Submitted:

31 August 2024

Posted:

02 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2.2. Sample Size Calculation

2.3. Test Methods

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Sample

3.2. Main Results

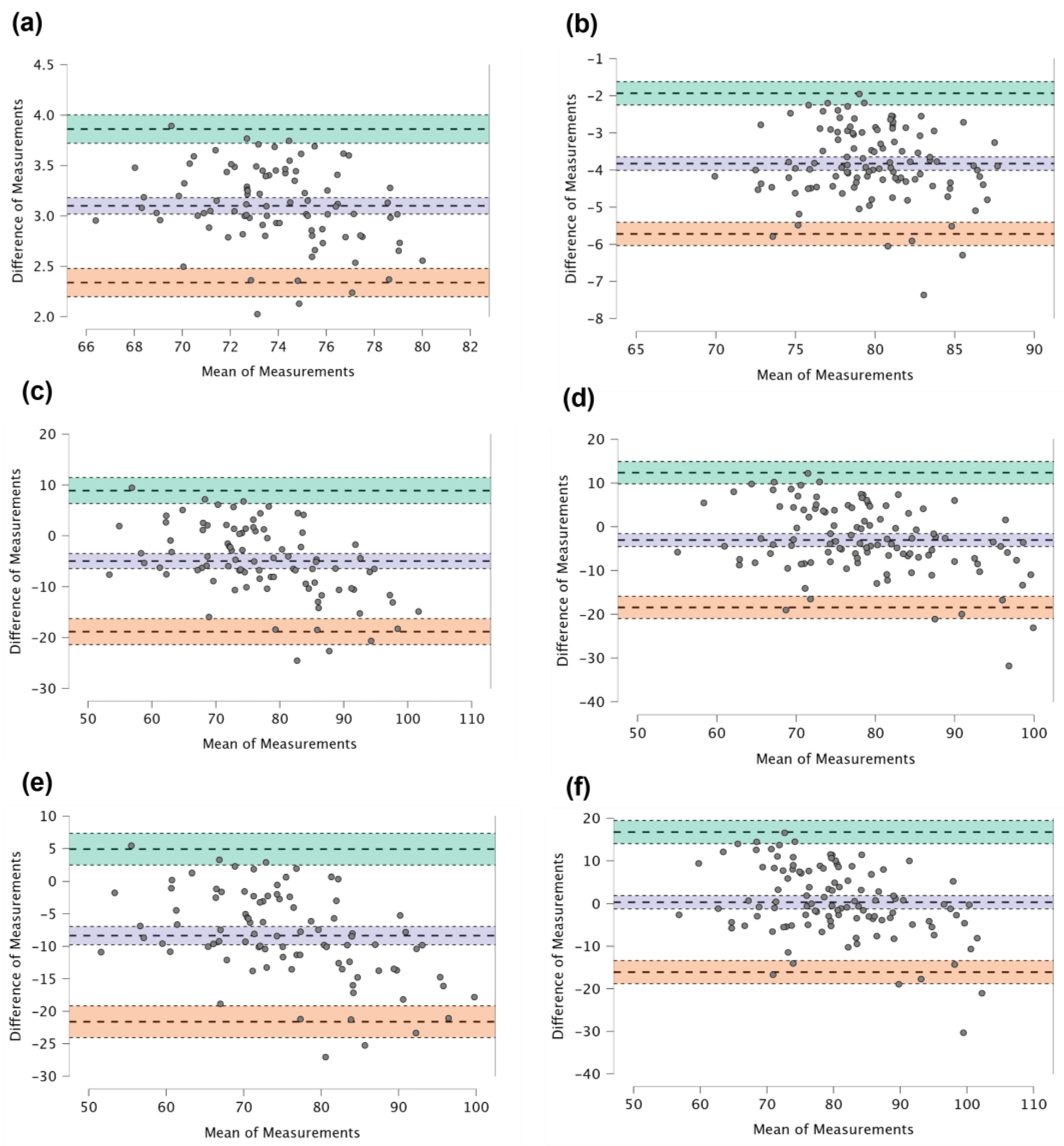

3.2.1. Precision

- Intra-rater agreement

- Inter-rater agreement

3.2.2. Accuracy

