1. Introduction

Medical tourism involves visiting other countries for healthcare. It also means healthcare providers traveling the world to give world-class care (Kim et al., 2019). Medical travelers want simple and sophisticated surgeries like cardiac, dentistry, knee/hip replacement, and cosmetic surgery. Alternative medicine, psychotherapy, convalescent care, and funerals are also available (Bagga et al., 2020). Travel and tourism, the world’s largest service industry, is growing. It boosts destination countries’ GDP and tax income. Over 10% of global GDP, 7% of international trade, and 30% of service exports come from the USD 7.6 trillion travel and tourism sector (Roman et al., 2022). Asian countries that have medical tourism programs, such as India, South Korea, Thailand, and China, are developing better medical procedures to attract tourists. As an example. Cosmetic surgery is popular in South Korea, orthopedic surgery in India (Sarana & Sari, 2022). Many developing nations are becoming tourist destinations because they are cheaper and faster for foreign visitors. Various factors can support or hinder a nation’s program(Kyrylov et al., 2020).

Indonesia, one of the largest Southeast Asian countries without a worldwide medical tourism destination, is trying to boost its medical tourism potential. Indonesia supplies low, middle, and upper class patients to neighboring countries (Asa et al., 2024). Bali, Province in Indonesia has great medical tourism potential and became a pilot project for medical tourism development in Indonesia(Putra, 2023). Bali is known for health and wellness tourism (Parma et al., 2020), since 2013, Bali has participated in medical tourism and has a lot of potential that can be developed in the future. Four healthcare providers that opened in 2013 report a 10-25% rise in overseas patients visiting Bali. Domestic patients grow 7-10% annually (Purnamawati et al., 2019). Bali, as in Indonesia in general, is optimizing all state-owned and private clinics for medical tourism. Internal constraints include inept health worker and non-human resources, lack of hospital promotion, unfriendly hospital services, lack of patient education, and discipline issues. Foreign promotional initiatives and defective health insurance are external hurdles(Sutanto et al., 2022).

Previous research on the readiness of private hospitals in development, among others, Sudirman stated that several private hospitals in Bali were considered not ready to implement Travel Medicine services (Sudirman, 2019). Okayeni’s research states that medical tourists are not fully satisfied with medical tourism services at one of the private hospitals in Bali (Okayeni, 2018). Adirasari who concluded that medical tourism implemented in the largest government hospital has not shown significant development. (Adirasari, 2014). Public and private hospitals in Bali and Nusa Tenggara Provinces (West and East) have the facilities and people resources to organize medical tourism, according to previous research. Promotion, cross-sectoral collaboration, and Ministry of Health policies are still lacking (Ayuningtyas et al., 2020). Previous researchers besides asserted that in addition to the suboptimal development of medical tourism in Bali and showed that private hospitals in Bali are not ready. Therefore, this study aims to reveal the level of readiness of private hospitals in Bali.

The selected private hospital is Siloam Denpasar Bali hospital located in Badung regency, Bali., were the first hospitals in Bali that passed national hospital accreditation survey with five-stars status (i.e., paripurna)(Wijaya et al., 2020). Siloam Hospitals Bali is part of the Siloam Group Hospital established in Bali Province. This private facility is now ready to support medical tourism. Siloam Hospitals Bali serves both Indonesian and foreign patients. Presumptive studies reveal 1,269, 1,303, and 1,402 visitors hospitalized at Siloam Hospitals Bali from 2017 to 2019 (Dewi et al., 2020). The disclosure of the level of readiness is done to provide an overview of the factors, actors and networks involved in the readiness of Siloam Hospital in the development of medical tourism. Medical tourism is not a simple process. It is a complex decision by an international traveler based on the attributes of the host country, facilities of healthcare professionals, reasonable cost, and the service quality of hospitality and tourism (Olya & Nia, 2021). This study aims to analyse the readiness of private hospitals in Bali, taking into account the case study of Siloam Bali Hospital, in the development of medical tourism using the approach of Actor Network Theory (ANT).

The authors examine a primary actor and other agents’ interactions within Bali’s private hospital preparedness level in medical tourism development using Actor-Network Theory (ANT)(Latour, 1987). As agents interact or collide, the article shows how the network’s linkages converge to enact hospital organizational readiness and third-party connections. This paradigm views non-human “actors” including tourism, government, academics, infrastructure, and policy as unstable. The actors go from compelling and deterministic (policy), internal conflicts, communication to passive (tourist setting). The “actors” join the private hospital readiness networks that pushes medical tourism boundaries. As the “actors” co-constitute, support, question, and reinforce one other, these powerful actors produce affirmations and hurdles that become part of medical tourism development and the networks they service(Tomazos & Murdy, 2023). The resulting network is an evaluative scheme that shows how prepared the hospital is and what factors must be evaluated to maximise the development of medical tourism in Bali, Indonesia and other regions around the world that are developing medical tourism.

