1. Introduction

Population aging is a worldwide reality. This phenomenon is caused by an increased average life expectancy, which derives from medical progress and significant improvements in living conditions (quality of housing, sanitary and hygiene conditions, information on healthy lifestyles, diet and access to health care) [

1]. At the same time, different ways of preventing diseases/complications have also emerged, including preventive therapeutic vaccines, complementary diagnostic means, and rehabilitation therapies. These circumstances allow individuals to survive longer and reach more advanced ages, thus enhancing the development of chronic diseases (e.g., osteoarticular, cardiovascular, neurological, respiratory, renal, neoplastic) [

2].

It is estimated that, by 2050, one in six people will be 65 years or older, and part of the elderly population may develop a chronic disease condition [

3]. This trend has considerable implications for various spheres of society, particularly for the social, economic and health domains, given that age is the main risk factor for disabling conditions (e.g., cancer, cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative diseases, osteoarticular diseases) [

3]. Most people over the age of 65 have, at least, one chronic condition, and often two or more [

4].

Therefore, as regards the development of health policies, demographic ageing and the consequent increase in the prevalence of chronic diseases are major challenges [

5]. In the 21

st century, societies in general, and nurses in particular, should focus on promoting a healthy ageing process, based on dignity, comfort and quality of life [

3]. Hence, it is vital to look at aging with a more preventive view, to promote health, autonomy, comfort and quality of life, especially for those who are hospitalized and facing an important transitional phase in their lives.

Comfort is perceived as a central concept in nursing (both in research and in clinical practice), being also the desirable outcome of care provision. Nevertheless, its conceptualization is not yet consensual, since it is a complex concept that varies according to the individuals, contexts and relationships in question [

6]. As it refers to a situational and circumstantial context, its meaning is immediate and dynamic, deriving from several aspects: the experienced circumstances, intrinsic factors that are present in the relationship with oneself, and the individual’s interactions with others/the environment/society [

7,

8]. On the other hand, experiencing comfort is a positive phenomenon that goes beyond the relief of discomfort – it is an immediate state, which is felt in different domains: physical, environmental, social and psycho-spiritual [

9,

10].

In 2018, Veludo defined the concept of comfort as a sensation, by reviewing the available literature (108 articles) and performing a hermeneutical data analysis. Regarding the concept’s central components, the following aspects were identified: as antecedents – any experience that an individual may undergo, as a result of physical, psycho-spiritual, socio-cultural, or environmental, interactions; as attributes – security, control, realization of oneself, belonging, peace and plenitude, relaxation, and normality of life; as consequences – it strengthens the individuals (increasing their ability to deal with life’s adversities), allows a peaceful death and improves institutional results [

9,

11].

In the experience of the hospitalized elderly individual, the process of comforting care is based on a multi-systemic and multi-factorial interaction between the involved elements. This interaction is influenced by the care context, being connected with the manners/means used for comforting, as well as each element’s conceptions of comfort/non-comfort. In the interaction between the nurse, the elderly patient and his/her family, the nurse’s integrative and intentional action is decisive in meeting the elderly patient’s comfort needs. The comfort needs perceived by the elderly are related to changes in the health/disease process, attitudes towards “oneself and life”, the service’s structure/functioning, and family/significant people [

12]. Hospitalization and the confrontation with illness compel the elderly to restructure their reference system and reshape their attitude towards life. As a privileged comfort actor, the nurse’s comforting intervention must be based on respect, considering the Other’s singularity and needs [

12,

13].

Comforting care is defined as a social, multi-contextual, integrative, individualized and subjective process, which encompasses multiple dynamic variables, following a logic of commitment, intentionality, mutuality and continuity. It employs a comprehensive model to accompany the elderly patient, considering the entirety of the caregiver and the entirety of the care recipient. As previously mentioned, being based on an encounter/interaction between the involved actors, it is influenced by the care context, where two significant cultural domains emerge, which relate not only to the manners/means used for comforting, but also to the conceptions of comfort/non-comfort [

12]. When interacting with the elderly individual and his/her family, the nurse must consider the patient’s dependence, fragility and increased vulnerability. Hence, the nurse must acknowledge all the existing socio-affective changes and implications, to successfully carry out the proposed health project.

The process of comforting care stems from the context’s specific environment combined with the characteristics and actions constructed by the participating actors [

8]. In this sense, Kolcaba stresses that comfort-promoting interventions should be considered a good practice in nursing care only when the intervention in question is perceived as comforting by the targeted individual, family, or community [

9].

Given the reality described above, we decided to conduct a research effort, which aimed to explore the nursing interventions that promote comfort among the elderly in hospital settings.

