1. Introduction

In recent years, the development of the Internet of Things (IoT), complemented by advancements in communication technologies, has enabled a vast array of mobile devices (MDs)—including cameras, sensors, and wearable devices—to collect and exchange data [

1,

2]. This proliferation has given rise to numerous application scenarios that leverage wireless devices, such as autonomous driving, face recognition, Virtual Reality (VR), and e-health [

3,

4]. However, these applications often demand substantial computational power and low latency, presenting challenges for MDs, which typically have limited computing capabilities and finite battery life. Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) has risen as a promising solution to these challenges. By offloading computationally intensive tasks to MEC servers, MDs with constrained resources can markedly enhance their computational capacity and reduce latency.

However, wireless devices often have limited battery capacity, which cannot sustain prolonged operation. Consequently, the frequent replacement of MDs’ batteries presents a significant challenge. Wireless Power Transfer (WPT) has emerged as an effective solution to this challenge [

5,

6]. WPT utilizes a Hybrid Access Point (HAP) to broadcast Radio Frequency (RF) energy that can be harvested by wireless devices. By integrating Energy Harvesting (EH) technology, these devices can convert the captured RF signals into usable electrical energy, thereby recharging their batteries [

7]. This harvested energy enables the devices to perform computational tasks either locally or by offloading them to MEC servers. The integration of wireless power and edge computing technologies in Wireless Powered Mobile Edge Computing (WPMEC) networks significantly extends the battery lifespan of wireless devices and markedly enhances their computational capabilities.

In addition to battery limitations, the double-near-far effect can significantly impact network performance, with devices far from the HAP experiencing poor channel conditions [

8]. To counteract this issue, a User Cooperation (UC) mechanism has been implemented. In this mechanism, devices that are in close proximity to the HAP act as relays, forwarding signals for those located at a greater distance. This strategy not only mitigates the inefficiency of remote nodes offloading tasks directly to the Access Point (AP) but also optimizes the utilization of idle computational resources within the network, thereby enhancing the overall computational efficiency of the system. For example, the work in [

9] demonstrates how user cooperation can boost the computational efficiency of a WPMEC system under dynamic channel conditions and varying task arrivals. Additionally, other studies, such as [

10,

11], have shown that user cooperation can effectively reduce the impact of the double-near-far effect. However, the aforementioned studies has not yet explored the potential of Backscatter technology to improve energy efficiency further.

Backscatter Communication (BackCom) has garnered significant attention in recent years due to its innovative approach to wireless communication [

12]. In BackCom systems, the transmitter operates in full-duplex mode, functioning in a passive mode. It modulates and reflects the incident signal to the receiver, eliminating the need to generate a carrier frequency, while simultaneously harvesting energy to support its circuitry consumption [

13,

14]. This approach contrasts with traditional Active Communication (AC), where the transmitter first harvests energy and then uses this harvested energy to transmit data, adhering to the harvest-then-transmit (HTT) protocol. Generally, AC consumes more energy than BackCom, although it can achieve a higher data transfer rate. The trade-offs between EH and data transfer are inherent in both BackCom and AC.

A number of researchers have advanced the concept of integrating BackCom and AC paradigms to improve the energy efficiency(EE) of WPMEC systems [

10,

15,

16]. However, existing studies frequently focus on scenarios limited to a single time slot, positing that channel conditions and user data arrivals remain constant. In real MEC networks, the environment is often volatile, with user data arrivals and wireless channel states exhibiting inherent stochastic and fluctuating characteristics, which precludes the precise acquisition of prior knowledge about these dynamic elements. Therefore, the development of efficient algorithms aimed at optimizing long-term energy utilization efficiency and ensuring system queue stability introduces a more substantial challenge and holds greater practical significance.

In this paper, we tackle the long-term EE maximization for a Backscatter assisted WPMEC network with user cooperation by jointly optimizing the wireless powered time fraction, Backcom offloading time fraction, AC offloading time fraction, offloading data size and transfer power of MDs. The problem presents significant challenges in two aspects: (1) The randomness of task arrivals and fluctuating wireless channel states impose challenges to achieving optimal EE while ensuring the stability of queue system; (2) The integration of BackCom and AC brings a strong coupling of energy harvest time and task offloading. To address these challenges, we formulate a stochastic optimization problem and propose an efficient, low-complexity algorithm by leveraging techniques such as the Dinkelbach method and the Lyapunov optimization framework. We first transform the sequential decision problem into a deterministic problem for each time slot by leveraging the drift-plus-penalty technique, obtaining a non-convex optimization sub-problem. Then, we convert the non-convex problem into a convex optimization problem by using variable substitution, which allow for efficient solution. We propose a low-complexity dynamic EE maximization algorithm that operates online without requiring prior system information.

The primary contributions of this paper are listed as follows:

We introduce a dynamic task offloading model to optimize EE for a WPMEC network with integration of BackCom and AC communication under user cooperation, taking into account the randomness of task arrival and time-varying wireless channels. Our model can balance the trade-off between energy efficiency and system queues stability, and mitigate the impact of double-near-far effect. Additionally, we have investigated using variable data weighting to motivate proximal users to relay data for distant users.

We propose an online control algorithm to maximize the EE metric of WPMEC network by determining the time fraction allocation, data offloading, and transmission power at each time slot. To address the coupling of user cooperation and control decision over time period, we leverage Dinkelbach’s method and the Lyapunov optimization theory to decouple the original problem into a deterministic sub-problem, then convert the sub-problem into a convex one for efficient solution.

We conduct extensive simulation experiments to verify the effectiveness and practicality of our algorithm, accessing the impact of the control parameter V, bandwidth, gap, task arrival rate. The results demonstrate that our proposed algorithm outperforms the benchmark algorithms by about 23%, and achieve a theoretical energy efficiency-stability trade-off of .

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section II presents the details of model of Backscatter-assisted WPMEC system. In Section III, we formulate a stochastic programming optimization problem aimed at maximizing energy efficiency. Section IV details the application of the Dinkelbach’s method and Lyapunov optimization techniques to simplify the problem, including the algorithm design and theoretical performance analysis. Section V presents an extensive simulation-based evaluation of the proposed algorithm’s performance. Finally, we conclude the paper and suggest directions for future research in Section VI.

1.1. Related Work

The combination of WPT with MEC networks, as an efficient solution for wireless devices to augment their energy and computational capacities, has been extensively studied by recent researches [

17]. Ernest and Madhukumar [

18] proposed an energy efficiency maximization algorithm based on multi-agent deep reinforcement learning to achieve maximum energy efficiency in MEC-supported vehicular networks, with jointly considering transmission and computation latencies outperforming existing strategies. Zhang et al. [

19] proposed an algorithm optimizing charging time and data offloading rates for WPT-MEC IoT sensor networks to improve computational rates in scenarios. Li et al. [

7] studied the system latency minimization problem for an Intelligent Reflecting Surfaces(IRS)-assisted multi-ID MEC system, and presented a hybrid multiple access scheme and optimization framework combined with FDMA and NOMA technologies. Additionally, in [

20], the authors introduce a deep reinforcement learning-based approach for WPT-aided mobile edge computing to dynamically adapt to real-time changes, make swift decisions, and optimize both task offloading and energy resource allocation. Our previous research [

21] introduced an online control algorithm for dynamic task offloading in WPMEC networks under dynamic network conditions, designed to maximize long-term system energy efficiency. However, the aforementioned work did not take into account the use of Backscatter technique to further enhance the energy utilization efficiency of wireless power transfer.

To mitigate the double-near-far effect and fully utilize available resources, many researchers employ user cooperation mechanism [

11,

21,

22,

23]. For instance, He et al. [

23] presented a user cooperation scheme, aiming to maximize the network’s total throughput by jointly optimizing the local computing frequency, transmit power, task distribution, and time allocation. Similarly, Wang et al. [

22] introduced a user cooperation mechanism for a NOMA assisted WPT-MEC network, designed to minimize overall system energy consumption. They employed the Lagrangian method to transform the inherently non-convex optimization challenge into a tractable convex problem. Sun et al. [

24] proposed an iterative optimization algorithm for minimizing end-to-end latency in an MEC network supporting IoT applications, by jointly optimizing user association and resource allocation in a three-phase operation protocol. Su et al. [

11] explored optimizing the energy beamforming and resource allocation to enhance computation efficiency for WPMEC system with the integration of user cooperation and non-orthogonal multiple access(NOMA), taking into account non-linear energy harvesting model. He et al. [

25] proposed a dynamic control algorithm based on Lyapunov optimization framework to maximize the computation rate for a sustainable WPMEC under power constraints.

In recent years, BackCom has become an effective method for enhancing network energy efficiency and is widely used by researchers [

10,

16,

26]. Ye et al. [

26] introduced a bisection-based iterative algorithm for minimizing data offloading and computing delays in a WPMEC network with hybrid BackCom and active transmissions (AT) for IoT networks. Shi et al. [

27] proposed a scheme for maximizing the weighted sum of computation bits in a Backscatter-assisted WPMEC network, considering a practical non-linear EH model with hybrid HTT and Backscatter communications. Lyu et al. [

28] considered user-cooperation schemes for two types of wireless devices which can support different communication modes, i.e., Backscatter and HTT, enhancing overall communication and energy efficiency through joint optimization of time scheduling, power allocation, and energy beamforming. Wu and He [

16] proposed an efficient iterative algorithm for EE maximization in a multi-access WPMEC system with the help of a relay. However, none of these works did not considered the user cooperation and the volatile MEC network environment.

