1. Introduction

Receptor-interacting serine threonine kinase 1 (RIPK1) is involved in various pathways of inflammation, which is downstream of tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNFR1), Toll-like receptors (TLRs), as well as correlated with interferon [

1]. It is a multifunctional protein involved in regulating cell death, and plays an important role in necroptosis [

2]. In addition, RIPK1 has emerged as a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of a wide range of human neurodegenerative, and autoimmune diseases [

2]. RIPK1 is also involved in skin inflammation, and activation of RIPK1 is reportedly correlated with many skin diseases, including melanoma, psoriasis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and hair loss [

3,

4]. Many molecules can modulate the ubiquitination of RIPK1, and RIPK1 inhibitors can ameliorate skin and hair diseases [

3].

Apoptosis and autophagy are forms of programed cell death and reportedly involved in hair regeneration [

5,

6]. For example, apoptosis of the outer root sheath (ORS) plays a key role in the hair follicle (HF) regression (catagen phase) [

7,

8]. Increased autophagy is detected upon anagen entry during the natural HF cycle, and small molecules that activate autophagy stimulated hair growth [

6]. In addition, alopecia areata (AA) patients have copy number deletions in region spanning the ATG4B gene, and impaired autophagy promoted hair loss in the C3H/HeJ mouse model of AA [

9]. However, unlike apoptosis and autophagy, the involvement of necroptosis or RIPK1 expression during the hair cycle progression is not well-known. We first investigated the effects RIPK1 in hair cycle progression, and RIPK1 was highly expressed in ORS cells during the hair regression period [

4]. RIPK1 inhibitors such as Necrostatin-1s (Nec-1s) induced the ORS cell proliferation and migration, and increased the HF length in mouse and pig organ cultures. In addition, RIPK1 inhibitors enhanced the telogen-to-anagen transition in animal model. Recently, Jang et al. examined whether or not necroptosis is associated with the pathogenesis of AA, however, mRNA and protein expressions of RIPK1 and RIPK3 were not upregulated in the skin lesions of patients with AA [

10]. On the contrary, we prepared AA mouse model via lymph node cell injection and performed single cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) that mRNA level of RIPK1 is increased. Therefore, we investigated in the present study whether RIPK1 is involved in AA pathology and RIPK1 inhibitors could attenuate AA progression in AA animal model.

2. Results

2.1. Increased Expression of RIPK1 in AA Mouse Skin

The C3H/HeN mouse model of AA was generated by transplanting skin-draining lymph node (SDLN) cells from an AA donor onto a naïve C3H/HeN recipient. This model demonstrates high concordance with human AA and has been widely used in translational studies [

11,

12,

13,

14]. To comprehensively profile the mechanism underlying AA, we performed droplet-based scRNA-seq on single cell isolated from AA and normal C3H/HeN mouse. We obtained transcriptomic profiles of 14,469 cells passed primary quality control filter. Using t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) and the subsequent clustering approach, we identified 20 cell clusters from scRNA-seq data (

Figure 1A).

Interestingly, the expression amount of the RIPK1 gene in AA is higher than in C3H/HeN mice without hair loss. Notably, there was a significant increase in RIPK1 expression in the T cell (TC) and dendritic cell/macrophage (DC/Mac) subpopulations within the immune cell groups (

Figure 1A and B). We also observed a higher level of RIPK1 mRNA in lesional skin with AA than in skin from normal mice (

Figure 1C), consistent with our scRNA-seq analysis. To validate this finding, we further showed the increased protein expression of RIPK1 in DC and CD8

+ T cell in AA model (

Figure 1D and E). However, RIPK3 and MLKL mRNA expression are very low and up-regulated in T cells, but not in DCs (

Figure S1). These results suggest that both necroptosis and apoptosis are involved, and RIPK1 play a key role in AA progression.

