Submitted:

23 August 2024

Posted:

24 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Participants and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Participants, and Outcome Measures

2.2. Biomarker Quantification

2.3. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study Participant Characteristics at Entry

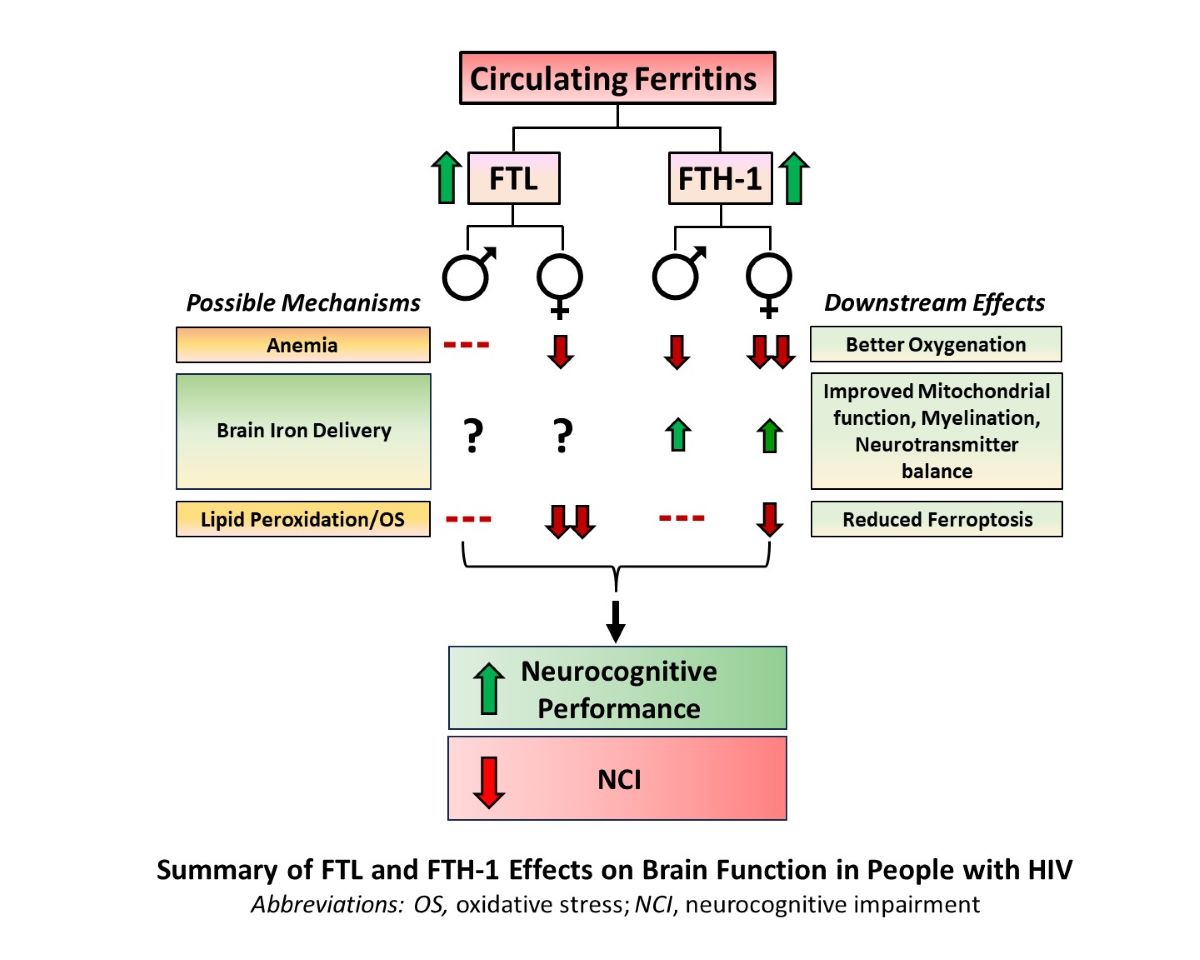

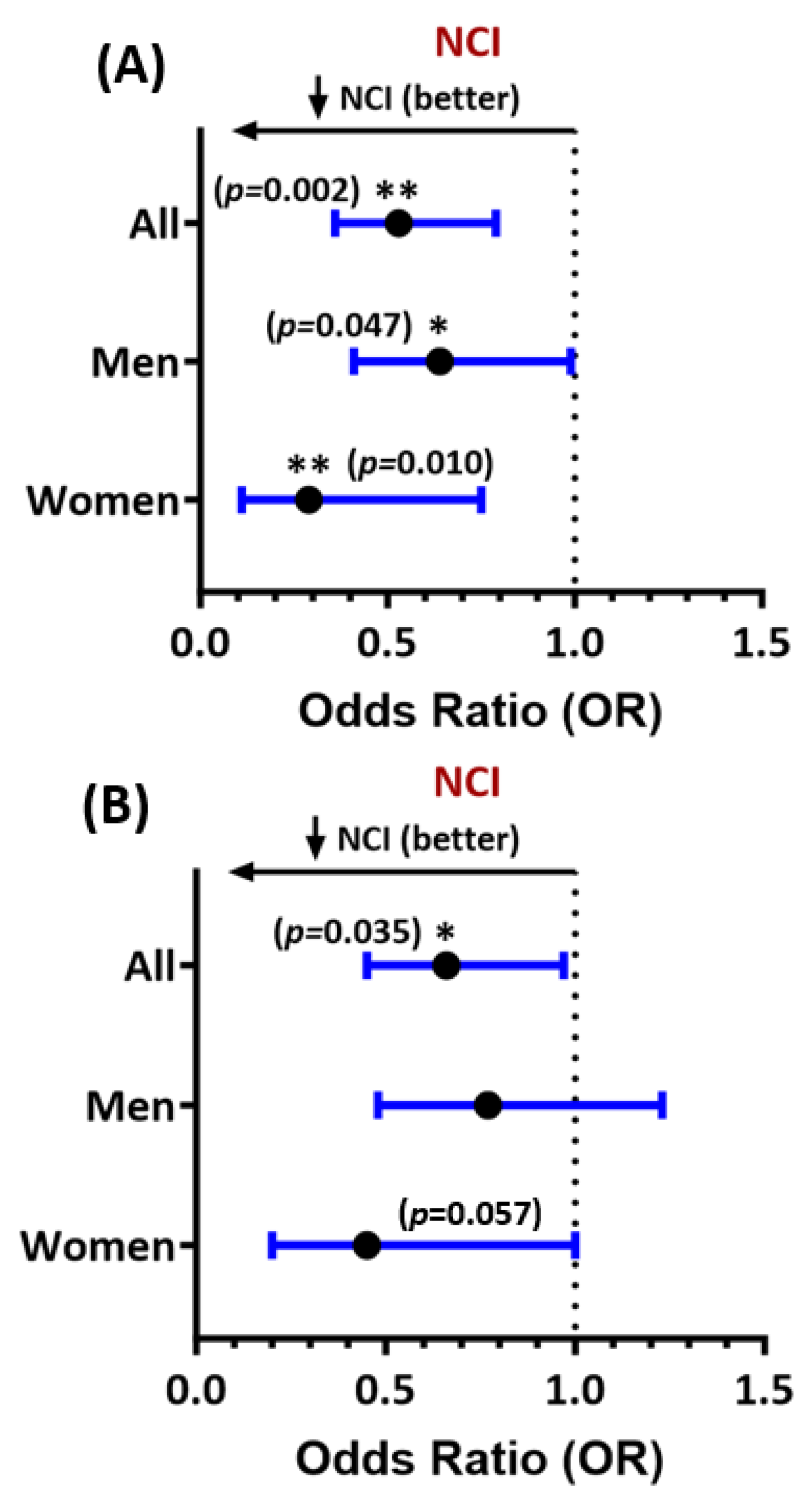

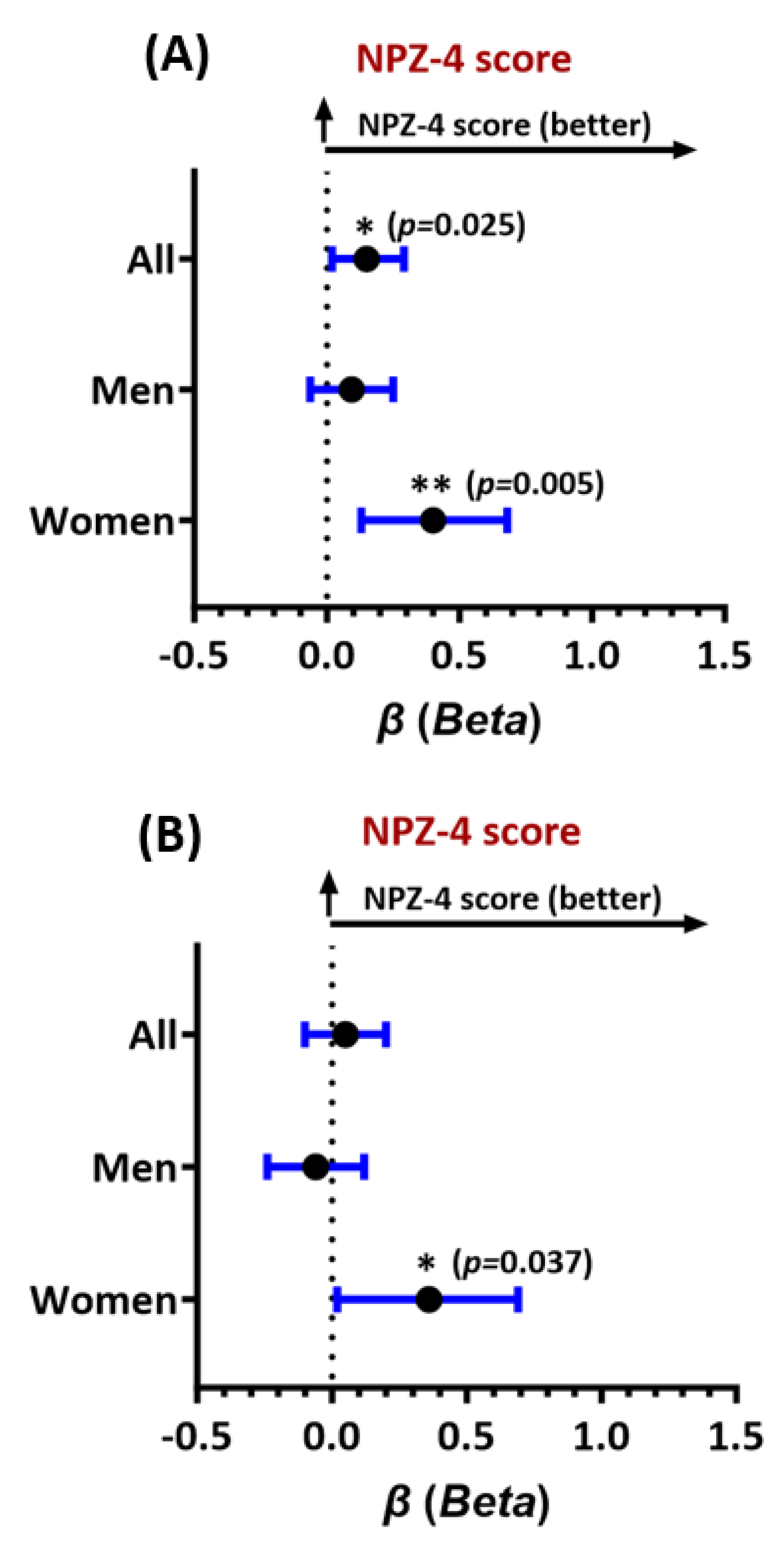

3.2. Multivariable Ferritin Associations with Global NCI and Neurocognitive Performance, and Interaction Effects by Sex

3.3. Ftl and Fth-1 Associations with Neurocognitive Domain Test Scores

3.4. Ftl and Fth-1 Associations with Longitudinal Neurocognitive Performance

3.5. Ferritin Associations with Inflammation, Lipid Peroxidation, and Anemia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scanlan, A.; Zhang, Z.; Koneru, R.; Reece, M.; Gavegnano, C.; Anderson, A.M.; Tyor, W. A Rationale and Approach to the Development of Specific Treatments for HIV Associated Neurocognitive Impairment. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saloner, R.; Fields, J.A.; Marcondes, M.C.G.; Iudicello, J.E.; von Känel, S.; Cherner, M.; Letendre, S.L.; Kaul, M.; Grant, I.; Translational Methamphetamine AIDS Research Center (TMARC) Group. Methamphetamine and Cannabis: A Tale of Two Drugs and their Effects on HIV, Brain, and Behavior. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2020, 15, 743–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, S.; Dreyer, A.J.; Saylor, D.; Gisslén, M.; Winston, A.; Joska, J.A. Moving on From HAND: Why We Need New Criteria for Cognitive Impairment in Persons Living With Human Immunodeficiency Virus and a Proposed Way Forward. Clin Infect Dis 2021, 73, 1113–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoenigl, M.; de Oliveira, M.F.; Pérez-Santiago, J.; Zhang, Y.; Morris, S.; McCutchan, A.J.; Finkelman, M.; Marcotte, T.D.; Ellis, R.J.; Gianella, S. (1→3)-β-D-Glucan Levels Correlate With Neurocognitive Functioning in HIV-Infected Persons on Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy: A Cohort Study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016, 95, e3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hileman, C.O.; Kalayjian, R.C.; Azzam, S.; Schlatzer, D.; Wu, K.; Tassiopoulos, K.; Bedimo, R.; Ellis, R.J.; Erlandson, K.M.; Kallianpur, A.; Koletar, S.L.; Landay, A.L.; Palella, F.J.; Taiwo, B.; Pallaki, M.; Hoppel, C.L. Plasma