Submitted:

28 August 2024

Posted:

29 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theory

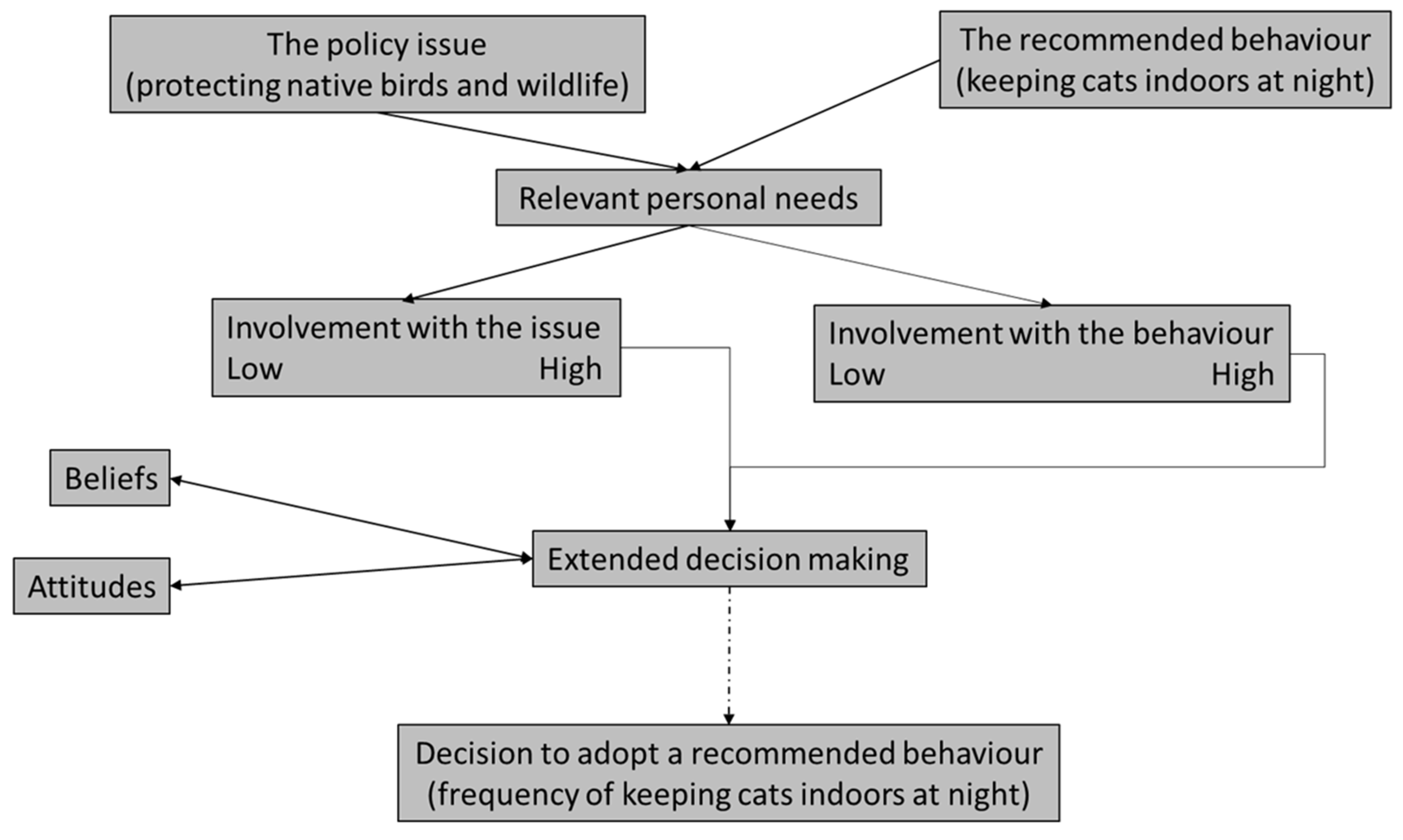

2.1. Involvement and Decision-Making

2.2. Approach-Avoidance Theory

2.3. Hypotheses

- Involvement with cat welfare and protecting wildlife from cats, together with salient beliefs, should influence involvement with keeping cats indoors at night. Salient beliefs are beliefs about the dangers cats pose to native birds and wildlife, the effect of protective measures on the welfare of cats, and the effectiveness of protective measures in preventing cats from harming wildlife.

- Attitudes towards keeping cats indoors at night, having cats wear collars, and the use of devices to deter cats from entering parks and reserves would be influenced by involvement with, and attitudes towards, the welfare of cats and with the protection of wildlife, and by salient beliefs.

- The strength of attitudes towards keeping cats indoors at night will be influenced by the degree of involvement with this behaviour as higher involvement is believed to promote greater search for information, resulting in stronger, more stable attitudes.

- Behavioural intentions with respect to protecting wildlife (such as willingness to take responsibility for protecting wildlife, and willingness to take some action, make sacrifices and work with others to protect wildlife from cats) will be influenced by involvement with, attitudes towards, and social norms in relation to the welfare of cats and to protecting wildlife from cats.

- Involvement with, attitude towards, and subjective norms about, keeping cats indoors at night will influence the frequency with which cat owners keep their cats indoors at night.

3. Materials and Methods

- statements about functional involvement concerned the importance of, and caring about, improving the welfare of cats,

- statements about experiential involvement concerned the reward from, and passion about, improving the welfare of cats,

- statement about self-identity concerned opinions about improving the welfare of cats reflecting on own identity, and others’ identity, as a person,

- statements about consequences concerned the seriousness or importance of consequences arising from making a mistake in relation to improving the welfare of cats, and

- statements about the risk of making mistakes concerned the complexity or difficulty of making decisions about improving the welfare of cats.

