Submitted:

20 August 2024

Posted:

22 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1.0. Introduction

- Examine the physical characteristics of the evaluated health resorts;

- Investigate the material usage utilised in the interior of three primary functional spaces and exterior works.

- Assess the use of innovative solutions.

2.0. Methodology

3.0. Literature Review

4.0. Results

4.1. Case Study 1: Seaweed Bay Health Resort

- Name of Building: Seaweed Bay Health Resort.

- Location: Weihai, China.

- Year of Construction: 2019.

- Facility Category: Health Resort.

-

Other Data:

- Architect(s)/Design Firm – Greyspace Architecture Design Studio.

- Area – 1,787 Square Meters.

- Client – Rongcheng Jingda Health and Wellness Co., Ltd.

- Project Background/ Brief –

Located in Weihai City, Shandong Province’s Shidao Management Area. Fanjia Village faces the stunning Shidao Bay Inner Lake to the east. It is a traditional village in the courtyard style of the north. In recent years, Shidao has implemented the “one hundred miles of coastline, one scenic chain” policy.Creating four sections could open up an entire area dedicated to beautiful countryside tourism demonstration belts, including the “most beautiful fishing village” folklore display area, the “ten miles of the ancient township” cultural tourism combination area, the “mountain residence sea rhyme” style experience area, and the “quality agriculture” leisure and sightseeing area. The demonstration segment’s centre section is where Fanjia Village is situated. The construction of the overall scenic area and infrastructure along the coastline has gradually destroyed the traditional village and the area surrounding Fanjia Village. As of May 2020, the village has largely vanished and in its place were ranks and columns of boarded-up residential buildings and villa areas. The houses in Fanjia Village also stand deserted, with some in a run-down state and requiring renovation (ArchDaily, 2021; Svensson, 2021).Retaining nostalgia and allowing historical memories to coexist with modern life is the starting point of this design. On the one hand, the existing house layout system is a functional, barracks-style layout, and the site lacks recognition, land conservation, and the hierarchy of the courtyard space. How to adapt the space to meet the operational functions of the hotel while preserving the village fabric, courtyard space, and the pattern of the original village houses; at the same time, preserving and extending the openness of the public space and the continuity of the overall space while protecting the privacy of the hotel, was a significant challenge for this design (ArchDaily, 2021). -

List of Facilities –

- Accommodation (Ensuite Bedrooms and Non-ensuite bedrooms)

- Restaurant

- Tea Room

- Book Bar

- Shared Dining Room

- Shared Living Room

- Shared/Public Toilets

- Courtyards

- Artificial Ponds

| Facility Name: Seaweed Bay Health Resort | Facility Location: Weihai, China | |||||

| C A S E S T U D Y O N E | Facility Category | Features | ||||

|

Construction Method |

Components and Materiality |

Natural Features | Facilities | |||

| Health Resort |

Use of raft foundation. The overarching building plan centred around establishing a rational connection between the construction process and the final form. Retrofitted seagrass roofs of old buildings to reflect the regional character while the new buildings with their flat roof highlight a pure masonry volume character. Fusing the old and new buildings is achieved by utilising the same building materials and maintaining similar proportional relationships. |

Ceiling Ganache Board |

Indoors No natural entities except for walling materials, which were all made out of natural materials, including – Brick; Stone; and Clay. |

Private Features Ensuite Bedrooms |

||

|

Floor Stone Flooring | ||||||

|

Wall Brick walling; Stone Walling; and Clay Plastering | ||||||

|

Roof Seagrass Pitch Roofing; and Flat Masonry Roofing | ||||||

|

Fixtures Wall-hung Water fountains |

Outdoors Landscaping Rocks/Stones; Trees; Hedges; Lawns; Stone benches. |

Public features Landscape Stone Benches; Swimming Pool; Courtyards; Book Bar; and Restaurant. |

||||

|

Fittings The nature of the fittings used is not available. | ||||||

|

Green Innovation Technology Use of naturally occurring materials for construction and finishes | ||||||

|

Biomimicry While natural materials constitute most of the facility’s development, they do not qualify as biomimetic. | ||||||

4.2. Case Study 2: Atmantan, Wellness Centre

- Name of Building: Atmantan, Wellness Centre.

