1. Introduction

Children raised on or staying at farms are subject to a high risk of death related to work and non-work fatalities, with tractors contributing a high share of the deaths. Since the mid-20th century, vehicle-/tractor-related child fatalities in farming have been documented in various countries, including the United States [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6], Canada [

7,

8,

9], Australia [

10,

11], New Zealand [

12], Sweden [

13], Italy [

14] Portugal [

15], Spain [

16], and Turkey [

17,

18]. However, documentation of such incidents in other global regions remains limited [

19]. Despite advancements in safety measures, tractor-related accidents in agriculture continue to be alarmingly prevalent, resulting in fatalities and injuries among both adults and children [

20].

Children and elderly male farmers are at the highest risk of tractor-related fatalities [

5,

9,

13,

17,

18,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. The tractor’s age is also important [

16,

21]. The primary types of fatal tractor accidents include rollovers, falls from tractors or attached equipment, runovers, crashes or collisions with motor vehicles, and entanglement in moving or rotating machine parts, particularly power take-off (PTO) shafts. While education, training, and safety equipment such as rollover protection structures (ROPS) and seatbelts are widely recognized as crucial for accident prevention, legal measures are also recommended [

3,

26,

27,

28,

29].

The adoption of tractors in agriculture was gradual in the United States in 1910-1940, influenced by factors such as cost compared to horses, technological advancements, labour costs, and farm scaling [

30,

31]. The first tractor, Avery, produced in the United States, arrived in Iceland in August 1918, and its price was equivalent to the value of the horses it replaced [

32]. The tractor only functioned properly on cultivated land, but a lack of knowledge hampered its use; e.g., initially, the tractor was only used in second gear. Importation of tractors was irregular in the following decades. The Association of Icelandic Cooperatives (SÍS) imported several dozen International 10/20 tractors in 1929–1931. Later, in 1944, the year when Iceland declared its independence from Denmark, 13 tractors of Allis-Chalmers B, so-called home tractors, were imported and one year later, 175 Farmall A tractors [

33]. By 1960, partly due to the Marshall Plan approved by the Iceland Parliament Alþingi in 1948, tractors had become common property among Icelandic farmers [

34,

35].

The widespread adoption of tractors and various agricultural equipment transformed labour demands in rural areas. Icelandic farmers highly regarded their tractors, often assigning them affectionate and humorous nicknames describing their character [

36]. However, the dangers associated with tractors in agricultural work quickly became apparent, particularly for rural children and the so-called summer children, i.e., urban children who stayed on farms during the summer months [

37]. This practice of sending urban children to rural areas during summers began in response to increased migration from rural areas to urban ones in the late 19th century and was widely encouraged by state institutions, especially from 1950 to 1980, but continues to some extent today. The public held the custom in high regard and emphasised the importance of children learning to work on farms and, simultaneously, enjoy nature and breathe clean, fresh air; it became part of being an Icelander [

38].

In Iceland, until 1 July 1958, the legal driving age was 18 years for all vehicles on the main road and off-road. When the Traffic Act no. 26/1958 took effect, from 1 July 1958 to 29 February 1988, the legal age for driving cars and tractors on main roads was 17 years. The minimum age for driving a tractor on the main road with a special licence was 16 years, but there was no age limit for driving tractors off-road. Following debates in the Aþingi, the Traffic Act no. 50/1987 took effect on 1 March 1988. The legal age limit for driving tractors off-road became 13 years and increased to 15 years in 2006 to adapt to European legislation.

The primary objective of this study is to describe and analyse tractor-related fatal accidents in Icelandic agriculture, with a particular focus on children. Specifically, we aim to address the following research questions: 1) To what extent have children been involved in fatal tractor-related accidents in Iceland since the introduction of tractors in 1918? 2) What are the reflections of adults who drove tractors in childhood during their summer stays on farms? 3) How did the tractor-related fatalities influence legislation on the minimum age for off-road tractor driving and the introduction of other safety measures?

2. Materials and Methods

The data presented here was collected as part of the research project “Independent Migration of Icelandic Children in the 20th Century Iceland” [

38,

39]. The project explored the Icelandic custom of sending urban children to stay at farms during the summer months.

2.1. Fatal Tractor-Related Accidents

For this article, we repeated the search for fatal tractor-related accidents for the research project and expanded it to 2024. We also analysed the data again. A fatal tractor-related accident was defined as an incident resulting in death involving a tractor or equipment attached to a tractor (e.g., loaders, mowers, carriers, and PTOs). These accidents were identified through a comprehensive search on timarit.is, an open-access digital library of newspapers and periodicals from Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and Greenland.

The search strategy involved using the Icelandic words for tractor (“dráttarvél” and “traktor”) in combination with “slys” (accident). We compiled a database with all identified accidents and available information. Supplementary data were occasionally obtained through ad hoc contacts with relatives and subsequently confirmed using timarit.is. In memoriam articles commonly published in newspapers were analysed for additional details on victims and accident circumstances.

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP Pro 16.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, US) for Mac. Chi-square tests assessed statistically significant differences (p <0.05) in proportions between groups. Incidence rates and odds ratios were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Incidence rates for fatalities in different age groups were based on population data from Statistics Iceland (hagstofa.is); a child was defined as a person younger than 18 years. The population in Iceland more than quadrupled from 91,368 residents in 1918 to 383,726 in 2024.

2.2. Tractor Driving Narratives

Qualitative data were collected through narrative interviewing [

40] between 2015 and 2017 with 52 individuals who stayed at farms during the summertime in childhood. Participants were selected using purposive sampling to ensure even distribution across gender and age groups [

41].

Interviewees, born between 1918 and 2001, were asked about their experiences driving tractors during farm stays and their knowledge of tractor accidents. All interviews were recorded and analysed using Atlas.ti software [

42].

2.3. Parliamentary Debates

The digital library althingi.is, which includes parliamentary debates, was searched using the keywords “dráttarvél” and “traktor”. Debates focusing on legislation on a minimum age for off-road tractor driving and other preventive measures were selected for analysis. The text was scrutinized for arguments for and against a minimum driving age and other accident prevention measures.

2.4. Ethics

All participants in the qualitative component provided informed verbal consent before the interviews conducted at locations of their choice (primarily their homes) and recorded with permission. Participants were informed of their right to anonymity and to withdraw at any time without reason. The research was approved by the Science Ethics Committee of the University of Iceland (15-005, 29 May 2015).

The use of secondary data on fatal tractor accidents and parliamentary debates, which are publicly accessible, did not require additional ethical approval. Given the sensitive nature of the data, care was taken to omit the names of individual Members of Parliament (MPs), accident victims, and specific accident locations.

3. Results

We divide the presentation of the findings into three sub-sections, i.e., statistical analysis of the tractor-related fatalities, former summer children’s narratives about tractor driving and parliamentary debates about legislation to prevent tractor-related accidents.

