Submitted:

27 August 2024

Posted:

28 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population Survey and Sampling

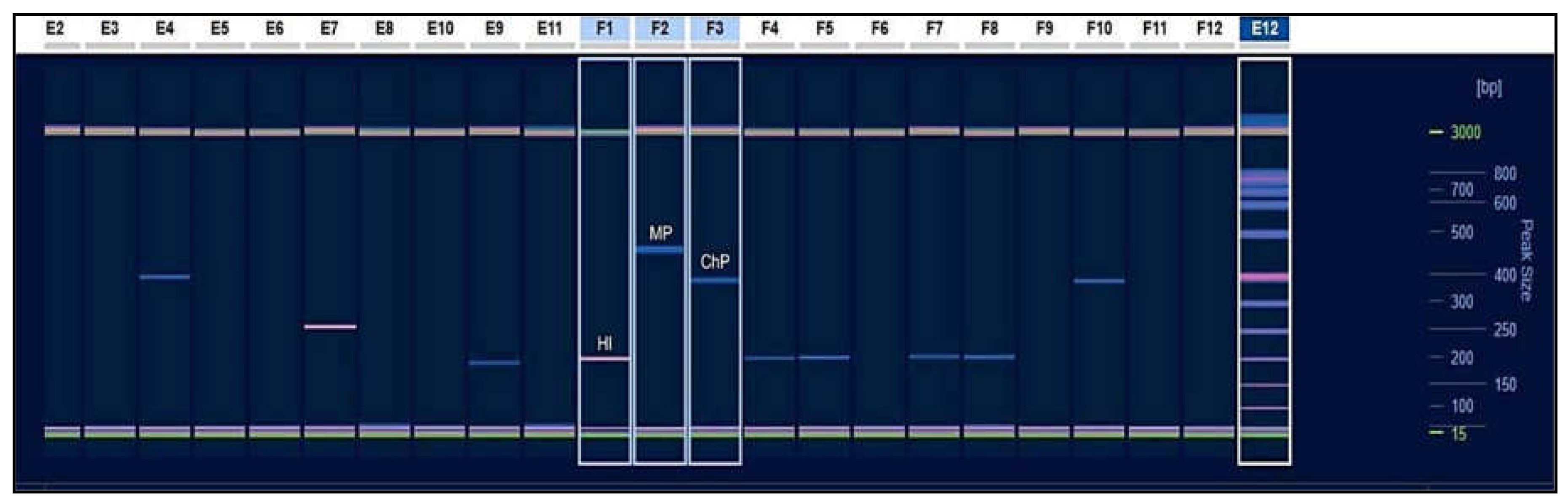

2.2. Detection of Respiratory Co-Pathogens

2.2.1. Extraction

2.2.2. Detection of Bacterial Co-Pathogens

2.2.3. Detection of Viral Co-Pathogens

- (1)

- AdV, RSV, and PIV1;

- (2)

- BoV, RV, and PIV2;

- (3)

- HMPV and PIV3;

- (4)

- HCoV-229E and HCoV-HKU-1;

- (5)

- HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-OC43;

- (6)

- SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A and B viruses (FluSC2).