Different from the above research, this paper addresses the problem of hybrid communication modes (e.g., BackCom and AC) and user cooperation for EE maximization in a volatile WPMEC network, without any information about the future. Compared to [

10], our approach considers both nodes capable of processing their own incoming data simultaneously, and we introduce weighted incentives to motivate proximal nodes to assist distant nodes in offloading computational tasks. We account for dynamic factors, including random task arrivals and fluctuating wireless channel states, the prior knowledge of which is difficult to pinpoint accurately, making task offloading and resource allocation significantly challenging. Moreover, the coupling of dynamic battery levels and wireless charging time further complicates the problem.

2. System Model

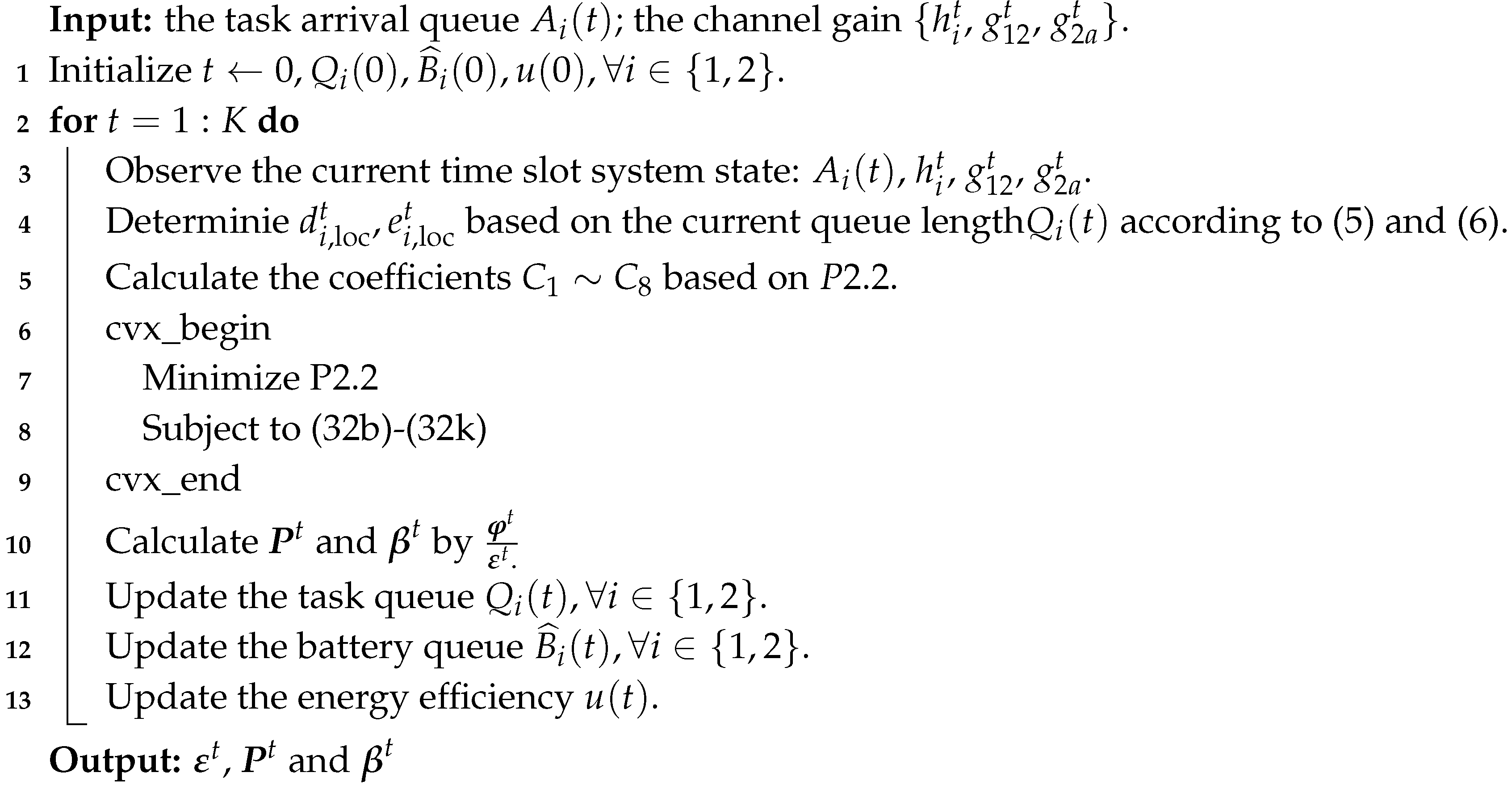

We consider a typical WPTMEC network comprises two MDs and a HAP, depicted as

Figure 1. The HAP directly connect with an MEC server to provide computation task offloading services and equipped with an RF energy transmitter to support wireless powered to MDs.

, one of the MDs, is located at a significant distance from the HAP. In contrast,

, the second MD, is in a more advantageous position due to its proximity to the HAP and acts as an intermediary. Both

and

are equipped with both a BackCom circuit and an AC circuit, enabling them to select between backscatter and active communication modes.

The WPMEC system employs a Time Division Duplex (TDD) method to alternate between communication and energy harvesting phases. Time Division Multiple Access (TDMA) technique is utilized to avoid signal interference [

29]. The WPMEC system operates in a discrete time-slot mode over a time horizon period, with each time slot set to last

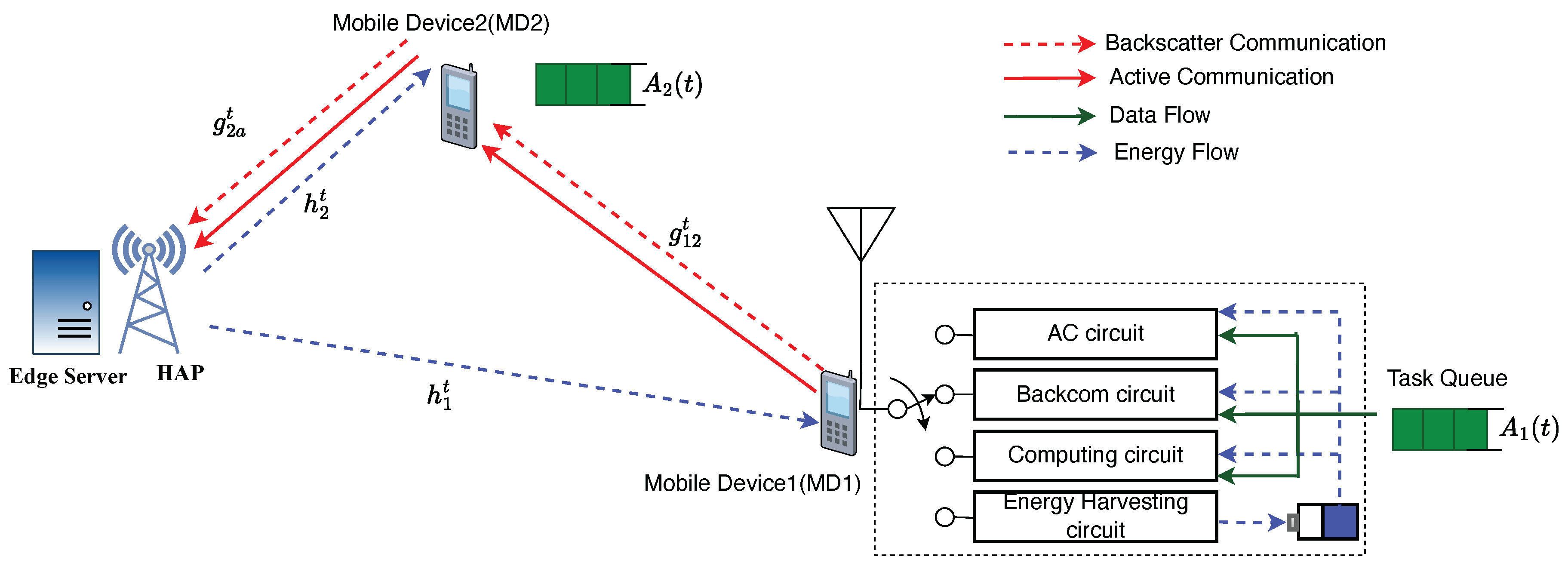

T seconds. As depicted in

Figure 2, each time slot is further divided into five time fractions dedicated to energy harvesting and task processing for the different MDs. At the start of each time slot, both MDs initiate the capture of RF signals transmitted by the HAP for the purpose of energy harvesting. A partial offloading strategy is adopted, which permits the flexible offloading of a portion or the complete set of computational data to a remote device. Owing to the terrible channel conditions between the

and the HAP, along with the compounded near-far effect, directly offloading tasks to HAP is infeasible for the

, such that the

offloads tasks to the

, and the

then forwards them to HAP.

Both MDs are equipped with BackCom and AC circuits for task offloading during the communication process. At each time slot, the BackCom mode is firstly used for tasks offloading. During intervals and , computation tasks date from the remote device MD1 is offloaded to MD2, which then offloads these task data to the HAP. Similarly, during intervals and , the offloading process is carried out using the AC mode. In the final time allocation , because the computation result data is typically small, this time slot can be considered negligible and ignored.

