1. Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) encompasses a group of chronic inflammatory conditions affecting the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The two main forms are Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) [

1].

IBD is one of the worldwide health issues with growing incidence. According to a study that was conducted in 2021 addressing the epidemiology of IBD in the Arab world, it was found that the incidence rate of UC was 2.33 per 100,000 persons per year while the incidence rate of CD was 1.46 per 100,000 persons per year [

2].

While the exact cause of IBD remains largely unknown, it is widely believed to result from a complex interplay between the host genetics, gut microbiome, and immune system. This triggers a robust inflammatory response within the lamina propria, manifested by the excessive production of mucus, alpha-defensins, and antimicrobial peptides [

1].

Presentation of IBD varies depending on the type of IBD, “CD or UC”, genetics, site of affection, and lifestyle factors. Most common symptoms include bloody diarrhea, tenesmus, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and weight loss [

1]. Additionally, patients with IBD are at higher risk for developing serious infections. This vulnerability results from the use of immunosuppressive drugs, patients’ compromised innate immune responses to pathogens, and malnutrition [

3].

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a blood-borne hepatotropic virus that is preventable by vaccination [

4]. IBD patients are more prone to developing and reactivating HBV infection [

5]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommended global eradication of HBV through active treatment and vaccination. In 1990, HBV vaccination was included among scheduled vaccinations in Oman [

6]. The humoral immune response to HBV vaccination is expected to be > 90% in the normal healthy population, whereas a much lower rate is achieved in patients with IBD [

3]. In order to improve the immunogenicity of the HBV vaccine, some strategies such as using a booster dose or a new complete vaccine schedule, have been suggested [

7].

Multiple studies showed that IBD patients are at a higher risk for contracting HBV compared to the general population [

3,

4,

5,

8]. This raises concerns about the effectiveness of the current HBV vaccination strategies in protecting this vulnerable patient population.

This study aims to quantify the immunogenicity of the scheduled HBV vaccine in IBD patients and compare that with healthy organ and blood donors at SQUH.

The primary outcome is to compare the immune response to HBV vaccine between the two groups. The secondary outcomes included identifying possible risk factors for suboptimal vaccine response.

3. Results

This study enrolled a total of 126 IBD patients who underwent HBV screening and satisfied the pre-defined inclusion criteria. The participants exhibited a mean age of 22.3 years (SD ± 6.17), with a near-equal distribution of males and females.

Similarly, 126 healthy organs and blood donors were included as controls in this study. The mean age of controls was 27.7 years, 92 of whom (73%) were males and 34 of whom (27%) were females.

Serological analysis of HBV markers within the IBD group revealed the following distribution: 29 patients (23.0%) were seropositive for anti-HBs, indicating current immunity. Conversely, only two patients (1.6%) tested positive for anti-HBc, suggestive of prior HBV exposure without current immunity. Importantly, none of the IBD patients exhibited positivity for HBsAg, signifying the absence of ongoing viral replication [

Table 1].

Analysis of serological markers within the control group revealed a distinct distribution: 109 patients (86.5%) were seropositive for anti-HBs, indicative of protective immunity. Notably, five patients (4.0%) tested positive for HBsAg, signifying ongoing viral replication. These HBsAg-positive patients displayed a gender distribution of three males (60.0%) and two females (40.0%). Geographic analysis of these patients revealed that three (60.0%) resided in the Muscat governorate, one (20.0%) in Al Batinah North governorate, and one (20.0%) in Addakhiliyah governorate [

Table 1].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics: Baseline characteristics of the studied groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics: Baseline characteristics of the studied groups.

