1. Introduction

Peanuts (Arachis hypogaea L), commonly known as groundnuts, are an annual crop belonging to the family Leguminosae family mainly grown in the arid savannah zones of western Kenya (MoA, 2009). Women are actively involved in planting, harvesting, processing, and selling, and they are widely grown for both personal and commercial purposes (Daudi et al., 2018). Peanuts are a high-value, easily marketable, and nutritious food that is utilised as an ingredient in many traditional recipes and snacks as a primary source of energy, protein, vitamins, and minerals. Peanuts are a good source of total calories, fat, and essential vitamins and minerals (WHO, 2002). Peanuts are an important crop to Kenya's food security. According to food availability data from the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) database for 2021, peanuts contributed significantly to food security when compared to other food crops such as cereals. Peanuts contributes to about 16% of the food available in other regions of the world (FAO,2021). Embracing new agricultural technologies in Kenya can help peanut farmers to gain an unusual opportunity to improve productivity, household income, and nutrition. Despite this, peanut value chain is a relatively neglected in Kenya (FAO, 2021).

Peanut farming is an important livelihood activity by many rural communities around the world. Peanuts are consumed in many parts of the world as peanut butter, peanut oil, salted and roasted and consumed as a confectionery snack, or used in sweets. They are boiled and consumed in other regions of the world, either in the shell or unshelled (Bioversity International, 2017). Peanut grows well in the arid and semi-arid tropics, requires little input, and integrates well into rainfed crop rotations and intercrop systems. In some nations, semi-arid tropics accounts for up to 60% of crop production land. Many different types of peanut are grown throughout Africa. These differ greatly in crucial properties such as the number of seeds per pod, the colour of the seed coat, the size of the seed, the time to maturity of the crop, the dormancy of the seed after harvest, the oil content, and the taste (IFAD, 2009).

Under the First Medium-Term Plan (MTP1), the Kenyan Government vision 2030 identified the need for investments to assist farmers to transition from subsistence agriculture to increasingly appealing commercial farming (MoA, 2019). This plan prioritises agricultural output, particularly in rural regions, in order to alleviate poverty among smallholder farmers while also connecting local farms to available markets through farmer education and extension services. Peanut growing regions in Nyanza Kenya, such as Homa-Bay, Kisumu, Migori and Siaya Counties, have listed peanut as their priority crop for advancement in their agricultural strategic plans (CIDP, 2018-2022).

Over time, national governments and international agencies such as USAID and UKAID have discovered that improving agricultural value chain efficiency, increasing access to diverse markets, and providing extension services to encourage farmers to embrace modern production technologies are all cost-effective ways to achieve poverty reduction and economic empowerment for smallholder farmers (USAID, 2018).

2. Peanut production trend in Kenya

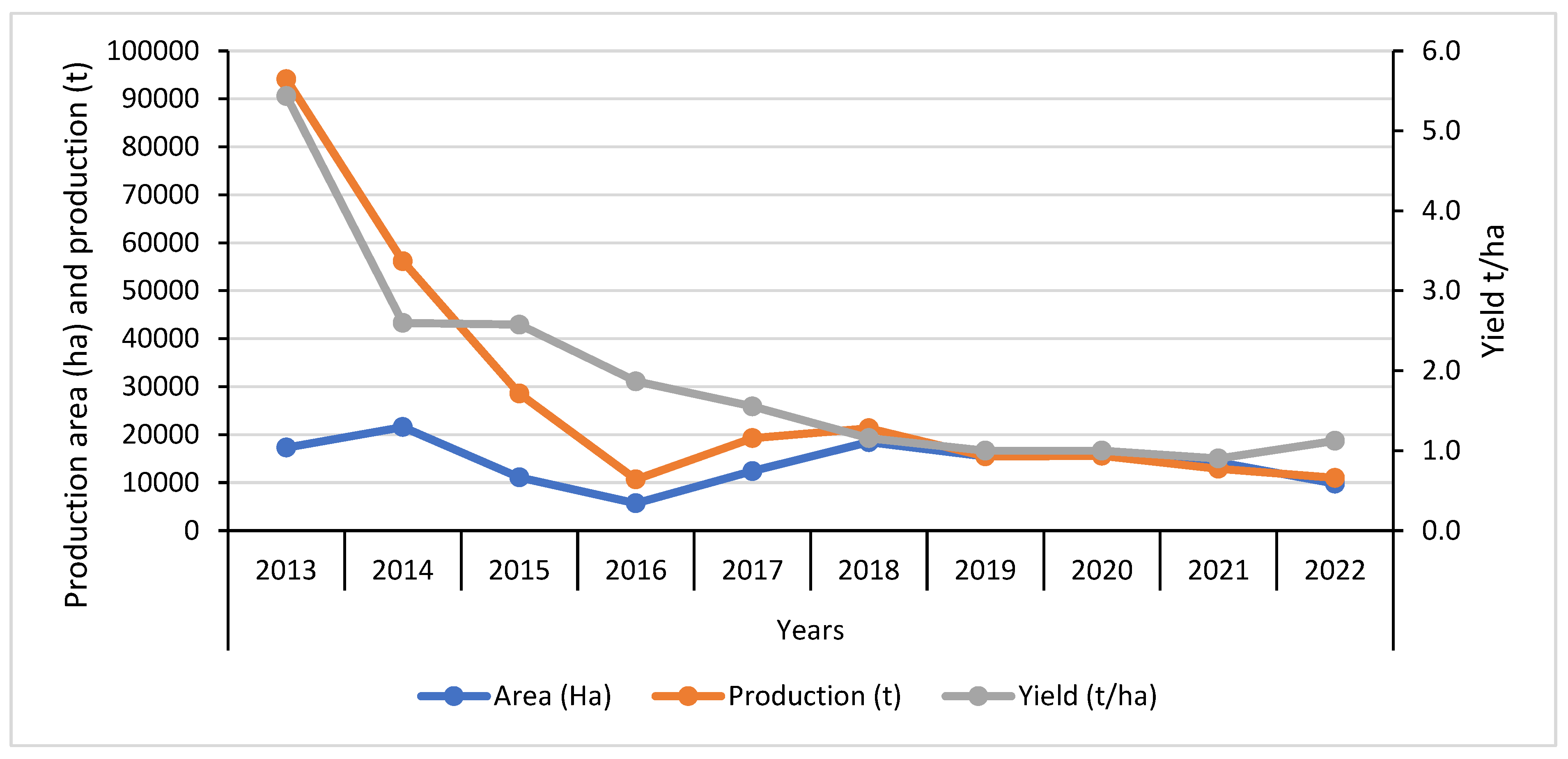

In Kenya, peanut production is currently not considered a commercially viable farming activity (business) and there are no structured marketing channels for peanut in Kenya. Peanut production data is not well documented and reported by the Ministry of Agriculture in the annual statistical reports. The official production data shown in

Figure 1 suggest that production was peaked in 2013 with the area under peanut production being 17,311ha, with a production of 94,072t and an average yield of 5.4t/ha. 2016 recorded the lowest harvested area of 5,725ha, production of 10,687.2t and an average yield of 1.9t/ha. However, 2018 recorded the highest harvested area of 18,449ha with a production of 21,333t. This significant decline in production continued from 2018 to 2022. Indicating a decrease in production, area under cultivation and yield within the period by 83,000t, 7500ha and 4.3t/ha respectively (FAO, 2022).

