1. Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), comprising Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), is characterized by repetition of relapse leading to a disabling course or bowel surgery. The latter is particularly common in CD. Because teenagers and young adults are most frequently affected, relapse prevention and maintenance of remission is of paramount importance.

Biologics became available more than 25 years ago, and they revolutionized therapy in medicine including IBD [

1]. Biologics are generally indicated for cases unresponsive to conventional therapies in IBD. Biologics are effective for induction and maintenance of remission and reducing hospitalization and surgery in IBD [

2,

3,

4,

5]. The use of biologics is increasing. In Europe, biologics are used in 69.7% of patients with CD and 43.5% of patients with UC [

6]. In addition, because early use of biologics is more effective than a late use, there is a tendency toward earlier use of biologics after diagnosis from years to months [

1,

7].

Infliximab, anti-tumor necrotizing factor (TNF) α, was the first biologic utilized in IBD [

1]. Among biologics, infliximab is most frequently used, followed by adalimumab, vedolizumab, and ustekinumab [

6]. Therefore, there are a lot of data on infliximab. Induction therapy with infliximab is standardized: three infusions (5 mg/kg) at 0, 2, and 6 weeks. Responders subsequently receive scheduled maintenance therapy every 8 weeks [

1]. This modality is the same for both CD and UC. However, there are limitations. A proportion of patients (10%-40%) are primary nonresponders to infliximab [

8], and secondary loss of response is seen in some patients during the maintenance phase. The latter occurs in 30-46 % of CD patients within 1 year, and the majority of these patients (50-70%) regain response with dose intensification, i.e., dose escalation and/or shortening the interval between infliximab infusions [

9]. Failure to regain a response leads to withdrawal of maintenance therapy.

Efficacy and adverse reactions are always a concern with use of a new drug in a patient. Although there are new medications such as biologics and small molecules, no medication for definite induction in all patients is available. There is a barrier of primary nonresponders to biologics as described above [

8]. The net remission rates calculated based on remission rates in the induction and maintenance phases are less than 35% at around 1 year for biologics including infliximab, adalimumab, ustekinumab, and vedolizumab in CD [

10]. Therefore, doctors want to continue effective medication(s) as long as possible.

IBD occurs in genetically susceptible individuals triggered by an environmental factor(s) in wealthy societies. But to date there has not been a widely appreciated ubiquitous environmental factor. Our prior research has suggested a strong association between a westernized diet and IBD [

11,

12]. A westernized diet is characterized by increased consumption of animal fat, animal protein, and sugar with decreased consumption of carbohydrates [

13]. Therefore, we advise all newly diagnosed patients to be admitted and to experience a plant-based diet (PBD) (lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet) to counter omnivorous western diets [

14]. Outcomes of our modality incorporating PBD surpassed current standards in both CD and UC in both the induction and quiescent phases [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Based on our outcomes together with recent findings in epidemiology, nutrition, microbiology, immunology, and multi-omics studies, we were the first to recommend PBD for IBD in the literature [

19,

20,

21,

22].

There are no reports in the literature of scheduled maintenance therapy in IBD with a modality incorporating PBD. There are no criteria for evaluating the efficacy of maintenance therapy with infliximab. Some researchers regarded the dose intensification as relapse [

23]. There are difference in criteria for the starting dose intensification among researchers: appearance of abnormal biomarker(s) with or without symptoms. The former is conventionally recognized as relapse and the latter is not. As stated above, doctors and patients want to continue taking effective medication(s) as long as possible. Because biologic agents are pretty expensive, infliximab is immediately withdrawn upon judging it to be ineffective. From these, it seems appropriate that outcomes of infliximab maintenance therapy can be assessed based on the durability of maintenance therapy. The aim of this single group study was to investigate the durability of scheduled maintenance therapy with infliximab incorporating PBD. This modality was found to yield a longer durability compared to current standards.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Settings

We designed a single-group, non-randomized, open, non-control trial, which was conducted at Akita City in northern Japan. This city has a population of 315,000 individuals. Both Nakadori General Hospital and Akita City Hospital are tertiary care hospitals in Akita city. MC, the first author, worked for the former between 2003 and 2012 and has been working for the latter since 2013. The study protocol was registered at

www.umin.ac.jp (Clinical trial registration: UMIN000019061, UMIN000020335, and UMIN000020402).

2.2. Patients

Based on our assertion that IBD is a lifestyle disease mediated mainly by a westernized diet, all patients with IBD were advised to be admitted once to experience a PBD and to learn how to combat this lifestyle disease. Because the majority of CD patients are destined for a clinical course of disability, and because glucocorticoid therapy for severe UC, the current standard first-line therapy, is unsatisfactory, we provided infliximab and a plant-based diet as first-line (IPF) therapy for these cases [

15,

17]. Infliximab monotherapy without immunomodulators was used only in the induction phase and was not continued in the quiescent phase. The details and outcomes of IPF therapy have been described previously [

15,

17,

18]. Relapsed cases after successful induction with the IPF therapy were eligible for infliximab maintenance therapy. Clinical remission with C-reactive protein (CRP) levels above the reference range (≤0.3 mg/dL until March 2013, ≤0.19 from April 2013 to March 2017, ≤0.14 after April 2017) even after a few months of the induction phase was judged as unstable remission. Patients with unstable remission and patients with a response but not remission were followed with infliximab maintenance therapy. Another indication for the maintenance therapy was UC patients with the chronic continuous type or steroid dependency. Post-bowel surgery CD patients were included for prevention of relapse [

24].

