Submitted:

30 August 2024

Posted:

02 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

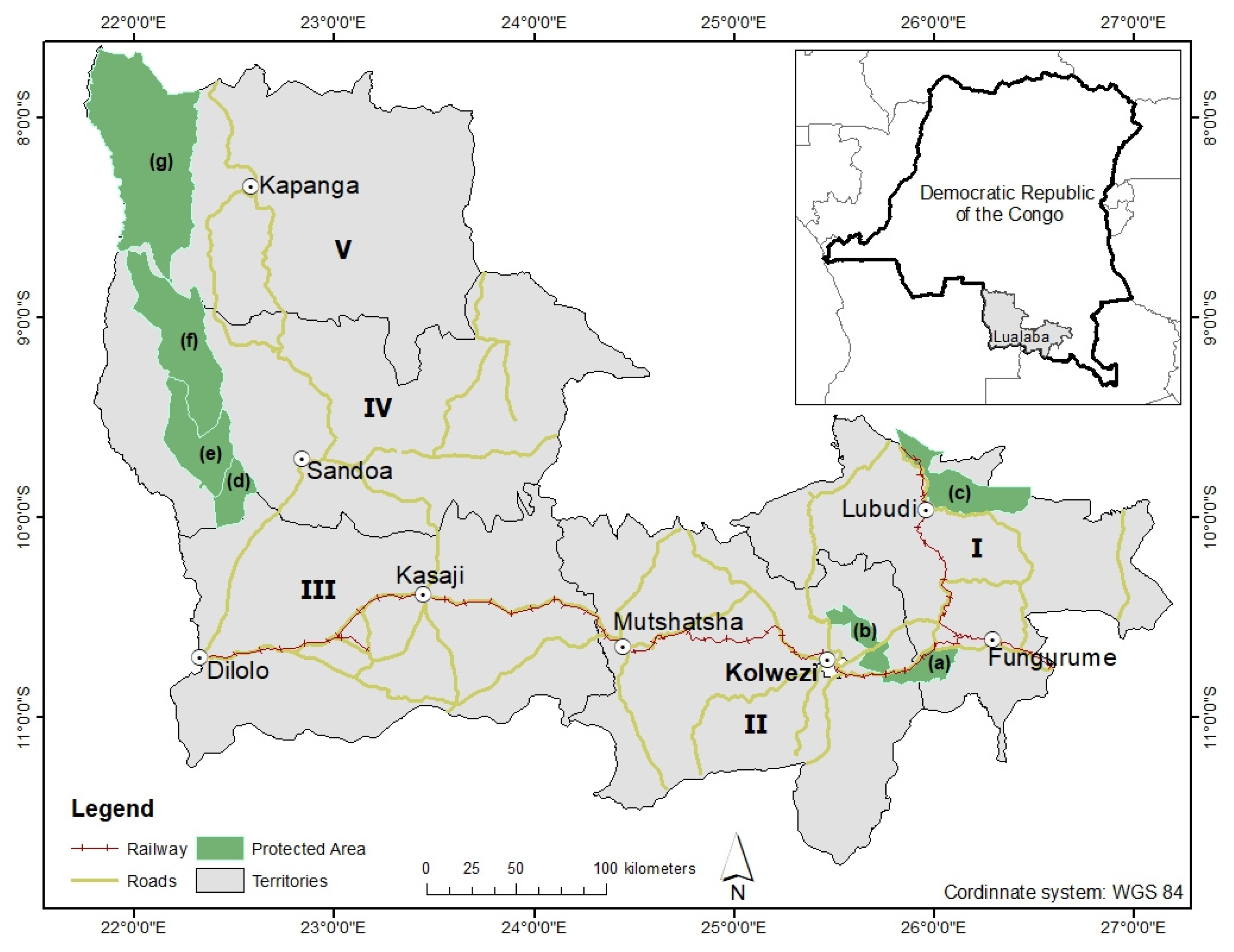

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data

2.3. Classifications

2.4. Quantifying Spatio-Temporal Pattern Changes in Forest Ecosystems

3. Results

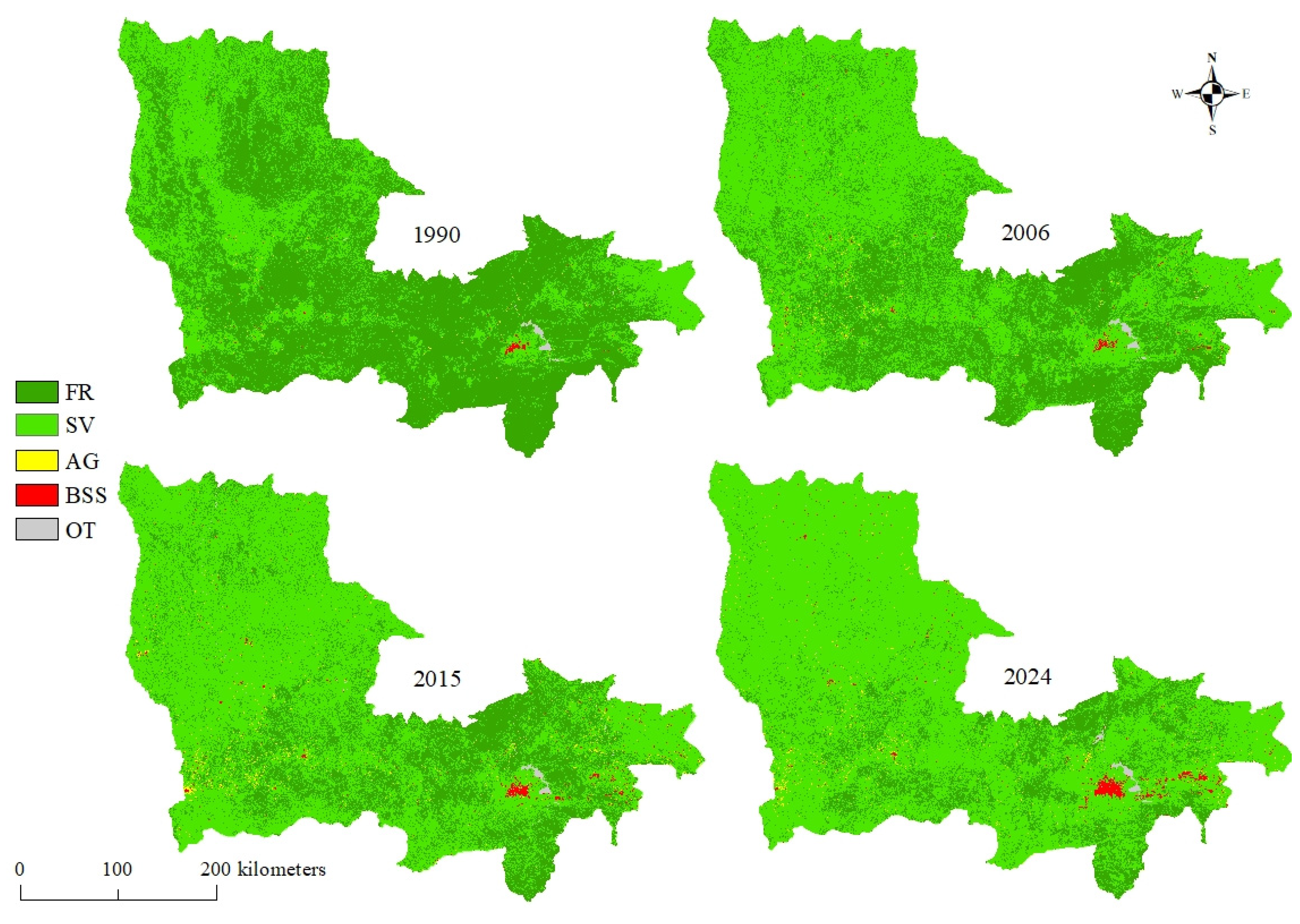

3.1. Classification Accuracy and Mapping

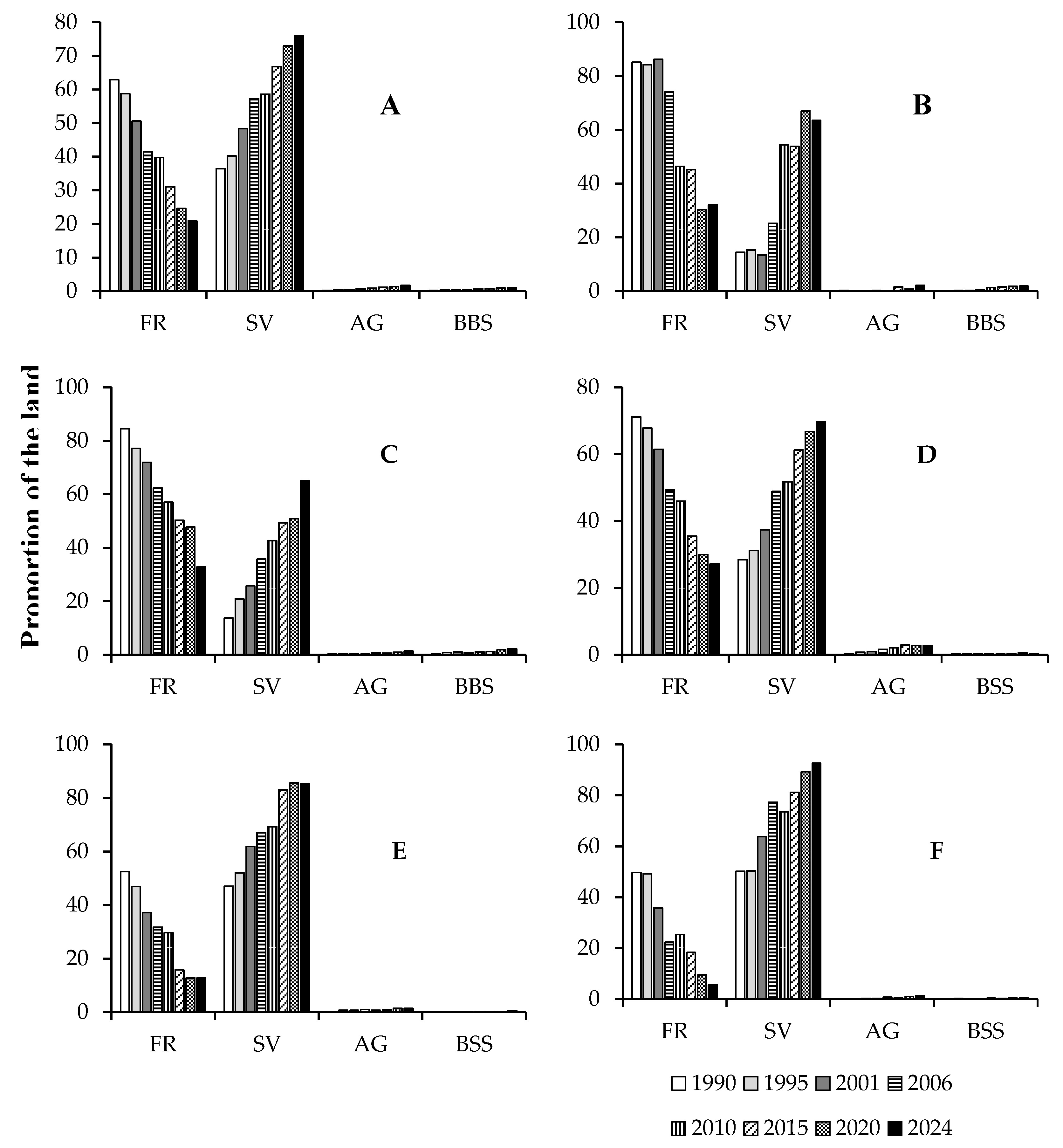

3.2. Landscape Composition Dynamics

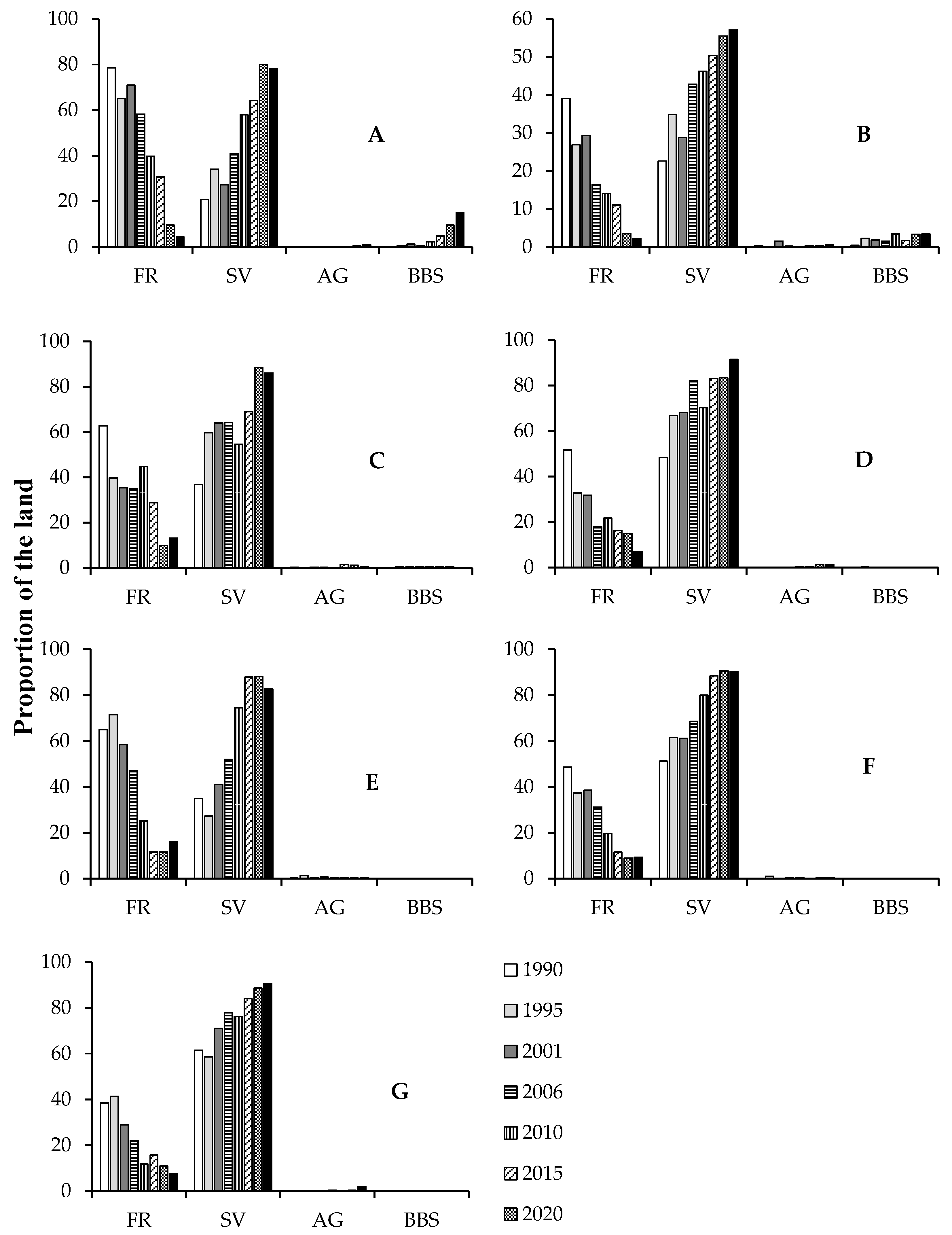

3.2.1. Composition Dynamics in Lualaba Province and Its Territories

