Submitted:

20 August 2024

Posted:

21 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Crossing Blocks

2.3. Botanical Seeds and Seedlings

2.4. Characters Investigated

2.5. Morphometric Variables

2.6. Statistical Analysis and Visualization

3. Results

3.1. Pollinations

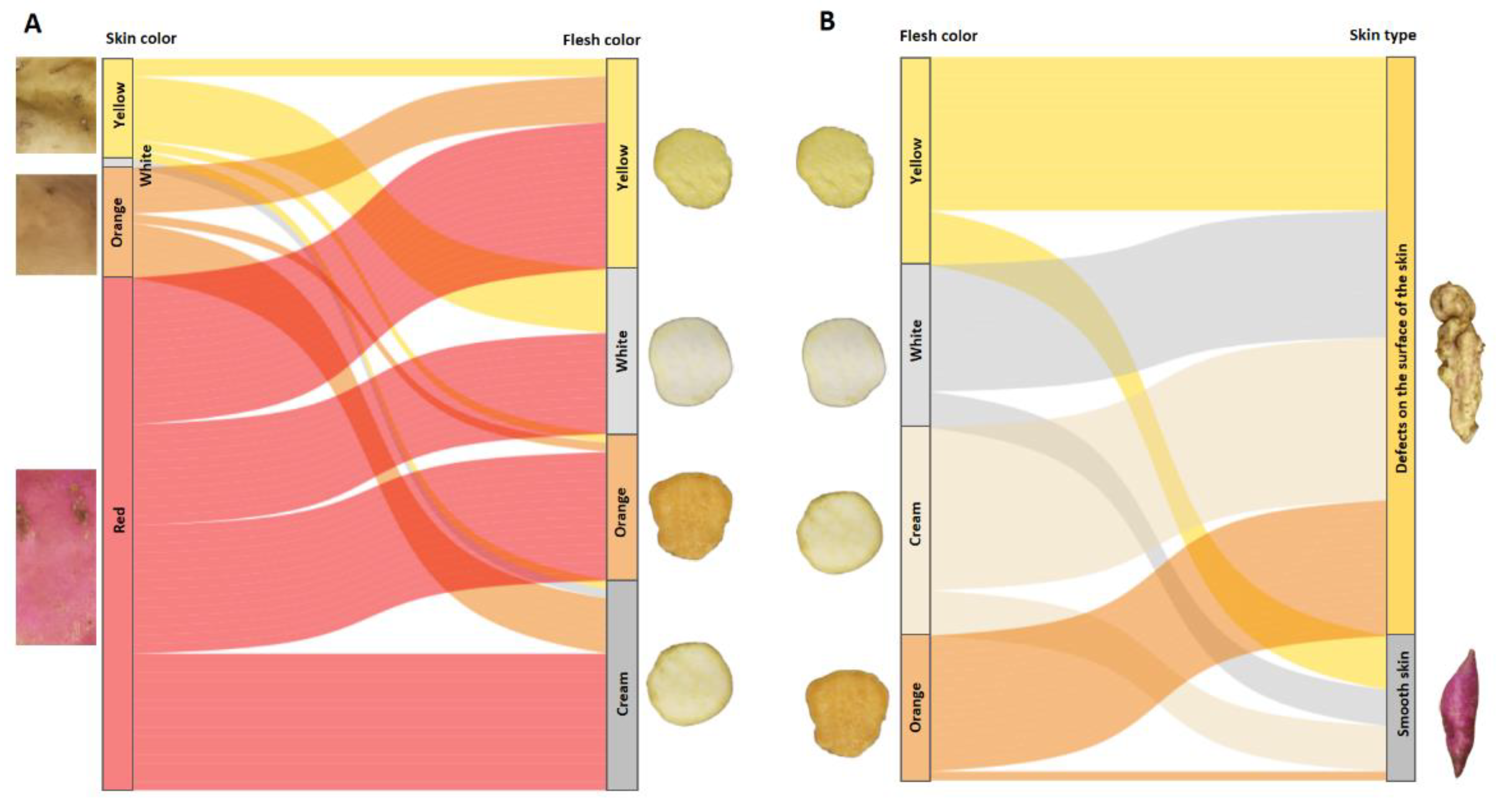

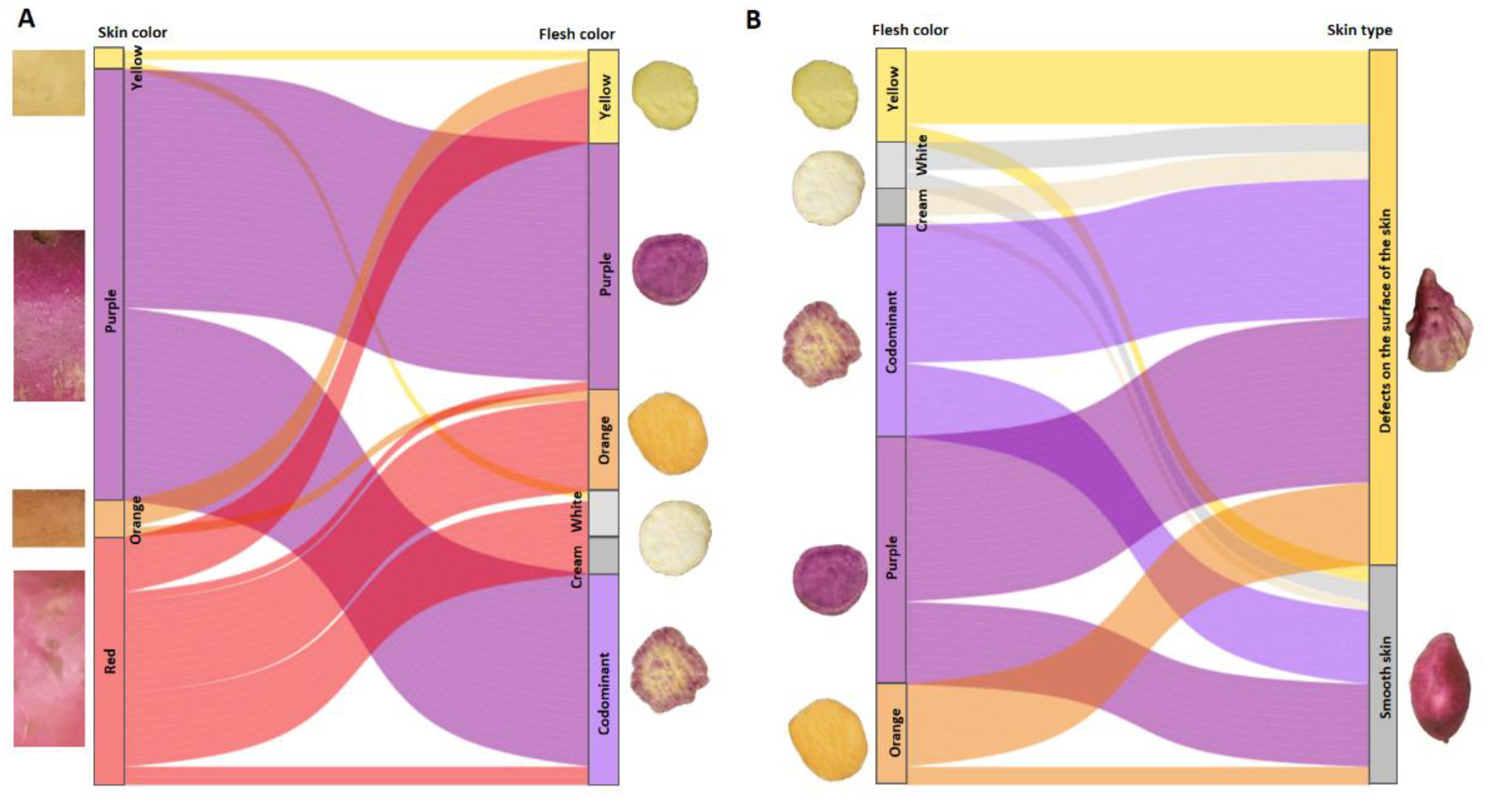

3.2. Flesh Color of Tuberous Roots

3.3. Shape of Tuberous Roots

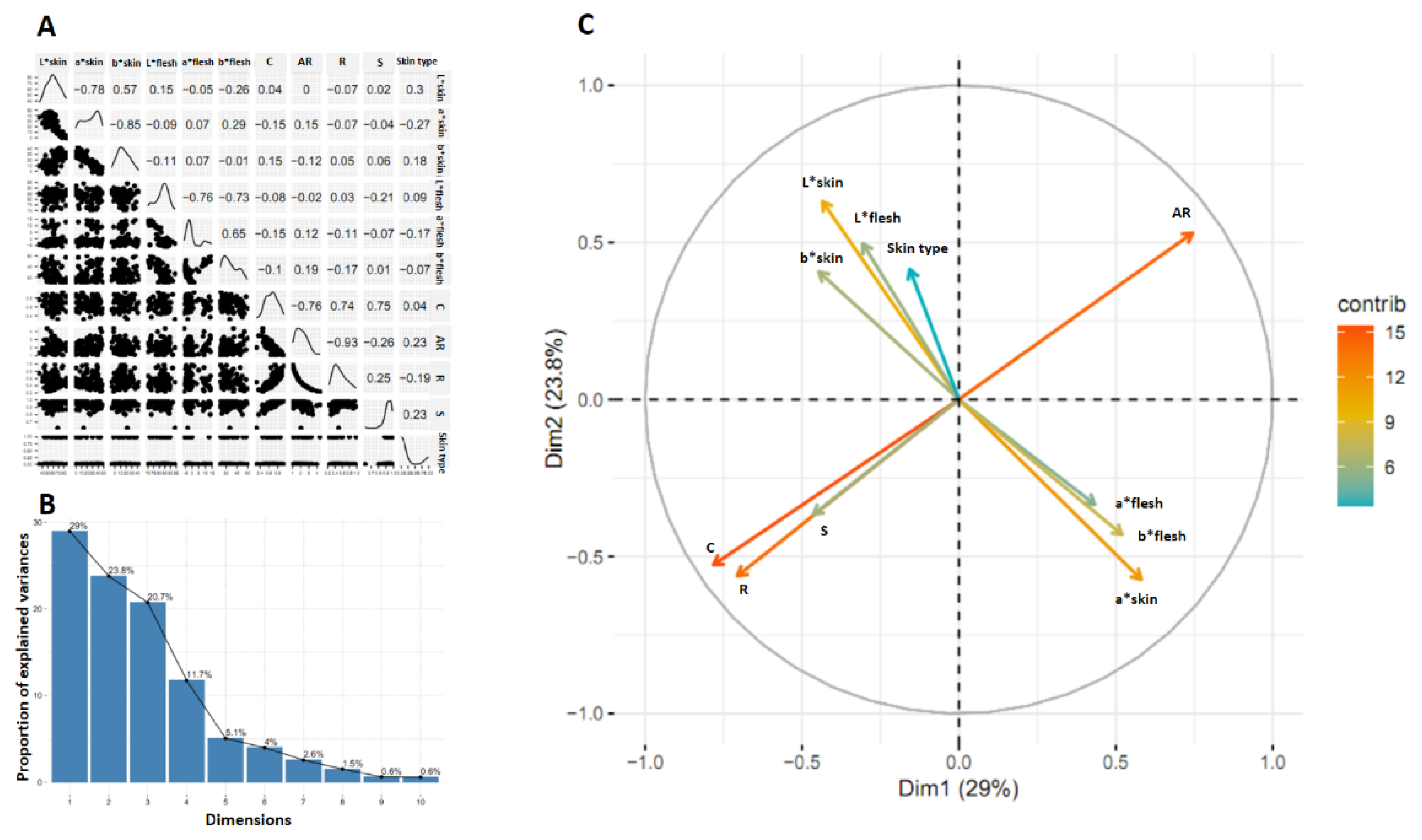