3.1. Fatal Tractor-Related Accidents

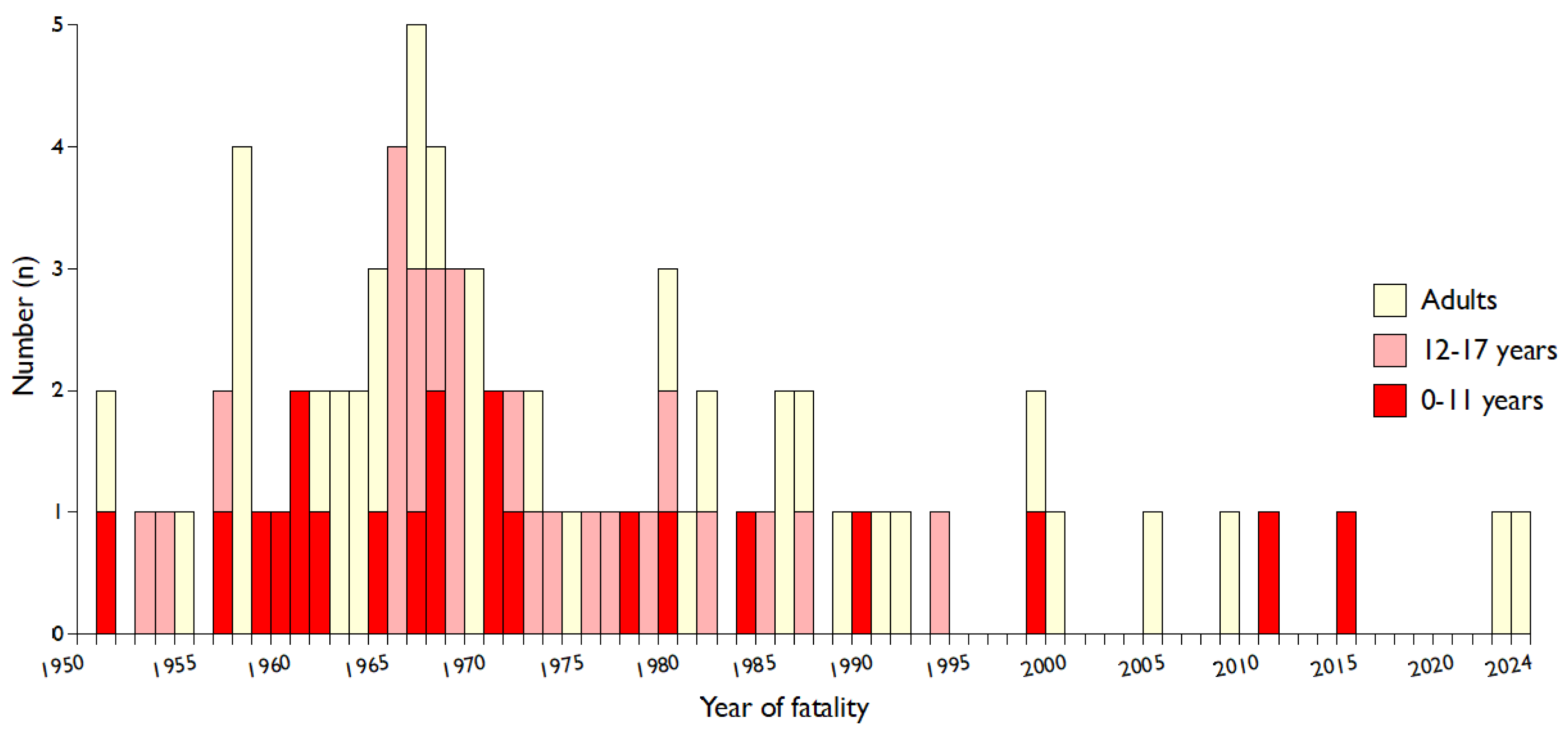

We identified 88 fatal tractor-related accidents from 1918, when the first tractor came to Iceland, to 31 July 2024. The first fatality occurred in 1948 when a tractor overturned with a young worker who was laying an electric cable in an uneven terrain. This accident and three more occurred in workplaces outside the agricultural sector; additional three fatalities involved tractors on the main road without links to agricultural activity. Thus, we identified 81 registered tractor-related fatalities within agriculture during 106 years of tractor usage in Iceland. Almost nine in 10 deaths (88.9%) involved males, and more than half were children (

Table 1).

3.1.1. Incidence Rates

Most of the tractor-related fatalities occurred in the period 1958-1988 (

Table 1); out of the 60 fatalities in the period, 35 (58.3%) involved children. Across all age groups, the incidence in this period was 1.60 times higher than in 1950–1957 and 7.21 times higher than in 1989–2024 (

Table 2). The highest incidence of fatalities occurred among children aged 12–17; it was 10.03 times higher than for adults in 1950–1957 and 4.42 times in 1958–1988 but was at the same level as adults in 1989–2024 (

Table 2). Since 1989, the incidence of tractor fatalities was more than seven times lower compared to the period 1958-1988.

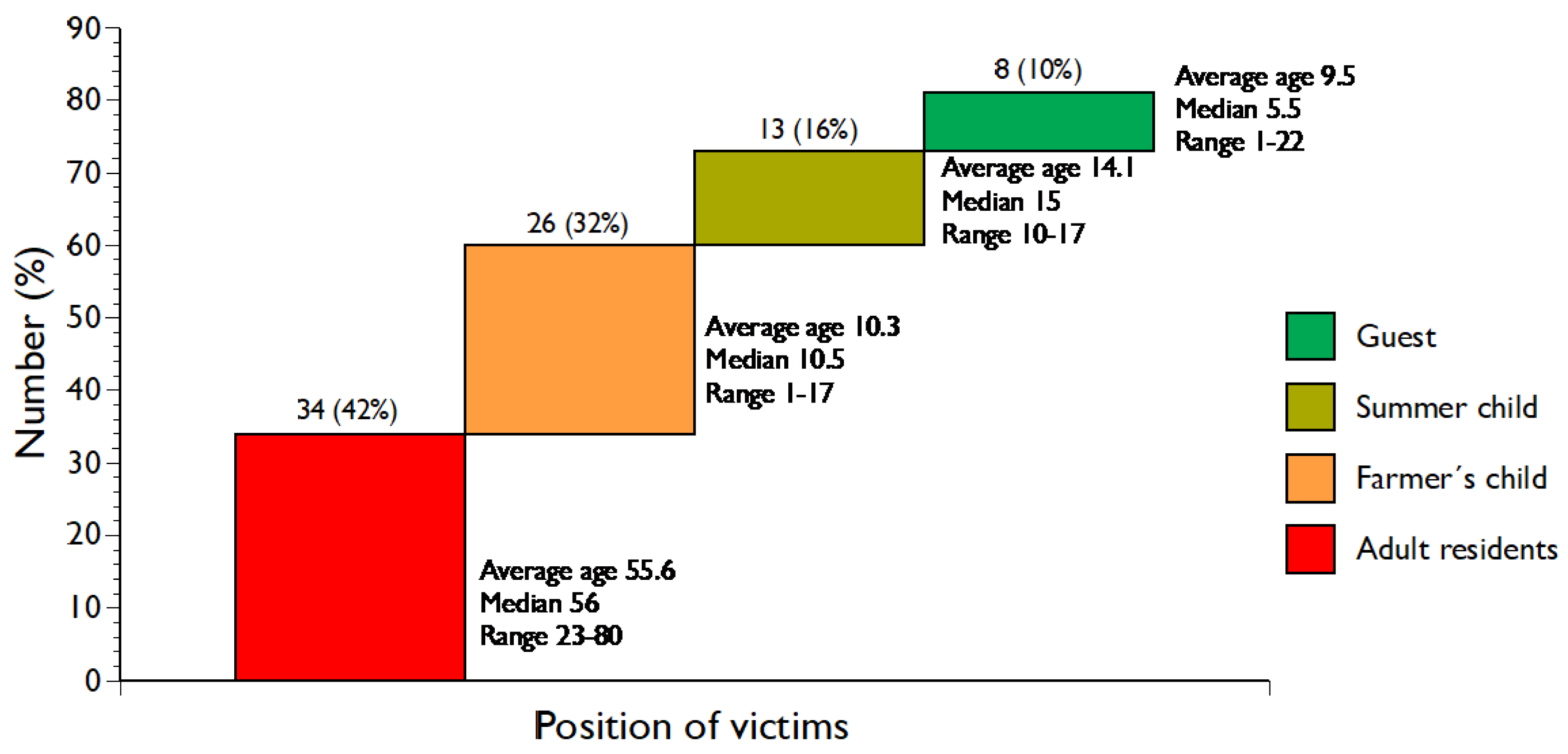

3.1.2. Positions of Victims

Three-fourths of victims in tractor-related fatalities were farmers and their children (

Table 1 and

Figure 1). Nine (11.1%) fatalities involved females, i.e., one was a farmer, one was an adult child to farmers, five were young daughters of the farmers, and two were guests. All the summer children who died were boys.

Eight (9.9%) of the fatalities involved guests on the farm, six children and two adults (

Table 1 and

Figure 1); one of the adults (male) had earlier been a summer child on the farm who came to help during the harvest season. The guests were involved in rollover (two children; two adults), machinery (three children) and drive-over accidents (one child).

