1. Introduction

Endometrial cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women in the United States. The estimated number of new endometrial carcinoma cases in women in the United States in 2023 was 66.200 (7%) with 13.030 (5%) deaths. The incidence rate has been rising with aging and change of lifestyle due to an increase percentage of the obesity in women’s population [

1]. Histologically, endometrial carcinoma begins from the lining of the uterus. It has been broadly classified into two clinicopathogenetic subgroups in 1983 by Bokhman [

2]. Type I, including the endometrioid tumors, which represent the majority of uterine tumors, and are estrogen driven with lower grade, less myometrial invasion, and a more favorable prognosis compared with type II, which are histologically and clinically more advanced with higher grade and poor prognosis. Although, the majority of women with endometrial carcinoma have good prognosis due to their detection in early stages, the disease-free survival rate of high-grade tumors may be as low as 13% after adjuvant chemotherapy [

3]. Thus, it is important to identify prognostic factors for the adequate therapy of endometrial carcinoma.

The clinicopathological prognostic factors have low reproducibility between expert pathologists, even with the use of immunohistochemistry. In 2020 the new WHO classification tried to avoid discrepancies by using morphological, immunohistochemical and molecular diagnostic features [

4]. This situation results in over-treatment and under-treatment of thousands of cases between cancer centers globally [

5,

6,

7]. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network, in 2013, settled a molecular classification of endometrial cancer to anticipate the prognosis and the correct therapy [

8]. The four genomic subgroups, based on a combination of mutation and protein expression analyses, are DNA polymerase epsilon (POLE) mutated subtype, mismatch repair-deficient subtype (MMRd, MSI), no specific molecular profile (NSMP) and p53 abnormal (p53 mutation type) [

9]. These four subgroups have precipitated to create this new molecular classification, together with the old classification, in the new ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the exceptional management of endometrial cancer patients [

10].

All these data empower the prognostic significance of the molecular classification with the clinicopathological factors to change the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system for endometrial cancer. The new 2023 FIGO staging system [

11] of endometrial cancer is more complicated than that of 2009 [

12]. Although, the cornerstone of the staging of any cancer is the anatomic involvement, new elements are integrated in the new 2023 FIGO with histologic grade, histology, lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) and molecular classification. So, this produces a noticeable divergence of the staging of FIGO 2009. The aim of this study is to investigate the stage shifts between the two staging systems and to evaluate the clinical and prognostic impact of the new 2023 FIGO staging system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Characteristics

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of all women with newly diagnosed endometrial cancer, who were treated in the 1st Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, AUTh, “Papageorgiou” General Hospital, from January 1, 2012 until December 31, 2023 and identified those that received their complete treatment at our hospital. 476 patients were diagnosed with endometrial cancer during this period of time. A written approval was received from the Institutional Review Board of the hospital.

2.2. Patients

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

As a result of the above-mentioned criteria, 30 out of the 476 women with endometrial cancer were excluded due to synchronous neoplasms or as a recurrence of endometrial cancer. Moreover, 16 women were excluded, because they were missing important registry data and could not be further statistically analyzed. Hence, finally 431 women with endometrial cancer were identified as eligible for further analysis, with no duplicate data and important missing values.

All patients underwent a complete laboratory and imaging staging for endometrial cancer and after an MDT board meeting were operated based on the presumed stage of the disease. In early stages, minimal invasive surgery was performed in the majority of the cases, while some underwent laparotomy. Total hysterectomy with or without bilateral salpingo-oophecetomy and omentectomy, in specific histological types, were offered. Lymph node staging was performed with sentinel lymph node biopsy and in some cases with pelvic and/or paraaortic lymph node dissection. In advanced stages, a cytoreductive surgery was performed. Adjuvant treatment was decided after the MDT board meeting according to the international guidelines [

10]. Close follow-up of the patients included clinical examination, laboratory and imaging exams.