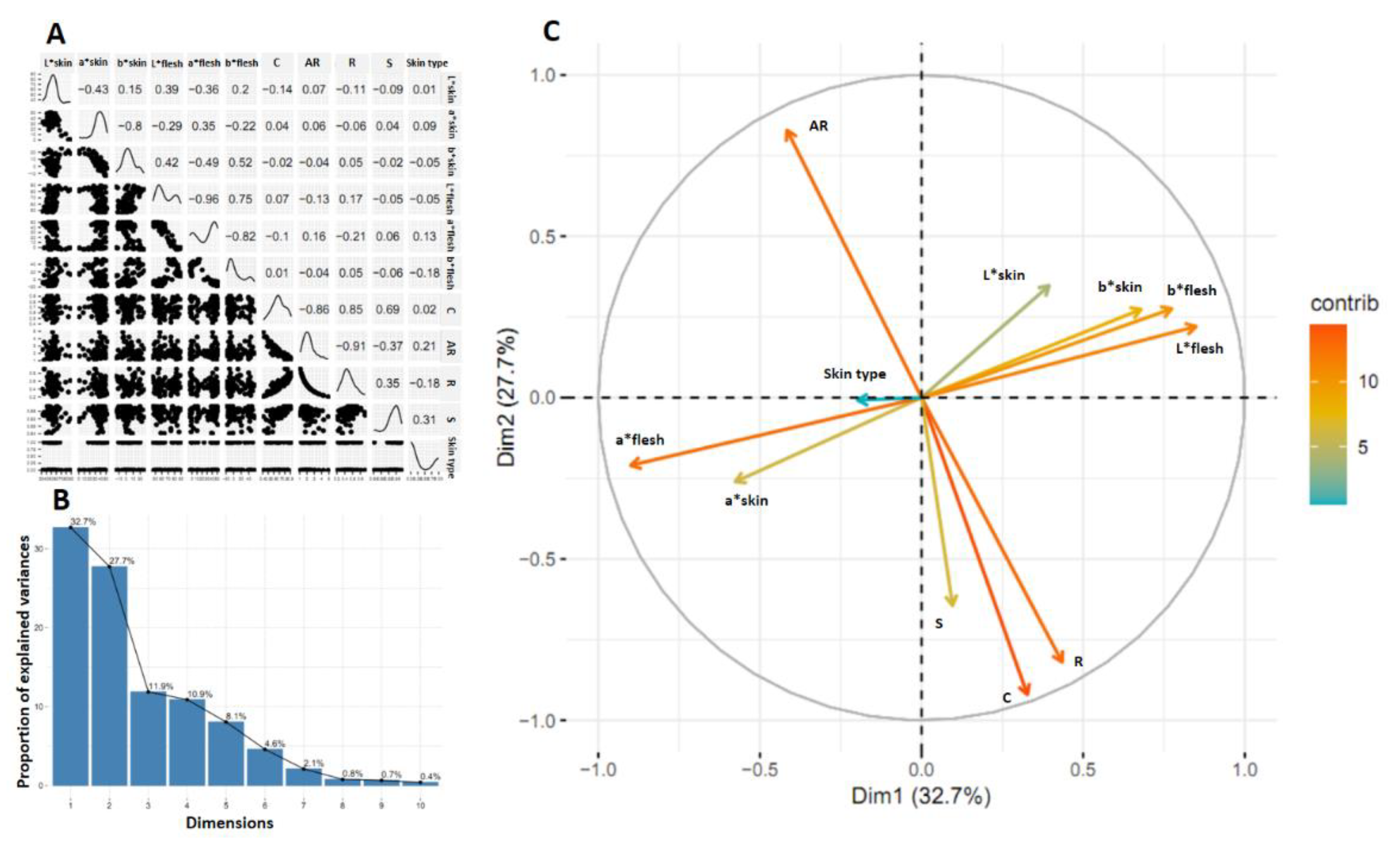

3.4. Association between Traits

4. Discussion

4.1. Pollinations

4.2. Flesh Color of Tuberous Roots

4.3. Tuberous Root Shape

4.3. Association between Characters

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- BBC News Mundo. Gregor Mendel: cómo un monje con un jardín de arvejas descubrió las leyes de la herencia genética. 2021. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-56719582 (accessed on 18/08/2024).

