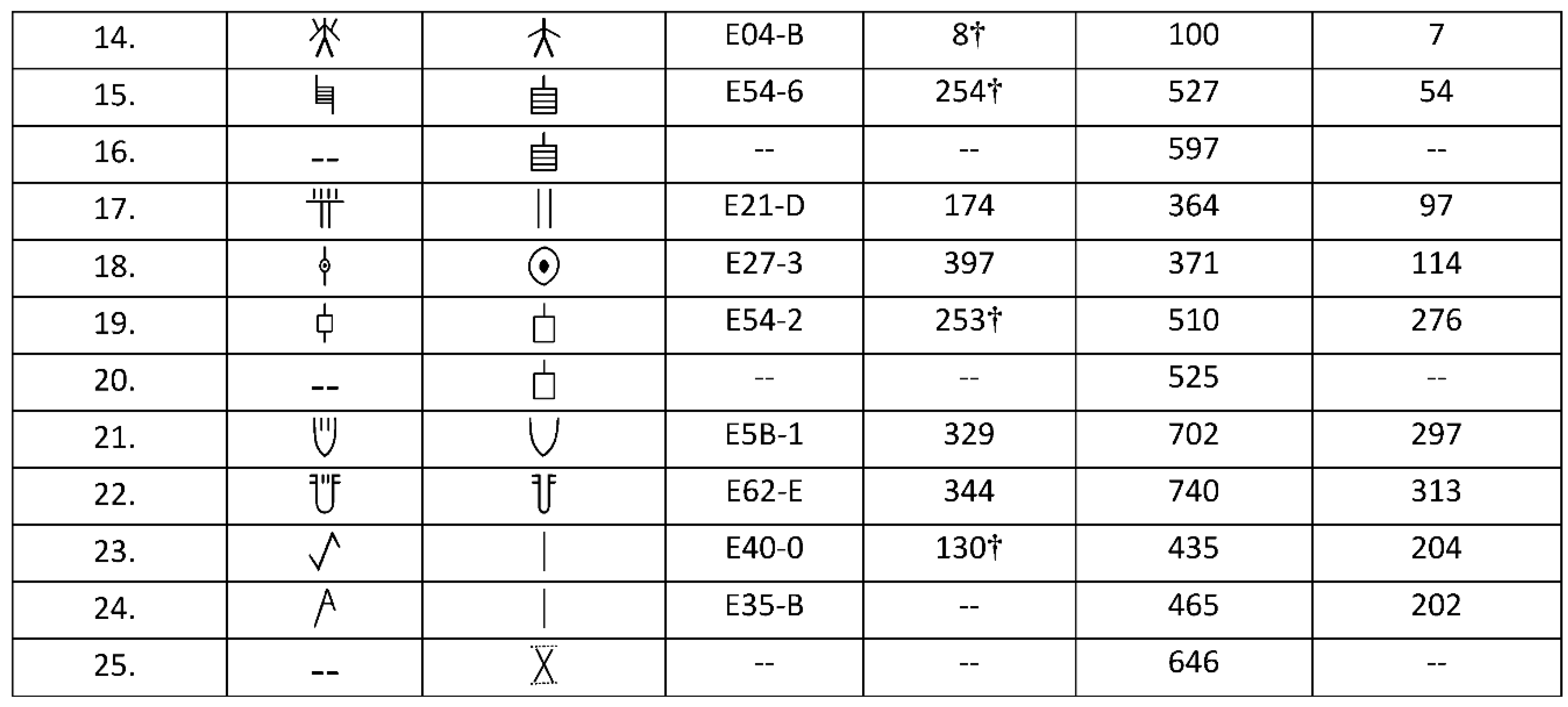

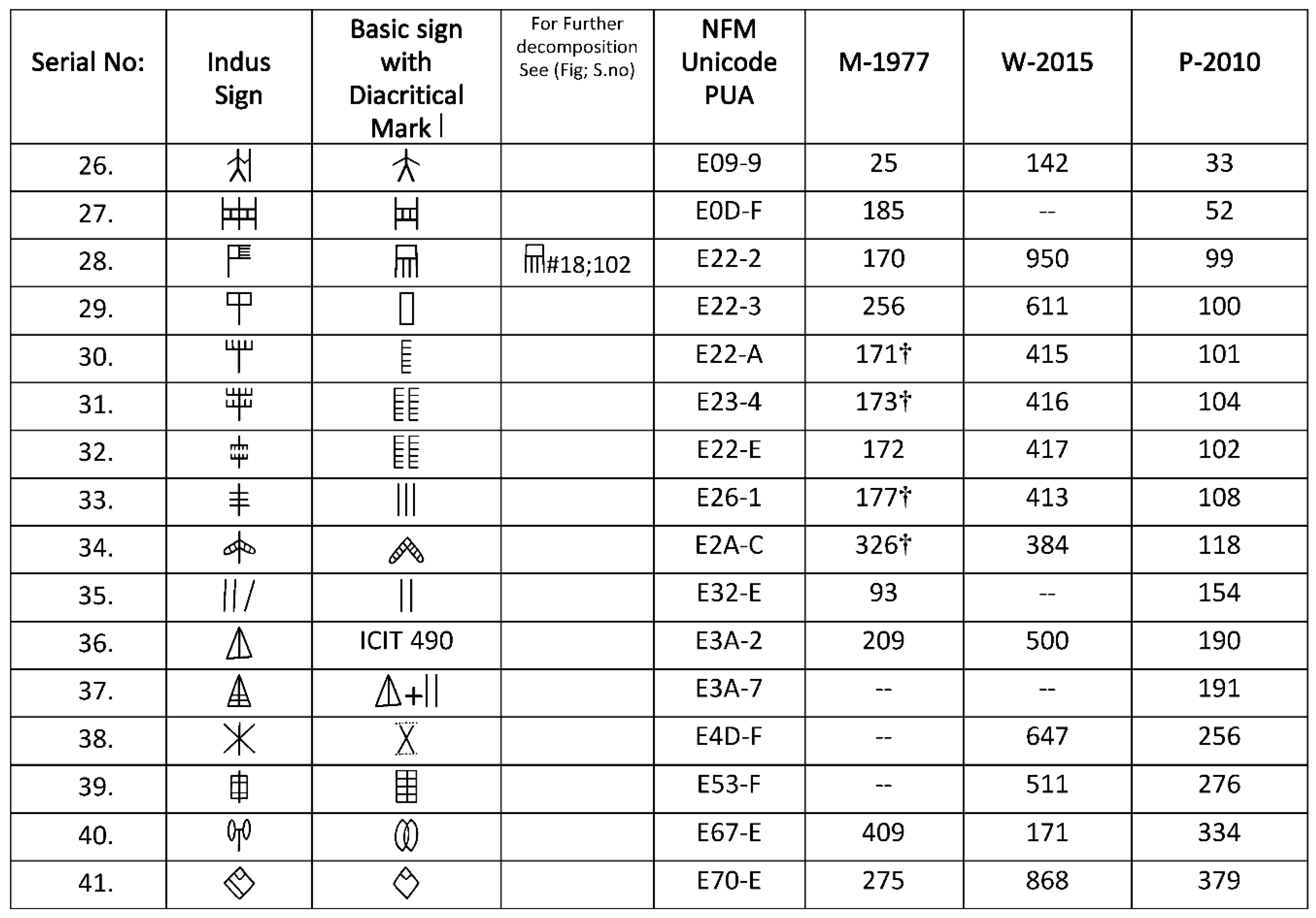

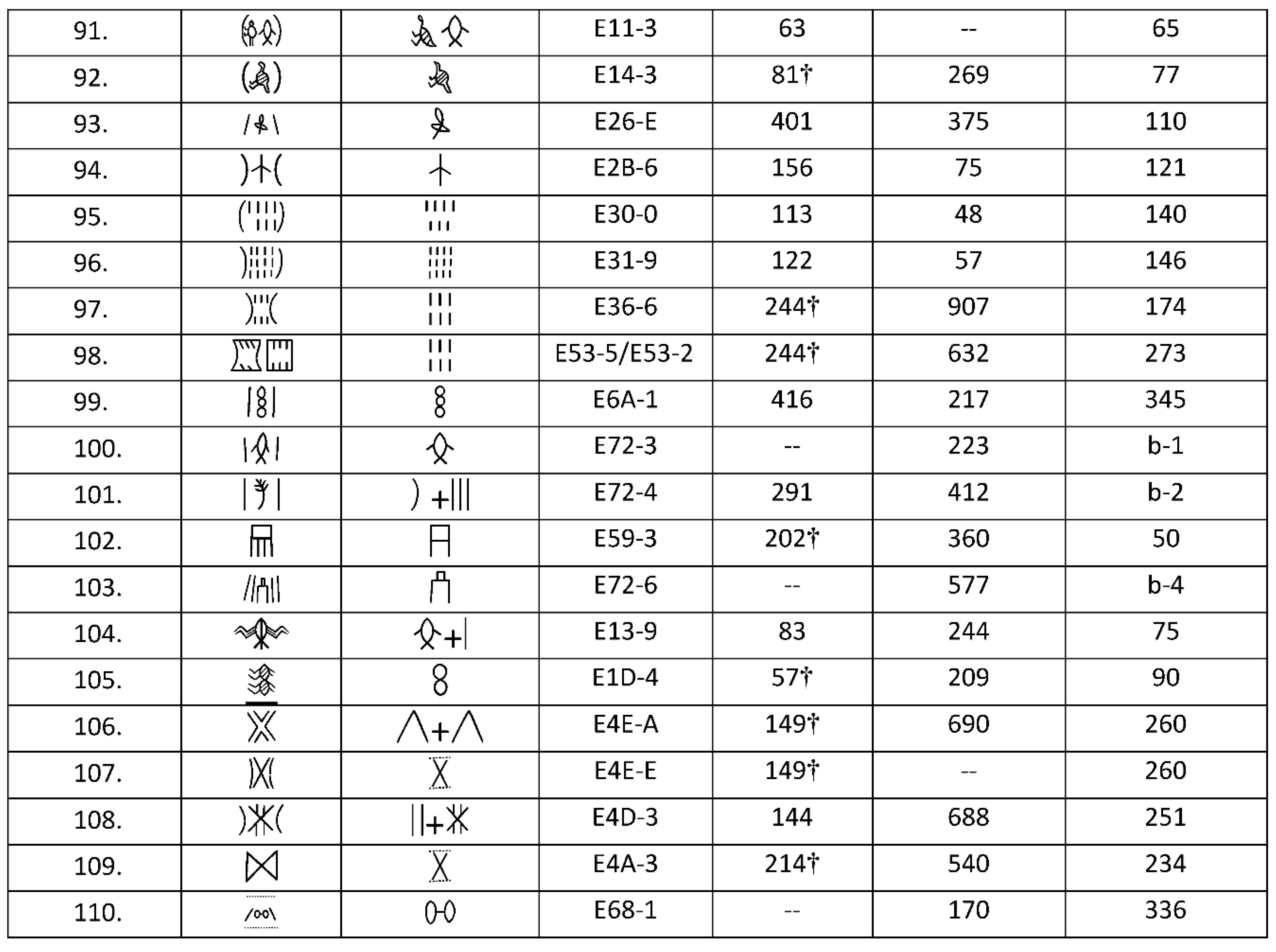

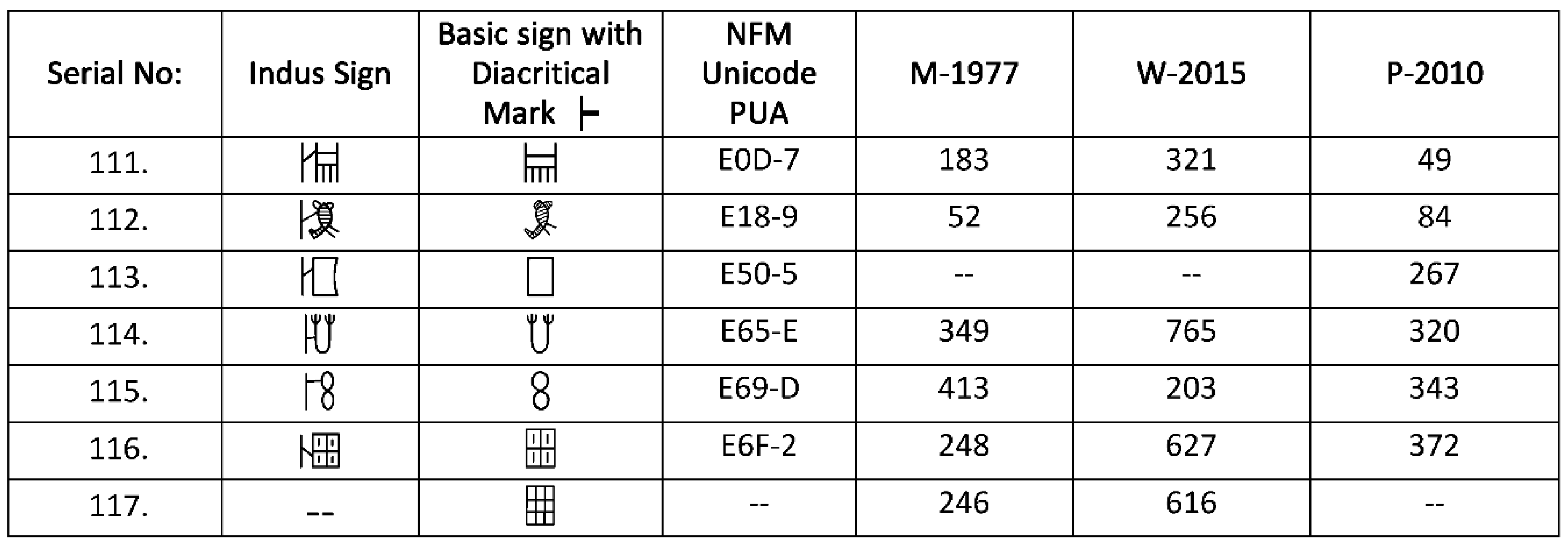

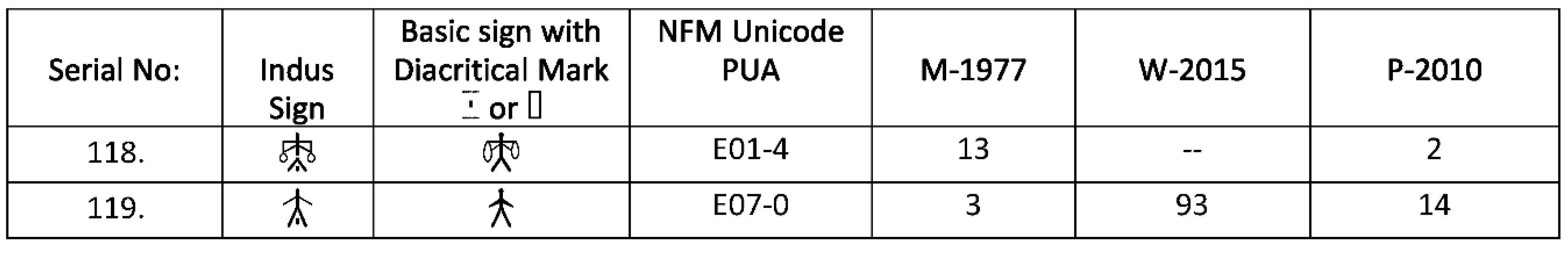

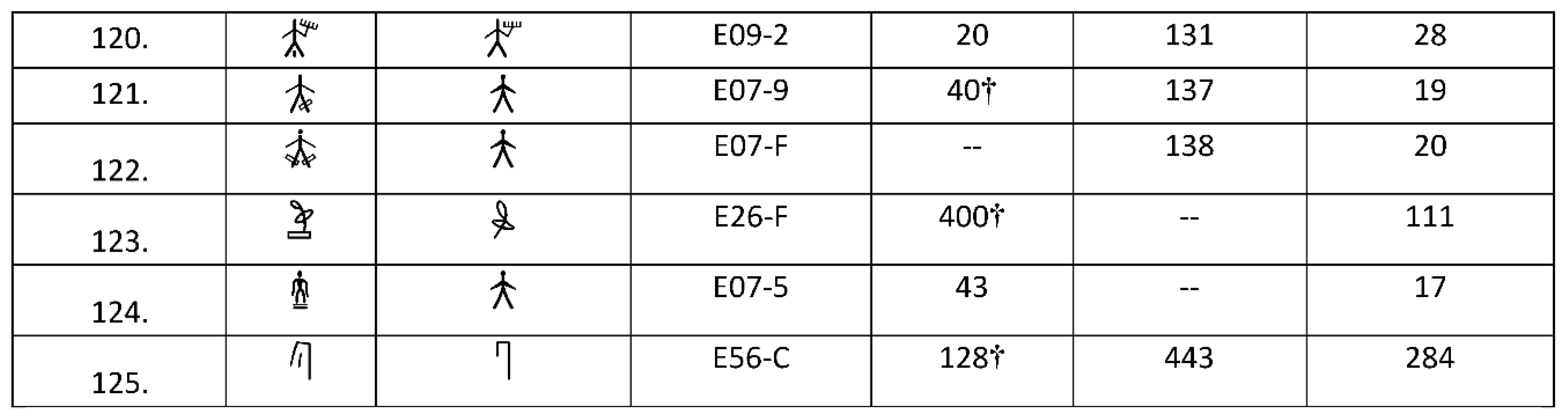

The study focuses on a detailed structural analysis of the general makeup and mechanics of the Indus signs discovered to date. The primary decomposition for this study is the sign list of Asko Parpola, which has been utilized in the NFM Indus font based on his concordance. Additionally, the sign lists compiled by Mahadevan (1977) and Bryan Well (2015) have been included to further enhance our understanding.