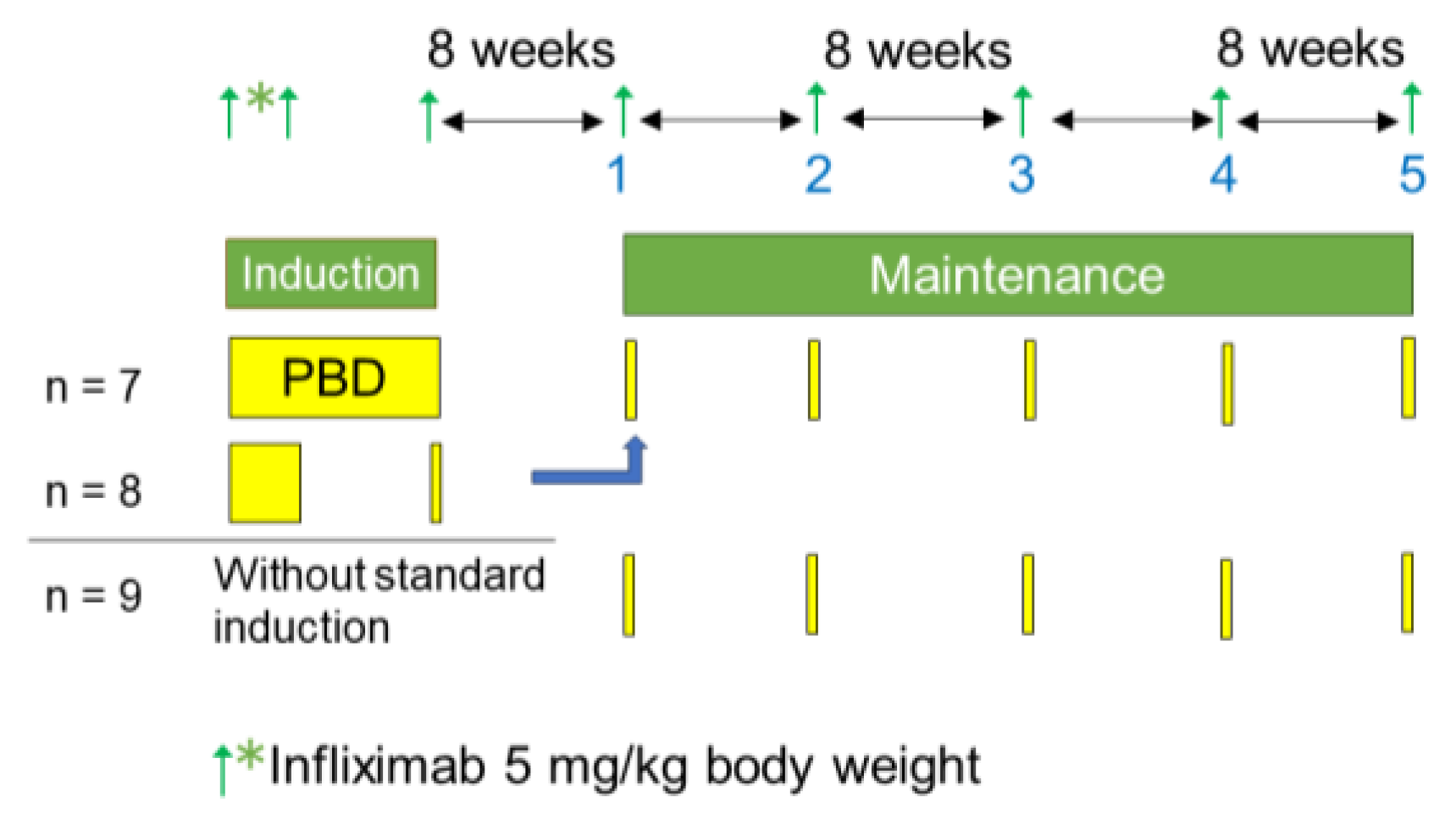

2.3. Protocol: Scheduled Infliximab Maintenance Therapy

Relapsed cases that were either symptomatic or asymptomatic after the IPF therapy were retreated with standard infliximab induction therapy and PBD before the initiation of scheduled infliximab maintenance therapy (

Figure 1). Asymptomatic relapse means active inflammatory findings on endoscopy despite an absence of symptoms. Infliximab (5 mg/kg) was infused at weeks 0, 2, and 6 [

25]. Azathioprine was not co-administered, except for those already on the drug. In cases in the quiescent phase, the maintenance therapy was initiated without the reinduction therapy (

Figure 1).