2.3. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

2.4. Definitions and Data

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Population Characteristics

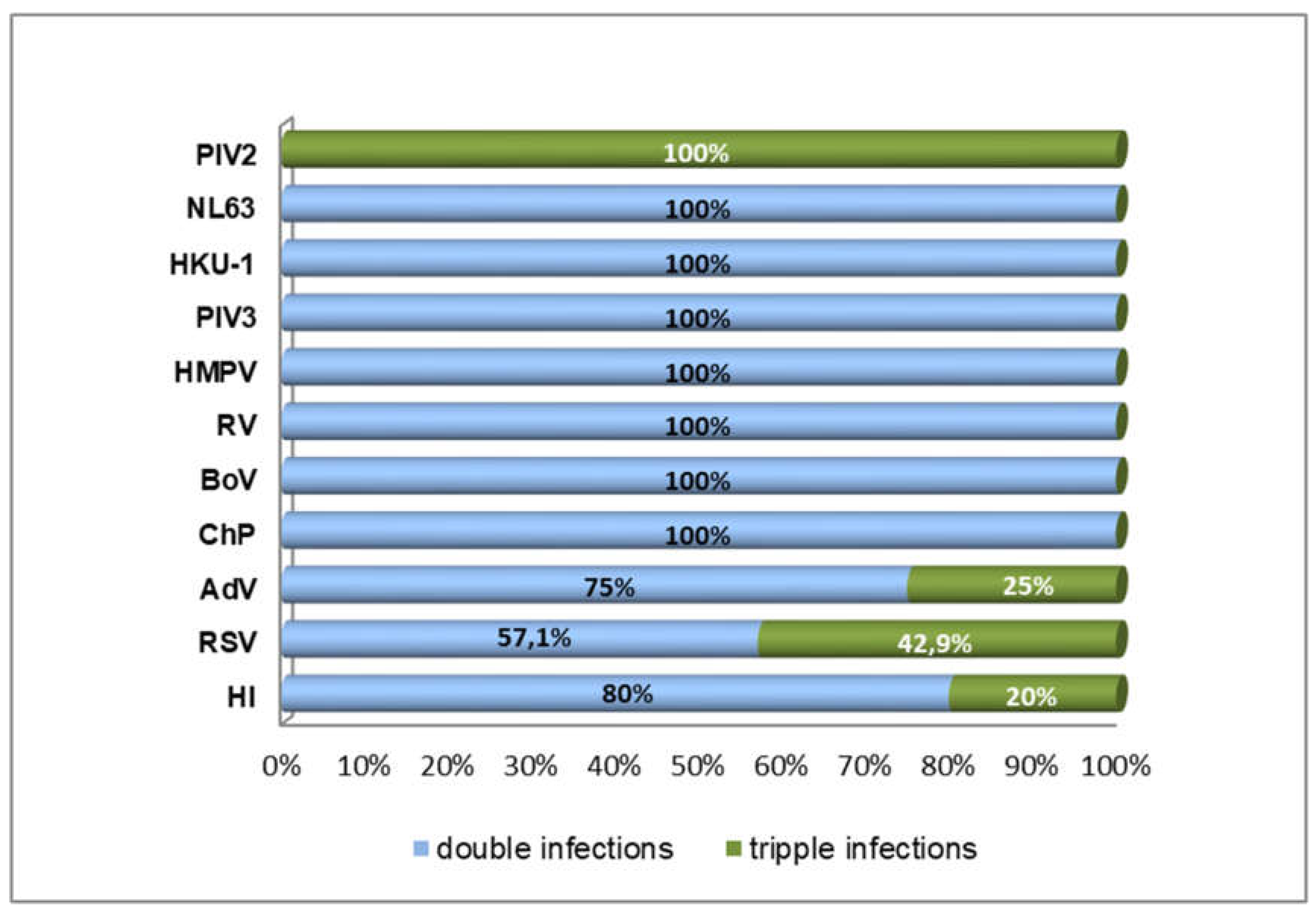

3.2. Detection of Co-Infections in COVID-19 Patients

| Co-Infection | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2+HI | 20 | 47,62% |