2.3. Data Collection

Data was collected during a period of one month. Our Gynecological – Oncology Unit has an online registry with all the relevant data of the patient’s medical records. In order to avoid inconsistencies among different dates of data collection, a uniform data collection sheet (excel file) was used, during the retrospective mining of the patient’s medical records. The data sheet included the following information:

-

Patient’s identifiers:

- ○

Name

- ○

Hospital identification number

Patient’s age

Body Mass Index (BMI)

Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)

Histological type

Lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI)

Tumor grade

FIGO Staging (2009)

FIGO Staging (2023)

-

Molecular classification:

- ○

DNA polymerase epsilon (POLE) mutation

- ○

Mismatch repair-deficient subtype or microsatellite instability (MMRd or MSI)

- ○

p53 abnormal (mutation type)

-

Time related data:

- ○

Date of diagnosis

- ○

Date of recurrence

- ○

Date of last follow-up or death

LVSI was defined as no, focal and substantial according to the latest WHO classification. Focal was defined as the presence of a single focus around the tumor and substantial as multifocal or diffuse arrangement or the presence of tumor cells in five or more lymphovascular spaces [

13]. Furthermore, tumor grade was categorized with the binary system as low or high [

14] and all patients were classified firstly by the 2009 FIGO staging system [

15] and then by the 2023 [

16]. The two FIGO staging systems are presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2. All stage shifts were documented: Upstaging was considered a reclassification to a higher group and downstaging to a lower group.

Molecular testing for the integration of the new classification was performed. POLE sequencing with NGS to test 11 POLE exonuclease domain hotspots for mutations: DNA was isolated from the sample under examination Mutational analysis of the region of the POLE gene (exons 9-14) was performed. Sequencing was done using the Ion Gene Studio S5 Prime System Next Generation Sequencing platform (Thermo Fisher Scientific). MSI assay to test for microsatellite instability: Genomic DNA was isolated from the paraffin-embedded tumor tissue sample. This was followed by analysis of 76 markers by next-generation sequencing to assess Microsatellite Instability (MSI) status using Ion Ampliseq technology. Sequencing was performed using the Ion Gene S5 Prime System next-generation sequencing platform (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The test provides results for individual microsatellites and produces an MSI score for the sample. A sample is considered positive for MSI if the microsatellite instability score is greater than 30. p53 immunohistochemistry testing to identify the 4 distinct mutant-expression patterns: There are four distinct p53 mutant- expression patterns: diffuse and strong nuclear positivity, complete absence of expression, overexpression in the cytoplasm and a well-delimited area of the tumor with mutant expression of p53 in a background of wild-type expression. In cases of multiple classifiers, meaning the presence of more than one molecular feature, the more favorable prognostic group was retained [

17].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using RStudio. For descriptive statistics of qualitative variables, the frequency distribution procedure was run with calculation of the number of cases and percentages. On the other hand, for descriptive statistics of quantitative variables, the mean, median, range, and standard deviation were used to describe central tendency and dispersion. Progression-free (DFS) and overall survival (OS) analyses were performed using the Kaplan – Meier curves. 5-year PFS and OS survival were assessed per cancer stage between the 2009 and 2023 FIGO Staging systems. Progression-free survival was defined as the time interval between date of diagnosis and date of first recurrence or disease progression, while overall survival as the time interval from diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up. To evaluate the prognostic precision of each FIGO staging system, Cox proportional hazard models between the 2 FIGO staging systems were used. The Akaike information criterion (AIC), the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and Harrel’s concordance index (C-index) were calculated for each model. The Likelihood ratio test was performed in order to test whether using the 2023 FIGO staging system as a predictor provided a better model fit. A p-value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

This retrospective cohort study included 476 women, who were treated during the period of the study for endometrial cancer in the Gynecological – Oncology Unit, 1st Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, “Papageorgiou” General Hospital. After screening the patients based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 431 patients were eligible for further analysis in this study.

Patients’ characteristics are outlined in

Table 3. The mean age of the women at the time of the diagnosis was 63.5 years old, while the mean BMI was 32.8 kg/m

2, meaning that most women were obese. Furthermore, concerning the performance status of our patients, almost half of them (47%) had moderate comorbidities, which was measured by the Charlson Comorbidities Index (CCI). These results are in accordance with the phenotype of the disease. Concerning, histology the majority of the patients had low grade endometrioid neoplasms with no lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI). Unfortunately, only a fraction of our patients (7.7%) was fully tested for the new molecular classification.

