1. Introduction

Finding solutions within the green entrepreneurship model is a challenge to consider. Its nature is a multifocal and complex field. The system dynamics is premised on systems thinking. A systems thinking concept is studied in industrial psychology. Systems thinking considers an individua

l’s interaction with the system underpinned by the input from the environments, the action taken, and the output [

1,

2]. The system dynamics approach takes the process further by using software and technology to add meaning to the systems thinking principle. The system dynamics approach further allows proposing a solution to complex challenges by simultaneously looking at the different avenues [

3,

4]. The idea is to integrate the system dynamics approach into the industrial psychology field. There is a need to adopt and practise sustainable behaviour to preserve resources for the current and future generations to combat environmental challenges in the global sphere. Sustainable behaviour can be seen as incorporating green practices in business strategies, organisational functioning, and ecological footprint to complement the industrial psychologist’s identity and the role in assisting organisations to transition into a green economy effectively. In the global sphere, there is a need to live by the motto of incorporating innovation through the lens of an industrial psychologist in a green space. On the other hand, the study took an interdisciplinary role by extending to engineering, mathematics, computer science and economics, as defined by [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Thus, the ultimate motivation and rationale for the study were to contribute through the entrepreneurial mindset, the green economy, and pro-environmental behaviour within the lenses of system dynamics, to add onto the theoretical framework and expanding the scope of practice for industrial psychologists.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Psychology of Entrepreneurship Framework

Upon reviewing the literature on the psychological principles that apply to the study, the sub-field of the psychology of entrepreneurship framework emerges to strengthen the individual human attributes framework and the interventions from the human side. According to previous research, the psychology of entrepreneurship framework consists of cognition and alertness [

8]. Furthermore, the authors add additional factors, such as environmental psychology, to the framework which is explained in subsequent section.

2.1.1. Cognition and Alertness

The level of cognition, the ability to pursue markets, and the ability to adapt to the market form part of alertness or brain functioning [

8,

9,

10]. Brain functioning gives rise to neuro-entrepreneurship, often strengthened by exposure and gained through education. The brain is like plastic. It absorbs everything around it [

11,

12,

13], and then the crystallisation, sense-making, application, and level of education further trim down how one uses the absorbed information. When translating the latter argument in the current study, it gives emergence to neuro-green entrepreneurship, where an individual with specific cognition, values, or push and pull factors regarding green entrepreneurship is materialised. The individual assimilated onto the environment develops some alertness, ability, resilience, and taxonomy, to exploit the market and pursue entrepreneurship. The following characteristics support the entrepreneurial alertness as advocated by [

10] which consists of the following elements: knowing how to draft a business profile, planning, creating a website, conducting a market analysis, as well as gaining financial aid, which is basically balancing both the financial and the non-financial support.

The current study simulates cognitive theory through education, skills programmes, and total entrepreneurial activity, as shown in the results section below.

2.1.2. Environmental Psychology

As part of social psychology, environmental psychology focuses on the behaviour, motivation, and attitudes domain concerning sustainability and ecological awareness perspectives. Furthermore, the sub-field of environmental psychology offers a framework that includes appraisal, cognition, personality traits, the value system, reinforcement, and pro-environmental behaviour [

14]. The green economy and minimising environmental challenges and climate change must be designed and simplified so everyone will understand the phenomena [

15]. Some appraisal tactics need to be highlighted in this process. For instance, informing society about the benefits of complying with policies, the implications of climate change for current and future generations, and the benefits of gaining knowledge about climate change to capitalise on pro-environmental behaviour [sustainable behaviour]. The impact of the green economy mechanism needs to be carefully designed and mapped for current and future generations. The mapping may include the benefits of learning more about climate change and how to capitalise on pro-environmental action or behaviour and adopting green entrepreneurial mindset within the South African context. The rationale for incorporating psychology into environmental phenomenon is that systems, ecosystems, and processes fail because people and behaviour are overlooked in the green economy and engineering spaces [

16]. Inappropriate behaviour, the lack of motivation and negative attitudes towards a green economy still threaten societies, calling for actions to save the environment and preserve natural resources. One way to remedy the challenges is the adoption of entrepreneurial mindset as explained in the subsequent section.

2.1.3. Entrepreneurial Mindset

Entrepreneurial mindset can be measured through education, motivation and intentions, social factors and values, and gender equality through gender representation. The level of education and skills individuals acquire can determine the success or failure of any enterprise, including a green enterprise.

Social factors and values are seen through whether a specific society will support the business and if they put all efficacy on the set entrepreneurial venture. Previous research suggests that inequalities within the green economy influence its capabilities and social norms [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. The legal framework may facilitate distributive justice and equal access to resources, even for societies that cannot afford the services. It also promotes the adoption of an entrepreneurial mindset while protecting the environment [

18,

23].