Primary Data Source

Mahadevan’s comprehensive corpus, which is the first of its kind, consists of 419 signs found on 2,911 inscribed objects, comprising a total of 3,554 lines of text. The list also includes variants of signs (Mahadevan, 1977).

Asko Parpola's influential work in the field of Indus script research includes the compilation of a sign list based on approximately 3,700 legible inscriptions. This list, consisting of 385 primary signs along with an additional 5 variants, has been transformed into the NFM-Indus Script font through collaboration with the National Funds for Mohenjo Daro and the Culture Department of the Government of Sindh.

Parpola's dedication to the study of the Indus writing system has yielded valuable insights. Through a meticulous process of collection and critical editing, he aimed to determine the number of graphemes and the average word length present in the script. His investigation involved identifying primary signs as well as composite signs, leading to the development of a comprehensive sign list for the Indus script. Each entry in this list includes the principal graphic variant along with a corresponding decomposition (NFM-Indus Script; Introduction).

In addition to Asko Parpola's seminal work, an updated sign list has been provided by Well (1998, 2006, 2011, 2015). This comprehensive list comprises 709 signs and represents the most recent compilation as of May 2022. The inscriptions containing these signs are housed within the ICIT database (Interactive Corpus of Indus Texts), which contains a total of 4,660 artifacts with inscriptions. It is important to note that some artifacts bear inscriptions on multiple sides, resulting in a grand total of 5,644 texts and 19,831 occurrences of signs. Among these, 3,657 texts are complete, accounting for 13,672 sign occurrences (Fuls, 2022). This updated information enhances our understanding of the Indus script and contributes to ongoing research in the field.

Mahadevan's concordance provides sign variants for only 178 out of the total 417 signs. This limited coverage makes it challenging for researchers to determine the appropriate usage of specific sign variants within the concordance or when encountered in the actual texts. However, Parpola's concordance proves to be more beneficial for researchers due to its comprehensive nature. Not only does Parpola provide original transcriptions, but his sign collection, embodied in the NFM-Indus Script, facilitates researchers in accurately reproducing Indus Texts based on the original sources.

Although there are discrepancies in sign classification methods between Mahadevan and Parpola, both researchers approximate a similar number of signs, around 400. This level of agreement establishes a foundational understanding of the sign inventory and contributes to further analysis of the Indus script.

On the other hand, the abundance of signs in Well's collection may appear excessive. However, a notable advantage is the inclusion of new entries that contribute to an expanded understanding of the compositional style of the signs. These additions provide insights into a fresh perspective on variant forms resulting from the combination of signs, as well as the identification of novel nuances in writing and engraving styles. Among these new entries, the following signs are featured: W-41, 42, 58, 85, 107, 141, 223, 225, 242, 316, 325, 326, 376, 418, 481, 490, 525, 591, 597, 793, and 843.

Apart from these specific signs, the remaining signs in Well's collection can be adjusted and aligned with Parpola's classification. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the classification of certain signs as distinct entities may appear exaggerated, and the underlying approach may not always adhere to a logical framework. Numerous examples from Well's collection could be cited to support this observation, but for brevity, I will mention only one instance, spanning signs 290 to 308, where even sign 311 could be considered as belonging to the same category. This highlights potential areas of divergence and raises questions about the classification system employed. On the other hand, it appears that Parpola sometimes exhibits an excessive emphasis on distinguishing signs, leading to an exaggeration in the number of signs documented in (

Figure 21). Additionally, there are several other compound signs that may not have been adequately addressed. Furthermore, there are instances where careful distinction seems to have been overlooked, as exemplified by signs #88, 292, and 341.

Note:

- a)

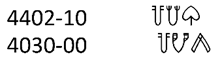

For the representation of mentioned sign collection, the terms are used for Mahadevan (M-000) for Parpola (P-000) and for Well's (W-000)

- b)

The sign † represents the sign variants according Mahadevan in APPENDIX- 1

Methodology

The process of isolating basic signs involves utilizing the grid structural methodology to visually recognize and separate the individual components within compound structures. This methodology enables us to identify and distinguish the basic signs from the complex ligatures.

By employing visual recognition techniques, we can isolate the modifiers, diacritic marks and compositing signs within the modified signs. This allows us to analyze their specific characteristics and understand how they contribute to the overall allography of signs.

Through the decomposition of modifiers diacritic marks and compositing signs, we gain a deeper understanding of their function and their impact on the possible phonetic value, reading, and meaning of the sign. This process helps us recognize and interpret the variative writing styles employed in the Indus script.

The grid structural methodology and the subsequent decomposition of modifiers, diacritic marks and compositing signs provide crucial insights into the organization and structure of the modified compound signs in the Indus script. This knowledge enhances our understanding of the complexity of the writing system.

By employing these analytical techniques, we can unravel the intricate nature of the Indus script and gain a more comprehensive understanding of its writing conventions and communication methods. The process of isolating basic signs is further explained in the following section:

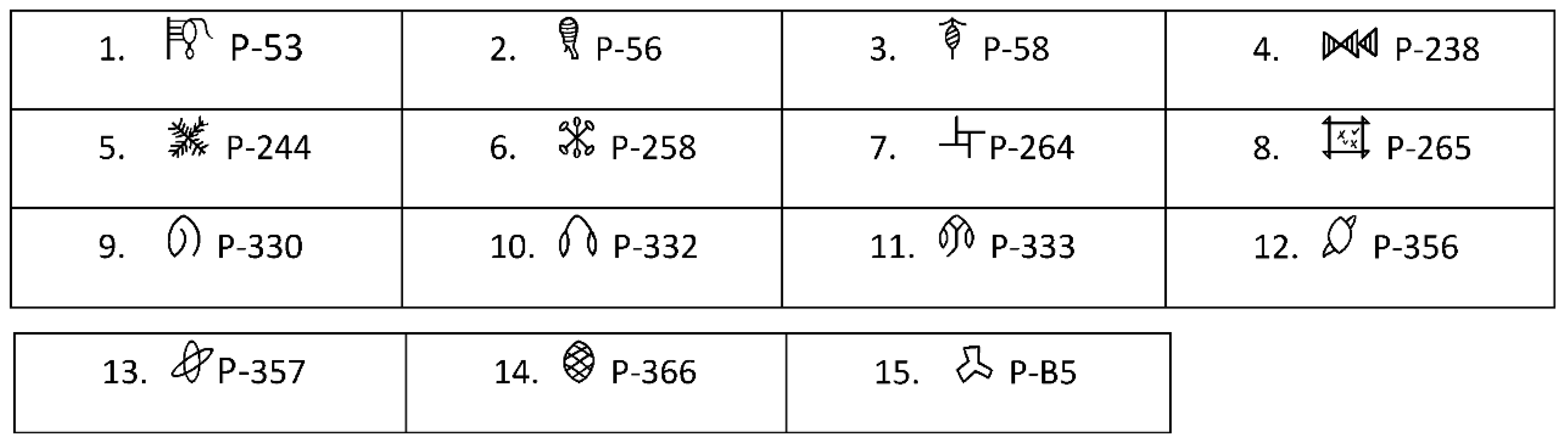

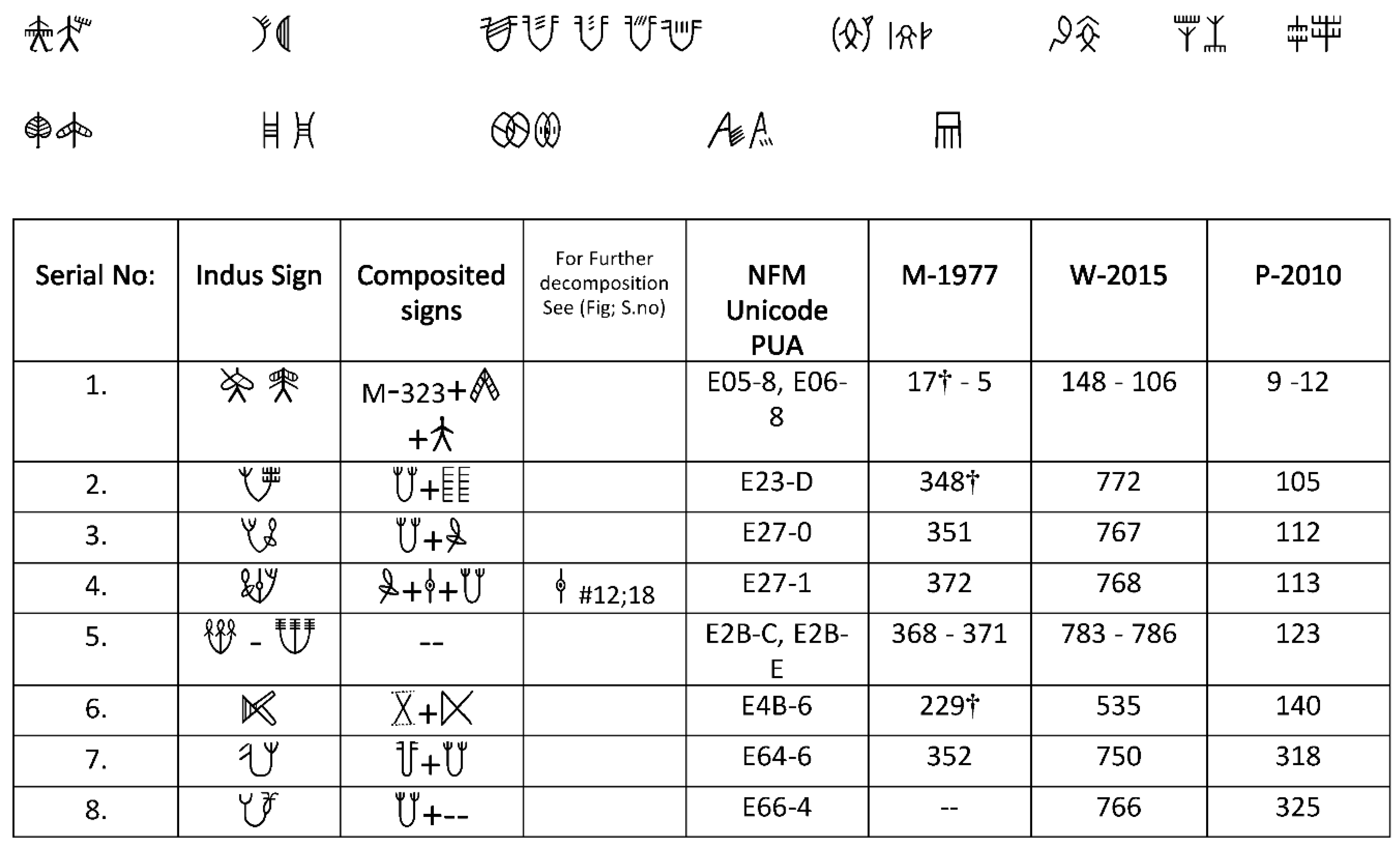

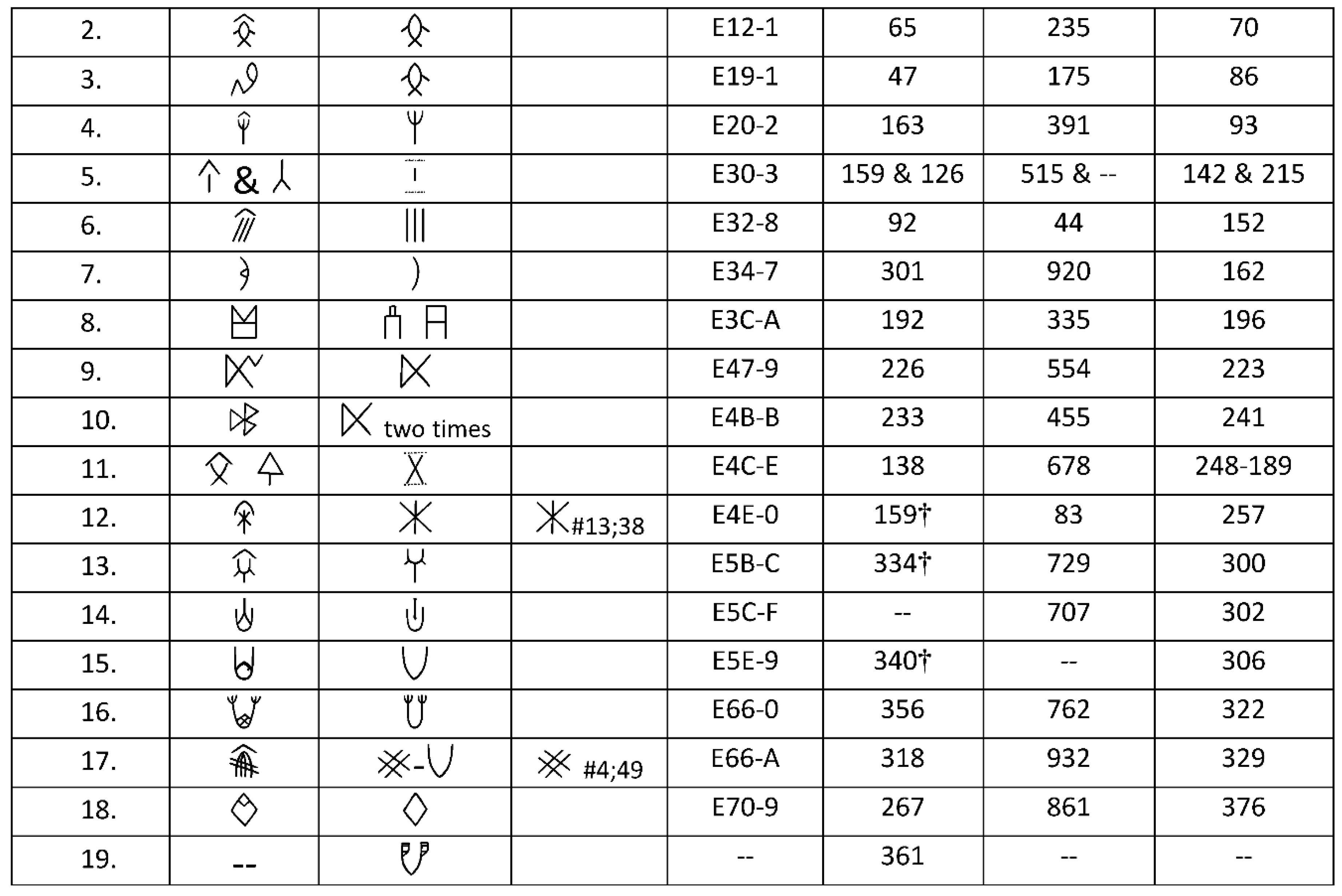

Figure 2.

