1. Introduction

This article attempts to steer design research processes towards a space for social interaction and exchange, making it a slice of the ontological world. We are conscious that this not only requires perseverance, but also calls for collaboration to help translate meanings untangled in the panoply of languages and experiences that makes everydayness (Lefebvre, 2014), which is often depicted as uncertain and complex. New conceptual lenses to magnify micro interactions are in demand to assist us unveil events of the everyday practices. However, this might not suffice since new forms of engagement are also required. Scharmer (2009) appeals for more awareness and self-consciousness to allow individuals and groups to shift from their inner place and come to fruition and embrace the future, it being preposterous, possible, plausible, projected, probable or preferable (Voros, 2017). These two dialogical perspectives suggest that when people adopt a prospective approach and begin to operate from a future space of possibility, they will embrace a new lifeworld attitude (presencing) which encompasses new “meanings and shared languages that allow individuals to empathically interact with one another [and experiment] new forms of figuration and meaning” (Kettley & Smyth, 2007, p. 1). Drawing on Goodman (1978), we want to conceptualize departing from the first-person research perspective. This is referred to as experiential research, placing the individual experience at the centre of inquiry. This should allow us to observe but also to purposefully inhabit, embody, and explore a particular context, problem, or question. We expect this will enable engagement with dimensions of human experience, which can be harder to access through traditional third-person methods. Essentially, this kind of research involves everyone taking part to reflect on their own experiences, thoughts, feelings, and actions in relation to the problems or questions they are investigating. It can help researchers to get ‘inside’ the experience of the users, to better understand and meet their needs. It can also lead to new insights and innovations that might not be apparent from a more detached perspective. Consequently, this paper set out to identify ways to promote healthier working lives and ageing for older care workers in Scotland. The paper contributes two perspectives to de field of Design and Healthcare scholarship; the first is a novel methodological approach, the Ripple Framework, developed to help improve new forms of social interaction between designers and co-designer communities based on trust and non-judgemental relationship, here defined as the relational approach. In that way it increases chances to tackle the unanticipated phenomena (e.g., ‘wicked problem’). The second contribution consists in illustrating how valuation (Social, Cultural and Economic) can be derived from a more designerly way of knowing (Cross, 1982) and use them to inform policy making (Dow, Comber, & Vines, 2019).