| SARS-CoV-2+RSV | 4 | 9,52% |

| SARS-CoV-2 +ChP | 3 | 7,14% |

| SARS-CoV-2+AdV | 3 | 7,14% |

| SARS-CoV-2+HI+RSV | 3 | 7,14% |

| SARS-CoV-2+BoV | 2 | 4,76% |

| SARS-CoV-2+RV | 1 | 2,38% |

| SARS-CoV-2+HMPV | 1 | 2,38% |

| SARS-CoV-2+PIV3 | 1 | 2,38% |

| SARS-CoV-2+НKU-1 | 1 | 2,38% |

| SARS-CoV-2+NL63 | 1 | 2,38% |

| SARS-CoV-2+HI+AdV | 1 | 2,38% |

| SARS-CoV-2+HI+PIV2 | 1 | 2,38% |

| SARS-CoV-2+MyPn | 0 | 0% |

| SARS-CoV-2+PIV1 | 0 | 0% |

| SARS-CoV-2+PIV2 | 0 | 0% |

| SARS-CoV-2+229E | 0 | 0% |

| SARS-CoV-2+OC43 | 0 | 0% |

| SARS-CoV-2+Influenza A | 0 | 0% |

| SARS-CoV-2+Influenza B | 0 | 0% |

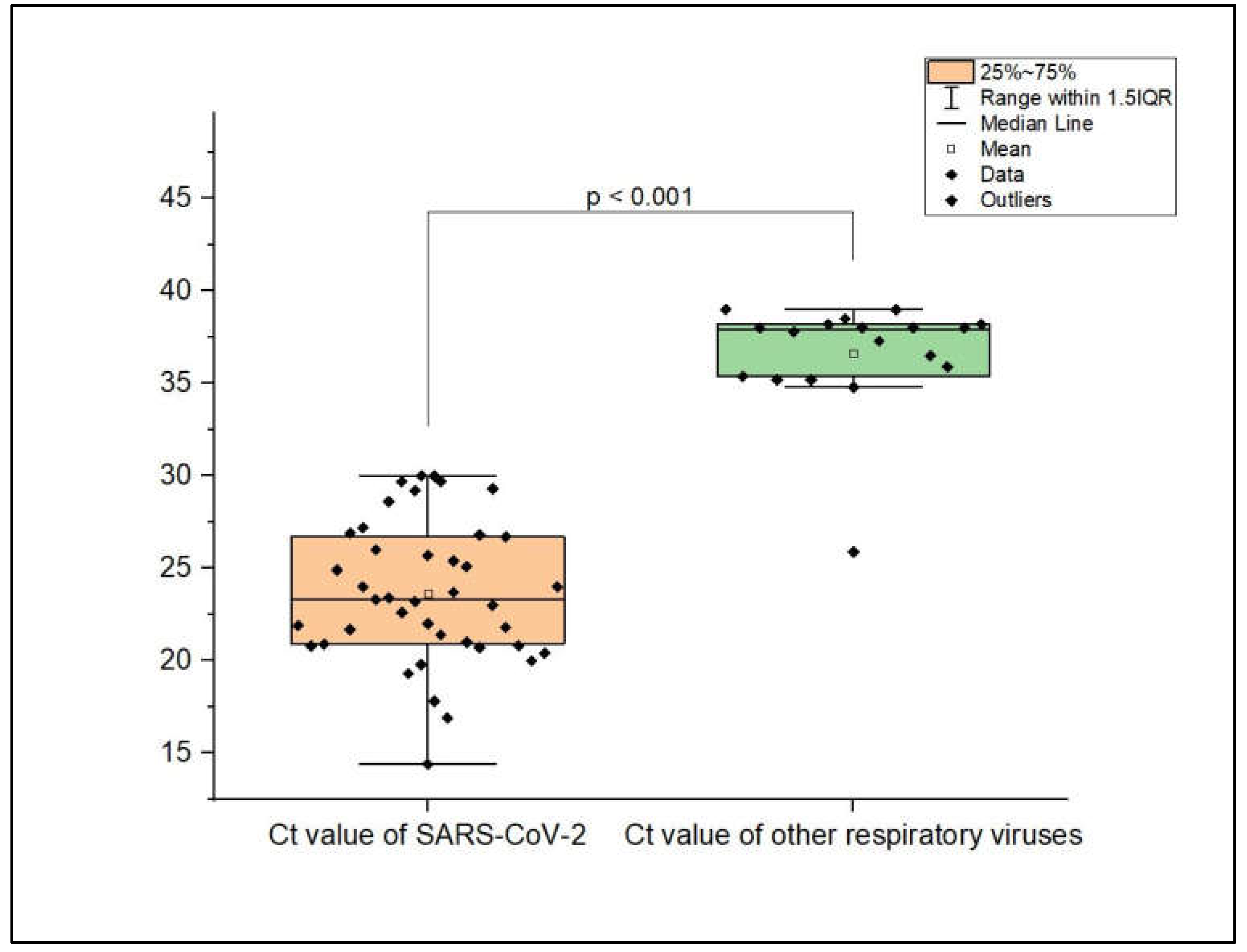