3.2.2. Dynamics of Land Cover Composition within Protected Areas in Lualaba Province

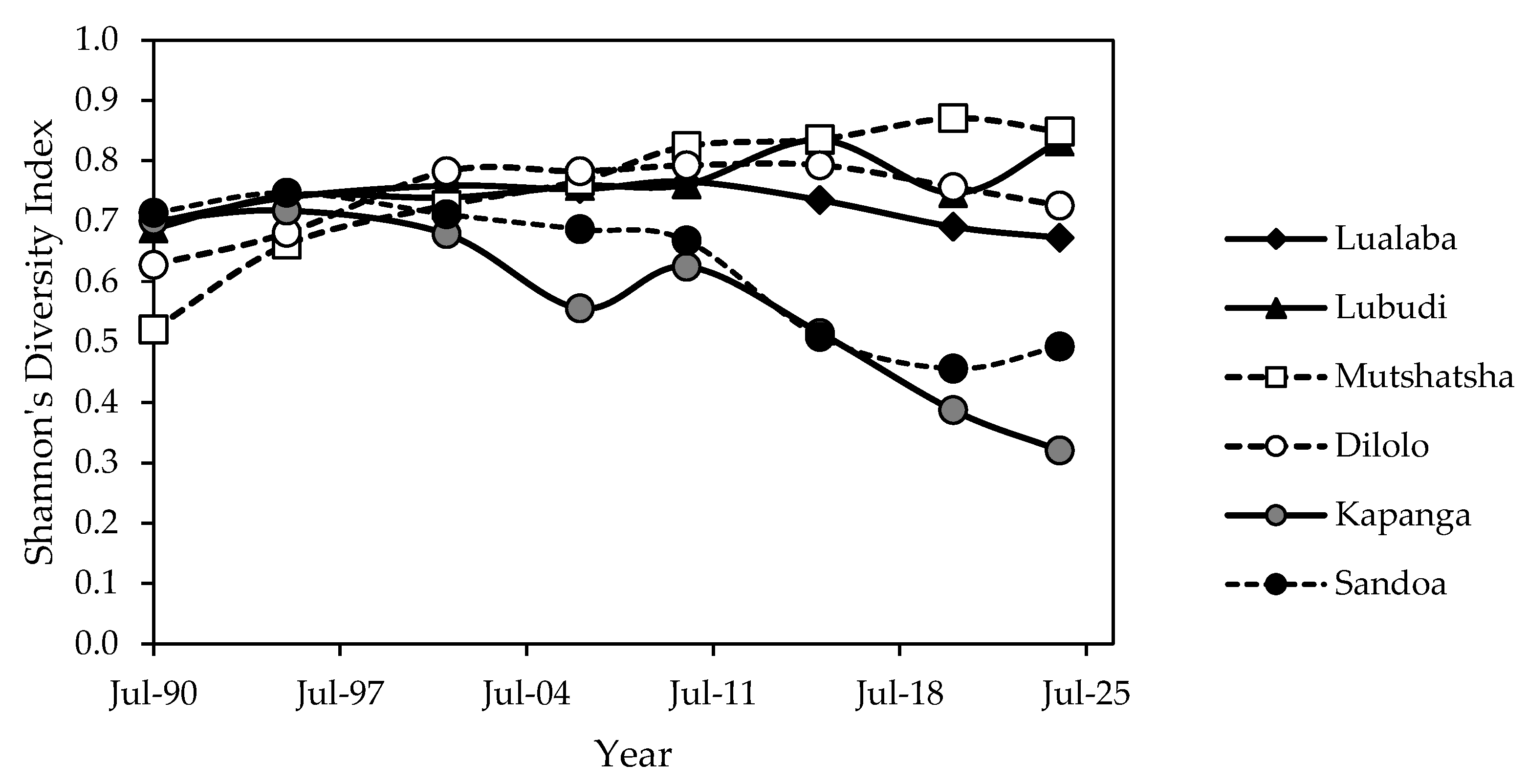

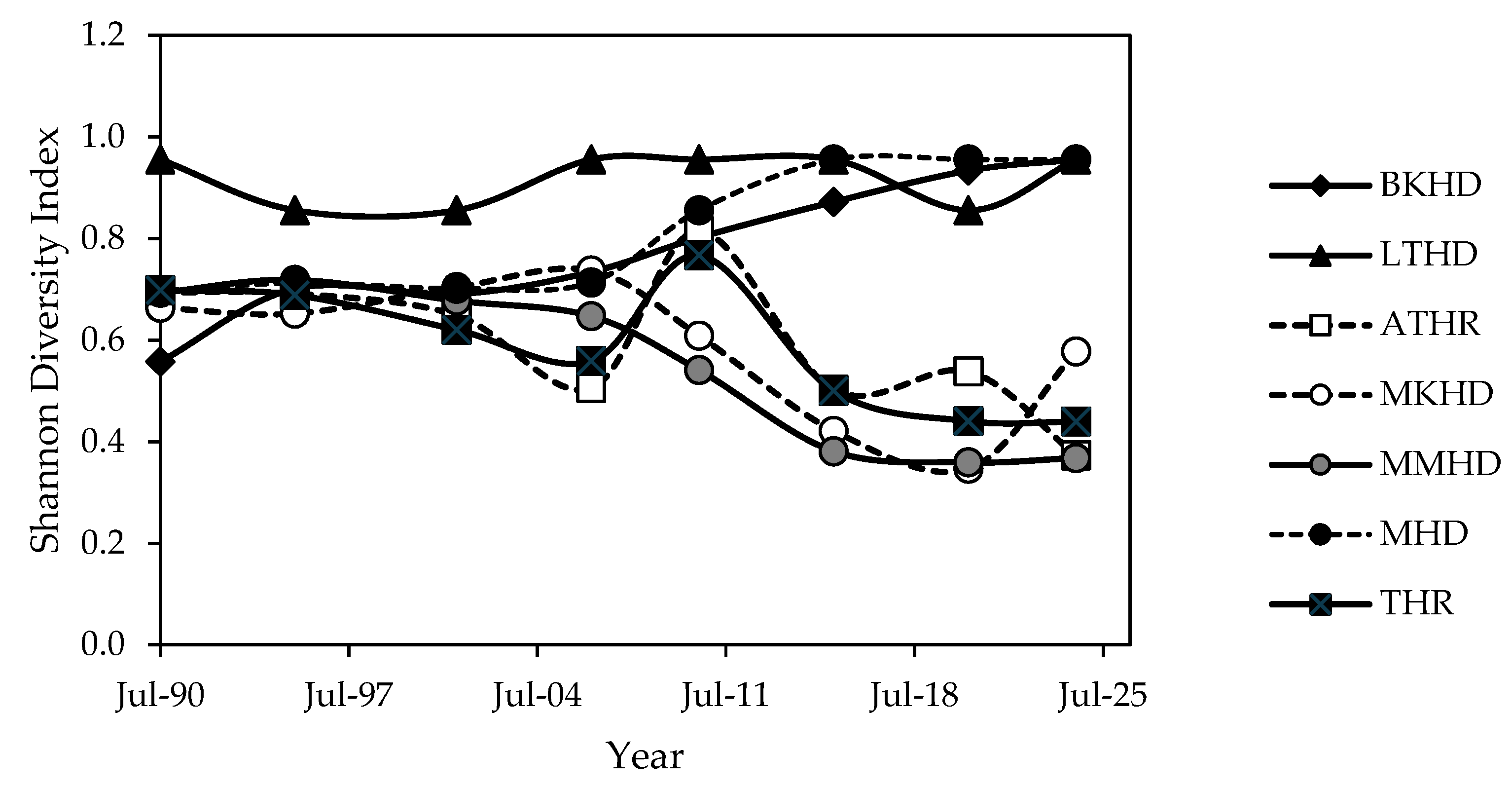

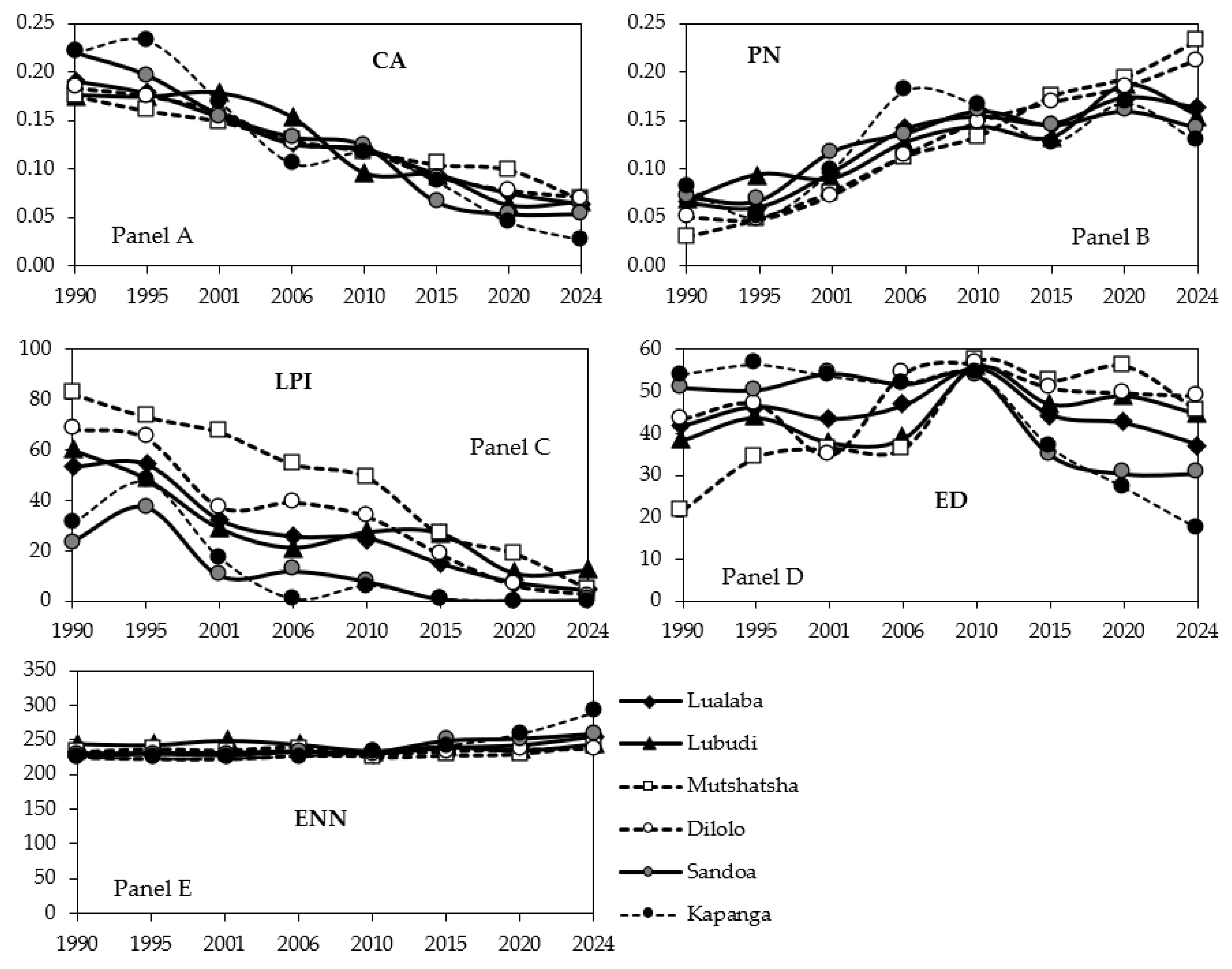

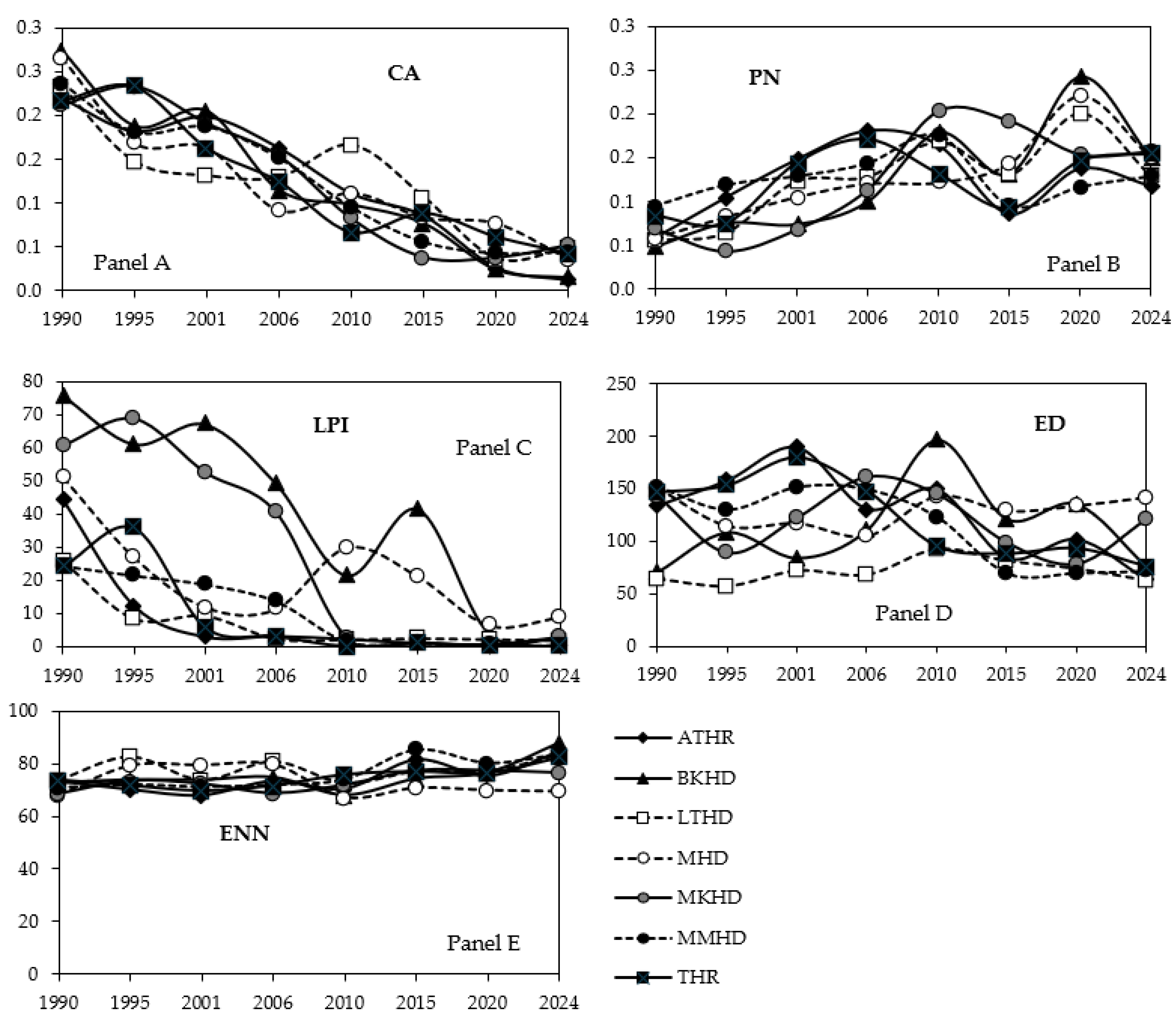

3.4. Analysis of the Spatial Pattern Dynamics

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodology

4.2. Anthropogenic Pressures and Extent of the Hierarchical Changes in the Spatio-Temporal Pattern of Deforestation in Lualaba Province

4.3. Implications for the Conservation of Landscape and Forest Ecosystems in Lualaba

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malhi, Y.; Meir, P.; Brown, S. Forests, Carbon and Global Climate. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2002, 360, 1567–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, A.S.; Lertzman, K.P.; Gustafsson, L. Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services in Forest Ecosystems: A Research Agenda for Applied Forest Ecology. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 54, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulumbati, M.C.; Godoy Jara, M.; Baboy Longanza, L.; Bogaert, J.; Werbrouck, S.; Sikuzani, Y.U.; Mazinga Kwey, M. In Vitro Regeneration Protocol for Securidaca longepedunculata Fresen. , a Threatened Medicinal Plant within the Region of Lubumbashi (Democratic Republic of the Congo). Conservation 2023, 3, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, K.T. Forest Types and Their Associated Soils. In Forest Soils: Properties and Management; Osman, K.T., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2013; pp. 123–155. [Google Scholar]