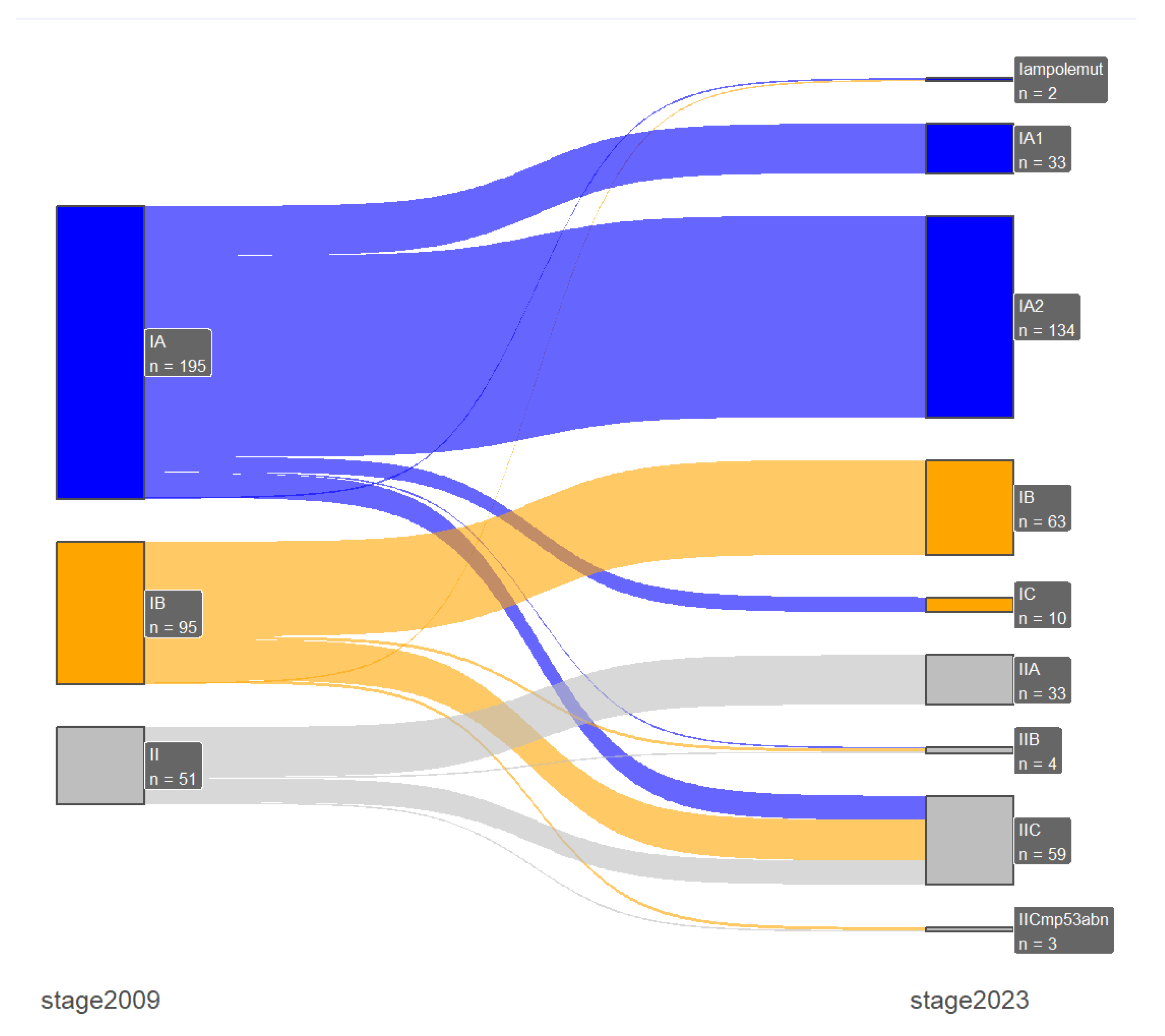

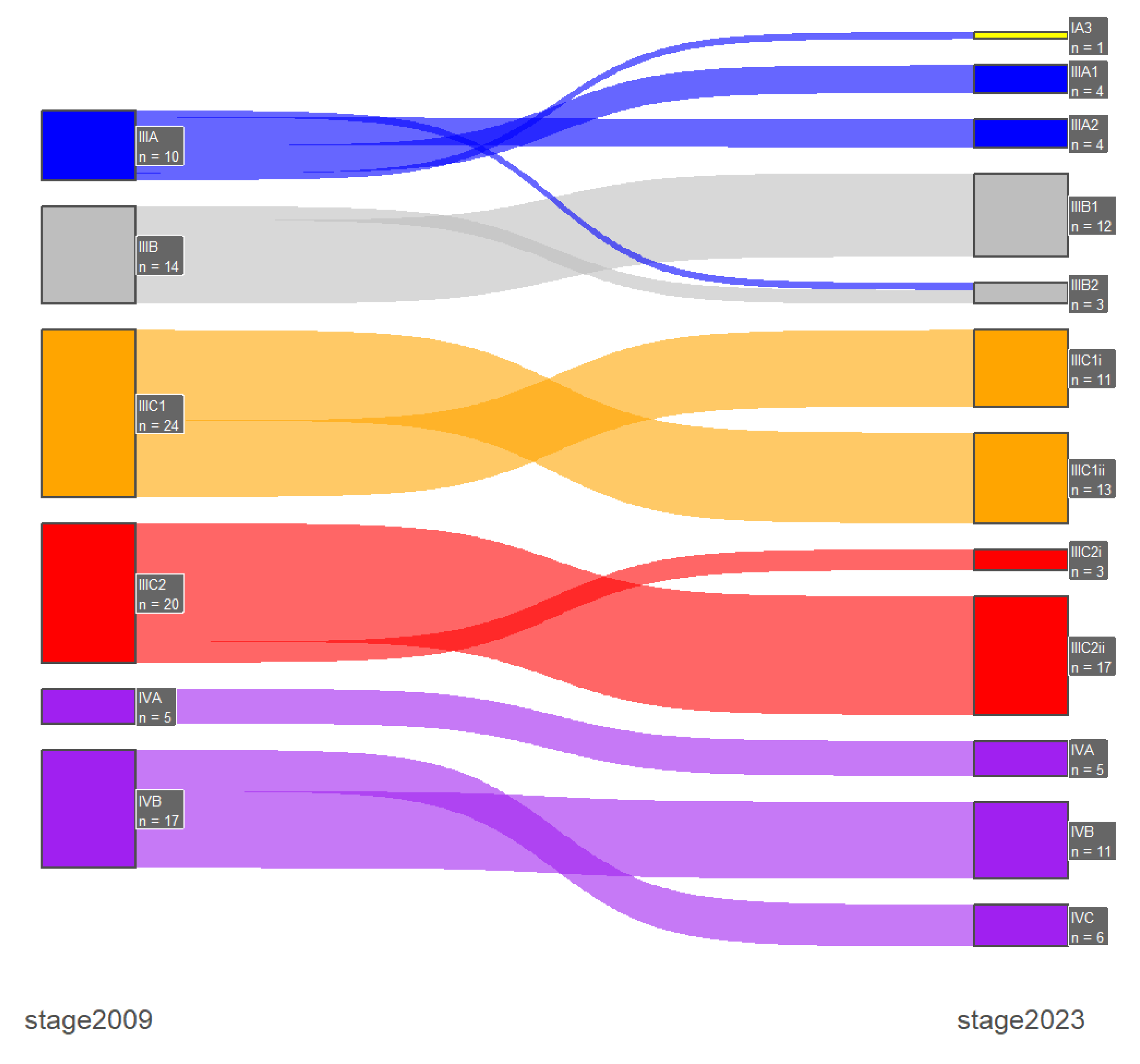

Stage shifts between the two FIGO staging systems, which was one of the primary endpoints of our study, was present in 67 patients (15.5%). Specifically, there were 2 (0.5%) downshifts and 65 (15%) upshifts, with most of them occurring only between early-stage or advanced-stage disease and only one case of downshifts from advanced- to early-stage disease. In early-stage disease (FIGO stage I/II) the majority of the upshifts were from 2009 FIGO stage IA (n=16) and IB (n=27) to the new 2023 FIGO stage IIC substage and with the incorporation of the molecular profile there were 3 stage shifts from the 2009 FIGO stage IB: 1 downshift to IAm

polemut and 2 upshifts to IICm

p53abn. Furthermore, in advanced-stage disease (FIGO stage III/IV) the majority of the upshifts were from 2009 FIGO stage IVB (n=6) to 2023 FIGO stage IVC. These results are presented in