2.2. Nec-1s Prevented Disease Onset of AA

We investigated the role of RIPK1 in AA pathogenesis by RIPK1 signaling blockade. Nec-1s has been used to inhibit RIPK1 activation when administrated in vivo [

15,

16]. C3H/NeH mice were treated with Nec-1s starting on the 3 days of allogenic SDLN cells transplantation to induce AA (

Figure 2A). Nec-1s-treated mice showed delayed hair loss (

Figure 2B,C). The role of RIPK1 in AA development was further confirmed by comparing the frequencies of skin-infiltrating CD8

+ T cells. Flow cytometry analysis of skin cell suspensions further revealed that CD8

+ T cell among skin CD45

+ immune cells were significantly reduced in Nec-1s-treated mice (

Figure 2D). Consistent with FACS, Nec-1s substantially reduced the staining of CD8

+ cells in the skin (

Figure 2E). We next analyzed the changes of DCs by CD11c

+ cells in the skin. Nec-1s treatment significantly reduced the numbers of DCs compared to control (

Figure 2F).

2.3. GSK2982772 Prevented Disease Onset of AA

We further investigated the prevention effects of other RIPK1 inhibitor (GSK2982772) As expected, GSK2982772-treated mice showed delayed hair loss than control mice (

Figure 3B,C). Flow cytometry analysis of skin cell suspensions further revealed that CD8

+ T cell among skin CD45

+ immune cells were significantly reduced in GSK2982772-treated mice (

Figure 3D). GSK2982772 substantially reduced the staining of CD8

+ cells in the skin (

Figure 3E). GSK2982772 treatment also significantly reduced the numbers of DCs compared to control (

Figure 3F). Collectively, these results indicated that endogenous RIPK1 plays a pivotal role in AA development.