2. Materials and Methods

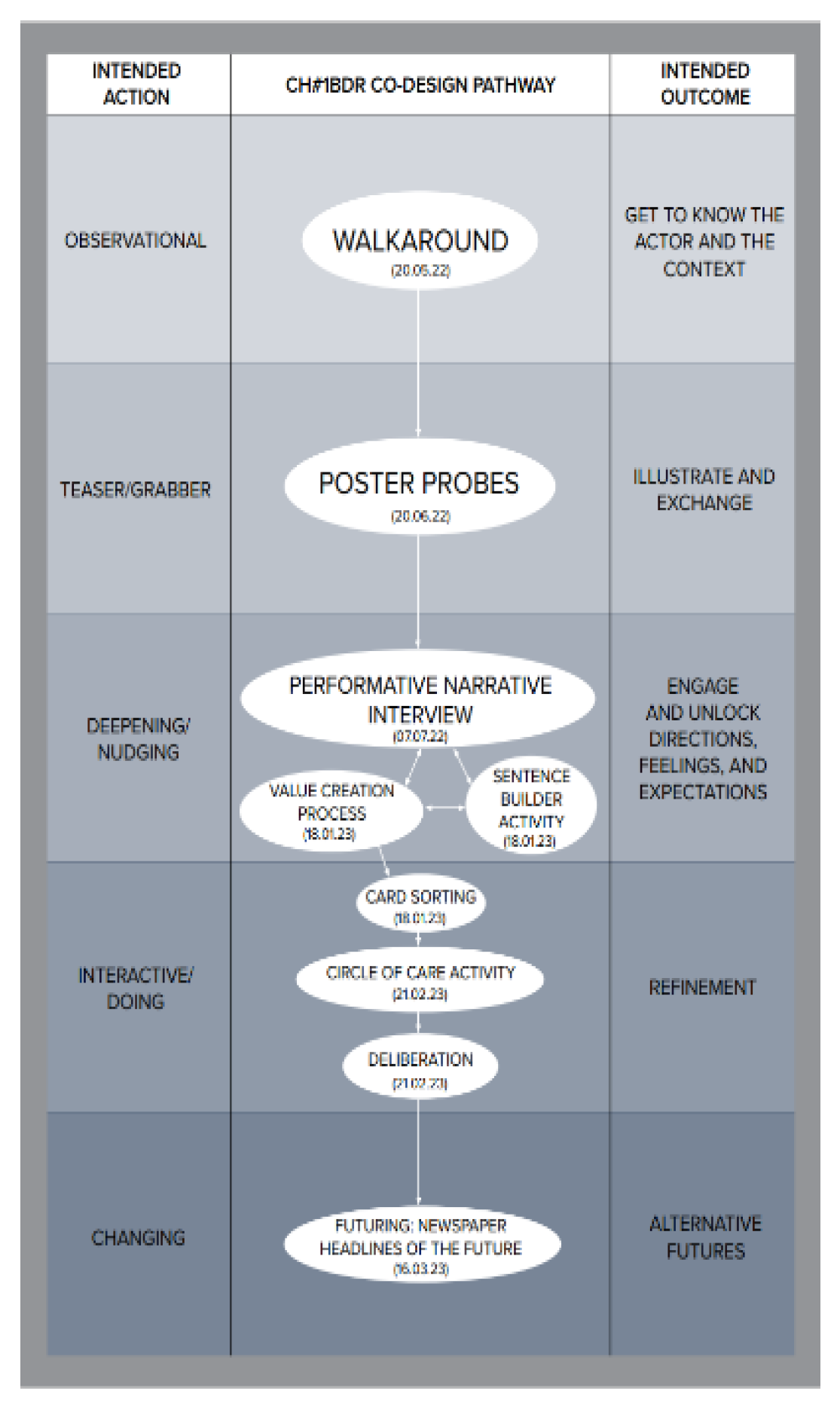

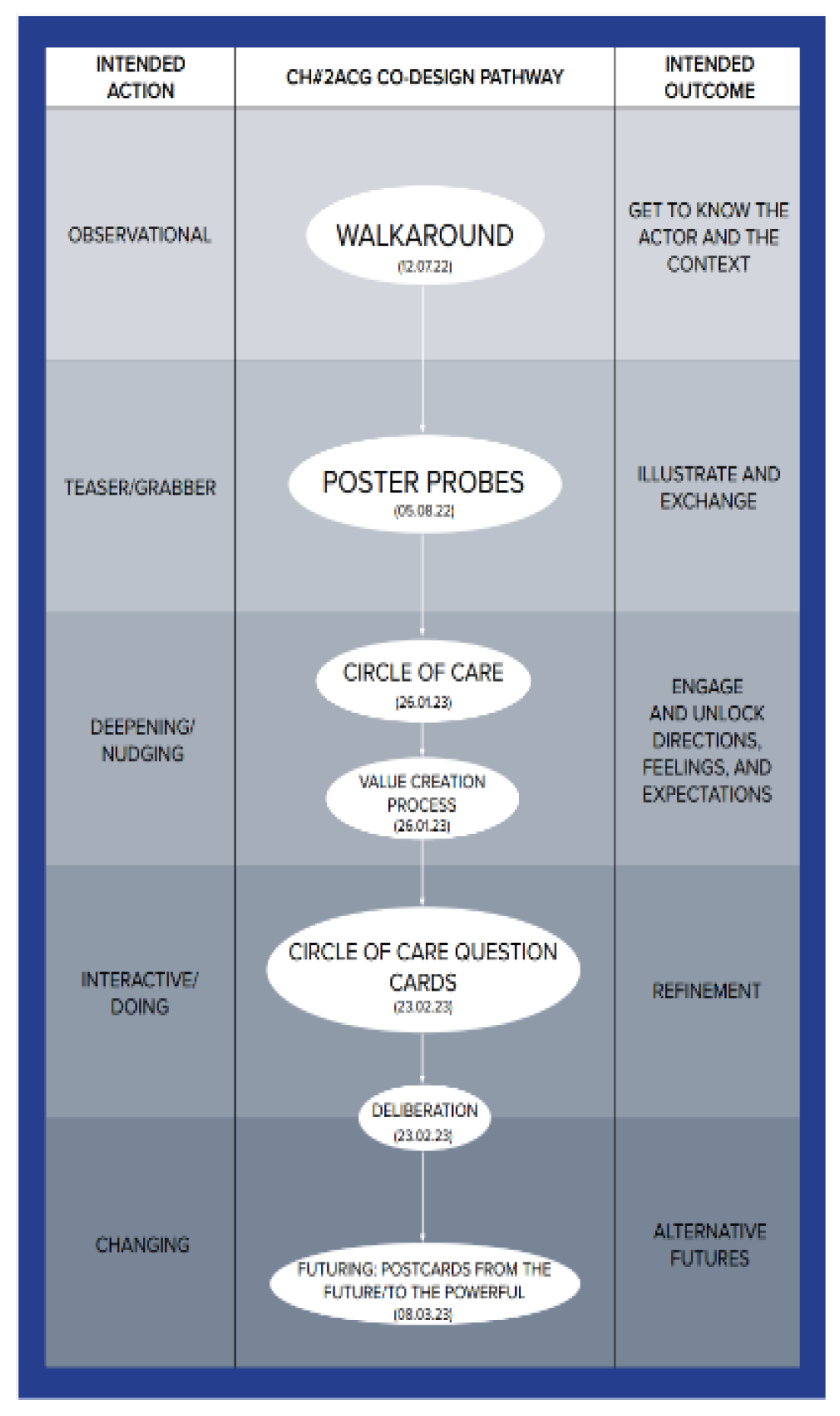

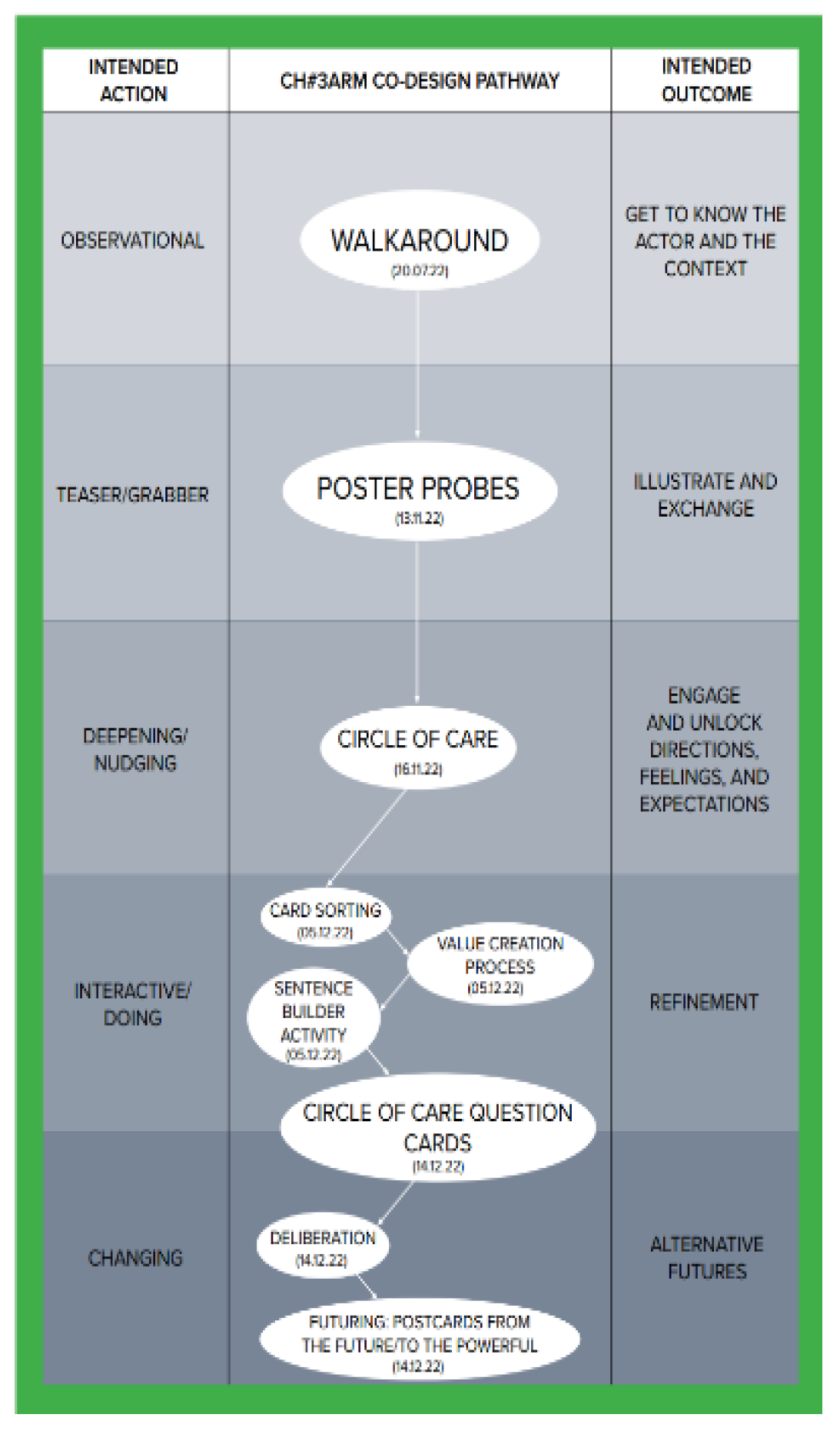

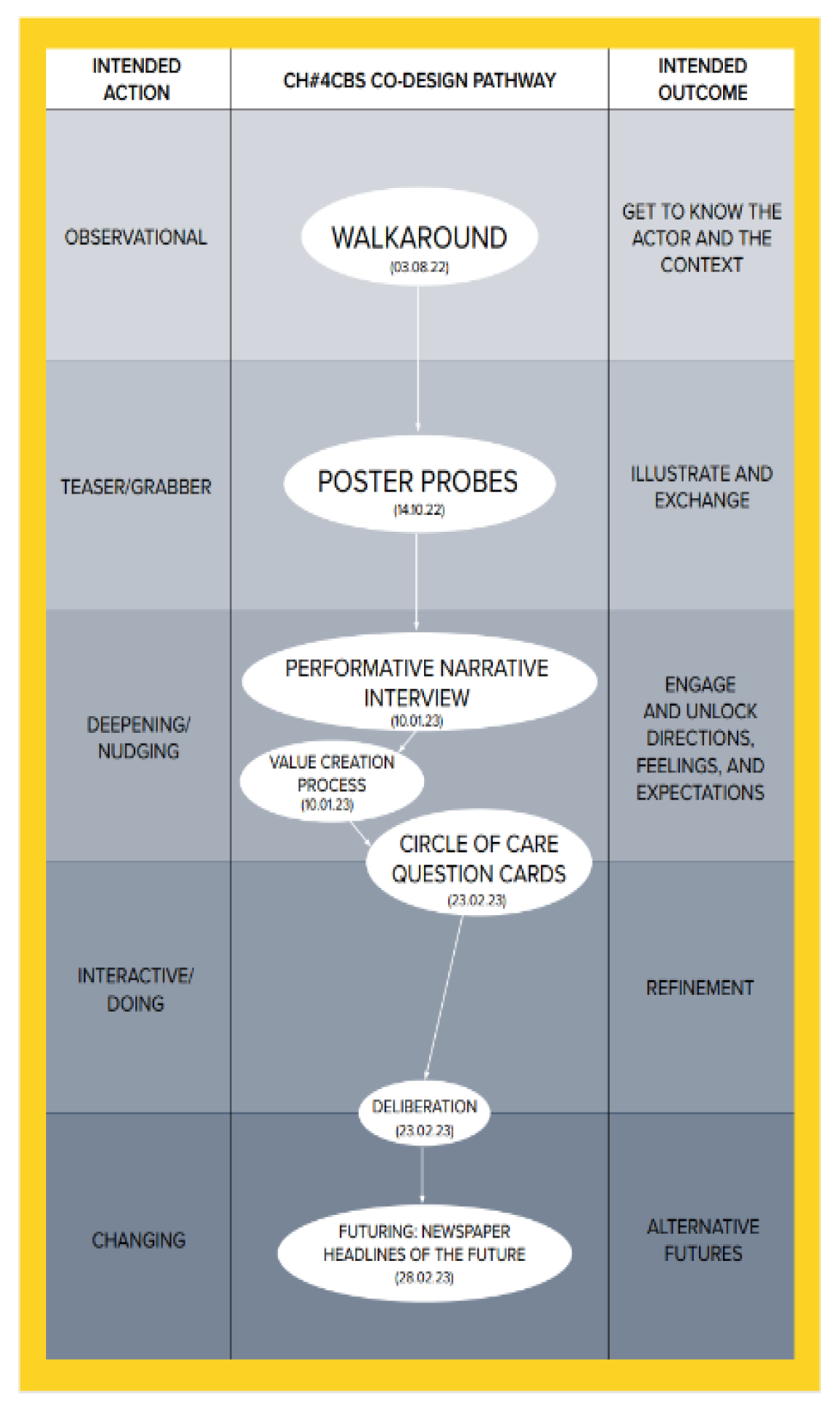

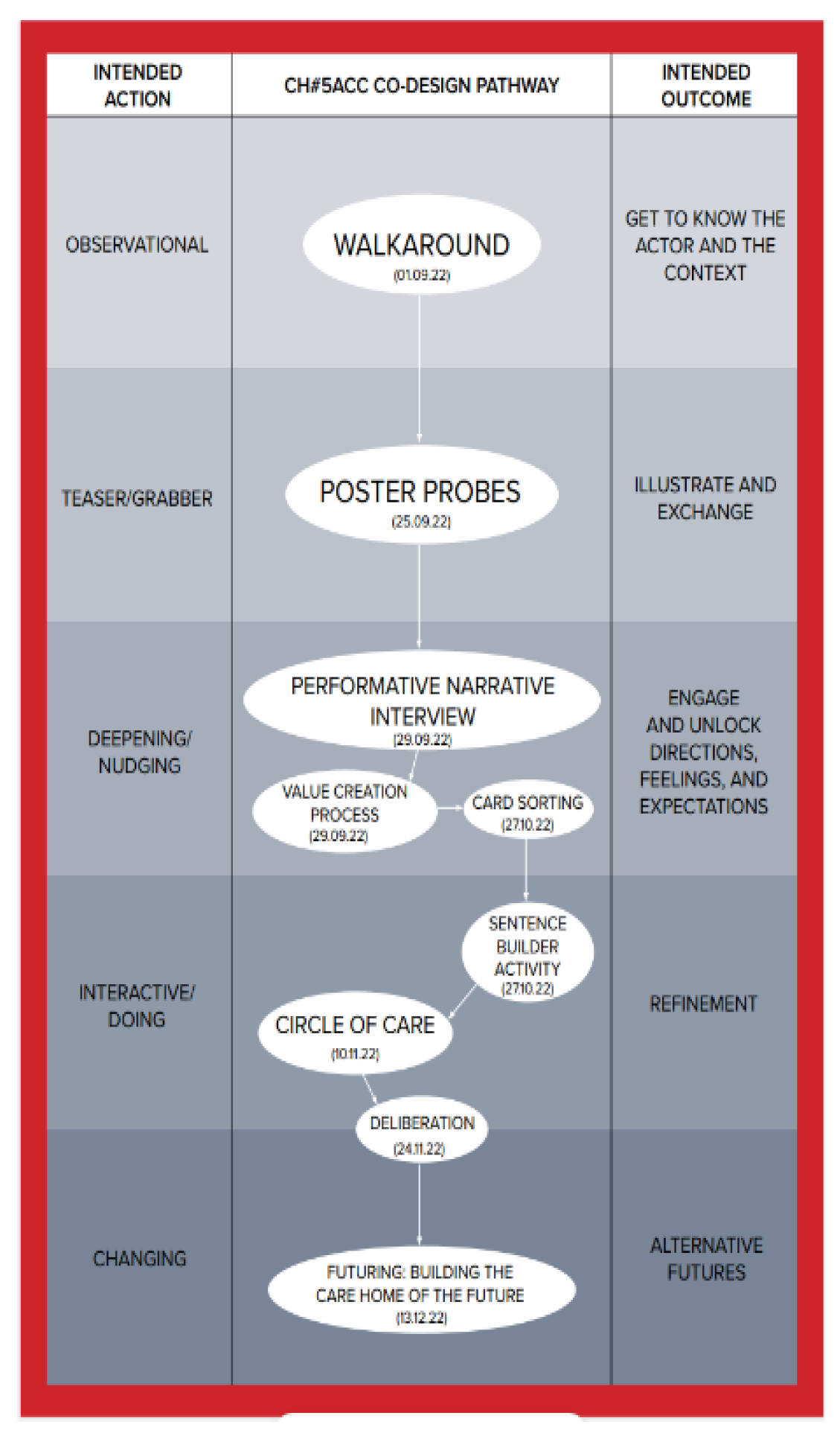

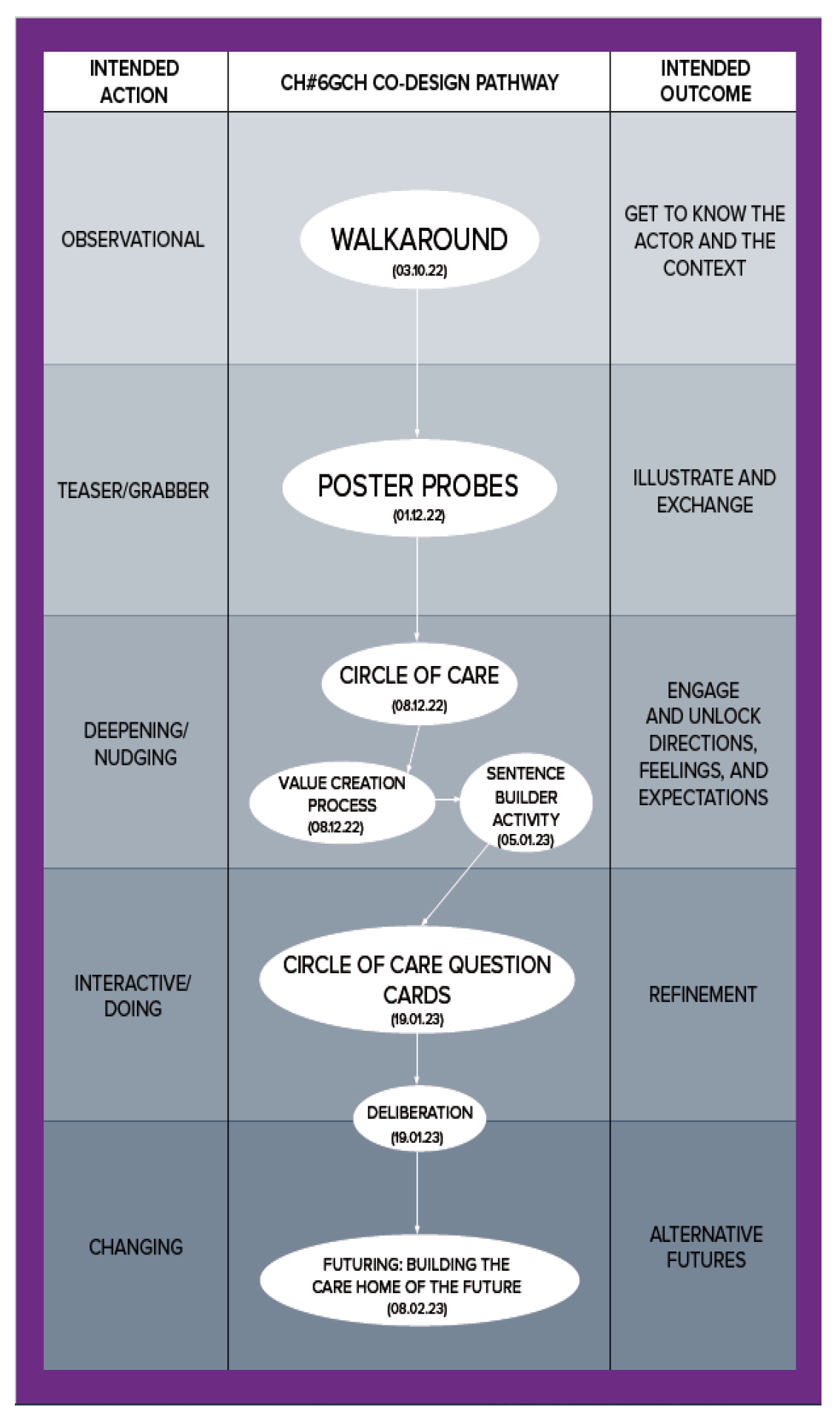

In this paper we shall aim to illustrate how, using co-produced design outcomes from the (anonymised for peer review) project, a research initiative funded as part of the (anonymised for peer review) in the UK, an interdisciplinary, intersectorial programme, which attempts to find ways of improving working conditions for care workers. Co-design was used to develop engagement, aiming to bring to the surface relevant aspects of the care workforce experience and culture and to enable the co-production of alternatives to facilitate the carrying out of their day-to-day activities. Nevertheless, numerous challenges had to be overcome to successfully conduct this research, the most significant of which was the fact that the study took place during the UK Covid-19 lockdowns, which introduced a high degree of uncertainty and distrust. To address these challenges, a methodological tool called the Ripple Framework was developed. This tool provided the flexibility to permanently redesign co-design pathways in response to any unanticipated situations encountered by the research teams. This strategy was instrumental in building and reinforcing trust. Ethnographic data from 44 interviews enabled research teams to approach each care home as a unique case, informing the definition and selection of tailored activities. The co-design process was implemented in five stages for each home, with each stage having a specific action and intended outcome (see

Table 1), ultimately establishing a customized pathway for each care home (see

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7).