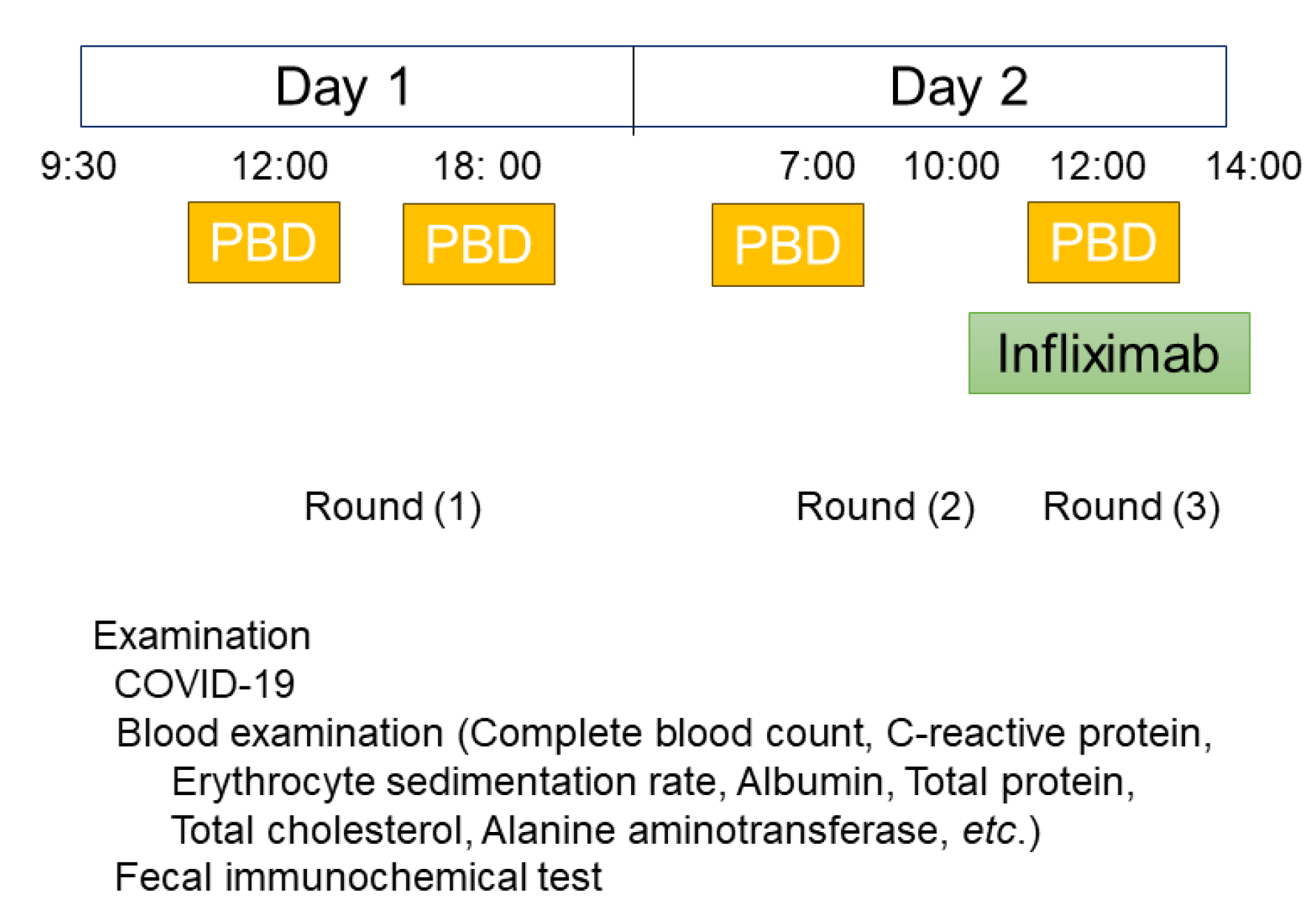

Scheduled maintenance therapy was provided every 8 weeks on an inpatient basis (2-day hospitalization) (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). There were several reasons for inpatient maintenance therapy rather than outpatient therapy in our study. First, it was for safety reasons. Since the introduction of infliximab, immediate adverse drug reactions, infusion reactions to infliximab, have been well known [

25]. With hospitalization, a swift response is possible for unexpected infusion reaction(s) [

26]. Second, inpatient therapy would be a starker reminder to patients of the grave clinical course than outpatient therapy. IBD has been designated an intractable diseases in Japan, and patient medical fees are greatly supported by the national insurance system. The monthly upper limit of copayment for high medical costs is anywhere from free to ¥20,000 depending on annual income (The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan) [

27]. Thereby, doctors can use biologics without serious concern for the patient’s economic burden. Patients with IBD and doctors are to appreciate our nation’s medical system for the great support for medical expenses including biologics. Third, responsible doctor (MC) can assess the condition of patients more accurately by meeting patients more than once. Fourth, the patient’s work colleagues, or the patient’s school would further understand the nature of IBD.

On admission, vital signs and body weight were checked. On the first day, blood tests including complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP, total protein, serum albumin, and liver/kidney function tests were performed. Fecal immunochemical test was also performed. On the second day, infliximab (5 mg/kg body weight) [

25] was infused. During hospitalization, patients ate three meals before COVID-19 and four meals after COVID-19. Before COVID-19, patients were admitted at 2:00 p.m., while after COVID-19, patients were required to come in the morning for a COVID-19 test (

Figure 2). The details of PBD have been described previously [

14]. Briefly, PBD comprised a lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet with fish once a week and meat once every 2 weeks [

14]. Protein, fat, and carbohydrates accounted for 16.1 ± 0.5%, 18.6 ± 1.4%, and 66.1 ± 1.6% of total calories, respectively. PBD contained 32.4 ± 2.1 g of dietary fiber/2,000 kcal (soluble dietary fiber 6.8 ± 0.7 g, insoluble dietary fiber 23.3 ± 1.6 g) [

14]. About 30 kcal per kg standard body weight was provided.

When symptoms appeared with elevated CRP, intensification of infliximab therapy was initiated: an increase in dose most often from 5 to 7.5 mg/kg and/or decrease in infusion interval most often from 8 weeks to 6 weeks.

2.4. Follow-Up Studies

The original scheduled maintenance therapy was continued for asymptomatic patients with normal CRP levels. Intensification of infliximab was applied for symptomatic patients with elevated CRP levels. Scheduled maintenance therapy was discontinued when the intensification failed to regain a response or turned out to be ineffective. Such patients had substantial difficulties in daily life. Change of medication, hospitalization or surgery was needed. The maintenance therapy was also discontinued if a significant adverse event occurred.

Four criteria for termination of infliximab maintenance therapy were set for favorable patients: asymptomatic with consecutive normal CRP and negative fecal immunochemical test for at least for 2 years, in addition to absence of active findings on ileo-colonoscopy.

The duration of maintenance therapy was defined as the time between the first and the last scheduled infliximab infusions.