- I think pet cats should be kept inside at night.

- I think keeping pet cats inside at night is the right thing to do.

- I believe it is wrong to keep pet cats inside at night.

- Taking good care of all cats is the right thing to do.

4. Results

4.1. Factor Analysis of Beliefs

4.2. Involvement and Attitude Strength

4.3. Beliefs, Attitudes, and Involvement

4.4. Intentions and Behaviour

4.5. Approach-Avoidance Behaviour and Keeping Cats Indoors

- Greater differences in the desirability of serving cat welfare and keeping cats indoors at night

- Greater differences in the desirability of protecting wildlife and keeping cats indoors at night

- Low psychological distance with being able to keep cats indoors at night.

4.6. Involvement, Attitudes and Socio-Economic Demographics

| Involvement with surveillance | Involvement with baiting | Involvement with preventing spread | Involvement with surveillance | Involvement with baiting | Attitude towards surveillance | Attitude towards baiting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Involvement with preventing spread | 0.929 (p<0.001) |

0.365 (p<0.001) |

|||||

| Ants can spread quickly | 0.219 (p=0.004) |

0.250 (p<0.001) |

0.202 (p=0.012) |

||||

| Ants can seriously harm native species | 0.199 (p=0.003) |

0.302 (p<0.001) |

0.295 (p<0.001) |

0.214 (p=0.007) |

|||

| Ants are a real nuisance around the house | 0.186 (p=0.009) |

0.196 (p=0.008) |

|||||

| Ants are costly to control | 0.216 (p=0.001) |

0.232 (p<0.001) |

0.162 (p=0.021) |

0.285 (p<0.001) |

|||

| Ants can inflict severe financial losses on agricultural businesses | 0.211 (p=0.022) |

0.230 (p=0.004) |

|||||

| Ants can severely damage crops | |||||||

| Ants only spread slowly | -0.133 (p=0.036) |

||||||

| Ants are easy to identify | 0.164 (p=0.012) |

||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.19 |

| F-Test significance | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

5. Discussion

- Involvement with cat welfare, involvement with protecting wildlife and involvement with keeping cats indoors at night influenced the strength of respondents’ attitudes with respect to keeping cats indoors, having them wear collars and the use of area deterrents.

- Involvement with cat welfare, involvement with protecting wildlife and involvement with keeping cats indoors at night, in addition to their attitudes, positively influenced respondents’ intentions to protect wildlife and the frequency with which respondents with cats kept them indoors at night.

- We found respondents with cats were more likely than other respondents to believe that keeping cats indoors and making them wear collars is unnatural and harmful [59], and that devices intended to prevent cats from hunting wildlife are ineffective. They were less likely than other respondents to agree that cats are a danger to wildlife and are a health risk.

- Respondents who had never owned a cat had less favourable attitudes toward cats and more favourable attitudes towards keeping cats indoors, making them wear collars and using area deterrents, than other respondents. They also tended to believe that keeping cats indoors at night was easier, and that devices intended to prevent cats from hunting wildlife are effective, than other respondents. These respondents had, on average, moderate involvement with protecting wildlife from cats and mild involvement with cat welfare.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- This survey is being conducted for Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research and looks at peoples’ attitudes and opinions about pet and feral cats (cats living in the wild). We understand that, at times, cats can be difficult to manage because, well, cats are cats! And that can create challenges when it comes to satisfying their needs and wishes while looking out for the welfare of birds and wildlife.

- The information from this survey may be used in a report to the New Zealand Government to assist them in thinking about how best to care for cats while protecting our native birds and wildlife. The results may also be used in presentations and articles that will be submitted for publication.

- Your answers are confidential, and data presented from the survey cannot be traced back to individuals. We like to ask our questions a couple of different ways to make sure we get a good understanding of your attitudes and opinions. So things may get a little repetitive at times.

- Q1: To begin with, which of the following regions do you live in?

- ( ) Northland

- ( ) Auckland

- ( ) Waikato

- ( ) Bay of Plenty

- ( ) Gisborne

- ( ) Hawke's Bay

- ( ) Taranaki

- ( ) Manawatu-Whanganui

- ( ) Wellington

- ( ) Tasman/ Nelson

- ( ) Marlborough

- ( ) West Coast

- ( ) Canterbury

- ( ) Otago

- ( ) Southland

- Q2: Involvement with cat welfare.

- We are interested in your opinions about caring for cats. Thinking about cats in general, how strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statements?

| Item | Strongly agree | Agree |

Unsure/ neutral |

Disagree | Strongly disagree |

| It’s rewarding to take good care of cats | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The consequences are serious if we don’t take good care of cats | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I am passionate about taking good care of cats | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| It would be a big deal if mistakes were made when taking care of cats | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| My position on taking good care of cats tells others something about me | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Taking good care of cats is important to me | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Making decisions about how to take good care of cats is complicated | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| What others think about taking good care of cats tells me something about them | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I care a lot about taking good care of cats | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Making decisions about how to take good care of cats is difficult | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

- Q3: Involvement with protecting our native birds and wildlife.

- We are interested in your opinions about protecting our native birds and wildlife. How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statements?

| Item | Strongly agree | Agree |

Unsure/ neutral |

Disagree | Strongly disagree |

| It’s rewarding to protect our native birds and wildlife | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The consequences are serious if we don’t protect our native birds and wildlife | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I am passionate about protecting our native birds and wildlife | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| It would be a big deal if mistakes were made with protecting our native birds and wildlife | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| My position on protecting our native birds and wildlife tells others something about me | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Protecting our native birds and wildlife is important to me | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Making decisions about protecting our native birds and wildlife is complicated | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| What others think protecting our native birds and wildlife tells me something about them | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I care a lot about protecting our native birds and wildlife | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Making decisions about how to protect our native birds and wildlife is difficult | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

- Q4: Involvement with reducing the number of feral cats.

