1. Introduction

With the advent of the digital age, mobile phones have gradually become an indispensable tool for shopping, entertainment, office, finance management, and socializing. According to the survey, as of December 2023, the number of Internet users in China had hit 1.092 billion, the Internet penetration rate reached 77.5%, the proportion of Internet users using mobile phones to access the Internet was up to 99.9%, and the weekly Internet time climbed to 26.1 h per capita [

1]. The remarkable convenience offered by mobile phones, however, has negative effects. For instance, extreme emotional changes and even severe physiological reactions may arise, leading to mobile phone addiction [

2]. As the youth of Generation Z have grown up with mobile Internet, graduate students frequently use mobile phones for communication, schoolwork research, and entertainment [

3] Under academic and societal pressures, they tend to rely on mobile phones for short-term escapism to relieve this pressure. However, the long-term, excessive use of mobile phones not only fails to effectively relieve the actual pressure but also makes situations worse, as it can exacerbate mental pressure and form a vicious circle. Graduate students are increasingly more affected by mobile phone addiction, translating into insufficient research output and stagnant capacity development.

Considering the seriousness of mobile phone addiction and the importance of research self-efficacy (RSE) to graduate students’ development, this study aims to ascertain whether “seeking pleasure” inevitably “saps one's spirit” and how this occurs. By clarifying the relationship between these two aspects, we provide theoretical guidance for improving graduate students’ RSE.

1.1. Research Self-Efficacy

RSE refers to the confidence an individual feels in utilizing acquired skills and abilities to accomplish a specific task when participating in research activities, and it reflects the individual’s subjective evaluation of their own abilities and achievements, as demonstrated in research activities [

4]. Research efficacy has a direct impact on their research attitudes and behaviors, with high efficacy contributing to higher research output [

5], whereas low efficacy potentially acts as a barrier [

6]. Contemporary society has witnessed the popularization of mobile digital terminals (such as smartphones), and the problem of mobile phone addiction is becoming increasingly prominent among graduate students, thus affecting their research efficacy and output. Graduate students are likely to be deficient in face-to-face communication abilities and other social skills if they are addicted to mobile phones [

7], and the consequences may include negative impacts on teamwork, academic exchanges, and collaborative publications in research activities. In addition, the prolonged use of mobile phones may harm their physical and mental health [

8] through anxiety and sleep disorders, among others [

9]. In the long term, their motivation to study and research can decrease, as can their RSE.

1.2. Analysis of the Relationship between Mobile Phone Addiction and Research Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy is a crucial element of social cognitive theory and forms the social basis for thought and action. The renowned psychologist Bandura defines it as “the belief in one’s capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to manage prospective situations” [

10]. Such belief relies on the psychosocial interactions between four constructs: performance outcomes, vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion, and physiological feedback [

11]. RSE, which is derived from self-efficacy, is one of the main factors that affect students’ success in conducting research [

12]. RSE denotes the confidence of an individual in utilizing acquired skills and abilities to accomplish a specific task during research activities [

4]. Mobile phone addiction occupies a large part of students’ time, which means less time can be devoted to research activities. Therefore, it directly affects the development of research efficacy. Smartphone multitasking that is unrelated to the research may hinder the cognitive processes required for learning. Researchers respond to smartphone notifications by switching tasks if they get distracted by them at work. This interrupts their research and diverts their mental resources to non-academic tasks [

13], thus crowding out research time.

1.3. Analysis of Mental Stress and Its Mediating Effects

Generally, mental stress is considered a critical mediating variable when navigating the relationship between mobile phone addiction and research efficacy. Mobile phone addiction refers to individuals’ over-reliance on mobile phones to the point where it interferes with the routine of daily life and work. Previous studies have focused on mental stress as an antecedent variable for mobile phone addiction, but most Generation Z students have varying degrees of mobile phone-dependent behaviors due to their exposure to digital technology from childhood; therefore, reliance on technology played a significant role in their upbringing.

Graduate students are under multiple external stressors, including school, work, and family [

14]. To cope, they generally seek psychological solace and escape through excessive mobile phone use [

15]. However, the excessive, long-term use of mobile phones not only fails to effectively relieve the actual stress, but it can also exacerbate mental stress and create a vicious circle. Rosen’s team observed that such addiction affects psychological states and causes agitation, anxiety, depression [

16], and a severe lack of self-confidence. Meanwhile, Leep noted that higher stress and anxiety and lower academic performances are associated with higher mobile phone use [

17]. Deteriorating mental stress is a consequence of mobile phone addiction. Sustained mental stress depletes an individual’s limited mental resources [

18], reduces attention and commitment to the research, and ultimately affects their research efficacy. Moreover, this efficacy is only further reduced by greater dependence on mobile phones, which accompanies more mental stress.

1.4. Analysis of Stress Mindset and Its Modulating Effects

Stress mindset refers to an individual’s mental attitude and behavioral tendency in the face of stress, challenges, or difficulties and can be categorized into the stress-is-enhancing mindset and stress-is-debilitating mindset 19]. Individuals with the former type are optimistic, self-confident, and adaptable. They are more determined and active in seeking solutions to problems when confronting difficulties; this is conducive to their adaptation and growth. In contrast, however, individuals with the stress-is-debilitating mindset tend to be negative, anxious, and avoidant. They may experience helplessness, frustration, and anxiety, and they fail to effectively solve problems. Therefore, evasion and avoidance are their responses to hardships, resulting in worsening crises and mental health problems. Relatively speaking, adolescents with a stress-is-debilitating mindset would suffer significantly higher levels of distress under adversity [

20].

Mobile phone addiction manifests externally in persistence, immersion, and long-duration use. Its deeper impacts can be observed in the dysfunction of external benign habits and rhythms. Therefore, it creates an imbalance of implicitly internal mental states, such as pronounced mental and social functioning damage to individuals [

21]. Under the effects of mobile phone addiction, those who possess a stress-is-enhancing mindset are capable of rationally treating the positive effects of mobile phone use (e.g., the diversionary effects of entertainment and socialization), thereby reducing mental stress. On the contrary, the stress-is-debilitating mindset forces individuals to regard excessive mobile phone use as a waste of time, and this would spawn an increase in anxiety, guilt, and even greater mental stress.

