Introduction

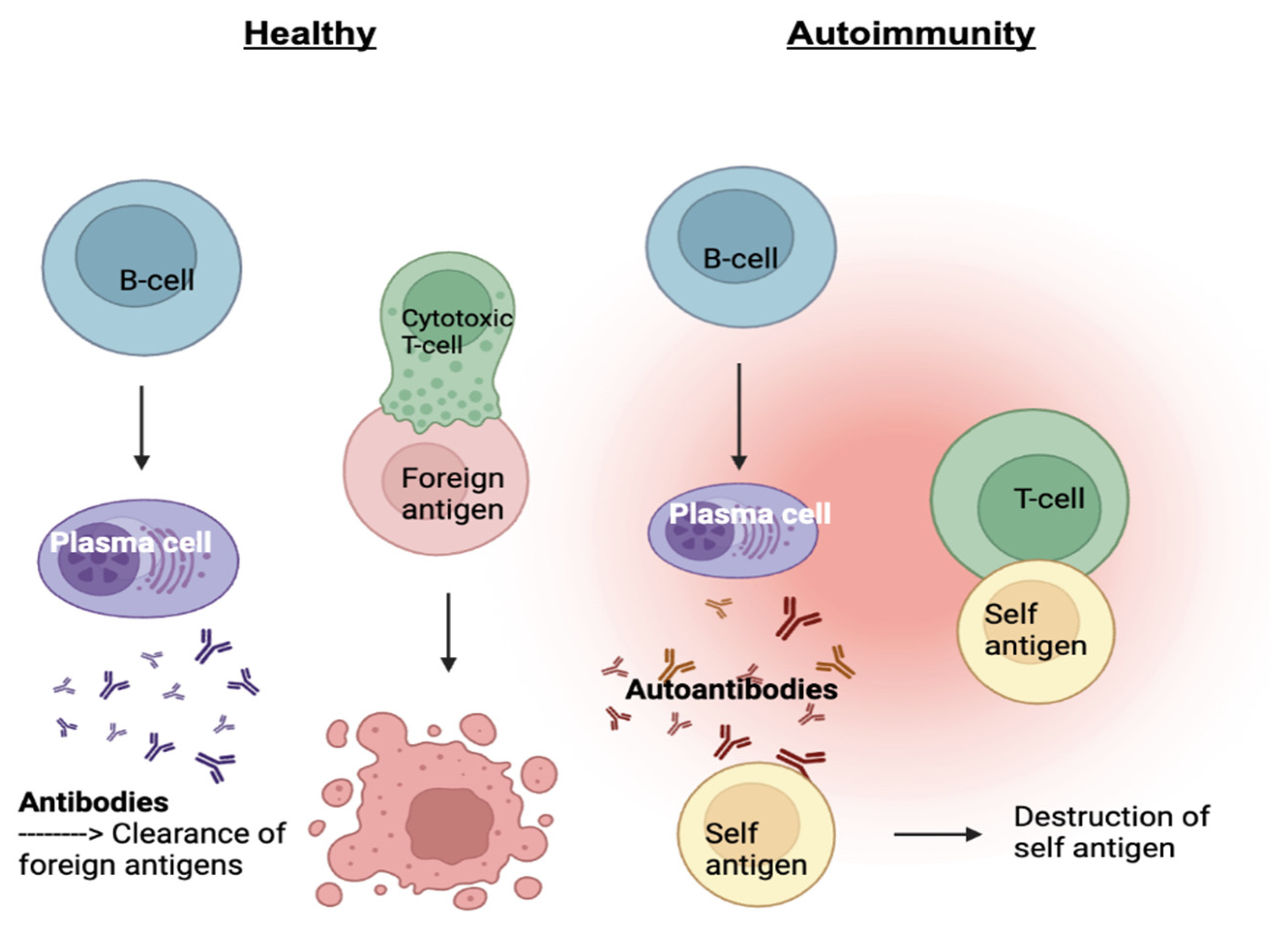

Lupus is a chronic autoimmune disease that causes inflammation and damage to various organs and tissues in the body. There are four different subtypes of lupus: systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), drug-induced lupus, cutaneous lupus, and neonatal lupus. SLE is characterized by the production of autoantibodies, proteins formed by plasma cells that specifically respond to self-antigens. In a healthy immune system, antibodies are formed in response to a foreign antigen such as a pathogen in an attempt to target and remove the pathogen. In an autoimmune disease, our immune system has mistaken our own tissues as a foreign antigen which leads to autoantibodies being generated to attack our own bodies