- We are interested in your opinions about reducing the number of feral cats. How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statements?

| Item | Strongly agree | Agree |

Unsure/ neutral |

Disagree | Strongly disagree |

| I think it would be rewarding to reduce the number of feral cats | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The consequences are serious if we don’t reduce the number of feral cats | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I am passionate about reducing the number of feral cats | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| It would be a big deal if we didn’t reduce the number of feral cats | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| My position on reducing the number of feral cats tells others something about me | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Having a program to reduce the number of feral cats is important to me | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Making decisions about reducing the number of feral cats is complicated | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| What others think about reducing the number of feral cats tells me something about them | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I care a lot about reducing the number of feral cats | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Making decisions about reducing the number of feral cats is difficult | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

- Q5: Involvement with keeping pet cats inside at night.

- We are interested in your opinions about keeping pet cats inside at night. How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statements?

| Item | Strongly agree | Agree |

Unsure/ neutral |

Disagree | Strongly disagree |

| I think keeping pet cats inside at night would be rewarding | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The consequences are serious if we don’t keep pet cats inside at night | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I am passionate about keeping pet cats inside at night | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| It would be a big deal if we didn’t keep pet cats inside at night | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| My position on keeping pet cats inside at night tells others something about me | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Keeping pet cats inside at night is important to me | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Making decisions about keeping pet cats inside at night is complicated | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| What others think about keeping pet cats inside at night tells me something about them | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I care a lot about keeping pet cats inside at night | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Making decisions about keeping pet cats inside at night is difficult | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

- Q6: Attitude towards using lethal traps to reduce the number of feral cats.

| Item | Strongly agree | Agree |

Unsure/ neutral |

Disagree | Strongly disagree |

| I think lethal traps should be used to reduce the number of feral cats | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I think using lethal traps to reduce the number of feral cats is the right thing to do | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I believe it is wrong to use lethal traps to reduce feral cat numbers | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

- Q7: Attitude towards using poison baits to reduce the number of feral cats.

| Item | Strongly agree | Agree |

Unsure/ neutral |

Disagree | Strongly disagree |

| I think poison baits should be used to reduce the number of feral cats | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I think using poison baits to reduce the number of feral cats is the right thing to do | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I believe it is wrong to use poison baits to reduce feral cat numbers | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

- Q8: Attitude towards keeping pet cats inside at night.

| Item | Strongly agree | Agree |

Unsure/ neutral |

Disagree | Strongly disagree |

| I think pet cats should be kept inside at night | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I think keeping pet cats inside at night is the right thing to do | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I believe it is wrong to keep pet cats inside at night | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

- Q9: Attitude towards using deterrents (e.g. recorded sounds, scent sprays, ultrasound) to protect birds and wildlife by stopping cats entering parks and gardens.

| Item | Strongly agree | Agree |

Unsure/ neutral |

Disagree | Strongly disagree |

| I think cat deterrents should be used to protect birds and wildlife | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I think using cat deterrents to protect birds and wildlife is the right thing to do | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I believe it is wrong to use cat deterrents to protect birds and wildlife | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

- Q10: Attitude towards cats wearing collars with warning devices such as a bell, small bib, or bright colours.

| Item | Strongly agree | Agree |

Unsure/ neutral |

Disagree | Strongly disagree |

| I think cats should wear collars with warning devices to help protect birds and wildlife | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I think having cats wear collars with warning devices to help protect birds and wildlife is the right thing to do | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I believe it is wrong to having cats wear collars with warning devices | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

- Q11: Your thoughts about cats. We are interested in your thoughts on cats. How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statements?

| Item | Strongly agree | Agree |

Unsure/ neutral |

Disagree | Strongly disagree |

| I think pet cats should be kept inside at night for their own safety | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I think cats are a nuisance | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I think wandering cats are a danger to other cats | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I think cats are a danger to wildlife | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| It’s natural for cats to hunt birds and wildlife | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I think wandering cats are a danger to themselves | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I think its unnatural to keep cats inside | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Collars with warning devices like bells don’t work | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Collars can be a danger to cats | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I don’t think deterrents are likely to be effective | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Some cats just won’t wear a collar | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Cats transmit diseases and parasites to other cats and animals | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Cats can transmit diseases and parasites to people | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Pet cats are not really a danger to native birds and wildlife | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Cats in urban areas are not really a danger to native birds and wildlife | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Keeping cats inside at night will only protect birds and wildlife if everyone does it | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I think lethal trapping of cats in the wild is inhumane | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| It’s difficult to keep cats inside at night | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I think using baits to control cats in the wild is cruel | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| If pet cats are outside at night, they could be attacked by feral cats | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

- Q12: What others think about pet cats.

- How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statements?

| Item | Strongly agree | Agree |

Unsure/ neutral |

Disagree | Strongly disagree |

| My family thinks keeping pet cats inside at night is the right thing to do | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| My friends think pet cats should be kept inside at night | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| My friends think using cat deterrents to protect birds and wildlife is the right thing to do | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| My family thinks using cat deterrents to protect birds and wildlife is the right thing to do | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

- Q13: Your opinions about managing feral cats.

- We are interested in your thoughts on reducing the impact of cats on the environment. How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statements?

| Item | Strongly agree | Agree |

Unsure/ neutral |

Disagree | Strongly disagree |

| Reducing the number of feral cats is the right thing to do | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I am prepared to take action to protect native birds and wildlife from cats | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Taking good care of all cats is the right thing to do | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I am prepared make sacrifices to protect native birds and wildlife from cats | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I think protecting native birds and wildlife is the right thing to do | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I am prepared to take some responsibility for protecting native birds and wildlife from cats | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| It is important to work together to protect native birds and wildlife from cats | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

- Q14: What others think about managing feral cats.