Citrate and Succinate Are Associated With Neurocognitive Impairment in Older People With HIV. Clin Infect Dis 2021, 73, e765–e772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Chen, X.; Kang, R.; Kroemer, G. Ferroptosis: molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell Res 2021, 31, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, S.; Alhazmi, H.A.; Hassani, R.; Khuwaja, G.; Maheshkumar, V.P.; Aldahish, A.; Chidambaram, K. Role of ferroptosis pathways in neuroinflammation and neurological disorders: From pathogenesis to treatment. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, S.M.; Wang, Q.; Hulgan, T.; Connor, J.R.; Jia, P.; Zhao, Z.; Letendre, S.L.; Ellis, R.J.; Bush, W.S.; Samuels, D.C.; Franklin, D.R.; Kaur, H.; Iudicello, J.; Grant, I.; Kallianpur, A.R. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers of iron status are associated with CSF viral load, antiretroviral therapy, and demographic factors in HIV-infected adults. Fluids Barriers CNS 2017, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, B.; Connor, J.R. Emerging and Dynamic Biomedical Uses of Ferritin. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2018, 11, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Bush, W.S.; Letendre, S.L.; Ellis, R.J.; Heaton, R.K.; Patton, S.M.; Connor, J.R.; Samuels, D.C.; Franklin, D.R.; Hulgan, T.; Kallianpur, A.R. Higher CSF Ferritin Heavy-Chain (Fth1) and Transferrin Predict Better Neurocognitive Performance in People with HIV. Mol Neurobiol 2021, 58, 4842–4855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.K.; Arosio, P.; Poli, M.; Bou-Abdallah, F. A Novel Approach for the Synthesis of Human Heteropolymer Ferritins of Different H to L Subunit Ratios. J Mol Biol 2021, 433, 167198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qiu, S.; Wang, H.; Cui, J.; Tian, X.; Miao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Cao, L.; Ma, L.; Xu, X.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, X. Transcriptional Repression of Ferritin Light Chain Increases Ferroptosis Sensitivity in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 719187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Lu, J.; Hao, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, G.