Regarding the effects of mobile phone addiction on research efficacy, individuals who possess a stress-is-enhancing mindset enjoy more resource advantages from mobile phones and better research efficacy from peer support. In contrast, those with a stress-is-debilitating mindset are more likely to reap fewer benefits from using mobile phones, and their research efficacy will be further weakened by the uncertainty of research outputs and the long cycle of publication.

2. Goal of the Study

This study aims to measure the mechanisms of mobile phone addiction on research self-efficacy among graduate students and to further check the mediating effects of mental stress and the modulating effects of a stress mindset.

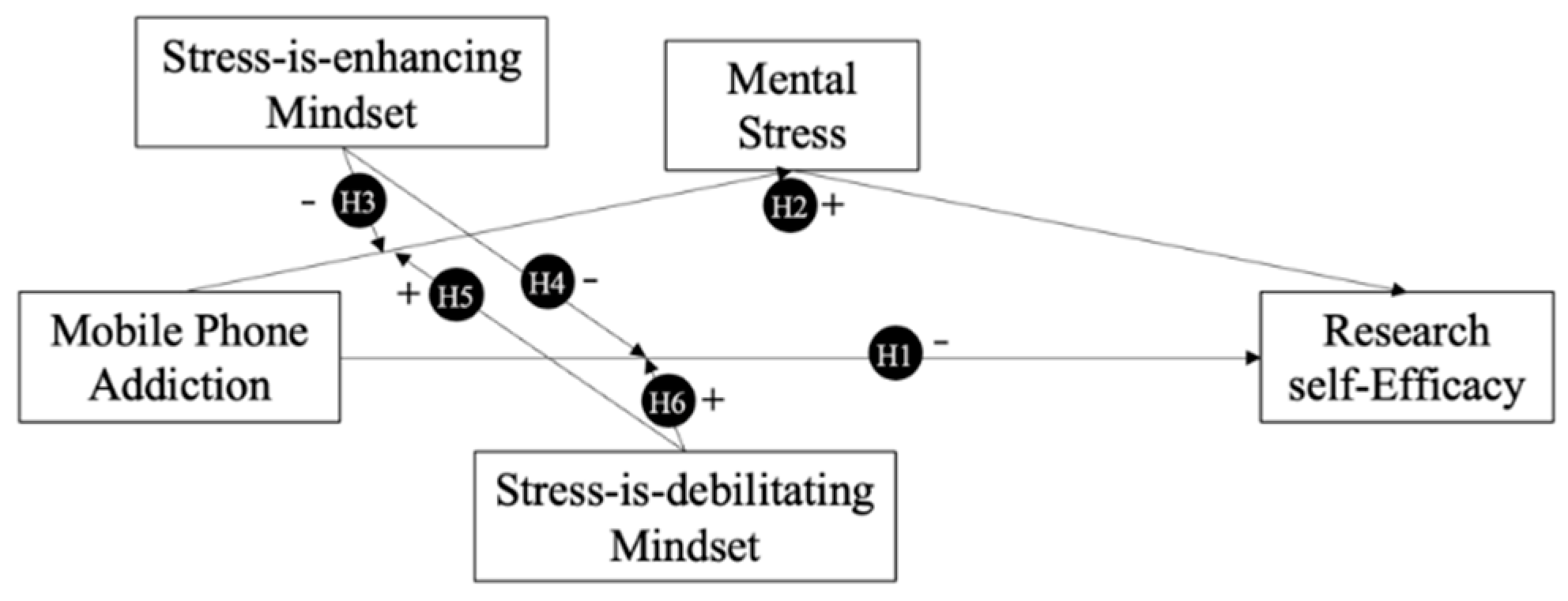

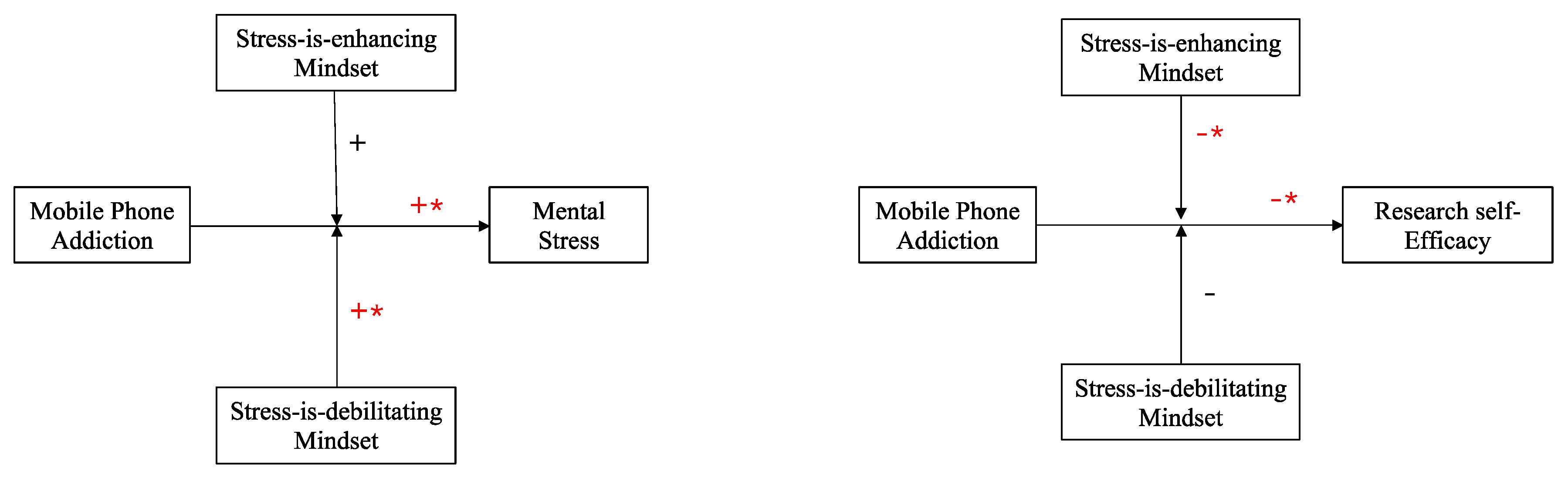

Figure 1 shows the moderated mediation model for the study. The following hypotheses were tested in the study:

H1. Mobile phone addictive behaviors decrease students’ research self-efficacy.

