Submitted:

28 August 2024

Posted:

01 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Traditional African Vegetables (TAVs)

1.2. Value Chain Concept for Knowledge Translation across the TAVs Value Chain

1.3. Knowledge and Knowledge Translation across the TAVs Value Chain

1.4. Objective

1.5. Review Question

- -

- What evidence is available concerning TAV? (Type of evidence, how/where the evidence was created)

- -

- What is the focus of the evidence? (phase of value chain, attributes of TAVs investigated)

- -

- What knowledge translation components are covered in the literature? (creation, transfer, utilization)

- -

- What are the research gaps in relation to the TAVs’ knowledge translation across the value chain? (discussion)

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Identification and Data Sources

- Traditional African vegetables, African indigenous vegetables, Africa underutilised vegetables, African leafy vegetables

- Knowledge transfer, knowledge translation, knowledge management, tactic knowledge

- Value chain

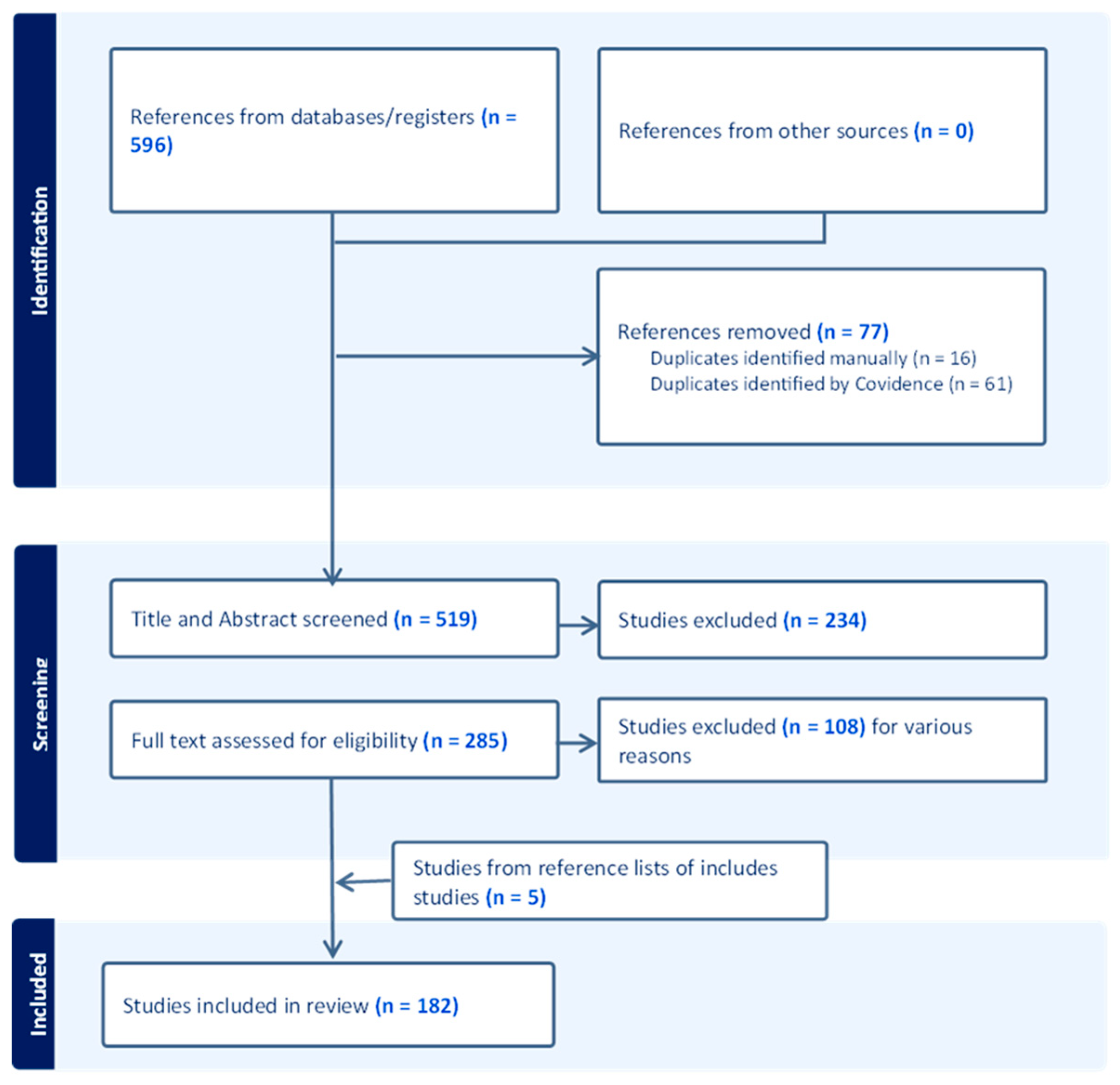

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. S Data Extraction, Synthesis, and Reporting