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, C.; Kuang, W.; Chen, D.; Zhu, M. FTH1 Inhibits Ferroptosis Through Ferritinophagy in the 6-OHDA Model of Parkinson's Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2020, 17, 1796–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arosio, P.; Carmona, F.; Gozzelino, R.; Maccarinelli, F.; Poli, M. The importance of eukaryotic ferritins in iron handling and cytoprotection. Biochem J 2015, 472, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensio-Lopez, M.C.; Sanchez-Mas, J.; Pascual-Figal, D.A.; de Torre, C.; Valdes, M.; Lax, A. Ferritin heavy chain as main mediator of preventive effect of metformin against mitochondrial damage induced by doxorubicin in cardiomyocytes. Free Radic Biol Med 2014, 67, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiou, B.; Lucassen, E.; Sather, M.; Kallianpur, A.; Connor, J. Semaphorin4A and H-ferritin utilize Tim-1 on human oligodendrocytes: A novel neuro-immune axis. Glia 2018, 66, 1317–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palsa, K.; Neely, E.B.; Baringer, S.L.; Helmuth, T.B.; Simpson, I.A.; Connor, J.R. Brain iron acquisition depends on age and sex in iron-deficient mice. FASEB J 2024, 38, e23331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baringer, S.L.; Neely, E.B.; Palsa, K.; Simpson, I.A.; Connor, J.R. Regulation of brain iron uptake by apo- and holo-transferrin is dependent on sex and delivery protein. Fluids Barriers CNS 2022, 19, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, M.C.; Perez, J.; Wu, K.; Ellis, R.J.; Goodkin, K.; Koletar, S.L.; Andrade, A.; Yang, J.; Brown, T.T.; Palella, F.J.; Sacktor, N.; Tassiopoulos, K.; Erlandson, K.M. Baseline Neurocognitive Impairment (NCI) Is Associated With Incident Frailty but Baseline Frailty Does Not Predict Incident NCI in Older Persons With Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Clin Infect Dis 2021, 73, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, K.R.; Smurzynski, M.; Parsons, T.D.; Wu, K.; Bosch, R.J.; Wu, J.; McArthur, J.C.; Collier, A.C.; Evans, S.R.; Ellis, R.J. The prevalence and incidence of neurocognitive impairment in the HAART era. AIDS 2007, 21, 1915–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R.J.; Evans, S.R.; Clifford, D.B.; Moo, L.R.; McArthur, J.C.; Collier, A.C.; Benson, C.; Bosch, R.; Simpson, D.; Yiannoutsos, C.T.; Yang, Y.; Robertson, K.; Neurological AIDS Research Consortium; AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study Teams A5001 and A362. Clinical validation of the NeuroScreen. J Neurovirol 2005, 11, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milne, G.L.; Dai, Q.; Roberts, L.J., 2nd. The isoprostanes-25 years later. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015, 1851, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, G.L.; Nogueira, M.S.; Gao, B.; Sanchez, S.C.; Amin, W.; Thomas, S.; Oger, C.; Galano, J.M.; Murff, H.J.; Yang, G.; Durand, T. Identification of novel F2-isoprostane metabolites by specific UDP-glucuronosyltransferases. Redox Biol 2024, 70, 103020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, G.L.; Gao, B.; Terry, E.S.; Zackert, W.E.; Sanchez, S.C. Measurement of F2- isoprostanes and isofurans using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Free Radic Biol Med 2013, 59, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Knovich, M.A.; Coffman, L.G.; Torti, F.M.; Torti, S.V. Serum ferritin: Past.; present and future. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010, 1800, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganz, T. The Discovery of the Iron-Regulatory Hormone Hepcidin. Clin Chem 2019, 65, 1330–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kernan, K.F.; Carcillo, J.A. Hyperferritinemia and inflammation. Int Immunol 2017, 29, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, D.; Misra, V.; Yin, J.; Gabuzda, D. CSF Inflammation Markers Associated with Asymptomatic Viral Escape in Cerebrospinal Fluid of HIV-Positive Individuals on Antiretroviral Therapy. Viruses 2023, 15, 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okwuegbuna, O.K.; Kaur, H.; Jennifer, I.; Bush, W.S.; Bharti, A.; Umlauf, A.; Ellis, R.J.; Franklin, D.R.; Heaton, R.K.; McCutchan, J.A.; Kallianpur, A.R.; Letendre, S.L. Anemia and Erythrocyte Indices Are Associated With Neurocognitive Performance Across Multiple Ability Domains in Adults With HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2023, 92, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orino, K.; Lehman, L.; Tsuji, Y.; Ayaki, H.; Torti, S.V.; Torti, F.M. Ferritin and the response to oxidative stress. Biochem J 2001, 357 Pt 1, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.J.; Zucca, F.A.; Duyn, J.H.; Crichton, R.R.; Zecca, L. The role of iron in brain ageing and neurodegenerative disorders. Lancet Neurol 2014, 13, 