However, local demand for peanuts have been on the rise resulting in traders importing peanuts from Italy and India to complement national production (FAO, 2022). According to data from FAOSTAT (2022), western Region accounts for about 87.4% of 2022 total production, followed by coastal Region with about 11.3% and 1.3% came from other regions of the country. As demand for peanut is increasing, the production is decreasing creating a huge demand gap. The reasons for the decline in production is mainly due to reduction in land size resulting from farmers shifting more attention to other competing crops such as maize (FAO, 2022). The increased demand is influenced by population growth, cultural and culinary preferences nutritional requirements, industrial use and export market (KNBS, 2022).

MTP1 of Kenya's government intends to promote good agricultural practises (GAPs) in agricultural production and facilitate market access through collaboration with local authorities and value chain participants in the public and private sectors. Based on the government's Food and Agriculture Sector Development Policy (FASDEP), the MTP1 identifies peanut as one of the priority crops in the western portions of the country (MoA, 2017). According to MTP1, peanuts are unique among the country's traditional staple crops in that they have the highest commercialization index of 42%. While the MTP1 emphasises the need to increase industrial processing of the country's traditional commercialised smallholder crops, it pays little attention to peanuts production and processing (AFA, 2017).

The key challenges confronting Kenyan agriculture which are highlighted by the plan includes the difficulties of rain-fed agriculture, the low level of mechanisation in production and processing, high post-harvest losses due to poor post-harvest management, low and ineffective agricultural finance, poor extension services due to institutional and structural inefficiencies, and insufficient markets and processing facilities. Identifying the specific challenges in the peanut value chain provides an opportunity to identify upgrading opportunities for strategic investments in the peanut value chain to leverage existing strengths and opportunities. This has the ability to increase efficiency and increase income for all actors in the peanut value chain. This will also create employment opportunities particularly in the rural areas where the peanut is produced. It is in the light of these we find it necessary to analyse the performance of the peanut value chain in the predominant peanut production area of Kenya to explore opportunities to boost the value chain. Specifically, identify the constraints and opportunities at each node of the value chain; analyse the financial and market values across the entire chain and suggest policy recommendations for the development of a sustainable peanut value chain in Kenya.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Study area

This research was conducted in the Nyakach and Karachuonyo sub-county areas of Kenya, which are regarded to be within Lake Victoria Basin. Lake Victoria Basin has Savanna climate characteristics that are suitable for peanut production. It has altitudinal variations ranging from 1131m to 4000m and temperatures ranging from 64 °F to 88 °F (20 to 30 °C). Because of the location's proximity to Lake Victoria, relative humidity is fairly high in both counties (Kenya Metropolitan Department 2019). The two study sites, Karachuonyo and Nyakach sub-counties, are located within Homabay and Kisumu counties. The Lake Basin region is one of the food baskets with a unique history of intense agricultural activity among the local communities. Most communities within the two sub-counties comprise farming households with similar agricultural systems and are actively engaged in food crop production (KNBS, 2021). The inhabitants of Karachuonyo are known to have semi-arid climatic conditions favouring crops such as peanuts, cowpeas, yams, soya, sorghum, cassava, millet, and simsim, which are currently neglected and underutilised with value chains underdeveloped. Even though the country continues to import such crops from neighbouring counties like Kisii, Nyamira and Migori to the south and Siaya County to the North, the communities in these two study sites have a common farming practices with similar cultural beliefs and values (KNBS, 2019).

The Lake Victoria Basin Region is well-known for its thriving agriculture industries. The agro ecological zones has also influenced the research locations. Both sites are located within the Lake Victoria basin, which receives conventional rainfall throughout the year, with the major long rainy season being between April and June and the short rainy season occurring between September and December. Due to the vast agricultural markets, the two study areas also represent the nation's major food basket and are thus highly influenced by market pressures. At the same time, the area is entirely dependent on rainfed agriculture, necessitating the need for drought-resistant crop species in the face of climate change.

3.2. Value Chain Analyses framework

The value chain analysis approach consists of several steps that must be completed sequentially. This study was guided by a value chain analysis framework developed by the EWA-BELT project (Bidzakin et al., 2021). This was developed considering the works of Porter (1985), M4P (2008), Dabat (2018), Usman (2016), and Rashid (2019). This framework is comprised of five major steps; Step 1 involves mapping out the Value chain to identify the different nodes of the chain and identify the actors at the various nodes. This is accomplished through Focus Group Discussion (FGD) sessions with a chosen group of value chain actors. Step 2 involves identifying the constraints and opportunities at the various nodes of the value chain using SWOT analyses. SWOT analysis is carried out at the different nodes of the chain to identify the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats to enable us recommended and propose solutions that can mitigate the weakness and threats to leverage the strengths and opportunities for a boosted peanut value chain. Step 3 involves gathering market data and analysing the market and financial values, identifying support services and product flow and distribution within the value chain. Market data is collected at all the nodes to facilitate the estimation of net margins, market margins, benefit cost ratios, return on investment at the various notes. This is aimed at helping us understand the distribution of market and financial values across the chain. This is very useful in developing strategies to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the chain. This will also help with ensuring equity which is very essential for the sustainability of any value chain. Step 4 involves the identification, and promotion of recommended options to boost the chain. This entails making comprehensive recommendations on what should be implemented in the value chain to boost the value chain across all the notes to ensure equity, effectiveness, and efficiency across the value chain.

3.3. Research design and primary data collection

A mixed-methods strategy was applied in this study, which is referred to as a "qual quant" approach by Gerring (2007). This approach is also referred to as "integrated research paradigm" by Saunders (2007). This approach incorporates multiple schools of philosophy, such as positivism, interpretivism, and realism. According to Saunders (2007), the mixed-method approach is typically utilised when researchers want to get a more comprehensive and in-depth understanding of a research subject.

This strategy allows for the collection of both qualitative and quantitative data from study participants. This form is popular because it allows for a wide range of analytical tools, including both econometric and non-econometric analysis. The study employed qualitative approaches such as focus group discussions, key informant interviews, life history, and field observations. A survey instrument was also developed and employed to help collect quantitative and qualitative data. Secondary data was obtained from sources such as journal articles, newsletters, yearly reports, presentations at conferences, and annual statistics reports.

Value Chain Actors Survey: A survey questionnaire was developed and administered to randomly selected peanut value chain actors (producers, traders and processors) in the study area. Respondents were met at their homes and their consent sought before their participation in the study. Eight focus group discussions were held in accordance with the research objectives, using a pre-determined checklist of questions to guide. FGDs are deemed ideal for the study because it provides a platform for dynamic interaction between researchers and participants, which often results in the collection of valuable information. Each of the two study sites had four focus group sessions. Each focus group consisted of ten (10) respondents, primarily value chain actors over the age of twenty-five, with over five years of experience in the peanut value chain were selected to participate.

Key Informant Interviews: These were used to acquire an in-depth understanding of the history of the peanut value chain in the studied locations. Ten key informants were interviewed at various levels of the value chain, with people believed to have extensive knowledge of the peanut value chain. The informants were mostly traders, processors and agricultural extension officers from the Ministry of Agriculture, from the study area. The key informants were chosen based on their education and understanding of agricultural activities in the research area.

Field observations: The researcher attended certain local events and visited local markets, as well as other locations of interest, to witness some activities and practises as part of efforts to acquaint and comprehend the people's way of life and to interpret their comments. The observational procedure, which comprised of a form prepared expressly to record information during the observation time, was used to conduct the observations.