4. Results

4.1. Overview of Included Studies

4.2. What Is the Available Evidence? (TYPE of Evidence, How/Where the Evidence Was Created (Review Question 1)

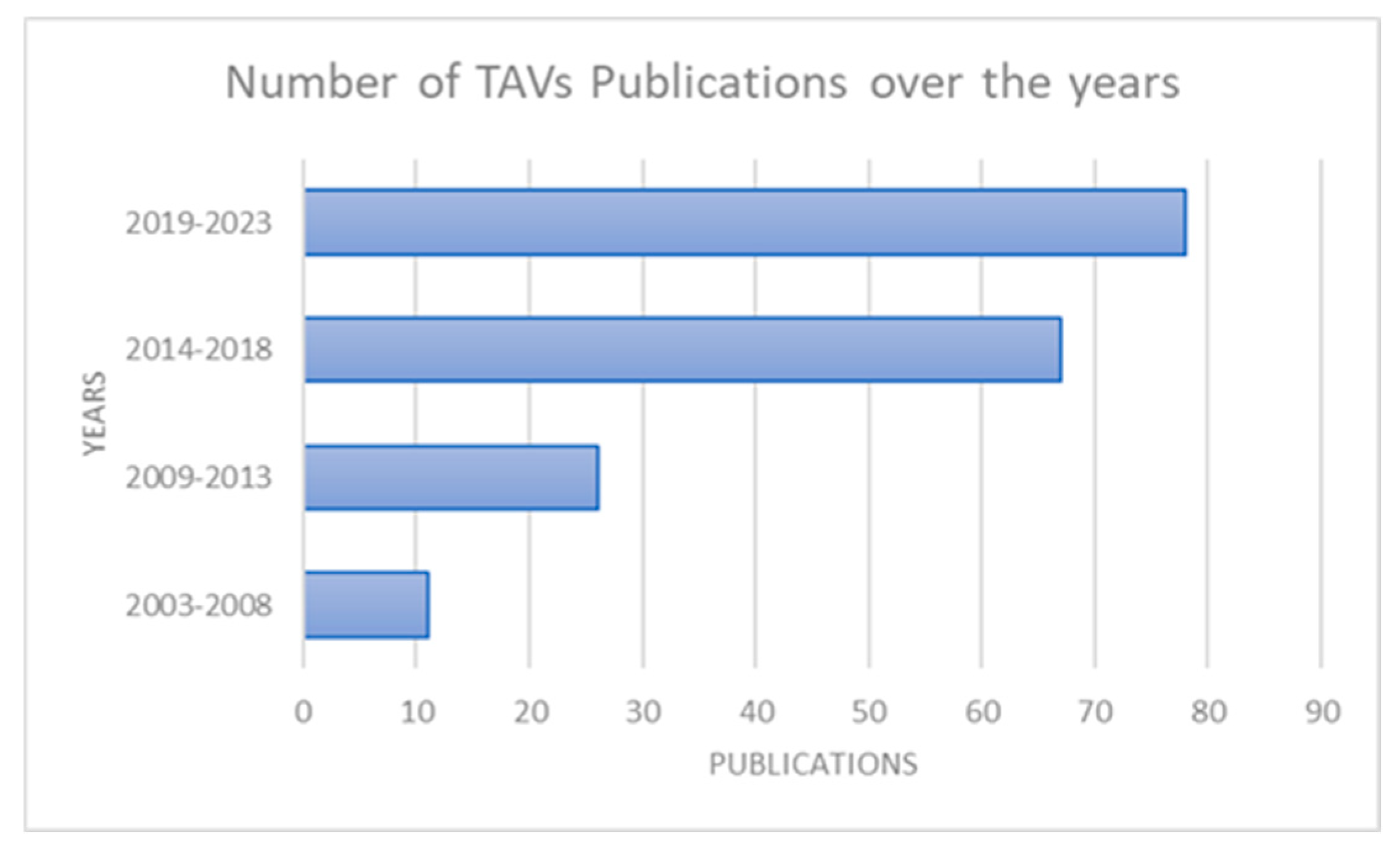

4.2.1. Distribution of TAVs Publications

4.3. What is the Focus of the Evidence? – Phase of Value Chain, Attributes of TAVs Investigated (Review Question 2)

4.3.1. Definition of Traditional African Vegetables

4.3.2. Traditional African Vegetables Mostly Studied

4.3.3. The Traditional African Vegetables Value Chain Components Studied

4.4. Knowledge Translation Components That Are Covered in the Literature

5. Discussion

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

- There is considerable amount of knowledge created about different aspects of TAVs particularly their genetic diversity and nutritional benefits

- Most of the research done on TAVs focuses on the production phase amongst other phases of the value chain, especially the demand and consumption phase.

- There is not much documentation of how this created knowledge is being transferred and utilised by various TAVs value chain actors

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

| Date final search conducted | Database / resource | Search terms / search string | Results | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 02/12/23 | Web of Science | Exact & Topic search | ((“Traditional African Vegetables” OR “African indigenous vegetables” OR “African leafy vegetables” OR “African Underutilized Vegetables”) | 199 | Exported to EndNote, Downloaded PDFs |

| 02/12/23 | Web of Science | Exact & Topic search | ((“Traditional African Vegetables” OR “African indigenous vegetables” OR “African leafy vegetables” OR “African Underutilized Vegetables”) AND (knowledge OR “knowledge transfer”) AND “value chain”) | 6 | Exported to EndNote, Downloaded PDFs |

| 02/12/23 | Web of Science | Exact & Topic search | ((“Traditional African Vegetables” OR “African indigenous vegetables” OR “African leafy vegetables” OR “African Underutilized Vegetables”) AND (“knowledge utilization”) | 0 | |

| 04/12/23 | Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY | (({Traditional African Vegetables} OR {African indigenous vegetables} OR {African leafy vegetables} OR {African Underutilized Vegetables}) AND (knowledge OR {knowledge translation} OR {knowledge management} OR {tacit knowledge} ) AND [128re] ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( EXACTKEYWORD , “African Indigenous Vegetables” ) ) | 9 | Exported to EndNote |

| 04/12/23 | Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY | (( {Traditional African Vegetables} OR {African indigenous vegetables} OR {African leafy vegetables} OR {African Underutilized Vegetables} ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( EXACTKEYWORD , “Vegetable” ) OR LIMIT-TO ( EXACTKEYWORD , “Vegetables” ) OR LIMIT-TO ( EXACTKEYWORD , “Human” ) OR LIMIT-TO ( EXACTKEYWORD , “Traditional African Vegetables” ) OR LIMIT-TO ( EXACTKEYWORD , “African indigenous vegetables” ) ) | 366 | Exported to EndNote |

| 04/12/23 | ABI/Inform | All fields | ((“Traditional African Vegetables” OR “African indigenous vegetables” OR “African leafy vegetables” OR “African Underutilized Vegetables”) AND (knowledge OR “knowledge translation” OR “knowledge management” OR “tacit knowledge”) AND “value chain”) | 16 | Most results out of scope |

| Extracted Item | Example | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Study aspects | ||

| Title of paper | Nutritional value of leafy vegetables of sub-Saharan Africa and their potential contribution to human health: A review | Text |

| Type of study | Journal article | Select one that applies |

| Author/s | ||

| Country in which study was conducted | More than one African country | Select one that applies |

| Year of Publication | 2010 | Text |

| Study design | Review | Select one that applies |

| Aim of study | To evaluate the nutritional value of TAVs plant species and their potential impact on the nutritional status of the people living in sub-Saharan Africa | Text |

| TAV aspects | ||

| Definition of TAVs | Not mentioned | Text |

| TAV crop of focus | All TAVs | Text |

| Part/section/activity of value chain studied/focused | Processing, Storage, Preparation, Consumption | Select all that applies |