3.3. Viral Load of Respiratory Virus Co-Infections

3.4. Distribution of SARS-CoV-2 Variants in Individual Proven Co-Infections

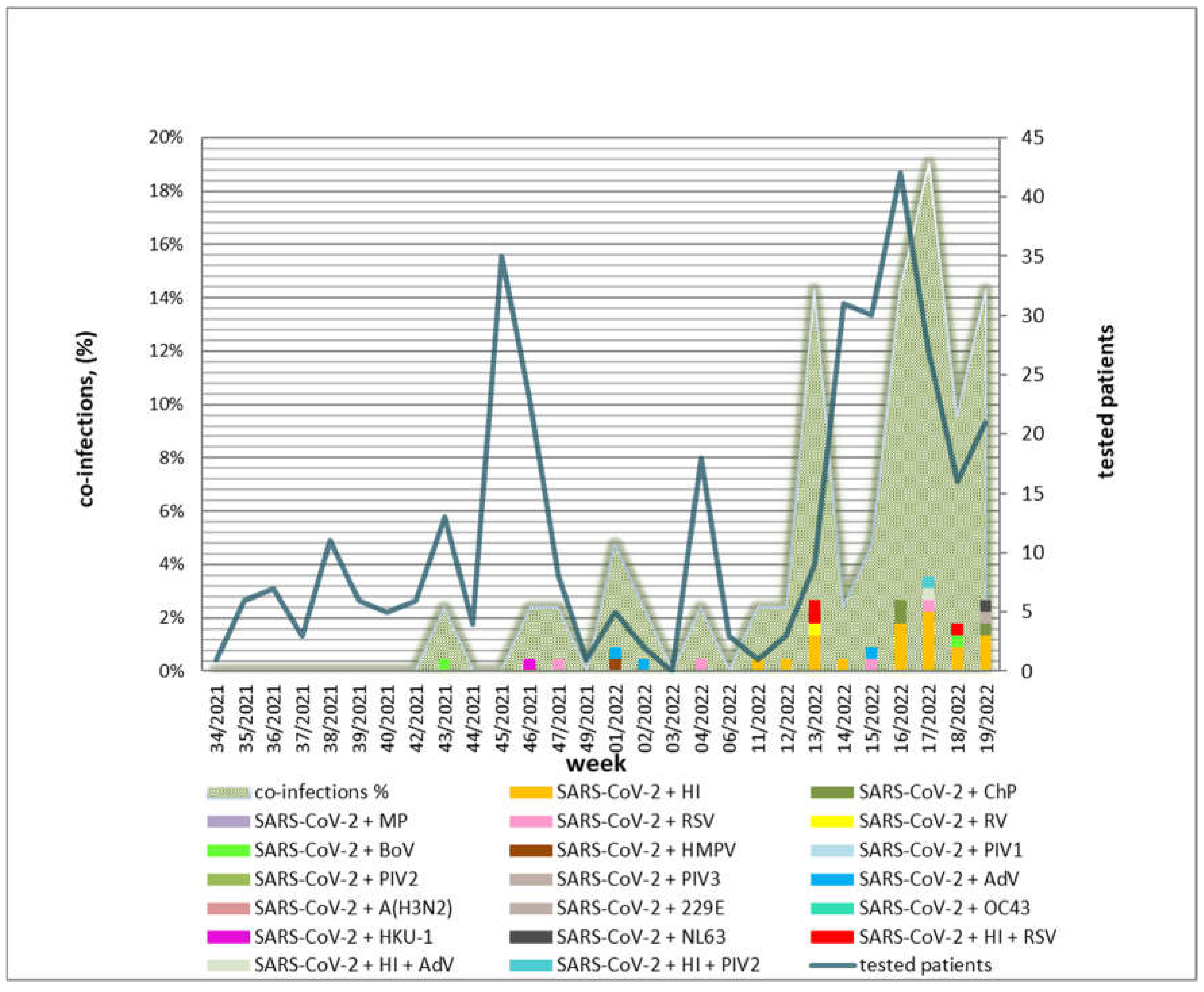

3.5. Weekly and Seasonal Distribution of Confirmed Co-Infections

3.6. Clinical Data of the Investigated Patients

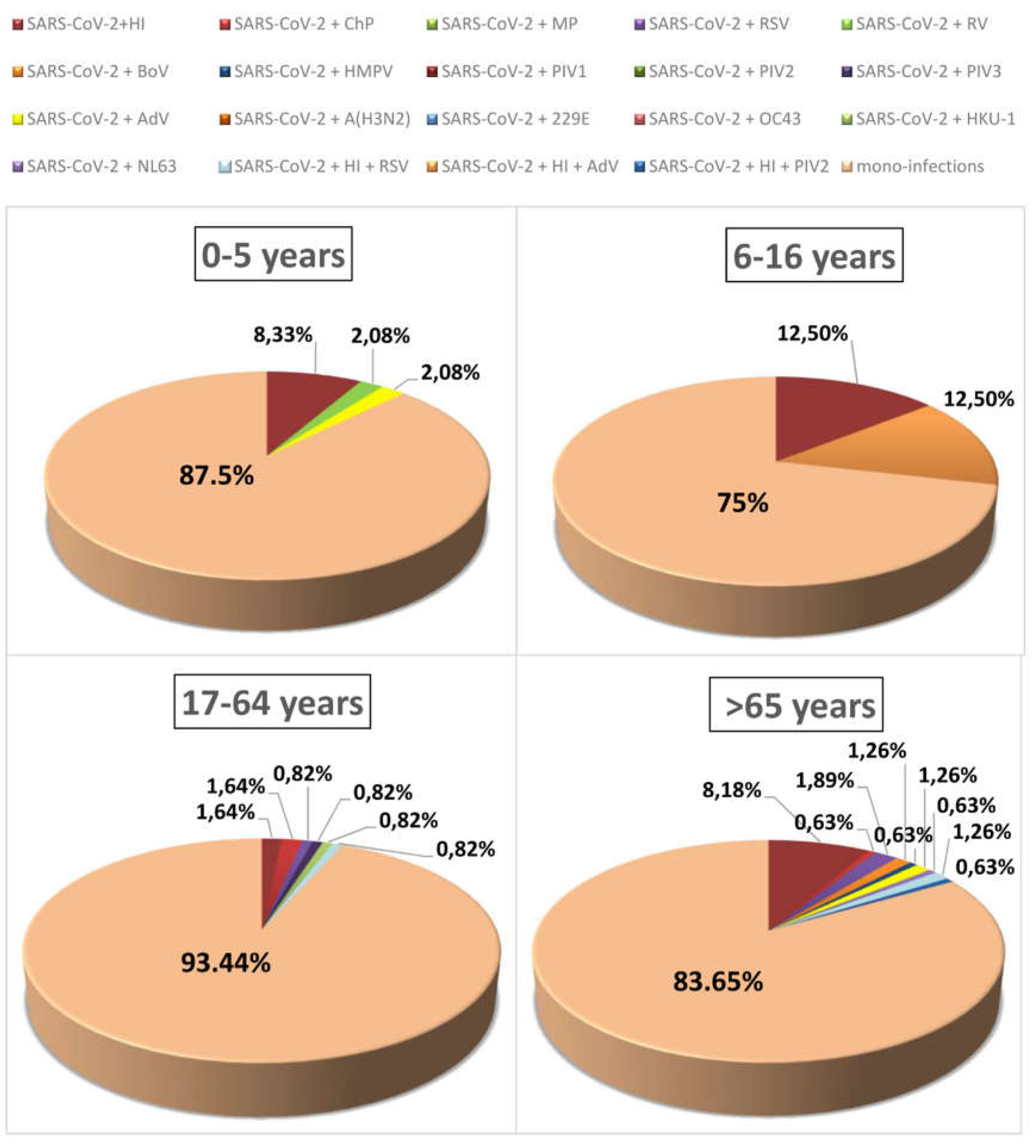

3.7. Age Characteristics of the Clinical Presentation of Respiratory Infection in Mono- and Co-Infected Patients

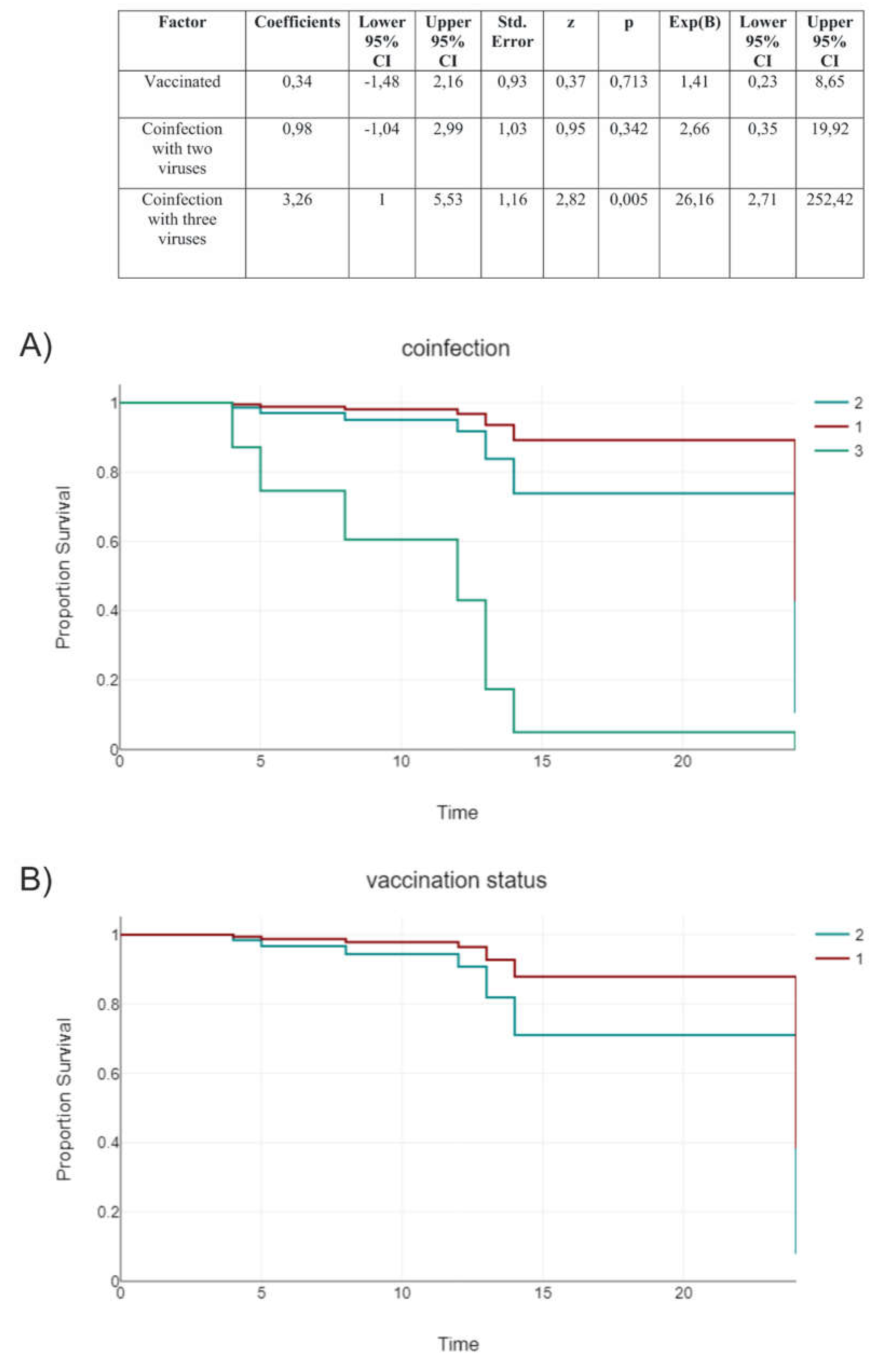

3.8. Vaccination Status

3.9. Determining the Clinical Severity of COVID-19 in Mono- and Co-Infections with Bacterial and Viral Co-Pathogens: Treatment