2.5. Food-Frequency Questionnaire and Plant-Based Diet Score (PBDS)

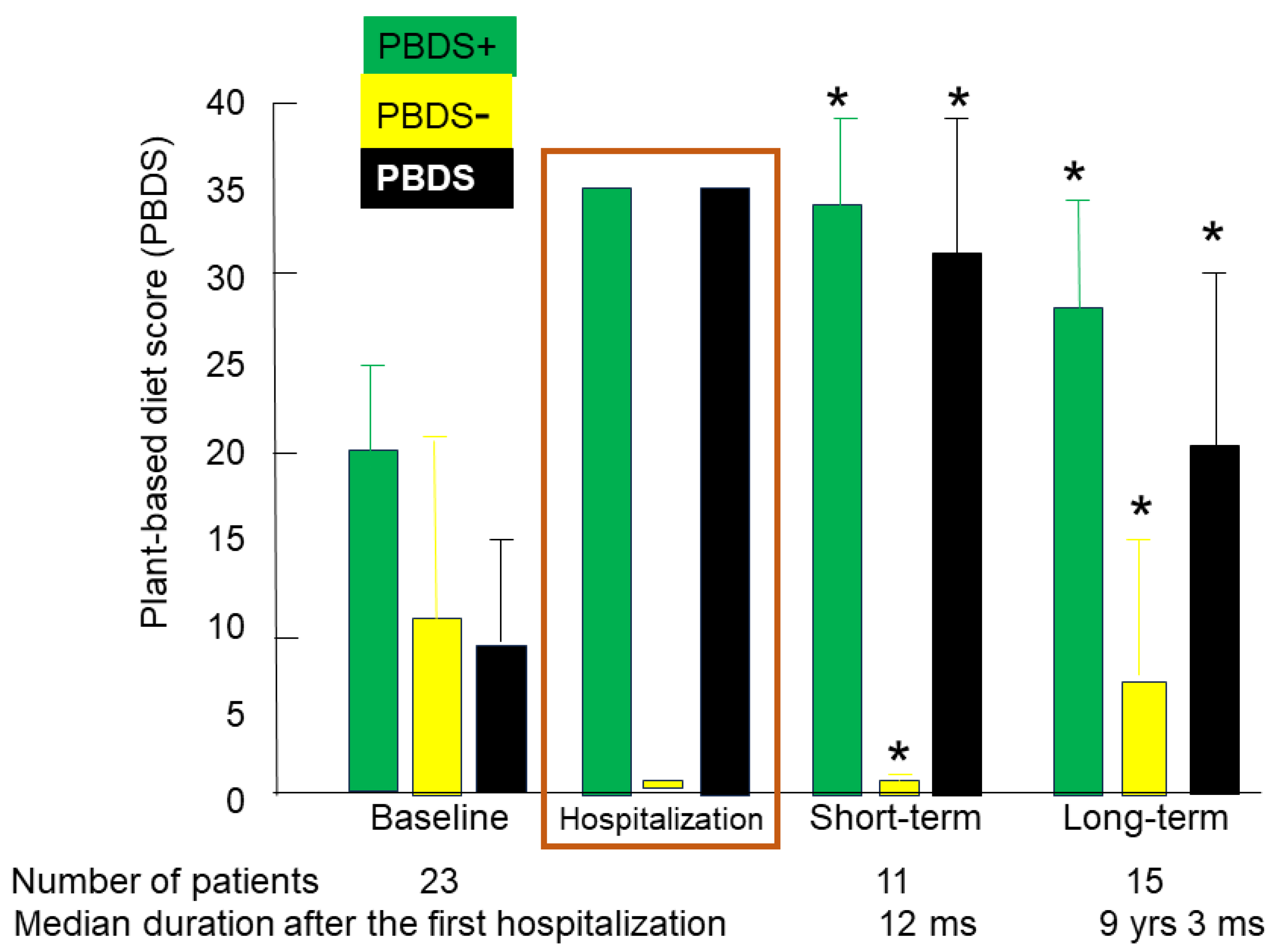

A questionnaire of dietary habits and lifestyle behaviors before onset of the disease was obtained immediately after the first admission, as described in a previous report [

28]. The questionnaire was repeated during short-term (≤2 years) or long-term (>2 years) follow-up. They were designated as baseline PBDS, short-term PBDS, and long-term PBDS, respectively.

PBDS for Japanese IBD patients was calculated from the questionnaire. The method for how the PBDS was calculated has been described previously [

28]. Briefly, eight items considered to be preventive factors for IBD (vegetables, fruits, pulses, potatoes, rice, miso soup, green tea, and plain yogurt) contributed to a positive score (PBDS+), while eight items considered to be IBD risk factors (meat, minced or processed meat, cheese/butter/margarine, sweets, soft drinks/sugar-sweetened beverages, alcohol, bread, and fish) contributed to a negative score (PBDS-). Scores of 5, 3, and 1 were given according to the frequency of consumption: every day, 3-5 times/week, and 1-2 times/week, respectively. The PBDS was calculated as the sum of the positive and negative scores, and it ranged between -40 to +40. A higher PBDS indicated greater adherence to the PBD. The PBDS for the PBD consumed during hospitalization was 35 [

28].

2.6. Assessment of the Efficacy of Scheduled Infliximab Maintenance Therapy Incorporating PBD

The primary endpoint was durability of infliximab scheduled maintenance therapy. The secondary end point was change over time in PBDS.

2.7. Safety Evaluations

Safety assessments included vital signs, patient complaints, findings during doctor and nurses rounds, physical examinations, and the results of blood tests at scheduled visits.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Demographic parameters are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and/or median (interquartile range), as appropriate. Statistical comparison tests (the χ2 test, Wilcoxon’s rank sum test) were performed between CD cases and UC cases. Chronological changes in PBDS+, PBDS−, and scores in identical patients were compared using the paired t-test. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used to calculate the durability of infliximab maintenance therapy. Comparison of durability rates of infliximab maintenance therapy between CD patients and UC patients was assessed using the log rank test. All directional tests were two-tailed. A P-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP 17 software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Characteriscs of the Patients