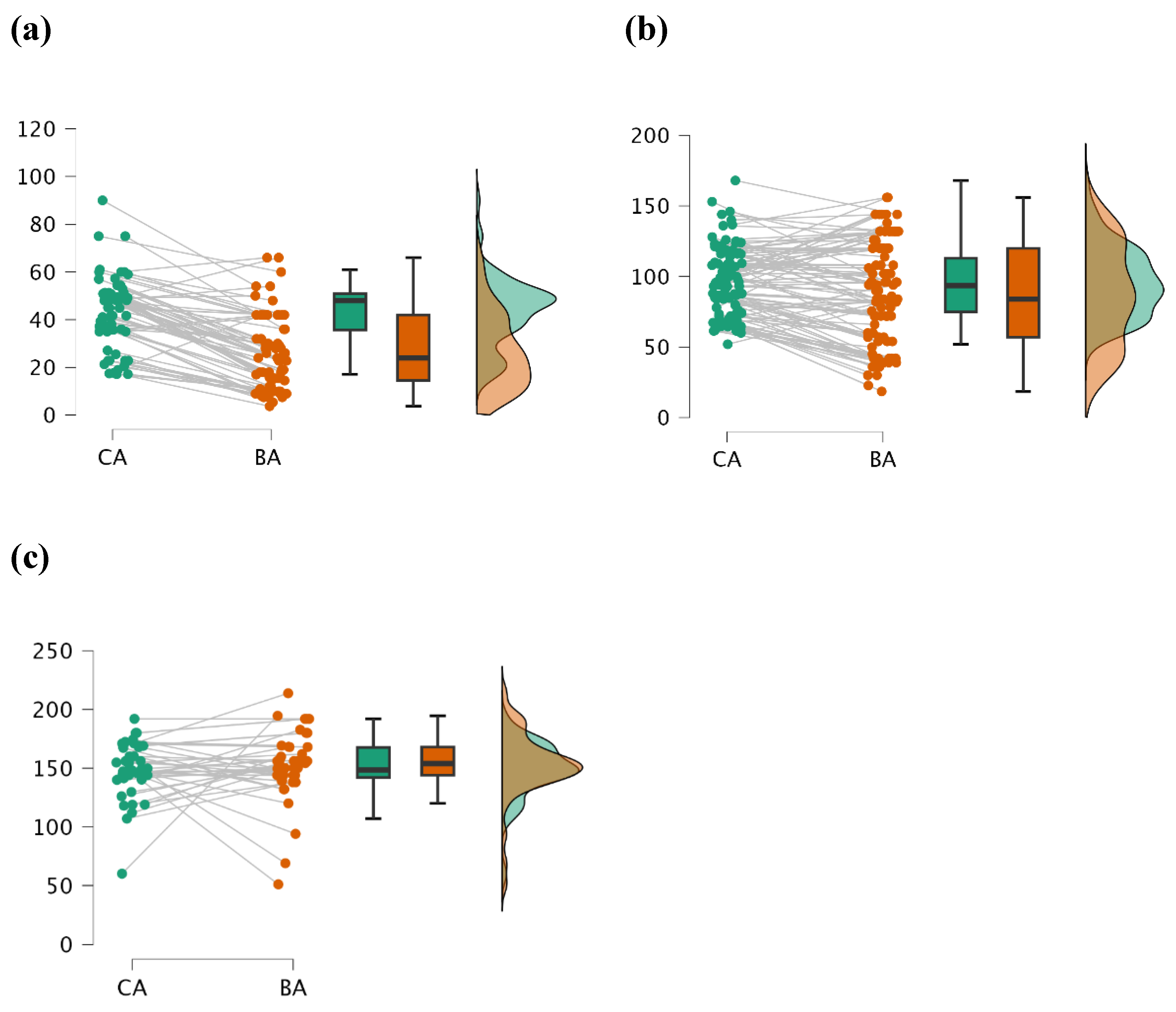

4. Discussion

4.1. Precision of GP-Canary Atlas

- Intra-rater agreement

- Inter-rater agreement

4.2. Accuracy of GP-Canary Atlas

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tanner, J.M. Growth at Adolescence; Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford, UK, 1962.

