Submitted:

22 August 2024

Posted:

27 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1. Methods

1.1. Study Design

1.1. Socio-Demographic and Other Characteristics

1.1. Resilience Coping Levels

1.1. Statistical Analysis

1. Results

1.1. Sample Characteristics

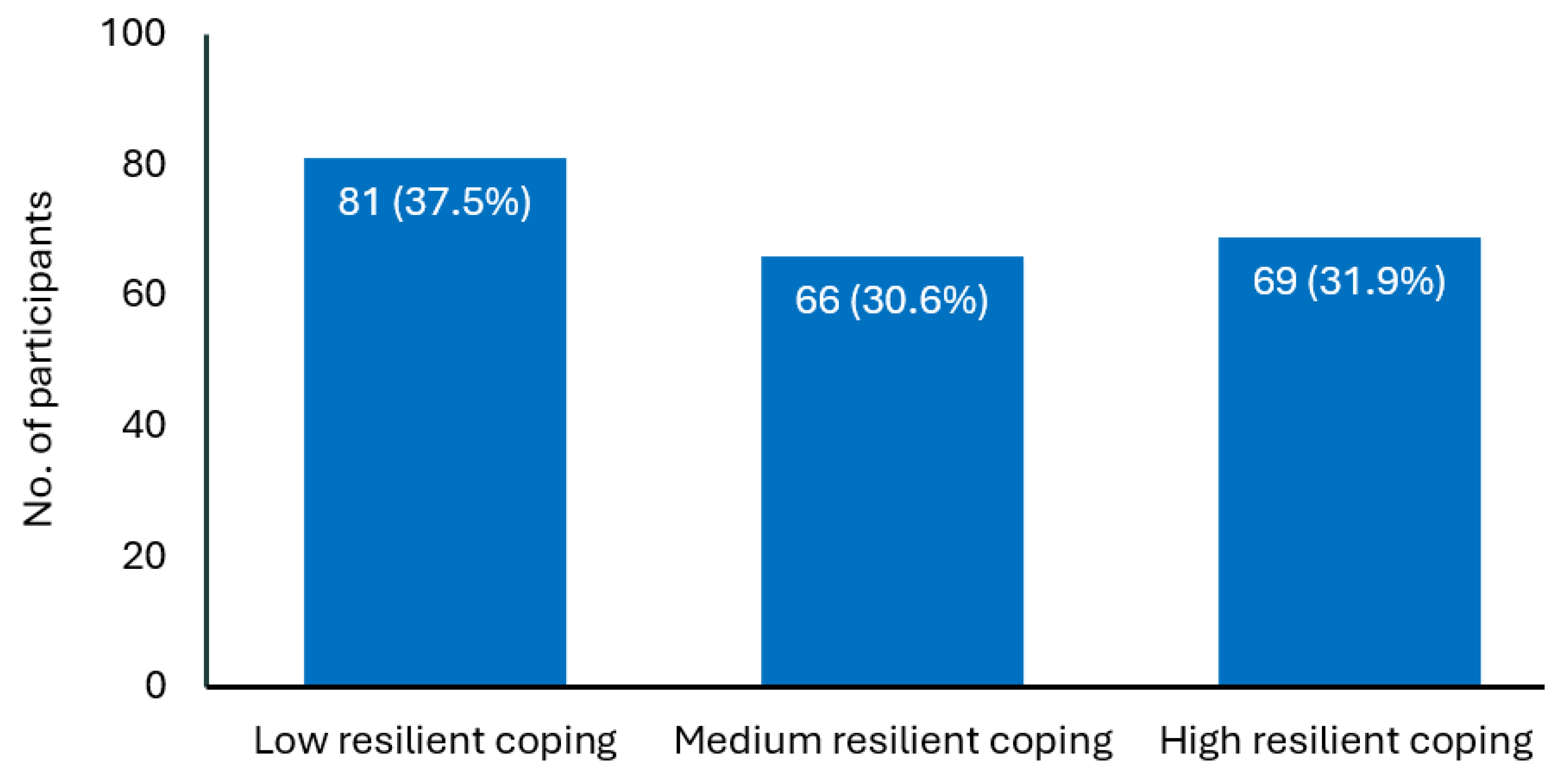

1.1. Resilience Coping Levels

1.1. Relationship between Resilience Coping Levels and Socio-demographic and Other Variables

1.1. Psychometric Properties of BRCS

1. Discussion

1. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dos Santos, L.M. Stress, burnout, and low self-efficacy of nursing professionals: A qualitative inquiry. Healthcare (Basel). 2020, 8, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babapour, A.R.; Gahassab-Mozaffari, N.; Fathnezhad-Kazemi, A. Nurses' job stress and its impact on quality of life and caring behaviors: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, A.C.; Lourens, M. Emotional challenges faced by nurses when taking care of children in a private hospital in South Africa. Africa J. Nurs. Midwifery. 2016, 18, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mróz, J. Predictive roles of coping and resilience for the perceived stress in nurses. Prog. Health. Sci. 2015, 5, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Babić, R.; Babić, M.; Rastović, P.; Ćurlin, M.; Šimić, J.; Mandić, K.; Pavlović, K. Resilience in health and illness. Psychiatr. Danub. 2020, 32, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Windle, G. The contribution of resilience to healthy ageing. Perspect. Public Heal. 2012, 132, 159–160. [Google Scholar]

- Friedly, L. Mental health, resilience, and inequalities. World Health Organization. 2009 (Available: https://www.womenindisplacement.org/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1471/files/2020-10/Mental%20health%2C%20resilience%20and%20inequalities.pdf) (Accessed June 2024).

- Shatté, A.; Perlman, A.; Smith, B.; Lynch, W. The positive effect of resilience on stress and business outcomes in difficult work environments. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 59, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, S.; Chang, Y.H.; Yao, Z.F.; Yang, M.H.; Yang, C.T. The effect of age and resilience on the dose-response function between the number of adversity factors and subjective well-being. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1332124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Chu, G.; Yeh, T.; Fernandez, R. Effects of interventions to promote resilience in nurses: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gito, M.; Ihara, H.; Ogata, H. The relationship of resilience, hardiness, depression and burnout among Japanese psychiatric hospital nurses. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2013, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.K.; Kim, M.; Park, J. Effects of resilience and job satisfaction on organizational commitment in Korean-American registered nurses. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. Adm. 2014, 20, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mealer, M.; Jones, J.; Newman, J.; McFann, K.K.; Rothbaum, B.; Moss, M. The presence of resilience is associated with a healthier psychological profile in intensive care unit (ICU) nurses: Results of a national survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, G.; Jackson, D.; Vickers, M.H.; Wilkes, L. Surviving workplace adversity: A qualitative study of nurses and midwives and their strategies to increase personal resilience. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 1500–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, V.G.; Wallston, K.A. The development and psychometric evaluation of the Brief Resilient Coping Scale. Assessment. 2004, 11, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P.L.; Brannan, J.D.; De Chesnay, M. Resilience in nurses: an integrative review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2014, 22, 720–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, S.M.D.; Baptista, P.C.P.; Silva, F.J.D.; Almeida, M.C.D.S.; Soares, R.A.Q. Resilience factors in nursing workers in the hospital context. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP. 2020, 54, e03550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, N.J.; McAloney-Kocaman, K.; Lippiett, K.; Ray, E.; Welch, L.; Kelly, C. Levels of resilience, anxiety and depression in nurses working in respiratory clinical areas during the COVID pandemic. Respir. Med. 2021, 176, 106219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamisa, N.; Oldenburg, B.; Peltzer, K.; Ilic, D. Work related stress, burnout, job satisfaction and general health of nurses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2015, 12, 652–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharaj, S.; Lees, T.; Lal, S. Negative mental states and their association to the cognitive function of nurses. J. Psychophysiol. 2019, 33, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnawi, N.; Barnawi, B. The relationship between nurses’ self-efficacy and occupational stress in the critical care unit at King Abdul-Aziz Hospital in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Nurs. Commun. 2023, 7, e2023028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryuwat, P.; Holmgren, J.; Asp, M.; Lövenmark, A.; Radabutr, M.; Sandborgh, M. Factors associated with resilience among Thai nursing students in the context of clinical education: A cross-sectional study. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.C.P.; Machado, A.P.G., Aranha, R.N. Identification of factors associated with resilience in medical students through a cross-sectional census. BMJ Open. 2017, 7, e017189. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, R.J.; Ahrens, K.F.; Kollmann, B.; Goldbach, N.; Chmitorz, A.; Weichert, D.; Fiebach, C.J.; Wessa, M.; Kalisch, R.; Lieb, K.; Tüscher, O.; Plichta, M.M.; Reif, A.; Matura, S. The impact of physical fitness on resilience to modern life stress and the mediating role of general self-efficacy. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 272, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weitzel, E.C.; Löbner, M.; Glaesmer, H.; Hinz, A.; Zeynalova, S.; Henger, S.; Engel, C.; Reyes, N.; Wirkner, K.; Löffler, M.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. The association of resilience with mental health in a large population-based sample (LIFE-Adult-Study). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022, 19, 15944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás, J.M.; Meléndez, J.C.; Sancho, P.; Mayordomo, T. Adaptation and initial validation of the BRCS in an elderly Spanish sample. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2012, 28, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limonero, J.T.; Tomás-Sábado, J.; Gómez-Romero, M.J.; Maté-Méndez, J.; Sinclair, V.G.; Wallston, K.A.; Gómez-Benito, J. Evidence for validity of the brief resilient coping scale in a young Spanish sample. Span. J. Psychol. 2014, 17, E34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moret-Tatay, C.; Muñoz, J.J.F.; Mollá, C.C.; Navarro-Pardo, E.; Alcover de la Hera, C.M. Psychometric properties and factor structure of the BRCS in an elderly Spanish sample. Anales De Psicología. 2015, 31, 1030–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocalevent, R.D.; Zenger, M.; Hinz, A.; Klapp, B.; Brähler, E. Resilient coping in the general population: standardization of the Brief Resilient Coping Scale (BRCS). Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2017, 15, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, SF. Validity of the Brief Resilience Scale and Brief Resilient Coping Scale in a Chinese sample. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020, 17, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirkiä, C.; Koivumaa-Honkanen, H.; Parkkola, K.; Hurtig, T. Resilient coping and the psychometric properties of the Brief Resilient Coping Scale (BRCS) among healthy young men at military call-up. Mil. Behav Health. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poejo, J.; Gomes, AI.; Granjo, P.; Dos Reis Ferreira, V. Resilience in patients and family caregivers living with congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG): A quantitative study using the Brief Resilience Coping Scale (BRCS). Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2024, 19, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Overall participants (N=216) | |