Table 4 and in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

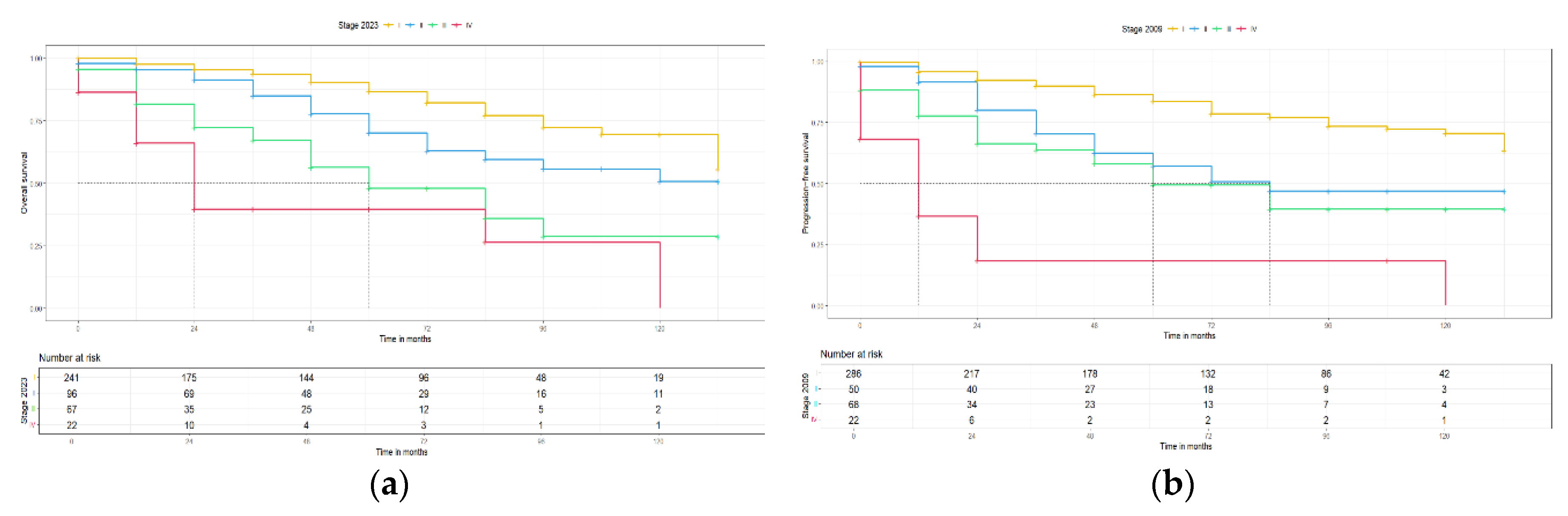

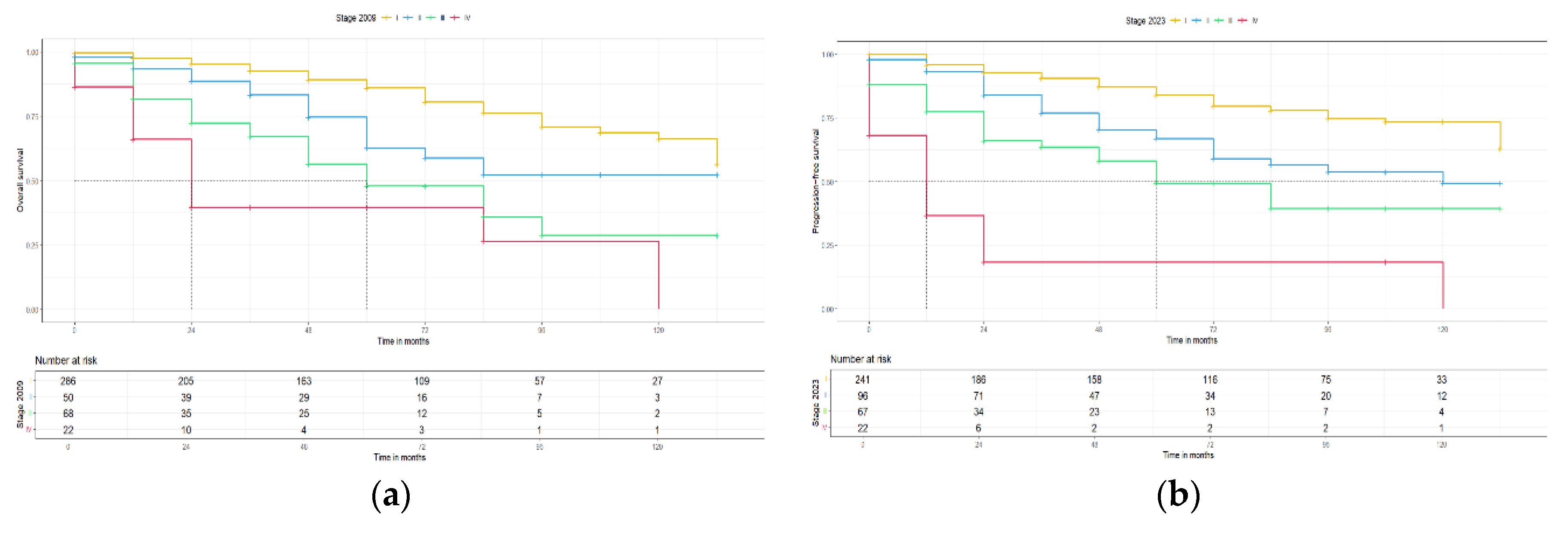

Moreover, the second primary endpoint of this study was the clinical and prognostic impact of the new 2023 FIGO staging system. For this reason, the 5-year progression free survival (PFS) and the 5-year overall survival (OS) for the 2009 and 2023 FIGO staging systems were calculated and Kaplan-Meier curves for PFS and OS were constructed, respectively. The median follow-up of this cohort was 48 months with an IQR: 12 – 72, which is long enough to provide reliable survival results. For stage I disease, the 5-year PFS and 5-year OS were slightly better for the 2023 FIGO staging system [83.3 (78.8, 88.4) to 84 (78.9, 89.5) and 86 (81.2, 91.2) to 86.6 (81.5, 92.1), with an interval rate change of +0.7% and +0.6%, respectively] compared to the 2009 FIGO staging system, but the median PFS and OS were for both staging systems >145 months. For stage II disease, a notably higher 5-year PFS and 5-year OS for the 2023 FIGO staging system [

57.2 (43.8, 74.6) to

66.9 (56.7, 79.0) and

62.8 (48.9, 80.7) to

70.2 (59.6, 82.8), with an interval rate change of +9.7% and +7.4%, respectively] compared to the 2009 FIGO staging system. Concerning survival rates, a significant higher median PFS (p < 0.05) was observed in the 2023 FIGO staging system (2009: 84 vs. 2023: 120 months), but with no differences in the OS (>145 months for both). For advanced stage disease, similar 5-year PFS and 5-year OS were found between the two FIGO staging systems (for sub-stages of stage III and stage IV no statistical analysis was possible due to the low case numbers) and no difference in the median PFS and OS, respectively. These results are summarized in

Table 5 and

Figure 3 and

Figure 4.