- Toledo Trujillo, F.M.; Others. Atlas Radiológico de Referencia de la Edad Ósea en la Población Canaria; Fundación Canaria de Salud y Sanidad de Tenerife: Santa Cruz de Tenerife, España, 2009.

- Nandiraju, D.; Ahmed, I. Human skeletal physiology and factors affecting its modeling and remodeling. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 112(5), 775–781. [CrossRef]

- Macias, H.; Hinck, L. Mammary Gland Development. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 2012, 1, 533–557. [CrossRef]

- Susman, E.J.; Houts, R.M.; Steinberg, L.; Belsky, J.; Cauffman, E.; Dehart, G.; Friedman, S.L.; Roisman, G.I.; Halpern-Felsher, B.L.; Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Longitudinal Development of Secondary Sexual Characteristics in Girls and Boys Between Ages 9½ and 15½ Years. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2010, 164, 166–173. [CrossRef]

- Bangalore Krishna, K.; Witchel, S.F. Normal Puberty. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 2024, 53, 183–194. [CrossRef]

- Niwczyk, O.; Grymowicz, M.; Szczęsnowicz, A.; Hajbos, M.; Kostrzak, A.; Budzik, M.; Maciejewska-Jeske, M.; Bala, G.; Smolarczyk, R.; Męczekalski, B. Bones and Hormones: Interaction Between Hormones of the Hypothalamus, Pituitary, Adipose Tissue and Bone. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6840. [CrossRef]

- Ulijaszek, S.J. The International Growth Standard for Children and Adolescents Project: Environmental Influences on Preadolescent and Adolescent Growth in Weight and Height. Food Nutr. Bull. 2006, 27, S279–S294. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.B. Genetic Determinants of Maturation Under Favorable Environmental Conditions. Genet. Dev. 2017, 5, 112–125.

- Cavallo, F.; Mohn, A.; Chiarelli, F.; Giannini, C. Evaluation of Bone Age in Children: A Mini-Review. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 580314. [CrossRef]

- Navarro, M.M.; Tejedor, B.M.; Siguero, J.P.L. El uso de la edad ósea en la práctica clínica. Anales de Pediatría Continuada 2014, 12(6), 275-283.

- Roberts, C.D. Influence of Environment on Genetic Control of Maturation: A Longitudinal Study. Environ. Genet. 2019, 28, 78–91.

- Díaz Gómez, M.N. Crecimiento y desarrollo físico del niño; Tenerife, 1992; (18).

- Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Z. Clinical Methods for Bone Age Assessment in Pediatrics. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 31, 487–495.

- Smith, R.; Johnson, M.; Williams, L. Hormonal Profiling in Pediatric Endocrinology. Endocr. Rev. 2020, 42, 301–318.

- Gilsanz, V.; Ratib, O. Hand Bone Age: A Digital Atlas of Skeletal Maturity; Springer: 2011.

- Dwyer, A.A.; Hayes, F.J. Evaluation of Endocrine Disorders of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) Axis. In: Llahana, S., Follin, C., Yedinak, C., Grossman, A. (Eds.) Advanced Practice in Endocrinology Nursing; Springer: Cham, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Brown, B. Pediatric Bone Age Assessment: A Practical Guide; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- Greulich, W.W.; Pyle, S.I. Radiographic Atlas of Skeletal Development of the Hand and Wrist, 2nd ed.; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1959.