- How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statements?

| Item | Strongly agree | Agree |

Unsure/ neutral |

Disagree | Strongly disagree |

| My family thinks lethal trapping of feral cats is the right thing to do | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| My friends think lethal trapping of feral cats is the right thing to do | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| My friends think using poison baits to reduce the number of feral cats is the right thing to do | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| My family thinks using poison baits to reduce the number of feral cats is the right thing to do | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

- Q15: Which of the following statements best describes you?

| Item | Describes me |

| I really think lethal trapping of feral cats is the right thing to do | ☐ |

| Lethal trapping of feral cats doesn’t really matter to me | ☐ |

| I am not really sure if lethal trapping of feral cats is the best thing to do | ☐ |

| I haven’t put much thought into lethal trapping of feral cats | ☐ |

| I strongly believe that lethal trapping of feral cats is a bad thing to do | ☐ |

- Q16: Which of the following statements best describes you?

| Item | Describes me |

| I really think using cat deterrents is the right thing to do | ☐ |

| It doesn’t really matter to me whether or not cat deterrents are used | ☐ |

| I am not really sure if using cat deterrents is the best thing to do | ☐ |

| I haven’t put much thought into the use of cat deterrents | ☐ |

| I strongly believe that using cat deterrents is a bad thing to do | ☐ |

- Q17: Do you own a cat?

- Yes / No (If NO: go to Q21)

- We know that, at times, cats can be difficult to manage which means they may not always do what we want. So sometimes it’s easier just to let cats be cats!

- Q18: Do you keep your cat inside at night? (Please choose one)

| Frequency | |

| Never | ☐ |

| Sometimes | ☐ |

| Regularly | ☐ |

| Mostly | ☐ |

| Always | ☐ |

- Q19: Does it wear a collar? (Please choose one)

| Frequency | |

| Never | ☐ |

| Sometimes | ☐ |

| Regularly | ☐ |

| Mostly | ☐ |

| Always | ☐ |

- Q20: How often do you see cats, other than your cat, around your home? (Please choose one)

| Frequency | My experience |

| Rarely | ☐ |

| Every month or two | ☐ |

| Every week or two | ☐ |

| Most days | ☐ |

- Go to Q24

- Q21: Have you ever owned a cat?

- Yes/ No (If NO: go to Q23)

- Q22: Which of the following statements explains why you no longer have a cat?

- Please tick all that apply.

| Item | Describes me |

| I decided that cats pose too big a threat to our native birds and wildlife | ☐ |

| The time and effort involved in having a cat does not fit well with my lifestyle now | ☐ |

| My household circumstances make cat ownership undesirable or impossible (e.g. rental restrictions) | ☐ |

| Cats have become too expensive to keep | ☐ |

| Others in my household don’t like cats | ☐ |

| Someone in my household has a health condition (e.g. an allergy) which means we can’t have a cat | ☐ |

| Other (please feel free to describe in the text box to follow) | ☐ |

| [Open response text box here] |

- Q23: How often do you see cats around your home? (Please choose one)

| Frequency | My experience |

| Rarely | ☐ |

| Every month or two | ☐ |

| Every week or two | ☐ |

| Most days | ☐ |

- Q24: Do you own a dog?

- Yes / No

- If no: Have you ever owned a dog?

- Yes/No

- The questions below will be used to check how well our sample reflects the NZ population:

- Q25: How would you best describe the area you live in?

- ( ) Urban

- ( ) Provincial town

- ( ) Urban/rural fringe

- ( ) Rural

- Q26: Which of the following do you identify as?

- ( ) Male

- ( ) Female

- ( ) Gender diverse

- ( ) Prefer not to say

- Q27: What is your ethnicity?

- [ ] Māori

- [ ] European New Zealander

- [ ] Pacific Islander

- [ ] Asian

- [ ] Other: _________________________________________________

- Q28: We just have a few questions to make sure we get a good cross-section of people. What age bracket do you fit into?

- ( ) 18-29 years

- ( ) 30-39 years

- ( ) 40-49

- ( ) 50-59

- ( ) 60-69

- ( ) 70 years and over

- Q29: What household income bracket do you fit into?

- ( ) Less than $20,000

- ( ) $20,000 to $50,000

- ( ) $50,000 to $70,000

- ( ) $70,000 to $100,000

- ( ) more than $100,000

- ( ) Prefer not to say

- Q30: What is your highest level of formal education?

- ( ) Some or all of secondary school

- ( ) Certificate (1-6)

- ( ) Diploma (5-7)

- ( ) Bachelor degree

- ( ) Post-graduate diploma/certificate

- ( ) Post-graduate degree

- ( ) Prefer not to say

- Q31: Do you have young children in your household?

- Yes / No

- Is there anything you would like to tell us about cats?

- [Open response text box here]

- Your response is very important to us so thank you for taking our survey.

