Submitted:

29 August 2024

Posted:

02 September 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Anxiety-Based Cognitive Distortions Pertaining to Somatic Perception (ABCD-SP)

2.1. An Overview of The Role of ABCD-SP in the Negative Sequelae of CNCP

2.2. ABCD-SP Validated Assessment Tools

2.2.a. The Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FAB)

2.2.b. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS)

2.2.c. The Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK)

3. Pathology of Anxiety-Based Cognitive Distortions Pertaining to Somatic Perception – Proposed Mechanisms

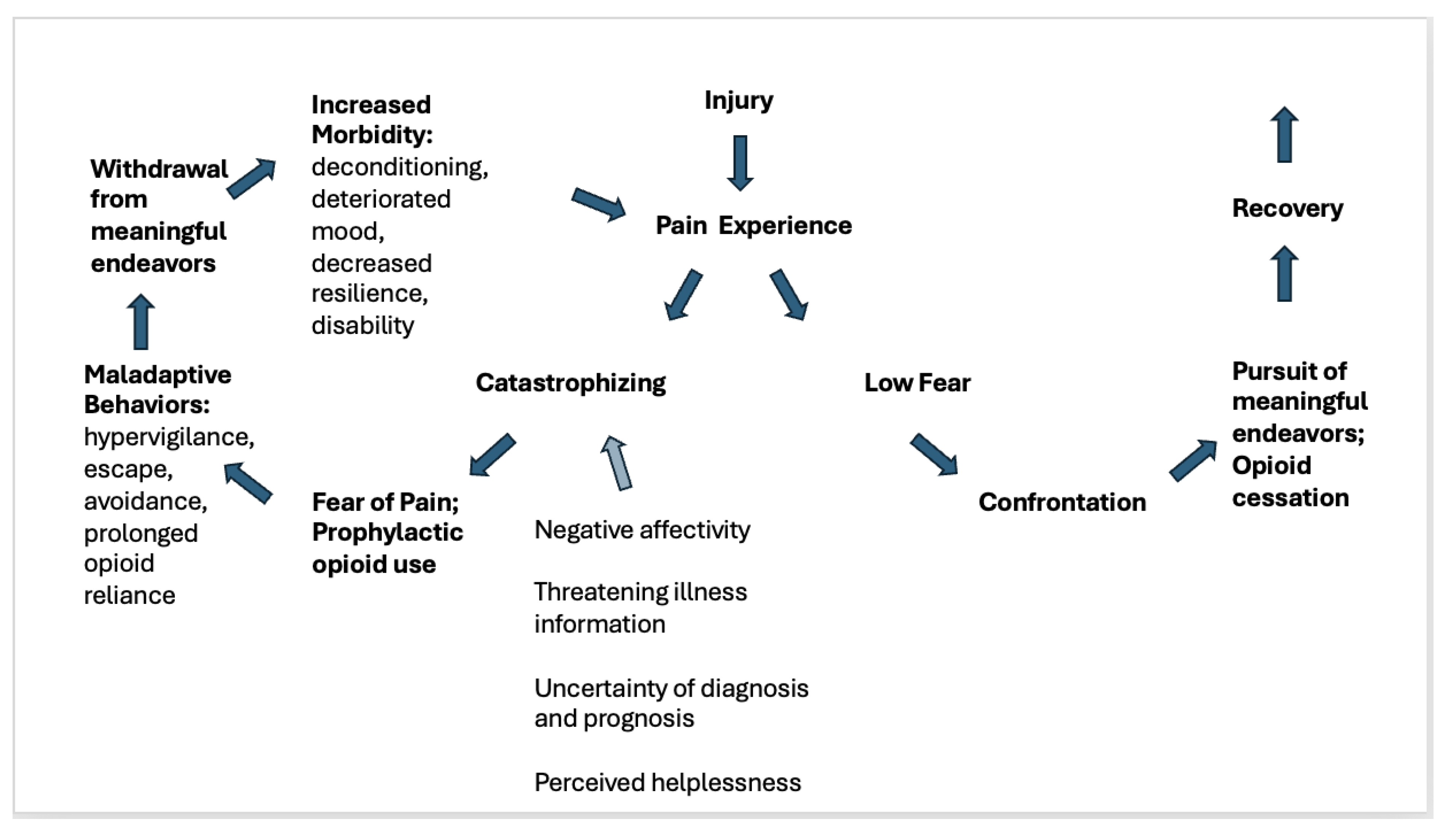

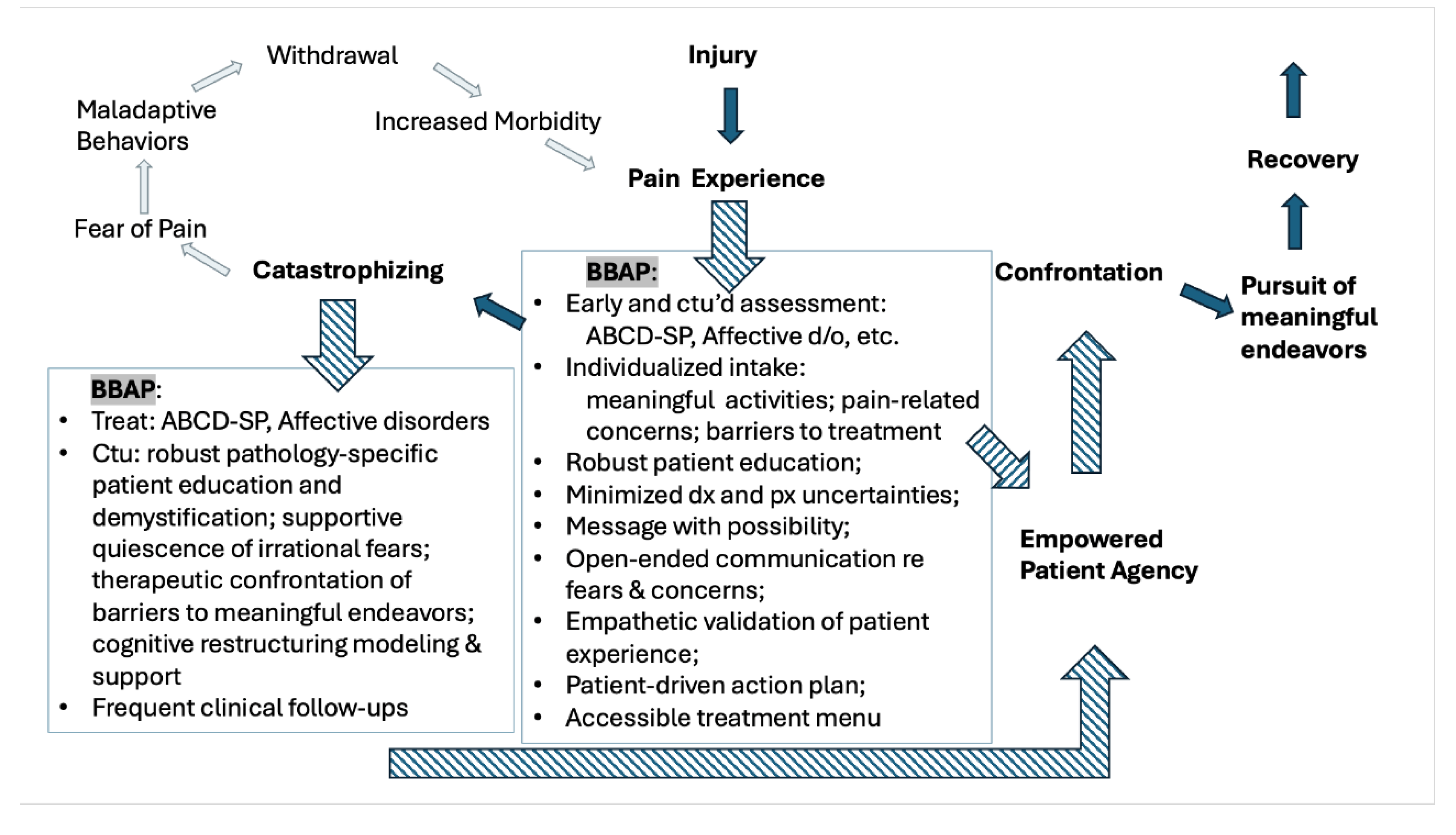

4. The Call for a Belief and Behavior Action Plan (BBAP)– Theoretical Considerations

5. Creating a Belief and Behavior Action Plan (BBAP) - Clinical Considerations

6. Creating a Belief and Behavior Action Plan (BBAP)- Recommendations and Practical Considerations

-

Utilize standardized assessments and short answer questionnaires upon initial evaluation, and periodically and follow up, to assess and monitor ABCD-SP rehabilitative interference potential:

-

Standardized assessments:

-

Short answer questionnaires to catalogue patients’ perceptions regarding:

-

Activities of meaning to lay the groundwork to create an individualized care plan to:

-

-

Implement an intentional BBAP inquiry and communication strategy and style in the clinical visit:

- Invest heavily in the first visit by performing a deep exploration and inquiry into the patient’s pain experience and their current related beliefs and resulting behaviors [94].

- Use validating active listening, which has been shown to increase patient adherence to care planning [118].

-

Lean into, and address head-on, patient’s accounts of suffering and fear in the clinical setting, so as to:

- dispel the ability of these sentiments to hijack adaptive recovery processes when the patient ruminates alone [86].