1045–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, A.E.; Stacey, A.R.; Giannoulatou, E.; Marshall, E.; Sturges, P.; Chatha, K.; Smith, N.M.; Huang, X.; Xu, X.; Pasricha, S.R.; Li, N.; Wu, H.; Webster, C.; Prentice, A.M.; Pellegrino, P.; Williams, I.; Norris, P.J.; Drakesmith, H.; Borrow, P. Distinct patterns of hepcidin and iron regulation during HIV-1, HBV, and HCV infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, 12187–12192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiros-Roldan, E.; Castelli, F.; Lanza, P.; Pezzoli, C.; Vezzoli, M.; Biasiotto, G.; Zanella, I.; Inflammation in HIV Study Group. The impact of antiretroviral therapy on iron homeostasis and inflammation markers in HIV-infected patients with mild anemia. J Transl Med 2017, 15, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B.K.; Roth, L.M.; Grinspan, J.B.; Jordan-Sciutto, K.L. White matter loss and oligodendrocyte dysfunction in HIV: A consequence of the infection, the antiretroviral therapy or both? Brain Res 2019, 1724, 146397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T.; Jin, Y.; Huang, C.; Kim, Y.; Nir, T.M.; Gullett, J.M.; Jones, J.D.; Sayegh, P.; Chung, C.; Dang, B.H.; Singer, E.J.; Shattuck, D.W.; Jahanshad, N.; Bookheimer, S.Y.; Hinkin, C.H.; Zhu, H.; Thompson, P.M.; Thames, A.D. The joint effect of aging and HIV infection on microstructure of white matter bundles. Hum Brain Mapp 2019, 40, 4370–4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, Y.; Kato, T.; Watanabe, D.; Fukumoto, M.; Wada, K.; Oishi, N.; Nakakura, T.; Kuriyama, K.; Shirasaka, T.; Murai, T. Altered white matter microstructure and neurocognitive function of HIV-infected patients with low nadir CD4. J Neurovirol 2022, 28, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alakkas, A.; Ellis, R.J.; Watson, C.W.; Umlauf, A.; Heaton, R.K.; Letendre, S.; Collier, A.; Marra, C.; Clifford, D.B.; Gelman, B.; Sacktor, N.; Morgello, S.; Simpson, D.; McCutchan, J.A.; Kallianpur, A.; Gianella, S.; Marcotte, T.; Grant, I.; Fennema-Notestine, C.; CHARTER Group. White matter damage, neuroinflammation, and neuronal integrity in HAND. J Neurovirol 2019, 25, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorich, B.; Zhang, X.; Connor, J.R. H-ferritin is the major source of iron for oligodendrocytes. Glia 2011, 59, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, A.D.; Núñez, M.T. Oligodendrocytes: Functioning in a Delicate Balance Between High Metabolic Requirements and Oxidative Damage. Adv Exp Med Biol 2016, 949, 167–181. [Google Scholar]