Sampling technique and sample size

A multi-stage sampling technique was used in this study. The research regions were chosen based on their long history of peanut cultivation and the suitable climatic conditions that are ideal for peanut production. Farmers, traders, aggregators and processors along the value chain were randomly selected and interviewed. The total sample size for this study was 120, which included 60 farmers from the two locations and 20 each of aggregators, traders and processors from the study area as shown in

Table 1.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Demographic information of the participants

The results in

Table 2 indicates that out of the 120 farmers sampled the majority of them were women (68%). This result indicates there were more female peanut farmers than their male counterparts. The findings are similar to the work of Wanyama (2013) on peanut farmers in Rongo and Ndhiwa. The majority of distributors in the value chain were female (70%). A similar trend was observed among aggregators, traders, and processors with female participation at 70%, 60% and 60% respectively. These results indicate that the peanut industry is female dominated right from the production to processing nodes. About 70% of all value chain actors have at least primary education as shown in

Table 2.

4.2. SWOT analysis of the peanut value chain

4.2.1. SWOT analyses at the input supply node

The peanut value chain begins with peanut farm input suppliers who supply inputs such as seeds, agrochemicals, pesticides, etc. to producers. The study found that 73% of peanut producers get their seeds from saved seed, which aligns with findings from a study by Owusu (2017) in Ghana, which found that 59% of farmers get their peanut seeds from previous year production. Only 20% of farmers buy seed from input suppliers, and 7% receive seed as a gift from family and friends. Peanut farmers do not use fertiliser in their peanut cultivation. The strength identified is availability of technical know-how. The weakness is the low awareness of improved varieties. The identified opportunities include high demand for certified seed, favourable policy environment, and threats are short shelf life, high cost of transportation, low market price at harvest (see

Table 3). This low adoption of improved varieties and fertilizer is a major contributor to the low yields and production trend reported on peanut production in Kenya.

4.2.2. The peanut production node

Peanut production occurs primarily in rural areas and is controlled by smallholder farmers, the majority of whom are female (68%). Despite being dominated by females, there is significant male engagement when compared to other crops such as sorghum and finger millet (Wanyama, 2013). This contrasts the findings of Owusu (2017) in Ghana, who found that the majority of peanut producers are men. Land preparation, sowing, and weed control; pest and disease control; harvesting; and post-harvest management are some of the production activities. In certain cases, peanut farmers engage workers to perform tasks such as weeding and harvesting peanuts. However, in most cases, family labour is used in addition to contracted labour to reduce labour costs. For peanut production, 5% utilise only hired labour, 17% use mixed labour (hired and family), and the remaining 78% use only family labour.

Peanut production in this area is heavily reliant on rainfed production, with two rain seasons: main season from April to August and short season from September to October. Farm sizes are typically small, averaging 0.2ha. This agrees with the findings of Wanyama (2013) which indicates that peanuts are predominantly grown on a modest scale, with farm sizes ranging from 0.5 to 1.5 acres. Depending on the weather, harvested nuts are sun-dried for two weeks. Approximately 56% of the farmers who participated in the survey sell their peanuts largely unshelled, whereas 44% sell them shelled. Unshelled peanuts typically command cheaper pricing than shelled peanuts. Farmers that used both local and improved seed types had the same acreage on average. Per season, the average area was 0.5 acres. According to the findings, yield of farmers who used improved varieties were about 70% greater than the yields of farmers who used the unimproved local seed varieties. Farmers grew peanuts primarily for personal consumption. The surplus was sold at varied prices through various market channels. According to Agriculture and Food Authority (2021), the yields ranged between 2-3 tons per hectare across all the production zones and the farmer gate prices ranged between USD. 2.67/kg to USD. 3.87. 500/Kg. Structured market prices were about 40% higher that the open market price.

The strengths at the producer node include access to improved seeds, high profit margins. The weakness identified is the inability of producers to grade and ensure standardization. The opportunities for peanut producers include high market demand, low input requirement, availability of improved varieties. The threats include pest and diseases, short shelf life of peanuts, low awareness of the nutritional benefits, poor road network, seasonal glut presenting an opportunity for the node to be enhanced when they are addressed (

Table 4).

4.2.3. The peanuts trader node

Women dominate the peanut marketing node, which encompasses aggregation, wholesale and retail services for both raw and processed peanuts. Women make up the majority of retail node actors. There are no trader associations, traders work individually. The market determines peanut pricing through laissez-faire methods. This indicates that there is no standard market price and that each market participant has the freedom to set his or her own price. The market allows for unrestricted entry and exit. Raw peanuts from production locations are sold both locally and internationally. These are traded at the farm gate, local market in the community or an adjacent community, in a wholesale market within the county or area, or a wholesale market beyond the region. Distributors, in addition to acting as market intermediaries, they buy peanuts directly from farmers or markets in production areas and supply them to customers. Rural assemblers (aggregators) in rural communities buy from farmers and sell to wholesalers. Occasionally, a lot of distributors, mainly wholesalers, travel from one village to another or even across the country to Uganda and Tanzania to purchase peanuts. This is mostly done during the off-season when local supply is low.

The majority of assemblers’ finance transactions using their own money. They can also obtain financial advances from wholesalers, who play major roles in rural informal finance. According to Agriculture and Food Authority report (2021), some Nairobi wholesalers do not always travel to producing regions to buy peanuts; instead, they transfer money to their aggregators to aggregate for them. The aggregators, in turn, do all of the purchases and convey the peanuts to the wholesalers.

From the SWOT analyses, the weakness identified at this node is the poor access to market information and threats include short shelf life, poor financial support, poor transport system. The upgrading opportunities are identified from the threats and weaknesses. The opportunities include; available demand, availability of improved varieties. The strengths include access to preferred varieties and market as shown in

Table 5. Increase access to market information, good road and access to financial services will be very useful for improvement in the effectiveness and efficiency of the node that will yield great benefits to the actors.

Traders are mostly specialised in shelled peanuts trade. Majority of traders were found in metropolitan areas. This is due to better access to supplies and the presence of a large number of consumers and retailers. The vast majority of them were sole proprietors. Although the crop is harvested twice a year, the bulk of traders (88.4%) trade in peanuts all year long because peanuts can be stored throughout the year and there is demand throughout the year. Most of the traders’ trade in multiple commodities. Peak peanut availability was observed in April, followed by January, August, and February, which is the period when peanuts are harvested. During the peak of the season, the most common types traded are Red Valencia and Nyahomabay, which were sold both unshelled and shelled in local markets. According to the wholesalers interviewed, the off-peak months for peanuts are September, October, and November. Actually, this is the second planting season. During this time, most of the product harvested in the first season would have been sold or reserved by farmers for their own consumption, resulting in low supply to the market.

Traders sources of peanuts

Peanuts are purchased by traders from a variety of sources. According to the findings, they primarily obtained their peanuts directly from small-scale farmers. Large scale aggregators were the least preferred source (see

Table 6). The proportions obtained from small-scale farmers was about 42.1%, followed by large scale aggregators with 36.9%.

The majority of traders indicated that their suppliers did not offer them with any other services. Credit sales, transportation, storage, and advisory services were some of the few services some few traders indicated they received from their suppliers.

4.2.4. Peanut processors node

The value chain actors at this node are primarily involved with the processing of peanuts, which include shelling, milling into flour and peanut butter, packaging, and selling. Some were involved in the roasting and sale of nuts. The vast majority (96%) stated that they processed peanuts all year. However, there were months of peak supply and low supply, as traders observed. Processors operations are generally at small-scale levels. 60% of the processors interviewed were women. They make peanut butter, roasted peanuts, and other peanut products from peanuts. In rural settings, the majority of processing occurs at the household level. From the study, the SWOT analysis was carried out at this node to identify the challenges and opportunities that exist at this node. In order to leverage on the numerous strengths; knowledge of food safety, low capital requirement, and opportunities such as increasing global demand, high demand and market access. There is the need to address the weaknesses and threats identified such as poor access to storage facilities, poor access to financial products, unstable market prices and poor supply of peanuts. These can be addressed by increase access to storage facilities and knowledge on PHL management. There is also the need to work towards reducing processing cost. Government support to deal with threats like unregulated imports of cheap substitutes, provision of policies to encourage and facilitate standardization and product pricing (

Table 8).