- decrease the suffering of invisibility that patients with CNCP often face. While it’s difficult for clinicians to focus on a patients’ suffering because of the accompanying sense of clinical impotence, and frequent lack of objective solutions, simply witnessing the patient’s subjective suffering experience may decrease suffering in itself [119].

- Be cognizant of both the implicit and explicit messages inherent in communications imparted by the clinician to the patient about diagnosis and prognosis. Positive self-perceptions and health-related optimism correlate with improve pain suffering, pain-related disability [85,88,90] and even improved longevity [123]. When possible and appropriate, choose vocabulary and descriptors that de-escalate the patient’s perceived threat of nociceptive input, and highlight functional and meaningful possibility.

- Message with mindfulness of potential trauma-affected hyper arousal and increased sensitivity to pain [124].

-

Increase healthcare literacy and promote pathological understanding:

- Ask patients to paraphrase their understanding of their injury, pain and pathology. Note terminology used and connect medical terminology to patient’s perceptions and descriptions to promote demystification [50,85]. Correct misconceptions and maintain patient-generated frame of reference and terminology, when appropriate.

- Consider inviting a call and paraphrased repeat opportunity between the clinician and the patient to improve comprehension of pathology and related care plan.

- Assuming the standard use of language interpreters to bridge translation barriers, also employ visual aids and physical models to engage multiple patient learning style preferences to explain not only pathology, but the mechanisms of pain symptomatology in an effort to decrease anxiety related to somatic presentations.

-

Orient to when fear of catastrophe is warranted.