The Compositing Primary Signs in the Compound Signs (Ligatures)

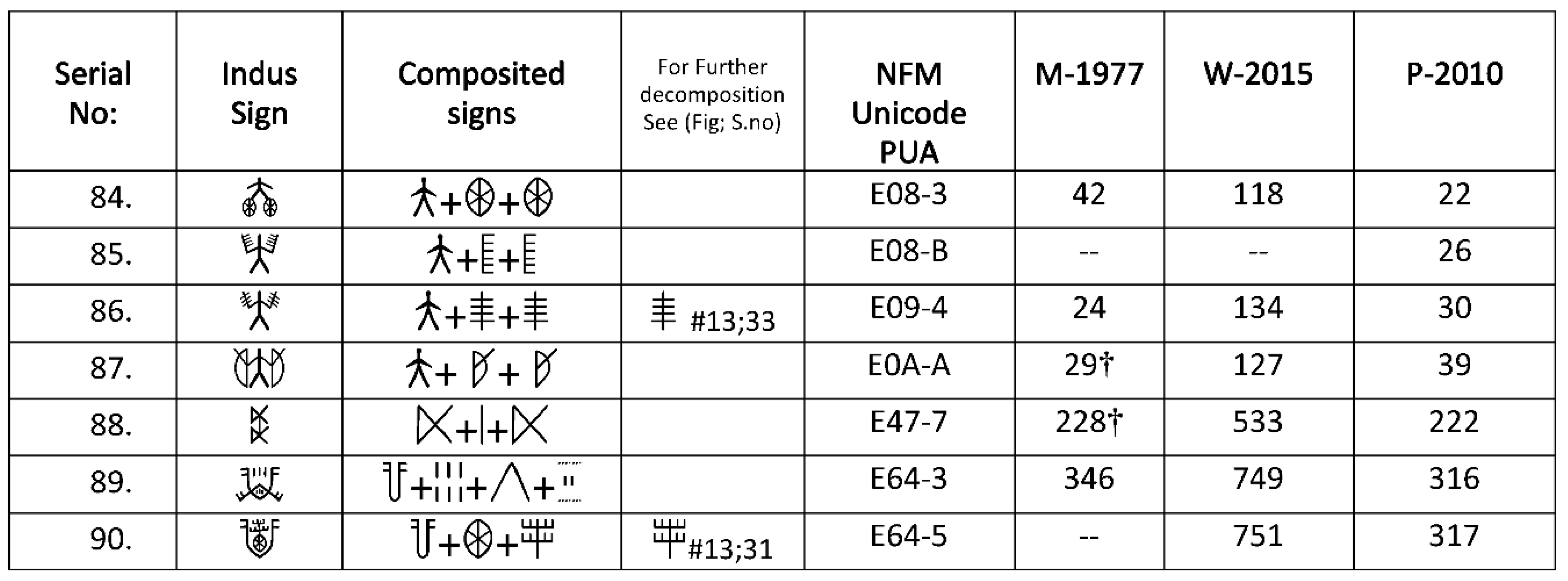

Currently, the identified number of compound signs is 90; however, it is important to acknowledge that this count may increase as further research is conducted. These compound signs are formed by combining two or more basic or primary signs in their composite forms. The process of compositing involves merging individual phonemes to create a unified unit. Ligatures are employed for various purposes, including enhancing aesthetics, improving readability, and efficiently representing frequently occurring combinations of allographs.

Within the compound signs, the compositing process brings together phonemes, which are the smallest meaningful units in the Indus writing system. This amalgamation can take different forms, such as merging allographic shapes or combining constituent parts. By integrating these individual components, compound signs establish a harmonious connection between the allographic variations of basic phonemes, resulting in a visually cohesive written representation. It is worth noting that the process of combining elements within the Indus script gives rise to a significant total of 330 distinct Brahmi signs solely for the 33 consonants, without considering the conjuncts. Therefore, it is not surprising that the Indus script comprises approximately 400 signs, with many of them undergoing similar modifications observed in Brahmi (Kak, 1994).

The decomposition of compound signs has been conducted with meticulous care and consideration. It is important to recognize that compound signs should not be viewed as merely compressed versions of individual basic signs found in the Indus texts. This is primarily due to the infrequent occurrence of the constituent basic signs appearing as sign sequences. Even in the few instances where the components of a compound sign do appear in certain combinations within the text, the context in which the compound sign is used and the context of the sequence formed by its constituent basic signs are significantly distinct (Yadav et al., 2010). Through meticulous observation and examination, the basic or primary signs have been isolated and identified.

Some examples of the variation in the combining technique of the same primary signs:

Figure 3.