The primary symbols and definitions used are listed in

Table 1.

2.1. Energy Harvesting Model

The HAP, equipped with a reliable power source, is responsible for the transmission of RF energy to the array of MDs dispersed within its service area. In the initial phase, the HAP broadcasts RF signals to all MDs for a duration of

. Subsequently, MD1 offloads tasks to MD2 during the time fraction

using BackCom, while MD2 can simultaneously harvest energy. In a similar fashion, MD2 offloads tasks to the HAP during the time fraction

using BackCom, and MD1 harvests energy. Let

and

denote the harvested energy of

and

in the first phase, respectively. Thus, we have [

10]

and

where

represents the energy conversion efficiency,

denotes the RF transmit power of the HAP.

and

represent the channel gain from the HAP to

and

respectively, which remain constant within the same time slot and vary across different time slots.

2.2. Dynamic Queues Model

To simulate the dynamic changes in user task data arrival and node battery levels, we have introduced the dynamic queuing model. Both

and

maintain a buffer queue for caching incoming task data, which is processed on a first-in, first-out (FIFO) principle. Let

denotes the queue lengths of

and

at slot

t, respectively, which can be observed at the beginning of the time slot. The backlog of task queue

update as follows:

where

represents the raw task data arriving at the

data queues during time slot

t. We assume that the task arrival is an arbitrary process over time, the is a upper-bound by

.

,

represent the offloading task data and the local processing data at

, respectively.

Similarly, we assume that MD nodes are equipped with batteries and maintain a battery energy level queue. The energy captured through wireless charging is first stored in the batteries, and the battery power is consumed for local computing and task offloading. Concurrently, the battery energy level has an upper limit

and a lower limit

. The

level is essential to sustain the basic operations of the MD IoT system [

29]. Therefore, the battery energy of the MD nodes dynamically changes according to the following equation

where

and

represent the energy consumption for local computing and task offloading, respectively. The total energy harvested by

at slot

t is given by

, where

is as previously defined, and

denotes the energy harvested during BackCom data transmission.

2.3. Local Computing Model

Upon task arrival at a node, local processing is prioritized; task offloading is considered only when local processing is not feasible. Since each MD is equipped with a battery, the maximum duration for local computation is denoted by

T. Let

and

denote the local CPU frequencies of

and

,

and

denote the CPU cycles required to process one bit of task at the

and

, respectively. Furthermore, the maximum amount of local computation data at

cannot exceed the current backlog of

. Thus, the amount of locally computed task data can be expressed as

and the corresponding energy consumption is [

10]

where

denotes the computing energy efficiency parameter of

[

10]. The expression

represents the power consumption used for processing all current task data in queue

.

2.4. Task Offloading Model

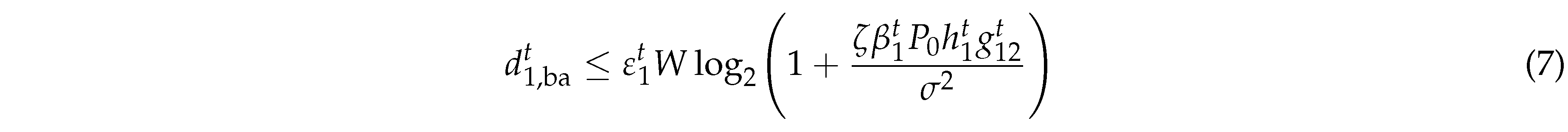

2.4.1. Backcom Data Transmission

During

,

offload tasks to

by Backcom. Let

denote the reflection coefficient of

, where

represents the fraction of the received signal that is utilized as a carrier for data transfer, and the remaining fraction

is allocated for energy harvesting [

30]. Let

represent the channel gain between

and

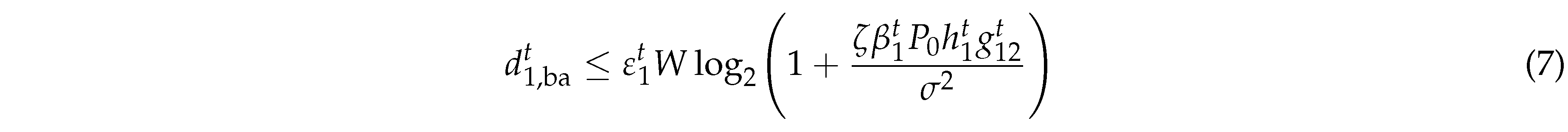

. According to Shannon’s theorem [

31], the amount of tasks offloaded from

to

satisfies [

10]

where

represents the performance gap reflecting real modulation [

13],

is the noise power. The corresponding energy consumption by circuit is

where

is the circuit power consumption of

by BackCom, which is a constant value depending on the circuit structure. Due to utilizing BackCom technology, data transmission and energy harvesting can be performed simultaneously. Thus, the energy harvested for

during

is as [

10]

After receiving the tasks offloaded from

,

will relay a portion of these tasks to the HAP as a relay. Note that

will also offload its own tasks to the HAP. At time

, the task data transmitted by

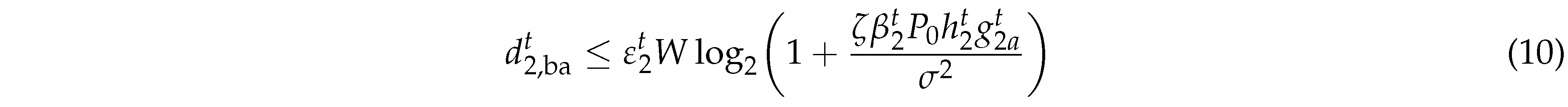

through BackCom is constrained as follows

where

is the reflection coefficient of the BackCom at

.

represents the channel gain from the HAP to the

at time slot t, and

denotes the channel gain from the

to the HAP at time slot

t. The corresponding energy consumption is

where

is the circuit power consumption of

by BackCom. The energy harvested by Backcom during

is

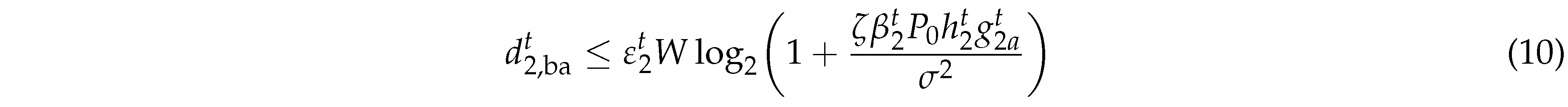

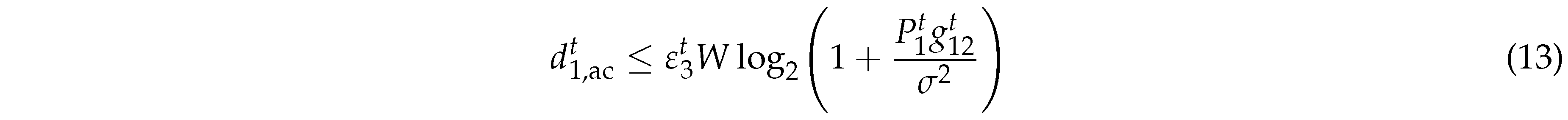

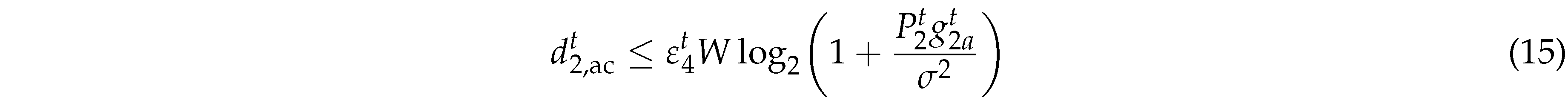

2.4.2. AC Data Transmission

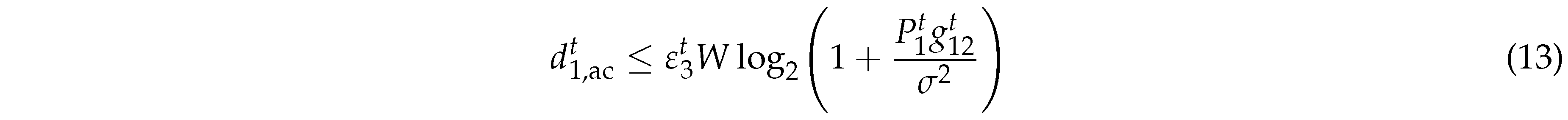

After the BackCom offloading is completed, the AC mode offloading is initiated, which proceeds through an offloading process similar to that of BackCom. The AC mode can achieve a higher data transmission rate, but it is incapable of energy harvesting during the offloading phase. During the time fraction

, the upper limit of the amount of task from

offloading to

can be expressed as

where

represents the transmit power allocated to AC at

[

10],

is the noise power and

represents the channel gain from

and

. The corresponding AC offloading energy consumption is

where

denotes the circuit power of

through AC which is a constant value [

10].