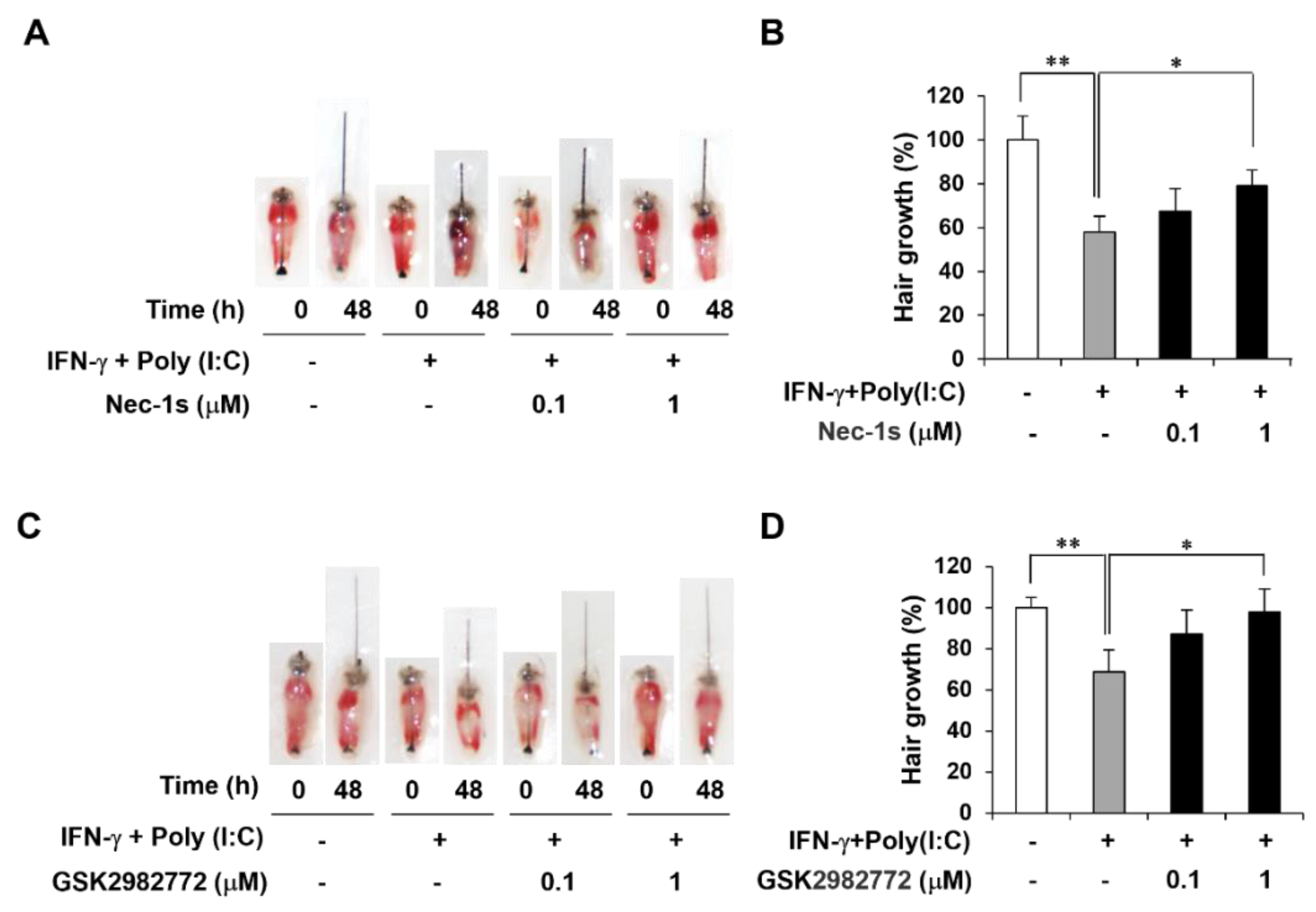

2.4. RIPK1 Inhibitors Decrease AA-Like Symptoms in Mouse Vibrissa Follicle

It has been reported that interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid [poly(I:C)] induced AA mimicking condition, and we established a mouse vibrissa organ culture model ex vivo [

17]. We then investigated whether RIPK1 inhibitor treatment affects length of mouse vibrissa follicle. Mouse vibrissa follicles had been isolated and cultured with IFN-γ and Poly(I:C) with RIPK1 inhibitors for 2 days. Images of follicles were taken on day 0 and day 2 (

Figure 4A,C). As expected, IFN-γ and Poly(I:C) induction retarded hair shaft growth, which was attenuated by RIPK1 inhibitors such as Nec-1s and GSK2982772 (

Figure 4B,D).

3. Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the involvement of RIPK1 in AA progression. mRNA and protein expression of RIPK1 was increased in the skin of AA mouse model. scRNA-seq and immunohistochemistry showed that RIPK1 is highly increased in DCs and CD8+ T cells. RIPK1 inhibitors delayed the onset of AA in mouse model, and reduced the CD8+ T cells and DCs in AA skin. RIPK1 inhibitors also increased the hair length in the mouse hair organ culture. Collectively, these results suggest that RIPK1 is involved in AA onset, and RIPK1 inhibition could prevent AA.

Expression and involvement of RIPK1 in regulating hair cycle has been demonstrated that RIPK1 was up-regulated in hair regression period to induce hair loss [

4,

18]. However, involvement of RIPK1 in AA has not been well-reported. Jang et al. examined whether or not necroptosis is associated with the pathogenesis of AA, but RIPK1 and RIPK3 mRNA and protein expressions were not upregulated in the skin lesions of AA patients [

10]. In that study, they collected human scalp skin samples and analyzed the whole skin cells and could not find the difference in necroptosis-related genes. In mouse AA model, we performed scRNA-seq that RIPK1 expression increased in DCs, T cells in addition to dermal fibroblasts and keratinocytes. In addition, RIPK1 inhibitors reduced the immune cells such as DCs add CD8

+ T cells in the AA skin to prevent AA onset. However, RIPK3 and MLRK expression are very low and up-regulated in T cells, but not in DCs (

Figure S1). These results suggest that both necroptosis and apoptosis are involved, and RIPK1 play a key role in AA progression.