- Dirzo, R. Seasonally Dry Tropical Forests: Ecology and Conservation; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Claros, M.; Poorter, L.; Alarcón, A.; Blate, G.; Choque, U.; Fredericksen, T.S.; Toledo, M. Soil Effects on Forest Structure and Diversity in a Moist and a Dry Tropical Forest. Biotropica 2012, 44, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colfer, C.J.P.; Elias, M.; Jamnadass, R. Women and Men in Tropical Dry Forests: A Preliminary Review. Int. For. Rev. 2015, 17, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, L.; Newton, A.C.; DeFries, R.S.; Ravilious, C.; May, I.; Blyth, S.; Gordon, J.E. A Global Overview of the Conservation Status of Tropical Dry Forests. J. Biogeogr. 2006, 33, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackie, R.; Baldauf, C.; Gautier, D.; Gumbo, D.; Kassa, H.; Parthasarathy, N.; Sunderland, T. Tropical Dry Forests: The State of Global Knowledge and Recommendations for Future Research; Cifor: Bogor, Indonesia, 2014; 41p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jew, E.K.; Dougill, A.J.; Sallu, S.M.; O’Connell, J.; Benton, T.G. Miombo Woodland under Threat: Consequences for Tree Diversity and Carbon Storage. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 361, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syampungani, S.; Chirwa, P.W.; Akinnifesi, F.K.; Sileshi, G.; Ajayi, O.C. The Miombo Woodlands at the Cross Roads: Potential Threats, Sustainable Livelihoods, Policy Gaps and Challenges. In Proceedings of the Natural Resources Forum, Oxford, UK, Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2009, 33, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidumayo, E.N. Changes in Miombo Woodland Structure under Different Land Tenure and Use Systems in Central Zambia. J. Biogeogr. 2002, 29, 1619–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.S.; Matos, C.N.; Moura, I.R.; Washington-Allen, R.A.; Ribeiro, A.I. Monitoring Vegetation Dynamics and Carbon Stock Density in Miombo Woodlands. Carbon Balance Manag. 2013, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapov, P.V.; Turubanova, S.A.; Hansen, M.C.; Adusei, B.; Broich, M.; Altstt, A.; Mane, L.; Justice, C.O. Quantifying forest cover loss in Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2000–2010, with Landsat ETM+data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 122, 106–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kabulu Djibu, J.P.; Bamba, I.; Munyemba Kankumbi, F.; Defourny, P.; Vancutsem, C.; Nyembwe, N.S.; Bogaert, J. Analyse de la structure spatiale des forêts au Katanga. Annales de la Faculté des Sciences Agronomiques de l’Université de Lubumbashi 2008, 1.

- Cabala, K.S.; Useni, S.Y.; Sambieni, K.R.; Bogaert, J.; Munyemba, K.F. Dynamique des écosystèmes forestiers de l’Arc CuprifèreKatangais en République Démocratique du Congo. Causes, Transformations spatiales et ampleur. Tropicultura 2017, 35, 192–202. [Google Scholar]

- Useni, S.Y.; Malaisse, F.; Kaleba, S.C.; Kankumbi, F.M.; Bogaert, J. Le rayon de déforestation autour de la ville de Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, RD Congo): Synthèse. Tropicultura 2017, 35, 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Khoji, M.K.; N’Tambwe, N.D.-D.; Malaisse, F.; Waselin, S.; Sambiéni, K.R.; Cabala, K.S.; Munyemba, K.F.; Bastin, J.-F.; Bogaert, J.; Useni, S.Y. Quantification and Simulation of Landscape Anthropization around the Mining Agglomerations of SoutheasternKatanga (DR Congo) between 1979 and 2090. Land 2022, 11, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupin, L.; Nkono, C.; Burlet, C.; Muhashi, F.; Vanbrabant, Y. Land cover fragmentation using multi-temporal remote sensing on major mine sites in Southern Katanga (Democratic Republic of Congo). Adv. Remote Sens. 2013, 2, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaisse, F. How to Live and Survive in Zambezian Open Forest (Miombo Ecoregion); Les presses agronomiques de Gembloux: Gembloux, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, B.; Seto, K.C. Conceptualizing and Characterizing Micro-Urbanization: A New Perspective Applied to Africa. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 190, 103595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni, Y.S.; Malaisse, F.; Yona, J.M.; Mwamba, T.M.; Bogaert, J. Diversity, use and management of household-located fruit trees in two rapidly developing towns in Southeastern DR Congo. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 63, 127220. [Google Scholar]

- Gnassou, L. The End of the Commodities Super-Cycle and its Implications for the Democratic Republic of Congo in Crisis. Afr. Policy J. 2016, 12, 77. Available online: https://apj.hkspublications.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2017/03/APJ-2016.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2024).

- Useni, S.Y.; Muteya, H.K.; Bogaert, J. Miombo woodland, an ecosystem at risk of disappearance in the Lufira Biosphere Reserve (Upper Katanga, DR Congo)? A 39-years analysis based on Landsat images. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 24, e01333. [Google Scholar]

- Lele, N.; Joshi, P.K. Analyzing Deforestation Rates, Spatial Forest Cover Changes and Identifying Critical Areas of Forest Cover Changes in North-East India during 1972–1999. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2009, 156, 159–170. [Google Scholar]

- Hein, L.; Van Ierland, E. Efficient and Sustainable Management of Complex Forest Ecosystems. Ecol. Model. 2006, 190, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achard, F.; DeFries, R.; Eva, H.; Hansen, M.; Mayaux, P.; Stibig, H.J. Pan-Tropical Monitoring of Deforestation. Environ. Res. Lett. 2007, 2, 045022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achard, F.; Stibig, H.J.; Eva, H.D.; Lindquist, E.J.; Bouvet, A.; Arino, O.; Mayaux, P. Estimating Tropical Deforestation from Earth Observation Data. Carbon Manag. 2010, 1, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.J.; Townshend, J.R. Strategies for Monitoring Tropical Deforestation Using Satellite Data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2000, 21, 1461–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sy, V.; Herold, M.; Achard, F.; Asner, G.P.; Held, A.; Kellndorfer, J.; Verbesselt, J. Synergies of multiple remote sensing data sources for REDD+ monitoring. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 4, 696–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohn, R.C. Remote sensing for landscape ecology: New metric indicators for monitoring, modeling, and assessment of ecosystems. In CRC Press, 2018; pp. 1–350.

- Imbernon, J.; Branthomme, A. Characterization of landscape patterns of deforestation in tropical rain forests. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2001, 22, 1753–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, M.A.; Cardille, J.A. Remote sensing’s recent and future contributions to landscape ecology. Curr. Landsc. Ecol. Rep. 2020, 5, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Engelen, V.W.P.; Verdoodt, A.; Dijkshoorn, K.; Van Ranst, E. Soil and Terrain Data Base of Central African; SOTERCAF, Version 1.0; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2006; 22p. [Google Scholar]

- INS (Institut National de la Statistique). Anuaire Statistique RDC 2022; Ministère National du Plan: Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2022; 433p. [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Lavigne, S. Artisanal copper mining and conflict at the intersection of property rights and corporate strategies in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Extract. Ind. Soc. 2019, 6, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.P.; Wulder, M.A.; Loveland, T.R.; Woodcock, C.E.; Allen, R.G.; Anderson, M.C.; Zhu, Z. Landsat-8: Science and product vision for terrestrial global change research. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 145, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chander, G.; Markham, B.L.; Helder, D.L. Summary of current radiometric calibration coefficients for Landsat MSS, TM, ETM+, and EO-1 ALI sensors. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choate, M.J.; Rengarajan, R.; Storey, J.C.; Lubke, M. Geometric calibration updates to Landsat 7 ETM+ instrument for Landsat Collection 2 products. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, J.; Choate, M.; Lee, K. Landsat 8 operational land imager on-orbit geometric calibration and performance. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 11127–11152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermote, E.; Justice, C.; Claverie, M.; Franch, B. Preliminary analysis of the performance of the Landsat 8/OLI land surface reflectance product. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 185, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhu, X.; Vogelmann, J.E.; Gao, F.; Jin, S. A simple and effective method for filling gaps in Landsat ETM+ SLC-off images. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 1053–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoran, M.A.; Zoran, L.F.V.; Dida, A.I. Forest vegetation dynamics and its response to climate changes. In Remote Sensing for Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Hydrology XVIII.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2016, 9998, 598–608. [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, A.; Kolhe, S.; Kamal, R. An improved random forest classifier for multi-class classification. Inf. Process. Agric. 2016, 3(4), 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, P.; Foody, G.M.; Herold, M.; Stehman, S.V.; Woodcock, C.E.; Wulder, M.A. Good practices for estimating area and assessing accuracy of land change. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 148, 42–57. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, C.; Schmidt, T.; Conrad, C.; Kleinschmit, B.; Forster, M. Grassland habitat mapping by intra-annual time series analysis—Comparison of RapidEye and TerraSAR-X satellite data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2015, 34, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahler, A.H.; Boschetti, L.; Foody, G.M.; Friedl, M.A.; Hansen, M.C.; Herold, M.; Mayaux, P.; Morisette, J.T.; Woodcock, C.E. Global Land Cover Validation: Recommendations for Evaluation and Accuracy Assessment of Global Land Cover Maps; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson, P.; Foody, G.M.; Stehman, S.V.; Woodcock, C.E. Making better use of accuracy data in land change studies: Estimating accuracy and area and quantifying uncertainty using stratified estimation. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 129, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Qu, M.; Wang, C.; Zhao, J.; Cao, Y. Quantifying landscape pattern and ecosystem service value changes: A case study at the county level in the Chinese Loess Plateau. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 23, e01110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; Wang, C.; Wang, K.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y. Spatial and temporal changes of landscape patterns and their effects on ecosystem services in the Huaihe River Basin, China. Land 2022, 11, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarigal, K. FRAGSTATS Help; University of Massachusetts: Amherst, MA, USA, 2015; 182p. [Google Scholar]