- Debrief previous urgent, or emergent, clinical visits to seek pain treatment. Discuss causational factors and care plan for future episodes in the form of improved medication organization, strategized BBAP interventions, change of medication regimen for more effective analgesia, change of formulary or treatment type for improved access, etc.

- Orient to “red flag” signs and symptoms that medically warrant emergent attention and educate to differentiate from chronic, stable stimuli.

-

BBAP components should include:

-

Cultivation of an empowering, patient-driven action plan to complement the larger treatment plan containing the following elements:

- Facilitation of a menu of active, self-care options to address various pain levels and flares. Includes features accessible in and out of the home, and which represent treatment modalities from a variety of psychosocial domains: behavioral, physical, social, medical, spiritual, occupational, etc.

-

Minimized barriers- and the “gate keeper” nature- of clinical treatment options where possible, and within the confines of evidence-based care, which inherently promote a role of helplessness, perceptions of scarcity, and an external locus of control.

-

7. Discussion & Limitations

8. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- S. M. Rikard, “Chronic Pain Among Adults — United States, 2019–2021,” MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, vol. 72, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. J. Smith and B. E. Hillner, “The Cost of Pain,” JAMA Network Open, vol. 2, no. 4, p. e191532, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- “Opioid Refugees: Patients Adrift in Search of Pain Relief,” MPR. Accessed: May 06, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.empr.com/home/mpr-first-report/painweek-2013/opioid-refugees-patients-adrift-in-search-of-pain-relief/.

- M. J. Silva and Z. Kelly, “The Escalation of the Opioid Epidemic Due to COVID-19 and Resulting Lessons About Treatment Alternatives,” American Journal of Managed Care, vol. 26, no. 7, Jun. 2020, [Online]. Available. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Silva, Z. Coffee, Goza, Jessica, and Rumril, Kelly, “Microinduction to Buprenorphine from Methadone for Chronic Pain: Outpatient Protocol with Case Examples,” J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother., no. 36(1):40-48, Mar. 2022,. [CrossRef]

- Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R., “CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain — United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65(No. RR-1):1–49.” 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. Alcon, E. C. Alcon, E. Bergman, J. Humphrey, R. M. Patel, and S. Wang-Price, “The Relationship between Pain Catastrophizing and Cognitive Function in Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: A Scoping Review,” Pain Res Manag, vol. 2023, p. 5851450, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Brouwer et al., “Biopsychosocial baseline values of 15 000 patients suffering from chronic pain: Dutch DataPain study,” Reg Anesth Pain Med, vol. 45, no. 10, pp. 774–782, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- “APA Dictionary of Psychology.” Accessed: Jul. 19, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://dictionary.apa.org/.

- “PCSManual_English.pdf.” Accessed: May 08, 2020. [Online]. Available: http://sullivan-painresearch.mcgill.ca/pdf/pcs/PCSManual_English.pdf.

- G. Waddell, M. G. Waddell, M. Newton, I. Henderson, D. Somerville, and C. J. Main, “A Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability,” Pain, vol. 52, no. 2, Art. no. 2, Feb. 1993. [CrossRef]

- R. Neblett, M. M. R. Neblett, M. M. Hartzell, T. G. Mayer, E. M. Bradford, and R. J. Gatchel, “Establishing clinically meaningful severity levels for the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK-13),” European Journal of Pain, vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 701–710, 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. J. L. Sullivan, M. O. M. J. L. Sullivan, M. O. Martel, D. Tripp, A. Savard, and G. Crombez, “The relation between catastrophizing and the communication of pain experience,” Pain, vol. 122, no. 3, pp. 282–288, 2006. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Linton and W. S. Shaw, “Impact of Psychological Factors in the Experience of Pain,” Physical Therapy, vol. 91, no. 5, Art. no. 5, May 2011. [CrossRef]

- G. Waddell, D. G. Waddell, D. Somerville, I. Henderson, and M. Newton, “Objective clinical evaluation of physical impairment in chronic low back pain,” Spine, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 617–628, Jun. 1992. [CrossRef]

- H. Philips and M. Jahanshahi, “The components of pain behaviour report.,” Behaviour research and therapy, 1986. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Silva, Z. M. J. Silva, Z. Coffee, C. Ho Alex Yu, and M. O. Martel, “Anxiety and Fear Avoidance Beliefs and Behavior May Be Significant Risk Factors for Chronic Opioid Analgesic Therapy Reliance for Patients with Chronic Pain – Results from a Preliminary Study,” Pain Medicine, no. pnab069, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Silva, Z. M. J. Silva, Z. Coffee, C. H. A. Yu, and J. Hu, “Changes in Psychological Outcomes after Cessation of Full Mu Agonist Long-Term Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain,” Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 12, no. 4, Art. no. 4, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Silva, Z. M. J. Silva, Z. Coffee, and C. H. Yu, “Prolonged Cessation of Chronic Opioid Analgesic Therapy: A Multidisciplinary Intervention,” The American Journal of Managed Care, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 60–65, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Borkum, “Maladaptive Cognitions and Chronic Pain: Epidemiology, Neurobiology, and Treatment,” Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, vol. 28, pp. 4–24, Mar. 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Silva, Z. M. J. Silva, Z. Coffee, and C. H. Yu, “The Correlation of Psychological Questionnaire Response Changes After Cessation of Chronic Opioid Analgesic Therapy in Patients with Chronic Pain,” Manuscript submitted for publication, 2020.

- N. I. on D. Abuse, “Prescription Opioids DrugFacts,” National Institute on Drug Abuse. Accessed: Oct. 19, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/prescription-opioids.