| |

Cases (%)

n=126

|

Controls (%)

n=126

|

| Age |

|

|

| <10 |

5 (4.0) |

0 |

| 10-20 |

38 (30.2) |

3 (2.4) |

| 20-32 |

83 (65.8) |

123 (97.6) |

| Sex |

|

|

| Male |

64 (50.8) |

92 (73.0) |

| Female |

62 (49.2) |

34 (27.0) |

| HBV screening Results |

|

|

| HBsAg (%) |

0 |

5 (3.9%) |

| Anti HBsAb (%) |

29 (23%) |

109 (86.5%) |

| Anti HBcAb (%) |

2 (1.6%) |

0 |

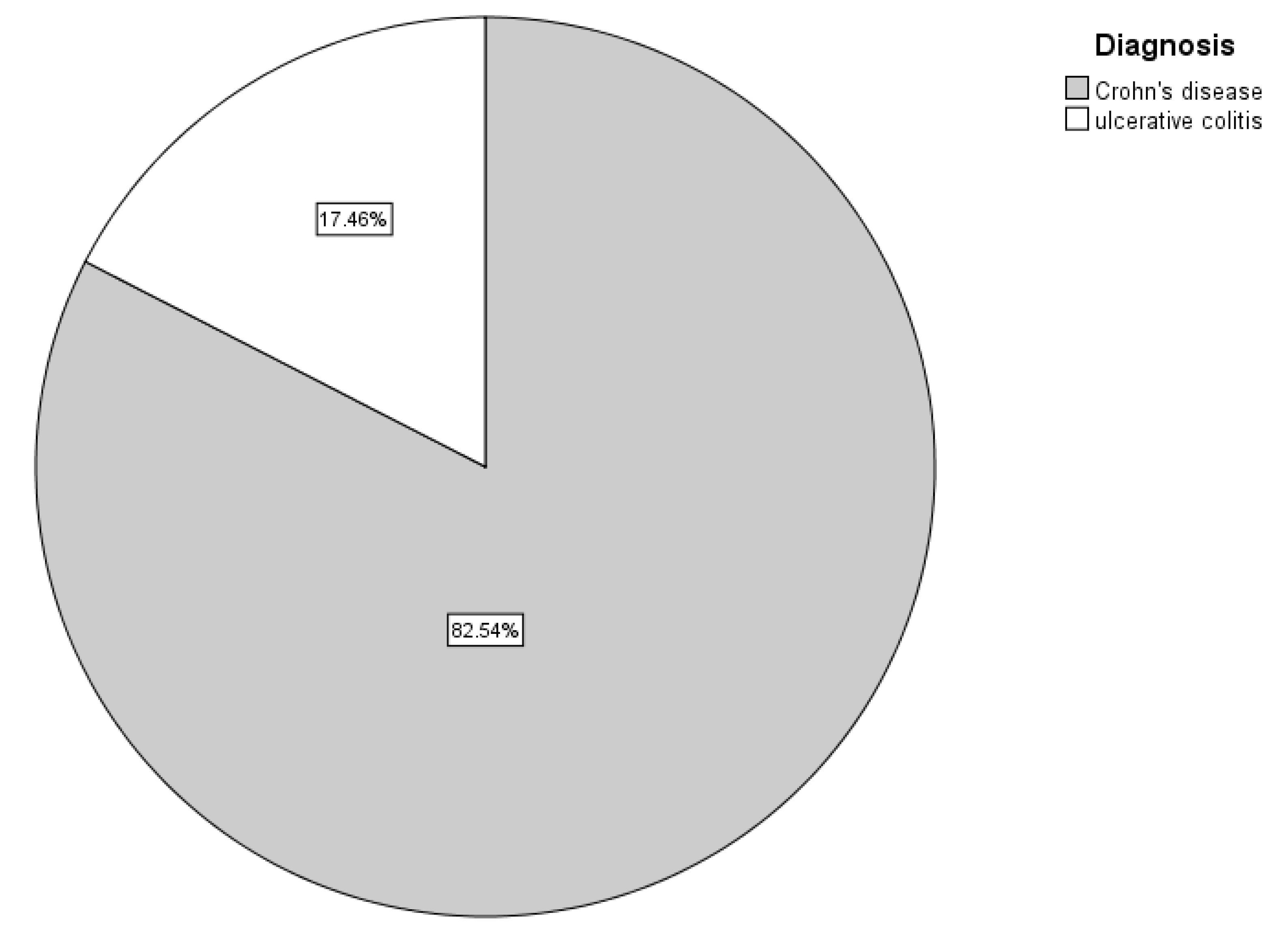

3.1. Distribution of UC and CD among IBD Patients

In this study,

Figure 1 shows that most of IBD patients (82.5%) were found to have CD, whereas only 22 patients (17.5%) had UC [

Figure 1].