3.1.3. Age at Death

The average age at death was 29.0 years (median 16, range 1-80); for males it was 30.8 years (median 17, range 1–80) and for females 14.3 years (median 6, range 1–58). The difference in age of males compared to females was not statistically significant (p=0.052).

Children (aged <18 years) were involved in 45 (55.6%) of the tractor-related accidents with a fatal outcome (

Table 1); 38 (84.4%) were boys and seven (15.6%) girls. The mean age for boys was 11.6 years (median 13, range 1-17) compared to 6.1 years for girls (median 5, range 1-12); the age difference between boys and girls is statistically significant (p=0.0060). Children to farmers were significantly younger than the summer children (10.3 years compared to 14.1 years (p=0.0131).

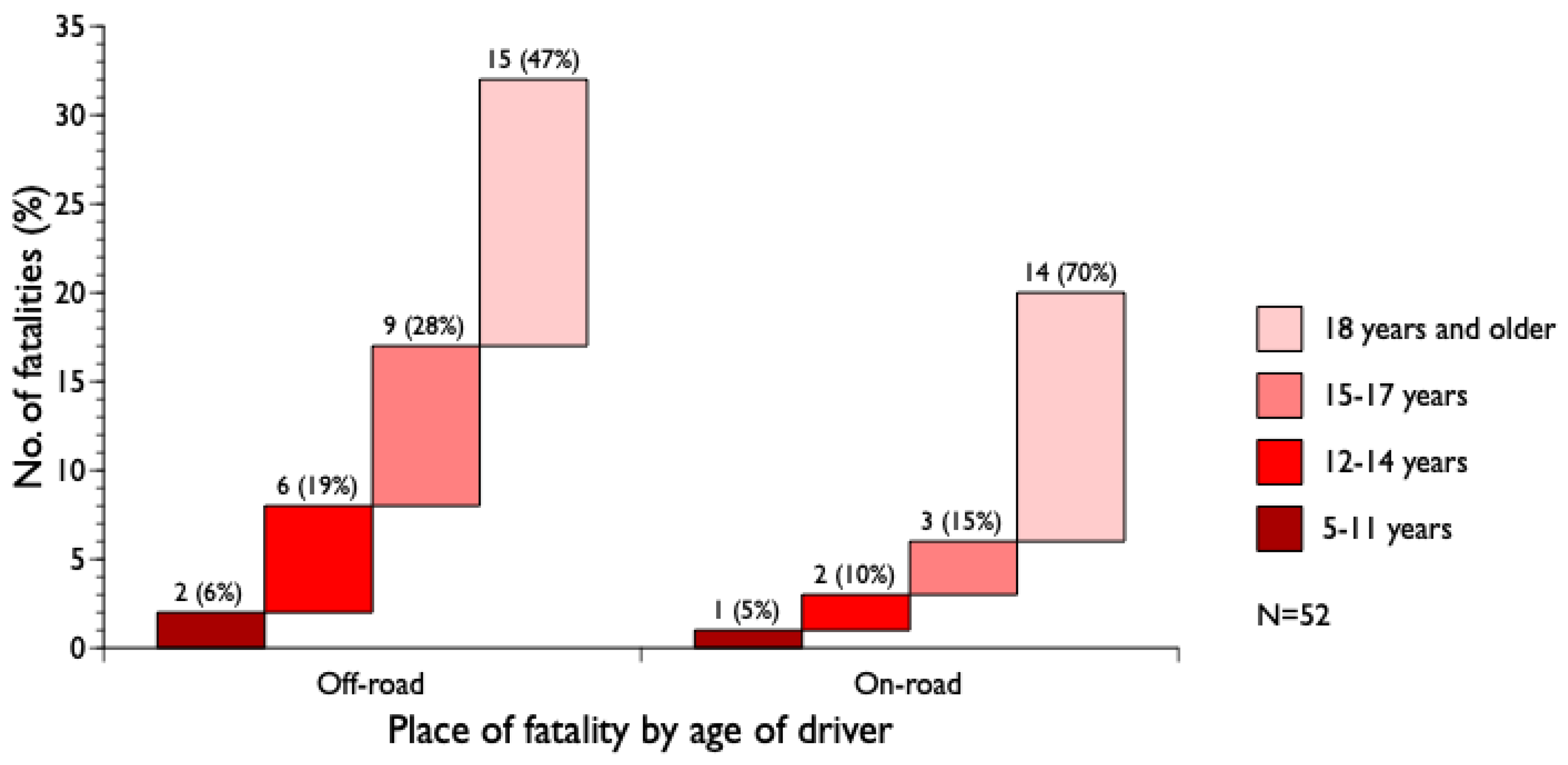

Out of the 81 fatalities, 52 (64.2%) involved the driver of the tractor (

Figure 2); their average age was 36.1 years (median 28, range 10-80). The average age of the drivers off-road (n=32) was 34.1 years (median 17, range 10-79) compared to 39.4 years (median 37, range 10-80) for those driving the tractor on-road (n=20). There was no statistically significant difference (p=0.4449) in the age of those who drove off-road compared to those who drove on-road.

Out of 45 fatalities involving children, 23 (51.1%) drove the tractor themselves. Their average age was 14.1 years (median 12, range 10-17). The majority of these fatalities (n=20; 87%) occurred in the period 1958-1988; three occurred earlier, and no child has died when driving a tractor since 1988.

Twenty-nine (35.8%) fatalities occurred to passengers on the tractor or bystanders. Their average age was 16.2 years (median 10, range 1-78). All except one died off-road; 22 (75.9%) were children (<18 years). The mean age of the children was 10.8 years (median 12, range 1-17).