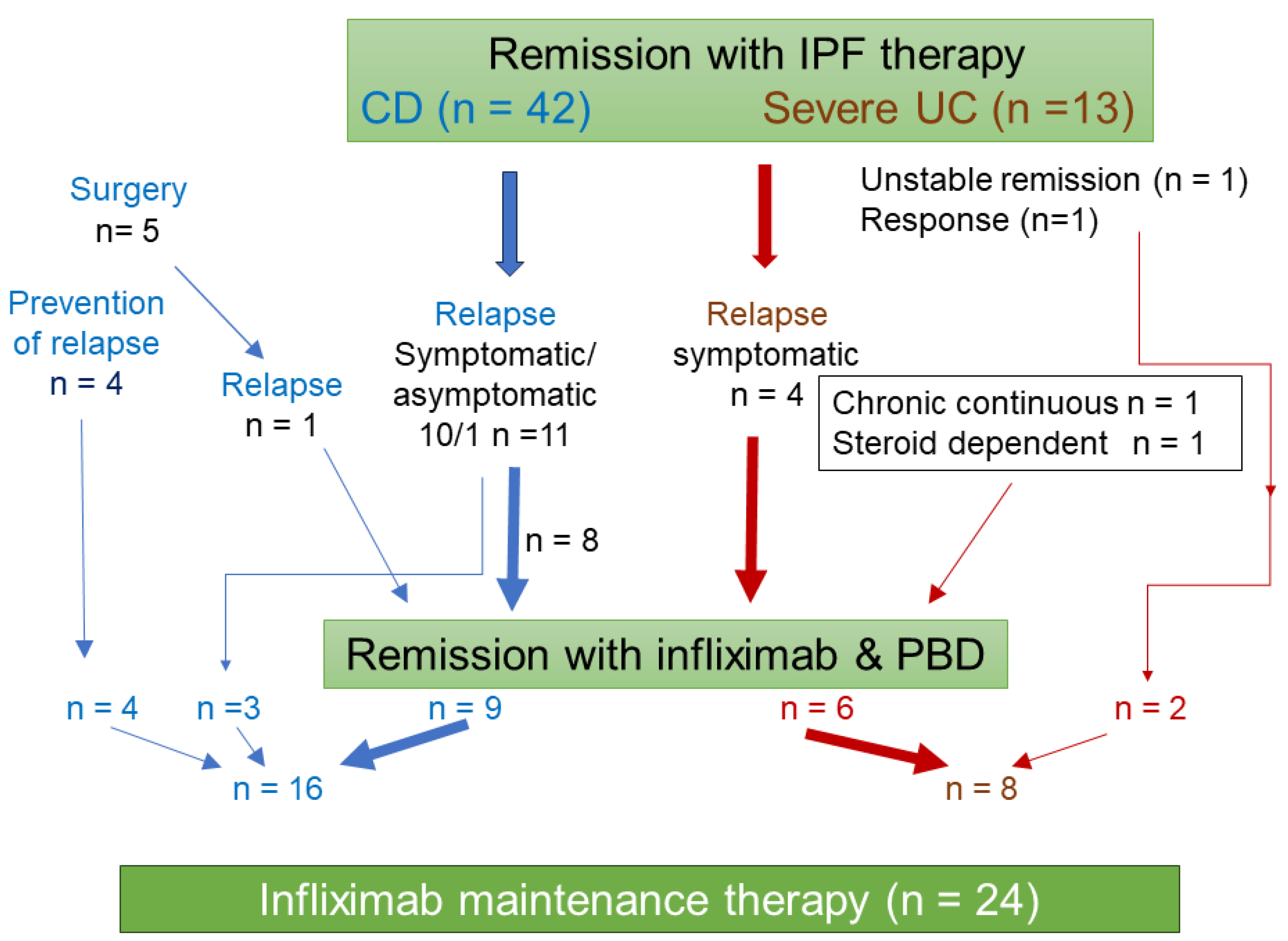

In CD, there were 11 relapsed cases after IPF therapy [

15] (10 symptomatic and one asymptomatic relapse). There were five patients who had bowel surgery. One of those patients relapsed and was eligible for maintenance therapy. Prevention of relapse after surgery was indicated in the other four patients [

24]. These 16 CD cases were eligible for scheduled maintenance therapy (

Figure 3). After IPF therapy for severe UC [

17], there were two cases with unstable remission or response. These two cases were followed with infliximab maintenance therapy. Relapse occurred in four cases after remission with IPF therapy. There was one case each with chronic continuous type or steroid dependency. In UC, these eight cases were eligible for scheduled maintenance therapy (

Figure 3). One of the eight cases was duplicated with an intermission of 20 months. The first infliximab maintenance therapy combined with azathioprine was terminated due to thrombocytopenia, as described below. Twenty months later, the second maintenance therapy with infliximab monotherapy was initiated without azathioprine. Altogether, 24 cases were included in the study (

Figure 3). Fifteen of 24 cases received standard infliximab induction therapy with PBD during hospitalization for either 6 weeks (n = 7) or 3 weeks (n = 8). The remaining nine cases received maintenance therapy without standard induction therapy (

Figure 1 and

Figure 3).

The demographics of CD patients, UC patients, and all patients including the Montreal classification of IBD [

29] are presented in

Table 1. Males were predominant in both diseases. The mean age was younger in CD (26.1 years old) than UC (44.7 years old). The median disease duration from onset of symptoms to the first infliximab infusion of maintenance therapy was 51.5 months for CD and 79.0 months for UC. CRP levels at initiation of maintenance therapy were normal in 15 patients and abnormal in nine patients. Bowel surgery was performed previously in five CD patients. All patients were non-smokers. The immunosuppressant, azathioprine, was used in five patients (

Table 1).

3.2. Efficacy

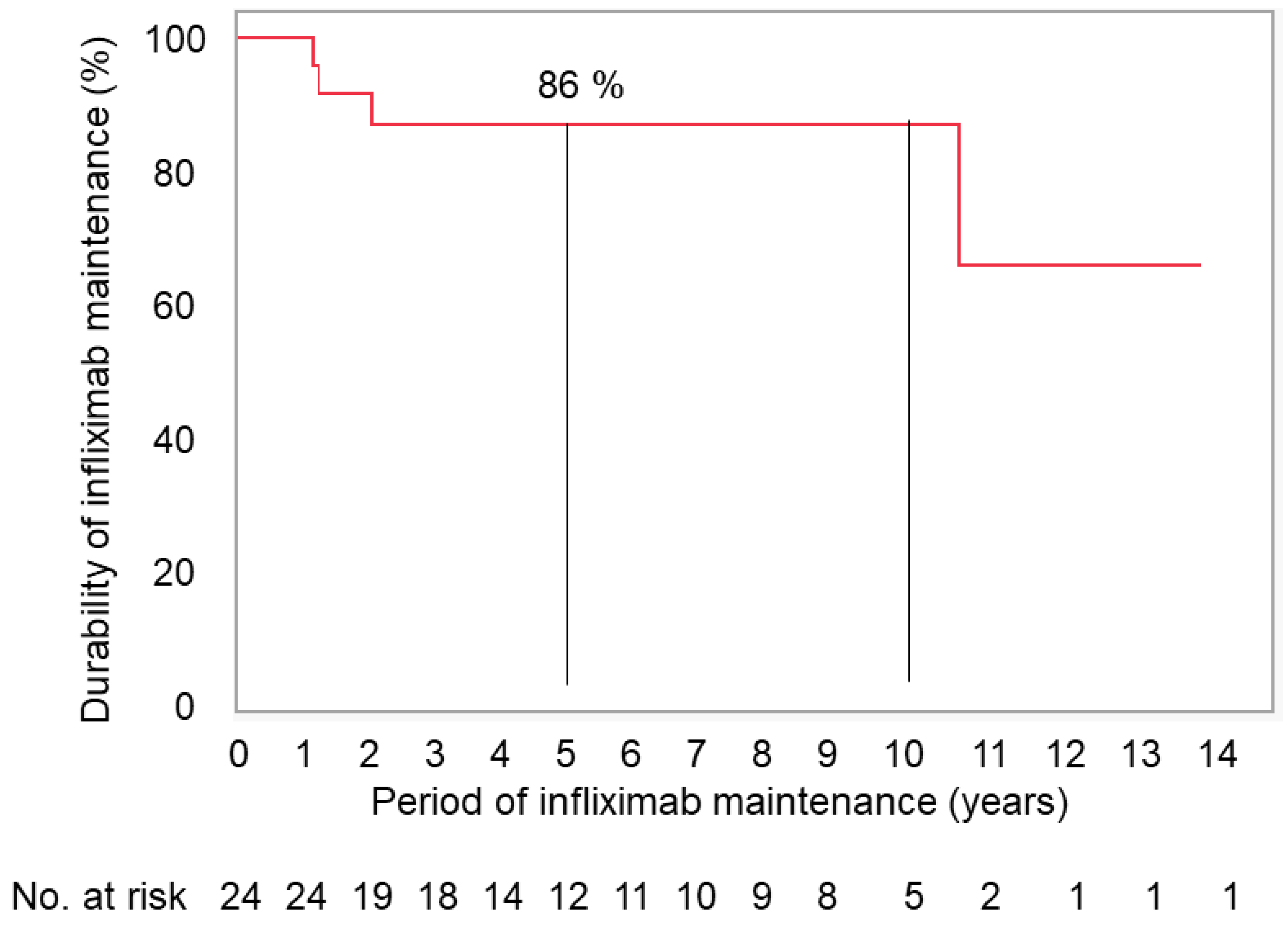

3.2.1. Durability of Scheduled Infliximab Maintenance Therapy

The median follow-up period was longer in CD (83 months) than UC (45 months) (

Table 1). There were four withdrawals from the maintenance therapy. Two patients with CD had lost response to therapy. One patient switched to adalimumab after 2 years, and the other patient underwent subtotal colectomy with ileostomy after 10 years. Two patients with UC withdrew due to side effects of medication. One patient had trouble breathing and experienced flushing during the 8th infliximab infusion (13 months after the first infusion). The other patient withdrew after the 9th infusion (14 months after the first infusion) due to progressive thrombocytopenia. This patient was able to resume and continue infliximab monotherapy without azathioprine 20 months later.