3.2. Comorbidities among IBD Patients

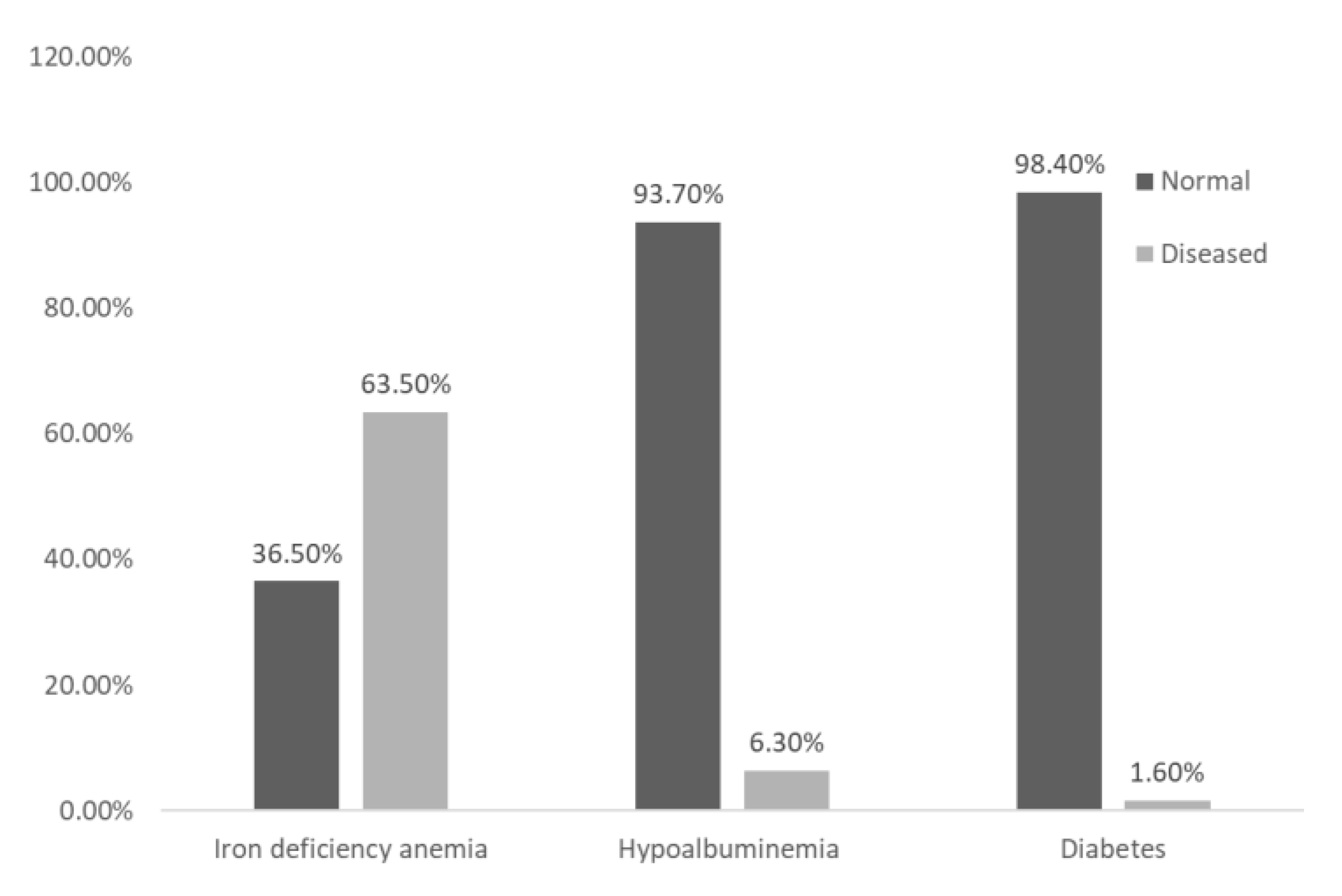

A significant proportion (65.1%) of IBD patients were reported to have one or more comorbidities. The most prevalent comorbidity was iron deficiency anemia, affecting 80 (63.5%) of patients. This was followed by hypoalbuminemia, which was identified in 8 (6.3%) of patients, and type 2 diabetes, which was found in 2 (1.6%) of patients

Figure 2.

Comorbidities among IBD patients.

Figure 2.

Comorbidities among IBD patients.