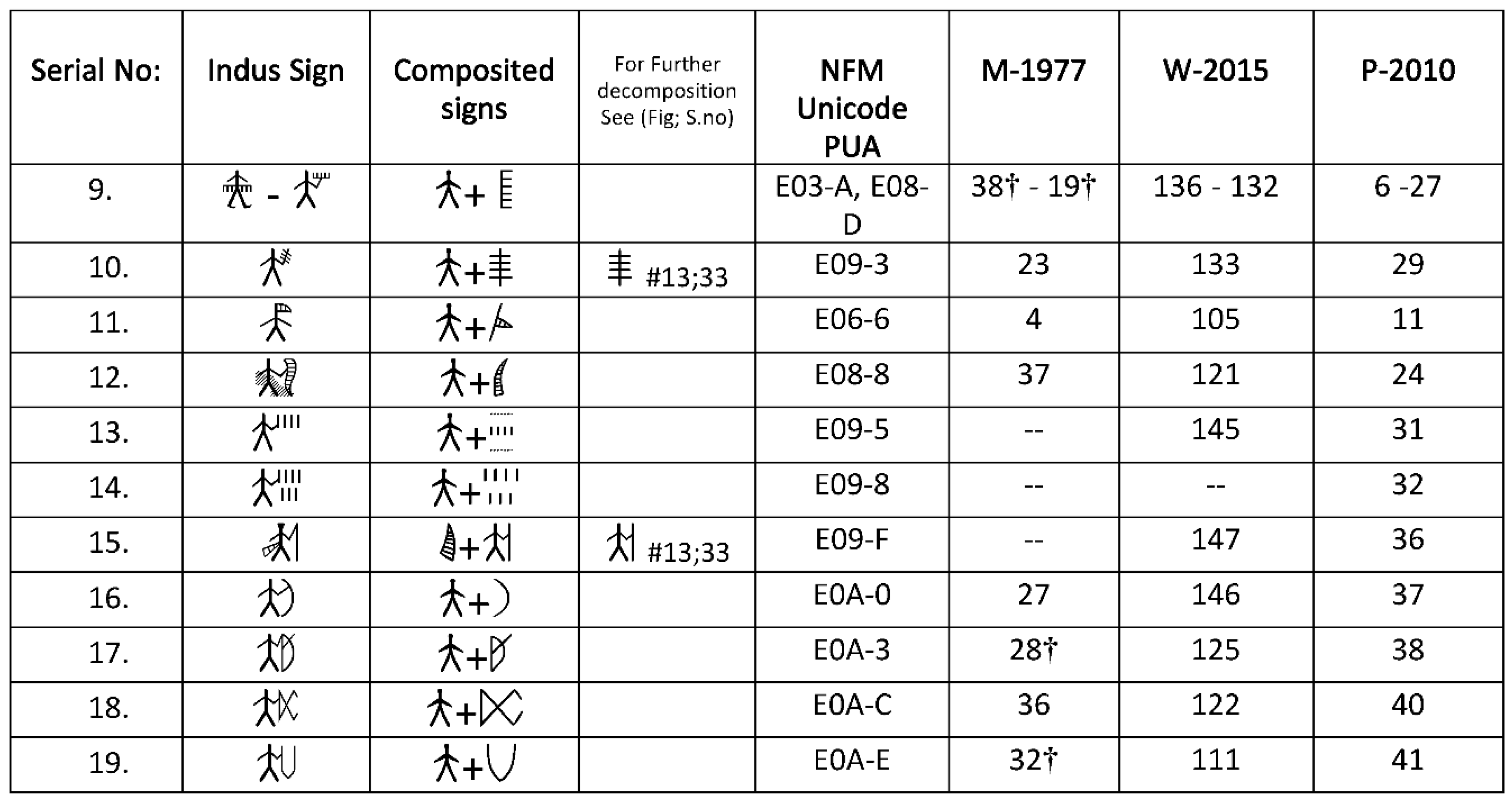

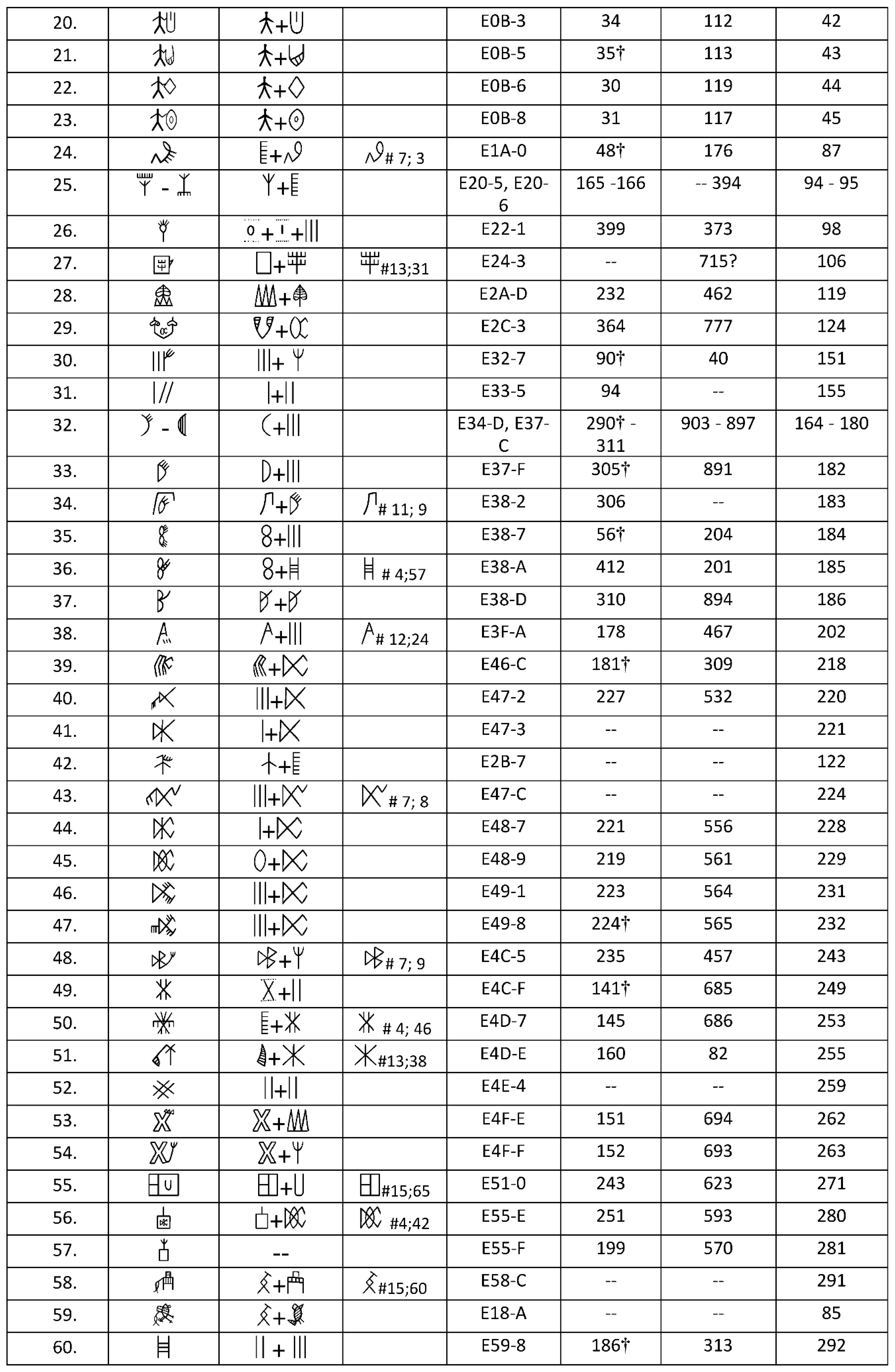

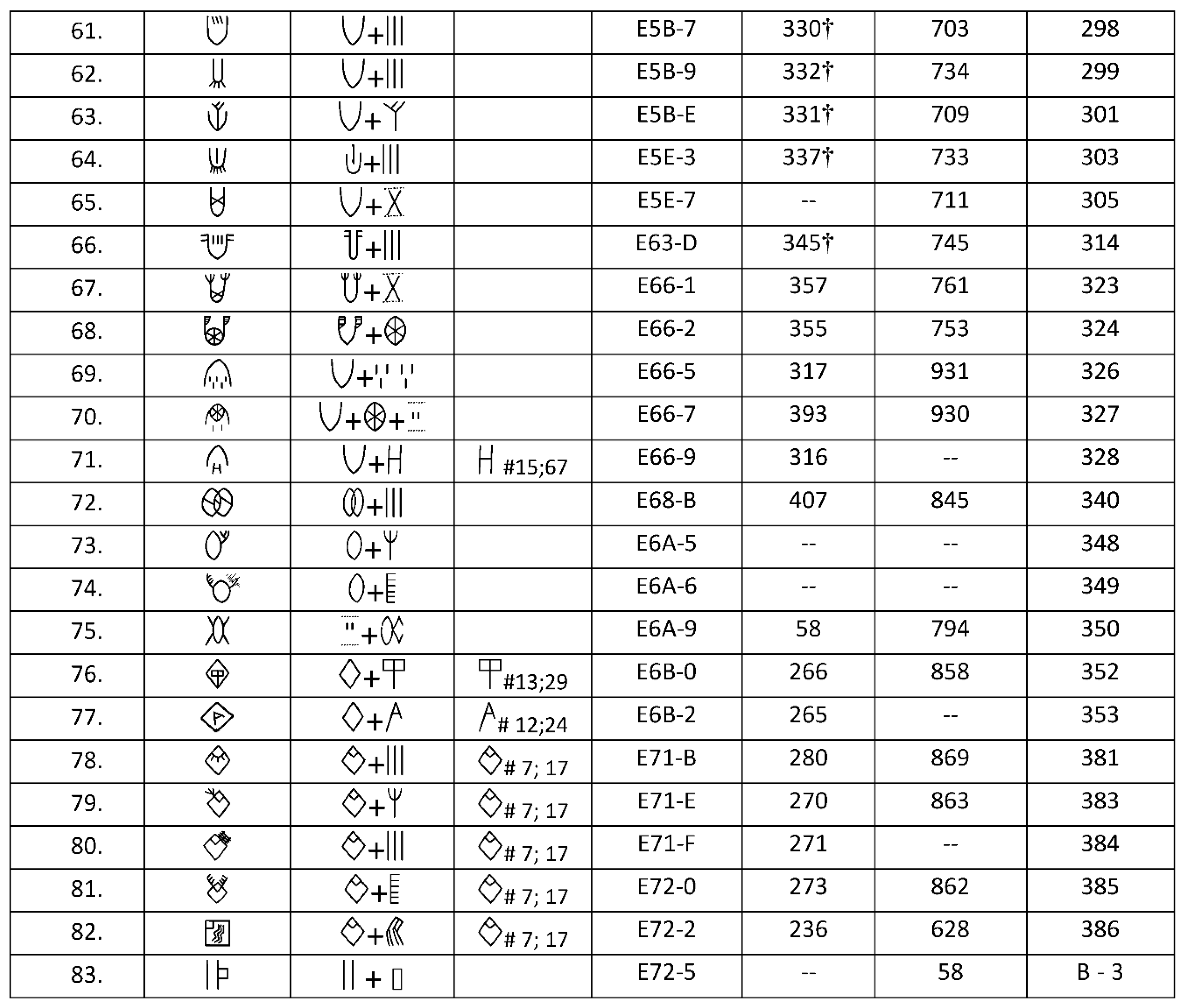

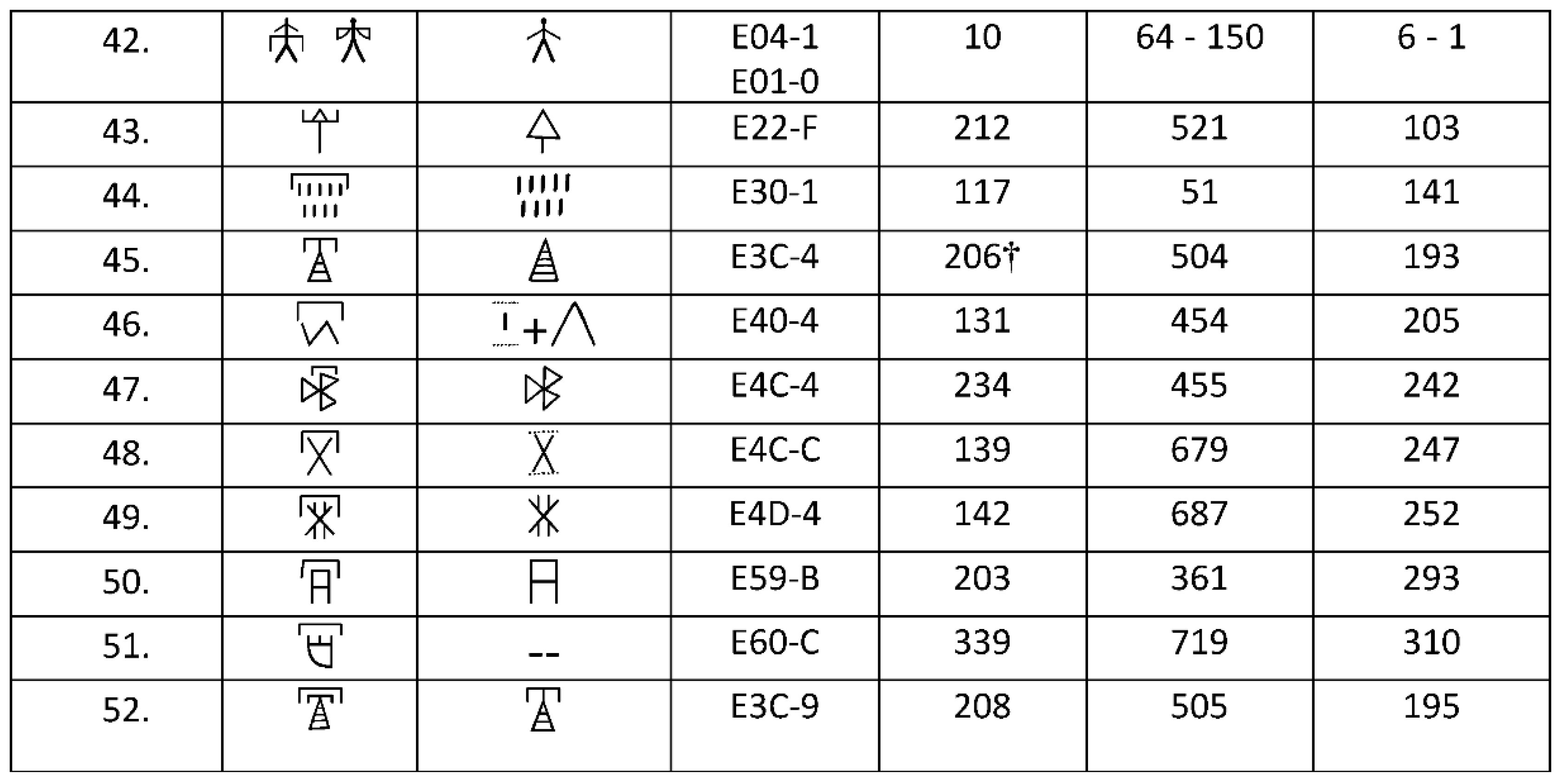

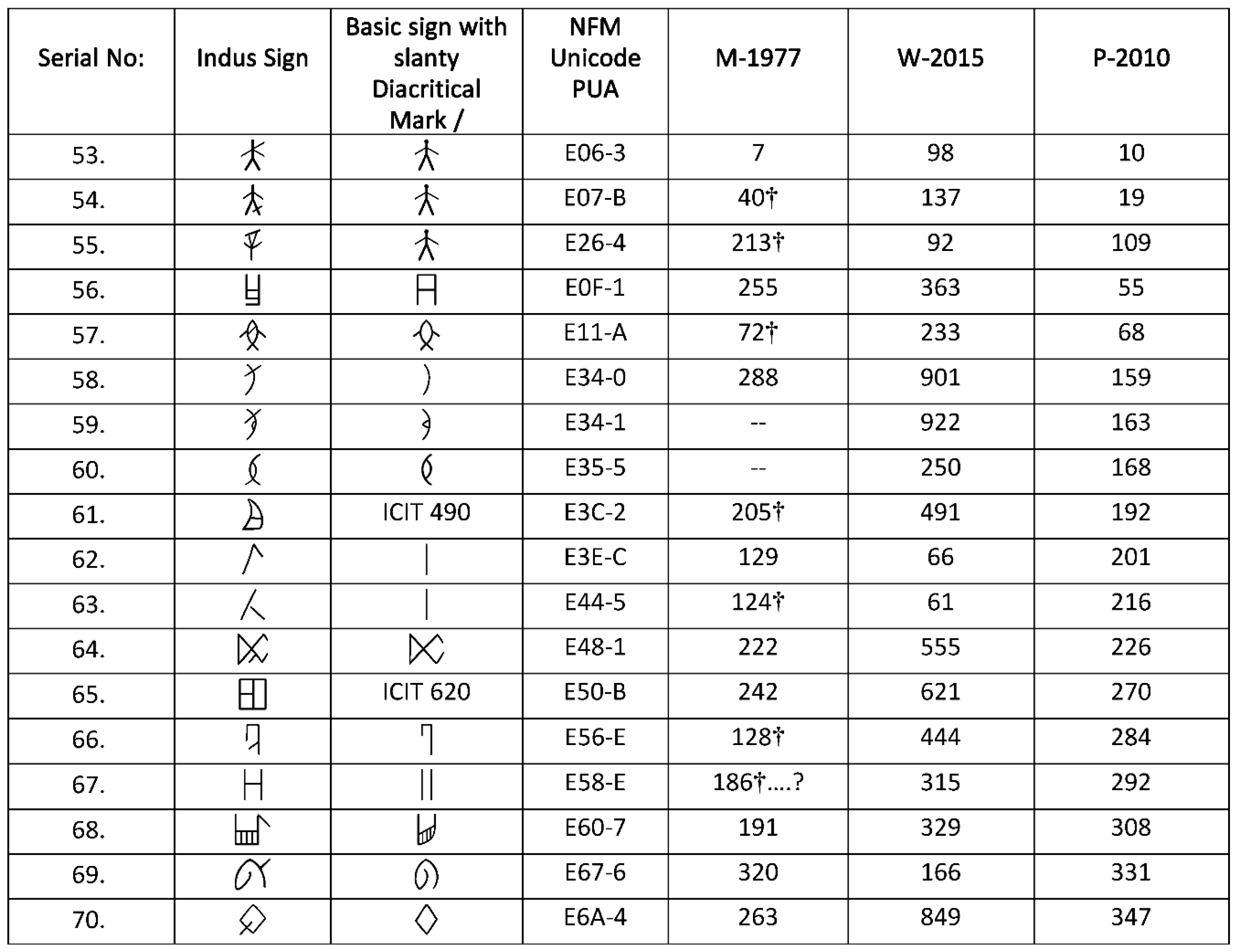

List of the decomposed combined or ligature signs.

Figure 3.

List of the decomposed combined or ligature signs.

Figure 4.

List of the Compound signs contains two or more compositing signs.

Figure 4.

List of the Compound signs contains two or more compositing signs.

Figure 5.

List of the Compound signs contains double or more compositing signs .

Figure 5.

List of the Compound signs contains double or more compositing signs .

Figure 6.

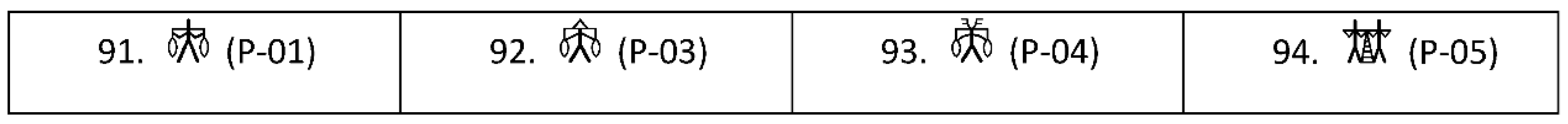

These signs are discussed well in the topic logographic sign Pati. (Muhammad, 2023).

Figure 6.

These signs are discussed well in the topic logographic sign Pati. (Muhammad, 2023).

Excluding the sign P-05 that has used only one time in the texts, the usage of the rest three signs with the same signs indicates the possibility of having the same value despite having some allographic variation:

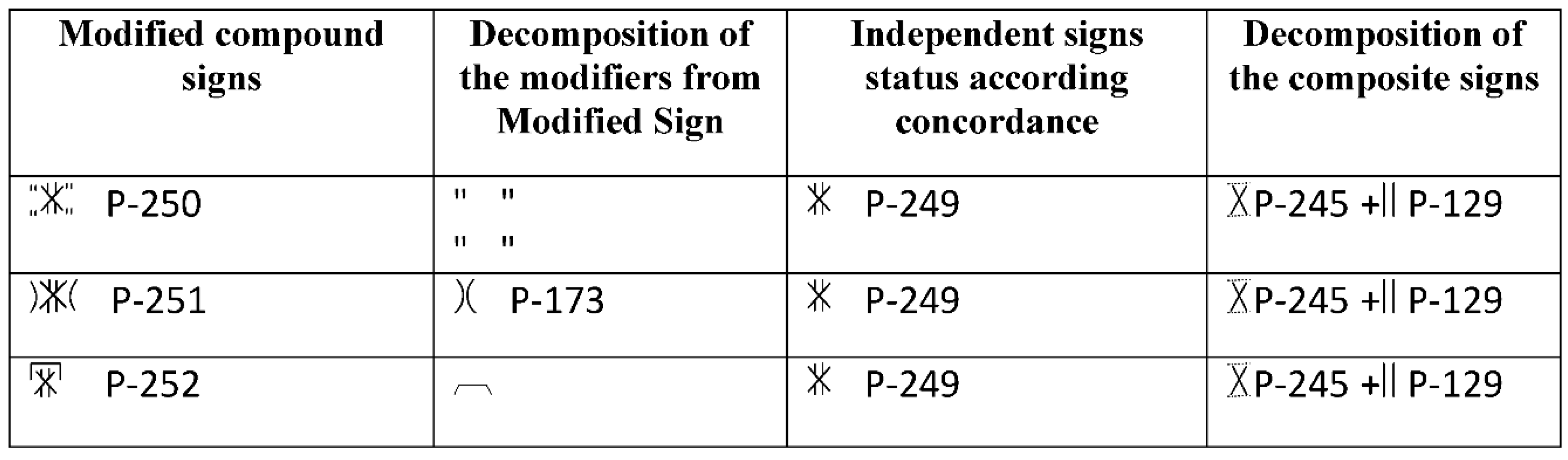

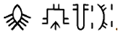

The Three Principal Modifiers

After careful observation and analysis, it is evident that the addition of three specific signs serves to modify the basic signs in order to introduce phonetic variations and enhance the character's value within the alphabet. The following three lists present the modified signs, each list incorporating different modifiers. These modifiers are consistently applied in diverse ways, resulting in variations in sign design. Through a meticulous examination of these signs, it has been identified the consistent use of modifiers with different signs. This recognition provides valuable insights into the compositional process of applying modifiers to basic signs.

By conducting a thorough analysis and inspecting the overall structure of the signs, I have isolated three distinct modifiers based on their design across various variations. These modifiers have been intelligently utilized with the signs. Consequently, the application of these modifiers has varied depending on the allographic design of the basic sign.

The wedge Symbol

The frequent addition and usage of the sign indicate that,

although it is found in only nineteen signs and does not exhibit any specific

pattern of usage with a particular group of signs, careful observation reveals

its consistent usage across various groups of signs. Additionally, it is also

observed in conjunction with other signs that are not explicitly mentioned in

the (

Figure 4) extracting sign process

but they all included in the following list. Therefore, it can be speculated

that this sign potentially contributes to variations in the phonetic value of

each character in the alphabet. The usage of the sign is primarily associated

with the primary sign. The general behavior is its

usage on the top of the signs;

other

variation style of employing according to the needs of design of basic signs

.

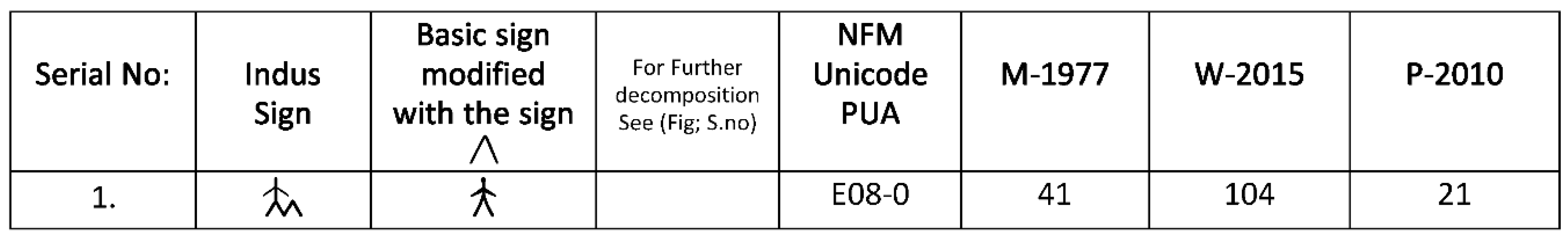

Figure 7.