- Fahrig, L. Habitat fragmentation: A long and tangled tale. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2019, 28, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, N.M.; Brudvig, L.A.; Clobert, J.; Davies, K.F.; Gonzalez, A.; Holt, R.D.; Townshend, J.R. Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth’s ecosystems. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, M.C.; Potapov, P.V.; Moore, R.; Hancher, M.; Turubanova, S.A.; Tyukavina, A.; Townshend, J.R. High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science 2013, 342(6160), 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, J.; Ceulemans, R.; Salvador-Van, E.D. Decision tree algorithm for detection of spatial processes in landscape transformation. Environ. Manag. 2004, 33, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Haulleville, T.; Rakotondrasoa, O.L.; Rakoto Ratsimba, H.; Bastin, J.F.; Brostaux, Y.; Verheggen, F.J.; Rajoelison, G.L.; Malaisse, F.; Poncelet, M.; Haubruge, É.; et al. Fourteen years of anthropization dynamics in the Uapaca bojeri Baill. Forest of Madagascar. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2018, 14, 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Yang, X. A hierarchical approach to forest landscape pattern characterization. Environ. Manag. 2012, 49, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lausch, A.; Herzog, F. Applicability of landscape metrics for the monitoring of landscape change: Issues of scale, resolution and interpretability. Ecol. Indic. 2002, 2, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, J.; Vranken, I.; André, M. Anthropogenic effects in landscapes: Historical context and spatial pattern. In Biocultural Landscapes: Diversity, Functions and Values; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2014; pp. 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- TV, R.; Setturu, B.; Chandran, S. Geospatial analysis of forest fragmentation in Uttara Kannada District, India. Forest Ecosyst. 2016, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Pardo, J.; Saura, S.; Insaurralde, A.; Di Bitetti, M.S.; Paviolo, A.; De Angelo, C. Much more than forest loss: Four decades of habitat connectivity decline for Atlantic Forest jaguars. Landscape Ecol. 2023, 38, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellmes, M.; Udelhoven, T.; Röder, A.; Sonnenschein, R.; Hill, J. Dryland observation at local and regional scale—Comparison of Landsat TM/ETM+ and NOAA AVHRR time series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 2111–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelmann, J.E.; Gallant, A.L.; Shi, H.; Zhu, Z. Perspectives on monitoring gradual change across the continuity of Landsat sensors using time-series data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 185, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsevski, V.; Kasischke, E.; Dempewolf, J.; Loboda, T.; Grossmann, F. Analysis of the impacts of armed conflict on the Eastern Afromontane forest region on the South Sudan—Uganda border using multitemporal Landsat imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 118, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koy, J.K.; Wardell, D.A.; Mikwa, J.F.; Kabuanga, J.M.; Monga Ngonga, A.M.; Oszwald, J.; Doumenge, C. Dynamics of deforestation in the Yangambi biosphere reserve (Democratic Republic of Congo): Spatial and temporal variability in the last 30 years. Bois For. Trop. 2019, 341, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Khoji, M.H.; Nghonda, D.-d.N.; Kalenda, F.M.; Strammer, H.; Kankumbi, F.M.; Malaisse, F.; Bastin, J.-F.; Sikuzani, Y.U.; Bogaert, J. Mapping and Quantification of Miombo Deforestation in the Lubumbashi Charcoal Production Basin (DR Congo): Spatial Extent and Changes between 1990 and 2022. Land 2023, 12, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwitwa, J.; German, L.; Muimba-Kankolongo, A.; Puntodewo, A. Governance and sustainability challenges in landscapes shaped by mining: Mining-forestry linkages and impacts in the Copper Belt of Zambia and the DR Congo. Forest Policy Econ. 2012, 25, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneibel, A.; Stellmes, M.; Röder, A.; Frantz, D.; Kowalski, B.; Haß, E.; Hill, J. Assessment of spatio-temporal changes of smallholder cultivation patterns in the Angolan Miombo belt using segmentation of Landsat time series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 195, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenta, A.A.; Yasuda, H.; Haregeweyn, N.; Belay, A.S.; Hadush, Z.; Gebremedhin, M.A.; Mekonnen, G. The dynamics of urban expansion and land use/land cover changes using remote sensing and spatial metrics: The case of Mekelle City of northern Ethiopia. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 38, 4107–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinario, G.; Hansen, M.; Potapov, P.; Tyukavina, A.; Stehman, S. Contextualizing landscape-scale forest cover loss in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) between 2000 and 2015. Land 2020, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpanda, M.M.; Muteya, H.K.; Nghonda, D.-D.N.; Sambiéni, K.R.; Malaisse, F.; Kaleba, S.C.; Bogaert, J.; Sikuzani, Y.U. Uncontrolled Exploitation of Pterocarpus tinctorius Welw. and Associated Landscape Dynamics in the Kasenga Territory: Case of the Rural Area of Kasomeno (DR Congo). Land 2022, 11, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinario, G.; Hansen, M.C.; Potapov, P.V. Forest cover dynamics of shifting cultivation in the Democratic Republic of Congo: A remote sensing-based assessment for 2000–2010. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 094009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barima, Y.S.S.; Kouakou, A.T.M.; Bamba, I.; Sangne, Y.C.; Godron, M.; Andrieu, J.; Bogaert, J. Cocoa crops are destroying the forest reserves of the classified forest of Haut-Sassandra (Ivory Coast). Global Ecol. Conserv. 2016, 8, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni, Y.S.; André, M.; Mahy, G.; Kaleba, S.C.; Malaisse, F.; Kankumbi, F.M.; Bogaert, J. Interprétation paysagère du processus d’urbanisation à Lubumbashi: Dynamique de la structure spatiale et suivi des indicateurs écologiques entre 2002 et 2008. In Anthropisation des Paysages Katangais; Presses Agronomiques de Gembloux: Gembloux, Belgium, 2018; 281p. [Google Scholar]

- Trefon, T.; Hendriks, T.; Kabuyaya, N.; Ngoy, B. L’économie politique de la filière du charbon de bois à Kinshasa et à Lubumbashi: Appui stratégique à la politique de reconstruction post-conflit en RDC. IOB, GIZ, University of Antwerp, 2010.