3.10. Treatment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Principi, N.; Autore, G.; Ramundo, G.; Esposito, S. Epidemiology of respiratory infections during the COVID-19 pandemic. Viruses 2023, 15, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, S.K.; Levin-Rector, A.; Kyaw, N.T.; Luoma, E.; Amin, H.; McGibbon, E. ..& Ahuja, S.D. Comparative hospitalization risk for SARS-CoV-2 Omicron and Delta variant infections, by variant predominance periods and patient-level sequencing results, New York City, August 2021–January 2022. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses 2023, 17, e13062. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, S.J.; Azziz-Baumgartner, E.; Budd, A.P.; Brammer, L.; Sullivan, S.; Pineda, R.F. .. & Fry, A.M. Decreased influenza activity during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, Australia, Chile, and South Africa, 2020. American Journal of Transplantation 2020, 20, 3681–3685. [Google Scholar]

- Groves, H.E.; Papenburg, J.; Mehta, K.; Bettinger, J.A.; Sadarangani, M.; Halperin, S.A. .. & Lefebvre, M.A. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on influenza-related hospitalization, intensive care admission and mortality in children in Canada: A population-based study. The Lancet Regional Health-Americas 2022, 7, 100132. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shen, C.; Luo, J.; Yu, W. Decreased Incidence of Influenza During the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of General Medicine 2022, 15, 2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, M.; Venturini, S.; De Rosa, R.; Crapis, M.; Basaglia, G. Epidemiology of respiratory virus before and during COVID-19 pandemic. Le Infezioni in Medicina 2022, 30, 104. [Google Scholar]

- Mandelia, Y.; Procop, G.W.; Richter, S.S.; Worley, S.; Liu, W.; Esper, F. Dynamics and predisposition of respiratory viral co-infections in children and adults. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2021, 27, 631–e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peci, A.; Tran, V.; Guthrie, J.L.; Li, Y.; Nelson, P.; Schwartz, K.L. . & Gubbay, J.B. Prevalence of co-infections with respiratory viruses in individuals investigated for SARS-CoV-2 in Ontario, Canada. Viruses 2021, 13, 130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lansbury, L.; Lim, B.; Baskaran, V.; Lim, W.S. Co-infections in people with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of infection 2020, 81, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumbein, H.; Kümmel, L.S.; Fragkou, P.C.; Thölken, C.; Hünerbein, B.L.; Reiter, R. .. & Skevaki, C. Respiratory viral co-infections in patients with COVID-19 and associated outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reviews in Medical Virology 2023, 33, e2365. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bengoechea, J.A.; Bamford, C.G. SARS-CoV-2, bacterial co-infections, and AMR: the deadly trio in COVID-19? EMBO molecular medicine 2020, 12, e12560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoque, M.N.; Chaudhury, A.; Akanda MA, M.; Hossain, M.A.; Islam, M.T. Genomic diversity and evolution, diagnosis, prevention, and therapeutics of the pandemic COVID-19 disease. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, B.J.; So, M.; Raybardhan, S.; Leung, V.; Westwood, D.; MacFadden, D.R. .. & Daneman, N. Bacterial co-infection and secondary infection in patients with COVID-19: a living rapid review and meta-analysis. Clinical microbiology and infection 2020, 26, 1622–1629. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khatiwada, S.; Subedi, A. Lung microbiome and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): possible link and implications. Human microbiome journal 2020, 17, 100073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddu, V.; Shean, R.C.; Xie, H.; Shrestha, L.; Perchetti, G.A.; Minot, S.S. . & Greninger, A.L. Metagenomic analysis reveals clinical SARS-CoV-2 infection and bacterial or viral superinfection and colonization. Clinical chemistry 2020, 66, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nishiura, H.; Kobayashi, T.; Miyama, T.; Suzuki, A.; Jung, S.M.; Hayashi, K. .. & Linton, N.M. Estimation of the asymptomatic ratio of novel coronavirus infections (COVID-19). International journal of infectious diseases 2020, 94, 154–155. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, C.; Sun, X.; Ye, J.; Ding, L.; Liu, M.; Yang, Z. ;... & Sun, B. Key residues of the receptor binding motif in the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 that interact with ACE2 and neutralizing antibodies. Cellular & molecular immunology.

- Trifonova, I.; Christova, I.; Madzharova, I.; Angelova, S.; Voleva, S.; Yordanova, R.; Tcherveniakova, T.; Krumova, S.; Korsun, N. Clinical significance and role of coinfections with respiratory pathogens among individuals with confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 infection. Front Public Health. 2022, 10, 959319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellinghausen, C.; Gulraiz, F.; Heinzmann, A.C.; Dentener, M.A.; Savelkoul, P.H.; Wouters, E.F.; Stassen, F.R. Exposure to common respiratory bacteria alters the airway epithelial response to subsequent viral infection. Respiratory research 2016, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalbiaktluangi, C.; Yadav, M.K.; Singh, P.K.; Singh, A.; Iyer, M.; Vellingiri, B.; Zomuansangi, R.; Zothanpuia Ram, H. A cooperativity between virus and bacteria during respiratory infections. Front Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1279159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoneim, H.E.; Thomas, G.; McCullers, J.A. Depletion of alveolar macrophages during influenza infection facilitates bacterial superinfections. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 1250–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, J.L.; Toffel, M.W.; Hugill, A.R. Monitoring global supply chains. Strategic Management Journal 2016, 37, 1878–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avadhanula, V.; Rodriguez, C.A.; DeVincenzo, J.P.; Wang, Y.; Webby, R.J.; Ulett, G.C.; et al. Respiratory viruses augment the adhesion of bacterial pathogens to respiratory epithelium in a viral species-and cell type-dependent manner. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 1629–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannakis, A.; Móré, D; Erdmann, S.; Kintzelé, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; L, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Fischer, R.M.; Vogel, M.N. .. & Hellbach, K. COVID-19 pneumonia and its lookalikes: How radiologists perform in differentiating atypical pneumonias. European Journal of Radiology 2021, 144, 110002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chibabhai, V.; Duse, A.G.; Perovic, O.; Richards, G.A. Collateral damage of the COVID-19 pandemic: exacerbation of antimicrobial resistance and disruptions to antimicrobial stewardship programmes? SAMJ: South African Medical Journal 2020, 110, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, C.; Anderson, R. The role of co-infections and secondary infections in patients with COVID-19. Pneumonia 2021, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayyosi, M.G.; Khuri-Bulos, N.A.; Halasa, N.B.; Faouri, S.; Shehabi, A.A. Rare occurrence of Bordetella pertussis among Jordanian children younger than two years old with respiratory tract infections. Journal of Pediatric Infectious Diseases 2015, 10, 053–056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodani, M.; Yang, G.; Conklin, L.M.; Travis, T.C.; Whitney, C.G.; Anderson, L. J;... & Fields, B.S. Application of TaqMan low-density arrays for simultaneous detection of multiple respiratory pathogens. Journal of clinical microbiology 2011, 49, 2175–2182. [Google Scholar]