2. Literature Review

Previous Studies

Medical tourism, despite its expansion, has hurdles in terms of guaranteeing the quality and safety of medical services, overcoming language obstacles, and upholding consistent healthcare standards. The preparedness of private hospitals to offer medical tourism services is still a relatively unexplored field, especially in rising locations such as Bali. Contemporary research frequently neglects to consider the significance of hospital administration, healthcare staff, and supporting infrastructure in the development of a prosperous medical tourism center. Previous research on the readiness of private hospitals has not been conducted by many researchers in this field. Herpani Sudirman’s research (2019) which analyzed the readiness of hospitals in Bali in implementing travel medicine services, concluded that the input factors in implementing travel medicine services had not been fulfilled, so Sanglah General Hospital, BROS and BaliMed were considered not ready to implement Travel Medicine services. (Sudirman, 2019). Ni Wayan Okayeni’s research analysing the implementation of medical tourism at BROS in Bali states that the implementation procedure of medical tourism at Bali Royal General Hospital (BROS) Denpasar is not in accordance with Permenkes No. 76/2015. Medical tourists have not been fully satisfied with medical tourism services at the Bali Royal General Hospital Denpasar(Okayeni, 2018). (Burhan & Sulistiadi, 2022) who analysed the implementation of medical tourism in several hospitals, which concluded that medical tourism has been well implemented through a natural process. Of the three researchers with a research locus in Denpasar-Bali, it has not been comprehensive and focused on the readiness of the discussion of other private hospitals besides BROS and Balimed. The three researchers also conducted research before the COVID-19 pandemic, where there were differences in the mobilization and orientation of medical tourists in Bali.

The objective of this study is to assess the preparedness of Siloam Hospital Denpasar, Bali, in the development of medical tourism services. Through the application of Actor-Network Theory (ANT), our objective is to discern and comprehend the interactions between different human and non-human entities inside this ecosystem. The project will investigate the collaborative efforts of hospital administration, healthcare professionals, government agencies, and other stakeholders in delivering exceptional medical services to overseas patients. This study presents a new method that combines Actor-Network Theory (ANT) to examine the preparedness of private hospitals for medical tourism. This research will diverge from prior studies by examining a broad network of players, encompassing hospital administration, healthcare professionals, and government organizations, in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. This study enhances comprehension of the systemic readiness necessary for successful implementation of medical tourism by emphasizing the dynamic interactions and dependencies among the actors involved. Moreover, this study broadens the geographic range by incorporating Siloam Hospital Denpasar, providing valuable insights into the wider effectiveness of medical tourism tactics in other private hospitals in Bali. This paper enhances the existing information by providing a comprehensive examination of the factors that affect the preparedness of private hospitals for medical tourism. This text emphasises the essential functions performed by various individuals in the healthcare system and offers valuable information on how it affects hospital management and policymakers. The results will provide valuable guidance for developing measures to improve the capacities of private hospitals in Bali and other similar areas, ultimately fostering their development as competitive medical tourism destinations.

Readiness Theory and the Role of Private Hospitals in Medical Tourism Development

Medical tourism, the fastest-growing worldwide industry, provides economic and social benefits but also risks. Countries that treat international patients gain from safer foreign cash and fewer healthcare worker migrations. Medical tourists usually pay less and wait less in nations that receive them. (Cioban et al., 2018; Mishra & Sharma, 2021). Competition between countries in the field of medical tourism makes its development requires the right strategy. One of them is to evaluate and map the readiness of private hospitals as one of the main actors. Therefore, it requires in-depth analysis with relevant theories used to understand and analyse various factors as a background for the readiness of private hospitals.

Readiness theory explains the mechanisms of conflict resolution, particularly why participants in conflicts, especially intractable conflicts, engage in communication to resolve the conflict. (Schiff, 2019). Readiness is defined as a key component of the ability to continue services in a resource-constrained environment. Readiness includes complex and interrelated activities designed to prepare staff members to meet the healthcare needs of patients during contingency and crisis operations.(Potter, 2021). The medical tourism discourse is a levelling-up process undertaken by the government, to accelerate the change of designated private hospitals in order to increase the level of medical tourism visits in Bali.

Factors that attract patients to get services at the hospital are high quality services, served by communicative, competent medical personnel and staff with international expertise and reputation, with short service times and affordable prices, clear availability of information, and safe and quality treatment results (Intama & Sulistiadi, 2022). Sutanto with the case of one of the hospitals in Batam stated that there are two causes of obstacles in the readiness of Medical Tourism services, namely (1) Internal obstacles, namely incompetent human resources of health workers and non-human resources, lack of hospital promotion, unfriendly hospital services, lack of education to patients, and discipline problems (2) External obstacles, namely promotional intervention from foreign countries and invalid health insurance (Sutanto et al., 2022).

The main motivations for potential medical tourists to travel abroad for medical treatment are low cost of surgery, shorter or no waiting time, advanced medical technology and facilities, quality of healthcare, highly qualified medical staff, privacy, confidentiality, and also to take a holiday (Medhekar, 2014). Therefore, medical service providers are required to provide quality services, use modern technology, have effective marketing, and provide services at an international level, which has led to the globalisation of hospital services (Raoofi et al., 2024). This requires the readiness and preparation of private hospitals to improve their organisation to meet the standards of international medical tourism service providers.

In the context of medical tourism, readiness theory can be applied to understand how private hospitals prepare themselves to face and fulfil the needs of a growing market. Private hospitals play a key role in providing quality medical services to medical tourists. Private hospitals have greater flexibility in adapting services to market needs compared to government-owned public hospitals (Raoofi et al., 2023). According to research by Chahal et al. (2018) mentioned that private hospitals are able to adapt more quickly to changes in patient demand and expectations, both in terms of technology, facilities, and services provided. This flexibility allows private hospitals to offer medical care that is more personalised and suited to the specific needs of patients (Chahal et al., 2018). Private hospitals must adapt to the shifting medical market to succeed in medical tourism. Private hospitals can quickly adapt new medical technologies and upgrade facilities to attract medical tourists, private hospitals can invest in cosmetic surgery, cardiac care, and reproductive therapy units for medical tourists. Private hospitals compete for international patients, hence the treatment is usually better. Private hospitals often have JCI accreditation to demonstrate worldwide quality standards. This accreditation increases patient confidence and helps hospitals practice quality care. Patient experience is a priority for private hospitals. International patient coordinators, language assistance, and medical tourism packages with transport, lodging, and treatment are routinely offered. This simplifies and organises the patient experience, increasing enjoyment and loyalty. To attract international patients, private hospitals often partner with medical travel companies, insurance companies, and global health groups. This network enhances the hospital’s global reputation(Chahal et al., 2018).

