Submitted:

23 August 2024

Posted:

26 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Camu Camu Extract (CCX)

2.3. Preparation of the Polymer Solution

2.4. EAPG Process

2.5. Microscopy

2.6. Assessment of the Stability of CCX Formulations

2.7. Total Soluble Polyphenols

2.8. Antioxidant Activity

2.9. Attenuated Total Reflection- Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR)

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

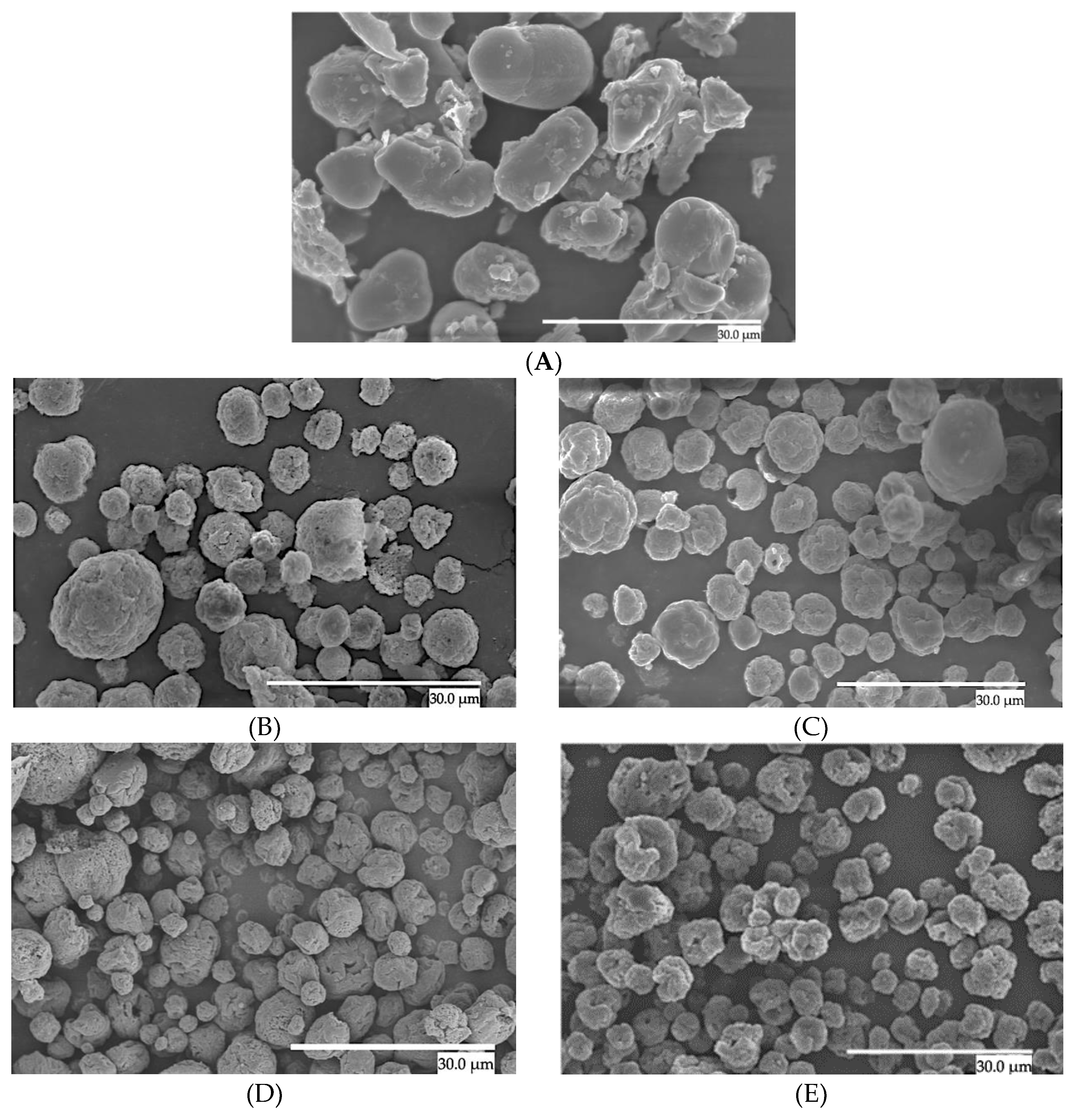

3.1. Morphology

3.2. Characterization of Antioxidant Activity and the Polyphenol Content

3.3. Storage Stability

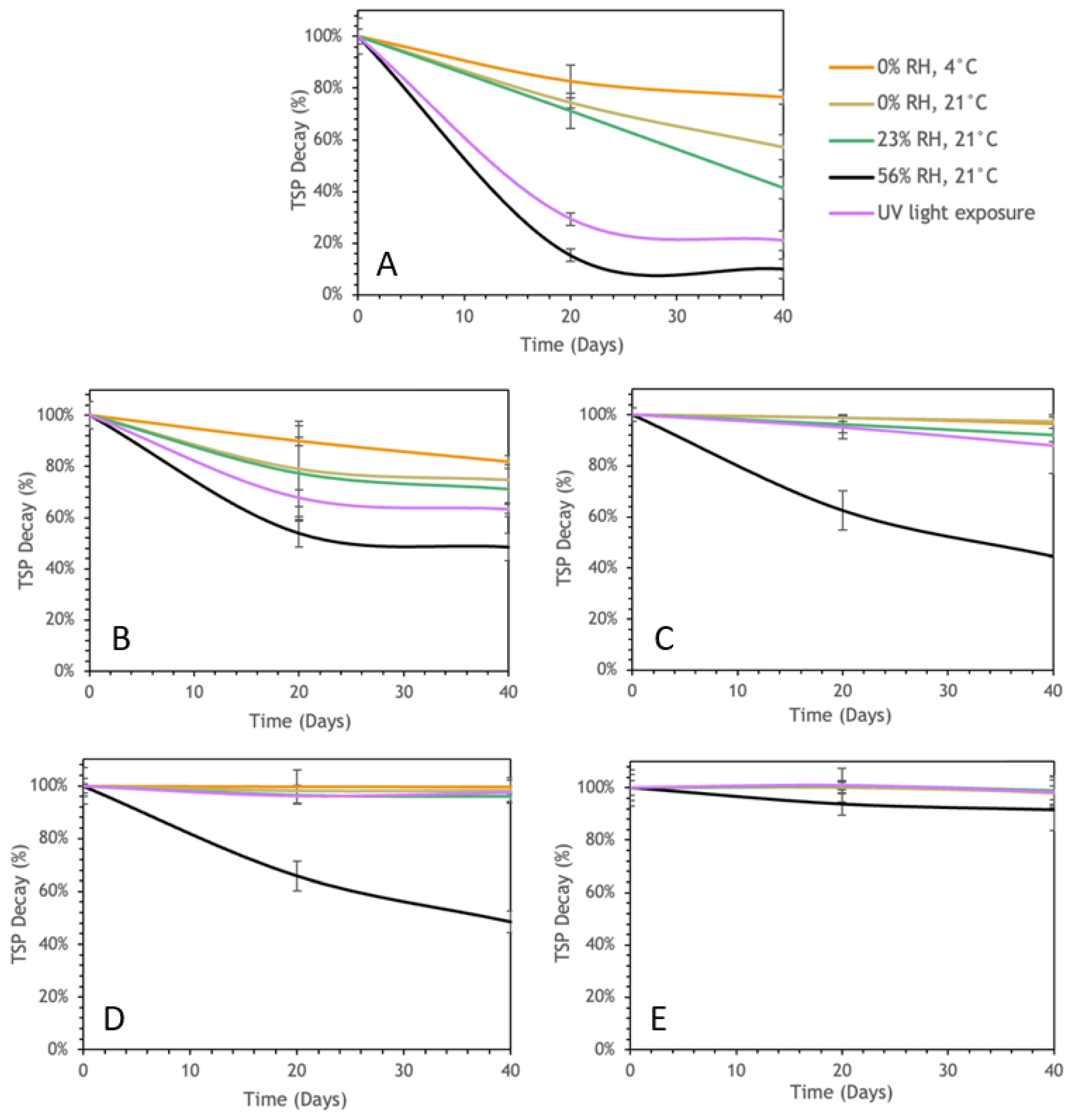

3.3.1. Polyphenol Content Stability

3.3.2. IP-DPPH Storage Stability

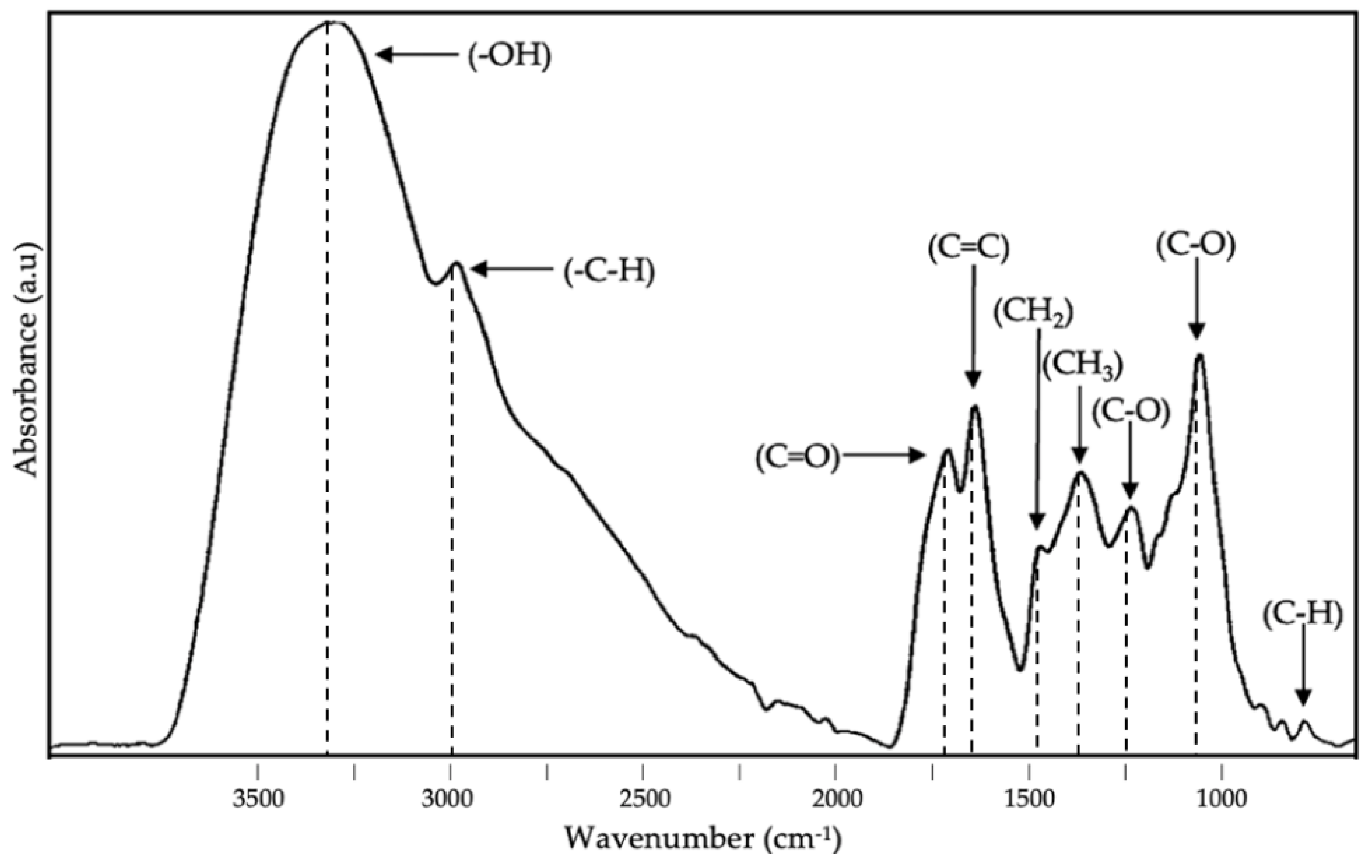

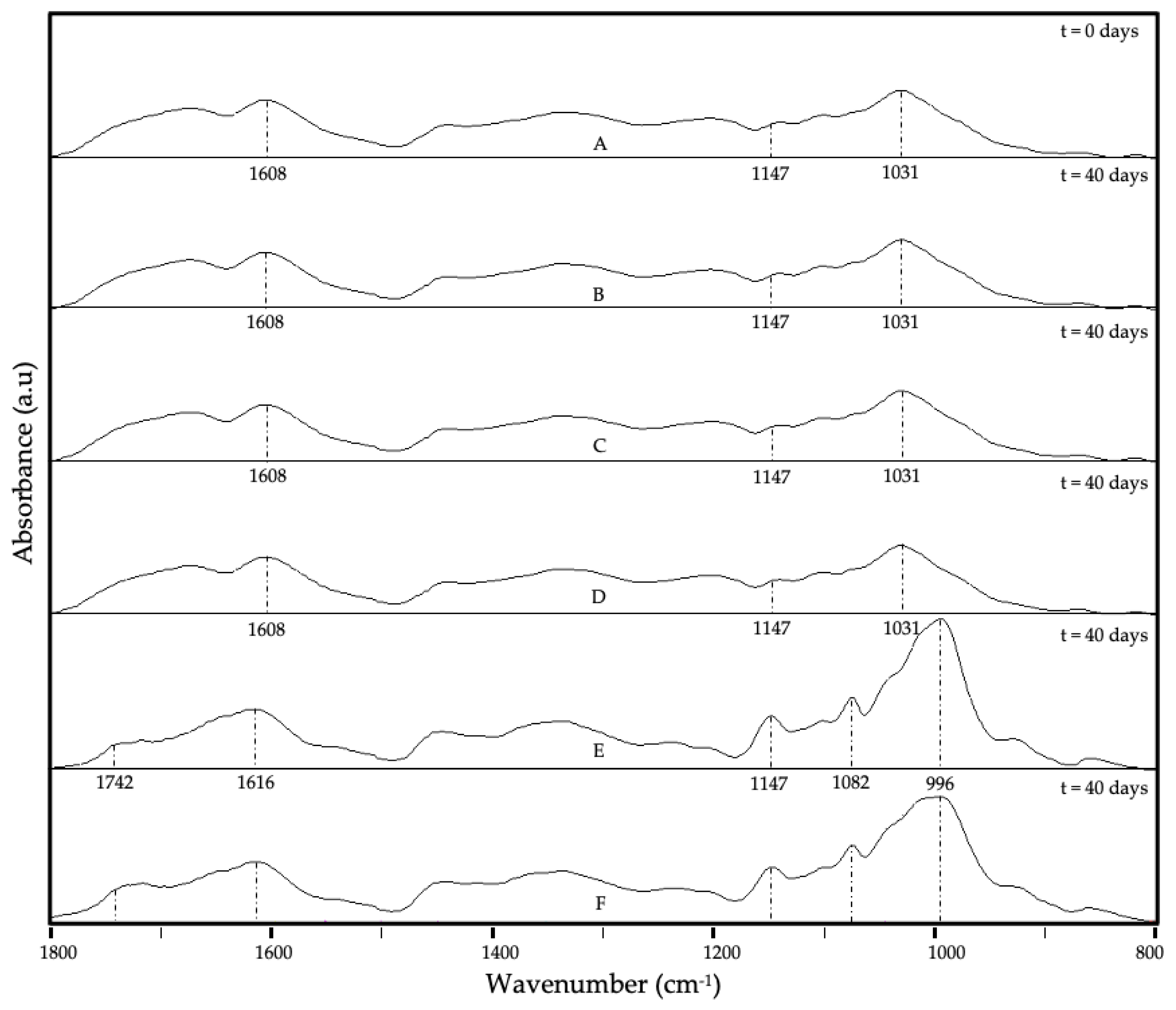

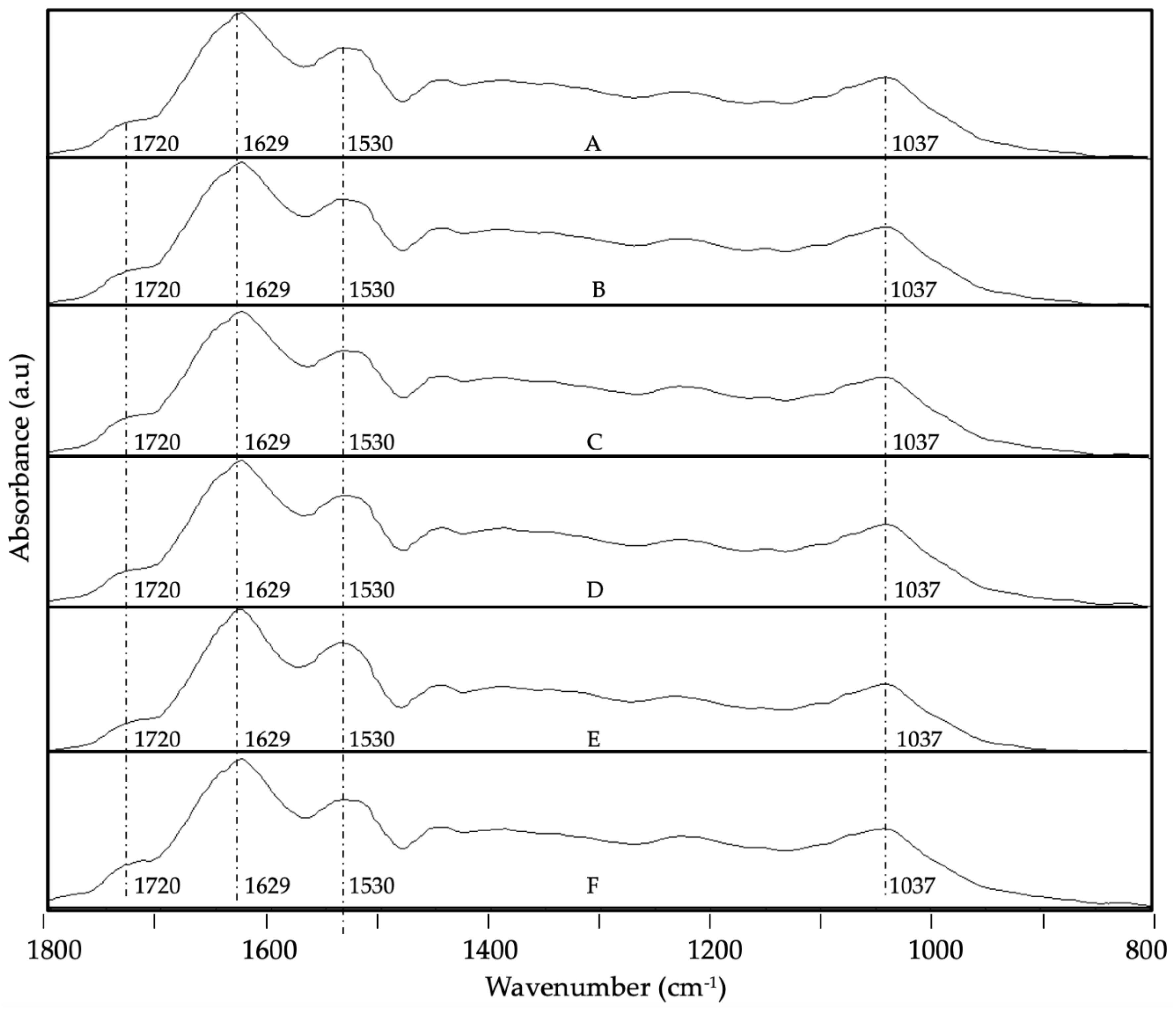

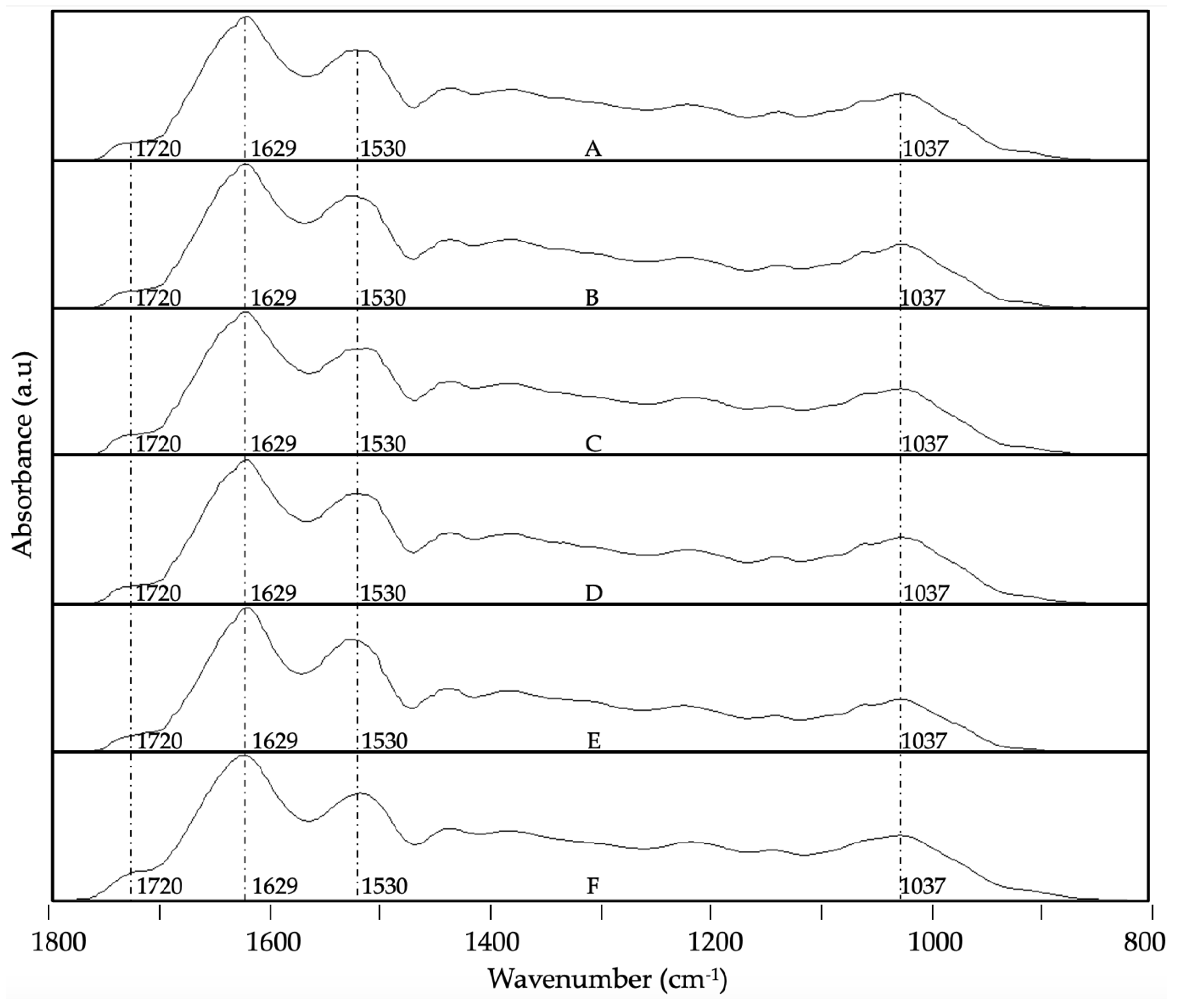

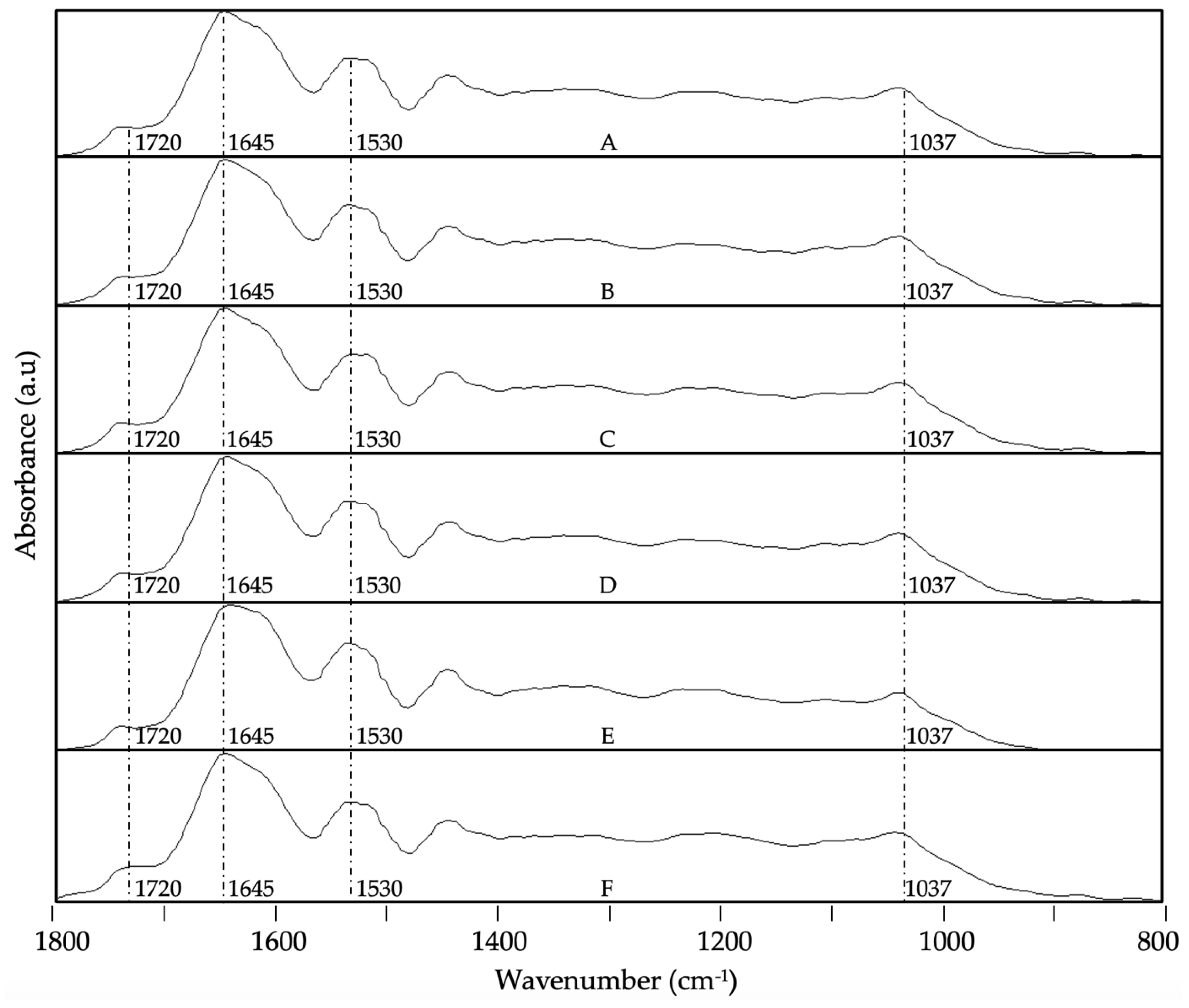

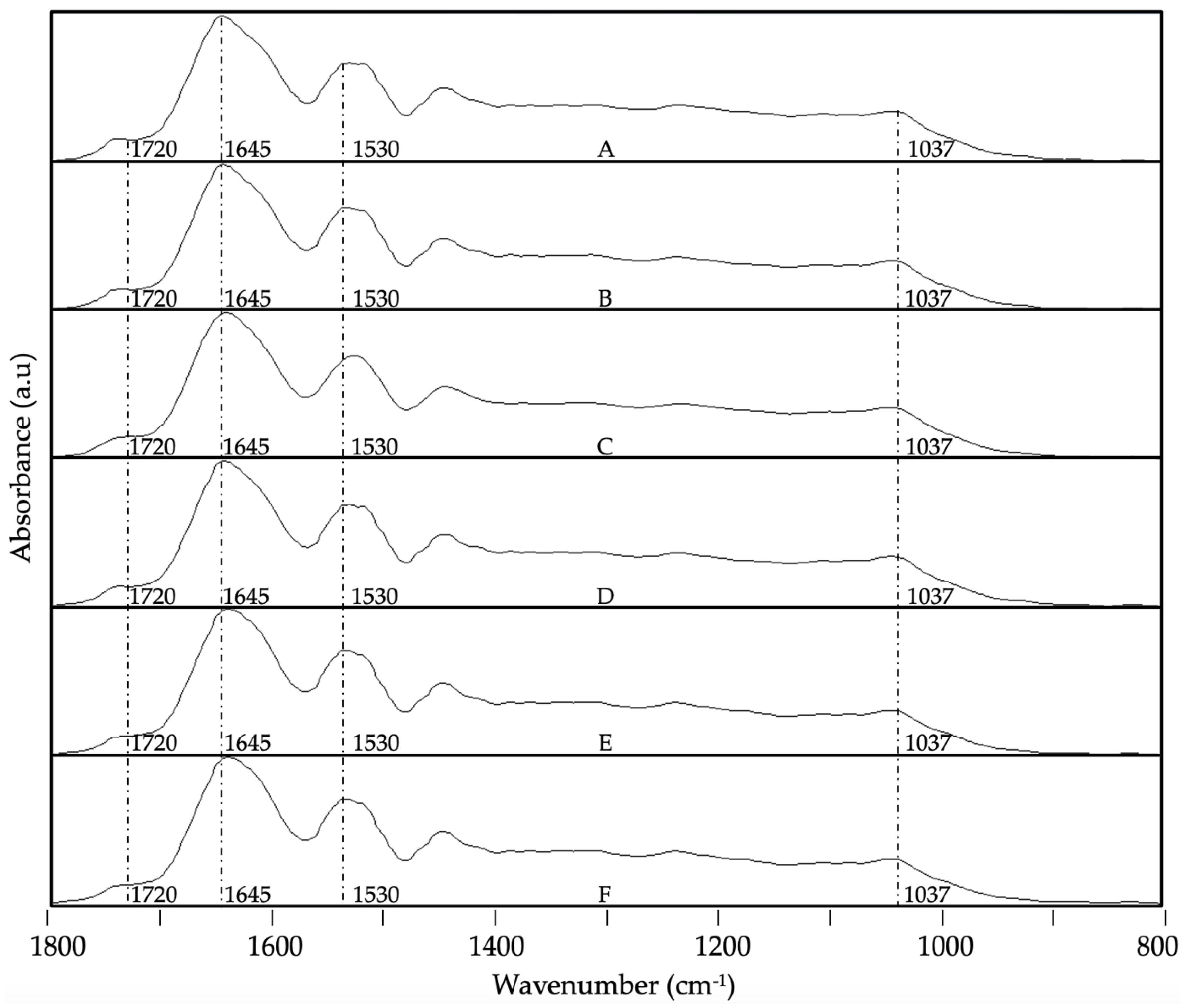