- Cheli, V.T.; Santiago González, D.A.; Wan, Q.; Denaroso, G.; Wan, R.; Rosenblum, S.L.; Paez, P.M. H-ferritin expression in astrocytes is necessary for proper oligodendrocyte development and myelination. Glia 2021, 12, 2981–2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, C.; Kling, T.; Russo, B.; Miebach, K.; Kess, E.; Schifferer, M.; Pedro, L.D.; Weikert, U.; Fard, M.K.; Kannaiyan, N.; Rossner, M.; Aicher, M.L.; Goebbels, S.; Nave, K.A.; Krämer-Albers, E.M.; Schneider, A.; Simons, M. Oligodendrocytes Provide Antioxidant Defense Function for Neurons by Secreting Ferritin Heavy Chain. Cell Metab 2020, 32, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Surguladze, N.; Slagle-Webb, B.; Cozzi, A.; Connor, J.R. Cellular iron status influences the functional relationship between microglia and oligodendrocytes. Glia 2006, 54, 795–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saylor, D.; Dickens, A.M.; Sacktor, N.; Haughey, N.; Slusher, B.; Pletnikov, M.; Mankowski, J.L.; Brown, A.; Volsky, D.J.; McArthur, J.C. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder-pathogenesis and prospects for treatment. Nat Rev Neurol 2016, 12, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nnah, I.C.; Wessling-Resnick, M. Brain Iron Homeostasis: A Focus on Microglial Iron. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2018, 11, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Rodríguez, V.; Álvarez-Ríos, A.I.; Olivas-Martínez, I.; Pozo-Balado, M.D.M.; Bulnes-Ramos, Á.; Leal, M.; Pacheco, Y.M. Dysregulation of iron metabolism modulators in virologically suppressed HIV-infected patients. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 977316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, R.; Cheli, V.T.; Santiago-Gonzalez, D.A.; Rosenblum, S.L.; Wan, Q.; Paez, P.M. Impaired Postnatal Myelination in a Conditional Knockout Mouse for the Ferritin Heavy Chain in Oligodendroglial Cells. J Neurosci 2020, 40, 7609–7624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarjou, A.; Black, L.M.; McCullough, K.R.; Hull, T.D.; Esman, S.K.; Boddu, R.; Varambally, S.; Chandrashekar, D.S.; Feng, W.; Arosio, P.; Poli, M.; Balla, J.; Bolisetty, S. Ferritin Light Chain Confers Protection Against Sepsis-Induced Inflammation and Organ Injury. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finazzi, D.; Arosio, P. Biology of ferritin in mammals: an update on iron storage, oxidative damage and neurodegeneration. Arch Toxicol 2014, 88, 1787–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almer, G.; Teismann, P.; Stevic, Z.; Halaschek-Wiener, J.; Deecke, L.; Kostic, V.; Przedborski, S. Increased levels of the pro-inflammatory prostaglandin PGE2 in CSF from ALS patients. Neurology 2002, 58, 1277–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, K.D.; Noren Hooten, N.; Trzeciak, A.R.; Evans, M.K. Markers of oxidant stress that are clinically relevant in aging and age-related disease. Mech Ageing 2013, 134, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambegaokar, S.S.; Kolson, D.L. Heme oxygenase-1 dysregulation in the brain: implications for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Curr HIV Res 2014, 12, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sfera, A.; Bullock, K.; Price, A.; Inderias, L.; Osorio, C. Ferrosenescence: The iron age of neurodegeneration? Mech Ageing Dev 2018, 174, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; Morrison, B., 3rd; Stockwell, B.R. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Zheng, W.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, P.; Lai, Y.; Liu, C.; Wu, P.; Zhuang, H.; Huang, H.; Li, G.; Zhan, S.; Lao, Z.; Liu, X. Transcriptomic reveals the ferroptosis features of host response in a mouse model of Zika virus infection. J Med Virol 2023, 95, e28386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, J.; Kodavati, M.; Provasek, V.E.; Rao, K.S.; Mitra, S.; Hamilton, D.J.; Horner, P.J.; Vahidy, F.S.; Britz, G.W.; Kent, T.A.; Hegde, M.L. SARS-CoV-2 and the central nervous system: Emerging insights into hemorrhage-associated neurological consequences and therapeutic considerations. Ageing Res Rev 2022, 80, 101687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Sun, C.; Chen, X.; Han, Y.; Zang, W.; Jiang, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, J. COVID-19-Related Brain Injury: The Potential Role of Ferroptosis. J Inflamm Res 2022, 15, 2181–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galaris, D.; Barbouti, A.; Pantopoulos, K. Iron homeostasis and oxidative stress: An intimate relationship. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2019, 1866, 118535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coradduzza, D.; Congiargiu, A.; Chen, Z.; Zinellu, A.; Carru, C.; Medici, S. Ferroptosis and Senescence: A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairo, G.; Tacchini, L.; Pogliaghi, G.; Anzon, E.; Tomasi, A.; Bernelli-Zazzera, A. Induction of ferritin synthesis by oxidative stress. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation by expansion of the “free” iron pool. J Biol Chem 1995, 270, 700–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhoberac, B.B.; Vidal, R. Iron.; Ferritin.; Hereditary Ferritinopathy, and Neurodegeneration. Front Neurosci 2019, 13, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ding, Y.; Sun, L.; Shi, M.; Zhang, P.; Huang, Z.; Wang, J.; He, A.; Wang, J.; Wei, J.; Liu, M.; Liu, J.; Wang, G.; Yang, X.; Li, R. Ferritin light chain deficiency-induced ferroptosis is involved in preeclampsia pathophysiology by disturbing uterine spiral artery remodelling. Redox Biol 2022, 58, 102555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfera, A.; Thomas, K.G.; Andronescu, C.V.; Jafri, N.; Sfera, D.O.; Sasannia, S.; Zapata-Martín Del Campo, C.M.; Maldonado, J.C. Bromodomains in Human-Immunodeficiency Virus-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders: A Model of Ferroptosis-Induced Neurodegeneration. Front Neurosci 2022, 16, 904816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redig, A.J.; Berliner, N. Pathogenesis and clinical implications of HIV-related anemia in 2013. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2013, 2013, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallianpur, A.R.; Wang, Q.; Jia, P.; Hulgan, T.; Zhao, Z.; Letendre, S.L.; Ellis, R.J.; Heaton, R.K.; Franklin, D.R.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.; Collier, A.C.; Marra, C.M.; Clifford, D.B.; Gelman, B.B.; McArthur, J.C.; Morgello, S.; Simpson, D.M.; McCutchan, J.A.; Grant, I.; CHARTER Study Group. Anemia and Red Blood Cell Indices Predict HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Impairment in the Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy Era. J Infect Dis 2016, 213, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drakesmith, H.; Prentice, A. Viral infection and iron metabolism. Nat Rev Microbiol 2008, 6, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, M.; Sil, S.; Oladapo, A.; Thangaraj, A.; Periyasamy, P.; Buch, S. HIV-1 Tat-mediated microglial ferroptosis involves the miR-204-ACSL4 signaling axis. Redox Biol 2023, 62, 102689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duck, K.A.; Neely, E.B.; Simpson, I.A.; Connor, J.R. A role for sex and a common HFE gene variant in brain iron uptake. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2018, 38, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartzokis, G.; Lu, P.H.; Tingus, K.; Peters, D.G.; Amar, C.P.; Tishler, T.A.; Finn, J.P.; Villablanca, P.; Altshuler, L.L.; Mintz, J.; Neely, E.; Connor, J.R. Gender and iron genes may modify associations between brain iron and memory in healthy aging. Neuropsychopharmacology 2011, 36, 1375–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson, N.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, T.; Shen, J.; Bao, R.; Ni, M.; Liu, T.; Wang, Y.; Spincemaille, P. Age and sex related differences in subcortical brain iron concentrations among healthy adults. Neuroimage 2015, 122, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Tong, R.; Zhang, M.; Gillen, K.M.; Jiang, W.; Du, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, J. Age-dependent changes in brain iron deposition and volume in deep gray matter nuclei using quantitative susceptibility mapping. Neuroimage 2023, 269, 119923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, L.H.; Maki, P.M. Neurocognitive Complications of HIV Infection in Women: Insights from the WIHS Cohort. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 2021, 50, 175–191. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer, A.J.; Munsami, A.; Williams, T.; Andersen, L.S.; Nightingale, S.; Gouse, H.; Joska, J.; Thomas, K.G.F. Cognitive Differences between Men and Women with HIV: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2022, 37, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; You, L.; Zhang, J.; Chang, Y.Z.; Yu, P. Brain Iron Metabolism, Redox Balance and Neurological Diseases. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pond, R.A.; Collins, L.F.; Lahiri, C.D. Sex Differences in Non-AIDS Comorbidities Among People With Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallianpur, A.R.; Gittleman, H.; Letendre, S.; Ellis, R.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S.; Bush, W.S.; Heaton, R.; Samuels, D.C.; Franklin, D.R., Jr. Rosario-Cookson, D.; Clifford, D.B.; Collier, A.C.; Gelman, B.; Marra, C.M.; McArthur, J.C.; McCutchan, J.A.; Morgello, S.; Grant, I.; Simpson, D.; Connor, J.R.; Hulgan, T.; CHARTER Study Group. Cerebrospinal Fluid Ceruloplasmin, Haptoglobin, and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Are Associated with Neurocognitive Impairment in Adults with HIV Infection. Mol Neurobiol 2019, 56, 3808–3818. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, S.R.; Pérez-Santiago, J.; Hulgan, T.; Day, T.R.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.; Gittleman, H.; Letendre, S.; Ellis, R.; Heaton, R.; Patton, S.; Suben, J.D.; Franklin, D.; Rosario, D.; Clifford, D.B.; Collier, A.C.; Marra, C.M.; Gelman, B.B.; McArthur, J.; McCutchan, A.; Morgello, S.; Simpson, D.; Connor, J.; Grant, I.; Kallianpur, A. Cerebrospinal fluid cell-free mitochondrial DNA is associated with HIV replication, iron transport, and mild HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment. J Neuroinflammation 2017, 14, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tsvetkov, A.S.; Shen, H.M.; Isidoro, C.; Ktistakis, N.T.; Linkermann, A.; Koopman, W.J.H.; Simon, H.U.; Galluzzi, L.; Luo, S.; Xu, D.; Gu, W.; Peulen, O.; Cai, Q.; Rubinsztein, D.C.; Chi, J.T.; Zhang, D.D.; Li, C.; Toyokuni, S.; Liu, J.; Roh, J.L.; Dai, E.; Juhasz, G.; Liu, W.; Zhang, J.; Yang, M.; Liu, J.; Zhu, L.Q.; Zou, W.; Piacentini, M.; Ding, W.X.; Yue, Z.; Xie, Y.; Petersen, M.; Gewirtz, D.A.; Mandell, M.A.; Chu, C.T.; Sinha, D.; Eftekharpour, E.; Zhivotovsky, B.; Besteiro, S.; Gabrilovich, D.I.; Kim, D.H.; Kagan, V.E.; Bayir, H.; Chen, G.C.; Ayton, S.; Lünemann, J.D.; Komatsu, M.; Krautwald, S.; Loos, B.; Baehrecke, E.H.; Wang, J.; Lane, J.D.; Sadoshima, J.; Yang, W.S.; Gao, M.; Münz, C.; Thumm, M.; Kampmann, M.; Yu, D.; Lipinski, M.M.; Jones, J.W.; Jiang, X.; Zeh, H.J.; Kang, R.; Klionsky, D.J.; Kroemer, G.; Tang, D. International consensus guidelines for the definition, detection, and interpretation of autophagy-dependent ferroptosis. Autophagy 2024, 24, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Wessling-Resnick, M. Iron and mechanisms of emotional behavior. J Nutr Biochem 2014, 25, 1101–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Jia, B.; Li, J.; Li, Q.; Luo, C. The Interplay between Ferroptosis and Neuroinflammation in Central Neurological Disorders. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minchella, P.A.; Armitage, A.E.; Darboe, B.; Jallow, M.W.; Drakesmith, H.; Jaye, A.; Prentice, A.M.; McDermid, J.M. Elevated Hepcidin Is Part of a Complex Relation That Links Mortality with Iron Homeostasis and Anemia in Men and Women with HIV Infection. J Nutr 2015 145, 1194–1201. [CrossRef]