- Location: Mulshi, Pune – 412108, Maharashtra, India.

- Year of Construction: N/A.

- Facility Category: Health Resort.

- Other Data:

| Facility Name: Atmantan, Wellness Centre | Facility Location: Mulshi, Pune – 412108, Maharashtra, India. | |||||

| C A S E S T U D Y T W O | Facility Category | Features | ||||

|

Construction Method |

Components and Materiality |

Natural Features | Facilities | |||

| Health Resort |

Strip foundation construction The site’s undulating and rocky terrain influences a high stone wall foundation serving as a plinth. The entire design scheme employed a minimalistic architectural style. |

Ceiling Plaster of Paris (POP) ceiling |

Indoors There were no natural elements, but big window openings and individual balconies gave every interior room a clear visual connection to the outside world. |

Private Features Ensuite Bedrooms; Private Balconies |

||

|

Floor Tile finish and carpets | ||||||

|

Wall Concrete masonry unit walling; Stone Walling; and White and beige wall paint. | ||||||

|

Roof Pitch and gable roof composed of roof tiles and wooden eaves. | ||||||

|

Fixtures Wall-hung Water fountains |

Outdoors Lily ponds; Trees; Shrubs; Adjoining lake and valley |

Public features Landscape Lakeside Benches; Swimming Pools; Dining areas Fitness studios; Gymnasiums |

||||

|

Fittings The nature of the fittings used is not available. | ||||||

|

Green Innovation Technology The facility’s design did not primarily rely on natural materials. Instead, we intentionally integrated the entire scheme with both cultured and naturally occurring green and blue scapes to condition the environment and enhance the overall quality of the facility usage experience. | ||||||

|

Biomimicry The design of the facility is not biomimetic. However, the resort seamlessly converges into the foliaged landscape. | ||||||

4.3. Case Study 3: Salinas Maragogi All-Inclusive Resort

- Name of Building: Salinas Maragogi All-Inclusive Resort.

- Location: Rod. AL-101 Norte, Km 124 - S/N, Maragogi - AL - Brasil.

- Year of Construction: N/A.

- Facility Category: Health Resort.

- Other Data:

| Facility Name: Salinas Maragogi All-Inclusive Resort | Facility Location: Rod. AL-101 Norte, Km 124 - S/N, Maragogi - AL - Brasil | |||||

| C A S E S T U D Y T H R E E | Facility Category | Features | ||||

|

Construction Method |

Components and Materiality |

Natural Features | Facilities | |||

| Health Resort |

Use of raft and stilt foundation types. The construction of the facilities was typically post and beam construction. |

Ceiling Plaster of Paris (POP) ceiling |

Indoors Natural elements are employed, such as brick walls and wooden floor boarding tiles. Visual connections exist between outdoor blue, green, and brown landscapes and interior settings. |

Private Features Ensuite Bedrooms The residences feature private balconies that overlook the garden or swimming pool. |

||

|

Floor Ceramic tile flooring; Wood-board tile flooring | ||||||

|

Wall Brick walling; Matte paint finish | ||||||

|

Roof Raffia Pitch roofing; Roof tile pitch roofing | ||||||

|

Fixtures Wall-hung wooden desk; The bedsides have Bedside cone downlights fitted onto wooden bedhead boards. |

Outdoors Landscaping Rocks/Stones; Trees; Hedges; Lawns; Pool fountains. |

Public features Poolside sitting; Swimming Pool; Natural Pools; Kids Pools; Tree Climbing; Sea bathing; Bars; Eco-friendly hiking; Pavilion; Spa; Minigolf Course; Diving Centre. |

||||

|

Fittings Wall paintings; Furniture is dominantly made out of wood and naturally occurring rope. | ||||||

|

Green Innovation Technology Use of naturally occurring materials for construction and finishes | ||||||

|

Biomimicry Using natural materials for most of the facility’s development is not biomimetic. | ||||||