Motivation and intent often tell a different story; for instance, an individual may have the intention to start a business, but the activity and motivation may be lower. Some push and pull factors need to be considered in any entrepreneurial venture. Individuals are pushed into entrepreneurship because they are dissatisfied with their current jobs and drawn into entrepreneurship because of the market opportunities [

24]. Furthermore, the start-up triggers are often pushed by factors such as the need for survival, retrenchments, divorce, death in the family, the desire to build an empire and generational wealth. The factors that make it possible or encourage an individual to venture into business are family members, mentors, customers, and potential business partners [

24,

25,

26].

[

27] identified the potential pull in the market. The pull factors are observed by an individual seeking a job that exposes one to entrepreneurial opportunities, education or capacity building [

28]. Furthermore, aspiring entrepreneurs are drawn into the market due to being power-hungry. They prefer independence, have a high need for achievement, are innovative, and have the ambition to embark on new challenges and gain social standing and recognition [

24,

25,

26]. A person may venture into business due to a job misfit, personality, management disagreements, retrenchments, and a lack of autonomy [

27].

While the motives and push and pull factors are generic to any enterprise, the entrepreneurial mindset in green space differs slightly. Previous research found that the motivation to embark on ecological entrepreneurship should be considered at the macro, micro and meso levels [

29,

30]. The macro-level focuses on green entrepreneurship, serving societal needs, generating wealth, and solving economic and environmental challenges at a larger scale. The micro-level involves earning a living to provide for one and their family. The meso-level includes green entrepreneurs developing markets for green products and offering services to small markets or firms [

29,

30,

31,

32]

Another green entrepreneurship motive identified from previous studies is that individuals pursue green entrepreneurship because they are committed to sustainable living and have a strong desire and passion for nature because they need to maintain healthy living [

25]. Other investigations found that entrepreneurs valued the green value system and seized available opportunities [

25,

30]. The factors influencing the motives to engage in green entrepreneurship included education, the availability of a green market, best practices learned from different countries, motivation to benefit the economy and environment, and profit generation [

17]. Moreover, motives from international markets indicated encouragement and influence from family commitments and support, desire for control and independence, profit from cattle or livestock, lifestyle, own research within the green economy thematic areas, and the exposure gained from international travel [

33]. In addition, motives discovered in the global market were to reduce the environmental impact, materials and energy costs, earn a living, and educate society[

30,

34].

[

35] explored green entrepreneurship and found that some individuals pursued ecopreneurship to change their attitude toward the environment, especially in the light of climate change, while at the same time leaving a legacy and raising awareness of the green market. These motives are the pull-and-push factors for a venture into green entrepreneurship and are influenced by failed markets and changes in the natural environment [

36].

When looking at the entrepreneurial mindset, gender discourse comes into play. There is a parity in terms of gender representation when it comes to business ventures as well as environmental factors. The female and male opportunity ratio shows the gender differences and whether individuals can identify opportunities in the entrepreneurial market. More men can seize entrepreneurial markets than women, and men are the ones who act when it comes to generating profits [

37].

[

38] found that women did not necessarily receive enough social support due to patriarchy and their questioned abilities within entrepreneurial markets. The representation of women in the pursuit of entrepreneurship still needs to improve. However, more women than men have a strong need to protect the environment.

2.2. System Dynamics and Entrepreneurial Mindset

An investigation into the entrepreneurial mindset needs to be conducted through green entrepreneurship and system dynamics lenses. The previous efforts looked at generic entrepreneurship and system dynamics. Generic entrepreneurship is within academic institutions, municipalities and communities, as well as corporate entrepreneurship [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43], With one study on green entrepreneurship and system dynamics [

16] with less attention on the entrepreneurial mindset. Other studies focused on modelling causal loop and stocks and flows on the entrepreneurial innovation with integration of agent-based [

44]. The modelling of the latter study is based on R and D interventions, risk metrics, preferences, research funds, enterprise innovation capability, market information, and government support.

Meanwhile, [

45] looked at the system dynamics modelling of the causal loop on household consumption and saving, innovation, and customers as part of the business cycle. The entrepreneurial mindset investigated in the literature is based on cognitive abilities, attributes, decision-making processes, capabilities, and entrepreneurial traits [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. The current study adds to the framework by suggesting that an entrepreneurial mindset can also focus on education, social norms and values, gender representation, intentions, and total early entrepreneurial activity by modelling these variables using a system dynamics model through the lenses of green entrepreneurship.

3. Primary Objective

To conceptualise and simulate the sub field of entrepreneurial mindset, through the lenses of industrial psychology, onto green entrepreneurship.

The system dynamics approach utilises dynamic hypotheses in the position of aims regarding the empirical study of the research. [

3,

52] asserts that the possible solutions must form part of the dynamic hypothesis when formulating a hypothesis or aim. The dynamic hypothesis of the study is as follows:

The entrepreneurial mindset which is a sub-variable of industrial psychology can be simulated with the lenses of green entrepreneurship through education, gender representation, total entrepreneurial activity, values and norms.