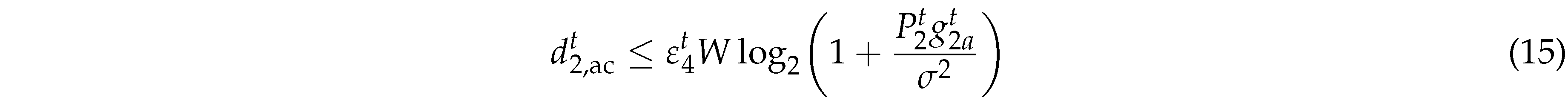

The upper limit of the amount task offloading from

to HAP by AC during

is given by

where

denotes the transmit power of the

through AC. Let

denotes the circuit power of

through AC. The energy consumed for task offloading AC at

in slot

t is

2.5. Network Stability and Utility

For a dynamically changing WPMEC network system, maintaining system stability is crucial due to the stochastic arrival of tasks and the dynamic changes in the channel environment [

32]. Therefore, we first provide the definition of system queue stability as follows.

Definition 1.

(Queue Stability): A discrete task data queue is strong stable [32] if it satisfies

The energy efficiency of WPMEC system is defined as the ratio of the sum of weighted processed tasks to the total energy consumption. Specifically, the total accomplished tasks

and the total energy consumption

of WPMEC network at slot

t can be represented as follows, respectively

and

where

and

represents the task weights of

and

respectively.

represent the total offloading task data at

, and

represent the total energy consumption of offloading task at

.

Definition 2.

(Utility-Energy Efficiency ): The network utility is defined as the time-averaged amount of computation data achieved per unit of energy consumed [33]. This is expressed as the ratio of the long-term processed data to the total energy consumption, as follows:

3. Probelm Formulation

In this paper, we aim to design a dynamic offloading algorithm to maximize the

with constraint of the system queue stability, by making decisions on time allocation

, power allocation

, reflection coefficients

and the amount of offloaded tasks

at each time slot

t. Simultaneously, our algorithm should ensures the stability of the system network when faced with randomly arriving task loads and dynamically changing wireless channel conditions. By denoting

,

,

, and

the maximization of

for a Backscatter-assisted WPMEC with user cooperation can be formulated as the following problem (P0):

where constraint (20b) ensures the total time allocation does not exceed the time slot. Constraint (20c) ensures that the energy consumed is less than the energy in the battery. Constraints (20d) guarantee the stability of data queues. Constraint (20e) indicates that the amount of processed task in the current time slot must not exceed the current queue length. denotes the maximum data processing limits for the

and

within time slot

t. Constraint (20f) ensures that the data offloaded from the

can be processed within the same time slot. Constraints (20g) denotes the maximum offloading data depending on the channel condition. The problem is a fractional stochastic programming issue, which presents significant challenges due to several aspects: (1) The randomness of task arrivals, the fluctuating wireless channel state, and the dynamic battery level introduce stochastic factors to the optimization challenge; (2) The temporal coupling in the time fraction and energy consumption exhibited by BackCom and AC poses a considerable challenge in determining the allocation of offloading time.

To simplify problem P0, we employ the Dinkelbach‘s method [

34] to transform the original problem into a more tractable one. Let

denote the optimal value of

, we derive the following Theorem 1.

Theorem 1.

The optimal is achieved if and only if

Proof. For brevity, here we omit the proof details. See Theorem 1 in [

33]. □

Since

is unknown during the solution process, (

Section 3) is still infeasible to tackle. In accordance with the methodology employed in [

33], we introduce a new parameter

and define it as

We set

at the beginning of the problem. Replacing

in (

Section 3), the problem P1 can be transformed into

where

is a given parameter that should be updated through the resolution process. It should be noted that

obtained by (

22) will get closer to

as time goes by [

33]. Therefore, this transformation is reasonable and has the same optimal solution with P0. While Problem P1 is more manageable than Problem P0, it still faces several challenges The constraints (20c) and (20d), along with the equation (

4), result in an interdependence of battery levels across various time slots throughout the period, which means that the current energy consumption affects future battery levels. Moreover, The unpredictability of the stochastic task arrivals and the fluctuating channel states add another complexity to the problem. The difficulty in accurately forecasting these elements leads to an inherent temporal coupling in the decision-making process.

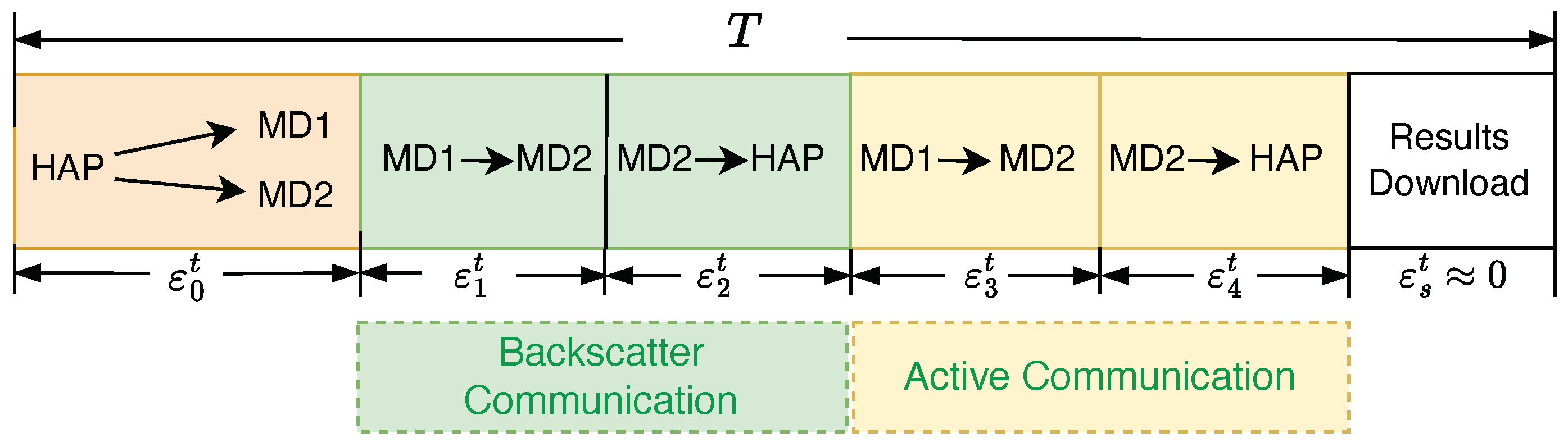

5. Simulation Results

In this section, we evaluate the performance of our propose algorithm for a Backscatter-assisted WPMEC system with user cooperation through extensive numerical simulation. The experiments are conducted on a high-performance platform equipped with a 2.10 GHz Intel(R) Xeon(R) Silver 4116 CPU and four GeForce RTX 2080 Ti GPUs, ensuring efficient simulation execution. We employed the free-space path loss model to simulate signal propagation, where the average channel gain

is calculated by the following formula [

4]:

where

(antenna gain),

MHz (carrier frequency),

(path loss exponent), and

represents the distance between nodes (in meters). The dynamic channel gains for WPT and task offloading, following the Rayleigh fading model, are represented by the vector

. In the model, the channel fading factors

all follow an exponential distribution with an expectation of 1, simulating the natural variability of wireless channels. For the sake of model simplification, we assume that the vector of fading factors remains constant at

within each time slot, thereby considering the channel gain to be static during that slot.

At each time slot

t, the expected arrival rates of computational tasks

satisfy

. It is assumed that

follow an exponential distribution, where the rate parameters

and

correspond to 1.2 and 1.5, respectively. Other simulation parameters are detailed in

Table 2.

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of our algorithm, we conducted comparative simulations with three representative benchmarks as follows:

(1) UC With the AC scheme: All task offloading for

and

are restricted to the use of the AC mode exclusively [

9], with the BackCom mode prohibited. This is equivalent to setting the time offsets

and

to zero in problem

.

(2) UC with the BackCom scheme: Users opt to complete computational tasks exclusively via the BackCom mode. Specifically, the HAP continuously broadcasts RF energy to the users throughout the time slot. This scheme can be implemented in scenario by setting and .

(3) Without UC With Integrated BackCom and AC scheme:

and

communicate directly with the HAP, offloading tasks via integrated BackCom and AC [

37]. Due to poor channel conditions between

and HAP, it may harvest less energy and offload a smaller portion of tasks. Additionally, devices can complete their computational tasks through local computation throughout the entire time slot.

To ensure fairness, it is crucial to preserve the stability of network queues in all schemes. Thus, the three baseline methods previously discussed are executed within the framework of Lyapunov optimization.