- Dare, R.K.; Fry, A.M.; Chittaganpitch, M.; Sawanpanyalert, P.; Olsen, S.J.; Erdman, D.D. Human coronavirus infections in rural Thailand: a comprehensive study using real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction assays. The Journal of infectious diseases 2007, 196, 1321–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ARDS Definition Task Force; Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, Camporota L, Slutsky AS. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012, 307, 2526–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, N.; Campobasso, C.P.; Cocozza, S.; Conti, V.; Davinelli, S.; Costantino, M. . & Corbi, G. Relationship between COVID-19 mortality, hospital beds, and primary care by Italian regions: A lesson for the future. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11, 4196. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, N.K.; Al-Khawaja, S.; Alsalman, J.; Almusawi, S.; Albalooshi, N.A.; Al-Biltagi, M. Bacterial co-infection in patients with SARS-CoV-2 in the Kingdom of Bahrain. World journal of virology 2021, 10, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, C.; Singh, S.; Pathak, A.; Singh, S.; Patel, S.S.; Ghoshal, U.; Garg, A. Bacterial coinfections in COVID: Prevalence, antibiotic sensitivity patterns and clinical outcomes from a tertiary institute of Northern India. Journal of family medicine and primary care 2022, 11, 4473–4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Li, K.; Lei, Z.; Luo, J.; Wang, Q.; Wei, S. Prevalence and associated outcomes of co-infection between SARS-CoV-2 and influenza: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Zhou, L.; Lv, J.; Yang, S.; Chen, G.; Liu, X. . & Lan, K. Bacterial coinfections contribute to severe COVID-19 in winter. Cell Research 2023, 33, 562–564. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alhumaid, S.; Al Mutair, A.; Al Alawi, Z.; Alshawi, A.M.; Alomran, S.A.; Almuhanna, M.S. . & Al-Omari, A. Coinfections with bacteria, fungi, and respiratory viruses in patients with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pathogens 2021, 10, 809. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.; Upadhyay, P.; Reddy, J.; Granger, J. SARS-CoV-2 respiratory co-infections: Incidence of viral and bacterial co-pathogens. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2021, 105, 617–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contou, D.; Claudinon, A.; Pajot, O.; Micaëlo, M.; Longuet Flandre, P.; Dubert, M. . & Plantefève, G. Bacterial and viral co-infections in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia admitted to a French ICU. Annals of intensive care 2020, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Borkakoty, B.; Bali, N.K. Haemophilus influenzae and SARS-CoV-2: Is there a role for investigation? Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology 2021, 39, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies-Bolorunduro, O.F.; Fowora, M.A.; Amoo, O.S.; Adeniji, E.; Osuolale, K.A.; Oladele, O. .. & Salako, B. L. Evaluation of respiratory tract bacterial co-infections in SARS-CoV-2 patients with mild or asymptomatic infection in Lagos, Nigeria. Bulletin of the National Research Centre 2022, 46, 115. [Google Scholar]

- Swets, M.C.; Russell, C.D.; Harrison, E.M.; Docherty, A.B.; Lone, N.; Girvan, M. .. & Baillie, J. K. SARS-CoV-2 co-infection with influenza viruses, respiratory syncytial virus, or adenoviruses. The Lancet 2022, 399, 1463–1464. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Quinn, J.; Pinsky, B.; Shah, N.H.; Brown, I. Rates of co-infection between SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory pathogens. Jama 2020, 323, 2085–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvatore, P.P.; Dawson, P.; Wadhwa, A.; Rabold, E.M.; Buono, S.; Dietrich, E.A. .. & Kirking, H. L. Epidemiological correlates of polymerase chain reaction cycle threshold values in the detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Clinical Infectious Diseases 2021, 72, e761–e767. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nowak, M.D.; Sordillo, E.M.; Gitman, M.R.; Mondolfi, A.E.P. Coinfection in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients: where are influenza virus and rhinovirus/enterovirus? Journal of medical virology 2020, 92, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, S.F.; Diouara AA, M.; Ngom, B.; Thiam, F.; Dia, N. SARS-CoV-2 and Other Respiratory Viruses in Human Olfactory Pathophysiology. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifonova, I.; Korsun, N.; Madzharova, I.; Alexiev, I.; Ivanov, I.; Levterova, V. .. & Christova, I. Epidemiological and Genetic Characteristics of Respiratory Viral Coinfections with Different Variants of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Viruses 2024, 16, 958. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Babawale, P.I.; Guerrero-Plata, A. Respiratory Viral Coinfections: Insights into Epidemiology, Immune Response, Pathology, and Clinical Outcomes. Pathogens 2024, 13, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlBahrani, S.; AlZahrani, S.J.; Al-Maqati, T.N.; Almehbash, A.; Alshammari, A.; Bujlai, R. ;... & Al-Tawfiq, J.A. Dynamic Patterns and Predominance of Respiratory Pathogens Post-COVID-19: Insights from a Two-Year Analysis. Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health.