2. Materials and Methods

The present work depicts a mixed descriptive exploratory study. The collected qualitative data was subjected to a content analysis, performed according to Bardin’s recommendations [

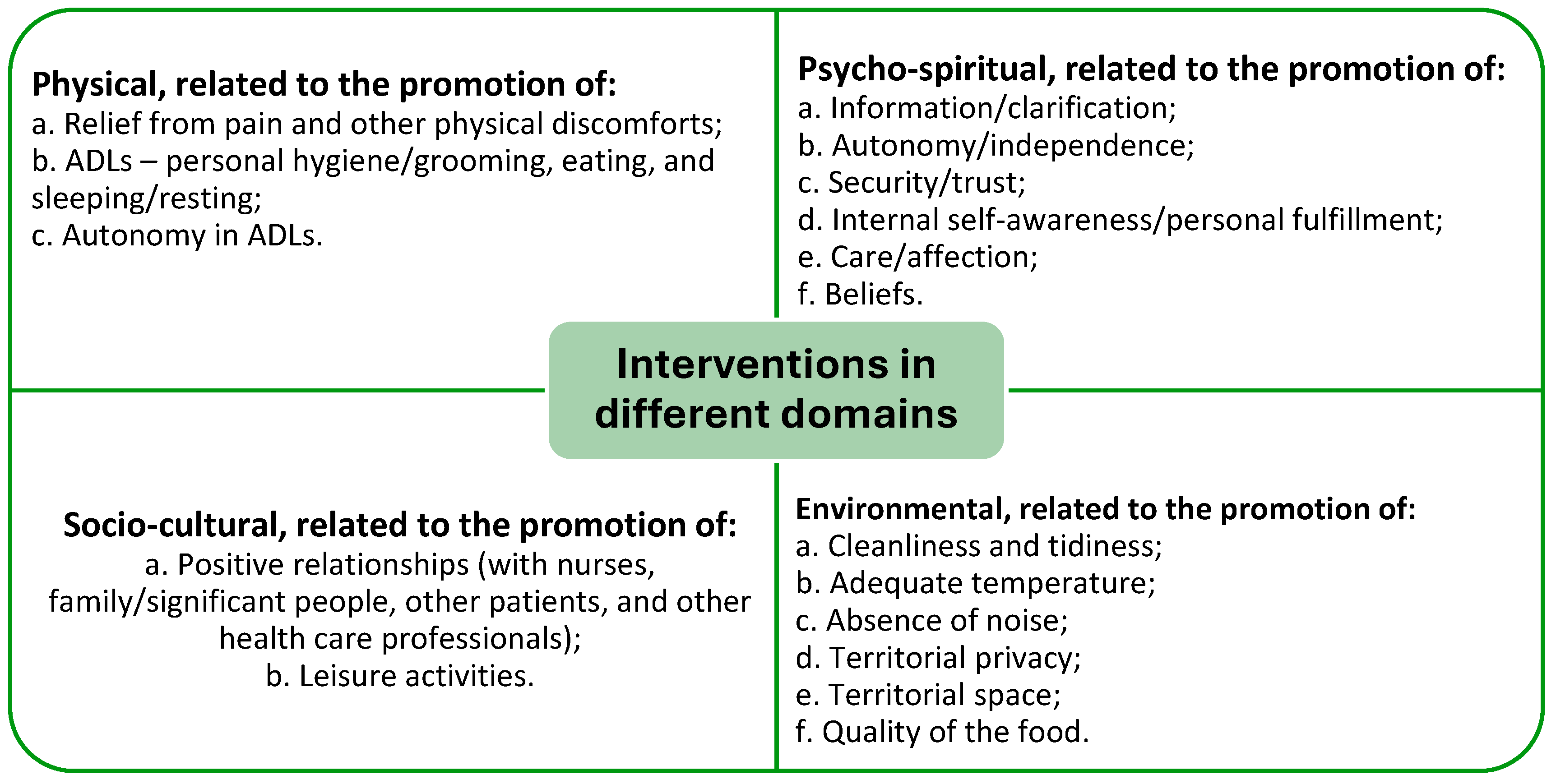

14]. A purely deductive approach was adopted, using the dimensions already defined by Kolcaba: physical, psycho-spiritual, socio-cultural and environmental [

9]. The study followed the guidelines of the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) [

15].

To obtain descriptive statistics, the quantitative data was processed using version 26.0 of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software for Windows.

The study’s target population consisted of individuals with 65 years of age or more, who had been admitted to the medical service of a public hospital located in the Lisbon area. We opted for an intentional non-probability sampling technique, based on a conscious choice to include/exclude the elements according to their characteristics [

16]. As such, the following inclusion criteria were established: elderly (aged 65 or over); suffering from a chronic illness; ability to speak/understand Portuguese; cognitive ability for self-assessment (Mini Mental State Examination: > 15 points for illiterate patients, > 22 points for patients with up to 11 years of schooling, and > 27 points for patients with more than 11 years of schooling); hospitalized for more than 24 hours (in order to have a better perception of the comforting interventions in the studied context); freely consented to participate in the study. The individuals were selected by the researcher, who always verified their willingness to participate, through an initial introductory dialog.