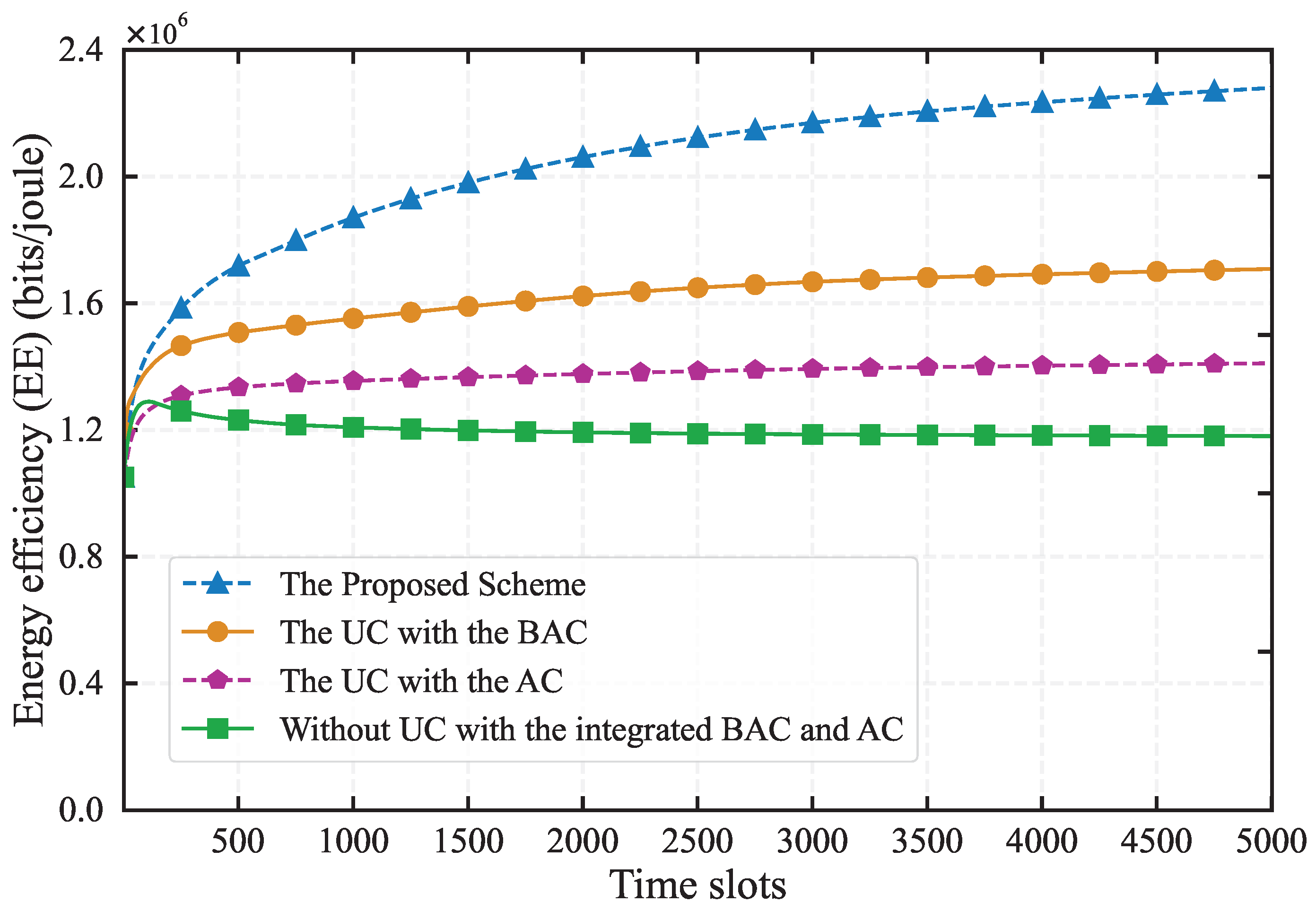

Figure 3 demonstrates the performance comparison of EE under different schemes, with parameters set as

,

, and

. It can be observed that our proposed algorithm achieves the best performance of EE, followed by UC with the BackCom, with UC with the AC ranking third. The method without user cooperation that integrates BackCom and AC performs the worst. Compared to the other three schemes, our proposed algorithm has improved the EE by 23%, 38%, and 48%, respectively. This superior performance highlights the advantage of integrating both BackCom and AC. The scheme of UC with the BackCom, suffers from limited transmission capability when

is small, leading to poor performance. Although UC with AC can transmit sufficient data, its high circuit power consumption results in it ranking third. Moreover, the EE of the non-cooperative scheme with integrated BackCom and AC is also low. This indicates that even with the integration of BackCom and AC, poor channel conditions between

and HAP can still limit energy harvesting and task offloading. This further emphasizes the importance of user cooperation in enhancing the performance of remote users.

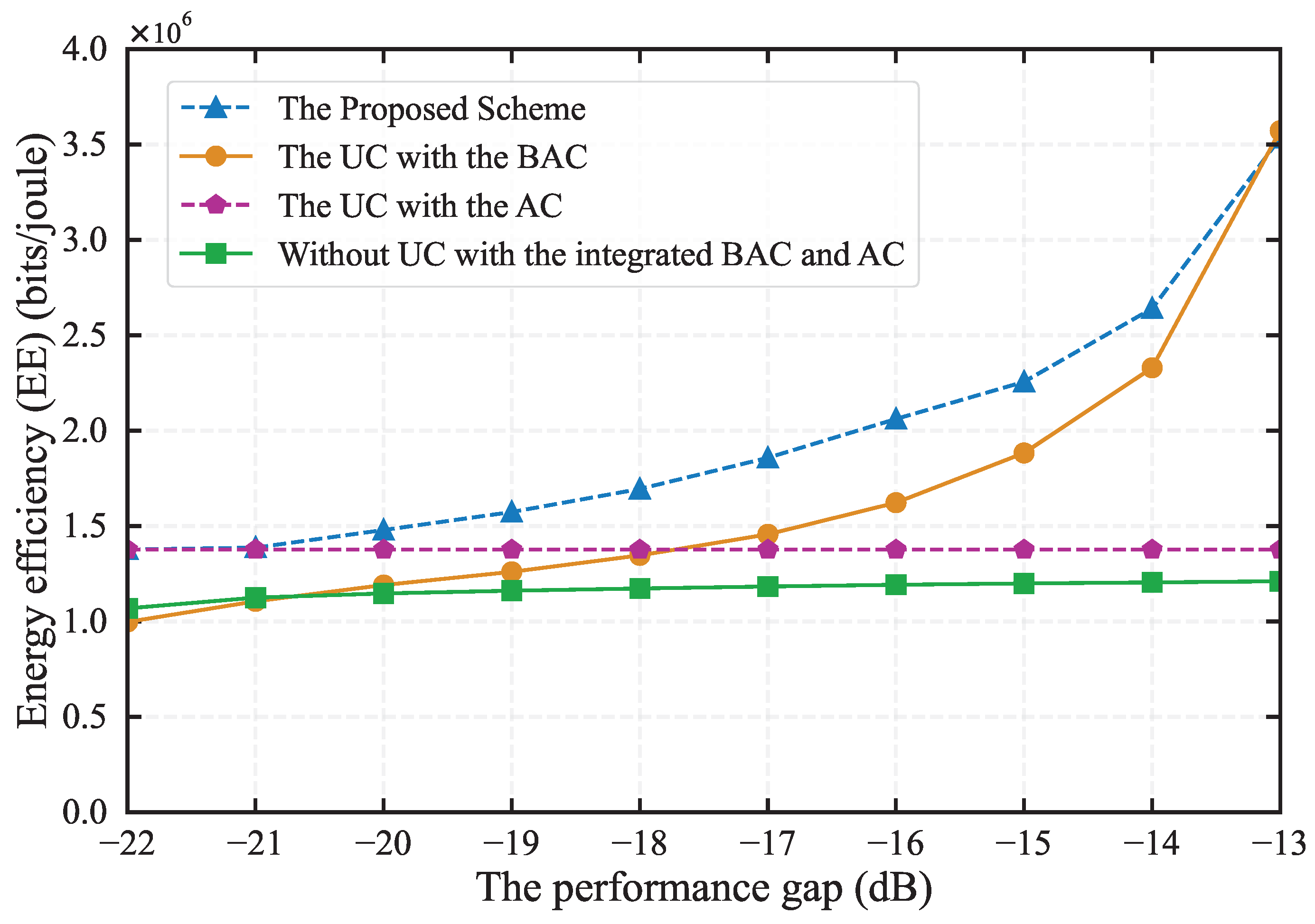

Figure 4 illustrates the impact of controlling the performance gap

on EE. The EE for the other three schemes improve with an increase in

, contrasting with the AC scheme’s stable EE. Our proposed scheme consistently delivers the best system performance. With

exceeds -17dB, the BackCom scheme outperforms the AC scheme in EE, prompting the system to favor the BackCom mode. Upon reaching a higher threshold, the BackCom scheme’s EE matches that of our proposed scheme, leading to its predominant use by users. Conversely, when

below -21dB, our scheme defaults to the AC mode. The non-cooperative integrated BackCom and AC scheme sees minimal performance gains due to suboptimal channel conditions. Overall, the proposed scheme outshines others in flexibility and adaptability, adeptly tuning to varying

levels for optimal EE.