| Attribute of TAV studied | Nutritional, health, medicinal properties of TAVs | Select all that applies |

| Aspect of Knowledge translation | Creation | Select All that applies(creation, transfer, utilization) |

| Other aspects | ||

| Main argument/finding/conclusion of study | African leafy vegetables (ALVs) contain significant levels of micronutrients that are essential for human health. The micronutrients are affected differently by processing, depending on the type of processing, as well as the type of vegetable species. Thermal processing of LVs reduces the level of ascorbic acid but enhances the bioavailability of vitamin A. The bioavailability of minerals such as iron and zinc from plant sources is low in the presence of antinutritional factors like phytates, while the presence of vitaminC and protein improves their efficacy. | Text |

| Study funding sources | Schlumberger Foundation and Third World Organization for Women in Science(TWOWS) | Text |

| Author | Definition of TAVs |

|---|---|

| [113] | Traditional leafy vegetables (TLVs), defined as those originally domesticated or cultivated in Africa for the last several centuries |

| [114] | According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization traditional vegetables are all categories of plants whose leaves, fruits or roots are acceptable and used as vegetables by urban and rural communities through custom, habit, and tradition |

| [115] | The word indigenous has been used in generic form to describe crop species, though not native to the area, that have been produced over years for the enhancement of high value of nutritious leafy vegetable. They have been part of the food systems in Nigeria and other SSA countries for generations |

| [116] | African indigenous leafy vegetables, also referred to as traditional leafy vegetables, are crops that grow wild or are cultivated and are gathered or harvested for food within a particular African ecosystem |

| [117] | ALVs are vegetables that are either native to the region, or were introduced to it a long time ago to evolve through natural processes or farmer selection, including both wild vegetables and ones traditionally cultivated by the inhabitants of a region |

| [103] | Traditional African vegetables include those native to Africa, as well as introduced vegetable crops that have been integrated into local food cultures and have become indigenized |

| [51] | AIVs include all plants that originate on the continent or have a long history of cultivation and domestication to African conditions and whose leaves, fruits, or roots are acceptable and used as vegetables through custom, habit, or tradition |

| [90] | TAVs are those whose natural habitat originated in Africa and have been integrated into cultures through natural or selective processes |

| [118] | African leafy vegetables (ALVs) are defined as plant species which are either genuinely native to a particular region, or which were introduced to that region for long enough to have evolved through natural processes or farmer selection |

| [60], | African indigenous vegetables (AIVs) are a diverse set of over 1000 different species that are either native to Africa or introduced vegetable crops that have been indigenized and integrated into local food cultures |

| [119] | “African Leafy Vegetables are defined as plant species which are either genuinely native to a particular region, or which were introduced to that region for long enough to have evolved through natural processes or farmer selection” |

| [21] | Plant species that are indigenous or naturalized to Africa, well adapted to, or selected for local conditions, whose plant parts are used as a vegetable, and whose modes of cultivation, collection, preparation, and consumption are deeply embedded in local cuisine, culture, folklore, and language |

| [120] | African indigenous vegetables (AIVs) are vegetable crops whose natural habitat originated in Africa |

| [121] | African indigenous leafy vegetables (AILVs) are part of the African indigenous vegetables (AIVs) whose natural habitat originated in Africa. Traditional African leafy vegetables that were introduced over a century ago and due to long use, have become part of the food culture in the continent |

| [122] | According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), ALVs are all categories of plants whose leaves are acceptable and used as vegetables by communities through custom, habit, and tradition |

| [123] | Traditional African Vegetables (TAV) are plant species that are indigenous or naturalized to Africa, well adapted to, or selected for local conditions, whose plant parts are used as a vegetable, and whose modes of cultivation, collection, preparation, and consumption are deeply embedded in local cuisine, culture, folklore, and language |

| [124] | AIVs are vegetables that originated or got established in Africa for many generations, and their leaves, young shoots, flowers, fruits, seeds, stems, tubers, or roots are consumed as vegetables |

| [40] | African leafy vegetables consist of all categories of plants whose leaves are acceptable and used as vegetables by rural and urban communities through tradition. |

| [125] | ALVs are plant species which are either genuinely native to a particular region, or which were introduced to that region for long enough to have evolved through natural processes or farmer selection |

| [126] | AIVs include all plants that originate on the continent or have a long history of cultivation and domestication to African conditions and whose leaves, fruits, or roots are acceptable and used as vegetables through custom, habit, or tradition |

| [127] | AIVs refer to vegetable species or varieties genuinely native to Africa or that have been integrated and incorporated into local food cultures and farming systems over a period of time |

| [80], | AIVs are vegetables that either originated or have a long history of cultivation and domestication in Africa and are locally important for economic and human nutrition but have yet to gain regional and global recognition as a major commodity such as carrots or corn |

References

- Dukhi, N. Global Prevalence of Malnutrition: Evidence from Literature. 2020.

- Micha, D.R. 2021 Global Nutrition Report: The state of global nutrition; Development Initiatives Poverty Research Ltd: Bristol, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Malnutrition. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition (accessed on 25 March).

- The triple burden of malnutrition. Nature food 2023, 4, 925–925. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, A.K.; Dake, F.A. Profiling household double and triple burden of malnutrition in sub-Saharan Africa: prevalence and influencing household factors. Public Health Nutrition 2022, 25, 1563–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudogo, C.M. Vulnerability of urban poor women and children to the triple. Burden of malnutrition: A scoping review of the sub-Saharan Africa Environment. Glob. J. Med. Res. Nutr. Food Sci 2017, 17, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ahinkorah, B.O.; Amadu, I.; Seidu, A.-A.; Okyere, J.; Duku, E.; Hagan, J.E.; Budu, E.; Archer, A.G.; Yaya, S. Prevalence and Factors Associated with the Triple Burden of Malnutrition among Mother-Child Pairs in Sub-Saharan Africa. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health (MoH) [Tanzania Mainland], M.o.H.M.Z., National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), Office of the Chief Government Statistician (OCGS), and ICF. Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey 2022 Key Indicators Report. 2023.

- URT. Tanzania National Nutrition Survey (TNNS). 2018.

- Kennedy, G.; Ballard, T.; Dop, M.C. Guidelines for measuring household and individual dietary diversity; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: 2011.