- Prokop-Piotrkowska, M.; Marszałek-Dziuba, K.; Moszczyńska, E.; Szalecki, M.; Jurkiewicz, E. Traditional and New Methods of Bone Age Assessment—An Overview. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2021, 13, 251–262. [CrossRef]

- Satoh, M.; Hasegawa, Y. Factors affecting prepubertal and pubertal bone age progression. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 967711. [CrossRef]

- Grgic O, Shevroja E, Dhamo B, Uitterlinden AG, Wolvius EB, Rivadeneira F, Medina-Gomez C. Skeletal maturation in relation to ethnic background in children of school age: The Generation R Study. Bone. 2020 Mar;132:115180. [CrossRef]

- Khadilkar, V.; Oza, C.; Khadilkar, A. Relationship between Height Age, Bone Age and Chronological Age in Normal Children in the Context of Nutritional and Pubertal Status. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 35, 767–775. [CrossRef]

- Toledo Trujillo, F.M. Maduración ósea en una muestra de población urbana de las islas Canarias; Doctoral Thesis, Universidad La Laguna: San Cristóbal de La Laguna, España, 1978.

- Zhang, A.; Sayre, J.W.; Vachon, L.; Liu, B.J.; Huang, H.K. Racial Differences in Growth Patterns of Children Assessed on the Basis of Bone Age. Radiology 2009, 250, 228–235. [CrossRef]

- Martín Pérez, S.E.; Martín Pérez, I.M.; Vega González, J.M.; Molina Suárez, R.; León Hernández, C.; Rodríguez Hernández, F.; Herrera Perez, M. Precision and Accuracy of Radiological Bone Age Assessment in Children Among Different Ethnic Groups: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13, 3124. [CrossRef]

- Ontell, F.K.; Ivanovic, M.; Ablin, D.S.; Barlow, T.W. Bone Age in Children of Diverse Ethnicity. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1996, 167, 1395–1398. [CrossRef]

- Fregel, R.; Ordóñez, A.C.; Serrano, J.G. The Demography of the Canary Islands from a Genetic Perspective. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2021, 30, R1. [CrossRef]

- Alshamrani, K.; Messina, F.; Offiah, A.C. Is the Greulich and Pyle Atlas Applicable to All Ethnicities? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Radiol. 2019, 29, 2910–2923. [CrossRef]

- Bossuyt, P.M.; Reitsma, J.B.; Bruns, D.E.; Gatsonis, C.A.; Glasziou, P.P.; Irwig, L.; Lijmer, J.G.; Moher, D.; Rennie, D.; de Vet, H.C.; Kressel, H.Y.; Rifai, N.; Golub, R.M.; Altman, D.G.; Hooft, L.; Korevaar, D.A.; Cohen, J.F.; STARD Group. STARD 2015: An Updated List of Essential Items for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy Studies. BMJ 2015, 351, h5527. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.K.; Kumar, B.; Acharya, A. Radiographic Imaging of the Wrist. Indian J. Plast. Surg. 2011, 44, 186–196. [CrossRef]

- Hardy, D.C.; Totty, W.G.; Reinus, W.R.; Gilula, L.A. Posteroanterior Wrist Radiography: Importance of Arm Positioning. J. Hand Surg. Am. 1987, 12, 504–508. [CrossRef]

- Govender, D.; Goodier, M. Bone of Contention: The Applicability of the Greulich–Pyle Method for Skeletal Age Assessment in South Africa. South Afr. J. Radiol. 2018, 22, 6. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, P.K.; Gupta, M.; Verma, A.; Pandey, S.; Nayak, A. Applicability of the Greulich-Pyle Method in Assessing the Skeletal Maturity of Children in the Eastern Utter Pradesh (UP) Region: A Pilot Study. Cureus 2020, 12, e10880. [CrossRef]

- KKim, J.R.; Lee, Y.S.; Yu, J. Assessment of Bone Age in Prepubertal Healthy Korean Children: Comparison Among the Korean Standard Bone Age Chart, Greulich-Pyle Method, and Tanner-Whitehouse Method. Korean J. Radiol. 2015, 16, 201–205. [CrossRef]

- Fraga Bermúdez, J.M.; Fernández Lorenzo, J.R. La Pediatría, el Niño y el Pediatra: Una Aproximación General. In: Tratado de Pediatría, 1st ed.; Moro Serrano, M., Málaga Guerrero, S., Madero López, L., Eds.; Editorial Médica Panamericana: Madrid, Spain, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 1–18.

