1. Introduction

Nowadays, the problem of wastewater, which entails both environmental and economic consequences, is of significant relevance [

1,

2]. Despite the variety of water purification technologies currently available [

3,

4] there is a growing need to develop new or improved methods as the amount of harmful emissions from industrial, commercial or agricultural activities continues to increase [

5]. Thus, there is a large number of works demonstrating the ability of some reactive oxygen species (ROS) to degrade organic compounds, antibiotics, herbicides and other pollutants in water [

6]. Methods that apply this property of ROS are described in the literature as advanced oxidation processes (AOP) [

7]. Significant progress in the purification of wastewater can be achieved by improving existing methods of generating reactive oxygen species in water through chemical reactions resulting from the decomposition of the water molecule in the AOP process.

AOP methods involve the formation of hydroxyl radical OH˙, superoxide anion radical O

2-˙, singlet oxygen 'O

2, hydrogen peroxide H

2O

2 and other forms of oxygen [

8]. Ozonation, Fenton reaction, electrochemical methods, ultraviolet irradiation, hydrodynamic cavitation and plasma treatment are commonly identified among the existing AOP methods [

9]. Ozonators convert O

2 oxygen molecules from the air into O

3 ozone molecules, which readily dissolve in water to form aqueous ozone. Ozone has several pathways of decomposition in water, including direct reaction with organic and inorganic compounds, and self-decomposition into oxygen and hydroxyl radicals [

10]. Fenton and Fenton-like processes can also be effective in the decomposition of organic pollutants [

11,

12]. These processes involve the generation of hydroxyl radicals (-OH) by the reaction between hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) and a catalyst, usually divalent iron (Fe

2+), although other transition metals can also be used in Fenton-like processes [

13]. UV treatment can also induce oxidation reactions by promoting the formation of ROS, such as hydroxyl radicals (-OH), from water molecules through photolysis [

14,

15,

16]. However, the above described processes have a number of disadvantages from technological, economic and environmental points of view, among which we can highlight: the need to use chemical reagents (in the Fenton reaction), high energy costs (ozonation and UV treatment) and high cost of equipment (UV treatment) [

17,

18].

A promising method of ROS generation involves the use of plasma which is an ionised gas consisting of electrons, ions, free radicals and excited molecules [

19]. Low temperature plasma can be generated by various methods such as electric discharge, microwave discharge or radio frequency discharge [

20]. Advanced plasma-based oxidation processes represent an innovative approach to water treatment and purification. Plasma is formed by transferring electrical energy to the gas inside the reaction chamber or discharge reactor. Electrical energy ionises the gas molecules, creating a high-energy and reactive plasma. Various chemically active substances are formed during plasma combustion, including ions, electrons, free radicals (such as hydroxyl radicals -OH and oxygen radicals -O), excited atoms and molecules, and UV photons. Plasma-based AOPs provide the flexibility to control various purification parameters such as discharge power, treatment time and water flow rate, allowing the process to be optimised based on specific water quality requirements and contaminant characteristics, while reducing energy consumption.

The effectiveness of water treatment can be enhanced when a combination of some of the above methods are applied to water at the same time. Thus, directly applying electric discharges to a continuous flow of water to maintain a stable plasma discharge is challenging [

21] due to the high breakdown voltage in liquids (>10 MV/cm). This means that, in such cases, enormous electrical power must be allocated to maintain high-frequency and high-voltage voltage pulses for a stable plasma effect on the water. This approach is extremely energy inefficient and places significant limitations on the volume in which plasma can be generated. To solve this problem, scientists have used the creation of an auxiliary gaseous phase in water in the volume of the liquid or on its surface, which leads to a decrease in the breakdown voltage of the medium to values in the range of 1 - 10 kV/cm. Various scientific groups have proposed such methods such as: generation of plasma discharge at the liquid-gas boundary [

22,

23,

24], artificial introduction of various gases into the liquid [

25], etc. Hydrodynamic cavitation has shown to be the most effective of all existing methods of creating a gaseous medium in the water flow for plasma ignition [

26]. The work of Arijana Filipi's research group, which managed to ignite plasma in water under supercavitation conditions and demonstrate the effectiveness of such a method in destroying viruses, is of particular interest [

27].

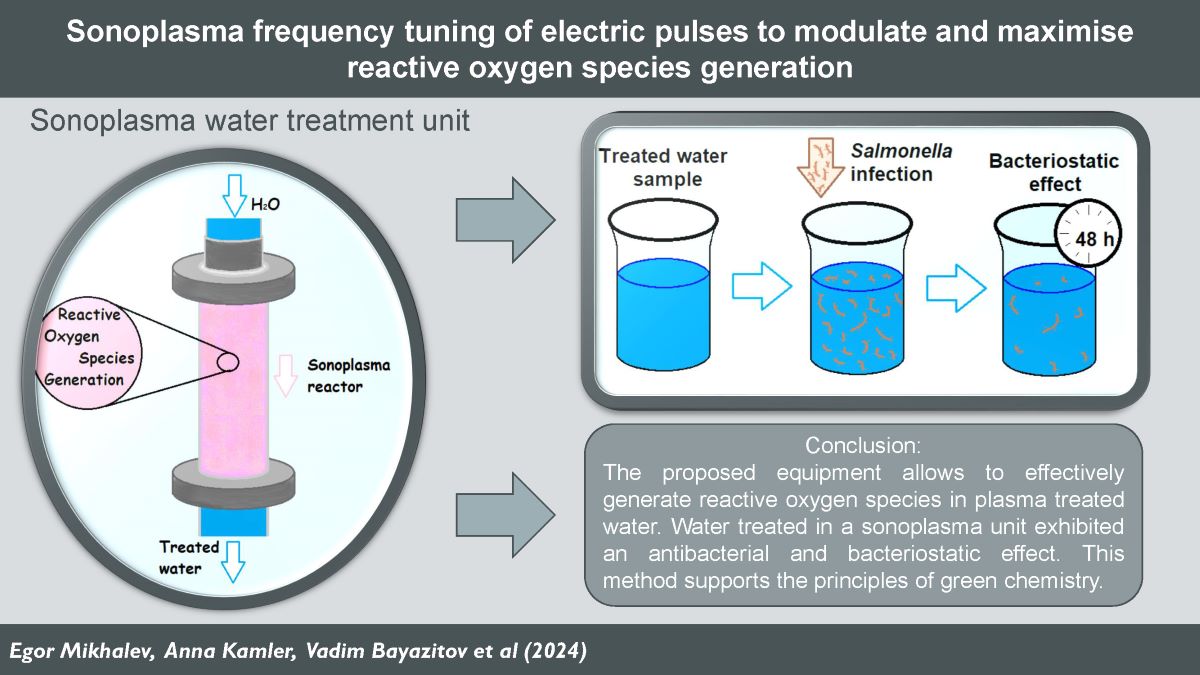

The equipment for combined effect of hydrodynamic cavitation and plasma discharge developed in the present work is based on the fact that the water flow passes through the hydrodynamic emitter and enters the area of reduced pressure, as a result of which the liquid starts to cavitate. This approach can significantly reduce the energy cost of plasma discharge generation in water and can also be successfully applied in flow reactors, which simplifies its use in many industrial applications.

The purpose of this work is to investigate the possibility of influencing the efficiency of the ROS generation process in the reactor by adjusting the characteristics of the electrical signal applied to the electrodes, as well as to optimise the energy consumption of the developed equipment. In addition, the authors of this article were faced with the task of determining the minimum concentrations of ROS formed in water after sonoplasma discharge treatment, sufficient to achieve prolonged suppressive effect on microbial growth.