- Pattemore, P.K.; Jennings, L.C. Epidemiology of respiratory infections. Pediatric respiratory medicine 2008, 435. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein, S.; Hedrich, C.M. SARS-CoV-2 infections in children and young people. Clinical immunology 2020, 220, 108588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, F.; Lu, X.; Du, H.; Xu, J. . & Zhang, M. Co-infections of SARS-CoV-2 with multiple common respiratory pathogens in infected children: A retrospective study. Medicine 2021, 100, e24315. [Google Scholar]

- Karaaslan, A.; Çetin, C.; Akın, Y.; Tekol, S.D.; Söbü, E.; Demirhan, R. Coinfection in SARS-CoV-2 infected children patients. The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries 2021, 15, 761–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Rivera, B.; Saldaña-Ahuactzi, Z.; Parra-Ortega, I.; Flores-Alanis, A.; Carbajal-Franco, E.; Cruz-Rangel, A. .. & Luna-Pineda, V. M. Frequency of respiratory virus-associated infection among children and adolescents from a tertiary-care hospital in Mexico City. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 19763. [Google Scholar]

- El-Koofy, N. M. , El-Shabrawi, M. H., Abd El-alim, B. A., Zein, M. M., & Badawi, N. E. Patterns of respiratory tract infections in children under 5 years of age in a low–middle-income country. Journal of the Egyptian Public Health Association 2022, 97, 22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Solito, C.; Hernández-García, M.; Casamayor, N.A.; Ortiz, A.P.; Pino, R.; Alsina, L.; & de Sevilla, M.F.; & de Sevilla, M. F. COVID-19 admissions: Trying to define the real impact of infection in hospitalized patients. Anales de Pediatría (English Edition) 2024, 100, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchar, E.; Załęski, A.; Wronowski, M.; Krankowska, D.; Podsiadły, E.; Brodaczewska, K. . & Kubiak, J. Z. Children were less frequently infected with SARS-CoV-2 than adults during 2020 COVID-19 pandemic in Warsaw, Poland. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases 2021, 40, 541–547. [Google Scholar]

- Latouche, M.; Ouafi, M.; Engelmann, I.; Becquart, A.; Alidjinou, E.K.; Mitha, A.; Dubos, F. Frequency and burden of disease for SARS-CoV-2 and other viral respiratory tract infections in children under the age of 2 months. Pediatric Pulmonology 2024, 59, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, Y.Y.; Yin, C.H.; Yao, Y.M. Update advances on C-reactive protein in COVID-19 and other viral infections. Frontiers in immunology 2021, 12, 720363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N. Elevated level of C-reactive protein may be an early marker to predict risk for severity of COVID-19. Journal of medical virology 2020, 92, 2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.A. COVID-19–Associated Hospitalizations Among US Adults Aged≥ 65 Years—COVID-NET, 13 States, January–August 2023. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2023, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inaida, S.; Paul, R.E.; Matsuno, S. Viral transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 accelerates in the winter, similarly to influenza epidemics. American Journal of Infection Control 2022, 50, 1070–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei-Tavabe, N.; Kheiri, S.; Mousavi, M.S.; Mohammadian-Hafshejani, A. The Effect of Monovalent Influenza Vaccine on the Risk of Hospitalization and All-Cause Mortality According to the Results of Randomized Clinical Trials: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Iranian Journal of Public Health 2023, 52, 924. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, M.G.; Stenehjem, E.; Grannis, S.; Ball, S.W.; Naleway, A.L.; Ong, T.C. . & Klein, N. P. Effectiveness of Covid-19 vaccines in ambulatory and inpatient care settings. New England Journal of Medicine 2021, 385, 1355–1371. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Franco-Paredes, C. Transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 among fully vaccinated individuals. The Lancet. Infectious diseases 2022, 22, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Li, K.; Lei, Z.; Luo, J.; Wang, Q.; Wei, S. Prevalence and associated outcomes of co-infection between SARS-CoV-2 and influenza: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N. Elevated level of C-reactive protein may be an early marker to predict risk for severity of COVID-19. Journal of medical virology 2020, 92, 2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi-Haddad-Zavareh, M.; Bayani, M.; Shokri, M.; Ebrahimpour, S.; Babazadeh, A.; Mehraeen, R. . & Javanian, M. C-reactive protein as a prognostic indicator in COVID-19 patients. Interdisciplinary perspectives on infectious diseases 2021, 2021, 5557582. [Google Scholar]

- Mphekgwana, P.M.; Sono-Setati, M.E.; Maluleke, A.F.; Matlala, S.F. Low Oxygen Saturation of COVID-19 in Patient Case Fatalities, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Journal of Respiration 2022, 2, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhou, H.Y.; Zheng, H.; Wu, A. Towards Understanding and Identification of Human Viral Co-Infections. Viruses 2024, 16, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanidis, K.; Konstantelou, E.; Yusuf, G.T.; Oikonomou, A.; Tavernaraki, K.; Karakitsos, D. .. & Vlahos, I. Radiological, epidemiological and clinical patterns of pulmonary viral infections. European Journal of Radiology 2021, 136, 109548. [Google Scholar]

| PCR Conditions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Step | Cycles | Temperature | Time |

| 1. Initial denaturation | 1 | 94°С | 3 min. |

| 2.1 Denaturation 2.2 Annealing 2.3 Extension |

35 |

1) 94°С 2) 61°С 3) 72°С |

30 sec. 30 sec. 45 sec. |

| 3. Final extension | 1 | 72°С | 7 min. |

| Delta | ||

| Tested: 119 | ||

| Co-infections: 2 | ||

| Positive rate: 1.7% | ||

| AY.75.1 | + BoV | n=1 |

| AY.4.4 | + RSV | n=1 |

| Omicron | ||

| Tested: 186 | ||

| Co-infections: 32 (29 + 3 triple) | ||

| Positive rate: 17.2% | ||

| BA.1 | + AdV | n=1 |

| + RSV | n=1 | |

| BA.1.1 | + HI | n=2 |

| BA.2 | + HI | n=13 |

| + HI + RSV | n=1 | |

| + HI +PIV2 | n=1 | |

| + HI + AdV | n=1 | |

| + ChP | n=2 | |

| + RSV | n=1 | |

| + BoV | n=1 | |

| + PIV3 | n=1 | |

| + NL63 | n=1 | |

| + AdV | n=2 | |

| BA.2.12 | + RV | n=1 |

| BA.2.9 | + HI | n=2 |

| + ChP | n=1 | |

| Age Group (Years Old) | 0-5 | 6-16 | 17-64 | >65 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-infected* (n) | 5 | 2 | 7 | 17 |