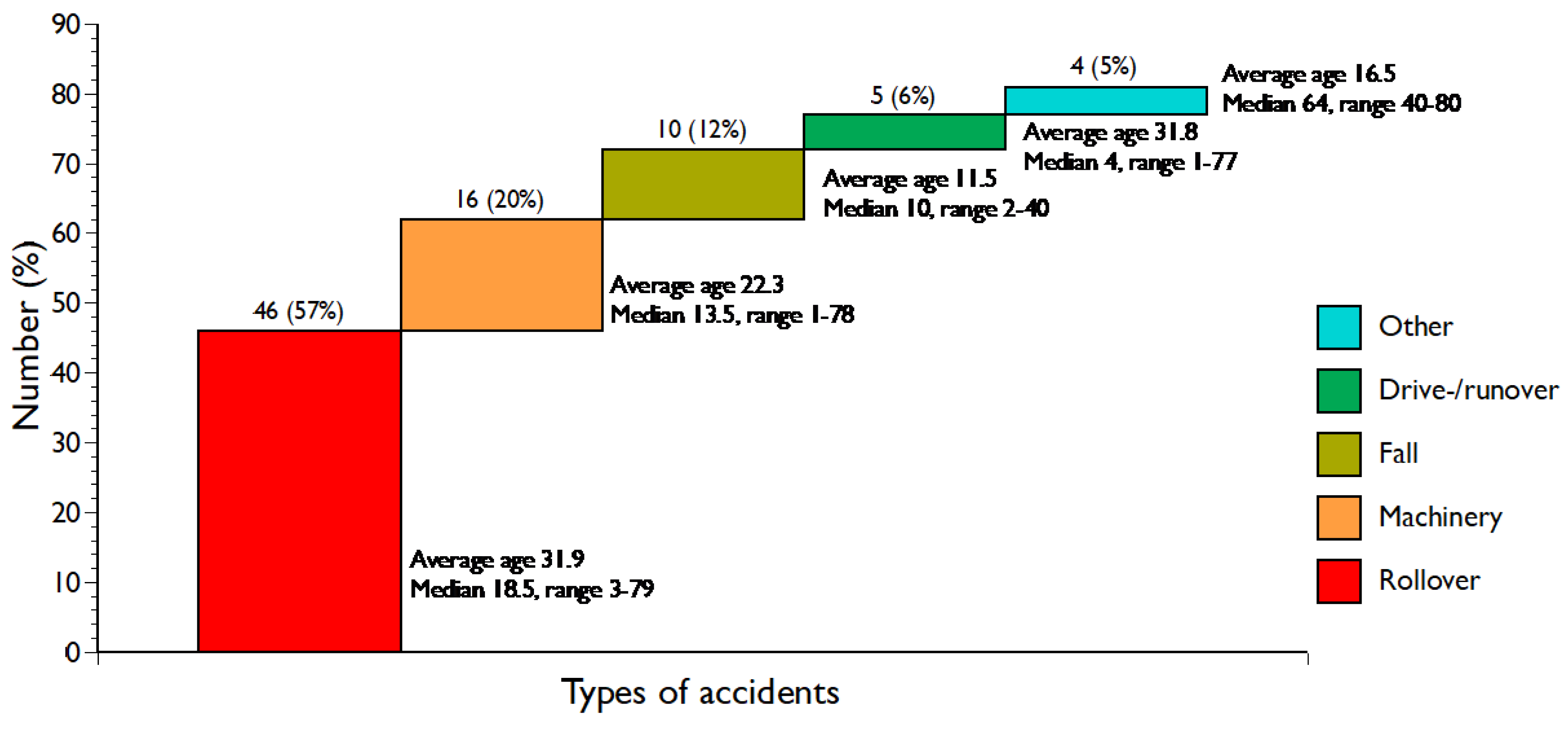

3.1.4. Types of Accidents

The rollover was the most frequent type of accident, i.e., 46 (56.8%) out of 81 fatalities (

Table 1 and

Figure 3); all the victims were males except one. One-half of rollover fatalities involved children, and 29 (63.0%) occurred off-road

.

The average age of 43 drivers in rollover accidents was 33.6 years (median 22, range 10-79); three who did not drive the tractor were aged 3, 7 and 15. In 20 (43.4%) out of 46 rollover fatalities, the driver was less than 18 years of age; their average age was 14.6 (median 15, range 10-17).

Being caught in equipment or machinery fatalities was the second most frequent type of accident, i.e., 16 (19.7%) out of 81 (

Table 1 and

Figure 3). Fourteen (87.5%) involved males and 10 (62.5%) were children. All except one (93.8%) occurred off-road. Seven (43.8%) of the fatalities were caused by the PTO shaft of a tractor and nine from other types of machinery, e.g., carriage for hay, mower and fertilizers.

Falls from a tractor caused 10 (12.3%) fatalities (

Table 1 and

Figure 3), and all occurred off-road. All except one (90%) were children, five boys and four girls.

Other types of fatalities were nine and included five drive-/runovers (6.2%), two collisions (2.5%), one crushing (1.2%) and one (1.2%) caused by a snow avalanche; three (33.3%) were children. Drive-over involves a tractor with a driver while in a runover; the tractor runs over the victim without a driver.

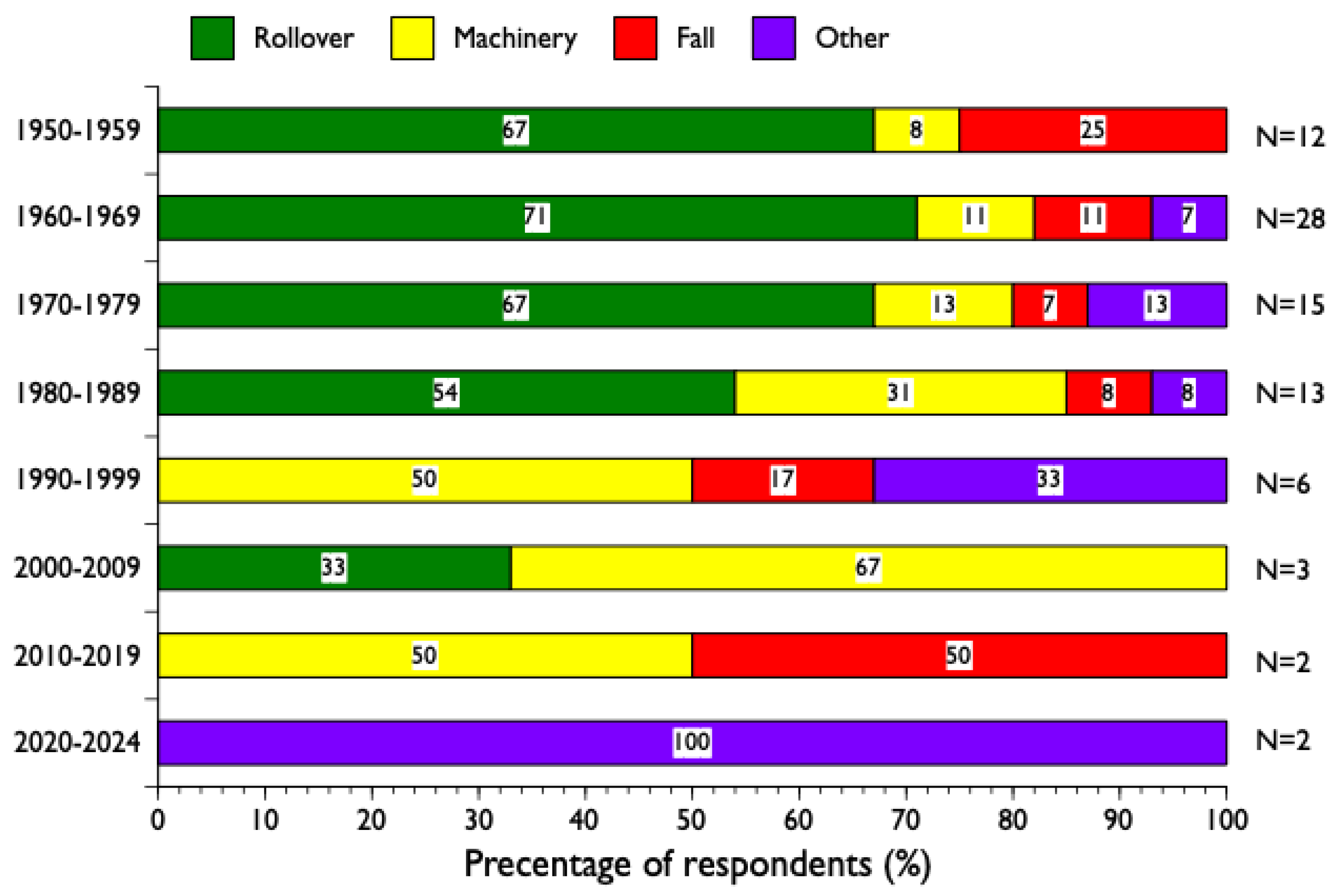

The types of accidents have changed since 1950 (

Figure 4). Rollover accidents were most common from 1950 to 1989 but mostly disappeared, with the last one in 2009. Machinery accidents continued to occur every decade, the last one in 2011. Similarly, falls from a tractor occurred occasionally during the whole period, the last one in 2015.

3.1.5. Timing of Accidents

Most tractor-related fatalities occurred during the daytime and from April to September, i.e., during the work-intensive lamming and haying season (

Table 1). There is no significant difference in the days of the week, including the weekend.

Figure 1 depicts the distribution of the 81 fatal accidents involving tractors from 1 January 1950 to 31 July 2024 by the victim’s age.

3.1.6. Environment and Other Context

The news reports often, but not always, informed about challenging circumstances at the time of the accidents. The tractors traversed diverse terrain, including dirt roads, uncultivated fields, tussocks, marshlands, icy surfaces, and hills. The drivers apparently lost control, with at times attached equipment, when crossing bridges of varied quality, making curves, and operating alongside ditches and rivers. The weather was sometimes bad, and a snow avalanche hit one driver. Mechanical failure was cited as the probable cause in three accidents. Fatigue was reported as a factor for one young driver, while an adult operator was described as both intoxicated and exhausted.

3.2. Driving Tractors at a Young Age: Ambiguous Adventure

The narratives of the study participants who had stayed at farms during the summertime in childhood primarily focus on when and under what circumstances summer children began driving tractors, the tasks they were entrusted with, and the awareness of safety issues among farmers. Above all, these accounts reflect the fascination that tractors held for many of these seasonal residents.