AA is due to the loss of immune privilege, leading to autoimmune attack, and many studies have reported the key immune cells responsible for HF damage [

19]. Recently, functional interrogation of lymphocyte subsets in AA was analyzed in mice and humans using scRNA-seq, and it was found that CD8

+ T cells are the predominant AA-driving cell type [

20]. In this study, AA onset in mice was induced by lymph node cell injection, resulting in significant increases of CD8

+ T cells leading to hair loss. Conversely, injection of RIPK1 inhibitors significantly reduced CD8

+ T cells in the skin, delaying AA onset. However, RIPK1 inhibitor did not inactivate T cells in response to PHA simulation (

Figure S2), which suggest that they do not directly inhibit T cell activation.

Dying cells initiate adaptive immunity by providing both antigens and inflammatory stimuli for DCs, which in turn activate CD8

+ T cells through a process called antigen cross-priming [

21]. To explain in detail, iDCs detect and phagocyte incoming pathogens in peripheral tissue, and activated iDCs leave the site of infection and migrate into lymph nodes. [

22]. Then, iDCs fully differentiate into mDC, and they present antigens to naïve T cells to activation [

23]. Although we did not further investigate the CD8

+ T cell activation by mDCs during AA progression, RIPK1 inhibitors such as Nec-1s and GSK2982772 significantly reduced the maturation of iDCs in vitro (

Figure S3). These results suggest that RIPK1 inhibitors could prevent of AA onset via inhibiting DC maturation and CD8

+ T cell priming.

Chronic inflammatory and autoinflammatory diseases are caused by immune dysregulation, and RIPK1 has emerged as key regulators of immunity via their integral roles in cell death signaling following exposure to inflammatory and infectious stimuli [

24]. Therefore, RIPK1 is involved in autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel disease [

25,

26,

27]. In addition to these autoimmune diseases, we first demonstrated the involvement of RIPK1 in AA progression and possibility of RIPK1 inhibitors in AA prevention.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Preparation of Single-Cell Suspension

Skin samples were collected from C3H/HeN mice and AA model mice. To ensure sufficient cell yield, skin from the back of 7-8 mice per group was pooled, finely minced, and digested with a 0.7 mg/mL collagenase D solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). The resulting cell mixture was then filtered through 70 μm and 40 μm meshes, and cellular debris was eliminated via density gradient centrifugation using Percoll media (Sigma).

4.2. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

The single-cell suspensions were processed following the Chromium Next GEM Sin-gle Cell 3’ RNA Library v3.1 protocol (10x Genomics) in accordance with the manufactur-er’s guidelines. In brief, individual cells were encapsulated into nanoliter-scale Gel Beads-in-Emulsion (GEMs) that contained barcoded oligonucleotides. The poly(dT) pri-mers within these GEMs selectively captured polyadenylated mRNA from each cell, al-lowing for the synthesis of barcoded, full-length cDNA. This cDNA was then amplified and used to construct 3’ gene expression libraries. Sequencing of these libraries was per-formed on an Illumina platform at Macrogen. The subsequent analysis, including read alignment to the mouse reference genome (mm10), filtering, barcode counting, and unique molecular identifier (UMI) counting, was performed using the Cell Ranger v7.2.0 (10x Ge-nomics) count pipeline. The sequenced reads have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession number GSE269455 (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE269455).

4.3. Single-Cell Transcriptome Analysis

Initial processing was performed using the Seurat v5.0.3 R package, which included cell filtering, clustering, and annotation, as previously detailed [

28,

29]. Cells exhibiting over 10% mitochondrial gene expression or expressing fewer than 200 genes were excluded from the analysis, resulting in a total of 14,469 skin cells across two groups (C3H and AA). Potential doublets were identified and removed using DoubletFinder v2.0.4 with default settings [

30]. After quality control, the count matrix was normalized, and 2,000 most variable genes were selected for further scaling. The dimensionality reduction was then performed using t-SNE. Cell clusters were manually annotated based on marker gene expression.