Durability rates of the therapy at 1, 3, and 5 years in CD and UC were 100%, 93%, and 93%, and 100%, 75%, and 75%, respectively. There was no difference in durability rates between CD and UC. In total, the durability rates of the therapy was 100% at 1 year and 86% at 3 years, and thereafter at 5 and 10 years (

Figure 4).

We had only one case who was symptom free with consecutive normal CRP tests and negative fecal immunochemical tests for more than 2 years. Endoscopy, however, showed small erosions in the terminal ileum. Therefore, the patient was advised to continue the therapy.

3.2.2. Change over time in PBDS

A questionnaire of dietary habits and lifestyle behaviors on the first admission was systematically obtained from all patients for the sake of dietary guidance. It was not obtained, however, in the follow up period in several patients. Mean (SD) baseline PBDS+, PBDS-, and PBDS in 23 patients were 19.9 (5.0), 11.4 (5.4), and 8.4 (7.1), respectively. Those in the short term after a median of 12 months of follow up in 11 patients were 34.5 (5.9), 1.7 (2.1), and 32.7 (6.7), respectively. Those in the long term after a median of 111 months (9 years and 3 months) of follow up in 15 patients were 27.9 (6.8), 7.0 (6.2), and 20.9 (9.2), respectively (

Table 2). From the short to long term, PBDS+ decreased, while PBDS- increased, resulting in a decrease in PBDS (

Table 2). All scores in the follow up period were significantly different compared to those at baseline according to the results of paired

t-test: higher in PBD+ and PBD, and lower in PBDS- (

Table 2,

Figure 5).

3.2.3. Safety

Side effects of medication in two patients resulted in withdrawal of maintenance therapy, as described above. Stopping the infliximab infusion was the only intervention necessary in one case. In the other case, thrombocytopenia resolved after withdrawal of infliximab and azathioprine. Thrombocytopenia did not occur after resumption of infliximab maintenance monotherapy without azathioprine. There were no serious adverse events in this study.

4. Discussion

In this study, durability rates of infliximab maintenance therapy incorporating PBD at 1 year and 3 to 10 years were 100% and 86 %, respectively. This is the highest durability rate in the literature as far as we know.

Data on maintenance therapy are primarily available for infliximab. Earlier studies on maintenance therapy with infliximab were heterogenous in their methods in induction and maintenance. Thereafter, a method was standardized: the standard induction therapy at 0, 2, and 6 weeks followed by maintenance therapy every 8 weeks [

1]. The present study followed this method. Although there is heterogeneity in indication and prior or concomitant medication, reports describing the durability of infliximab maintenance therapy in IBD at 5 years or more are presented in

Table 3 [

3,

7,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Durability rates at 5 years were 50-78% in most of the reports including reports from Japan [

32,

34], the same country as the present study. Two studies found a longer durability in CD than UC [

7,

33]. Concurrent immunomodulators were reported to increase the durability rate at 5 years compared to monotherapy: 70% verses 22% [

30] and 58% verses 37% [

35] (

Table 3). This is not consistent, however, because other studies showed considerably high durability rates, 58-74%, with a low rate of concomitant use of immunomodulation of less than 30% [

32,

36,

37]. Smoking, a well-known risk factor for CD [

11], was reported to decrease the durability of maintenance therapy [

30]. Enteral nutrition, which was very common for adult CD in Japan before the use of biologics, was shown to increase the durability of infliximab maintenance therapy [

38]. This was used in 71% of patients in a Japanese study [

34]. In our study, an immunomodulator was used in 21% of patients, which is less than in other studies (

Table 3). All smokers with either CD or UC were advised to stop smoking at the first admission to our hospital. Consequently, there were no smokers among our subjects. Enteral nutrition was used in 13% of patients with CD (2/16) in our study (

Table 1).

How can the high durability rate in this study compared to that in other reports be explained? Factors described above cannot explain this. The other difference between ours and other reports is that maintenance therapy was executed on an inpatient basis in the former and on an outpatient basis in the latter. Inpatient maintenance therapy with infliximab compelled our patients to consume the PBD. In this study, a half of patients (12/24) relapsed after IPF therapy and repeated the same induction therapy, followed by maintenance therapy. Repetition of PBD in the induction phase and periodic consumption of the PBD during maintenance therapy likely enhanced adherence to PBD. Their PBDS were significantly higher than those at base line even after a median of 9.3 years of follow up (

Table 2). It is remarkable because improved outcomes with a trial healthy diet return to baseline within 1 year of follow up in many studies [

39,

40]. Periodic meeting with nurses, nutritionists, pharmacists, and clerks during hospitalization might encourage patients to fight against the disease.

A new issue is the timing of withdrawing maintenance therapy [

41]. Discontinuation of maintenance therapy with anti-TNF therapy frees the patient from worry over possible side effects of long-term use of medication. It also decrease the patient’s and national medical cost. However, unlike UC, the relapse rate after cessation in CD is very high. About half of patients will relapse at about 5 years [

41]. Relapse even occurs in patients with complete deep remission, i.e., the concurrent remission in symptomatology, biomarkers, endoscopy, and histology [

42]. Therefore, at the moment, cessation of maintenance therapy is not recommended in CD [

41,

42]. There were no patients who satisfied four criteria for cessation of maintenance therapy in this study. Endoscopic findings of small erosions in the terminal ileum prevented cessation. Later, we learned that endoscopic remission was not necessarily required for long-term remission [

18]. Whether small lesion(s) such as aphtha and ulcers in patients with consistent normal biomarker(s) are determinant of future relapse warrants investigation.

Apparently, there are limitations with our small sample size. Assessment of the trough level of infliximab and antibody formation to infliximab are not routinely available in Japan. Nevertheless, our study showed a longer durability of infliximab maintenance therapy than others.