H2. Mental stress can partially leverage the mediating effects between mobile phone addiction and research self-efficacy.

H3. Stress-is-enhancing mindset can reduce the effects of mobile phone addiction on mental stress.

H4. Stress-is-enhancing mindset can mitigate the effects of mobile phone addiction on research self-efficacy.

H5. Stress-is-debilitating mindset can enhance the effects of mobile phone addiction on mental stress.

H6. Stress-is-debilitating mindset can increase the effects of mobile phone addiction on research self-efficacy.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Setting

The questionnaires were distributed online through Wenjuanxing App to universities nationwide to determine the mental stress, research self-efficacy, mobile phone addiction, and stress mindset of graduate students at various universities in China. Finally, 2,278 valid questionnaires were collected and organized after applying the detailed guidelines of the experiments. The participants were 1464 full-time graduate students (mainly) and 814 part-time graduate students. The gender balance was fair, where 1114 (48.90%) were male and 1164 (51.10%) were female. In addition, 372 (16.33%), 491 (21.55%), and 472 (20.72%), respectively, were first-, second-, and third-year master’s degree students. Furthermore, first-, second-, third-, fourth-, and fifth-year participants in doctoral programs were 265 (11.63%), 216 (9.48%), 255 (11.19%), 120 (5.27%), and 87 (3.82%), respectively.

3.2. Measures

The research variables in this study were mental stress, research self-efficacy, mobile phone addiction, and stress mindset. To scientifically and effectively measure the research variables, the following scales were organized and compiled into questionnaires in this study based on various previous efforts.

3.2.1. Mental Stress Scale

This scale was obtained from the test questions in the stress section of

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) [

22]. We set seven items and adopted a five-score method: one represents a complete lack of compliance and five denotes complete compliance. The scale comprises five dimensions: difficulty relaxing, nervous excitement, distraction, allergic reaction, and impatience. In addition, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.902 in this scale, which is a reflection of high reliability and dependability.

3.2.2. Research Self-Efficacy Scale

For this part, seven questions from Black's revised

Research self-Efficacy Scale (RSES) [

23] were selected, and the same scoring method as that in (1) was adopted. Individuals' scores on this scale were proportional to their research self-efficacy. The scale can be divided into three dimensions, namely research methodology and dissemination, regulations and organizations, and interpersonal aspects. The reliability for this round was considerably high, as Cronbach’s alpha was 0.914.

3.2.3. Mobile Phone Addiction Index Scale

We extracted 12 questions from Leung's revised

Mobile Phone Addiction Index Scale (MPAI) [

24]. Similar to the previous scoring system, one denotes “almost never” and five denotes always. The higher the individual's score on this scale, the more dependent they are on their mobile phone. Four dimensions form this scale: inefficacy, avoidance, loss of control, and withdrawal. Cronbach's alpha reached 0.959, and the reliability was even higher.

3.2.4. Stress Mindset Measure

The present study selected six questions from the

Stress Mindset Measure (SMM) [

19] developed by Crum et al., and we extended the aforementioned scoring method; one means “strongly disagree” and five denotes “strongly agree.” The two-side scale comprises a stress-is-enhancing mindset and stress-is-debilitating mindset. The reliability was not as remarkable in this scale as in previous ones, but it remained relatively good, as Cronbach's alpha was 0.810.

3.2.5. Statistical Analysis

This study adopted SPSS 27.0 software for data analysis, and Harman’s single-factor test was adopted to check common method biases. Based on the theory of testing mediating effects proposed by Wen Zhonglin et al., this study analyzed the chain mediating effects and modulating effects under the built-in Process of SPSS [

25].

4. Results

4.2. Common Method Biases Test

Self-report data collection methods are often subject to common method biases, so this study employed anonymization and the reverse scoring of some entries in the procedural aspects. In the next step, Harman’s single-factor test was applied to check common method biases after data recovery. Finally, the results revealed that four factors had eigenvalues greater than 1, and the explained variance of the first factor accounted for 42.425% (less than 50%) [

26]. In summary, no significant problems of common method biases exist.

4.3. Mean, Standard Deviation and Correlation Matrix for Each Variable

The results of descriptive statistics and correlation analysis revealed the following (see

Table 1): mobile phone addiction is highly and negatively correlated with research self-efficacy, stress-is-enhancing mindset, and stress-is-debilitating mindset. Mental stress had a negative relationship with research self-efficacy and the two mindsets, but it had the same growth trend correlation with mobile phone addiction. Research self-efficacy was quite negatively correlated with mobile phone addiction and the stress-is-debilitating mindset, whereas it was positively correlated with the stress-is-enhancing mindset.