- Sadurní, J. M. EL MONJE BOTÁNICO. Gregor Mendel, el padre de la genética. 2023. Available online: https://historia.nationalgeographic.com.es/a/gregor-mendel-padre-genetica_15509 (accessed on 12/08/2024).

- Isobe, S.; Shirasawa, K.; Hirakawa, H. Current status in whole genome sequencing and analysis of Ipomoea spp. Plant Cell Report 2019, 38, 1365-1371.

- Kriegner, A.; Cervantes, J.C.; Burg, K.; Mwanga, O.M.; Zhang, D. A genetic linkage map of sweetpotato [Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.] based on AFLP markers. Mol Breeding 2003, 11, 169-185.

- Mollinari, M.; Olukolu, B.A.; Pereira, D.S.; Khan, A.; Gemenet, D.; Yencho, G.C.; Zeng, Z.B. Unraveling the Hexaploid Sweetpotato Inheritance Using Ultra-Dense Multilocus Mapping. G3 (Bethesda) 2020, 10,281-292.

- Cervantes, J.C.; Yencho, G.C.; Kriegner, A.; Pecota, K.V.; Faulk, M.A.; Mwanga, R.O.; Sosinski, B.R. Development of a genetic linkage map and identification of homologous linkage groups in sweetpotato using multiple-dose AFLP markers. Mol Breeding 2008, 21, 511–532.

- Jones, A. Theoretical Segregation Ratios of Qualitatively Inherited Characters for Hexaploid Sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas L.). Agricultural Research Service US, Technical Bulletin 1967, 1368.

- Shiotani, I. Sweet potato evolution. Sweet potato research and development for small farmers. Laguna, The Philippines. 1989, 5-15.

- Grüneberg, W.J.; Ma, D.; Mwanga, R.; Carey, E.; Huamani, K.; Diaz, F. et al. Advances in sweet potato breeding from 1992 to 2012. Potato and Sweetpotato in Africa: Transforming the Value Chains for Food and Nutrition Security. Chapter: 1, CAB International, 2015, 68.

- Rangaswami, A.K.; Sampathkumar, R. Inheritance of leaf shape and colour in sweet potato. Indian Journal of Genetics and Plant Breeding 1978, 38, 262-263.

- Vimala, B.; Sreekanth, A.; Hariprakash, B.; Wolfgang, G. Variation in morphological characters and storage root yield among exotic orange-fleshed sweet potato clones and their seedling population. Journal of Root Crops 2012, 38, 32-37.

- Hernandez, T.P. A Study of Some Genetic Characters of the Sweet Potato. PhD, LSU Thesis. 1942, 66.

- Harmon, S.A. Genetic Studies and Compatibilities in the Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas). PhD, LSU Theses. 1960, 595.

- Poole, C.F. Sweet potato genetic studies. University of Hawaii, Hawaii, Technical bulletin, 1955, 27.

- Arizio, C.M.; Manifesto, M.M.; Martí, H.R. Análisis de caracteres relacionados con el color de la raíz engrosada en un cruzamiento de dos clones de Ipomoea batatas L. (Lam.). Horticultura Argentina 2009, 28:5-13.

- Wang, A.; Li, R.; Ren, L.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Ma, D.; Luo, Y. A comparative metabolomics study of flavonoids in sweet potato with different flesh colors (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam). Food Chemical 2018, 260, 124–134.

- Xiao, Y.; Zhu, M.; Gao, S. Genetic and Genomic Research on Sweet Potato for Sustainable Food and Nutritional Security. Genes 2022, 13, 1833.

- De Albuquerque, M.R.; Sampaio, K.B.; Souza, E.L. Sweet potato roots: Unrevealing an old food as a source of health promoting bioactive compounds. A review. Trends Food Science Technology 2019, 85, 277–286.