2. Materials and Methods

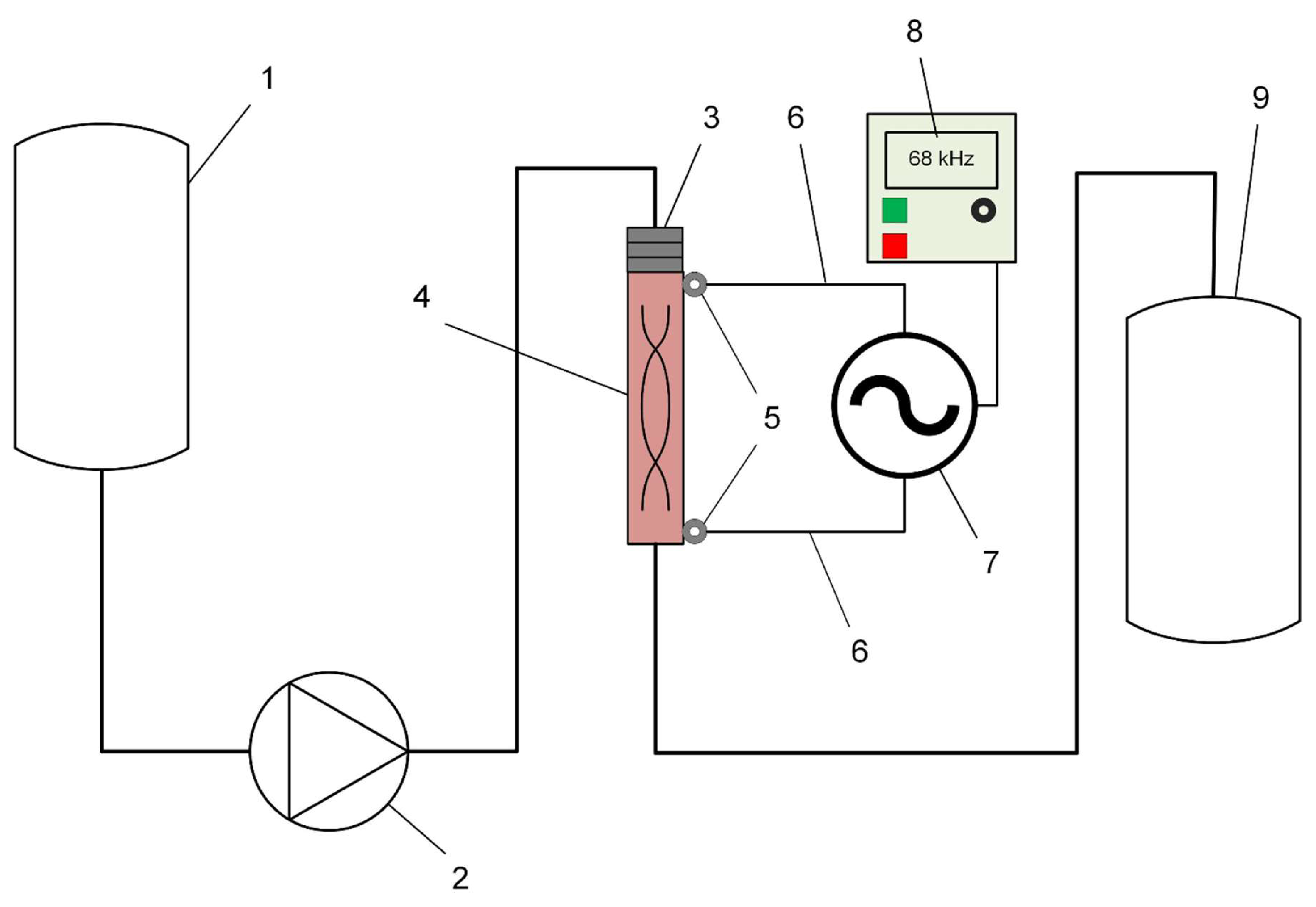

Figure 1 shows the schematic of the experimental unit for water treatment by plasma discharge under cavitation conditions. In this unit configuration, a constant flow of water pumped by a pump at 40 bar pressure enters the reactor tube, where a hydrodynamic emitter is used to create a cavitation field. A stable plasma discharge is maintained in the reactor by applying an alternating voltage in the frequency range from 30 to 70 kHz with an amplitude of up to 4 kV. The pulse frequency is set directly on the generator panel. The amplitude of the secondary winding current during plasma combustion can reach up to 9.3 A, depending on the current treatment mode. The capacity of this equipment is 12 litres/minute.

Electrical power measurements were made with a Tektronix TPS 2024B four-channel oscilloscope between the generator and the high voltage unit. Also, oscillograms were obtained to take voltage and current readings on the windings and to calculate the plasma combustion time.

Chemiluminescence analysis was performed at room temperature on a 12-channel Lum-1200 chemiluminometer (DISoft LLC, Russia, Moscow). Chemiluminescent probes are compounds that react with ROS or organic free radicals to form product molecules in an excited electronic state. The observed luminescence is due to the transition of molecules to the ground state, which leads to the emission of photons. The highly sensitive luminol analogue L-012 was used as an indicator of hydrogen peroxide in treated water. This indicator is a chemiluminescent probe sensitive to the formation of reactive oxygen species, namely various radicals, hydrogen peroxide, etc. [

28,

29,

30].

Determination of hydrogen peroxide concentration in plasma-treated water was performed according to the standard titration technique: 20 ml of cooled sulfuric acid solution (normality 2 N) was added to an aliquot (100 ml) of the analysed sample, after which the solution was stirred and titrated with a standardised solution of potassium permanganate with a concentration of 0.0159 N until the appearance of a weak pink colour stable for 2 min. This standardised methodology is based on the redox reaction of interaction of potassium permanganate with hydrogen peroxide in an acidic environment [

31,

32]:

In this work, distilled water was treated in different modes of operation of the plasma unit. All obtained water samples were passed through the reactor tube only once. A series of studies were carried out to determine the dependence of the concentration of hydrogen peroxide generated in water during plasma combustion on the power input to the generator operation. The power was adjusted by changing the frequency of electrical pulses. To evaluate the decomposition time of hydrogen peroxide in treated water, samples were collected in specially prepared glass containers and stored out of reach of sunlight.

The study of bactericidal and bacteriostatic properties of distilled water after its treatment in the sonoplasma unit was carried out using a biological test system Salmonella typhimurium (CFU =4×107/ml).

Salmonella typhimurium substrate (CFU =4×107/ml) was diluted in treated water samples in 3 disposable tubes at ratios of 1:10, 1:100, 1:1000. 1 cm3 of the original suspension was transferred to a disposable tube with 9 cm3 of sample water for 1:10 dilution of the substrate. The same procedure was followed to obtain 1:100 and 1:1000 dilutions. Then, 0.05 cm3 of each of the 3 dilutions of artificially contaminated water was sown onto a Petri dish with meat-peptone agar as solid nutrient medium. The samples were incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours. The described procedure was repeated at specified time intervals (1, 3, 17, 24, 24, 48 and 72 hours). Contaminated water samples were stored at 22±2oС. The control sample was untreated artificially contaminated distilled water.

The counting of microbial colonies in the obtained samples was carried out according to the formula:

where

M is the number of cells,

a is the average number of colonies at seeding, 10

n is the dilution factor,

V is the sample volume (1 ml).