- Hackman, L.; Black, S. The Reliability of the Greulich and Pyle Atlas When Applied to a Modern Scottish Population. J. Forensic Sci. 2012, 58, 114–119. [CrossRef]

- Maggio, A.; Flavel, A.; Hart, R.; Franklin, D. Assessment of the Accuracy of the Greulich and Pyle Hand-Wrist Atlas for Age Estimation in a Contemporary Australian Population. Aust. J. Forensic Sci. 2016, 50, 385–395. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Koch, B.; Schulz, R.; Reisinger, W.; Schmeling, A. Comparative Analysis of the Applicability of the Skeletal Age Determination Methods of Greulich–Pyle and Thiemann–Nitz for Forensic Age Estimation in Living Subjects. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2007, 121, 293–296. [CrossRef]

- Van Rijn, R.R.; Lequin, M.H.; Robben, S.G.F.; Hop, W.C.J.; van Kuijk, C. Is the Greulich and Pyle Atlas Still Valid for Dutch Caucasian Children Today? Pediatr. Radiol. 2001, 31, 748–752. [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.; Ferreira, M.; Alves, F.C.; Cunha, E. Comparative Study of Greulich and Pyle Atlas and Maturos 4.0 Program for Age Estimation in a Portuguese Sample. Forensic Sci. Int. 2011, 212, 276.e1–276.e7. [CrossRef]

- Pinchi, V.; De Luca, F.; Ricciardi, F.; Focardi, M.; Piredda, V.; Mazzeo, E.; Norelli, G.-A. Skeletal age estimation for forensic purposes: A comparison of GP, TW2 and TW3 methods on an Italian sample. Forensic Sci Int. 2014, 238, 83–90. [CrossRef]

- Santoro, V.; Roca, R.; De Donno, A.; Fiandaca, C.; Pinto, G.; Tafuri, S.; Introna, F. Applicability of Greulich and Pyle and Demirijan aging methods to a sample of Italian population. Forensic Sci Int. 2012, 221, 153.e1–153.e5. [CrossRef]

- Calfee, R.P.; Sutter, M.; Steffen, J.A.; Goldfarb, C.A. Skeletal and chronological ages in American adolescents: Current findings in skeletal maturation. J Child Orthop. 2010, 4, 467–470. [CrossRef]

- Kullman, L. Accuracy of two dental and one skeletal age estimation method in Swedish adolescents. Forensic Sci Int. 1995, 75, 225–236. [CrossRef]

- Olaotse B., Norma P.G., Kaone P.-M., Morongwa M., Janes M., Kabo K., Shathani M., Thato P. Evaluation of the suitability of the Greulich and Pyle atlas in estimating age for the Botswana population using hand and wrist radiographs of young Botswana population. Forensic Sci. Int. Rep. 2023,7. [CrossRef]

- Dembetembe K.A., Morris A.G. Is Greulich–Pyle age estimation applicable for determining maturation in male Africans? South Afr. J. Sci. 2012,108. [CrossRef]

- Albaker A.B., Aldhilan A.S., Alrabai H.M., AlHumaid S., AlMogbil I.H., Alzaidy N.F.A., Alsaadoon S.A.H., Alobaid O.A., Alshammary F.H. Determination of Bone Age and its Correlation to the Chronological Age Based on the Greulich and Pyle Method in Saudi Arabia. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2021,1186–1195. [CrossRef]

- Nang K.M., Ismail A.J., Tangaperumal A., Wynn A.A., Thein T.T., Hayati F., Teh Y.G. Forensic age estimation in living children: How accurate is the Greulich-Pyle method in Sabah, East Malaysia? Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11,1137960. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.Y.; Lee, K.S.; Bezuidenhout, A.F.; Kruskal, J.B. Spectrum of Cognitive Biases in Diagnostic Radiology. Radiographics 2024, 44, e230059. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Gandomkar, Z.; Reed, W.M. Investigating the Impact of Cognitive Biases in Radiologists' Image Interpretation: A Scoping Review. Eur. J. Radiol. 2023, 166, 111013. [CrossRef]