- Gonete, K.A.; Tariku, A.; Wami, S.D.; Akalu, T.Y. Dietary diversity practice and associated factors among adolescent girls in Dembia district, northwest Ethiopia, 2017. Public Health Reviews 2020, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochieng, J.; Afari-Sefa, V.; Lukumay, P.J.; Dubois, T. Determinants of dietary diversity and the potential role of men in improving household nutrition in Tanzania. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0189022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, I.; Baldi, G.; Kiess, L.; Pee, d.S. The “Fill the Nutrient Gap” analysis: An approach to strengthen nutrition situation analysis and decision making towards multisectoral policies and systems change. Matern Child Nutr 2019, 15, e12793–n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keding, G.B.; Msuya, J.M.; Maass, B.L.; Krawinkel, M.B. Relating dietary diversity and food variety scores to vegetable production and socio-economic status of women in rural Tanzania. Food Security 2012, 4, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minja, E.G.; Swai, J.K.; Mponzi, W.; Ngowo, H.; Okumu, F.; Gerber, M.; Pühse, U.; Long, K.Z.; Utzinger, J.; Lang, C.; et al. Dietary diversity among households living in Kilombero district, in Morogoro region, South-Eastern Tanzania. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2021, 5, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochieng, J.; Afari-Sefa, V.; Lukumay, P.J.; Dubois, T. Determinants of dietary diversity and the potential role of men in improving household nutrition in Tanzania. PLoS ONE 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamis, A.G.; Mwanri, A.W.; Ntwenya, J.E.; Kreppel, K. The influence of dietary diversity on the nutritional status of children between 6 and 23 months of age in Tanzania. BMC Pediatr 2019, 19, 518–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heri, R.; Malqvist, M.; Yahya-Malima, K.I.; Mselle, L.T. Dietary diversity and associated factors among women attending antenatal clinics in the coast region of Tanzania. BMC Nutrition 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mensah, D.O.; Nunes, A.R.; Bockarie, T.; Lillywhite, R.; Oyebode, O. Meat, fruit, and vegetable consumption in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Nutrition Reviews 2020, 79, 651–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrimi, E.C.; Palmeirim, M.S.; Minja, E.G.; Long, K.Z.; Keiser, J. Malnutrition, anemia, micronutrient deficiency and parasitic infections among schoolchildren in rural Tanzania. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2022, 16, e0010261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Towns, A.M.; Shackleton, C. Traditional, Indigenous, or Leafy? A Definition, Typology, and Way Forward for African Vegetables. Economic Botany 2018, 72, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afari-Sefa, V.; Rajendran, S.; Kessy, R.; Karanja, D.; Musebe, R.; Samali, S.; Makaranga, M. Impact of nutritional perceptions of traditional African vegetables on farm household production decisions: a case study of smallholders in Tanzania. Experimental Agriculture 2016, 52, 300–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bbenkele, H.C. An Exploration of the Growing of Indigenous African Vegetables in Ndeke, Kitwe (Zambia). University of Johannesburg (South Africa), 2016.

- Gowele, V.; Kirschmann, C.; Kinabo, J.; Frank, J.; Biesalski, H.; Rybak, C.; Stuetz, W. Micronutrient profile of Indigenous Leafy Vegetables from rural areas of Morogoro and Dodoma regions in Tanzania; 2017.

- Lotter, D.; Marshall, M.; Weller, S.; Mugisha, A. African indigenous and traditional vegetables in Tanzania: Production, post-harvest management, and marketing. African Crop Science Journal 2014, 22, 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Walt, R. Traditional African vegetables can reduce food insecurity and disease in rural communities: application of indigenous knowledge systems. South Africa Rural Development Quarterly 2004, 2, 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chacha, J.S.; Laswai, H.S. Micronutrients potential of underutilized vegetables and their role in fighting hidden hunger. International Journal of Food Science 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navya, B.; Nagnur, S. Purchasing pattern of exotic vegetables by consumers. 2020.

- Mwadzingeni, L.; Afari-Sefa, V.; Shimelis, H.; N’Danikou, S.; Figlan, S.; Depenbusch, L.; Shayanowako, A.I.T.; Chagomoka, T.; Mushayi, M.; Schreinemachers, P.; et al. Unpacking the value of traditional African vegetables for food and nutrition security. Food Security 2021, 13, 1215–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedling, G.; Swai, I.; Virchow, D. Traditional versus exotic vegetables in Tanzania. New Crops and Uses: Their role in a rapidly changing world 2008, 150.

- Collins, R.; Dent, B.; Bonney, L. A guide to value-chain analysis and development for overseas development assistance projects. A guide to value-chain analysis and development for overseas development assistance projects. 2016.

- Benjamin, D.; Ray, C. A manual for agribusiness value chain analysis in developing countries, 1 ed.; CABI: UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Watabaji, M.D.; Molnar, A.; Weaver, R.D.; Dora, M.K.; Gellynck, X. Information sharing and its integrative role. British Food Journal 2016, 118, 3012–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teese, J.; Currey, P.; Somogyi, S. Strategic information flows within an Australian vegetable value chain. 2019.

- Zagzebski, L. What is knowledge? The Blackwell guide to epistemology 2017, 92–116. [Google Scholar]

- Straus, S.E.; Tetroe, J.; Graham, I.D. Introduction knowledge translation: what it is and what it isn’t. Knowledge translation in health care 2013, 1-13.

