Submitted:

21 August 2024

Posted:

22 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Epidemiology

Etiology and Pathophysiology (Phenotypic and Endotypic Variants of Polyposis)

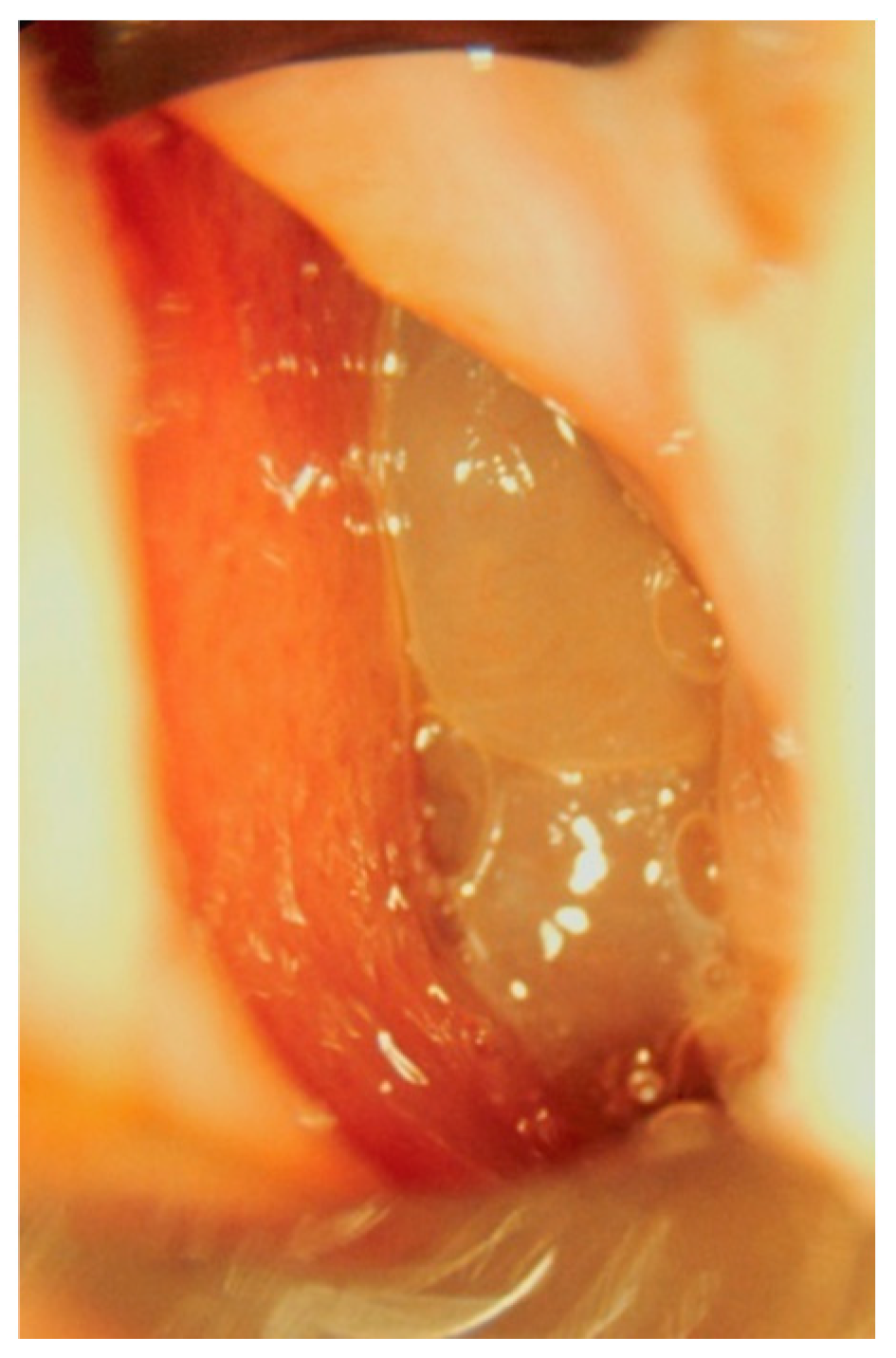

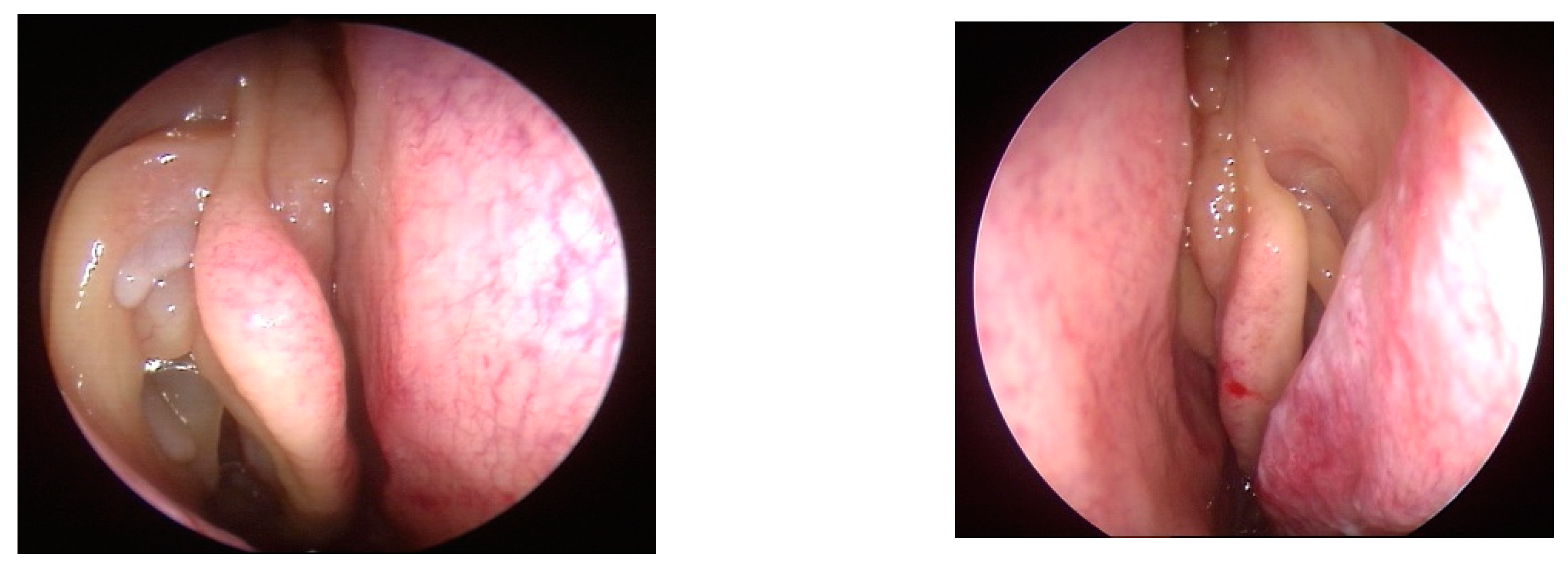

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnostic Methods

| 0= no polyps |

| 1= polyps confined to the middle meatus |

| 2=multiple polyps occupying the middle meatus |

| 3=polyps extending beyond the middle meatus |

| 4=polyps completely obstructing the nasal cavity |

| 0=no polyps |

| 1=small polyps in the middle meatus not reaching the inferior border of the middle meatus |

| 2=nasal polyps reaching bellow the lower border of the middle meatus |

| 3=large polyps reaching the lower border of the inferior turbinate or polyps medial to the middle turbinate |

| 4=large nasal polyps causing complete obstruction of the inferior nasal cavity |

- No abnormality = 0 points

- Partial opacification = 1 point

- Complete opacification = 2 points

- For the ostiomeatal complex, the score is different:

- No opacification = 0 points

- Opacification = 2 points

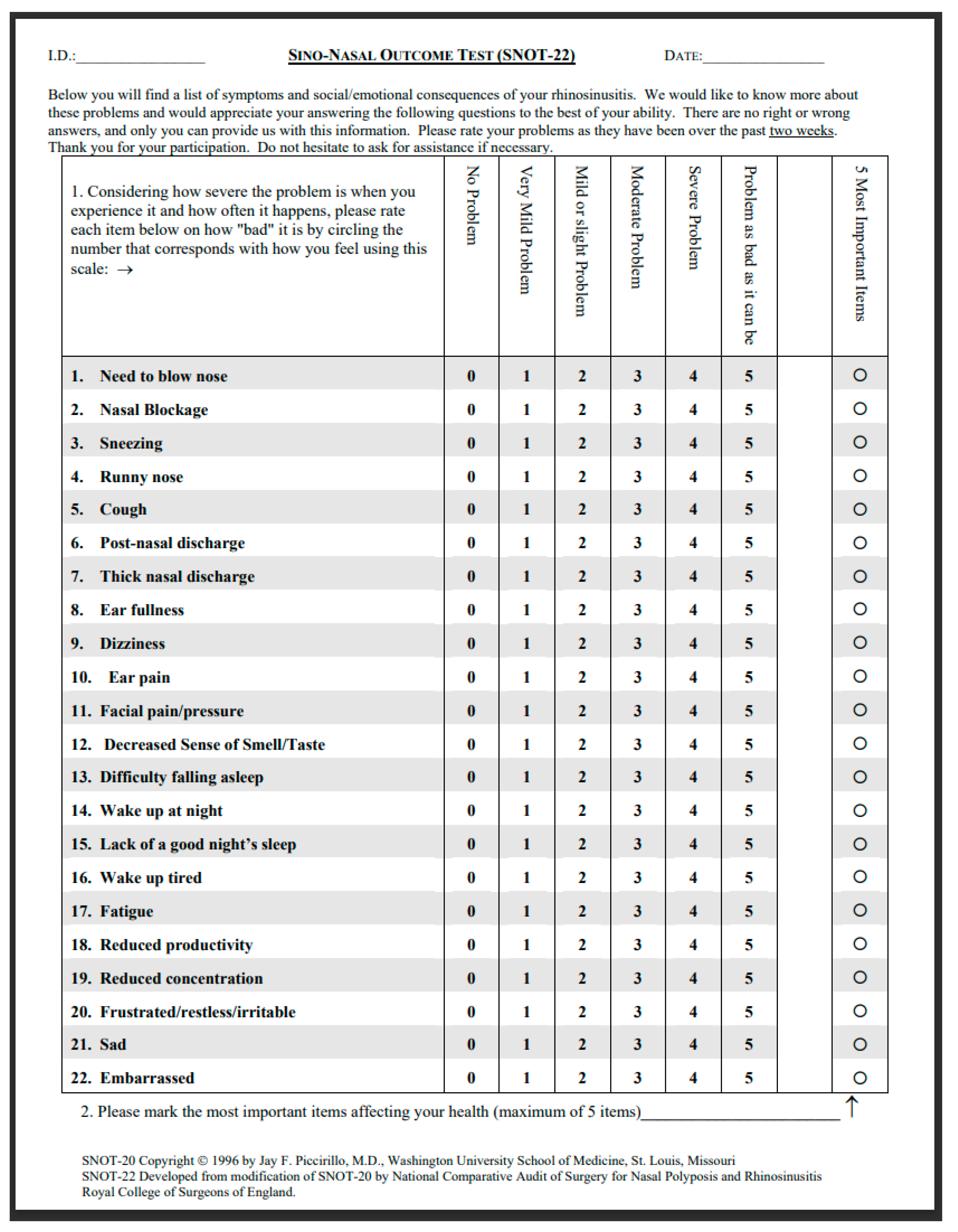

Impact on the Quality of Life

Management and Treatment Approaches

Biological Treatment and Ongoing Care

- Symptomatic uncontrolled nasal polyposis unresponsive to traditional medical treatment (medical therapy +/- surgery) with these additional criteria:

- Evidence of type 2 inflammation (tissue eos>10/hpf, or blood eos>250, or total IgE>100)

- Need for systemic corticosteroids or contraindication for systemic corticosteroids (>2 courses per year, or long term . 3 months low dose steroids)

- Significantly impaired quality of life (SNOT22>40)

- Significant loss of smell (anosmic on smell test)

- Diagnosis of comorbid asthma (asthma needing regular inhaled corticosteroids)

- Reduced nasal polyp size

- Reduced need for systemic oral corticosteroids

- Improved quality of life

- Improved sense of smell

- Reduced impact of comorbidities

Conclusion

References

- W. J. Fokkens et al., “EPOS 2012: European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2012. A summary for otorhinolaryngologists,” Rhinology journal, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 1–12, Mar. 2012. [CrossRef]

- W. J. Fokkens et al., “European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2020,” Rhinology journal, vol. 0, no. 0, pp. 1–464, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Hastan et al., “Chronic rhinosinusitis in Europe - an underestimated disease. A GA2LEN study,” Allergy, vol. 66, no. 9, pp. 1216–1223, Sep. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Khan A, Vandeplas G, Huynh TMT, Joish VN, Mannent L, Tomassen P, Van Zele T, Cardell LO, Arebro J, Olze H, Foerster-Ruhrmann U, Kowalski ML, Olszewska-Ziaber A, Holtappels G, De Ruyck N, van Drunen C, Mullol J, Hellings PW, Hox V, Toskala E, Scadding G, Lund VJ, Fokkens WJ, Bachert C. The Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GALEN rhinosinusitis cohort: a large European cross-sectional study of chronic rhinosinusitis patients with and without nasal polyps. Rhinology. 2019 Feb 1;57(1):32-421;57(1):32-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S., Zhou, A., Emmanuel, B., Thomas, K., & Guiang, H. (2020). Systematic literature review of the epidemiology and clinical burden of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 36(11), 1897–1911. [CrossRef]

- E. Esen, A. Selçuk, and D. Passali, “Epidemiology of Nasal Polyposis,” in All Around the Nose, Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020, pp. 367–371. [CrossRef]

- A. G. Hirsch et al., “Nasal and sinus symptoms and chronic rhinosinusitis in a population-based sample,” Allergy, vol. 72, no. 2, pp. 274–281, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Palmer JN, Messina JC, Biletch R, et al. A cross-sectional, population-based survey of U.S. adults with symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy Asthma Proc 2019; 40: 48-56. [CrossRef]