Our series on the outcomes with a modality incorporating PBD in IBD is going to be ended. This study was the last one. Our outcomes exceeded those of the current standard therapy in both CD and UC in both the induction and quiescent phases[

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

21,

22]. Twenty-one years ago when PBD was provided to all patients with IBD, the first author (MC) was anxious for outcomes of PBD in IBD [

14]. Later, recent basic medicine, however, revealed the interplay between diet, microbiota/its metabolites, and health/disease, and identified that a westernized diet tends to be pro-inflammatory, while a PBD tends to be anti-inflammatory [

21,

22]. Now we realize that the current modality in IBD lacks countermeasures against an environmental factor(s) despite the widely appreciated recognition that IBD is triggered by an environmental factor(s) in wealthy societies. Our excellent outcomes are thought to be a result of the new therapeutic modality incorporating countermeasure against the most plausible environmental factor in IBD, i.e., a plant-based diet. Our outcomes strengthen our assertion that the ubiquitous environmental factor in IBD is our current westernized diet [

11]. We hope our observation is more widely appreciated so that patients with IBD can lead better lives.

5. Conclusions

Infliximab maintenance therapy incorporating PBD yielded a high durability rate of 87% at 5 years in patients with IBD. This study further supports our recommendation that PBD is highly beneficial for IBD management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.; methodology, M.C.; validation, M.C.; formal analysis, M.C. and K.N.; investigation, M.C., T.T., K.N., S.T., H.M., K.S., Y.I., K.K., M.K., and H.T.; resources, M.C., T.T., K.N., S.T., H.M., K.S., Y.I., K.K., M.K., and H.T.; data curation, M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.; writing—review and editing, M.C.; visualization, M.C.; project administration, M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This protocol and the template informed consent forms were reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee of Nakadori General Hospital and by the Ethical Committee of Akita City Hospital (Protocol number: 19-2003, 12-2013, and 15-2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Miki Yamada and Kimiko Yamada, registered dietitian, and other staff of the Dietary Division of Nakadori General Hospital and Akita City Hospital for providing a lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet and dietary guidance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- D’Haens, G.R.; van Deventer, S. 25 years of anti-TNF treatment for inflammatory bowel disease: lessons from the past and a look to the future. Gut 2021, 70, 1396–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandborn, W.J.; Faubion, W.A. Biologics in inflammatory bowel disease: how much progress have we made? Gut 2004, 53, 1366–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eshuis, E.; Peters, C.P.; van Bodegraven, A.A.; Bartelsman, JF.; Bemelman, W.; Fockens, P.; D’Haens, G.R.A.M.; Stokkers, P.C.F.; Ponsioen, C.Y. Ten years of infliximab for Crohn’s disease: outcome in 469 patients from 2 tertiary referral centers. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, 1622–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, E.J.; Hazlewood, G.S.; Kaplan, G.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N. Systematic review with meta-analysis: comparative efficacy of immunosuppressants and biologics for reducing hospitalization and surgery in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 45, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoudari, G.; Mansoor, E.; Click, B.; Alkahayyat, M.; Saleh, M.A.; Sinh, P. ; Katz. J.; Cooper. G.S.; Regueiro, M. Rates of intestinal resection and colectomy in inflammatory bowel disease patients after initiation of biologics: a cohort study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, e974–e983. [Google Scholar]

- Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Rahier, J.F.; Kirchgesner, J.; Abitbol, V.; Shaji, S.; Armuzzi, A.; Karmiris, K.; Gisbert, J.P.; Bossuyt, P.; Helwig, U.; Burisch, J.; Yanai, H.; Doherty, G.A.; Magro, F.; Molnar, T.; Löwenberg, M.; Halfvarson, J.; Zagorowicz, E.; Rousseau, H.; Baumann, C.; Baert, F.; Beaugerie, L.; I-CARE Collaborator Group. I-CARE, a European prospective cohort study assessing safety and effectiveness of biologics in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 21, 771–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Hartzema, A.G.; Xiao, H. ; Wei, Y-J.; Chaudhry, N., Ewelukwa, O., Glover, S.C., Eds.; Zimmermann, E.N. Real-world pattern of biologic use in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: treatment persistence, switching, and importance of concurrent immunosuppressive therapy. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2019, 25, 1417-1427. [Google Scholar]

- Papamichael, K.; Gils, A.; Rutgeerts, P.; Levesque, B.G.; Vermeire, S.; Sandborn, W.J.; Casteele, N.V. Role for therapeutic drug monitoring during induction therapy with TNF antagonists in IBD: evolution in the definition and management of primary nonresponse. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Horin, S.; Chowers, Y. Review article: loss of response to anti-TNF treatments in Crohn’s disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 33, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayal, M.; Ungaro, R.C.; Bader, G.; Colombel, J.F.; Sandborn, W.L.; Stalgis, C. Net remission rates with biologic treatment in Crohn’s disease: a reappraisal of the clinical trial data. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 21, 1348–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, M.; Nakane, K.; Komatsu, M. Westernized diet is the most ubiquitous environmental factor in inflammatory bowel disease. Perm. J. 2019, 23, 18–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, M.; Morita, N.; Nakamura, A.; Tsuji, K.; Harashima, E. Increased incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in association with dietary transition (Westernization) in Japan. JMA J 2021, 4, 347–357. [Google Scholar]

- Fejfar, Z. Prevention against ischaemic heart disease: a critical review. In Modern Trends in Cardiology; Butterworth-Heinemann: Boston, FL, USA, 1974; pp. 465–499. [Google Scholar]