- E. F. Wedam, G. E. E. F. Wedam, G. E. Bigelow, R. E. Johnson, P. A. Nuzzo, and M. C. P. Haigney, “QT-interval effects of methadone, levomethadyl, and buprenorphine in a randomized trial,” Arch Intern Med, vol. 167, no. 22, pp. 2469–2475, Dec. 2007. [CrossRef]

- T. Antony, S. Y. T. Antony, S. Y. Alzaharani, and S. H. El-Ghaiesh, “Opioid-induced hypogonadism: Pathophysiology, clinical and therapeutics review,” Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology, vol. 47, no. 5, pp. 741–750, 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. K. Eisenstein and T. J. Rogers, “Drugs of Abuse,” in Neuroimmune Pharmacology, T. Ikezu and H. E. Gendelman, Eds., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2017, pp. 661–678. [CrossRef]

- L. F. Chu, M. S. L. F. Chu, M. S. Angst, and D. Clark, “Opioid-induced hyperalgesia in humans: Molecular mechanisms and clinical considerations,” Clin J Pain, vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 479–496, Aug. 2008. [CrossRef]

- M. Lee, S. M. M. Lee, S. M. Silverman, H. Hansen, V. B. Patel, and L. Manchikanti, “A comprehensive review of opioid-induced hyperalgesia,” Pain Physician, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 145–161, Apr. 2011.

- R. A. Rudd, “Increases in Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths — United States, 2010–2015,” MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, vol. 65, 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Xu, “Mortality in the United States, 2018,” no. 355, Art. no. 355, 2020.

- N. I. on D. Abuse, “Overdose Death Rates,” National Institute on Drug Abuse. Accessed: Jun. 09, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates.

- S. Z. George, J. M. S. Z. George, J. M. Fritz, J. E. Bialosky, and D. A. Donald, “The effect of a fear-avoidance-based physical therapy intervention for patients with acute low back pain: Results of a randomized clinical trial,” Spine (Phila Pa 1976), vol. 28, no. 23, pp. 2551–2560, Dec. 2003. [CrossRef]

- R. P. Miller, S. H. R. P. Miller, S. H. Kori, and D. D. Todd, “The Tampa Scale: A Measure of Kinisophobia,” The Clinical Journal of Pain, vol. 7, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Mar. 1991.

- K. Hudes, “The Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia and neck pain, disability and range of motion: A narrative review of the literature,” J Can Chiropr Assoc, vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 222–232, Sep. 2011.

- H. Adams, T. H. Adams, T. Ellis, W. D. Stanish, and M. J. L. Sullivan, “Psychosocial factors related to return to work following rehabilitation of whiplash injuries,” J Occup Rehabil, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 305–315, Jun. 2007. [CrossRef]

- M. J. L. Sullivan, S. R. M. J. L. Sullivan, S. R. Bishop, and J. Pivik, “The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and Validation,” Psychological Assessment, no. 7(4), pp. 524–532, 1995. [CrossRef]

- J. W. Vlaeyen, A. M. J. W. Vlaeyen, A. M. Kole-Snijders, A. M. Rotteveel, R. Ruesink, and P. H. Heuts, “The role of fear of movement/(re)injury in pain disability,” J Occup Rehabil, vol. 5, no. 4, Art. no. 4, Dec. 1995. [CrossRef]

- G. Crombez, J. W. G. Crombez, J. W. Vlaeyen, P. H. Heuts, and R. Lysens, “Pain-related fear is more disabling than pain itself: Evidence on the role of pain-related fear in chronic back pain disability,” Pain, vol. 80, no. 1–2, Art. no. 1–2, Mar. 1999. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Wertli, R. M. M. Wertli, R. Eugster, U. Held, J. Steurer, R. Kofmehl, and S. Weiser, “Catastrophizing—A prognostic factor for outcome in patients with low back pain: A systematic review,” The Spine Journal, vol. 14, no. 11, pp. 2639–2657, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- G. T. T. Helmerhorst, A.-M. G. T. T. Helmerhorst, A.-M. Vranceanu, M. Vrahas, M. Smith, and D. Ring, “Risk Factors for Continued Opioid Use One to Two Months After Surgery for Musculoskeletal Trauma,” JBJS, vol. 96, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Arteta, B. J. Arteta, B. Cobos, Y. Hu, K. Jordan, and K. Howard, “Evaluation of How Depression and Anxiety Mediate the Relationship Between Pain Catastrophizing and Prescription Opioid Misuse in a Chronic Pain Population,” Pain Med, vol. 17, no. 2, Art. no. 2, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. O. Martel, R. N. M. O. Martel, R. N. Jamison, A. D. Wasan, and R. R. Edwards, “The Association Between Catastrophizing and Craving in Patients with Chronic Pain Prescribed Opioid Therapy: A Preliminary Analysis,” Pain Med, vol. 15, no. 10, Art. no. 10, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. O. Martel, A. D. M. O. Martel, A. D. Wasan, R. N. Jamison, and R. R. Edwards, “Catastrophic thinking and increased risk for prescription opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, vol. 132, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Seminowicz and K. D. Davis, “Cortical responses to pain in healthy individuals depends on pain catastrophizing,” Pain, vol. 120, no. 3, pp. 297–306, Feb. 2006. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Seminowicz et al., “Cognitive-behavioral therapy increases prefrontal cortex gray matter in patients with chronic pain,” J Pain, vol. 14, no. 12, pp. 1573–1584, Dec. 2013. [CrossRef]