|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age, in years | 32.0 (5.3) |

| Age group, n (%) | |

| ≤25 years | 12 (5.6%) |

| 26–39 years | 189 (87.5%) |

| Over 40 years | 15 (6.9%) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 114 (52.8%) |

| Female | 96 (44.4%) |

| Prefer not to disclose | 6 (2.8%) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Single | 66 (30.6%) |

| Married | 127 (58.8%) |

| Divorced | 19 (8.8%) |

| Widow | 4 (1.9%) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Diploma in nursing | 29 (13.4%) |

| Graduate in nursing | 174 (80.6%) |

| Postgraduation in nursing | 13 (6.0%) |

| Nationality, n (%) | |

| Saudi | 173 (80.1%) |

| Filipino | 22 (10.2%) |

| Indian | 11 (5.1%) |

| Other | 10 (4.6%) |

| Clinical experience, n (%) | |

| ≤5 years | 68 (31.5%) |

| 6−14 years | 109 (50.5%) |

| ≥15 years | 39 (18.1%) |

| Work shift, n (%) | |

| Morning | 131 (60.6%) |

| Afternoon | 33 (15.3%) |

| Evening | 24 (11.1%) |

| Rotating | 28 (13.0%) |

| Posting ward, n (%) | |

| Emergency | 63 (29.2%) |

| Surgical | 49 (22.7%) |

| Medical | 41 (19.0%) |

| OPD | 22 (10.2%) |

| ICU | 18 (8.3%) |

| PHC | 8 (3.7%) |

| Others | 5 (2.3%) |

| Pediatric | 4 (1.9%) |

| Obstetrics/Gynecology | 3 (1.4%) |

| Laboratory | 3 (1.4%) |

| Overall health*, n (%) | |

| ≤4 | 25 (11.6%) |

| 5−7 | 43 (19.9%) |

| 8−10 | 148 (68.5%) |

| Presence of a chronic condition**, n (%) | |

| Yes | 40 (18.5%) |

| No | 176 (81.5%) |

| Variable | Resilience coping levels | Point estimates | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Moderate | High | |||