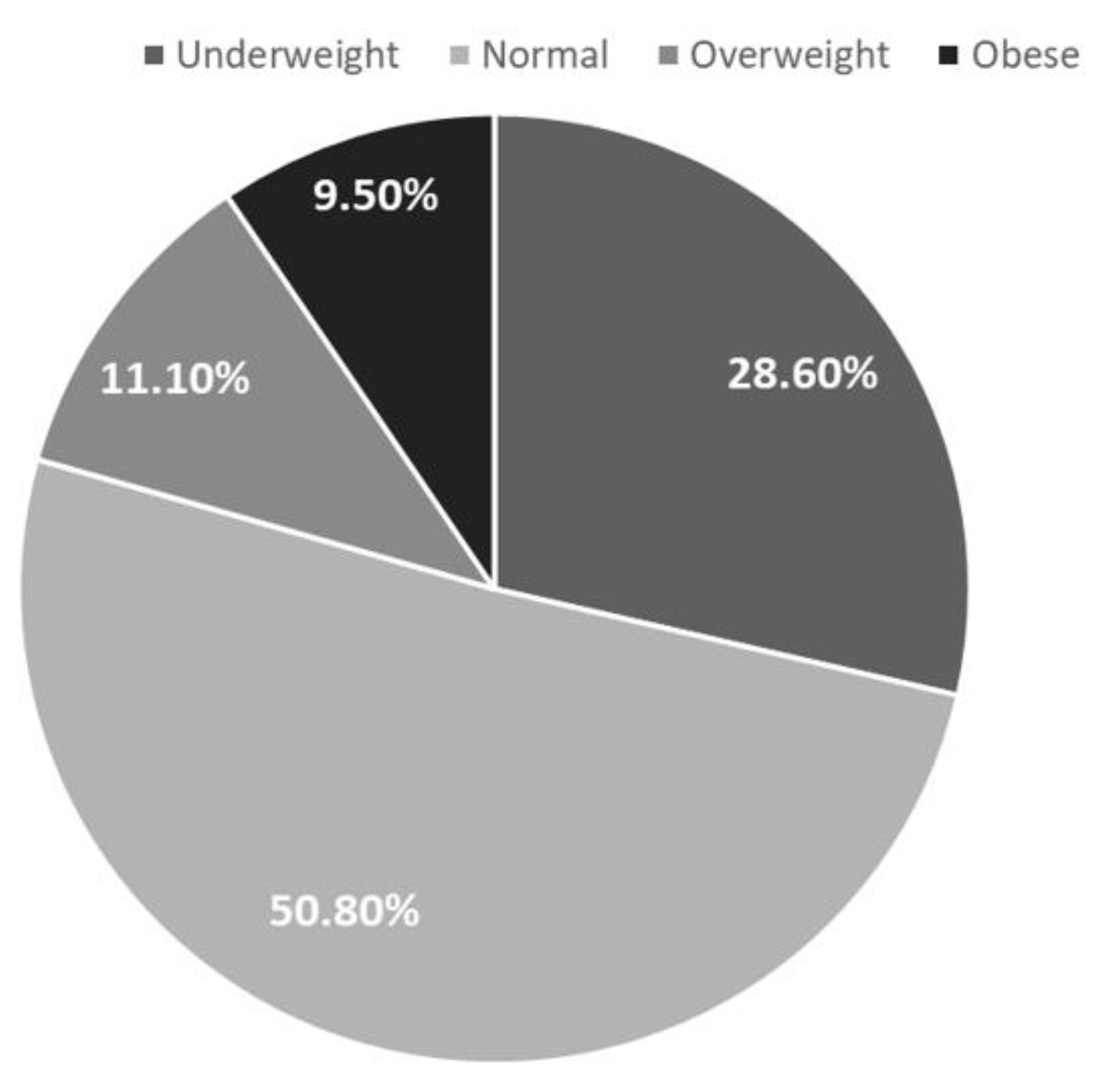

3.3. Distribution of BMI Category among IBD Patients

Figure 3 demonstrates the distribution of BMI categories among IBD patients. BMI was classified into four categories: underweight, normal weight, overweight and obese. Sixty four patients (50.8%) had normal weight, 36 patients (28.6%) were underweight, 14 patients (11.1%) were overweight, and 12 patients (9.5%) were obese.

3.4. Medication Usage Profiles in IBD Patients:

The most common treatment was immunosuppressive therapy (82.5%), particularly hydrocortisone (57.1%), followed by prednisolone (38.1%) and infliximab (35.7%) [

Table 2].

3.5. Analysis of Covariates Associated with Inadequate Seroprotection Following HBV Immunization in IBD Populations:

This study identified a statistically significant association (p-value = 0.0156) between prednisolone treatment and low anti-HBs levels. This finding suggests that prednisolone treatment may potentially impair the humoral immune response to the HBV vaccine. Indeed, additional investigation is warranted to delineate the mechanisms underlying this association. Furthermore, esomeprazole usage exhibited a highly significant association (p-value < 0.0001) with a suboptimal immune response to the HBV vaccine, warranting further investigation into the underlying mechanisms (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to quantify the immunogenicity of scheduled HBV vaccine in IBD patients and compare it with healthy controls at SQUH. Following HBV vaccination, an adequate immune response is achieved in more than 90% of healthy individuals. However, this percentage significantly drops in the immunosuppressed patients [