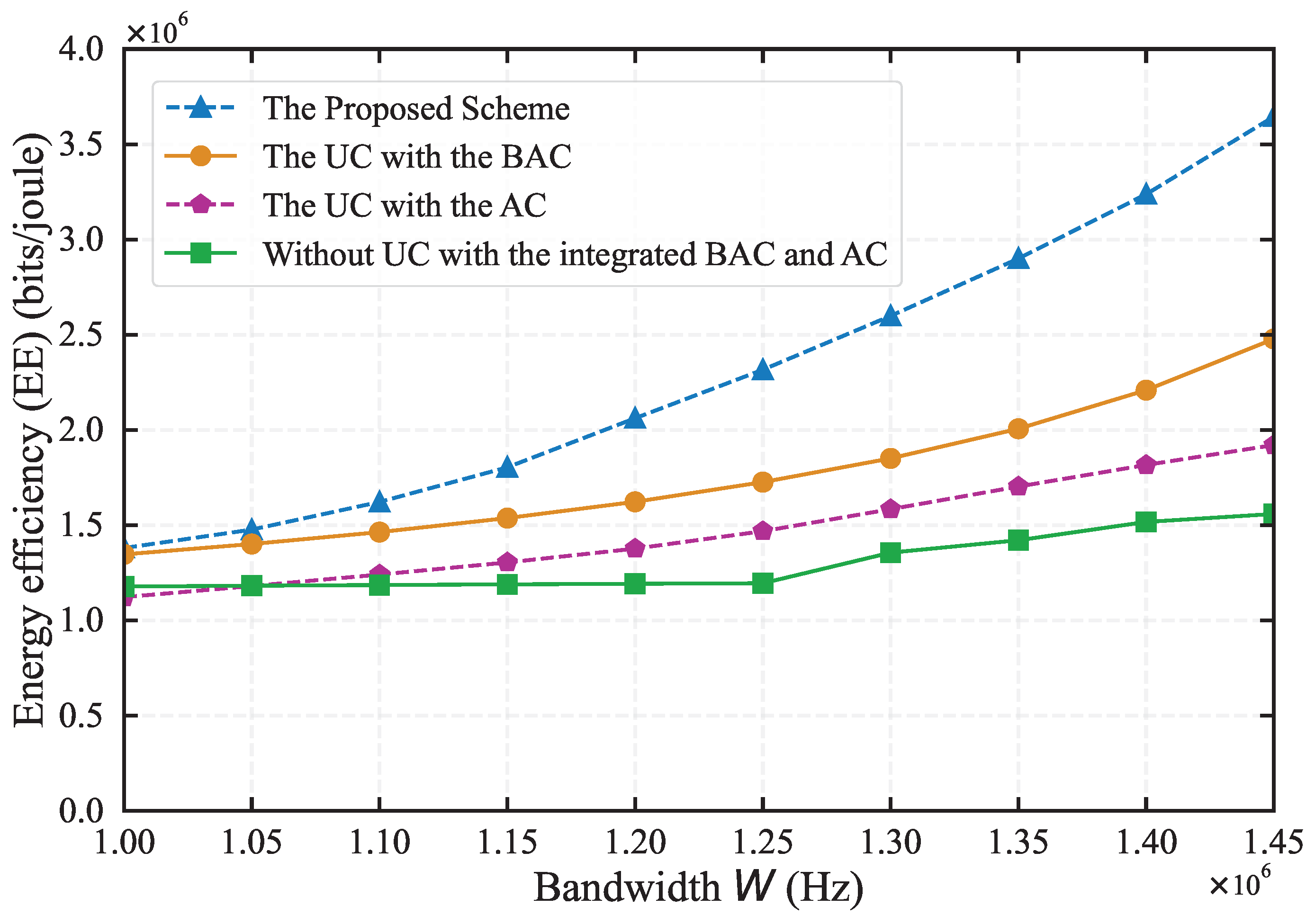

In

Figure 5, the maximum time slot is set to 2000, the maximum time slot is set to 2000, achieving a stable solution for the algorithm within this time period. We demonstrate that adjustments of network bandwidth significantly impact the performance of various algorithms. As shown in

Figure 5, within the bandwidth range of [1.00, 1.45] ×

Hz, the EE of all schemes increases with the expansion of bandwidth. This is attributed to the increased bandwidth allows more tasks to be transmitted to the edge server for processing using edge computing resources. Our proposed scheme exhibits superior performance across different bandwidth conditions, particularly as the bandwidth approaches 1.45MHz, where its energy efficiency advantage becomes especially pronounced, significantly surpassing other baseline algorithms. This not only demonstrates the high adaptability of our proposed scheme in bandwidth control but also highlights its efficient utilization of network resources in high-bandwidth environments, achieving maximum energy efficiency.

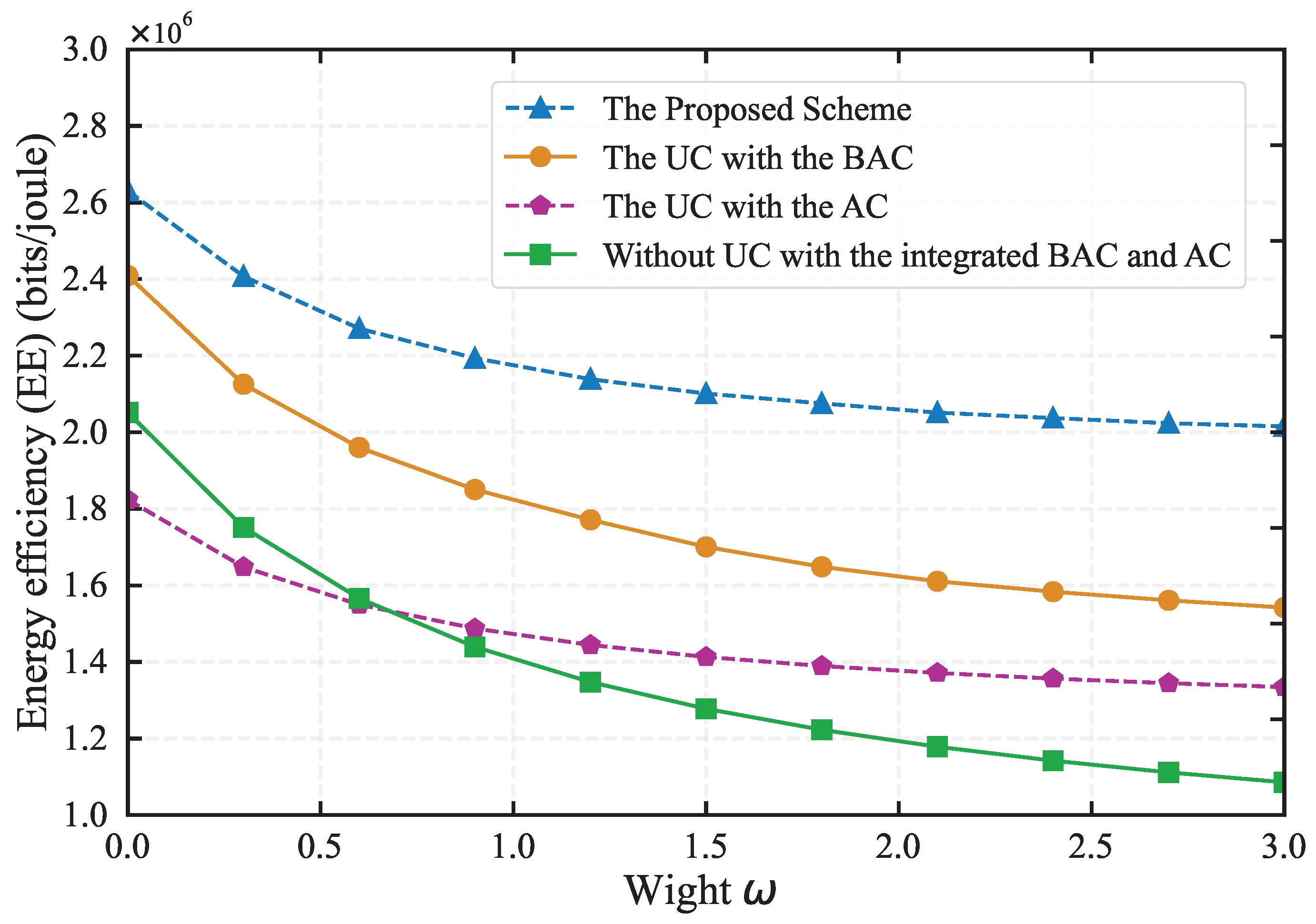

In

Figure 6, we evaluated the system performance of various algorithms under different weight configurations, where the weight

varies in the range [0, 3], with

and

. As

increases, the EE of all schemes generally declines. This is because an increase in weight

implies a higher priority assigned to the tasks of

, leading the system to allocate more resources to

tasks, thereby reducing overall energy efficiency. Our algorithm demonstrates optimal EE across all weight settings. Specifically, when

, it shows an energy efficiency improvement of 23%, 38%, and 46% compared to other algorithms, respectively. This indicates that our algorithm can more effectively leverage the advantages of the UC scheme integrated with BackCom and AC.

Figure 6 also reveals that in practical applications, excessively high weights for edge node devices may rapidly degrade network performance, thereby emphasizing the importance of proper weight distribution.