| Age | F=12.07 | 0.000† | |||

| Mean (SD) | 29.9 (5.1) | 33.2 (5.0) | 33.4 (5.0) | ||

| 95% CI | 28.79–31.01 | 31.99–34.41 | 32.22–35.58 | ||

| Sex, n (%) | χ2=2.59 | 0.628 | |||

| Male | 40 (35.1%) | 37 (32.5%) | 37 (32.5%) | ||

| Female | 37 (38.5%) | 28 (29.2%) | 31 (32.3%) | ||

| Prefer not to disclose | 4 (66.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | ||

| Marital status, n (%) | χ2=6.22 | 0.399 | |||

| Single | 28 (42.4%) | 18 (27.3%) | 20 (30.3%) | ||

| Married | 41 (32.3%) | 44 (34.6%) | 42 (33.1%) | ||

| Divorced | 9 (47.4%) | 4 (21.1%) | 6 (31.6%) | ||

| Widow | 3 (75.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | ||

| Education, n (%) | χ2=2.21 | 0.697 | |||

| Diploma in nursing | 14 (48.3%) | 8 (27.6%) | 7 (24.1%) | ||

| Graduate in nursing | 62 (35.6%) | 55 (31.6%) | 57 (32.8%) | ||

| Postgraduation in nursing | 5 (38.5%) | 3 (23.1%) | 5 (38.5%) | ||

| Nationality, n (%) | χ2=7.00 | 0.320 | |||

| Saudi | 7 (63.6%) | 1 (9.1%) | 3 (27.3%) | ||

| Filipino | 5 (22.7%) | 10 (45.5%) | 7 (31.8%) | ||

| Indian | 66 (38.2%) | 52 (30.1%) | 55 (31.8%) | ||

| Other | 3 (30.0%) | 3 (30.0%) | 4 (40.0%) | ||

| Clinical experience, n (%) | χ2=7.00 | 0.320 | |||

| ≤5 years | 33 (47.1%) | 17 (24.3%) | 20 (28.6%) | ||

| 6−14 years | 42 (34.4%) | 40 (32.8%) | 40 (32.8%) | ||

| ≥15 years | 6 (25.0%) | 9 (37.5%) | 9 (37.5%) | ||

| Work shift, n (%) | χ2=4.31 | 0.635 | |||

| Morning | 49 (37.4%) | 43 (32.8%) | 39 (29.8%) | ||

| Afternoon | 16 (48.5%) | 7 (21.2%) | 10 (30.3%) | ||

| Evening | 8 (33.3%) | 8 (33.3%) | 8 (33.3%) | ||

| Rotating | 8 (28.6%) | 8 (28.6%) | 12 (42.9%) | ||

| Posting ward, n (%) | χ2=24.75 | 0.132 | |||

| Emergency | 19 (46.3%) | 12 (29.3%) | 10 (24.4%) | ||

| Surgical | 26 (53.1%) | 14 (28.6%) | 9 (18.4%) | ||

| Medical | 14 (22.2%) | 23 (36.5%) | 26 (41.3%) | ||

| OPD | 6 (27.3%) | 8 (36.4%) | 8 (36.4%) | ||

| ICU | 4 (22.2%) | 6 (33.3%) | 8 (44.4%) | ||

| PHC | 1 (33.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (66.7%) | ||

| Others | 2 (66.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (33.3%) | ||

| Pediatric | 3 (75.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | ||

| Obstetrics/Gynecology | 3 (37.5%) | 2 (25.0%) | 3 (37.5%) | ||

| Laboratory | 3 (60.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | ||

| Overall health*, n (%) | χ2=49.34 | 0.000 | |||

| ≤4 | 20 (80.0%) | 4 (16.0%) | 1 (4.0%) | ||

| 5−7 | 28 (65.1%) | 9 (20.9%) | 6 (14.0%) | ||

| 8−10 | 33 (22.3%) | 53 (35.8%) | 62 (41.9%) | ||

| Presence of a chronic condition**, n (%) | χ2=82.22 | 0.000 | |||

| Yes | 21 (25.0%) | 55 (65.5%) | 8 (9.5%) | ||

| No | 60 (45.5%) | 11 (8.3%) | 61 (46.2%) | ||

| Characteristics | Estimate | SE | Walds χ2 | p-value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience coping level | |||||