Tractors and farm machinery captivated summer children, particularly boys. A male participant who spent summers in the countryside during the 1980s expressed his adoration for these machines and the joy of being “immersed in mud and machinery all day long.” He found the old, open tractors refreshing, noting no risk of falling asleep, unlike the newer models with enclosed cabs. Like most young drivers, he enjoyed the work. Some young drivers sang or listened to music when driving, simultaneously maintaining focus on the task at hand. Although fewer girls than boys drove tractors, some remembered the experience fondly.

A few participants did not express much enthusiasm for tractors. A male participant who spent summers with his grandfather in the mid-20th century found driving tractors acceptable for travelling between points but did not engage in aimless driving. Another, who stayed at farms in the 1960s, initially found tractor driving exciting but grew weary due to long working days. Some participants admitted that driving for extended periods was tiresome, and those of shorter stature recalled having to stand up from the seat to reach the clutch and brakes.

The age at which children started driving tractors varied considerably. One male participant began as young as 7 in 1982, although he considers his “real” start around when aged 11 or 12. A female participant began operating machines around the age of nine or 10, considering it part of the work ethic on the farm. Another did not recall her exact age but mentioned that her brother began at age 6. Many children started at nine to 12, often with simple tasks before progressing to more complex operations. The participants frequently noted that children raised on the farm began driving tractors earlier than they did and generally worked more.

The types of tractors and tasks assigned to children varied. Some drove older models without safety features. The newer tractors were described as heavy with enclosed cabs and roll bars; thus, children were often assigned to use the old ones, those without ROPS. Tasks included various haymaking steps, transporting goods, and even driving on public roads in some cases. The level of instruction provided to the children differed, with some receiving detailed adult guidance and others learning primarily through observation. A male participant who stayed at a farm in the 1980s mentioned that his uncle taught him extensively about tractors and cars, although safety was not explicitly discussed. A male teenager who drove a modern tractor in the 21st century received detailed instructions from a female farmer, whom he regarded as an expert driver. Sometimes, more experienced boys from the farm served as instructors. During the early years of tractor use in the countryside, farmers, some of whom had little experience driving tractors themselves, called upon experienced summer boys to assist with haying.

Safety was a concern, though approaches varied widely. Narratives highlighted a lack of maintenance, which resulted in a malfunctioning braking system and steering mechanism. Some farmers were, however, strict on maintenance and safety measures, while others seemed less concerned or lacked knowledge. All participants recalled hearing about tractor accidents on the radio, many of which were fatal. Several participants mentioned specific safety hazards, such as unprotected PTO shafts, which could catch clothing and cause severe injuries. As time progressed, awareness of safety issues grew. A male participant staying at a farm in the late 1980s and early 1990s emphasized the strict safety measures to prevent accidents.

The narratives indicate varying attitudes among parents and guardians regarding their children operating tractors and being around dangerous equipment. Some parents were fearful due to the known risks, while others seemed less concerned. An elderly male participant, who had stayed at a farm in childhood before the tractor era, allowed his son to stay at a farm and drive a tractor despite his worries. His son’s classmate died in a tractor accident that same summer. There was a strong work ethic that sometimes prioritized productivity over safety, particularly during the haying season when it was crucial to take advantage of sunny days. One male participant noted that tractor accidents were often viewed as “almost a natural sacrifice” within this work culture. Another recalled a sunny day when a tractor rolled over, and the farmer died; in the afternoon, household members righted the tractor and continued working.

The farmers and summer children seemed well-informed about laws regarding tractor driving, particularly that children were not allowed to drive on main roads. However, they were unevenly concerned about compliance. All were aware of the frequently discussed tractor accidents; most recalled particular incidents. Nonetheless, only one male participant mentioned an incident involving police intervention. He had been stopped by police while driving a tractor on the main road, which he knew was unlawful. The situation was handled casually; his grandfather, unfamiliar with tractors and lacking a driving license, drove the tractor back to the farm. Afterwards, the police had coffee with his grandfather at the farm.

3.3. Parliamentary Debates

The introduction of tractors to the country necessitated new legislation governing their use, including regulations for their operation. Frequent fatal tractor accidents were a primary concern, and parliamentarians debated how to prevent such incidents. The main issues discussed included establishing a minimum age for driving tractors off-road for agricultural work and implementing other protective measures.

3.3.1. Traffic Act no. 26/1958

On 18 February 1957, a new traffic law bill was submitted to the Alþing. It proposed lowering the minimum age for driving vehicles on main roads from 18 to 17 years and driving tractors off-road from 18 to 15 years [

44]. Furthermore, the bill proposed that a particular licence should be issued to allow 16-year-old adolescents and adults without driving licences for cars to drive a tractor on main roads. Nonetheless, the bill’s sponsor argued upfront against the age limits for driving tractors off-road as proposed to have no minimum age for such driving because the age limit would not be respected [

45].

MPs debated the bill; they disagreed about the minimum age for off-road tractor driving [

45]. Some noted that the Farmers Association favoured removing the age limit, proposing instead that tractor owners or operators should ensure only capable individuals operated the tractor. During the debates in 1957 and 1958, MPs who advocated for a law suggested a minimum age of 14 years for off-road tractor driving in farming and haymaking contexts. This group acknowledged children’s and adolescents’ desire to drive tractors but cited expert opinions that such activities could negatively impact neurological development without proper care and moderation. They argued that while a 14-year age limit would not entirely prevent accidents, older teenagers would likely be more capable of operating tractors than, e.g., 10- or 12-year-olds. One MP emphasized that farmers should not rely on child labour for tractor operation and stressed the role of Aþingi in implementing appropriate legislation to enhance the security in agriculture.

In the spring of 1958, the Alþingi approved the Traffic Act no. 26/1958 [

46]. This legislation stipulated that tractor drivers on main roads must possess either a car driving license or a special tractor license issued to individuals 16 years or older. However, it did not specify a minimum age for off-road tractor driving. MPs acknowledged that preventing tractor accidents would require increased emphasis on education and safety measures, including ROPS.

3.3.2. Debates on a Minimum Age Proposal in 1966

Following the Traffic Act no. 26/1958, a parliamentary proposal was approved on March 27, 1961, to investigate tractor accidents and recommend security improvements. Five years later, in the fall of 1966, a report revealed 23 tractor accidents since 1958 [

47]. In response, an MP submitted a bill to amend the Traffic Act of 1958, proposing a 14-year minimum age for off-road tractor drivers and mandating the use of safety equipment [

45].

MPs debated the bill [

45]. The Minister of Justice expressed worries regarding the fatal tractor accidents but questioned whether age restrictions would have prevented such incidents. He highlighted a recent regulation requiring importers to sell tractors with safety frames or cabs, effective from 1 January 1966. However, he noted that this regulation did not require farmers to retrofit older tractors with safety equipment. The Minister of Agriculture deemed the proposed 14-year age limit invalid, noting that older age groups experienced more accidents than adolescents.

Following parliamentary discussions, the Alþingi rejected reintroducing a minimum age for off-road tractor driving. The Farmers Association’s Annual Meeting had previously opposed such a requirement, arguing that fatal tractor accidents were equally distributed across age groups. Further, its members pointed out that age restrictions would limit farmers’ access to labour and instead proposed stricter monitoring of tractor safety equipment.

3.3.3. Debates on Safe Driving in 1970

In the fall of 1970, the MPs debated a proposal addressing tractor safety [

45]. It suggested implementing regular inspections and considering whether farmers should be required to install safety equipment on older tractors [

45]. The ensuing debate saw MPs generally supporting enhanced tractor security and driver education. However, some MPs cautioned against “expert” proposals they deemed extreme, such as requiring lights on tractors only used during daylight hours. A few MPs expressed concerns about the high costs associated with tractor safety measures, while others argued that such expenses were negligible compared to the value of human life.

Although the proposal did not include minimum off-road tractor driving age provisions, some MPs argued against such restrictions [

45]. One MP acknowledged the risks of allowing teenagers and children to drive tractors but maintained that age limits would not prevent accidents. Another MP, a farmer, asserted that in his experience, the most skilled tractor drivers were often 12-14 years old.

Following these deliberations, the Alþingi passed a bill instructing the government to promote better supervision of tractor safety equipment and evaluate the need for enhanced driver skills.