- Straus, S.E.; Tetroe, J.; Graham, I. Defining knowledge translation. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2009, 181, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetroe, J. Knowledge translation at the Canadian Institutes of Health Research: a primer. Focus Technical Brief 2007, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rajendrana, S.; Afari-Sefa, V.; Karanja, D.K.; Musebe, R.; Romney, D.; Makaranga, M.A.; Samali, S.; Kessy, R.F. Farmerled seed enterprise initiatives to access certified seed for traditional African vegetables and its effect on incomes in Tanzania. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 2016, 19, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Shayanowako, A.I.T.; Morrissey, O.; Tanzi, A.; Muchuweti, M.; Mendiondo, G.M.; Mayes, S.; Modi, A.T.; Mabhaudhi, T. African Leafy Vegetables for Improved Human Nutrition and Food System Resilience in Southern Africa: A Scoping Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olugbade, Y.K.; Oluwasola, O.; Ayanwale, A.B.; Oyedele, D.J. Information Use for Marketing Efficiency of Underutilized Indigenous Vegetable. International journal of vegetable science 2019, 25, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achigan-Dako, E.G.; Sogbohossou, O.E.; Maundu, P. Current knowledge on Amaranthus spp. : research avenues for improved nutritional value and yield in leafy amaranths in sub-Saharan Africa. Euphytica 2014, 197, 303–317. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Stewart, L.; Shekelle, P. All in the family: systematic reviews, rapid reviews, scoping reviews, realist reviews, and more. Systematic reviews 2015, 4, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babineau, J. Product Review: Covidence (Systematic Review Software). The Journal of the Canadian Health Libraries Association = Journal de l’Association des Bibliothèques de la Santé du Canada 2014, 35, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellermeyer, L.; Harnke, B.; Knight, S. COVIDENCE AND RAYYAN. Journal of the Medical Library Association 2018, 106, 580–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Implement 2021, 19, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacha, J.S.; Laswai, H.S. Traditional Practices and Consumer Habits regarding Consumption of Underutilised Vegetables in Kilimanjaro and Morogoro Regions, Tanzania. International Journal of Food Science 2020, 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gido, E.O.; Ayuya, O.I.; Owuor, G.; Bokelmann, W. Consumption intensity of leafy African indigenous vegetables: towards enhancing nutritional security in rural and urban dwellers in Kenya. Agricultural and Food Economics 2017, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansiime, M.K.; Ochieng, J.; Kessy, R.; Karanja, D.; Romney, D.; Afari-Sefa, V. Changing knowledge and perceptions of African indigenous vegetables: the role of community-based nutritional outreach. Development in Practice 2018, 28, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochieng, J.; Afari-Sefa, V.; Karanja, D.; Kessy, R.; Rajendran, S.; Samali, S. How promoting consumption of traditional African vegetables affects household nutrition security in Tanzania. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 2018, 33, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, K. Indigenous vegetables in Tanzania: Significance and prospects; AVRDC-WorldVegetableCenter, 2004; Volume 600. [Google Scholar]

- Mampholo, B.M.; Sivakumar, D.; Thompson, A.K. Maintaining overall quality of fresh traditional leafy vegetables of Southern Africa during the postharvest chain. Food Reviews International 2016, 32, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, G.; Mndiga, H.; Maass, B. Production and consumption issues of traditional vegetables in Tanzania from the farmers’ point of view. Proceedings of rural poverty reduction through research for development 2004, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Aubree, P.; Brunori, G.; Dvortsin, L.; Galli, F.; Gromasheva, O.; Hoekstra, F.; Karner, S.; Lutz, J.; Piccon, L.; Prior, A. Short food supply chains as drivers of sustainable development; Laboratorio di studi rurali Sismondi: 2013.

- Jarzebowski, S.; Bourlakis, M.; Bezat-Jarzebowska, A. Short food supply chains (SFSC) as local and sustainable systems. Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland) 2020, 12, 4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoilova, T. Diversity, conservation and use of traditional African vegetables. In Proceedings of the Acta Horticulturae; 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran, S.; Afari-Sefa, V.; Karanja, D.K.; Musebe, R.; Romney, D.; Makaranga, M.A.; Samali, S.; Kessy, R.F. Farmer-led seed enterprise initiatives to access certified seed for traditional African vegetables and its effect on incomes in Tanzania. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 2016, 19, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pincus, L.; Croft, M.; Roothaert, R.; Dubois, T. African Indigenous Vegetable Seed Systems in Western Kenya. Economic Botany 2018, 72, 380–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afari-Sefa, V.; Chagomoka, T.; Karanja, D.K.; Njeru, E.; Samali, S.; Katunzi, A.; Mtwaenzi, H.; Kimenye, L. Private contracting versus community seed production systems: Experiences from farmer-led seed enterprise development of indigenous vegetables in Tanzania. In Proceedings of the Acta Horticulturae; 2013; pp. 671–680. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasulu, R.; Victor, A.-S.; Daniel, K.K.; Richard, M.; Dannie, R.; Magesa, A.M.; Silivesta, S.; Radegunda, F.K. Technical efficiency of traditional African vegetable production: A case study of smallholders in Tanzania. Journal of development and agricultural economics 2015, 7, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwene, B.; Neugart, S.; Baldermann, S.; Ravi, B.; Schreiner, M. Intercropping Induces Changes in Specific Secondary Metabolite Concentration in Ethiopian Kale (<i>Brassica carinata</i>) and African Nightshade (<i>Solanum scabrum</i>) under Controlled Conditions. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogo, E.O.; Förster, N.; Dannehl, D.; Frommherz, L.; Trierweiler, B.; Opiyo, A.M.; Ulrichs, C.; Huyskens-Keil, S. Postharvest UV-C application to improve health promoting secondary plant compound pattern in vegetable amaranth. Innovative Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2018, 45, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van’t Hag, L.; Danthe, J.; Handschin, S.; Mutuli, G.P.; Mbuge, D.; Mezzenga, R. Drying of African leafy vegetables for their effective preservation: the difference in moisture sorption isotherms explained by their microstructure. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misci, C.; Taskin, E.; Dall’Asta, M.; Fontanella, M.C.; Bandini, F.; Imathiu, S.; Sila, D.; Bertuzzi, T.; Cocconcelli, P.S.; Puglisi, E. Fermentation as a tool for increasing food security and nutritional quality of indigenous African leafy vegetables: the case of Cucurbita sp. Food Microbiol. 2021, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irungu, C.; Mburu, J.; Maundu, P.; Grum, M.; Hoeschle-Zeledon, I. Marketing of African leafy vegetables in Nairobi and its implications for on-farm conservation of biodiversity. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Indigenous Vegetables and Legumes Prospectus for Fighting Poverty, Hunger and Malnutrition, Hyderabad, INDIA, Dec 12-15 2006; p. 197. [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam, S.; Govindasamy, R.; Simon, J.E.; Van Wyk, E.; Ozkan, B. Market outlet choices for African Indigenous Vegetables (AIVs): a socio-economic analysis of farmers in Zambia. Agricultural and Food Economics 2022, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thovhogi, F.; Gwata, E.T.; McHau, G.R.A.; Ntutshelo, N. Perceptions of end-users in Limpopo Province (South Africa) about the Spider plant (Cleome gynandra L. ). Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 2021, 68, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, S.M.; Serem, J.C.; Bester, M.J.; Mavumengwana, V.; Kayitesi, E. The impact of boiling and in vitro human digestion of Solanum nigrum complex (Black nightshade) on phenolic compounds bioactivity and bioaccessibility. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyo, S.M.; Mavumengwana, V.; Kayitesi, E. Effects of cooking and drying on phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of African green leafy vegetables. Food Reviews International 2018, 34, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, S.M.; Serem, J.C.; Bester, M.J.; Mavumengwana, V.; Kayitesi, E. Influence of boiling and subsequent phases of digestion on the phenolic content, bioaccessibility, and bioactivity of Bidens pilosa (Blackjack) leafy vegetable. Food Chemistry 2020, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwema, C.; Crewett, W. Social Networks and Commercialisation of African Indigenous Vegetables in Kenya: A Cragg’s Double Hurdle Approach. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2019, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwema, C.M.; Crewett, W.; Lagat, J. Smallholders’ Personal Networks in Access to Agricultural Markets: A Case of African Leafy Vegetables Commercialisation in Kenya. J. Dev. Stud. 2021, 57, 2063–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansiime, M.K.; Bundi, M.; Nicodemus, J.; Ochieng, J.; Marandu, D.; Njau, S.S.; Kessy, R.F.; Williams, F.; Karanja, D.; Tambo, J.A.; et al. Assessing sustainability factors of farmer seed production: a case of the Good Seed Initiative project in Tanzania. Agric. Food Secur. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntawuhunga, D.; Affognon, H.D.; Fiaboe, K.K.M.; Abukutsa-Onyango, M.O.; Turoop, L.; Muriithi, B.W. Farmers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) on production of African indigenous vegetables in Kenya. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2020, 40, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivas, J.; Kim, M.K.; Takagi, C.; Kirimi, L. Adopting African Indigenous Vegetables: A Dynamic Panel Analysis of Smallholders in Kenya. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2022, 48, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, S.; Afari-Sefa, V.; Kessy, R.F.; Karanja, K.D.; Musebe, R.; Samali, S.; Makaranga, M. Technical efficiency of smallholders’ traditional African vegetable production in Tanzania: a stochastic frontier approach. In Proceedings of the 29th International Horticultural Congress (IHC2014), Brisbane, AUSTRALIA, Aug 17-22 2014; pp. 241–249. [Google Scholar]