The pre-design phase, also known as the ethnographic stage, involved an open-ended and exploratory empirical engagement with day and night-shift workers aged 50 and above. This approach provided a profound understanding of the frontline workers’ experiences. Building on these insights, each session in every care home was tailored according to the findings of the preceding activities (i.e., generative design process). A diverse array of design methods was employed, including walkarounds, probes, performative narrative interviews, experience-based co-design, card sorting, table games, serious play, and crafting postcards and newspaper headlines envisioning the future. Each activity was strategically designed to foster relationships and collaboratively identify strategies to enhance retention and recruitment.

After the initial walkaround phase, where we posed broader questions about the roles and experiences of care workers, we moved on to stage two, delving into more technical and thought-provoking inquiries. We utilized poster probes to present four existing healthcare projects and technologies, prompting questions such as, “How could technologies or initiatives like these support your work?” In the third stage, we employed the Performative Narrative Interview approach, which featured more open-ended questions, including, “What does teamwork mean to you, and how important is it in delivering care?”, “How does a lack of recognition affect care?”, “What does self-care mean to you?”, and “What barriers prevent you from delivering care?” These questions were developed based on insights gathered from follow-up interviews with each care home after the poster probes were collected. By using semi-structured approaches, we aimed to create a sequence that would deepen and establish meaningful relationships with the 31 participants who engaged with us over the ten months of co-design.

2.1. Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected through interviews and co-designed artifacts—such as cards from the card sorting activity, crafted postcards, and mock front pages of future newspapers—alongside verbatim transcriptions of audio recordings from the co-design sessions. To analyse these data, we employed grounded theory methods, including thematic analysis, content analysis, and matrix analysis, which helped to uncover the meanings and shared values expressed by our co-designers. Building on these findings, we conducted a deliberative session (stage four) with each of the six care homes. Through open and honest debate, we explored the meanings, emotions, and expectations conveyed through language, striving for consensus by prioritizing the issues that staff identified as needing change. The Futuring activities in stage five allowed participants to express their expectations and envision scenarios spanning preposterous, possible, plausible, projected, probable, and preferable futures (Voros, 2017). We emphasize that the bespoke design and delivery of these six co-design pathways (figs 2–7) were made possible by utilising the Ripple Framework, which was specifically curated for this purpose and will be presented next.

2.2. The Ripple Framework

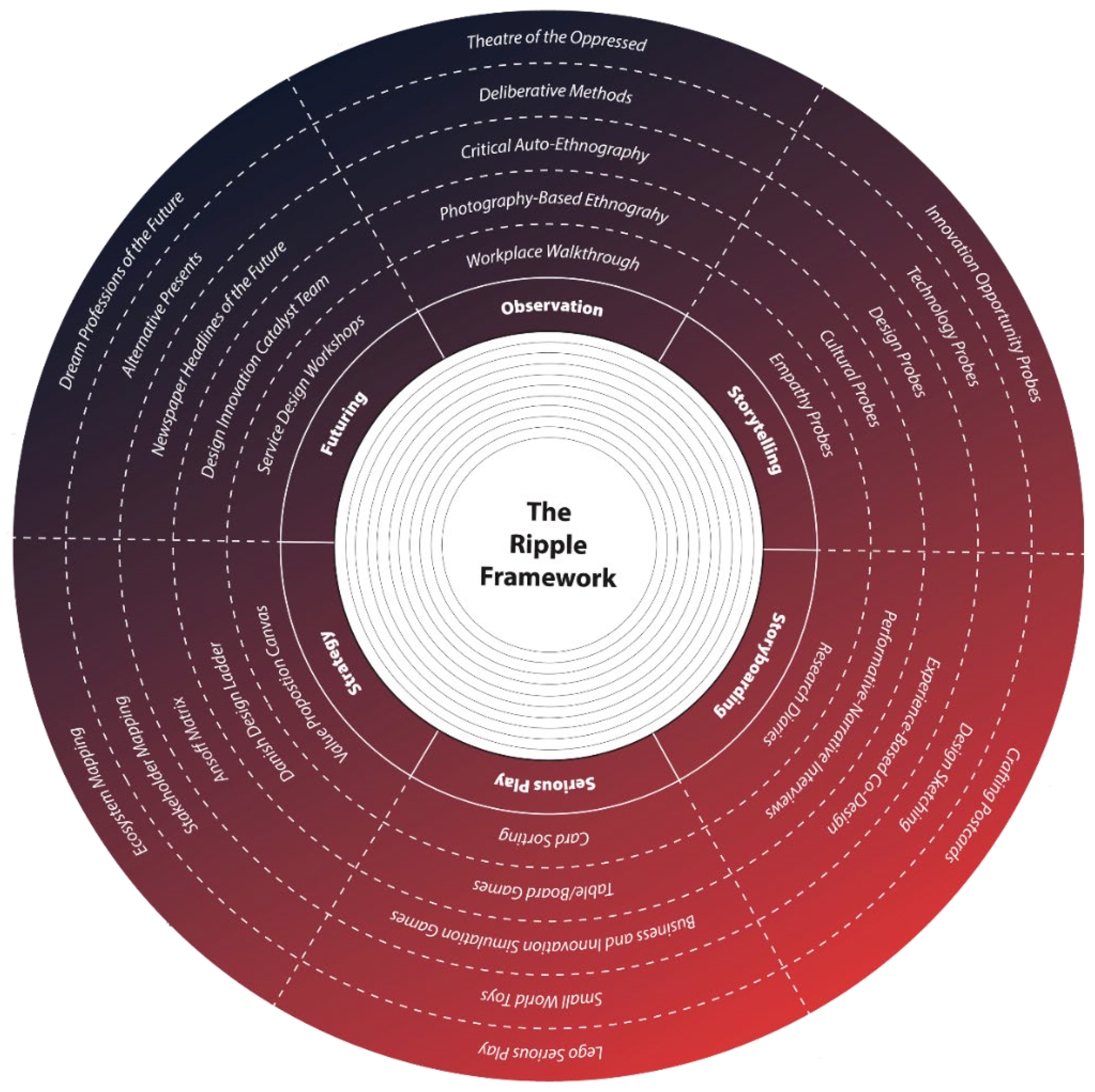

Vines et al. suggest considering “peoples’ current practices, experiences, etc–and how can we make best use of these [to co-produce design responses]” (Vines, Clarke, Wright, McCarthy, & Olivier, 2013, p. 431). Within this frame of reference, we developed the Ripple Framework (RF) (

Figure 5), a methodological framework to help promote a more “designerly” perspective (Stolterman, 2008) to design research while enabling high level of trust to flow. Debrah et al., (2017) building on Sanders & Stappers (2014), emphasise that design practice “[...] in certain contexts is devoid of user inputs”, consequently, when proposing the Ripple Framework as a methodological tool, we aim to promote the radical participatory design by placing the target audience at the centre of the process, conceding them the opportunity to reclaim their agency to think, talk and act in a more relational manner. The framework will enable more flexibility to tackle complexity, and enabling trust to flow between designers and co-designers. This bespoke framework will facilitate to co-design with those actors, seeking to shift the interaction flow from one-way to multi-ways, and placing the target audience (care workers) at the core, playing the role of co-producers of the change. Fundamentally, the RF encourages action due to its playfulness character.

Figure 8.

–The current interactive version of the Ripple Framework. Available at: Ripple Framework.

Figure 8.

–The current interactive version of the Ripple Framework. Available at: Ripple Framework.

3. Background Work

Building on the foundational work of Udoewa (2022a; 2022b) and Udoewa & Gress (2023), this article advocates for a more relational approach to research. This perspective challenges the traditional reliance on empathy as a justification for design decisions, proposing instead an ontological shift that emphasizes “being alongside the other.” By adopting this stance, the approach acknowledges and respects the situated design agency of individuals, rather than assuming their role or position. In this way we see the development of the Ripple Framework not only as a pragmatic tool but as a platform for developing partnerships to animate collective futures (Bennett & Rosner, 2019). By seeking to familiarise the care workforce with co-design methods and frameworks, we intend to generate not one-off solutions to problems (although these may also be valued outcomes according to Knutz and Markussen (2019), but a conceptual space for ongoing creative autonomy and power. This process involves the staff actively redesigning their own work conditions, using commonly available resources as the foundation for developing new mechanisms to enhance health and well-being. Additionally, this approach adopts a relational ontology, moving away from methodological individualism to focus on the emergent relationships between roles and individuals, as well as the interactions between people and their environments.