- Busby, L.P.; Courtier, J.L.; Glastonbury, C.M. Bias in Radiology: The How and Why of Misses and Misinterpretations. Radiographics 2018, 38, 236–247. [CrossRef]

- Berst, M.J.; Dolan, L.; Bogdanowicz, M.M.; Stevens, M.A.; Chow, S.; Brandser, E.A. Effect of Knowledge of Chronologic Age on the Variability of Pediatric Bone Age Determined Using the Greulich and Pyle Standards. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2001, 176, 507–510. [CrossRef]

- Alshamrani, K.; Offiah, A.C. Applicability of Two Commonly Used Bone Age Assessment Methods to Twenty-First Century UK Children. Eur. Radiol. 2019, 30, 504–513. [CrossRef]

- Zabet, D.; Rérolle, C.; Pucheux, J.; Telmon, N.; Saint-Martin, P. Can the Greulich and Pyle Method Be Used on French Contemporary Individuals? Int. J. Leg. Med. 2014, 129, 171–177. [CrossRef]

- Dawes, T.J.; Vowler, S.L.; Allen, C.M.; Dixon, A.K. Training Improves Medical Student Performance in Image Interpretation. Br. J. Radiol. 2004, 77, 775–776. [CrossRef]

- Vincent, C.A.; Driscoll, P.A.; Audley, R.J.; Grant, D.S. Accuracy of Detection of Radiographic Abnormalities by Junior Doctors. Arch. Emerg. Med. 1988, 5, 101–109. [CrossRef]

- Christiansen JM, Gerke O, Karstoft J, Andersen PE. Poor interpretation of chest X-rays by junior doctors. Dan Med J. 2014 Jul, 61(7), A4875.

- Cheung, T.; Harianto, H.; Spanger, M.; Young, A.; Wadhwa, V. Low Accuracy and Confidence in Chest Radiograph Interpretation Amongst Junior Doctors and Medical Students. Intern. Med. J. 2018, 48, 864–868. [CrossRef]

- Martrille, L.; Papadodima, S.; Venegoni, C.; Molinari, N.; Gibelli, D.; Baccino, E.; Cattaneo, C. Age Estimation in 0–8-Year-Old Children in France: Comparison of One Skeletal and Five Dental Methods. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1042.

- Al-Khater, K.M.; Hegazi, T.M.; Al-Thani, H.F.; Al-Muhanna, H.T.; Al-Hamad, B.W.; Alhuraysi, S.M.; Alsfyani, W.A.; Alessa, F.W.; Al-Qwairi, A.O.; Al-Qwairi, A.O.; Bayer, S.B.; Siddiqui, F.B. Time of appearance of ossification centers in carpal bones: A radiological retrospective study on Saudi children. Saudi Med. J. 2020, 41, 938–946. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds E. Degree of kinship and pattern of ossification. A longitudinal X-ray study of the appearance pattern of ossification centers in children of different kinship groups. AJBA. 1943, 1(4), 405-416. [CrossRef]

- Gaudino, R.; De Filippo, G.; Bozzola, E.; Gasparri, M.; Bozzola, M.; Villani, A.; Radetti, G. Current clinical management of constitutional delay of growth and puberty. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2022, 48(1), 45. [CrossRef]

- Rosenfield, R.L.; Lipton, R.B.; Drum, M.L. Thelarche, Pubarche, and Menarche Attainment in Children with Normal and Elevated Body Mass Index. Pediatrics 2009, 123, 84–88. Erratum in: Pediatrics 2009, 123, 1255. [CrossRef]

- De Bont, J.; Díaz, Y.; Casas, M.; García-Gil, M.; Vrijheid, M.; Duarte-Salles, T. Time Trends and Sociodemographic Factors Associated with Overweight and Obesity in Children and Adolescents in Spain. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e201171. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, Q.; Deng, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Story, M. Association between Obesity and Puberty Timing: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1266. [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.; Reinehr, T.; Roth, C.L. Connections Between Obesity and Puberty: Invited by Manuel Tena-Sempere, Cordoba. Curr. Opin. Endocr. Metab. Res. 2020, 14, 160–168. [CrossRef]