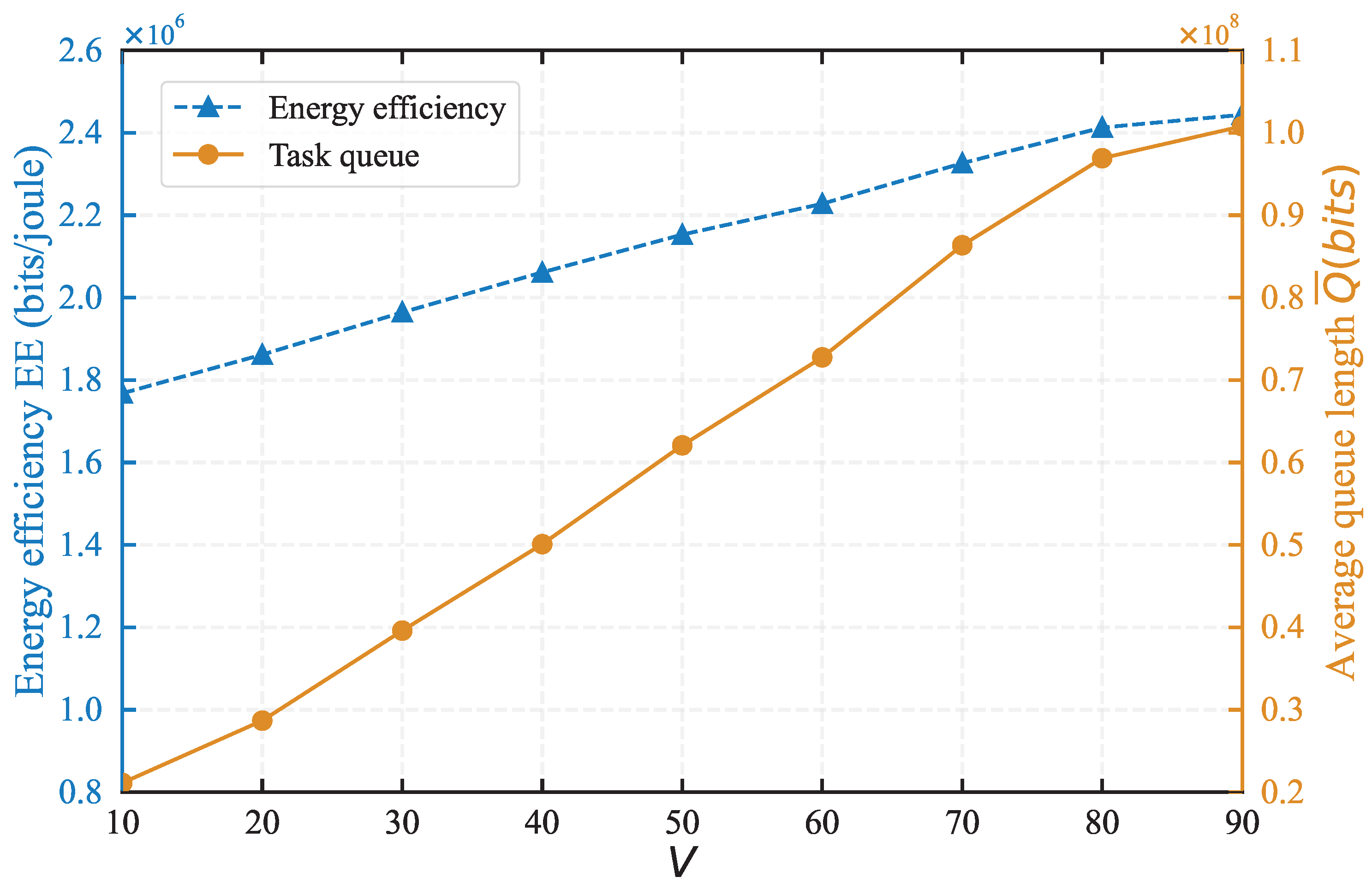

Figure 7 illustrates the impact of the control parameter

V on EE and the average stable queue length, with parameter settings of

,

, a distance of 120 meters between nodes

and

, and a task arrival rate at

of

. As

V increases, EE is enhanced, and the stable queue threshold also increases. This indicates that with the increase of

V, EE becomes the primary concern, while the current queue length plays a relatively minor role in the objective function. However, when

V reaches a certain threshold, the gain in energy efficiency becomes saturated, and further increasing

V will no longer have a significant impact on system performance and queue length. This trend can be interpreted as follows: a larger

V allows the system to buffer more data, which is consistent with the previous theoretical analysis. Thus, the problem is transformed into seeking to maximize EE while to some extent disregarding the current queue length.

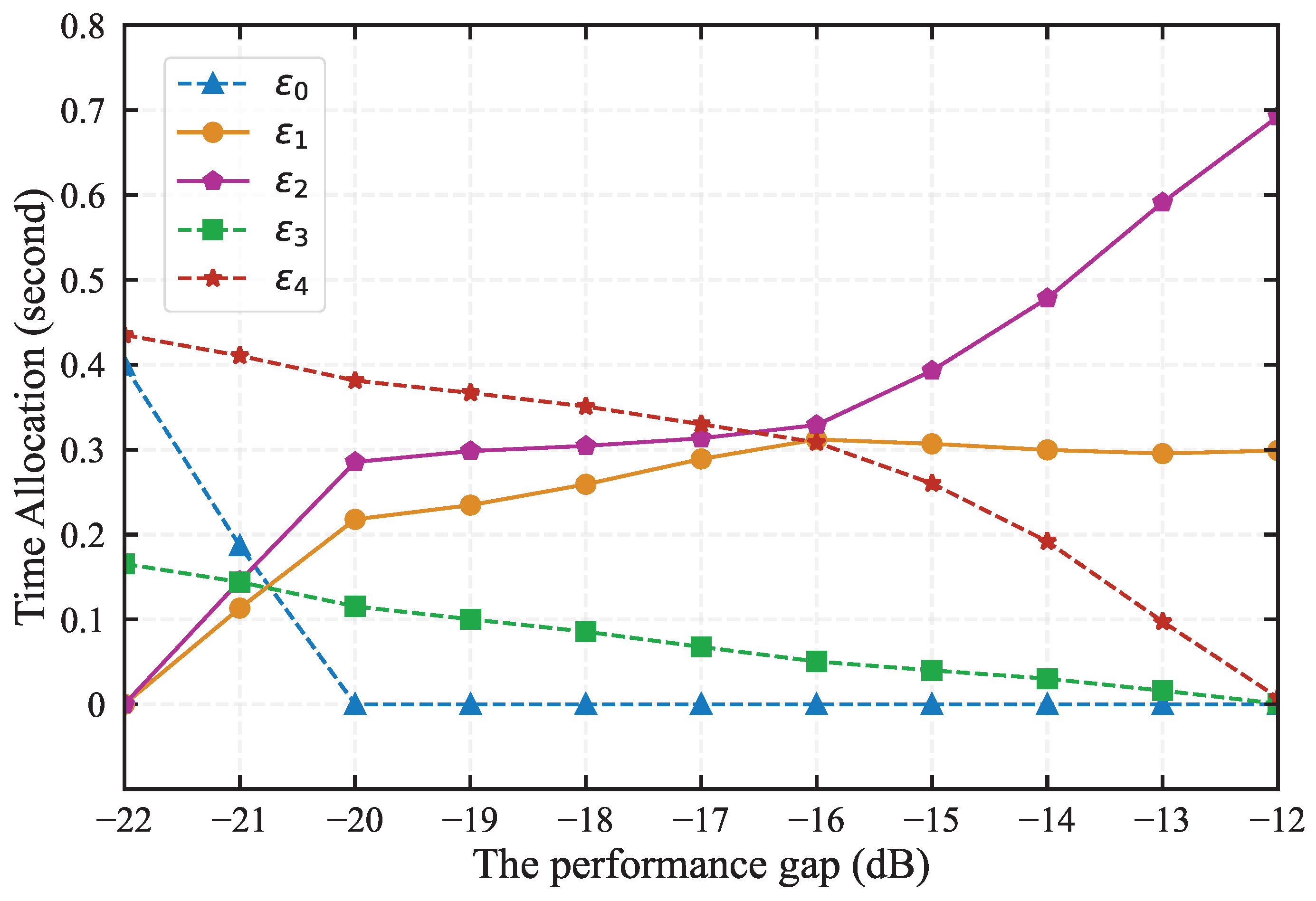

Figure 8 illustrates the optimal time allocation of

versus the performance gap

. Initially, when

is low, despite the lower energy consumption of the BackCom mode, achieving a larger number of computational bits at the same energy consumption is challenging. Consequently, MDs prefer the AC mode and allocate more time

for energy collection to meet data processing needs. As

increases,

gradually decreases, and when

exceeds -20 dB,

. This is because, as

increases, the BackCom mode can not only achieve more computational bits at the same energy consumption but also collect sufficient energy to support the circuit consumption under the AC mode, significantly improving energy efficiency. Therefore, as

increases, users are more inclined to choose the BackCom mode, using its reflective event signal function to perform task transmission and energy collection to meet the circuit consumption [

38]. This scheme ensures that under different

conditions, the system can operate at the highest efficiency, optimizing energy usage.