Applying this to the (anonymised for peer review), we see in Bittencourt and Freire’s approach an example of how to recalibrate the power relations (2022), when carrying out Radical Participatory research. We therefore argue that radical participatory forms of participation (Udoewa (2022a; 2022b) will favour increased levels of creativity in psychosocial care. Therefore, this work aims to contribute to the needs of well-being of the care workforce through a relational approach to co-produce design responses, which goes beyond transactional requirements to gather information; rather, information is understood as something that is creatively generated (Pula, 2020). The reasons for this approach also include the pragmatic need to be flexible in engaging care staff during the height of the Covid pandemic and the lockdowns enforced by UK national governments between 2021–2022. A first-person, or human-centered, perspective is essential to relational design. This approach allows researchers and co-researchers to fully immerse themselves in the lifeworld, making it a critical component of the research process. This can lead to a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the communities’ needs and preferences that can inform design decisions. It also allows researchers to test and refine their designs in real-world contexts, addressing problems and obstacles as they arise. Moreover, by centring the research process on relations or relationships, we argue that it can produce knowledge that is not only theoretically informed but also personally meaningful and actionable. We believe this approach will facilitate the activity of describing, explaining and ultimately generating ideas and actions adequate to the context of action and actors that inhabit those complex lifeworlds.

This work also aligns with Bate who argues in favour of a new approach to capture the “messy, debatable and unquantifiable but essentially human dimensions of life, such as history, beauty, imagination, faith, truth, goodness, justice and freedom” (2011, p. 6). Here we make a point by stressing that design research has better chances of success if done in the “wider context of human interaction with the world” (Kaptelinin & Nardi, 2006). We see this as extending co-design activities considering that we don’t perceive design process as “distinct from ‘being’ or the ‘ongoing flow’ of daily life, and from the dynamic complexity of the lifeworlds of users” (Kettley & Smyth, 2007, p. 1). To illustrate this, this paper builds on the work of Rodgers et al. (2020) to underline how we can make tangible the value bounded in relational design.

3.1. Everyday Life and Complexity

Social life is complex, it’s an undeniable truth, whether one like it or not. However, complexity does not need to be understood as “evil” (Stolterman, 2008). For instance, both, in physics and information theory, this phenomenon is referred to as entropy and can be tracked back to Shannon’s information entropy theory (Shannon, 1948) which states that “the entropy of the output can be calculated” (1948, p. 15). Building on Shannon’s theory, Menhorn and Slomka (2011) contend that entropy and complexity, as measures of disorder, permeate every aspect of our daily lives. This perspective aligns with the central argument of this paper: that both entropy and complexity are not merely abstract concepts, but dynamic forces that drive human action. Therefore, departing from specific fields such as information systems (Zadeh, 1965) and design (Debrah, De la Harpe, & M’Rithaa, 2017) we subscribe acting in a more systemic way (Menhorn & Slomka, 2011), to try and give a degree of coherence to complexity and entropic phenomena (Newman, 2002; Sanders & Stappers, 2014).

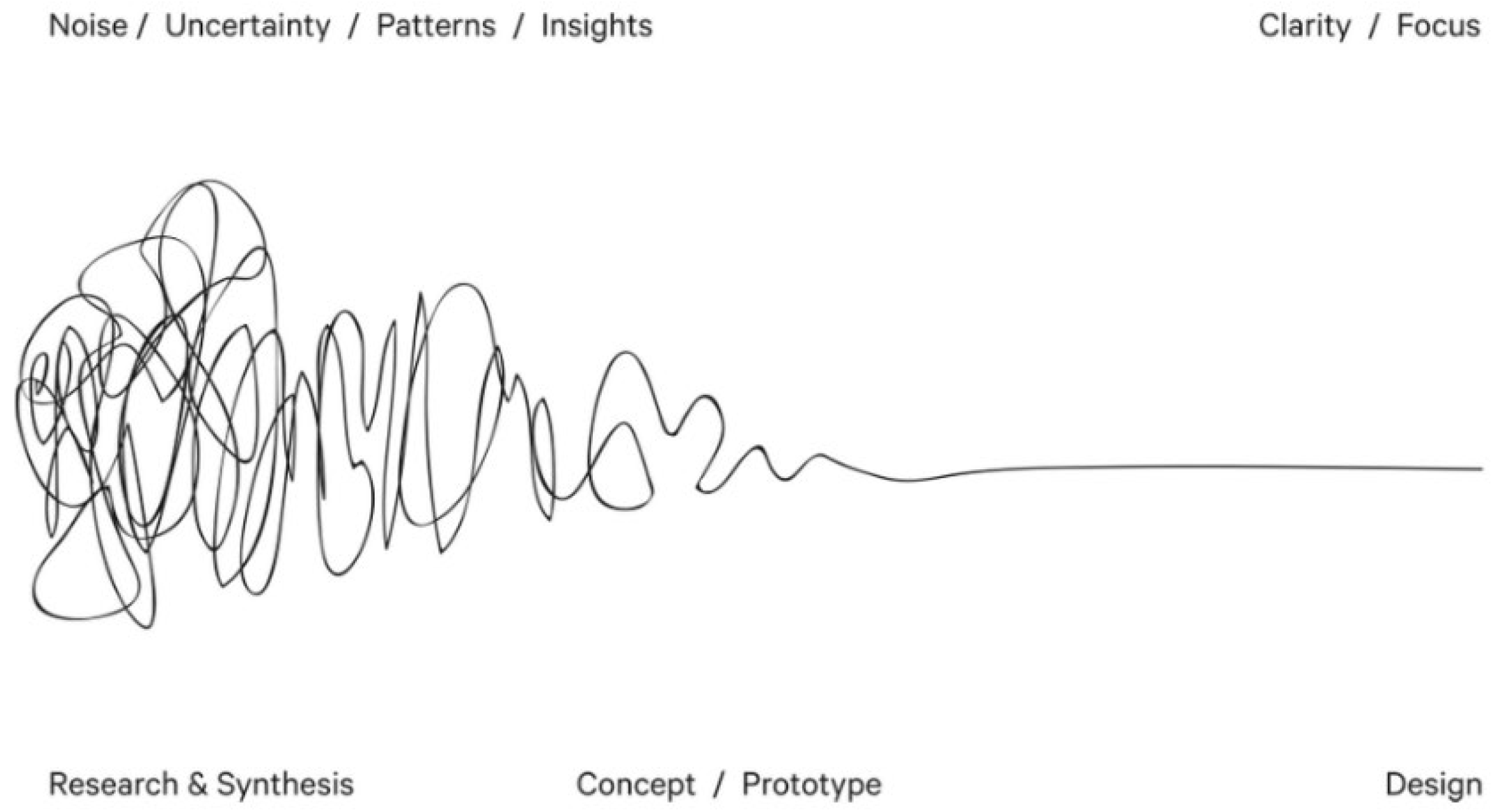

Traditional methods for addressing these challenges have often relied on a positivistic perspective, employing mechanistic and linear reductionist techniques that are more appropriate for physical systems rather than complex adaptive human systems. As a result, they have not succeeded in achieving the required system transformation (Carroll, Collins, McKenzie, Stokes, & Darley, 2023, p. 1). For instance, reductionism seeks to simplify complexity by reducing it to its constituent parts. However, while this approach can yield insightful results, it often overlooks critical facets of reality that cannot be easily reduced to simpler elements. These overlooked aspects often entail the convoluted dynamics (noise and uncertainty as per

Figure 1) that configure a given lifeworld or the lived world of social reality. However, our lifeworlds are constructed through different discourses (patterns as per

Figure 1), performed in different languages, embedded in different cultural matrices, and enacted through different social practices and bodies. Each of these spheres carries its unique complexity that cannot be easily reduced (insights as per

Figure 1) to simpler elements without losing critical aspects of their reality.