- Gavela-Pérez, T.; Garcés, C.; Navarro-Sánchez, P.; López Villanueva, L.; Soriano-Guillén, L. Earlier Menarcheal Age in Spanish Girls Is Related with an Increase in Body Mass Index Between Pre-Pubertal School Age and Adolescence. Pediatr. Obes. 2015, 10, 410–415. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rodrigo, C.; Aranceta Bartrina, J.; Serra Majem, L.; Moreno, B.; Delgado Rubio, A. Epidemiology of Obesity in Spain. Dietary Guidelines and Strategies for Prevention. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2006, 76, 163–171. [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, L. Childhood Obesity and Central Precocious Puberty. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 1056871. [CrossRef]

- Ebrí Torné, B. Comparative Study Between Bone Ages: Carpal, Metacarpophalangic, Carpometacarpophalangic Ebrí, Greulich and Pyle, and Tanner Whitehouse2. Med. Res. Arch. 2021, 9, e2625. [CrossRef]

- Soudack, M.; Ben-Shlush, A.; Jacobson, J.; Raviv-Zilka, L.; Eshed, I.; Hamiel, O. Bone Age in the 21st Century: Is Greulich and Pyle’s Atlas Accurate for Israeli Children? Pediatr. Radiol. 2012, 42, 343–348.

- Cantekin, K.; Celikoglu, M.; Miloglu, O.; Dane, A.; Erdem, A. Bone Age Assessment: The Applicability of the Greulich-Pyle Method in Eastern Turkish Children. J. Forensic Sci. 2011, 57, 679–682. [CrossRef]

- Tsehay, B.; Afework, M.; Mesifin, M. Assessment of Reliability of Greulich and Pyle (GP) Method for Determination of Age of Children at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, East Gojjam Zone. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2017, 27, 631–640.

- Kowo-Nyakoko, F.; Gregson, C.L.; Madanhire, T.; Stranix-Chibanda, L.; Rukuni, R.; Offiah, A.C.; Micklesfield, L.K.; Cooper, C.; Ferrand, R.A.; Rehman, A.M.; et al. Evaluation of Two Methods of Bone Age Assessment in Peripubertal Children in Zimbabwe. Bone 2023, 170, 116725. [CrossRef]

| Stage | Gender | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mos.) | Preschool | Female | 24 | 39.33 | 15.18 | 20.00 | 67.00 | 0.235 |

| Male | 45 | 46.49 | 13.33 | 18.00 | 69.00 | 0.105 | ||

| Scholar | Female | 40 | 92.00 | 26.08 | 85.00 | 118.00 | 0.310 | |

| Male | 62 | 100.16 | 20.33 | 75.00 | 109.00 | 0.089 | ||

| Teenager | Female | 16 | 144.17 | 23.81 | 102.00 | 168.00 | 0.150 | |

| Male | 27 | 151.53 | 20.17 | 107.00 | 192.00 | 0.080 | ||

| Weight (kg) | Preschool | Female | 24 | 14.52 | 2.05 | 9.80 | 18.60 | 0.215 |

| Male | 45 | 13.09 | 2.17 | 7.40 | 18.00 | 0.175 | ||

| Scholar | Female | 40 | 29.58 | 7.14 | 17.60 | 40.00 | 0.200 | |

| Male | 62 | 23.67 | 4.85 | 14.20 | 44.00 | 0.115 | ||

| Teenager | Female | 16 | 33.84 | 4.62 | 22.00 | 39.50 | 0.250 | |

| Male | 27 | 34.21 | 3.19 | 23.80 | 45.70 | 0.140 | ||

| Height (m) | Preschool | Female | 24 | 0.91 | 0.07 | 0.77 | 1.05 | 0.289 |

| Male | 45 | 0.94 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 1.10 | 0.175 | ||