In addition, we further analyzed the group of patients with the majority of stage shifts between the two staging systems. Specifically, 48 patients were upshifted from 2009 FIGO stage I to the 2023 FIGO stage II. The main reason for these upshifts was sub-stage IIC, which includes all aggressive histological subtypes with any myometrial invasion: high-grade endometrioid, serous, clear cell, undifferentiated, mixed, mesonephric-like, gastrointestinal mucinous type carcinomas, and carcinosarcomas. Based on the histopathological features half (n=24, 50%) of this group of patients had endometrioid tumors, while only 7 (14.6%) patients had low grade tumors and only 5 (10.4%) substantial LVSI. The aforementioned data are presented in

Table 6. Looking into the survival rates of this group of patients: 5-year DFS was 76.4 (62, 94) and 5-year OS was 81.9 (68.3, 98.2) months.

Figure 3.

PFS for 2009 and 2023 FIGO staging systems (no molecular classification).

Figure 3.

PFS for 2009 and 2023 FIGO staging systems (no molecular classification).

Figure 4.

OS for 2009 and 2023 FIGO staging systems (no molecular classification).

Figure 4.

OS for 2009 and 2023 FIGO staging systems (no molecular classification).

The AIC, BIC, C-index and likelihood-ratio test were all used to compare the prognostic precision of the two FIGO staging systems. The AIC scores to predict PFS for the 2023 FIGO staging system compared to the 2009 FIGO staging system were 1260.42 and 1256.31, respectively. Furthermore, the BIC scores to predict PFS for the 2023 and 2009 FIGO staging systems were 1274.35 and 1264.67, respectively. The C-index for both FIGO staging systems were 0.71 and 0.70, respectively for PFS. The likelihood ratio comparing the two models showed that there is not statistically significant difference (p= 0.95). On the other hand, for the OS between the 2023 FIGO staging system compared to the 2009 FIGO staging system: the AIC scores were 1047.26 and 1043.5, respectively, the BIC scores were 1060.44 and 1051.48, respectively and the C-index was 0.71 for each model. The likelihood-ratio test comparing the two models also did show any significant difference (p = 0.86).