- Wolters, F.J.; Zonneveld, H.I.; Licher, S.; Cremers, L.G.M.; Ikram, M.K.; Koudstaal, P.J.; Vernooij, M.W.; Ikram, M.A.; Heart Brain Connection Collaborative Research Group. Hemoglobin and anemia in relation to dementia risk and accompanying changes on brain MRI. Neurology. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Neurocognitively Normal (N=237) |

Neurocognitively Impaired1 (N=82) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 51.4 (6.9) | 53.7 (8.3) |

| Sex, % female | 17.3 | 24.4 |

| Non-Hispanic Black2, % | 31.6 | 20.74 |

| Hispanic2, % | 20.7 | 36.6** |

| Efavirenz use, % | 51.5 | 39.05 |

|

Nadir CD4+ T-cells/µl, median (IQR) |

192 (67, 314) | 237 (80, 347) |

| HIV RNA <200 copies/ml, % | 95.7 | 96.3 |

| Anemia, % | 10.5 | 12.7 |

| HCV seropositive, % | 2.53 | 8.54* |

| ≥ 2 Comorbidities3, % | 32.5 | 47.6* |

| Biomarker | All PWH (N=324) Median (IQR) |

Men (N=263) Median (IQR) |

Women (N=61) Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum Fth-1, ng/ml | 289 (199, 499) | 311 (197, 497) | 277 (136, 526) |

| Serum Ftl, ng/ml | 12.2 (7.7, 22.1) | 12.4 (7.7, 22.4) | 11 (7.2, 19.6) |

|

Urinary 15-series F2-IsoPs1, ng/mg Creatinine |

57 (32, 84) | 56 (31, 84) | 60 (43, 78) |

|

Urinary 5-series F2-IsoPs1, ng/mg Creatinine |

71 (34, 109) | 66 (33, 110) | 71 (38, 98) |

| Biomarker | IL-6 (N=324) rho (p) |

sTNFR-II (N=324) rho (p) |

sCD163 (N=324) rho (p) |

15-F2-IsoPs (N=310) rho (p) |

5-F2-IsoPs (N=310) rho (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fth-1 All PWH Women Men |

-0.007 (0.91) -0.085 (0.52) 0.013 (0.83) |

-0.043 (0.45) 0.128 (0.33) -0.085 (0.17) |

0.0005 (0.99) 0.157 (0.23) -0.041 (0.51) |

-0.061 (0.28) -0.290 (0.02) 0.016 (0.80) |

0.033 (0.55) -0.181 (0.16) 0.089 (0.15) |

|

Ftl All PWH Women Men |

-0.026 (0.64) 0.018 (0.89) -0.030 (0.63) |

-0.078 (0.16) 0.086 (0.51) -0.117 (0.06) |

-0.050 (0.37) 0.024 (0.85) -0.066 (0.29) |

-0.017 (0.77) -0.471 (<0.001) 0.094 (0.14) |

0.048 (0.39) -0.347 (<0.01) 0.134 (0.03) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).