3. Results

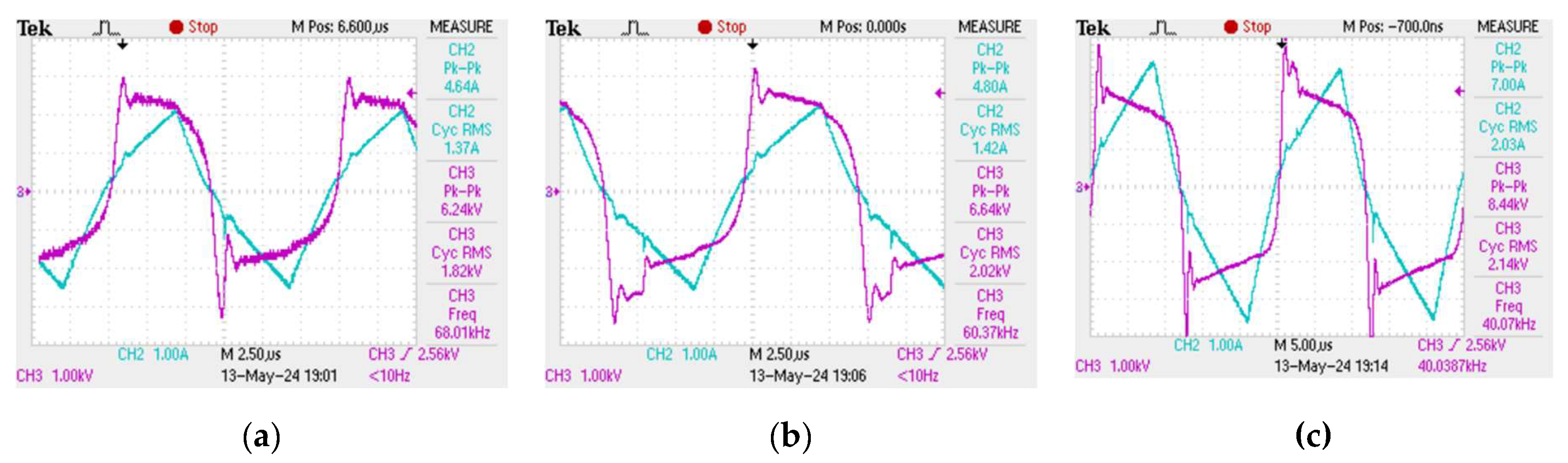

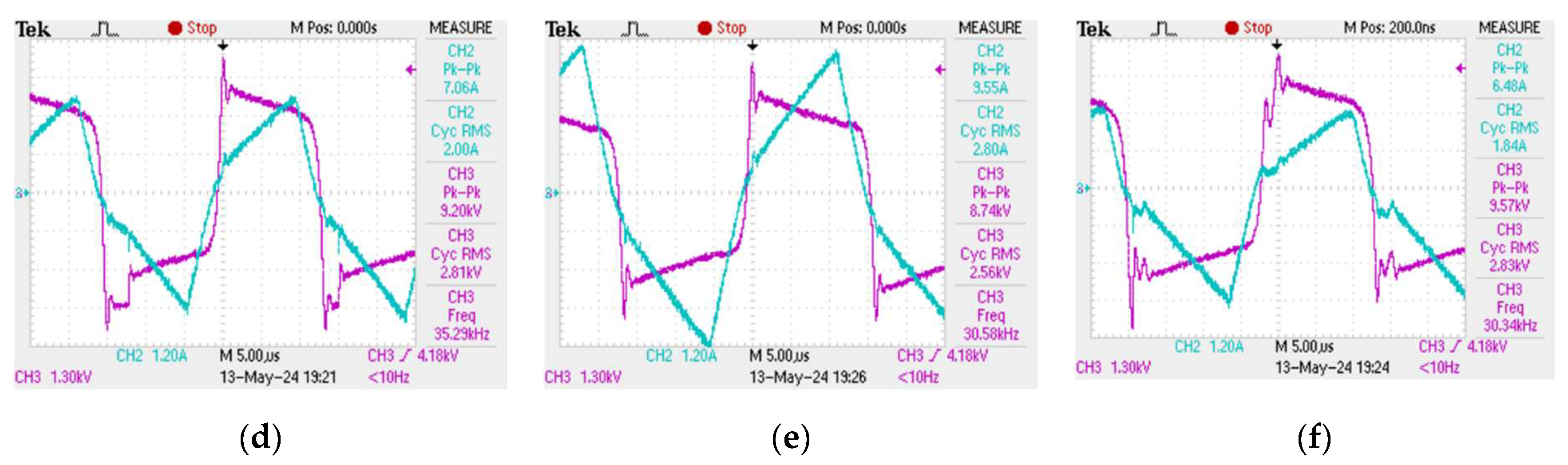

3.1. Plasma Combustion Process

The plasma discharge in the reactor tube does not form immediately when an alternating voltage is applied to the electrodes at the ends of the tube. In order for the plasma combustion process to begin, the medium must be saturated with hydrogen and hydroxyl radical ions, which arise as a result of the decomposition of the water molecule during the collapse of cavitation bubbles. However, once saturation occurs, the resulting plasma discharge in the tube cannot be kept constant - the plasma combustion process is periodic in time with characteristic periods of the order of 2 - 12 µs, which makes it imperceptible to the human eye, however, the obtained oscillograms show that the plasma combustion process is a "flickering" at high frequency [

33]. Oscillograms of current and voltage, from which the plasma combustion time was determined at different frequencies of electric pulses, are presented in

Figure 2.

Plasma generation in the reactor starts at the moment of a sudden voltage spike, then, the plasma discharge is maintained while the current increases linearly and the voltage decreases. Once the current starts to drop, the plasma fades out until the next voltage spike. Consequently, one period of the plasma combustion process contains two characteristic time intervals: the plasma combustion time

, and the idle time

, when water flows through the reactor without plasma treatment. It can be seen from the obtained oscillograms that the ratio between

and

is not constant and depends on the frequency of electrical pulses. Thus, it becomes possible to achieve more efficient plasma generation at certain modes of operation of the unit when most of one period is plasma combustion time

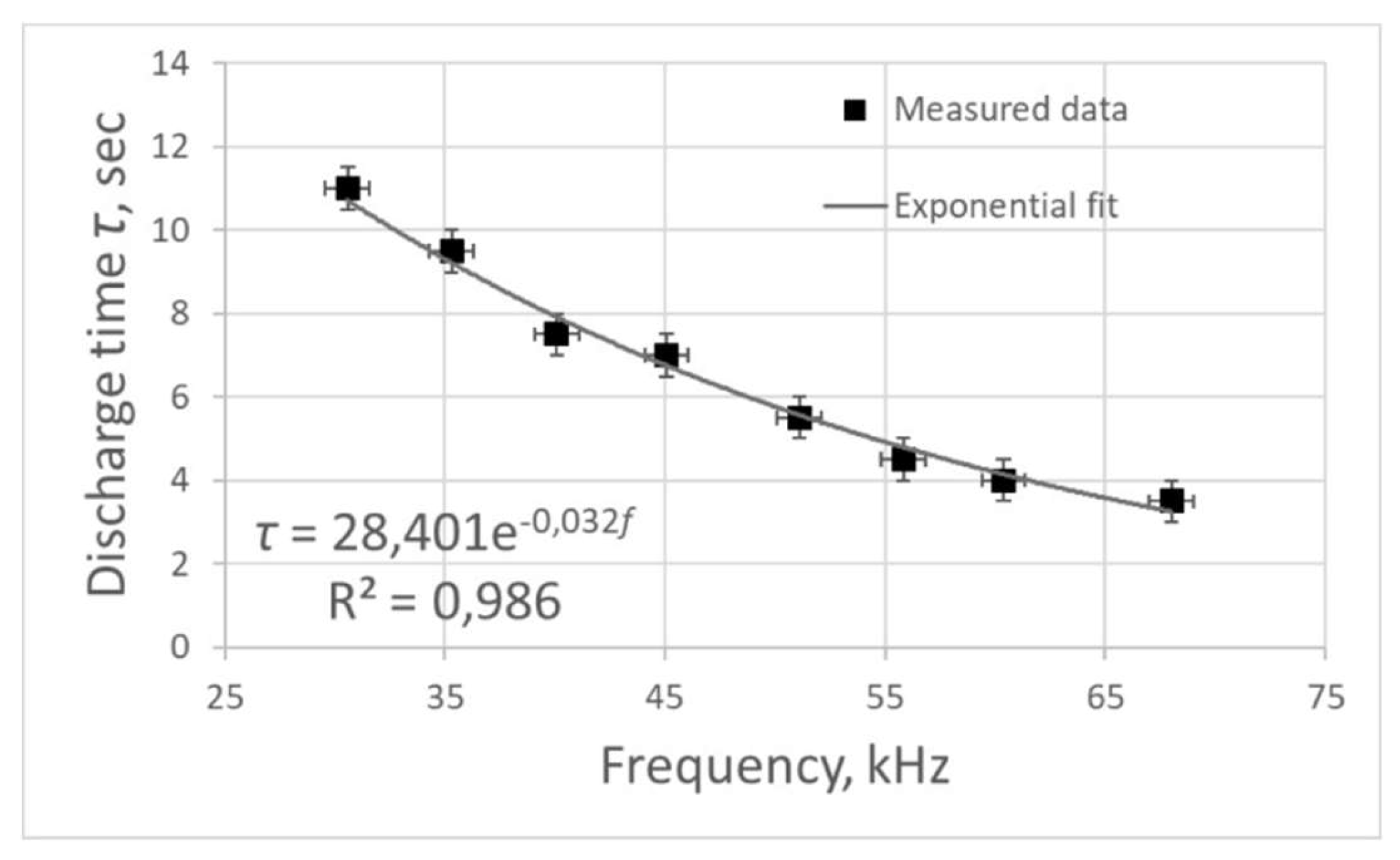

. The dependence of the plasma combustion time on the frequency

of electric pulses

f was obtained (

Figure 3). This dependence was approximated with a high degree of accuracy by an exponential curve, the approximation equation is as follows:

Increasing the frequency of electric pulses leads to a decrease in the plasma combustion time. In addition,