List of the modified signs with the modifier sign

P-200.

Figure 7.

List of the modified signs with the modifier sign

P-200.

It is important to note that the sign

P-358 has not

been classified as a primary sign. However, there are substantial reasons and

evidence suggesting similarities in formation and usage to later archaic

scripts, particularly Brahmi. Therefore, it has been tentatively included as

part of the sign list in Table 04, for

speculative purposes.

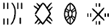

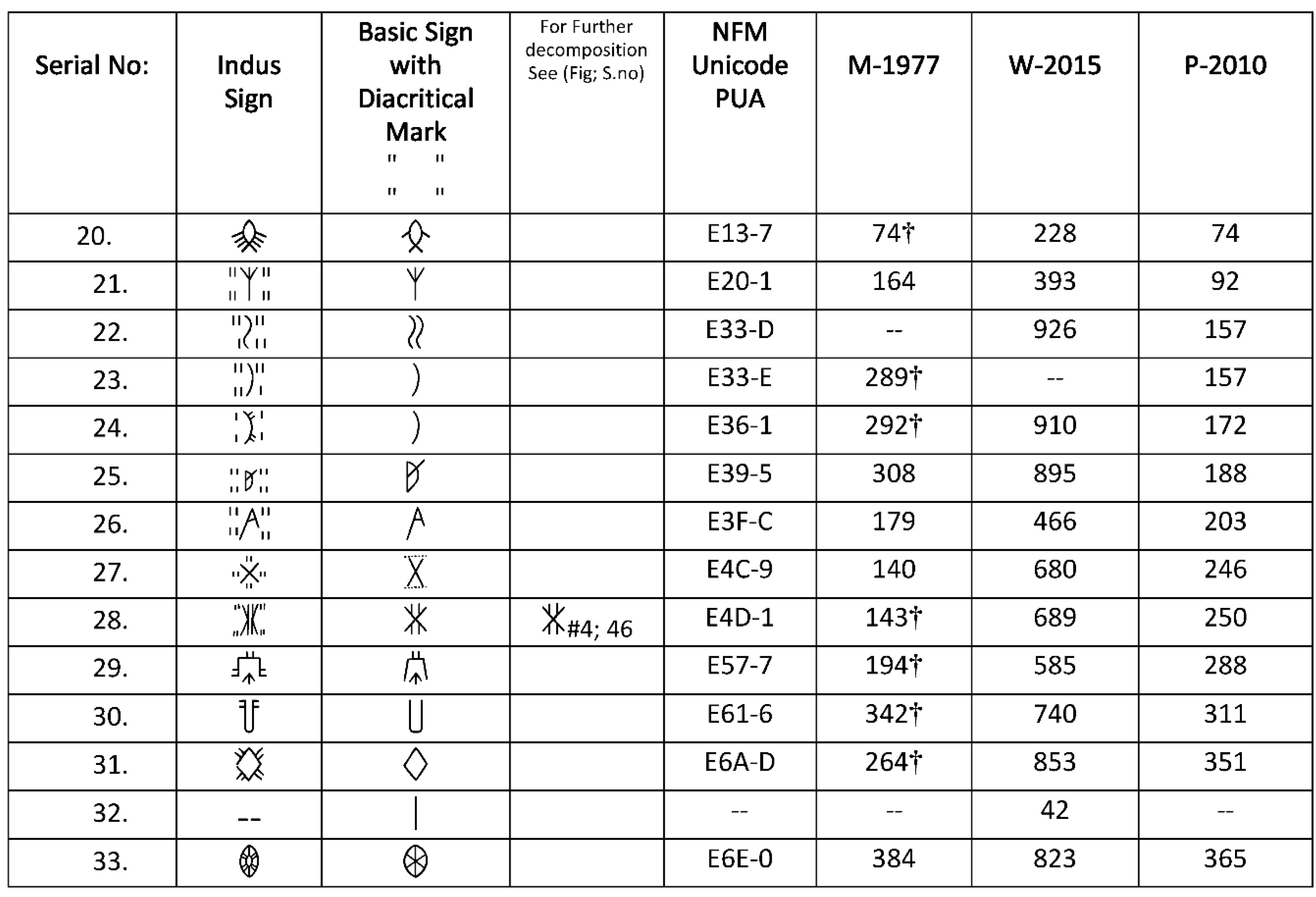

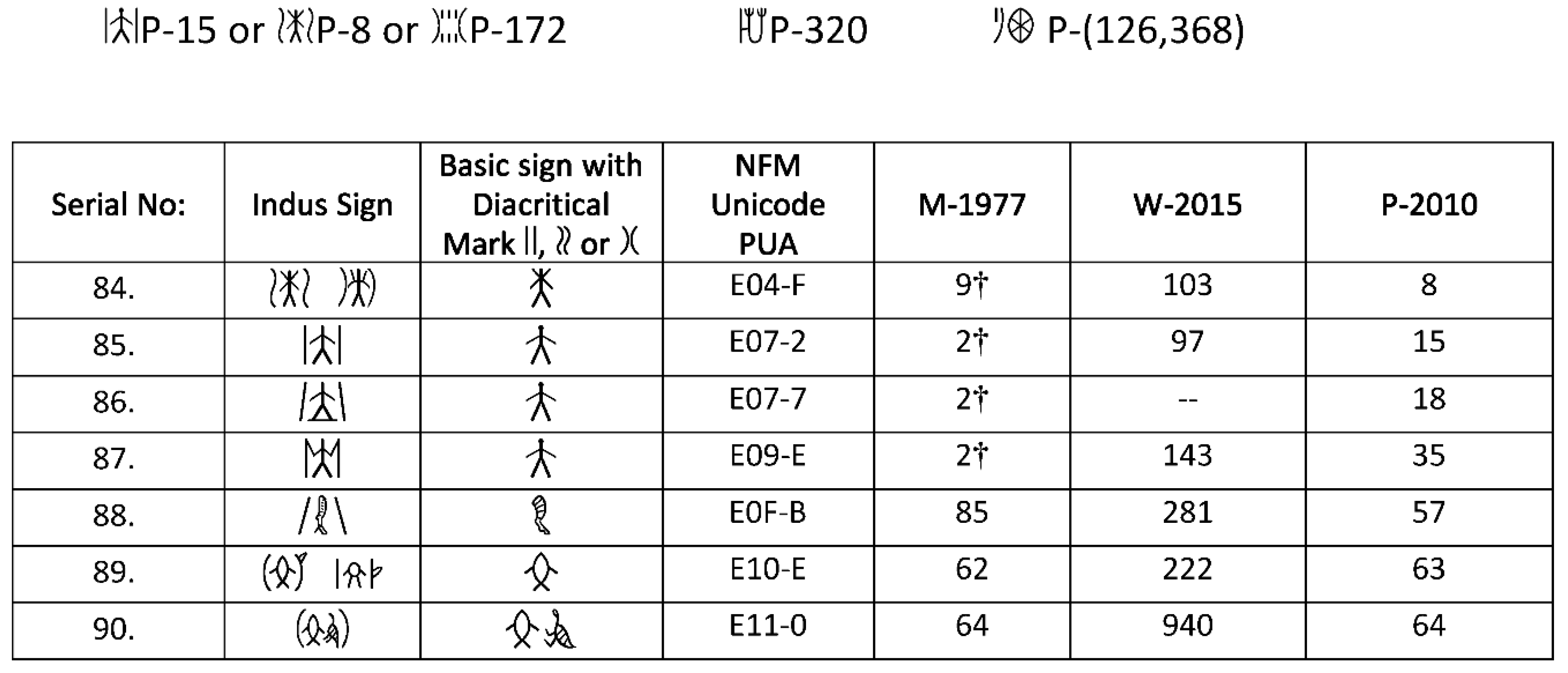

Two Equal Signs and Four Inclined

The usage of two equal signs or the double use of the sign

P-127 as a modifier can be observed with signs P-(74, 172, 311, and 288).

Furthermore, there are four inclined stroke signs that may function as

modifiers and can be seen in association with 18 different basic, modified, combined

or two independent single signs, such as the sign

and

. Upon careful analysis, it

becomes apparent that the inscriber or engraver occasionally attempted to

combine both the two equal signs and the four inclined strokes into a double

inclined modifier sign. For instance, the sign P-172 was merged into P-157, albeit

with one stroke missing. This practice can also be observed in other signs,

including P-92 or P-351. It appears that the two equal signs modify the value,

while the inclined signs may serve different functions, as indicated by their

simultaneous usage on the two basic signs. These observations suggest that such

modifications do not necessarily alter the significance or value of the

individual primary signs.

The independent form of the inclined sign can be

represented by the signs W-14 and M-105, while its singular form is denoted by

W-12 and M-101. The application of the two equal signs as a modifier appears to

be a common practice to modify the primary sign, as seen in the example

.

However, when attempting to use both the equal signs and inclined signs

simultaneously, the engraver deviates from the typical implied approach of the

sign, resulting in variations such as

. Nonetheless, the general

concept of the design is maintained.

Figure 8.

List of the modified signs with equal signs marks.

Figure 8.

List of the modified signs with equal signs marks.

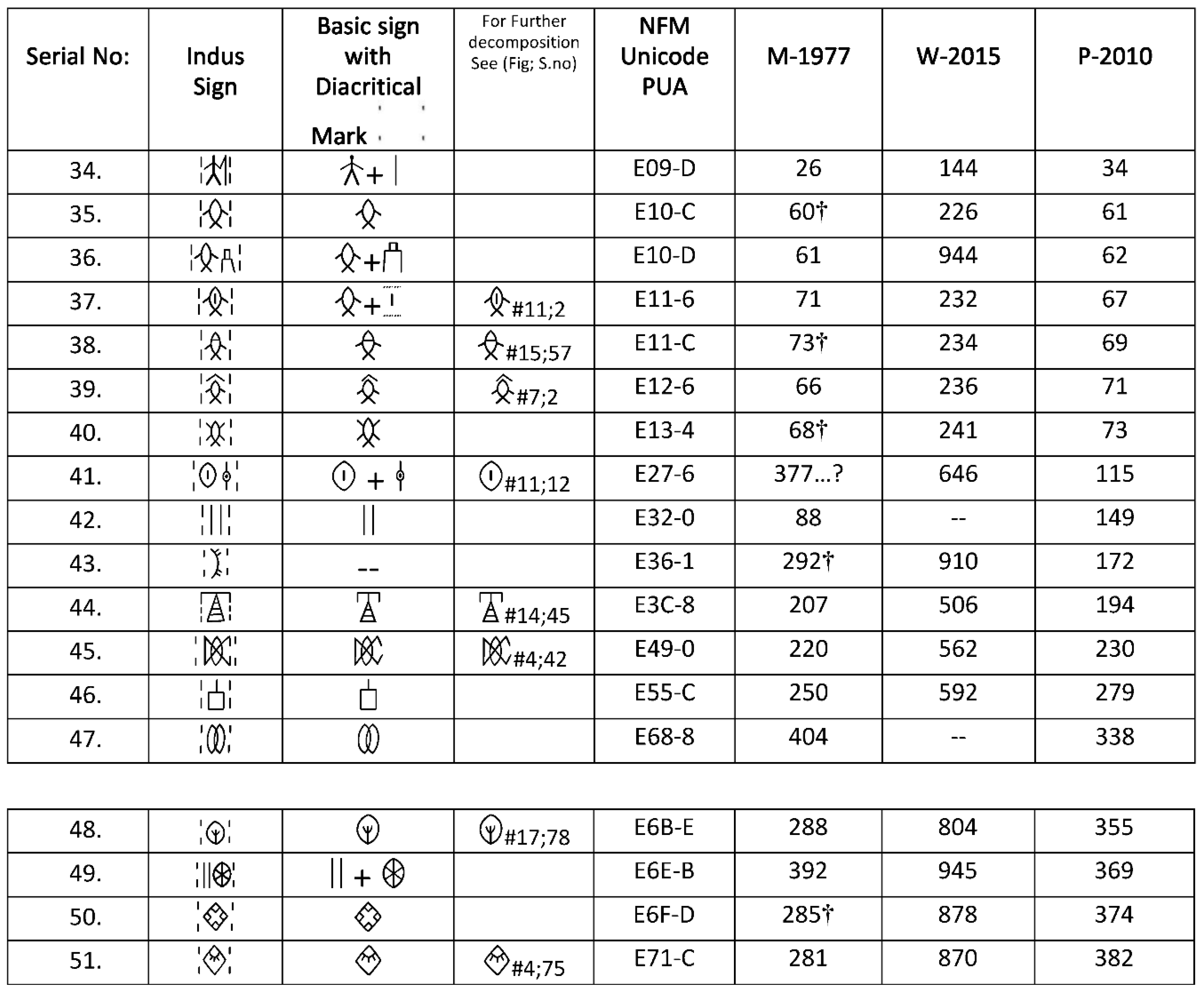

Figure 9.

List of the modified signs with the

inclined marks

.

Figure 9.

List of the modified signs with the

inclined marks

.