4.4. Hypothetical Model Test

4.4.1. Mediation Model Test

The PROCESS 4.1 plug-in for SPSS 27.0 was selected to conduct the mediating effects test [

27] by referring to the bootstrap method proposed by Hayes: model 4 with a sample size of 5000 at the 95% confidence interval. Mobile phone addiction, research self-efficacy (TPI at 5000 ms), and mental stress were, respectively, set as independent variable X, dependent variable Y, and mediator variable M after holding genders, grades, study modes, and degree types in place. The bootstrap results reveal (see

Table 2 and

Table 3) that the indirect effects of the mediating factors do not contain 0 (effect size = -0.079, standard error = 0.014, 95% confidence interval = [-0.107, -0.052]). Additionally, after maintaining the mediating variable of mental stress in balance, the direct effects of mobile phone addiction on research self-efficacy were notable, as 0 was excluded in its 95% confidence interval (effect size = 0.435, standard error = 0.019, 95% confidence interval = [-0.471, -0.398]). Therefore, in light of Zhao et al.'s theory [

28], this result confirms the partially mediating effects on research self-efficacy when mental stress influences mobile phone addiction, thus confirming H1 and H2.

4.4.2. Moderated Mediation Model Test

This study hypothesizes that stress mindset modulates the pathways by which mobile phone addiction affects research self-efficacy and mobile phone addiction affects mental stress. To validate the modulating effects of stress mindset, Model 10 in PROCESS V4.1 was adopted for testing. Controlling gender, grade, study mode, and degree type revealed the following. The product term of mobile phone addiction and stress-is-enhancing mindset is a nonsignificant predictor of mental stress but a remarkable predictor of research self-efficacy. The product term of mobile phone addiction and stress-is-debilitating mindset was a weak predictor of research self-efficacy but was a strong predictor of mental stress. This implies that the stress-is-enhancing mindset can play a modulating role when mobile phone addiction affects research self-efficacy, and stress-is-debilitating mindset could have a similar effect when mobile phone addiction impacts mental stress (see

Table 4).