- Klossek JM, Neukirch F, Pribil C, Jankowski R, Serrano E, Chanal I, El Hasnaoui A. Prevalence of nasal polyposis in France: a cross-sectional, case-control study. Allergy. 2005;60:233–7. [CrossRef]

- Johansson L, Akerlund A, Holmberg K, et al. Prevalence of nasal polyps in adults: the Skovde population-based study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2003; 112: 625-9. [CrossRef]

- Shi JB, Fu QL, Zhang H, et al. Epidemiology of chronic rhi- nosinusitis: results from a cross-sectional survey in seven Chinese cities. Allergy 2015; 70: 533-9. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Kim, C. Cho, E. J. Lee, Y. S. Suh, B. I. Choi, and K. S. Kim, “Prevalence and risk factors of chronic rhinosinusitis in South Korea according to diagnostic criteria,” Rhinology journal, vol. 54, no. 4, pp. 329–335, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Min YG, Jung HW, Kim HS, Park SK, Yoo KY. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic sinusitis in Korea: results of a nationwide survey. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1996;253:435–9. [CrossRef]

- Raciborski, Filip, Magdalena Arcimowicz, Bolesław Krzysztof Samoliński, Wojciech Pinkas, Piotr Samel-Kowalik and Andrzej Śliwczyński. “Recorded prevalence of nasal polyps increases with age.” Advances in Dermatology and Allergology/Postȩpy Dermatologii i Alergologii 38 (2020): 682 - 688. [CrossRef]

- M. A. DeMarcantonio and J. K. Han, “Nasal Polyps: Pathogenesis and Treatment Implications,” Otolaryngol Clin North Am, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 685–695, Jun. 2011. [CrossRef]

- D. R. Littman and E. G. Pamer, “Role of the Commensal Microbiota in Normal and Pathogenic Host Immune Responses,” Cell Host Microbe, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 311–323, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins: a key in airway disease?C. Bachert, P. Gevaert, P. Van CauwenbergeAllergy1..2002VOL57, Issue 6: 480-487 7 May 2002. [CrossRef]

- van der Lans R, Otten JJ, Adriaensen GFJPM, Benoist LBL, Cornet ME, Hoven DR, Rinia AB, Fokkens WJ, Reitsma S. Eosinophils are the dominant type2 marker for the current indication of biological treatment in severe uncontrolled chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Rhinology. 2024 Jun 1;62(3):383-384. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EUFOREA/EPOS2020 statement on the clinical considerations for chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps care.Hellings PW, Alobid I, Anselmo-Lima WT, Bernal-Sprekelsen M, Bjermer L, Caulley L, Chaker A, Constantinidis J, Conti DM, De Corso E, Desrosiers M, Diamant Z, Gevaert P, Han JK, Heffler E, Hopkins C, Landis BN, Lourenco O, Lund V, Luong AU, Mullol J, Peters A, Philpott C, Reitsma S, Ryan D, Scadding G, Senior B, Tomazic PV, Toskala E, Van Zele T, Viskens AS, Wagenmann M, Fokkens WJ.Allergy. 2024 May;79(5):1123-1133. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- T. Van Zele et al., “Differentiation of chronic sinus diseases by measurement of inflammatory mediators,” Allergy, vol. 61, no. 11, pp. 1280–1289, Nov. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Benninger MS, “Rhinitis, sinusitis and their relationships to allergies,” American Journal of 7hinology , vol. 6, pp. 37–43, 1992. [CrossRef]

- Wilson KF, McMains KC, Orlandi RR. The association between allergy and chronic rhinosinusitis with and without nasal polyps: an evidence-based review with recommendations. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014 Feb;4(2):93-103. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caplin I, Haynes GT, and Sphan J, “Are nasal polyps an allergic phenomenon?,” Ann Alergy, vol. 29 dec, no. 12, pp. 631–634, 1971.

- M. Gelardi, L. Iannuzzi, S. Tafuri, G. Passalacqua, and N. Quaranta, “Allergic and non-allergic rhinitis: relationship with nasal polyposis, asthma and family history.,” Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 36–41, Feb. 2014.