(Figure 1).¹ As the two main white blood cell types of the adaptive immune system, B and T cells work together to protect the body from foreign pathogens. T-cells eliminate cancerous or infected cells directly, while B-cells develop into plasma cells and produce antibodies. Other immune cells produce signaling molecules such as interferon-gamma (IFNg) and B-cell lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS) which bind to B and T-cell receptors acting as inflammatory mediators. Type I interferons activate T-cells or natural killer cells which can directly kill our tissues and help activate B-cells to produce autoantibodies. BLyS binds to B-cells and promotes cell survival. When these two molecules are in excess, autoantibodies are produced, targeting specific components of the cell nucleus, creating inflammation and damage within tissues and organs.²⁻³ This occurs when cells undergo a cell death process called necrosis, in which the mitochondria and cytoplasm swell up in the presence of packaged DNA in response to uncontrolled external factors such as autoantibodies, leading to SLE.²

As a result of multiple anti-nuclear antibodies broadly targeting DNA, patients often experience a wide range of symptoms including fatigue, hair loss, and joint pain. Due to the broad nature of symptoms, lupus may be mistaken for other autoimmune diseases, making accurate diagnosis difficult. Moreover, a lack of understanding around the cause(s) of lupus has hindered development of novel treatments. In the past, a more general approach of prescribing broadly immunosuppressive drugs has been employed to manage disease. These blanketed agents work by targeting the symptoms and suppressing the immune system as a whole. Indeed, these drugs, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), are commonly used in various medical conditions where an overactive immune system can cause harm.⁴⁻⁵

The increase in the understanding of lupus has allowed for more efficient treatment options. A new approach of selective immunotherapies such as monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that specifically target certain parts of the immune system are proving to be more successful in treating lupus in the long term than the broadly suppressive drugs like NSAIDs.⁶⁻⁸ Recent clinical trials on anifrolumab and belimumab have shown a considerable improvement in SRI response (the decrease in the rate of SLE) when compared to standard therapy which consists of a blanket approach.⁶⁻⁷ This is due to their selective nature of earmarking specific cells and molecules that are increasing autoimmunity. The two main focuses of these drugs are: type I interferons, to which anifrolumab corresponds, and B-cell lymphocyte stimulator, which belimumab neutralizes. Limiting these molecules decreases the production of autoantibodies and activated T cells, therefore decreasing lupus activity.⁶⁻⁷

The Deficiencies of the Blanket Immunosuppressive Drugs:

Prior to 2011, all FDA-approved drugs for the treatment of lupus did not include a selective approach that focuses on improving the activity of the immune system in the long term.⁹ Unfortunately, the majority of drug development for lupus has been focused on the blanket approach method. These standard therapies known as blanket immunosuppressive drugs are a common treatment approach for managing lupus symptoms that includes the use of corticosteroids and/or antimalarial therapy.⁹ Also known as steroids, corticosteroids aim to reduce inflammation by mimicking the function of cortisol, a hormone naturally produced by the adrenal glands.¹⁰ This therapy reduces the production of cytokines and adhesion molecules that cause inflammation through deactivating inflammatory genes.¹⁰⁻¹¹ Today, nearly 88% of patients with SLE are treated with these therapies, making corticosteroids a popular form of prescription drug for lupus.¹¹ These drugs share similarities with NSAIDS such as ibuprofen and naproxen which work by suppressing the immune system's response, thereby easing general symptoms such as inflammation and joint pain. They are often supplied as tablets in over the counter and prescription form, providing short term relief from symptoms such as joint pain and fever. While naproxen provides longer lasting pain relief with fewer doses, ibuprofen requires more doses to work to its full efficacy. Ultimately, both medications work similarly and thus share similar side effects such as stomach upset, nausea, and dizziness.⁴⁻⁵ NSAIDs function to relieve pain by blocking cyclooxygenase (COX), which is an enzyme that produces prostaglandins.⁴ As a result, the prostaglandin production is reduced, which alleviates pain and inflammation. Despite their initial effectiveness, blanket immunosuppressive drugs have limitations when it comes to the long-term management of lupus. One of the key drawbacks of them is their lack of specificity in targeting the underlying causes of lupus. Although the COX enzyme is blocked, specific components of the immune system must be targeted to properly treat lupus.