3.4. ATR-FTIR Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Alu’datt, M.H.; Alrosan, M.; Gammoh, S.; Tranchant, C.C.; Alhamad, M.N.; Rababah, T.; Zghoul, R.; Alzoubi, H.; Ghatasheh, S.; Ghozlan, K.; et al. Encapsulation-Based Technologies for Bioactive Compounds and Their Application in the Food Industry: A Roadmap for Food-Derived Functional and Health-Promoting Ingredients. Food Biosci 2022, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcillo-Parra, V.; Tupuna-Yerovi, D.S.; González, Z.; Ruales, J. Encapsulation of Bioactive Compounds from Fruit and Vegetable By-Products for Food Application – A Review. Trends Food Sci Technol 2021, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M.; Singh, K.; Khedkar, R. Phytochemicals: Extraction Process, Safety Assessment, Toxicological Evaluations, and Regulatory Issues. Functional and Preservative Properties of Phytochemicals 2020, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, I.L.; Miranda, L.C.F.; da Cruz Rodrigues, A.M.; da Silva, L.H.M.; Amante, E.R. Camu-Camu [Myrciaria Dubia (HBK) McVaugh]: A Review of Properties and Proposals of Products for Integral Valorization of Raw Material. Food Chem 2022, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, J.C.; Maddox, J.D.; Cobos, M.; Imán, S.A. Myrciaria Dubia “Camu Camu” Fruit: Health-Promoting Phytochemicals and Functional Genomic Characteristics. In Breeding and Health Benefits of Fruit and Nut Crops; InTech, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Akter, M.S.; Oh, S.; Eun, J.B.; Ahmed, M. Nutritional Compositions and Health Promoting Phytochemicals of Camu-Camu (Myrciaria Dubia) Fruit: A Review. Food Research International 2011, 44, 1728–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, A.; Sarkar, D.; Genovese, M.I.; Shetty, K. Improving Anti-Hyperglycemic and Anti-Hypertensive Properties of Camu-Camu (Myriciaria Dubia Mc. Vaugh) Using Lactic Acid Bacterial Fermentation. Process Biochemistry 2017, 59, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracassetti, D.; Costa, C.; Moulay, L.