4. Method

The current study utilised the system dynamics approach and simulated the industrial psychology sub-variable, namely the entrepreneurial mindset. The data fed onto the model is readily available from the public domain. The steps in the system dynamics adapted from [

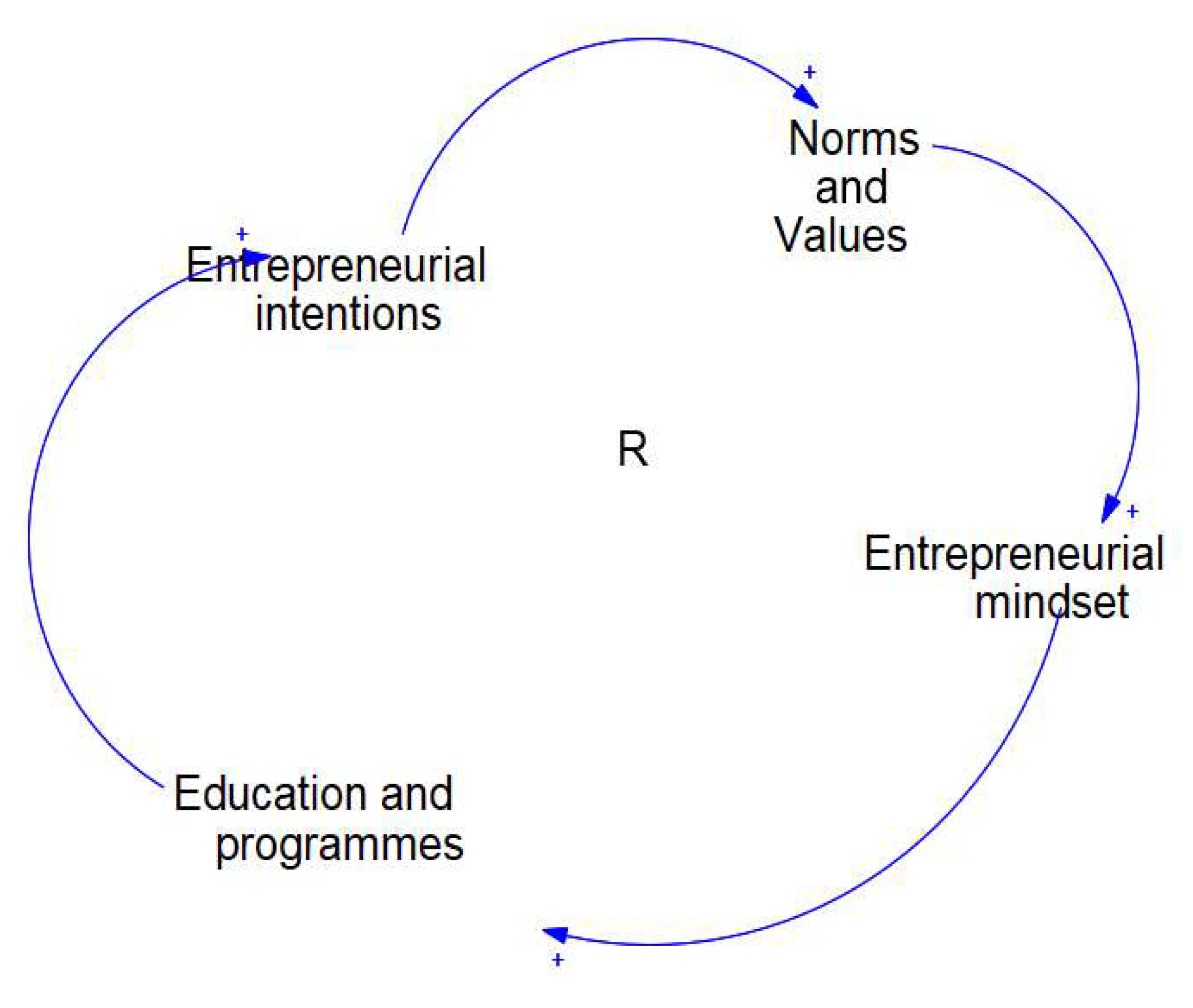

53] state that the dynamic hypothesis and mental scenarios need to be formulated before simulating and validating the model. Therefore, the mental hypothesis and scenario for the study are as follows: Firstly, an individual need to ascertain that there is a need to adopt an entrepreneurial mindset by looking at the entrepreneurial activity, success factors, intentions and whether opportunities exist to seize the market. The norms, motivation and the level of education may influence this analysis. Secondly, once the mental modelling and scenario are created, the causal loop needs to be formulated. The system dynamics modelling in the current study used dynamic variables, causal loop, and parameters See

Figure 1. Once the causal loop has been formulated, the equations, behavioural graphs, and the validation process follow. The equation of the study is on equation 1, and the behavioural graph is on

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. The current researchers decided to define these variables and sub-variables of the entrepreneurial mindset as further contributions to literature and framework, as discussed in section 2. System dynamics modelling may include parameters, spikes, and chaotic and random behavioural graphs. The randomness and chaotic graphs demonstrate the spikes and overshooting, as termed by [

3,

52,

54,

55]. Usually, one perceives the graph going up and down with no clear pattern, often described as a chaotic graph with spikes. When entering data using system dynamics, you first have to define parameters that delineate how far a graph can go. Once mental modelling and scenario formulation are done, the data is fed onto the model using industry reports, empirical data, or behaviour observation of a set scenario or environment. System dynamics modelling suggests defining the variable and strategically assessing the feasibility of the model through projections and forecasting.