5.0. Conclusions

References

- Amerio, A., Brambilla, A., Morganti, A., Aguglia, A., Bianchi, D., Santi, F., Costantini, L., Odone, A., Costanza, A., Signorelli, C., Serafini, G., Amore, M., & Capolongo, S. (2020). Covid-19 lockdown: Housing built environment’s effects on mental health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- ArchDaily. (2021). Seaweed Bay Health Resort / Greyspace Architecture Design Studio. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily.com/961235/seaweed-bay-health-resort-greyspace-architecture-design-studio?ad_source=myarchdaily&ad_medium=bookmark-show&ad_content=current-user.

- Atmantan Wellness Centre. (2021). Luxury Health & Wellness Resort Near Mumbai, Pune in India - Atmantan. Atmantan Website. https://www.atmantan.com/.

- Aura, I., Hassan, L., & Hamari, J. (2023). Transforming a school into Hogwarts: storification of classrooms and students’ social behaviour. Educational Review. [CrossRef]

- Cha, J., Jo, M., Lee, T. J., & Hyun, S. S. (2024). Characteristics of market segmentation for sustainable medical tourism. International Journal of Tourism Research, 26(1), e2626. [CrossRef]

- Christoforou, R., Lange, S., & Schweiker, M. (2024). Individual differences in the definitions of health and well-being and the underlying promotional effect of the built environment. Journal of Building Engineering, 84, 108560. [CrossRef]

- Dahanayake, S., Wanninayake, B., & Ranasinghe, R. (2023). Memorable experience studies in wellness tourism: systematic review & bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Spa and Wellness, 6(1), 28–53. [CrossRef]