| Low | 5.896 | 2.720 | 4.699 | 0.030 | 0.565 to 11.228 |

| Medium | 7.609 | 2.739 | 7.719 | 0.005 | 2.241 to 12.976 |

| High | 0a | – | – | – | – |

| Data mode | |||||

| Offline | 0.422 | 0.448 | 0.885 | 0.347 | -0.457 to 1.300 |

| Online | 0a | – | – | – | – |

| Age | 0.166 | 0.055 | 9.152 | 0.002 | 0.058 to 0.273 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | -0.361 | 1.148 | 0.076 | 0.783 | -2.567 to 1.934 |

| Female | 0.062 | 1.126 | 0.003 | 0.956 | -2.145 to 2.268 |

| Prefer not to disclose | 0a | – | – | – | – |

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 2.169 | 1.608 | 1.819 | 0.177 | -0.983 to 5.320 |

| Married | 1.891 | 1.558 | 1.474 | 0.225 | -1.161 to 4.994 |

| Divorced | 2.122 | 1.653 | 1.649 | 0.199 | -1.117 to 5.361 |

| Widow | 0a | – | – | – | – |

| Education | |||||

| Diploma in nursing | -1.425 | 0.826 | 2.972 | 0.085 | -3.044 to 0.195 |

| Graduate in nursing | -0.793 | 0.706 | 1.259 | 0.262 | -2.177 to 0.592 |

| Postgraduation in nursing | 0a | – | – | – | – |

| Nationality | |||||

| Saudi | -0.826 | 1.074 | 0.592 | 0.442 | -2.932 to 1.279 |

| Filipino | -0.692 | 0.934 | 0.549 | 0.459 | -2.522 to 1.138 |

| Indian | -0.460 | 0.817 | 0.317 | 0.574 | -2.061 to 1.141 |

| Other | 0a | – | – | – | – |

| Clinical experience | -0.072 | 0.055 | 2.495 | 0.114 | -0.162 to 0.017 |

| Work shift | |||||

| Morning | -0.749 | 0.466 | 2.586 | 0.108 | -1.661 to 0.164 |

| Afternoon | -0.840 | 0.612 | 1.884 | 0.170 | -2.039 to 0.359 |

| Evening | -0.707 | 0.646 | 1.197 | 0.274 | -1.973 to 0.559 |

| Rotating | 0a | – | – | – | – |

| Posting ward | |||||

| Medical | 2.159 | 1.423 | 2.300 | 0.129 | -0.631 to 4.949 |

| Surgical | 2.115 | 1.384 | 2.335 | 0.127 | -0.598 to 4.827 |

| Emergency | 2.477 | 1.334 | 3.449 | 0.063 | -0.137 to 5.091 |

| OPD | 2.755 | 1.398 | 3.885 | 0.049 | 0.016 to 5.494 |

| ICU | 2.980 | 1.394 | 4.573 | 0.032 | 0.249 to 5.712 |

| Laboratory | 3.486 | 1.798 | 3.761 | 0.052 | 0.037 to 7.010 |

| Obstetrics/Gynecology | 2.049 | 1.856 | 1.219 | 0.270 | -1.589 to 5.687 |

| Pediatric | 1.626 | 1.780 | 0.834 | 0.361 | -1.863 to 5.116 |

| PHC | 1.711 | 1.420 | 1.451 | 0.228 | -1.863 to 5.116 |

| Others | 0a | – | – | – | – |

| Overall health* | |||||

| ≤4 | -2.548 | 0.613 | 17.270 | 0.000 | -3.750 to -1.346 |

| 5−7 | -1.394 | .410 | 11.582 | 0.001 | -2.197 to -0.591 |

| 8−10 | 0a | – | – | – | – |

| Presence of a chronic condition** | |||||

| Yes | -0.099 | 0.415 | 0.057 | 0.811 | -0.914 to 0.715 |

| No | 0a | – | – | – | – |

| S. No. | BRCS item | Mean (SD) | Item-Total Correlations | Cronbach’s alpha if item deleted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I look for creative ways to alter difficult situations | 3.64 (1.06) | 0.56 | 0.77 |

| 2 | Regardless of what happens to me, I believe I can control my reaction to it | 3.65 (1.16) | 0.59 | 0.76 |

| 3 | I believe I can grow in positive ways by dealing with difficult situations | 3.67 (1.17) | 0.56 | 0.77 |

| 4 | I actively look for ways to replace the losses I encounter in life | 3.62 (1.21) | 0.73 | 0.68 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).