5. Results and Sources of Data

The current study treated the entrepreneurial mindset as a dynamic variable and the critical green entrepreneurship driver. The causal loop during the scenario formulation is as follows: If education and programmes regarding entrepreneurship increases, the intentions influenced by motivation increases, whereby the society becomes receptive to the idea through the increased norms and values, which in turn increases the entrepreneurial mindset see

Figure 1.

The dynamic variable equation for the SA entrepreneurial mindset and supporting the research aim is as follows:

The data was retrieved from the Gem consortium and is available online. The following link was used to obtain the data on gender representation, the total early-stage entrepreneurial activity, and the entrepreneurial intentions

https://www.gemconsortium.org/file/open?file Id=50411. The variables mentioned in the report above are separate from the entrepreneurial mindset category. However, the authors defined the dynamic variable of the entrepreneurial mindset by looking at the following sub-variables using the report’s data and assessing which data can be used to include in the current sub-variable. As mentioned earlier, the following variables and their data were retrieved:

Gender representation,

Total early-stage entrepreneurial activity,

Entrepreneurial intentions

Green entrepreneurship education,

Values and norms.

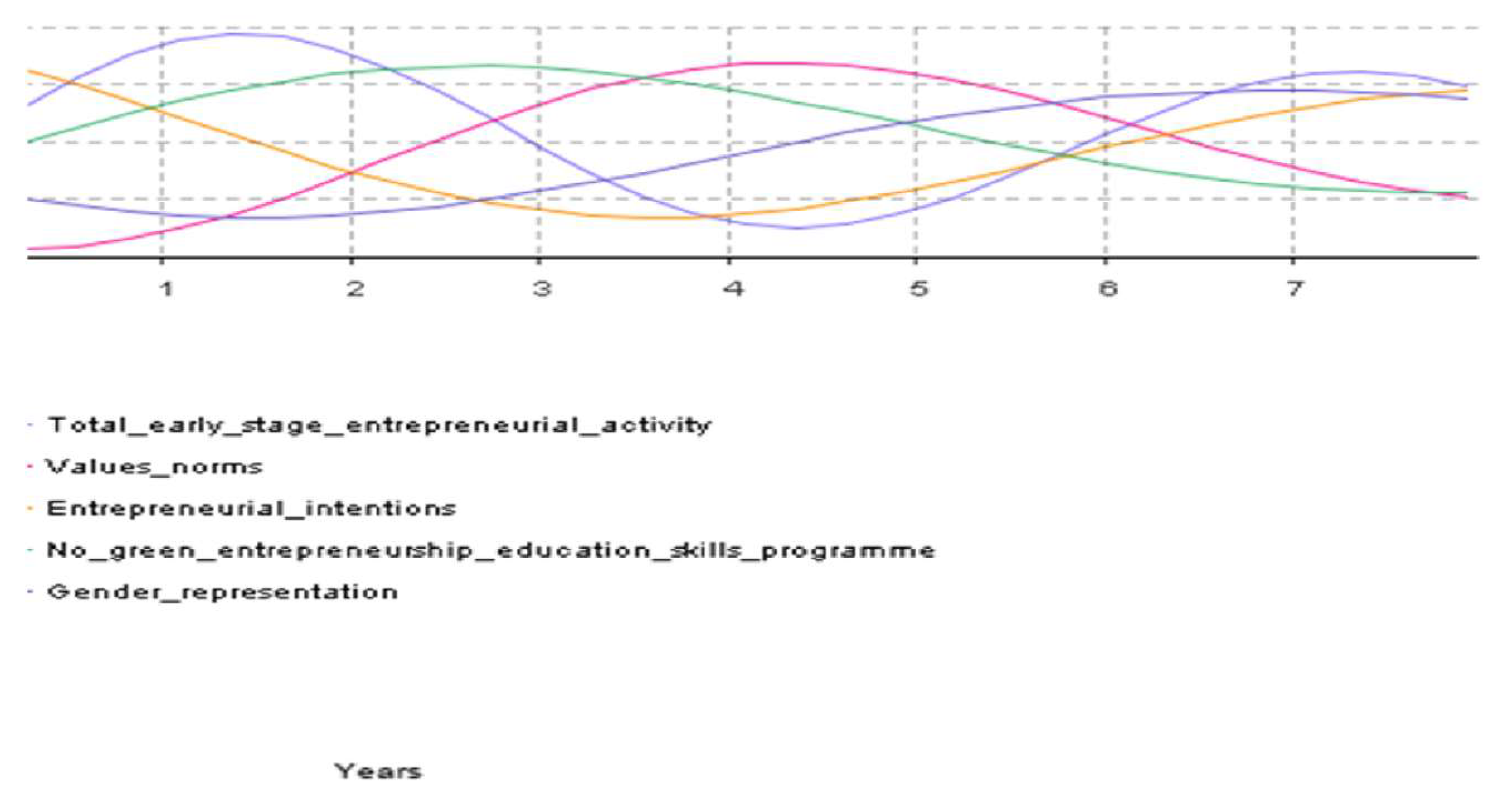

The entrepreneurial mindset behaviour graph is illustrated in

Figure 2. The graph is chaotic, with spikes going up and down before reaching a goal.

Figure 2 shows the randomness or chaos of the entrepreneurial mindset in the behavioural graph. The randomness and chaotic graphs demonstrate the spikes and overshooting, as termed by [

3,

52,

54,

55]. The spikes and overshooting are presented in

Figure 2, thereby showing the behaviour of the entrepreneurial mindset with no apparent pattern, causing some delays before reaching a goal.

Figure 2 shows total early-stage entrepreneurial activity, female and male opportunities through representations, entrepreneurial intentions, green entrepreneurship education and skills programme, and values and norms.

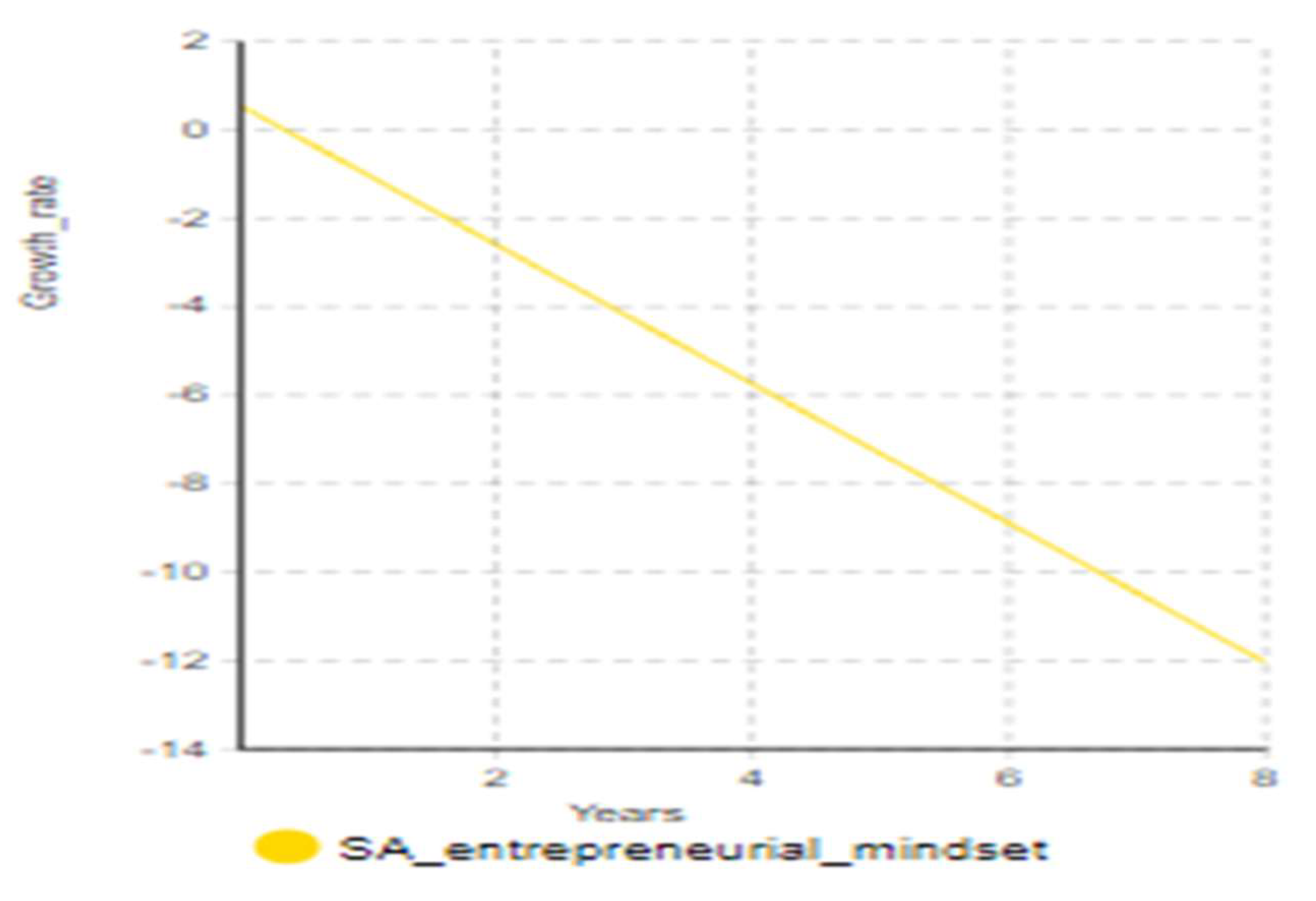

The behavioural graph of the entrepreneurial mindset shows a decline when grouped, as depicted in

Figure 3. The decline rate is -12. by year eight from year 1.