Processors source of peanuts

Peanuts are obtained from a variety of sources, including small-scale farmers, small-scale traders, and large-scale traders. The produce (40%) was obtained from small-scale traders followed by small scale farmers and then aggregators (Table 4.8). The preference for this source was granted because the providers sorted the peanuts before selling them to the next actor in the chain. Only 25% of the processors provided services to the peanut suppliers. The services provided were primarily credit and transportation.

Buying prices of groundnuts at processor level

Table 10 shows the average cost at which processors purchased unshelled and shelled peanuts throughout the peak and off-peak periods. Unshelled peanuts were purchased at a lower price than shelled peanuts, as expected.

Buying prices were projected to be greater during the lean seasons than during the peak season. Because of scarcity, there is upward pressure on prices as demand exceeds supply. Red Valencia was purchased for a higher price than Nyahomabay.

4.2.5. Peanut aggregators node

Aggregators (middlemen) act as a conduit between farmers and traders. These agents are usually farmers or members of the farming community. They typically guide purchasers who are unfamiliar with the whereabouts of various farmers. The main services they provide in the value chain are produce transportation and market information supply. They occasionally buy farmers' products and store it in town centres so that buyers (traders) from urban areas can conveniently get it. They are not always brokering because they follow the orders of urban wholesaler buyers and producers. Most of the time, urban retailers advance them money to buy produce from farmers.

The SWOT analyses identified aggregator easy access to farmers as their strength, farmers interest in selling some of their produce to them and competitive prices offered as the opportunities. The threats identified are; many aggregators in the system resulting in stiff competition, harvesting regimes not the same and low quality of peanuts. These provides opportunities for the aggregator node to be enhanced (see

Table 11).

4.2.6. Peanut consumers’ node

These often purchase pre-sorted and cleaned peanuts from vendors, most of whom are located in local markets and metropolitan areas. Consumers buy either raw or processed products based on their needs and have access to a diverse choice of shops. According to reports, the Kobala and Kong'ou markets are the largest peanut markets in the study region, getting the majority of the peanuts produced in the area every day with approximately over 50 traders. Other markets, like as Homabay Town, Kisumu Town, and Katito, receive peanuts from the area as well. The SWOT analysis at this level of the chain identified the strengths which include; it being affordable, easy to process, and availability of multiple distribution channels. The weakness is high storage loses and the threats include; high price fluctuations, high mycotoxins contamination and short shelf life. These presents opportunities for the upgrade of the node. The opportunities include easy access, high product diversity and easy market access (see

Table 12).

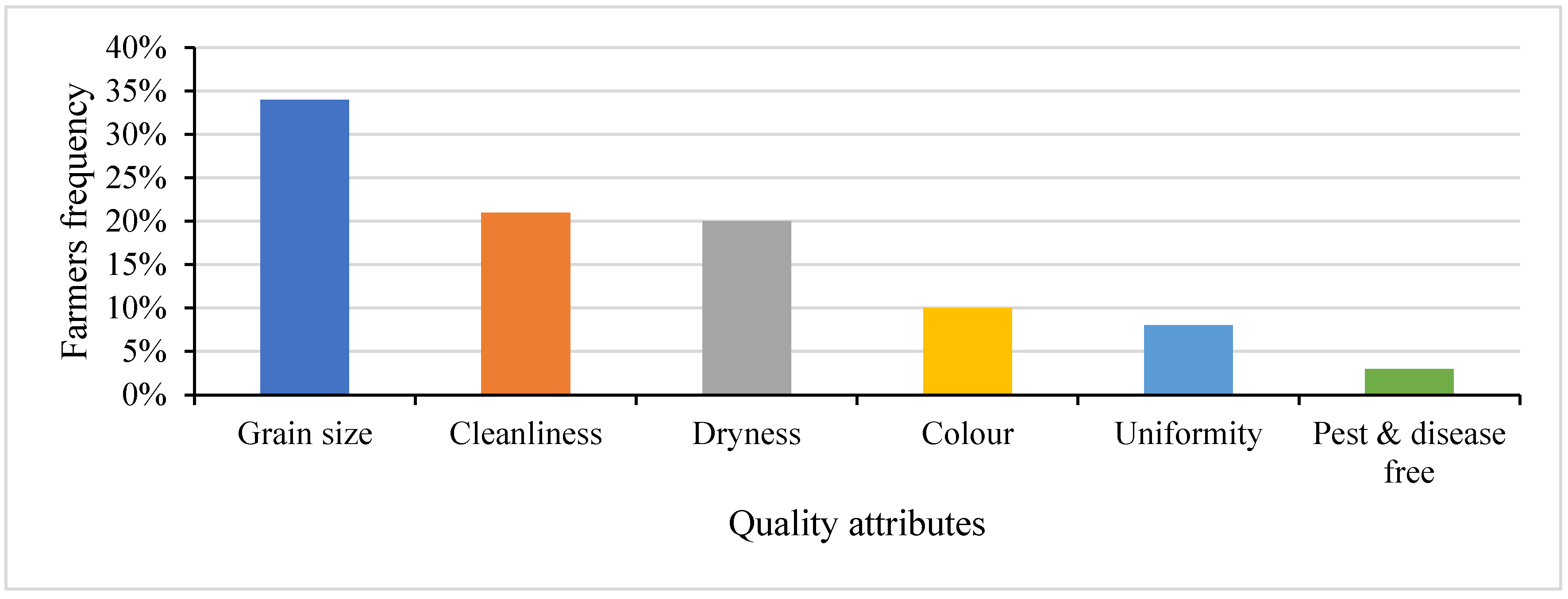

4.3. Quality attributes considered by VC actors

Majority of the value chain actors prefer larger grains (34%) followed by cleanliness of the grains (21%), dryness of the grain (20%), and grain colour (10%) (

Figure 2). Given globalization and export trends, quality is a vital factor that is being emphasized in recent times. Many international and local consumers are demanding for high grain quality. However, maintaining high-quality grains remains a major challenge for chain actors, even though it is important in attracting premium prices and accessing profitable markets.