For example, basal interfollicular epidermis (IFE_B) cells were annotated using Krt5 and Krt14 as markers, while suprabasal IFE (IFE_S) cells were identified by the expression of Krt1 and Krt10. Cycling basal IFE (IFE_BC) cells were marked by Krt5, Krt14, Stmn1, and Mki67. Upper hair follicle (uHF) cells were characterized by Krt17 and Krt79, whereas se-baceous gland (SG) cells were annotated using Scd1 and Mgst1. Outer bulge (OB) cells were identified by the expression of Barx. Hair follicle keratinocytes were categorized based on Krt27 and Krt35 expression and further subdivided into germinative layer (IB_G), inner root sheath & medulla (IB_IM), and cortex/cuticle (IB_C) cells, depending on the ex-pression of proliferative markers like Stmn1.

Fibroblast-like cells were differentiated into dermal fibroblasts (DF) based on Col1a1 and Lum expression, and dermal papilla cells (DPC) were identified by the expression of Corin and Notum. Immune cells were classified according to their specific marker genes: T cells (TC, Cd3e), gamma-delta T cells (gdTC, Trdc), monocytes (Mono, Cd14 and Ccl6), dendritic cells & macrophages (DC/Mac, Cd68 and Cd74), Langerhans cells (LC, Cd207), and B cells (BC, Cd79a). Additionally, skeletal muscle cells (SkM, Acta1 and Des) and mel-anocytes (Mel, Pmel and Dct) were also identified based on their characteristic gene ex-pression profiles.

4.4. Animals

Male mice aged 4 weeks (vibrissae organ culture) and female mice aged 9 weeks (AA animal model) from the C3H/HeN strain were procured from Orient Bio Co. Ltd. (Sungnam, Republic of Korea). All animal studies were carried out with the approval of the Animal Care and Use Committee at the International Medical Center, adhering to ethical guidelines to minimize suffering and ensure the wellbeing of the animals.

4.5. Alopecia Areata Animal Model

The AA mice model was induced by transferring in vitro-expanded skin-draining lymph node (SDLN) cells from AA-affected mice as previously described [

31,

32]. In brief, SDLN cells were extracted from mice that had spontaneously developed AA and cultured in advanced RPMI 1640 (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco), 2 mM GlutaMAX (Gibco), and 100 U/mL penicillin–streptomycin (Hyclone, South Logan, UT, USA). The culture medium was further supplemented with IL-2 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), IL-7 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), and IL-15 (R&D Systems). The cells were stimulated using Dynabeads Mouse T-Activator CD3/CD28 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and intradermally transferred to at least 10-week-old C3H/HeN female mice with a normal hair coat during the second telogen phase.

4.6. Flow Cytometry Analysis

Mouse skin tissue was harvested into collagenase type 4 (3 mg/ml, Worthington, Lakewood, NJ, USA) with DNase I (5 μg/ml, Roche) and chopped into small fragments. Samples were incubated at 37 °C for 90 min then filtered through 70 μm mesh followed by 40 μm mesh. For live/dead staining, the Zombie NIR fixable viability kit (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for 10 min. To block nonspecific binding, cells were incubated with a CD16/CD32 antibody (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) for 10 min. For surface staining, the cells were labeled with the following antibodies: FITC anti-CD8 and PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-CD45 (BioLegend). The samples were acquired using CytoFLEX (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL, USA), and the data were analyzed with CytExpert software (version 2.4.0.28).

4.7. RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis, Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR), and PCR Array

Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by reverse transcription using a cDNA synthesis kit (Nanohelix, Dae-jeon, Korea). qRT-PCR was performed using the QuantSrudio1 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems/Thermo Fisher Scientific). The primer sequences used were as follows (forward and reverse, respectively): 5′-GACTGTGTACCCTTACCTCCGA-3′ and 5′-CACTGCGATCATTCTCGTCCTG-3′ for RIPK1; 5′-CATCACTGCCACCCAGAAGACTG-3′ and 5′-ATGCCAGTGAGCTTCCCGTTCAG-3′ for GAPDH.