In other words, the simple (clarity and focus as per

Figure 1) is often not so simple, and the complex cannot be easily discarded as merely complicated. Moreover, each of these spheres of everyday discourses often generate different forms of dissensus or disagreement rather than consensus. This dissensus is not merely a matter of different views or perspectives, rather it is a manifestation of the inherent tensions, conflicts, contradictions, and contestations within and between different spheres of life. Therefore, while reductionism and simplicity may offer appealing avenues for investigation and understanding, they may also lead to misconceptions, misinterpretations, or oversimplifications. It becomes crucial then to take this into consideration in the designing thinking process namely when moving from research and synthesis to concept and prototyping and from there to design response (see

Figure 1). This is an important matter to be addressed to assist the design community navigate the “messy and wicked [character of] everyday context” (Stolterman, 2008).

3.1.1. Addressing the Well-Being of the Care Workforce

Design thinking, specifically on health care, put the emphasis on the relationship between care providers and patients, particularly focusing on barriers and opportunities for deployment of technologies for the elderly recipients of care (Xiao, 2012). This highlights the need to better model (Guo, Wang, Zhao, & Sun, 2022) and integrate technological resources into the day-to-day care practice (Yuan, Coghlan, Lederman, & Waycott, 2022) and to provide social and emotional enrichment (Thach, Lederman, & Waycott, 2023) to both care workers and residents. In harmony with this body of literature, and those arguing in favour of holistic approaches (Dankl, 2013), we stress the need to refocus designed alternatives based on a balanced trade-off between care providers (in this care workers) and beneficiaries (residents).

Wearable’s development has seen some research in healthcare research, (Sarah Kettley, Bates, & Kettley, 2015) addressing psychosocial needs of technology wearers as bodies in relation with the materials and forms of technology and with viewers (Møller, 2018). Service design, in its emphasis on stakeholder maps and power relations between roles as highlighted a sequence of relations in many ways relational (Drummond, 2019; Neuhoff, Johansen, & Simeone, 2022; van der Bijl-Brouwer, 2022). Therefore. when thinking about adequate responses the need to consider different forms of values (social, cultural, and economic) and day-to-day priorities of residential care staff as users emerge.

Consequently, “[u]nderstanding what capabilities matter and how to cultivate them is especially important in care settings because of the complex, unstructured, dynamic and unpredictable nature of these locations” (O’Donovan et al., 2023, p. 2). We find complementary research on the relational in other disciplines, notably well developed in psychotherapy (Knox, Murphy, & Wiggins, 2012; Mearns & Cooper, 2017), and in ontological and new material approaches in craft theory and the materially-led design of technology (Pineyro Irazabal, 2020; Wisnoski, 2019); (Walker, Kettley, Downes, & Dias, 2015). Signals of a similar ontological shift to the relational (in the west) can also be seen in the public health literature (Hanlon, Carlisle, Hannah, Reilly, & Lyon, 2011; O’connor et al., 2016).

4. Results

By adopting a relational and dialogical approach to co-producing change, the (anonymized for peer review) introduced a new design environment where the health, dignity, and well-being of staff are inextricably linked to the systemic issues that care workers aimed to address during the co-design session created to support this goal. This begins with recognising the true value of care work, improving the work environment, elevating the status of caregivers, offering personal development opportunities, and ensuring that caregivers themselves are well cared for. Key issues that need to be addressed include providing basic physical aids for routine tasks, enhancing mental health support, improving communication tools, and, most importantly, implementing measures to elevate worker recognition and status in society. By employing the vignettes technique, we will now explore three cases that will lay the foundation for understanding how social, cultural, and economic value can be generated through design research.

4.1. Vignets

To revisit some of our stories, we employed the technique of textual vignettes. Bahmani (2020, p. 2135) argues that vignettes enable “the researcher to collect data that is not accessible through other sources,” which supported our decision to use this method. Hazel (1995, not paged) further reinforces this approach, emphasizing that vignettes allow researchers to present “actual cases of people and their behaviours, enabling participants to express their statements or viewpoints.”This approach aligns with the relational framework we aim to promote and with a crucial aspect of the [anonymized for peer review]: empowering care workers (now co-designers) to reclaim their agency in both dialogue and action. This, in turn, enriches the research with meaningful, realistic change and highlights “important points from stories about those actors’ perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes” (Hughes & illness, 1998, p. 381), which would not be easy to get to if not from the perspective of those actors.

4.1.1. Vignets 1: Enabling Learning and Personal Development (Social Value)

“we can all learn from each other [and] create a culture where everyone is heard” (Player#1@CH#1BDR?)

Located north of Edinburgh (anonymised for peer review), the care home features a beautifully designed and thoughtfully arranged layout, creating a calming, welcoming, and secure environment. The care home is committed to fostering inclusivity and diversity, valuing the unique traits and personalities of each staff member. This emphasis on embracing diverse backgrounds has earned the care home numerous awards over the years. The management takes great pride in the high quality of care and services provided by its skilled and passionate team. Potential residents and their families can have peace of mind knowing that their loved ones will be cared for by dedicated professionals. The institution’s commitment to creating a warm, welcoming environment, along with its outstanding track record and innovative approach to continuous professional development and staff well-being programs, sets it apart as a leader in the field.

In November 2022, a new training unit was inaugurated to enhance strategic resources and ensure that staff are fully trained in all aspects of care. The care home prioritises staff training through significant investment in learning and development, supported by a structured plan for staff progression. This commitment has resulted in high staff retention rates and an overall satisfied workforce. Their distinctive approach to individualized, holistic care planning—considering both residents’ and care workers’ needs and preferences—is one of the many reasons this care home stands out. This provides strong evidence that a significant part of the care home business model is built on fostering a proactive and responsible approach, encouraging staff to adopt a collaborative culture. In this environment, they embrace their responsibilities with autonomy and flexibility, learning “from each other [and therefore] create a culture where everyone is heard” (Player#1@CH#1BDR).

The staff also mentioned that they receive regular and appropriate training, which makes them feel confident and well-equipped to handle any situation. They emphasized the importance of communication, noting that they “talk to each other to stay on the same page” (Player#2@CH#1BDR?). This approach is crucial because it allows everyone to “learn from each other, shift their mindsets, and show respect for others” (Player#2@CH#1BDR?). Additionally, the staffing levels appear adequate, ensuring that no one feels overwhelmed or overworked. This sense of fulfilment and the absence of excessive pressure foster a happy, patient, and compassionate team of staff who are deeply committed to their vital roles. The care home administration emphasizes the importance of communication, encouraging the proactive sharing of opinions and suggestions. Effective dialogue allows “others a chance to view or give an opinion to change” (Player#3@CH#1BDR?), as noted by one team member.

This participatory process contributes to maintaining a high standard of care and a positive work experience, which is largely attributed to the open “communication with experienced staff” (Player#3@CH#1BDR?). The manager hopes that the younger generation, guided by the experience and lessons of more senior employees, will uphold and possibly even elevate the high standards of care. This approach not only provides security and dignity but also positively impacts staff morale, well-being, and cohesion. Furthermore, those receiving care feel well looked after, valued, and respected. In this way, care transcends individual responsibility; it should be recognized as a shared societal obligation that contributes to social growth, cohesion, and overall social value

4.1.2. Vignets 2: Implementing a Culture of Openness and Support (Cultural Value)

“It is important to look after your own health and well-being so that positivity can be passed on to others around you; you need to look after yourself to give good care to others.” (Player#5@CH#4CBS)

The care home is located in a village within the historic county (anonymised for the peer review process). It is known for fostering a positive and supportive culture among its staff. The management team has been proactive in implementing meaningful changes to promote a culture of well-being within the care home. Notably, they introduced a Time Out/Bereavement room and organised yoga and meditation sessions, among other initiatives, as part of their efforts to innovate and enhance the well-being of both staff and residents. However, these efforts to promote change did not yield the expected results, highlighting the need for further reflection and strategic planning. For instance, one participant emphasized the importance of addressing basic needs before attempting to satisfy higher-level needs such as self-esteem. They noted, “This is important because if I don’t feel right physically, I won’t be able to perform at my best” (Player#5@CH#4CBS).

These elements were crucial pieces of the larger puzzle that enabled us to collaboratively co-produce a design pathway aimed at fostering a more supportive culture in this care home. One key activity we implemented was the Circle of Care, which encourages staff to adopt a holistic approach to care. The goal is to help them recognize the importance of self-care, emphasizing that “it’s essential to look after your own health and well-being so that you can pass on positivity to those around you; you need to care for yourself in order to provide quality care to others” (Player#5@CH#4CBS). “In the end, five co-design sessions were conducted, encompassing the Performative Narrative Interview (PNI), Value Creation Process (VCP), Circle of Care (CoC), Deliberation, and Futuring through Newspaper Headlines of the Future (NHF). Following these sessions, and with management’s support, it was agreed to co-produce an action plan that highlights the creation of a new job role: the Staff Activity Planner.”