6. Discussions and Contributions

The perceived opportunities include the individual

s’ perceptions about the opportunities and whether they can identify entrepreneurial opportunities. Necessity or motive, derived from the principle of motivation, is part of the entrepreneurial mindset psychology of entrepreneurship framework, which consists of the female-male representation, green education and the skills programme, the values and norms, and capabilities in the current study. Although the variable within the entrepreneurial mindset is not clustered under the mindset category anywhere else, the current researchers simulated the dynamic variable of the entrepreneurial mindset by looking at the sub-variables as per

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. The simulation and clustering differ from previous research [

39,

40,

41,

42]. The policies, frameworks, political will, and the stakeholders from the community need to form a collective agenda in the formulation and the implementation of the entrepreneurial mindset framework from the current study. The focus should be on the entrepreneurial mindset by paying particular attention to the intentions and the activity as well as through diversified support to ensure gender representations in the entrepreneurial era.

The gender representations ratio as per

Table 1 show whether individuals can identify opportunities in the entrepreneurial market. As per the Gem consortium report more men can seize the entrepreneurial markets than females, and they are the ones who can act when it comes to generating profits [

37]. However, more women than men have a strong need to protect and save the environment. The total early-stage entrepreneurial activity line denotes the actual action as per

Figure 2. The intention is lower than the motivation, meaning people may have intentions or thoughts about starting a business, but the actual action or motivation is low (see

Figure 2). The discovery of low motivation or inaction is similar to the motivation literature by [

25,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51].

Figure 2 shows the entrepreneurial mindse

t’s randomness or chaos in the behavioural graph. The randomness and chaotic graphs demonstrate the spikes and overshooting. The first researchers who had investigated the overshooting and spikes looking at a different sub variable was conducted by [

54,

56,

57]. The spikes and overshooting are demonstrated in the graph in

Figure 2, thereby showing the behaviour of the entrepreneurial mindset with no apparent pattern, causing some delays before reaching a goal. The current researchers deduce that the level of skills drainage may contribute to the delay and the unsmooth journey as defined by the spikes before reaching a goal, as per

Figure 2. The system dynamics methodology contributes to industrial psychology by opening avenues for consulting. Industrial psychologists can suggest interventions and assessments pertaining to green entrepreneurial mindset and assist with policy formulation and implementation through psychology of green entrepreneurship. The multi-discipline of integrating the psychology of entrepreneurship is guided by [

8,

10].

Society can play a role in supporting environmental innovation. In contrast, entrepreneurs could ensure that they exploit the markets and offer affordable products and services to the communities at large. The total early-stage entrepreneurial activity line denotes the actual action, according to

Figure 2.

Support from government and private entities will be needed for subsidies to waive some costs associated with green entrepreneurship. The authors believe that for environmental challenges to be minimised and green entrepreneurship to flourish, human behaviour and motivation can be modelled using environmental and psychological concepts as a point of departure.

Disrupting known norms and cultures within green spaces and tapping into transformational and laissez-faire types of leadership can further be incorporated within the green economy and green entrepreneurship and further adds onto the scope of industrial psychologists. In this context, work or industrial psychologists can play a crucial role.

System dynamics is a valuable tool that can reduce the slow implementation of green entrepreneurship by using software and simulations to make projections. Based on the predictions, system dynamics modelling can formulate multiple environmental, social, and economic solutions at the same time. There is pressure to perform and offer solutions from the multidisciplinary approach of industrial psychology and from the engineering perspectives to thrive and cope in the unpreceded times.

7. Conclusion

The sub-variable entrepreneurial mindset within the industrial psychology field can be used as a yardstick to support green entrepreneurs thriving as part of a coaching and mentoring toolkit. The simulated variable in the current study is the entrepreneurial mindset simulated through education, skills and programmes, values, norms, or necessity, entrepreneurial intentions and gender representation. The model should equip enterprises and societies to adopt prosocial behaviour within sustainability through a green entrepreneurial mindset. The current study adds to the psychology of entrepreneurship framework with the contribution of green psychology of entrepreneurship through social factors, such as gender representation and environmental psychology.

Furthermore, adopting an entrepreneurial mindset within the lenses of a green economy contributes to negotiating a transdisciplinary and multidisciplinary approach by intertwining green entrepreneurship, industrial psychology, and industrial engineering through system dynamics.