4.8. Immunostaining

For immunofluorescence studies of mouse skin, 5 μM formalin fixed and paraffin skin section were used. After heating antigen retrieval skin section were stained with primary antibodies including: anti-RIPK1 (Novus Biologicals, Novus Biologicals), anti-CD11c (Santa Cruze Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA)., anti-CD8 (Santa Cruze Biotechnology). Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-Rabbit or goat anti-Mouse antibody was used as secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Immunofluorescence images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse Ts2 microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

4.9. Hair Organ Culture

The hair growth activity of mouse vibrissae was observed during organ culture. The mouse vibrissae were isolated and cultured according to the method previously described by Jindo and Tsuboi [

33]. Normal anagen vibrissae HFs were obtained from the upper lip region using a scalpel and forceps. Isolated HFs were placed in a defined medium (Williams E medium supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 µg/mL insulin, 10 ng/mL hydrocortisone, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin, without serum). Individual vibrissa HFs were photographed 48 h after the start of the incubation. Changes in hair length were calculated from the photographs and expressed as the mean ± standard error (SE) of 10-12 vibrissae HFs.

4.10. Statistical Analysis

All data are demonstrated as the means ± standard deviations of at least three independent experiments. For the analysis between two groups, Student’s t-test was used. Log-rank tests were used to analyze the hair loss curves. When more than two groups were compared, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used. The significance values were set as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001. GraphPad Prism 5.01 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was used for all statistical analysis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Expression profile of RIPK3 and MLKL in the AA mouse model.; Figure S2. The effect of RIPK1 inhibitor in T cell activation.; Figure S3: The effect of RIPK1 inhibitors in DC activation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J-H.S. and M.Z.; Investigation, H.K., S.A. and I.G.P.; Data Curation, J-H.S., M.Z. and H.K.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, H.K.; Writing – Review & Editing, J-H.S. and M.N.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: RS-2024-00351858).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Yonsei University (IACUC-A-202302-1636-01).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mifflin, L.; Ofengeim, D.; Yuan, J., Receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1) as a therapeutic target. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2020, 19, (8), 553-571. [CrossRef]

- Degterev, A.; Ofengeim, D.; Yuan, J., Targeting RIPK1 for the treatment of human diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, (20), 9714-9722. [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Liu, P.; Yin, M.; Zhang, M.; Kuang, Y.; Zhu, W., RIPK1: A rising star in inflammatory and neoplastic skin diseases. J Dermatol Sci 2020, 99, (3), 146-151. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Choi, N.; Jang, Y.; Kwak, D. E.; Kim, Y.; Kim, W. S.; Oh, S. H.; Sung, J. H., Hair growth promotion by necrostatin-1s. Sci Rep 2020, 10, (1), 17622.

- Sun, P.; Wang, Z.; Li, S.; Yin, J.; Gan, Y.; Liu, S.; Lin, Z.; Wang, H.; Fan, Z.; Qu, Q.; Hu, Z.; Li, K.; Miao, Y., Autophagy induces hair follicle stem cell activation and hair follicle regeneration by regulating glycolysis. Cell Biosci 2024, 14, (1), 6. [CrossRef]

- Chai, M.; Jiang, M.; Vergnes, L.; Fu, X.; de Barros, S. C.; Doan, N. B.; Huang, W.; Chu, J.; Jiao, J.; Herschman, H.; Crooks, G. M.; Reue, K.; Huang, J., Stimulation of Hair Growth by Small Molecules that Activate Autophagy. Cell Rep 2019, 27, (12), 3413-3421 e3. [CrossRef]

- Lindner, G.; Botchkarev, V. A.; Botchkareva, N. V.; Ling, G.; van der Veen, C.; Paus, R., Analysis of apoptosis during hair follicle regression (catagen). Am J Pathol 1997, 151, (6), 1601-17.

- Botchkareva, N. V.; Ahluwalia, G.; Shander, D., Apoptosis in the hair follicle. J Invest Dermatol 2006, 126, (2), 258-64. [CrossRef]

- Gund, R.; Christiano, A. M., Impaired autophagy promotes hair loss in the C3H/HeJ mouse model of alopecia areata. Autophagy 2023, 19, (1), 296-305. [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y. H.; Jin, M.; Moon, S. Y.; Eun, D. H.; Lee, W. J.; Lee, S. J.; Kim, M. K.; Kim, S. H.; Kim do, W., Investigation on the role of necroptosis in alopecia areata: A preliminary study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016, 75, (2), 436-9.