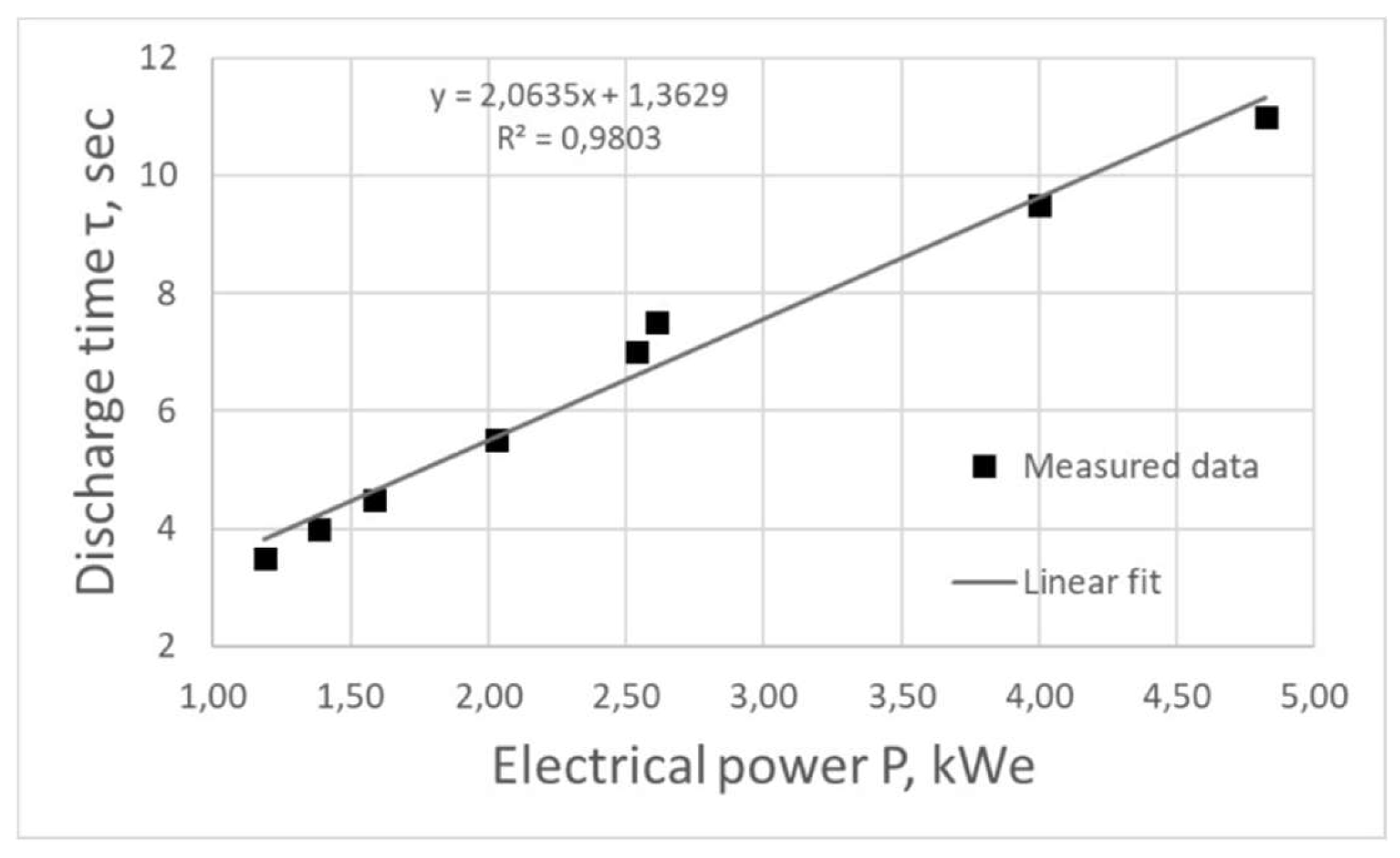

Figure 4 shows the dependence of the plasma discharge combustion time on the generator operating power P, which was linearly approximated by the least squares method:

Decreasing the frequency of electric pulses leads to an increase in the time of plasma combustion in the reactor, however, the energy consumed for the whole process also increases. Based on the fact that the combustion time increases linearly with increasing power, we can speak about high energy efficiency of the equipment at the considered frequency range.

3.2. Hydrogen Peroxide Generation in the Process of Plasma Combustion

Many literature sources provide data that the plasma generated after the formation of a cavitation field in the reactor initiates chemical reactions leading to the formation of reactive oxygen species [

34]:

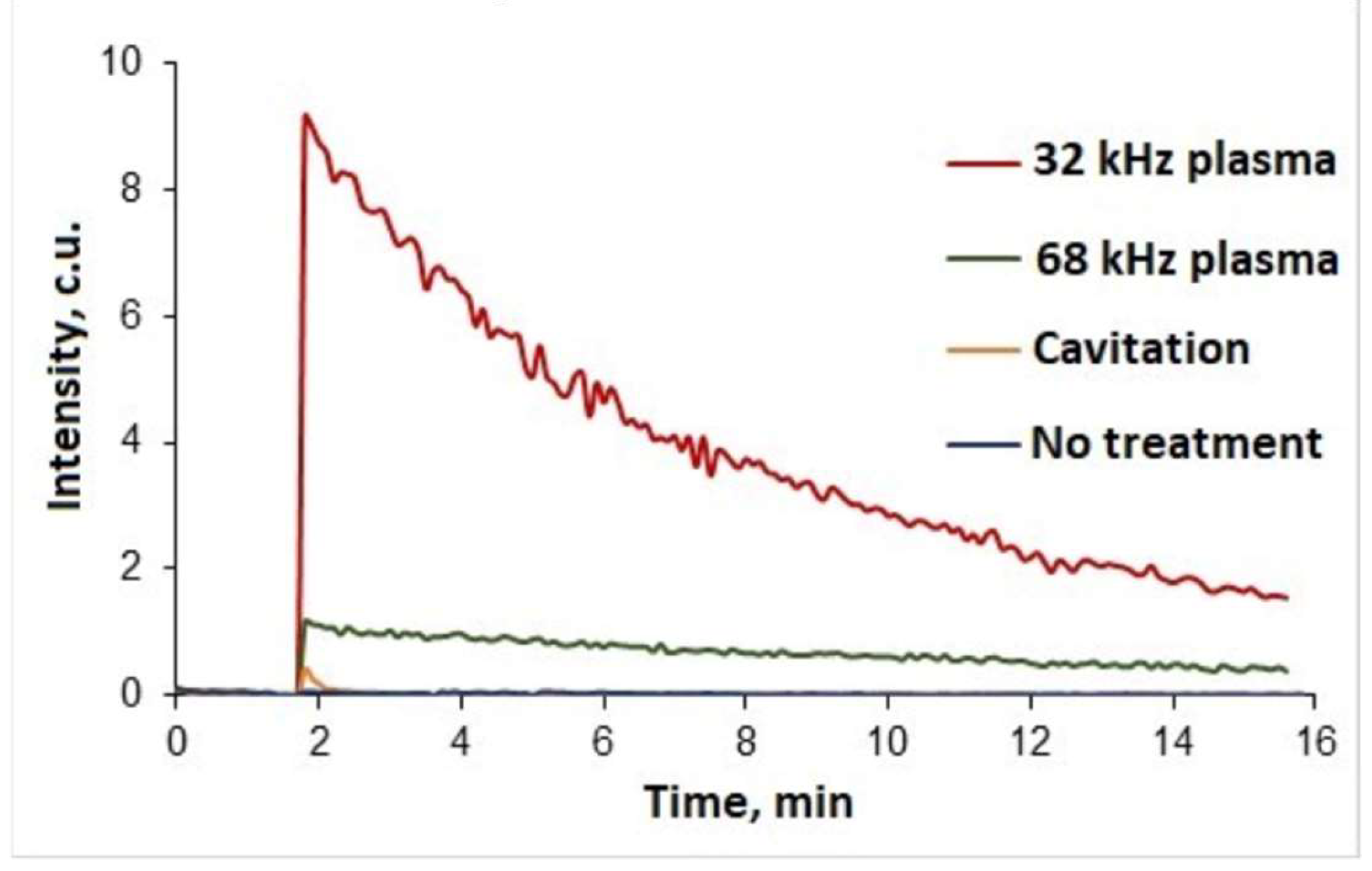

Qualitative analysis of samples using chemiluminescence probe L-012 was carried out to indicate hydrogen peroxide in treated water. A reaction followed by a strong intensity glow was detected for water samples treated at two different frequencies (

Figure 5). In addition, a water sample was analysed after cavitation treatment without plasma ignition, however, in this case the resulting luminescence can be considered insignificant. L-012's high intensity glow can be an indicator of both hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl or superoxide anion radicals. However, such free radicals are extremely unstable and characterised by very short lifetimes (milliseconds to seconds) [

35,

36]. Since the samples were analysed one hour after plasma discharge treatment, it can be assumed that hydrogen peroxide is the main cause of the glow.