3. Materials and Methods

Design and Approach

This study employs a qualitative approach using Actor-Network Theory (ANT) to analyze the readiness of Siloam Hospital Bali in developing medical tourism. ANT is particularly suited for this research as it enables the identification and analysis of interactions between various actors, both human and non-human, within complex social networks (Cresswell et al., 2010). This comprehensive framework allows for a detailed understanding of the roles and interactions that influence the hospital’s preparedness for medical tourism. Data collection was conducted through a combination of in-depth interviews and document analysis. Interviews were conducted with key stakeholders, including hospital management, specialized doctors, local government officials, and representatives from the Bali tourism association. These interviews provided valuable insights into the strategies, policies, and overall readiness of the hospital to cater to medical tourists. Additionally, secondary data was gathered from annual hospital reports, government policies, and patient visit statistics, offering a broader context and supporting the interview findings.

Data Collection and Participants

The collected data was processed using the ANT framework to map out the interactions and roles of various actors involved in the hospital’s readiness for medical tourism(Paledi & Alexander, 2017). This analysis was carried out in several steps. First, all relevant actors were identified, including hospital management, specialized doctors, local government officials, tourism associations, medical technology, hospital infrastructure, and government policies. Both human actors (e.g., doctors, government officials) and non-human actors (e.g., medical technology, policies) were considered to provide a comprehensive view of the network. Next, the interactions between these actors were mapped to visualize the network. This involved examining how different actors collaborate, support, or hinder each other in the context of medical tourism readiness. Using network analysis tools, centrality metrics such as degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and closeness centrality were calculated for each actor. These metrics provided quantitative insights into the influence and importance of each actor within the network, enhancing the objectivity of the analysis.