The action plan aimed to promote a change in the care home’s ambiance. The team utilized air-purifying scent diffusers and Bluetooth-enabled speakers to create a calm, soothing, and uplifting environment, playing seasonal music via popular streaming apps. Additionally, the care home was redecorated with colours and scents reflecting the four seasons and festivities, enhancing reminiscence for residents and boosting morale for care workers. The most ambitious aspect of this plan was the co-production and implementation of an internal Relational Communication Training course. This course aimed to foster a more holistic, efficient, and effective communication style within the care home, enhancing both productivity and job satisfaction. The Relational Communication training focused on effective listening, constructive feedback, assertiveness, conflict resolution, and negotiation skills. The course materials were designed for easy transfer to an online learning management system, ensuring continuous access for staff and reinforcing their learning process.

4.1.3. Vignets 3: Scaling-Up New Roles through Co-Design (Economic Value)

“I am now a co-designer” (Player#1@CH#5ACC)

Our third case reports on a care home situated to the (anonymised for peer review). This home provides care for adults with dementia and dementia-related illnesses. It also supports adults with learning disabilities and behaviours which can present challenging situations between staff and residents. We start the co-design process in the care home by highlighting the excellent work produced with the poster probes—the initial design material introduced in the care home context. We emphasized that the two activities planned for the second session were based on this poster engagement. The first author served as the primary facilitator, while the second author acted as a secondary facilitator, observing and contributing when necessary. The second session included the Performative Narrative Interview (PNI) and the Value Creation Process (VPC). Our strategy involved guiding the co-designers through the activities while explaining the principles of co-design. This approach proved successful, as evidenced by one participant exclaiming, “I’m a co-designer now!” (Player#1@CH#5ACC). We conducted four additional sessions featuring Card Sorting (CS), a Sentence Builder Activity (SBA), the Circle of Care (CoC), Deliberation (DLB), and Building the Care Home of the Future (BCHoF).

One of the key challenges identified in this care home is a sort of intergenerational tension. A 52-year-old male worker emphasized that “the older generation is the backbone” of the facility. This issue is particularly relevant as it has also surfaced in other research sites. However, it appears contradictory, given that younger care workers often assist the older generation in improving their digital skills. Some participants admitted to being technophobic, lacking even basic tools like email addresses. For example, Player #3 mentioned that he tries to complete the online training on his own at home but often relies on his son or wife, while at the care home he relies on other staff, normally younger workers, to assist him with the technology due to “occasional glitches” (Player #3 @ CH#5ACC). He emphasised that in his role he could not progress to be specialist without the training he had done over time, mentioning that “it is regular, comprising mainly an e-learning approach” (Player#3@CH#5ACC), which he also does online at home. He got the Scottish Vocational Qualifications (SVQs) which are work-based qualifications to guarantee that we can do his job well and to the national standards for their sector.

This insight highlights the potential to minimize intergenerational tension by fostering the exchange of skills and experiences between generations. Leaders in care settings can leverage this by adopting strategies that develop critical digital capabilities while bridging generational gaps. For instance, they can promote experiential learning, where staff members gain knowledge through hands-on experience and reflection. Additionally, leaders can foster a culture of openness and continuous improvement, encouraging staff to share ideas, experiences, and mistakes without fear of retribution. Quality care delivery hinges on the staff’s ability to collaborate, adapt, innovate, and learn in real time.

The outcomes showed that staff felt more invested in their responsibilities after participating in co-producing the solutions they would implement. For example, the co-design activities in this care home revealed that, beyond merely providing care workers with tools and training, involving them in collaborative problem-solving and decision-making (i.e., co-producing change) builds their confidence, deepens their understanding of the context, and strengthens their commitment to their roles. As a result, they better comprehend their daily tasks and can handle crises with greater flexibility. This approach was particularly effective in achieving a more balanced workload distribution. For instance, optimizing processes saved time, which could then be used to deliver higher-quality care to residents and give care workers more time to rest. Furthermore, the co-design activities encouraged staff to think beyond their specific roles, demonstrating that co-design had a significant impact on the care home’s business strategy, reshaping its economic value.

5. Discussion

Drawing on our empirical material and using the Design Research Value Model proposed by Rodgers et al. (2020) we will illustrate how co-production of change can achieved through co-design, therefore addressing unmet complex needs trigged by ‘wicked problem’ which tend not to be best addressed with ‘off-the-shelf’ solutions. We have illustrated that these needs have better chances to be resolved if we approach them from a context specific action and helping actors, in this case the care workers, regain “their agency to speak out and act within their social setting” (Soares, Kettley, & Speed, 2023). The RF enabled co-designers’ novel opportunities to address what Rogers stressed to be the need to “identify and articulate the significant roles that design research plays in generating social, cultural, economic and environmental value.” (Rodgers et al., 2020, p. 510).

5.1. Co-Designing Social Value for Care

Social value co-creation requires significant investments in time, energy, and resources from all involved parties. Those participating must be open to sharing ideas, debating their merit, and ultimately negotiating a shared understanding and direction. This is no easy task, as it involves overcoming obstacles such as pride, ego, and control. However, the benefits of social value co-production can far outweigh these challenges. This collaborative design processes encouraged participants to think innovatively and consider fresh perspectives and ideas, and helped foster a sense of community and shared identity as participants work towards a common goal. As participants engage in these processes, they were often challenged to develop and refine their skills and abilities. They learned to communicate effectively, negotiate, and compromise, all of which are valuable social skills, contributing to individual personal growth and development, while challenging, enabling social value co-production through “face-to-face participation, real-time interaction, and alignment towards a common goal” (Rodgers et al., 2020, p. 495)

5.2. Co-Designing Cultural Value for Care

Within the scope of this article, we refer to cultural value as “the tacit knowledge embodied in social processes” (Arvidsson & Class, 2009, p. 7) which can take a variety of forms, including localised norms, languages and practices, all contributing to a sense of purpose and belonging. As such, a shared organisational culture is fundamental to help deliver high standards of care because it contributes to training care workers in a particular context and guiding them in their interactions with others and serving as a source of inspiration and creativity, as well as allowing them to foster critical thinking. Evidence produced by this research helped us demonstrate that as those individuals who interacted with their colleagues through co-design activities learned to interpret their organisational context and gain deeper understanding of concealed nuances and complexities. This is turn helped shape their moral compasses and discern what needed to be done at every stage of a given process. This can be aligned with Rodgers’ perspective that “cultural engagement contributes to a greater shaping of reflective individuals” (Rodgers et al., 2020, p. 496) and constitutes another important output of this design research.

5.3. Co-Designing Economic Value for Care

According to Rodgers et al., new business opportunities or new business models can be applied to help “expanding markets through personal development and user understanding, as well as cost reduction” (2020, p. 496). The vignettes we used to illustrate some of our results show that design research can beyond doubt generate economic value. Design-centric organisations adopted for empathetic thinking, which helps them understand their stakeholders’ experiences and incorporate the insights into their product or service development process (human-centred approach). Evidence produced by this research shows that through co-design activities it’s possible to pave the way to improved retention and recruitment, while minimizing effects of the care crisis.

6. Future Work

In the UK, the care sector is primarily made up of independent (and often small) businesses of varying size, organisational structure, culture, and context. All are rightly subject to strict legislation relating to care and safeguarding, and the majority are dependent on incomes per resident that are set by national and local government. This limits business flexibility and complicates what is already a resource-poor environment (in finances, time, and workforce). However, as we look toward the sector’s future, it is important also to consider that each care home is itself a ‘complex system’ and has its own contextually derived concerns. To “perform research into complex systems in which power law distributions are in operation there is a need to interpret the processes of dynamicity” (Carroll et al., 2023, p. 9). This, we suggest, requires us to conduct more relational studies, in which those impacted by such forces should be placed at the core of the research.

7. Conclusion

We contribute an original framework which enables the co-production of social innovation and social change, namely for the care sector and, potentially, other complex settings. The Ripple Framework has assisted individuals (care workers) and industry (care homes) with opportunity and flexibility to talk and act, while supporting design research to expand its scope of action when facilitating tools to reframe relevant assumptions, such as the stigma that affects the care sector. This is an important step in driving innovation and growth in the healthcare industry. Reach can be significantly improved through ‘radical participatory design’, which allows for better understanding of actors in context (that is, a relational approach). In this article, we have illustrated how, when assisted to reinterpret their own tasks, these actors can significantly contribute to co-produce bespoke solutions to problems they have identified. We conclude by stressing six fundamental steeps in any co-design process to co-produce sector changes:

Providing care workers with the necessary tools and resources: namely software and technologies to educational resources and training for skill enhancement.