Moving Beyond Blanket Approaches: Advancements in Lupus Treatments Targeting the Immune System

Recent studies have found that selective, targeted immunotherapies that modulate specific components of the immune system are more effective in treating lupus. Monoclonal antibodies are lab-generated proteins engineered to mimic the antibodies created by our own immune system, targeting single molecules or cells. They are commonly used in conditions such as cancer, covid-19, osteoporosis, etc. ⁸ Monoclonal antibodies such as Belimumab and Anifromulab have shown greater long-term effectiveness in managing lupus compared to blanket immunosuppressive drugs. Both Phase 3 and 4 clinical trials of selective immunotherapies, such as anifrolumab and belimumab, have been effective examples of these agents.⁶⁻⁷ Their efficacy lies in their ability to target and suppress precise molecules of the immune system. The binding affinity, or strength of the bond between antibody and antigen-binding, enables pharmaceutical chemists to modify antibodies to bind to a specific target, such as a lupus threatening antigen. This ensures that necessary cells or molecules are targeted.

Anifrolumab is a monoclonal

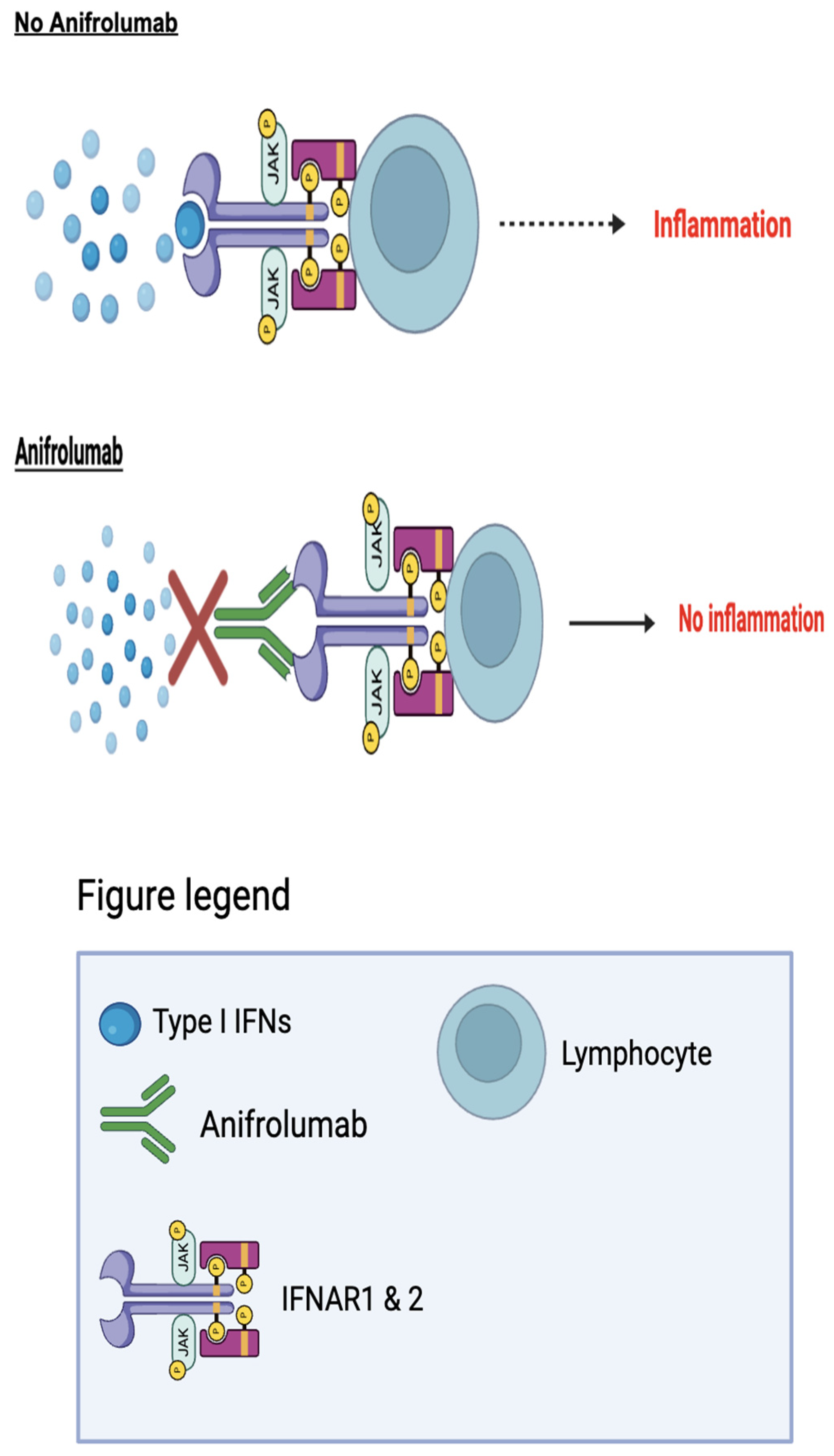

Anifrolumab (Saphnelo), was first developed by the global biopharmaceutical company AstraZeneca to treat SLE. Anifrolumab works by blocking the activity of type I interferons (IFNs).¹²⁻¹³ In SLE, type I IFNs are produced by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), a group of immune cells in which antigens are processed and presented to T and B-cells. An increase in the exposure of inflammatory signaling molecules such as type I IFNs causes the T and B-cells to produce autoantibodies. These self-acting antibodies disrupt the homeostasis of the immune system, ultimately causing autoimmunity.¹