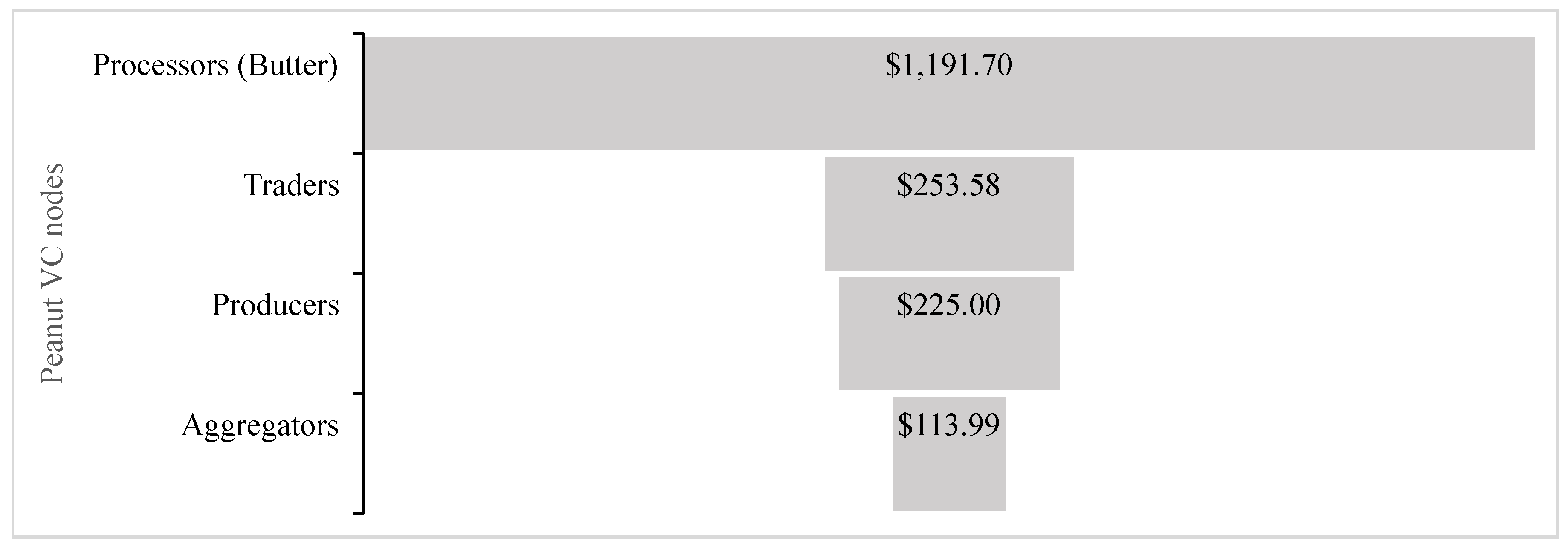

4.4. Financial and market performance analyses of peanut value chain

Financial and market performances of the peanut value chain was assessed. The following indicators were analysed; net margins, benefit cost ratios, return on investment and share of market margins. The net margin analyses of one tonne of peanut transacted across the peanut value chain shows that the processors node recorded the highest net margin of

$1,191 followed by traders, producers, and aggregators with

$254,

$225 and

$114 respectively (see

Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Net margin analyses of one-ton transaction in the peanut value chain .

Figure 3.

Net margin analyses of one-ton transaction in the peanut value chain .

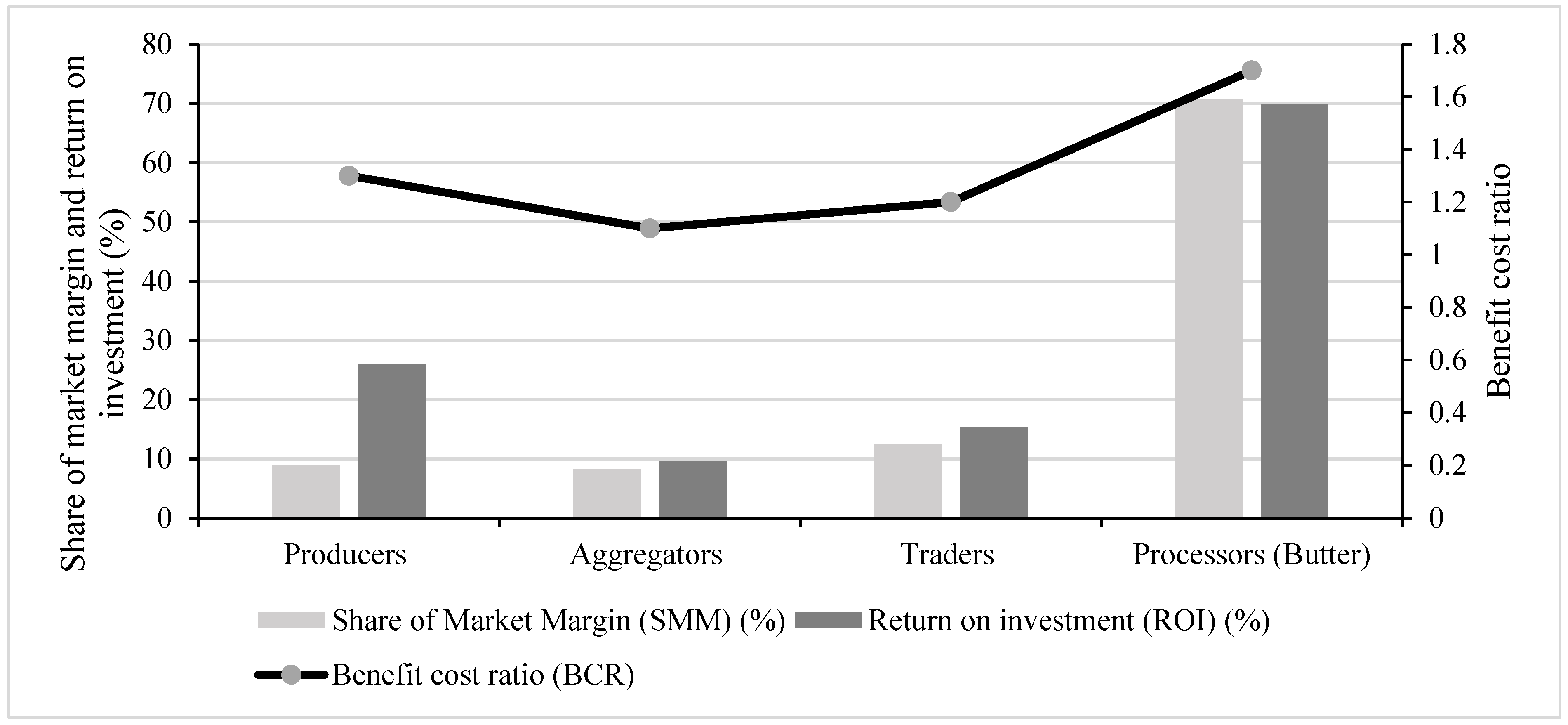

A positive net margin, benefit cost ratio greater than 1 and a positive high RoI implies the company is effective in managing its cost resulting in its revenue been greater that the cost incurred. The one tonne analyses across the chain using benefit cost ratio, share of market margin and return on investment indicators shows that producer node is the most financially viable node followed by processors, traders and then aggregators. This however may not be true if the time of period of these transactions were factored into the analyses. Generally, the indicators show that all nodes of the peanut value chain are all financially viable (

Figure 5). This will imply all nodes were profitable and worth the investment. See appendix A for more details of the financial analyses. Improving upon the effectiveness and efficiency of the chain will mean increase profitability of the chain.