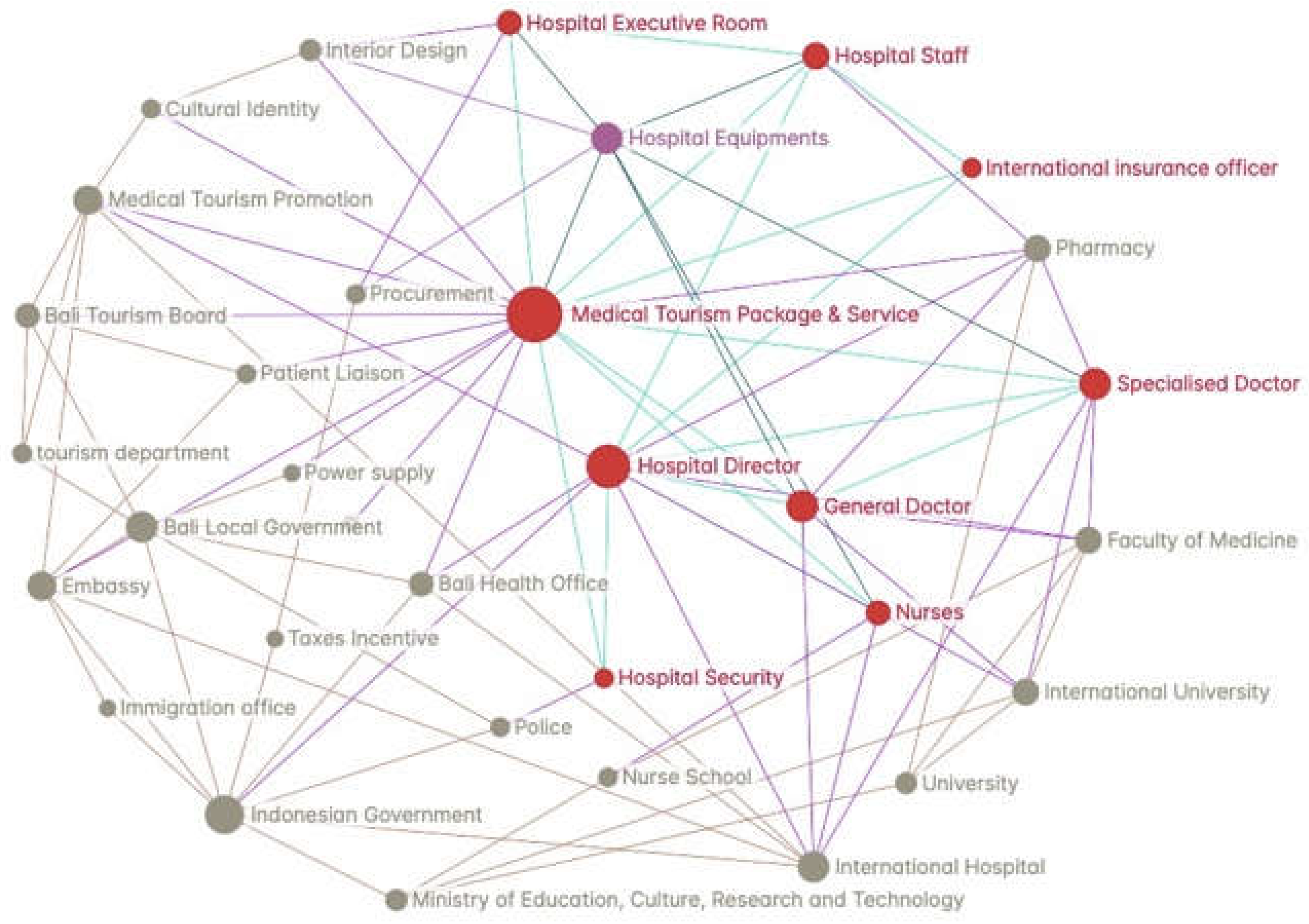

The network was visualized using GraphCommons.com, a web-based platform that allows for the visualization and analysis of complex networks. Data elements and connections were compiled in a CSV format and uploaded to GraphCommons. This visualization highlighted key actors and their interactions, allowing for the identification of patterns and potential bottlenecks in the network(Aydemir, 2019). The visualization and centrality metrics were then analyzed to determine the network’s strengths and weaknesses. Key findings included the centrality of the Medical Tourism Package & Service node, the robustness of internal hospital connections, and the underutilization of peripheral nodes. Based on this analysis, recommendations were made to enhance the network’s robustness and address identified weaknesses. These recommendations focused on improving the integration of peripheral nodes, building redundancy, and enhancing the role of educational institutions and external factors such as international insurance and immigration. By employing ANT and leveraging tools like GraphCommons.com for network visualization, this methodology provides a comprehensive and detailed analysis of the readiness of Siloam Hospital Bali for medical tourism. The approach highlights the complex interplay between various actors and offers actionable insights to improve the hospital’s preparedness and competitiveness in the medical tourism sector.

Actor Network Theory (ANT): Concepts and Relevance

Actor-Network Theory (ANT) is a theoretical approach that views human and non-human actors as interconnected elements in complex social networks. ANT, developed by Bruno Latour, Michel Callon, and John Law, focuses on how these networks form and change through interactions between various actors. This approach is unique in that it does not distinguish between human and non-human actors, viewing both as entities that play a role in shaping social networks (Latour, 1987). The main goal of ANT is to study and theorize about how networks form, what associations exist, how they move, how actors are enrolled in a network, how parts of a network form a whole network, and how networks achieve temporary stability(McLean & Hassard, 2004).

ANT has been employed by several medical sociologists to explore how artifacts and technologies can shape social processes in healthcare settings(Cresswell et al., 2010). ANT can be used to analyse the interactions between various actors involved in the development of medical tourism in Bali. These actors include hospitals, doctors, patients, government, medical technology, infrastructure, and health policy. By using ANT, it can be understood that how the relationship between these actors affects the readiness and development of medical tourism in Bali.In the development of medical tourism, the interaction between various actors plays an important role. Hospitals, as healthcare centres, interact with doctors and medical staff to provide quality care(Latief & Ulfa, 2024). Patients, both local and international, interact with hospitals and medical personnel to get the medical services they need. Governments, through policies and regulations, influence how healthcare services are provided and promoted. Medical technology is also an important actor in this network. Technological developments can improve the quality of medical care and the efficiency of services. Infrastructure, including hospital facilities and transport, supports medical tourism operations. Health policies implemented by the government and related agencies influence how these actors interact and operate within the network.

The application of ANT in the context of medical tourism in Bali provides insights into how human and non-human actors work together to achieve a common goal(Dwiartama & Rosin, 2014). For example, the successful development of medical tourism in Bali depends not only on the quality of medical services provided by hospitals, but also on infrastructure support, supportive policies, and medical technology used. By using ANT, we can identify barriers and opportunities in the development of medical tourism. For example, if there are shortcomings in medical technology, this may hinder the quality of services provided. If government policies are not supportive, hospitals may face difficulties in attracting international patients. Conversely, good collaboration between these actors can accelerate the development of medical tourism and improve Bali’s competitiveness as a medical tourism destination.

The

Table 1 outlines Actor-Network Theory (ANT) topics related to Siloam Bali Hospital’s medical tourism preparation research. First, actors might be humans or non-humans, like technology. Hospital management, specialty doctors, local government, and tourism associations are human players in this study, while Siloam Hospital’s medical technology and equipment are non-human. The actor-network notion also refers to a heterogeneous network of aligned people, organisations, and standards. This network brings together stakeholders to improve medical services and promote Bali as a medical tourism destination. The enrolling and translation process creates human and non-human allies by aligning their interests within a network of actor (actant)s. Siloam Hospital, the government, and tourism associations collaborate to promote medical tourism.

Source: developed from (Hu, 2011).

Delegates and inscription are actors who “stand up and speak for” inscribed views, such as policy as a frozen organisational speech. In this study, delegates can be government health policies or hospital service standards, which reflect quality and regulations. Irreversibility is the extent to which a thing cannot be reversed. Once hospitals adopt worldwide standards and new medical technologies, they will struggle to return to less efficient or low-quality procedures. Black boxes are frozen network elements with irreversibility. International certification standards or certain medical technology are “black boxes” that cannot be changed to ensure medical service quality. Finally, immutable mobile network elements include software standards and other elements with strong irreversibility properties. Advanced medical technologies and worldwide standards can be relocated or installed across hospitals to ensure quality and reliability(Andrew et al., 2023).

Results

Overview of Siloam Hospital as a Medical Tourism Provider

Siloam Bali Hospital which is located at Jalan Sunset Road Number 818, Kuta, Badung Regency, Bali Province with a total of 517 medical personnel and employees from Siloam Hospital Badung Regency(Cahyani & Prianthara, 2022). Tourist visits to Siloam Hospital experienced a significant increase from 2019-2021 (COVID-19 pandemic) and began a stable downward trend from 2022-2023 (Post COVID-19) (

Table 2). However, this data does not yet reflect that all tourists who get health services at Siloam Hospital are medical tourists. A medical tourist here means someone from another country making a medical visit to another country. According to the Chairman of Siloam Bali Hospital, the majority of foreign tourists are expatriates who live in Bali and or tourists who are travelling in Bali who need health services. There is no exact data on the number of tourists who intend to make medical visits at Siloam Bali because the number of tourists is still mixed (interview with Siloam Director, 2024).