4. Discussion

The primary objective of our study was to investigate the stage shifts between the new 2023 FIGO staging system compared to the old 2009 and to assess its clinical and prognostic impact. We designed a retrospective study of endometrial cancer patients that were accurately stages with the 2009 FIGO staging system and re-staged them according to the new 2023 system, including the molecular classification when it was available.

This study included 431 patients with endometrial cancer, which were all included in the final analyses, but full molecular testing and therefore the implementation of the new molecular classification was possible in a fraction of our cohort (7.7%). Our cohort has a long follow-up period with a median of 48 months and no important histological data were missing from any patient. Stage shifts were present in 15.5% of the patients and the majority of them concerned early-stage disease. Specifically, stage I patients in the new 2023 FIGO staging system decreased in numbers, while stage II increased. This was mainly due to the new IIC substage which includes all aggressive histological subtypes with any myometrial invasion, so many previously 2009 staged IA and IB 2009 were upshifted. These patients also demonstrated a worse 5-year PFS and 5-year OS compared to patients in stage IA & IB (PFS: 60.2 vs. 86.7 & 76.2 and OS: 75.4 vs. 88.9 & 81). In advanced-stage disease, most of the cases were upshifts from the 2009 IVB stage to the new 2023 IVC stage. However, due to the low number of patients in these sub-stages, no robust statistical analysis was possible. Moreover, the prognostic precision of the 2023 FIGO staging system was tested with several statistical test (AIC, BIC, C-index, likelihood-test) and no difference was found between the two staging systems.

To our knowledge, there are only a few studies in the literature that compared the two FIGO staging systems. The first study [

18] was from three large ESGO accredited centers in Europe, which included 519 patients and the majority of them underwent molecular testing. Their results are in accordance with ours, since most of the stage shifts concerned early-stage disease and specifically upshifts to the new sub-stage IIC. However, our results differ in the 5-year PFS and 5-year OS of the new 2023 FIGO staging system and its prognostic impact, because the authors found a superior prognostic precision form the old 2009 FIGO staging system. However, in the survival analyses only 232 patients were included from two of the three centers, in order to achieve an acceptable long enough follow-up period. Furthermore, the second study [

19] is a single-center small retrospective cohort of 161 patients from Korea, where all patients underwent molecular classification. However, the authors state that POLE mutation was not tested with NGS, which is the proposed way form the ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines, to avoid missing any hotspots. The results are similar to ours concerning the stage shifts in early-stage disease.

Last but not least, the latest study [

20] is from the USA and included over 100000 patients with endometrial cancer from the National Cancer Database (NCB). Their results are in accordance with ours for early-stage disease stage shifts and they also provide data about advanced stage disease. However, these results, as stated also by the authors, should be interpreted with caution, because none of the patients included underwent molecular testing and there was no accurate data about LVSI, which is a key element of the new 2023 FIGO staging system.

Our study was conducted in a university, tertiary ESGO certified center. All the required parameters were collected from an online system, therefore minimizing the percentage of missing important data and all stage shifts were double checked from the two leading authors. Furthermore, our study has the longest median follow-up period and the highest population in the final analysis. In contrast, the main limitation of our study is the low number of molecular testing and its retrospective nature. Many experts have expressed their reservations in the new 2023 FIGO staging system [

21] and especially in incorporation of the molecular classification. This leads to bias towards recourse-rich centers and/or countries, especially for the

POLE mutational test, due to its cost and high variability in the testing method that was used. The main point, in accelerating the introduction of molecular testing in every day clinical practice, is first to determine which is the best and more accurate test and then lower the cost, in order to be applicable worldwide.

Future large and carefully designed studies are needed in order to fully understand the implications of the molecular classification in the new 2023 FIGO staging system.

5. Conclusions

The new 2023 FIGO staging system better distinguishes early-stage endometrial cancer into its prognostic groups and seems to be as precise as the old 2009 FIGO staging system. Patients should be encouraged to undergo molecular testing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.Z. and D.T.; methodology, P.T.; software, D.Z.; validation, M.T., E.T. and D.T.; formal analysis, I.S.; investigation, T.K.., I.S.; resources, D.T., V.T.; data curation, D.Z., K.C.; writing—original draft preparation, D.Z., I.S.; writing—review and editing, D.T.; visualization, G.G.; supervision, D.T., E.T., G.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board) of PAPAGEORGIOU General Hospital (Νο. 7244/06/03/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to fact that this was retrospective study and no change in the treatment of the patients was made.