The sample’s final size and composition were determined by data saturation, during the analysis process, taking into consideration the richness of the individual experience and the attainment of information redundancy without adding new data [

17]. Based on the defined objectives, we designed a questionnaire, which included the sample’s socio-demographic variables (gender, age, marital status, educational/academic qualifications, profession/occupation, residence/current permanence), as well as clinical variables (history of chronic illness). It also comprised two questions: the first was closed and appraised the participant’s comfort level (using a Likert Scale from zero to 10, where zero represented the absence of comfort and 10 represented total comfort), while the second was open and related to the aspects that, at the time, gave/could give more comfort to the participant.

To ensure that the questions were understandable, and to ascertain the answers’ average length, the questionnaire was subjected to a pre-test, conducted on individuals of the target population who did not participate in the study.

As required, the study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of Universidade Católica Portuguesa (Approval no. 91/2020). All the ethical principles defined in the international Helsinki convention were safeguarded, ensuring respect for each individual and his/her self-determination. Before carrying out the survey, the researcher provided sufficient information to the participants regarding the study’s purpose, the intended use for the collected data, and data protection. A free consent was obtained from all participants, by means of a consent form.

4. Discussion

In the context under study, according to the logic of individual-centered care, comfort requires identifying, from the elderly’s point of view, the different manners/means of comforting (what brings, or could bring, more comfort). This allows the discovery of nursing interventions that are comforting for the target population. As such, healthcare organizations and their professionals must acknowledge the individuals’ experiences and values, recognizing the patients’ complexity and uniqueness. Consequently, the patient must be viewed as a care partner, to co-construct care [

18].

Our findings systematize the comfort experience in the context of hospitalization, considering the transition lived by the elderly in such settings. Once we had extracted the meaning units from the statements, we grouped those corresponding to each category/subcategory, according to their semantic value. The participants identified various manners/means of comforting that, acting simultaneously, gave rise to the feeling of comfort experienced at the moment. The reported manners/means were related to physical, psycho-spiritual, socio-cultural and environmental interventions, which fit into the four contexts of Kolcaba’s theory [

9]. It is evident that these four antecedents of comfort – which originate within the individual, or result from the intervention of others – constitute the source of the sensation [

11].

By analyzing the obtained results, we found that many of the statements about the manners/means of comforting were worded negatively, showing that the absence of certain elements promotes comfort. Nonetheless, the available literature is unanimous in considering that the concept of comfort can be associated with a state of relief/encouragement, rather than the absence of any discomfort, thus acquiring a positive connotation [

9,

19].

In the

physical domain, the experience/meaning of comfort is related to the relief from pain and other physical discomforts, ADLs, and autonomy to perform the latter. In this sense, comfort is viewed as the result of an intentional action, centered on the control/absence of pain and other physical discomforts, which are thus considered synonymous [

20]. Nursing interventions should focus on recognizing the individuality of the suffering experience. Therefore, the nurse’s actions should be guided by the possibility of helping the patient to achieve a state of relief/absence of pain, while also promoting the patient’s autonomy in satisfying his/her basic human needs [

8].

Hospitalization generates feelings of uncertainty in the elderly and their families, triggering high levels of anxiety and concern. It is an unpredictable situation, which causes insecurity and fear [

21]. Such circumstances usually have a strong impact on the

psycho-spiritual domain, requiring a process of adaptation. They are a source of suffering, deeply marked by emotional instability. Our findings are in line with those obtained by Wensley [

13], revealing that psycho-spiritual interventions should be related to providing information/clarification, as well as promoting autonomy/independence, security/trust, internal self-awareness/personal fulfillment, care/affection, and beliefs.

The communication process is involved in the comforting construction, being a key factor in the interaction. It allows the development of a therapeutic relationship with the patients and their families, which promotes the situation’s understanding. Providing information and clarification regarding the patient’s clinical status, in a rigorous and up-to-date manner, allows the patient to have more control over the provided care and facilitates his/her adaptation to the experienced circumstances [

22]. While constructing a comforting intervention, it is important to include pertinent information, according to the needs and concerns expressed by the patient, since the lack of knowledge generates insecurity and uncertainty [

13]. Information is the basis for the patient’s autonomous decisions, allowing the individual to consent to, or refuse, the proposed health measures/procedures [

10]. With respect to comforting care, verbal and non-verbal communication is a fundamental tool, which requires nurses to be empathetic and close to their patients, to interact with them and establish a partnership [

23].