3.3.4. Traffic Act no. 50/1987

A traffic law bill submitted to the Alþingi in 1986 initially proposed setting the minimum age at 14 years for off-road tractor driving in agricultural work [

45]. However, the MP sponsoring the bill on behalf of the General Committee of the Alþingi announced that the Committee recommended lowering this age limit to 13 years. The Committee viewed this reduction as “a more realistic approach for teenagers to use these devices legally” and believed it would ensure they received the necessary driving instruction. There was no debate, but one MP opposed lowering the age, noting that the “worst drivers” were typically 17–19 years old. The bill was approved, and the Traffic Act no. 50/1987 came into force on 1 July 1988 [

48], ending a three-decade period without age restrictions for off-road tractor driving in agricultural work.

4. Discussion

Here, we examine fatal tractor accidents in Icelandic agriculture from 1918 to 2024, children’s narratives about tractors and related legislation. Most fatalities involved adult farm residents, farmers’ children and summer children who stayed at the farm during the summertime. Most fatal tractor-related accidents occurred off-road; more than half involved children, primarily boys, and three-fourths happened from 1958 to 1988 when legislation with no minimum age for off-road tractor driving existed. There was no age difference in fatalities between on-road and off-road drivers. Former summer children’s narratives provide insights into tractor use during farm stays and how tractors were received with admiration but also fear due to frequent reports of fatal tractor-related accidents. Meanwhile, MPs debated legalising a minimum driving age for off-road driving to prevent accidents. Arguments against minimum age included the necessity of child labour, children’s superior driving skills, and claims that child mortality rates were not higher than for adults. Some suggested alternative measures like ROPS and improved education. Contrary to MPs’ claims, results indicate that children’s incidence of fatalities was up to four times higher than for adults.

4.1. Children and Fatal Tractor-Related Accidents

Following the independence of Iceland in 1944, the import of tractors and mechanisation of agriculture increased steadily. Farmers admired the tractors for their capacity; however, most had limited experience in their usage. At the same time, the rapid rural-to-urban migration resulted in a lack of rural workforce. The lack of workforce was partly alleviated by summer children, i.e., urban children who stayed at farms during the summertime, and the rural children also contributed to the rural economy with their labour [

38]; until the late 20th century, Icelandic children were active within other industrial sectors as well, not least fishing [

49].

The findings highlight the high number of tractor-related fatalities in agriculture among children compared to adults; over half of all involved children (

Table 1) and most victims were males. The incidence of fatalities was more than four times higher among those aged 12–17 and 1.5 times higher for younger children aged less than 12 compared to adults when there was no minimum age for driving tractors off-road (

Table 2). Further, since 1988 or after new legislation took effect on a minimum age of 13 years for off-road driving, the incidence of tractor-related fatalities in agriculture has substantially declined, with no fatalities of children driving a tractor.

Farming is recognised as a dangerous occupation [

50,

51,

52], not the least for children [

20,

53], and the farm is characteristically the residence, site of play and working place of family members [

5,

52,

54]. In Iceland, three-fourths of all victims in tractor-related fatalities in the period 1918-2024 were the farmers themselves, almost entirely males and their children (

Table 1 and

Figure 1). Added to this, 16% of the fatalities involved summer children staying at the farm, a custom deeply rooted in Icelandic culture [

38].

Rollover is recognised as the most common cause of tractor-related fatalities followed by diverse machinery [

17,

26,

50]. Likewise, the rollover of tractors and associated machinery in Iceland caused three-fourths of all tractor-related fatalities (

Table 1 and

Figure 3). One-half of rollover fatalities involved children, and in more than two-fifths of the cases, the driver was a child (<18 years). Research in Iceland on the practice of sending children to stay at a farm during the summer, based on a national random sample of adults, showed that almost half of all with the experience as children had driven a tractor during their stay on the farm; the mean age at the first time they drove a tractor was 11.4 years, and one-fourth drove a tractor before they reached 10 years [

37]. We do not have corresponding information about the farmers’ children, though we know from the narratives that they began driving a tractor younger than summer children. This is further supported by their statistically significantly younger age at the time of the accident than for the summer children (

Figure 1), and almost half of them were driving the tractor.

In our data, children were caught in machinery, often at a young age, or in 10 (62.5%) out of 16 such fatalities (

Table 1 and

Figure 3). In the US, from 1979 to 1985, more than half of all farm-related fatalities among children in two states involved tractors and other moving farming machinery [

6]. Similarly, as seen, e.g., in Turkey [

17] and North America [

3,

6,

22], the fatalities vary by season. In Iceland, most fatalities occurred from April to September, i.e., during the labour-intensive lamming and harvest season (

Table 1).

Both boys and girls are at risk of injury and fatality as bystanders and passengers within the rural communities [

50]. In our study, particularly young children, independent of gender, were at risk of death as bystanders and passengers. Three young children died in drive-over accidents: two girls and one boy. All ten falls from a tractor occurred off-road (

Figure 2), and all victims but one were children. Guests are also exposed to the risk of injury while visiting the farm, irrespective of whether they come for play or work [

54]. In our study, there were eight tractor-related fatalities involving guests (

Table 1 and

Figure 1). One of the adult guests was a former summer child.

Although children had a higher incidence of death than adults, the high number of fatalities of farmers is noteworthy. The former summer children’s narratives reveal that the farmers, particularly elderly ones, were not always experienced drivers, and the maintenance of the tractors could be deficient, and some of the tractors were old. The participants’ narratives highlight how the tractors were a recent phenomenon and often the first vehicle at the farm. The farmers had no experience in driving when they got their first tractor, and the roads were inadequate or non-existent; e.g., in the 1950s, a farmer died when his new tractor overturned on the way to the farm [

37].

Allocation of tasks to children that they are not ready to perform because of immature cognitive and judgment skills or physical strength is a recognised risk factor [

20,

50]. Driving a tractor was an exciting and ambiguous experience for the study participants. It could be challenging to drive a tractor, partly because the youngest drivers were too short and did not always reach the clutch and brakes. In addition, driving long distances was tiresome. All the former summer children knew about the tractor accidents when staying at a farm, and a few experienced deaths or injuries among someone they knew. As reported elsewhere, farmers’ safety awareness varied, which also applied to the children’s safety instructions [

26,

55,

56].

4.2. Preventive Policy Measures

Most Icelandic MPs agreed to have no legalised minimum age for off-road driving of tractors from 1958 to 1988. Their arguments mostly align with five policy narratives used by policymakers in the Province of Alberta, Canada, to justify that child work within agriculture was unregulated [

57]. The first one, that children’s agricultural chores are not real work, was not heard in the Icelandic Alþingi, nor did Icelandic MPs emphasise the particularities of farming compared to other industries [

45]. The MPs, who resisted legalising minimum age for driving tractors off-road, underlined, like policymakers in Alberta, that the farmers required children’s work. They argued that education was more effective than regulation, that the families were better equipped to protect the children than any regulatory body, and that children were even better drivers than adults; they even rejected evidence that children were more likely to be victims of tractor-related accidents than adults. When confronted on the issue, the Icelandic MPs claimed that laws on minimum age would not be followed anyway. These arguments have not stood the test of time, and notably, in 1987, when the minimum age was discussed in Alþingi, no MP repeated former arguments or forwarded new ones against such law [

45].

The debates in Alþingi illustrate the influence of the Farmers Association on legislation of importance for their interests [

45]. At the time, most MPs had rural backgrounds and supported their constituencies. Whatever opinion MPs had on a minimum age to drive a tractor off-road, they agreed on the importance of education and other preventive measures. However, a few MPs warned against the “experts” for exaggerating safety demands and controls. In 1966, when ROPS was mandated on new tractors, retroactive installation on older tractors was excluded because it would be costly for farmers, as found elsewhere [

25]. However, times are changing; no MPs opposed setting a minimum age of 13 years for off-road tractors at Alþingi in 1988 when the number of fatal tractor-related accidents was already declining (

Figure 5). At that time, the farmers’ political position was weaker, and other legislation had been enacted that entailed policy to limit the over-production of lamb meat and milk products [

58].