Data Availability Statement

In accordance with the journal’s guidelines, the data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author for the reproducibility of this study if such is requested.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin 2023;73:17–48. [CrossRef]

- Bokhman J V. Two pathogenetic types of endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 1983;15:10–7. [CrossRef]

- Talhouk A, McConechy MK, Leung S, Li-Chang HH, Kwon JS, Melnyk N, et al. A clinically applicable molecular-based classification for endometrial cancers. Br J Cancer 2015;113:299–310. [CrossRef]

- Masood M, Singh N. Endometrial carcinoma: changes to classification (WHO 2020). Diagnostic Histopathol 2021;27:493–9. [CrossRef]

- Guan H, Semaan A, Bandyopadhyay S, Arabi H, Feng J, Fathallah L, et al. Prognosis and reproducibility of new and existing binary grading systems for endometrial carcinoma compared to FIGO grading in hysterectomy specimens. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2011;21:654–60. [CrossRef]

- Han G, Sidhu D, Duggan MA, Arseneau J, Cesari M, Clement PB, et al. Reproducibility of histological cell type in high-grade endometrial carcinoma. Mod Pathol 2013;26:1594–604. [CrossRef]

- Gilks CB, Oliva E, Soslow RA. Poor interobserver reproducibility in the diagnosis of high-grade endometrial carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2013;37:874–81. [CrossRef]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network K, Kandoth C, Schultz N, Cherniack AD, Akbani R, Liu Y, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature 2013;497:67–73. [CrossRef]

- Talhouk A, McConechy MK, Leung S, Yang W, Lum A, Senz J, et al. Confirmation of ProMisE: A simple, genomics-based clinical classifier for endometrial cancer. Cancer 2017;123:802–13. [CrossRef]

- Concin N, Matias-Guiu X, Vergote I, Cibula D, Mirza MR, Marnitz S, et al. ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the management of patients with endometrial carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2021;31:12–39. [CrossRef]

- Berek JS, Matias-Guiu X, Creutzberg C, Fotopoulou C, Gaffney D, Kehoe S, et al. FIGO staging of endometrial cancer: 2023. J Gynecol Oncol 2023;34:e85. [CrossRef]

- Pecorelli S. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009;105:103–4. [CrossRef]

- Höhn AK, Brambs CE, Hiller GGR, May D, Schmoeckel E, Horn L-C. 2020 WHO Classification of Female Genital Tumors. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 2021;81:1145–53. [CrossRef]

- Sagae S, Saito T, Satoh M, Ikeda T, Kimura S, Mori M, et al. The reproducibility of a binary tumor grading system for uterine endometrial endometrioid carcinoma, compared with FIGO system and nuclear grading. Oncology 2004;67:344–50. [CrossRef]

- Pecorelli S. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009;105:103–4. [CrossRef]

- Berek JS, Matias-Guiu X, Creutzberg C, Fotopoulou C, Gaffney D, Kehoe S, et al. FIGO staging of endometrial cancer: 2023. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2023;162:383–94. [CrossRef]

- León-Castillo A, Gilvazquez E, Nout R, Smit VT, McAlpine JN, McConechy M, et al. Clinicopathological and molecular characterisation of “multiple-classifier” endometrial carcinomas. J Pathol 2020;250:312–22. [CrossRef]

- Schwameis R, Fanfani F, Ebner C, Zimmermann N, Peters I, Nero C, et al. Verification of the prognostic precision of the new 2023 FIGO staging system in endometrial cancer patients - An international pooled analysis of three ESGO accredited centres. Eur J Cancer 2023;193:113317. [CrossRef]

- Han KH, Park N, Lee M, Lee C, Kim H. The new 2023 FIGO staging system for endometrial cancer: what is different from the previous 2009 FIGO staging system? J Gynecol Oncol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gravbrot N, Weil CR, DeCesaris CM, Gaffney DK, Suneja G, Burt LM. Differentiation of survival outcomes by anatomic involvement and histology with the revised 2023 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging system for endometrial cancer. Eur J Cancer 2024;201:113913. [CrossRef]

- Leitao MM. 2023 changes to FIGO endometrial cancer staging: Counterpoint. Gynecol Oncol 2024;184:146–9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).