| Scholar | Female | 40 | 1.14 | 0.07 | 0.99 | 1.30 | 0.200 | |

| Male | 62 | 1.16 | 0.05 | 0.94 | 1.40 | 0.115 | ||

| Teenager | Female | 16 | 1.33 | 0.04 | 1.21 | 1.37 | 0.250 | |

| Male | 27 | 1.33 | 0.03 | 1.16 | 1.45 | 0.140 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | Preschool | Female | 24 | 17.53 | 2.47 | 8.32 | 19.49 | 0.180 |

| Male | 45 | 14.81 | 2.45 | 18.81 | 18.87 | 0.120 | ||

| Scholar | Female | 40 | 22.76 | 5.49 | 13.45 | 20.29 | 0.175 | |

| Male | 62 | 17.59 | 3.60 | 12.57 | 20.92 | 0.150 | ||

| Teenager | Female | 16 | 19.13 | 2.66 | 15.02 | 21.73 | 0.240 | |

| Male | 27 | 19.33 | 1.80 | 14.61 | 20.99 | 0.130 |

| Group | Time of measurement | Gender | Mean | ICC | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rater 1 | T1 | Female | 77.65 | |||

| Male | 78.33 | |||||

| T2 | Female | 75.25 | 0.995 | 0.990 | 0.998 | |

| Male | 76.21 | 0.996 | 0.992 | 0.998 | ||

| Rater 2 | T1 | Female | 74.10 | |||

| Male | 82.47 | |||||

| T2 | Female | 70.57 | 0.990 | 0.979 | 0.995 | |

| Male | 80.94 | 0.992 | 0.982 | 0.996 | ||

| Rater 3 | T1 | Female | 78.79 | |||

| Male | 78.62 | |||||

| T2 | Female | 80.67 | 0.921 | 0.832 | 0.964 | |

| Male | 81.83 | 0.976 | 0.947 | 0.989 |

| Groups | Gender | Mean | ICC | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rater 1 - Rater 2 | Female | 75.73 | |||

| 72.34 | 0.982 | 0.968 | 0.990 | ||

| Male | 78.33 | ||||

| 81.70 | 0.944 | 0.902 | 0.968 | ||

| Rater 1 - Rater 3 | Female | 75.73 | |||

| 79.73 | 0.463 | 0.216 | 0.654 | ||

| Male | 78.33 | ||||

| 80.22 | 0.408 | 0.145 | 0.618 | ||

| Rater 2 - Rater 3 | Female | 72.34 | |||

| 79.73 | 0.509 | 0.273 | 0.688 | ||

| Male | 81.70 | ||||

| 80.22 | 0.327 | 0.052 | 0.557 |

| Stage | Mean | SD | MD | W | Z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preschool (n = 69) | CA | 43.485 | 14.476 | ||||

| BA | 26.449 | 15.409 | 17.036 | 2297.5 | 6.517 | < 0.001*** | |

| Female | CA | 39.331 | 15.182 | ||||

| BA | 24.250 | 16.896 | 15.081 | 390.0 | 3.730 | < 0.001*** | |

| Male | CA | 46.496 | 13.333 | ||||

| BA | 31.598 | 24.881 | 14.898 | 776.0 | 4.920 | < 0.001*** | |

| Scholar (n = 102) | CA | 95.684 | 23.906 | ||||

| BA | 87.519 | 35.572 | 8.165 | 3306.5 | 3.346 | < 0.001*** | |

| Female | CA | 92.001 | 26.086 | ||||

| BA | 88.052 | 37.203 | 3.949 | 849.0 | 1.182 | 0.239 | |

| Male | CA | 100.168 | 20.338 | ||||

| BA | 86.870 | 33.876 | 13.298 | 829.0 | 3.898 | < 0.001*** | |

| Teenager (n = 43) | CA | 148.883 | 23.665 | ||||

| BA | 152.042 | 29.943 | -3.159 | 339.00 | -0.954 | 0.823 | |

| Female | CA | 144.170 | 23.810 | ||||

| BA | 148.667 | 24.231 | - 4.497 | 69.0 | 0.052 | 0.980 | |

| Male | CA | 151.53 | 20.176 | ||||

| BA | 156.38 | 18.179 | - 4.85 | 91.50 | -1.686 | 0.094 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).