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. Ellagic Acid Derivatives, Ellagitannins, Proanthocyanidins and Other Phenolics, Vitamin C and Antioxidant Capacity of Two Powder Products from Camu-Camu Fruit (Myrciaria Dubia). Food Chem 2013, 139, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, M.A.V. do; Fidelis, M.; Pressete, C.G.; Marques, M.J.; Castro-Gamero, A.M.; Myoda, T.; Granato, D.; Azevedo, L. Hydroalcoholic Myrciaria Dubia (Camu-Camu) Seed Extracts Prevent Chromosome Damage and Act as Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Agents. Food Research International 2019, 125, 108551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyashita, T.; Koizumi, R.; Myoda, T.; Sagane, Y.; Niwa, K.; Watanabe, T.; Minami, K. Data on a Single Oral Dose of Camu Camu (Myrciaria Dubia) Pericarp Extract on Flow-Mediated Vasodilation and Blood Pressure in Young Adult Humans. Data Brief 2018, 16, 993–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidelis, M.; Santos, J.S.; Escher, G.B.; Vieira do Carmo, M.; Azevedo, L.; Cristina da Silva, M.; Putnik, P.; Granato, D. In Vitro Antioxidant and Antihypertensive Compounds from Camu-Camu (Myrciaria Dubia McVaugh, Myrtaceae) Seed Coat: A Multivariate Structure-Activity Study. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2018, 120, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, T.; Komoda, H.; Uchida, T.; Node, K. Tropical Fruit Camu-Camu (Myrciaria Dubia) Has Anti-Oxidative and Anti-Inflammatory Properties. J Cardiol 2008, 52, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anhê, F.F.; Nachbar, R.T.; Varin, T. v.; Trottier, J.; Dudonné, S.; le Barz, M.; Feutry, P.; Pilon, G.; Barbier, O.; Desjardins, Y.; et al. Treatment with Camu Camu (Myrciaria Dubia) Prevents Obesity by Altering the Gut Microbiota and Increasing Energy Expenditure in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Gut 2019, 68, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Azevêdo, J.C.S.; Fujita, A.; de Oliveira, E.L.; Genovese, M.I.; Correia, R.T.P. Dried Camu-Camu (Myrciaria Dubia H.B.K. McVaugh) Industrial Residue: A Bioactive-Rich Amazonian Powder with Functional Attributes. Food Research International 2014, 62, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, A.; Sarkar, D.; Wu, S.; Kennelly, E.; Shetty, K.; Genovese, M.I. Evaluation of Phenolic-Linked Bioactives of Camu-Camu (Myrciaria Dubia Mc. Vaugh) for Antihyperglycemia, Antihypertension, Antimicrobial Properties and Cellular Rejuvenation. Food Research International 2015, 77, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.P. The Role of Direct and Indirect Polyphenolic Antioxidants in Protection against Oxidative Stress, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Inc., 2018; ISBN 9780128130063. [Google Scholar]

- Dahiya, D.; Terpou, A.; Dasenaki, M.; Nigam, P.S. Current Status and Future Prospects of Bioactive Molecules Delivered through Sustainable Encapsulation Techniques for Food Fortification. Sustainable Food Technology 2023, 1, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mello Andrade, J.M.; Fasolo, D. Polyphenol Antioxidants from Natural Sources and Contribution to Health Promotion; Elsevier Inc., 2013; Vol. 1, ISBN 9780123984562. [Google Scholar]