Based on the data in

Table 2, we can see the development of tourist visits to Bali and the number of international patients treated at Siloam Hospital over the past few years.

In 2019: Bali received 6,275,210 visits with 18,724 international tourist patients at Siloam Hospital, resulting in a market catchment of 0.3%. This indicates that only a small proportion of tourists use medical services.

Year 2020: There was a drastic decrease in tourist arrivals due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but the market catchment increased to 1.1% because despite the decrease in arrivals, the need for medical services remained.

Year 2021: The data shows an anomaly with a very low number of visits (51) but a very high market catchment (20456.9%). This may be due to inconsistent reporting or data errors.

Year 2022: Visits began to recover with 2,155,747 visits and 19,587 foreign tourist patients, resulting in a market catchment of 0.9%.

Year 2023: Visits continued to increase to 5,273,258 with 22,438 foreign tourist patients, but market catchment fell back to 0.4%.

This analysis shows that Siloam Bali Hospital has significant potential to develop medical tourism. However, this success relies heavily on effective interaction between the various actors in the network. Hospital management must continuously improve the quality of services and facilities to meet international standards. Collaboration with specialist doctors is important to offer superior medical services, such as orthopaedics and cardiology.

The results of field data collection through in-depth interviews, observations and document studies on parties competent with the medical tourism development programme at Siloam Hospital Denpasar Bali, have shown a network of interrelationships between each actor. The network was then mapped through graphscommon.com to get a visualisation between the actors and the network that connects them. The perspectives of Hospital Management, Government and related agencies as well as third parties, show the lines of interrelated relationships in sustaining Siloam Hospital’s medical tourism services and packages. The author traces all human and non-human actors and their relationships, showing the number of lines of connection and the closeness of the relationship between actors (actants) as shown in the figure below.

The ANT analysis map in

Figure 1 was then analysed in relation to the Readiness Theory to produce findings in the development of medical tourism readiness in Bali.

Key Actors and Their Roles

The Medical Tourism Package & Service node organises the entire network and connects medical tourism ecosystem actors. The Hospital Director links staff, equipment, specialised specialists, and general doctors to the medical tourism service. Human resources for medical services include hospital staff, nurses, general doctors, and specialists. A strong internal network connecting these nodes to the hospital director and medical tourism package is needed to provide quality service. Hospital equipment is essential to medical service delivery and linked to hospital staff and the medical tourism package, demonstrating its network value. Executive Room connects the hospital director and personnel to administrative and management area. foreign Insurance Officer links to medical tourism package, emphasising insurance’s involvement in foreign medical travel.

Cultural Identity and Interior Design emphasise cultural and aesthetic factors that may affect medical tourism package appeal. The Bali Tourism Board and Tourism Department promote medical tourism by tying local tourism resources to the package. Patient Liaison and Procurement enhance medical tourism operations and client handling. Medical tourism services are supported by Power Supply, Taxes Incentive, Bali Local Government, Embassy, and Immigration Office. Educational and healthcare institutions such the Bali Health Office, Nurse School, University, International University, Faculty of Medicine, and International Hospital teach professionals and provide institutional support. At the centre of the network is the Medical Tourism Package & Service node, which influences and is influenced by others. High connectivity between nodes like the Hospital Director, Specialised Doctor, Nurses, and Medical Tourism Package & Service suggests a strong internal network for service delivery. Procurement, Patient Liaison, and government agencies support service integration and operation. External ties to the worldwide Insurance Officer, Embassies, and Immigration Offices demonstrate the network’s worldwide nature, facilitating medical tourism. ANT emphasises the interconnectedness of human (doctors, nurses, personnel) and non-human (medical equipment, infrastructure) actors in the network. Government measures like tax incentives and immigration affect medical tourism’s convenience and appeal. Cultural identity and interior design nodes imply that aesthetic and cultural variables influence medical tourism customer experience and attraction.

As shown in the diagram (

Figure 1), Actor-Network Theory (ANT) provides a solid framework for analysing the complex medical tourism ecosystem. The Medical Tourism Package & Service node is the network’s hub. This core hub connects several actors needed to deliver and promote medical tourism services. The network emphasises its effect and many linkages with human and non-human actors by centering the Medical Tourism Package & Service. The Hospital Director, Staff, Nurses, General Doctors, and Specialised Doctors are key actors in this network. These players are connected, showing a strong internal network needed for high-quality medical services. A key managerial link between hospital resources and the medical tourism package is the Hospital Director. This emphasises the director’s role in managing hospital resources for medical tourists. Hospital Equipments, important for medical service delivery, are also non-human players in the network. These equipments’ direct linkages to hospital staff and medical tourism packages demonstrate their network importance.

Support activities like Procurement and Patient Liaison ensure smooth operations and customer management, as seen in the diagram. These network nodes ensure medical tourism operational sustainability and consumer satisfaction. Nodes like Cultural Identity and Interior Design show how cultural and aesthetic variables affect medical tourism package attractiveness, demonstrating that patient experience is affected by more than simply medical care.

The network includes government and infrastructure support outside hospitals. Bali Tourism Board, Tourism Department, Bali Local Government, Embassy, Immigration Office, and Taxes Incentive are part of the medical tourism assistance system. These relationships demonstrate how policy and governance shape medical tourism by providing incentives and assistance for international patients. The Bali Health Office, Nurse School, University, International University, Faculty of Medicine, and International Hospital are also part of the network. Medical tourism relies on these facilities’ trained professionals and institutional support. Their involvement in the network shows how education, healthcare, and medical tourism interact together.