Throughout the years, there have been calls for more regulatory approaches to prevent deaths and injuries of children within agriculture, including operations of tractors and other machinery [

2,

53,

59]. Although rollover accidents have decreased significantly with the use of ROPS, the last one in Iceland occurred in 2009; such accidents are still frequent elsewhere [

26,

27,

28]. Further, there is a need for seat belts in ROPS-equipped tractors, and they should be fastened, and passengers should not be allowed [

14,

50].

The circumstances and context of fatal accidents, as described in

section 3.1.6, might be seen as the ultimate cause of a fatal tractor-related accident. Fragnoli et al. [

60] advocate for a human-centred approach to safety measures, emphasizing the importance of addressing unsafe working conditions and the drivers’ capacity. They highlight the drivers’ need to anticipate potential hazards, maintain focus, and consider factors such as fatigue, stress, and environmental conditions to enhance overall safety. Based on the narratives of former summer children, a similar approach is warranted in Iceland; children and farmers alike worked long hours into the bright summer nights, and many highlighted how tiresome it was to drive a tractor all day long.

4.3. Strengths and limitations

The study has several strengths. First, it is based on quantitative and qualitative data combined with secondary data on all tractor-related fatalities in Iceland from 1918 to 2024. Second, interviews with adults who were sent to stay at farms during the summer in childhood highlight the children’s fascination for tractors and how they drove tractors at a young age, too many paying with their lives. Third, the debates of MPs in Alþingi vividly illuminate the political power of farmers, who used child labour in increasingly mechanised agriculture and times of rapid rural-to-urban migration.

The study has limitations. First, information is lacking on who was driving the tractor in most cases when bystanders and passengers were the victims. Second, there is no information on other farm injuries. Third, we might not have found all tractor-related fatalities with the search terms used, or the event was not reported in newspapers. Fourth, someone may have been injured in a tractor accident and died later without it appearing in the newspapers and annual public reports; however, this is unlikely considering the surveillance of tractor-related accidents by various public and private actors over the decades.

Finally, research on children’s experiences as tractor operators is lacking. Likewise, research is missing on contemporary arguments for not adopting laws on a minimum age for driving tractors.

5. Conclusions

The study reveals that children were at the most risk of becoming victims of fatal tractor-related accidents in Iceland since the arrival of the first tractor to the country in 1918; they lost their lives as drivers, bystanders and passengers, most often off-road. It highlights the dangers of farming for rural children, as well as for other children staying at the farm and child visitors.

While preventive measures, including education, ROPS and use of seat belts, are crucial, the resistance to setting a minimum age limit is remarkable; some of the MPs’ arguments against legalising a minimum age for driving tractors off-road do not stand the test of time. Our findings suggest that the abolition of the minimum age for off-road driving from 1958 to 1988 might have contributed to increased fatalities among children and adolescents, and probably also adults.

When possible, the legislator should alleviate obvious safety risks for its citizens, not least for children. We highlight Lee’s [

61] observation that referring to child farm injuries as “accidents” takes away adult responsibility; furthermore, it may impede a proper investigation of the incident and preventive efforts to secure children’s safety, and “[i]n some cases, it denies justice to the child victim.” A human-centred approach to safety measures helps address unsafe working conditions and environments, driver capacity, and adherence to safety procedures and legal frameworks to prevent future accidents.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Jónína Einarsdóttir and Geir Gunnlaugsson; Data curation, Jónína Einarsdóttir and Geir Gunnlaugsson; Formal analysis, Jónína Einarsdóttir and Geir Gunnlaugsson; Investigation, Jónína Einarsdóttir and Geir Gunnlaugsson; Methodology, Jónína Einarsdóttir and Geir Gunnlaugsson; Resources, Jónína Einarsdóttir and Geir Gunnlaugsson; Validation, Jónína Einarsdóttir and Geir Gunnlaugsson; Writing – original draft, Jónína Einarsdóttir; Writing – review & editing, Jónína Einarsdóttir and Geir Gunnlaugsson.All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Science Ethics Committee of the University of Iceland (15-005, 29 May 2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. The use of secondary data on fatal tractor accidents and parliamentary debates, which are publicly accessible, do not require additional ethical approval. Given the sensitive nature of the data, care was taken to omit the names of individual Members of Parliament (MPs), accident victims, and specific accident locations.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article. The original contributions presented in the study are included, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Ester Ösp Valdimarsdóttir, Tinna Grétarsdóttir, og Þórunn Hrefna Sigurjónsdóttir are gratefully acknowledged for their contribution to the qualitative part of the study; Auður Inga Ísleifsdóttir is also acknowledged for her contribution to the collection of secondary data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Goldcamp, M.; Hendricks, K.J.; Myers, J.R. Farm Fatalities to Youth 1995–2000: A Comparison by Age Groups. J. Safety Res. 2004, 35, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hard, D.L.; Myers, J.R. Fatal Work-Related Injuries in the Agriculture Production Sector among Youth in the United States, 1992–2002. J. Agromedicine 2006, 11, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, M.M.; Field, W.E.; Ni, J.-Q.; Cheng, Y.-H. Farm-Related Injuries and Fatalities Involving Children, Youth, and Young Workers during Manure Storage, Handling, and Transport. J. Agromedicine 2021, 26, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivara, F.P. Fatal and Nonfatal Farm Injuries to Children and Adolescents in the United States. Pediatrics 1985, 76, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivara, F.P. Fatal and Non-Fatal Farm Injuries to Children and Adolescents in the United States, 1990-3. Inj. Prev. 1997, 3, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, L.R.; Weiss, H.B.; Peterson, P.L.; Spengler, R.F.; Sattin, R.W.; Anderson, H.A. Fatal Farm Injuries among Young Children. Pediatrics 1989, 83, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karunanayake, C.P.; Koehncke, N.; Enebeli, S.; Ulmer, K.; Rennie, D.C. Trends in Work-Related Fatal Farm Injuries, Saskatchewan, Canada: 2005–2019. J. Agromedicine 2023, 28, 444–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, G.W.; Belton, K.L.; Pickett, W.; Schopflocher, D.P.; Voaklander, D.C. Fatal and Non-fatal Machine-related Injuries Suffered by Children in Alberta, Canada, 1990–1997. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2004, 45, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voaklander, D.C.; Rudolphi, J.M.; Berg, R.; Drul, C.; Belton, K.L.; Pickett, W. Fatal Farm Injuries to Canadian Children. Prev. Med. 2020, 139, 106233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.; Kennedy, A.; Cotton, J.; Brumby, S. Child Farm-Related Injury in Australia: A Review of the Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 6063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byard, R.W.; Gilbert, J.; Lipsett, J.; James, R. Farm and Tractor-Related Fatalities in Children in South Australia. J. Paediatr. Child Health 1998, 34, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lilley, R.; McNoe, B.; Davie, G.; De Graaf, B.; Driscoll, T. Work-Related Fatalities Involving Children in New Zealand, 1999–2014. Children 2020, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinzke, S.; Nilsson, K.; Lundqvist, P. Tractor Accidents in Swedish Traffic. Work 2012, 41, 5317–5323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rondelli, V.; Casazza, C.; Martelli, R. Tractor Rollover Fatalities, Analyzing Accident Scenario. J. Safety Res. 2018, 67, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antunes, S.M.; Cordeiro, C.; Teixeira, H.M. Analysis of Fatal Accidents with Tractors in the Centre of Portugal: Ten Years Analysis. Forensic Sci. Int. 2018, 287, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarén, C.; Ibarrola, A.; Mangado, T.; Adin, A.; Arnal, P.; López-Maestresalas, A.; Ríos, A.; Arazuri, S. Fatal Tractor Accidents in the Agricultural Sector in Spain during the Past Decade. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcin, E.S.; Darcin, M. Fatal Tractor Injuries between 2005 and 2015 in Bilecik, Turkey. Biomed. Res. 2017, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Karbeyaz, K.; Şimşek, Ü.; Yilmaz, A. Deaths Related to Tractor Accidents in Eskişehir, Turkey: A 25-Year Analysis. J. Forensic Sci. 2019, 64, 1731–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.M.S.; Li, S.; Issa, S.F. Global Patterns of Agricultural Machine and Equipment Injuries- A Systematic Literature Review. J. Agromedicine 2024, 29, 214–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorsandi, F.; De Moura Araujo, G.; Fathallah, F. A Systematic Review of Youth and All-Terrain Vehicles Safety in Agriculture. J. Agromedicine 2023, 28, 254–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arana, I.; Mangado, J.; Arnal, P.; Arazuri, S.; Alfaro, J.R.; Jarén, C. Evaluation of Risk Factors in Fatal Accidents in Agriculture. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2010, 8, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R.A.; Smith, J.D.; Sikes, R.K.; Rogers, D.L.; Mickey, J.L. Fatalities Associated with Farm Tractor Injuries: An Epidemiologic Study. Public Health Rep. 1985, 100, 329. [Google Scholar]