4.5. Peanut Value Chain Map

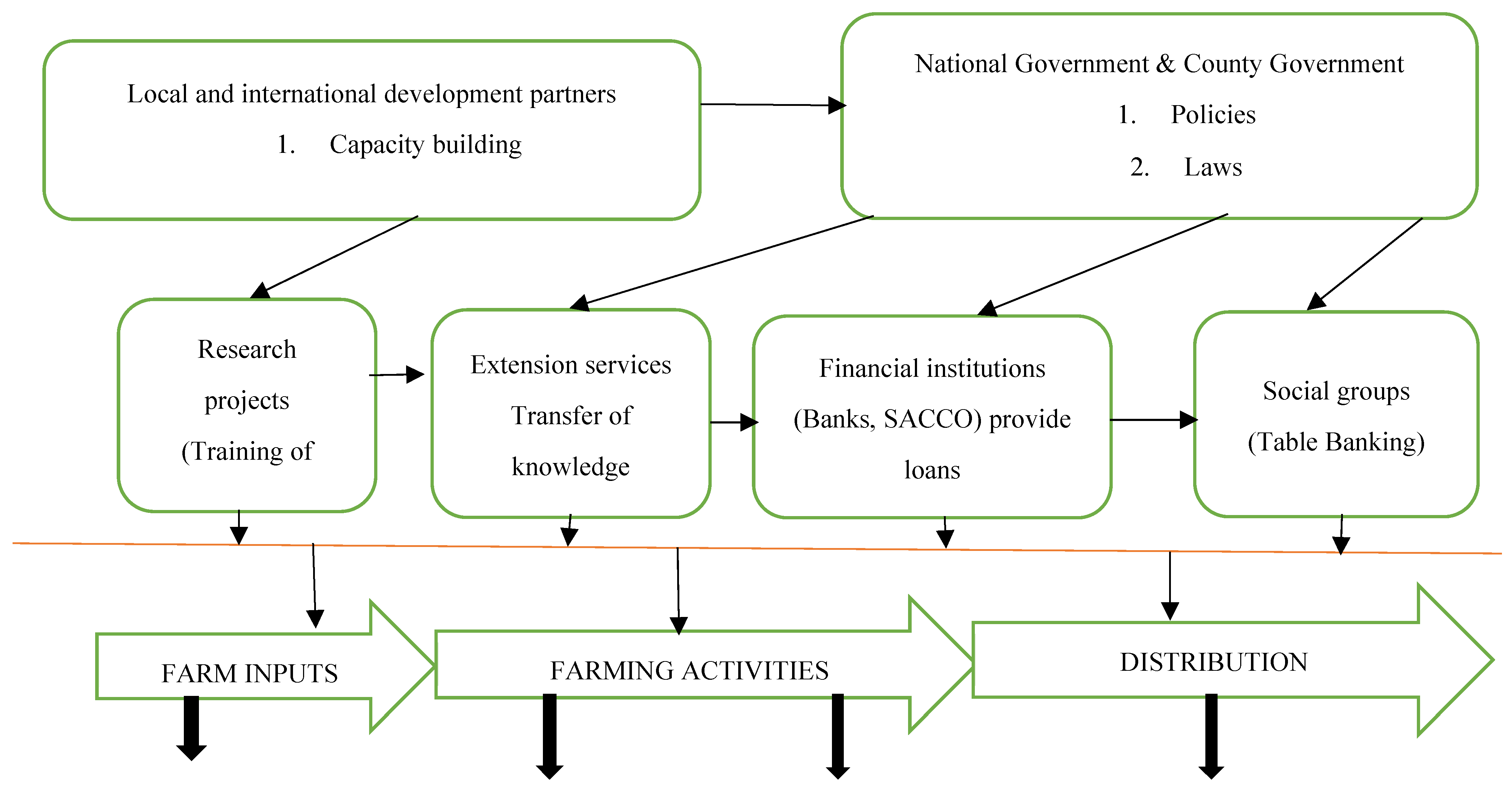

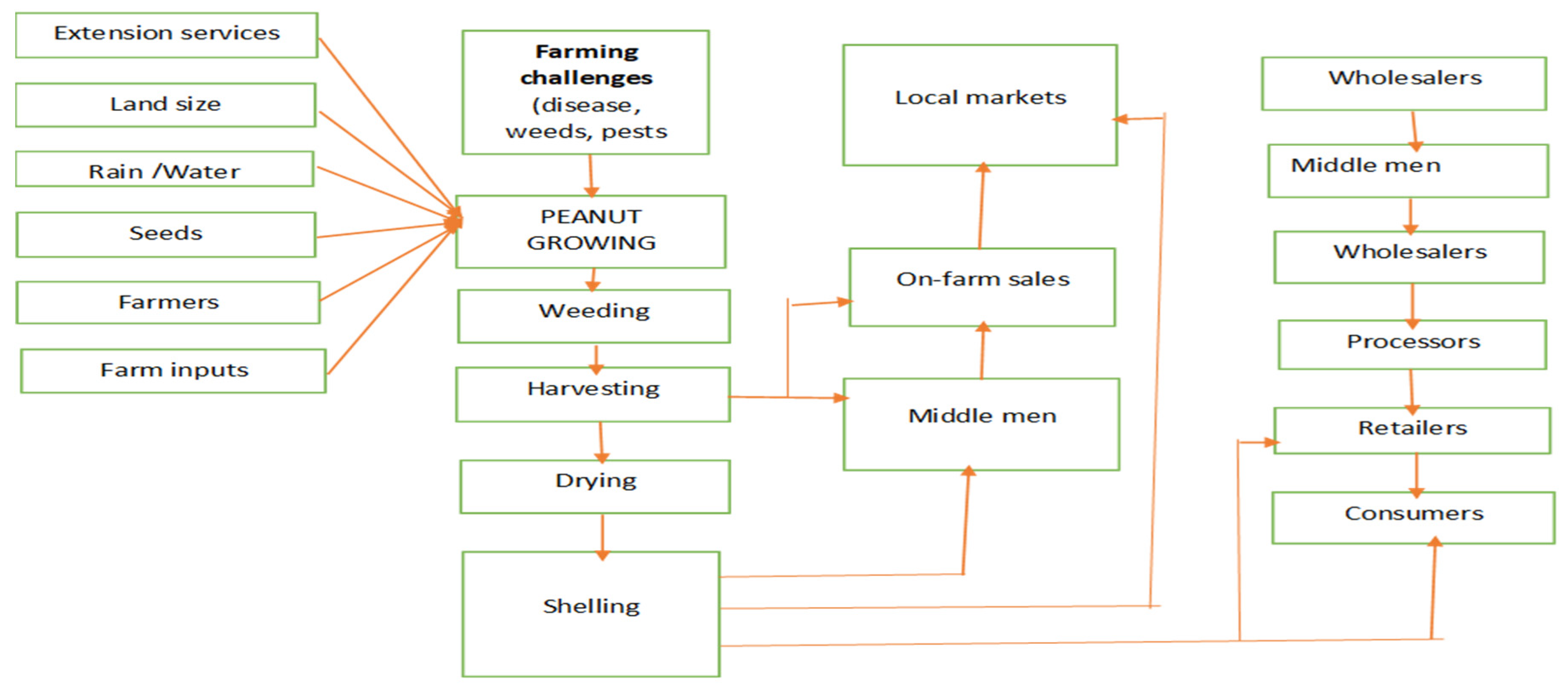

The peanut value chain map provides an overview of the peanut value chain in Kenya, the structure and flow of goods and services, as well as the linkages between various actors operating within the peanut value chain. Following discussion on each node of the chain as peanuts are being transformed from production to finished products ready and available for the final consumption. More than 90% of households grew peanuts, and 72% of them sold some of their crop (KNBS, 2021). There is low input use in peanut production. The current status of the Kenyan peanut value chain is illustrated by

Figure 5, tracing the flow of inputs through production, distribution and to final consumption.

The peanut value chain map illustrates the journey of peanuts from farm inputs through to distribution. At the farm inputs stage, high-quality seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, and irrigation systems are essential for successful cultivation. These resources are critical for ensuring healthy plant growth, maximizing yields, and maintaining crop resilience. Proper tools and equipment also play a significant role in enhancing farming efficiency and productivity.

Moving to farming activities, the process includes land preparation, planting, crop management, and harvesting. Effective land preparation ensures optimal conditions for planting, while ongoing crop management involves pest control, irrigation, and fertilization to support plant health. Harvesting is a crucial step that involves uprooting the mature plants and preparing the peanuts for further processing.

In the distribution stage, peanuts undergo post-harvest handling, including cleaning, sorting, and grading, to maintain quality. Proper storage is essential to prevent spoilage, and efficient transportation ensures timely delivery to processing facilities, markets, or export destinations. Processing converts raw peanuts into value-added products, such as peanut butter and oil. Marketing and sales strategies then facilitate the distribution of these products to consumers through various retail and wholesale channels. Ensuring that peanuts and their products are accessible through diverse outlets and e-commerce platforms helps meet market demand and boosts overall sales.