Encouraging collaboration: teamwork and cooperation between care workers can lead to the exchange of ideas and perspectives, fostering creative solutions.

Encouraging communication: open and constant communication amongst team members can ensure everyone is on the same page and working towards a common goal.

Supporting innovation: providing a supportive environment that encourages risk-taking and out-of-the-box thinking is essential to fuel innovation and change.

Ensuring inclusivity: bringing in diverse perspectives can lead to more well-rounded and unique solutions.

Delegate responsibilities: each member should be given specific roles to highlight their strengths and ensure equal involvement in co-producing change.

References

- Arvidsson, A. J. C., & Class. (2009). The ethical economy: Towards a post-capitalist theory of value. 33(1), 13-29.

- Bahmani, N. D., Midwifery, M. J. J. o., & Health, R. (2020). A Narrative on Using Vignettes: Its Advantages and Drawbacks. 8.

- Bate, J. (2011). The public value of the humanities: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Bennett, C. L., & Rosner, D. K. (2019). The promise of empathy: Design, disability, and knowing the” other”. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 2019 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems.

- Bittencourt, G., & Freire, K. (2022). Spirituality based codesign: Searching ways to operate a sentipensante participatory design. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the Participatory Design Conference 2022-Volume 2.

- Carroll, Á., Collins, C., McKenzie, J., Stokes, D., & Darley, A. J. B. o. (2023). Application of complexity theory in health and social care research: a scoping review. 13(3), e069180. [CrossRef]

- Cross, N. J. D. s. (1982). Designerly ways of knowing. 3(4), 221-227.

- Dankl, K. J. T. D. J. (2013). Style, strategy and temporality: how to write an inclusive design brief?, 16(2), 159-174.

- Debrah, R. D. , De la Harpe, R., & M’Rithaa, M. K. J. T. D. J. (2017). Design probes and toolkits for healthcare: Identifying information needs in African communities through service design. 20(sup1), S2120-S2134.

- Dow, A. , Comber, R., & Vines, J. J. i. (2019). Communities to the left of me, bureaucrats to the right… here I am, stuck in the middle. 26(5), 26-33.

- Drummond, S. (2019). Service Design: creating a relational state Retrieved from https://sarah-drummond.com/2019/06/service-design-creating-a-relational-state/.

- Foong, P. S., Zhao, S., Tan, F., & Williams, J. J. (2018). Harvesting caregiving knowledge: Design considerations for integrating volunteer input in dementia care. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

- Goodman, N. (1978). Ways of worldmaking (Vol. 51): Hackett Publishing.

- Guo, J., Wang, B., Zhao, J., & Sun, Y. (2022). CareMap: Human-Space-Service Based Healthcare Modeling and Quantifying for the Elderly Aging in Place. Paper presented at the 2022 IEEE 25th International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design (CSCWD).

- Hanlon, P. , Carlisle, S., Hannah, M., Reilly, D., & Lyon, A. J. P. h. (2011). Making the case for a ‘fifth wave’in public health. 125(1), 30-36.

- Hazel, N. J. S. r. u. (1995). Elicitation techniques with young people. 12(4), 1-8.

- Hughes, R. J. S. o. h., & illness. (1998). Considering the vignette technique and its application to a study of drug injecting and HIV risk and safer behaviour. 20(3), 381-400. [CrossRef]

- Kaptelinin, V. , & Nardi, B. A. (2006). Acting with technology: Activity theory and interaction design: MIT press.

- Kettley, S., Bates, M., & Kettley, R. (2015). Reflections on the heuristic experiences of a multidisciplinary team trying to bring the PCA to participatory design (with emphasis on the IPR method). Paper presented at the Adjunct Proceedings of the 2015 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing and Proceedings of the 2015 ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers.

- Kettley, S., & Smyth, M. (2007). Plotting Affect and Premises for Use in Aesthetic Interaction Design: towards evaluation for the everyday. Paper presented at the People and Computers XX—Engage: Proceedings of HCI 2006.

- Knox, R. , Murphy, D., & Wiggins, S. (2012). Relational depth: New perspectives and developments: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Knutz, E., & Markussen, T. (2019). The ripple effects of social deisgn: a model to support new cultures of evaluation in design research. Paper presented at the Design research for change symposium.

- Lefebvre, H. (2014). Critique of everyday life: the one-volume edition: Verso Books.

- Mearns, D. , & Cooper, M. (2017). Working at relational depth in counselling and psychotherapy: Sage.

- Menhorn, B., & Slomka, F. (2011). Design entropy concept: a measurement for complexity. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the seventh IEEE/ACM/IFIP international conference on Hardware/software codesign and system synthesis.

- Møller, T. (2018). Presenting The Accessory Approach: A Start-up’s Journey Towards Designing An Engaging Fall Detection Device. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

- Neuhoff, R. , Johansen, N. D., & Simeone, L. (2022). Story-centered co-creative methods: A means for relational service design and healthcare innovation. In Service Design Practices for Healthcare Innovation: Paradigms, Principles, Prospects (pp. 511-528): Springer.

- Newman, D. (2002). The design squiggle. In.

- O’Donovan, C., Caleb-Solly, P., Kumar, P., Russell, S., Sumpter, L., & Williams, R. (2023). Empowering future care workforces: scoping human capabilities to leverage assistive robotics. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the first international symposium on trustworthy autonomous systems (TAS’23).

- O’connor, S. , Hanlon, P., O’donnell, C. A., Garcia, S., Glanville, J., Mair, F. S. J. B. m. i., & making, d. (2016). Understanding factors affecting patient and public engagement and recruitment to digital health interventions: a systematic review of qualitative studies. 16, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Pineyro Irazabal, A. (2020). Animating matter: A material-led exploration into the kinetic potential of nylon monofilament. Royal College of Art.

- Pula, P. (2020). Notes Towards a Definition of Generative Journalism. Axiomnews 11.11.2020. Retrieved from https://axiomnews.com/notes-towards-definition-generative-journalism.

- Rodgers, P. A., Mazzarella, F., & Conerney, L. J. T. D. J. (2020). Interrogating the value of design research for change. 23(4), 491-514.

- Sanders, E. B.-N. , & Stappers, P. J. J. C. (2014). Probes, toolkits and prototypes: three approaches to making in codesigning. 10(1), 5-14. [CrossRef]

- Scharmer, C. O. (2009). Theory U: Learning from the future as it emerges: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Shannon, C. E. J. T. B. s. t. j. (1948). A mathematical theory of communication. 27(3), 379-423.

- Soares, L. , Kettley, S., & Speed, C. (2023). The Ripple Framework: a co-design platform (a thousand tiny methodologies). International Association of Sociteis of Design Research Congress.

- Stolterman, E. J. I. J. o. D. (2008). The nature of design practice and implications for interaction design research. 2(1).

- Thach, K. S., Lederman, R., & Waycott, J. (2023). Key Considerations for The Design of Technology for Enrichment in Residential Aged Care: An Ethnographic Study. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

- Udoewa, V., & Gress, S. J. J. o. A.-B. S. C. (2023). Relational Design. 3(1), 101-128.

- Udoewa, V. J. D. S. (2022). An introduction to radical participatory design: decolonising participatory design processes. 8, e31.

- Udoewa, V. J. J. o. A.-B. S. C. (2022). Radical participatory design: Awareness of participation. 2(2), 59-84.

- van der Bijl-Brouwer, M. J. I. J. o. D. (2022). Service designing for human relationships to positively enable social systemic change. 16(1), 23.

- Vines, J., Clarke, R., Wright, P., McCarthy, J., & Olivier, P. (2013). Configuring participation: on how we involve people in design. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

- Voros, J. J. T. V. (2017). The Futures Cone, use and history. 24.

- Walker, S., Kettley, S., Downes, T., & Dias, T. (2015). Facilitating participatory practice for smart textiles. Paper presented at the Adjunct Proceedings of the 2015 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing and Proceedings of the 2015 ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers.

- Wisnoski, B. J. T. J. o. M. C. (2019). An aesthetics of everything else: Craft and flat ontologies. 12(3), 205-217.

- Xiao, N. (2012). Essays on the impact of health information technology on health care providers and patients. In: State University of New York at Buffalo.

- Yuan, S. , Coghlan, S., Lederman, R., & Waycott, J. J. P. o. t. A. o. H.-C. I. (2022). Social Robots in Aged Care: Care Staff Experiences and Perspectives on Robot Benefits and Challenges. 6(CSCW2), 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L. A. (1965). Fuzzy sets. 8(3), 338-353.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).