10]. The current study demonstrates a significantly lower immune response to the HBV vaccine in IBD patients compared to healthy controls. Among healthy controls, nearly 86.5% achieved a positive response following the standard HBV vaccination schedule. Conversely, only 23% of IBD patients mounted a long-term protective immune response. Generally, a diminished immune response following vaccination could be attributed to two key mechanisms. Firstly, pre-existing deficiencies within the immune system may lead to a suboptimal initial response. This could be due to factors such as genetic polymorphisms affecting immune cell function or a history of chronic illnesses compromising immune competence [

11]. Secondly, even if a robust initial immune response is mounted, factors like inadequate nutritional status or the administration of immunosuppressive medications might contribute to an eventual decline in vaccine-induced immunity [

10,

12].

Our findings align with other published studies that have reported lower immune response to HBV vaccination (24%–36%) in paediatric IBD patients [

13,

14,

15,

16].

In contrast, a previous study by Ardesia et al. (2016) [

17] documented a 61.6% prevalence of anti-HBs positivity among 99 IBD patients in Italy. This represents a 38.6% higher prevalence compared to our data. Stroffolini and Stroffolini (2023) [

18] potentially explain this discrepancy by reporting the routine administration of a booster HBV vaccine dose to all Italian teenagers at 12 years of age, which likely enhances the immune response observed in the Italian cohort.