- S. Marcus, L. T. Roland, J. M. DelGaudio, and S. K. Wise, “The relationship between allergy and chronic rhinosinusitis,” Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 13–17, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Pang, O. Eskici, and J. A. Wilson, “Nasal polyposis: Role of subclinical delayed food hypersensitivity,” Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, vol. 122, no. 2, pp. 298–301, Feb. 2000. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Collins, S. Loughran, P. Davidson, and J. A. Wilson, “Nasal polyposis: Prevalence of positive food and inhalant skin tests,” Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, vol. 135, no. 5, pp. 680–683, Nov. 2006. [CrossRef]

- J. Bousquet et al., “Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA): Achievements in 10 years and future needs,” Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, vol. 130, no. 5, pp. 1049–1062, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. P. Berges-Gimeno, R. A. Simon, and D. D. Stevenson, “The natural history and clinical characteristics of aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease,” Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, vol. 89, no. 5, pp. 474–478, Nov. 2002. [CrossRef]

- J. E. Chang, W. Chin, and R. Simon, “Aspirin-Sensitive Asthma and Upper Airway Diseases,” Am J Rhinol Allergy, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 27–30, Jan. 2012. [CrossRef]

- C. Rumeau, D. T. Nguyen, and R. Jankowski, “How to assess olfactory performance with the Sniffin’ Sticks test ®,” Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis, vol. 133, no. 3, pp. 203–206, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. L. Doty, R. E. Frye, and U. Agrawal, “Internal consistency reliability of the fractionated and whole University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test,” Percept Psychophys, vol. 45, no. 5, pp. 381–384, Sep. 1989. [CrossRef]

- Ref Recommandation de pratique Clinique pour la polypose nasosinusienne. Reco-PNS-FINAL-290923-.pdf (sforl.org).

- D. P. Migueis et al., “Obstructive sleep apnea in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps: a cross-sectional study,” Sleep Med, vol. 64, pp. 43–47, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Serrano E, Neukirch F, Pribil C, Jankowski R, Klossek JM, Chanal I, El Hasnaoui A. Nasal polyposis in France: impact on sleep and quality of life. J Laryngol Otol. 2005 Jul;119(7):543-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- N. Bhattacharyya and L. N. Lee, “Evaluating the diagnosis of chronic rhinosinusitis based on clinical guidelines and endoscopy,” Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, vol. 143, no. 1, pp. 147–151, Jul. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Djupesland PG, Reitsma S, Hopkins C, Sedaghat AR, Peters A, Fokkens WJ. Endoscopic grading systems for nasal polyps: are we comparing apples to oranges? Rhinology. 2022 Jun 1;60(3):169-176. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E. O. Meltzer et al., “Rhinosinusitis: Developing guidance for clinical trials,” Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, vol. 118, no. 5, pp. S17–S61, Nov. 2006. [CrossRef]

- P. Gevaert et al., “European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology position paper on endoscopic scoring of nasal polyposis,” Allergy, vol. 78, no. 4, pp. 912–922, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Varshney, J. Varshney, S. Biswas, and S. K. Ghosh, “Importance of CT Scan of Paranasal Sinuses in the Evaluation of the Anatomical Findings in Patients Suffering from Sinonasal Polyposis,” Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery, vol. 68, no. 2, pp. 167–172, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. Davies, F. Wu, E. Y. Huang, M. Takashima, N. R. Rowan, and O. G. Ahmed, “Central Compartment Atopic Disease as a Pathophysiologically Distinct Subtype of Chronic Rhinosinusitis: A Scoping Review,” Sinusitis, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 12–26, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Bacher, K. Mermuys, J. Casselman, and H. Thierens, “Evaluation of Effective Patient Dose in Paranasal Sinus Imaging: Comparison of Cone Beam CT, Digital Tomosynthesis and Multi Slice CT,” 2009, pp. 458–460. [CrossRef]

- Lund VJ and Mackay IS, “Staging in rhinosinusitis,” Rhinology, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 183–184, 1993.

- S. G. Brooks et al., “Preoperative Lund-Mackay computed tomography score is associated with preoperative symptom severity and predicts quality-of-life outcome trajectories after sinus surgery,” Int Forum Allergy Rhinol, vol. 8, no. 6, pp. 668–675, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Vlaminck S, Vauterin T, Hellings PW, et al. The importance of local eosinophilia in the surgical outcome of chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2014; 28:260–264.

- Vlaminck S, Casselman J, De Groef K, Van den berghe I, Kuhweide R, Joniau S. Eosinophilic fungal rhinosinusitis (EFRS): a distinct CT/MRI-entity? A European experience. BENT 2005; 1(2):73-82.

- Vlaminck S.; Prokopakis, E.; Kawauchi, H.; Haspeslagh, M.; Van Huysse, J.; Simões, J.; Acke, F.; Gevaert, P. Proposal for Structured Histopathology of Nasal Secretions for Endotyping Chronic Rhinosinusitis: An Exploratory Study. Allergies 2022, 2, 128–137. [CrossRef]