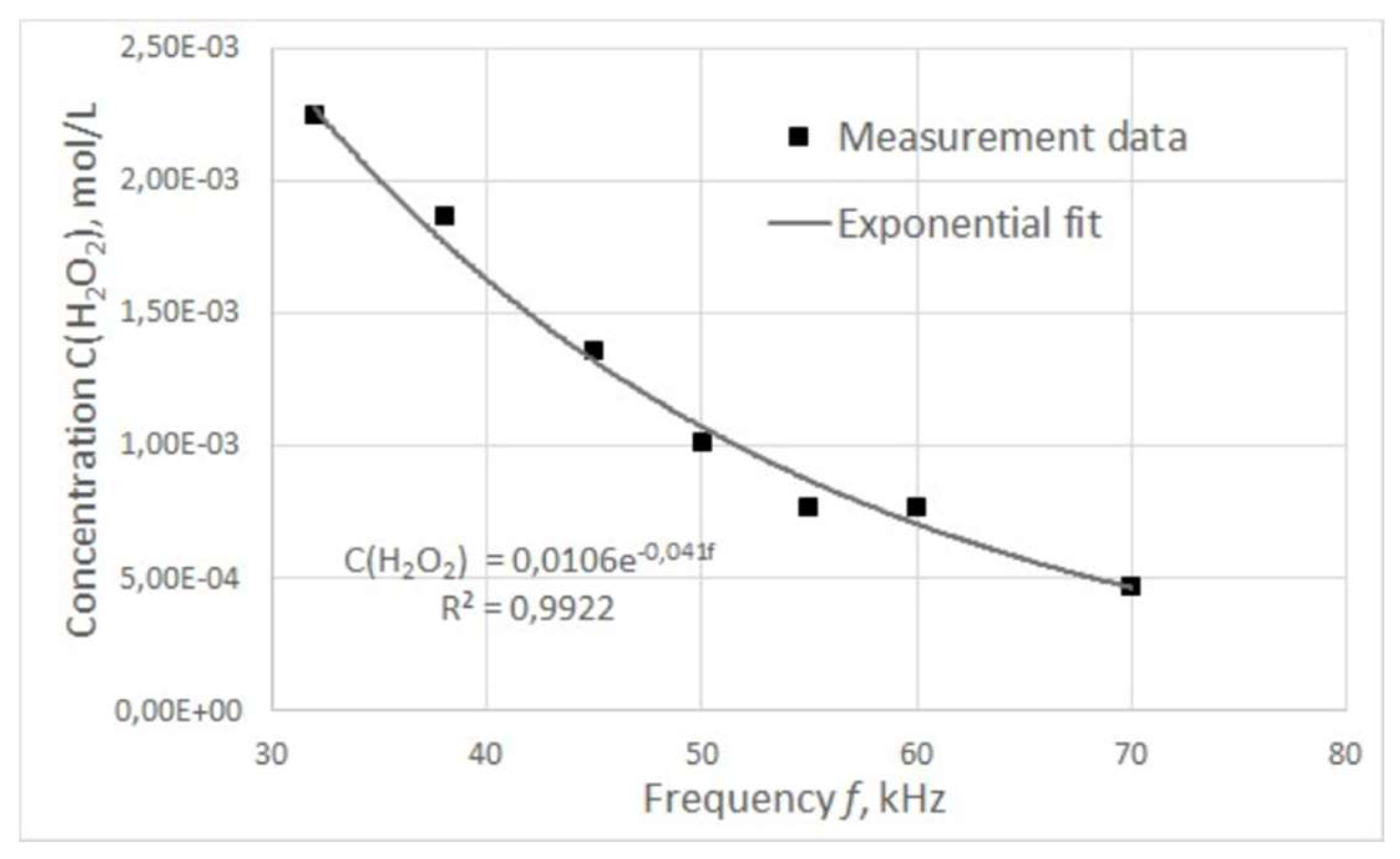

The graph of the dependence of hydrogen peroxide concentration in treated water on the pulse frequency is shown in

Figure 6.

The concentration of hydrogen peroxide was found to decrease with increasing pulse frequency, and this dependence was approximated with a high degree of accuracy by an exponential curve described by the following equation:

Where – measured concentration of hydrogen peroxide, – power of electric pulses.

This dependence may be due to the fact that the plasma combustion time, and hence the power of electric pulses, changes nonlinearly with increasing frequency.

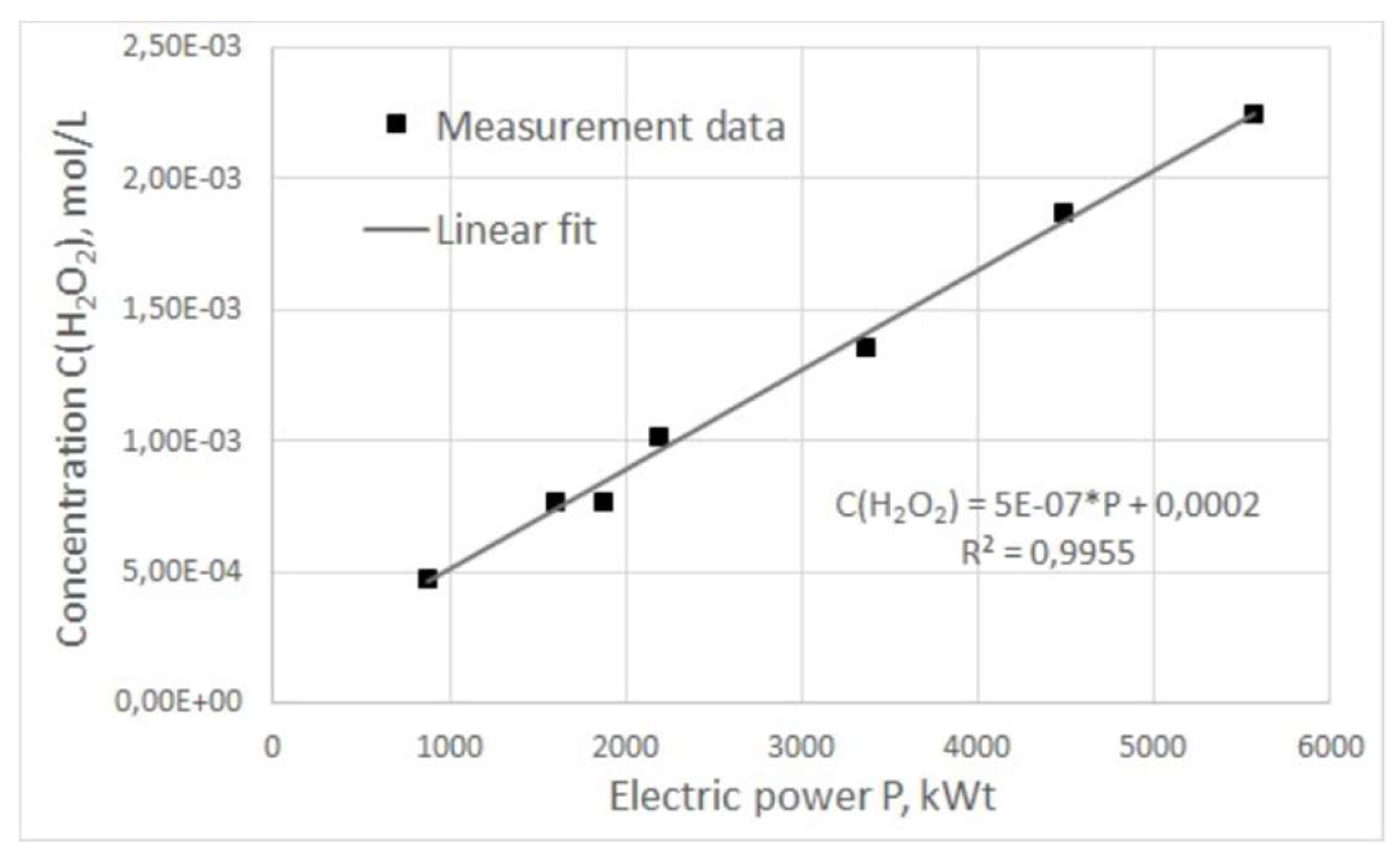

The dependence of hydrogen peroxide concentration on pulse power was also obtained (

Figure 7). It can be seen from the above graph that the concentration of hydrogen peroxide increases directly proportional to the increase in power input over the entire operating frequency range of the generator. The obtained curves for hydrogen peroxide concentration as a function of frequency and power of electric pulses show a clear correlation with the same dependences for plasma combustion time. It can be assumed that the natural reason for the increase of hydrogen peroxide concentration in treated water is the increase in the duration of plasma combustion in the reactor in one period, which, in turn, can be achieved by adjusting the characteristics of electrical pulses.