antibody that targets the type I interferon receptor which consists of two transmembrane proteins: IFNAR1 and IFNAR2. The success of the drug is linked to the blocking of type I interferons. Because type I interferons are cytokines involved in inflammatory pathways, the targeting of them is successful in treating lupus because they are specific to the development of inflammation, rather than the overall symptom of inflammation. Given in the form of an injection, the anifrolumab antibody binds to IFNAR1 of the receptor, blocking the activity of all type I interferons, including IFN-alpha, IFN-beta, and IFN-omega (

Figure 2).¹ Although this antibody is relatively new, there has been successful trials that show its effectiveness. A randomized placebo controlled Phase III extension trial among two different studies aimed to test the long-term safety and tolerability of Anifrolumab in active SLE. Patients were given a 300mg dose of anifrolumab, which was compared to a group given the placebo drug.⁷ The SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI), a system used to measure disease activity by weighing symptoms based on their severity, was used in this study. The rates from both studies were adjusted to accurately reflect the results of the scores measuring the severity of the SLE which were 8.5 with anifrolumab, while 11.2 with placebo.⁷ The combined anifrolumab 300mg group showed significant improvement in the severity scores compared to the placebo control group. Patients who were given anifrolumab had a decrease in severity from 11.4 ± 3.8, to 5.1 ± 3.5. Meanwhile, patients given placebo only decreased to 6.0 ± 4.1.⁷ This decrease in severity accounted for the decrease in symptoms such as overactive immune flare-ups. The average flare-up rate for the combined anifrolumab group was 10%, while the placebo group had a rate of 20%.⁷ This data demonstrates that the medication is aligned with a lower cumulative patient use of glucocorticoid, a common blanket immunosuppressive drug. Overall, this suggests a long-term effectiveness of anifromulab in SLE.