- S. Erskine et al., “A cross sectional analysis of a case-control study about quality of life in CRS in the UK; a comparison between CRS subtypes,” Rhinology journal, vol. 54, no. 4, pp. 311–315, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. P. Hoehle, K. M. Phillips, R. W. Bergmark, D. S. Caradonna, S. T. Gray, and A. R. Sedaghat, “Symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis differentially impact general health-related quality of life,” Rhinology journal, vol. 54, no. 4, pp. 316–322, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- N. Bhattacharyya, “Incremental Health Care Utilization and Expenditures for Chronic Rhinosinusitis in the United States,” Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, vol. 120, no. 7, pp. 423–427, Jul. 2011. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Smith, R. R. Orlandi, and L. Rudmik, “Cost of adult chronic rhinosinusitis: A systematic review,” Laryngoscope, vol. 125, no. 7, pp. 1547–1556, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Rudmik, “Economics of Chronic Rhinosinusitis,” Curr Allergy Asthma Rep, vol. 17, no. 4, p. 20, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy JL, Hubbard MA, Huyett P, Patrie JT, Borish L, Payne SC. Sino-nasal outcome test (SNOT-22): a predictor of postsurgical improvement in patients with chronic sinusitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;111(4):246-251.e2. [CrossRef]

- Khan AH, Reaney M, Guillemin I, Nelson L, Qin S, Kamat S, Mannent L, Amin N, Whalley D, Hopkins C. Development of Sinonasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22) Domains in Chronic Rhinosinusitis With Nasal Polyps. Laryngoscope. 2022 May;132(5):933-941. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toma S, Hopkins C. Stratification of SNOT-22 scores into mild, moderate or severe and relationship with other subjective instruments. Rhinology. 2016;54(2):129-33.

- De Dorlodot C, et al. French adaptation and validation of the sino-nasal outcome test-22: a prospective cohort study on quality of life among 422 subjects. Clin Otolaryngol. 2015; 40(1): 29-35. [CrossRef]

- D. Passali, L. M. Bellussi, V. Damiani, M. A. Tosca, G. Motta, and G. Ciprandi, “Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis: the role of personalized and integrated medicine.,” Acta Biomed, vol. 91, no. 1-S, pp. 11–18, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Mygind and V. Lund, “Intranasal Corticosteroids for Nasal Polyposis,” Treat Respir Med, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 93–102, 2006. [CrossRef]

- S. Tait, D. Kallogjeri, J. Suko, S. Kukuljan, J. Schneider, and J. F. Piccirillo, “Effect of Budesonide Added to Large-Volume, Low-pressure Saline Sinus Irrigation for Chronic Rhinosinusitis,” JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery, vol. 144, no. 7, p. 605, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Jung, J. H. Kwak, M. K. Kim, K. Tae, S. H. Cho, and J. H. Jeong, “The Long-Term Effects of Budesonide Nasal Irrigation in Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Asthma,” J Clin Med, vol. 11, no. 10, p. 2690, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- D.-Y. Park et al., “Clinical Practice Guideline: Nasal Irrigation for Chronic Rhinosinusitis in Adults,” Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 5–23, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Ahamed, D. Samson, R. Sundaresan, B. Balasubramanya, and R. Thomas, “Double Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Budesonide and Saline Nasal Rinses in the Post-operative Management of Chronic Rhinosinusitis,” Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery, vol. 76, no. 1, pp. 408–413, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Yamada, S. Fujieda, S. Mori, H. Yamamoto, and H. Saito, “Macrolide Treatment Decreased the Size of Nasal Polyps and IL-8 Levels in Nasal Lavage,” Am J Rhinol, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 143–148, May 2000. [CrossRef]

- T. Van Zele et al., “Oral steroids and doxycycline: Two different approaches to treat nasal polyps,” Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, vol. 125, no. 5, pp. 1069-1076.e4, May 2010. [CrossRef]

- D. M. Poetker, S. Mendolia-Loffredo, and T. L. Smith, “Outcomes of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery for Chronic Rhinosinusitis associated with Sinonasal Polyposis,” Am J Rhinol, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 84–88, Jan. 2007. [CrossRef]

- R. Wynn and G. Har-El, “Recurrence Rates after Endoscopic Sinus Surgery for Massive Sinus Polyposis,” Laryngoscope, vol. 114, no. 5, pp. 811–813, May 2004. [CrossRef]

- Laure-Marine Piquet. Prise en charge chirurgicale de la polypose naso-sinusienne : indications et résultats. Médecine humaine et pathologie. 2019. ffdumas-02297746.