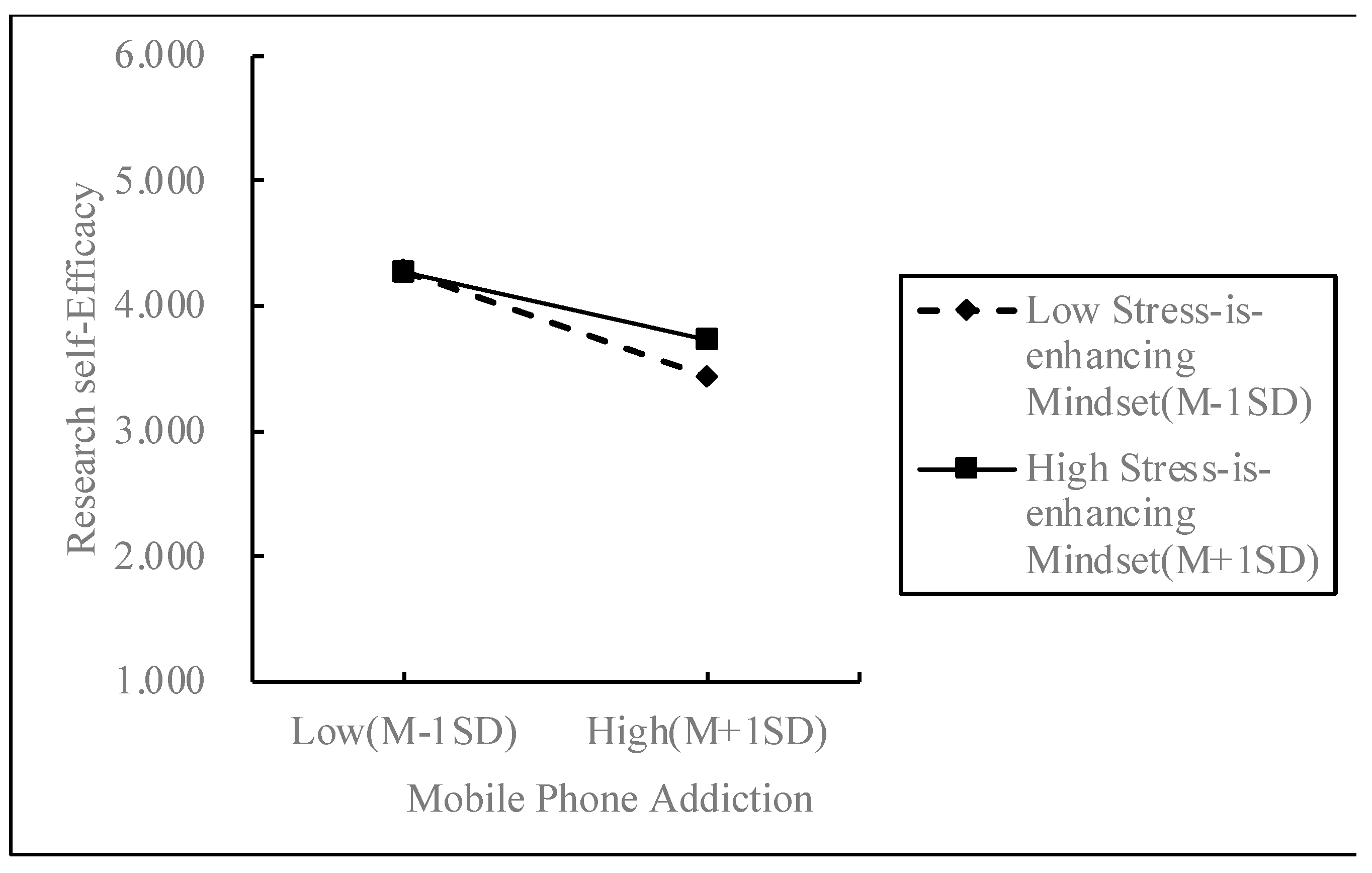

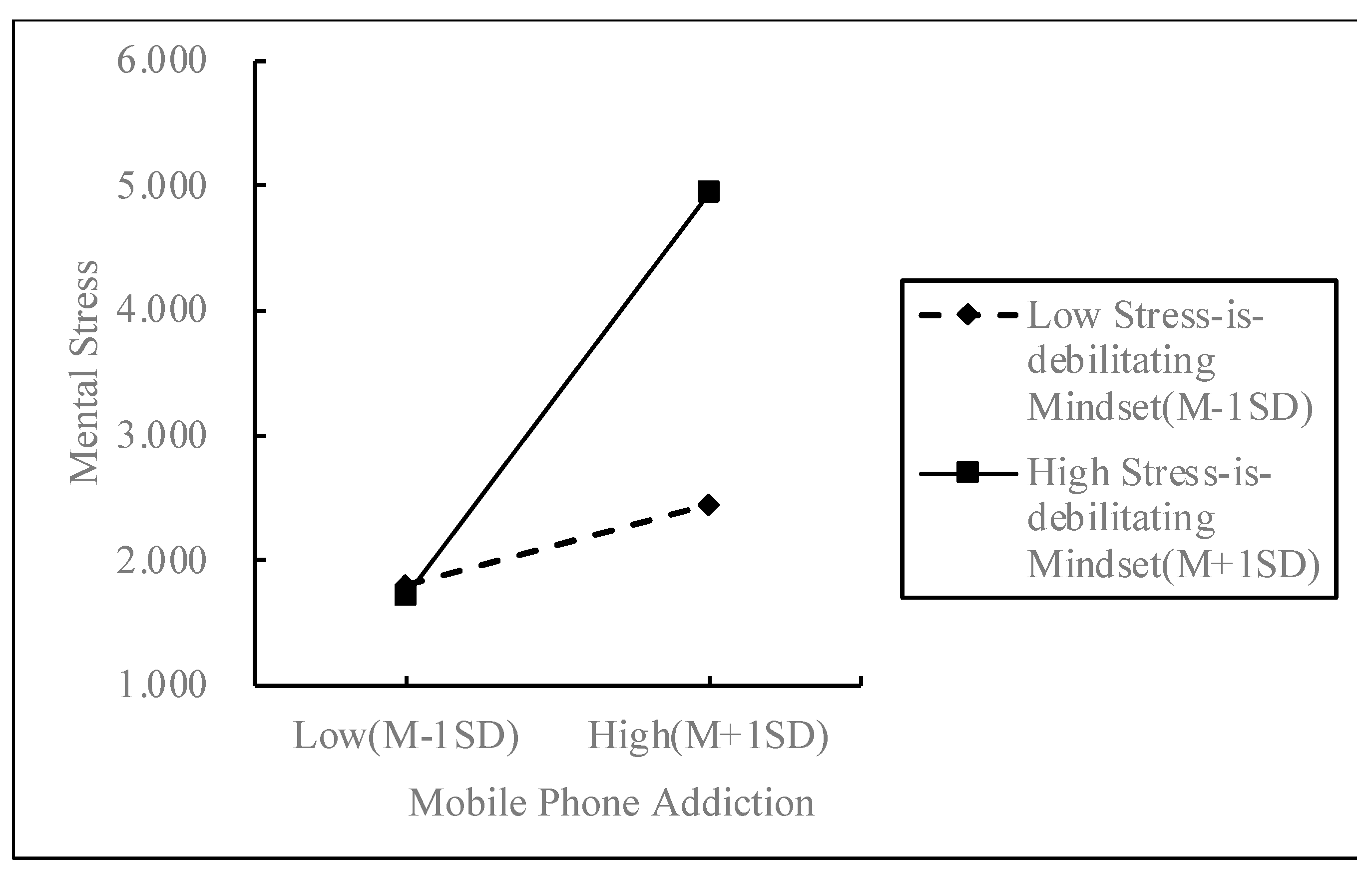

To elucidate the modulating effects of stress mindsets, we categorized participants into high-scored (M+1SD) and low-scored (M-1SD) groups based on the scores of stress mindsets in the present study (encompassing both stress-is-enhancing mindset and stress-is-debilitating mindset). Accordingly, simple slope analyses were afterward conducted bounded by one standard deviation (see Figs. 2 and 3 for specific results).

Figure 2 reveals that the negatively predictive effects of mobile phone addiction on research self-efficacy were significant in the group with a lower level of stress-is-enhancing mindset (M-1SD), with a slope value of -0.439, a t-value of -16.265, and a p-value of less than 0.001. Comparatively, in the group with a higher level of such a mindset (M+1SD), the negative effects are relatively weak, with a slope value of -0.279, a t-value of -9.407, and a p-value, again, of less than 0.001. This is evidence that the negative impacts of mobile phone addiction on an individual's research self-efficacy tend to diminish as the stress-is-enhancing mindset intensifies. The analysis in

Figure 3 reveals an apparent and positive predictive relationship between mobile phone addiction and mental stress in the group whose stress-is-debilitating mindset surpasses others’ (M+1SD), with a slope value of 0.484, a t-value of 18.072, and a p-value of less than 0.001. In contrast, the group of participants with a much lower stress-is-debilitating mindset (M-1SD) only have slight effects of it being a positive predictor: a slope value of 0.332, a t-value of 12.174, and a p-value, again, of less than 0.001. This suggests that the positive predictive effects of mobile phone addiction on mental stress tend to increase as an individual's stress-is-debilitating mindset grows. In addition, as presented in

Table 5, the mediating effect value of mental stress exhibits a downtrend at different levels of stress-is-debilitating mindset. In other words, the “stress-is-debilitating” mindset amplifies negative effects of addiction on scientific research self-efficacy by enhancing the mediating effect of mental stress.