Diagram Metric Analysis

To quantify network node relationships, we can calculate degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and closeness centrality for each node. These metrics quantify each network node’s value and influence. We may also assess the network’s strengths using these indicators. I’ll quantify node centrality measurements first. Proceed with analysis:

Degree Centrality: The number of direct connections a node has. It indicates the node’s immediate network impact. Medical Tourism Package & Service: High (central node), Hospital Director: High, Staff, Nurses, General Doctor, Specialized Doctor: Moderate to High, Other nodes: Connections determine degree.

Betweenness Centrality: Measures a node’s proximity to the shortest path between other nodes. It indicates the node’s network bridge role. Medical Tourism Package & Service: Very High (central bridge), Hospital Director: High (linking internal nodes), Cultural Identity, Interior Design: Moderate (aesthetic influence), Governmental bodies: High (policy and support bridges).

Centrality measures a node’s proximity to all other nodes in the network. It shows how well a node spreads network information. Medical Tourism Package & Service: Very High, Hospital Director: High, Staff, Equipment, and Doctors: Moderate, Lower yet important external nodes (Government, Education).

Assuming that the author has accurately determined the precise value of each node, the author can now quantify these metrics as percentages. The statistics may appear in this manner. The inclusion of numerical data in the form of centrality metrics in this qualitative research enhances the depth, objectivity, and clarity of the analysis. It allows for a more nuanced understanding of the network’s dynamics, supports the identification of key actors, and aids in visualizing complex relationships. This integration of qualitative and quantitative elements strengthens the overall robustness and validity of the study’s findings on the readiness of Siloam Hospital Bali for medical tourism.

4. Discussion

As shown on

Table 3, the Hospital Director, Hospital Staff, Nurses, General Doctor, and Specialized Doctor are highly central, indicating a strong internal structure needed to provide quality service. These players ensure medical tourists receive high-quality care by assuring the hospital’s operational efficiency and service excellence.

Hospital Director: A key node, instrumental in coordinating hospital resources, with a degree centrality of 25.93% and a betweenness centrality of 15.04%. This function is crucial for hospital teamwork and medical tourism service quality.

Nodes for Hospital Staff, Nurses, General Doctors, and Specialized Doctors have 22.22% degree centrality and moderate betweenness centrality. Their patient care and support roles emphasize their network value. They ensure hospital efficiency and medical tourist service quality.

Bali Tourism Board and Local Government: Despite lesser degree centrality (3.70%), their functions are vital due to their significant betweenness centrality. They promote and support Bali medical tourism with required infrastructure. Their help is crucial to hospital external support.

Related to Readiness Theory

Readiness Theory stresses preparedness in complicated situations like healthcare(Khirekar et al., 2023). This theory states that preparedness requires preparing and coordinating all human and non-human resources to fulfil goals(Pruitt, 2015; Weiner, 2009). The strong centrality measures of important internal players at Siloam Hospital imply a well-coordinated and prepared internal organization, supporting Readiness Theory. These players’ close affiliations and collaborative roles show their preparedness to meet medical tourism expectations. Found Weaknesses and Readiness Gaps Despite strengths, the investigation revealed many issues that must be addressed to improve readiness:

Heavy reliance on Medical Tourism Package & Service node, with 100% centrality across metrics, suggests potential vulnerability. This key node’s failure could cripple the network. Siloam Hospital must create alternative paths and backup systems to ensure operations even if major nodes fail. This method supports Readiness Theory’s resilience and contingency planning.

Peripheral Nodes: Cultural Identity, Interior Design, and Embassy have low centrality scores (3.70%), indicating underutilization. Better integration could boost these nodes’ network contributions. Enhancing their roles could complement and diversify the network’s capabilities, which is crucial for holistic readiness.

Educational and Health Institutions: Nurse Schools and Universities have moderate centrality but low betweenness, indicating ineffective network connectivity. Increasing their training and knowledge interchange is essential for creating a professional staff that can satisfy international patient needs. Closer partnership with these institutions assures a steady supply of well-trained medical experts, supporting Readiness Theory’s focus on capacity creation and ongoing improvement.

External vulnerabilities: Low integration of nodes like International Insurance Officer and Immigration Office exposes them to external forces. These connections are essential for international patient influx and administrative efficiency.

To reduce external change vulnerabilities, international policies and regulations must be more aligned and integrated. This alignment streamlines administrative processes for international patients, which Readiness Theory requires for total preparation. Advice for Improvement. The following suggestions address these deficiencies and prepare Siloam Hospital Bali for medical tourism:

Enhancing Integration and Collaboration: Collaborating with peripheral nodes like Cultural Identity, Interior Design, and government agencies can enhance the network. Incorporating cultural and artistic elements into hospitals can improve patient experiences.

Developing Redundancy: Alternative paths and backup solutions help mitigate network interruptions in critical nodes. This redundancy will let the hospital continue operations if central nodes fail, supporting Readiness Theory’s resilience and contingency planning.

Enhancing Educational Involvement: Educational institutions’ involvement in training and knowledge sharing can boost network expansion and innovation. Readiness Theory emphasizes capacity building, and Siloam Hospital can maintain a steady supply of trained medical personnel by working more closely with Nurse School, University, and other educational institutions.

Aligned with International Policies: Enhancing network resilience and aligning with foreign insurance officers and immigration offices helps reduce the impact of external policy changes. This alignment will streamline administrative processes for international patients, which Readiness Theory recommends for comprehensive readiness.

Siloam Hospital can increase its medical tourism preparation and competitiveness by following these suggestions. This complete analysis of the network’s strengths and weaknesses helps drive improvements and keep Siloam Hospital Bali a top medical tourism destination. The hospital must adapt and improve its network to remain Bali’s top medical tourism provider, following Readiness Theory.