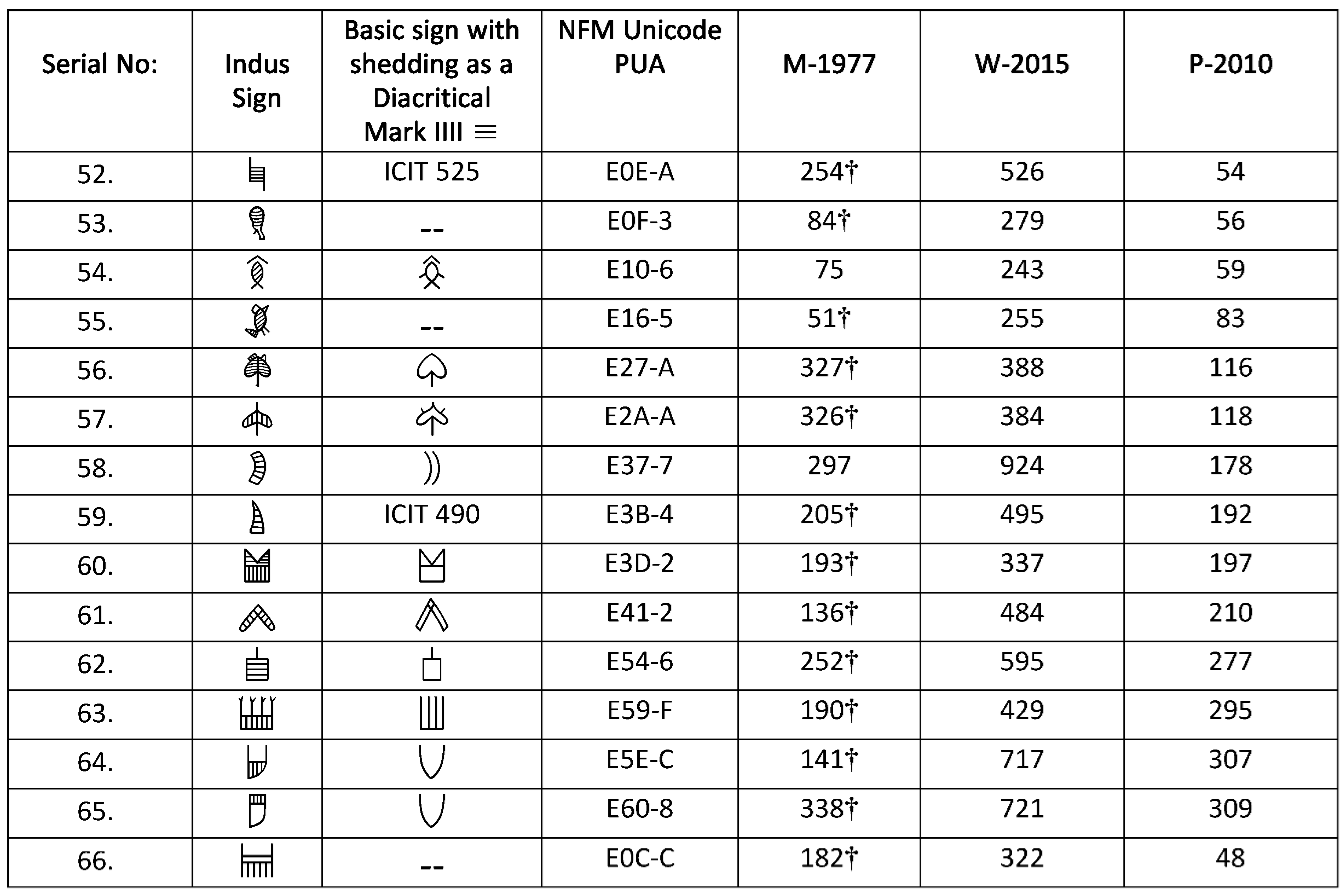

The horizontal and vertical lining or shedding

The observational analysis of the basic signs suggests

that both shedding techniques may serve different functions in terms of adding

phonetic variations. However, it is important to note that this discussion is

not directly relevant to the purpose of classification or decomposition. As a

result, the signs with both horizontal and vertical elements are presented

together in the same table, regardless of their potential phonetic differences.

IIII or

≣:

The vertical and horizontal shedding may have different functions as

according to the general behavior in the usage in the texts but sometimes the

engraver drops the strictness;

.

Figure 10.

List of the modified signs with the inside horizontal and vertical lining or shedding marks IIIIIII/≣.

Figure 10.

List of the modified signs with the inside horizontal and vertical lining or shedding marks IIIIIII/≣.

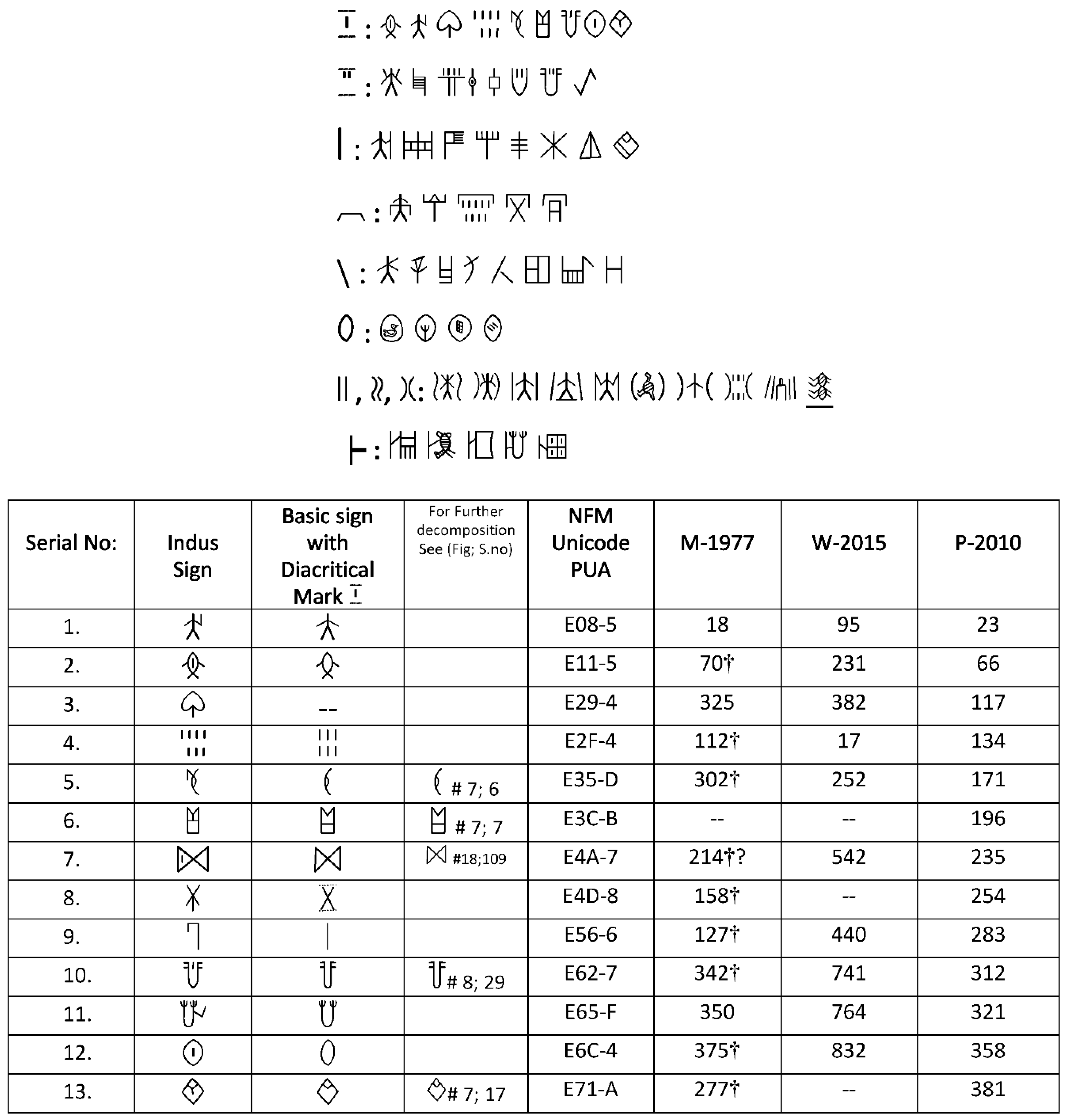

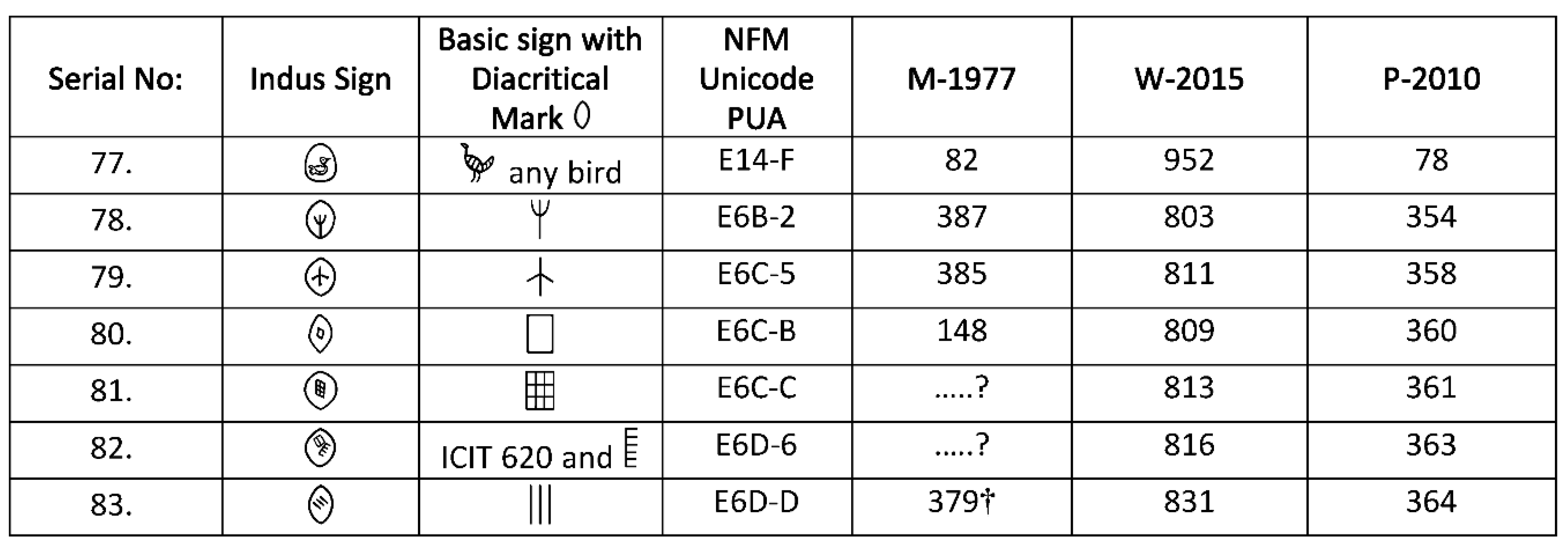

The diacritical marks

After conducting a meticulous analysis and comprehensive examination of the signs presented in the following tables, it has been determined that there are eight distinct diacritic marks with unique design variations. These diacritics have been consistently and thoughtfully applied to the basic signs throughout the script. Importantly, the design of the basic sign influences the ways in which these diacritic marks are employed, leading to variations in their allographic appearance. Consequently, the inclusion of diacritic marks not only modifies the primary signs but also transforms them into distinct signs. It is also worth noting that four of these diacritics are independently used within the script.

The engraver varies the applying style of the diacritics according the design of the primary signs accordingly:

Figure 11.

List of the modified signs with the

diacritical mark

P-128.

Figure 11.

List of the modified signs with the

diacritical mark

P-128.

Figure 12.

List of the modified signs with the diacritical mark

P-127.

Figure 12.

List of the modified signs with the diacritical mark

P-127.

Figure 13.

List of the modified signs with the

diacritical mark

P-147.

Figure 13.

List of the modified signs with the

diacritical mark

P-147.

Figure 14.

List of the modified signs with the diacritical mark ︹.

Figure 14.

List of the modified signs with the diacritical mark ︹.

Figure 15.

List of the modified signs with the diacritical mark \ .

Figure 15.

List of the modified signs with the diacritical mark \ .

Although the diacritic mark mentioned below has a distinct formation from the previously discussed slanty sign, the usage of both signs in the Indus texts exhibits similarities on many seals. Based on this observation, it has been included as the same diacritic mark as mentioned above.

Figure 17.

List of the modified signs with the diacritical mark

P-341.

Figure 17.

List of the modified signs with the diacritical mark

P-341.

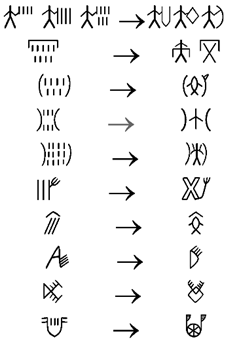

The signs II

P-129-148, P-173, and P-175 have been classified as distinct signs not only by

Parpola but also by Mahadevan and Wells. However, there are examples from the

texts that suggest these signs may be variations of the same sign.

Additionally, all three signs have been used as diacritical modifiers in a

similar manner, alongside the primary sign. Although no examples from the Indus

Texts are provided here, the mentioned variative use of diacritical signs with

the same primary sign supports the notion that they are likely the result of

the engraver's writing style rather than representing a distinct form or

separate signs. Another modifier,

P-126, which is not

attached to any primary sign but used independently, is not included among the

eight diacritic marks.

Figure 18.

List of the modified signs with the

diacritical marks;

P-129,

P-175 &

P-173.

Figure 18.

List of the modified signs with the

diacritical marks;

P-129,

P-175 &

P-173.

Figure 19.

List of the modified signs with the diacritical mark ┝.

Figure 19.

List of the modified signs with the diacritical mark ┝.

Another Possible Diacritic Mark

Figure 20.

List of the modified signs with the

diacritical marks

P-125 &

P-266.

Figure 20.

List of the modified signs with the

diacritical marks

P-125 &

P-266.

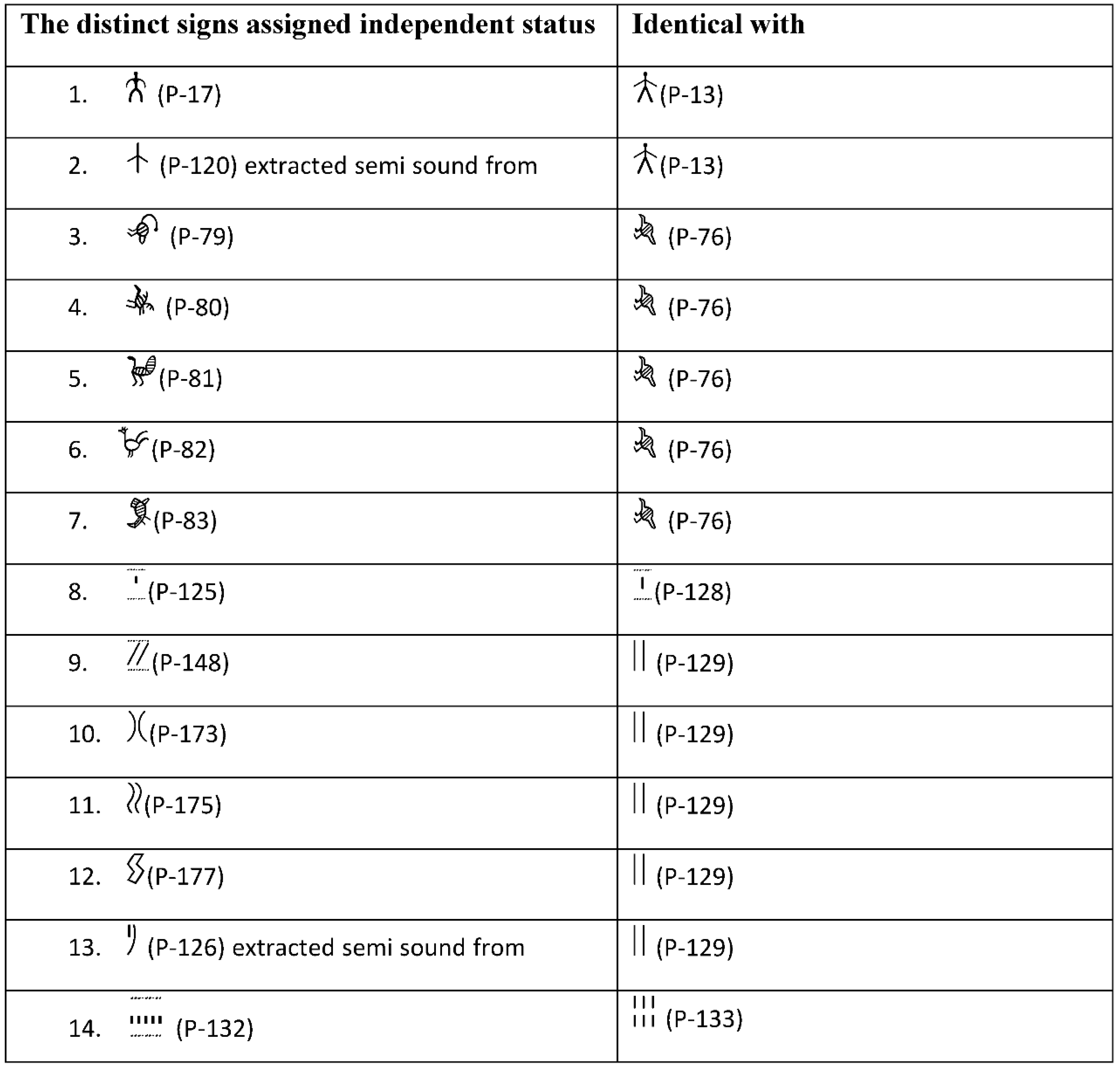

Identical Signs: Contemplating Variations in Engraving Styles and the Perception of Distinct Signs

However, it should be noted that Parpola has identified these signs as distinct ones and has even assigned separate identity numbers to them. While my perception about the signs mentioned below is that they are actually identical signs rather than distinct ones. The differences in their formation are minor and can be attributed to variations in writing styles. It is likely that these variations were a result of the engraver's artistic choices, showcasing their versatility in writing.