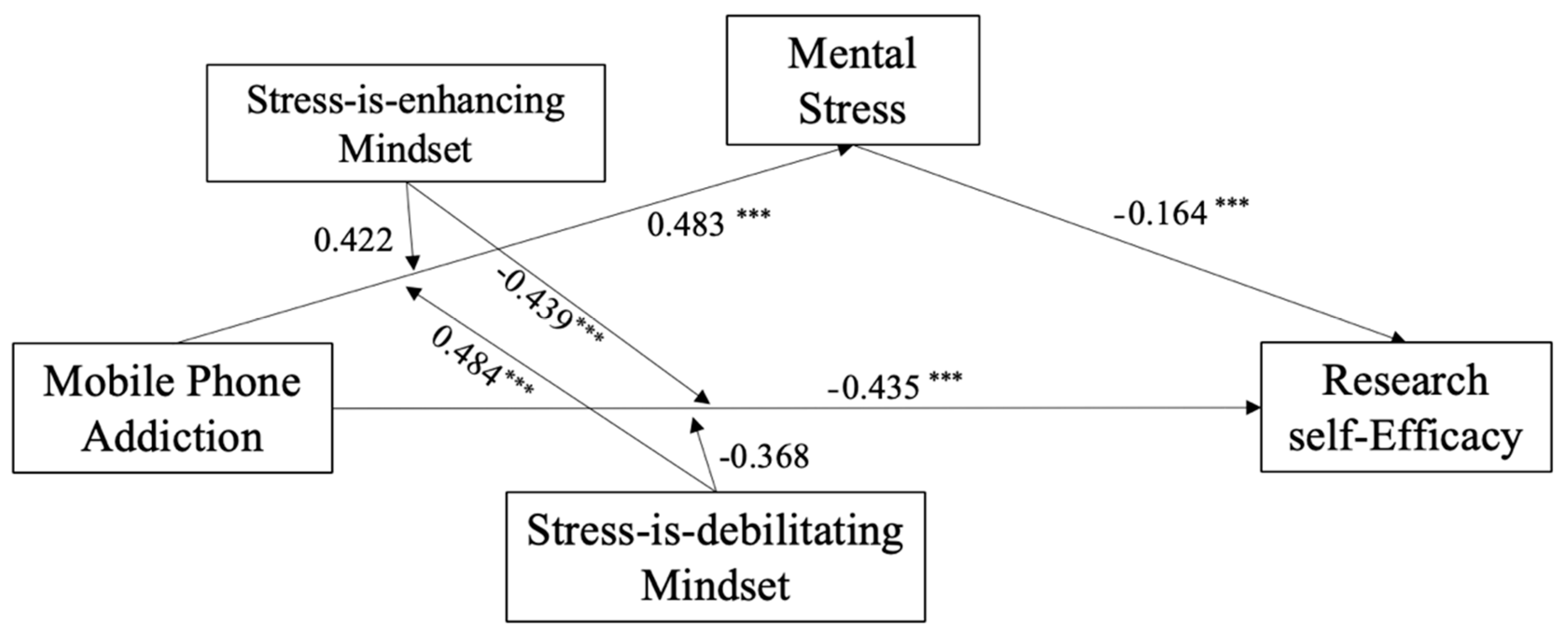

In summary, the modified structural equation model of this study is shown in

Figure 4.

5. Discussion

This study constructed a moderated mediation model, where mental stress was a mediating variable and stress mindset a modulating variable. It is initially observed that seeking pleasure indeed tends to sap one's spirit; mobile phone addiction is very likely to reduce research self-efficacy. In the following, how seeking pleasure saps one's spirit is explained. Specifically, mobile phone addiction influences graduate students’ research self-efficacy via the mediating variable of mental stress. Finally, the negative impacts of such addiction on research self-efficacy can be lowered by interfering with the process mentioned above through the stress mindset.

5.1. Mobile Phone Addiction Has Significantly Negative Impacts on Research Self-Efficacy

The results suggest that the direct effects of mobile phone addiction on research self-efficacy are at -0.435. This validates H1: mobile phone addiction has significant negative effects on graduate students’ research self-efficacy. Considering that this outcome is largely consistent with common sense, the causes can be attributed to several factors. First, the mobile phone is distracting. On the one hand, graduate students lose focus, from class lectures to research projects, owing to the distraction; on the other hand, the learning habits of multitasking or task-switching introduced the accessibility of mobile devices make scientific research involving a high degree of concentration unsustainable [

16]. Second, the use of mobile phones is an “invisible” drain on time. Addiction forces individuals to unconsciously spend a large amount of time on mobile phones [

29], thus reducing the energy devoted to research activities, which directly affects the development of research efficacy. In addition, the longer time spent on smartphones also has negative impacts on a range of offline activities, varying from relationships to academic performances [

30]. Third, the “fear of missing out” mentality is triggered by mobile phone addiction. The generation that has grown up with the Internet and digital devices is reluctant to miss out on what’s happening online, and they have strong desires to maintain interactions with the rest of the world (fear of missing out or “FOMO”). Therefore, they are likely to suffer from inattention and to make insufficient preparations for scientific research [

31]. Fourth, the fragmented information in mobile phones does not offer deep learning experiences and a sense of gain. Lacking academic motivation, students may get bored, and smartphone apps could provide a quick and tantalizing escape [

32]. Immersed in the age of fragmentation, the excessive use of mobile phones exerts a dulling effect, and this over-reliance deteriorates people’s ability to write, remember, and deeply think [

33]. These factors affect the progress or even the results of the research and, ultimately, research self-efficacy.

5.2. Mental Stress Mediates the Relationship between Mobile Phone Addiction and Research Self-Efficacy

The results of this study revealed the partially mediating effects of the model with an effect value of -0.107, which validates H2: mobile phone addiction can predict graduate students’ research self-efficacy through the mediating effects of mental stress. Previous studies have revealed that mobile phone addiction is a positive predictor of mental stress among individuals [

34]. Graduate students are often under tremendous research pressure, and when they return to the real world after engaging their minds in the virtual space, they tend to regret and blame themselves for wasting time and allowing tasks to become more urgent. As, mental pressures [

35] and doubt regarding their research abilities increase, their research self-efficacy can only decline. Additionally, the excessive use of mobile phones may be as emotionally damaging [

36] as anxiety and depression. These issues affect an individual’s mental state, interfere with researchers' thought processes, and influence their decision-making and problem-solving abilities [

37], thereby weakening their self-confidence in accomplishing research tasks and undermining their motivation and initiative when facing research challenges [

38]. In addition, each individual has limited mental resources, which would be depleted by sustained stress [

18]. Such depletion not only exhausts and stresses individuals, it may also weaken their focus and commitment to the research tasks [

39]. As a high degree of concentration and sustained effort in the research itself is required, the persistent effects of mental stress may reduce the amount and quality of time that individuals devote to their research activities. As a consequence, their expectations of the quality and efficiency of finished research tasks and, ultimately, their research self-efficacy will all be negatively affected.