- K. Burton, G. K. Burton, G. Waddell, K. M. Tillotson, and N. Summerton, “Information and advice to patients with back pain can have a positive effect. A randomized controlled trial of a novel educational booklet in primary care,” Spine, vol. 24, no. 23, pp. 2484–2491, Dec. 1999. [CrossRef]

- J. W. S. Vlaeyen and S. Morley, “Cognitive-behavioral treatments for chronic pain: What works for whom?,” Clin J Pain, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 1–8, Feb. 2005. [CrossRef]

- P. Jellema, H. E. P. Jellema, H. E. van der Horst, J. W. S. Vlaeyen, W. A. B. Stalman, L. M. Bouter, and D. A. W. M. van der Windt, “Predictors of Outcome in Patients With (Sub)Acute Low Back Pain Differ Across Treatment Groups,” Spine, vol. 31, no. 15, pp. 1699–1705, Jul. 2006. [CrossRef]

- M. J. L. Sullivan, H. M. J. L. Sullivan, H. Adams, T. Rhodenizer, and W. D. Stanish, “A psychosocial risk factor--targeted intervention for the prevention of chronic pain and disability following whiplash injury,” Phys Ther, vol. 86, no. 1, pp. 8–18, Jan. 2006. [CrossRef]

- J. W. Vlaeyen and S. J. Linton, “Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: A state of the art,” Pain, vol. 85, no. 3, pp. 317–332, Apr. 2000. [CrossRef]

- M. Leeuw, M. E. J. B. M. Leeuw, M. E. J. B. Goossens, S. J. Linton, G. Crombez, K. Boersma, and J. W. S. Vlaeyen, “The fear-avoidance model of musculoskeletal pain: Current state of scientific evidence,” J Behav Med, vol. 30, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Feb. 2007. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Fritz and S. Z. George, “Identifying psychosocial variables in patients with acute work-related low back pain: The importance of fear-avoidance beliefs,” Phys Ther, vol. 82, no. 10, pp. 973–983, Oct. 2002.

- S. Z. George, J. M. S. Z. George, J. M. Fritz, and R. E. Erhard, “A comparison of fear-avoidance beliefs in patients with lumbar spine pain and cervical spine pain,” Spine, vol. 26, no. 19, Art. no. 19, Oct. 2001. [CrossRef]

- S. Z. George, J. M. S. Z. George, J. M. Fritz, and D. W. McNeil, “Fear-avoidance beliefs as measured by the fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire: Change in fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire is predictive of change in self-report of disability and pain intensity for patients with acute low back pain,” Clin J Pain, vol. 22, no. 2, Art. no. 2, Feb. 2006. [CrossRef]

- T. Ryum and T. C. Stiles, “Changes in pain catastrophizing, fear-avoidance beliefs, and pain self-efficacy mediate changes in pain intensity on disability in the treatment of chronic low back pain,” Pain Rep, vol. 8, no. 5, p. e1092, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Boersma, S. K. Boersma, S. Linton, T. Overmeer, M. Jansson, J. Vlaeyen, and J. de Jong, “Lowering fear-avoidance and enhancing function through exposure in vivo. A multiple baseline study across six patients with back pain,” Pain, vol. 108, no. 1–2, pp. 8–16, Mar. 2004. [CrossRef]

- E. Besen, B. E. Besen, B. Gaines, S. J. Linton, and W. S. Shaw, “The role of pain catastrophizing as a mediator in the work disability process following acute low back pain,” Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research, vol. 22, no. 1, p. e12085, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. R. de Jong, J. W. S. J. R. de Jong, J. W. S. Vlaeyen, P. Onghena, M. E. J. B. Goossens, M. Geilen, and H. Mulder, “Fear of movement/(re)injury in chronic low back pain: Education or exposure in vivo as mediator to fear reduction?,” Clin J Pain, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 9–17; discussion 69-72, 2005. [CrossRef]

- T. Ryum, H. T. Ryum, H. Hartmann, P. Borchgrevink, K. De Ridder, and T. C. Stiles, “The effect of in-session exposure in Fear-Avoidance treatment of chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial,” European Journal of Pain, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 171–188, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. W. S. Vlaeyen, J. J. W. S. Vlaeyen, J. de Jong, M. Geilen, P. H. T. G. Heuts, and G. van Breukelen, “The treatment of fear of movement/(re)injury in chronic low back pain: Further evidence on the effectiveness of exposure in vivo,” Clin J Pain, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 251–261, 2002. [CrossRef]

- L. E. Simons, “Fear of pain in children and adolescents with neuropathic pain and complex regional pain syndrome,” PAIN, vol. 157, p. S90, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Cleland, J. M. J. A. Cleland, J. M. Fritz, and G. P. Brennan, “Predictive validity of initial fear avoidance beliefs in patients with low back pain receiving physical therapy: Is the FABQ a useful screening tool for identifying patients at risk for a poor recovery?,” Eur Spine J, vol. 17, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Jan. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yuan et al., “The relationship between emotion regulation and pain catastrophizing in patients with chronic pain,” Pain Med, vol. 25, no. 7, pp. 468–477, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Rosenberg, D. M. J. C. Rosenberg, D. M. Schultz, L. E. Duarte, S. M. Rosen, and A. Raza, “Increased pain catastrophizing associated with lower pain relief during spinal cord stimulation: Results from a large post-market study,” Neuromodulation, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 277–284; discussion 284, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. R. Pinto, T. McIntyre, R. Ferrero, A. Almeida, and V. Araújo-Soares, “Predictors of acute postsurgical pain and anxiety following primary total hip and knee arthroplasty,” J Pain, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 502–515, May 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. H. Høvik, S. B. Winther, O. A. Foss, and K. H. Gjeilo, “Preoperative pain catastrophizing and postoperative pain after total knee arthroplasty: A prospective cohort study with one year follow-up,” BMC Musculoskelet Disord, vol. 17, p. 214, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. S. Khan et al., “Catastrophizing: A predictive factor for postoperative pain,” Am J Surg, vol. 201, no. 1, pp. 122–131, Jan. 2011. [CrossRef]