| Symptom | ||||

| Fever, n (%) | 4 (80) | 1 (50) | 7 (100) | 13 (76.5) |

| Fatigue, n (%) | 4 (80) | 2 (100) | 7 (100) | 11 (64.7) |

| Cough, n (%) | 2 (40) | 0 (0) | 7 (100) | 14 (82.4) |

| Diarrhea, n (%) | 1 (20) | 1 (50) | 2 (28,6) | 0 (0) |

| Headache, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (17.6) |

| Rheum, n (%) | 3 (60) | 1 (50) | 2 (28,6) | 4 (23.5) |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 2 (40) | 2 (100) | 5 (71,4) | 15 (88.2) |

| Laboratory results | ||||

| Oxygen saturation, mean % | 93.2 | 90.5 | 91.7 | 89.5 |

| Lym, mean x10⁹/L | 2.73 | 2.1 | 2.10 | 2.32 |

| WBC, mean x10⁹/L | 5.12 | 9.75 | 4.94 | 5.48 |

| CRP, mean mg/L | 16.2 | 56.0 | 42.9 | 78.1 |

| Hospital stay, mean (days) | 3.1 | 6 | 5.2 | 8.12 |

| Clinical outcome | ||||

| ICU stay, n (%) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (20) |

| Fatal outcome, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (14.3) | 2 (11.8) |

| SARS-CoV-2 Mono-Infection | Viral SARS-CoV-2 Co-Infection | Bacterial SARS-CoV-2 Co-Infection | SARS-CoV-2 Triple Infection | p-Value: Viral vs. Bacterial Co-Infection | p-Value: Co- vs. Triple Infection | p-Value: Mono- vs. Co- Infection | p-Value: Mono- vs. Triple Infection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distribution, n (%) | 295 (87.5) | 14 (4.2) | 23 (6.8) | 5 (1.5) | – | – | – | – |

| With clinical data, n | 141 | 9 | 19 | 5 | – | – | – | – |

| Symptoms, n (%) | ||||||||

| Fever | 110 (78) | 8 (88.9) | 15 (78.9) | 4 (80) | 1 | 1 | 0.8138 | 1 |

| Fatigue | 111 (78.8) | 7 (77.8) | 14 (73.7) | 4 (80) | 1 | 1 | 0.8151 | 1 |

| Cough | 107 (75.9) | 7 (77.8) | 14 (73.7) | 3 (60) | 1 | 0.5971 | 0.8228 | 0.5971 |

| Diarrhea | 22 (15.6) | 1 (11.7) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (40) | 1 | 0.1546 | 1 | 0.1895 |

| Headache | 39 (27.7) | 4 (44.4) | 1 (5.3) | – | 0.0256 | 0.5686 | 0.1825 | 0.3247 |

| Rheum | 50 (35.5) | 3 (33.3) | 4 (21.1) | 2 (40) | 0.6465 | 0.5971 | 0.4198 | 1 |

| Pneumonia | 83 (58.9) | 6 (66.7) | 12 (63.2) | 3 (60) | 1 | 1 | 0.6955 | 1 |

| Laboratory results, mean | ||||||||

| Oxygen saturation (%) | 91.8 | 93.4 | 90.4 | 87.8 | n.s* | n.s | n.s | n.s |

| Lym, (x10⁹/L) | 1.76 | 0.88 | 3.1 | 1.5 | n.s | n.s | n.s | n.s |

| WBC, (x10⁹/L) | 6.9 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 8.7 | n.s | 0.02 | n.s | n.s |

| CRP, (mg/L) | 65.5 | 86.7 | 48.3 | 109.6 | n.s | n.s | n.s | n.s |

| Treatment, n (%) | ||||||||

| Antibiotics | 96 (68.1) | 7 (77.8) | 12 (63.2) | 4 (80) | 0.67 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Antiviral drugs | 14 (9.9) | – | 1 (5.3) | – | 1 | 1 | 0.3086 | 1 |

| Corticosteroids | 44 (31.2) | 3 (33.3) | 9 (47.4) | 3 (60) | 0.687 | 0.639 | 0.1525 | 0.3283 |

| Vasodilators | 10 (7.1) | – | 1 (5.3) | – | 1 | 1 | 0.6925 | 1 |

| Heparin | 73 (51.8) | 6 (66.7) | 11 (57.9) | 2 (40) | 1 | 0.6285 | 0.5658 | 0.3595 |

| Oxygen therapy | 60 (42.6) | 3 (33.3) | 10 (52.3) | 4 (80) | 0.4348 | 0.3353 | 0.4367 | 0.1687 |

| Clinical outcome | ||||||||

| Hospital stay, mean (days) | 6.1 | 7.8 | 5.3 | 6.3 | n.s | n.s | n.s | n.s |

| ICU stay, n (%) | 1 (0.7) | – | 1 (5.3) | 2 (40) | 1 | 0.0501 | 0.3129 | 0.0028 |

| Fatal outcome, n (%) | 14 (9.9) | – | 2 (10.5) | 1 (20) | 1 | 0.3996 | 1 | 0.4493 |

| Factor | Coefficients | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | Std. Error | z | p | Exp(B) | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-infection with two viruses | 2,5 | 0,09 | 4,9 | 1,23 | 2,04 | 0,042 | 12,14 | 1,1 | 134,26 |

| Co-infection with three viruses | 4,55 | 1,51 | 7,58 | 1,55 | 2,94 | 0,003 | 94,5 | 4,54 | 1967,29 |

| Days from the onset of symptoms before hospitalization | 0,25 | -0,08 | 0,58 | 0,17 | 1,51 | 0,131 | 1,29 | 0,93 | 1,79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).