- Chiba, M.; Abe, T.; Tsuda, H.; Sugawara, T.; Tsuda, S.; Tozawa, H.; Fujiwara, K.; Imai, H. Lifestyle-related disease in Crohn’s disease: Relapse prevention by a semi-vegetarian diet. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 2484–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, M.; Tsuji, T.; Nakane, K.; Tsuda, S.; Ishii, H.; Ohno, H.; Watanabe, K.; Komatsu, M.; Sugawara, T. Induction with infliximab and plant-based diet as first-line (IPF) therapy for Crohn disease: A single-group trial. Perm. J. 2017, 21, 17–009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiba, M.; Nakane, K.; Tsuji, T.; Tsuda, S.; Ishii, H.; Ohno, H.; Watanabe, K.; Obara, Y.; Komatsu, M.; Sugawara, T. Relapse prevention by plant-based diet incorporated into induction therapy for ulcerative colitis: A single group trial. Perm. J. 2019, 23, 18–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiba, M.; Tsuji, T.; Nakane, K.; Tsuda, S.; Ishii, H.; Ohno, H.; Obara, Y.; Komatsu, M.; Sugawara, T. High remission rate with infliximab and plant-based diet as first-line (IPF) therapy for severe ulcerative colitis: Single-group trial. Perm. J. 2020, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiba, M.; Tsuji, T.; Nakane, K.; Tsuda, S.; Ohno, H.; Sugawara, K.; Komatsu, M.; Tozawa, H. Relapse-free course in nearly half of Crohn’s disease patients with infliximab and plant-based diet as first-line (IPF) therapy: Single-group trial. Perm. J. 2022, 26, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, M.; Ishii, H.; Komatsu, M. Recommendation of plant-based diet for inflammatory bowel disease. Transl. Pediatr. 2019, 8, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, M.; Hosoba, M.; Yamada, K. Plant-based diet recommended for inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2023, 29, e17–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, M.; Morita, N. Incorporation of plant-based diet surpasses current standards in therapeutic outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease. Metabolites 2023, 13, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, M.; Tsuji, T.; Komatsu, M. Therapeutic advancement in inflammatory bowel disease by incorporating plant-based diet. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroi, R.; Endo, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Naito, T.; Onodera, M.; Kuroha, M.; Kanazawa, Y.; Kimura, T.; Kakuta, Y.; Masamune, A.; Kinouchi, Y.; Shimosegawa, T. Long-term prognosis of Japanese patients with biologic-naïve Crohn’s disease treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor-α antibodies. Intest. Res. 2019, 17, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regueiro, M.; Schraut, W.; Baidoo, L.; Kip, K.E.; Sepulveda, A.R.; Pesci, M.; Harrison, J.; Plevy, S.E. Infliximab prevents Crohn’s disease recurrence after ileal resection. Gastroenterology 2009, 136, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandborn, W.J.; Hanauer, S.B. Infliximab in the treatment of Crohn’s disease: a user’s guide for clinicians. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2002, 97, 2962–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, M.; Tsuji, T.; Nakane, K.; Obara, Y.; Komatsu, M. Swift efficacy with infliximab 4 years after initial standard induction therapy followed by severe delayed infusion reaction in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2020, 26, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intractable disease measures Tokyo, Japan: Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare Web. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/kenkou/nanbyou/index.html (accessed on Accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Chiba, M.; Nakane, K.; Takayama, Y.; Sugawara, K.; Ohno, H.; Ischii, H.; Tsuda, S.; Tsuji, T.; Komatsu, M.; Sugawara, T. Development and application of a plant-based diet scoring system for Japanese patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Perm. J. 2016, 20, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satsangi, J.; Silverberg, M.S.; Vermeire, S.; Colombel, J-F. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut 2006, 55, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaparro, M.; Panes, J.; Garcia, V.; Mañosa, M.; Esteve, M.; Merino, O.; Andreu, M.; Gutierrez, A.; Gomollón, F.; Cabriada, J.L. : Montoro, M.A.; Nos, P.; Gisbert, J.P. Long-term durability of infliximab treatment in Crohn’s disease and efficacy of dose “escalation” in patients losing response. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2011, 45, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Hwang, S.W.; Kwak, M.S.; Kim, W.S.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, H.S.; Yang, D.H.; Kim, K.J.; Ye, B.D.; Byeon, J.S.; Myung, S.J.; Yoon, Y.S.; Yu, C.S.; Kim, J.H.; Yang, S.K. Long-term outcomes of infliximab treatment in 582 Korean patients with Crohn’s disease: a hospital-based cohort study. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2016, 61, 2060–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osamura, A.; Suzuki, Y. Fourteen-year anti-TNF therapy in Crohn’s disease patients: clinical characteristics and predictive factors. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2018, 63, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Y.S.; Han, M.; Park, S.; Cheon, J.H. Biologic use patterns and predictors for non-persistence and switching of biologics in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a nation-wide population-based study. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2020, 65, 1436–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otake, H.; Matsumoto, S.; Mashima, H. Long-term clinical and real-world experience with Crohn’s disease treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor-α antibodies. Intest. Res. 2022, 20, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atia, O.; Friss, C.; Focht, G.; Rimon, R.M.; Ledderman, N.; Greenfeld, S.; Ben-Tov, A.; Weisband, Y.L.; Matz, E.; Gorelik, Y.; Chowers, Y.; Dotan, I.; Turner, D. Durability of the first biologic in patients with Crohn’s disease: a nationwide study from the epi-IIRN. J. Crohns Colitis 2024, 18, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, A-L. ; Beauchesne, W.; Tessier, L.; David, C.; Berbiche, D.; Lavoie, A.; Michaud-Herbst, A.; Tremblay, K. Adalimumab, infliximab, and vedolizumab in treatment of ulcerative colitis: a long-term retrospective study in a tertiary referral center. Crohn’s & Colitis 360 2021, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, M.A.; Viola, A.; Cicala, G.; Spina, E.; Fries, W. Effectiveness and safety profiles of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: real life data from an active pharmacovigilance project. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirai, F.; Takeda, T.; Takada, Y.; Kishi, M.; Beppu, T.; Takatsu, N.; Miyaoka, M.; Hisabe, T.; Yao, K.; Ueki, T. Efficacy of enteral nutrition in patients with Crohn’s disease on maintenance anti-TNF-alpha antibody therapy: a meta-analysis. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 55, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atallah, R.; Filion, K.B.; Wakil, S.M.; Genest, J.; Joseph, L.; Poirier, P.; Rinfret, S.; Schiffrin, E.L.; Eisenberg, M.J. Long-term effects of 4 popular diets on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2014, 7, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, N.D.; Cohen, J.; Jenkins, D.J.; Turner-McGrievy, G.; Gloede, L.; Green, A.; Ferdowsian, H. A low-fat vegan and a conventional diabetes diet in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: A randomized, controlled, 74-wk clinical trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 1588S–1596S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C. To stop or not to stop? Predicting relapse after anti-TNF cessation in patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 1668–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarallo, L.; Bolasco, G.; Barp, J.; Bianconi, M.; di Paola, M.; Di Toma, M.; Naldini, S.; Paci, M.; Renzo, S.; Labriola, F.; De Masi, S.; Alvisi, P.; Lionetti, P. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha withdrawal in children with inflammatory bowel disease in endoscopic and histologic remission. Inflamm. Bowel. Dis. 2022, 28, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).