Belimumab

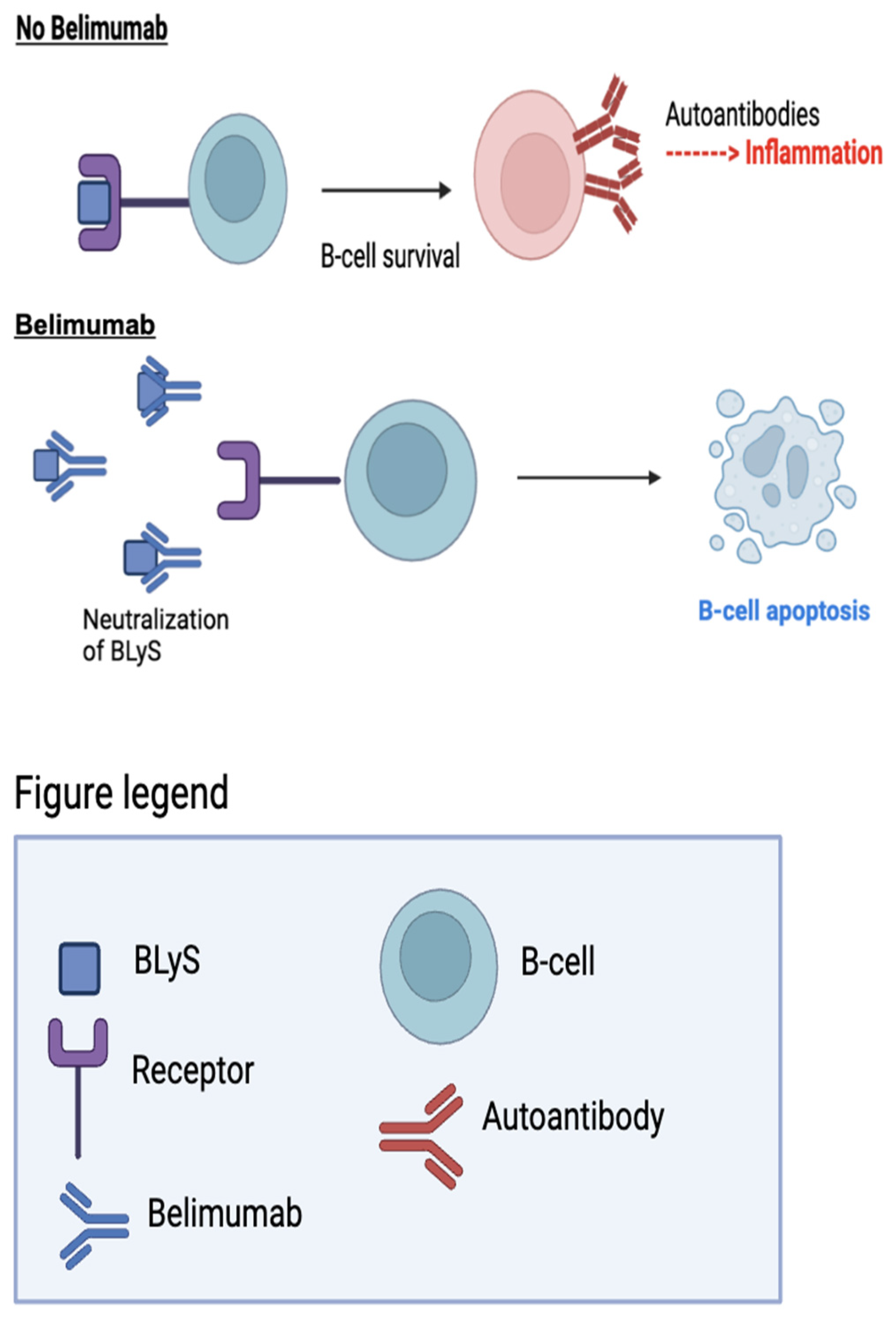

Belimumab (Benlysta) was developed to address humoral immunodeficiencies caused by failed B-cell development.² BLyS consists of ligands and receptors that act as checkpoints to regulate antibody production by B-cells. In the absence of BLyS, naive B-cells fail to develop and mature into plasma cells, which produce antibodies.¹⁴ The targeting of BLyS is necessary for treating autoimmune diseases because BLyS binds to autoreactive B-cells, promoting B-cell survival and the production of autoantibodies. This can cause inflammation and lead to autoimmune diseases like SLE.¹⁴

Belimumab neutralizes BLyS by binding to it before it reaches the B-cell, leading to cell apoptosis and the prevention of potential autoantibodies (

Figure 3).¹⁴ In 2011, Belimumab gained FDA approval for its effectiveness in SLE in correspondence to its successful results in lupus patients.² In a randomized, controlled Phase III trial, the safety and efficacy of belimumab in addition to standard therapy was assessed against standard therapy alone in patients with SLE.⁶ The study randomized patients into groups receiving either 1 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg of belimumab, or the placebo control, in addition to standard therapy. The results demonstrated that patients receiving 10 mg/kg of belimumab, in combination with standard therapy, experienced the greatest improvement, with a 43% SRI response rate at week 52, compared to a 33.5% rate for the placebo.⁶ The group receiving 1 mg/kg of Belimumab plus standard therapy achieved a response rate of 40.6%. These findings highlight the superior effectiveness of belimumab compared to broad immunosuppressive drugs in treating SLE. Additionally, the use of belimumab resulted in a reduction in flare-up rates, with a decrease of 0.13% for patients receiving 10 mg/kg and 0.023% for those receiving 1 mg/kg.⁶ Overall, belimumab at 10 mg/kg in combination with standard therapy, demonstrated a favorable response, improving SRI response rate, reducing disease activity, and demonstrating tolerability in patients with SLE.