The importance of promoting autonomy/independence is widely acknowledged, since it has a major influence on the individuals’ dignity, integrity and freedom, being also a central component of their general well-being [

24]. In hospitalization settings, the individual may become more fragile, existing a clear need for care that seeks to maintain autonomy, to stimulate the individual’s abilities. Accordingly, the patient should actively participate in the care provision process, in a manner as much independent as possible [

13].

Still in the psycho-spiritual domain, Kolcaba recognizes the significance of internal self-awareness/personal fulfillment, which encompasses self-esteem, the meaning of life, sexuality, the concept of oneself, and the relationship with a higher being [

9]. Given that the inner strength of each individual is crucial for a positive day-to-day experience, its promotion is essential to safeguard human dignity [

9].

The elderly value displays of care and affection from nurses/significant people (e.g., tenderness, friendship, love, understanding, concern, attention, humanism, respect). For the elderly, relational attitudes associated with care and affection are human qualities that promote comfort [

8]. This reinforces how nursing care is built within the context of an encounter between the individual and the nurse/significant person.

Spiritual interventions make sense in terms of promoting beliefs and values. They emerge in an attempt to facilitate a balanced and meaningful life [

13]. Each individual, when confronted with his/her own existence, more specifically with disease and hospitalization, adopts a kind of spirituality, or a particular way of being, which allows him/her to cope better with problems [

25]. The expression of spirituality is related to the individuality of each elderly person. It provides an inner strength that gives meaning and significance to life [

13].

In the

socio-cultural domain, the results highlight interpersonal, family and social relationships, which exert a positive influence and generate comfort [

9]. Comforting relationships can come from a variety of sources (e.g., nurses, doctors, other health care professionals, family members, significant people), depending on the felt needs, or the circumstances of the moment [

26]. In this sense, in an intentional search for the uniqueness/particularity of each elderly individual, the following main predictors of comfort emerge: availability, trust, provided information, acknowledgment as a person, closeness, presence, showing interest, sympathy, and the implementation of non-routine interventions [

26,

27]. Maintaining positive relationships with family and friends makes the individuals feel cared for, loved, esteemed, valued and supported, giving them a sense of belonging [

8].

Establishing an authentic relationship that promotes the situation’s understanding allows a humanized aid, through an appropriate response, adapted to the experienced circumstances. This help can be mobilized by nurses, using the social support network, offering emotional support, and providing information to family members [

23].

Occupying the period of hospitalization with leisure activities, which facilitate distraction/recreation, diminishes the patient’s suffering [

28], and promotes psycho-spiritual and socio-cultural comfort [

12]. In this context, leisure has several purposes: distraction, rest, stress reduction, energy renewal, and recreation [

28]. The present study highlights the following comfort-promoting activities: listening to music, watching television and reading. These activities seem to minimize the undesirable effects of hospitalization, being, therefore, beneficial to health. They contribute to the reduction of pain and anxiety, while increasing the individuals’ well-being and comfort [

10,

29].

Focusing on organizational, structural and operational conditions, environmental interventions are related to the humanization of the hospital’s physical environment. As such, in the

environmental domain, the following aspects stand out: cleanliness and tidiness (bed and room); adequate temperature; absence of noise; privacy (space, room and bathroom); territorial space (view from the room); and quality of the food (taste, appearance, being healthy). Structural and organizational deficiencies, particularly those associated with environmental conditions (e.g., light, noise, equipment/furniture, color, temperature, natural/artificial elements), are mentioned in other studies as comfort-limiting factors that fall outside of the nurse’s direct intervention [

9,

12,

19]. However, these deficiencies do not hinder the construction of comforting actions, which allows the humanization of care and the fulfillment of the elderly’s needs [

12].

4.1. Study Limitations

The conclusions must be interpreted considering the context in question (i.e., the circumstances in which the data was collected). The decision to recruit participants in a hospital setting granted easy access to the population, in a safe and controlled environment. However, the restriction to a single institution and the choice of a questionnaire, rather than recorded interviews, affected the number of participants and their answers.

Nevertheless, we consider that this study is a valid contribution, allowing for future research in other similar contexts. It also paves the way for the identification and validation of comforting nursing interventions.

4.2. Implications for Practice

The obtained results allowed the gathering of knowledge about several manners/means of comforting the hospitalized elderly, contextualized in nursing interventions that promote comfort. The study’s findings suggest the need for further research, with a larger number of participants and using other methods, namely observation and interviews, in order to define interventions capable of promoting comfort in the studied conditions. In this sense, we stress the importance of structured interventions that respect the elderly’s individuality, their life context, and their expectations/projects.