- Sagar, N.A.; Pareek, S.; Sharma, S.; Yahia, E.M.; Lobo, M.G. Fruit and Vegetable Waste: Bioactive Compounds, Their Extraction, and Possible Utilization. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2018, 17, 512–531.

- Minatel, I.O.; Borges, C.V.; Alonzo, H.; Hector, G.; Gomez, C.O.; Pace, G.; Lima, P. Phenolic Compounds: Functional Properties, Impact of Processing and Bioavailability, Phenolic Compounds - Biological Activity. London, United Kingdom, 2017, 1–24.

- Hernandez, T.P.; Hernandez, T.; Constantin, R.J.; Kakar, R.S. Improved techniques in breeding and inheritance of some of the characters In the sweet potato, Ipomoea batatas L. Proc. Int. Symp. on Tropical Root Crops, 1967, 1, 31-49.

- Morales, R.A.; Rodríguez, S.D.; Xie, Y.; Guo, X.; Jia, X.; Ma, P.; Bian, X. Self-incompatibility of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.). A review. Revista Agricultura Tropical 2019, 5, 1-8.

- Arizio, C.M. Marcadores funcionales relacionados con la síntesis de pigmentos y su localización en un mapa de ligamiento en Ipomoea batatas L. Lam. Tesis Doctoral. Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2011, 267.

- Schroeder, T. Okinawa Sweet Potato: Japan’s Amazing Purple Superfood! 2021. Available online: https://sakura.co/blog/okinawa-sweet-potato-japans-amazing-purple-superfood (accessed on 11/05/2024).

- Morales, R.A.; Rodríguez, S.D.; Rodríguez, M.S.; Rodríguez, G.Y.; Trujillo, O.N.; Jiménez, M.A.; Molina, C.O. Floral biology and phenology of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas [L.] Lam.) in Cuba: Bases for genetic improvement. African Journal of Agricultural Research 2023, 19, 1043-1055.

- Hernández, A.; Pérez, J.; Bosch, D.; Castro, N. Clasificación de los suelos de Cuba. Ediciones INCA, Cuba. 2015, 61.

- Ferreira, T.; Rasband, W. ImageJ User Guide. IJ 1.46 Revised edition. 2012, 198.

- X-Rite. Guía para Entender la Comunicación del Color. L10-001-SL, 2002, 2, 24.

- Popat, R.; Patel, R.; Parmar, D. Variability: Genetic Variability Analysis for Plant Breeding Research. R package version 0.1.0, 2020, 7.

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer, Berlin, Germany, 2016, 260.

- Harrower, M.; Brewer, C.A. ColorBrewer.org: An Online Tool for Selecting Colour Schemes for Maps. The Cartographic Journal 2003, 40, 27-37.

- Garnier, S. viridis: Default Color Maps from ‘matplotlib’. R package Version 0.4.0. 2017. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=viridis. (accessed on 2/08/2024).

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate data analysis. MacMillan Publ. Co., Nueva York, United States, 1992, 544.

- Pla, L.E. Análisis multivariado: Método de componentes principales. Secretaría General de la Organización de los Estados Americanos (OEA). Washington, D.C., United States, 1986, 95.

- Reynoso, D.; Huaman, Z.; Aguilar, C. Methods to determine the fertility and compatibility of sweetpotato. Training Manual. International Potato Center, Lima, Peru, 1998, 133-140.

- Kambale, H.; Ngugi, K.; Olubayo, F.; Kivuva, B.; Muthomi, J.; Nzuve, F. The Inheritance of Yield Components and Beta Carotene Content in Sweet Potato. Journal of Agricultural Science 2018, 10, 2.

- Lestari, S.U.; Hapsari, R.I.; Basuki, N. Crossing Among Sixteen Sweet Potato Parents for Establishing Base Populations Breeding. AGRIVITA Journal of Agricultural Science 2019, 41, 246-255.

- Rukarwa, R.J.; Mukasa, S.B.; Sefasi, A.; Ssemakula, G.; Mwanga, O.M.; Ghislain, M. Segregation analysis of cry7Aa1 gene in F1 progenies of transgenic and non-transgenic sweetpotato crosses. Journal of Plant Breeding and Crop Science 2013, 5, 209-213.