- C. Bachert, L. Zhang, and P. Gevaert, “Current and future treatment options for adult chronic rhinosinusitis: Focus on nasal polyposis,” Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, vol. 136, no. 6, pp. 1431–1440, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Alsharif S, Jonstam K, van Zele T, Gevaert P, Holtappels G, Bachert C. Endoscopic Sinus Surgery for Type-2 CRS wNP: An Endotype-Based Retrospective Study. Laryngoscope. 2019 Jun;129(6):1286-1292. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes SC, Cavaliere C, Masieri S, Van Zele T, Gevaert P, Holtappels G, Zhang N, Ramasamy P, Voegels RL, Bachert C. Reboot surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis: recurrence and smell kinetics. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2022 Dec;279(12):5691-5699. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EUFOREA expert board meeting on uncontrolled severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) and biologics: Definitions and management Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Volume 147, Issue 5, May 2021, Pages 1981-1982. [CrossRef]

- Fokkens WJ, Lund V, Bachert C, et al.EUFOREA consensus on biologics for CRSwNP with or withoutasthma. Allergy 2019;74:2312-2319. [CrossRef]

- Calus L, Van Bruaene N, Bosteels C, Dejonckheere S, Van Zele T, Holtappels G, Bachert C, Gevaert P. Twelve-year follow-up study after endoscopic sinus surgery in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis. Clin Transl Allergy. 2019 Jun 14;9:30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EUFOREA consensus on biologics for CRSwNP with or without asthma. Fokkens WJ, Lund V, Bachert C, Mullol J, Bjermer L, Bousquet J, Canonica GW, Deneyer L, Desrosiers M, Diamant Z, Han J, Heffler E, Hopkins C, Jankowski R, Joos G, Knill A, Lee J, Lee SE, Mariën G, Pugin B, Senior B, Seys SF, Hellings PW.Allergy. 2019 Dec;74(12):2312-2319. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EUFOREA expert board meeting on uncontrolled severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) and biologics: Definitions and management.Bachert C, Han JK, Wagenmann M, Hosemann W, Lee SE, Backer V, Mullol J, Gevaert P, Klimek L, Prokopakis E, Knill A, Cavaliere C, Hopkins C, Hellings P.J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021 Jan;147(1):29-36. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fokkens WJ, Viskens AS, Backer V, Conti D, De Corso E, Gevaert P, Scadding GK, Wagemann M, Bernal-Sprekelsen M, Chaker A, Heffler E, Han JK, Van Staeyen E, Hopkins C, Mullol J, Peters A, Reitsma S, Senior BA, Hellings PW. EPOS/EUFOREA update on indication and evaluation of Biologics in Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps 2023. Rhinology. 2023 Jun 1;61(3):194-202. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fokkens WJ, Viskens AS, Backer V, Conti D, De Corso E, Gevaert P, Scadding GK, Wagemann M, Bernal-Sprekelsen M, Chaker A, Heffler E, Han JK, Van Staeyen E, Hopkins C, Mullol J, Peters A, Reitsma S, Senior BA, Hellings PW. EPOS/EUFOREA update on indication and evaluation of Biologics in Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps 2023. Rhinology. 2023 Jun 1;61(3):194-202. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gevaert P, Calus L, Van Zele T, Blomme K, De Ruyck N, Bauters W, Hellings P, Brusselle G, De Bacquer D, van Cauwenberge P, Bachert C. Omalizumab is effective in allergic and nonallergic patients with nasal polyps and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013 Jan;131(1):110-6.e1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gevaert P, Omachi TA, Corren J, Mullol J, Han J, Lee SE, Kaufman D, Ligueros-Saylan M, Howard M, Zhu R, Owen R, Wong K, Islam L, Bachert C. Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in nasal polyposis: 2 randomized phase 3 trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020 Sep;146(3):595-605. Erratum in: J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021 Jan;147(1):416. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gevaert P, Saenz R, Corren J, Han JK, Mullol J, Lee SE, Ow RA, Zhao R, Howard M, Wong K, Islam L, Ligueros-Saylan M, Omachi TA, Bachert C. Long-term efficacy and safety of omalizumab for nasal polyposis in an open-label extension study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022 Mar;149(3):957-965.e3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gevaert P, Mullol J, Saenz R, Ko J, Steinke JW, Millette LA, Meltzer EO. Omalizumab improves sinonasal outcomes in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps regardless of allergic status. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024 Mar;132(3):355-362.e1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gevaert P, Han JK, Smith SG, Sousa AR, Howarth PH, Yancey SW, Chan R, Bachert C. The roles of eosinophils and interleukin-5 in the pathophysiology of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2022 Nov;12(11):1413-1423. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gevaert P, Van Bruaene N, Cattaert T, Van Steen K, Van Zele T, Acke F, De Ruyck N, Blomme K, Sousa AR, Marshall RP, Bachert C. Mepolizumab, a humanized anti-IL-5 mAb, as a treatment option for severe nasal polyposis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Nov;128(5):989-95.e1-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han JK, Bachert C, Fokkens W, Desrosiers M, Wagenmann M, Lee SE, Smith SG, Martin N, Mayer B, Yancey SW, Sousa AR, Chan R, Hopkins C; SYNAPSE study investigators. Mepolizumab for chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (SYNAPSE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021 Oct;9(10):1141-1153. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachert C, Sousa AR, Lund VJ, Scadding GK, Gevaert P, Nasser S, Durham SR, Cornet ME, Kariyawasam HH, Gilbert J, Austin D, Maxwell AC, Marshall RP, Fokkens WJ. Reduced need for surgery in severe nasal polyposis with mepolizumab: Randomized trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017 Oct;140(4):1024-1031.e14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachert C, Han JK, Desrosiers M, Hellings PW, Amin N, Lee SE, Mullol J, Greos LS, Bosso JV, Laidlaw TM, Cervin AU, Maspero JF, Hopkins C, Olze H, Canonica GW, Paggiaro P, Cho SH, Fokkens WJ, Fujieda S, Zhang M, Lu X, Fan C, Draikiwicz S, Kamat SA, Khan A, Pirozzi G, Patel N, Graham NMH, Ruddy M, Staudinger H, Weinreich D, Stahl N, Yancopoulos GD, Mannent LP. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in patients with severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (LIBERTY NP SINUS-24 and LIBERTY NP SINUS-52): results from two multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2019 Nov 2;394(10209):1638-1650. Erratum in: Lancet. 2019 Nov 2;394(10209):1618. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comparative efficacy and safety of monoclonal antibodies and aspirin desensitization for chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis: A systematic review and networkmeta-analysis. Paul Oykhman, MD, MSc,a Fernando Aleman Paramo, MD,a Jean Bousquet, MD,d,e,f David W. Kennedy, MD,g Romina Brignardello-Petersen, PhD,b and Derek K. Chu, MD, PhDa,b,cJ ALLERGY CLIN IMMUNOLAPRIL 2022.