5.3. Modulating Effects of Stress Mindsets Present Different Patterns

5.3.1. Effects of Stress-Is-Enhancing Mindset

The results suggest that a stress-is-enhancing mindset could modulate the effects of mobile phone addiction on research self-efficacy (path: mobile phone addiction → research self-efficacy), with an effect value of -0.439. However, such effects are not remarkable in the relationship between mobile phone addiction and mental stress (path: mobile phone addiction → mental stress), so we can judge that H4 is valid, whereas H3 is not. For the direct-impact path of “mobile phone addiction → research self-efficacy,” the negative effects of mobile phone addiction on research self-efficacy can be weakened by the stress-is-enhancing mindset. This conclusion is also largely consistent with the effects of the stress-is-enhancing mindset, which states that people can develop a positive, mental health-friendly mindset in the face of stress or challenges. This mindset can help people cope better with life’s difficulties and enhance their adaptability and resilience [

19]. Individuals with a stress-is-enhancing mindset can enjoy more resource advantages and peer support, among others, that are associated with mobile phones. Therefore, the negative impacts of mobile phone addiction on research self-efficacy may be lower. However, the analysis of the data in the study suggests that the stress-is-enhancing mindset cannot modulate the effects of mobile phone addiction on mental stress. Specifically, this mindset fails to alleviate the problem of deepening mental stress due to mobile phone addiction, which may be due to mobile phone use occupying a large proportion of cognitive resources, making it difficult for individuals to concentrate and think [

40]. Furthermore, it in turn leads to the depletion of cognitive resources and individuals’ ability to cope with stress. Even if someone has a stress-is-enhancing mindset, effectively mobilizing such a positive mindset to deal with challenges in scientific research may be a struggle.

5.3.2. Effects of Stress-Is-Debilitating Mindset

The results of this study indicate that the stress-is-debilitating mindset could modulate the effects of mobile phone addiction on mental stress, with an effect value of 0.484. However, the modulating effects of mobile phone addiction on research self-efficacy, are not conspicuous, revealing that H5 is valid, whereas H6 is not. For the path of “mobile phone addiction → mental stress,” mobile phone addiction has significantly positive effects on mental stress, which would be strengthened by the stress-is-debilitating mindset. The stress-is-debilitating mindset may worsen the disturbance of such negative feelings based on the emotional and physiological states experienced in a given environment [

41]. The pathway “mobile phone addiction → mental stress” enhanced the negative effects of mobile phone addiction on mental stress. Most of these modulating effects occurred largely because the excessive use of mobile phones leads to emotional problems, such as anxiety and depression. These problems affect an individual's psychological state [

16] and induce deeper mental stress. However, the inability of the stress-is-debilitating mindset to exert modulating effects in the pathway “mobile phone addiction → research self-efficacy” suggests that this type of mindset does not exacerbate the decline in research efficacy due to mobile phone addiction. We attribute this to the “mandatory” nature of scientific research. For every graduate student, research is closely tied to graduation, and their demands of academic realities are first considered, even if the problem of mobile phone addiction is severe.

5.3.3. Further Analysis of Stress Mindset's Modulating Effects

After analyzing the data, we plotted

Figure 5 based on

Figure 4 without considering the significance of modulating effects. Noticeably, the effects of stress mindsets are entirely positive (so is the coefficient) in the path of “mobile phone addiction → mental stress.” In other words, given the problem of aggravating mental stress caused by mobile phone addiction, both the stress-is-enhancing and stress-is-debilitating mindsets worsen the situation. However, the data suggest that only the debilitating mindset is statistically significant, and it is indeed a modulating factor that worsens the effects. Similarly, regarding the path “mobile phone addiction → research efficacy,” the effects of stress mindsets are commonly reversed (negative coefficient). Therefore, for the problem of decreased research efficacy due to mobile phone addiction, both mindsets are reflected as protective factors. The data, however, only disclose that the enhancing mindset is more statistically significant, as it does move the issue in a favorable direction.

The main results of this study can be summarized as follows: which aspect of stress mindset works is determined by the nature of the independent variable affected by addiction. If the independent variable is negative (such as mental stress), then the negative aspect of the stress mindset (stress-is-debilitating) will play a moderating role, and vice versa.

References

- China Internet Network Information Center. The 53rd Statistical Report on the Development of China's Internet [R]. Beijing: 2024.

- Eduardo, P. P., Teresa, M., Monje, R., María, J., Sanchez, R., & León, D. (2012). Mobile phone abuse or addiction. A review of the literature. Adicciones, 24(2).

- Alageel, A. A., Alyahya, R. A., A. Bahatheq, Y., Alzunaydi, N. A., Alghamdi, R. A., Alrahili, N. M., ... & Iacobucci, M. (2021). Smartphone addiction and associated factors among postgraduate students in an Arabic sample: a cross-sectional study. BMC psychiatry, 21(1), 302. [CrossRef]

- Bieschke, K. J., Bishop, R. M., & Garcia, V. L. (1996). The utility of the research self-efficacy scale. Journal of career assessment, 4(1), 59-75. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J. G. (1999). Academics' motivation and self-efficacy for teaching and research. Higher Education Research & Development, 18(3), 343-359. [CrossRef]

- Hemmings, B., & Kay, R. (2010). University lecturer publication output: Qualifications, time and confidence count. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 32(2), 185-197. [CrossRef]

- Yen, C. F., Tang, T. C., Yen, J. Y., Lin, H. C., Huang, C. F., Liu, S. C., & Ko, C. H. (2009). Symptoms of problematic cellular phone use, functional impairment and its association with depression among adolescents in Southern Taiwan. Journal of adolescence, 32(4), 863-873. [CrossRef]

- Di Matteo, D., Fotinos, K., Lokuge, S., Mason, G., Sternat, T., Katzman, M. A., & Rose, J. (2021). Automated screening for social anxiety, generalized anxiety, and depression from objective smartphone-collected data: cross-sectional study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(8), e28918. [CrossRef]

- Söderqvist, F., Carlberg, M., & Hardell, L. (2008). Use of wireless telephones and self-reported health symptoms: a population-based study among Swedish adolescents aged 15–19 years. Environmental Health, 7, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1986(23-28), 2.