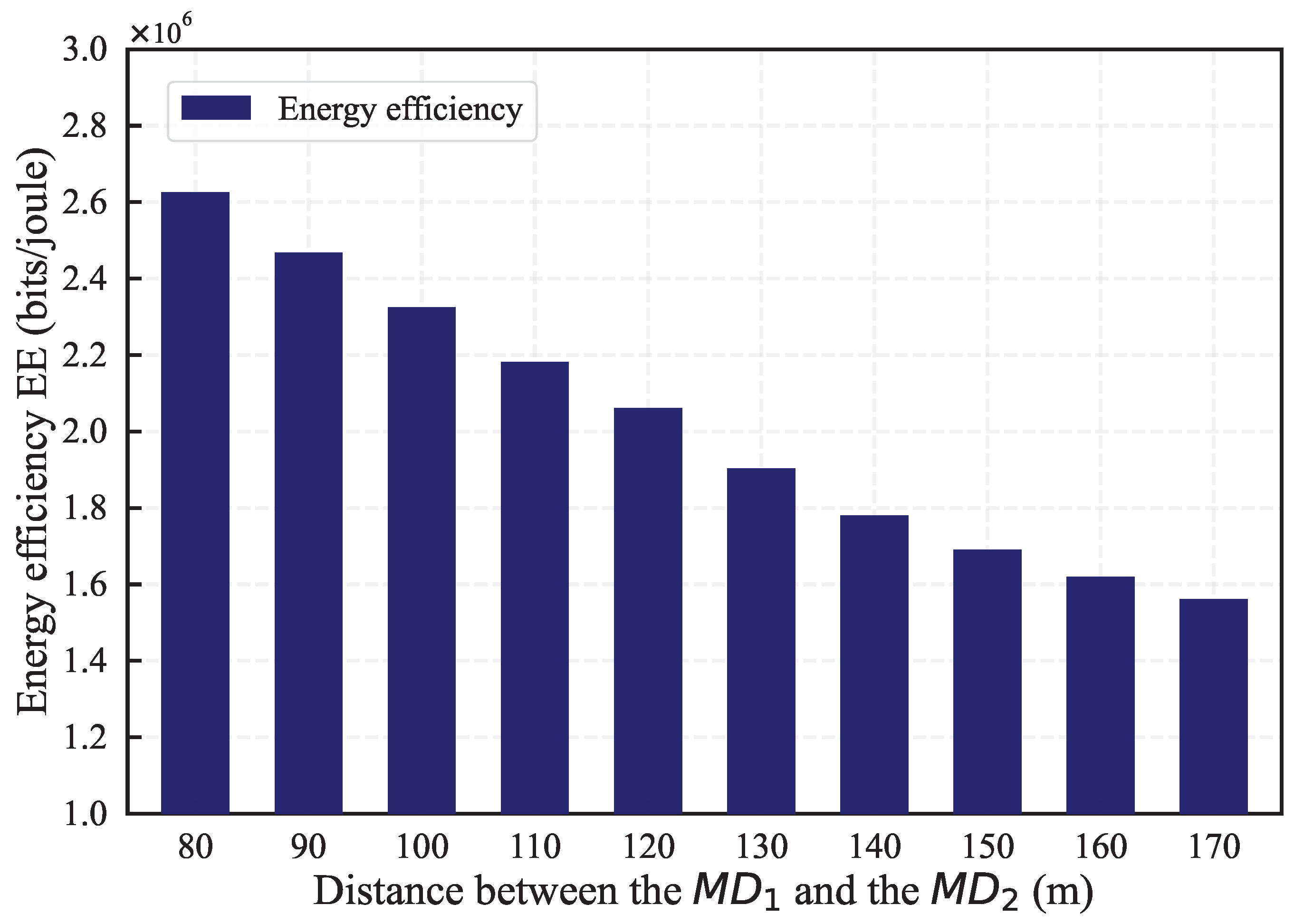

Figure 9 illustrates that the EE under varying distances between

and

, with

. The distance between the remote MD and the helper device ranges from 80 to 180 meters. It is observed that EE decreases as the distance increases. This is because an increase in distance leads to a reduction in channel gain, necessitating more time and higher power to transmit data to maintain a shorter data queue, thereby increasing energy consumption. This indicates that in practical deployment, the distance between edge node devices and helper devices should be kept within a reasonable range to avoid a rapid decline in network performance. This assessment not only quantifies the specific impact of distance on energy efficiency but also emphasizes the importance of considering the distance factor in the design of efficient networks.

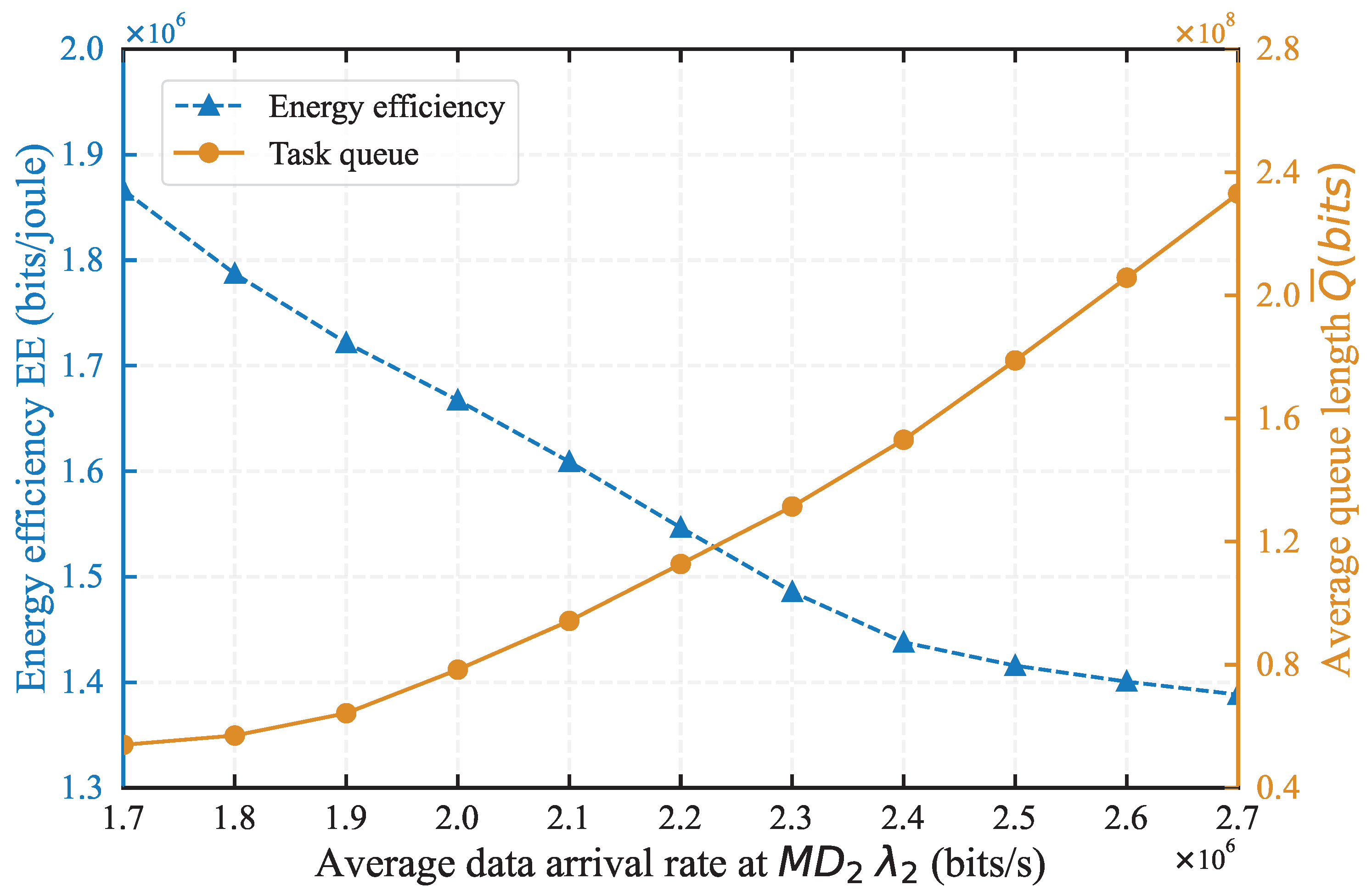

In

Figure 10, we evaluate the EE and the average task queue length as the task arrival rate at

varies. The distance between

and

is set to 120 meters, and control parameter

V is set to 40. As the computation task data arrival rate at

increases, the EE decreases. The rise in data rate causes the local data queue to expand, necessitating a higher data transmission rate from the system. his not only entails processing a larger volume of data but also results in greater energy expenditure to maintain shorter data queues, thereby increasing overall energy consumption. Despite this trade-off in energy efficiency, our algorithm optimizes energy usage, ensuring that the system maintains efficient data processing and rapid response capabilities even as data rates increase.

where represents the performance gap reflecting real modulation [13], is the noise power. The corresponding energy consumption by circuit is

where represents the performance gap reflecting real modulation [13], is the noise power. The corresponding energy consumption by circuit is

where is the reflection coefficient of the BackCom at . represents the channel gain from the HAP to the at time slot t, and denotes the channel gain from the to the HAP at time slot t. The corresponding energy consumption is

where is the reflection coefficient of the BackCom at . represents the channel gain from the HAP to the at time slot t, and denotes the channel gain from the to the HAP at time slot t. The corresponding energy consumption is

where represents the transmit power allocated to AC at [10], is the noise power and represents the channel gain from and . The corresponding AC offloading energy consumption is

where represents the transmit power allocated to AC at [10], is the noise power and represents the channel gain from and . The corresponding AC offloading energy consumption is

where denotes the transmit power of the through AC. Let denotes the circuit power of through AC. The energy consumed for task offloading AC at in slot t is

where denotes the transmit power of the through AC. Let denotes the circuit power of through AC. The energy consumed for task offloading AC at in slot t is