Since the water flow through the reactor does not depend on the generator operating modes but is determined only by the pump pressure, this means that as the ratio between the plasma combustion time and the entire process period increases, the volume of liquid treated in the reactor relative to the total volume of liquid flowing through the reactor also increases. Thus, it can be concluded that the increase in the efficiency of hydrogen peroxide generation by adjusting the frequency and, accordingly, the power of electrical pulses is not primarily due to a change in any physical or chemical characteristics of plasma combustion, but to a direct increase in combustion time.

3.3. Decomposition of Hydrogen Peroxide Over Time

Despite the fact that pure hydrogen peroxide can remain stable for quite a long time, it is known that the covalent bond O - O has low resistance to breakage, which means that the hydrogen peroxide molecule easily reacts and decomposes under the influence of various substances. The catalyst in the hydrogen peroxide decomposition reaction may be metal ions of variable valence, acids, alkalis and other random contaminants, some of which inevitably enter the solution from the environment under normal storage conditions [

37,

38,

39]. For this reason, stabilisers that deactivate catalytically active substances are introduced into hydrogen peroxide solutions to maintain a constant concentration [

40,

41].

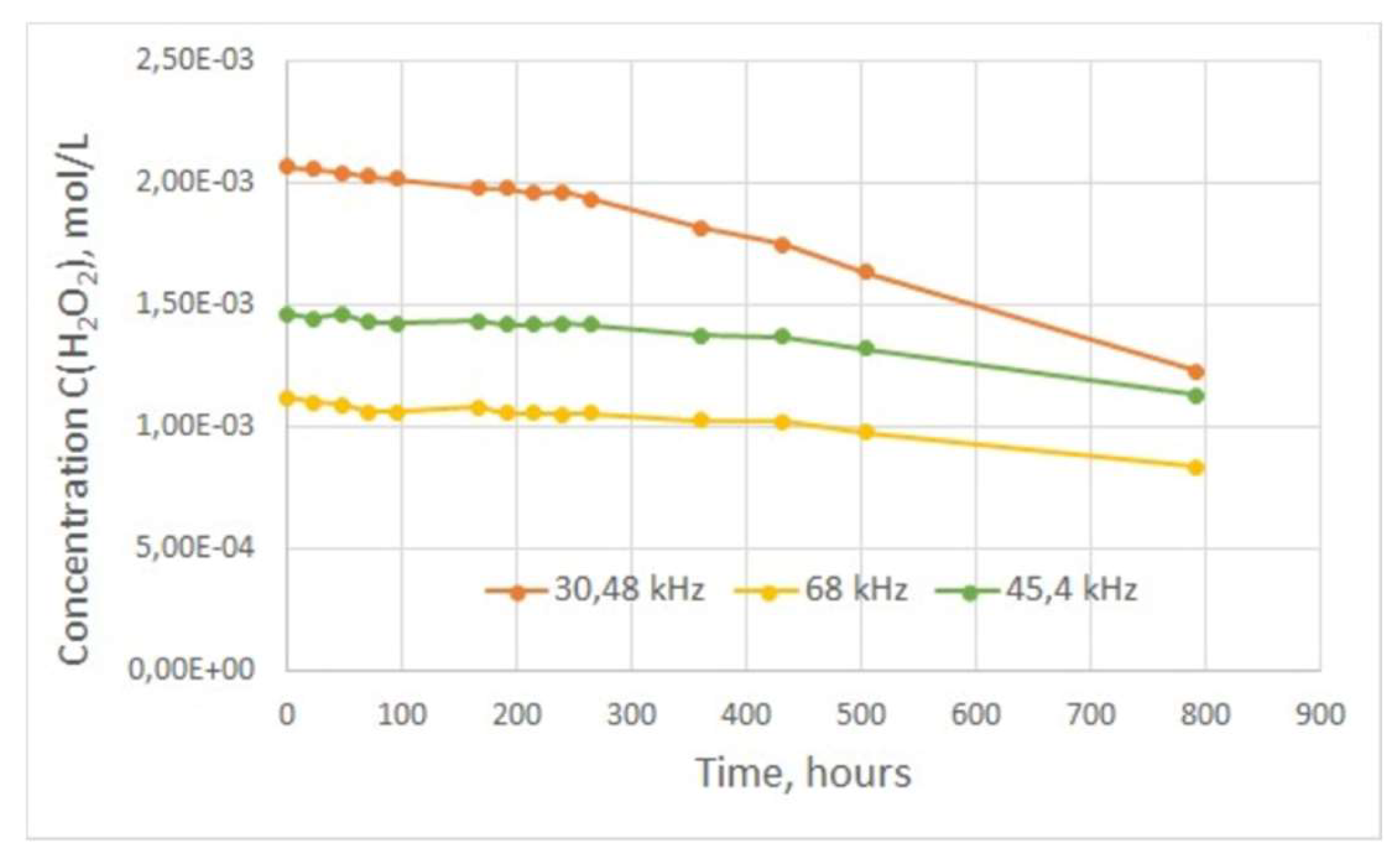

However, the rate of decomposition may decrease at relatively low concentrations of hydrogen peroxide in solution. The decomposition of hydrogen peroxide generated from the treatment of water in the plasma unit was studied in this work (

Figure 8). Thus, the attached graph shows that the concentration of hydrogen peroxide during the first two weeks after treatment decreases slightly (1-2% of the initial concentration), and the hydrogen peroxide content in the water samples can be considered almost constant. After 3 weeks of observation (504 hours), the water sample with the highest concentration of hydrogen peroxide showed the highest decomposition rate; its H

2O

2 content decreased by more than 20%, while for the other two samples this decrease reached no more than 10%.

Thus, hydrogen peroxide persists in the treated water for the first 14 days after treatment with little change in concentrations, but slowly decreases with time. This means that the treated water has redox properties for a relatively long time after passing through the plasma reactor. Consequently, it is necessary to make an estimate of the required H2O2 content in the treated water for a prolonged bactericidal effect.

3.4. Results of Water Testing for Antibacterial Activity

Data on bactericidal and antibacterial properties of water treated with plasma discharge have already been given in various scientific works earlier [

42,

43]. These properties may be primarily due to the formation of hydrogen peroxide, singlet oxygen and other reactive oxygen species during plasma combustion in a volume of water. The reactive oxygen species enter into an oxidation reaction and decompose various organic contaminants for some time after water treatment.

The results of evaluation of bactericidal properties of water treated by plasma discharge under hydrodynamic cavitation conditions are presented in

Table 1. For analysis, dilution with culture of water samples treated with plasma discharge at 68 kHz electrical pulse frequency was prepared.