- Van der Bijl, J. J., & Shortridge-Baggett, L. M. (2002). The theory and measurement of the self-efficacy construct. Self-efficacy in nursing: Research and measurement perspectives, 15(3), 189-20.

- Tiyuri, A., Saberi, B., Miri, M., Shahrestanaki, E., Bayat, B. B., & Salehiniya, H. (2018). Research self-efficacy and its relationship with academic performance in postgraduate students of Tehran University of Medical Sciences in 2016. Journal of education and health promotion, 7(1), 11. [CrossRef]

- Just, M. A., Carpenter, P. A., Keller, T. A., Emery, L., Zajac, H., & Thulborn, K. R. (2001). Interdependence of nonoverlapping cortical systems in dual cognitive tasks. Neuroimage, 14(2), 417-426. [CrossRef]

- Rawson, H. E., Bloomer, K., & Kendall, A. (1994). Stress, anxiety, depression, and physical illness in college students. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 155(3), 321-330. [CrossRef]

- Young, K. S. (2007). Cognitive behavior therapy with Internet addicts: treatment outcomes and implications. Cyberpsychology & behavior, 10(5), 671-679. [CrossRef]

- Rosen, L. D., Carrier, L. M., & Cheever, N. A. (2013). Facebook and texting made me do it: Media-induced task-switching while studying. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 948-958. [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A., Barkley, J. E., & Karpinski, A. C. (2014). The relationship between cell phone use, academic performance, anxiety, and satisfaction with life in college students. Computers in human behavior, 31, 343-350. [CrossRef]

- Litt, A., Reich, T., Maymin, S., & Shiv, B. (2011). Pressure and perverse flights to familiarity. Psychological Science, 22(4), 523-531. [CrossRef]

- Crum, A. J., Salovey, P., & Achor, S. (2013). Rethinking stress: the role of mindsets in determining the stress response. Journal of personality and social psychology, 104(4), 716. [CrossRef]

- Park, D., Yu, A., Metz, S. E., Tsukayama, E., Crum, A. J., & Duckworth, A. L. (2018). Beliefs about stress attenuate the relation among adverse life events, perceived distress, and self-control. Child development, 89(6), 2059-2069. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M., Lee, J. Y., Won, W. Y., Park, J. W., Min, J. A., Hahn, C., ... & Kim, D. J. (2013). Development and validation of a smartphone addiction scale (SAS). PloS one, 8(2), e56936. [CrossRef]

- Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1991). Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of abnormal psychology, 100(3), 316.

- Black, M. L., Curran, M. C., Golshan, S., Daly, R., Depp, C., Kelly, C., & Jeste, D. V. (2013). Summer research training for medical students: impact on research self-efficacy. Clinical and translational science, 6(6), 487-489. [CrossRef]

- Leung, L. (2008). Linking psychological attributes to addiction and improper use of the mobile phone among adolescents in Hong Kong. Journal of children and media, 2(2), 93-113. [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z., & Ye, B. (2014). Analyses of mediating effects: the development of methods and models. Advances in psychological Science, 22(5), 731. [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of applied psychology, 88(5), 879. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications.

- Zhao, X., Lynch Jr, J. G., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of consumer research, 37(2), 197-206.

- Andrews, S., Ellis, D. A., Shaw, H., & Piwek, L. (2015). Beyond self-report: Tools to compare estimated and real-world smartphone use. PloS one, 10(10), e0139004. [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2011). Online social networking and addiction—a review of the psychological literature. International journal of environmental research and public health, 8(9), 3528-3552. [CrossRef]

- Fırat, M. (2013). Multitasking or continuous partial attention: A critical bottleneck for digital natives. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 14(1), 266-272.

- Hawi, N. S., & Samaha, M. (2016). To excel or not to excel: Strong evidence on the adverse effect of smartphone addiction on academic performance. Computers & Education, 98, 81-89. [CrossRef]

- Uncapher, M. R., & Wagner, A. D. (2018). Minds and brains of media multitaskers: Current findings and future directions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(40), 9889-9896. [CrossRef]

- Samaha, M., & Hawi, N. S. (2016). Relationships among smartphone addiction, stress, academic performance, and satisfaction with life. Computers in human behavior, 57, 321-325.

- Liu, H., Novotný, J. S., & Váchová, L. (2022). The effect of mobile phone addiction on perceived stress and mediating role of ruminations: Evidence from Chinese and Czech university students. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1057544. [CrossRef]

- Roser, K., Schoeni, A., Foerster, M., & Röösli, M. (2016). Problematic mobile phone use of Swiss adolescents: is it linked with mental health or behaviour?. International journal of public health, 61, 307-315. [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology, 39(3), 281-291.

- Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success?. Psychological bulletin, 131(6), 803. [CrossRef]

- Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, M., & Tice, D. M. (1998). Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource?. Journal of personality and social psychology, 74(5), 1252-1265.

- Junco, R., & Cotten, S. R. (2012). No A 4 U: The relationship between multitasking and academic performance. Computers & Education, 59(2), 505-514. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A., Freeman, W. H., & Lightsey, R. (1999). Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 13(2), 158-166.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).