Author Contributions

The first author C. D. Diale-Makgetla was responsible for the conceptualisation, the literature review, the results analysis, the discussion as well as the model formulation, coding and simulation. The second author H. Von der Ohe provided an instrumental role in guiding the literature and assisted in model conceptualisation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The current study is part of the project that the first author conceptualised, and it gained ethical clearance from the University of South Africa.

Informed Consent Statement

The study did not involve humans; therefore, informed consent is not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available, and it is provided in

Table 1.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflict of interests to disclose.

References

- Cummings, T. G. & Worley, G. (2015). Organisation development and change. 10th ed. Cengage Learning. [CrossRef]

- Cummings, T.G.; Cummings, C. The Relevance Challenge in Management and Organization Studies: Bringing Organization Development Back In. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2020, 56, 521–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, J. W. From the ranch to system dynamics. In Management Laureates; 2018; pp. 335–370. [Google Scholar]

- Sterman, J. System dynamics at sixty: the path forward. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2018, 34, 5–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D.; Billingham, J.; Wilby, J.; Blachfellner, S. The synergy between general systems theory and the available systems worldview. System: Connecting matter, life, culture, and technology 2016, 4, 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, S. The open theory and its enemy: Implicit moralisation as epistemological obstacle for general systems theory. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2019, 36, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Dynamic capabilities as (workable) management systems theory. J. Manag. Organ. 2018, 24, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frese, M.; Gielnik, M.M. The psychology of entrepreneurship. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 2014, 1(1), 413–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisrich, R.; Langan-Fox, J.; Grant, S. Entrepreneurship research and practice: A call to action for psychology. Am. Psychol. 2007, 62, 575–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, B. Entrepreneurial alertness, self-efficacy and social entrepreneurship intentions. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2020, 27, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaf, C. (2013). Switch on your brain: The key to peak happiness, thinking, and health. Baker books.

- Leaf, C. (2018). Think, learn, succeed: Understanding and using your mind to thrive at school, the workplace, and in life. Baker books.

- Sharma, G.D.; Paul, J.; Srivastava, M.; Yadav, A.; Mendy, J.; Sarker, T.; Bansal, S. Neuroentrepreneurship: an integrative review and research agenda. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2021, 33, 863–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busic-Sontic, A.; Czap, N.V.; Fuerst, F. The role of personality traits in green decision-making. J. Econ. Psychol. 2017, 62, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diale, C.D.; Kanakana-Katumba, M.G.; Maladzhi, R.W. Ecosystem of Renewable Energy Enterprises for Sustainable Development: A Systematic Review. Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. J. 2021, 6, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diale, C.D.; Kanakana-Katumba, G.; Maladzhi, R.W. Green Entrepreneurship Model Utilising the System Dynamics Approach: A Review. 2019 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 384–389.

- Diale, C.D. A South African green entrepreneurship model utilising the system dynamics approach. Doctoral dissertation, University of South Africa, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Guruswamy, L. Energy justice and sustainable development. Colo. J. Int’l Envtl. L. & Pol’y 2010, 21, 231. [Google Scholar]

- Nhamo, G. Green economy readiness in South Africa: A focus on the national sphere of government. Int. J. Afr. Renaiss. Stud. - Multi-, Inter- Transdiscipl. 2013, 8, 115–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.R.; Lee, K.; O'Riordan, T. The importance of an integrating framework for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: The example of health and well-being. BMJ Glob. Health 2016, 1, e000068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. The inequalities-environment nexus: towards a people-centred green transition. OECD Green Growth Papers, No. 2021/01. OECD Publishing: Paris, Frence, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Venter, C.; Jennings, G.; Hidalgo, D.; Pineda, A.F.V. The equity impacts of bus rapid transit: A review of the evidence and implications for sustainable transport. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2017, 12, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diale, C.D.; Kanakana-Katumba, M.G.; Maladzhi, R.W. Environmental Entrepreneurship as an Innovation Catalyst for Social Change: A Systematic Review as a Basis for Future Research. Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. J. 2021, 6, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monitor, G. E. (2015). Global entrepreneurship monitor. Entrepreneurship in Brazil (National Report). Curitiba: Brazilian Institute of Quality and Productivity, Paraná. https://www.gemconsortium. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bosma, N. , Schøtt, T., Terjesen, S. A., & Kew, P. (2016). Global entrepreneurship monitor 2015 to 2016: Special topic report on social entrepreneurship. Available at SSRN 2786949. [CrossRef]

- Karabulut, A.T. Personality Traits on Entrepreneurial Intention. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 229, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, E.; Swail, J.; Bell, J.; Ibbotson, P. Following the pathway of female entrepreneurs. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2005, 11, 84–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diale, C. D. (2016). Black African women in South African male-dominated entrepreneurial environments. University of Pretoria (South Africa).