Appendix B: Sample Demographics

| Age category (years) | Percentage of respondents | Percentage of New Zealand residents |

|---|---|---|

| 18–29 | 16.3 | 25.5 |

| 30–39 | 19.4 | 16.2 |

| 40–49 | 19.1 | 16.2 |

| 50–59 | 15.7 | 16.2 |

| 60–69 | 14.4 | 13.0 |

| 70 and over | 14.8 | 12.9 |

| Education category | Percentage of respondents | Percentage of New Zealand residents |

|---|---|---|

| Some or all of secondary school | 17.3 | 17.0 |

| Certificate (1–4) | 15.5 | 38.5 |

| Diploma (5–6) | 14.7 | 9.2 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 24.5 | 13.7 |

| Graduate or postgraduate | 23.7 | 9.5 |

| Ethnic category | Percentage of respondents | Percentage of New Zealand residents |

|---|---|---|

| European | 74.3 | 70.2 |

| Māori | 5.8 | 16.5 |

| Pacific Islander | 1.6 | 8.1 |

| Asian | 12.1 | 15.1 |

| Other | 6.2 | 2.7 |

| Income category | Percentage of respondents | Approximate percentage of New Zealand households |

|---|---|---|

| Less than $20,000 | 2.4 | 10.0 |

| $20,000 to $50,000 | 20.7 | 50.0 |

| $50,000 to $70,000 | 15.2 | 20.0 |

| More than $70,000 | 40.3 | 20.0 |

Appendix C: Reliability of Involvement Scales

| Reliability coefficient | |

|---|---|

| Involvement with improving the welfare of cats | 0.847 |

| Involvement with protecting native birds and wildlife from cats | 0.845 |

| Involvement with keeping pet cats indoors at night | 0.864 |

| Involvement with reducing the number of feral cats | 0.826 |

| Involvement with using traps to reduce feral cat numbers | 0.73 |

Appendix D: Demographics

| Variable | Ethnicity | Gender | Age | Income | Education | Young children |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taking good care of all cats is the right thing to do | 0.013 | |||||

| I think protecting native birds and wildlife is the right thing to do | 0.033 | 0.028 | 0.009 | |||

| Involvement with cat welfare | 0.009 | 0.027 | 0.004 | |||

| Involvement with keeping cats indoors | 0.028 | 0.010 | 0.005 | |||

| Involvement with protecting wildlife | 0.015 | 0.004 | 0.013 | 0.003 | ||

| Attitude towards keeping cats indoors | 0.022 | 0.010 | ||||

| Subjective norm keeping cats indoors | 0.008 | 0.008 | ||||

| Attitude towards deterrents | 0.026 | 0.033 | 0.010 | |||

| Attitude towards cats wearing collars | 0.008 | 0.010 | ||||

| Cat owner | 0.016 | 0.017 | 0.031 | 0.010 | 0.010 | |

| Frequency of keeping cat indoors at night | ||||||

| Frequency of cat wearing a collar | 0.034 | 0.022 | 0.022 |

References

- Loss SR, Will T, Marra PP. The impact of free-ranging domestic cats on wildlife of the United States. Nature communications. 2013, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Trouwborst A, McCormack PC, Martínez Camacho E. Domestic cats and their impacts on biodiversity: A blind spot in the application of nature conservation law. People and Nature. 2020, 2, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legge S, Woinarski JCZ, Dickman CR, Murphy BP, Woolley LA, & Calver M We need to worry about Bella and Charlie: the impacts of pet cats on Australian wildlife. Wildlife Research 2020, 47, 523–539. [CrossRef]

- Baker PJ, Molony SE, Stone E, Cuthill IC & Harris S. Cats about town: is predation by free-ranging pet cats Felis catus likely to affect urban bird populations? Ibis 2008, 150 (Suppl. 1), 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Heezik Y, Smyth A, Adams A & Gordon J. Do domestic cats impose an unsustainable harvest on urban bird populations? Biological Conservation 2010, 143, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas RL, Fellowes MD, Baker PJ. Spatio-temporal variation in predation by urban domestic cats (Felis catus) and the acceptability of possible management actions in the UK. PloS one. 2012, 7, e49369. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce SJ, Zito S, Gates MC, Aguilar G, Walker JK, Goldwater N & Dale A Predation and Risk Behaviors of Free-Roaming Owned Cats in Auckland, New Zealand via the Use of Animal-Borne Cameras. Frontiers Veterinary Science 2019, 6, 205. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald E, Milfont T & Gavin M. What drives cat-owner behaviour? First steps towards limiting domestic-cat impacts on native wildlife. Wildlife Research 2015, 42, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall CM, Adams NA, Bradley JS, Bryant KA, Davis AA, Dickman CR, Fujita T, Kobayashi S, Lepczyk CA, McBride EA, Pollock KH, Styles IM, van Heezik Y, Wang F & Calver MC Community Attitudes and Practices of Urban Residents Regarding Predation by Pet Cats on Wildlife: An International Comparison. Plos One 2016, 11, 30–e0151962. [CrossRef]

- Walker JK, Bruce SJ & Dale AR. A Survey of Public Opinion on Cat (Felis catus) Predation and the Future Direction of Cat Management in New Zealand. Animals 2017, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calver M, Thomas S, Bradley S & McCutcheon H Reducing the rate of predation on wildlife by pet cats: The efficacy and practicability of collar-mounted pounce protectors. Biological Conservation 2007, 137, 341–348. [CrossRef]

- Gordon JK, Matthaei C & van Heezik Y. Belled collars reduce catch of domestic cats in New Zealand by half. Wildlife Research 2010, 37, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan SA, Hansen, CM, Ross JG, Hickling GJ, Ogilvie SC & Paterson AM. Urban cat (Felis catus) movement and predation activity associated with a wetland reserve in New Zealand. Wildlife Research 2009, 36, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall CM, Fontaine JB, Bryant KA & Calver MC. Assessing the effectiveness of the Birdsbesafe (R) anti-predation collar cover in reducing predation on wildlife by pet cats in Western Australia. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 2015, 173, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calver MC, Adams G, Clark W & Pollock KH Assessing the safety of collars used to attach predation deterrent devices and ID tags to pet cats. Animal Welfare 2013, 22, 95–105. [CrossRef]