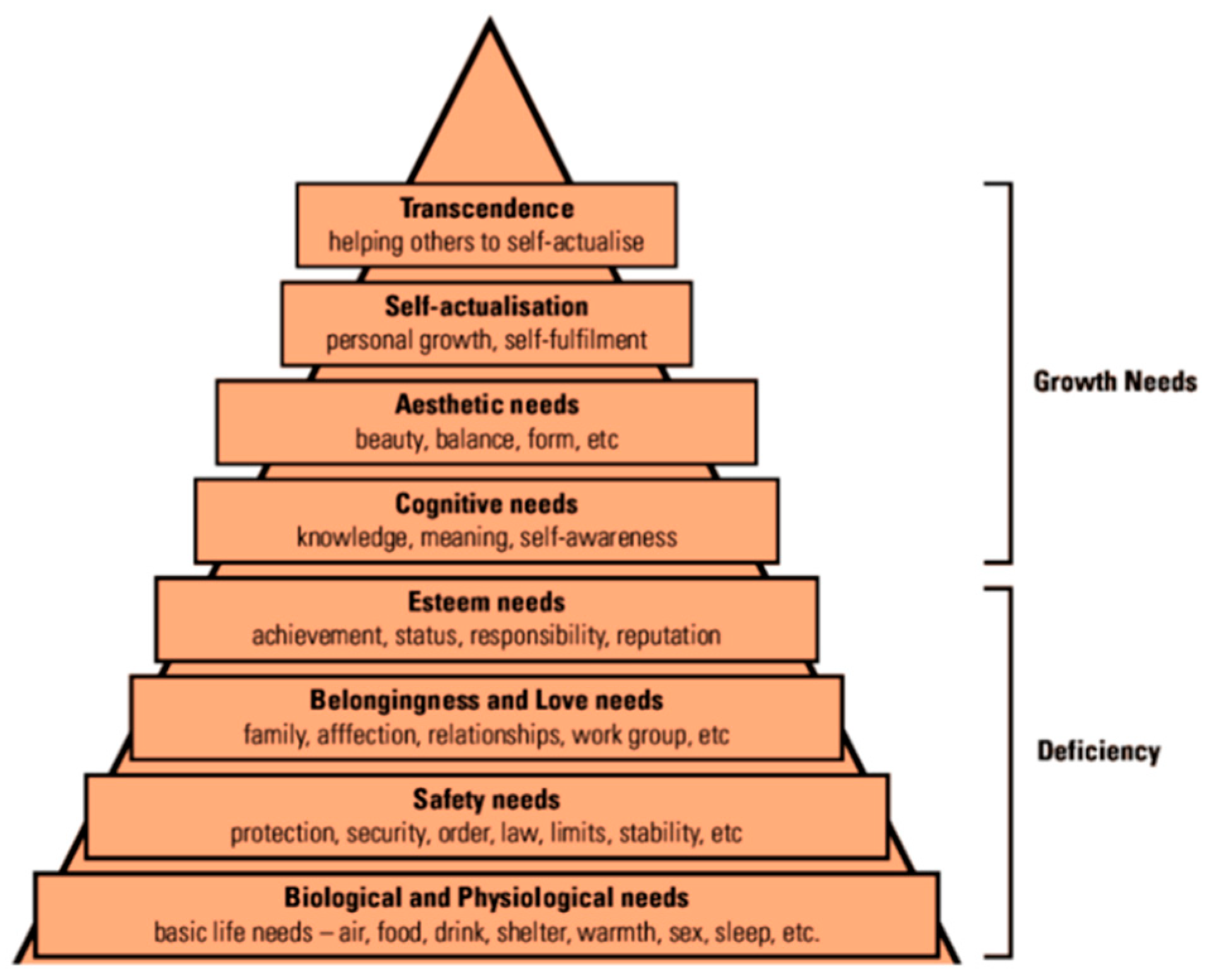

- Dwivedi, P., & Badge, J. (2021). Maslow Theory Revisited-Covid-19 - Lockdown Impact on Consumer Behaviour. Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education (TURCOMAT), 12(2), 2445–2450. [CrossRef]

- Engineer, A., Gualano, R. J., Crocker, R. L., Smith, J. L., Maizes, V., Weil, A., & Sternberg, E. M. (2021). An integrative health framework for well-being in the built environment. In Building and Environment (Vol. 205, p. 108253). Pergamon. [CrossRef]

- Google Map. (2021). ATMANTAN Wellness Centre. https://www.google.com/maps/place/ATMANTAN+Wellness+Centre/@18.5038207,73.5172964,15z/data=!4m5!3m4!1s0x3bc2a1f605a9045f:0xa97b65985939def0!8m2!3d18.5010536!4d73.5137654!5m1!1e4.

- Gürdür Broo, D., Lamb, K., Ehwi, R. J., Pärn, E., Koronaki, A., Makri, C., & Zomer, T. (2021). Built environment of Britain in 2040: Scenarios and strategies. Sustainable Cities and Society, 65, 102645. [CrossRef]

- Hinckson, E. A., Duncan, S., Oliver, M., Mavoa, S., Cerin, E., Badland, H., Stewart, T., Ivory, V., Mcphee, J., & Schofield, G. (2014). Built environment and physical activity in New Zealand adolescents: a protocol for a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 4, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Jones, R., & Yates, G. (2013). The built environment and health: an evidence review. In Glasgow Centre for Population Health - Briefing Paper 11 Concepts Series.

- Jovanovi, O., Wang, Y., Qamruzzaman, M., & Kor, S. (2023). Greening the Future: Harnessing ICT, Innovation, Eco-Taxes, and Clean Energy for Sustainable Ecology—Insights from Dynamic Seemingly Unrelated Regression, Continuously Updated Fully Modified, and Continuously Updated Bias-Corrected Models. Sustainability 2023, Vol. 15, Page 16417, 15(23), 16417. [CrossRef]

- Laddu, D., Paluch, A. E., & LaMonte, M. J. (2021). The role of the built environment in promoting movement and physical activity across the lifespan: Implications for public health. In Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases (Vol. 64, pp. 33–40). W.B. Saunders. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Gao, M., Chu, M., Huang, S., Fang, Z., Chen, T., Lee, C. Y., & Chiang, Y. C. (2023). Promoting the well-being of rural elderly people for longevity among different birth generations: A healthy lifestyle perspective. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1050789. [CrossRef]