- T. Teunis, A. G. J. T. Teunis, A. G. J. Bot, E. R. Thornton, and D. Ring, “Catastrophic Thinking Is Associated With Finger Stiffness After Distal Radius Fracture Surgery,” J Orthop Trauma, vol. 29, no. 10, pp. e414-420, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- E. Gibson and M. T. Sabo, “Can pain catastrophizing be changed in surgical patients? A scoping review,” Can J Surg, vol. 61, no. 5, pp. 311–318, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. L. Chimenti et al., “Elevated Kinesiophobia Is Associated With Reduced Recovery From Lower Extremity Musculoskeletal Injuries in Military and Civilian Cohorts,” Phys Ther, vol. 102, no. 2, p. pzab262, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Örücü Atar, Y. M. Örücü Atar, Y. Demir, E. Tekin, G. Kılınç Kamacı, N. Korkmaz, and K. Aydemir, “Kinesiophobia and associated factors in patients with traumatic lower extremity amputation,” Turk J Phys Med Rehabil, vol. 68, no. 4, pp. 493–500, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Roelofs, L. J. Roelofs, L. Goubert, M. Peters, J. Vlaeyen, and G. Crombez, “The Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia: Further examination of psychometric properties in patients with chronic low back pain and fibromyalgia,” EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PAIN, vol. 8, no. 5, Art. no. 5, 2004.

- G. Varallo et al., “Does Kinesiophobia Mediate the Relationship between Pain Intensity and Disability in Individuals with Chronic Low-Back Pain and Obesity?,” Brain Sci, vol. 11, no. 6, p. 684, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. Van Bogaert et al., “Influence of Baseline Kinesiophobia Levels on Treatment Outcome in People With Chronic Spinal Pain,” Phys Ther, vol. 101, no. 6, p. pzab076, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Saracoglu, M. I. Arik, E. Afsar, and H. H. Gokpinar, “The effectiveness of pain neuroscience education combined with manual therapy and home exercise for chronic low back pain: A single-blind randomized controlled trial,” Physiother Theory Pract, vol. 38, no. 7, pp. 868–878, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Malfliet et al., “Blended-Learning Pain Neuroscience Education for People With Chronic Spinal Pain: Randomized Controlled Multicenter Trial,” Phys Ther, vol. 98, no. 5, pp. 357–368, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Bodes Pardo, E. G. Bodes Pardo, E. Lluch Girbés, N. A. Roussel, T. Gallego Izquierdo, V. Jiménez Penick, and D. Pecos Martín, “Pain Neurophysiology Education and Therapeutic Exercise for Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Single-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial,” Arch Phys Med Rehabil, vol. 99, no. 2, pp. 338–347, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Kim and S. Lee, “Effects of pain neuroscience education on kinesiophobia in patients with chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Physical Therapy Rehabilitation Science, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 309–317, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Andias, M. R. Andias, M. Neto, and A. G. Silva, “The effects of pain neuroscience education and exercise on pain, muscle endurance, catastrophizing and anxiety in adolescents with chronic idiopathic neck pain: A school-based pilot, randomized and controlled study,” Physiother Theory Pract, vol. 34, no. 9, pp. 682–691, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L.-H. Lin, T.-Y. L.-H. Lin, T.-Y. Lin, K.-V. Chang, W.-T. Wu, and L. Özçakar, “Pain neuroscience education for reducing pain and kinesiophobia in patients with chronic neck pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials,” European Journal of Pain, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 231–243, 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Wood et al., “Pain catastrophising and kinesiophobia mediate pain and physical function improvements with Pilates exercise in chronic low back pain: A mediation analysis of a randomised controlled trial,” Journal of Physiotherapy, vol. 69, no. 3, pp. 168–174, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Savych, D. B. Savych, D. Neumark, and R. Lea, “Do Opioids Help Injured Workers Recover and Get Back to Work? The Impact of Opioid Prescriptions on Duration of Temporary Disability,” Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, vol. 58, no. 4, Art. no. 4, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Grattan, M. D. Sullivan, K. W. Saunders, C. I. Campbell, and M. R. Von Korff, “Depression and Prescription Opioid Misuse Among Chronic Opioid Therapy Recipients With No History of Substance Abuse,” Ann Fam Med, vol. 10, no. 4, Art. no. 4, Jul. 2012. [CrossRef]

- F. Scherrer et al., “The Prescription Opioids and Depression Pathways Cohort Study,” J Psychiatr Brain Sci, vol. 5, 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Scherrer et al., “Characteristics of new depression diagnoses in patients with and without prior chronic opioid use,” J Affect Disord, vol. 210, pp. 125–129, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. W. S. Vlaeyen, G. J. W. S. Vlaeyen, G. Crombez, and S. J. Linton, “The fear-avoidance model of pain,” PAIN, vol. 157, no. 8, p. 1588, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Vogel, K. L. J. A. Vogel, K. L. Rising, J. Jones, M. L. Bowden, A. A. Ginde, and E. P. Havranek, “Reasons Patients Choose the Emergency Department over Primary Care: A Qualitative Metasynthesis,” J Gen Intern Med, vol. 34, no. 11, pp. 2610–2619, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Rogers and S. G. Farris, “A meta-analysis of the associations of elements of the fear-avoidance model of chronic pain with negative affect, depression, anxiety, pain-related disability and pain intensity,” Eur J Pain, vol. 26, no. 8, pp. 1611–1635, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. L. Zale and J. W. Ditre, “Pain-Related Fear, Disability, and the Fear-Avoidance Model of Chronic Pain,” Curr Opin Psychol, vol. 5, pp. 24–30, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- V. J. Felitti et al., “Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study,” Am J Prev Med, vol. 14, no. 4, Art. no. 4, May 1998. [CrossRef]