In a recent meta-analysis by Kochhar et al. (2021) [

19] that included 14 studies evaluating 2375 IBD patients, the authors reported lower immune response to HBV vaccine in IBD group compared to healthy individuals. The pooled OR of response was 0.13 (95% CI, 0.05–0.33, P = 0.001). The observed low response to HBV vaccine can be attributed at least partly to the alterations in regulation of immune system. In recent years, IBD has been related to polymorphisms in multiple genes, which cause mutations on monocyte receptors, producing defects in the bactericidal activity of macrophages and affecting the secretion of cytokines. However, a comprehensive understanding of the interplay between genetic and immunological factors in IBD remains elusive [

4].

Furthermore, alterations in immune system regulation can be attributed to factors beyond genetics. Immunosuppressive medications used to manage IBD have also been linked to suboptimal immunological responses following vaccination. However, the impact of these therapies can vary considerably depending on the specific drug, dosage, and timing of administration [

3].

In the study conducted by Altunöz and colleagues, the authors reported that the response to HBV vaccination was inferior in IBD patients receiving several immunosuppressive medications compared to IBD patients not receiving any immunosuppressants. They concluded that HBV vaccine should be administered during remission, not during active disease and preferably when patients are not receiving immunosuppressive medications [

20].

Similarly, a recent study examining HBV vaccine immunogenicity in ulcerative colitis patients revealed a diminished immune response among those treated with infliximab compared to those receiving 5-ASA. These findings underscore the potential role of immunosuppressive agents and biologics in compromising HBV vaccine efficacy. [

10]. Further supporting the notion of a diminished HBV vaccine response in IBD patients on immunosuppressive therapy, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated a significantly decreased risk ratio (RR=0.73, 95% CI: 0.62-0.87) for a successful vaccine response in this group compared to those without immunosuppression. These findings underscore the substantial negative impact of immunosuppression on HBV vaccine efficacy within the IBD population.[

21].

While our study found a statistically significant association (p-value = 0.0156) between prednisolone use and lower anti-HBs levels in IBD patients, this observation aligns with the known immunosuppressive effects of corticosteroids like prednisolone. However, further investigation is warranted to determine the specific mechanisms by which prednisolone use might influence vaccine response in this patient population.

A research group from Kuwait investigated the immunogenicity of HBV vaccination in UC patients. Their findings revealed a significantly lower seroconversion rate (12.1%) in patients receiving infliximab compared to those treated with mesalamine (76.7%). Interestingly, even UC patients without current immunosuppressive therapy demonstrated a suboptimal response compared to the general population. This suggests potential underlying immune dysfunction in UC patients beyond the immediate effects of specific medications [

10].

Interestingly, our analysis also revealed a highly significant association (p-value < 0.0001) between esomeprazole use and suboptimal immune response to the HBV vaccine. Recently, Lin et al. (2021) suggested that chronic use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like esomeprazole might influence the gut microbiome, potentially leading to alterations in the immune system and even autoimmune diseases. These alterations were recently suggested to attenuate the response to vaccinations [

22,

23].

On the same line, PPIs have been proven to have a direct impact on the immune system. Mounting evidence suggests that PPIs exert multifaceted effects on the immune system. Preclinical in vivo studies have demonstrated that, unlike H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs), PPIs exhibit pleiotropic effects, targeting a range of immune defense molecules. These molecules include tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) [

24,

25,

26]. Further supporting these findings, recent clinical research indicates that pantoprazole modulates the immune response by downregulating the expression of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and interleukin-2 (IL-2). This modulation appears to be mediated through the regulation of key signaling molecules [

27]. Indeed, further research is needed to explore the specific mechanisms by which esomeprazole might affect vaccine response in IBD patients.