- Raddatz, G.C.; de Menezes, C.R. Microencapsulation and Co-Encapsulation of Bioactive Compounds for Application in Food: Challenges and Perspectives. Ciência Rural 2021, 51, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuidam, N.J.; Nedović, V.A. Encapsulation Technologies for Active Food Ingredients and Food Processing. Encapsulation Technologies for Active Food Ingredients and Food Processing 2010, 1–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veršič, R.J. Inventing and Using Controlled-Release Technologies. Microencapsulation in the Food Industry 2014, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, R.; Versic, R.; Gaonkar, A.G. Introduction to Microencapsulation and Controlled Delivery in Foods. In Microencapsulation in the Food Industry; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shafaei, Z.; Ghalandari, B.; Divsalar, A.; Saboury, A.A. Controlled Release Nutrition Delivery Based Intelligent and Targeted Nanoparticle; Elsevier Inc., 2017; ISBN 9780128043042. [Google Scholar]

- Guldiken, B.; Gulsunoglu, Z.; Bakir, S.; Catalkaya, G.; Capanoglu, E.; Nickerson, M. Innovations in Functional Foods Development. Food Technology Disruptions 2021, 73–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, A.; Sarkar, D.; Wu, S.; Kennelly, E.; Shetty, K.; Genovese, M.I. Evaluation of Phenolic-Linked Bioactives of Camu-Camu (Myrciaria Dubia Mc. Vaugh) for Antihyperglycemia, Antihypertension, Antimicrobial Properties and Cellular Rejuvenation. Food Research International 2015, 77, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Abreu Figueiredo, J.; Andrade Teixeira, M.; Henrique Campelo, P.; Maria Teixeira Lago, A.; Pereira de Souza, T.; Irene Yoshida, M.; Rodrigues de Oliveira, C.; Paula Aparecida Pereira, A.; Maria Pastore, G.; Aparecido Sanches, E.; et al. Encapsulation of Camu-Camu Extracts Using Prebiotic Biopolymers: Controlled Release of Bioactive Compounds and Effect on Their Physicochemical and Thermal Properties. Food Research International 2020, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Chacón, J.M.; Rodríguez-Pulido, F.J.; Heredia, F.J.; González-Miret, M.L.; Osorio, C. Characterization and Bioaccessibility Assessment of Bioactive Compounds from Camu-Camu (Myrciaria Dubia) Powders and Their Food Applications. Food Research International 2024, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mascaraque, L.G.; Lopez-Rubio, A. Production of Food Bioactive-Loaded Nanoparticles by Electrospraying. Nanoencapsulation of Food Ingredients by Specialized Equipment: Volume 3 in the Nanoencapsulation in the Food Industry series 2019, 107–149. [CrossRef]

- Busolo, M.A.; Torres-Giner, S.; Prieto, C.; Lagaron, J.M. Electrospraying Assisted by Pressurized Gas as an Innovative High-Throughput Process for the Microencapsulation and Stabilization of Docosahexaenoic Acid-Enriched Fish Oil in Zein Prolamine. Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies 2019, 51, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-García, J.D.; Prieto, C.; Pardo-Figuerez, M.; Lagaron, J.M. Room Temperature Nanoencapsulation of Bioactive Eicosapentaenoic Acid Rich Oil within Whey Protein Microparticles. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escobar-García, J.D.; Prieto, C.; Pardo-Figuerez, M.; Lagaron, J.M. Dragon’s Blood Sap Microencapsulation within Whey Protein Concentrate and Zein Using Electrospraying Assisted by Pressurized Gas Technology. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeevani, M.M.; Wijekoon, O.; Mahmood, K.; Ariffin, F.; Nafchi, A.M.; Zulkurnain, M. Recent Advances in Encapsulation of Fat-Soluble Vitamins Using Polysaccharides, Proteins, and Lipids: A Review on Delivery Systems, Formulation, and Industrial Applications. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 241, 124539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of Total Phenolics with Phosphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagent. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Figueiredo, J.; MT Lago, A.; M Mar, J.; S Silva, L.; A Sanches, E.; P Souza, T.; A Bezerra, J.; H Campelo, P.; A Botrel, D.; V Borges, S. Stability of Camu-Camu Encapsulated with Different Prebiotic Biopolymers. J Sci Food Agric 2020, 100, 3471–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidelis, M.; do Carmo, M.A.V.; da Cruz, T.M.; Azevedo, L.; Myoda, T.; Miranda Furtado, M.; Boscacci Marques, M.; Sant’Ana, A.S.; Inês Genovese, M.; Young Oh, W.; et al. Camu-Camu Seed (Myrciaria Dubia) – From Side Stream to an Antioxidant, Antihyperglycemic, Antiproliferative, Antimicrobial, Antihemolytic, Anti-Inflammatory, and Antihypertensive Ingredient. Food Chem 2020, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigio, M.L.; de Moura, E.A.; Chagas, E.A.; Durigan, M.F.B.; Chagas, P.C.; de Carvalho, G.F.; Zanchetta, J.J. Bioactive Compounds in and Antioxidant Activity of Camu-Camu Fruits Harvested at Different Maturation Stages during Postharvest Storage. Acta Sci Agron 2021, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, M.I.; Da Silva Pinto, M.; De Souza Schmidt Gonçalves, A.E.; Lajolo, F.M. Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity of Exotic Fruits and Commercial Frozen Pulps from Brazil. Food Science and Technology International 2008, 14, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirinos, R.; Galarza, J.; Betalleluz-Pallardel, I.; Pedreschi, R.; Campos, D. Antioxidant Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity of Peruvian Camu Camu (Myrciaria Dubia (H.B.K.) McVaugh) Fruit at Different Maturity Stages. Food Chem 2010, 120, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidelis, M.; de Oliveira, S.M.; Sousa Santos, J.; Bragueto Escher, G.; Silva Rocha, R.; Gomes Cruz, A.; Araújo Vieira do Carmo, M.; Azevedo, L.; Kaneshima, T.; Oh, W.Y.; et al. From Byproduct to a Functional Ingredient: Camu-Camu (Myrciaria Dubia) Seed Extract as an Antioxidant Agent in a Yogurt Model. J Dairy Sci 2020, 103, 1131–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracassetti, D.; Costa, C.; Moulay, L.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. Ellagic Acid Derivatives, Ellagitannins, Proanthocyanidins and Other Phenolics, Vitamin C and Antioxidant Capacity of Two Powder Products from Camu-Camu Fruit (Myrciaria Dubia). Food Chem 2013, 139, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alean, J.; Chejne, F.; Rojano, B. Degradation of Polyphenols during the Cocoa Drying Process. J Food Eng 2016, 189, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelli, V.; Sri Harsha, P.S.C.; Laureati, M.; Pagliarini, E. Degradation Kinetics of Encapsulated Grape Skin Phenolics and Micronized Grape Skins in Various Water Activity Environments and Criteria to Develop Wide-Ranging and Tailor-Made Food Applications. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2017, 39, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, J.D.; Prieto, C.; Pardo-Figuerez, M.; Lagaron, J.M. Dragon’s Blood Sap: Storage Stability and Antioxidant Activity. Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moratalla-López, N.; Lorenzo, C.; Chaouqi, S.; Sánchez, A.M.; Alonso, G.L. Kinetics of Polyphenol Content of Dry Flowers and Floral Bio-Residues of Saffron at Different Temperatures and Relative Humidity Conditions. Food Chem 2019, 290, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Ke, D.; Yang, Q.; Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; An, X.; Shen, W. Temperature-Dependent Stability and DPPH Scavenging Activity of Liposomal Curcumin at PH 7. 0. Food Chem 2012, 135, 1377–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bensemmane, N.; Bouzidi, N.; Daghbouche, Y.; Garrigues, S.; de la Guardia, M.; Hattab, M. El Prediction of Total Phenolic Acids Contained in Plant Extracts by PLS-ATR-FTIR. South African Journal of Botany 2022, 151, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlic, C.A. IR Absorption Table 2012.