- V. Tidmarsh, R. V. Tidmarsh, R. Harrison, D. Ravindran, S. L. Matthews, and K. A. Finlay, “The Influence of Adverse Childhood Experiences in Pain Management: Mechanisms, Processes, and Trauma-Informed Care,” Front Pain Res (Lausanne), vol. 3, p. 923866, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. E. Fordyce, J. L. W. E. Fordyce, J. L. Shelton, and D. E. Dundore, “The modification of avoidance learning pain behaviors,” J Behav Med, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 405–414, Dec. 1982. [CrossRef]

- J. Schmidt, “Cognitive factors in the performance level of chronic low back pain patients,” J Psychosom Res, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 183–189, 1985. [CrossRef]

- S. Rachman and C. Lopatka, “Accurate and inaccurate predictions of pain,” Behaviour Research and Therapy, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 291–296, Jan. 1988. [CrossRef]

- S. Rubak, A. S. Rubak, A. Sandbæk, T. Lauritzen, and B. Christensen, “Motivational interviewing: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Br J Gen Pract, vol. 55, no. 513, pp. 305–312, Apr. 2005.

- F. Webster et al., “Patient Responses to the Term Pain Catastrophizing: Thematic Analysis of Cross-sectional International Data,” The Journal of Pain, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 356–367, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- U. P. Foundation, “‘Catastrophizing’: A form of pain shaming,” U.S. Pain Foundation. Accessed: Jul. 24, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://uspainfoundation.org/blog/catastrophizing-a-form-of-pain-shaming/.

- Atkins and, K. Mukhida, “The relationship between patients’ income and education and their access to pharmacological chronic pain management: A scoping review,” Can J Pain, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 142–170. [CrossRef]

- S. Maharaj, N. V. S. Maharaj, N. V. Bhatt, and J. P. Gentile, “Bringing It in the Room: Addressing the Impact of Racism on the Therapeutic Alliance,” Innov Clin Neurosci, vol. 18, no. 7–9, pp. 39–43, 2021.

- H. Strand et al., “Racism in Pain Medicine: We Can and Should Do More,” Mayo Clinic Proceedings, vol. 96, no. 6, pp. 1394–1400, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Amtmann et al., “The Concerns About Pain (CAP) Scale: A Patient-Reported Outcome Measure of Pain Catastrophizing,” The Journal of Pain, vol. 21, no. 11, pp. 1198–1211, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. J. L. Sullivan and D. A. Tripp, “Pain Catastrophizing: Controversies, Misconceptions and Future Directions,” The Journal of Pain, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 575–587, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. N. Raja et al., “The Revised IASP definition of pain: Concepts, challenges, and compromises,” Pain, vol. 161, no. 9, pp. 1976–1982, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- “U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2019, May). Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force Report: Updates, Gaps, Inconsistencies, and Recommendations. Retrieved from U. S. Department of Health and Human Services website: https://www.hhs.gov/ash/advisory-committees/pain/reports/index.html”.

- D. J. Bean, A. D. J. Bean, A. Dryland, U. Rashid, and N. L. Tuck, “The Determinants and Effects of Chronic Pain Stigma: A Mixed Methods Study and the Development of a Model,” The Journal of Pain, vol. 23, no. 10, pp. 1749–1764, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Licciardone, Y. J. C. Licciardone, Y. Tran, K. Ngo, D. Toledo, N. Peddireddy, and S. Aryal, “Physician Empathy and Chronic Pain Outcomes,” JAMA Network Open, vol. 7, no. 4, p. e246026, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Zaman and J. Striebel, “Opioid Refugees: A Diverse Population Continues to Emerge,” p. 16. csamnews_fall2015_v41_n1.pdf.

- “Opioid refugees: How the fentanyl crisis led to a backlash against doctors that’s leaving people in pain,” The Georgia Straight. Accessed: May 06, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.straight.com/news/1043911/opioid-refugees-how-fentanyl-crisis-led-backlash-against-doctors-thats-leaving-people.

- “[Report] | The Pain Refugees, by Brian Goldstone,” Harper’s Magazine. Accessed: May 06, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://harpers.org/archive/2018/04/the-pain-refugees/.

- S. E. Burke et al., “Do Contact and Empathy Mitigate Bias Against Gay and Lesbian People Among Heterosexual Medical Students? A Report from Medical Student CHANGES,” Acad Med, vol. 90, no. 5, pp. 645–651, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elsayed, A. M. Heyer, and M. E. Schatman, “Disparities in the Treatment of the LGBTQ Population in Chronic Pain Management,” J Pain Res, vol. 14, pp. 3623–3625, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. D. Bailey, N. Z. D. Bailey, N. Krieger, M. Agénor, J. Graves, N. Linos, and M. T. Bassett, “Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions,” Lancet, vol. 389, no. 10077, pp. 1453–1463, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- W. J. Hall et al., “Implicit Racial/Ethnic Bias Among Health Care Professionals and Its Influence on Health Care Outcomes: A Systematic Review,” Am J Public Health, vol. 105, no. 12, pp. e60-76, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Cate Polacek et al., “Healthcare Professionals’ Perceptions of Challenges to Chronic Pain Management,” vol. 26, Apr. 2020, Accessed: Aug. 05, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ajmc.com/view/healthcare-professionals-perceptions-of-challenges-to-chronic-pain-management.