- Haxel BR, Hummel T, Fruth K, Lorenz K, Gunder N, Nahrath P, Cuevas M. Real-world-effectiveness of biological treatment for severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Rhinology. 2022 Dec 1;60(6):435-443. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu Q, Zhang Y, Kong W, Wang X, Yuan L, Zheng R, Qiu H, Huang X, Yang Q. Which Is the Best Biologic for Nasal Polyps: Dupilumab, Omalizumab, or Mepolizumab? A Network Meta-Analysis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2022;183(3):279-288. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severe hypereosinophilia in a patient treated with dupilumab and shift to mepolizumab: the importance of multidisciplinary management. A case report and literature review.Munari S, Ciotti G, Cestaro W, Corsi L, Tonin S, Ballarin A, Floriani A, Dartora C, Bosi A, Tacconi M, Gialdini F, Gottardi M, Menzella F.Drugs Context. 2024 May 22;13:2024-3-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cells : eosino/neutron | IgE (tot or specific |

Pathogens Staphylo or other |

Cytokines | Other mediators | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | + | + | (+) | (+) | |

| Culture Swab | + | ||||

| Nasal secretion | + | + | + | + | |

| Nasal cytology | + | ||||

| Tissue | + | + | + | + | |

| Nasal NO | (+) |

| Controls | Chronic sinusitis | Nasal polyps | Cystic fibrosis: nasal polyps | One-way Anova Fisher test |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 10 | 10 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| Ct score/ Lund & Mackay | 0.75 (0-2) | 6 (2-11) | 16.3 (7-24) | 14.5 (5-20) | <0.0001 |

| Polyp score (Davos) | 0 | 0 | 4.8 (2-6) | 2.9 (0-6) | <0.0001 |

| Total symptom score | 4(3-5) | 6.6 (4-10) | 9.6 (3-14) | 4.3 (0-9) | <0.0001 |

| Nasal congestion | 1.1 (0-3) | 1.0 (0-3) | 2.6 (0-3) | 2.8 (2-3) | 0.001 |

| Sneezing | 0 | 0.1 (0-1) | 0.2 (0-2) | 0.6 (0-2) | 0.761 |

| Rhinorea | 0.3 (0-2) | 1.6 (0-3) | 1.6 (0-3) | 1.0 (0-3) | 0.19 |

| Loss of smell | 0 | 0 | 2.3 (0-3) | 1.0 (0-3) | <0.0001 |

| Postnasal drip | 0 | 1.4 (0-2) | 1.3 (0-3) | 0.6 (0-2) | 0.001 |

| Headache | 0.9 (0-2) | 2.5 (1-3) | 1.6 (0-3) | 1.2 (0-3) | 0.003 |

| Benefits | Weakness | |

|---|---|---|

| Oral corticosteroids | Big improvement of the major symptoms Improvement of the HRQL: Improvement of the sleep quality, sense of smell, reduction of the facial pain, reduction of nasal blockage |

Frequent and early recurrence of the symptoms Rebound effect Advers events: gain of weight, anxiety, nervosity, irritability Osteoporosis, diabetes melittus, necrosis of the head of the hip |

| Sinus surgery | Improvement of the HRQL Good outcome after a short and middle term |

Frequent recurrence of the disease Iatrogenicity Need for a general anesthesia Possibility of minor and major intraoperative and postoperativecomplications |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).