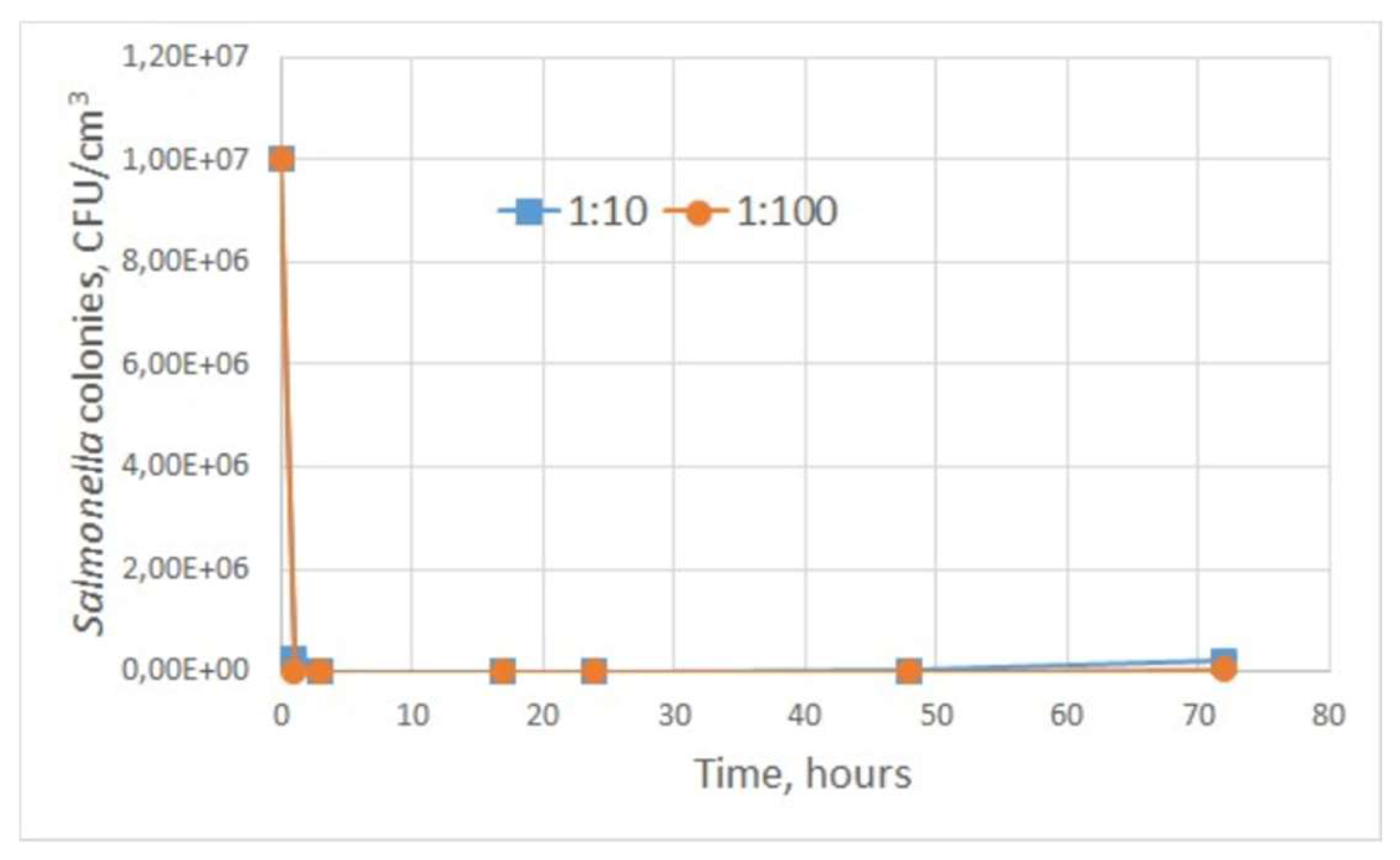

Based on the obtained data (

Table 1) it can be concluded that during the first 17 hours the number of microorganism colonies decreased exponentially (for dilutions 1:10, 1:100). Between 17 hours and 48 hours, bacterial growth was completely absent. When the culture was diluted with treated water at a ratio of 1:10, growth of

Salmonella typhimurium resumed after 48 hours of exposure. These trends are demonstrated in the graph (

Figure 9). No bacterial growth was detected throughout the observation period for the treated water samples with

Salmonella culture at a dilution of 1:1000.

The present data suggest that water samples treated with plasma discharge under cavitation conditions have bacteriostatic properties for more than 48 hours after treatment. This result can be explained by the fact that hydrogen peroxide and other reactive oxygen species in water in the concentrations in which they are generated with the proposed equipment are able to block the development of bacterial colonies and microorganisms. Reactive oxygen species react with pollutants and lead to the destruction of microbial cells [

44]. At the same time, as it was shown earlier, these bacteriostatic properties are also due to the low rate of decomposition of hydrogen peroxide in the treated water. Although the rate of hydrogen peroxide decomposition in the presence of biological contaminants can increase significantly [

45,

46], the initial concentrations of hydrogen peroxide in the samples are sufficiently high to maintain the antibacterial properties of the water more than 48 hours after treatment.

4. Discussion

This work demonstrates that with the adjustment of plasma discharge power and frequency tuning in cavitating liquid, the concentration of hydrogen peroxide generated can be modulated and even foreseen according to an empirical formula. This enables precise adjustment of the hydrogen peroxide concentration at the reactor outlet on the base of the specific application. The experimental results were analysed, and a mechanism explaining the dependence of hydrogen peroxide generation on the frequency of electric pulses was proposed. The plasma discharge in the reactor tube is a periodic process with characteristic intervals of up to 20 µs. This periodic process can be divided into two intervals: the active plasma time and the idle time , during which the water is not subjected to plasma treatment. It was found that when the frequency of electrical pulses decreases, the power output of the generator increases. A decrease in frequency, accompanied by an increase in power, extends the plasma irradiation time in the reactor. A study of hydrogen peroxide degradation over time showed that concentrations change only slightly over a prolonged period (up to two weeks). Water treated in a sonoplasma unit exhibited a prolonged redox effect. The antibacterial properties of the treated water were demonstrated using a Salmonella culture, revealing that distilled water treated with electric discharges in a sonoplasma unit maintains bacteriostatic properties for at least 48 hours post-treatment. This can be used to enhance biological protection systems at various industrial productions. Analysis of data on the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide over time and the antibacterial properties of water treated by sonoplasma discharge suggests that treatment at the maximum frequency of electrical pulses (68 kHz) is the most effective. This frequency mode optimizes the rate of decomposition of reactive oxygen species, enhances the antibacterial properties of the treated water, and minimizes the energy costs of generator operation. With our findings generation of reactive oxygen species in water under sonoplasma treatment can be predicted and controlled. The proposed equipment allows to increase the energy efficiency of generation of reactive oxygen species in plasma depending on specific tasks and can find application in various fields of water treatment and sanification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A. K. and G. C.; Data curation, Eg. M.; Formal analysis, A. K.; Investigation, E. M., R. N. and D. V.; Methodology, M. S., El. M. and M. V.; Project administration, V. B.; Resources, R. N., I. F. and D. S.; Supervision, V. B. and A. I.; Validation, A. K., V. B. and A. I.; Visualization, Eg. M. and I. F.; Writing – original draft, Eg. M.; Writing – review & editing, A. K. and G. C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The article was prepared within the project and supported by the grant from Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation program for research projects in priority areas of scientific and technological development (Agreement № 075-15-2024-546).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Cetkovic´, J., Kneževic, M., Lakic, S., Žarkovic, M., Vujadinovic, R., Živkovic, A. et al. Financial and Economic Investment Evaluation of Wastewater Treatment Plant. Water 2022, 14, 122. [CrossRef]

- Rama Rao Karri, Gobinath Ravindran, Mohammad Hadi Dehghani. Chapter 1 - Wastewater—Sources, Toxicity, and Their Consequences to Human Health, Editor(s): Rama Rao Karri, Gobinath Ravindran, Mohammad Hadi Dehghani, Soft Computing Techniques in Solid Waste and Wastewater Management, Elsevier, 2021, 3-33. [CrossRef]

- Mmontshi L. Sikosana, Keneiloe Sikhwivhilu, Richard Moutloali, Daniel M. Madyira, Municipal wastewater treatment technologies: A review. Procedia Manufacturing 2019, 35, 1018-1024. [CrossRef]

- Ta Wee Seow, Chi Kim Lim, Muhamad Hanif Md Norb. Review on Wastewater Treatment Technologies. International Journal of Applied Environmental Sciences 2016, 11, 111-126.

- Ayesha Tariq and Ayesha Mushtaq. Untreated Wastewater Reasons and Causes: A Review of Most Affected Areas and Cities. International Journal of Chemical and Biochemical Sciences 2023, 23(1), 121-143.