- Xing, L.; Dai, Z.; Jabbari, A.; Cerise, J. E.; Higgins, C. A.; Gong, W.; de Jong, A.; Harel, S.; DeStefano, G. M.; Rothman, L.; Singh, P.; Petukhova, L.; Mackay-Wiggan, J.; Christiano, A. M.; Clynes, R., Alopecia areata is driven by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and is reversed by JAK inhibition. Nat Med 2014, 20, (9), 1043-9. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Chen, J.; Chang, Y.; Christiano, A. M., Selective inhibition of JAK3 signaling is sufficient to reverse alopecia areata. JCI Insight 2021, 6, (7). [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Wang, E. H. C.; Petukhova, L.; Chang, Y.; Lee, E. Y.; Christiano, A. M., Blockade of IL-7 signaling suppresses inflammatory responses and reverses alopecia areata in C3H/HeJ mice. Sci Adv 2021, 7, (14). [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Kim, M. H.; Park, S. G.; Kim, W. S.; Oh, S. H.; Sung, J. H., CXCL12 Neutralizing Antibody Promotes Hair Growth in Androgenic Alopecia and Alopecia Areata. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, (3). [CrossRef]

- Harris, P. A.; Berger, S. B.; Jeong, J. U.; Nagilla, R.; Bandyopadhyay, D.; Campobasso, N.; Capriotti, C. A.; Cox, J. A.; Dare, L.; Dong, X.; Eidam, P. M.; Finger, J. N.; Hoffman, S. J.; Kang, J.; Kasparcova, V.; King, B. W.; Lehr, R.; Lan, Y.; Leister, L. K.; Lich, J. D.; MacDonald, T. T.; Miller, N. A.; Ouellette, M. T.; Pao, C. S.; Rahman, A.; Reilly, M. A.; Rendina, A. R.; Rivera, E. J.; Schaeffer, M. C.; Sehon, C. A.; Singhaus, R. R.; Sun, H. H.; Swift, B. A.; Totoritis, R. D.; Vossenkamper, A.; Ward, P.; Wisnoski, D. D.; Zhang, D.; Marquis, R. W.; Gough, P. J.; Bertin, J., Discovery of a First-in-Class Receptor Interacting Protein 1 (RIP1) Kinase Specific Clinical Candidate (GSK2982772) for the Treatment of Inflammatory Diseases. J Med Chem 2017, 60, (4), 1247-1261.

- Degterev, A.; Huang, Z.; Boyce, M.; Li, Y.; Jagtap, P.; Mizushima, N.; Cuny, G. D.; Mitchison, T. J.; Moskowitz, M. A.; Yuan, J., Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic potential for ischemic brain injury. Nat Chem Biol 2005, 1, (2), 112-9.

- Shin, J. M.; Choi, D. K.; Sohn, K. C.; Koh, J. W.; Lee, Y. H.; Seo, Y. J.; Kim, C. D.; Lee, J. H.; Lee, Y., Induction of alopecia areata in C3H/HeJ mice using polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (poly[I:C]) and interferon-gamma. Sci Rep 2018, 8, (1), 12518. [CrossRef]

- Morgun, E. I.; Pozdniakova, E. D.; Vorotelyak, E. A., Expression of Protein Kinases RIPK-1 and RIPK-3 in Mouse and Human Hair Follicle. Dokl Biochem Biophys 2020, 494, (1), 252-255. [CrossRef]

- Zeberkiewicz, M.; Rudnicka, L.; Malejczyk, J., Immunology of alopecia areata. Cent Eur J Immunol 2020, 45, (3), 325-333. [CrossRef]

- Lee, E. Y.; Dai, Z.; Jaiswal, A.; Wang, E. H. C.; Anandasabapathy, N.; Christiano, A. M., Functional interrogation of lymphocyte subsets in alopecia areata using single-cell RNA sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2023, 120, (29), e2305764120.