- Woolley CK & Hartley, S. Activity of free-roaming domestic cats in an urban reserve and public perception of pet-related threats to wildlife in New Zealand. Urban Ecosystems 2019, 22, 1123–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrod M, Keown AJ & Farnworth MJ. Use and perception of collars for companion cats in New Zealand. New Zealand Veterinary Journal 2016, 64, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates MC, Walker J, Zito S & Dale A. A survey of opinions towards dog and cat management policy issues in New Zealand. N Z Veterinary Journal 2019, 67, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassett IE, McNaughton EJ, Plank GD & Stanley MC Cat ownership and Proximity to Significant Ecological Areas Influence Attitudes Towards Cat Impacts and Management Practices. Environmental Management 2020, 66, 30–41. [CrossRef]

- Linklater WL, Farnworth MJ, van Heezik Y, Stafford KJ & MacDonald EA. Prioritizing cat-owner behaviors for a campaign to reduce wildlife depredation. Conservation Science and Practice 2019, 1, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman-Worsley R, Finka LR, Ward SJ, Farnworth MJ. Indoors or Outdoors? An International Exploration of Owner Demographics and Decision Making Associated with Lifestyle of Pet Cats. Animals 2021, 11, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rand J, Ahmadabadi Z, Norris J, Franklin M. Attitudes and Beliefs of a Sample of Australian Dog and Cat Owners towards Pet Confinement. Animals. 2023, 13, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eeden LM, Hames F, Faulkner R, Geschke A, Squires ZE, McLeod EM. Putting the cat before the wildlife: Exploring cat owners’ beliefs about cat containment as predictors of owner behavior. Conservation Science and Practice. 2021, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, JW. An Introduction to Motivation. Van Nostrand: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1964.

- Elliot, AJ. The hierarchical model of approach-avoidance motivation. Motivation and emotion 2006, 30, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly L, Kerr G, Drennan J. Triggers of engagement and avoidance: Applying approach-avoid theory. Journal of marketing communications. 2018, 26, 488–508. [Google Scholar]

- NCMSG. New Zealand National Cat Management Strategy Group report. 2020. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d1bf13a3f8e880001289eeb/t/5f6d986d7bea696c449fa5a7/1601017986875/NCMSG_Report_August+2020.pdf.

- Derbaix C, Vanden Abeele P. Consumer inferences and consumer preferences. The status of cognition and consciousness in consumer behavior theory. International Journal of Research in Marketing 1985, 2, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priluck R, Till BD. The role of contingency awareness, involvement and need for cognition in attitude formation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 2004, 32, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herr PM, Fazio RH. The attitude-to-behavior process: implications for consumer behavior. In Advertising exposure, memory, and choice; Mitchel, A.A. Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1993; pp. 119–140.

- McLeod LJ, Hine DW, Bengsen AJ. Born to roam? Surveying cat owners in Tasmania, Australia, to identify the drivers and barriers to cat containment. Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 2015, 122, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaine G, Murdoch H, Lourey R & Bewsell D. A framework for understanding individual response to regulation. Food Policy 2010, 35, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaine G, Kirk N, Kannemeyer R, Stronge D & Wiercinski B. Predicting People’s Motivation to Engage in Urban Possum Control. Conservation 2021, 1, 196–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaine G, Wright V. Attitudes, Involvement and Public Support for Pest Control Methods. Conservation. 2022, 2, 566–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaine G, Wright V Motivation, Intention and Opportunity: Wearing Masks and the Spread of COVID-19. COVID 2023, 3, 601–621. [CrossRef]

- Assael, H. 1998. Consumer behavior and marketing action. Southwestern College Publishing.

- Stankevich, A. Explaining the consumer decision-making process: Critical literature review. Journal of international business research and marketing. 2017, 2, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, B. Measuring purchase-decision involvement. Psychology & Marketing 1989, 6, 147–163. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, RL. Need fulfilment in a consumer satisfaction context. Pages 135-161 in Oliver RL, ed. Satisfaction: a behavioral perspective on the consumer. Irwin/McGraw-Hill. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Broderick, AJ. A cross-national study of the individual and national–cultural nomological network of consumer involvement. Psychology & Marketing. 2007, 24, 343–374. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke W, Vackier I. Profile and effects of consumer involvement in fresh meat. Meat Science 2004, 67, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dholakia, UM. A motivational process model of product involvement and consumer risk perception. European Journal of Marketing 2001, 35, 1340–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celsi RL, Olson JC. The role of involvement in attention and comprehension processes. The Journal of Consumer Research 1988, 15, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poiesz TBC, Bont CJPM. Do we need involvement to understand consumer behavior? Advances in Consumer Research 1995, 22, 448–452.

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Attitude-behaviour relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin 1977, 84, 888–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, RP. Consumer Action: Automaticity, Purposiveness and Self-Regulation. In Review of Marketing Research; Malhotra, N.K., Ed.; M.E. Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 2006; Volume 2, pp. 3–42. [Google Scholar]