- R. Atkins, “INSTRUMENTS MEASURING PERCEIVED RACISM/RACIAL DISCRIMINATION: REVIEW AND CRITIQUE OF FACTOR ANALYTIC TECHNIQUES,” International journal of health services : Planning, administration, evaluation, vol. 44, no. 4, p. 711, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Wang and O. Jacobs, “From Awareness to Action: Pathways to Equity in Pain Management,” Health Equity, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 416–418, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Edgoose, M. J. Edgoose, M. Quiogue, and K. Sidhar, “How to Identify, Understand, and Unlearn Implicit Bias in Patient Care,” fpm, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 29–33, Jul. 2019.

- F. Perugino, V. F. Perugino, V. De Angelis, M. Pompili, and P. Martelletti, “Stigma and Chronic Pain,” Pain Ther, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 1085–1094, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Linton, K. S. J. Linton, K. Boersma, K. Vangronsveld, and A. Fruzzetti, “Painfully reassuring? The effects of validation on emotions and adherence in a pain test,” Eur J Pain, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 592–599, Apr. 2012. [CrossRef]

- D. Koesling and C. Bozzaro, “Chronic pain patients’ need for recognition and their current struggle,” Med Health Care Philos, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 563–572, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Hanssen, M. L. M. M. Hanssen, M. L. Peters, J. W. S. Vlaeyen, Y. M. C. Meevissen, and L. M. G. Vancleef, “Optimism lowers pain: Evidence of the causal status and underlying mechanisms,” Pain, vol. 154, no. 1, pp. 53–58, Jan. 2013. [CrossRef]

- P. Forum, “COVID-19 Pandemic Impact on Patients, Families & Individuals in Recovery from a SUD,” APF. Accessed: Jun. 15, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.addictionpolicy.org/post/covid-19-pandemic-impact-on-patients-families-individuals-in-recovery-fromsubstance-use-disorder.

- L. Goubert, G. L. Goubert, G. Crombez, and S. Van Damme, “The role of neuroticism, pain catastrophizing and pain-related fear in vigilance to pain: A structural equations approach,” PAIN, vol. 107, no. 3, p. 234, Feb. 2004. [CrossRef]

- B. R. Levy, M. D. B. R. Levy, M. D. Slade, S. R. Kunkel, and S. V. Kasl, “Longevity increased by positive self-perceptions of aging,” J Pers Soc Psychol, vol. 83, no. 2, pp. 261–270, Aug. 2002. [CrossRef]

- J. B. Yamin, S. M. J. B. Yamin, S. M. Meints, and R. R. Edwards, “Beyond pain catastrophizing: Rationale and recommendations for targeting trauma in the assessment and treatment of chronic pain,” Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 231–234, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Maly and A., H. Vallerand, “Neighborhood, Socioeconomic, and Racial Influence on Chronic Pain,” Pain Manag Nurs, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 14–22, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- “Cognitive restructuring: Steps, technique, and examples.” Accessed: Mar. 19, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/cognitive-restructuring.

- M. G. Newman, T. M. G. Newman, T. Erickson, A. Przeworski, and E. Dzus, “Self-help and minimal-contact therapies for anxiety disorders: Is human contact necessary for therapeutic efficacy?,” J Clin Psychol, vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 251–274, Mar. 2003. [CrossRef]

- E. Mayo-Wilson and P. Montgomery, “Media-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy and behavioural therapy (self-help) for anxiety disorders in adults,” Cochrane Database Syst Rev, no. 9, p. CD005330, Sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- “Somatoform Disorders | AAFP.” Accessed: Aug. 07, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2007/1101/p1333.html.

- “Catastrophizing misinterpretations predict somatoform-related symptoms and new onsets of somatoform disorders - ScienceDirect.” Accessed: Aug. 07, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022399915300271.

- H. Seto and M. Nakao, “Relationships between catastrophic thought, bodily sensations and physical symptoms,” Biopsychosoc Med, vol. 11, p. 28, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Schütze, C. R. Schütze, C. Rees, A. Smith, H. Slater, J. M. Campbell, and P. O’Sullivan, “How Can We Best Reduce Pain Catastrophizing in Adults With Chronic Noncancer Pain? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” The Journal of Pain, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 233–256, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

| Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire—Work and Physical Activity (FAB-Wand PA)[11,17,31] | Two subscales (FAB-W: 0-42; FAB-PA 0-24) in which higher scores indicate more severe pain and disability due to fear avoidance beliefs about work and physical activity, respectively. Various score thresholds have been documented as associated with clinical relevancy and specific negative chronicity of CNCP. Higher scores have been associated with poor physical and manual therapy results and low return to work rates after an injury. |

| Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TKS)[32,33] | A measure of fear of movement and reinjury. Scores range from 17–68, with higher scores being of higher severity. Higher TKS scores have been correlated with higher disability and pain scores. |

| Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS)[19,34,35] | Assesses levels of catastrophizing. In initial validation, a score of 30 or more correlated with high unemployment, self-declared “total” disability, and clinical depression. However, various lower score thresholds have been documented as associated with clinical relevancy for specific negative chronicity of CNCP. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).