- Yatim, N.; Jusforgues-Saklani, H.; Orozco, S.; Schulz, O.; Barreira da Silva, R.; Reis e Sousa, C.; Green, D. R.; Oberst, A.; Albert, M. L., RIPK1 and NF-kappaB signaling in dying cells determines cross-priming of CD8(+) T cells. Science 2015, 350, (6258), 328-34.

- Varga, Z.; Racz, E.; Mazlo, A.; Korodi, M.; Szabo, A.; Molnar, T.; Szoor, A.; Vereb, Z.; Bacsi, A.; Koncz, G., Cytotoxic activity of human dendritic cells induces RIPK1-dependent cell death. Immunobiology 2021, 226, (1), 152032. [CrossRef]

- Clatworthy, M. R.; Aronin, C. E.; Mathews, R. J.; Morgan, N. Y.; Smith, K. G.; Germain, R. N., Immune complexes stimulate CCR7-dependent dendritic cell migration to lymph nodes. Nat Med 2014, 20, (12), 1458-63. [CrossRef]

- Speir, M.; Djajawi, T. M.; Conos, S. A.; Tye, H.; Lawlor, K. E., Targeting RIP Kinases in Chronic Inflammatory Disease. Biomolecules 2021, 11, (5). [CrossRef]

- Jhun, J.; Lee, S. H.; Kim, S. Y.; Ryu, J.; Kwon, J. Y.; Na, H. S.; Jung, K.; Moon, S. J.; Cho, M. L.; Min, J. K., RIPK1 inhibition attenuates experimental autoimmune arthritis via suppression of osteoclastogenesis. J Transl Med 2019, 17, (1), 84. [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, N.; Huang, Y.; Jin, Z.; Zhang, S.; Ming, Z.; Chen, H., Inhibition of keratinocyte necroptosis mediated by RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL provides a protective effect against psoriatic inflammation. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, (2), 134.

- Garcia-Carbonell, R.; Yao, S. J.; Das, S.; Guma, M., Dysregulation of Intestinal Epithelial Cell RIPK Pathways Promotes Chronic Inflammation in the IBD Gut. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 1094. [CrossRef]

- Stuart, T.; Butler, A.; Hoffman, P.; Hafemeister, C.; Papalexi, E.; Mauck, W. M., 3rd; Hao, Y.; Stoeckius, M.; Smibert, P.; Satija, R., Comprehensive Integration of Single-Cell Data. Cell 2019, 177, (7), 1888-1902 e21.

- Lee, K. J.; An, S.; Kim, M. Y.; Kim, S. M.; Jeong, W. I.; Ko, H. J.; Yang, Y. M.; Noh, M.; Han, Y. H., Hepatic TREM2(+) macrophages express matrix metalloproteinases to control fibrotic scar formation. Immunol Cell Biol 2023, 101, (3), 216-230. [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, C. S.; Murrow, L. M.; Gartner, Z. J., DoubletFinder: Doublet Detection in Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Data Using Artificial Nearest Neighbors. Cell Syst 2019, 8, (4), 329-337 e4. [CrossRef]

- Wang, E. H. C.; Khosravi-Maharlooei, M.; Jalili, R. B.; Yu, R.; Ghahary, A.; Shapiro, J.; McElwee, K. J., Transfer of Alopecia Areata to C3H/HeJ Mice Using Cultured Lymph Node-Derived Cells. J Invest Dermatol 2015, 135, (10), 2530-2532. [CrossRef]

- Wang, E. H. C.; McElwee, K. J., Nonsurgical Induction of Alopecia Areata in C3H/HeJ Mice via Adoptive Transfer of Cultured Lymphoid Cells. Methods Mol Biol 2020, 2154, 121-131.

- Jindo, T.; Imai, R.; Takamori, K.; Ogawa, H., Organ culture of mouse vibrissal hair follicles in serum-free medium. J Dermatol 1993, 20, (12), 756-62. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).