- Krosnick, JA. Attitude importance and attitude change. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1988, 24, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, MK. The impact on consumer buying behaviour: Cognitive dissonance. Global Journal of Finance and Management. 2014, 6, 833–840. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd DL, Prentice-Dunn S, Rogers RW. A Meta-Analysis of Research on Protection Motivation Theory. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 2000, 30, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaine, G.; Wright, V.; Greenhalgh, S. Motivation, Intention and Action: Wearing Masks to Prevent the Spread of COVID-19. COVID 2022, 2, 1518–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, K.A. dynamic theory of personality: Selected papers. McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA. 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot, AJ. Approach and avoidance motivation and achievement goals. Educational Psychologist 1999, 34, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend JT, Busemeyer JR. 1989. Approach-avoidance: Return to dynamic decision behavior. In C. Izawa (Ed.), Current issues in cognitive processes: The Tulane Flowerree Symposium on Cognition (pp. 107–133). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Penz E, Hogg MK The role of mixed emotions in consumer behaviour: Investigating ambivalence in consumers’ experiences of approach-avoidance conflicts in online and offline settings. European Journal of Marketing. 2011, 45, 104–132. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, R. Managing Yourself: Bridging Psychological Distance. Harvard Business Review 2015, 93, 116–119. [Google Scholar]

- Förster, J. Higgins, E.T., Idson, L.C. Approach and Avoidance Strength During Goal Attainment: Regulatory Focus and the “Goal Looms Larger” Effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1998, 75, 1115–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent G, Kapferer J-N. Measuring consumer involvement profiles. Journal of Marketing Research 1985, 22, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmines EG, Zeller RA. 1979. Reliability and validity assessment. Sage.

- Elliott A, Howell TJ, McLeod EM, Bennett PC. Perceptions of responsible cat ownership behaviors among a convenience sample of Australians. Animals. 2019, 9, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toukhsati, S.R.; Young, E.; Bennett, P.C.; Coleman, G.J. Wandering cats: Attitudes and behaviors towards cat containment in Australia. Anthrozoos 2012, 25, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod LJ, Hine DW, Bengsen AJ, Driver AB. Assessing the impact of different persuasive messages on the intentions and behaviour of cat owners: A randomised control trial. Preventive veterinary medicine. 2017, 146, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roetman P, Tindle H & Litchfield C. Management of Pet Cats: The Impact of the Cat Tracker Citizen Science Project in South Australia. Animals 2018, 8, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma GC, McLeod LJ. Understanding the Factors Influencing Cat Containment: Identifying Opportunities for Behaviour Change. Animals. 2023, 13, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod LJ, Evans D, Jones B, Paterson M, Zito S. Understanding the relationship between intention and cat containment behaviour: A case study of kitten and cat adopters from RSPCA Queensland. Animals 2020, 10, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNaughton N, DeYoung CG, Corr PJ. Approach/avoidance. In Neuroimaging personality, social cognition, and character: Absher Jr & Cloutier J Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA. 2016.

- Kunda Z The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin. 1990, 108, 480–498. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawara SP Who Is responsible, the incumbent or the former president? motivated reasoning in responsibility attributions. Presidential Studies Quarterly 2015, 45, 110–131. [CrossRef]

- Kirk, R Effect magnitude: A different focus. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference 2007, 137, 1634–1646. [CrossRef]

- Richardson JTE. Eta squared and partial eta squared as measures of effect size in educational research. Educational Research Review 2011, 6, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Keeping cats indoors is unnatural and harmful | Wandering is dangerous for cats | Cats are a health risk | Cats are a danger to wildlife | Preventive devices are not effective | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I think pet cats should be kept inside at night for their own safety | -0.46 | 0.65 | |||

| I think wandering cats are a danger to other cats | 0.69 | ||||

| I think wandering cats are a danger to themselves | 0.66 | ||||

| If pet cats are outside at night, they could be attacked by feral cats | 0.72 | ||||

| Keeping cats inside at night will only protect birds and wildlife if everyone does it | 0.32 | ||||

| I think its unnatural to keep cats inside | 0.73 | -0.30 | |||

| It’s difficult to keep cats inside at night | 0.74 | ||||

| It’s natural for cats to hunt birds and wildlife | 0.39 | 0.62 | |||

| Pet cats are not really a danger to native birds and wildlife | 0.34 | -0.70 | |||

| Cats in urban areas are not really a danger to native birds and wildlife | 0.42 | -0.66 | |||

| I think cats are a danger to wildlife | 0.40 | 0.63 | |||

| I think cats are a nuisance | -0.41 | 0.53 | 0.36 | ||

| Cats transmit diseases and parasites to other cats and animals | 0.79 | ||||

| Cats can transmit diseases and parasites to people | 0.81 | ||||

| Collars with warning devices like bells don’t work | 0.77 | ||||

| Collars can be a danger to cats | 0.60 | 0.30 | |||

| Some cats just won’t wear a collar | 0.65 | ||||

| I don’t think deterrents are likely to be effective | 0.72 |

| Have a cat | Had a cat | Have never had a cat | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I think pet cats should be kept inside at night for their own safety** | 3.41 | 3.59 | 3.81 |

| I think wandering cats are a danger to other cats | 3.57 | 3.61 | 3.59 |

| I think wandering cats are a danger to themselves | 3.35 | 3.42 | 3.47 |

| If pet cats are outside at night, they could be attacked by feral cats** | 3.71 | 3.64 | 3.54 |

| Keeping cats inside at night will only protect birds and wildlife if everyone does it | 3.49 | 3.51 | 3.64 |

| I think its unnatural to keep cats inside** | 3.14 | 2.71 | 2.57 |

| It’s difficult to keep cats inside at night** | 3.24 | 2.90 | 2.75 |

| It’s natural for cats to hunt birds and wildlife** | 3.95 | 3.98 | 3.82 |

| Pet cats are not really a danger to native birds and wildlife** | 2.59 | 2.05 | 2.10 |

| Cats in urban areas are not really a danger to native birds and wildlife** | 2.88 | 2.27 | 2.35 |

| I think cats are a danger to wildlife** | 3.54 | 4.08 | 3.99 |

| I think cats are a nuisance** | 1.98 | 2.82 | 3.53 |

| Cats transmit diseases and parasites to other cats and animals** | 3.43 | 3.56 | 0.79 |