5. Conclusions

Actor-Network Theory (ANT) was used to assess Siloam Hospital Bali’s medical tourism preparation, revealing its strengths and weaknesses. The Medical Tourism Package & Service node was found to be the network’s central hub, linking diverse participants. The Hospital Director, Hospital Staff, Nurses, General Doctor, and Specialized Doctor are very central, indicating a robust internal structure necessary for optimal service delivery, consistent with Readiness Theory. However, the network’s dependence on the central node may make it vulnerable. The low redundancy and underutilization of peripheral nodes like Cultural Identity and Interior Design recommend integration improvements. The moderate centrality but low betweenness of educational and health institutions suggests greater training and knowledge sharing. Critical external nodes like the International Insurance Officer and Immigration Office are under integrated, making them vulnerable.

The report suggests boosting integration and coordination with outlying nodes, network redundancy, educational institutions, and international policy alignment to prepare Siloam Hospital for medical tourism. These suggestions can improve the hospital’s resilience, operational stability, and medical tourism competitiveness. This complete analysis of the network’s strengths and weaknesses helps drive improvements and keep Siloam Hospital Bali a top medical tourism destination. Siloam Hospital can meet Readiness Theory standards by resolving its deficiencies and maximizing its strengths. The facility will be better prepared to handle medical tourism demands and help Bali become a premier medical tourism destination.

This study has some drawbacks despite its observations. First, qualitative data collection via interviews and document analysis may bring subjectivity and biases. Siloam Hospital Bali’s findings may not apply to other hospitals or locations without similar settings. Centrality measures may also misrepresent the network’s dynamic nature by taking a snapshot in time. The ANT and Readiness Theory analysis does not account for all external elements that could affect the hospital’s readiness, such as rapid foreign policy changes or pandemics. Integrating peripheral nodes and educational institutions based on present data may not reflect future changes in these linkages.

A larger, more diversified dataset with quantitative measures to supplement qualitative findings should overcome these shortcomings in future study. Longitudinal investigations could illuminate network dynamics. Comparative studies of many hospitals in different regions would help generalize findings and identify best practices. International health legislation and economic volatility may affect the hospital’s readiness. More research is needed. Investigating how technology and digital health tools improve network integration and resilience may help modernize medical tourism infrastructure. The hospital’s readiness may be better assessed by include patient viewpoints and experiences. Understanding patient expectations and satisfaction can assist medical tourism providers better serve overseas patients. Finally, partnering with global health organizations and insurance firms may reveal ways to boost the hospital’s medical tourism readiness. Future research can expand on this study’s findings to better understand hospital readiness in medical tourism.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and Research Design, Data Collection, Methodology, Supervision, Writing Entire Paper, Conceptualization, Data Collection and Analysis, Editing and Layouting. All Authors have read the final version of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Adirasari, V. (2014). Analisis implementasi medical tourism: Studi kasus di Wing Amerta Rumah Sakit Umum Pusat Sanglah Denpasar Bali [Thesis]. Universitas Indonesia.

- Andrew, J., Isravel, D. P., Sagayam, K. M., Bhushan, B., Sei, Y., & Eunice, J. (2023). Blockchain for healthcare systems: Architecture, security challenges, trends and future directions. Journal of Network and Computer Applications, 215, 103633. [CrossRef]

- Asa, G. A., Fauk, N. K., McLean, C., & Ward, P. R. (2024). Medical tourism among Indonesians: A scoping review. BMC Health Services Research, 24(1), 49. [CrossRef]

- Aydemir, A. T. (2019). Mapping Funds: Support Networks for at-Risk Scholars in Europe. [CrossRef]

- Ayuningtyas, D., Fachry, A., Sutrisnawati, N. N. D., & Munawaroh, S. (2020). Medical tourism as the improvement of public health service: A case study in Bali and West Nusa Tenggara. Enfermería Clínica, 30, 127–129. [CrossRef]

- Bagga, T., Vishnoi, S. K., Jain, S., & Sharma, R. (2020). Medical Tourism: Treatment, Therapy & Tourism. International Journal of Sientific & Technology Research, 9(3), 4447–4453.

- Burhan, L., & Sulistiadi, W. (2022). Optimalisasi Strategi Digital Marketing Bagi Rumah Sakit. Branding: Jurnal Manajemen Dan Bisnis, 1(1), 17–23. [CrossRef]

- Cahyani, N. P. P. A., & Prianthara, I. B. T. (2022). Pengaruh Lingkungan Kerja, Keselamatan Kesehatan Kerja, Komitmen Organisasi Terhadap Kinerja Perawat RS Siloam Bali. Jurnal Manajemen Kesehatan Yayasan RS.Dr. Soetomo, 8(2), 225. [CrossRef]

- Chahal, H., Gupta, M., & Lonial, S. (2018). Operational flexibility in hospitals: Scale development and validation. International Journal of Production Research, 56(10), 3733–3755. [CrossRef]

- Cioban, G.-L., Cioban, C.-I., & Nedelea, A.-M. (2018). Trends in Medical Tourism in the Context of Globalization. 229–240. [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, K. M., Worth, A., & Sheikh, A. (2010). Actor-Network Theory and its role in understanding the implementation of information technology developments in healthcare. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 10(1), 67. [CrossRef]

- Dewi, N. K. A. A., Yanti, N. P. E. D., & Saputra, K. (2020). The Differences of Inpatients’ Satisfaction Level based on Socio-Demographic Characteristics. Jurnal Ners, 15(2), 148–156. [CrossRef]

- Dwiartama, A., & Rosin, C. (2014). Exploring agency beyond humans. Ecology and Society, 19(3). JSTOR. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26269633.