- Alemagi, D.; Nukpezah, D. Assessing the performance of large-scale logging companies in countries of the Congo Basin. Environ. Nat. Resour. Res. 2012, 2, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, C.; Mayaux, P.; Verhegghen, A.; Bodart, C.; Christophe, M.; Defourny, P. National forest cover change in Congo Basin: Deforestation, reforestation, degradation and regeneration for the years 1990, 2000 and 2005. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2013, 19, 1173–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonarakis, A.S.; Pacca, L.; Antoniades, A. The effect of financial crises on deforestation: A global and regional panel data analysis. Sustainability Sci. 2022, 17, 1037–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabulu, D.J.-P.; Vranken, I.; Bastin, J.-F.; Malaisse, F.; Nyembwe, N.S.; Useni, S.Y.; Ngongo, L.M.; Bogaert, J. Approvisionnement En Charbon de Bois Des Ménages Lushois: Quantités, Alternatives et Conséquences. In Anthropisation des Paysages Katangais; Bogaert, J., Colinet, G., Mahy, G., Eds.; Presses Universitaires de Liège: Liège, Belgium, 2018; pp. 297–311. [Google Scholar]

- Mukendi, N.K.; Muteya, H.K.; Nghonda, D.D.N.T.; Berti, F.; Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Ndjibu, L.N.; Bogaert, J. Quantification and Determinants of Carbonization Yield in the Rural Zone of Lubumbashi, DR Congo: Implications for Sustainable Charcoal Production. Forests 2024, 15, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, J.; Bamba, I.; Koffi, K.J.; Sibomana, S.; Djibu, J.P.K.; Champluvier, D.; Visser, M.N. Fragmentation of forest landscapes in Central Africa: Causes, consequences and management. In Patterns and Processes in Forest Landscapes: Multiple Use and Sustainable Management; Lafortezza, R., Chen, J., Sanesi, G., Crow, T.R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2008; pp. 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, R.; Taubert, F.; Müller, M.S.; Groeneveld, J.; Lehmann, S.; Wiegand, T.; Huth, A. Accelerated forest fragmentation leads to critical increase in tropical forest edge area. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabg7012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’tambwe Nghonda, D.-D.; Muteya, H.K.; Kashiki, B.K.W.N.; Sambiéni, K.R.; Malaisse, F.; Sikuzani, Y.U.; Kalenga, W.M.; Bogaert, J. Towards an Inclusive Approach to Forest Management: Highlight of the Perception and Participation of Local Communities in the Management of miombo Woodlands around Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, D.R. Congo). Forests 2023, 14, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni, S.Y.; Mpanda Mukenza, M.; Khoji Muteya, H.; Cirezi Cizungu, N.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J. Vegetation Fires in the Lubumbashi Charcoal Production Basin (The Democratic Republic of the Congo): Drivers, Extent and Spatiotemporal Dynamics. Land 2023, 12, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Khoji Muteya, H.; Langunu, S.; Gerardy, A.; Bogaert, J. Amplification of anthropogenic pressure heavily hampers natural ecosystems regeneration within the savanization halo around Lubumbashi city (Democratic Republic of Congo). Int. J. Environ. Sci. Nat. Resour. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mama, A.; Bamba, I.; Sinsin, B.; Bogaert, J.; De Cannière, C. Déforestation, savanisation et développement agricole des paysages de savanes-forêts dans la zone soudano-guinéenne du Bénin. Bois For. Trop. 2014, 322, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mama, A.; Sinsin, B.; De Cannière, C.; Bogaert, J. Anthropisation et dynamique des paysages en zone soudanienne au nord du Bénin. Tropicultura 2013, 31, 78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Rakotondrasoa, O.L.; Malaisse, F.; Rajoelison, G.; Gaye, J.; Razafimanantsoa, T.M.; Rabearisoa, M.; Bogaert, J. Identification des indicateurs de dégradation de la forêt de tapia (Uapaca bojeri) par une analyse sylvicole. Tropicultura 2013, 31, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Boisson, S.; Cabala Kaleba, S.; Nkuku Khonde, C.; Malaisse, F.; Halleux, J.M.; Munyemba Kankumbi, F. Dynamique de l’occupation du sol autour des sites miniers le long du gradient urbain-rural de la ville de Lubumbashi, RD Congo. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2020, 24, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banza, C.L.N.; Nawrot, T.S.; Haufroid, V.; Decrée, S.; De Putter, T.; Smolders, E.; Nemery, B. High human exposure to cobalt and other metals in Katanga, a mining area of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Environ. Res. 2009, 109, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzito, G.; Ibanda, P.A.; Talaguma, R.; Lusanga, N.M. Slash-and-burn agriculture, the major cropping system in the region of Faradje in Democratic Republic of Congo: Ecological and socio-economic consequences. J. Dev. Agric. Econ. 2020, 12, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montfort, F.; Nourtier, M.; Grinand, C.; Maneau, S.; Mercier, C.; Roelens, J.B.; Blanc, L. Regeneration capacities of woody species biodiversity and soil properties in Miombo woodland after slash-and-burn agriculture in Mozambique. For. Ecol. Manage. 2012, 274, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni, S.Y.; Mpanda, M.M.; Malaisse, F.; Kaseya, P.K.; Bogaert, J. The Spatiotemporal Changing Dynamics of Miombo Deforestation and Illegal Human Activities for Forest Fire in Kundelungu National Park, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Fire 2023, 6, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, C.; Dubiez, É.; Proces, P.; Diowo, M.; Yamba, Y.; Mutambwe, S.; Doucet, J.L. Enjeux fonciers, exploitation des ressources naturelles et Forêts des Communautés Locales en périphérie de Kinshasa, RDC. Biotechnologie, Agronomie, Société et Environnement 2011, 15, 651–661. [Google Scholar]

- Phiri, D.; Mwitwa, J.; Ng’andwe, P.; Kanja, K.; Munyaka, J.; Chileshe, F.; Kwenye, J.M. Agricultural expansion into forest reserves in Zambia: A remote sensing approach. Geocarto International 2023, 38, 2213203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimobe, K.; Ouédraogo, A.; Soma, S.; Goetze, D.; Porembski, S.; Thiombiano, A. Identification of driving factors of land degradation and deforestation in the Wildlife Reserve of Bontioli (Burkina Faso, West Africa). Global Ecology and Conservation 2015, 4, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, E.O.; Macgregor, C.J.; Sloan, S.; Sayer, J. Deforestation is driven by agricultural expansion in Ghana’s forest reserves. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Tropical Deforestation, Accra, Ghana, 15–17 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chitonge, H.; Mfune, O. The Urban Land Question in Africa: The Case of Urban Land Conflicts in the City of Lusaka, 100 Years after Its Founding. Habitat Int. 2015, 48, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Kipili Mwenya, I.; Khoji Muteya, H.; Malaisse, F.; Cabala Kaleba, S.; Bogaert, J. Anthropogenic Pressures and Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Forest Ecosystems in the Rural and Border Municipality of Kasenga (DRC). Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2024, 20, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasereka, K.K.; Mweru, J.P. Gouvernance environnementale de la ville de Butembo par les services publics urbains (Nord-Kivu, République Démocratique du Congo). Tropicultura 2018, 36, 578–592. [Google Scholar]

- Kaswamila, A.L.; Songorwa, A.N. Participatory Land-Use Planning and Conservation in Northern Tanzania Rangelands. Afr. J. Ecol. 2009, 47, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butsic, V.; Baumann, M.; Shortland, A.; Walker, S.; Kuemmerle, T. Conservation and conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo: The impacts of warfare, mining, and protected areas on deforestation. Biological Conservation 2015, 191, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majambu, E.; Tsayem Demaze, M.; Sufo-Kankeu, R.; Sonwa, D.J.; Ongolo, S. The effects of policy discourse on the governance of deforestation and forest degradation reduction in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Environmental Policy and Governance 2023, 34, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.E.; Callaham, M.A.; Stewart, J.E.; Warren, S.D. Invasive Species Response to Natural and Anthropogenic Disturbance. Invasive Species in Forests and Rangelands of the United States: A Comprehensive Science Synthesis for the United States Forest Sector 2021, 85-110. [CrossRef]