| Cats can transmit diseases and parasites to people** | 3.20 | 3.47 | 3.63 |

| Collars with warning devices like bells don’t work** | 2.87 | 2.57 | 2.75 |

| Collars can be a danger to cats** | 3.33 | 2.68 | 2.46 |

| Some cats just won’t wear a collar** | 3.64 | 2.99 | 2.94 |

| I don’t think deterrents are likely to be effective** | 2.90 | 2.67 | 2.72 |

| Have a cat | Had a cat | Have never had a cat | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Involvement with cat welfare** | 3.98 | 3.60 | 3.26 |

| Involvement with protecting native birds and wildlife | 4.08 | 4.09 | 4.04 |

| Involvement with keeping cats indoors at night** | 3.27 | 3.50 | 3.51 |

| Attitude towards cat welfare** | 4.13 | 3.87 | 3.54 |

| Attitude towards protect native birds and wildlife** | 4.21 | 3.51 | 3.60 |

| Attitude towards keeping cats indoors at night** | 3.49 | 3.92 | 4.02 |

| Attitude towards cats wearing collars** | 3.61 | 4.14 | 4.04 |

| Attitude towards area deterrents** | 3.85 | 4.17 | 4.04 |

| Prepared to take some responsibility for protecting wildlife* | 3.87 | 3.89 | 3.73 |

| Prepared to take action to protect wildlife* | 3.70 | 3.84 | 3.78 |

| Prepared to make sacrifices to protect wildlife** | 3.53 | 3.74 | 3.63 |

| Prepared to work with others to protect wildlife** | 4.10 | 4.31 | 4.16 |

| Frequency of keeping cats indoors at night1 | 19.7 | ||

| Frequency of having cat wear a collar2 | 26.0 |

| Strength of attitude towards keeping cats indoors | Strength of attitude towards having cats wear collars | Strength of attitude towards using deterrents | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Involvement with cat welfare | -0.139 (p<0.001) |

-0.220 (p<0.001) |

-0.238 (p<0.001) |

| Involvement with protecting native birds and wildlife | 0.111 (p<0.001) |

0.348 (p<0.001) |

0.412 (p<0.001) |

| Involvement with keeping cats indoors at night | 0.391 (p<0.001) |

||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.15 |

| F-Test significance | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Involvement with keeping cats indoors at night | Attitude towards keeping cats indoors | Attitude towards having cats wear collars | Attitude towards using deterrents | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Involvement with cat welfare | 0.188 (p<0.001) |

0.036 (p<0.001) |

ns | ns |

| Involvement with protecting native birds and wildlife | 0.244 (p<0.001) |

ns | 0.062 (p=0.003) |

0.065 (p=0.002) |

| Attitude towards cat welfare | ns | ns | -0.059 (p=0.002) |

|

| Attitude towards protect native birds and wildlife | 0.056 (p<0.001) |

0.126 (p<0.001) |

0.298 (p<0.001) |

|

| Cats are a danger to wildlife | 0.167 (p<0.001) |

0.287 (p<0.001) |

0.272 (p<0.001) |

0.241 (p<0.001) |

| Wandering is dangerous for cats | 0.323 (p<0.001) |

0.405 (p<0.001) |

0.075 (p<0.001) |

0.101 (p<0.001) |

| Keeping cats indoors is unnatural and harmful | -0.399 (p<0.001) |

-0.579 (p<0.001) |

-0.327 (p<0.001) |

-0.154 (p<0.001) |

| Cats are a health risk | 0.136 (p<0.001) |

0.110 (p<0.001) |

0.174 (p<0.001) |

0.101 (p<0.001) |

| Protective measures are ineffective | 0.136 (p<0.001) |

0.039 (p=0.001) |

-0.276 (p<0.001) |

-0.201 (p<0.001) |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.50 | 0.62 | 0.39 | 0.37 |

| F-Test significance | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Prepared to take some responsibility | Prepared to act | Prepared to make sacrifices | Important to work together | Cats indoors at night | Cats wear collars | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Involvement with cat welfare | 0.044 (p=0.046) |

ns | ns | ns | 0.129 (p<0.001) |

ns |

| Involvement with protecting native birds and wildlife | 0.217 (p<0.001) |

0.270 (p<0.001) |

0.292 (p<0.001) |

0.187 (p<0.001) |

-0.090 (p<0.001) |

ns |

| Attitude towards cat welfare | 0.061 (p=0.002) |

ns | -0.041 (p=0.050) |

0.036 (p=0.024) |

ns | |

| Attitude towards protect native birds and wildlife | 0.426 (p<0.001) |

0.413 (p<0.001) |

0.366 (p<0.001) |

0.601 (p<0.001) |

ns | |

| Attitude towards keeping cats indoors at night | 0.451 (p<0.001) |

|||||

| Attitude towards collars | 0.381 (p<0.001) |

|||||

| Subjective norm for keeping pet cats indoors at night | 0.176 (p<0.001) |

|||||

| Keeping cats inside is difficult | -0.201 (p<0.001) |

|||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.14 |

| F-Test significance | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Beta | Standard error | Standardised beta | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference in desirability of protecting wildlife and desirability of keeping cats indoors at night | 0.022 | 0.011 | 0.077 | 0.042 |

| Difference in desirability of cat welfare and desirability of keeping cats indoors at night | 0.065 | 0.010 | 0.227 | <0.001 |

| Psychological distance to keeping cats indoors at night | -0.357 | 0.036 | -0.281 | <0.001 |

| Intercept | 2.140 | 0.229 | <0.001 | |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.48 | |||

| F-Test significance | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).