Optimizing each stage of the value chain—from farm inputs and farming activities to distribution—can enhance efficiency, reduce costs, and increase the value of peanuts. This comprehensive approach supports a well-functioning value chain and benefits all stakeholders involved in the peanut industry.

4.6. Peanut value chain upgrading opportunities

The peanut value chain boosting opportunities identified across the various nodes of the chain are presented in in

Table 17.

Input supply node: The opportunities at the seed supply node include the establishment of more distribution channels to increase accessibility and affordability of seeds. Seed growers need to do more to sensitize farmers of new and improved varieties and demonstrate to farmers the benefits of using these new varieties. There is the need to facilitate the process of seed certification to ensure seed quality is not compromised. This will increase farmer confidence in buying certified seed.

Production node: Sensitization of farmers to use improved seed will help boost peanut production significantly. Market access is also very critical; hence contract production and collective marketing are marketing innovations that should be promoted to increase market access and reduce market risk. Capacity building efforts should be encouraged to enhance producer knowledge on good agronomic practices. Financing peanut production will incentivize farmers to increase their peanut production which will increase supply to the market.

Processor: Improved storage facilities, such as those with controlled temperature and humidity, can extend the shelf life of peanuts. This ensures a steady supply of raw materials for processors, even during off-harvest seasons. Proper storage minimizes post-harvest losses due to pests, mould, and spoilage. With less wastage, more peanuts are available for processing, leading to higher production levels. Further, better storage facilities help maintain the quality of peanuts, preserving their nutritional content and flavour. High-quality raw materials lead to better end products, enhancing marketability and consumer satisfaction. With the ability to store peanuts longer, processors can stabilize supply, reducing the impact of price fluctuations and ensuring a continuous production process. The processing also assists in product diversity such as peanut butter, peanut milk, roasted peanut and many other products which enhances value addition attracting good prices.

Consumer: Educate consumers about the nutritional benefits of peanuts, such as being a good source of protein, healthy fats, and essential nutrients. Further, consumers should be trained on new usage ideas for peanut products, showing their versatility in cooking and baking. Ensuring that peanut products meet high quality and safety standards to build consumer trust and loyalty. Innovate and introduce new peanut-based products such as flavoured peanuts, peanut snacks, peanut milk, and health supplements. At the same time peanut producer should encourage partnership with other food brands, restaurants, and chefs to create unique products and dishes featuring peanuts.

Trader: Boosting opportunities for traders in the peanut value chain involves enhancing market access, supply chain efficiency, financial support, and capacity building. Key strategies include providing real-time market information through digital platforms, improving logistics and storage facilities, and offering affordable credit and trade financing options. Strengthening trader networks and providing training in business management and quality standards are also crucial. Expanding market opportunities through export facilitation and e-commerce platforms, along with supportive policies and risk management tools, can further enhance profitability and reduce risks. These measures empower traders to operate more effectively and capitalize on new opportunities within the peanut value chain.

Research support: Research support in the peanut value chain is critical for enhancing productivity, sustainability, and competitiveness. It includes agricultural research to improve peanut varieties and farming practices, technological development for better equipment and processing methods, and market analysis to understand consumer trends and identify new opportunities. Policy studies help create a supportive regulatory environment, while sustainability research focuses on environmentally friendly practices and climate resilience. Socio-economic research addresses the well-being of farmers and workers, ensuring inclusive growth within the industry. Together, these research efforts drive innovation and strengthen the peanut value chain.

Government policy and programs: The Kenyan government supports the peanut value chain through various policies and programs aimed at enhancing production, processing, and marketing. Key initiatives include providing agricultural support through extension services, subsidies, and financial assistance to boost productivity. The government invests in infrastructure development, such as rural roads and storage facilities, to reduce post-harvest losses and improve market access. Quality control is enforced through standards for aflatoxin levels, and research and development are funded to improve peanut varieties and processing technologies. Additionally, the government promotes capacity building, the formation of cooperatives, and the inclusion of peanuts in food security and nutrition programs, ensuring that the peanut industry contributes to economic growth and rural development.

5. Conclusion

Based on the findings, the input suppliers, peanut growers, distributors (assemblers, wholesalers, and retailers), processors, and sellers of processed products are the primary participants in the peanut value chain. Governmental entities, non-governmental organisations, banks and non-bank financial institutions, as well as local money lenders, are among the other actors who are not direct value chain actors but provide support services to the value chain.

Producers

Enhancing production is the foundation of a successful peanut value chain. This involves improving agricultural practices through research and development to develop high-yielding, disease-resistant peanut varieties. Providing farmers with access to improved seeds, fertilizers, and pest control methods is essential. Training programs and extension services help farmers adopt best practices and innovative techniques, which can increase productivity and resilience against climate change. Investments in irrigation and sustainable farming practices also play a crucial role in maintaining soil health and ensuring consistent yields.

Traders’ node

Traders bridge the gap between producers and processors or consumers. Their role involves buying peanuts from farmers and selling them to processors or directly to consumers. Enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of traders includes improving their access to market information, financial services, and fair-trade practices. Supporting traders through better access to credit and reducing bureaucratic hurdles in trade regulations can facilitate smoother transactions and reduce costs. Strengthening trader networks and cooperatives can also enhance their bargaining power and market reach.

Distributors node

Distributors ensure that peanuts and peanut products reach various markets efficiently. Investments in transportation infrastructure, such as roads and storage facilities, are critical for reducing post-harvest losses and ensuring timely delivery. Improving logistics and supply chain management can help distributors handle large volumes of peanuts and maintain product quality during transit. Efficient distribution networks are essential for expanding market access and ensuring that peanuts are available in both urban and rural areas.

Processors node

Processors add value to peanuts by converting them into various products, such as peanut butter, oil, and snacks. Developing and upgrading processing facilities is crucial for increasing the range and quality of peanut products. Investment in modern technology and adherence to quality standards can enhance the competitiveness of Kenyan peanut products in domestic and international markets. Supporting processors with training and resources to meet international certifications and safety standards will open new market opportunities and improve product appeal.

Consumers

Consumers are the end users of peanut products, and their preferences and demand drive the entire value chain. Increasing consumer awareness about the nutritional benefits of peanuts can boost demand and promote consumption. Marketing and branding strategies can highlight the unique qualities of Kenyan peanuts and attract more consumers. Ensuring that peanut products are readily available through various retail channels and e-commerce platforms can enhance consumer access and convenience. Addressing consumer feedback and preferences can also help tailor products to meet market needs effectively.

5.1. Policy Recommendation for peanut value chain

To strengthen the peanut value chain in Kenya, several key policy recommendations should be considered. First, enhancing agricultural research and development is crucial. Increasing funding for research institutions like KALRO and Universities to develop high-yielding, disease-resistant peanut varieties and sustainable farming practices will address challenges related to climate change and environmental degradation.

Expanding extension services and training programs for farmers, processors, and traders will improve skills in best practices, pest management, and financial management. This is complemented by improving access to finance through affordable credit and tailored insurance products to manage risks such as crop failure and price volatility.

Investing in rural infrastructure, such as roads, storage facilities, and irrigation systems, will reduce post-harvest losses and improve market access. Additionally, developing modern processing facilities will add value to peanuts and create local jobs. Strengthening quality control and enforcing standards will ensure that peanuts meet both domestic and international market requirements, including aflatoxin limits.

Facilitating market access and export opportunities by simplifying trade regulations and supporting compliance with international certifications can enhance the competitiveness of Kenyan peanuts. Supporting the formation of cooperatives and fostering partnerships between farmers, processors, and traders will improve coordination and efficiency within the value chain.