- Rees, W.D. Tractor Accidents. Br. Med. J. 1966, 2, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, M.; Faust, K.; Peek-Asa, C.; Ramirez, M. Characteristics of Farm Equipment-Related Crashes Associated With Injury in Children and Adolescents on Farm Equipment. J. Rural Health 2015, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J.R.; Snyder, K.A.; Hard, D.L.; Casini, V.J.; Cianfrocco, R.; Fields, J.; Morton, L. Statistics and Epidemiology of Tractor Fatalities. A Historical Perspective. J. Agric. Saf. Health 1998, 4, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlson, T.; Noren, J. Farm Tractor Fatalities: The Failure of Voluntary Safety Standards. Am. J. Public Health 1979, 69, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, J.R.; Hendricks, K.J. Agricultural Tractor Overturn Deaths: Assessment of Trends and Risk Factors. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2010, 53, 662–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoskopf, C.H.; Venn, J. Farm Accidents and Injuries: A Review and Ideas for Prevention. J. Environ. Health 1985, 47, 250–252. [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint, M.; Faust, K.; Peek-Asa, C.; Ramirez, M. Characteristics of Farm Equipment-Related Crashes Associated With Injury in Children and Adolescents on Farm Equipment. J. Rural Health 2015, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, D.P. Scale versus Scope in the Diffusion of New Technology. Harv. Bus. Sch. Work. Pap. Ser. 16-108 2016.

- Manuelli, R.E.; Seshadri, A. Frictionless Technology Diffusion: The Case of Tractors. Am. Econ. Rev. 2014, 104, 1368–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ólafsson, Á. Upphaf Vélvæðingar í Íslenskum Landbúnaði. Morgunblaðið 1998, 179, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Jónsson, P.G.; Jónasson, Þ. Vélvæðing Til Sjós Og Lands: Tækniminjar í Þjóðminjasafni. In Hlutavelta tímans: menningararfur á Þjóðminjasafni; Björnsson, Á., Róbertsdóttir, H., Eds.; Þjóðminjasafn Íslands: Reykjavík, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ásgeirsson, Ó. Iðnbylting hugarfarsins: átök um atvinnuþróun á Íslandi 1900–1940; Bókaútgáfa Menningarsjóðs, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsson, G.Á. Ísland Og Marshalláætlunin 1948 – 1953: Atvinnustefna Og Stjórnmálahagsmunir. Saga 1996, 34, 85–130. [Google Scholar]

- Árnastofnun Gríður, Jón Dýri og Íhalds-Majórinn. Um nafngiftir dráttarvéla. Available online: https://www.arnastofnun.is/is/utgafa-og-gagnasofn/pistlar/gridur-jon-dyri-og-ihalds-majorinn-um-nafngiftir-drattarvela (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- Einarsdóttir, J.; Gunnlaugsson, G. Af Dráttarvélum. In Send í sveit: Þetta var í þjóðarsálinni; Einarsdóttir, J., Gunnlaugsson, G., Eds.; Hið íslenska bókmenntafélag: Reykjavik, 2019; pp. 251–283. [Google Scholar]

- Einarsdóttir, J.; Gunnlaugsson, G. (Eds.) Send í Sveit: Þetta Var í Þjóðarsálinni [Sent out into the Country: It Was Part of Being an Icelander]; Hið íslenska bókmenntafélag: Reykjavík, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Einarsdóttir, J.; Valdimarsdóttir, E.Ö.; Sigurjónsdóttir, Þ.H.; Gunnlaugsson, G. Send í sveit. Súrt, saltað og heimabakað; Hið íslenska bókmenntafélag, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, K. Ethnographic Methods; Routledge, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Einarsdóttir, J.; Gunnlaugsson, G. Inngangur. Árstíðabundinn Flutningur Barna. In Send í sveit: Þetta var í þjóðarsálinni; Einarsdóttir, J., Gunnlaugsson, G., Eds.; Hið íslenska bókmenntafélag: Reykjavik, 2019; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Friese, S.; Soratto, J.; Pires, D. Carrying out a Computer-Aided Thematic Content Analysis with ATLAS. Ti; Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity: Göttingen, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Unicef SDG Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/sdgs/goal-8-decent-work-economic-growth/ (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Alþingi 258. Frumvarp Til Umferðarlaga. (Lagt Fyrir Alþingi á 76. Löggjafarþingi, 1957.) 117. Mál. Available online: https://www.althingi.is/altext/76/s/pdf/0258.pdf.

- Alþingi Leit í ræðutexta. Available online: https://www.althingi.is/thingstorf/raedur/ordaleit/ (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Alþingi 407. Frumvarp Til Umferðarlaga. Available online: http://www.althingi.is/altext/77/s/pdf/0407.pdf.

- 23 banaslys á dráttavélum síðan 1958. Alþýðublaðið 1966, 47, 2.

- Alþingi Umferðarlög 50/1987. Available online: https://www.althingi.is/lagas/nuna/1987050.html (accessed on 11 November 2018).

- Guðný Björk Eydal; Guðbjörg Linda Rafnsdóttir; Margrét Einarsdóttir Working Children in Iceland: Policy and the Labour Market. Barn 2009, 3, 187–203. [CrossRef]

- Committee on Injury and Poison Prevention and Committee on Community Health Services Prevention of Agricultural Injuries Among Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics 2001, 108, 1016–1019. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OSHA Agricultural Operations - Overview. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/agricultural-operations (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Tómasson, K.; Gústafsson, L.; Christensen, A.; Røv, A.S.; Gravseth, H.M.; Bloom, K.; Gröndahl, L.; Aaltonen, M. Nordic Council of Ministers. Fatal Occupational Accidents in the Nordic Countries 2003–2008, Tema Nord 2011: 501. Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011; TemaNord; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, S.; Marlenga, B.; Lee, B.C. Childhood Agricultural Injuries: An Update for Clinicians. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2013, 43, 20–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, W.; King, N.; Marlenga, B.; Lawson, J.; Hagel, L.; Elliot, V.; Dosman, J.A. Saskatchewan Farm Injury Cohort Study Team Exposure to Agricultural Hazards among Children Who Visit Farms. Paediatr. Child Health 2018, 23, e143–e149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcury, T.A.; Arnold, T.J.; Mora, D.C.; Sandberg, J.C.; Daniel, S.S.; Wiggins, M.F.; Quandt, S.A. “Be Careful!” Perceptions of Work-safety Culture among Hired Latinx Child Farmworkers in North Carolina. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2019, 62, 1091–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagel, L.; King, N.; Dosman, J.A.; Lawson, J.; Trask, C.; Pickett, W. Profiling the Safety Environment on Saskatchewan Farms. Saf. Sci. 2016, 82, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnetson, B. Narratives Justifying Unregulated Child Labour in Agriculture. J. Rural Community Dev. 2009, 4, 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- Benediktsson, K. Beyond Productivism: Regulatory Changes and Their Outcomes in Icelandic Farming. Dev. Sustain. Rural Syst. 2001, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hartling, L.; Brison, R.J.; Crumley, E.T.; Klassen, T.P.; Pickett, W. A Systematic Review of Interventions to Prevent Childhood Farm Injuries. Pediatrics 2004, 114, e483–e496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fargnoli, M.; Lombardi, M.; Haber, N.; Puri, D. The Impact of Human Error in the Use of Agricultural Tractors: A Case Study Research in Vineyard Cultivation in Italy. Agriculture 2018, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.C. Child Farm Injuries Are Never “Accidents”. J. Agromedicine 2024, 29, 304–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).