Figure 21.

List of the Identical signs.

Figure 21.

List of the Identical signs.

Exploring the further identical signs in the classification of concordances

Animal Sign: P-46 appears to be an initial engraving practice of the sign P-47. Through a process of evolution or refinement, P-48 emerges as a more developed form. Additionally, P-51 could be regarded as another variation of the aforementioned signs.

Bird Sign: Despite variations in the bird sign, it can still be regarded as the same sign. Considering the diverse engraving styles within the region, it is expected to encounter variations. An example of this can be observed in the animal sign 46, where its evolution can be recognized in sign P-47, ultimately leading to the development of sign P-48. However, this pattern does not appear to be present in the bird sign. Nevertheless, in some inscriptions, sign P-83 shows characteristics that suggest it may be a developed form of the bird sign. Furthermore, all bird signs, namely P-76, P-77, P-78, P-79, P-80, P-81, and P-82, can be classified as the same sign. This classification may also include modified versions such as P-77 and P-78.

Semi Signs: Two additional signs,

P-120 and

P-266,

appear to have been derived from the basic signs

P-13 and

P-270/W-620,

respectively. These signs may represent a semi-phonetic value associated with

the basic signs.

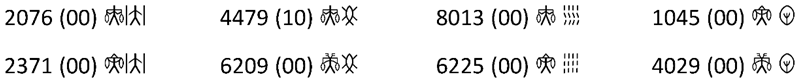

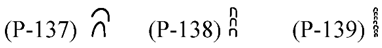

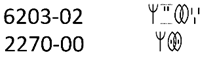

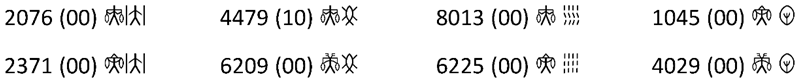

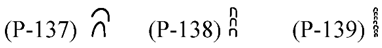

Stroke Signs: There is a widely held belief that stroke signs primarily serve as numerical indicators, implying their association with numbers. However, previous studies have overlooked an important aspect: their usage. Upon careful investigation and observation of stroke signs, it becomes apparent that they are not merely used in a manner similar to other primary signs, but they also undergo modifications akin to other primary signs. This argument suggests that stroke signs should be regarded as a type of primary sign rather than being exclusively tied to numeral values. Indeed, while it is true that examples of the usage of each modifier or diacritic with available signs are not available, there are instances where certain modifiers and diacritics are employed in a manner similar to other primary signs. These examples provide compelling evidence that undermines the previous assumption and suggests that stroke signs may have a broader function beyond being solely numeral indicators.

Here are a few instances of stroke signs that undergo modifications or modify in a manner similar to other primary or core signs:

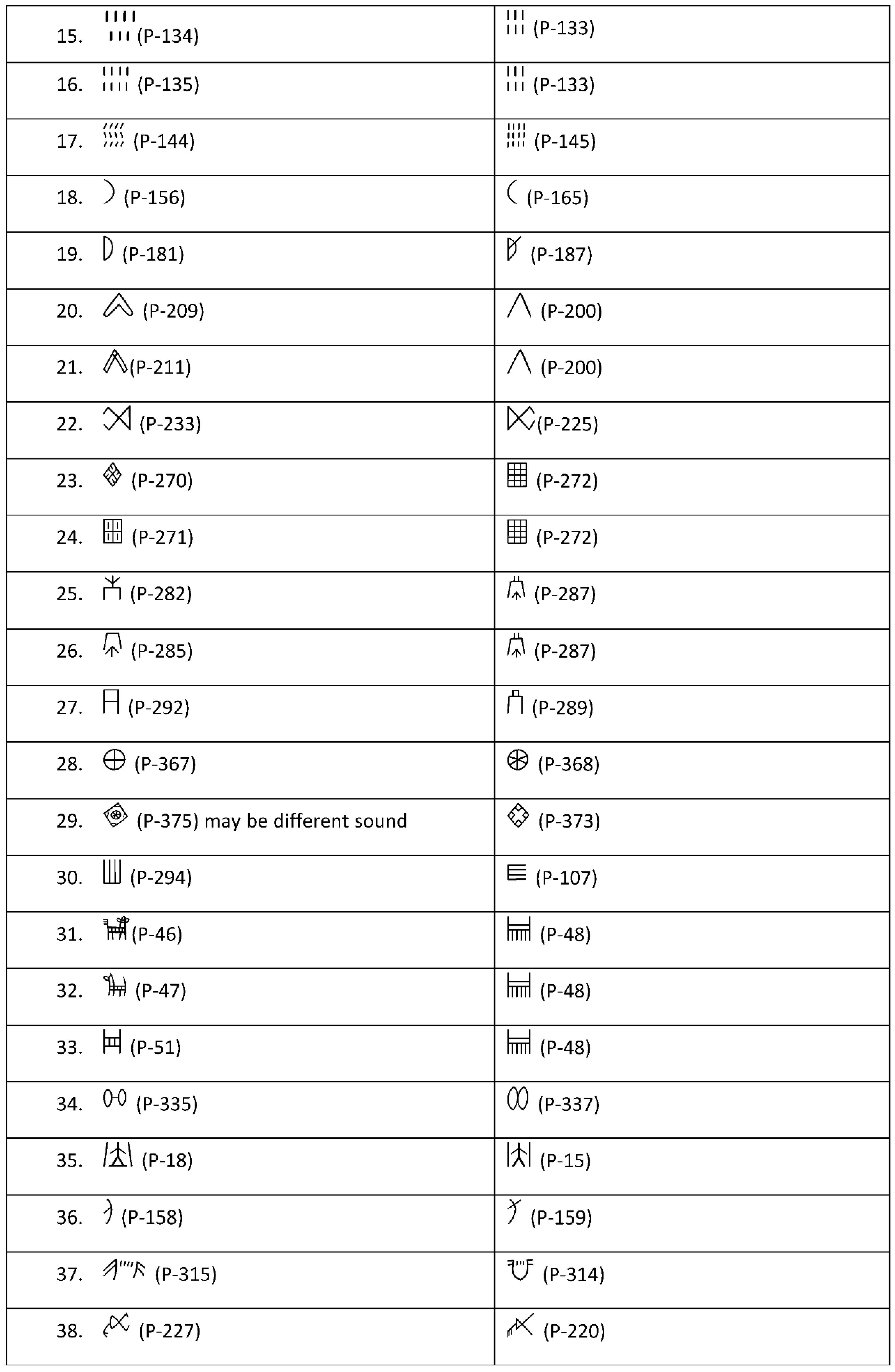

The three signs P-130, consisting of long and short strokes, are frequently encountered. While these signs undoubtedly have different values, they often appear confused in many inscriptions due to their size. The signs P-137, P-138, and P-139 can be seen as evolutionary experiments on the style of short-stroked signs. This influence can be observed in later alphabetic scripts;

Despite the distinct functions and phonetic values of signs P-130, P-133, P-135, and P-145, the inscriptions suggest that the number of strokes is not the primary concern of the engraver. However, it is observed that a minimum of three strokes is necessary for representing the sign., the signs M-89†, M-95, and P-130, P-131, and P-153 are all identical and have been used interchangeably in numerous texts. There may be slight differences in interpretation between these signs, for example:

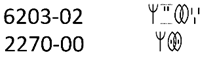

In addition to the mentioned stroked signs, there are other examples worth noting. The sign consisting of five long strokes, M-96 and P-132, can be contrasted with the sign of five short strokes, which appears to represent a writing variation. On the other hand, there are other signs with five strokes that yield the same value, such as M-186 and P-292. Furthermore, there are two rare signs with two vertical short strokes, namely M-101 and W-12, which are not included in Parpola's sign collection. and appear only once in a specific text (1903-00). They can be considered variants of M-99, M-100, P-127.

Variations in writing style can be observed in the below texts for the signs M-103† and P-143.

The common Indus text exhibits a consistent usage of different numbers of short strokes as a form of writing variation. While there may be slight differences in pronunciation, the examples below illustrate this phenomenon; These variations in the number of short strokes contribute to the richness and diversity of the Indus script.

In the case of the sign P-202, there is a notable practice of varying the number of strokes in its different variations and styles. This demonstrates the flexibility and adaptability of the Indus script. The specific examples showcasing these variations in stroke count within the sign P-202 are as follows:

Indeed, the variations in stroke count within signs such as P-202 suggest that the number of strokes is not strictly regulated in the Indus script. Instead, it appears to be influenced by the engraver's individual choices and stylistic compositions. This flexibility in stroke count adds further complexity and diversity to the script, allowing for diverse artistic variations within the writing system.

and

and signs:

signs: Parpola has

already classified as the same to all variations of the signs M-161, M-162†,

M-167†, and M-169† into a single sign, namely P-91. Building upon Parpola's

suggestion, I further support this classification, that this is a difference of

the engraving style rather considering them distinct signs.

The wedge or leaf like symbols: The sign M-134, P-200, or W-480 is frequently used as a modifier sign. This sign appear to be related to M-135, M-136, M-323, M-325, M-326, P-117, P-118, P-209, P-210, P-211, P-212, W-380, W-382, W-383, W-384, W-385, W-482, W-483, and W-484. The variations among these signs primarily involve differences in writing style and the addition of diacritical marks or other modifications.

Squire and oval or circular signs: It is noteworthy that Mahadevan and Parpola have not distinguished the difference between two major signs, namely and . However, in Wells' collection, these signs are recognized as separate and distinct signs.

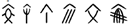

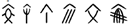

Inverting the position of the primary signs: The inversion of primary signs reveals a notable degree of flexibility. It is observed that the positioning of these signs can vary, depending on the engraver's artistic style and their consideration of spatial constraints. Importantly, this inversion does not alter the phonetic value of the sign and does not indicate a distinct form of the primary sign. Several examples illustrating this phenomenon are provided below:

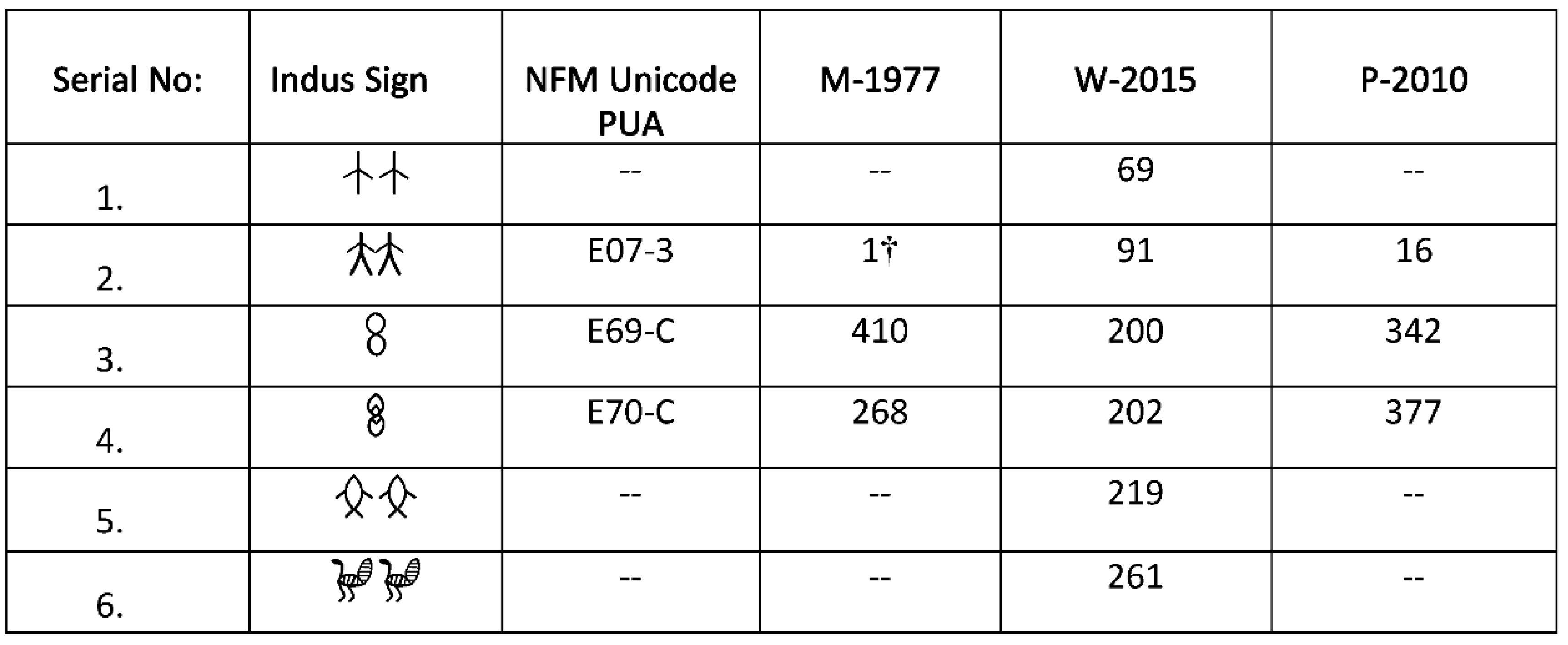

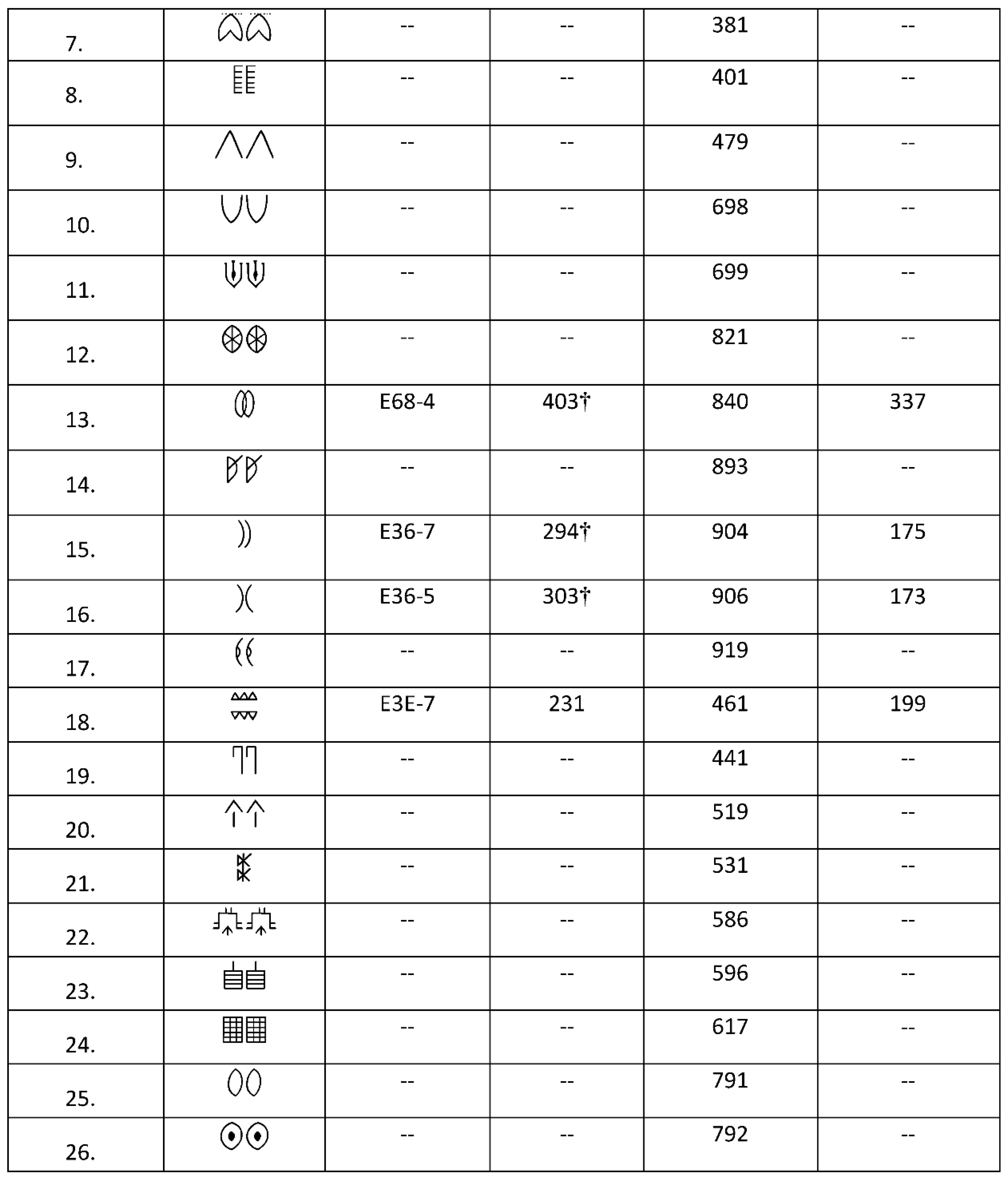

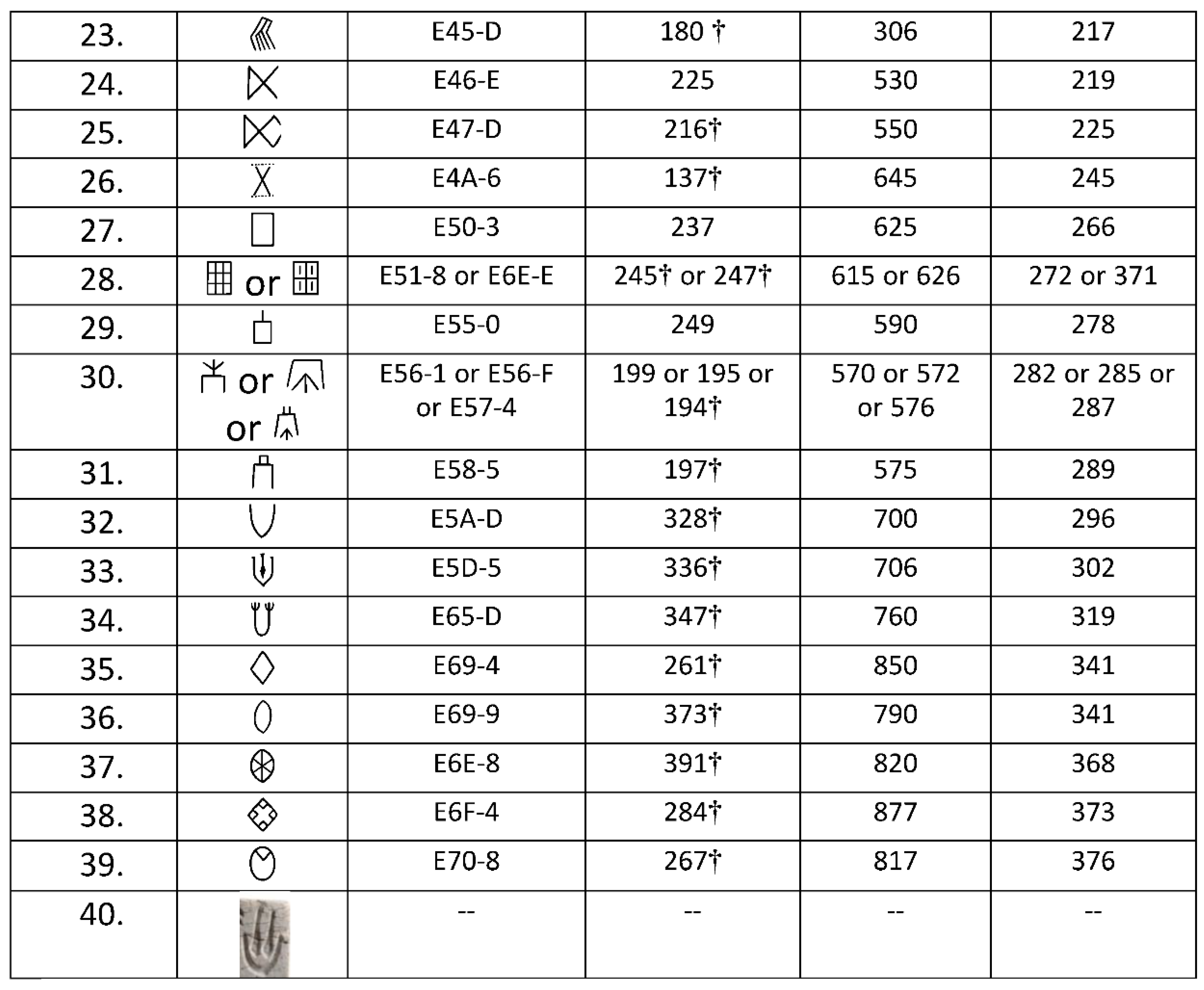

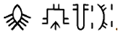

The Paired Primary Signs

In M-77, 30 pairs of signs have been identified. Wells has classified all of them as independent signs in his sign collection. However, only some of these pairs have been given the status of independent signs in the sign collections of Mahadevan and Parpola.

Figure 22.

List of the paired signs.

Figure 22.

List of the paired signs.

Unaddressed signs: These engravings appear to be uncommon, with a low frequency of occurrence. As a result, it is challenging to justify their significance at this time. While there may be speculative justifications, it would be more prudent to withhold judgment until further research is conducted, comparing the texts and related inscriptions. Therefore, I refrain from addressing these signs for the time being, as their determination requires further investigation and analysis.

Figure 23.

List of the unaddressed signs.

Figure 23.

List of the unaddressed signs.

The Final determination of the Primary Signs:

In conclusion, the classification of primary or core signs follows a systematic approach that involves categorization and recognition of these fundamental signs. The primary criteria for this classification are their formation and design. Attempts to visually decompose these signs into smaller components have proven to be ineffective or impractical. Instead, the classification and identification of basic signs rely on their formation and design as the primary basis. Further decomposition of these signs does not seem to be applicable. It is important to note that these basic signs are often used in their simplest form, without any further breakdown. This highlights the significance and integrity of these signs as basic phonemes of the alphabet.

Figure 24.

The List of Basic or Primary Signs.

Figure 24.

The List of Basic or Primary Signs.

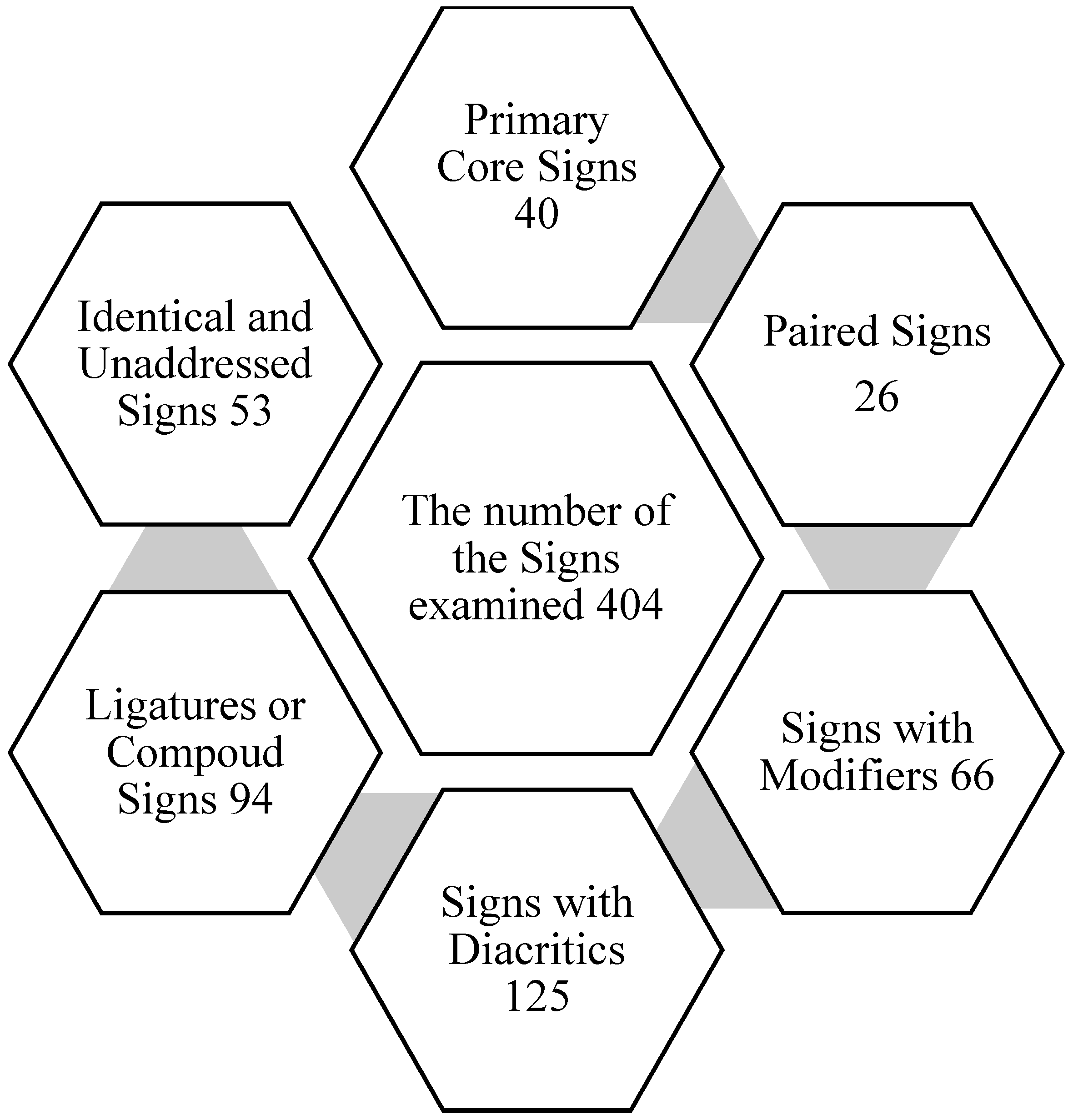

Examined Signs

Parpola's exhaustive compilation of 391 signs has been subjected to meticulous scrutiny in order to attain a comprehensive understanding of their design, mechanisms, and variations in writing style. In instances where further elucidation was required, thorough investigations were conducted. Furthermore, the signs from Wells and Mahadevan's updated collections have been integrated into the study, resulting in a collective examination of over 404 signs. It should be noted that certain signs have been individually discussed and excluded from the figures.

Notwithstanding any counterarguments pertaining to the decomposition of specific signs, the concept of the Indus script as an alphabetic writing system remains robust. This comprehensive approach enables us to acquire valuable insights into the actual number of Indus signs and their specific applications, thereby reinforcing the notion of considering them as an alphabet with a high degree of certainty.

Figure 25.

The

classification of the sign collection of Parpola.

Figure 25.

The

classification of the sign collection of Parpola.

other

variation style of employing according to the needs of design of basic signs

other

variation style of employing according to the needs of design of basic signs  .

. P-200.

P-200.

P-358 has not

been classified as a primary sign. However, there are substantial reasons and

evidence suggesting similarities in formation and usage to later archaic

scripts, particularly Brahmi. Therefore, it has been tentatively included as

part of the sign list in Table 04, for

speculative purposes.

P-358 has not

been classified as a primary sign. However, there are substantial reasons and

evidence suggesting similarities in formation and usage to later archaic

scripts, particularly Brahmi. Therefore, it has been tentatively included as

part of the sign list in Table 04, for

speculative purposes. and

and  . Upon careful analysis, it

becomes apparent that the inscriber or engraver occasionally attempted to

combine both the two equal signs and the four inclined strokes into a double

inclined modifier sign. For instance, the sign P-172 was merged into P-157, albeit

with one stroke missing. This practice can also be observed in other signs,

including P-92 or P-351. It appears that the two equal signs modify the value,

while the inclined signs may serve different functions, as indicated by their

simultaneous usage on the two basic signs. These observations suggest that such

modifications do not necessarily alter the significance or value of the

individual primary signs.

. Upon careful analysis, it

becomes apparent that the inscriber or engraver occasionally attempted to

combine both the two equal signs and the four inclined strokes into a double

inclined modifier sign. For instance, the sign P-172 was merged into P-157, albeit

with one stroke missing. This practice can also be observed in other signs,

including P-92 or P-351. It appears that the two equal signs modify the value,

while the inclined signs may serve different functions, as indicated by their

simultaneous usage on the two basic signs. These observations suggest that such

modifications do not necessarily alter the significance or value of the

individual primary signs. .

However, when attempting to use both the equal signs and inclined signs

simultaneously, the engraver deviates from the typical implied approach of the

sign, resulting in variations such as

.

However, when attempting to use both the equal signs and inclined signs

simultaneously, the engraver deviates from the typical implied approach of the

sign, resulting in variations such as  . Nonetheless, the general

concept of the design is maintained.

. Nonetheless, the general

concept of the design is maintained.

.

.

.

.

P-128.

P-128.

P-127.

P-127.

P-147.

P-147.

P-341.

P-341.

P-126, which is not

attached to any primary sign but used independently, is not included among the

eight diacritic marks.

P-126, which is not

attached to any primary sign but used independently, is not included among the

eight diacritic marks. P-129,

P-129,  P-175 &

P-175 &  P-173.

P-173.

P-125 &

P-125 &  P-266.

P-266.

P-120 and

P-120 and  P-266,

appear to have been derived from the basic signs

P-266,

appear to have been derived from the basic signs  P-13 and

P-13 and  P-270/W-620,

respectively. These signs may represent a semi-phonetic value associated with

the basic signs.

P-270/W-620,

respectively. These signs may represent a semi-phonetic value associated with

the basic signs.

and

and signs: Parpola has

already classified as the same to all variations of the signs M-161, M-162†,

M-167†, and M-169† into a single sign, namely P-91. Building upon Parpola's

suggestion, I further support this classification, that this is a difference of

the engraving style rather considering them distinct signs.

signs: Parpola has

already classified as the same to all variations of the signs M-161, M-162†,

M-167†, and M-169† into a single sign, namely P-91. Building upon Parpola's

suggestion, I further support this classification, that this is a difference of

the engraving style rather considering them distinct signs.