Our analysis did not reveal statistically significant associations (p-value > 0.05) between various demographic factors in IBD patients and their response to the HBV vaccine. This agrees with the results of a recent meta-analysis that involved 2602 IBD patients, where the response rate to HBV vaccine was not affected by gender, IBD subtype or disease severity [

21].

However, this finding contrasts with a study by Cossio-Gil et al. (2015) in Spain [

4], which reported a significant association (p-value = 0.034) between younger age and higher anti-HBs levels in IBD patients. A likely explanation for this disparity resides in the differing age distributions of the study populations. The Spanish cohort had a mean age of 44.5 years (SD 9.9), whereas our study participants exhibited a mean age of 22.3 years (SD 6.17). The data from Cossio-Gil et al. (2015) might suggest an age-related decline in anti-HBs levels, but further research is warranted to explore this possibility and investigate the influence of age on HBV vaccine response in IBD patients across a broader age range.

Our analysis identified CD as the most prevalent form of IBD within the study cohort, accounting for 82.5% of cases. Within this group, 24.0% of CD patients achieved an adequate response to the HBV vaccine. Similarly, 18.2% of UC patients demonstrated a protective immune response to HBV vaccination. It is noteworthy that a previous study by Ardesia et al. (2016) [

17] reported a trend towards a lower response rate in CD compared to UC patients (CD: 42.4% vs. UC: 30.3% without adequate anti-HBs titer). However, neither our study nor the one by Ardesia et al. (2016) reached statistical significance for the observed difference in response rates between CD and UC. This finding might be attributable to the composition of our study cohort, as a significant portion of our patients suffered from severe IBD requiring immunosuppressive therapy. CD is known to be more commonly associated with the need for immunosuppression compared to UC [

17]. Therefore, the overrepresentation of CD patients in our study might have influenced the observed prevalence of this specific IBD subtype. Additionally, this finding may be influenced by selection bias, potentially due to the inclusion criterion restricting participant age to be younger than 32 years old.

Considering the potential influence of comorbidities on vaccine response in IBD patients, this study investigated the associations between iron deficiency anemia, hypoalbuminemia, and type 2 diabetes with the observed suboptimal immune response to the HBV vaccine. Our analysis revealed no statistically significant associations between these specific comorbidities and the low immune response (p-value > 0.05). This finding contrasts with a study by Cossio-Gil et al. (2015) conducted in Spain, which reported a significant association between certain comorbidities, primarily hypertension, and a low immune response to HBV vaccination in IBD patients.

Similarly, obesity has been associated with increased susceptibility to infections, autoimmune diseases, and chronic inflammation [

28]. This study explored the potential link between BMI and the suboptimal immune response to the HBV vaccine observed in IBD patients. Indeed, our analysis did not reveal a statistically significant association between BMI and vaccine response. Notably, half of the study participants were classified as having a healthy weight, with the remaining patients distributed across the underweight, overweight, and obese categories.

Eventually, none of the IBD patients in this study tested positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), indicating no evidence of current HBV infection. In contrast, the control group exhibited a 4% HBsAg positivity rate. This unexpected finding warrants further investigation. Potential explanations could include the higher mean age of the control group (27.7) versus (22.3) for IBD group in addition to limitations in the implemented screening protocols. It is important to acknowledge that a previous study by Al-Busafi et al. (2021) identified a higher prevalence of HBsAg among males residing in the Muscat governorate, potentially due to risk factors like barber shaving and intra-familial contact. Future research efforts should explore these possibilities in a larger cohort to gain a clearer understanding of the observed distribution of HBsAg positivity [

8].

Limitations

Several limitations inherent to the study design warrant cautious interpretation of the findings. The single-center retrospective design conducted at SQUH restricts the generalizability of results to other populations and limits the ability to control for potential confounding factors such as vaccine variability and dosage. Furthermore, data incompleteness within the healthcare tracking system necessitated participant exclusion, potentially introducing selection bias and compromising the representativeness of the study cohort.