- Stanturf, J.A. Restoration of boreal and temperate forests; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Boldrini, S. Guide technique. Plantation agroforestière d’Acacia auriculiformis dans le Haut-Katanga. Master’s Thesis, University of Lubumbashi, Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey, P.; Baghai, M.; Bigurube, G.; Cunliffe, S.; Dickman, A.; Fitzgerald, K.; Robson, A. Attracting Investment for Africa’s Protected Areas by Creating Enabling Environments for Collaborative Management Partnerships. Biological Conservation 2021, 255, 108979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisiaux, F.; Peltier, R.; Muliele, J.C. Plantations industrielles et agroforesterie au service des populations des plateaux Batéké, Mampu, en République Démocratique du Congo. Bois Forêts Trop. 2009, 301, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramiadantsoa, T.; Ovaskainen, O.; Rybicki, J.; Hanski, I. Large-scale habitat corridors for biodiversity conservation: A forest corridor in Madagascar. PLoS ONE 2015, 10(7), e0132126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havyarimana, F.; Masharabu, T.; Kouao, J.K.; Bamba, I.; Nduwarugira, D.; Bigendako, M.J.; De Canniere, C. La dynamique spatiale de la forêt située dans la réserve naturelle forestière de Bururi au Burundi. Tropicultura 2017, 35, 158–172. [Google Scholar]

- Zikargae, M.H.; Woldearegay, A.G.; Skjerdal, T. Empowering rural society through non-formal environmental education: An empirical study of environment and forest development community projects in Ethiopia. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bare, M.; Kauffman, C.; Miller, D.C. Assessing the impact of international conservation aid on deforestation in sub-Saharan Africa. Environmental Research Letters 2015, 10, 125010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoji, M.H.; Mokuba, H.K.; Sambieni, K.R.; Sikuzani, Y.U.; Moyene, A.B.; Bogaert, J. Évaluation de la dynamique spatiale des forêts primaires au sein du Parc national de la Salonga sud (RD Congo) à partir des images satellites Landsat et des données relevées in situ. VertigO-la revue électronique en sciences de l’environnement 2024, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Mapira, J. Zimbabwe’s Environmental Education Programme and its implications for sustainable development. Doctoral Dissertation, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Galabuzi, C.; Eilu, G.; Nabanoga, G.N.; Turyahabwe, N.; Mulugo, L.; Kakudidi, E.; Sibelet, N. Has the evolution process of forestry policies in Uganda promoted deforestation? International Forestry Review 2015, 17, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoji, M.H.; Mpanda, M.M. , Mwenya, I.K.; Malaisse, F.; Mukendi, N.K.; Bastin, J.F.; Bogaert, J.; Useni, S.Y. Protected area creation and its limited effect on deforestation: Insights from the Kiziba-Baluba Hunting Domain (DR Congo). Trees, Forests and People 2024, 18, 100654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, B.; Mullard, S.; Ahamadi, K.; Mara, P.; Mena, J.; Nourdine, S.; Maraina, A.V. (Re) Interpreting corruption in local environments: Disputed definitions, contested conservation, and power plays in Northern Madagascar. Political Geography 2023, 107, 102973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Territory | Area (km²) | Population | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lubudi | 18939 | 387000 | Economic activities include mining (artisanal and industrial), agriculture, and trade. The region is home to the rural municipality of Fungurume and the historic city of Bunkeya. Additionally, the territory encompasses the Hunting Domain of Mulumbu (993.56 km²), and it is electrified with some paved roads. |

| Mutshatsha | 18859 | 1268500 | Mining, agriculture, and commerce are key activities in this area, which includes the city of Kolwezi, the capital of the Province. The territory is home to the Hunting Domain and Reserve of Basse Kando (479.18 km²), as well as the Tshangalele Reserve (523.52 km²). The territory is electrified and has some paved roads. |

| Sandoa | 25337 | 765400 | Agriculture and commerce thrive in this area. The territory, which lacks electricity and paved roads, is home to the Lunda-Tshokwe Hunting Domain (2345.27 km²) and the Mwene-Kay Reserve (531.33 km²). |

| Kapanga | 25509 | 1255600 | Agriculture and commerce flourish in the territory, which is without electricity and paved roads. It is home to the Tshikamba Hunting Domain (4857.21 km²). |

| Dilolo | 25648 | 623,500 | Agriculture and commerce are prominent in this area, which includes the city of Kasaji. The territory, lacking electricity and paved roads, is home to the Mwene Musoma Hunting Domain (1303.99 km²). |

| 1990-1995 | FR | SV | AG | BBS | OT | FR Loss | SV Gain | AG Gain | BBS Gain |

| PA [%] | 99.00 | 94.42 | 98.99 | 98.00 | 100 | 96.04 | 98.04 | 97.98 | 95.06 |

| UA [%] | 99.01 | 100 | 98.00 | 97.09 | 98.97 | 99.00 | 99.01 | 98.98 | 100 |

| F1 [%] | 99.00 | 97.13 | 98.49 | 97.54 | 99.48 | 97.50 | 98.52 | 98.48 | 97.47 |

| Overall accuracy [%] | 95.60 | ||||||||

| 1995-2001 | FR | SV | AG | BBS | OT | FR Loss | SV Gain | AG Gain | OT Gain |

| PA [%] | 93.58 | 100 | 98.05 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 95.88 | 100 | 100 |

| UA [%] | 97.14 | 100 | 99.01 | 99.03 | 96.08 | 96.3 | 89.42 | 99.03 | 96.08 |

| F1 [%] | 95.33 | 100.00 | 98.53 | 99.51 | 98.00 | 98.12 | 92.54 | 99.51 | 98.00 |

| Overall accuracy [%] | 98.40 | ||||||||

| 2001-2006 | FR | SV | AG | BBS | OT | FR Loss | SV Gain | AG Gain | OT Gain |

| PA [%] | 97.02 | 100 | 96.04 | 98.04 | 97.98 | 95.06 | 100 | 98.9796 | 93.578 |

| UA [%] | 99.02 | 98.97 | 99 | 99.01 | 98.98 | 100 | 99.0196 | 96.0396 | 97.1429 |

| F1 [%] | 98.01 | 99.48 | 97.50 | 98.52 | 98.48 | 97.47 | 99.51 | 97.49 | 95.33 |

| Overall accuracy [%] | 96.61 | ||||||||

| 2006-2010 | FR | SV | AG | BBS | OT | FR Loss | SV Gain | AG Gain | OT Gain |

| PA [%] | 98.06 | 99.03 | 100 | 98.04 | 100 | 100 | 99.03 | 97.8 | 97.35 |

| UA [%] | 98.54 | 100 | 99 | 100 | 98.02 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.1 |

| F1 [%] | 98.30 | 99.51 | 99.50 | 99.01 | 99.00 | 100.00 | 99.51 | 98.89 | 98.22 |

| Overall accuracy [%] | 98.30 | ||||||||

| 2010-2015 | FR | SV | AG | BBS | OT | FR Loss | SV Gain | AG Gain | OT Gain |

| PA [%] | 98 | 96 | 98.11 | 98.1 | 100 | 100 | 98.04 | 97.98 | 97.06 |

| UA [%] | 97.09 | 98.06 | 99.05 | 99.04 | 98.99 | 95.1 | 99.01 | 98.98 | 100 |

| F1 [%] | 97.54 | 97.02 | 98.58 | 98.57 | 99.49 | 97.49 | 98.52 | 98.48 | 98.51 |

| Overall accuracy [%] | 98.91 | ||||||||

| 2015-2020 | FR | SV | AG | BBS | OT | FR Loss | SV Gain | AG Gain | OT Gain |

| PA [%] | 99.09 | 100 | 98.97 | 93.58 | 100 | 98.05 | 100 | 98.06 | 93.58 |

| UA [%] | 100 | 99.02 | 96.04 | 97.14 | 100 | 99.01 | 97.06 | 98.06 | 97.14 |

| F1 [%] | 99.54 | 99.51 | 97.48 | 95.33 | 100.00 | 98.53 | 98.51 | 98.06 | 95.33 |

| Overall accuracy [%] | 97.51 | ||||||||

| 2020-2024 | FR | SV | AG | BBS | OT | FR Loss | SV Gain | AG Gain | OT Gain |

| PA [%] | 100 | 98.04 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 98.08 |

| UA [%] | 100 | 100 | 98.02 | 100 | 98.02 | 100 | 100 | 99.06 | 98.08 |

| F1 [%] | 100.00 | 99.01 | 99.00 | 100.00 | 99.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 99.53 | 98.08 |

| Overall accuracy [%] | 98.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).