- Meloni, M., & Maller, C. (2024). Revitalizing Air: More-than-Human Relations in Urban Health Beyond the Modern-Premodern Binary. GeoHumanities, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K. (2021). Urban planning and quality of life: A review of pathways linking the built environment to subjective well-being. Cities, 115, 103229. [CrossRef]

- Nathan, A., Villanueva, K., Rozek, J., Davern, M., Gunn, L., Trapp, G., Boulangé, C., Boulangé, B., & Christian, H. (2018). The Role of the Built Environment on Health Across the Life Course: A Call for CollaborACTION. American Journal of Health Promotion, 32(6), 1460–1468. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, I., & Balderas-Cejudo, A. (2023). Tourism towards healthy lives and well-being for older adults and senior citizens: Tourism Agenda 2030. Tourism Review, 78(2), 427–442. [CrossRef]

- Potter, D., & Valera, P. (2024). Health Is Power, and Health Is Wealth: Understanding the Motivators and Barriers of African American/Black Male Immigrants With Gastrointestinal Conditions. American Journal of Men’s Health, 18(1). [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q.-W., Li, J., Li, J.-Y., & Xu, Y. (2020). Built form and depression among the Chinese rural elderly: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 10, 38572. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J. D., Ada, M. S. D., & Jette, S. L. (2021). NatureRx@UMD: A Review for Pursuing Green Space as a Health and Wellness Resource for the Body, Mind and Soul. In American Journal of Health Promotion (Vol. 35, Issue 1, pp. 149–152). SAGE Publications Inc. [CrossRef]

- Sturge, J., Nordin, S., Sussana Patil, D., Jones, A., Légaré, F., Elf, M., & Meijering, L. (2021). Features of the social and built environment that contribute to the well-being of people with dementia who live at home: A scoping review. Health & Place, 67, 102483. [CrossRef]

- Svensson, M. (2021). Walking in the historic neighbourhoods of Beijing: walking as an embodied encounter with heritage and urban developments. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 27(8), 792–805. [CrossRef]

- Timm, S., Gray, W. A., Curtis, T., & Chung, S. S. E. (2018). Designing for Health: How the Physical Environment Plays a Role in Workplace Wellness. In American Journal of Health Promotion (Vol. 32, Issue 6, pp. 1468–1473). [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, R. (2021). Healthy, happy places - a more integrated approach to creating health and well-being through the built environment? British Medical Bulletin, 140(1), 62–75. [CrossRef]

- Vagtholm, R., Matteo, A., Vand, B., & Tupenaite, L. (2023). Evolution and Current State of Building Materials, Construction Methods, and Building Regulations in the U.K.: Implications for Sustainable Building Practices. Buildings 2023, Vol. 13, Page 1480, 13(6), 1480. [CrossRef]

- Verderber, S., Koyabashi, U., Cruz, C. Dela, Sadat, A., & Anderson, D. C. (2023). Residential Environments for Older Persons: A Comprehensive Literature Review (2005–2022). In Health Environments Research and Design Journal (Vol. 16, Issue 3, pp. 291–337). SAGE PublicationsSage CA: Los Angeles, CA. [CrossRef]

- Younis, G. M. (2019). A theoretical framework of design strategies that stimulate the process of self-healing for occupations. Zanco Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences, 31(s3), 95–105. [CrossRef]

- Zaman, A., Huang, F., Jiang, M., Wei, W., & Zhou, Z. (2020). Preparation, Properties, and Applications of Natural Cellulosic Aerogels: A Review. Energy and Built Environment, 1(1), 60–76. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W., Schröder, T., & Bekkering, J. (2022). Biophilic design in architecture and its contributions to health, well-being, and sustainability: A critical review. In Frontiers of Architectural Research (Vol. 11, Issue 1, pp. 114–141). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).