Promoting sustainable practices, such as organic farming and efficient water use, will ensure long-term environmental and economic sustainability. Consumer awareness campaigns and marketing efforts can boost demand for peanuts by highlighting their nutritional benefits and improving product visibility.

Finally, creating incentives for private sector investment in the peanut value chain, through tax breaks or subsidies, and facilitating public-private partnerships will drive innovation and infrastructure development. Implementing these recommendations will strengthen the peanut value chain, enhance productivity, and increase the economic contributions of the peanut industry in Kenya

Funding

This research was funded by the EU H2020 EWA-BELT Project (862848) “Linking East and West African Farming Systems experience into a BELT of sustainable intensification” coordinated by the Desertification Research Centre of the University of Sassari.

Appendix A: Profit and market margins analyses of one tone of peanut transaction at nodes of the value chain

| Peanut |

Production (tons) |

Aggregation (ton) |

Traders (ton) |

Processors (ton) (Butter) |

| Purchase Prices $

|

|

1090 |

1,580.00 |

1,090.00 |

| Production cost $

|

865 |

|

|

|

| Marketing cost $

|

|

|

|

|

| Labor cost $

|

|

5.13 |

5.7 |

307 |

| Transport cost $

|

|

38.46 |

28.49 |

85.47 |

| Value of transport loss $

|

|

3.89 |

3.56 |

34.19 |

| Storage cost $

|

|

35.9 |

7.12 |

34.19 |

| Packaging cost $

|

|

3.63 |

8.55 |

142.45 |

| Market levy $

|

|

9 |

13 |

15.00 |

| Other costs - electricity, water etc $

|

|

|

|

|

| Total Marketing Cost $

|

|

1,186.01 |

1,646.42 |

1,708.30 |

| Sale Prices ($/Kg) |

1.09 |

1.30 |

1.90 |

2.90 |

| Total sales revenue $

|

1,090.00 |

1,300.00 |

1,900.00 |

2,900.00 |

| Gross margin (GM) $

|

225.00 |

113.99 |

253.58 |

1,191.70 |

| Market margin (MM) $

|

0.23 |

0.21 |

0.32 |

1.81 |

| Share of MM (%) |

8.8 |

8.2 |

12.5 |

70.6 |

| Share of GM (%) |

12.6 |

6.4 |

14.2 |

66.8 |

| BCR |

1.3 |

1.1 |

1.2 |

1.7 |

| ROI (%) |

26.0 |

9.6 |

15.4 |

69.8 |

References

- Agriculture and Food Authority (AFA) (2017). https://www.agricultureauthority.go.ke/images/docs/AFA%20Strategic%20Plan-min(1).pdf.

- Biodiversity International (2010). Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture Contributing to food security and sustainability in a changing world. https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/biodiversity_paia/PAR-FAO-book_lr.pdf.

- Centre for Advance Training in Rural Development (SLE) (2006). Poverty orientation of value chains for domestic and export markets in Ghana. series. Berlin: SLE publication.

- Dhunpath R & Samuel M (eds.) 2009. Life history research: epistemology, methodology and representation. SENSE Publishers, Rotterdam, Netherlands.

- EADD. 2009. The dairy value chain in Kenya. Nairobi, Kenya: East Africa Dairy Development Project (EADD). https://hdl.handle.net/10568/2407.

- Eastern Africa, Supply Chain outcomes in the Food System: Evaluation (2022). https://www.wfp.org/publications/eastern-africa-supply-chain-outcomes-food-system-evaluation.

- Ellen Owuso (2017). Analysis of the Groundnut Value Chain in Ghana. 10.12691/wjar-5-3-8.

- FAO. 2019. The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction. Rome. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://www.fao.org/3/ca6030en/ca6030en.pdf.

- FAO/WHO/UNU (2002) Protein and Amino Acid Requirements in Human Nutrition. In: Report of a Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation, World Health Org Tech Report No.935 [PubMed].

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (2021) The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021 .https://www.fao.org/publications/home/fao-flagship-publications/the-state-of-food-security-and-nutrition-in-the-world/en.

- Gerring, J. (2007) Case Study Research: Principles and Practices. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- H. Mwachofi (2016). Value Chain Analysis of the Coconut Sub-Sector in Kenya. http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/bitstream/handle/11295/99356/Mwachofi%20Herman_Value%20Chain%20Analysis%20of%20the%20Coconut%20Sub-sector%20in%20Kenya.pdf?sequence=1.

- Happy Daudi, Hussein Shimelis, Mark Laing, Patrick Okori & Omari Mponda (2018) Groundnut production constraints, farming systems, and farmer-preferred traits in Tanzania, Journal of Crop Improvement, 32:6, 812-828. [CrossRef]

-

https://greenforest.co.ke/greenforest-foods-and-european-union-eu-two-year-partners-to-expand-its-groundnut-production-capacity-by-contracting-2000-farmers-in-2021-2022/.

-

https://nuts.agricultureauthority.go.ke/index.php/perfomance/reports?download=57:nuts-and-oil-statistical-report-2021.

-

https://www.kalro.org/sites/default/files/Rice-Products-Value-Chain-Analysis.pdf.

-

https://www.knbs.or.ke/download/economic-survey-2019/.

- International Fund for Agriculture Development (2009). Enabling poor rural people to overcome poverty in Ghana. Retrieved from http://www.ruralpovertyportal.org.

- Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO) (2021). Situational Analysis of Rice Product Value Chain.

- Kenya Metropolitan Department. https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/kenya/climate-data-historical.

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (2021). Kenya living standards survey round 6 (KNBS 6). Nairobi: KNBS.

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) (2019). Economic Survey.

-

Kouritzin, S. G. (2000). Bringing Life to Research: Life History Research and ESL. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture (2017). National Food and Nutrition Security Policy Implementation Framework. https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/ken170761.pdf.

- Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) (2009). Food and agriculture sector development policy. Nairobi: Ministry of Agriculture.

- Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) (2019). Food and agriculture sector development policy. Nairobi: Ministry of Agriculture.

- Njuki, J., Kaaria, S., Chamunorwa, A., & Chiuri, W. (2011). Linking smallholder farmers to markets, gender and intra-household dynamics: Does the choice of commodity matter? The European Journal of Development Research, 23(3), 426-443. [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E. (1985). The Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. New York: Free Press.

- R.N. Wanyama, P.M. Mshenga, A. Orr, M.E. Christie and F.P. Simtowe (2013). A Gendered Analysis of the Effect of Peanut Value Addition on Household Income in Rongo and Ndhiwa Districts of Kenya. file:///C:/Users/User/Downloads/Rosina%20N.%20Wanyama_%20P.M.%20Mshenga%20et%20al%20(1).pdf.

-

Saunders, M., Lewis, P. and Thornhill, A. (2007) Research Methods for Business Students. 4th Edition, Financial Times Prentice Hall, Edinburgh Gate, Harlow.

- United States Agency for International Development (USAID) (2018). Final Performance Evaluation of The Kenya Agricultural Value Chain Enterprises Activity (KAVES). Final Report. https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00T9H6.pdf.

- W.F.P. (2022). Impact of increasing fertilizer prices on maize production in Kenya. https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000142846/download/.

- Wanyama, M., Mose, L. O., Odendo, M., Okuro, J. O., Owuor, G., & Mohammed, L. (2010). Determinants of income diversification strategies amongst rural households in maize based farming systems of Kenya. African Journal of Food Science, 4(12), 754-763.

- World Bank (2022). National Agricultural Value Chain Development Project (NAVCDP) https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099635002202225605/project0inform0navcdp0000p17675801.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).