- Keding, G.B.; Gramzow, A.; Ochieng, J.; Laizer, A.; Muchoki, C.; Onyango, C.; Hanson, P.; Yang, R.Y. Nutrition integrated agricultural extension - a case study in Western Kenya. Health Promot. Int. 2022, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, E.V.; Odendo, M.; Maiyo, N.; Govindasamy, R.; Morin, X.K.; Simon, J.E.; Hoffman, D.J. An evaluation of nutrition, culinary, and production interventions using African indigenous vegetables on nutrition security among smallholder farmers in Western Kenya. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abukutsa-Onyango, M.O. The Role of Universities in Promoting Underutilized Crops: the Case of Maseno University, Kenya. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Underutilized Plants for Food Security, Nutrition, Income and Sustainable Development, Arusha, TANZANIA, Jan 31 2009; pp. 155–162. [Google Scholar]

- Muhanji, G.; Roothaert, R.L.; Webo, C.; Stanley, M. African indigenous vegetable enterprises and market access for small-scale farmers in East Africa. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 2011, 9, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokelmann, W.; Ferenczi, Z.; Gevorgyan, E. Improving food and nutritional security in East Africa through African indigenous vegetables: a case study of the horticultural innovation system in Kenya. In Proceedings of the 18th International Symposium on Horticultural Economics and Management, Alnarp, SWEDEN, May 31-Jun 03 2015; pp. 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ochieng, J.; Schreinemachers, P.; Ogada, M.; Dinssa, F.F.; Barnos, W.; Mndiga, H. Adoption of improved amaranth varieties and good agricultural practices in East Africa. Land Use Policy 2019, 83, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokelmann, W.; Huyskens-Keil, S.; Ferenczi, Z.; Stöber, S. The Role of Indigenous Vegetables to Improve Food and Nutrition Security: Experiences From the Project HORTINLEA in Kenya (2014–2018). Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbugua, G.W.; Gitonga, L.; Ndungu, B.; Gatambia, E.; Manyeki, L.; Karoga, J. African Indigenous Vegetables and Farmer-Preferences in Central Kenya. In Proceedings of the 1st All African Horticultural Congress, Nairobi, KENYA, Aug 31-Sep 03 2009; pp. 479–485. [Google Scholar]

- Ochieng, J.; Afari-Sefa, V.; Karanja, D.; Rajendran, S.; Silvest, S.; Kessy, R. Promoting consumption of traditional African vegetables and its effect on food and nutrition security in Tanzania; 2016.

- Van der Hoeven, M.; Osei, J.; Greeff, M.; Kruger, A.; Faber, M.; Smuts, C.M. Indigenous and traditional plants: South African parents’ knowledge, perceptions and uses and their children’s sensory acceptance. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2013, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweba, T.P.; Mearns, M.A. Conserving indigenous knowledge as the key to the current and future use of traditional vegetables. International Journal of Information Management 2011, 31, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessy, R.F.; Ochieng, J.; Afari-Sefa, V.; Chagomoka, T.; Nenguwo, N. Solar-Dried Traditional African Vegetables in Rural Tanzania: Awareness, Perceptions, and Factors Affecting Purchase Decisions. Economic Botany 2018, 72, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogbohossou, O.E.D.; Achigan-Dako, E.G.; Assogba Komlan, F.; Ahanchede, A. Diversity and Differential Utilization of Amaranthus spp. along the Urban-Rural Continuum of Southern Benin. Economic Botany 2015, 69, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipungahelo, M.S. Knowledge sharing strategies on traditional vegetables for supporting food security in Kilosa District, Tanzania. Library Review 2015. [CrossRef]

- Aberman, N.-L.; Gelli, A.; Agandin, J.; Kufoalor, D.; Donovan, J. Putting consumers first in food systems analysis: identifying interventions to improve diets in rural Ghana. Food Security 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelli, A.; Hawkes, C.; Donovan, J.; Harris, J.; Allen, S.L.; De Brauw, A.; Henson, S.; Johnson, N.; Garrett, J.; Ryckembusch, D. Value chains and nutrition: A framework to support the identification, design, and evaluation of interventions. 2015.