- Saurabh Mishra, Anurag Kumar Singh, Liu Cheng, Abid Hussain, Abhijit Maiti. Occurrence of antibiotics in wastewater: Potential ecological risk and removal through anaerobic–aerobic systems. Environmental Research 2023, 226, 115678. [CrossRef]

- David B. Miklos, Christian Remy, Martin Jekel, Karl G. Linden, Jörg E. Drewes, Uwe Hübner. Evaluation of advanced oxidation processes for water and wastewater treatment – A critical review. Water Research 2018, 139, 118-131. [CrossRef]

- Roberto Andreozzi, Vincenzo Caprio, Amedeo Insola, Raffaele Marotta. Advanced oxidation processes (AOP) for water purification and recovery. Catalysis Today 1999, 53, 51–59. [CrossRef]

- Cuerda-Correa, E.M., Alexandre-Franco, M.F., Fernández-González, C. Advanced Oxidation Processes for the Removal of Antibiotics from Water. An Overview. Water 2020, 12, 102-152. [CrossRef]

- Yang Deng, Renzun Zhao. Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) in Wastewater Treatment. Curr Pollution Rep 2015, 1, 167–176. [CrossRef]

- Pignatello, J. J., Oliveros, E., & MacKay, A. Advanced Oxidation Processes for Organic Contaminant Destruction Based on the Fenton Reaction and Related Chemistry. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2006, 36(1), 1–84. [CrossRef]

- Arjunan Babuponnusami, Karuppan Muthukumar. Advanced oxidation of phenol: A comparison between Fenton, electro-Fenton, sono-electro-Fenton and photo-electro-Fenton processes. Chemical Engineering Journal 2012, 183, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Alok D. Bokare, Wonyong Choi. Review of iron-free Fenton-like systems for activating H2O2 in advanced oxidation processes. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2014, 275, 121-135. [CrossRef]

- J. Meijide, G. Lama, M. Pazos, M.A. Sanromán, P.S.M. Dunlop. Ultraviolet-based heterogeneous advanced oxidation processes as technologies to remove pharmaceuticals from wastewater: An overview. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2022, 10, I. 3, 107630. [CrossRef]

- Xin Lei, Yu Lei, Xinran Zhang, Xin Yang. Treating disinfection byproducts with UV or solar irradiation and in UV advanced oxidation processes: A review. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 408, 124435. [CrossRef]

- Jing Jin, Mohamed Gamal El-Din, James R. Bolton. Assessment of the UV/Chlorine process as an advanced oxidation process. Water Research 2011, 45, I. 4, 1890-1896. [CrossRef]

- Monali Priyadarshini, Indrasis Das, Makarand M. Ghangrekar, Lee Blaney. Advanced oxidation processes: Performance, advantages, and scale-up of emerging technologies. Journal of Environmental Management 2022, 316, 115295. [CrossRef]

- Dengsheng Ma, Huan Yi, Cui Lai et al. Critical review of advanced oxidation processes in organic wastewater treatment. Chemosphere 2021, 275, 130104. [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt J. A. Fundamentals of plasma physics. – Springer Science & Business Media, 2013.

- H Conrads and M Schmidt. Plasma generation and plasma sources. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol 2000, 9, pp. 441-454. [CrossRef]

- Bruce R. Locke, Selma Mededovic Thagard Analysis and Review of Chemical Reactions and Transport Processes in Pulsed Electrical Discharge Plasma Formed Directly in Liquid Water. Plasma Chem Plasma Process 2012, 32, 875–917. [CrossRef]

- Daniel Gerrity, Benjamin D. Stanford, Rebecca A. Trenholm, Shane A. Snyder. An evaluation of a pilot-scale nonthermal plasma advanced oxidation process for trace organic compound degradation. Water Research 2009. [CrossRef]

- David R. Grymonpre, Wright C. Finney, Ronald J. Clark, and Bruce R. Locke. Hybrid Gas-Liquid Electrical Discharge Reactors for Organic Compound Degradation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res 2004, 43, 1975-1989. [CrossRef]

- Petr Lukes, Bruce R. Locke. Plasmachemical oxidation processes in a hybrid gas–liquid electrical discharge reactor. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys 2005, 38, 4074-4081. [CrossRef]

- Tampieri F, Giardina A, Bosi FJ, et al. Removal of persistent organic pollutants from water using a newly developed atmospheric plasma reactor. Plasma Process Polym 2018, e1700207. [CrossRef]

- Songlin Nie, Tingting Qin, Hui Ji, Shuang Nie, Zhaoyi Dai. Synergistic effect of hydrodynamic cavitation and plasma oxidation for the degradation of Rhodamine B dye wastewater. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2022, 49, 103022. [CrossRef]

- Arijana Filipi, David Dobnik, Ion Guti´errez-Aguirre et al. Cold plasma within a stable supercavitation bubble – A breakthrough technology for efficient inactivation of viruses in water. Environment International 2023, 182, 108285. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Jiang, D. & Chen, HY. Electrochemiluminescence Analysis of Hydrogen Peroxide Using L012 Modified Electrodes. J. Anal. Test 2020, 4, 122–127. [CrossRef]

- Isuke Imada, Eisuke F. Sato, Masafumi Miyamoto et al. Analysis of Reactive Oxygen Species Generated by Neutrophils Using a Chemiluminescence Probe L-012. Analytical Biochemistry 1999, 271, I.1, pp. 53-58. [CrossRef]

- Ji Sun Park, Sun-Ki Kim, Chang-Hyung Choi et al. Novel chemiluminescent nanosystem for highly sensitive detection of hydrogen peroxide in vivo. Sensors and Actuators: B. Chemical 2023, 393, 134261. [CrossRef]

- Normal V. Klassen, David. Marchington, and Heather C.E. McGowan. H2O2 Determination by the I3- Method and by KMnO4 Titration. Anal. Chem 1994, 66, 18, 2921–2925. [CrossRef]

- Reuben H. Simoyi, Patrick De Kepper, Irving R. Epstein, and Kenneth Kustin. Reaction between permanganate ion and hydrogen peroxide: kinetics and mechanism of the initial phase of the reaction. Inorg. Chem 1986, 25, 4, 538–542. [CrossRef]

- T. Karabassov, A. S. Vasenko, V. M. Bayazitov et al. Electrical Discharge in a Cavitating Liquid under an Ultrasound Field. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2023, 14, 49, 10880–10885. [CrossRef]

- Rohit Thirumdasa, Anjinelyulu Kothakotab, Uday Annapurec et al. Plasma activated water (PAW): Chemistry, physico-chemical properties, applications in food and agriculture. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2018, 77, 21–31. [CrossRef]

- Oldenberg; The Lifetime of Free Hydroxyl. J. Chem. Phys. 1935, 3 (5), 266–275. [CrossRef]

- Attri, P., Kim, Y., Park, D. et al. Generation mechanism of hydroxyl radical species and its lifetime prediction during the plasma-initiated ultraviolet (UV) photolysis. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 9332. [CrossRef]

- Fritz Haber and Joseph Weiss. The catalytic decomposition of hydrogen peroxide by iron salts. Royal Society 1934, 147, I. 861, 332-351. [CrossRef]

- Paulina Pędziwiatr, Filip Mikołajczyk, Dawid Zawadzki et al. Decomposition of hydrogen perodixe- kinetics and review of chosen catalysts. Acta Innovations 2018, 26, 45-52. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad A Hasan, Mohamed I Zaki, Lata Pasupulety, Kamlesh Kumari. Promotion of the hydrogen peroxide decomposition activity of manganese oxide catalysts. Applied Catalysis A: General 1999, 181, I. 1, 171-179. [CrossRef]

- Dasom Oh, Lei Zhou, Daniel Chang, Woojin Lee. A novel hydrogen peroxide stabilizer in descaling process of metal surface. Chemical Engineering Journal 2018, 334, 1169-1175. [CrossRef]

- Antony J. Musker, Graham T. Roberts. The Effect of Stabilizer Content on the Catalytic Decomposition of Hydrogen Peroxide. Conference: 41st AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit. [CrossRef]

- Satoshi Ikawa et al. Physicochemical properties of bactericidal plasma-treated water. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys 2016, 49, 425401. [CrossRef]

- Chih-Yao Hou, Yu-Ching Lai, Chun-Ping Hsiao et al. Antibacterial activity and the physicochemical characteristics of plasma activated water on tomato surfaces. LWT 2021, 149, 111879. [CrossRef]

- Ukuku D. O. Effect of hydrogen peroxide treatment on microbial quality and appearance of whole and fresh-cut melons contaminated with Salmonella spp. International journal of food microbiology 2004, 95(2), 137-146. [CrossRef]

- Raffellini S. et al. Kinetics of Escherichia coli inactivation employing hydrogen peroxide at varying temperatures, pH and concentrations. Food Control 2011, 22(6), 920-932. [CrossRef]

- Hébrard M. et al. Redundant hydrogen peroxide scavengers contribute to Salmonella virulence and oxidative stress resistance. Journal of bacteriology 2009, 191(14), 4605-4614. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).