- Bergset, L. The Rationality and Irrationality of Financing Green Start-Ups. Adm. Sci. 2015, 5, 260–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gast, J.; Gundolf, K.; Cesinger, B. Doing business in a green way: A systematic review of the ecological sustainability entrepreneurship literature and future research directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskwa, E.; Higgins-Desbiolles, F.; Gifford, S. Sustainability through food and conversation: the role of an entrepreneurial restaurateur in fostering engagement with sustainable development issues. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 23, 126–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguonu, C. Business Strategies for Effective Entrepreneurship: A Panacea for Sustainable Development and Livelihood in the Family. Int. J. Manag. Sustain. 2015, 4, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walley, L. , Taylor, D., & Greig, K. (2010). Beyond the visionary champion: Testing a typology of green entrepreneurs. In M, Schaper (Ed.) Making Ecopreneurs: Developing Sustainable Entrepreneurship, pp 59-74.

- Robinson, S.; Stubberud, H.A. Green innovation and environmental impact in Europe. Journal of International Business Research 2015, 14(1), 127. [Google Scholar]

- Silajdžić, I.; Kurtagić, S.M.; Vučijak, B. Green entrepreneurship in transition economies: a case study of Bosnia and Herzegovina. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 88, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, I.E.; Tasopoulou, K.; Tsagarakis, K. A Typology of Green Entrepreneurs Based on Institutional and Resource-based Views. J. Entrep. 2018, 27, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. 2017. Available online: https://www.gemconsortium.org/file/open?fileId=50411 (accessed on 3 April 2021).

- Diale, D.; Carrim, N.M. Experiences of black African women entrepreneurs in the South African male-dominated entrepreneurial environments. J. Psychol. Afr. 2022, 32, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloodgood, J.M.; Hornsby, J.S.; Burkemper, A.C.; Sarooghi, H. A system dynamics perspective of corporate entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2015, 45, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, L.; Chen, J.; Xie, K. Mechanism and policy combination of technical sustainable entrepreneurship crowdfunding in China: A system dynamics analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 177, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, D.; Kolomytseva, A.; Apanasenko, A.; Isaichik, K. Modelling of the Municipality Entrepreneurial Community Functioning Using the Methods of System Dynamics. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, C. Entrepreneurial Mindset: A Synthetic Literature Review. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2017, 5, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zali, M.; Najafian, M.; Colabi, A. M. System dynamics modeling in entrepreneurship research: A review of the literature. International Journal of Supply and Operations Management 2014, 1, 347–370. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.D.; Kefan, X.; Hua, L.; Shi, Z.; Olson, D.L. Modeling technological innovation risks of an entrepreneurial team using system dynamics: An agent-based perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2010, 77, 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, S.; Urbano, D.; Gómez, D. The role of innovative entrepreneurship within Colombian business cycle scenarios: A system dynamics approach. Futures 2016, 81, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busenitz, L.W.; Barney, J.B. Differences between entrepreneurs and managers in large organizations: Biases and heuristics in strategic decision-making. J. Bus. Ventur. 1997, 12, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, G.; Zakar, T.; Ku, C.Y.; Sanborn, B.M.; Smith, R.; Mesiano, S. Prostaglandins Differentially Modulate Progesterone Receptor-A and -B Expression in Human Myometrial Cells: Evidence for Prostaglandin-Induced Functional Progesterone Withdrawal. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 1010–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynie, J.M.; Shepherd, D.; Mosakowski, E.; Earley, P.C. A situated metacognitive model of the entrepreneurial mindset. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathisen, J.E.; Arnulf, J.K. Entrepreneurial Mindsets: Theoretical Foundations and Empirical Properties of a Mindset Scale. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Busenitz, L.; Lant, T.; McDougall, P.P.; Morse, E.A.; Smith, J.B. Toward a Theory of Entrepreneurial Cognition: Rethinking the People Side of Entrepreneurship Research. Entrep. Theory Pr. 2002, 27, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCLELLAND, D.C. Characteristics of Successful Entrepreneurs*. J. Creative Behav. 1987, 21, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, J. W. (2009). Some basic concepts in system dynamics. Sloan School of Management, 1-17.

- Gokhan, M.; Yücel, M.; Ayvaz, B. Causal Loop Analysis and improvement areas of AS 9100 aerospace quality management system implementation in Turkish aerospace and defence industry supply chain. International Journal of supply chain management 2019, 8(3), 685. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D. The unavoidable apriori: A discussion of significant modelling paradigms. The System Dynamics Method, Oslo, 161240. 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Boeing, G. Visual Analysis of Nonlinear Dynamical Systems: Chaos, Fractals, Self-Similarity and the Limits of Prediction. Systems 2016, 4, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roubík, H.; Mazancová, J.; Rydval, J.; Kvasnička, R. Uncovering the dynamic complexity of the development of small–scale biogas technology through causal loops. Renew. Energy 2019, 149, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, E.; Kramer, B.; Peherstorfer, B.; Willcox, K. Lift & Learn: Physics-informed machine learning for large-scale nonlinear dynamical systems. Phys. D: Nonlinear Phenom. 2020, 406, 132401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).