- Padulosi, S.; Amaya, K.; Jäger, M.; Gotor, E.; Rojas, W.; Valdivia, R. A Holistic Approach to Enhance the Use of Neglected and Underutilized Species: The Case of Andean Grains in Bolivia and Peru. Sustainability 2014, 6, 1283–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, M.; Van Jaarsveld, P.; Wenhold, F.; Van Rensburg, J. African leafy vegetables consumed by households in the Limpopo and KwaZulu-Natal provinces in South Africa. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2010, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zonneveld, M.; Kindt, R.; Solberg, S.Ø.; N’Danikou, S.; Dawson, I.K. Diversity and conservation of traditional African vegetables: Priorities for action. Divers. Distrib. 2021, 27, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinssa, F.; Hanson, P.; Dubois, T.; Tenkouano, A.; Stoilova, T.; Hughes, J.d.A.; Keatinge, J. AVRDC—The World Vegetable Center’s women-oriented improvement and development strategy for traditional African vegetables in sub-Saharan Africa. European Journal of Horticultural Science 2016, 81, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.Y.; Fischer, S.; Hanson, P.M.; Keatinge, J.D.H. Increasing micronutrient availability from food in sub-saharan africa with indigenous vegetables. In Proceedings of the ACS Symposium Series; 2013; pp. 231–254. [Google Scholar]

- Uusiku, N.P.; Oelofse, A.; Duodu, K.G.; Bester, M.J.; Faber, M. Nutritional value of leafy vegetables of sub-Saharan Africa and their potential contribution to human health: A review. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2010, 23, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Jaarsveld, P.; Faber, M.; van Heerden, I.; Wenhold, F.; van Rensburg, W.J.; van Averbeke, W. Nutrient content of eight African leafy vegetables and their potential contribution to dietary reference intakes. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2014, 33, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayanowako, A.I.T.; Morrissey, O.; Tanzi, A.; Muchuweti, M.; Mendiondo, G.M.; Mayes, S.; Modi, A.T.; Mabhaudhi, T. African Leafy Vegetables for Improved Human Nutrition and Food System Resilience in Southern Africa: A Scoping Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinssa, F.F.; Hanson, P.; Dubois, T.; Tenkouano, A.; Stoilova, T.; Hughes, J.D.; Keatinge, J.D.H. AVRDC - The World Vegetable Center’s women-oriented improvement and development strategy for traditional African vegetables in sub-Saharan Africa. European Journal of Horticultural Science 2016, 81, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiweshe, M.K.; Bhatasara, S. Women in Agriculture in Contemporary Africa. In The Palgrave Handbook of African Women’s Studies; Yacob-Haliso, O., Falola, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 1601–1618. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, B.; Babus, V.S. Role of women in agriculture. Int J Applied Res 2018, 4, 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Doss, C.; Meinzen-Dick, R.; Quisumbing, A.; Theis, S. Women in agriculture: Four myths. Global food security 2018, 16, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyalo, P.O. Women and agriculture in rural Kenya: role in agricultural production. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 2019, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ochieng, J.; Afari-Sefa, V.; Karanja, D.; Kessy, R.; Rajendran, S.; Samali, S. How promoting consumption of traditional African vegetables affects household nutrition security in Tanzania. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 2018, 33, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzarri, C.; Nico, G. Sex-disaggregated agricultural extension and weather variability in Africa south of the Sahara. World Development 2022, 155, 105897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oelke, N.D.; Lima, M.A.D.d.S.; Acosta, A.M. Knowledge translation: translating research into policy and practice. Revista gaucha de enfermagem 2015, 36, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slabbert, M.M.; van Rensburg, W.S.J.; Spreeth, M.H. Screening for Improved Drought Tolerance in the Mutant Germplasm of African Leafy Vegetables: Amaranth (Amaranthus tricolor) and Cowpea (Vigna inguiculata). In Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on Underutilized Plant Species - Crops for the Future - Beyond Food Security, Kuala Lumpur, MALAYSIA, Jun 27-Jul 01 2011; pp. 477–484. [Google Scholar]

- CGIAR. Tackling diet challenges in Tanzania: The FRESH end-to-end approach. Available online: https://www.cgiar.org/news-events/news/tackling-tanzanias-diet-challenges-the-fresh-end-to-end-approach/ (accessed on 23/04/2024).

- Gockowski, J.; Mbazo’o, J.; Mbah, G.; Fouda Moulende, T. African traditional leafy vegetables and the urban and peri-urban poor. Food Policy 2003, 28, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applequist, W. African Indigenous Vegetables in Urban Agriculture. Economic Botany 2010, 64, 180–181. [Google Scholar]

- Agbugba, I.K.; Okechukwu, F.O.; Solomon, R.J. Challenges and strategies for improving the marketing of indigenous leafy vegetables in nigeria. J. Home Econ. Res. 2011, 15, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Seeiso, M.; Materechera, S.A. Effect of phosphorus fertilizer and leaf cutting technique on biomass yield and crude protein content of two African indigenous leafy vegetables. Asia Life Sci. 2013, 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- van der Hoeven, M.; Osei, J.; Greeff, M.; Kruger, A.; Faber, M.; Smuts, C.M. Indigenous and traditional plants: South African parents’ knowledge, perceptions and uses and their children’s sensory acceptance. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2013, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maseko, I.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Tesfay, S.; Araya, H.T.; Fezzehazion, M.; Du Plooy, C.P. African Leafy Vegetables: A Review of Status, Production and Utilization in South Africa. Sustainability 2018, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senyolo, G.M.; Wale, E.; Ortmann, G.F. Analysing the value chain for African leafy vegetables in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2018, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, O.B.; Gor, C.O.; Okuro, S.O.; Omanga, P.A.; Bokelmann, W. The African Indigenous Vegetables Value Chain Governance in Kenya. Studies in Agricultural Economics 2019, 121, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehayem-Kamadjeu, A.; Okonda, J. X-ray fluorescence analysis of selected micronutrients in ten african indigenous leafy vegetables cultivated in Nairobi, Kenya. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2019, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndinya, C.A. The Genetic Diversity of Popular African Leafy Vegetables in Western Kenya. In Genetic Diversity in Horticultural Plants; Nandwani, D., Ed.; Sustainable Development and Biodiversity; Springer International Publishing Ag: Cham, 2019; Volume 22, pp. 127–159. [Google Scholar]