- Santos, I.L.; Miranda, L.C.F.; da Cruz Rodrigues, A.M.; da Silva, L.H.M.; Amante, E.R. Camu-Camu [Myrciaria Dubia (HBK) McVaugh]: A Review of Properties and Proposals of Products for Integral Valorization of Raw Material. Food Chem 2022, 372, 131290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanatta, C.F.; Cuevas, E.; Bobbio, F.O.; Winterhalter, P.; Mercadante, A.Z. Determination of Anthocyanins from Camu-Camu (Myrciaria Dubia) by HPLC-PDA, HPLC-MS, and NMR. J Agric Food Chem 2005, 53, 9531–9535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, O.; Compère, G.; Larondelle, Y.; Pompeu, D.; Rogez, H.; Baeten, V. Phenolic Compound Explorer: A Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy Database. Vib Spectrosc 2017, 92, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, L.; Pizzi, A.; Guo, Z.D.; Brosse, N. Condensed Tannins from Grape Pomace: Characterization by FTIR and MALDI TOF and Production of Environment Friendly Wood Adhesive. Ind Crops Prod 2012, 40, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, H.; Baranska, M. Identification and Quantification of Valuable Plant Substances by IR and Raman Spectroscopy. Vib Spectrosc 2007, 43, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Abreu Figueiredo, J.; Andrade Teixeira, M.; Henrique Campelo, P.; Maria Teixeira Lago, A.; Pereira de Souza, T.; Irene Yoshida, M.; Rodrigues de Oliveira, C.; Paula Aparecida Pereira, A.; Maria Pastore, G.; Aparecido Sanches, E.; et al. Encapsulation of Camu-Camu Extracts Using Prebiotic Biopolymers: Controlled Release of Bioactive Compounds and Effect on Their Physicochemical and Thermal Properties. Food Research International 2020, 137, 109563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangles, O.; Fenger, J.A. The Chemical Reactivity of Anthocyanins and Its Consequences in Food Science and Nutrition. Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuyper, A.C. The Oxidation of Citric Acid. J Am Chem Soc 1933, 55, 1722–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speisky, H.; Shahidi, F.; Costa de Camargo, A.; Fuentes, J. Revisiting the Oxidation of Flavonoids: Loss, Conservation or Enhancement of Their Antioxidant Properties. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, Y.-J.; Njus, D.; Schlegel, H.B. A Theoretical Study of Ascorbic Acid Oxidation and HOO ˙/ O 2 ˙ − Radical Scavenging. Org Biomol Chem 2017, 15, 4417–4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karonen, M.; Imran, I. Bin; Engström, M.T.; Salminen, J.P. Characterization of Natural and Alkaline-Oxidized Proanthocyanidins in Plant Extracts by Ultrahigh-Resolution UHPLC-MS/MS. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Xu, M.; Zeng, M.; Qin, F.; Chen, J. Interactions of Milk α- And β-Casein with Malvidin-3-O-Glucoside and Their Effects on the Stability of Grape Skin Anthocyanin Extracts. Food Chem 2016, 199, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, J.; Pereira, C.G.; Almeida Junior, J.C. de; Viana, C.C.R.; Neves, L.N. de O.; Silva, P.H.F. da; Bell, M.J.V.; Anjos, V. de C. dos FTIR-ATR Determination of Protein Content to Evaluate Whey Protein Concentrate Adulteration. LWT 2019, 99, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Particle size (μm) |

DPPH inhibition (%) |

TSP (mg GAE/g dried CCX) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCX | 89.06 ± 0.02 b | 1.13 ± 0.05 a | |

| CCX – EAPG | 10.01 ± 1.84 a | 94.03 ± 0.02 a | 1.14 ± 0.07 a |

| WPC - CCX 1:1 | 6.74 ± 2.57 ab | 91.60 ± 0.06 ab | 1.15 ± 0.04 a |

| WPC - CCX 2:1 | 7.24 ± 2.49 ab | 94.07 ± 0.04 a | 1.11 ± 0.05 a |

| ZN - CCX 1:1 | 6.24 ± 2.33 ab | 85.32 ± 0.02 b | 1.21 ± 0.06 a |

| ZN - CCX 2:1 | 5.85 ± 1.45 b | 93.22 ± 0.04 a | 1.15 ± 0.05 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).