- Constantin, R.J. A Study of the Inheritance of Several Characters in the Sweet Potato, (Ipomoea batatas). PhD, LSU Theses. 1964, 93.

- Miller, R.M.; Melampy, J.J.; Hernandez, T.P. Effect of storage on the carotene content of fourteen varieties of sweet potatoes. Proceedings of the American Society for Horticultural Science 1949, 54, 399-402.

- Hernandez, T.P. A study of the inheritance of skin color, total carotenoid pigments, dry matter, and techniques in classifying these characters in Ipomoea batatas. PhD, La. State University Thesis. 1963, 67.

- Edmond, J.B. Genetics, breeding behaviour, and development of superior varieties. Sweet Potatoes: Production, Processing, Marketing. AVI Publishing Co., Inc., Westport, Connecticut, United States, 1971, 58-80.

- Hammett, H.L. A Study of the Inheritance of Root Shape, Skin Color, Total Carotenoid Pigments, Dry Matter, Fiber and Baking Quality in the Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas). PhD, LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses, 1965, 140.

- Thibodeaux, S.D.; Hernandez, T.P.; Hernandez, T. Breeding techniques, combining aility of parents, heritabilities, insect resistance and other factors affecting sweet potato breeding. Third International Symposium on Tropical Root Crops, IITA, Tfbadan, 1973, 12, 2-9.

- Stokdyk, E.A. Selection of sweet potatoes. Journal of Heredity 1925, 16147–150.

- Franklin, M.; Jones, A. Plant Breeding Reviews. AVI Publishing Co, 1986, 4, 313-345.

| Character to be investigated | Parents | Parents | Family | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color of the flesh of the tuberous root | INIVIT BM-90 (purple flesh) |

x | CEMSA 74-228 (white flesh) |

ISS-2305 |

| INIVIT BM-90 (purple flesh) |

x | INIVIT BM-8 (purple flesh) |

ISS-2306 | |

| INIVIT BS-16 (orange flesh) |

x | Español (orange flesh) |

ISS-2307 | |

| INIVIT BS-16 (orange flesh) |

x | CEMSA 78-326 (white flesh) |

ISS-2308 | |

| INIVIT BM-25-19 (purple flesh) | x | INIVIT BS-16 (orange flesh) |

ISS-2309 | |

| Shape of tuberous roots | INIVIT BS-16 (Skin with horizontal constrictions and longitudinal grooves) |

x | CEMSA 74-228 (Skin with longitudinal grooves) |

ISS-2310 |

| INIVIT BM-90 (smooth skin) |

x | ISS-18-004 (smooth skin) |

ISS-2311 |

| Variables | Code | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| Circularity | C | |

| Aspect ratio | AR | |

| Redondez | R | |

| Solidez | S | |

| Luminosity | L* | - |

| a* coordinate | a* | - |

| b* coordinate | b* | - |

| Family | No. of pollinations | No. of capsules | % of positive pollinations | No. of sedes | No. of seeds/capsule | % of seed germination | No. seedlings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISS-2305 | 416 | 273 | 65.7 | 320 | 1.17 | 77.5 | 248 |

| ISS-2306 | 191 | 138 | 72.47 | 221 | 1.60 | 89.4 | 198 |

| ISS-2307 | 497 | 226 | 45.53 | 279 | 1.23 | 79.2 | 221 |

| ISS-2308 | 273 | 189 | 69.35 | 269 | 1.42 | 93.2 | 251 |

| ISS-2309 | 343 | 155 | 45.06 | 306 | 1.98 | 87.6 | 268 |

| ISS-2310 | 419 | 199 | 47.48 | 366 | 1.84 | 90.8 | 332 |

| ISS-2311 | 280 | 181 | 64.43 | 284 | 1.57 | 86.7 | 246 |

| Promedio | - | - | 58.57 | - | 1.54 | 86.34 | - |

| Total | 2419 | 1361 | - | 2045 | - | - | 1764 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).