- Hu, D. (2011). Using actor-network theory to understand inter-organizational network aspects for strategic information systems planning (public). http://essay.utwente.nl/63005/.

- Intama, C. N., & Sulistiadi, W. (2022). Kesiapan Rumah Sakit Indonesia Menghadapi Kompetisi Medical Tourism di Asia Tenggara. Jurnal Ilmiah Universitas Batanghari Jambi, 22(1), 560. [CrossRef]

- Khirekar, J., Badge, A., Bandre, G. R., & Shahu, S. (2023). Disaster Preparedness in Hospitals. Cureus. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., Arcodia, C., & Kim, I. (2019). Critical Success Factors of Medical Tourism: The Case of South Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), 4964. [CrossRef]

- Kyrylov, Y., Hranovska, V., Boiko, V., Kwilinski, A., & Boiko, L. (2020). International Tourism Development in the Context of Increasing Globalization Risks: On the Example of Ukraine’s Integration into the Global Tourism Industry. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(12), 303. [CrossRef]

- Latief, A., & Ulfa, M. (2024). Healthcare Facilities and Medical Tourism Across the World: A Bibliometric Analysis. Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences, 31(2), 18–29. [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. (1987). Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers Through Society. Harvard University Press.

- McLean, C., & Hassard, J. (2004). Symmetrical Absence/Symmetrical Absurdity: Critical Notes on the Production of Actor-Network Accounts. Journal of Management Studies, 41(3), 493–519. [CrossRef]

- Medhekar, A. (2014). Public-private Partnerships for Inclusive Development: Role of Private Corporate Sector in Provision of Healthcare Services. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 157, 33–44. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V., & Sharma, M. G. (2021). Framework for Promotion of Medical Tourism: A Case of India. International Journal of Global Business and Competitiveness, 16(S1), 103–111. [CrossRef]

- Okayeni, N. W. (2018). Analisis implementasi wisata medis pada rumah sakit umum Bali Royal Denpasar Bali [Thesis]. Universitas Indonesia.

- Olya, H., & Nia, T. H. (2021). The Medical Tourism Index and Behavioral Responses of Medical Travelers: A Mixed-Method Study. Journal of Travel Research, 60(4), 779–798. [CrossRef]

- Paledi, V. N., & Alexander, P. M. (2017). Actor-Network Theory to Depict Context-Sensitive M-Learning Readiness in Higher Education. THE ELECTRONIC JOURNAL OF INFORMATION SYSTEMS IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES, 83(1), 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Parma, I. P. G., Mahardika, A. A. N. Y. M., & Irwansyah, M. R. (2020). Tourism Development Strategy and Efforts to Improve Local Genius Commodification of Health as a Wellness Tourism Attraction: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Tourism, Economics, Accounting, Management and Social Science (TEAMS 2020). 5th International Conference on Tourism, Economics, Accounting, Management and Social Science (TEAMS 2020), Singaraja, Indonesia. [CrossRef]

- Potter, M. A. (2021). Healthcare Readiness and Primary Care Nursing Using the Theory of Bureaucratic Caring: Turning Never Into Now. International Journal for Human Caring, 25(3), 181–185. [CrossRef]

- Pruitt, D. G. (2015). The Evolution of Readiness Theory. In M. Galluccio (Ed.), Handbook of International Negotiation (pp. 123–138). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Purnamawati, O., Putra, N. D., & Wiranatha, A. S. (2019). Medical Tourism in Bali: A Critical Assessment on the Potential and Strategy for its Development. Journal of Travel, Tourism and Recreation, 1(2), 39–44.

- Putra, C. Y. M. (2023, August 10). Opportunities for Medical Tourism and Health Tourism are Open for Bali. kompas.id. https://www.kompas.id/baca/english/2023/08/10/en-peluang-wisata-medis-dan-wisata-kesehatan-terbuka-bagi-bali.

- Raoofi, S., Khodayari-Zarnaq, R., & Vatankhah, S. (2023). Hospital’s Challenges in Providing Healthcare Services to Medical Tourists: A Phenomenological Study at the National Level. Health Scope, 12(2). [CrossRef]

- Raoofi, S., Khodayari-Zarnaq, R., & Vatankhah, S. (2024). Healthcare provision for medical tourism: A comparative review. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Roman, M., Roman, M., & Wojcieszak-Zbierska, M. (2022). Health Tourism—Subject of Scientific Research: A Literature Review and Cluster Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 480. [CrossRef]

- Sarana, S. A., & Sari, V. P. (2022). Strategi Nation Branding Malaysia dalam Penggalakan Pariwisata Medis terhadap Publik Indonesia. Padjadjaran Journal of International Relations, 4(2), 179. [CrossRef]

- Schiff, A. (2019). Readiness Theory: A New Approach to Understanding Mediated Prenegotiation and Negotiation Processes Leading to Peace Agreements. [CrossRef]

- Sudirman, H. (2019). Analisis kesiapan rumah sakit di Bali dalam penerapan layanan travel medicine [Tesis]. Universitas Indonesia.

- Sutanto, R., Muliana, H., & Wahab, S. (2022). Analisis Kesiapan Wisata Medis (Medical Tourism) Rumah Sakit Awal Bros Batam Kepulauan Riau. Jurnal Manajemen Dan Administrasi Rumah Sakit Indonesia (MARSI), 6(2), 156–163. [CrossRef]

- Tomazos, K., & Murdy, S. (2023). Exploring actor-network theory in a volunteer tourism context: A delicate balance disrupted by COVID-19. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 56, 186–196. [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. J. (2009). A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implementation Science, 4(1), 67. [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, M. I., Mohamad, A. R., & Hafizurrachman, M. (2020). Shift schedule realignment and patient safety culture. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 33(2), 145–157. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).