- Ayenan, M.A.T.; Aglinglo, L.A.; Zohoungbogbo, H.P.F.; N’Danikou, S.; Honfoga, J.; Dinssa, F.F.; Hanson, P.; Afari-Sefa, V. Seed Systems of Traditional African Vegetables in Eastern Africa: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2021, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irakoze, M.L.; Wafula, E.N.; Owaga, E. Potential Role of African Fermented Indigenous Vegetables in Maternal and Child Nutrition in Sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Food Science 2021, 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, O.C.; Babalola, O.O. Amaranth production and consumption in South Africa: the challenges of sustainability for food and nutrition security. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 2022, 20, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elolu, S.; Byarugaba, R.; Opiyo, A.M.; Nakimbugwe, D.; Mithöfer, D.; Huyskens-Keil, S. Improving nutrition-sensitive value chains of African indigenous vegetables: current trends in postharvest management and processing. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2023, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodzwa, J.J.; Madamombe, G.; Masvaya, E.N.; Nyamangara, J. Optimization of African indigenous vegetables production in sub Saharan Africa: a review. CABI Agriculture Biosci. 2023, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PORTER’S, V.C.M. What Is Value Chain. 1985.

| PCC | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | All TAVs (leafy only) | Non-leafy TAVs |

| Country or location specific TAVs (within Africa), common TAVs | Traditional/indigenous fruits | |

| Concept | From Input supply to Consumption. All value chain activities, in English language | Non-English language |

| Context | African continent. Studies conducted outside Africa but focusing on TAVs for Africa | Studies focusing on non-African countries |

| TAV attribute | Number of African nightshade studies | Number of Amaranth studies |

|---|---|---|

| Nutritional properties | 12 | 9 |

| Medicinal properties | 1 | 1 |

| Genetic diversity | 5 | 10 |

| Drought and pests and diseases tolerance and management | 0 | 5 |

| post-harvest handling and their impact on their nutritional properties | 6 | 2 |

| Yield | 0 | 5 |

| Consumption patterns across African countries | 0 | 3 |

| TAVs value chain phase | Focus of included studies | Number of studies |

| Pre-production | Genetic diversity of TAVs, breeding, variety testing, selection, and conservation of genetic resources at the gene banks for future breeding | 16 |

| Input supply | Seed production and supply systems in various countries. Challenges of availability of certified seeds, importance of farmer involvement in seed production through contraction by private and public seed agencies and farmer-led Quality Declared Seeds (QDS) production | 12 |

| Production/growing | Various production systems of TAVs, home gardening of TAVs, farmer preferences on production of TAVs, effects of various production systems on TAVs nutritional content. Water and fertilizer management for optimizing yield and nutritional traits of TAVs. | 66 |

| Post-harvest handling | Analysis of nutritional and economic losses from harvesting to marketing, various processing methods like boiling, sun-drying, fermenting and their impact on nutritional content and medicinal traits of TAVs, improving shelf life and various storage techniques to preserve nutrients | 16 |

| Marketing (wholesale/retail) | Consumer demand for TAVs, consumers’ willingness to pay premium for TAVs, social networks and commercialization of TAVs, policies governing marketing, improving marketing of TAVs (challenges and opportunities), TAVs farmers market competitiveness and market outlets choices for TAVs consumers | 15 |

| Consumption patterns | Various TAVs consumed and consumption patterns in different locations across Africa. Factors influencing consumer preferences for particular species of TAVs and | 12 |

| Whole chain | Analyzing the TAVs value chains to identify various actors and their roles for potential to alleviating poverty through commercialization and market linkages, contributing to better nutrition through increased consumption, TAVs value chain governance, various strategies to promote TAVs. | 15 |

| KT component | Synopsis of publication | Publication author |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge transfer | Social networks facilitate information sharing and enable commercialization of TAVs. Farmers with stronger social connections extending outside the village that they talk to have reported to sell more TAVs | [73,74] |

| Knowledge transfer/utilization | TAVs demand was stimulated by nutritional awareness campaigns as well as contributing to increased QDS seeds production by farmers in collaboration with formal seed sector | [75] |

| Knowledge transfer | Strengthening the existing cluster farming and stronger farmer groups can foster knowledge transfer to enhance technical efficiencies | [78] |

| Knowledge transfer/utilization | Use of community nutritional outreach programs and integrating nutrition communication in agricultural extension services is effective in transferring knowledge of TAVs and their benefits. To combine the outreach and extension program with provision of seed kits increase the utilization of the TAVs knowledge received hence improve consumption of TAVs | [51,79] |

| Knowledge transfer/utilization | Despite the seasonal differences causing unfavorable weather conditions, the households that received nutrition and culinary intervention (NCI) plus production interventions (PI) increase both production and consumption of TAVs | [80] |

| Knowledge creation/ transfer/utilization | The paper Showcase how universities and other research institutes can play a role in not only creating new knowledge through research, but also transferring the knowledge through collaboration with other stakeholders like farmers, policy makers, input suppliers and motivate utilization of knowledge through demonstration plots with farmers, providing seed kits and community outreach programs to promote TAVs. Multidisciplinary projects with research components are important avenues to the creation, transferring and utilization of TAVs knowledge | [81,82,83,84,85] |

| Knowledge transfer/utilization | The transfer and utilization of TAVs knowledge is challenged by lack of knowledge of various aspects like seed production skills, production systems, pos-harvest processing and preserving. Nutrition education and other strategies applied in communities have shown to impart new knowledge to households resulted in producing and consuming more TAVs | [52,86,87] |

| Knowledge creation/ transfer/utilization | There is vast traditional knowledge among the elderly population in communities, but there is limited strategies to transfer this knowledge to the younger generation. This was revealed by the lack of knowledge about various aspects of TAVs by the younger generation, hence decreased utilization of TAVs. When this knowledge was reported to be passed on to younger generations, there has been an increase in knowledge and utilization of TAVs | [88,89,90,91] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).